WOMEN IN AVIATION

Options Available to Lactating Crewmembers and Barriers to Expressing Breast Milk on the Job

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Danielle Giese at GieseD@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107525, a report to congressional committees

Options Available to Lactating Crewmembers and Barriers to Expressing Breast Milk on the Job

Why GAO Did This Study

Leading health organizations recommend that women breastfeed for at least 12 months. Yet many women find that returning to work can be a significant barrier to breastfeeding. Although U.S. workers generally have federal protections for breastfeeding in the workplace, the PUMP for Nursing Mothers Act expressly excludes airline crewmembers from its protections. Crewmembers are therefore largely dependent on the lactation accommodations, if any, their employer chooses to provide.

The Senate report accompanying the fiscal year 2024 Transportation, Housing and Urban Development, and Related Agencies Appropriations Bill includes a provision for GAO to examine barriers to women in the airline industry, such as lactation accommodations for crewmembers. This report examines (1) options for crewmembers to express breast milk that airlines have identified, (2) barriers to expressing breast milk that labor unions representing airline crewmembers have identified, and (3) how FAA and selected airlines have addressed potential safety implications of airlines’ lactation accommodations for crewmembers.

GAO reviewed FAA documents, including requirements on airline safety management and guidance; interviewed FAA officials; and conducted semi-structured interviews with representatives of the eight largest U.S. commercial airlines, based on operating revenues and total employment, and seven labor union associations representing crewmembers of these airlines.

What GAO Found

Pilots and flight attendants (crewmembers) who are lactating may work long shifts and, as a result, may need to express breast milk while on duty. In 2024, 10 percent of U.S. commercial pilots, and 79 percent of U.S. commercial flight attendants, were female. In accordance with Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) regulations, pilots at large U.S.-based airlines may be scheduled for flight time of up to 8 hours between rest periods, while flight attendants may be on duty for as long as 14 hours. Representatives of selected airlines identified the use of wearable, battery-operated breast pumps as one option available to lactating crewmembers while in flight. Other options available to lactating crewmembers include pumping in airport lactation facilities between flights and taking extended leave to delay the return to work after childbirth, according to the representatives.

According to labor unions representing airline crewmembers, crewmembers may face several barriers to expressing breast milk upon returning to work. For example, crewmembers are only allowed to pump during noncritical phases of flight or between flights, neither of which may provide sufficient time to do so.

FAA and selected airlines have leveraged existing processes to address safety implications of crewmembers’ use of breast pumps on aircraft. In January 2025, FAA issued an informational document to airlines that identifies FAA regulations, procedures, and guidance applicable to crewmembers’ onboard pumping, including how airlines can determine the safety of wearable breast pumps. This document advises airlines to consider and assess potential safety risks, such as effects on crewmembers’ ability to carry out their safety duties, and whether pumps that use wireless technology could interfere with aircraft navigation and communications systems. GAO found that three of the eight largest airlines have used existing risk management processes to assess safety risks associated with crewmembers’ use of breast pumps and establish policies to address identified risks. These airlines require, for example, that breast pumps be wearable and hands-free, and that crewmembers not use the pumps during certain flight times, such as takeoff and landing. Representatives of one airline told GAO they had used the FAA informational document to update their internal practices, while three other airlines told GAO they were planning to do so. The eighth airline did not allow crewmembers to express breast milk while on flight duty.

Abbreviations

DOT Department of Transportation

FAA Federal Aviation Administration

FDA Food and Drug Administration

HHS Department of Health and Human Services

PUMP Act Providing Urgent Maternal Protections for Nursing Mothers Act

PWFA Pregnant Workers Fairness Act

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

May 15, 2025

The Honorable Cindy Hyde-Smith

Chair

The Honorable Kirsten Gillibrand

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Transportation, Housing and Urban Development, and Related Agencies

Committee on Appropriations

United States Senate

The Honorable Steve Womack

Chairman

The Honorable James E. Clyburn

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Transportation, Housing and Urban Development, and Related Agencies

