MARITIME ADMINISTRATION

Actions Needed to Help Address Workforce Challenges

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO-25-107460. For more information, contact Andrew Von Ah at (202) 512-2834 or VonAhA@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107460, a report to congressional committees

Actions Needed to Help Address Workforce Challenges

Why GAO Did This Study

MARAD is tasked with fostering, promoting, and developing the U.S. maritime industry to meet the nation’s economic and security needs. MARAD’s wide-ranging responsibilities makes workforce planning critically important. Strategic human capital management across government is an issue on GAO’s High Risk List. In July 2024, MARAD hired a contractor to help the agency develop a strategic workforce plan.

This report examines (1) current workforce challenges MARAD faces, (2) how MARAD is addressing its workforce challenges, and (3) the extent to which MARAD has incorporated key workforce planning principles into its strategic workforce plan.

GAO reviewed MARAD policies, procedures, and documents related to the agency’s strategic workforce planning efforts. GAO also interviewed MARAD and Department of Transportation officials and analyzed MARAD data. GAO evaluated the information from documents and interviews against key workforce planning principles.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making four recommendations, including that MARAD assess critical skills and develop a strategy to address any future skill gaps identified in the forthcoming strategic workforce plan. The Department of Transportation agreed with our recommendations.

What GAO Found

Renewed interest in revitalizing America’s maritime industrial base has driven interest in the sufficiency of the workforce at the Department of Transportation’s Maritime Administration (MARAD). While MARAD’s budget grew by approximately 314 percent from fiscal years 2015 through 2024, the agency faces staff turnover and numerous vacancies in key positions. As of September 2024, MARAD had a 12.3 percent vacancy rate—116 vacancies out of 941 authorized full-time positions. In addition, MARAD separated 235 more employees than it hired over the last 10 years. According to MARAD officials, these vacancies have made it increasingly difficult for the staff to accomplish their mission. Furthermore, the number of retirement-eligible staff is projected to increase, from 24 percent in 2024 to 43 percent by calendar year 2029 (see fig.). To address these challenges, MARAD has expanded the use of hiring flexibilities to help recruit qualified candidates, begun employee engagement efforts, and developed a recruitment and outreach plan. In July 2024, MARAD hired a contractor to develop a strategic workforce plan. Agency officials expect the plan to be completed in September 2025.

GAO found that MARAD has not fully implemented key strategic workforce planning principles into its forthcoming strategic workforce plan. For example, GAO has previously reported that agencies should determine critical skills needed to achieve current and future goals and assess any skill gaps. MARAD officials said that the contractor will conduct a workforce analysis that includes identifying workforce competencies and skills as part of the forthcoming workforce plan. However, the agency has yet to fully determine future skills that may be needed. Individual program offices, such as the office of Shipyards and Marine Engineering, told GAO that they anticipate needing additional expertise in certain skillsets, such as cybersecurity and artificial intelligence, in the years ahead. However, MARAD has not yet determined overall how it will assess future skill gaps such as these, or other skills, needed within the agency as a whole. MARAD officials said they have not fully assessed the workforce skills needed because the strategic workforce plan is still in development. Nevertheless, without fully determining the skill gaps needed to achieve future results and developing a strategy to address them, MARAD will not have assurance that its workforce is best positioned to meet current and future mission needs.

Abbreviations

|

Academy |

U.S. Merchant Marine Academy |

|

DOD |

Department of Defense |

|

DOT |

Department of Transportation |

|

IIJA |

Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act |

|

MARAD |

Maritime Administration |

|

NDAA |

National Defense Authorization Act |

|

NEPA |

National Environmental Policy Act |

|

NSMV |

National Security Multi-Mission Vessel |

|

SES |

Senior Executive Service |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

February 13, 2025

The Honorable Ted Cruz

Chairman

The Honorable Maria Cantwell

Ranking Member

Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation

United States Senate

The Honorable Sam Graves

Chairman

The Honorable Rick Larsen

Ranking Member

Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure

House of Representatives

The Maritime Administration (MARAD), within the Department of Transportation (DOT), is tasked with the mission to foster, promote, and develop the U.S. maritime industry to meet the nation’s economic and security needs. This involves supporting ships and shipping, port and vessel operations, national security, environmental stewardship, and maritime safety, as well as maintaining the well-being of the U.S. Merchant Marine. Altogether, MARAD, with its approximately 800 employees, is responsible for carrying out a wide variety of statutes across the agency’s mission areas.[1] In recent years, we have made recommendations regarding MARAD’s ability to develop a national maritime strategy, enforce cargo preference laws, and oversee capital improvement projects at the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy.[2] MARAD’s wide range of responsibilities makes human capital planning critically important for the agency to be able to meet its mission.

Currently, MARAD does not have a strategic human capital plan, as its most recent plan expired at the end of fiscal year 2022. In March 2024, MARAD issued an agency-wide strategic plan covering fiscal years 2022 to 2026. This overarching strategic plan identified the need to develop an updated, 5-year strategic human capital plan. In July 2024, MARAD selected a contractor to begin the development of a new strategic human capital plan, according to MARAD officials.

We have reported extensively on federal workforce needs, and strategic human capital planning is on our High Risk List.[3] Strategic workforce planning aligns an organization’s human capital program with its current and emerging mission. Additionally, we have reported that developing long-term strategies for acquiring, developing, and retaining staff allows agencies to achieve programmatic goals.[4] According to MARAD officials, given the agency’s wide range of responsibilities, maintaining and developing an effective workforce will continue to be important for the agency.

Section 3533 of the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year 2024 contains a provision for GAO to review the Maritime Administration’s staffing requirements and any staffing challenges that could impede MARAD’s operations. This report examines (1) the current workforce challenges MARAD faces, (2) how MARAD is addressing its workforce challenges, and (3) the extent to which MARAD has implemented key workforce planning principles into its strategic workforce planning efforts.

To address all three objectives, we reviewed applicable policies, procedures, and documents related to MARAD’s current workforce, as well as its strategic workforce planning efforts. This includes DOT’s and MARAD’s fiscal year 2022-2026 strategic plans, MARAD’s Fiscal Year 2017-2022 Strategic Human Capital Plan, the statement of work for MARAD’s forthcoming strategic workforce plan, and MARAD’s budget estimates from fiscal years 2015 through 2025. For the purposes of this report, we refer to MARAD’s forthcoming 5-year strategic human capital plan as its strategic workforce plan.

To examine MARAD’s current workforce challenges and how MARAD is addressing them, we interviewed officials from DOT’s Departmental Office of Human Resource Management and MARAD officials, including MARAD leadership and human resource officials. We interviewed MARAD officials from six program offices, selected to cover a broad range of MARAD’s primary missions, including strategic sealift, ports and waterways, environment and compliance, and shipyards and marine engineering, as well as public affairs and legislative affairs. In addition, we interviewed five maritime industry stakeholders that we selected based on our prior maritime work. We also reviewed DOT and MARAD data and information on the agency’s workforce, including numbers of full-time positions, vacancy rates, turnover rates, and retirement eligibility data ranging from fiscal years 2013 through 2029. For these data, we reviewed the steps MARAD takes to ensure the accuracy of its data and asked MARAD questions about the data and MARAD’s processes to ensure data reliability. We determined that the data provided were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of reporting MARAD budget information and workforce data ranging from fiscal years 2013 through 2029.

To assess the extent to which MARAD has implemented key workforce planning principles into its strategic workforce planning efforts, we reviewed key principles of strategic workforce planning outlined in our prior work.[5] We validated these criteria against the workforce planning principles contained in the Office of Personnel Management’s Workforce Planning Guide that includes its workforce planning model, which is complementary to our principles.[6] We then reviewed and assessed the documentation MARAD provided and the information gathered from the aforementioned interviews against the five GAO key workforce planning principles.

