HIGHLIGHTS OF A FORUM

Reducing Spending and Enhancing Value in the U.S. Health Care System

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO-25-107465. For more information, contact Jessica Farb at FarbJ@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107465, a summary of a GAO Forum

Reducing Spending and Enhancing Value in the U.S. Health Care System

Why GAO Convened This Forum

For many years, GAO has raised the alarm about the federal government being on an unsustainable long-term fiscal path. One of the key drivers of federal debt is spending on federal health programs, such as Medicare and Medicaid. Spending on federal health programs is projected to increase at a faster rate than the gross domestic product (GDP) over the next 30 years. As the population ages and health care costs increase, GAO projects that federal spending on health care programs will be 8.5 percent of the GDP in 30 years. Efforts to contain these costs have been met with mixed success.

On October 22, 2024, GAO convened a diverse panel of 30 health care experts to focus on the challenges of health care spending. The purpose of the panel was to help advance the dialogue and identify issues associated with one of the most perplexing problems facing the government. It comprised federal government officials, academics, researchers, clinicians, and industry experts who represented a range of expertise and experiences. Participants discussed approaches to reduce health care spending and enhance value received for that spending, among other things.

The viewpoints summarized in the report do not necessarily represent the views of all participants, their affiliated organizations, or GAO. GAO provided participants the opportunity to review a draft of this summary. Their comments were incorporated as appropriate.

What Participants Discussed

During the forum, participants identified approaches in five key areas that could help reduce health care spending or increase the value for that spending (see figure).

Supporting a high-functioning primary care system by providing more resources for team-based care through a payment model that combines fee-for-service payment with a fixed amount paid to providers regardless of the services provided. This could improve continuity of care and care coordination and help decrease unnecessary services and inappropriate tests.

Expanding the health care workforce by increasing the graduate medical education opportunities to help address shortages and the uneven distribution of physicians across the country. Increasing compensation and other benefits could also attract and retain home health workers and nursing assistants. Expanding the workforce could increase access to care and reduce the need for costly services, such as institutional care (hospitalization or nursing home care).

Reforming health care pricing and promoting high-value care by adopting pricing strategies used by other countries particularly in cases where prices for medical services and pharmaceuticals exceed their clinical value.

Reforming Medicare physician payments by revising the Medicare physician fee schedule particularly in cases where it may incentivize physicians to provide specialty care services (e.g., diagnostic imaging) over primary care services (e.g., clinical diagnosis), or to provide more services than are necessary.

Mitigating anticompetitive incentives and practices by implementing entirely site-neutral payments in Medicare, wherein Medicare pays the same rate for a medical service regardless of the site where it is performed. This could reduce the incentives for hospitals and physician practices to consolidate.

Participants agreed that legislative action, federal investment, or both would be needed to implement most of the approaches discussed.

Abbreviations

|

CMS |

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services |

|

GDP |

gross domestic product |

|

GME |

graduate medical education |

|

MIPS |

Merit-Based Incentive Payment System |

|

OECD |

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Cover image source: Brian Jackson/stock.adobe.com.

Introduction

For many years, we have raised the alarm about the federal government being on an unsustainable long-term fiscal path. That trajectory has accelerated in recent years. Debt held by the public reached $28.2 trillion as of the end of fiscal year 2024, or 98 percent of our country’s fiscal year 2024 gross domestic product (GDP). In February 2025, we projected that by 2047, debt held by the public will reach 200 percent of the U.S. GDP.[1]

One of the key drivers of our federal debt is spending on federal health programs, such as Medicare, Medicaid, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program. (CHIP). These programs supported about 147 million people in 2024. Spending on federal health programs made up about 31 percent ($1.8 trillion) of all federal program spending in fiscal year 2024 and is projected to increase at a faster rate than GDP over the next 30 years.[2] As the population ages and health care costs increase, we project that federal spending on health care programs will be 8.5 percent of GDP in 30 years (up from 5.8 percent in 2023).[3] Given current revenue projections, federal health care spending will be a key driver of future budget deficits (along with social security spending and interest payments).

Spending growth is not limited to just federal health programs. For example, national total spending on private health insurance is also projected to grow faster than the economy. From 2023 through 2032, per enrollee spending on private health insurance is projected to increase from $6,838 to $10,576, an increase of 54.7 percent.[4] During the same time period, GDP per capita is projected to increase by 35.8 percent.[5]

This growth in federal health care and private health insurance spending generally has not resulted in a commensurate improvement in health outcomes. For example, health care spending per capita is higher in the United States than in other high-income countries, yet people living in the U.S. have lower life expectancies, higher death rates for avoidable or treatable conditions, and higher maternal and infant mortality when compared to these other countries.

As we reported in 2021, chronic health conditions, such as cardiovascular diseases and obesity, impose a high burden on federal, state, and private sector health care spending and contribute to escalating costs.[6] According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, many chronic health conditions are preventable, yet they are leading causes of death and disability in the U.S. Poor diet is recognized as a prominent risk factor for developing a chronic health condition, alongside insufficient physical activity and a range of other important factors. In the December 2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, the U.S. Departments of Agriculture and Health and Human Services stated that diet is related to chronic health conditions, including cardiovascular diseases, cancer, diabetes, and obesity.

Over 20 years ago, we convened a Comptroller General’s Forum to highlight and identify ways to address health care cost, access, and quality challenges.[7] While some progress has been made since then, such as a decrease in the number of uninsured individuals and an increase in value-based payment programs, many of the same challenges remain. These include the unsustainability of rising health care costs, lack of access to care for many Americans, and variation in quality of care across the country. Additionally, many federal health care programs including Medicare, Medicaid, and veterans’ health care are among those we consider to be at highest risk for fraud, waste, abuse, and mismanagement or in need of transformation.[8]

More recently, we convened a diverse panel of health care experts on October 22, 2024, to focus on the persistent challenges of health care spending and opportunities to reduce health care spending and obtain better value for that spending.[9] With assistance from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, we selected 30 participants representing a range of backgrounds covering federal agencies, academics, researchers, clinicians, and industry experts across geographical areas with experience working with or representing patients, payers, or providers. We also selected participants for their knowledge of health care spending and outcomes, and experience navigating the health care delivery system. (See appendix I for a list of forum participants and their affiliations, and appendix II for a copy of the forum agenda.)

Forum participants discussed the following:

1. current and emerging health care spending trends and drivers;

2. the link between addressing the social determinants of health and reducing health care spending; and

3. approaches to reduce health care spending and/or enhance the value received for that spending.

Our report highlights themes and ideas that emerged during the proceedings. The information and viewpoints summarized here do not necessarily represent the views of all participants, the views of their organizations, or the views of GAO. We structured the forum so that participants could freely comment on issues, although not all participants commented on all topics. To ensure the accuracy of our summary, we provided the participants an opportunity to comment on a draft of this report prior to its publication.

We conducted our work from March 2024 to June 2025 and in accordance with all sections of GAO’s Quality Assurance Framework that are relevant to our objectives. The framework requires that we plan and perform the work to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to meet our stated objectives and to discuss any limitations in our work. We believe that the information obtained, and the analysis conducted, provide a reasonable basis for any findings and conclusions in this report.

I wish to thank all the participants for their thoughtful contributions to our discussion of health care spending in the U.S. The discussion among experts in the field, those who engage in these issues daily across multiple disciplines, in private and public roles provided invaluable suggestions for ways to continue making progress on this persistent problem.

