COMPARATIVE EFFECTIVENESS RESEARCH

HHS Should Evaluate Its Performance of Related Activities

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Leslie V. Gordon at GordonLV@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107462, a report to congressional committees

COMPARATIVE EFFECTIVENESS RESEARCH

HHS Should Evaluate Its Performance of Related Activities

Why GAO Did This Study

Federal law includes provisions for GAO to regularly review PCORI and HHS comparative clinical effectiveness research activities. PCORI, a federally funded nonprofit corporation, makes awards for research studies that focus on health issues facing people in the U.S., such as mental and behavioral health, cardiovascular disease, and cancer. Disseminating findings from this research can provide important information on effective treatments to improve health care decision-making for stakeholders, such as providers and patients. Also, implementing these findings into clinical practice may further result in improved health outcomes.

This report describes HHS efforts to disseminate and help implement PCORI-funded research findings and examines the extent to which PCORI and HHS have used key performance management practices to assess their respective efforts, among other issues.

GAO reviewed PCORI and HHS documentation and data for fiscal years 2019 through 2024. GAO also interviewed PCORI representatives, HHS officials, and representatives from a nongeneralizable sample of nine stakeholder groups, such as provider and patient organizations.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making one recommendation to HHS to complete a planned evaluation of its dissemination and implementation portfolio that includes establishing near-term goals and performance measures. HHS neither agreed nor disagreed with the recommendation. GAO maintains the recommendation is valid.

What GAO Found

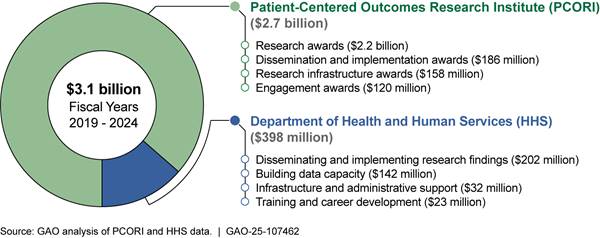

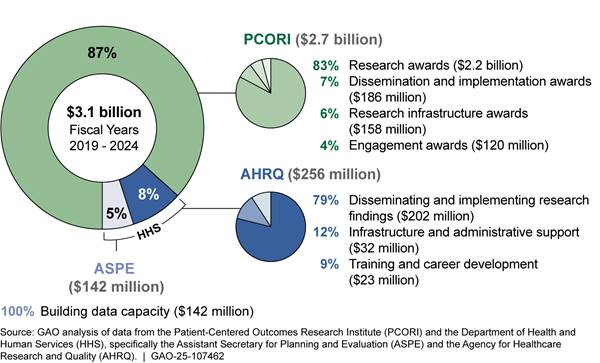

Comparative clinical effectiveness research evaluates and compares the health outcomes of two or more medical treatments, services, or items. In 2010, Congress authorized the establishment of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) to conduct this research and improve its quality and relevance, and directed the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to publicly disseminate and help incorporate these research findings into clinical practice. PCORI and HHS obligated a total of $3.1 billion for fiscal years 2019 through 2024.

PCORI Award Obligations and HHS Obligations for Comparative Clinical Effectiveness Research Activities, Fiscal Years 2019 Through 2024

Note: PCORI’s award obligations and HHS’s obligations may be expended in years subsequent to the year they were made. PCORI’s award obligations do not include funds used by PCORI for its operations.

From 2016 to March 2025, HHS disseminated findings from 16 PCORI-funded studies through a newsletter and social media, among other methods, according to officials. HHS also helped to implement the findings of one PCORI-funded study through one of its dissemination and implementation programs.

GAO found that PCORI uses key performance management practices—identifying long- and near-term goals and associated performance measures—to assess the performance of its dissemination and implementation efforts.

Similarly, HHS does this for its three largest dissemination and implementation programs. In 2020, GAO reported HHS had plans to evaluate its dissemination and implementation portfolio and, according to officials, this evaluation would develop near-term goals and performance measures. However, it is unclear whether the evaluation will be conducted as planned. HHS has not yet requested proposals for the evaluation, and officials attributed recent delays to leadership changes in August 2024 and March 2025. Further, in March 2025, HHS announced staff reductions and a departmental reorganization, which had not been implemented as of April 2025. Establishing near-term goals and performance measures as part of the planned evaluation will help enable HHS to regularly assess performance and determine whether the dissemination and implementation portfolio efforts as a whole are achieving the intended aim of promoting evidence-based, patient-centered care to improve health outcomes.

Abbreviations

|

AHRQ |

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality |

|

ASPE |

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation |

|

CDC |

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

|

HHS |

Department of Health and Human Services |

|

NIH |

National Institutes of Health |

|

PCORI |

Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute |

|

Trust Fund |

Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Trust Fund |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

July 14, 2025

Congressional Committees

Comparative clinical effectiveness research evaluates and compares the health outcomes and clinical effectiveness, risks, or benefits of two or more existing medical treatments, services, or items. Findings from this research can provide important information on more effective treatments for stakeholders involved in health care delivery and management, such as clinicians, patients, organizations that pay for health care services (known as payers), and policymakers.[1] Disseminating actionable research findings widely is critical for increasing the clinical knowledge base and improving health care decision-making. Furthermore, targeted and effective dissemination and implementation of research findings can further expand the practice of evidence-based treatments in health care delivery settings, potentially resulting in improved health outcomes. For example, one comparative clinical effectiveness research study compared two treatments—aspirin and heparin, a commonly used injectable blood thinner—for preventing clotting after a fracture.[2] The study found that patients who were prescribed aspirin were more likely to adhere to their medication and had similar health outcomes as those who were prescribed heparin.[3]

In 2010, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act authorized the establishment of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) as a federally funded, nonprofit corporation to conduct comparative clinical effectiveness research, improve its quality and relevance, and make such research findings publicly available.[4] In addition, the Act charged the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), with broadly disseminating and promoting the incorporation of findings from federally funded comparative clinical effectiveness research into clinical practices, including findings resulting from research funded by PCORI.[5]

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020 include provisions for us to report on PCORI’s and HHS’s activities every 5 years.[6] In addition, the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020 added a requirement that we report on any challenges PCORI-funded researchers have encountered in conducting studies.[7] In this report, we

1. describe challenges in conducting PCORI-funded studies;

2. describe PCORI and AHRQ efforts to publicly disseminate and help implement findings from PCORI-funded research; and

3. examine the extent to which PCORI and AHRQ have used key performance management practices to assess their comparative clinical effectiveness research dissemination and implementation efforts.

To describe challenges in conducting PCORI-funded studies, we reviewed progress reports and final research reports of six PCORI-funded studies.[8] In addition, we performed a literature review of selected articles describing researchers’ challenges conducting PCORI-funded studies.[9] We also reviewed relevant PCORI documentation, such as guidance for conducting studies and engaging research partners, and obtained written responses from PCORI. In addition, we interviewed the researchers of five of the six selected studies about researcher experiences, including their interactions with PCORI.[10] We also interviewed and obtained written responses from PCORI representatives, including how they monitor funded studies and support researchers. We also interviewed representatives from nine selected national stakeholder groups that have interacted with PCORI to obtain their perspectives about working with PCORI and using its funded research.[11] For the purposes of this report, we will refer to these representatives as “stakeholders.” The information we obtained regarding these selected studies and from stakeholders is not generalizable to other PCORI-funded studies or stakeholder groups.

To describe PCORI and AHRQ efforts to disseminate and help implement PCORI-funded research findings, we reviewed relevant documentation such as dissemination and implementation plans from our selected studies, PCORI funding award announcements, and AHRQ guidelines for disseminating information. We also interviewed and obtained written responses from PCORI representatives and AHRQ officials. Finally, we interviewed researchers and stakeholders, as mentioned previously, to obtain information about their perspectives on PCORI’s dissemination efforts, including any suggestions for PCORI to improve dissemination of PCORI-funded studies.

To examine the extent to which PCORI and AHRQ have used key performance management practices to assess their dissemination and implementation activities, we reviewed documents from PCORI and AHRQ, including any data related to their performance measures and other evaluations of these activities.[12] We also interviewed PCORI representatives and AHRQ officials to obtain information about how they assess performance of their dissemination and implementation activities. We evaluated PCORI’s and AHRQ’s efforts to assess the performance of their dissemination and implementation activities using key performance management practices identified in our prior work.[13] These practices include establishing goals that communicate the results that an organization or agency seeks to achieve, establishing performance measures, and regularly assessing progress toward goals.