We determined that MARAD had fully implemented a strategic workforce planning principle into its strategic workforce planning efforts if it provided both sufficient documentary and testimonial evidence to support the claim. We determined the principle was partially implemented if MARAD officials provided sufficient testimonial evidence to suggest that significant work had been done but did not have corroborating documentary evidence. We also determined that a principle was partially implemented if MARAD was able to produce both documentary and testimonial evidence that the principle would be met by planned future efforts. We determined that a principle was not implemented if MARAD could not provide either sufficient documentary or testimonial evidence to support the claim.

We conducted this performance audit from March 2024 to February 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Key Principles for Strategic Workforce Planning

Strategic human capital management for federal agencies, which includes workforce planning activities, has been on our High Risk list since 2001 in part because unaddressed current and emerging skills gaps can undermine an agency’s ability to meet its missions.[7] We have reported that current budget and long-term fiscal pressures, the changing nature of federal work, and a potential wave of employee retirements that could produce gaps in leadership and institutional knowledge threaten to aggravate the problems created by existing skills gaps.[8] Mission-critical skills gaps both within federal agencies and across the federal workforce continue to pose a high risk to the nation because they can impede the government from cost-effectively serving the public and achieving results.[9] To help address this risk, we developed five principles for effective workforce planning that can help agencies focus on significant issues, relevant information, and valuable lessons from other organizations’ experiences. These principles are

· Principle 1: Involve top management, employees, and other stakeholders in developing, communicating, and implementing the strategic workforce plan;

· Principle 2: Determine the critical skills and competencies that will be needed to achieve the future programmatic results;

· Principle 3: Develop strategies tailored to address gaps and human capital conditions in critical skills and competencies that need attention;

· Principle 4: Build the capacity needed to address administrative, educational, and other requirements important to supporting workforce strategies; and

· Principle 5: Monitor and evaluate the agency’s progress toward its human capital goals and the contribution that human capital results have made toward achieving programmatic goals.[10]

MARAD Responsibilities and Major Program Offices

MARAD’s mission is to foster, promote, and develop the U.S. maritime industry to meet the nation’s economic and security needs. MARAD’s wide-ranging responsibilities include dozens of statutory requirements across MARAD’s mission areas.[11] These authorities include maintaining the National Defense Reserve Fleet and the marine highway transportation program, among others. MARAD’s major program offices are responsible for carrying out the agency’s responsibilities, examples of which include the following:

· Office of Strategic Sealift. Administers national security-related programs that provide commercial and government-owned shipping capability in times of national emergency and to meet Department of Defense (DOD) strategic sealift needs.[12] The Office of Strategic Sealift is the largest program office within MARAD, with over 300 staff in fiscal year 2024. Central to this office’s operations is maintaining and operating the National Defense Reserve Fleet, a fleet of merchant-type vessels maintained in readiness status to support DOD and other federal agencies. Other responsibilities for this office include emergency preparedness planning, administering ship disposal, providing services with respect to the application of cargo preference statutes, and managing the Centers of Excellence program and other maritime labor and training programs.[13] The office is also responsible for providing support to the State Maritime Academies program, which includes administering and promoting the Student Incentive Program for tuition assistance and monitoring compliance by the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy (Academy) and State Maritime Academy students with their service obligations.

· Office of Ports & Waterways. Assists with port, terminal, waterway, and transportation network development issues. The office supports efforts by port and industry stakeholders to improve facility and freight infrastructure to help meet freight transportation needs and help increase the use and efficiency of the maritime transportation system. This includes providing support for national port and intermodal infrastructure projects and programs, deepwater port licensing, and overseeing port conveyance. The office also administers related grant funding made available by the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA)[14] and yearly congressional appropriations for the Port Infrastructure Development Program and U.S. Marine Highway program. Additionally, the office oversees MARAD’s 10 gateway offices, which provide a day-to-day maritime transportation presence at regionally significant ports throughout the U.S. The office also oversees the agency’s Maritime Transportation System National Advisory Committee. This committee provides an industry stakeholder perspective on matters relating to the U.S. maritime transportation system and its integration with other segments of the transportation system, including the viability of the U.S. Merchant Marine.

· Office of Environment and Compliance. Conducts National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) reviews for grant applications submitted to MARAD and oversees the NEPA review process for successful applicants.[15] This includes grant programs administered by MARAD, such as the Port Infrastructure Development Program, Small Shipyard Grant Program, and the U.S. Marine Highway Program. The office oversees the NEPA program in support of all MARAD missions. In addition, the office provides environmental compliance support to MARAD programs and operations, including the Academy, ship operators and disposal, the Ready Reserve Fleet and National Defense Reserve Fleet, and associated fleet sites. According to MARAD officials, this support covers a wide range of environmental laws, regulations, standards, and executive orders. The office collaborates with federal and industry partners to maintain maritime domain awareness and minimize the potential for cyber, pirate, and terrorist attacks against maritime assets. Additionally, the office participates in developing maritime safety standards, promoting safety awareness, and developing improved safety-related technology and practices.

· Office of Business and Finance Development. Provides support on broad national maritime policies and programs, including oversight of Assistance to Small Shipyard grants; MARAD’s capital construction and reserve funds; marine insurance and marine war risk insurance activities; and programs related to U.S. shipbuilders, ship repairers, and suppliers.

· U.S. Merchant Marine Academy. MARAD oversees the Academy, which is the nation’s only federal service academy dedicated to educating mariners to serve the national security, marine transportation, and economic needs of the U.S. as licensed Merchant Marine Officers and as commissioned officers in the Armed Forces. Approximately 270 of MARAD’s 825 full-time employees work at the Academy and, as of September 2024, 953 students were enrolled at the Academy’s campus in Kings Point, New York, according to MARAD officials. Academy graduates can serve as licensed officers on commercial vessels with a reserve duty component or active duty in the military.

Personnel Trends and Persistent Vacancies Pose Challenges for MARAD

MARAD’s Budget Has Grown, but Staffing Trends Pose Challenges

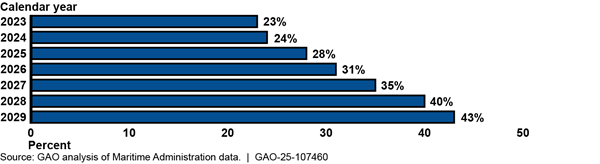

The funding to administer MARAD programs has grown over the last 10 fiscal years, though the personnel resources to carry out additional agency responsibilities have remained generally steady. While MARAD’s annual budget grew by approximately 314 percent from fiscal years 2015 through 2024, its number of employees has remained relatively steady, at around 800 (see fig. 1). MARAD’s overall budget has generally increased over the last 10 years, largely due to the addition of new maritime grant programs, as well as funding from Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act appropriations, according to MARAD officials. For example, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act provided $2.25 billion over fiscal years 2022 through 2026 for the Port Infrastructure and Development Program, which awards competitive grants to modernize, among other things, coastal and inland waterway ports.[16] In addition, MARAD was authorized two new programs—the Tanker Security Program and Cable Security Fleet Program—both of which are intended to ensure the availability of certain types of vessels for the U.S.[17] Though MARAD’s budget has generally increased in recent years, it represents only a fraction of DOT’s overall budget. For example, in fiscal year 2024, MARAD’s $1.4 billion budget accounted for less than 1 percent of the total DOT budget.

Figure 1: Maritime Administration (MARAD) Budget and Number of Employees, Fiscal Years 2015 through 2024

aThe Office of Personnel Management data measure employment, which the office defines as “a measure representing the number of employees in pay status at the end of the quarter (or end of the pay period prior to the end of the quarter).”

bFiscal year 2024 data are from March 2024, the latest data available from the Office of Personnel Management.

Renewed interest in revitalizing America’s maritime industrial base has helped drive the desire for MARAD to grow its shipbuilding capability. For example, in May 2024, the Secretary of the Navy highlighted the importance of reviving the maritime industry in the U.S., to include reviving shipbuilding, shipbuilding facilities, acquiring additional vessels, and increasing the number of available mariners. In addition, the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2017 required the Secretary of Transportation and MARAD to take specified actions toward the construction of the National Defense Reserve Fleet National Security Multi-Mission Vessel (NSMV), the construction of which is administered by MARAD.[18] Two of these new NSMV vessels have been delivered, and three are currently scheduled to be delivered by 2027. The NSMV is a new class of purpose-built ships to replace the current training ships used by the State Maritime Academies.