Sincerely,

Gene L. Dodaro

Comptroller General of the United States

U.S. Health Care Spending Trends, Drivers, and Areas for Improvement

In the opening session of the forum, Dr. Mark McClellan presented a broad overview of current and emerging spending trends and drivers, and ways to reduce spending and improve value. Participants discussed and expanded on some of these areas for improvement throughout the forum.

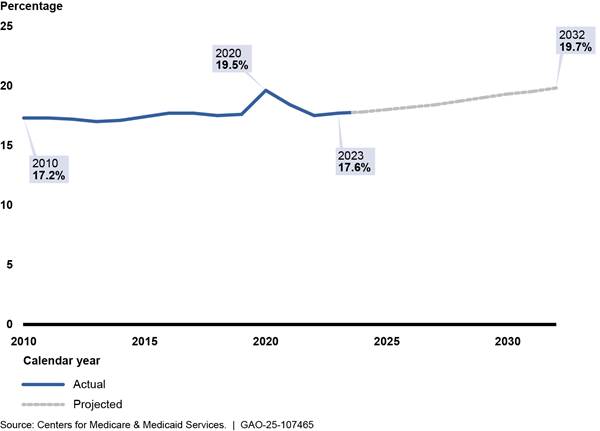

Dr. McClellan highlighted the U.S.’s decades-long disparity of higher per capita health expenditures and worse health outcomes compared to other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries. For example, he presented data showing that the U.S. has a lower life expectancy and lower health system performance, which includes measures of access to care, administrative efficiency, and equity.[10] Additionally, the data he presented show that while U.S. health expenditures have accounted for about 17 percent of GDP in recent years—outside of an increase in 2020 due to COVID-19 and the associated economic downturn—the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) projects that they will account for almost 20 percent of GDP by 2032.[11] See figure 1.

Figure 1: Actual and Projected U.S. Health Expenditures as a Percentage of Gross Domestic Product, 2010-2032

Dr. McClellan and participants discussed some of the current spending drivers. He said compared with almost every other sector, health care continues to be a more labor-intensive industry. The combination of using a lot of highly trained, highly paid physicians and nurses along with chronic shortages in this workforce creates significant cost pressure in the health care sector. These workforce shortages are expected to continue. Some participants agreed that high prices for services in the U.S. are also a key driver of health care spending. One participant noted that differences in the utilization of health care services between the U.S. and other high-income countries are relatively small, but the underlying unit prices of these services are much higher in the U.S.

Dr. McClellan said different drivers will likely continue to emerge in the 2020s. Some of these include an increased use of expensive new therapies that could impact the course of certain diseases such as anti-obesity medications and curative cell and gene therapies. Other future drivers could include increased use of advanced diagnostics to identify risk factors for diseases much earlier and the development of better-targeted interventions enabled by artificial intelligence. The use of artificial intelligence could also lead to increases in labor productivity and shifts to less labor-intensive care models. The effect these drivers will have on health care spending—either increasing or decreasing spending—will be influenced by health care policy decisions. Dr. McClellan said he hopes there will be a richer, more interoperable data infrastructure to determine what is working.[12]

Dr. McClellan detailed some of these health care policy decisions and areas for improvement that could help reduce health care spending and improve value.[13] However, he said opportunities to improve value may not always reduce costs.

|

“The thing about health care…is that…there are a lot of opportunities to increase value that may not reduce costs. And I put effective treatments for unmet needs at the top of that list. In other industries you see innovation leading to cost reductions. But typically, the innovation there is not doing as many new things. You know, [for example] unprecedented ways of treating previously untreatable conditions as we've seen in health care.” |

Source: Dr. Mark McClellan. | GAO‑25‑107465

Dr. McClellan and participants agreed that Congressional support and legislative action would be needed for most reforms.

Prevention and treatment. Dr. McClellan discussed how improving prevention and treatment can increase the value received from health care spending. He said there are opportunities for improvement throughout the treatment process. These include earlier and more accurate diagnoses so that interventions can start sooner and more effective treatments for disease interception and cure. There are also opportunities for more supportive care for patients with diseases that do not have a cure or effective treatment.

Dr. McClellan said there is a need to better target and scale effective treatments to reduce the growth of health care spending over time. He provided two examples of potential treatments that, if targeted appropriately, may reduce spending. See table 1.

|

Treatment for Hepatitis C |

According to a study conducted by the Congressional Budget Office, a 5-year program to expand diagnosis and management of hepatitis C among Medicaid enrollees could reduce costs over 10 years.a Specifically, a 10 percent increase in the treatment rate among Medicaid beneficiaries could save about $0.7 billion between 2025 and 2034. A 100 percent increase in the treatment rate could save $7 billion over that period. Most of those savings would accumulate towards the end of the 10 years, as treatment costs will be incurred over the early years. However, according to Dr. McClellan, to change treatment rates, care delivery must change. Specifically, providers need to treat people who currently do not engage with a regular source of care, such as a primary care provider. This would require strong primary care or care delivery in hard-to-reach communities. |

|

Anti-obesity medications |

Dr. McClellan said with newer anti‑obesity medications on the market, the hope is that preventing complications associated with obesity and chronic inflammation, including cardiometabolic syndrome, diabetes, cancer, heart disease, and kidney disease, would save money. But according to Dr. McClellan, current prices for these drugs in the U.S. are still relatively high compared to other countries. Additionally, he said the traditional health care system—which is fragmented and relies on fee-for-service care models—may not have reliable diagnostic information or adequate care coordination in health care delivery to target these medications to the people who would benefit the most. Additionally, the Congressional Budget Office estimated that authorizing coverage of anti-obesity medications in Medicare would increase federal spending, on net, by about $35 billion from 2026 to 2034. However, it also said the budgetary effects of authorizing anti-obesity coverage in Medicare are uncertain because the estimates of costs and take-up rates are sensitive to the evolving evidence on the eligibility, use, price, and clinical benefits associated with those medications.b |

Source: Dr. Mark McClellan. | GAO‑25‑107465

aThe Congressional Budget Office’s analysis focused on two sample national policies that would increase treatment rates among Medicaid enrollees and thereby affect federal spending on health care. Specifically, it analyzed two illustrative 5-year programs in which treatment rates would peak at increases of 10 percent and 100 percent above the current treatment rate among Medicaid enrollees. The Congressional Budget Office indicated that it focused on the Medicaid population because people at high risk for hepatitis C (including injection drug users and people who have been involved with the criminal justice system) are likely to be Medicaid beneficiaries, either at the time of treatment or in the future. See Congressional Budget Office, Budgetary Effects of Policies That Would Increase Hepatitis C Treatment (June 2024).

bSee Congressional Budget Office, How Would Authorizing Medicare to Cover Anti-Obesity Medications Affect the Federal Budget? (October 2024).

One participant also discussed the need for more innovative approaches in health care delivery to improve treatment. For example, there are many new drugs that are given intravenously. These drugs could be lifesaving, but primary care doctors typically do not have a process for providing these drugs in their office, so they are not used often, the participant said.

