FEDERAL SPENDING TRANSPARENCY

Actions Needed to Help Ensure Procurement Data Quality

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional requesters.

For more information, contact: Paula M. Rascona at RasconaP@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

The Federal Procurement Data System (FPDS) is the government’s principal repository for procurement information, some of which is displayed on USAspending.gov, the official source of federal spending data. In fiscal year 2024, federal agencies reported about $755 billion in procurement obligations to FPDS. FPDS is part of the Integrated Award Environment (IAE), a suite of systems administered by the General Services Administration (GSA) that tracks federal award data. The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) provides guidance to agencies for annually certifying the quality of the data they report to FPDS. Agencies do so through procurement data quality reports.

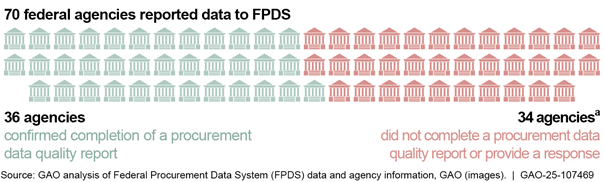

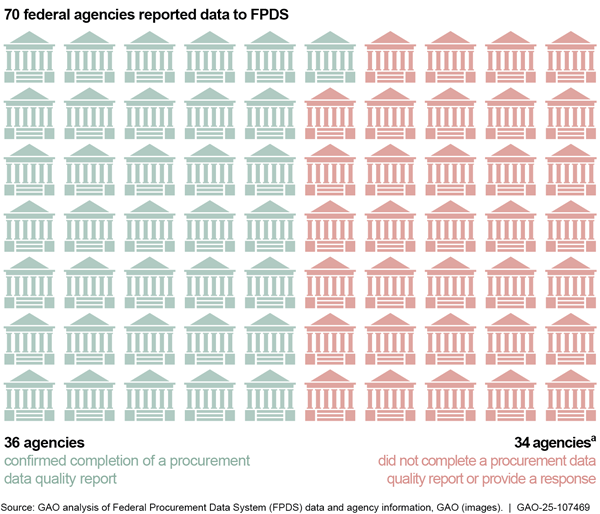

Of the 70 federal agencies that reported data to FPDS for fiscal year 2023, 36, or 51 percent, confirmed completion of procurement data quality reports.

aOf these 34 agencies, 23 did not complete a report and 11 did not respond to GAO’s requests to provide copies of their reports, if any. These 34 agencies accounted for almost $2 billion, or about 0.26 percent, of the $759.2 billion in contract obligations reported to FPDS for fiscal year 2023.

In addition, the 24 agencies’ procurement data quality reports GAO reviewed did not meet all relevant OMB reporting requirements. For example, two did not certify that procurement data were timely entered into FPDS, and 19 did not submit their reports within OMB’s deadline. Implementing monitoring procedures would help OMB ensure that agencies are meeting OMB requirements, thus providing assurance about the quality of federal procurement data.

GAO also found that five selected agencies varied in the extent to which their verification and validation procedures and corrective actions help ensure procurement data quality. For example, one did not design a statistically valid sampling methodology, and three did not adequately develop or document corrective actions to address identified issues. While two have since addressed other issues GAO found, remaining issues could be addressed by enhancing sampling procedures and documenting corrective actions to help ensure that selected agencies adhere to OMB requirements and improve procurement data quality.

As of May 2025, GSA had consolidated and retired 10 of its 13 IAE legacy systems. However, GSA lacks a plan and timeline to modernize the remaining three systems, including FPDS. By finalizing a plan to complete the modernization of its IAE systems, GSA would help create a more streamlined, efficient, and integrated federal acquisition process.

Why GAO Did This Study

Ensuring procurement data quality helps agencies and policymakers make data-driven decisions, improve public trust, and promote the efficiency and effectiveness of government.

GAO was asked to review various aspects of data quality on USAspending.gov and its feeder systems, as well as the modernization of the IAE. This report examines, among other objectives, the extent to which (1) agencies completed procurement data quality reports consistent with relevant guidance; (2) selected agencies have procedures and corrective actions to help ensure procurement data quality in FPDS; and (3) GSA developed modernization plans for the IAE legacy systems, including FPDS.

GAO reviewed procurement data quality reports for fiscal year 2023, which were the most recently available at the time of its review. To understand agencies’ relevant policies and procedures, GAO obtained and reviewed agency documents. GAO also interviewed officials at GSA and the Departments of Defense (DOD), Energy (DOE), Health and Human Services (HHS), and Veterans Affairs (VA). GAO selected these agencies because they had the largest contract obligations. GAO also interviewed staff at OMB.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making 12 recommendations—five to OMB; three to GSA; and one each to DOD, DOE, HHS, and VA. GAO is recommending that these agencies take various steps, such as developing monitoring procedures and root cause analyses, to enhance their ability to ensure procurement data quality. GSA, DOD, DOE, HHS, and VA concurred with these recommendations. OMB did not provide comments on this report.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

CCB |

Change Control Board |

|

CFO |

chief financial officer |

|

DATA Act |

Digital Accountability and Transparency Act of 2014 |

|

DOD |

Department of Defense |

|

DOE |

Department of Energy |

|

DUNS |

Data Universal Numbering System |

|

FAR |

Federal Acquisition Regulation |

|

FPDS |

Federal Procurement Data System |

|

GSA |

General Services Administration |

|

HHS |

Department of Health and Human Services |

|

IAE |

Integrated Award Environment |

|

IDV |

Indefinite Delivery Vehicle |

|

NAICS |

North American Industry Classification System |

|

OMB |

Office of Management and Budget |

|

PCE |

Procurement Committee for E-Government |

|

PMO |

Program Management Office |

|

SAM |

System for Award Management |

|

VA |

Department of Veterans Affairs |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

September 25, 2025

Congressional Requesters

The push for improved spending data quality and transparency has increased significantly over the last several years. Quality and reliable federal spending data are critical to help identify instances of waste, fraud, and abuse of taxpayer dollars. Such data also help agencies and policymakers make data-driven decisions, improve public trust, and promote the efficiency and effectiveness of government.

Under the Digital Accountability and Transparency Act of 2014 (DATA Act), the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and the Department of the Treasury have shared responsibilities to establish government-wide data standards that should produce consistent, comparable, and searchable spending data for any federal funds made available to or expended by federal agencies.[1] Further, OMB and Treasury are responsible for ensuring that the standards are applied to the data made available on USAspending.gov.

USAspending.gov is the official source of federal spending information. The website obtains data from different sources, including agencies and government-wide systems.[2] Some of these systems are part of the Integrated Award Environment (IAE), a suite of government-wide federal award data systems the General Services Administration (GSA) administers. The Federal Procurement Data System (FPDS), one of the IAE systems managed by GSA, serves as the government’s principal repository for procurement information.[3] For fiscal year 2024, federal agencies reported about $755 billion in procurement obligations to FPDS.[4] Since 2008, GSA has worked to modernize the IAE legacy systems by consolidating them into a single portal.

Agencies are required to annually certify to OMB and GSA that procurement data reported to FPDS are complete, accurate, and timely.[5] According to OMB, from fiscal year 2017 through fiscal year 2022, the 24 Chief Financial Officers (CFO) Act[6] agencies self-certified that the procurement data submitted to FPDS were, on average, 97.68 percent accurate and 99.14 percent complete and timely for 25 key data elements.[7] A full list of these elements is provided in appendix I. However, in our prior work examining the quality of federal spending data made available to the public under the DATA Act, we raised concerns about data timeliness, completeness, and accuracy.[8]

This report is part of a series of reports in response to your request for us to review various aspects of data quality on USAspending.gov and its feeder systems, as well as the modernization of the IAE. This report examines the extent to which (1) agencies completed procurement data quality reports consistent with relevant guidance when submitting the reports to OMB and GSA; (2) selected agencies have procedures and corrective actions to help ensure procurement data quality in FPDS; (3) OMB and GSA used information from agencies’ procurement data quality reports to help support agencies and improve data quality in FPDS; and (4) GSA developed IAE modernization plans for the remaining legacy systems, including FPDS.