Specifically, we reviewed PCORI performance data from fiscal year 2020 through fiscal year 2024, the most recently available data at the time of our review. We also reviewed data from PCORI about the number of studies funded to date. We assessed the reliability of these data in several ways, including reviewing related documentation and corroborating the data with publicly available information. We determined that the data are sufficiently reliable for the purposes of reporting on PCORI’s performance management practices. For AHRQ, we focused our review on its dissemination and implementation portfolio, including the three dissemination and implementation programs that accounted for 80 percent of AHRQ funding from fiscal years 2019 through 2024 (Clinical Decision Support, EvidenceNOW, and Evidence-based Practice Centers).

We conducted this performance audit from March 2024 to July 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Trust Fund

To fund PCORI’s and HHS’s comparative clinical effectiveness research activities through fiscal year 2019, the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act established the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Trust Fund. The Trust Fund provides funding to PCORI and two entities within HHS—AHRQ and the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE)—for comparative clinical effectiveness research activities.[14] In December 2019, the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020 made appropriations to the Trust Fund for PCORI and HHS to continue their comparative clinical effectiveness research activities from fiscal year 2020 through fiscal year 2029.[15]

PCORI’s award obligations are the total amount of funding PCORI intends to award or has awarded to be paid over multiple years. For example, funds for a research study awarded in fiscal year 2019 could be expended over the next 5 years. From fiscal year 2019 through 2024, PCORI and HHS agencies (AHRQ and ASPE) obligated a total of $3.1 billion. (See fig. 1.)

Figure 1: PCORI Award Obligations and HHS Obligations from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Trust Fund, Fiscal Years 2019 Through 2024

Note: The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act established the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Trust Fund to fund comparative clinical effectiveness research activities. PCORI’s award obligations and HHS’s obligations may be expended in years subsequent to the year they were made. PCORI’s award obligations do not include funds used by PCORI for its operations.

PCORI

PCORI, a federally funded, nonprofit corporation established in 2010, aims to fund comparative clinical effectiveness studies that provide patients, clinicians, purchasers, policy makers, and the public with information to make informed decisions about their health care. PCORI awards research funding to research organizations, such as universities or hospitals, for studies focusing on health issues facing people in the U.S. The studies address topics such as mental and behavioral health, cardiovascular disease, multiple chronic conditions, and cancer. (See table 1.) As of December 2024, PCORI had awarded funding for 950 studies. Researchers had completed 584 of the studies, and 366 studies were underway.

Table 1: Health Conditions That Received the Most PCORI Funding and Number of Research Awards, from 2012 to December 2024

|

Health condition |

Total amount of

research awards |

Number and description of research awards |

|

Mental & behavioral health |

1,270 |

271 studies on depression, substance abuse, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, anxiety disorders, autism, and related topics. |

|

Cardiovascular disease |

1,006 |

192 studies on congestive heart failure, hypertension, strokes, and other cardiovascular conditions. |

|

Multiple chronic conditions |

829 |

163 studies on patients with two or more chronic conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, obesity, or depression, and other chronic conditions. |

|

Nutritional and metabolic disorders |

616 |

141 studies on diabetes, obesity, dental issues, and other metabolic disorders. |

|

Cancer |

571 |

148 studies on prevention or treatments for breast, colorectal, lung, prostate, cervical, blood, and other cancers. |

Source: GAO analysis of information from the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). | GAO‑25‑107462

Note: PCORI uses inclusive health condition award categories, with some studies counted in more than one category, so adding the number of awards in each category will exceed the total number of awards and total funds obligated.

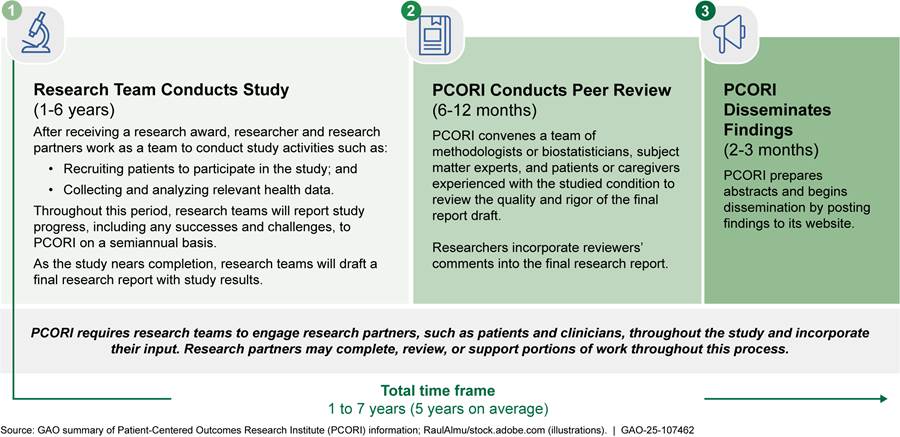

PCORI-funded studies can take anywhere from 1 to 7 years, with an average of 5 years, to be completed, peer-reviewed, and disseminated, according to PCORI representatives. (See fig. 2.)

The length of time to complete a PCORI-funded study can vary due to different factors, such as the selected study design or challenges encountered during the course of the study. For example, with randomized controlled trials and observational studies, researchers may partner with clinicians to recruit patient study participants and collect data needed to develop study findings. In contrast, for a systematic review, researchers synthesize existing studies and have little to no interaction with clinicians or patient study participants. Researchers may also encounter unexpected challenges during their work that affect their ability to progress as planned. For example, studies during the COVID-19 pandemic may have experienced delayed time frames, depending on how the pandemic affected their studies, according to PCORI representatives.

PCORI monitors the progress of their funded studies through program officers and requires researchers to submit semiannual progress reports to document accomplishments, challenges, and the status of study milestones, among other topics. Program officers provide support to researchers, such as answering researchers’ questions and ensuring researchers comply with requirements and milestones outlined in study contracts.

AHRQ and ASPE

With Trust Fund appropriations, prior to March 2025, AHRQ and ASPE carried out the following activities:

· AHRQ disseminated and supported the implementation of findings from comparative clinical effectiveness research funded by PCORI and other federal entities. Implementation included incorporating “actionable knowledge” derived from research findings into clinical practice using various tools and strategies, such as through health information technology tools to support clinicians in making health care decisions at the point of care. The agency also fostered capacity for conducting comparative clinical effectiveness research by supporting training for researchers in the methods used to conduct such research.

· ASPE worked to build data capacity for comparative clinical effectiveness research by improving the collection, linkage, and analysis of federal health data. See appendix II for ASPE projects and reports related to its data building capacity efforts from 2021 through 2023.

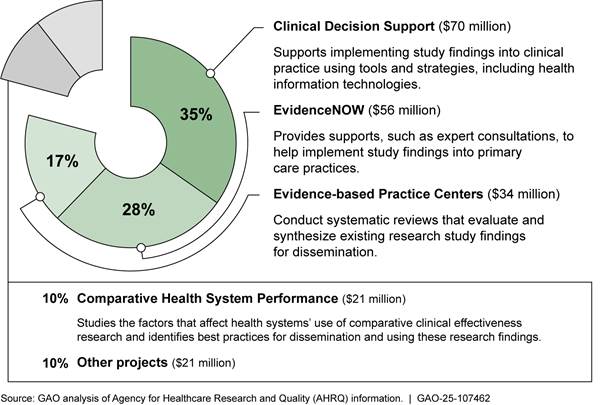

AHRQ’s dissemination and implementation portfolio was made up of four dissemination and implementation programs and about 10 other individual projects.[16] Among these programs, EvidenceNOW provided specially trained individuals to help primary care practices implement evidence-based practices into health care delivery, among other services and tools. For example, AHRQ provided tools such as a process workflow to help medical assistants implement findings from comparative clinical effectiveness research on aspirin use for patients with heart disease. This program also helped to implement these practices by providing health information technology support to using electronic health records. From fiscal year 2019 through 2024, AHRQ obligated $181 million for its dissemination and implementation programs. Figure 3 shows descriptions of these programs and funding for these programs and other projects.