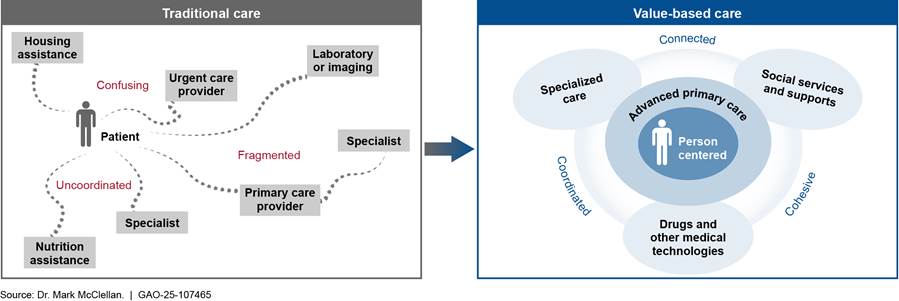

Care models. Dr. McClellan emphasized the importance of shifting away from fragmented fee-for-service models and towards value-based care models as a means of reducing health care spending and improving value.[14] He discussed how value-based care models are more person-centered, and can increase quality of care, improve health care outcomes, and reduce health care costs. In contrast to traditional fee-for-service models, value-based care models could incentivize less fragmentation and greater care coordination. See figure 2.

However, according to Dr. McClellan, there are several obstacles to getting to value-based care. For example, obstacles include the need for upfront capital investments to build the infrastructure necessary for a provider to effectively participate in a model, better and more interoperable data systems, and a workforce with different skill sets, including specialty care that works better with primary care. Additionally, Dr. McClellan cited a CMS report on care delivery models that concluded that strong primary care is a necessary foundation for value-based care models.[15]

Risk adjustment. Dr. McClellan and participants discussed how using fee-for-service claims data as the basis for doing risk adjustment for Medicare Advantage beneficiaries does not support a health care system that incentivizes high-value, whole-person care and improved health outcomes. Risk adjustment is the process for calculating how much to pay a health plan based on a patient’s health, their likely use of health care services, and the costs of those services. According to Dr. McClellan, using fee-for-service claims data to help determine risk adjustment payment amounts can overstate costs and increase program spending because these claims disproportionately represent higher and more costly users of services and therefore may not represent the typical beneficiary or their costs.[16] However, one participant said using fee-for-service claims data as the basis for doing risk adjustment in Medicare Advantage could actually reward Medicare Advantage plans that provide efficient care.

Dr. McClellan said CMS should use objective measures such as those that demonstrate disease progression and/or a patient’s risk for certain diagnoses (e.g., for chronic kidney disease this would include laboratory tests and kidney function tests) as a basis for risk adjustment. He noted that the use of electronic health records (which were less commonly used 20 years ago when the risk adjustment system was developed) could provide a basis for updating risk adjustment information. One participant said CMS could also include person- and household level socioeconomic data in addition to these clinical data when updating risk adjustment information. Some participants cautioned that, as additional data sources are used, safeguards should be put in place to protect the integrity of the risk adjustment system.

Productivity. Dr. McClellan and participants also discussed the need to increase productivity in health care. Dr. McClellan said digital health and artificial intelligence have the potential for transformative impacts on health care productivity. For example, new technologies could help reduce workforce administrative burdens; improve operations (e.g., ambient listening as a means for generating clinical documentation, support for coordinated team care); and improve triage, diagnosis, and treatment plans. One participant said physicians and nurses spend 35 to 50 percent of their time on things they could either stop doing or that could be automated. Another participant agreed that there are no incentives for productivity-enhancing innovation. This participant said the delivery of health care is dominated by large firms and once a firm gets in a dominant position, the firm wants to maintain and reap the benefits of that position, but it is not motivated to innovate.

Market competition. There was agreement among Dr. McClellan and participants that improving market competition could help reduce health care spending. Dr. McClellan said the U.S. has highly concentrated hospital markets that result in higher prices and fewer incentives for moving to value-based care. There are also continuing pressures to consolidate. For example, among other things, opportunities for economies of scale increase pressures for cross-market consolidation (i.e., consolidation between two providers that operate in different geographic markets for patient care). Similarly, opportunities for care coordination and integration increase pressures for vertical consolidation (i.e., consolidation between entities that offer different services along the same supply chain, such as when a hospital acquires a physician practice). Despite purported benefits of consolidation, one participant said evidence does not support claims of efficiencies from consolidation.[17] Dr. McClellan also said there is no evidence that consolidation leads to higher quality care and there are no clear benefits in terms of care coordination.

Dr. McClellan said current antitrust policies have not been able to mitigate increased provider consolidation. Although more aggressive policies could mitigate or stop consolidation, achieving efficiencies of scale and coordinated care while encouraging competition is still a worthwhile pursuit. He cited a research paper that presented some policies that could improve health care market competition including:[18]

· Having data interoperability enhancements, alongside substantial penalties for “data blocking”—practices that interfere with access, exchange, or use of a patient’s electronic health information; and

· Encouraging greater price and quality transparency for consumers and payers.

Some participants also noted that incremental price regulation for health care services could help address the higher prices resulting from increased consolidation.

Keynote on Addressing the Social Determinants of Health to Help Reduce Health Care Spending and Enhance Value

In her keynote presentation, Dr. Kara Odom Walker discussed the link between addressing the social determinants of health—such as food insecurity and lack of education—and reducing health care spending in the U.S. According to Dr. Walker, the social determinants of health have been shown to have an outsized effect on long-term health outcomes. For example, Dr. Walker said studies have found that only 10 percent of premature deaths can be attributed to deficiencies in the health care services patients receive, while 60 percent can be attributed to behavioral, social, and environmental factors.[19] Therefore, programs that address the social determinants of health may decrease health care spending over an individual’s lifespan, Dr. Walker said. As previously noted, the United States spends a large share of its GDP on health care. However, Dr. Walker pointed out that, compared to other nations in the OECD, the United States’ overall spending on public, non-health social programs as a share of GDP is low.[20]

Dr. Walker also highlighted the role that the social determinants of health play in creating inequities in health (i.e., differences in the opportunities that groups of people have to achieve optimal health). For example, she presented research showing that, compared to children with regular access to food, those with food insecurity have increased chances of health risks such as fair or poor health, developmental delays, colds, headaches, and stomach aches. Dr. Walker said that the health care sector began to address some of these inequities during the COVID-19 public health emergency through things like increased use of telehealth and a focus on primary care and prevention efforts (e.g., vaccination outreach efforts). She concluded that improving access and addressing health inequities is an area the health care sector needs to continue to embrace.

|

“We can have a conversation about how the money that we do spend on health care can be spent more wisely, but if you're serious from a governmental or a societal perspective about trying to get us a healthier population and lower demands on the health care system, the answer lies outside of health care. It has to do with the social drivers. It has to deal with the drivers of health inequities…and it has to do with social policies. That's what other countries have figured out. They spend more on social programs than they do on health care. Lacking that, I think we'll just be tinkering around the edges.” |

Source: Forum participant. | GAO‑25‑107465

To help address the social determinants of health and their effects on spending and equity, Dr. Walker advocated for health care delivery models with a more holistic, person-centered view of health that addresses social needs. Such models would focus on issues like housing, transportation, education, and food security along with traditional health care services. According to Dr. Walker, this sort of delivery model requires flexible funds to pay for programs addressing social needs and elements of value-based payment.

|

“As we do our work and we produce solutions, one of the things that we find is that when you cater your system design to those with the greatest need and the least trust, you end up with solutions that are not specific to that population at all. It turns out the solutions are just what human beings want from health care. It's this very old concept of universal design.” |

Source: Forum participant. | GAO‑25‑107465

Dr. Walker and participants discussed various considerations related to reducing health care spending and improving health equity by addressing the social determinants of health. The following is a summary of those discussions.