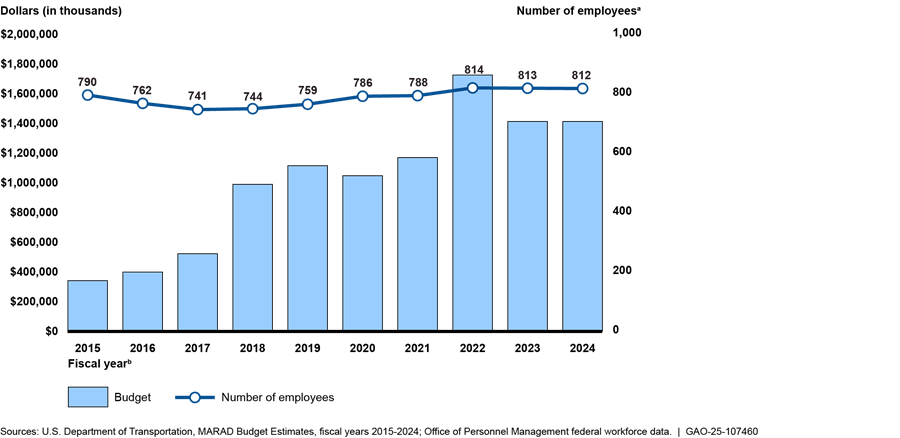

Although MARAD requested additional full-time employees in seven of its last 10 budget requests, over the same period the agency has faced a deficit in which more employees left the agency than were hired. Specifically, the agency separated a total of 235 more employees than it hired between fiscal years 2015 and 2024. From fiscal years 2015 through 2024, MARAD had more employee separations than new hires in 7 of the 10 years (see fig. 2).

Figure 2: Maritime Administration (MARAD) Separations versus New Hires, Fiscal Years 2015 through 2024

Note: The separations represented in these data include employees who left the agency but do not include retirements and employees who transferred from MARAD to other operating administrations within the Department of Transportation.

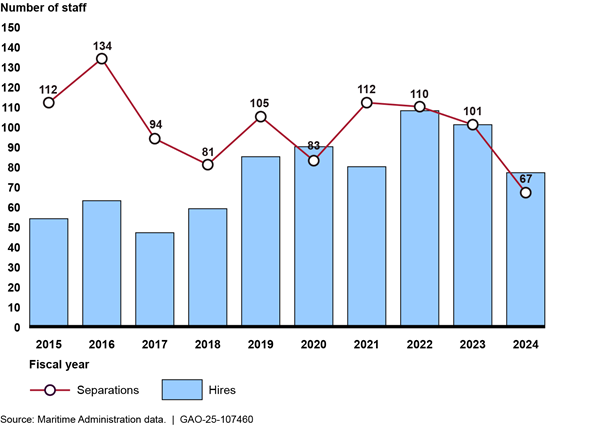

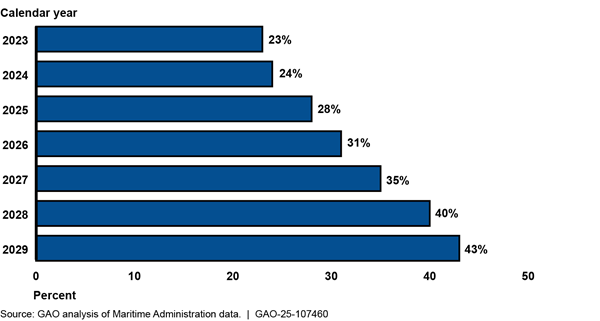

As MARAD separations have outpaced new hires over the last decade, looking forward, increasingly more of the agency’s workforce will reach retirement age. For example, in calendar year 2023, 23 percent of the MARAD workforce was eligible for retirement and, by 2029, 43 percent of the workforce will be retirement eligible, according to our analysis of MARAD data (see fig. 3).

Vacancies Exist in Key Positions Across MARAD, Causing Challenges for Agency Officials

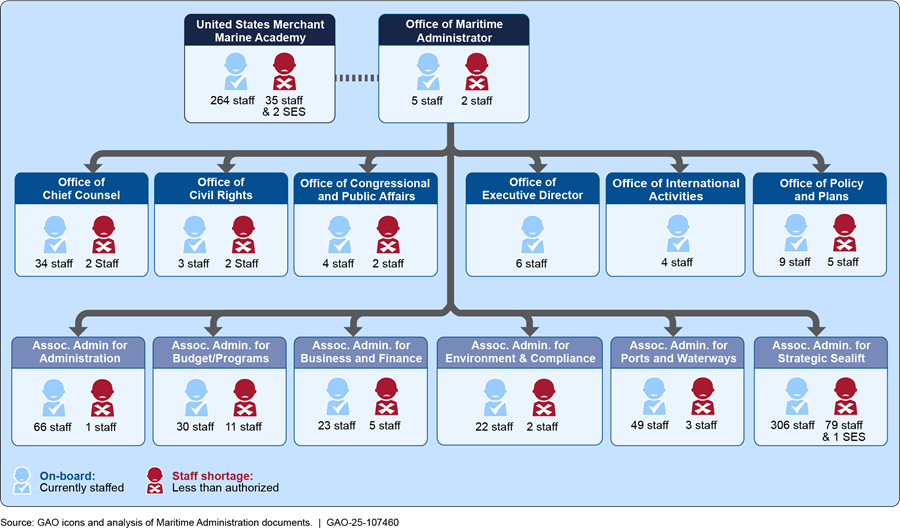

In September 2024, MARAD filled 825 of its 941 authorized full-time positions across the agency. The agency was operating with 116 vacancies, a 12.3 percent vacancy rate.[19] According to MARAD officials, in part because of the renewed focus on shipbuilding, the majority of these vacancies are due to the agency’s decision to add 104 positions to the Office of Strategic Sealift in May 2024 to meet shifting mission needs. As of October 2024, these positions had not yet been filled. All MARAD offices, except the Office of International Activities and the Office of the Executive Director, reported a shortage of filled authorized positions (see fig. 4).[20] The largest office in MARAD, Strategic Sealift, had 79 vacancies. In May 2024, vacancies in Strategic Sealift included four Ready Reserve Force program managers and a Director of Ship Operations. The Office of Environment and Compliance also had four vacancies, including three environmental protection specialists, in May 2024.

Figure 4: Current Authorized Staff and Senior Executive Service (SES) Positions and Vacancies within the Maritime Administration, September 2024

Note: Authorized staff counts in this figure exclude positions authorized under the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, as the Maritime Administration does not include those positions in calculating the agency’s vacancy rate.

According to MARAD officials we met with, vacancies have had a negative impact on their ability to complete their work. MARAD program officials in all offices we spoke with described handling workloads that exceeded available staff resources. For instance, in the Office of Ports & Waterways, officials said that when managing grants, their goal is to have a workload of no more than 30 grants per staff member, but each staff member currently has between 42 and 45. The officials said the current grant workload will become unsustainable, and they need at least six additional staff to bring their workload to a manageable level. They also said they anticipate needing even more staff in the future, if the workload continues to grow. Officials from the Office of Environment and Compliance told us they need additional staff in order to manage their grant workload. As of August 2024, eight members of their staff have 150 active NEPA projects to review. At that time, most staff members were assigned around 20 projects to review, with one staff member assigned over 30 projects to review.

MARAD officials also described to us how the high number of vacancies affects their ability to accomplish their mission. For example, officials from the Office of Strategic Sealift told us that one staff member is responsible for managing the entire Maritime Security Program—which covers 60 ships and approximately $318 million in funding—while another staff person is responsible for $388 million in invoicing. Strategic Sealift officials told us that while this work is labor intensive, they are able to get their necessary work done in a peacetime environment. However, Strategic Sealift officials also told us they do not have sufficient staff to back up certain roles if the primary staff member is on leave or otherwise absent. Given their current staffing shortages, they do not believe they would be able to respond quickly in the event of a national emergency or large-scale war effort.

