CIVILIAN WORKFORCE

DOD Is Implementing Actions to Address Challenges with Accessing Health Care in Japan and Guam

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Rashmi Agarwal at agarwalr@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑107453, a report to congressional committees

DOD Is Implementing Actions to Address Challenges with Accessing Health Care in Japan and Guam

Why GAO Did This Study

DOD relies on thousands of federal civilian employees and contractors in Japan and Guam to accomplish its missions in the increasingly important Indo-Pacific region. However, these individuals face unique challenges accessing health care. In 2022, the Defense Health Agency issued guidance restating that these individuals may receive care at military medical facilities only if capacity allows, because active-duty service members and their families are prioritized.

The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024 includes a provision that GAO review health care available to U.S. civilians and contractors who support U.S. Forces Japan and Joint Region Marianas (Guam) overseas, their dependents, and certain dependents of active-duty service members. This report examines how often these DOD-affiliated civilians and families access health care at military medical facilities in Japan and Guam, the challenges these individuals face accessing health care through local providers in Japan and Guam, and the extent DOD is addressing any challenges.

GAO reviewed federal law, DOD documentation, and data on space-available visits from fiscal years 2019 to 2024; interviewed officials; and held five non-generalizable, in-person discussion groups with civilians randomly selected from lists of DOD civilians working in Japan and Guam.

What GAO Found

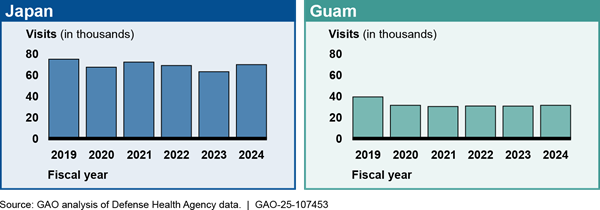

Department of Defense (DOD)-affiliated civilians and families in Japan and Guam may receive health care at military medical facilities only if capacity allows (referred to as care on a space-available basis). As a result, these individuals generally rely on local providers for their health care. From fiscal years 2019 to 2024, the number of space-available visits for DOD-affiliated civilians and families at military medical facilities in Japan remained stable overall but varied by year. Over the same time frame, space-available visits at military medical facilities in Guam were stable after a 20 percent decline between 2019 and 2020. DOD officials attributed the decline to a shortage in enlisted support staff in primary care clinics and challenges related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

In Japan, DOD-affiliated civilians and families face cultural challenges in accessing care with local providers. Commonly cited challenges include language barriers, complex billing, a different approach to care, and a different emergency care system. DOD has taken steps to address some of these challenges. For example, to make civilians more aware of potential challenges they may face, DOD developed a statement of understanding in April 2024 for prospective employees to sign prior to taking a position in Japan. This statement describes their responsibility for obtaining and paying for health care overseas and how health care services in Japan may not be equivalent to those in the United States. The statement is intended to encourage individuals to assess their personal health needs before accepting a job in Japan, according to DOD officials. The department also began a pilot program in January 2025, which is intended to help DOD civilians find Japanese providers and make required, up-front payments for care.

In Guam, DOD-affiliated civilians and families face capacity challenges in accessing care with local providers. Commonly cited challenges include failing infrastructure, limited health care professionals, and geographic remoteness. DOD has worked with Guamanian partners to attempt to lease land to build a new public hospital, has provided funding to upgrade existing public medical facilities, and plans to expand military medical facility capacity as the active-duty population grows on the island. DOD also has a working group to address issues that may continue to arise, given its planned growth of the civilian population on Guam.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

AAFES |

Army and Air Force Exchange Service |

|

DHA |

Defense Health Agency |

|

DOD |

Department of Defense |

|

Health Affairs |

Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs |

|

HVAC |

Heating, ventilation, and air conditioning |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

April 3, 2025

The Honorable Roger Wicker

Chairman

The Honorable Jack Reed

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

United States Senate

The Honorable Mike Rogers

Chairman

The Honorable Adam Smith

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

House of Representatives

The Department of Defense (DOD) relies on thousands of federal civilian employees and contractors in Japan and Guam to advance its mission and address the growing threat posed by China in the Indo-Pacific region. These individuals fill a wide variety of critical positions including engineering, construction, food service, health care, intelligence, and teaching. Additionally, DOD is planning to increase the number of civilians in the region, particularly in Guam, to support the increase in military personnel and expanded mission in the Indo-Pacific.

Some U.S. civilians in Japan expressed concern about their ability to access health care in 2022, and some individuals formed an advocacy group called the Japan Civilian Medical Advocacy group. These concerns arose after the Defense Health Agency (DHA) issued guidance in 2022 that restated DOD policy from 2011 and 2018 regarding eligibility and prioritization of care at military medical facilities in the Indo-Pacific region.[1] These policies state that military medical facilities are to prioritize care for active duty service members and eligible family members. The motivation for issuing the 2022 guidance was limited capacity at some military medical facilities in the region and challenges meeting care standards for active duty service members and eligible family members, according to documentation from the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs.

The 2022 guidance also restated that federal civilian employees, contractors, and their dependents are not guaranteed care at military medical facilities and encouraged them to seek care in the local community of the host nation.[2] Though not a change in policy, as written, the guidance changed how some of these individuals sought out and received health care, as many individuals were accustomed to receiving their care at military medical facilities.

Specifically, the 2022 guidance stated that DOD civilian employees, contractors, and their family members may receive care if space is available at the military medical facility only for non-recurring, acute conditions. In March 2023, DHA issued a memorandum superseding the 2022 guidance.[3] The memo allowed DOD civilian employees, contractors, and their family members in the Indo-Pacific region to receive treatment for recurring, non-acute conditions on a space-available basis. The memo also established standard processes for space-available care in military medical facilities.

Section 726 of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024 includes a provision for GAO to review health care available to U.S. civilians and contractors who support U.S. Forces Japan and Joint Region Marianas (Guam) overseas, their dependents, and certain dependents of active duty service members—here after referred to as DOD-affiliated civilians and families.[4] This report examines 1) how often DOD-affiliated civilians and families accessed health care at military medical facilities in Japan and Guam, 2) the challenges these individuals faced accessing health care through local providers in Japan, and the extent DOD is addressing any challenges; and 3) the challenges these individuals faced accessing health care through local providers in Guam, and the extent DOD is addressing any challenges.

For the first objective, we reviewed DOD documentation to determine how often DOD-affiliated civilians and families accessed health care in Japan and Guam. We also analyzed data from DHA on space-available visits—that is, the number of visits DOD-affiliated civilians and families made to military medical facilities when capacity allowed at the facility. We analyzed data from fiscal years 2019 through 2024 to include a year before the COVID-19 pandemic.[5] We reviewed relevant documentation and interviewed agency officials knowledgeable about the data and found the data to be sufficiently reliable for the purpose of reporting the number of space-available visits.

For the second and third objectives, we reviewed DOD documentation and policies, interviewed DOD officials, and held five nongeneralizable, in-person discussion groups with randomly selected DOD civilians who work at U.S. military bases in Japan and Guam about their access to health care.[6] For all three objectives, we interviewed agency officials, including those from DOD, the Office of Personnel Management, and the Department of State to determine how DOD-affiliated civilians and families access health care in Japan and Guam and whether there are initiatives to improve access. For a detailed description of our scope and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from March 2024 to April 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

DOD Service Members, Civilians, and Contractors in Japan and Guam

Japan hosts U.S. bases, facilities, and over 50,000 military service members as of fiscal year 2024. Guam is the westernmost U.S. territory in the Indo-Pacific region and hosts over 7,000 service members as of fiscal year 2024. In addition to service members, U.S. civilian employees and contractors in Japan and Guam play critical roles in supporting military operations and ensuring the success of DOD missions in the Indo-Pacific region. Table 1 shows the number of military service members, civilian employees, contractors, and dependents in Japan and Guam as of fiscal year 2024.