Committee on Appropriations

House of Representatives

Leading health organizations recommend that women breastfeed for at least 12 months, and that infants have only breast milk for the first 6 months of life.[1] Yet women find that returning to work can be a significant barrier to breastfeeding due to inflexibility in work hours and locations, and a lack of privacy for breastfeeding or expressing milk. Workers in the United States generally have federal protections for breastfeeding, such as a reasonable break time and a private place other than a restroom to express breast milk.[2] However, commercial airline pilots and flight attendants (i.e., crewmembers) are excluded from some of these protections. Airline crewmembers are therefore largely dependent on the lactation accommodations, if any, their employer chooses to provide.[3] Some crewmembers have found these accommodations insufficient and sought relief through the legal system.[4] As of 2024, commercial airlines in the United States employed approximately 11,000 female pilots and 195,000 female flight attendants, representing 10 percent of all commercial pilots and 79 percent of all flight attendants, respectively.[5]

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) oversees the safety of the airline industry. In this role, FAA requires airlines to ensure the safety of their operational procedures, which may include certain lactation accommodations that airlines choose to implement. In January 2025, FAA issued an informational document for use by airlines that are developing or reviewing their policies for lactating crewmembers.[6] FAA issued this document in response to the FAA Reauthorization Act of 2024, which directed FAA to develop guidance for airlines related to crewmembers’ expression of breast milk while on board an aircraft.[7]

The Transportation, Housing and Urban Development, and Related Agencies Appropriations Bill, 2024, Senate Report 118-70, includes a provision for GAO to examine barriers for women in the commercial airline industry, including those identified in a report from the Women in Aviation Advisory Board, such as lactation accommodations.[8] This report examines (1) options for crewmembers to express breast milk that selected airlines have identified; (2) barriers to expressing breast milk that labor unions representing airline crewmembers have identified; and (3) how FAA and selected airlines have addressed potential safety implications of airlines’ lactation accommodations for crewmembers.

To inform all objectives, we interviewed representatives from eight U.S. commercial airlines. We selected the airlines with the highest annual operating revenues and total employment using 2024 first quarter data from the Department of Transportation’s Bureau of Transportation Statistics.[9] Collectively, the eight selected airlines represent 90 percent of the total employment of the major U.S. commercial passenger airlines.

To identify and describe options for crewmembers to express breast milk, we conducted semi-structured interviews with representatives from the eight selected airlines. During these interviews, we asked representatives about how their airline accommodates lactating crewmembers and any other options available to crewmembers to express breast milk. We also asked about any challenges their airline has encountered in providing lactation accommodations. Because representatives we interviewed were from a sample of airlines, findings from these interviews are not generalizable to all airlines.

To identify and describe barriers to expressing breast milk that crewmembers have faced, we conducted semi-structured interviews with representatives from seven labor union associations representing airline crewmembers.[10] We selected the labor unions based on their representation of flight attendants and pilots from the eight selected airlines. We summarized the information that we collected through these interviews to develop a list of barriers. Representatives that we interviewed included five active flight attendants and nine active pilots. Because representatives we interviewed were from a selected sample of labor unions, findings from these interviews are not generalizable to all labor unions.

To describe how FAA and airlines have addressed potential safety implications of airlines’ lactation accommodations for crewmembers, we reviewed FAA documents, including regulations on airline safety management systems and crewmember duty hours and responsibilities; guidance on ensuring the safety of equipment used in aircraft cabins; and guidance regarding lactating crewmembers on board aircraft. We interviewed FAA officials on how they identify, assess, and mitigate any risks associated with lactation accommodations, including lactation technology and devices that could be used on board an aircraft. We also interviewed representatives from the eight selected airlines regarding steps the airlines have taken to address safety risks, including risks associated with the use of lactation devices while on board an aircraft.