Additionally, officials from the Office of Legislative Affairs told us that one of their responsibilities is the tracking of all deliverables MARAD owes to Congress. This includes 23 separate deliverables required by the James N. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 alone, according to officials. Program officials described this tracking responsibility as “a full-time job,” but the two staff members are also responsible for numerous other tasks. As a result, Legislative Affairs officials told us that they cannot efficiently fulfill their remaining duties, such as keeping Congress informed about MARAD initiatives—a key role to support the agency’s mission of promoting the maritime industry.

At the Senior Executive Service (SES) level, there were three vacancies across MARAD and the Academy as of September 2024. MARAD officials said that it has been challenging to fill these vacancies largely because of the unique expertise they require. For example, MARAD officials told us it took two hiring rounds to select a new Director of the Committee on the U.S Marine Transportation System, because they did not receive enough qualified applicants in the initial round. Officials also told us that an ideal SES candidate would have former military experience, in addition to commercial maritime experience, which can be a difficult combination of skillsets to find in a candidate.

According to MARAD officials, the agency has filled some of these SES-level vacancies with acting or temporary appointments working on detail from other offices in MARAD or from other DOT operating administrations. For example, a 2-year detailee from the Federal Aviation Administration is currently filling the Director of the Office of Facilities and Infrastructure role at the Academy. As we previously reported, in the absence of continuous leadership and a dedicated team for the Office of Facilities and Infrastructure, the Academy does not have assurance that it will be able to implement projects from its upcoming real property master plan alongside ongoing maintenance of the campus.[21] In August 2024, MARAD officials told us they had posted a job announcement for a permanent appointment to this position, as the current detail ends in November 2024.

According to MARAD officials we met with, some SES-level vacancies have had to rely on acting administrators to temporarily fill the position, while others were permanently appointed following multiple rounds of hiring. For example, an acting associate administrator oversaw the Office of Environment and Compliance for 17 months. Another acting associate administrator oversaw the Office of Strategic Sealift for 9 months, until the individual was assigned to the position permanently. In some cases, an acting associate administrator in MARAD will manage the responsibilities of both the acting and original positions. According to officials in the Office of Strategic Sealift, the acting associate administrator can have difficulty devoting sufficient time to the programs they oversee while also meeting the responsibilities of both positions. Strategic Sealift officials also said that routine work, such as setting program priorities, responding to outside stakeholders, and program administration, can take more time under an acting administrator.

Compounding the challenges posed by existing vacancies, in fiscal year 2023, MARAD experienced a higher overall employee turnover rate— 6.1 percent—than the DOT-wide rate of 2.6 percent, according to agency data. This rate was also higher than several other DOT operating administrations, including the 4.8 percent turnover rate at the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration and the 2.1 percent turnover rate at the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, which are both similarly sized to MARAD.[22] MARAD officials noted that the postpandemic future of work issues, such as the ability to work from home offered by other federal agencies and civilian employers, has made it challenging to retain talent. Officials also said that employees identified issues in the Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey, such as the need for consistent leadership and better communication, that have made their experience challenging. According to program officials in Strategic Sealift, there is also high turnover at lower-level positions, requiring that new staff be trained repeatedly. In fiscal year 2023, MARAD’s turnover rate for staff with 3 years of service or less was 3.5 percent, which was also higher than the DOT-wide rate of 1.3 percent.

Program officials also noted that it was difficult to dedicate time to training their staff because of their elevated workloads and staffing shortages. Officials in Public Affairs also said they would benefit from training in defense information, photography, public speaking, and media relations skills but do not have sufficient staff to accommodate the office’s existing workload while others are training. In addition, program officials described a need to invest in training for current positions to improve program offices’ future capabilities. For example, officials from the Office of Shipyards and Marine Engineering said their staff need more expertise in electric propulsion systems, cybersecurity, and artificial intelligence, as these technologies will be used in future ship designs.

According to MARAD officials, addressing future national defense needs will place increased demands on the agency’s workforce. Officials noted that MARAD is already experiencing increased demands and expects the agency’s mission to expand due to increased maritime threats the U.S. is experiencing. In their view, responding to these and future threats will require MARAD to address deficiencies in shipbuilding facilities, the type and number of operating vessels, and the number of available mariners. MARAD officials told us that, given the renewed focus on shipbuilding, if a fully funded new construction shipbuilding program is enacted in the future, additional full-time employees would be required. They noted that the specific number of new employees would be determined by the scale of the enacted shipbuilding program and the scope of responsibility, and many would fall within the Office of Strategic Sealift, which was operating with 79 vacancies as of September 2024.

MARAD Is Working to Fill Vacancies and Is Developing a Strategic Workforce Plan to Help Address Challenges

MARAD Is Taking Steps to Fill Vacancies and Retain Employees Across the Organization but Continues to Fall Short of Its Targets

As of September 2024, MARAD officials told us they were actively recruiting for 128 positions across the agency, about 14 percent of its total authorized positions. To help facilitate this effort, in February 2023, MARAD developed a new recruitment and outreach plan for fiscal years 2023 through 2026 based on workforce demographics, retirement eligibility, and mission-critical occupations. The plan includes three priorities: (1) Addressing workforce skills gaps through recruitment, (2) Recruiting entry and midcareer talent to mitigate MARAD’s high retirement eligibility, and (3) Increasing the representation of minorities and women in MARAD’s workforce. MARAD officials told us that in fiscal years 2022 and 2023, MARAD onboarded 100 employees, the highest number since 2013. Additionally, a MARAD employee resource group recommended that leadership reduce time-to-hire and improve the candidate experience. However, as of September 2024, MARAD’s 149 vacancies continue to exceed the number of active recruitments.[23]

According to data from the Office of Strategic Sealift, the time taken by the hiring process often exceeded targets that the office had set. Officials from the Office of Strategic Sealift and the Office of Human Resources said that the hiring process took longer to complete because of limited staff to support the hiring process. Other program officials said they had difficulty recruiting candidates with specialized or niche qualifications. MARAD officials said that Human Resources officials work closely with the Office of Strategic Sealift to address their workforce needs, meeting weekly to discuss them. However, Strategic Sealift officials said that by the time they scheduled interviews, about half of the candidates deemed interview-worthy had accepted other job offers. While filling another vacancy, officials in the Office of Shipyards and Marine Engineering said they had difficulty recruiting candidates with backgrounds in marine finance. Instead, the office received applications from candidates with budget experience, which is a different specialization. As a result, officials said it took over 3 years to fill this position with a qualified candidate.

MARAD officials we met with said that they were taking steps to address these issues by (1) expanding use of hiring flexibilities, (2) rewriting position descriptions, and (3) developing employee engagement initiatives to improve retention.

· Expanding use of hiring flexibilities. MARAD leadership said that the agency was expanding the use of direct hire authorities and other hiring flexibilities to address vacancies and cover more types of positions.[24] For example, MARAD officials said the agency has filled 31 positions through direct hire authority since January 2023. Since 2022, MARAD has also used pay incentives to attract 46 candidates with superior qualifications. According to data from OST, MARAD utilized student loan repayment and relocation incentives from 2020 through 2024. According to MARAD’s February 2023 recruitment and outreach plan, the agency will also increase the use of these types of flexibilities to attract candidates and intends to create a program manager position designed to promote these opportunities.

· Rewriting position descriptions. In some cases, when they were not initially able to hire a qualified candidate, MARAD officials said that they have rewritten position descriptions to make them less restrictive and widen the pool of potential applicants. For example, officials worked with DOT’s Executive and Political Resources Center to rewrite a position description for the Executive Director of the Committee on the U.S Marine Transportation System. The rewritten position increased the number of resumes they received by 16 percent and increased the number of qualified applicants by 35 percent, according to MARAD officials.