For objective one, we reviewed OMB guidance and related sections of the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) to identify relevant reporting requirements.[9] We analyzed FPDS data to identify which agencies reported data to FPDS for fiscal year 2023.[10] We identified 70 agencies that reported data to FPDS and contacted them all to obtain their procurement data quality reports for fiscal year 2023, if completed. For our more detailed analysis, we collected and categorized information from the 24 CFO Act agencies’ procurement data quality reports and then compared them to relevant OMB reporting requirements and the FAR to assess consistency.[11] Additionally, we interviewed OMB staff and GSA officials to understand their respective roles and responsibilities for collecting, tracking, and monitoring procurement data quality reports, as well as to discuss guidance requirements.

To address objective two, we selected a nongeneralizable sample of five agencies with the highest total contract obligations reported for fiscal year 2023.[12] We selected (1) the Department of Defense (DOD), (2) the Department of Energy (DOE), (3) the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), (4) the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), and (5) GSA. We also selected a subsample of components for agencies that delegated implementation of procedures and corrective actions to their components. Specifically, we selected three components for DOD (Departments of the Air Force, Army, and Navy) and one component for GSA (Federal Acquisition Service). We selected these components based on their respective agency’s highest-reported total contract obligations for fiscal year 2023.

Because we made a nongeneralizable selection of agencies and components, our findings for this objective cannot be used to make inferences about other agencies and components. However, we determined that the selection of these agencies and components was appropriate for our design and objectives and that the selection would generate valid and reliable evidence to support our work.

For the selected agencies and components, we assessed procedures, corrective actions, and supporting documentation for consistency with FAR and OMB guidance to help ensure procurement data quality in FPDS. We also interviewed officials from each selected agency and component to understand the verification and validation procedures they implemented to assess fiscal year 2023 procurement data quality.

To address objective three, we reviewed agency procurement data quality reports for all 24 CFO Act agencies for fiscal year 2021 through fiscal year 2023 to identify any barriers or challenges that agencies reported that OMB or GSA could provide support for. Additionally, we interviewed OMB, GSA, and selected agencies’ officials to discuss the barriers or challenges that agencies reported as well as understand the support OMB and GSA provided to address them and improve procurement data quality overall. We also interviewed members of the Procurement Committee for E-Government (PCE) to understand the committee’s role and responsibility within the federal government and obtain committee members’ insights about procurement data quality issues.[13]

For objective four, we reviewed and summarized GSA’s documentation related to its IAE modernization effort for remaining legacy systems. In addition, we interviewed officials from GSA, OMB, and the PCE to further understand IAE systems modernization efforts. Additional details regarding our objectives, scope, and methodology are provided in appendix II.

We conducted this performance audit from March 2024 to September 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Federal Procurement Data System

The Office of Federal Procurement Policy Act of 1974 required OMB to establish a system for collecting and developing information about federal procurement contracts.[14] To meet this requirement, OMB implemented FPDS in 1978. GSA administers the system on OMB’s behalf. The FAR requires federal agencies to submit procurement data to FPDS.[15] For fiscal year 2024, agencies reported about $755 billion in procurement obligations to FPDS.

As the authoritative source for the federal government’s procurement data, FPDS serves as the centralized contract database, repository, and comprehensive web-based tool for agencies to report and review their contract actions.[16] The data it contains inform the Congress, federal managers, oversight bodies, and the public about how much agencies obligate for procurements. These data also provide a means to help assess the effect of federal policy initiatives and programs.

USAspending.gov extracts procurement data from FPDS daily. We have previously reported on actions agencies should take to improve the quality of federal spending data available on USAspending.gov, such as having unique identifiers that result in accurate and complete display of data.[17] In addition, agency inspectors general have reported control deficiencies affecting the quality of USAspending.gov data, such as agency data-entry errors and inadequate validation and reconciliation procedures.[18]

While the DATA Act required agency inspectors general to review and report on the completeness, timeliness, quality, and accuracy of agency data submissions to USAspending.gov, which include data from FPDS, that requirement expired in 2021. In March 2022, we recommended that the Congress consider extending the requirement for agency inspectors general to periodically report on the quality of agency USAspending.gov data.[19] If acted on, this recommendation could help ensure that the quality of agency data submissions to USAspending.gov continues to improve.

FPDS Annual Verification and Validation Process

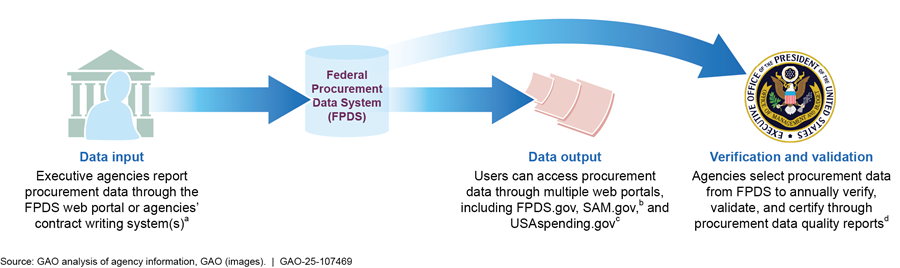

OMB provides guidance to agencies to annually verify and validate procurement data reported to FPDS. These data are publicly available through the FPDS web portal and some of their contents are also available on the System for Award Management (SAM.gov) and USAspending.gov (see fig. 1).[20]

aFPDS serves as the government’s principal repository for procurement information. Agencies can access FPDS at https://www.fpds.gov to report their data or configure their contract writing system(s) to interface with FPDS for reporting.

bThe System for Award Management (SAM.gov) is one of multiple online systems of the General Service Administration’s Integrated Award Environment that facilitates the federal awards processes.

cUSAspending.gov is the official source of federal spending information and obtains procurement data daily from FPDS.

dAgencies are to submit their annual

procurement data quality reports to the Office of Management and Budget within

120 days after fiscal year-end.

OMB is responsible for issuing government-wide policy and procedural guidance to federal agencies for ensuring the quality, objectivity, utility, and integrity of the information they report.[21] To help ensure the quality of federal procurement data, OMB has issued several guidance memorandums since October 2007[22] that outline the steps for agencies to annually verify and validate their FPDS data as required by the FAR.[23] Specifically, upon validation of the prior year data, agency chief acquisition officers must submit to OMB and GSA an annual certification that the data they submitted to FPDS are complete, accurate, and timely. OMB’s latest memorandum, from May 2011, includes guidance for agencies to complete and submit their procurement data quality report in accordance with the contract reporting responsibilities outlined in the FAR.[24]

The OMB May 2011 memorandum states that agencies are expected to follow their own internal procedures for sampling and validating the data they submit to FPDS. Nevertheless, these procedures must meet the sampling requirements listed in the memorandum. OMB outlines 25 key data elements in its May 2011 memorandum that agencies must review for accuracy. A full list of these elements is provided in appendix I.

Agencies document their data quality test results using a standardized reporting template. The template serves as an agency’s procurement data quality report annually submitted to OMB and GSA. The template includes the following:

· Data quality certification statements. OMB guidance requires agencies to certify

· the percentage of contract actions reported during the fiscal year that were complete and timely;

· that data quality assurance procedures and appropriate sampling techniques were used for sampling and validation results reported;

· that policies, procedures, and internal controls were in place to monitor and improve procurement data quality generally; and

· that agency controls include regular reviews of contractor-provided data to assess compliance with reporting requirements and completeness of the data.

· Verification and validation test results. OMB guidance requires agencies to review a statistical sample of records to test the accuracy of the FPDS key data elements and report the results, including

· the total contract action reports sampled,[25]

· the percentage of total procurement obligations covered by the sample,

· accuracy rates for each key data element, and

· the overall data element accuracy rate.

· Assuring data input accuracy. OMB guidance requires agencies to report the percentage of contract action reports entered through automated contract writing systems, the FPDS web portal, or other means.[26]

· Data quality assurance procedures. OMB guidance requires agencies to provide a brief discussion of agency internal control procedures for data quality, including

· any changes to data quality plans submitted to OMB,

· examples of successful practices contributing to consistently high data quality,

· examples of agency success with improving elements of procurement data quality, and

· barriers or challenges identified through the agency review process for which OMB or GSA could offer support or solutions.