Table 1: Department of Defense Service Members, Civilians, Contractors, and Dependents in Japan and Guam, Fiscal Year 2024

|

Japan |

Guam |

|

|

Military (active duty and reserve) |

53,245 |

7,361 |

|

Civilian employees |

9,799 |

5,055 |

|

Contractors |

4,824 |

480 |

|

Dependentsa |

35,332 |

9,212 |

Source: Defense Manpower Data Center (military) and U.S. Forces Japan and Joint Region Marianas (civilians, contractors, and dependents). | GAO‑25‑107453

aFor Japan, this number includes military and civilian dependents. For Guam, this number includes military dependents only.

DOD civilians and contractors contribute to maintaining military readiness, enable daily operations, and support the broader strategic objectives of the United States. They perform a wide range of functions across various sectors, including education, logistics, infrastructure, health care, and intelligence (see fig. 1).

Figure 1: Selected Occupations of Civilians and Contractors Supporting DOD Missions in Japan and Guam

Key Stakeholders Supporting DOD-Affiliated Civilians and Families’ Access to Health Care

DOD’s military health system is a complex enterprise overseen by the Secretary of Defense. Within this enterprise, the Defense Health Agency is responsible for health care delivery to the uniformed services, and it shares the responsibility for medical readiness with the three military departments—the Army, Navy, and Air Force.

The Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness is the principal staff assistant and advisor to the Secretary of Defense for health-related matters and, in that capacity, is responsible for developing policies, plans, and programs for health and medical affairs.[7]

The Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs (Health Affairs) serves as the principal advisor to the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness for all DOD health-related policies, programs, and activities.[8] The Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs has the authority to develop policies; conduct analyses; issue guidance; provide advice and make recommendations to the Secretary of Defense, the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness, and others; and provide oversight on matters pertaining to the military health system.

The Director of the Defense Health Agency (DHA) functions under the authority, direction, and control of the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness through the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs. As such, the Director manages, among other things, the military medical facilities, the execution of policies issued by the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs, and the TRICARE program.[9]

TRICARE is DOD’s health care program that provides comprehensive health care coverage to active duty service members, retirees, and eligible family members. TRICARE provides various options that provide differing levels of coverage at military medical facilities and civilian providers overseas:

· TRICARE Prime Overseas is a managed care option in overseas areas near military medical facilities and is distinguished from TRICARE Prime, which is an option only in certain areas of the United States. With this plan, active duty service members, activated National Guard and Reserve members, and their eligible family members work with a primary care manager at a military medical facility who provides most of their care, and refers them to specialists when needed. Individuals with TRICARE Prime Overseas are prioritized care at military medical facilities. Military retirees and their families cannot enroll in TRICARE Prime Overseas, and therefore are not guaranteed care at a military medical facility in Japan or Guam.

· TRICARE Select Overseas is a self-managed care option in overseas areas. Those eligible for Select Overseas, which include certain active duty family members, military retirees, and retirees’ family members, may obtain covered services from any TRICARE-authorized provider, meaning beneficiaries can receive care at military medical facilities when there is extra capacity or manage their own appointments within the civilian network. These individuals are not guaranteed care at a military medical facility in Japan or Guam.

· TRICARE Plus, while not a TRICARE health plan, is a program offered at some military medical facilities in which the individual is empaneled, or set up with, a primary care provider at the facility. Each facility, in coordination with the military installation, makes the decision whether to empanel certain groups based on current and projected capacity after ensuring the health care needs of active duty service members and their eligible family members are met, according to DOD officials. Most individuals in this program in Japan and Guam are military retirees and their family members. Individuals who are eligible for TRICARE but not enrolled in TRICARE Prime can join TRICARE Plus if offered at a facility. These individuals are empaneled to a primary care provider at the facility on the basis that there is extra capacity at the facility. TRICARE Plus does not guarantee access to specialty care at the facility.

The Secretaries of the military departments coordinate with the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs to develop certain military health system policies, standards, and procedures and provide military personnel and other authorized resources to support the activities of DHA, among other things. They are also responsible for ensuring the readiness of military personnel.

The U.S. Office of Personnel Management serves as the chief human resources agency and personnel policy manager for the Federal Government. It is responsible for administering the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program by publishing regulations and guidance and contracting with qualified health insurance carriers, negotiating plan benefits and premiums, among other responsibilities.[10] DOD civilians are eligible for the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program, for which DOD pays most of the health plan premium.[11]

Employees who are contractors generally have agreements about health care with their employer, which may include other private insurance offered by their employer.

Military Medical Facilities in Japan and Guam

As of December 2024, there were 17 military medical facilities in Japan and three in Guam (see fig. 2). These facilities vary in size and capabilities from small clinics to outpatient surgery centers, hospitals, and medical centers. Military medical facilities’ workforces include health care providers, such as physicians (both primary and specialty care providers), nurses, and enlisted specialists who assist with medical procedures, as well as administrative and support personnel.

According to DOD Instruction 6000.19, the primary purpose of military medical

facilities is to support the readiness of the military services.[12] In particular, the guidance states

that the size, type, and location of each facility must further this readiness

objective. Further, each facility must spend most of its resources supporting

wartime skills, development and maintenance for military medical personnel, or

the medical evaluation and treatment of service members.

To meet these readiness goals, military medical facilities primarily provide care through TRICARE to active duty service members, military retirees, and their eligible family members—collectively known as TRICARE beneficiaries.

In addition to serving TRICARE beneficiaries, military medical facilities may also treat nonbeneficiary civilians, contractors, and dependents on a space-available basis, following the DHA’s guidance and standard processes.[13] However, this care is offered only when resources permit after the health care needs of active duty service members and their eligible family members are met, and may vary based on the facility’s staffing, capacity, and mission requirements.[14]

Preemployment Medical Screening of DOD Civilians

DOD civilian employees are generally not required to have a physical or medical assessment by a doctor prior to beginning an assignment, according to DOD officials. Officials stated that exceptions in which DOD civilian employees can be screened prior to beginning assignment include 1) civilians deploying in support of contingency operations, 2) DOD civilians who will be working in certain remote locations with hardship factors, 3) DOD civilians assigned to a State Department post, and 4) civilians hired for a position with a specific physical requirement.

According to DOD officials, civilian employees are not generally screened because federal law and regulation state that DOD must select civilian employees for specific positions based on job requirement and merit factors.[15] Selection for an overseas position, such as in Japan or Guam, must not be influenced by the special needs of a civilian employee’s family member(s), or any other prohibited factor.

In 2018, DOD reported to Congress on this topic. Senate Report 115-125, accompanying a bill for the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2018 requested DOD to review overseas assignment policies pertaining to civilian and contractor personnel in support of DOD operations.[16] In DOD’s March 2018 report in response to this request, the department stated it did not believe any policy changes were necessary and that it would not be beneficial to be overly restrictive in screening of civilian employees due to existing laws.[17]

DOD is required to provide prospective civilian employees with medical information about the overseas community where the position is located.[18] This is intended to help the employee make an informed choice about accepting the position. Individuals can self-disclose medical concerns or special needs that they or a family member have during the tentative job offer phase. The DOD civilian human resources representatives can provide further information on the medical situation in the overseas location but, according to federal regulation, may not coerce or pressure the selectee to accept or decline the job offer in light of medical information. Later in this report, we provide more information about DOD’s Statement of Understanding regarding health care that it provides prospective employees assigned to positions in Japan.