· Employee engagement efforts. Officials said that MARAD was also identifying opportunities to address employee turnover through increased consultation with employees on workplace climate and staff retention. MARAD’s overall employee engagement index results on the Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey decreased from 71 percent to 69 percent between fiscal years 2022 and 2023 and were lower than the government-wide results of 72 percent in fiscal year 2023. Index results for MARAD employees’ perceptions of leadership also decreased in fiscal year 2023, even as DOT’s agency-wide result in this category increased. Officials from the Office of Strategic Sealift said that their staff feels overworked, and that is reflected in the lower employee survey scores. MARAD officials told us that, in part as a response to these trends, they established an employee resource group. The goal of the employee resource group is to be a safe space for employees to discuss strategies and generate recommendations to leadership for improving employee experience and workplace culture, according to MARAD reports. Employee focus groups provided senior leadership with recommendations to increase transparency within the organization, improve communication within teams and with leadership, and establish consistent management styles.

MARAD Is Developing a Strategic Workforce Plan to Determine Future Staffing Needs

Strategic workforce planning is an Office of Personnel Management requirement[25] and integral to effective management of an agency, according to MARAD officials. In July 2024, MARAD selected a contractor to develop strategic workforce plans for both MARAD and the Academy, addressing recruitment, talent development, retention, employee engagement, diversity, and succession planning in both organizations. MARAD officials noted they have been working for close to 2 years on this effort. Agency officials told us they expect the contractor will complete the plan in September 2025, providing some initial findings related to the agency’s organizational needs beginning in spring of 2025. MARAD officials said that ideally, the workforce plan will identify specific activities that program offices are unable to carry out with current resources and will help MARAD understand and define its future staffing needs. MARAD officials said that due to capacity constraints in the agency’s two-person Human Resources office, they decided to contract out the plan’s development.

In August 2024, we recommended that MARAD conduct strategic workforce planning to determine the needed resources, capabilities, and any skill gaps in the Academy’s Office of Facilities and Infrastructure.[26] DOT agreed with our recommendation, and MARAD confirmed that the contractor they selected will develop a strategic workforce plan for both MARAD and the Academy.

While the MARAD contractor is developing the strategic workforce plan, MARAD officials said their current workforce planning efforts include measuring workforce metrics on a quarterly basis, as required by DOT’s Human Capital Operating Plan. For example, MARAD Human Resource officials currently track data from the Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey related to employee engagement, performance, and diversity. Officials said they have provided these data to the contractor to integrate into the forthcoming plan. Additionally, MARAD developed a new “manning document” in August 2024 that officials said they have started to use to track authorized positions, onboarded candidates, open vacancies, and active recruitments across the agency. MARAD officials said they hope to use this manning document as a management tool in the future to help with strategic workforce planning efforts.

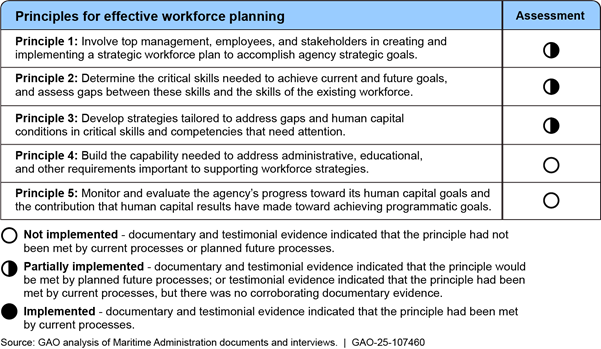

MARAD’s Current Workforce Planning Efforts Do Not Fully Implement Key Principles

MARAD has partially implemented three of the five key principles for effective strategic workforce planning in its strategic workforce plan and has not implemented two of the principles (see fig. 5). In each of these areas, MARAD officials told us that the strategic workforce plan is still under development as they are working toward the completion of the plan with the help of a contractor, as described above. While MARAD anticipates completing its plan in September 2025, we assessed the steps they have taken in developing its strategic workforce plan.

Figure 5: Assessment of the Maritime Administration’s (MARAD) Implementation of GAO’s Principles for Effective Strategic Workforce Planning

MARAD Has Partially Implemented Three Strategic Workforce Planning Principles into Its Workforce Plan

MARAD has partially implemented effective workforce planning principles related to (1) involving top management, employees, and stakeholders; (2) determining critical skills needed to achieve current and future goals; and (3) developing strategies tailored to address gaps.

Involve Top Management, Employees, and Stakeholders in the Creation of the Strategic Workforce Plan

As we have previously reported, involving top management in strategic human capital planning efforts can help provide stability as the workforce plan is being developed and implemented. It also provides a cadre of champions within the agency to ensure that planning strategies are thoroughly implemented and sustained over time.[27] Top leadership that is clearly and personally involved in strategic workforce planning also provides the organizational vision that is important in times of change. Integrating workforce planning efforts across the agency can be accomplished by ensuring that key leaders from every office are involved.

MARAD has taken certain steps to involve top management in its strategic workforce plan. MARAD officials emphasized that the development of the forthcoming plan has the attention of their top management. MARAD officials said that they will further involve top management through their Enterprise Governance Council—a group comprising select MARAD leaders that meets every 3 weeks to offer strategic direction for the agency, including human resource efforts. According to MARAD officials, MARAD has begun prioritizing workforce planning at weekly leadership meetings on their meeting agendas, and they intend to monitor the contractor’s progress as work on the plan begins. According to MARAD officials, MARAD’s Human Resource Director serves as the technical representative for the workforce planning contract, overseeing the development of the overall approach and project plan. The Human Resource Director receives direction from agency leadership and facilitates discussions between the contractor and the Enterprise Governance Counsel to help ensure that strategic direction is carried from the agency leadership team to the workforce planning efforts, according to MARAD officials.

In October 2024, MARAD’s Executive Governance Counsel also reviewed and approved a project plan for the forthcoming strategic workforce plan, which provides an overview and timeline of products and deliverables that the contractor will provide to complete the development of the strategic workforce plan. MARAD officials said that the contractor will help develop a communications plan to convey the results of the strategic workforce planning efforts with managers and employees across the agency as the workforce plan is nearing completion.

However, MARAD has not fully determined how other managers, employees, and stakeholders across the agency, such as the program office managers, will be involved in the development of the forthcoming strategic workforce plan and how they will contribute to it. MARAD officials explained that while they plan to brief all employees about the content of the forthcoming strategic workforce plan, they have not yet developed a means to include managers across the agency in the development of the overall plan.

We have reported that agency managers, supervisors, employees, and stakeholders need to work together to ensure that the entire agency understands the need for, and benefits of, changes to a strategic workforce plan so that the agency can develop clear and transparent policies and procedures to implement the plan’s human capital strategies.[28] MARAD officials said they plan to involve employees and other internal stakeholders in the development of the strategic workforce plan. Specifically, officials told us they intend to involve their newly established employee resource group, but they have not yet identified the specific role the group will have or the process for involving the group.

MARAD officials told us that because they are only in the initial stages of creating a new strategic workforce plan, aspects of their planned approach, such as the process by which managers and employees will be involved in the planning has not been fully developed. MARAD officials have told us that they provided an overview to their employees of their workforce planning efforts, but they have not yet made specific plans for how managers, employees, and other stakeholders will be involved in the development of the plan. Until MARAD ensures that their managers, employees, and stakeholders are involved in the development and implementation of the workforce plan, the agency is not well-positioned to ensure that the plan will be responsive to the agency’s most pressing workforce needs, such as those currently facing the program offices. Furthermore, without identifying how management, employees, and other stakeholders will be involved in the development of the forthcoming strategic workforce plan, MARAD faces the risk that the execution of the strategic workforce plan may not be in line with the vision of its key leadership.