Upon completion, the agency’s senior procurement executive is responsible for signing the procurement data quality report and must submit the report online to OMB and GSA via Connect.gov within 120 days of the end of the fiscal year.[27]

Additionally, the May 2011 memorandum states that to improve procurement data quality throughout the year, OMB and GSA will continue

· collaborating with an interagency working group on data quality, focusing on emerging issues, challenges, solutions, guidance, and process improvements;

· collecting tools and agency best practices and posting them to Connect.gov; and

· collaborating with the Federal Acquisition Institute and the Defense Acquisition University to review and improve related workforce training and development and to develop a better understanding of how procurement data are used through the procurement process.

Integrated Award Environment

In 2001, OMB established the IAE initiative to integrate, standardize, and streamline some of the many different systems that are part of the federal awards life cycle used throughout the government.[28] The IAE is intended to enable agencies to share data and make more informed decisions, make it easier for contractors to do business with the government, and improve data security. In 2008, to further eliminate redundancy, reduce costs, and improve efficiency, GSA began consolidating its portfolio of 13 legacy systems into one integrated system, SAM.gov. Currently, SAM.gov is one of the IAE’s multiple online systems that facilitate the federal awards processes.

At OMB’s direction, GSA has executed and managed the IAE since the initiative began. OMB and GSA established a governance structure for the IAE that includes the following key participants:

· OMB. The agency is responsible for reviewing and concurring on the strategic plan, spending plan, and list of high-level investment priorities to ensure alignment with ongoing initiatives. These initiatives include the implementation of the presidential administration’s priorities and statutory and regulatory requirements. In addition, OMB has final decision-making authority for issues that cannot be resolved by IAE governance bodies.

· GSA. The agency, which includes the IAE Program Management Office (PMO) located within the Federal Acquisition Service, is responsible for operating and maintaining the IAE systems. In addition, GSA is responsible for establishing an IAE modernization plan in coordination with IAE governance bodies.

· Change Control Board (CCB). The IAE PMO administers and chairs the CCB, which is the lead decision-making body for agency-proposed changes related to technology and major system updates for all IAE systems, including FPDS. The CCB is composed of representatives from the 24 CFO Act agencies and three nonvoting members from the Small Agency Council. It serves as a liaison between the agencies and the IAE PMO. In this role, it articulates the representatives’ position on requirements and changes to the IAE. CCB representatives also vote on proposed system changes.

· PCE. This committee serves as an interagency advisory body on procurement issues. Specifically, the PCE is responsible for advising on procurement data and the procurement process and for providing recommendations on procurement community requirements. It also helps determine resolutions between the IAE PMO and CCB if conflicts with procurement issues occur.

· Committee on E-Government for Federal Financial Assistance. This committee serves as an interagency advisory body responsible for advising on financial assistance data and processes and for providing recommendations on financial assistance community requirements.

· Award Committee for E-Government. This committee serves as the primary decision-making body for the IAE systems. The committee votes on high-level investment priorities, strategic plans, road maps, and other issues. In addition, it is responsible for coordinating with OMB and GSA to decide on agencies’ annual contributions for operating and maintaining the IAE systems. This committee consists of senior leaders from both the procurement and financial assistance communities as well as representatives from OMB and other nonvoting advisor agencies.

Federal Agencies Did Not Consistently Complete Procurement Data Quality Reports or Meet Reporting Requirements

Half of Agencies Reporting Fiscal Year 2023 Data to FPDS Confirmed Completing Procurement Data Quality Reports

About half (36 of 70) of federal agencies that reported data to FPDS for fiscal year 2023 provided us with their completed procurement data quality reports.[29] These agencies accounted for over 99 percent of the $759.2 billion in contract obligations reported to FPDS for fiscal year 2023. We found that the remaining 34 agencies either did not complete a procurement data quality report or did not provide a response as to whether they did so for fiscal year 2023 (see fig. 2). Specifically, 23 of the 34 agencies confirmed that they did not complete a procurement data quality report, and 11 of the 34 agencies did not respond to our requests to provide us with a copy of their completed report. These 34 agencies accounted for less than 1 percent of contract obligations reported to FPDS for fiscal year 2023 but nonetheless amounted to almost $2 billion.[30] We determined that 30 of these 34 agencies were executive branch agencies.[31]

aOf these 34 agencies, 23 did not complete a

report and 11 did not respond to our requests to provide copies of their reports,

if any. These 34 agencies accounted for almost $2 billion, or about 0.26

percent, of the $759.2 billion in contract obligations reported to FPDS for

fiscal year 2023.

The FAR requires executive agencies to report certain contract actions, including applicable contract modifications, to FPDS.[32] The FAR, however, does not apply to all executive branch agencies or organizational components of such agencies. For example, it generally does not apply to acquisitions that are funded with nonappropriated funds, and some agencies and programs may have statutory authority to use other acquisition systems, such as the Federal Aviation Administration.[33]

However, OMB does not specify in its guidance which agencies are required to complete a procurement data quality report. We asked OMB to provide a complete list of all agencies required to submit a procurement data quality report. OMB staff told us that they only track report submissions for the 24 CFO Act agencies, as these account for the majority of spending. OMB staff stated that additional agencies submitted procurement data quality reports for fiscal year 2023, but they were not able to provide us a complete list of all agencies.

In addition, there is no clear definition of OMB’s and GSA’s roles and responsibilities for collecting and tracking procurement data quality reports. While the FAR requires certain agencies to submit reports to GSA,[34] GSA told us it does not collect or track these procurement data quality reports and instead defers those responsibilities to OMB. According to OMB staff, however, OMB does not have full responsibility for collecting and tracking the reports. Rather, OMB staff stated that GSA supports the collecting and tracking of reports through Connect.gov.

By specifying and notifying all agencies required to complete procurement data quality reports, OMB would be better positioned to ensure that all such agencies are attesting to the quality of the data they are submitting, as required. In addition, the lack of clearly defined oversight roles and responsibilities for OMB and GSA increases the risk that agencies’ procurement data quality reports will not be submitted as required. This, in turn, reduces assurances for users of FPDS data, such as policymakers and the public, about the quality of federal procurement data when making data-driven decisions.

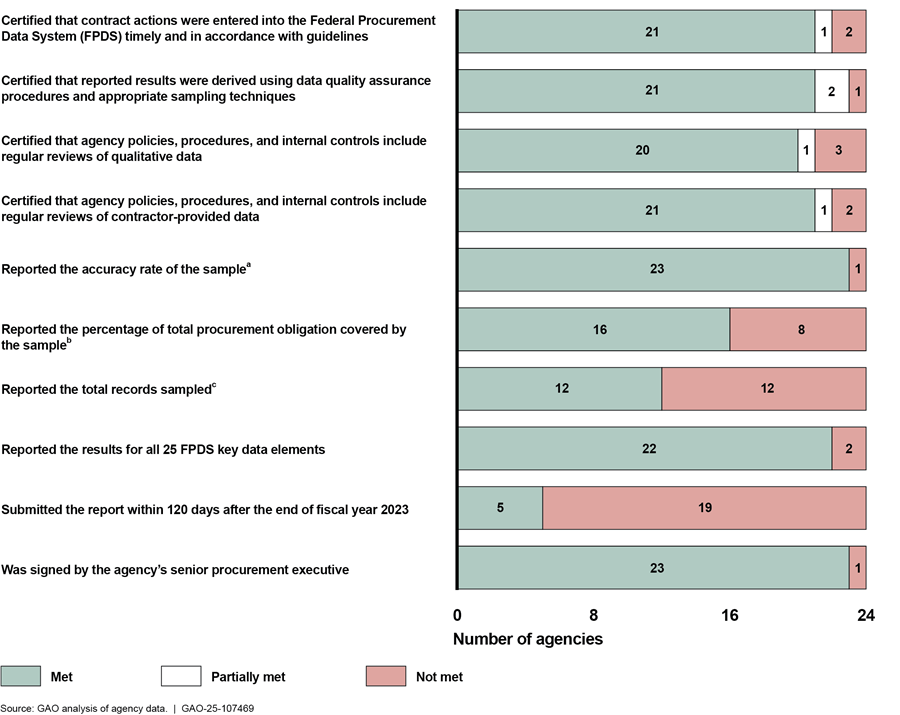

CFO Act Agencies Did Not Meet All Procurement Data Quality Reporting Requirements

The OMB May 2011 memorandum establishes reporting requirements for agencies to meet when completing and submitting their procurement data quality reports. We reviewed procurement data quality reports for all 24 CFO Act agencies and found that none of the 24 met all relevant reporting requirements, as shown in figure 3.