Investing in children’s health. Participants generally agreed that allocating additional resources to address the health and social needs of children could create a healthier generation of adults and generate possible savings in the long run. Dr. Walker said about 7 percent of total health care spending in the U.S. goes towards children. She spoke about reasons to focus on children, such as how food insecurity and a lack of education contribute to negative long-term health outcomes and how substance use is starting earlier in children’s lives. According to Dr. Walker, there are several existing and efficacious federal levers to address social inequities such as the Federal Earned Income Tax Credit, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), and Child Tax Credits.[21] Dr. Walker also explained how the COVID-19 public health emergency response illustrated different ways of addressing children’s health and social needs that could be elevated and scaled up. For example, she said that during the COVID-19 public health emergency, officials in Massachusetts, North Carolina, and Washington built health care delivery models to address social needs that relied on collaboration across leaders in multiple sectors, built on momentum from broader health care transformation efforts in the states. These efforts leveraged public and philanthropic funding sources in addition to federal policy opportunities to innovate such as Medicaid Section 1115 waivers and State Innovation Model grants.[22]

Building trust and connections. Participants generally agreed that when providers build trust and connection with the communities they serve, it helps give individuals more equitable access to the care they need, including social and preventive services that reduce future health care costs. Several participants highlighted difficulties that patients face when navigating the health care and social services systems, such as the time and administrative burden required to find and apply for benefits. Even if services are available for patients with social needs, participants spoke about how patients can have a lack of trust in or even a profound fear of the health care system that prevents them from fully engaging with it to meet their needs. Participants suggested that navigators could help patients locate and access the social services they need outside of health care more efficiently.[23]

Dr. Walker and participants discussed how health care providers may not be the best choice to act as navigators because they are not experts across all sectors and having them do so could increase their administrative burden. Instead, navigators could be made up of individuals who specialize in the entire spectrum of available care and services such as social workers or community health workers. However, one participant pointed out that it could be a challenge to get trusted navigators for people from communities with limited interactions with the health care system. Dr. Walker said technology could also help improve accessibility and reduce the burden of finding and connecting with needed social services. In addition, participants said primary care could offer a potential touchpoint to connect people with social services.

Identifying funding sources. Dr. Walker and participants agreed that ideally the funding stream for programs to address the social determinants of health should fall outside of health care funding, even though these social factors affect people’s health. However, one participant noted that since social program funding is low outside of health care, partnerships and connections with health care sources can help fill some of these funding gaps.

|

“If someone does not come into contact with the health care system, a health care-based model for addressing social determinants will not be effective.” |

Source: Forum participant. | GAO‑25‑107465

Dr. Walker and participants discussed how some state Medicaid and private programs like Nemours Children’s Health—where Dr. Walker is Executive Vice President & Chief Population Health Officer—have leveraged pilot and demonstration funding to pull resources in from sectors beyond health care to address the social determinants of health and improve health outcomes.[24] Having flexible funds, not driven by fee-for-service payment, can allow health care systems to put those dollars into activities that do not generate revenue but can reduce health inequities and improve quality and longer-term health outcomes. The following are examples Dr. Walker and participants mentioned that illustrate how state Medicaid programs have used Section 1115 waiver flexibilities to build up approaches to address social determinants of health:

· Massachusetts Medicaid created a pool of funding to help pay for social services. Physicians can refer patients to community-based organizations to receive social services using this funding.

· North Carolina’s Healthy Opportunities Pilots have a pool of funding to test and evaluate the impact of providing evidence-based, non-medical interventions related to housing, food, transportation, interpersonal safety, and toxic stress to high-need Medicaid enrollees. Without Section 1115 waiver funding, some participants said the Medicaid program would not have been able to buy their data system and support their work with under-resourced community-based organizations.

· Oregon Medicaid is partnering with local communities to fund health equity coalitions made up of community members and representatives. The coalitions work to identify and address the most pressing health equity issues in their region and develop equity dashboards, incentives, and metrics to improve language access and social needs screening for disadvantaged populations. Oregon collects large amounts of data on Medicaid beneficiaries, which are used to assist with screening referrals.

|

Department of Veterans Affairs Delivers Person-Centered Care Multiple participants cited the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) as a federally funded system that delivers quality care at a low cost and may provide some lessons learned for other health care systems. For example, one participant said the VA screens the veterans it treats for some social determinants of health, including housing and food insecurity. Another participant pointed to David C. Chan, David Card, and Lowell Taylor’s 2023 essay that stated VA provided higher-quality and lower-cost care compared to private hospitals (“Is There a VA Advantage? Evidence from Dually Eligible Veterans,” American Economic Review 113 (11): 3003-43). The authors found that continuity of care, health information technology, and integrated care complement each other in VA health services to provide person-centered care. Veterans have larger survival gains when receiving VA care compared to those who transition to non-VA care, according to the report. Source: GAO summary of forum discussion. | GAO‑25‑107465 |

Collecting better data. Dr. Walker and participants discussed how the availability of demographic and other social determinants of health data varies across jurisdictions, payers, and providers. They noted that this situation can make targeting interventions more challenging. States often collect different types of data, which makes it challenging or impossible to make comparisons across states. In addition, participants discussed how data systems need to be updated to accommodate additional data as it becomes available, even though these updates require up-front investment. For example, linking administrative data such as data on absenteeism and school performance to health records, both within and across states, would make it easier to tackle health inequities jointly and more comprehensively. Better data can help target resources more effectively, although additional research is needed to determine which interventions are the most effective and efficient.[25]

Reducing Spending and Enhancing Value in the U.S. Health Care System

Following the forum’s opening and keynote sessions,

participants attended one of four breakout sessions. In these sessions,

participants identified five key areas to help reduce health care spending and

improve value received from that spending.[26]

In some cases, these conversations echoed the conversations during the opening

and keynote sessions.

Supporting a High-Functioning Primary Care System

Participants discussed how supporting a high-functioning primary care system is important to reducing costs and improving value. One participant noted that primary care encourages continuity of care and care coordination, and having this type of care as the first access point for patients can help decrease unnecessary services and inappropriate tests. One participant also pointed to a 2021 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine report showing that primary care is the only health care component where increased supply is associated with better health and equitable outcomes.[27] However, some participants agreed that primary care is under-resourced relative to the share of visits it receives compared to specialty care, and the proportion of total health care spending going towards primary care is declining.

Participants discussed how using hybrid payment models for primary care and implementing team-based care can lead to better patient outcomes and enhance the value of care.

Hybrid payment models. Several participants agreed using a hybrid payment model for primary care—which incentivizes cost-effective, patient-centered care through a combination of capitated and fee-for-service payments—can lead to better outcomes.[28] Participants discussed how while traditional fee-for-service payment models may incentivize physicians to provide more services, even if they are unnecessary, the fee-for-service component of a hybrid payment model could help create incentives for primary care providers to deliver services that would be more cost-effective than having a specialist deliver them. These services could include basic skin biopsies, hypertension management, and depression screening.