Determine Critical Skills for Current and Future Goals and Assess Skill Gaps

MARAD has taken steps to determine current skills needed for its workforce but has not fully implemented a means to identify its current and future workforce needs. MARAD’s statement of work for the forthcoming strategic workforce plan notes that the contractor will conduct a workforce analysis that includes identifying workforce competencies and skills. MARAD officials told us that this will be an important aspect of the contractor’s workforce analysis, which will be an area of focus in the coming months. Also, a project overview developed by MARAD’s contractor said that it will conduct an in-depth analysis of current workforce demands and a forecast of the agency’s future state by February 2025, but did not offer details on how this analysis would be conducted and completed. Additionally, as mentioned previously, in August 2024 MARAD developed a “manning document” that depicts filled and vacant positions across the agency. This analysis could assist the contractor and MARAD in conducting a critical skills analysis as part of its overall strategic workforce plan, according to MARAD officials. However, MARAD officials told us they did not yet have plans to incorporate the manning document information into the workforce plan, as they were still determining how it will be used going forward.

While the manning document identifies some of MARAD’s current workforce needs, MARAD has not identified how it will assess future workforce needs. For instance, the statement of work does not detail how the contractor’s workforce action plan is to assess certain skillsets that MARAD will need in the future. As described above, officials in certain offices, such as the Office of Shipyards and Marine Engineering, identified the need for expertise in areas such as cybersecurity and artificial intelligence. However, MARAD has not developed an overarching means for the entire workforce to assess what future skills—such as cybersecurity, artificial intelligence, or other skillsets—may be needed for the agency as a whole. MARAD officials stated they have not fully assessed these workforce skills because their strategic workforce plan is still in development, though they have taken some initial steps through a training needs assessment they conducted at the beginning of fiscal year 2024, and they plan to work with the contractor to identify skill gaps in the future. However, without a process to identify and incorporate future skill needs such as these into its workforce planning efforts, the agency may be unable to identify and close potential skills gaps needed to ensure success for the future.

Develop Strategies to Address Gaps in Critical Skills

MARAD officials told us they are using an interim strategy to address skill gaps identified in the prior human capital plan, but the agency has not yet implemented a strategy to address skill gaps for its forthcoming strategic workforce plan. For instance, as an interim measure, MARAD officials told us they address their current workforce needs by following DOT’s Human Capital Operating Plan. According to the MARAD officials, they use the Human Capital Operating Plan to track certain human resource statistics (such as attrition rate, turnover of employees with 1 to 3 years of service, retirement, and new hires) on a quarterly basis and produce a report. MARAD officials said they use these quarterly reports, including the workforce analysis, to evaluate their progress in addressing current workload demands. According to MARAD officials, several workforce initiatives, including the recruitment and outreach plan, employee focus groups, and the employee resource group, also came out of this effort. DOT officials also told us that they have begun a department-wide effort to update the DOT Workforce Plan for fiscal year 2026-2029, which will include identifying an approach to identify and close skill gaps specifically related to automated technologies.

While these efforts have helped MARAD monitor its current workforce, they do not constitute an overarching strategy for how the agency will close existing skill gaps, and they are not linked to an overall strategic workforce plan specific to MARAD. MARAD’s statement of work states that the contractor’s workforce action plan is to include strategies to close identified skill gaps. However, the statement of work does not provide any detail on how this workforce action plan is to identify such strategies, and MARAD officials were unable to provide us with other examples of an overarching plan to address skill gaps. As a result, MARAD could be vulnerable to leaving certain gaps open in its workforce. For instance, MARAD’s turnover rate from the past 10 years, coupled with a retirement eligibility rate that is expected to grow to 43 percent by 2029, will make it difficult for the agency to maintain a balanced workforce capable of meeting its numerous missions. Without the benefit of an overarching strategy to close skill gaps that is linked to a strategic workforce plan, MARAD risks having a workforce that is not best positioned to address future challenges.

MARAD Has Not Implemented Two Strategic Workforce Planning Principles into Its Workforce Plan

MARAD has not yet implemented effective workforce planning principles related to (1) building the capability needed to address workforce strategies and (2) monitoring and evaluating progress.

Build the Capability Needed to Support Workforce Strategies

MARAD has not determined how it will build the capabilities necessary to support workforce strategies identified within the agency’s forthcoming strategic workforce plan. MARAD’s statement of work briefly mentions building capability, stating that MARAD has identified the need to strategically assess its workforce capabilities and capacity to achieve its mission. However, the statement of work does not detail how the contractor’s workforce action plan is to address building capabilities to support workforce strategies, and MARAD officials were not able to provide specific information for how they would develop these capabilities.

As we have previously reported, as agencies develop tailored workforce plans and address administrative, educational, and other requirements that are important to support them, it is especially important to recognize practices that are key to the effective use of human capital authorities, such as hiring flexibilities.[29] This can involve, for instance, training managers and employees on the use of hiring flexibilities and streamlining any administrative processes necessary to use those flexibilities. MARAD officials have been using some hiring flexibilities to fill existing vacancies, such as expanding the use of direct hire authorities and certain pay incentives, as previously mentioned. They also mentioned that they plan to include hiring flexibilities in the talent acquisition portion of their strategic workforce plan, but they have not yet detailed how or what types of efforts, such as those identified in the recruiting and outreach plan, will be incorporated into the forthcoming plan.

Current staffing constraints may make it challenging to implement administrative and other requirements to support the strategies identified in the forthcoming strategic workforce plan. Our prior work also indicates that agencies should build the capability needed to address administrative, education, and other requirements important to supporting the workforce strategy.[30] As mentioned previously, MARAD’s human resource office did not have the capability to develop the strategic workforce plan internally and needed the assistance of a contractor, according to MARAD officials. MARAD officials also told us that the limited number of employees within the agency makes it difficult for them to complete the hiring process. Because there are only two staff in MARAD’s Human Capital office, to include the Human Resources Director, it will be all the more important that MARAD identifies any administrative processes or trainings necessary to carry out strategies once the contractors have completed their work. When developing tailored workforce plans, it is important for the agency to build the necessary capability within their human resource offices so that the agency can effectively follow through and implement their strategy. According to GAO’s analysis of interview statements and MARAD documents, the agency is in the early stages of developing the plan and has not yet developed capabilities to support a new plan. Developing a means to support the implementation of its workforce strategies would better position MARAD to address its existing workforce challenges, particularly the high vacancies, turnover rates, and staffing shortages that the agency currently faces.

Monitor and Evaluate the Agency’s Progress toward Its Human Capital Goals

MARAD has not yet identified a process to monitor and evaluate the agency’s progress toward the goals set out in its forthcoming strategic workforce plan. The statement of work mentions the need to develop measures for assessing progress upon the plan’s completion. However, MARAD could not describe specifically what these measures might be or how they would assess the agency’s progress once the workforce plan is completed. Officials explained that it was too early in the process to develop such measures because the contractor had not yet completed the plan and strategies. As we have reported, developing performance measures, and discussing how the agency will use these measures to evaluate the strategies before it starts to implement the workforce plan, can help the agency. In addition, high-performing organizations recognize the fundamental importance of measuring both the outcomes of human capital strategies and how these outcomes have helped the organizations accomplish their missions and programmatic goals.[31] The measures should be quantifiable.

While MARAD had a strategic workforce plan covering fiscal years 2017 through 2022, which mentioned measuring and assessing progress, officials told us that they did not track or monitor the agency’s progress toward the goals identified in the plan. This plan identified four human capital goals: (1) Improve talent acquisition, (2) Renew emphasis on talent development, (3) Build leadership capacity, and (4) Strengthen employee engagement. However, these goals did not include measures that were actionable and quantifiable. The officials also noted that after they completed the prior plan, there was a change in administration, followed by a hiring freeze. Furthermore, MARAD officials told us that the agency did not have a Human Resources Director at the time to help lead them through the stated goals, and so they were not able to follow through on all the actions identified in the plan and did not evaluate progress toward achieving the goals.

Developing a process to monitor and evaluate progress toward strategic human capital goals would serve as an accountability process to help ensure that MARAD progresses toward the goals ultimately identified in the forthcoming strategic workforce plan. Doing so also positions MARAD to identify when actions are not working toward their intended goals, so the agency can change course as needed. According to MARAD officials, because the agency’s work has changed drastically since MARAD last had a workforce plan, and the agency is supporting programs of increasing complexity, it is all the more important for MARAD to develop a means to track its human capital performance. MARAD officials agreed that doing so would help them achieve the agency’s mission and overarching strategic goals.