We conducted this performance audit from April 2024 to May 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

FAA’s Role in Lactation Accommodations for Crewmembers

In its safety oversight role, FAA issues operating certificates to airlines offering scheduled commercial service.[11] Certificated airlines must comply with FAA regulations, conform to safe operating practices, and manage risks in their operating systems and environment, following the guidelines of a Safety Management System.[12] As part of this system, airlines must identify and control hazards associated with any changes to the operational environment. Such changes could relate to procedures, equipment, or scheduling, among other things.

FAA regulations for airlines operating under Part 121 generally allow flight attendants to be on duty for as long as 14 hours, and pilots may be scheduled for flight time of up to 8 hours between required rest periods for domestic operations.[13] Yet most lactating women need to express breast milk every 2 to 3 hours to maintain their milk production, according to the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). As a result, lactating crewmembers may need to express breast milk while on flight duty.

FAA regulations and guidance do not directly address whether airlines should provide crewmembers with lactation accommodations, including for the expression of breast milk while in flight.[14] Rather, airlines may provide lactation accommodations for crewmembers as they see fit, as long as such accommodations do not conflict with FAA requirements for safe operations. For example, in response to two 2019 lawsuits that Frontier Airlines pilots and flight attendants filed against the airline, Frontier Airlines agreed to allow crewmembers to pump on board while on flight duty, among other accommodations, according to the American Civil Liberties Union, which represented Frontier employees. FAA, as part of managing risks, requires airlines to ensure that nothing, including devices brought onto and used on the aircraft, interferes with the aircraft navigation and communications systems.[15] These devices include wearable breast pumps that rely on batteries to operate.

Types of Breast Pumps

Breast pumps enable lactating mothers who have returned to work, are traveling, or are otherwise separated from their infant to express breast milk into a sanitized container that can be refrigerated for later use. Many women find it convenient, or even necessary, to use a breast pump to express and store their breast milk, according to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

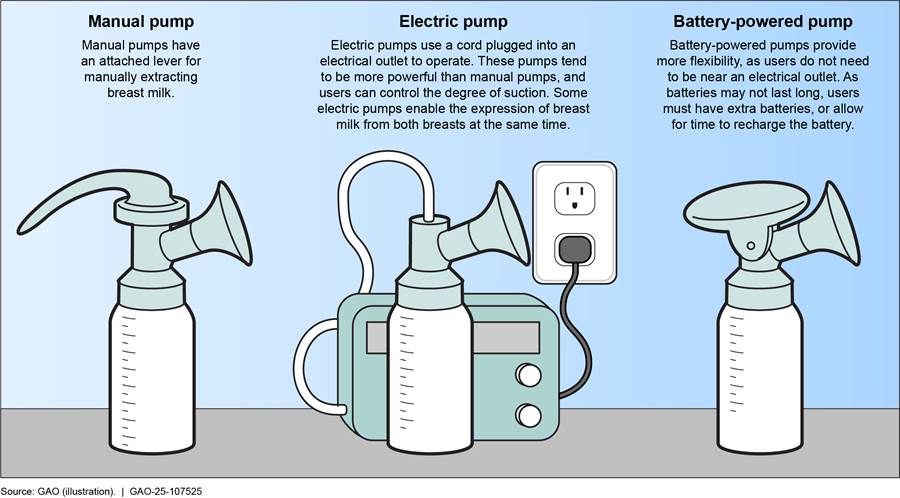

FDA considers breast pumps to be medical devices and regulates breast pumps that are on the market. All pumps include a shield that fits over the breast, a pump for extracting milk, and a container to collect the milk. Several types of breast pumps are available with varying features, such as degree of suction power (see fig. 1).