Figure 3: AHRQ’s Dissemination and Implementation Portfolio Obligations from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Trust Fund, Fiscal Years 2019 Through 2024

Note: “Other projects” include activities such as commissioning a study to determine how to maintain previously available summaries of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines; providing training to hospitals to promote implementation of strategies, like automatic referrals, to increase participation in cardiac rehabilitation for eligible patients; and disseminating and implementing a playbook for assisting clinicians in offering medication for opioid use disorder in primary care settings.

In September 2024, AHRQ announced a funding opportunity for up to $375 million over 5 years for a new dissemination and implementation program, Healthcare Extension Service. The Healthcare Extension Service aimed to speed up the implementation of comparative clinical effectiveness research findings into clinical practice by awarding grants to state-based cooperatives. AHRQ intended for these cooperatives to work with state Medicaid agencies, managed care organizations, and others to identify and address barriers to implementing comparative clinical effectiveness research into health care delivery and support clinicians and patients in making more informed decisions about care options. AHRQ officials said this new program was informed by and intended to build upon AHRQ’s EvidenceNOW program.[17]

Selected Researchers and Studies Identified Certain Challenges, Which PCORI Is Addressing

Engaging research partners and recruiting and retaining a

sufficient number of patients were frequently cited as challenges during the

course of PCORI-funded studies, according to the literature we reviewed and

researchers from our six selected studies. Researchers and stakeholders we

interviewed also identified the completion of PCORI’s reporting requirements as

both a challenge and a benefit during their studies. For their part, PCORI

representatives described efforts to address these challenges.

Challenges Engaging with Research Partners

|

The Role of Research Partners The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) requires funded researchers to engage research partners throughout studies to improve the relevancy and use of study findings. Research partners could include patients, clinicians, community members, health care purchasers, payers, industry, hospitals and other health systems, and policymakers. Research partners participated in PCORI-funded studies in different ways including the following: · Selecting which outcomes of interest to patients to measure · Designing studies to minimize burdens for clinicians and patient study participants · Recruiting patient study participants · Collecting and analyzing relevant health data · Publicly disseminating study findings Source: GAO summary of PCORI information. | GAO‑25‑107462 |

Studies we reviewed and researchers from four of our selected studies reported instances in which researchers had challenges engaging research partners as planned.[18] Some literature reported that research partners sometimes had competing demands that conflicted with research study schedules. Researchers from four of our selected studies also reported one or more instances in which they had to replace a research partner during studies. For example, some research partners were unprepared for the amount of time needed to contribute to studies and had to drop out, which created challenges meeting study milestones, according to one article and one researcher. Some studies mitigated these challenges by allowing for flexible meeting times or providing research partners with incentives for their attendance.

In other cases, research partners may have lacked the necessary institutional knowledge or technology to participate as planned. The literature we reviewed described instances in which research partners had limited participation in studies because they did not understand how to contribute. Some articles suggested that research partners could have benefited from some training about clinical research to facilitate their participation. In other cases, researchers did not implement research partners’ suggestions for studies, such as which outcomes to measure. For example, research partners suggested changes to the study that researchers could not implement due to budgetary constraints, among other reasons, according to some articles. This meant that researchers sometimes had difficulties encouraging participation from research partners throughout studies, according to some literature we reviewed. In addition, some articles stated that research partners sometimes lacked appropriate technology, such as internet access or a telephone, or transportation to participate in meetings, which limited their ability to participate in studies. Some articles recommended assessing research partners’ access to appropriate technology or transportation and addressing any gaps to encourage participation.

PCORI representatives noted that engagement can be a challenge for research in general. PCORI provides resources to help researchers to engage with research partners, including assigning an engagement officer to studies.[19] For example, PCORI has developed guidance and trainings to help researchers and research partners prepare to work together. In addition, PCORI funds engagement awards to assist researchers in more successfully incorporating stakeholders into the research process.[20]

Challenges Recruiting and Retaining Patients as Study Participants

Studies we reviewed and researchers we interviewed from four of our selected studies reported challenges recruiting or retaining an adequate number of patients as study participants for their PCORI-funded studies. Some articles and several researchers noted that study participants reportedly declined to participate in studies due to disinterest or mistrust of the study process, among other reasons. In other cases, clinicians responsible for patient recruitment at study sites did not recruit enough patients due to a lack of time, resources, or interest. As a result, researchers had to provide additional support and trainings for clinicians, according to some articles and researchers. Some studies mitigated these challenges by having research partners review recruitment materials or help recruit study participants because patients were more likely to trust them.

PCORI representatives acknowledged that this challenge can affect PCORI-funded studies and noted that it is common with all pragmatic research, that is, studies conducted in real-world settings, such as medical clinics and hospitals. To support funded researchers, PCORI facilitates learning networks for those studying specific topics, such as palliative care and maternal morbidity and mortality. In addition, PCORI developed a new type of study award in 2020 that provides researchers with greater flexibility to potentially modify their study plans at certain points in the process. Such modifications could include adopting new recruitment strategies for patient study participants.

|

Consideration of Potential Burdens and Economic Impacts in PCORI-funded Studies The Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020 requires Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI)-funded studies to examine potential burdens and economic outcomes of the medical treatments and services being studied, such as effects on future costs of care and utilization of health care services. PCORI released guidance in 2021 that provides information on how researchers can incorporate economic outcomes into PCORI-funded research, such as any program costs for clinicians to implement the studied medical treatment or service in their practices and any out-of-pocket costs for patients from receiving the treatment or service. PCORI policy prohibits funding studies that analyze cost effectiveness or provide coverage, payment, or policy recommendations due to statutory limitations. Source: Pub. L. No. 116-94, div. N, tit. I, § 104, 133 Stat. 2534, 3097 (2019). GAO summary of PCORI information. | GAO‑25‑107462 |

The costs of medical treatments studied by researchers may have been a barrier to participation for some study participants, according to several researchers and some literature. For example, some researchers said that eligible patients declined to participate in PCORI-funded studies because the costs of the studied treatment were high or not covered by insurance.

According to PCORI representatives, it has not routinely covered medical costs for study participants because PCORI-funded studies are intended to study treatments and services with proven efficacy or widespread clinical use, and insurance payers likely already offer coverage for the treatments and services. Covering those costs would also limit PCORI’s ability to fund research, representatives said. In response to this challenge, PCORI began a pilot program in 2021 that allows researchers to request coverage for some patient care costs in their funding applications.[21] PCORI representatives acknowledged, however, that covering high patient care costs related to some medications, devices, and other medical technologies may not be feasible.

Challenges and Benefits of Meeting PCORI’s Reporting Requirements

Researchers we interviewed from five of our selected studies cited challenges meeting PCORI’s reporting requirements, describing them as burdensome. As conditions for receiving PCORI study funding, researchers must submit progress reports to PCORI every 6 months and, as required by law, undergo PCORI peer review of their final research.[22] Such requirements meant that researchers had to submit more documentation or information than typical from other research funders, which was sometimes burdensome, according to several researchers. For example, according to several researchers, their studies received more feedback during PCORI peer review than expected or feedback that was difficult to incorporate and thus took longer to complete than expected. PCORI’s requirements could be overwhelming while conducting PCORI-funded studies, according to several researchers we interviewed.

PCORI representatives said they have streamlined the PCORI peer review process and reduced the time it takes to complete it. In addition, PCORI representatives said PCORI continues to offer regular trainings and town halls to discuss its specific requirements with researchers, including its reporting requirements.

Conversely, researchers from three of our selected studies and one stakeholder acknowledged that the requirements were useful to their studies. For example, the required PCORI peer review resulted in better final reports and improved the readability for all audiences, according to some researchers. In addition, the semiannual progress reports created better accountability while conducting studies and helped the research teams better organize their plans and develop milestones, according to several researchers and one stakeholder. Further, several researchers we interviewed reported that PCORI provided more support throughout their studies than other research funders. For example, one researcher we interviewed said that they were able to mitigate challenges by meeting with their program officer regularly while conducting the study.