DOD-Affiliated Civilians and Families’ Medical Visits to Military Medical Facilities in Japan and Guam Remained Stable Overall in Recent Years

From fiscal year 2019 to 2024, the number of space-available visits for DOD-affiliated civilians and families at military medical facilities in Japan varied year to year, but remained stable overall.[19] Over the same time frame, the number of space-available visits at military medical facilities in Guam were stable after a 20 percent decline between 2019 and 2020.[20] Some DOD civilians we spoke to preferred receiving care at military medical facilities, while others preferred receiving care from local providers.

Health care through military medical facilities. DOD-affiliated civilians and families in Japan and Guam, without TRICARE Prime Overseas, may receive health care at a military medical facility if capacity allows—referred to as space-available care (see sidebar on recent changes to care for DOD-affiliated civilians and families).[21] The availability of these appointments and services at medical facilities is often unpredictable and cannot be scheduled far in advance. For example, medical facility officials at 374th Medical Group at Yokota Air Base, BG Crawford F. Sams U.S. Army Health Clinic at Camp Zama, Naval Hospital Okinawa, Naval Hospital Yokosuka, and Naval Hospital Guam stated that individuals must call after 10 or 11 a.m. to attempt to schedule a space-available appointment that day. Exceptions include emergency care and certain pharmacy services.[22] Specifically, DOD-affiliated civilians and families may receive emergency services at a military medical facility emergency department.

|

Changes to Military Medical Care for DOD-Affiliated Civilians and Families The Defense Health Agency (DHA) issued guidance in December 2022 that said military medical facilities in the Indo-Pacific region would treat federal civilians, U.S. contractors, and their family members on a space-available basis—defining space-available care as episodic (non-recurring) health care for acute conditions. Patients not enrolled in TRICARE Prime who had been receiving care for other minor episodic issues and chronic care (such as diabetes and hypertension) were advised to seek care with local providers. In March 2023, DHA issued a memorandum superseding the December 2022 guidance. The memo established standard processes for space-available care in military medical facilities in the region and allowed for treatment of recurring, non-acute conditions if space is available. Though not a formal policy change, these issuances

represented a change for some individuals. For example, according to military

medical facility officials, civilians at Naval Hospital Okinawa and the

health clinic at Camp Zama were informally enrolled at the facilities with a

primary care provider prior to the issuances. Source: GAO analysis of Department of Defense (DOD) documents. | GAO‑25‑107453 |

From fiscal year 2019 to 2024, trends in the number of space-available visits at military medical facilities in Japan and Guam varied by health care plan and by facility. DHA officials stated that several factors affected the numbers and trends of these visits over this period, including:

· the size of the total DOD-affiliated population, including service members,

· the capacity at the military medical facility due to on-hand medical provider and support staff resources, and

· COVID-19. According to DHA officials, Japan experienced a longer duration of COVID-19 required operations compared to the U.S, which strained resources.

In addition, according to DHA officials, Japan and Guam military medical facilities transitioned to a new electronic health record system in October 2023 and January 2024, respectively. This transition temporarily reduced appointment availability due to preparation and training requirements.

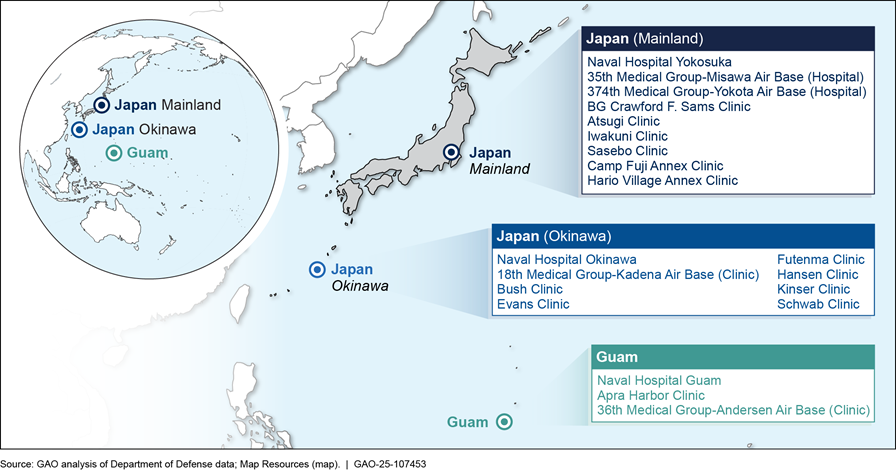

From fiscal year 2019 to 2024, the number of space-available visits at military medical facilities in Japan varied year to year, but were stable overall (see fig. 3).[23] Over this time frame, these visits remained between 12 and 14 percent of total visits in military medical facilities.[24] In fiscal year 2024, 44 percent of space-available visits were with individuals without military health system insurance (TRICARE) and not participating in TRICARE Plus. These individuals may have some other form of insurance, such as a Federal Employees Health Benefits plan, private insurance, or no insurance.

Figure 3: Space-Available Visits at Military Medical Facilities in Japan, by Health Care Plan, Fiscal Years 2019–2024

Notes: A space-available visit is an interaction between a medical provider at a military medical facility and a patient who is not guaranteed care at the facility but can get care if there is extra capacity. TRICARE Select is a self-managed care plan in which individuals are not guaranteed care at a military medical facility in Japan or Guam. TRICARE Plus is a program offered at some military medical facilities in which individuals have a primary care provider at the facility on the basis that there is extra capacity. Non-TRICARE Health Plan refers to individuals who do not have TRICARE but may have some other form of insurance, such as a Federal Employees Health Benefits plan, private insurance, or no insurance.

Number of visits excludes mass vaccinations (including COVID-19 and flu); nurse (except nurse anesthetist, nurse practitioner and midwife), technician, and support staff visits; Military Entrance Processing Station visits; and other readiness or administrative-related visits.

From fiscal year 2019 to 2024, trends in space-available visits varied by health care plan. For example, over this 6-year time frame, space-available visits in which the patient had a TRICARE health plan declined 28 percent, visits in which the patient was participating in TRICARE Plus increased 16 percent, and visits in which the patient did not have a TRICARE health plan and was not participating in TRICARE Plus declined 13 percent.

From fiscal year 2019 to 2024, trends in space-available visits also varied by facility. For example, over this 6-year time frame, there was relatively little change in space-available visits at Naval Hospital Okinawa, the largest overseas hospital in the Navy, and Family Branch Clinic Iwakuni. From fiscal year 2019 to 2024, visits declined between 11 and 13 percent at Naval Hospital Yokosuka, 35th Medical Group in Misawa, and 374th Medical Group in Yokota. Over this same period, space-available visits increased 26 percent at Branch Health Clinic Sasebo and decreased 41 percent at BG Crawford F. Sams U.S. Army Health Clinic at Camp Zama—two relatively small clinics.