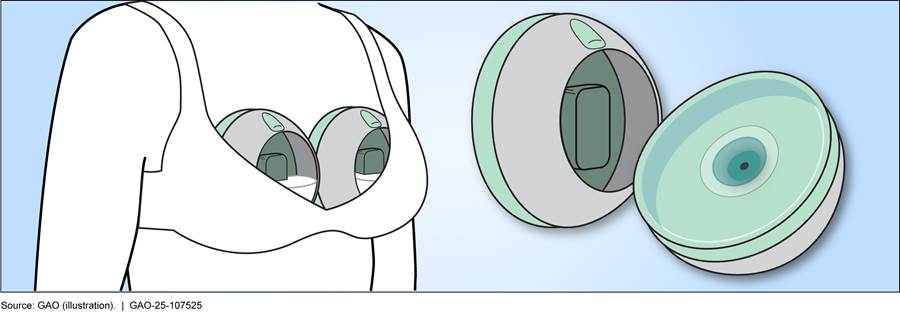

In recent years, manufacturers have developed wireless, wearable battery-operated breast pumps. These pumps are concealed under clothing and are relatively quiet, enabling individuals to do other activities while pumping. As shown in figure 2, wearable breast pumps collect milk in small containers and can fit under a nursing bra. Some wearable breast pumps use wireless technology, such as Bluetooth, and can be managed with a smartphone.

Selected Airlines Identified Wearable Breast Pumps, Airport Lactation Facilities, and Extended Leave as Options for Lactating Crewmembers

Representatives we interviewed from selected airlines identified two options available to crewmembers who wish to express breast milk while on duty: using wearable breast pumps in flight and pumping in airport lactation facilities. Taking extended leave to delay their return to work after childbirth is also an option for crewmembers who would like to continue breastfeeding, according to selected airlines.

Using wearable breast pumps in flight. Seven of the eight airlines whose representatives we interviewed allow crewmembers to use wearable breast pumps in flight. Because the pumps are hands-free and easily concealed under clothing, crewmembers can perform duties and move freely within the cabin while they pump, according to two labor unions representing airline crewmembers.

Representatives from four of these airlines told us that they have written policies regarding crewmembers’ use of wearable breast pumps while on the aircraft, and that their policies specify times during the flight when crewmembers may use pumps. Three of these airlines also require, among other things, that crewmembers wear the pumps under clothing and that, if they need to change or clean the pump, they take a work break and find a private space to do so. These airline crewmembers do not need to seek permission to take advantage of this accommodation. The fourth airline provided an excerpt from its flight attendant manual that includes a general policy that crewmembers are allowed to pump during noncritical phases of flight.

Representatives of three other airlines we interviewed told us that, although the airlines permit the use of wearable breast pumps on board an aircraft, they do not have any written policies or guidance on crewmembers’ use of these devices.[16] Rather, these representatives told us the airlines accommodate crewmembers’ use of wearable breast pumps on a case-by-case basis. For example, crewmembers may request this accommodation when returning to work, and like other workplace accommodation requests, crewmembers can then work directly with their managers and supervisors to accommodate their specific needs.

One of the eight selected airlines prohibits crewmembers from using wearable breast pumps while in flight due to safety and space considerations, according to representatives of this airline. These representatives told us they primarily operate flights with shorter durations, so crewmembers have limited opportunities to pump during flights. In addition, since this airline mostly operates narrow-body aircraft, it cannot guarantee that crewmembers will have a private space to pump. Instead, the airline encourages crewmembers to take care of any lactation needs, including pumping, while at airports before or after flights.

Pumping in airport lactation facilities. Representatives for all eight airlines we interviewed said that lactation rooms and pods available in airport terminals are another option that lactating crewmembers may use before or after flights.[17] Airports that receive certain public funding are required by federal law to have a private lactation space in each terminal building that includes a place to sit, a table or other flat surface, a sink or sanitizing equipment, and an electrical outlet.[18] In addition, representatives of three airlines told us that lactating crewmembers can use airline crew lounges, where available, which may have lactation rooms.

Taking extended leave. Airline representatives we interviewed acknowledged that the options available to lactating crewmembers are limited given the conditions inherent to working on board a commercial aircraft, such as limited time and lack of space. Given these constraints, representatives of three airlines told us that sometimes the preferred option for crewmembers who wish to continue breastfeeding is to remain on leave for a longer period.