PCORI and AHRQ Employ Various Research Dissemination and Implementation Methods

PCORI uses various methods to help disseminate and implement findings from the studies it funds, including requirements for researchers to share findings. Meanwhile, AHRQ disseminated selected PCORI-funded studies through agency media and helped to implement study findings through one program, according to agency officials.

PCORI Requires Researchers to Share Findings and Funds Efforts to Implement Study Findings

PCORI requires researchers to share findings from PCORI-funded research. In addition, it has awards that researchers and others can apply for to help further disseminate and implement study findings into clinical practice.[23]

Researcher requirements. PCORI requires researchers to develop dissemination and implementation plans, communicate study findings to patient study participants, review PCORI’s summaries of study findings, and make reports publicly accessible.

· Develop dissemination and implementation plans. As part of the original research award application, researchers must describe the potential for public dissemination and implementation of the findings into clinical practice. According to PCORI representatives, they want researchers to consider the usefulness and the kinds of potential stakeholders involved in dissemination. The application requires researchers to describe potential strategies for disseminating and implementing the results of the study to settings beyond those used in the research study and potential challenges with dissemination and implementation.

For example, one plan in our sample noted that study findings could be disseminated through issue briefs and listed a nonprofit medical society as one organization that could help disseminate results. After the study was completed, the researchers developed an issue brief sharing the results of the study and presented findings at the annual meeting of the medical society in May 2021. Another plan noted that health system networks of primary care practices could be reluctant to implement changes into their electronic health records systems based on study findings. The plan described potential ways to mitigate this through staff training and access to the researchers’ electronic health records programming approach.

· Communicate study findings to patients. PCORI directs researchers to share findings with patient study participants, where possible.[24] As part of the application process, researchers must describe how they plan to share study findings with patient study participants and to budget for these activities. Researchers have shared study findings through methods such as infographics, fact sheets, and newsletters.

· Review summaries for health care professionals. PCORI requires that researchers review summaries of study findings developed by PCORI that are tailored to the general public and health care professionals. PCORI then posts these summaries to its website along with the full research report.

· Make reports publicly accessible. PCORI requires researchers to make any peer-reviewed articles reporting findings from studies funded by PCORI available through PubMed Central, a free National Institutes of Health database.[25]

In addition, PCORI encourages researchers to work with research partners to further disseminate PCORI-funded research. For instance, one PCORI-funded researcher we interviewed said they worked with research partners to disseminate study findings to media outlets focused on the medical industry and presented findings at a meeting of an organization that also develops guidelines for clinical practice. This researcher noted that they jointly presented the study results to the media with their patient partners. Another researcher we interviewed said that research partners can help identify relevant and key community organizations to help disseminate the research results, and they can also help interpret research findings to better enable health care providers to implement the findings. This researcher noted that research partners disseminated findings from a PCORI-funded study, which found patients with diabetes and higher average blood sugar levels had a greater risk of hospitalization for COVID-19 than those with lower average blood sugar levels.[26]

Dissemination, implementation, and stakeholder engagement awards. PCORI awards funds to help disseminate and implement findings from PCORI-funded studies, for which researchers and other stakeholders can apply: dissemination, implementation, and engagement awards. Engagement awards support bringing stakeholders into the research process. (See table 2.) In fiscal year 2024, PCORI obligated $73 million (11 percent of total PCORI award obligations) for dissemination and implementation awards and $17 million (3 percent of total PCORI award obligations) for stakeholder engagement awards.[27] (See appendix III for past amounts for these awards.) According to PCORI representatives, over 100 dissemination projects, including those funded through dissemination awards and stakeholder engagement awards, and 80 implementation projects have been completed or are ongoing since PCORI began making these kinds of awards in December 2016.

Table 2: Information on PCORI’s Awards to Disseminate and Help Implement Findings from Comparative Clinical Effectiveness Research

|

|

Dissemination award |

Implementation award |

Stakeholder engagement award for disseminationa |

|

Purpose |

Supports PCORI-funded researchers’ activities to increase knowledge and awareness of the findings from PCORI-funded research |

Supports activities to integrate findings from PCORI-funded research into health care delivery |

Supports activities to increase knowledge and awareness of and build context around findings from PCORI-funded research |

|

Intended applicant |

Researchers previously funded by PCORI |

Open to researchers, health systems participating in PCORI’s Health Systems Implementation Initiative, and othersb |

Stakeholder organizations that have established relationships with target audiences and are trusted sources of information |

|

Maximum project award and time frame |

$300,000 for 36 months |

$3 million for 42 months/ $3.5 million for 48 months |

$300,000 for 24 months |

|

Example |

One award to help raise awareness among clinicians of findings from a PCORI-funded study to prevent blood clots after fractures. Study findings are being disseminated through briefs, podcasts, and social media. |

A variety of health systems received awards to implement the findings from a PCORI-funded study on prescribing appropriate antibiotics for children with acute respiratory tract infections. |

A patient education organization received one award to work with patients and an advertising agency to develop strategies for educating people experiencing urinary incontinence on treatment options described in a PCORI-funded systematic review. |

Source: GAO summary of information from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). | GAO‑25‑107462

aEngagement awards support bringing stakeholders into the research process. Some engagement awards are specific to supporting dissemination activities, and other engagement awards help stakeholders to contribute to research as research partners.

bHealth Systems Implementation Initiative provides funding for health systems for projects that promote the implementation of specific PCORI-funded research findings within their health care delivery settings.

In addition to making these awards, PCORI conducts other activities to disseminate study findings. Examples of these activities include an annual meeting to highlight the studies PCORI funds and regional meetings with stakeholders on specific topics, such as mental and behavioral health in children and youth. PCORI representatives also noted that they communicate with stakeholders, such as organizations that pay for health care services known as payers, patients, and clinicians, to discuss findings from PCORI-funded research.

Selected stakeholders and researchers we interviewed from our selected studies suggested ways PCORI could improve dissemination of the studies it funds. For their part, PCORI representatives responded to these suggestions.

· Further collaborate with stakeholders. Six of nine stakeholders we spoke to suggested ways that PCORI could work more closely with their respective organizations to disseminate studies. For example, one of these stakeholders said PCORI could participate in their organization’s annual national meetings to help disseminate study findings to the public. Additionally, two stakeholders and one researcher we interviewed said that PCORI could work more closely with medical specialty organizations that develop clinical guidelines for clinicians. For example, PCORI could fund studies in areas that clinical guideline developers previously identified as having research gaps, which could be an effective way to implement the findings from this research.

According to PCORI representatives, they have presented at a number of annual meetings and conferences, such as National Rural Health Association and National Kidney Foundation. PCORI representatives also noted that they communicate with guideline developers on potential research topics and encourage research applicants to review evidence gaps in guidelines.

· Increase accessibility of study summaries. Four stakeholders told us that short, easily understandable blurbs or conclusionary statements would help to further disseminate study findings and make it more likely that the members of their organizations would read the studies. Additionally, two stakeholders noted that PCORI could promote their studies more through social media. PCORI publishes summaries of study findings for health care professionals and the public and disseminates information through social media and other electronic means, such as regular newsletters.

· Increase availability of dissemination awards and funding. Researchers we interviewed from three of the six selected studies suggested that PCORI could increase the availability of dissemination funding, either by making more dissemination awards, increasing the dollar amount of funding for its individual dissemination awards, or including funding for dissemination as part of the original research award. Specifically, one researcher said that the amount of funding provided for the dissemination awards was not enough to cover the work required.[28] PCORI requires that researchers use dissemination awards to actively disseminate research findings to specific target populations, include stakeholders to provide input on the dissemination approach, and evaluate these dissemination activities. Also, the two other researchers noted that PCORI could better promote existing dissemination awards to help make it easier for researchers to apply.

According to PCORI representatives, they have increased the types of dissemination and implementation awards, such as introducing the Health Systems Implementation Initiative in 2023. PCORI representatives also said that they promote awards through different methods, such as an annual webinar, town halls, and targeted emails and newsletters.