Participants discussed how, if set up correctly, using hybrid payment models for primary care can work in larger health systems as well as in small independent practices, where a capitated payment may be seen as a risk. However, one participant who has experience with these models said health plans and providers would need to invest in payment infrastructure that would work for the hybrid payment model. Currently, many health plans’ claims operations are built around fee-for-service claims. Many providers also do not have the billing tools to be paid in a hybrid way so they would not be able to track and manage their payments, one participant said.

Additionally, participants discussed how payment reform requires collaboration among states, hospitals, and primary care providers, as well as accountability at the hospital level. One participant said that hospitals get paid more when people are sicker. This participant likened this to a sickness center and said the incentives have to shift to those that keep people well. Another participant explained how the Maryland Total Cost of Care Model—which includes a hybrid payment component—helped push more care from hospital settings into primary care. It also provided an incentive to make sure health care providers are working together around chronic disease management and avoidable utilization—hospital care that is unplanned and can be prevented through improved care and care coordination, among other things.[29]

Implementing team-based care. Participants discussed how implementing team-based primary care, where every member of the team provides the full scope of care they are trained and authorized to perform, would allow for greater continuity of care and care coordination. It could also decrease the need for physicians and registered nurses to do administrative tasks that can be done by other staff and give them more time to focus on providing care to patients.

Reforming the payment model for primary care, as discussed above, would provide resources for more team-based care and could reduce the amount of time physicians spend on administrative tasks and referrals. For example, one participant said it would ensure there is payment for someone to answer the phone and respond to emails, as well as payment to have a behavioral health specialist or community health worker integrated into the primary care team.

Expanding the Health Care Workforce

Participants discussed ways to expand the health care workforce to reduce inadequacies in the supply of care including by investing in the primary care workforce, addressing workforce regulatory constraints and investing in the long-term care workforce. Participants also noted that some of the approaches would involve upfront investment that may yield long-term savings by, for example, reducing the need for high-priced services, such as institutional care (hospitalization or nursing home care).

Investing in the primary care workforce. Participants discussed how increasing compensation for primary care providers and increasing primary care training opportunities in communities with limited access to health care can help address challenges in the number and distribution of primary care physicians.

Specifically, participants discussed increasing compensation as an incentive to attract primary care physicians. One participant said many medical students are faced with high student debt and specialty care areas are more financially lucrative. Additionally, another participant noted that medical residents are choosing not to go into primary care, and primary care physicians are leaving the field.

Regarding community-based training, participants discussed creating opportunities to train more primary care physicians in teaching health centers and community hospitals, in line with community-based training recommendations from a National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine report on primary care.[30] Specifically, that report included a recommendation that the Department of Health and Human Services redesign its graduate medical education (GME) program to increase funding for primary care training in community settings and expand the distribution of training sites to better meet the needs of communities, with a focus on rural and underserved areas.[31]

Addressing workforce supply regulatory constraints. Participants discussed how relaxing certain workforce supply regulatory constraints may increase the supply of and access to health care providers. For example, they said supply can be increased without additional training by relaxing current regulations around health care professionals’ scope of practice—that is, the range of activities that health care professionals are trained and permitted to perform. One participant noted that relaxing requirements on who can prescribe medication may help with access challenges that result from shortages of primary care physicians and other specialties in rural areas.[32] While acknowledging potential patient safety concerns that some in the medical field have about relaxing some requirements, this participant said that there are few examples of bad actors. The participant said that there is a lot of attention paid to what might happen if things go wrong without recognizing the number of lives lost because access did not exist in the first place.

In addition, participants discussed increasing and reallocating physician GME slots to address overall shortages as well as the uneven geographical and specialty distribution of physicians. Physician GME training provides clinical education required for a physician to be eligible for licensure and board certification to practice medicine independently in the U.S.[33] The availability of this training plays a role in determining the composition and distribution of the physician workforce.[34] One participant said that increasing GME slots could help address supply shortages and physician burnout. Another participant said that because GME programs tend to focus on higher paying specialties, attention should be paid to allocating more slots to those going into primary care and practicing in rural areas.

Investing in the long-term care workforce. Participants discussed the need for increased investments in the long-term care workforce, including home health and personal care workers and certified nursing assistants. One participant said focusing on workforce development and retention for these positions, including increasing compensation, could attract more people and reduce turnover. This would require upfront investment but could yield long-term value by reducing costly institutional care and shifting it to community-based settings and patients’ homes. One participant said some states that have used loan forgiveness for long-term care workers practicing or training have achieved positive recruiting and retention rates. However, because Medicaid is the largest payer for facility-based and home health care, these strategies could lead to higher Medicaid costs, as wages and benefits for the long-term care workforce increase. Additionally, one participant said these jobs may still not be desirable even with payment increases.

Reforming Health Care Pricing and Promoting High-Value Health Care

Participants discussed the need to reform certain health care pricing strategies and better promote high-value health care. Specifically, participants discussed how pricing failures and incentives to use low-value care can contribute to increased health care spending.[35] They noted the need for reform in cases where prices for services and pharmaceuticals exceed their clinical value.

Reforming health care pricing. Participants discussed adopting strategies that other countries use to address pricing failures for certain medical services and pharmaceuticals. For example, the U.S. could adopt an all-payer price setting structure for tests such as MRIs and CT scans, which Australia and Canada use. Under this pricing approach, all payers (i.e., public and private insurers and individuals) pay the same single rate for a medical service. Participants also said the U.S. could build on efforts to negotiate prices with pharmaceutical companies.[36] Like Germany, France, and Canada, the U.S. could adopt pricing structures for pharmaceuticals that focus on the comparative effectiveness of drugs. Specifically, like these countries, the U.S. could set prices based on the clinical value of a drug compared to what is already on the market at that time.

Participants also discussed adjusting Medicare policy to address pricing failures. For example, one participant said that there might be some limited opportunities to address high prices for drugs paid for under Medicare Part B—an approach recommended by the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Specifically, they recommended using a common billing code to pay for the originator biologic drug and its biosimilars.[37] Such a policy would increase price competition between originators and biosimilars, resulting in lower costs for beneficiaries and the Medicare program.[38]

Better promotion of high-value care. Participants discussed the need for federal health care programs and private insurers to better promote high-value care to help reduce health care spending. For example, one participant talked about allowing the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services more flexibility in revisiting Medicare coverage determinations and in determining cost sharing for Medicare beneficiaries, making changes based on evidence of effectiveness.[39] This participant cited a Medicare Payment Advisory Commission study which estimated that between $2 and $6 billion in services were low value or unnecessary in 2022.[40] As such, this participant said revisiting the services covered and the cost sharing policies for certain services would provide opportunities to discourage use of low-value care and promote the use of services that are most likely to benefit the patient.

Another participant pointed out that private insurance is not always structured to promote high-value, whole-person care. Therefore, policies would be needed to encourage insurers to incorporate value when structuring their health benefits. This participant explained that it may be difficult for insurance companies to incorporate nonfinancial considerations, such as improved health, when designing their health benefits.

Reforming Medicare Physician Payments

Several participants emphasized the importance of reforming Medicare physician payment, including the Medicare physician fee schedule and the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS).[41] Changes in Medicare payment, they said, could also set the tone for other payers.