Figure 3: Extent to Which 24 CFO Act Agencies Met Relevant OMB Reporting Requirements in Fiscal Year 2023 Procurement Data Quality Reports

Notes: We collected the fiscal year 2023 procurement data quality reports from the 24 Chief Financial Officers (CFO) Act agencies to assess consistency with relevant Office and Management and Budget (OMB) guidance and Federal Acquisition Regulation requirements. These agencies accounted for the majority of contract obligations reported to FPDS for fiscal year 2023.

“Met” means the agency provided complete evidence that met the entire requirement. “Partially met” means the agency provided evidence that met a portion of the requirement. The “partially met” assessment applied to the first four requirements in the figure and did not apply to the remaining requirements. “Not met” means the agency provided evidence that does not meet any part of the requirement.

aThis rate represents the total of complete and accurate contract action reports divided by the total of contract action reports reviewed in the agency’s sample.

bThis percentage represents the amount of procurement dollars covered by the agency’s sample divided by the total amount of procurement dollars that the agency obligated in the fiscal year.

cThis total represents the total number of contract action reports reviewed in the agency’s sample.

The first four requirements listed in figure 3 are data quality certification statements that the agency must include in its procurement data quality report. Five agencies partially met these requirements as they each modified one of the four original certification statements, and five agencies did not include one or more of these certification statements in their report. In addition, 19 of the 24 CFO Act agencies did not meet the deadline for submitting the report. For example, three agencies submitted their reports more than 30 days late, and another three agencies submitted their reports more than 180 days late.

We found that OMB’s outdated and unclear guidance to agencies, as well as its lack of monitoring procedures, may have contributed to the CFO Act agencies not meeting all reporting requirements as described further below.

· OMB’s May 2011 memorandum includes outdated terminology, contact information, and other information. For example, officials from one agency pointed out that they are following a more current OMB directive than the one referenced in the data quality assurance section of the memorandum.

· OMB’s guidance is unclear and difficult to follow. According to OMB staff, all guidance memorandums for improving federal procurement data quality issued before 2011 are still in effect unless specifically rescinded, and each subsequent memorandum builds upon the others. The lack of streamlined guidance results in duplicative, and sometimes inconsistent, guidance that is challenging to follow and can cause confusion. For example, we found that one agency used the certification statement from the OMB October 2009 memorandum rather than the one from the OMB May 2011 memorandum.[35]

· OMB does not have monitoring procedures to assess whether agencies fully address reporting requirements and submit their reports timely, in accordance with the FAR and OMB guidance. OMB staff confirmed that they do not have formal procedures to review agencies’ annual procurement data quality reports.

Without procedures to monitor agencies’ procurement data quality reports, OMB is not able to help ensure that agencies are meeting FAR and OMB reporting requirements, including submitting them in a timely manner or properly certifying the quality of the data. Further, outdated and unclear guidance that is not streamlined can result in procurement data quality reports that are inaccurate or incomplete and contain inconsistent information. By updating and consolidating its guidance, OMB could provide greater assurance for users about the quality and consistency of federal procurement data that agencies submit.

Selected Agencies Did Not Adequately Design or Document Certain Procedures and Corrective Actions to Address Data Quality

OMB guidance outlines requirements agencies must follow, such as verification and validation procedures, to help ensure FPDS quality data.[36] In meeting these requirements, agencies are expected to develop procedures that help ensure, among other things,

· complete, accurate, and timely FPDS reporting;

· adequate sample design and methodology to select FPDS contract action reports;

· independent and qualified reviewers; and

· corrective actions for identified issues.

We found that the five selected agencies in our review generally had procedures to address many of these requirements. Specifically, agencies had procedures to help ensure that data entered into FPDS are complete and reviewers were qualified. However, we identified instances in which some agencies did not adequately design or document procedures and corrective actions consistent with the OMB guidance.

Four Selected Agencies Did Not Have Adequate Procedures for Ensuring Timely and Accurate Procurement Data; Two Have Since Addressed These Issues

Of the five selected agencies we reviewed, we found that VA generally had documented procedures for ensuring timely and accurate reporting of its procurement data.[37] For example, VA’s procedures require contracting officers to confirm that contract action reports are reported to FPDS within 3 business days after contract award. In addition, VA produces monthly reports of contract actions that are still in draft or error status and provides the reports to contracting officers for review and correction to ensure FPDS data accuracy. However, we found instances in which DOE, GSA, DOD, and HHS did not adequately design or document certain procedures for addressing timely and accurate data. After bringing instances to their attention, DOD and HHS took action to remediate these issues in future reviews.

DOE Did Not Design a Statistically Valid Sampling Methodology

DOE’s sampling methodology for verification and validation procedures did not prescribe a statistically valid method for random sampling of contract action reports. Specifically, rather than properly stratifying its population of contract action reports to target specific types of reports in its sample selection, DOE’s sampling procedures specified rerunning the sample until it obtains the desired representation of transaction types.

OMB guidance establishes that the sample design must be sufficient to produce statistically valid conclusions for the overall department or agency. In designing samples, agencies must ensure that the contract action reports selected constitute a randomly selected statistical sample from a population of contract action reports in FPDS. If agencies want to target specific types of contract action reports for their reviews, OMB encourages the use of stratification in the sample design to do so.[38]

DOE officials stated that the team responsible for conducting verification and validation procedures, including sample selection, is made up of procurement staff with no expertise in sampling, and that the team does not consult with sampling experts, such as statisticians. As a result, DOE officials stated that they did not know that the sampling method the team used was not statistically valid.

Until DOE designs a statistically valid sampling methodology, it lacks assurance that its sample results are valid and cannot draw reliable conclusions about the accuracy of its procurement data.

GSA Did Not Document Detailed Sampling Procedures

GSA did not formally document its sampling procedures in sufficient detail to ensure accurate and consistent application of statistical sampling techniques that meet OMB requirements. Specifically, GSA’s formal documentation was an outline that did not specify the steps GSA takes in designing and selecting its sample, such as how it ensures that the population of contract records is complete prior to selecting the statistical sample of transactions.[39]

OMB’s May 2011 memorandum states that agencies’ sampling procedures must ensure a sample design and size sufficient to produce statistically valid conclusions for the overall department or agency. Further, the October 2009 and May 2011 memorandums state that departments and agencies are expected to establish and follow their own internal procedures for sampling.

GSA officials stated that GSA selects its sample at the department level and provides the sample selections to its components, including the Federal Acquisition Service, for the components to perform verification and validation procedures. GSA officials told us that they did not interpret OMB’s guidance as requiring that sampling procedures be formally documented.

However, without formal documentation of detailed sampling procedures, GSA cannot ensure that it applies accurate and consistent sampling techniques, which could lead to erroneous conclusions about the accuracy of its procurement data. In addition, documentation provides a means to retain organizational knowledge and mitigate the risk of having that knowledge limited to a few personnel, as well as a means to communicate that knowledge as needed to other parties, such as management and auditors.

DOD Did Not Adequately Design Procedures to Help Ensure Timely Reporting but Has Since Addressed This Issue

DOD did not adequately include in its verification and validation procedures a requirement that its components certify that their procurement data were reported to FPDS on time. Specifically, DOD’s Procurement Data Improvement & Compliance Plan includes a certification template that components must complete when reporting their verification and validation review results to DOD.[40] However, this template did not include a requirement for components to certify that they reported FPDS data in accordance with the timelines established in the FAR and as required by OMB guidance.

According to the FAR, an agency’s senior procurement executive is responsible for developing and monitoring a process to ensure timely and accurate reporting of federal procurement data to FPDS. Such data reporting must be completed within 3 business days (or within 30 days in specific circumstances) after contract award.[41] In addition, the OMB May 2011 memorandum requires agencies to certify that the federal procurement data are reported to FPDS within appropriate time frames and in accordance with applicable guidelines.