AHRQ Used Agency Media and Various Means to Disseminate and Help Implement Findings from Selected PCORI-Funded Studies

Since 2016, AHRQ has disseminated findings from 16 PCORI-funded studies it has conducted, as of March 2025, according to officials.[29] These studies, known as systematic reviews, evaluate and synthesize existing research on a clinical issue across multiple studies.[30] To disseminate PCORI-funded findings from these systematic reviews, AHRQ used different agency media tools, including an electronic newsletter, social media, blog posts, and emails sent through the agency listserv. For example, AHRQ disseminated the findings from two related PCORI-funded systematic reviews on attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder through its electronic newsletter and 54 social media posts in the most recently completed fiscal year, according to agency officials.[31]

AHRQ officials said they use the following criteria to determine whether to disseminate study findings through agency media: (1) the study is published in a top-tier or specialty journal, such as the New England Journal of Medicine or American Family Physician; (2) the study findings are actionable; and (3) the study findings are important to the field or can change health care practices. According to AHRQ officials, they may also disseminate study findings if the findings are not published in a journal but have value to a specific audience or if the study raises awareness about an AHRQ priority where more research is needed.

Since 2016, when the first PCORI-funded study was completed, AHRQ has taken the research findings of one PCORI-funded systematic review and developed a dissemination and implementation project to help implement those findings into the clinical setting.[32] This project, Managing Urinary Incontinence, is through the EvidenceNOW program and was launched in February 2022.[33] The project provides support, such as toolkits and clinician guides, to primary care practices to help improve the delivery of nonsurgical care to women with urinary incontinence.

While PCORI has recommended other studies for AHRQ program consideration since 2016, AHRQ officials determined that those single studies either (1) did not meet the agency’s criteria for the strength of the body of evidence, which usually involves evidence from multiple studies, or (2) could not feasibly be implemented into clinical practice.[34] AHRQ officials said PCORI-funded studies comprise mostly of single study findings, and as single studies they do not meet the strength of evidence needed for widespread implementation. AHRQ officials said that they have only found that evidence from systematic reviews fully meet these criteria.

Systematic evidence reviews, which can include the review of PCORI-funded studies within the body of existing research, is the first step to translating research into actionable evidence for implementation into clinical practice, according to AHRQ officials. For this reason, AHRQ has coordinated closely with PCORI in conducting systematic reviews through its Evidence-based Practice Center program, according to AHRQ officials. PCORI and AHRQ then publicly share study findings from these reviews through their respective websites.

PCORI Uses Key Practices to Assess Dissemination and Implementation Efforts, but AHRQ Has Not Done So for Its Entire Portfolio

PCORI uses key performance management practices to regularly assess the performance of its efforts to disseminate and help implement findings from comparative clinical effectiveness research. Similarly, AHRQ used these key practices to assess the performance of its three largest dissemination and implementation programs. However, although AHRQ is in the process of planning an evaluation of its entire dissemination and implementation portfolio, the effort has been delayed, according to officials, and AHRQ has not yet issued a request for proposals from potential contractors to conduct the evaluation.

PCORI Uses Key Practices to Regularly Assess Performance of Its Dissemination and Implementation Activities

PCORI uses key performance management practices to regularly assess the performance of its efforts to disseminate and implement findings from comparative clinical effectiveness research.

In our prior work, we identified several practices for performance management that help organizations and agencies achieve results and improve performance.[35] (See text box for selected key practices.)

|

Key Performance Management Practices Identified by GAO 1. Establish goals, which communicate the results that an organization or agency seeks to achieve. Goals guide the organization’s or agency’s programs and allow decision makers, staff, and stakeholders to assess performance by comparing planned and actual results. Goals comprise: · Long-term goals, which are the desired outcomes for the organization’s or agency’s programs and set a general direction for a program’s efforts. · Near-term goals, which are the specific results a program is expected to achieve in the near-term. Our prior work has found that it can be beneficial for near-term goals to have specific targets and time frames. 2. Establish performance measures, which are concrete, objective, observable conditions that allow the organization or agency to assess the progress made toward achieving each goal. 3. Use performance information, which allows an organization or agency to regularly assess results and inform decisions to ensure further progress toward achieving goals. |

Source: GAO‑23‑105460, GAO‑23‑105650, and GAO‑24‑106271. | GAO‑25‑107462

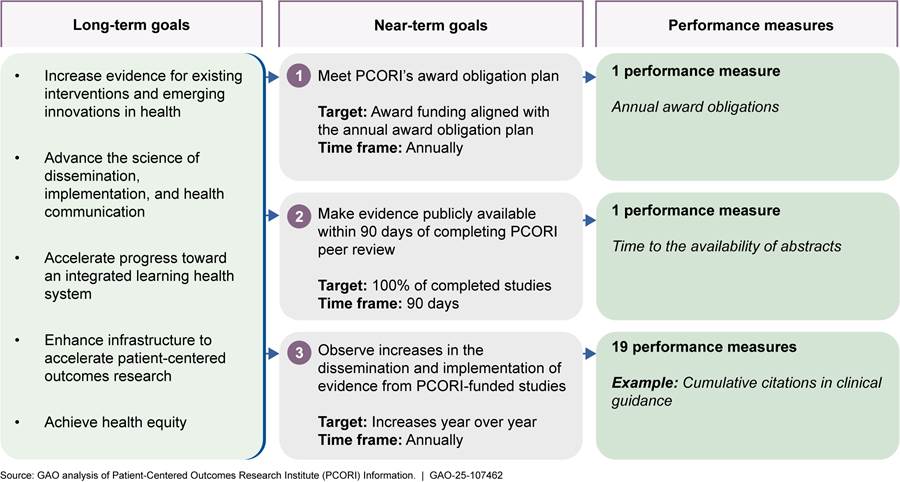

In 2022, PCORI updated its strategic plan and evaluation framework, resulting

in five long-term goals and three near-term goals with targets and time frames

to measure performance against its goals.[36]

To assess progress toward its goals, PCORI collects performance measure data on

20 quantitative measures.[37]

PCORI collects these data through internal systems, such as its study database,

and external systems, such as Altmetric.[38]

(See fig. 4).

Figure 4: PCORI’s Goals and Related Performance Measures to Assess Its Dissemination and Implementation Activities, as of Fiscal Year 2025

Note: In addition to its 20 quantitative measures, PCORI

also assesses one qualitative performance measure which provides examples of

how comparative clinical effectiveness research findings from PCORI-funded

studies are implemented.

According to PCORI performance measure data we reviewed from fiscal years 2020 through 2024, the organization generally met its targets across all 5 fiscal years for its 20 quantitative measures.[39] See appendix IV for detailed data on PCORI’s performance measures and targets.

PCORI regularly reports to its Board of Governors on the organization’s performance. The Board of Governors oversees the organization’s performance monitoring and evaluation efforts and provides guidance on what to measure, according to representatives. For example, PCORI collects data for five performance measures to track citations of PCORI-funded studies across various health resources, which the Board of Governors uses to assess progress on implementation, according to PCORI representatives.[40]

AHRQ Assessed Performance of Its Largest Dissemination and Implementation Programs

AHRQ used key performance management practices to assess the performance of its top three funded dissemination and implementation programs – Evidence-based Practice Centers, EvidenceNOW, and Clinical Decision Support. These programs comprised 80 percent of AHRQ’s dissemination and implementation portfolio funding from fiscal years 2019 through 2024. AHRQ officials said that for each of these programs, AHRQ established long- and near-term goals and related performance measures and regularly assessed progress.

For example, AHRQ’s Evidence-based Practice Center program established four long-term goals and included four near-term goals and associated performance measures. To assess progress toward its goals, the Evidence-based Practice Center program annually collected performance measure data such as the number of completed research reports, number of new projects started, and number of federal and non-federal partnerships. (See table 3.) See appendix V for a full list of AHRQ’s goals and performance measures for its top three funded dissemination and implementation programs.