Revising the Medicare physician fee schedule. Several participants agreed that the Medicare physician fee schedule should be revised and simplified, particularly in cases where it incentivizes physicians to provide specialty care services over primary care services, or to provide more services than are necessary.[42] One participant said the fee schedule was intended to shift care from specialty care to primary care but achieved the opposite. Several participants said it is problematic that, in some cases, the Medicare physician fee schedule payment amounts favor procedural services (e.g., diagnostic tests and other surgical and non-surgical interventions) over cognitive services (e.g., office visits, clinical diagnoses).This can occur when the physician fee schedule codes for procedural services are not updated to reflect efficiencies gained over time, resulting in payment distortions that favor procedures at the expense of cognitive services.

Participants also discussed whether there is a need for additional data to determine the relative payments for Medicare-covered services. CMS typically adopts recommendations from the American Medical Association Specialty Society Relative Value Scale Update Committee—an expert panel that includes members from national physician specialty societies—when developing and updating the relative value estimates upon which the physician fees are based.[43] However, some participants said this committee has its shortcomings which include relying too heavily on the input from physician specialty societies when identifying misvalued services. These participants suggested that CMS use other data options to set the Medicare physician fee schedule in addition to or as an alternative to this committee.

One participant said that changing the entire fee schedule would be a major undertaking, but that targeted, incremental changes could be made. For example, this participant said that the fee schedule could be increased with an “add-on” payment specifically for physicians who treat disadvantaged populations, similar to the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission recommendation.[44]

Reforming MIPS. Participants discussed how MIPS—a value-based care payment system—has not achieved its intended goal of incentivizing physicians to provide high-quality, cost-efficient care, with some saying it should be eliminated.[45]

Participants discussed several concerns about this payment system that should be addressed. First, some participants said MIPS relies on quality measures that do not accurately capture the quality of physicians’ performance. For example, under MIPS, providers are able to choose the quality measures on which they will be evaluated. As a result, providers may choose quality measures that they are already doing well on rather than choosing measures for which they need to improve performance.

|

“I think what we have failed to do [with quality measures] is cut off the tail of poor quality, while we are having difficulty distinguishing different gradations of acceptable care and using financial incentives...I think we can measure a lot easier, and I think government [has] a primary responsibility to protect the public for safety and quality, rather than seeing its mission as moving the median, perhaps facilitating an improvement in the median, but pay for performance [in its current form] hasn't achieved that.” |

Source: Forum participant. | GAO‑25‑107465

In addition, the quality measures used do not necessarily align with patient health outcomes some participants said. They explained that even if a physician does well on their quality measures, that does not necessarily mean the patient has improved health. According to one participant, this is because much of the variation in health care outcomes is driven by social, non-clinical factors and the quality measures may be too simplistic to be meaningful to patient health outcomes. In addition, another participant said that MIPS does not have clinically relevant measures for all subspecialties or clinical conditions, such as for cardiologists performing procedures on patients with coronary artery disease or heart attacks. Several participants agreed that the quality measures for MIPS need to be more aligned with health outcomes and be relevant for more clinical conditions.

Some participants also said that physicians do not get timely, actionable data to identify care gaps for patients and avoidable costs that can be reduced. Specifically, they said MIPS performance data are not available until 18 months after the beginning of the year-long performance period. Therefore, MIPS participants are not able to make changes to their performance based on the data because, by the time they receive it, the performance period is already over.

Finally, participants raised concerns about the administrative burden that the reporting requirements for MIPS places on physicians given that the measures are not actually improving quality or able to be used by physicians. This added burden may lead to physician burnout and could impede patient access because physicians have less time to see patients.

Mitigating Anticompetitive Incentives and Practices

Participants agreed that the federal and state governments need to mitigate anticompetitive actions by payers, providers, and other actors in the health care space. Participants mentioned specifically that governments could 1) reduce incentives to consolidate, 2) carry out more antitrust enforcement, and 3) gather better data to mitigate anticompetitive actions that may lead to higher costs and lower quality care. These participants challenged the widely held belief that health care is fragmented and bad for patients, so consolidation leads to integration and coordinated care, which leads to better quality and lower prices. They agreed that the existing evidence disproves or finds this relationship to be inconclusive.[46] One participant said there needs to be a constellation of policies to mitigate anticompetitive actions.

Reducing incentives to consolidate. Participants discussed how they believe that one of the unintended consequences of Medicare payment policy and the 340B Drug Pricing Program is that they distort incentives, which can lead to more consolidation.[47] For example, Medicare pays a higher rate for certain medical services if they are provided in a hospital outpatient department rather than a physician’s office. According to participants, this difference in Medicare payment rates, based on where a service is performed, incentivizes a type of consolidation whereby hospitals acquire physician practices.[48] To address this, many participants said Medicare should have entirely site-neutral payments, whereby payments for services are the same regardless of whether a service is performed in a physician’s office or hospital outpatient department. In addition, participants said the 340B Drug Pricing Program may incentivize consolidation. Specifically, hospitals that qualify for the 340B Drug Pricing Program can acquire physician practices to increase referrals and expand capacity for outpatient drug administration. This discount would be captured by the combined hospital-physician practice.

Increasing antitrust enforcement. Participants discussed how the federal government could increase antitrust enforcement by lowering the reporting threshold for mergers and acquisitions. As of 2025, certain entities that merge are required to report to the Federal Trade Commission if the value of the transaction is above $126.4 million.[49] Lowering this threshold amount would make small transactions more visible and provide the Federal Trade Commission more opportunity for oversight to prevent anticompetitive mergers or business practices.

Participants also spoke about how state policies, or a lack thereof, can impede states and the federal government from monitoring anticompetitive behaviors, such as “most-favored nation” clauses.[50] One participant said states need to pass legislation increasing their ability to act early to limit anticompetitive behavior. For example, there are state requirements on notifying their oversight entities about closures for hospitals but not for vertical transactions, such as when a hospital system acquires an urgent care center in a geographic area where it already has a presence. This participant said the National Academy for State Health Policy developed model legislation to increase state oversight over all types of consolidation.[51]

Informing policy to address anticompetitive practices. Participants agreed it is important for policymakers to have more information about the effects of competition and concentration in health care. It is also important to give policymakers a better understanding of how ownership and consolidation affect quality of care and costs. However, this information may not be easy to find, participants noted. For example, participants discussed the lack of conclusive research examining the relationship between quality and ownership. One participant spoke about the need for research tying quality to financial transactions and oversight. This would allow for state and federal entities to be better informed in their roles as antitrust enforcers and purchasers of care for employees. Another participant proposed an approach akin to that of the Netherlands, wherein the state health authority can collect, hold, and analyze data on market transactions and look at how markets function and act. This would give state policymakers a better platform to target the development of evidence-based policies.

Policy Considerations

Consistent with the discussion at the Comptroller General Forum on Health Care held in 2004, the participants at our 2024 Forum raised concerns about high U.S. health care spending and the value received for that spending. Similar to 2004, the evidence shows that per capita health care spending in the U.S. is higher than in any other OECD country, yet the U.S. continues to lag behind the other OECD countries on measures of access to care, health equity, and certain health outcomes such as life expectancy. The important question remains: What can be done to address these persistent spending and value issues?