DOD officials stated that DOD did not intentionally omit a requirement that components certify timely reporting of FPDS data. Officials added that DOD has procedures for its components to report FPDS data timely, and as such, the missing requirement should not be interpreted as noncompliance with the FAR. However, the officials acknowledged that DOD’s procedures could be improved. As a result, DOD updated its fiscal year 2025 documented procedures to require its components to certify timely reporting of FPDS data in accordance with FAR requirements.

By updating its procedures, DOD enhanced adherence to FAR and OMB requirements, which helps ensure that DOD’s federal procurement data are timely reported to FPDS.

HHS Did Not Document How It Met Reviewer Independence Requirements but Has Since Addressed This Issue

HHS did not obtain evidence to confirm the independence of its verification and validation reviewers. Specifically, HHS did not verify that the individuals performing the reviews were independent from the contracting officers who awarded the contracts or recorded the contract data.

OMB’s May 2011 memorandum requires verification and validation reviews to be completed by someone other than the contracting officer who awarded the contract or the person recording the contract data.[42] Further, the October 2009 memorandum states that reviewer independence is a factor that affects the quality of reported data accuracy results. This OMB memorandum also requires agencies to report any additional actions they take, beyond those required by OMB guidance, to ensure that reviewers are independent.

HHS guidance required that verification and validation reviewers be separate from the individuals who awarded the contracts or entered the contract data, but it did not include procedures to verify that these independence requirements were met.[43] HHS acknowledged the lack of procedures and updated its guidance in fiscal year 2025 to verify that, going forward, reviewers are independent.

By putting in place procedures that verify reviewer independence, HHS helped ensure that its FPDS verification and validation reviews are completed by someone other than the contracting officer or person recording the data. This, in turn, enhances the reliability of the review results and the accuracy of the information it certifies in the annual procurement data quality reports.

HHS, VA, and Navy Did Not Adequately Document Corrective Actions

HHS, VA, and DOD’s Navy component did not adequately document corrective actions to address issues identified through their verification and validation procedures. For the other selected agencies and components in our review (DOE, GSA’s Federal Acquisition Service, and DOD’s Army and Air Force), we determined that either their FPDS data elements’ accuracy rates or documented corrective actions appeared reasonable.

HHS and VA Did Not Document Corrective Action Plans for Certain FPDS Data Elements

HHS and VA did not document corrective action plans for FPDS data elements with recurring low accuracy rates. While officials from both agencies stated that they consider accuracy rates below 95 percent to require corrective action, neither agency documented corrective action plans for FPDS data elements that scored below this threshold for consecutive years (see table 1).

Table 1: HHS and VA FPDS Data Elements with Recurring Low Accuracy Rates, Fiscal Years (FY) 2021–2023

|

Agency |

Federal Procurement Data System (FPDS) data element |

Data element accuracy rate |

||

|

FY 2021 |

FY 2022 |

FY 2023 |

||

|

Health and Human Services (HHS) |

2A. Date Signeda |

77.9% |

75.9% |

88.4% |

|

3A. Base and All Options Value (Total Contract Value)b |

81.8% |

79.2% |

81.0% |

|

|

3B. Base and Exercised Options Valuec |

82.1% |

80.1% |

78.5% |

|

|

Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) |

2A. Date Signed |

97.5% |

87.9% |

89.1% |

|

2D. Estimated Ultimate Completion Dated |

98.3% |

83.4% |

83.6% |

|

Source: GAO analysis of agency documentation. | GAO‑25‑107469

Notes: These FPDS data elements are among the 25 key data elements that agencies must review for accuracy as outlined in the Office of Management and Budget’s memorandum, Improving Federal Procurement Data Quality – Guidance for Annual Verification and Validation (May 2011).

Both HHS and VA consider accuracy rates below 95 percent to require corrective action.

aThis is the date that a mutually binding agreement was reached and signed by the contracting officer or the entity, whichever is later.

bThe Base and All Options Value is the agreed-upon total contract or order value, including all options (if any). For Modifications, this is the change (positive or negative, if any) in the mutually agreed-upon Total Contract Value.

cThis is the contract value for the base contract and any options that have been exercised.

dThis is the estimated or scheduled completion date, including the base contract or order and all options (if any), regardless of whether the options have been exercised.

OMB guidance establishes that correcting control deficiencies is an integral part of management accountability, and agencies must consider such actions a priority. Specifically, agencies should perform a root cause analysis of the deficiency to ensure that subsequent strategies and plans address the root of the problem and not just the symptoms.[44]

Both HHS and VA have some processes in place for taking corrective action. Specifically, both agencies use a third-party vendor software that has an autocorrect feature that identifies, alerts, and corrects errors on sampled contract action reports when reviewers perform verification and validation procedures on FPDS data elements.

HHS officials stated that they notify contracting officers via email about any identified errors on sampled contract action reports and require reviewers to identify the cause. The contracting officer can accept or reject the autocorrection based on the correct value provided by the reviewer. Reviewers can also manually opt out of the autocorrect feature, and the software will send an email to the contracting officer to make a manual correction.

VA officials stated that they rely on the same third-party vendor software for detecting errors on sampled contract action reports, which they consider sufficient to address issues affecting accuracy rates for FPDS data elements. However, the autocorrect feature applies to sampled contract action reports only and therefore does not address potential errors outside of the sample. Neither HHS nor VA developed comprehensive procedures that require the documentation and implementation of root cause analyses and corrective action plans to address identified issues in FPDS data elements with low accuracy rates to prevent reoccurrence.

Without documented corrective action plans that address the root causes of identified issues, there is a risk that issues with FPDS data elements will not be properly and timely addressed and will continue to occur.

Navy Did Not Document Corrective Actions for Identified Issues

The Navy did not document corrective actions to address the root causes of issues found during its verification and validation process, as required by DOD procedures. Instead, the Navy provided a blanket summary response for all issues identified to state that reports were corrected as required and training provided to address the issues, if necessary. Some of the issues the Navy identified pertained to the FPDS data element that describes contract requirements, which was just below the 95 percent target goal for accuracy. According to DOD’s fiscal year 2023 procurement data quality report, this data element is one of DOD’s primary challenges for ensuring FPDS data element accuracy.

Navy officials stated that they chose to provide a blanket summary response as their corrective action plan to streamline the process for documenting corrective actions. However, the Navy’s blanket summary response was vague and did not specify why the issues occurred and what specific corrective actions were needed to address them. While the Navy described that training was provided, if necessary, as a general solution, it did not specify for each issue whether training was the appropriate corrective action. Further, for training that may have been provided, the Navy did not specify what objectives were covered to address identified issues and prevent reoccurrence.

DOD’s FY 2023 Procurement Data Improvement & Compliance Plan (March 31, 2023) requires DOD components to document the appropriate root cause of errors, provide a corrective action plan to DOD if a component’s accuracy target goal is not achieved, and establish a routine schedule for addressing any recurring errors.[45] The plan also specifies that corrective actions should attempt to address the root cause of the data error and not just focus on immediately fixing the error.

By developing and documenting corrective actions and preparing root cause analyses, the Navy can help minimize the risk of recurring errors and help ensure quality information in FPDS.

OMB and GSA Did Not Sufficiently Support Agencies in Addressing FPDS Data Quality Issues

OMB Provided Limited Support to Agencies

OMB provided limited support to agencies in addressing the barriers or challenges they reported in their procurement data quality reports and did not implement efforts to improve procurement data quality, as established in its guidance. Per the OMB May 2011 memorandum, agencies are to include in their annual procurement data quality reports any barriers or challenges experienced during the data quality review process for which OMB or GSA could offer support or solutions. The memorandum also lists collaborative efforts that OMB and GSA are to implement throughout the year to improve procurement data quality. Such efforts include continuing interagency working groups, collecting tools and agency best practices for improving data quality, and reviewing and improving workforce training. However, OMB confirmed that these efforts are no longer in place.