Table 3: Examples of AHRQ’s Goals and Related Performance Measures to Assess Its Dissemination and Implementation Programs

|

Programs |

Long-term goals |

Near-term goals |

Performance measures |

|

Evidence-based Practice Centers |

Improve future evidence for health care decisions by reducing evidence gaps and improving evidence quality by promoting higher-quality clinical trials and registries |

Increase the data available through AHRQ’s systematic review data repository Target: At least 20 new projects published Time frame: annually, 2018-2024 |

Example: Number of new projects published in AHRQ’s systematic review data repository |

|

EvidenceNOW: Advancing Heart Healtha |

Help practices implement evidence to improve aspirin use, blood pressure control, cholesterol management, and smoking cessation |

Provide external support through cooperatives to small- and medium-sized primary care practices Target: Seven cooperatives to 1,750 small- and medium-sized primary care practices Time frame: 2015–2018 |

Example: Percentage increase in smoking screening and cessation counseling |

|

Clinical Decision Support |

Build a wide stakeholder community, including patients and clinicians, to accelerate the science and adoption of clinical decision supportb |

Engage the stakeholder community by convening meetings of multiple stakeholder groups, including patients, clinicians, health care system leaders, developers of clinical decision support technologies, payers, and others Target: An annual conference, multiple meetings, and presentations Time frame: fiscal year 2023 to fiscal year 2026 |

Example: Number of stakeholders engaged |

Source: Information from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). | GAO‑25‑107462

aThe EvidenceNOW program is made up of multiple projects related to specific health conditions, specifically Advancing Heart Health, Managing Urinary Incontinence, Managing Unhealthy Alcohol Use, and Building State Capacity. Each project has specific near-term goals and performance measures.

bClinical decision support encompasses a variety of tools, such as clinical guidelines, to enhance decision-making in the clinical workflow.

In addition to performance measures, AHRQ collected other performance information through annual reports and program evaluations. For example:

· For the Evidence-based Practice Center program, in which AHRQ collaborated with PCORI to assess evidence from multiple studies, AHRQ published annual reports. These reports summarized a range of program accomplishments, such as the number of completed research reports that year and number of website views.

· For the EvidenceNOW program, which is made up of four projects, AHRQ completed evaluations for two of the four projects and was in the process of completing evaluations for the other projects when we conducted our review.[41] For example, one study that evaluated the EvidenceNOW: Advancing Heart Health project showed that the project improved heart health practices, such as increased smoking screening and cessation counseling.

· For the Clinical Decision Support program, AHRQ funded an independent evaluation and released a final report in 2023.[42] This evaluation examined the extent to which the program promoted the dissemination of comparative clinical effectiveness research findings through clinical decision support tools, among other things.[43] The evaluation recommended that AHRQ explore additional ways to disseminate products tailored to stakeholders, such as through press releases or infographics. It also proposed that AHRQ could collaborate more closely with PCORI to take steps to improve how PCORI research is disseminated through the Clinical Decision Support program.[44] AHRQ officials told us they have taken steps toward addressing this recommendation, such as identifying a body of PCORI-funded research that could be incorporated into the clinical decision support tools.

AHRQ officials said they have used performance information collected to inform management decisions. For example:

· AHRQ officials said they increased investments and prioritized areas of higher interest to the public based on data collected by the Evidence-based Practice Center program that tracked mentions of study findings in various media sources.

· AHRQ officials said they used data, such as website and social media views, collected by the Clinical Decision Support program to determine if more targeted outreach is needed or if they need to change their messaging to something that may resonate better with audiences.

AHRQ Lacked Some Key Performance Management Practices for Its Entire Dissemination and Implementation Portfolio

In addition to assessing the individual performance of AHRQ’s three largest dissemination and implementation programs, AHRQ officials said they were also in the process of developing a wider evaluation of the agency’s entire dissemination and implementation portfolio. This portfolio included these three dissemination and implementation programs and other individual projects, such as commissioning a study, providing training to clinicians to help implement evidence-based interventions, and disseminating and helping to implement a training playbook.[45]

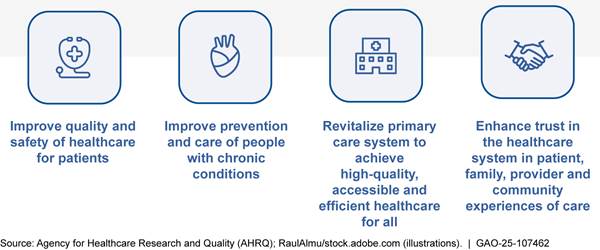

While AHRQ had established long-term goals for its dissemination and implementation portfolio (see fig. 5), AHRQ did not have other key performance management practices in place—specifically near-term goals and performance measures. According to AHRQ officials, the planned evaluation was to include the development of near-term goals and performance measures for the portfolio. The evaluation also planned to take into account existing program performance assessments to help determine the effectiveness of Trust Fund investments, according to a draft statement of work we reviewed dated December 2022.

Figure 5: Long-Term Goals for AHRQ’s Dissemination and Implementation Portfolio

Since Congress charged AHRQ to disseminate and promote the incorporation of findings from federally funded comparative clinical effectiveness research into clinical practice in 2010, the agency has not conducted a comprehensive evaluation of its activities. In 2020, we reported AHRQ planned to assess the impact of its Trust Fund investments from 2020 to 2028 by conducting an evaluation for its dissemination and implementation activities.[46]

However, this evaluation has been delayed. AHRQ officials said the departure in August 2024 and March 2025 of key AHRQ staff overseeing the agency’s Trust Fund activities delayed progress on the evaluation. In early March 2025, AHRQ officials said that they had not yet solicited proposals for a contractor to conduct the evaluation and reported that the timing of awarding a contract may be affected by shifting priorities given new departmental leadership, raising uncertainty as to when the evaluation will be completed. In late March 2025, HHS announced staff reductions, including the restructuring of AHRQ into a newly created Office of Strategy. Given the previous delays and these recent changes, it remains unclear whether the evaluation will be conducted as planned.

We previously reported that evaluations can help an organization assess progress towards strategic long-term goals and objectives and better understand what led to the results it achieved or why desired results were not achieved.[47] In addition, key to an organization’s efforts to manage performance is its ability to set near-term goals that align with strategic long-term goals and objectives.[48] We also reported that an organization should regularly assess progress toward its goals using performance measures.

HHS would be better positioned to assess how its entire portfolio of dissemination and implementation programs promotes evidence-based, patient-centered care and improved health outcomes, if it proceeds with the planned evaluation that incorporates and implements near-term goals and performance measures.

Conclusions

Effective dissemination and implementation of comparative clinical effectiveness research findings can improve health care decision making, expand the practice of evidence-based treatments, and thereby help to improve population health. However, HHS has not conducted a comprehensive evaluation of its comparative clinical effectiveness research activities as planned. Ensuring that the planned evaluation of its dissemination and implementation portfolio follows key performance management practices would help to determine the extent to which the dissemination and implementation efforts are successful or if changes are warranted. It would also help assess whether ongoing efforts supported by the Trust Fund are achieving the agency’s aim of improving health outcomes by promoting evidence-based, patient-centered care.

Recommendation for Executive Action

We are making the following recommendation to HHS:

The Secretary of HHS should complete an evaluation of the dissemination and implementation portfolio efforts supported by the Trust Fund, as planned, including developing and implementing near-term goals and associated performance measures to regularly assess performance. (Recommendation 1)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute and the Department of Health and Human Services for review and comment. PCORI provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate. HHS neither agreed nor disagreed with our recommendation, noting that it continues to consider and review the recommendation and would provide an update in the future. We maintain that the recommendation is valid. HHS’s comments are reproduced in appendix VI.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Executive Director of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, the Secretary of Health and Human Services, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at GordonLV@gao.gov. Contacts points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix VII.

Leslie V. Gordon

Director, Health Care

List of Committees

The Honorable Mike Crapo

Chairman

The Honorable Ron Wyden

Ranking Member

Committee on Finance

United States Senate

The Honorable Bill Cassidy, M.D.

Chairman

The Honorable Bernard Sanders

Ranking Member

Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions

United States Senate

The Honorable Brett Guthrie

Chairman

The Honorable Frank Pallone, Jr.