Across the forum sessions, participants discussed various approaches, many of which built on ideas proposed at the first forum. For example, participants discussed the need to better incentivize coordinated, cost-effective care, especially for people at greatest risk of negative health outcomes such as those with chronic conditions. The ideas generated frequently had evidence supporting their effectiveness, including our past work. (See Related GAO Products at the end of this report.) Several participants discussed, for example, how Medicare should have entirely site-neutral payments—payments for services are the same regardless of whether a service is performed in a physician’s office or hospital outpatient department.

Participants also discussed that the U.S. should dedicate resources to building the infrastructure necessary to support improving the value of health care. For example, participants discussed the importance of developing a more robust information infrastructure as a basis for many of the approaches—including interoperative data exchange and billing systems that are flexible enough to allow for evolving payment reforms, such as hybrid payment models for primary care and value-based care models, as well as reforming risk adjustment.

Participants also emphasized the need to dedicate resources—either health care dollars or resources outside the health care system—to address the social determinants of health and to better meet social needs, including food and housing security, and education.

Finally, participants agreed that lawmaker support at the state and federal level are needed to implement most of the approaches discussed. Additionally, participants noted that because investments are likely needed at the federal level, costs may increase in the short-term, but increasing investments in these areas can result in long-term savings and a higher value health care system.

The report is available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact Jessica Farb at farbj@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix III.

Jessica Farb

Managing Director, Health Care

|

Robert Berenson, MD |

Institute Fellow, The Urban Institute |

|

Rachel Block |

Program Officer, Milbank Memorial Fund |

|

Jonathan Cantor, PhD |

Policy Researcher and Professor of Policy Analysis, RAND |

|

Joel Cohen, PhD |

Director of the Center for Financing, Access, & Cost Trends, Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality |

|

Jennifer DeVoe, MD, PhD |

Professor and Chair of the Department of Family Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University |

|

Laura Fox, MPH |

Director of Payment Innovation, Blue Shield of California |

|

Martin Gaynor, PhD |

Lester A. Hamburg University Professor of Economics & Public Policy, Carnegie Mellon University |

|

Joshua Gottlieb, PhD |

Professor, University of Chicago Harris School of Public Policy |

|

Jennifer Hananoki, JD |

Assistant Director of Federal Affairs, American Medical Association |

|

Verlon Johnson, MPA |

Executive Vice President & Chief Strategy Officer, Acentra Health; Chair, Medicaid & CHIP Payment & Access Commission |

|

Eve Kerr, MD, MPH |

Division Chief of General Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan |

|

Jodi Liu, PhD, MSPH, MSE |

Senior Policy Researcher and Professor, RAND |

|

Paul Masi, MPP |

Executive Director, Medicare Payment Advisory Commission |

|

Mark McClellan, MD, PhD |

Director & Robert J. Margolis, MD Professor of Business, Medicine, & Policy, Duke-Margolis Institute for Health Policy at Duke University |

|

Joseph Newhouse, PhD |

Professor of Health Policy & Management, Harvard University |

|

Irene Papanicolas, PhD |

Director of the Center for Health System Sustainability & Professor of Health Services, Policy, & Practice, Brown University |

|

Hoangmai Pham, MD, MPH |

President & CEO, Institute for Exceptional Care |

|

Robert Phillips Jr., MD, MSPH |

Founding Executive Director of the Center for Professionalism & Value in Health Care, American Board of Family Medicine |

|

Peter Pronovost, MD, PhD, FCCM |

Chief Quality & Clinical Transformation Officer, University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center |

|

Robert Saunders, PhD |

Senior Research Director of Health Care Transformation, Duke-Margolis Institute for Health Policy at Duke University |

|

Richard Scheffler, PhD |

Distinguished Professor of Health Economics & Public Policy, University of California, Berkeley |

|

Kosali Simon, PhD |

Distinguished Professor, Indiana University O’Neill School of Public & Environmental Affairs |

|

Sheila Smith, MA |

Senior Economist, National Health Statistics Group, Office of the Actuary, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services |

|

Paul Spitalnic |

Chief Actuary, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services |

|

Hemi Tewarson, JD, MPH |

Executive Director, National Academy for State Health Policy |

|

Jeannette Thornton |

Executive Vice President of Policy & Strategy, AHIP |

|

Cori Uccello, MPP |

Senior Health Fellow, American Academy of Actuaries |

|

Kara Odom Walker, MD, MPH, MSHS |

Executive Vice President & Chief Population Health Officer, Nemours Children’s Health |

|

Chapin White, PhD, MPP |

Director of Health Analysis, Congressional Budget Office |

|

Steven Woolf, MD, MPH |

Professor of Family Medicine & Population, Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine |

GAO Contact

Jessica Farb, farbj@gao.gov.

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Gregory Giusto (Assistant Director), Kaitlin Dunn (Analyst-In-Charge), Benjamin Feldman, and Carmen Rivera-Lowitt made key contributions to this report. Also contributing were Jeff Arkin, John Dicken, Leslie Gordon, Joy Grossman, Michael Hoffman, David Jones, Emei Li, Kathleen McQueeney, Eric Peterson, Michelle Rosenberg, Jennifer Rudisill, Ravi Sharma, Frank Todisco, Walter Vance, and Cathleen Hamann Whitmore.

Inflation Reduction Act of 2022: Initial Implementation of Medicare Drug Pricing Provisions. GAO‑25‑106996. Washington, D.C.: April 28, 2025.

Private Health Insurance: Market Concentration Generally Increased from 2011 through 2022. GAO‑25‑107194. Washington, D.C.: November 14, 2024.

Health Care Transparency: CMS Needs More Information on Hospital Pricing Data Completeness and Accuracy. GAO‑25‑106995. Washington, D.C.: October 2, 2024.

Older Americans Act: Updated Information on Unmet Need for Services. GAO‑24‑107513. Washington, D.C.: May 17, 2024.

Maternal and Infant Health: HHS Should Strengthen Processes for Measuring Program Performance. GAO‑24‑106605. Washington, D.C.: March 27, 2024.

Medicare: Performance-Based and Geographic Adjustments to Physician Payments. GAO‑24‑107106. Washington, D.C.: October 19, 2023.

Homelessness: Actions to Help Better Address Older Adults’ Housing and Health Needs. GAO‑24‑106300. Washington, D.C.: September 9, 2024.

Electronic Health Information Exchange: Use Has Increased, but Is Lower for Small and Rural Providers. GAO‑23‑105540. Washington, D.C.: April 21, 2023.

Medicare: Information on Geographic Adjustments to Physician Payments for Physicians’ Time, Skills, and Effort. GAO‑22‑103876. Washington, D.C.: February 4, 2022

Medicare: Provider Performance and Experiences under the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System. GAO‑22‑104667. Washington, D.C.: October 1, 2021.

Medicare: Information on the Transition to Alternative Payment Models by Providers in Rural, Health Professional Shortage, or Underserved Areas. GAO‑22‑104618. Washington, D.C.: November 17, 2021.

Chronic Health Conditions: Federal Strategy Needed to Coordinate Diet-Related Efforts. GAO‑21‑593. Washington, D.C.: August 17, 2021.

Youth Homelessness: HUD and HHS Could Enhance Coordination to Better Support Communities. GAO‑21‑540. Washington, D.C.: September 30, 2021.

Physician Workforce: Caps on Medicare-Funded Graduate Medical Education at Teaching Hospitals. GAO‑21‑391. Washington, D.C.: May 21, 2021.