Conclusions

MARAD is facing multiple simultaneous workforce challenges, including staff turnover, high retirement eligibility rates, and vacancies in critical positions. As these challenges compound, it may become increasingly difficult for MARAD staff to meet mission requirements. To effectively meet the agency’s numerous programmatic responsibilities, MARAD needs a strategic workforce plan that addresses the challenges posed by existing staffing shortages and builds capacity to prepare the agency for future needs.

MARAD has begun to take a strategic approach to improving the state of its workforce. This approach includes taking some actions and using an interim strategy to address current staff needs, while a contractor begins work to develop a strategic workforce plan. Fully developing, implementing, and executing a strategic workforce plan that includes the five key workforce planning principles will be important for the agency. In the past, MARAD struggled to fully implement its prior strategic workforce plan and to monitor and evaluate its stated goals. By fully implementing strategic workforce principles that ensure management, employee, and stakeholder involvement; determine and address skill gaps; and monitor progress toward achieving its goals can better position MARAD’s workforce for the future. MARAD’s current efforts to develop a strategic workforce plan serve as an opportunity to implement key principles into its strategic workforce planning.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following four recommendations to the Maritime Administration:

The Administrator of the Maritime Administration should ensure that managers, employees, and stakeholders are involved in developing the forthcoming strategic workforce plan, by identifying the means and frequency for involving them in the plan’s development. (Recommendation 1)

The Administrator of the Maritime Administration should assess critical skills needed to achieve MARAD’s future goals and develop a strategy to address any future skill gaps identified within the forthcoming strategic workforce plan. (Recommendation 2)

The Administrator of the Maritime Administration should build the capability needed to support workforce strategies, such as by determining how MARAD will incorporate hiring flexibilities or streamline any administrative processes needed to implement the forthcoming strategic workforce plan. (Recommendation 3)

The Administrator of the Maritime Administration should develop a process to monitor and evaluate progress toward any goals ultimately identified in the forthcoming strategic workforce plan, to include creating a set of quantifiable measures of effectiveness that will help gauge progress in implementing the agency’s forthcoming strategic workforce plan. (Recommendation 4)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to DOT for review and comment. In its comments, reproduced in appendix II, DOT agreed with our recommendations and stated they will be addressed. DOT also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Transportation, the Administrator of MARAD, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at (202) 512-2834 or vonaha@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix III.

Andrew Von Ah

Director, Physical Infrastructure Issues

Table 1: Selected Examples of Maritime Administration (MARAD) Identified Statutory Responsibilities Across the Maritime Administration’s Mission Areas

|

Statutory mission |

Lead MARAD office |

Statutory citation |

|

War Risk Insurance |

Business and Finance Development |

46 U.S.C. 53901 et seq. |

|

Federal Ship Financing Program (Title XI) |

Business and Finance Development |

46 U.S.C. 53701 et seq. |

|

Capital Construction Fund/Construction Reserve Fund |

Business and Finance Development |

46 U.S.C. 53501 et seq. (Capital Construction Fund); 46 U.S.C. 53301 et seq. (Construction Reserve Fund) |

|

Studies on maritime-related Issues |

Environment and Compliance, Office of Policy and Plans |

46 U.S.C. 50102, 50103, 50104, 50105, 50106, 50107, 50108, 50109, 50302 |

|

Maritime Environmental and Technical Assistance Program (META) |

Environment and Compliance |

46 U.S.C. 50307 |

|

Small Shipyard Grant Program |

Environment and Compliance |

46 U.S.C. 54101 |

|

Ballast Water & Invasive Species Research |

Environment and Compliance |

46 U.S.C. 50307 (some of these issues addressed through META projects) |

|

U.S. Marine Highways Program |

Ports & Waterways |

46 U.S.C. 55601 et seq. |

|

Gateway Offices—Industry/Regional Engagement |

Ports & Waterways |

49 U.S.C. 109(e) |

|

Deepwater Port Program |

Ports & Waterways |

33 U.S.C. 1301 et seq.; 49 C.F.R. 1.93(h) (delegated functions of Maritime Administration) |

|

Port Conveyance Program |

Ports & Waterways |

40 U.S.C. 554; 49 C.F.R. 1.93(g) |

|

Maritime Transportation System National Advisory Committee |

Ports & Waterways |

46 U.S.C. 50402 |

|

Port Infrastructure Development Program |

Ports & Waterways |

46 U.S.C. 54301 |

|

American Fisheries Act |

Office of Chief Counsel |

46 U.S.C. 12113 |

|

Centers of Excellence |

Strategic Sealift |

46 U.S.C. 51706 |

|

Training Ship Operations |

Strategic Sealift |

46 U.S.C. 51501 et seq. with particular reference to 46 U.S.C. 51504 and 51506 |

|

NSS Savannah Decommission |

Strategic Sealift |

42 U.S.C. 2131 et seq. (Atomic Energy Licenses with special reference to 42 U.S.C. 2134(d)); 16 U.S.C. 470 et seq. (National Historic Preservation Act with special reference to 46 U.S.C. 470f); 46 U.S.C. 57102; 46 U.S.C. 57103; 54 U.S.C. 308704. P.L. Law 848, 70 Stat. 731 (July 30, 1956).; 10 C.F.R. Part 50 |

|

Workforce Development- -Training Standards |

Strategic Sealift |

46 U.S.C. 51103; 46 U.S.C. 51104; 46 U.S.C. 51301 et seq. 46 U.S.C. 51506; 46 U.S.C. 51507; 46 U.S.C. 51701; 46 U.S. C. 51702; 46 U.S.C. 51703; 46 U.S.C. 51704; 46 U.S.C. 51705; 46 U.S.C. 51706; 46 U.S.C. 51707 |

|

Every Mariner Builds A Respectful Culture (EMBARC) |

Strategic Sealift |

46 U.S.C. 51318; 46 U.S.C. 51322; 46 U.S.C. 51325;

46 U.S.C. 51501; 46 U.S.C. 51506. See 46 U.S.C. 51322 note citing Pub. L.

No. 117-263, Title XXXV, 3513(b), 136 Stat. 2395 (2022) as authorizing

regulations by Maritime Administrator dealing with EMBARC. See |

|

Voluntary Intermodal Sealift Agreement (VISA) Program |

Strategic Sealift |

Defense Production Act, as amended, as related to MARAD, 50 U.S.C. 4558 and the Maritime Security Act of 2003 as related to MARAD, 46 U.S.C. 53101 et seq. (with particular reference to 53107) |

|

Voluntary Tanker Agreement (VTA) Program |

Strategic Sealift |

Defense Production Act, as amended, as related to MARAD, 50 U.S.C. 4558; 46 U.S.C. 53401 et seq. (with particular reference to 53407) |

|

National Security Multi-Mission Vessels (NSMV) |

Strategic Sealift |

46 U.S.C. 51501 et seq.; Pub. L. No. 114-328, 3501(3), 3505, 130 Stat. 2000 (2016) (National Defense Authorization Act, 2017); Pub. L. No. 114-113, 129 Stat. 2242, 2860 (2016) (Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016); Pub. L. No. 115-31, 131 Stat. 135, 750 (2017) (Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017); Pub. L. No. 115-141, 132 Stat. 348, 999-1000 (2018) (Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018); Pub. L. No. 116-6, 133 Stat. 13, 424 ( (2019) (Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2019); Pub. L. No. 116-94, 133 Stat. 2534, 2965 (2019) (Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020); Pub. L. No. 116-260, 134 Stat. 1182, 1858 (2020) (Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021) |

|

Ship Disposal Program |

Strategic Sealift |

40 U.S.C. 548, 46 U.S.C. 57102, 46 U.S.C. 57103, 46 U.S.C. 57104; 54 U.S.C. 308704; 46 U.S.C. 51103(b); Pub. L. No. 107-314, 3504, 116 Stat. 2458 (2002); Pub. L. No. 110-419 3502, 122 Stat. 4773 (2008) (Export scrapping limitation) |