Ranking Member

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

The Honorable Jason Smith

Chairman

The Honorable Richard Neal

Ranking Member

Committee on Ways and Means

House of Representatives

Appendix I: Selected Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute-Funded Studies and Literature Review

To describe researchers’ experiences conducting PCORI-funded studies, we interviewed the researchers and reviewed the progress reports and final research reports of six PCORI-funded studies.[49] See table 4 for more information.

|

Study |

Award amount |

Year awarded – |

Study design |

|

Cardiovascular health |

|||

|

Comparing the Safety and Effectiveness of Low-Dose versus High-Dose Aspirin to Prevent Problems from Heart Disease — The ADAPTABLE Study—A PCORnet® Studya |

$18,184,210 |

2015–2023 |

Randomized controlled trial |

|

Comparing Two Medicines to Prevent Blood Clots after Treatment for Fractures — The PREVENT CLOT Study |

$11,198,840 |

2016–2023 |

Randomized controlled trial |

|

Diabetes |

|||

|

Comparing Three Methods to Help Patients Manage Type 2 Diabetes |

$1,802,800 |

2013–2018 |

Randomized controlled trial |

|

Comparing the Safety and Effectiveness of Metformin with Other Medicines for Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Chronic Kidney Disease |

$2,225,880 |

2018–2023 |

Observational study |

|

Urinary Incontinence |

|||

|

Nonsurgical Treatments for Urinary Incontinence in Women: A Systematic Review Update |

$267,750 |

2017–2018 |

Systematic review |

|

Comparing Surgeries for Women Who Have Both Cancer of the Uterus and Bladder Problems |

$2,694,860 |

2015–2020 |

Observational study |

Source: GAO analysis of Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) information. | GAO‑25‑107462

Note: The year awarded refers to the year PCORI approved the research study or project for funding. The year completed refers to the year in which all work outlined in a study’s contract is completed.

aPCORnet® studies must meet certain criteria,

which includes using PCORI’s National Patient-Centered Clinical Research

Network common data model.

Literature Review

To identify researchers’ challenges from published research about conducting studies funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), we conducted a literature search among recently published articles. Specifically, we searched for relevant articles published within the United States since 2019. We conducted a structured search of the Scopus, Dimensions AI, and SciSearch databases for relevant peer reviewed and industry journals such as Health Affairs and the Journal of General Internal Medicine. Key terms included various combinations of “Improving Outcomes Important to Patients,” “PCORI,” “comparative effectiveness,” “patient-centered outcome,” and “pragmatic clinical trial.” From all database sources, we identified 204 articles after excluding duplicates.

We first reviewed the abstracts for each of these articles for relevancy in describing challenges from conducting PCORI-funded studies or any lessons learned and mitigation strategies for such challenges, such as challenges or trade-offs. For those abstracts we found relevant, we reviewed the full article and excluded those where the research (1) did not specifically describe PCORI-funded studies; or (2) was a conference presentation. Two analysts independently reviewed each article and recommended its inclusion or exclusion in the literature review.

We included 38 articles that described researchers’ challenges conducting PCORI-funded studies:

Ahmad, Faraz S., Iben M. Ricket, Bradley G. Hammill, et al. “Computable Phenotype Implementation for a National, Multicenter Pragmatic Clinical Trial Lessons Learned From ADAPTABLE.” Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes, vol. 13, no. 6 (2020): 355–364, doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.119.006292.

Allen, Nancy A., Vanessa D. Colicchio, Michelle L. Lichtman, et al. “Hispanic Community-Engaged Research: Community Partners as Our Teachers to Improve Diabetes Self-Management.” Hispanic Health Care International, vol. 17, no. 3 (2019):125–132, doi.org/10.1177/1540415319843229.

Bailey, James E., Cathy Gurgol, Eric Pan, et al. “Early Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Experience with the Use of Telehealth to Address Disparities: Scoping Review.” Journal of Medical Internet Research, vol. 23, no. 12 (2021): 1 – 19, doi.org/10.2196/28503.

Brock, Donna-Jean P., Paul A. Estabrooks, Maryam Yuhas, et al. “Assets and Challenges to Recruiting and Engaging Families in a Childhood Obesity Treatment Research Trial: Insights from Academic Partners, Community Partners, and Study Participants.” Frontiers in Public Health, vol. 9, (2021): 1–11, doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.631749.

Browne, Teri, Shamika Jones, Ashley N. Cabacungan, et al. “The Impact of COVID-19 on Patient, Family Member, and Stakeholder Research Engagement: Insights from the PREPARE NOW Study.” Journal of General Internal Medicine, vol. 37, (2022): S64–S72, doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-07077-w.

Browne, Teri, Amy Swoboda, Patti L. Ephraim, et al. “Engaging Patients and Family Members to Design and Implement Patient-Centered Kidney Disease Research.” Research Involvement and Engagement, vol. 6, no. 66 (2020): 1–11, doi.org/10.1186/s40900-020-00237-y.

Carolan, Kelsi, Marjory Charlot, Cyrena Gawuga, et al. “Assessing Cancer Center Researcher and Provider Perspectives on Patient Engagement.” Translational Behavioral Medicine, vol. 10, no. 6 (2020): 1573–1580, doi.org/10.1093/tbm/ibz132.

De Forcrand, Claire, Mara Flannery, Jeanne Cho, et al. “Pragmatic Considerations in Incorporating Stakeholder Engagement into a Palliative Care Transitions Study.” Medical Care, vol. 59, no. 8 (2021): S370–S378, doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000001583.

Delgado, M. Kit, Anna U. Morgan, David A. Asch, et al. “Comparative Effectiveness of an Automated Text Messaging Service for Monitoring COVID-19 at Home.” Annals of Internal Medicine, vol. 175, no. 2 (2022): 179–190, doi.org/10.7326/M21-2019.

D’Orazio, Brianna, Jessica Ramachandran, Chamanara Khalida, et al. “Stakeholder Engagement in a Comparative Effectiveness/ Implementation Study to Prevent Staphylococcus Aureus Infection Recurrence: CA-MRSA Project (CAMP2).” Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, vol. 16, no. 1 (2022): 45–60, doi.org/10.1353/cpr.2022.0005.

Dy, Tiffany, Winifred J. Hamilton, C. Bradley Kramer, et al. “Stakeholder Engagement in Eight Comparative Effectiveness Trials in African Americans and Latinos with Asthma.” Research Involvement and Engagement, vol. 8, no. 63 (2022): 1–16, doi.org/10.1186/s40900-022-00399-x.

Edwards, Hillary A., Jennifer Huang, Liz Jansky, and C. Daniel Mullins. “What Works When: Mapping Patient and Stakeholder Engagement Methods along the Ten-Step Continuum Framework.” Journal of Comparative Effectiveness Research, vol. 10, no. 12 (2021): 999–1017, doi.org/10.2217/cer-2021-0043.

Forsythe, Laura P., Kristin L. Carman, Victoria Szydlowski, et al. “Patient Engagement in Research: Early Findings from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute.” Health Affairs, vol. 38, no. 3 (2019): 359–367, doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05067.

Heckert, Andrea, Laura P. Forsythe, Kristin L. Carman, et al. “Researchers, Patients, and Other Stakeholders’ Perspectives on Challenges to and Strategies for Engagement.” Research Involvement and Engagement, vol. 6, no. 60 (2020): 1-18, doi.org/10.1186/s40900-020-00227-0.

Kluger, Benzi M., Maya Katz, Nicholas Galifianakis, et al. “Does Outpatient Palliative Care Improve Patient-Centered Outcomes in Parkinson’s Disease: Rationale, Design, and Implementation of a Pragmatic Comparative Effectiveness Trial.” Contemporary Clinical Trials, vol. 79, (2019): 28 – 36, doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2019.02.005.

Kwan, Bethany M., Jenny Rementer, Natalie D. Ritchie, et al. “Adapting Diabetes Shared Medical Appointments to Fit Context for Practice-Based Research (PBR).” Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, vol. 33, no. 5 (2020): 716–727, doi.org/ 10.3122/jabfm.2020.05.200049.

Lin, Kueiyu Joshua, Gary E. Rosenthal, Shawn N. Murphy, et al. “External Validation of an Algorithm to Identify Patients with High Data-Completeness in Electronic Health Records for Comparative Effectiveness Research.” Clinical Epidemiology, vol. 12 (2020): 133–141, doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S232540.

MacDonald-Wilson, Kim L., Kelly Williams, Cara E. Nikolajski, et al. “Promoting Collaborative Psychiatric Care Decision-Making in Community Mental Health Centers: Insights from a Patient-Centered Comparative Effectiveness Trial.” Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, vol. 44, no. 1 (2021): 11–21, doi.org/10.1037/prj0000455.