Based on the fiscal years 2021 through 2023 procurement data quality reports for the 24 CFO Act agencies, 11 agencies reported barriers and challenges in which OMB or GSA assistance was needed to address issues affecting FPDS data quality. For example, GSA noted in its fiscal years 2022 and 2023 procurement data quality reports that limitations in FPDS were causing inaccurate information for two FPDS data elements.[46] According to GSA officials, FPDS does not allow agencies to make changes to these two data elements to ensure that they reflect the most current updates. GSA officials further stated that resolving this issue would require OMB to make a federal policy change. However, as of December 2024, GSA had not received a response from OMB regarding this matter.

Agencies also reported other barriers and challenges for which OMB or GSA could provide support. Examples included insufficient FPDS training and outdated FPDS data dictionary and user manual.

OMB staff told us that they have taken some actions to provide support to agencies and help improve procurement data quality. For example, OMB annually prepares the Federal Government Procurement Data Quality Summary, which summarizes the results of the 24 CFO Act agencies’ procurement data quality reports.[47] OMB staff indicated that in preparing the summary, they review agency procurement data quality reports to identify FPDS data elements with low accuracy rates and review overall trends and challenges. Following these reviews, OMB may contact the agencies identified as having low accuracy rates.

Additionally, OMB staff stated that they participate in Chief Acquisition Officers Council quarterly meetings, in which they remind agencies of the importance of procurement data quality.[48] Further, OMB staff told us that they frequently confer with the Procurement Committee for E-Government (PCE) to discuss topics such as the annual verification and validation process. Additionally, OMB staff stated that OMB provides support for PCE-developed training for specific procurement issues. However, OMB staff stated that they do not formally document these actions and, as such, did not provide us any evidence.

PCE officials told us that while the PCE has taken the initiative to develop some targeted training and tools related to procurement data quality, it does not have a formal role in assisting agencies with training. The PCE stated that the Federal Acquisition Institute and the Defense Acquisition University are responsible for training the acquisition workforce and that agencies also develop their own training. The PCE further told us that it has recommended training options to OMB and suggested that it would be helpful for OMB to encourage the Federal Acquisition Institute and the Defense Acquisition University to provide more functional training that incorporates systems, such as FPDS, throughout the different contracting phases.

While the collaborative efforts listed in its May 2011 memorandum are outdated and no longer in place, OMB has not developed or documented an alternate process to periodically assess and find timely solutions to the challenges and barriers that affect procurement data quality. By having a current documented process to address the challenges and barriers agencies identified that affect procurement data quality, OMB can help enhance procurement data accuracy to enable users to draw reliable conclusions.

GSA Supports Agencies with System Changes, but Communication Is Limited

GSA does not analyze or monitor other agencies’ procurement data quality reports, including the barriers and challenges reported. Instead, GSA’s Integrated Award Environment (IAE) Program Management Office (PMO) manages the IAE systems, including FPDS. The PMO considers implementation of system improvements (including those recommended by agencies) through the Change Control Board (CCB). However, in August 2023, the PMO decided to indefinitely pause CCB meetings and agency-requested system enhancements, focusing instead on maintaining and supporting the IAE systems and making only those enhancements necessary for statutory and regulatory compliance.

According to PCE officials, pausing CCB meetings has reduced communication and transparency by not allowing agencies the ability to discuss and resolve system issues affecting data quality. Agencies have additional options for communication with the PMO. These include submitting tickets to JIRA, GSA’s help portal; emailing the IAE administrator; and holding ad hoc meetings with PMO officials.[49] However, according to the PCE, these avenues do not allow agencies to thoroughly explain their concerns to the PMO or find solutions to issues affecting procurement data quality.

PCE officials told us about an issue an agency reported through the JIRA ticket process. Specifically, the ticket stated that the service contract inventory report from SAM.gov uses an incorrect date field from FPDS, resulting in numerous contracts appearing active when they have already expired.[50] According to PCE and agency officials, the PMO closed the ticket by stating that OMB had thoroughly reviewed the issue and requested no changes. However, the PMO did not provide any additional explanation of OMB’s rationale, thereby leaving the concern unresolved with no further discussion. As a result, to avoid having expired contracts appear in service contract inventory reports, PCE officials stated that some agencies have purposely changed dates in FPDS, leading to inaccurate FPDS data.

PMO officials told us that they cannot implement a system change as requested in the ticket until OMB makes a policy change. Therefore, the PMO believes it has no responsibility to take any further action on this issue as this is a policy disagreement between agencies and OMB.

According to the memorandum of understanding between GSA and OMB regarding IAE governance principles, GSA, as IAE PMO, is responsible for[51]

· ensuring periodic engagement with agencies;

· engaging with OMB on policy interpretations of the federal procurement life cycle when an issue cannot be resolved at the CCB level;

· reporting routinely, on a set cadence, to OMB and governance groups on items such as modernization timelines and progress, regulatory implementation progress, and performance metrics;

· ensuring a transparent mechanism is employed to keep the CCB apprised of capability delivery timing and schedule, and substantial shifts to such deliverables, as appropriate;

· consulting with the CCB to ensure that system changes align with policy requirements; and

· conducting relevant outreach and communications with stakeholders and customers.

In addition, the OMB May 2011 memorandum states that the government has a responsibility to continuously improve the quality of procurement data and information. Further, it states that OMB and GSA are to work collaboratively to implement efforts to improve procurement data quality throughout the year.

According to GSA officials, resource challenges (discussed further below) limited their ability to maintain the scale of support and operations that agencies desire. This includes meeting with CCB members to discuss and implement system enhancements beyond those that meet statutory and regulatory requirements. GSA officials further stated that they are currently developing new processes to enhance transparency and information sharing. However, as of May 2025, GSA did not provide its plan or communicate a time frame for finalizing these efforts.

GSA’s limited communication with agencies and governance groups may reduce opportunities for agencies and GSA to meaningfully engage on FPDS system issues that affect the quality and usefulness of the data. GSA partly relies on agencies to identify system issues and enhance system user experience. Establishing a process for agencies and governance groups to engage in continuous two-way communication with GSA could help facilitate effective, timely solutions to systems issues that affect the quality of procurement data.

GSA Has Taken Steps to Modernize Most of Its IAE Legacy Systems but Lacks Plans to Complete the Initiative

GSA Has Modernized 10 of 13 IAE Legacy Systems

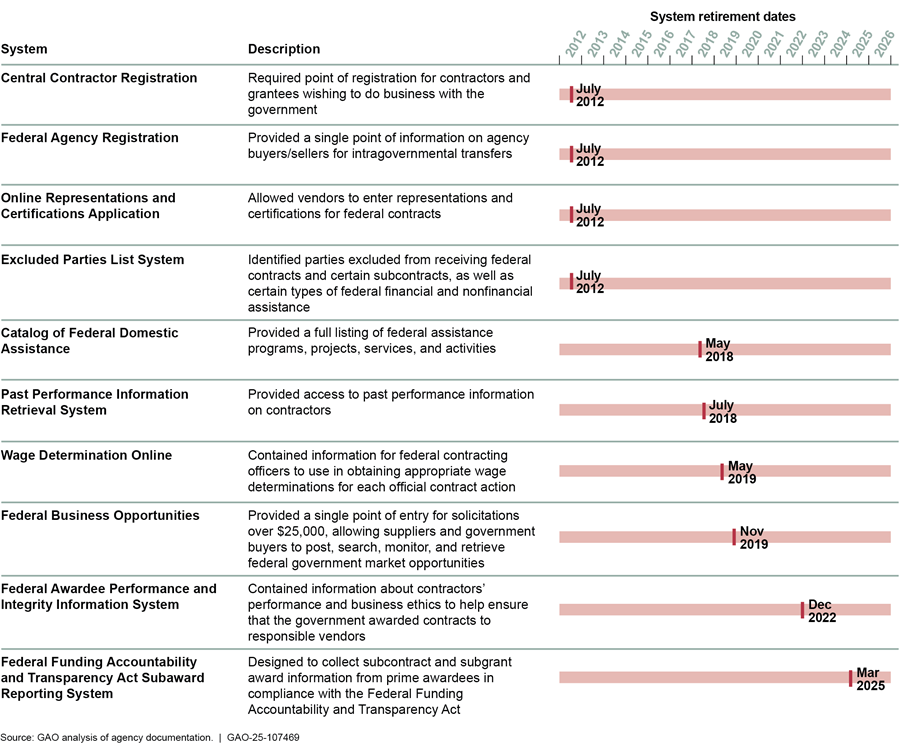

As previously mentioned, GSA began consolidating its portfolio of 13 IAE legacy systems into SAM.gov in 2008. As of May 2025, over 15 years since it began these modernization efforts, the agency had retired 10 legacy systems and consolidated the functions of these systems into SAM.gov or other IAE systems. Specifically, GSA retired the first four systems in 2012, five systems from 2018 through 2022, and one system in March 2025 (see fig. 4).[52]

In September 2023, GSA paused its IAE modernization efforts because, according to PMO officials, it did not have sufficient resources to continue. Shortly after the IAE was established, GSA and the Award Committee for E-Government created a funding structure in which agencies, through interagency agreements, contribute to the program based on their level of activity. This contribution is determined annually by the Award Committee for E-Government and was intended to cover the development, operations, and maintenance of IAE systems. However, the amount of funding approved by the committee has not covered these costs over the last several years. According to PMO officials, the increasing cost of operating IAE systems exceeds the funding amounts that the 24 CFO Act agencies contribute.