The airline representatives we interviewed told us they provide leave that employees can use for this purpose. However, the amount of leave that airlines offer varies, and the leave may be paid or unpaid. Depending on the airline, crewmembers who wish to delay their return to work after giving birth can use various combinations of parental, vacation, and other types of leave, such as leave provided through the Family and Medical Leave Act, according to airline representatives. Among the airlines whose representatives we interviewed, the total amount of leave available to crewmembers following the birth of a child ranges from 3 months at one airline to 17 months at another. Airline representatives said that in some cases, crewmembers might need to take additional medical leave due to issues related to childbirth and lactation, such as mastitis. Paid parental leave also varies among the selected airlines. For example, four of the airlines offer paid parental leave for crewmembers, ranging from 6 weeks to 4 months. Three of the airlines do not offer paid parental leave, but their representatives said crewmembers can use accrued vacation or sick leave.[19] Additionally, one airline offers paid parental leave for pilots but not for flight attendants.

Representatives from six of the seven labor unions we interviewed agreed with the selected airlines that crewmembers who wish to continue to breastfeed generally prefer taking extended leave over the other available options. However, labor union representatives told us that crewmembers may not be able to afford to take the maximum amount of unpaid leave and may therefore need to return to work sooner than they would prefer. In addition, in some cases, crewmembers may have used their available leave before giving birth. For example, according to labor union representatives who are also currently pilots and flight attendants, some crewmembers may take leave during their last trimester, reducing the amount of leave available to them following the birth. Crewmembers who do return to work and wish to continue to breastfeed may face additional barriers, as discussed below.

Unions Representing Crewmembers Identified Scheduling Constraints and Lack of Space as Among the Main Barriers to Expressing Breast Milk

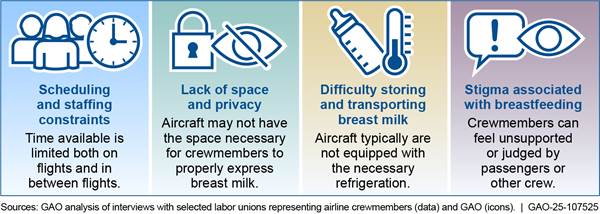

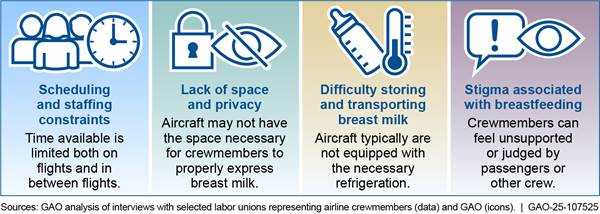

Representatives from the seven labor unions that we interviewed told us that crewmembers may face several barriers to expressing breast milk upon returning to work, including: (1) scheduling constraints; (2) lack of space and privacy; (3) reduced staffing levels; (4) difficulty storing and transporting breast milk; and (5) stigma associated with breastfeeding from passengers and other crewmembers (see fig. 3).

Scheduling constraints. Representatives from all seven labor unions we interviewed identified scheduling constraints, including limited time both on flights and in between flights, as a barrier for lactating crewmembers. According to HHS, most women pump for 15 to 20 minutes per session, while some women may need more time depending on their milk production. This does not include the time required to prepare, change, and clean the pump.

The labor union representatives told us schedules that include short-duration flights can limit the time available for crewmembers to express breast milk while on duty. During these short flights, which largely comprise critical phases of flight, crewmembers spend most of their time performing duties required for the safe operation of the aircraft and may not have enough noncritical flight time to pump.[20] Representatives from four labor unions also told us that wearable pumps used in flight may not provide sufficient suction to pump quickly in the limited time available compared with more traditional, electric breast pumps. In addition, wearable pumps may not remain fully charged during a flight’s duration.