Martinez, Jenny, Catherine Verrier Piersol, Kenneth Lucas, and Natalie E. Leland. “Operationalizing Stakeholder Engagement Through the Stakeholder-Centric Engagement Charter (SCEC).” Journal of General Internal Medicine, vol. 37, (2022): 105–108, doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-07029-4.

Mauer, Maureen E., Tandrea Hilliard-Boone, Karen Frazier, et al. “Examining How Study Teams Manage Different Viewpoints and Priorities in Patient-Centered Outcomes Research: Results of an Embedded Multiple Case Study.” Health Expectations, vol. 26, no. 4 (2023): 1606–1617, doi.org/10.1111/hex.13765.

Mauer, Maureen, Rikki Mangrum, Tandrea Hillard-Boone, et al. “Understanding the Influence and Impact of Stakeholder Engagement in Patient-Centered Outcomes Research: a Qualitative Study.” Journal of General Internal Medicine, vol. 37, (2022): 6–13, doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-07104-w.

McElfish, Pearl A., Britni L. Ayers, Holly C. Felix, et al. “How Stakeholder Engagement Influenced a Randomized Comparative Effectiveness Trial Testing Two Diabetes Prevention Program Interventions in a Marshallese Pacific Islander Community.” Journal of Translational Medicine, vol. 17, no. 42 (2019): 1–8, doi.org/10.1186/s12967-019-1793-7.

Mitchell, Gordon R., E. Johanna Hartelius, David McCoy, and Kathleen McTigue. “Deliberative Stakeholder Engagement in Person-Centered Health Research.” Social Epistemology, vol. 36, no. 1 (2022): 21– 42, doi.org/10.1080/02691728.2021.1918280.

Neuman, Mark D., Michael D. Kappelman, Elliot Israel, et al. “Real-World Experiences with Generating Real-World Evidence: Case Studies from PCORI’s Pragmatic Clinical Studies Program.” Contemporary Clinical Trials, vol. 98, (2020): 1–6, doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2020.106171.

Nguyen, Huong Q., Carmit McMullen, Eric C. Haupt, et al. “Findings and Lessons Learnt from Early Termination of a Pragmatic Comparative Effectiveness Trial of Video Consultations in Home-Based Palliative Care.” BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care, vol. 12, (2022): e432–e440, doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002553.

Nguyen, Huong Q., Richard A. Mularski, Paula E. Edwards, et al. “Protocol for a Noninferiority Comparative Effectiveness Trial of Home-Based Palliative Care (HomePal).” Journal of Palliative Medicine, vol. 22, no. S1 (2019): S20 –S33, doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2019.0116.

Nowell, W. Benjamin, Peter A. Merkel, Robert N. McBurney, et al. “Patient‑Powered Research Networks of the Autoimmune Research Collaborative: Rationale, Capacity, and Future Directions.” The Patient - Patient-Centered Outcomes Research, vol. 14, (2021): 699–710, doi.org/10.1007/s40271-021-00515-1.

O’Rorke, Michael, Elizabeth Chrischilles, and the NET-PRO Study Investigators. “Making Progress Against Rare Cancers: a Case Study on Neuroendocrine Tumors.” Cancer, vol. 130, no. 9 (2024): 1568–1574, doi.org/10.1002/cncr.35184.

Pinsoneault, Laura T., Emily R. Connors, Elizabeth A. Jacobs, and Jerica Broeckling. “Go Slow to Go Fast: Successful Engagement Strategies for Patient-Centered, Multi-Site Research, Involving Academic and Community-Based Organizations.” Journal of General Internal Medicine, vol. 34, (2018): 125–131, doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4701-6.

Rawl, Susan M, Sandra Bailey, Beatrice Cork, et al. “Partnering to Increase Colorectal Cancer Screening: Perspectives of Community Advisory Board Members.” Western Journal of Nursing Research, vol. 43, no. 10 (2021): 930–938, doi.org/10.1177/0193945921993174.

Schmidt, Megan E., Jeanette M. Daly, Yinghui Xu, and Barcey T. Levy. “Improving Iowa Research Network Patient Recruitment for an Advance Care Planning Study.” Journal of Primary Care & Community Health, vol. 12, (2021): 1–6, doi.org/10.1177/21501327211009699.

Sgro, Gina M., Maureen Mauer, Beth Nguyen, and Joanna E. Siegel. “Return of Aggregate Results to Study Participants: Facilitators, Barriers, and Recommendations.” Contemporary Clinical Trials Communications, vol. 33 (2023):1–6, doi.org/10.1016/j.conctc.2023.101136.

Sugarman, Olivia K., Ashley Wennerstrom, Miranda Pollock, et al. “Engaging LGBTQ Communities in Community-Partnered Participatory Research: Lessons from the Resilience Against Depression Disparities Study.” Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, vol. 15, no. 1 (2021): 65–74, doi.org/10.1353/cpr.2021.0006.

Tolley, Elizabeth A., Satya Surbhi, and James E. Bailey. “Using Preliminary Data and Prospective Power Analyses for Mid-Stream Revision of Projected Group and Subgroup Sizes in Pragmatic Patient-Centered Outcomes Research.” Data in Brief, vol. 33, (2020): 1–9, doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2020.106529.

UNC Chapel Hill HCV Patient Engagement Group, Scott Kixmiller, Anquenette P. Sloan, et al. “Experiences of an HCV Patient Engagement Group: a Seven-Year Journey.” Research Involvement and Engagement, vol. 7, no. 7 (2021): 1–11, doi.org/10.1186/s40900-021-00249-2.

Van Eeghen, Constance, Juvena R. Hitt, Douglas J. Pomeroy, et al. “Co-Creating the Patient Partner Guide by a Multiple Chronic Conditions Team of Patients, Clinicians, and Researchers: Observational Report.” Journal of Internal Medicine, vol. 37, (2022): 73–79, doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-07308-0.

Young, Heather M., Sheridan Miyamoto, Stuart Henderson, et al. “Meaningful Engagement of Patient Advisors in Research: Towards Mutually Beneficial Relationships.” Western Journal of Nursing Research, vol. 43, no. 10 (2021): 905–914, doi.org/10.1177/0193945920983332.

Zhou, Yizhao, Jiasheng Shi, Ronen Stein, et al. “Missing Data Matter: an Empirical Evaluation of the Impacts of Missing EHR Data in Comparative Effectiveness Research.” Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, vol. 30, no. 7 (2023): 1246–1256, doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocad066.

Appendix II: Examples of ASPE Projects and Reports on Building Data Capacity for Comparative Clinical Effectiveness Research

The Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) supported multiple projects and reports aimed at building data capacity for conducting comparative clinical effectiveness research, including in the areas of

· Maternal health. In 2021, ASPE created the Maternal Health Consortium to facilitate collaboration for projects across agencies within the Department of Health and Human Services. These projects are designed to improve electronic health record data for comparative clinical effectiveness research on maternal health. For example, in 2023, ASPE issued a set of guiding principles for linking state Medicaid data with birth certificates, which if implemented could be used to create a multistate database for research on maternal health.

· Intellectual and developmental disabilities. In 2021, ASPE issued a report describing the current state of federal data available for conducting comparative clinical effectiveness research related to intellectual and developmental disabilities. In 2023, ASPE identified individual‑level outcome measures that could be used for conducting comparative clinical effectiveness research relevant to adults with disabilities, aged 18 to 64 years.

· Cancer. In 2023, ASPE funded one new project to link cancer registries and electronic health record data with the aim of developing a database to study cancer outcomes.

· Economic outcomes. In 2021, ASPE assessed the current landscape of federally funded data that contains health care costs, such as insurance payment for medical services or unpaid caregiving. This assessment identified opportunities to improve available data to study economic outcomes when conducting comparative clinical effectiveness research. In 2022, ASPE identified federally funded data that may facilitate the study of economic outcomes for Medicare fee-for-services beneficiaries.

Appendix III: Financial Information on PCORI and HHS Funding from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Trust Fund

Tables 5 and 6 provide financial information on activities funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) for the fiscal years 2019 through 2024 from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Trust Fund.

Table 5: PCORI Award Obligations from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Trust Fund, Fiscal Years 2019–2024

|

Dollars in millions |

|||||||

|

|

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

2024 |

Total |

|

Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) |

|||||||

|

Research Awards |

$148 |