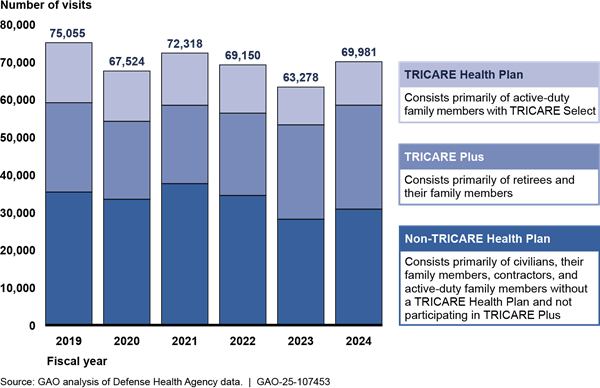

From fiscal year 2019 to 2020, space-available visits at military medical facilities in Guam declined 20 percent, after which they remained stable through fiscal year 2024 (see fig. 4). Over this time frame, these visits declined from 34 percent of total visits in military medical facilities in 2019 to 27 percent in 2024. In fiscal year 2024, 21 percent of space-available visits were from individuals without military health system insurance (TRICARE) and not participating in TRICARE Plus.

Figure 4: Space-Available Visits at Military Medical Facilities in Guam, by Health Care Plan, Fiscal Years 2019–2024

Notes: A space-available visit is an interaction between a medical provider at a military medical facility and a patient who is not guaranteed care at the facility but can get care if there is extra capacity. TRICARE Select is a self-managed care plan in which individuals are not guaranteed care at a military medical facility in Japan or Guam. TRICARE Plus is a program offered at some military medical facilities in which individuals have a primary care provider at the facility on the basis that there is extra capacity. Non-TRICARE Health Plan refers to individuals who do not have TRICARE but may have some other form of insurance, such as a Federal Employees Health Benefits plan, private insurance, or no insurance. Naval Hospital Guam has an agreement with Veterans Affairs to treat veterans at the hospital. Veterans Affairs administers its own health care system. Some veterans may also be DOD civilian employees, contractors, or family of civilians, contractors, or service members.

Number of visits excludes mass vaccinations (including COVID-19 and flu); nurse (except nurse anesthetist, nurse practitioner and midwife), technician, and support staff visits; Military Entrance Processing Station visits; and other readiness or administrative-related visits.

From fiscal year 2019 to 2024, trends in space-available visits varied by health care plan. For example, over this 6-year time frame, space-available visits in which the patient had a TRICARE health plan declined 19 percent, visits in which the patient was participating in TRICARE Plus declined 28 percent, visits in which the patient did not have a TRICARE health plan and was not participating in TRICARE Plus increased 68 percent, and visits in which the patient was treated under the Veterans Affairs agreement declined 44 percent.

From fiscal year 2019 to 2024, trends in space-available visits also varied at the three military medical facilities in Guam. For example, over this 6-year time frame, space-available visits increased 40 percent at 36th Medical Group at Andersen Air Base. At Naval Hospital Guam, the largest military medical facility in Guam, space-available visits declined 21 percent from fiscal year 2019 to 2020, then remained stable. DOD officials attributed the decline between 2019 and 2020 to a shortage in enlisted support staff in primary care clinics, which leads to less capacity for all patient categories except active duty service members, as well as challenges related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Many DOD civilians we spoke to prefer to receive care at military medical facilities because of the convenience and their familiarity with the military health care system. Participants in our discussion groups in Japan noted that military medical facilities are often their first choice for care due to the lack of a language barrier and consistent use of U.S. medical standards and practices. Other civilians we spoke to in Japan and Guam mentioned that military medical facilities were their preferred choice for certain specialty care services, such as physical therapy or pediatrics, where they felt more confident in the quality of care compared to off-base options.

Health care through local providers. DOD-affiliated civilians and families are responsible for seeking and paying for health care through the local providers in Japan and Guam the same as DOD civilians living in the continental United States or any other location. Specifically, individuals seek care within their health insurance’s network or pay out-of-pocket if their insurance does not cover a service or they do not have insurance with the necessary coverage. Given Guam is a U.S. territory, health care networks and insurance operate largely the same as in the continental United States. However, there are some differences in how federal insurance operates in Japan. Notably, federal civilians must pay upfront for services and then bill their insurance for reimbursement, unless their insurance has a direct-billing agreement with the Japanese provider. The Federal Employees Health Benefits plans with the highest enrollment of federal employees in Japan, according to DOD officials, offer benefits to DOD civilians and family members such as overseas assistance call centers that discuss covered benefits and assist with claims, bill translation services, and some telehealth services.

According to DOD civilians we talked to through our five discussion groups, many receive health care from local providers in Japan and Guam. Some in Japan have established relationships with Japanese providers and prefer to seek care off base rather than using military medical facilities. DOD civilians we talked to in Japan said they commonly make use of insurance benefits like billing translation services to help navigate billing and the local health care system. Some DOD civilians we spoke with in Guam who were from the island described how they were accustomed to the island’s health care system and had connections with local doctors.

DOD Has Taken Steps to Address Some Cultural Challenges That Limit DOD-Affiliated Civilians and Families’ Access to Health Care in Japan and Has Plans to Address Others

DOD-Affiliated Civilians and Families Face Cultural Challenges in Accessing Health Care in Japan

Through interviews with DOD officials, four discussion groups with civilians, and interviews with representatives from an advocacy group (the Japan Civilian Medical Advocacy group), we identified four commonly cited challenges associated with accessing medical care through local providers in Japan (see fig. 5).

Many of these challenges are similar to those faced by active duty service members serving in Japan and their families when seeking off-base care, and some also apply to Japanese citizens. Officials varied in their opinions on whether these challenges have affected DOD’s mission in Japan and stated that data linking readiness to this specific health care issue was difficult to obtain (see side bar). Changes in high-level recruitment or retention numbers, for example, can have many causes.

|

Effects of Health Care Challenges on DOD’s Mission in Japan According to data from the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs, attrition rates for DOD civilians in Japan varied between fiscal years 2021 and 2024. Specifically, in fiscal years 2021 and 2023, overall attrition rates for DOD civilians in Japan were slightly higher compared to non-foreign locations outside the continental United States. By comparison, in fiscal years 2022 and 2024, overall attrition rates were lower or about the same. DOD officials from entities with the most civilian employees in Japan had varying assessments of the extent health care access for civilians was affecting their missions and the mission of U.S. Forces Japan. For example, U.S. Forces Japan officials stated that health care access challenges limit their ability to attract and retain the best talent. According to these officials, though a position may ultimately be filled, it may not be the best candidate and it may take additional time and costs to hire them. Similarly, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers officials stated that they often experience candidates that do not accept a job during the tentative job offer phase after the candidate begins looking into health care. It takes time and money to restart the process and find a new candidate. Officials from other DOD civilian employers, including U.S. Army Japan and Naval Facilities Engineering Systems Command Far East, stated that health care access is not a major challenge for their workforce. According to these officials, while disclaimers on job postings and requirements to discuss challenges with selectees turns away applicants, employees do not have major issues once they are in the country. Source: GAO analysis of DOD documentation and interviews with officials. | GAO‑25‑107453 |

Language barriers. DOD-affiliated civilians and families who seek care off base often find it difficult to find Japanese providers with sufficient English skills. Although some hospitals and clinics in Japan offer translation services, DOD civilians in three of our four discussion groups in Japan told us these services are not always available or reliable. Additionally, they reported that even when health care providers speak English, other staff—such as receptionists or support staff—often do not, creating additional challenges in scheduling and navigating appointments. Civilians told us that sometimes paperwork or prescriptions were provided solely in Japanese and required additional time and effort to translate essential health information accurately.

DOD civilians in two of our four discussion groups in Japan told us that miscommunication during medical appointments led to confusion over diagnoses and treatment plans. Further, civilians stated that language barriers often discourage them from pursuing health care off base altogether.