Quick turnaround between flights can also limit the time available for crewmembers to express breast milk. Labor union representatives who are also currently flight attendants or pilots told us that they sometimes have only 25 to 30 minutes between flights, and that flight delays and other unexpected changes can further reduce the time between flights. Moreover, two airlines whose flight attendants’ unions we interviewed require flight attendants to clean the cabin between flights. Representatives of these labor unions told us that this practice further limits the time available for crewmembers to pump. If crewmembers are unfamiliar with an airport, it may also take additional time to find an airport lactation facility to pump between flights. For example, in some cases, these facilities may not be conveniently located or may be far from a crewmember’s assigned gate, according to representatives from three labor unions. In addition, representatives from two labor unions noted that since these facilities are shared with the public, they may not be immediately available for use by crewmembers.

In addition, representatives from three labor unions told us that crewmembers may not be able to obtain a work schedule that accommodates their pumping needs because bidding for schedules is based on seniority. For example, they told us that a junior crewmember may not have the opportunity to bid on trips that are either short enough to avoid the need for pumping during flight or long enough to permit time to pump during the flight.

Lack of space and privacy. Representatives from all the labor unions we interviewed identified the lack of private, clean space on aircraft as a barrier for lactating crewmembers. For example, narrow-body planes—which are typically used for short- to medium-duration flights—do not have a space to pump out of view of passengers, as these planes have a single aisle running through the cabin with passenger seats on each side. On these aircraft, crewmembers must use the lavatory to pump, but labor union representatives told us this is not ideal, because lavatories are small and unsanitary. They noted that most breastfeeding guidelines discourage pumping in a restroom for these reasons.

Representatives from three labor unions told us that having a privacy curtain around passenger or crew seats could be a solution, but that most narrow-body planes do not have privacy curtains installed. They also told us that although wide-body aircraft are more likely to have privacy curtains, certain airlines have discouraged crewmembers from using them for pumping.

Reduced staffing levels. Reduced staffing levels also affect crewmembers’ ability to express breast milk while on duty, according to representatives from five labor unions. One labor union representative told us that airlines have reduced their flight attendant staffing levels to FAA’s minimum staffing requirement in response to airline financial pressures and cost-cutting efforts.[21] As a result, it may be more difficult for lactating crewmembers to find other crewmembers to cover their duties while they pump. Representatives from two labor unions who are also currently pilots told us that because they generally use the lavatory on board as a place to remove their breast pump, they need the support of at least two flight attendants: one to stand in the cockpit and one to stand in front of the lavatory door due to security protocols.

Difficulty storing and transporting breast milk. Representatives from all the labor unions we interviewed identified difficulty storing and transporting breast milk as a barrier for lactating crewmembers. They told us that many aircraft are not equipped with the refrigeration necessary to store expressed breast milk, and that on some airlines, refrigerated compartments in the galley cannot be used for storage of personal items. As a result, crewmembers must store their breast milk with their personal belongings, such as in a lunch bag with an ice pack. Doing so can be especially challenging on long-haul flights that require breast milk to remain cold for long periods of time.

Crewmembers who stay in hotels due to their flight schedules have the additional challenge of keeping their breast milk cold overnight. Labor union representatives told us that while most hotels they stay in have in-room refrigerators, some do not, in which case keeping breast milk at a suitable temperature is difficult. One labor union representative told us that crewmembers in this situation sometimes fill up hotel sinks with ice to keep breast milk cold overnight. Without adequate storage both during and after flights, crewmembers may resort to throwing away breast milk, according to representatives from two labor unions.

Representatives from two labor unions also told us that crewmembers have difficulty transporting expressed breast milk, including through security checkpoints. One labor union representative who is currently a pilot told us that when traveling with her breast milk she was subjected to extra screenings, and that her breast milk had been tested several times while going through security. She also told us that if she wanted to ship her breast milk home while traveling, she was responsible for covering the cost to do so. One airline we interviewed covers the cost to ship breast milk to the lactating crewmember’s home, and another provides an employee discount for overnight shippers.