In fiscal year 2023, for example, the operating cost for the IAE was approximately $168 million and agencies’ total contribution was approximately $68 million, leading to a gap of nearly $100 million. GSA covered this gap by using funds from its Acquisition Services Fund.[53] According to PMO officials, this resulted in the agency having fewer available funds to modernize the remaining legacy systems. Further, PMO officials stated that more recently OMB has capped the amount agencies’ fees can increase annually, which, according to the officials, does not cover the annual increase in the IAE’s operating costs. PMO officials told us GSA has efforts under way to address IAE’s resource challenges. For example, GSA is pursuing additional funding sources, such as charging a nominal fee to certain federal award recipients. The agency also applied in October 2024 for funding through the Technology Modernization Fund; however, the application was denied.[54]

After GSA paused its modernization efforts, in March 2025, GSA consolidated the Federal Funding Accountability and Transparency Act Subaward Reporting System into SAM.gov. According to PMO officials, the decision to retire this system was made to ensure regulatory compliance. The officials indicated that while the IAE’s current funding situation has affected the agency’s ability to pursue broad modernization, the PMO used funds allocated for legislative and system changes to finalize the subaward reporting system’s retirement.

GSA Lacks a Time Frame for Finalizing a Plan to Modernize the Remaining Three Legacy Systems

GSA has not yet fully consolidated the functions of its three remaining legacy systems, in part because it has not finalized plans to do so. The three remaining systems are FPDS and two other systems that provide functions for, among other things, documenting and reporting on a contractor’s performance, including its subcontracting performance (see table 2).[55]

Table 2: General Services Administration’s Remaining Integrated Award Environment Legacy Systems as of May 2025

|

System |

Description |

|

Federal Procurement Data System |

This system is the authoritative source for the federal government’s procurement data.a |

|

Contractor Performance Assessment Reporting System |

This system hosts applications used to document contractor and grantee performance information, as well as responsibility and qualification data entry. |

|

Electronic Subcontracting Reporting System |

This is an online tool for streamlining the reporting process for subcontracting plan achievements. It also provides agencies with access to a contractor’s subcontracting performance data. |

Source: GAO analysis of agency documentation. | GAO‑25‑107469

aThe Federal Procurement Data System’s reporting function was integrated into the System for Award Management in October 2020.

In July 2024, PMO officials told us they were preparing two plans for modernizing the remaining legacy systems: one based on funding continuing at the present level and the other contingent on the availability of additional funding. The officials stated that they planned to include milestones and cost estimates for consolidating the remaining systems into SAM.gov in both plans. However, as of May 2025, GSA has not developed a modernization plan for the remaining IAE legacy systems and did not provide a time frame for doing so.

Additionally, in May 2025, PMO officials told us that their efforts to develop plans were on hold. The officials stated that they are instead focused on addressing the administration’s priorities for the IAE, which include reducing its operational costs and achieving financial sustainability. PMO officials stated that these efforts include modernizing components of the existing systems that provide a high return on investment, but they did not provide a plan for doing so. According to government and industry best practices, as well as prior GAO reports on the modernization of federal IT, agencies should have documented plans, including time frames, for modernizing legacy systems.[56]

However, even with updated priorities to reduce operational costs and modernize systems that provided a high return on investment, in the absence of documented plans, the agency increases the likelihood of cost overruns, schedule delays, and overall project failure. Further, GSA increases the risk that it will not complete its government-wide initiative—begun in 2008—to consolidate the systems that support the federal awards life cycle. Until it does so, GSA will not fully achieve the goals of the initiative, including reducing the number of systems providing similar services; reducing IT costs; and creating a more streamlined, efficient, and integrated federal acquisition process.

Conclusions

FPDS houses billions of dollars of procurement data that are available to policymakers and agencies for analysis and to support informed business decision-making. Agencies play a key role in ensuring the quality of these data by validating and improving the accuracy of the data they submit to FPDS.

OMB is responsible for developing and coordinating implementation of procurement policy. We identified opportunities for OMB to improve its guidance for procurement data quality reports. These include specifying which agencies are required to submit procurement data and notifying them, defining OMB’s and GSA’s responsibilities for tracking agencies’ reports, and developing and implementing procedures to monitor and assess these reports. While OMB has taken actions over time to help improve procurement data quality, its processes are not always documented, clear, or up to date. By addressing these shortcomings, OMB can better support agencies in improving procurement data quality in FPDS.

There are also opportunities for selected agencies to enhance the design and documentation of verification and validation procedures and corrective actions. While all five selected agencies in our review generally had procedures for verifying the quality of their data, some agencies can further enhance their sampling procedures to draw reliable conclusions and develop root cause analyses to minimize recurring errors. Implementation of these enhancements will help ensure adherence to FAR and OMB reporting requirements and improve procurement data quality.

Finally, there are opportunities for GSA, the agency responsible for administering several government-wide data systems, to develop a process to ensure effective communication with agencies and finalize modernization efforts for remaining IAE legacy systems. By doing so, GSA can enhance transparency and create a more streamlined, efficient, and integrated federal acquisition process.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making a total of 12 recommendations: five to OMB (recommendations 1 through 4 and 10), one to DOE (recommendation 5), three to GSA (recommendations 6, 11, and 12), one to HHS (recommendation 7), one to VA (recommendation 8), and one to DOD (recommendation 9). Specifically:

The Director of OMB should ensure that the Administrator of the Office of Federal Procurement Policy, in collaboration with the Administrator of GSA, specifies and notifies all agencies required under the FAR to complete and submit procurement data quality reports. (Recommendation 1)

The Director of OMB should ensure that the Administrator of the Office of Federal Procurement Policy, in coordination with the Administrator of GSA, defines the roles and responsibilities for both OMB and GSA related to collecting and tracking agencies’ procurement data quality reports. (Recommendation 2)

The Director of OMB should ensure that the Administrator of the Office of Federal Procurement Policy designs and implements procedures to monitor procurement data quality reports to help ensure that agencies address reporting requirements, including submitting reports timely. (Recommendation 3)

The Director of OMB should ensure that the Administrator of the Office of Federal Procurement Policy updates and consolidates the office’s guidance for improving federal procurement data quality to help ensure that all reporting requirements, information, and references included are current and streamlined. (Recommendation 4)

The Secretary of Energy should ensure that the Office of Acquisition Management develops a sampling methodology, in consultation with appropriate experts, to help ensure that DOE’s procurement data quality sampling procedures are statistically valid and meet OMB guidance. (Recommendation 5)

The Administrator of GSA should ensure that the Office of Government-wide Policy documents detailed sampling procedures to help ensure that procurement data quality sampling techniques are performed accurately, consistently, and in accordance with OMB requirements. (Recommendation 6)

The Secretary of Health and Human Services should ensure that the Assistant Secretary of Financial Resources’ Office of Acquisition develops procedures that require the documentation and implementation of root cause analyses and corrective action plans for FPDS data elements with recurring low accuracy rates. (Recommendation 7)

The Secretary of Veterans Affairs should ensure that the Office of Acquisition, Logistics, and Construction develops procedures that require the documentation and implementation of root cause analyses and corrective action plans for FPDS data elements with recurring low accuracy rates. (Recommendation 8)

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Secretary of the Navy, in consultation with the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment, develops and documents corrective actions and prepares root cause analyses for data discrepancies identified by the Navy’s verification and validation process in accordance with DOD’s Procurement Data Improvement & Compliance Plan. (Recommendation 9)

The Director of OMB should ensure that the Administrator of the Office of Federal Procurement Policy develops, documents, and implements a process to periodically assess and, in coordination with agencies, timely remediate the challenges, barriers, and issues that affect agencies’ procurement data quality. (Recommendation 10)

The Administrator of GSA should develop and implement a process, including time frames, to ensure effective, timely, and continuous two-way communication related to procurement data quality issues with agencies and governance groups. (Recommendation 11)

The Administrator of GSA should develop a modernization plan, including time frames, for the remaining IAE legacy systems. (Recommendation 12)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to OMB, DOD, DOE, GSA, HHS, and VA for review and comment. We received written comments from DOD, DOE, GSA, HHS, and VA that are reprinted in appendixes III, IV, V, VI, and VII, respectively. We also summarize these agencies’ comments below. GSA and VA also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate. OMB did not provide comments.