Complex billing. DOD-affiliated civilians and families have encountered billing challenges at Japanese providers that often operate differently from the U.S. health care system. These challenges include the following:

· Upfront payment requirements. Those without Japanese national health insurance are generally required to pay for services at the time of their appointment or treatment. According to civilians in all four of our discussion groups in Japan, this has led to confusion and financial strain, as DOD civilians may have to pay in full upfront and then wait months for reimbursement from their health insurance. For example, one discussion group participant shared that after their spouse underwent emergency surgery at a local Japanese hospital, the hospital required full payment before they would discharge the patient. The civilian had to leave their spouse at the hospital to withdraw the necessary funds and return to settle the bill.

· Cashless billing limitations. Many civilian employees expected to benefit from cashless billing agreements where insurers pay providers directly. However, civilians in all four of our discussion groups encountered difficulties finding providers who participate in such arrangements. For example, one participant shared that the absence of cashless billing options forced them to open multiple credit cards to cover the upfront cost of medical care. These limitations complicate access to care and leave many employees responsible for navigating complex payment processes independently with minimal assistance from their health insurance. Moreover, according to U.S. Forces Japan officials, this issue could deter individuals with security clearances from accepting a position in Japan. Specifically, officials stated that employees, including those in the intelligence community, may be concerned about losing their security clearances because they had to open multiple credit cards or incur large amounts of debt to pay for medical services.

· Reimbursement and claims processing. Civilians in three of our four discussion groups in Japan have also faced issues with insurance reimbursements and navigating claims processes. Several reported misunderstandings about coverage, receiving bills for services they thought were covered, and delays in reimbursement. For example, one civilian discussion group participant shared their experience of undergoing emergency surgery after being unable to find care on base. While the off-base care was effective, the upfront cost was very expensive. Their insurance denied reimbursement, citing that the procedure did not meet U.S. standards of care, despite the procedure being determined as necessary. At the time of our discussion group, they were still working out the reimbursement, and the issue remained unresolved.

Despite these issues, civilians and DOD officials in Japan noted that the cost of medical care in Japan is often less expensive than similar care in the United States, which can mitigate some of the financial strain.

Different approach to care. DOD officials and civilians in all four discussion groups in Japan told us that the difference in how Japanese providers’ approach health care versus approaches in the United States has created challenges. For example, according to DOD officials, Japan’s culture of care often emphasizes less intervention and more conservative treatments. Officials explained that this differs from the U.S. system that can be a more aggressive, immediate approach to care that some civilians are accustomed to receiving.

In addition, according to a study published in the Japan Epidemiological Associations’ Journal of Epidemiology, some chronic conditions such as diabetes and obesity are less common in Japan, and Japanese providers may not have as much experience working with these conditions.[25] Civilians in two discussion groups described difficulties associated with obesity and diabetes when accessing care in Japan. One participant shared that they were unable to undergo a necessary surgery at a Japanese medical facility because of their weight. As a result, they had to return to the United States to have the procedure. Another participant explained that medical facilities in Japan often lack equipment designed to accommodate larger individuals, such as wheelchairs and blood pressure cuffs.

Furthermore, according to the World Health Organization and the Japan Medical Association, drugs used for pain management such as epidurals during pregnancies or forms of pain management opioids are not as commonly used in Japan.[26] Due to this, civilians in three of our four discussion groups in Japan told us they will return to the United States before receiving necessary surgeries or before giving birth.

Additionally, mental health care in Japan is not equivalent to that in the United States. According to the World Health Organization, Japan has fewer mental health workers per 100,000 population than the United States. For DOD-affiliated civilians and families, these challenges are compounded by difficulties finding providers who understand American cultural contexts or can effectively communicate in English. For example, civilians in two of our four discussion groups expressed concerns about the effectiveness of receiving behavioral health care from non-native English speakers. They told us that subtle language nuances are often essential for effective communication in mental health settings.

The cultural mismatch has left some civilians in our discussion groups dissatisfied with the care they receive. However, some DOD officials and civilians told us that care received in Japan is excellent and sometimes surpasses what would be received in the United States (see sidebar for health outcomes in Japan).

|

Health Care Outcomes in Japan Japan ranks among the top countries for quality and outcome of health care in international rankings. Key health outcomes according to assessments from international and health organizations include: · Life expectancy: The average life expectancy in 2021 in Japan—84.5 years—is one of the highest in the world, compared to the U.S. average of 76.4 years. · Infant and maternal mortality: Japan has one of the lowest infant and maternal mortality rates globally. The maternal mortality rate per 100,000 live births is 2.7 in Japan, compared to 23.8 in the U.S. These outcomes should also be understood in the context of diet, exercise, lifestyle, and other societal differences between Japan and the United States, not only differences between the health care systems. For example, Japan has lower rates of obesity and cardiovascular disease, which leads to higher life expectancy; fewer comorbid conditions, which leads to fewer complications in pregnancy and in managing other conditions; and lower violent crime rates.

|

Different emergency care system. Civilians in our discussion groups noted concern with Japan’s emergency care system, which differs significantly from the United States and other countries with U.S. military presence. Following multiple acute incidents and deaths of DOD-affiliated personnel in Japan, a May 2023 U.S. Forces Japan investigation found that patients do not have timely access to emergency care at Japanese facilities in accordance with U.S. medical standards of care. An April 2024 DHA assessment stated that while Japanese emergency care was generally sufficient, cultural differences, language barriers, and unique processes have delayed care and, in some cases, led to adverse outcomes.

For example emergency room access in Japan is managed by the paramedic who performs triage and determines need. The paramedic then contacts the nearest hospital with the appropriate clinical capability and bed capacity. If the hospital cannot admit the patient, the paramedic contacts additional hospitals until one agrees to accept the patient. This differs from the United States, where hospitals are legally required to accept and evaluate any emergency patient. This can lead to delays, as ambulance drivers must call around to find an available hospital if patients, including American personnel, are turned away. Further, a 2018 study compared U.S. and Japan trauma care outcomes and found that in most cases outcomes were comparable, but Japan had poorer outcomes for patients undergoing blood transfusions (i.e. those with active hemorrhage). The study attributed these results to differences in diagnostic methods, fewer in-house attending trauma surgeons, and less experience with penetrating injuries.[27]

In addition, both the U.S. Forces Japan investigation and DHA assessment stated that COVID-19 exacerbated challenges accessing Japanese facilities. Notably, these challenges accessing emergency care exist also for service members and for Japanese citizens. According to a U.S. Marine Corps investigation, other countries with U.S. military presence, like South Korea, Spain, and Germany, do not face this issue.[28]

According to an official from the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs, while the system may be frustrating, it sometimes results in more specialized care by ensuring patients are transported to a facility with the necessary clinical capability. However, unfamiliarity with this system and language barriers make navigating the system difficult. As noted previously, any U.S. civilian with base access can also go to a military medical facility for emergency care if one is nearby.

DOD Has Taken Steps to Address Some Cultural Challenges in Accessing Health Care in Japan

Through interviews with DOD officials and review of DOD documentation, we identified DOD steps to address some challenges that DOD-affiliated civilians and families face accessing medical care in Japan. Many of these steps we identified are recent or planned, and it is too soon to determine their full effects.

Oversight and coordination. The Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs (Health Affairs) has held monthly meetings since August 2023 and established a Japan Access to Care working group to discuss challenges and solutions for DOD-affiliated civilians and their families to access health care in Japan. These meetings address topics such as access to care standards and trends; context and specific challenges in Japan; and solution areas, such as emergency medical improvements and a health insurance enhancement pilot program, outlined later in this report. They include relevant stakeholders from DOD components such as the military departments, DHA, and civilian employers.