Stigma associated with breastfeeding. Representatives from five labor unions we interviewed identified stigma associated with breastfeeding as a barrier for lactating crewmembers. They told us that lactating crewmembers can feel unsupported or judged by fellow crewmembers. Female pilots pumping in the cockpit may find it awkward to pump in close proximity to a male pilot and, potentially, to someone seated in the jump seat behind the pilots’ seats, according to one labor union representative. One labor union representative who is also currently a pilot told us she must routinely explain to male pilots what pumping is and what it entails. Representatives from two labor unions also told us that some crewmembers do not understand that expressing breast milk is a physiological need, similar to using the restroom, and therefore may criticize lactating crewmembers for taking extra breaks for pumping.

Further, passengers may be uncomfortable with crewmembers expressing breast milk within their view or frustrated with crewmembers using the lavatory to pump, according to one labor union representative. Representatives from six of the seven labor unions told us that workplace accommodations, including lactation accommodations, are better supported when an airline has a written policy in place. A written policy can be especially helpful in situations that may cause conflict with others.

FAA and Selected Airlines Have Leveraged Existing Processes to Address Safety Implications of Crewmembers’ Use of Breast Pumps on Aircraft

FAA Issued an Informational Document to Airlines Identifying Existing Safety Regulations Applicable to Crewmembers’ Use of Breast Pumps

In January 2025, in response to direction in the FAA Reauthorization Act of 2024, FAA issued an informational document to airlines regarding crewmembers’ expression of breast milk during noncritical phases of flight.[22] The document identifies existing FAA regulations, procedures, and guidance applicable to crewmembers’ expression of breast milk on board, to how airlines can determine the safety of wearable breast pumps, and to ensuring that a crewmember’s pumping will not interfere with safety.[23]

According to FAA, when developing policies for lactating crewmembers, airlines should follow existing FAA regulations and guidance to ensure policies do not (1) create regulatory noncompliance or (2) increase risk to flight safety. Areas of consideration within existing FAA regulations include effects on crewmembers’ ability to carry out their safety duties and whether lactation devices, such as wearable breast pumps, could interfere with the aircraft navigation and communications systems.

FAA advises airlines to conduct a safety risk assessment as a part of their existing Safety Management System when considering options for lactating crewmembers, including allowing the use of wearable breast pumps while in flight. The assessment should consider, at a minimum, the potential effects of

· crewmembers being unavailable or having limited availability to perform their assigned duties;

· lactation devices impeding or interfering with the aircraft flight controls;

· expressed breast milk coming into contact with aircraft flight controls; and

· multiple crewmembers expressing breast milk on an aircraft.

FAA officials told us that it is not FAA’s role to enforce, monitor, or surveil airline activities related to employee lactation accommodations. In its informational document, FAA recommends that airlines’ Directors of Safety, Operations, In-Flight Services, and Training, as well as crewmembers, consider the information and resources referenced in the informational document when developing or reviewing policies and procedures for lactating crewmembers, to ensure work flexibility and safe operation of the aircraft.

Of the seven labor unions we interviewed, representatives from three unions had generally positive views of FAA’s informational document; representatives from three others were generally less positive; and representatives from one had mixed views. Among those with positive views, representatives from two unions said that the informational document offers practical guidelines and clear direction for carriers to establish effective policies and procedures. Conversely, among those who were less positive, representatives from two unions said that the informational document does not offer any practical or effective guidance or clear direction to assist lactating crewmembers. Several of the representatives also noted that the guidance is not enforceable, reiterating what FAA officials have said.

Some Selected Airlines Have Already Assessed Safety Risks of Crewmembers’ Use of Breast Pumps

Although FAA released its guidance to airlines in January 2025, three of the eight selected airlines had already assessed safety risks associated with crewmembers’ use of wearable breast pumps while in flight. According to representatives of one airline, once they became aware of wearable pumps, they started looking into incorporating the pumps into their policies.[24] This airline, followed by two others, used its existing Safety Management System as a framework for developing and implementing policies for crewmembers’ use of wearable breast pumps while on aircraft. Airline representatives said that as part of this process, they identified the potential risks associated with use of the pumps and developed procedures intended to control the risks. Airline representatives also told us that, while developing their policies for wearable breast pumps, airlines worked with the FAA office responsible for overseeing compliance to ensure the policies would sufficiently meet FAA safety requirements.[25] These airlines did not assess risks associated with other options available to lactating crewmembers that do not affect the operating environment, such as pumping between flights or taking extended leave.