Prescription Drugs: U.S. Prices for Selected Brand Drugs Were Higher on Average than Prices in Australia, Canada, and France. GAO‑21‑282. Washington, D.C.: March 29, 2021.

Health Care Workforce: Views on Expanding Medicare Graduate Medical Education Funding to Nurse Practitioners and Physician Assistants. GAO‑20‑162. Washington, D.C.: December 18, 2019.

Medicaid: Efforts to Identify, Predict, or Manage High-Expenditure Beneficiaries. GAO‑19‑569. Washington, D.C.: August 13, 2019.

Physician Workforce: HHS Needs Better Information to Comprehensively Evaluate Graduate Medical Education Funding. GAO‑18‑240. Washington, D.C.: March 9, 2018.

Child Well-Being: Key Considerations for Policymakers, Including the Need for a Federal Cross-Agency Priority Goal. GAO‑18‑41SP. Washington, D.C.: November 9, 2017.

Physician Workforce: Locations and Types of Graduate Training Were Largely Unchanged, and Federal Efforts May Not Be Sufficient to Meet Needs. GAO‑17‑411. Washington, D.C.: May 25, 2017.

Elderly Housing: HUD Should Do More to Oversee Efforts to Link Residents to Services. GAO‑16‑758. Washington, D.C.: September 1, 2016.

Medicare: Increasing Hospital-Physician Consolidation Highlights Need for Payment Reform. GAO‑16‑189. Washington, D.C.: December 18, 2015.

Health Care Workforce: Comprehensive Planning by HHS Needed to Meet National Needs. GAO‑16‑17. Washington, D.C.: December 11, 2015.

Medicare: Physician Payment Rates Better Data and Greater Transparency Could Improve Accuracy. GAO‑15‑434. Washington, D.C.: May 21, 2015.

Medicare Advantage: CMS Should Improve the Accuracy of Risk Score Adjustments for Diagnostic Coding Practices. GAO‑12‑51. Washington, D.C.: January 12, 2012.

Highlights of a Forum: Health Care 20 Years From Now – Taking Steps Today to Meet Tomorrow’s Challenges. GAO‑07‑1155SP. Washington, D.C.: September 7, 2007.

Comptroller General’s Forum on Health Care: Unsustainable Trends Necessitate Comprehensive and Fundamental Reforms to Control Spending and Improve Value. GAO‑04‑793SP. Washington, D.C.: May 1, 2004.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]GAO, The Nation’s Fiscal Health: Strategy Needed as Debt Levels Accelerate, GAO‑25‑107714 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 5, 2025). These projections reflect fiscal and economic data as of December 2024.

[2]Program spending is total spending less net interest spending. It includes, among other areas, social security spending, health care spending, and spending related to national defense, veterans’ benefits, homeland security and transportation. See GAO‑25‑107714.

[4]See Jacqueline A. Fiore, et al., “National Health Expenditure Projections, 2023–32: Payer Trends Diverge as Pandemic-Related Policies Fade,” Health Affairs, vol. 43 no. 7 (2024). The estimate of total private health insurance accounts for premiums paid to traditional managed care plans, self-insured health plans and indemnity plans. This category also includes the net cost of private health insurance which is the difference between health premiums earned and benefits incurred.

[5]Fiore, et al., “National Health Expenditure Projections, 2023-32.”

[6]GAO, Chronic Health Conditions: Federal Strategy Needed to Coordinate Diet-Related Efforts, GAO‑21‑593 (Washington, D.C.: Aug. 17, 2021).

[7]GAO, Comptroller General’s Forum on Health Care: Unsustainable Trends Necessitate Comprehensive and Fundamental Reforms to Control Spending and Improve Value, GAO‑04‑793SP (Washington, D.C.: May 1, 2004).

[8]GAO, High-Risk Series: Heightened Attention Could Save Billions More and Improve Government Efficiency and Effectiveness, GAO‑25‑107743 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 25, 2025).

[9]For the purposes of this forum, participants considered value in terms of improving health care quality, access, equity, or some combination of the three.

[10]David Blumenthal et al., Mirror, Mirror 2024: A Portrait of the Failing U.S. Health System — Comparing Performance in 10 Nations (Commonwealth Fund: 2024); "Life Expectancy vs. Health Expenditures, 1970 to 2023,” (web page), Global Change Data Lab, accessed October 2024. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/life-expectancy-vs-health-expenditure.

[11]Fiore, et al., “National Health Expenditure Projections, 2023-32.”

[12]Interoperability refers to the ability of data collection systems to exchange information with and process information from other systems.

[13]For the purposes of this forum, participants considered value in terms of improving health care quality, access, equity, or some combination of the three.

[14]Fee-for-service models are those in which providers are reimbursed for each service they provide. Value-based care is health care that is designed to focus on quality of care, provider performance, and the patient experience.

[15]Elizabeth Fowler et al., "Accelerating Care Delivery Transformation – The CMS Innovation Center’s Role in the Next Decade," NEJM Catalyst, vol. 4, no. 11 (2023).

[16]In its March 2025 report, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission projected that Medicare’s payments to Medicare Advantage plans will be higher than those paid to fee-for-service plans, in part, because the risk adjustment model is calibrated on fee-for-service claims data. See Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy (Washington, D.C.: March 2025), 350.

[17]Jodi Liu, et al., Environmental Scan on Consolidation Trends and Impacts in Health Care Markets, (Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation, Sept. 30, 2022).

[18]Martin Gaynor, Farzad Mostashari, and Paul Ginsburg, Making Health Care Markets Work: Competition Policy for Health Care (April 2017), https://www.congress.gov/116/meeting/house/109024/witnesses/HHRG-116-JU05-Wstate-GaynorM-20190307-SD002.pdf.

[19]See J Michael McGinnis, Pamela Williams-Russo, James R. Knickman, “The Case for More Active Policy Attention to Health Promotion.” Health Affairs, vol. 21, no. 2 (2002) and Steven A. Schroeder, “We Can Do Better — Improving the Health of the American People,” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 357, no. 12 (2007).

[20]Social programs include those programs providing targeted assistance to address needs including health, old age, disability, family, unemployment, and housing.

[21]National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty (Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press, 2019).

[22]Section 1115 of the Social Security Act (Section 1115) gives the Secretary of Health and Human Services authority to give states additional flexibility to design and improve their programs through experimental, pilot, or demonstration projects to demonstrate and evaluate state-specific policy approaches to better serving Medicaid populations. See 42 U.S.C. § 1315(a). The State Innovation Models initiative partnered with states to advance multi-payer health care payment and delivery system reform models.

[23]A patient navigator helps patients communicate with their health care providers, so they get the information they need to make decisions about their health care. Patient navigators may also help patients set up appointments for doctor visits and medical tests and get financial, legal, and social support.

[24]Nemours Children’s Health is a large integrated pediatric health system providing services in Delaware, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Florida.

[25]Meera Viswanathan et al, Social Needs Interventions to Improve Health Outcomes: Review and Evidence Map (Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute; August 2021).

[26]For the purposes of this forum, participants considered value in terms of improving health care quality, access, equity, or some combination of the three.

[27]National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Implementing High-Quality Primary Care: Rebuilding the Foundation of Health Care (Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press, 2021).

[28]Capitated payments are fixed amounts paid to providers per patient, per period, regardless of the services provided.