Pre-hire statement of understanding. In April 2024, the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness directed civilian personnel appointing authorities to provide a statement of understanding to employees and candidates selected for positions in Japan.[29] The statement asks the employee to acknowledge 1) their responsibility for obtaining and paying for health care services overseas for themselves and their family members; 2) that health care services in Japan may not be equivalent to those in the U.S. and may require up-front payment; and 3) their eligibility and financial responsibility for space-available care at military medical facilities, among other things. The statement is intended to manage expectations and encourages individuals to assess their personal health needs before committing to a role in Japan, according to DOD officials.

According to a U.S. Forces Japan official, the statement of understanding has been implemented by all components. The statement is based on a similar statement that the DOD Education Activity Pacific has been using since 2021, according to a DOD Education Activity official.

DOD officials from the Defense Civilian Personnel Advisory Service stated they are coordinating internally a policy on overseas health care that would require components overseas (not only in Japan and Guam) to ensure that employees complete a statement of understanding, such as the one described above, as well as an overseas health care checklist. The current version of the checklist, which some components in Japan and Guam use, asks civilians to check on their insurance coverage in the event of emergency medical care while overseas, meet with their doctors to obtain medical information about the overseas location, and consult with management at the overseas location about services available for special needs, among other things.

Health insurance enhancement pilot program. Health Affairs, through DHA, began a pilot program January 1, 2025, aimed at providing support services for DOD civilian employees seeking health care in Japan from local providers. This pilot program is intended to provide benefits supplementary to civilians’ health insurance plans and help with significant challenges DOD identified. The pilot program, which will run for 9 months and cost $4.2 million, will assist with upfront payment, establish direct billing agreements with additional providers, and establish a health care provider finder service.[30]

DOD civilian employees who are enrolled in a participating Federal Employees Health Benefits plan are eligible to participate in the pilot. In addition, civilians who are employed by businesses on military bases, such as restaurants or recreation centers, and are paid through revenues generated from those businesses rather than federal funds—referred to as nonappropriated fund civilian employees—are eligible to participate in this program if they are enrolled in the Aetna International Plan, part of the Nonappropriated Fund Health Benefits Program. However, contractors, dependents of active duty service members, dependents of civilian employees, and dependents of contractors are not eligible for the pilot.[31] Health Affairs has developed a communications strategy that includes a fact sheet and public affairs guidance to inform civilians about the program.

Additionally, Health Affairs established a draft evaluation plan in January 2025, during our review, to assess the results of the pilot program. Health Affairs plans to complete the analysis in April 2025 and issue an information paper in May 2025, in time for funding decisions to be made. Specifically, Health Affairs plans to analyze quantitative and qualitative data it collects from the pilot and issue an information paper evaluating results and determining whether the program should be continued or expanded to other populations, such as family members of civilian employees. Quantitative data are to include metrics related to utilization of the program, such as the number of calls to the provider finder service and the number of payments facilitated. Qualitative data are to include listening sessions with government employees and participating providers.

The draft evaluation plan also describes additional factors to be considered in the evaluation, including 1) changes in Federal Employees Health Benefits plan offerings and potential uptake of additional services, 2) willingness from contributing components with employees in Japan to continue funding the pilot, and 3) considerations for how offering this benefit could set precedents for other locations.

Zama Civilian Healthcare Navigator Program. U.S. Army Japan, in partnership with Japanese facility Zama General Hospital located near Camp Zama, established a health care translation and liaison program in October 2023. As part of this program, four full-time translators at Zama General, reallocated from U.S. Army Japan for this purpose, guide civilians and contractors assigned to Camp Zama and Atsugi through all stages of their medical appointments, from booking appointments through check-out and insurance claim filing.

According to officials, this program has been positively received. However, these officials stated it is not easily replicated in other locations due to the uniqueness of the proximity to and relationship with Zama General Hospital.

Behavioral health clinics. In February 2023, DOD asked the Army and Air Force Exchange Service (AAFES), an entity that pays for its own services with its revenues, if they could provide any services to civilians in Japan and provided data for AAFES to conduct a business case analysis, according to DOD and AAFES officials. AAFES determined there was a business case for behavioral health clinics at three locations in Japan and is in the process of opening the clinics at Camp Foster, Kadena Air Base, and Yokota Air Base in coordination with DOD.[32] These clinics will employ U.S. licensed providers and serve DOD civilian employees, contractors, and their families, and families of active duty service members, according to officials. Active duty service members will receive care at military medical facilities to ensure continuity of care.

According to DOD documentation, AAFES received command approval and approval from the Office of the Secretary of Defense for these three locations. According to DOD, two locations also have congressional approval, while Camp Foster approval was within the 30-day congressional comment period as of February 2025. Once approved, AAFES will begin contracting providers and renovating clinic spaces, according to officials. The clinics are projected to begin services by the second quarter of fiscal year 2026. A U.S. Forces Japan official noted that remote locations where behavioral health staff at the military medical facilities are smaller, would also benefit from these types of clinics.

Emergency care initiatives. In response to concerns about emergency medical care access in Japan, U.S. Forces Japan and DHA both conducted assessments of emergency care capabilities at military medical facilities.[33] DHA is implementing an action plan with 17 tasks, milestones, and time frames intended to ensure personnel receive timely emergency care at military medical facilities or in partnership with local Japanese providers.

Specifically, tasks include replacing aging ambulances at military medical facilities, replacing other key equipment and supplies, such as a sterilizer and an MRI machine, and using Japanese contractors to coordinate with military installations and the local health care system. Additionally, the plan includes efforts to improve care at Japanese facilities by discussing network adequacy with the international health care support contractor and identifying Japanese providers that require appointment coordination or interpreters.

As of February 2025, 10 out of 17 tasks had been completed. For example, DOD funded and scheduled trauma nursing courses and updated treatment protocols at military medical facilities. DOD has made some progress on other tasks, which have target completion dates through December 2025.

DOD Has Taken Steps to Address Some Capacity Challenges That Limit DOD-Affiliated Civilians and Families’ Access to Health Care in Guam and Has Plans to Address Others

DOD-Affiliated Civilians and Families Face Capacity Challenges in Accessing Health Care in Guam

Through interviews with DOD officials, a discussion group with DOD civilian employees in Guam, and analysis of DOD documentation, we identified three commonly cited challenges to accessing health care through local providers in Guam (see fig. 6). Though these challenges affect all who live in Guam, civilian employees we spoke to who are from Guam or who have lived there for many years described having more familiarity with the island’s health care system and doctors compared to hires from other parts of the United States.

Limited infrastructure. Guam Memorial Hospital, a public hospital that

is the island’s highest capacity medical facility, is in a state of severe disrepair.

According to an Army Corps of Engineers report, Guam Memorial suffers from

systemic failures due to environmental exposure, aging, and insufficient

funding for necessary repairs.[34]

The building lacks adherence to modern codes, and its condition puts it at risk

of failing accreditation. For example, most of Guam Memorial’s heating,

ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) equipment has exceeded its useful life

and needs replacement. The report notes that accelerated corrosion due to the

marine environment has caused significant damage to the hospital’s ductwork,

which the Army Corps of Engineers deemed unusable without repairs (see fig. 7).

The hospital’s HVAC problems create negative pressure within the hospital that

brings in humidity from outdoors, which causes mold and corrosion.

DOD civilians in our discussion group told us that they believe the overall

standard of care at local facilities, such as Guam Memorial Hospital, was

subpar. Some told us they feared receiving treatment there and have traveled

back to the mainland United States for surgeries.