|

Maritime Security Program |

Strategic Sealift |

46 U.S.C. 53101 et seq. |

|

Tanker Security Program |

Strategic Sealift |

46 U.S.C. 53401 et seq. |

|

Cable Security Fleet Program |

Strategic Sealift |

46 U.S.C. 53201 et seq. |

|

Cargo Preference |

Strategic Sealift |

46 U.S.C. 50110; 46 U.S.C. 55305; 46 U.S.C. 55304; 10 U.S.C. 2631 |

|

Foreign Transfers of U.S. Vessels |

Strategic Sealift |

46 U.S.C. 56101 et seq. |

|

National Defense Reserve Fleet |

Strategic Sealift |

46 U.S.C. 57100 et seq. |

|

State Maritime Academy Support Program |

Strategic Sealift |

46 U.S.C. 51501 et seq. |

|

U.S. Merchant Marine Academy |

U.S. Merchant Marine Academy |

46 U.S.C. 51301 |

|

U.S. Merchant Marine Academy Board of Visitors |

U.S. Merchant Marine Academy |

46 U.S.C. 51312 |

|

U.S. Merchant Marine Academy Advisory Board |

U.S. Merchant Marine Academy |

46 U.S.C. 51313 |

|

U.S. Merchant Marine Academy Advisory Council |

U.S. Merchant Marine Academy |

46 U.S.C. 51323 |

|

U.S. Merchant Marine Academy Student Advisory Board |

U.S. Merchant Marine Academy |

46 U.S.C. 51326 |

|

U.S. Merchant Marine Academy Sexual Assault Advisory Council |

U.S. Merchant Marine Academy |

46 U.S.C. 51327 |

Source: Maritime Administration. │ GAO‑25‑107460

GAO Contact

Andrew Von Ah, (202) 512-2834 or vonaha@gao.gov.

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Maria Wallace (Assistant Director), Patrick Tierney (Analyst in Charge), Padma Chirumamilla, Geoffrey Hamilton, Steven Lozano, Amelia Weathers, Malika Williams, and Elizabeth Wood made key contributions to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on Facebook, Flickr, X, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our RSS Feeds or Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7700

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, ClowersA@gao.gov, (202) 512-4400, U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7125, Washington, DC 20548

Public Affairs

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, KaczmarekS@gao.gov, (202) 512-4800, U.S.

Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7149

Washington, DC 20548

Strategic Planning and External Liaison

Stephen J. Sanford, Managing

Director, spel@gao.gov, (202) 512-4707

U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7814, Washington,

DC 20548

[1]MARAD had approximately 800 employees as of November 2024.

[2]See GAO, Maritime Security: DOT Needs to Expeditiously Finalize the Required National Maritime Strategy for Sustaining U.S.-Flag Fleet, GAO‑18‑478 (Washington, D.C.: Aug. 8, 2018); Maritime Administration: Actions Needed to Enhance Cargo Preference Oversight, GAO‑22‑105160 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 12, 2022); and U.S. Merchant Marine Academy: Actions Needed to Sustain Progress on Facility and Infrastructure Improvements, GAO‑24‑106875 (Washington, D.C.: Aug. 6, 2024).

[3]GAO, High-Risk Series: Efforts Made to Achieve Progress Need to Be Maintained and Expanded to Fully Address All Areas, GAO‑23‑106203 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 20, 2023).

[4]GAO, Human Capital: Key Principles for Effective Strategic Workforce Planning, GAO‑04‑39 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 11, 2003).

[6]U.S. Office of Personnel Management, Workforce Planning Guide (Washington, D.C.: November 2022).

[7]GAO, High-Risk Series: Efforts Made to Achieve Progress Need to Be Maintained and Expanded to Fully Address All Areas, GAO‑23‑106203 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 20, 2023).

[8]GAO, Internal Revenue Service: Strategic Human Capital Management Is Needed to Address Serious Risks to IRS’s Mission, GAO‑19‑176 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 26, 2019).

[11]According to MARAD, the bulk of statutory authorities for which MARAD is responsible are delegated to the Maritime Administrator, the head of MARAD, by the Secretary of Transportation in 49 C.F.R. §§ 1.81 and 1.93. See App. I for examples of MARAD’s statutory responsibilities.

[12]The Office of Strategic Sealift administers the Maritime Security Program and the Tanker Security Program, among others. The Maritime Security Program aims to maintain a fleet of commercially viable, militarily useful merchant ships active in international trade. The Tanker Security Program aims to ensure that a core fleet of U.S.-based product tankers can operate competitively in international trade and enhance U.S. supply chain resiliency for liquid fuel products.

[13]Federal “cargo preference” laws, regulations, and policies require that when cargo owned or financed by the federal government is transported on an ocean vessel, certain percentages of that cargo must be carried on United States-flag vessels.

[14]Pub. L. No. 117-58, 135 Stat. 429 (2021).

[15]The National Environmental Policy Act of 1969, as amended, and implementing regulations issued by the Council on Environmental Quality require federal agencies, including MARAD, to evaluate certain proposed federal actions significantly affecting the quality of the environment, including adverse environmental effects. 42 U.S.C. § 4332; 40 C.F.R. Parts 1500-1508. See also 42 U.S.C. §§ 4336, 4336a.

[16]Pub. L. No. 117-58, div. J, tit. VIII, 135 Stat. 429, 1442 (2021).

[17]William M. (Mac) Thornberry National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2021, Pub. L. No. 116-283, § 3511, 134 Stat. 3388, 4408 (2021) (Tanker Security Program), and National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020, Pub. L. No. 116-92, § 3521, 133 Stat. 1198, 1988 (2019) (Cable Security Fleet Program).

[18]National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2017, Pub. L. No. 114-328, § 3505, 130 Stat. 2000, 2776 (2016).

[19]MARAD’s Office of Strategic Sealift was allotted additional full-time positions as augments to its staff because of funding received from DOD for positions related to DOD work. Vacancies are funded positions that have not yet been filled. In its calculation of the vacancy rate, MARAD did not include positions authorized under the IIJA, so they are not included here. If positions authorized under the IIJA are included in the calculation, MARAD had 974 authorized positions in September 2024, and 149 vacancies, a 15.3 percent vacancy rate.

[20]For plain language purposes, MARAD’s Associate Administrations and Offices will be referred to as “offices” or “program offices” throughout this report.

[21]GAO‑24‑106875. In August 2024, we recommended that MARAD take steps to ensure the Academy maintains continuous leadership in the Office of Facilities and Infrastructure and that such steps should include establishing a dedicated leadership and implementation team and succession planning for leadership positions in the office. DOT agreed with our recommendation but has not yet taken action to address it.

[22]The Department of Transportation defines turnover rate as the rate at which employees leave the organization divided by the average number of employees at a given period. According to MARAD, the turnover rate includes voluntary separations, such as employees who retire, resign, transfer, or accept military orders.

[23]MARAD had 128 active recruitments as of September 2024. MARAD does not include positions authorized under the IIJA in calculating the agency’s vacancy rate. Including positions authorized under the IIJA, MARAD has 149 vacancies. Excluding positions authorized under the IIJA, MARAD has 116 vacancies.

[24]Direct hire authority provided to an agency by the Office of Personnel Management is designed to enable an agency to make hires using an expedited process by, among other things, eliminating specified competitive rating and ranking requirements. See 5 U.S.C. § 3304(a)(3), 5 C.F.R. §§ 337.201-206.

[25]Title 5 of the Code of Federal Regulations Part 250, Personnel Management in Agencies, subpart B, Strategic Human Capital Management, sets out strategic human capital management requirements. Under these regulations, executive branch agencies are responsible for planning, implementing, evaluating, and improving human capital policies and programs that are based on comprehensive workforce planning and analysis.

[26]GAO, U.S. Merchant Marine Academy: Actions Needed to Sustain Progress on Facility and Infrastructure Improvements, GAO‑24‑106875 (Washington, D.C.: Aug. 6, 2024).