In its comments, DOD concurred with recommendation 9. DOD also stated that it has ensured that the Navy implemented corrective actions and provided root cause analyses for data discrepancies in the Navy’s fiscal year 2025 second quarter submission of its verification and validation reports in accordance with DOD’s Procurement Data Improvement & Compliance Plan. The actions that DOD described, if implemented effectively, would address our recommendation.

In its comments, DOE concurred with recommendation 5 and stated that it will work with its internal actuary to develop a process to provide a statistically valid sample in accordance with OMB guidance. The action that DOE described, if implemented effectively, would address our recommendation.

In its comments, GSA concurred with recommendations 6, 11, and 12 and requested modifications for 11 and 12, which we incorporated, as appropriate. Regarding recommendation 6, GSA stated that its Office of Government-wide Policy has already documented existing validation and verification file-selection procedures and guidance to ensure that reviews are consistent and can be easily transitioned to future program managers. If implemented effectively, the action that GSA described—and detailed in documentation it provided—would address our recommendation. Regarding recommendations 11 and 12, GSA stated that it will take action.

In its comments, HHS concurred with recommendation 7 and stated that it has conducted root cause analyses, implemented corrective actions, and updated the Department of Health and Human Services Procurement Data Annual Verification and Validation (V&V) Guide to institutionalize these requirements as mandatory policy for all operating and staff divisions. Further, HHS also stated that it has implemented a targeted training and outreach strategy for all HHS operating and staff divisions. The actions that HHS described, if implemented effectively, would address our recommendation.

In its comments, VA concurred with recommendation 8 and stated that its Office of Acquisition, Logistics, and Construction will develop procedures to document and implement root cause analyses and corrective action plans to address identified issues in FPDS data elements with low accuracy rates to prevent reoccurrence. The actions that VA described, if implemented effectively, would address our recommendation.

We are sending copies of this report to relevant congressional committees, the Director of the Office of Management and Budget, the Secretary of Defense, the Secretary of Energy, the Secretary of Health and Human Services, the Secretary of Veterans Affairs, and the Administrator of the General Services Administration. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staffs have any questions about this report, please contact me at RasconaP@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. Key contributors to this report are listed in appendix VIII.

Paula M. Rascona

Director

Financial Management and Assurance

List of Requesters

The Honorable James Lankford

Chairman

Subcommittee on Border Management, Federal Workforce and

Regulatory Affairs

Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable Nancy Mace

Chairwoman

Subcommittee on Cybersecurity, Information Technology, and

Government Innovation

Committee on Oversight and Government Reform

House of Representatives

The Honorable Joni K. Ernst

United States Senate

The Honorable Margaret Wood Hassan

United States Senate

The Honorable Clay Higgins

House of Representatives

Table 3: Data Elements Required for Review in Federal Procurement Data System (FPDS) Procurement Data Quality Reports

|

|

Data element |

Definition |

|

1 |

2A. Date Signed |

The date that a mutually binding agreement was reached and signed by the contracting officer or the entity, whichever is later. |

|

2 |

2C. Completion Date |

The completion date of the base contract plus options that have been exercised. |

|

3 |

2D. Estimated Ultimate Completion Date |

The estimated or scheduled completion date, including the base contract or order and all options (if any), whether the options have been exercised or not. |

|

4 |

2E. Last Date to Order |

The last date on which an order may be placed against an indefinite delivery vehicle. |

|

5 |

3A. Base and All Options Value (Total Contract Value) |

For awards, the value is the mutually agreed-upon total contract value, including all options (if any). For indefinite delivery vehicles (IDV), the value is the mutually agreed-upon total contract value, including all options (if any) and the estimated value of all potential orders. For modifications, the value is the change, positive or negative, of these values, if any. |

|

6 |

3B. Base and Exercised Options Value |

The contract value for the base contract and any options that have been exercised. |

|

7 |

3C. Action Obligation |

The amount that is obligated or deobligated by the transaction. |

|

8 |

4C. Funding Agency ID |

The code for the agency that provided the preponderance of the funds obligated by the transaction. |

|

9 |

6A. Type of Contract |

The type of contract as defined in Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) Part 16 that applies to the transaction.a |

|

10 |

6F. Performance-Based Service Acquisition |

Indicates whether the contract action is a performance-based acquisition of services, as defined by FAR 37.601.b |

|

11 |

6M. Description of Requirement |

A brief, summary-level, plain-language description of the contract, award, or modification. |

|

12 |

8A. Product/Service Code |

The code that best identifies the product or service procured. Codes are defined in the General Services Administration’s (GSA) Product and Service Codes Manual. |

|

13 |

8G. Principal NAICS Code |

The North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) codes designate major sectors of the economies of Mexico, Canada, and the U.S. |

|

14 |

9H. Place of Manufacture |

Represents whether the end products procured by the contract are manufactured inside or outside the U.S. in accordance with the Buy American Act and any exceptions or reasons for waivers employed. |

|

15 |

9K. Place of Performance ZIP Code (+4) |

For U.S. locations, this indicates the zip code. Otherwise, it is the postal code available for the foreign location. |

|

16 |

9M. Unique Entity Identifierc |

The unique identifier code for the entity location that received the award. |

|

17 |

10A. Extent Competed |

A code that represents the competitive nature of the contract. |

|

18 |

10C. Other than Full and Open Competition |

The code that most appropriately defines the reason the action was not competed. |

|

19 |

10D. Number of Offers Received |

The number of actual offers/bids received in response to the solicitation. |

|

20 |

10N. Type of Set Aside |

The code for type of set-aside determined for the contract action. |

|

21 |

10R. Fair Opportunity/Limited Sources |

The type of statutory exception to Fair Opportunity. |

|

22 |

11A. Contracting Officer’s Business Size Selection |

The contracting officer’s determination of whether the selected entity meets the small business size standard for award to a small business for the NAICS code that is applicable to the contract. |

|

23 |

11B. Subcontract Plan |

The code for the subcontracting requirement and whether the contract award required a subcontracting plan. |

|

24 |

12A. IDV Type |

The type of IDV associated with the transaction.d |

|

25 |

12B. Award Type |

The type of award being entered by the transaction.e |

Source: GAO analysis of GSA’s FPDS Data Element Dictionary and FPDS Government User’s Manual. | GAO‑25‑107469

aFAR § 16.101. Contract types are grouped into two broad categories: fixed-price contracts and cost reimbursement contracts. The specific contract types range from firm-fixed-price contracts to cost-plus-fixed-fee contracts.

bFAR § 37.601. Performance-based contracts for services shall include a performance work statement, measurable performance standards and the method of assessing contractor performance against performance standards, and performance incentives where appropriate.

cThis data element was previously called “9A. DUNS No.” As of April 4, 2022, the federal government stopped using the Data Universal Numbering System, known as DUNS, number to uniquely identify entities doing business with the federal government and replaced it with the Unique Entity Identifier which entities create in SAM.gov.

dIDV types include government-wide acquisition contracts, multi-agency contracts, other indefinite delivery contracts, federal supply schedules, basic ordering agreements, and blanket purchase agreements.