The island’s two other hospitals are more modern. Guam Regional Medical City is a private hospital built in 2015. Naval Hospital Guam was built in 2014. These three facilities maintain around 330 beds in total, for a population of around 173,000. Guam has just 1.9 beds per 1,000 people—far below regional and U.S. averages. The U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration has qualified Guam as a Medically Underserved Area due to a shortage of health care services on the island.

Furthermore, DOD plans to increase the number of military service members, DOD-affiliated civilians, and families in Guam over the next decade as it enhances its missile defense capabilities in the region due to Guam’s increasing strategic importance in the Indo-Pacific. According to officials at Naval Hospital Guam, this could further strain the island’s health care infrastructure if new medical capacity does not keep pace. DOD has reported that it expects the strain of this personnel build up on an already overburdened medical system to be long-term and significant.[35]

Limited health care professionals. Like many rural and remote areas, Guam has a shortage of health care professionals. Guam is classified by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services as a Health Professional Shortage Area, a Medically Underserved Area, and a Maternity Care Target Area.[36] These designations demonstrate the island’s inadequacy and difficulty meeting health care needs. For example, Guam only has one gastroenterologist, a shortage of rehabilitation capacity, and shortfalls in pediatric care on island.

Guam struggles to attract and retain health care professionals from the mainland United States. This challenge is due to both Guam’s lower pay scale compared to similar positions in the mainland U.S., and to its remote location.

According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the difficulties in accessing care may lead to worse health outcomes by increasing the patients’ physical and emotional stress, reducing the likelihood of seeking care which may result in a worse condition than if easier access were available.

DOD civilians we spoke to also noted the limited availability of specialists. They shared that it is difficult to secure appointments, and some seek medical care abroad in the Philippines or South Korea because of this. Some DOD civilians also told us that mental health care is another area where the system falls short, particularly for children. They told us that they believe the behavioral health care options on island are inadequate and do not meet the community’s need.

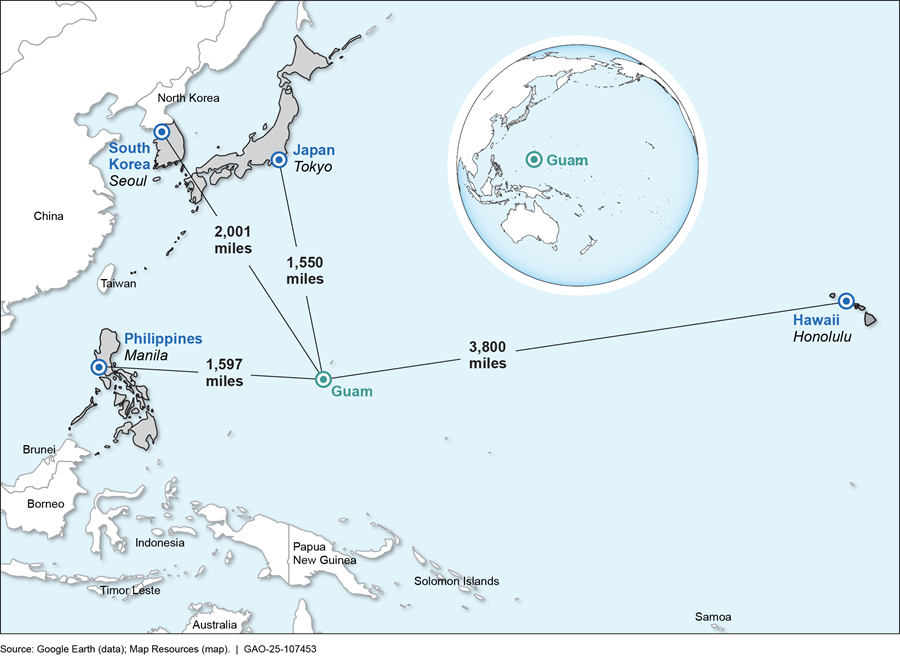

Geographic remoteness. Guam’s geographic remoteness contributes to and compounds its health care challenges. The U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration found that the costs of providing health care in Guam are relatively high due in part to its geographic location.[37] The shortage of health professionals is primarily because of difficulty recruiting providers due to Guam’s remote island setting, small scale, and territorial status. Guam’s remoteness also makes it challenging for DOD-affiliated civilians and families to access timely, specialized care off-island. The average flight time to the closest U.S. state is about 7 hours. Officials told us that patients needing both routine and specialized care often must travel to Hawaii or the Philippines to receive care.

DOD civilians told us that obtaining some essential medications is a persistent challenge due to the island’s geographic location. They noted the drugs are higher cost than in the mainland United States, there is more limited availability, there are shipping difficulties due to refrigeration requirements, and there are legal restrictions on certain drugs. Some told us that these challenges have forced them to seek alternative treatments that may be less effective or have adverse side effects.

Additionally, according to a Health Affairs official, the contractor supporting aeromedical evacuation from Guam relies on smaller aircraft that are leased in the United States and must island hop for refueling, which results in longer wait times for patients. This has caused a greater reliance on military aircraft, although Guam does not have a dedicated aeromedical evacuation aircraft on the island. Officials told us that this often requires them to use the smaller leased aircraft, which results in longer wait times for patients. Figure 8 below shows Guam’s location relative to selected countries.

DOD Has Taken Steps to Address Some Capacity Challenges in Accessing Health Care in Guam

Through interviews with DOD officials and review of DOD documentation, we identified DOD steps to address some challenges that DOD-affiliated civilians and families face accessing medical care in Guam. Many of these steps we identified are recent or planned, and it is too soon to determine their full effects.

Attempted no-cost land lease for new hospital. In spring 2023, DOD negotiated a no-cost land lease of about 113 acres with the Government of Guam for the construction of a new hospital on DOD property. According to DOD officials, the hospital would have included a pediatric intensive care unit; an inpatient hemodialysis capability; large helicopter-capable helipad for patient transfer; an inpatient rehabilitation capability with services including inpatient physical, occupational and speech therapy; and capacity for a DOD field hospital expansion if needed. However, the lease was ultimately not signed because the Guam legislature passed a law that halted the process.[38] The Guam government plans for construction of a new hospital to replace Guam Memorial Hospital without the DOD land lease and is currently working to select a plot of land and secure sufficient funding.

DOD grant to upgrade HVAC at Guam Memorial Hospital. In September 2024, the DOD Office of Local Defense Community Cooperation provided a $2.7 million Defense Community Infrastructure Program grant to the Guam Memorial Hospital Authority for the upgrade of its HVAC system. This project plans to incorporate advanced energy-efficient technologies to reduce energy consumption and operational costs and address critical infrastructure needs of the current HVAC equipment that has exceeded its useful life. DOD intends to directly support the health and readiness of military personnel who rely on Guam Memorial Hospital through this investment, assisting operational readiness and mission capability.[39] The upgrade will also benefit DOD-affiliated civilians and families who receive care at the hospital.

Plans to expand military medical facility capacity. According to DOD documents, DOD is assessing its needs to increase medical capacity at three military medical facilities corresponding to the planned growth in the military population on Guam. Increased capacity at military medical facilities could also potentially increase the amount of space-available care for DOD-affiliated civilians and families, according to DOD officials. For example, a senior official told us that DOD is developing plans to increase staff at Naval Hospital Guam (see fig. 9). The official explained that a working group recently recommended approximately 244 additional staff at the hospital to meet demand from new growth through 2037. Additionally, senior officials told us DOD will open a new military medical facility at Camp Blaz in fall 2025 that will serve active duty service members only, providing capacity to the overall health care ecosystem on Guam.

DOD established the Guam Medical Sub-Working Group co-chaired by Health Affairs

and the Joint Staff Surgeon to address issues related to health care access

that may continue to arise given its planned growth of service members and

family members in Guam. In December 2024, DHA began formal working group

discussions along with the military services to review and validate medical

staffing requirements to support growth through fiscal year 2037. With planned

redeployments of Marines and dependents from Okinawa as well as deployments to

support the Guam Missile Defense System, the department anticipates growth in

the civilian population and significant effects on DOD support services

including medical. We have ongoing work related to Guam missile defense including

the adequacy of infrastructure to support military personnel.[40]

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to DOD for review and comment. DOD provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Defense, the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness, the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs, the Director of the Defense Health Agency, the Secretaries of the Army, the Navy, and the Air Force, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at agarwalr@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix II.

Rashmi Agarwal

Acting Director, Defense Capabilities and Management

Section 726 of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024 includes a provision that we review health care available overseas to U.S. civilians and contractors who support U.S. Forces Japan and Joint Region Marianas (Guam), their dependents, and certain dependents of active duty service members.[41]

In this report we examine

1. how often Department of Defense (DOD)-affiliated civilians and families accessed health care at military medical facilities in Japan and Guam;

2. the challenges these individuals faced accessing health care through local providers in Japan, and the extent DOD is addressing any challenges; and

3. the challenges these individuals faced accessing health care through local providers in Guam, and the extent DOD is addressing any challenges.

For the first objective, we reviewed DOD policy, guidance, and federal law on requirements and priorities for accessing care at military medical facilities. We also interviewed officials from DOD, the Office of Personnel Management, and the State Department about civilian and contractor access to health care and insurance.

We analyzed data from DHA on space-available visits at military medical facilities in Japan and Guam—that is, the number of visits DOD-affiliated civilians and families made to military medical facilities when capacity allowed at the facility. The data we present in this report are for all space-available visits, not only visits by individuals directly supporting DOD missions in Japan and Guam as a civilian employee or contractor, because this cannot be distinguished in the data. Though the data include civilian employees, contractors, and dependents, it also may include veterans or retirees who are not civilian employees or contractors. The Defense Health Agency’s definition of space-available at overseas locations is any visit by an individual without TRICARE Prime Overseas.

We analyzed data beginning in fiscal year 2019 because it was before the COVID-19 pandemic and through fiscal year 2024 because it was the most recent data available. To ensure data reliability, we reviewed relevant documentation, checked for missing data or obvious errors, and interviewed agency officials knowledgeable about the data. We determined that in combination, these data were sufficiently reliable to report on the number of space-available visits.

For the second and third objectives, we interviewed DOD officials, including officials from U.S. Forces Japan, Joint Region Marianas, Health Affairs, DHA, and the military departments. We also interviewed an advocacy group for civilians in Japan and collected documentation.

In addition, we held five nongeneralizable, in-person, discussion groups with randomly selected DOD civilians at four locations in Japan and one in Guam about their access to health care; specifically, we held the discussion groups in Okinawa, Yokosuka, Yokota, and Zama in Japan, alongside one in Guam.

We selected participants for the discussion groups by randomly selecting from lists of DOD civilians employed at these locations. We then contacted the selected participants directly to ask for their participation. Participation was voluntary. The number of individuals who ultimately participated in each group ranged from five to 14. We identified the common themes in these groups related to experiences using local health care facilities in Japan and Guam, and experiences using military medical facilities on a space-available basis.

To examine the extent DOD is addressing any challenges, we interviewed DOD officials and reviewed documentation related to plans and ongoing initiatives aimed at alleviating challenges for DOD-affiliated civilians and families accessing health care.

We conducted this performance audit from March 2024 to April 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

GAO Contact

Rashmi Agarwal, agarwalr@gao.gov.

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Lori Atkinson (Assistant Director), William Tedrick (Analyst in Charge), Sharon Ballinger, Joyee Dasgupta, Alexandra Gonzalez, Samuel Harbaugh, Jacob Harwas, Lillian Ofili, Walter Vance, Emily Wilson, and Michael Zose made key contributions to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on Facebook, Flickr, X, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our RSS Feeds or Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7700

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]Defense Health Agency Region Indo-Pacific Administrative Instruction, Space Available Medical Care in Military Medical Treatment Facilities within the Defense Health Agency Region Indo-Pacific (Dec. 22, 2022). DOD had previously issued policies in 2011 and 2018. Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs, TRICARE Policy for Access to Care (Feb. 23, 2011). Defense Health Agency Procedural Instruction, Processes and Standards for Primary Care Empanelment and Capacity in Medical Treatment Facilities (Oct. 9, 2018).

[2]In this report, we use the phrase “not guaranteed care” to refer to how individuals may receive care only on a space-available basis, based on priorities for care in 32 C.F.R. § 199.17(d)(1).

[3]Defense Health Agency Memorandum, Standard Guidance for Space-Available Care in Military Medical Treatment Facilities (Mar. 3, 2023).

[4]National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024, Pub. L. No. 118-31, § 726 (2023). In this report, we use the term “DOD-affiliated civilians and families” to refer to those individuals who support DOD missions in Japan and Guam but are not guaranteed care at a military medical facility. This includes U.S. civilian employees of the federal government and employees of DOD contractors who support the mission of United States Forces Japan or Joint Region Marianas, their dependents, and certain dependents of active duty service members.

[5]The data we present in this report are for all space-available visits, not only visits by individuals directly supporting DOD missions in Japan and Guam as a civilian employee or contractor, because this cannot be distinguished in the data. Though the data includes civilian employees, contractors, and dependents, it also may include, for example, some retirees or veterans who are not civilian employees or contractors.

[6]We selected participants for four discussion groups in Japan and one in Guam by compiling lists of DOD civilians employed at these locations and randomly selecting individuals. The number of participants in each group ranged from five to 14.

[7]Department of Defense Directive 5124.02, Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness (USD(P&R)) (June 23, 2008) (incorporating change 1, Dec. 11, 2024).

[8]Department of Defense Directive 5136.01, Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs (ASD(HA)) (Sept. 30, 2013) (incorporating change 1, Aug. 10, 2017).

[9]Department of Defense Directive 5136.13, Defense Health Agency (Sept. 30, 2013) (incorporating change 2, effective Sep. 12, 2023).

[10]The Federal Employees Health Benefits Program is the largest employer-sponsored health care program in the country and provides health insurance benefits to federal employees, retired federal employees, other eligible individuals, and their eligible family members.

[11]DOD nonappropriated fund civilian employees are eligible for the DOD Nonappropriated Fund Health Benefits Program, administered by the Defense Civilian Personnel Advisory Service. Nonappropriated funds are government funds from sources other than those appropriated by Congress. For example, Armed Services Exchange programs that operate stores, restaurants, and other services on military bases, pay personnel with their own revenues. Such personnel are referred to as nonappropriated fund civilian employees.

[12]Department of Defense Instruction 6000.19, Military Medical Treatment Facility Support of Medical Readiness Skills of Health Care Providers (Feb. 7, 2020).

[13]Defense Health Agency Memorandum, Standard Guidance for Space-Available Care in Military Medical Treatment Facilities (Mar. 3, 2023).

[14]In some instances, federal civilian employees or contractors may have a connection to active duty service (e.g., a command-sponsored active duty family member) and have a form of military insurance (TRICARE) that allows them to be guaranteed treatment at military medical facilities.

[15]32 C.F.R. § 75.6 (2019); 5 U.S.C. § 2302; and 29 U.S.C. §§ 791-794d.

[16]S. Rep. No. 115-125, at 147-148 (2017).