The potential risks of breast pumps that airlines and FAA cited were electromagnetic interference due to breast pumps’ wireless capabilities—which could affect the aircraft navigation and communications systems—and fires from lithium-ion batteries in the breast pumps. Other potential risks of breast pumps include interference with the ability of crewmembers to do their jobs, such as a pilot’s ability to operate cockpit controls, according to FAA.

Regarding risks of electromagnetic interference and battery fires, airlines told us that because FAA did not have any guidance specific to wearable breast pumps, they relied on existing FAA guidance on portable electronic devices.[26] This guidance outlines general steps airlines can take to ensure that devices brought on board an aircraft do not cause electromagnetic interference or present a fire risk.

Representatives of one airline told us that since wearable breast pumps were a relatively new technology, they first researched the compatibility of the pumps’ power levels with aircraft avionics, especially on the flight deck. Another airline told us that it was able to build upon the first airline’s findings to inform its safety risk assessment.

To control the identified risks, the three airlines that previously conducted risk assessments established the following requirements:

· Breast pumps must be wearable, hands-free devices with battery capabilities of less than 12 watts per hour; must not interfere with the employee’s mobility or have any distracting audiovisual features; and may not be plugged into an outlet on the aircraft.[27] Bluetooth and wireless capabilities must comply with the airline’s electronic device policy.

· Wearable breast pumps may not be used at certain times, such as when the aircraft is involved in taxi, takeoff, landing, or other flight operations conducted below 10,000 feet.

· Employees should use a restroom break to put on or empty the pump, and they must use caution on the flight to avoid spills.

The three airlines updated their operation manuals for pilots and flight attendants with this information, according to airline representatives. The airline representatives told us that their respective airlines provided copies of these updated manuals to FAA, as FAA requires.[28]

As of February 2025, two additional airlines told us that they are in the process of conducting a safety risk assessment on crewmembers’ use of wearable breast pumps, in accordance with FAA’s recently issued informational document. According to airline representatives, the results of these assessments will help inform their written policies and procedures for lactating crewmembers. Representatives for a sixth airline that currently allows crewmembers to pump on a case-by-case basis told us that they plan to consider FAA’s informational document as they continue to review and update their policies and procedures. A representative for a seventh airline told us that FAA’s informational document was helpful, and that the airline used the document to update its internal practices as needed to address crewmembers’ lactation accommodation needs, including the use of wearable breast pumps, on a case-by-case basis. The remaining airline told us that crewmembers are still prohibited from using breast pumps while on flight duty.

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to the Department of Transportation (DOT) for review and comment. DOT did not have any comments on the report.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Transportation, the FAA Administrator, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions concerning this report, please contact me at GieseD@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix I.

Danielle Giese

Acting Director, Physical Infrastructure

GAO Contact

Danielle Giese, giesed@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Heather Halliwell (Assistant Director), Martha Chow (Analyst in Charge), Lydie Loth, Rebecca Morrow, Josh Ormond, Colleen Taylor, and Laurel Voloder made key contributions to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]These organizations include the American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Nurse-Midwives, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American Dietetic Association, and American Public Health Association.

[2]See the Providing Urgent Maternal Protections for Nursing Mothers Act (PUMP Act), Pub. L. No. 117-328, div. KK, § 102, 136 Stat. 6093, 6093-97 (2022) (codified at 29 U.S.C. § 218d) and the Pregnant Workers Fairness Act (PWFA), Pub. L. No. 117-328, div. II, § 103, 136 Stat. 6084, 6085 (2022) and its implementing regulations at 29 C.F.R. pt. 1636.

[3]The PUMP Act exempts airline crewmembers and some rail carrier and motorcoach employees who are involved in the movement of a locomotive, rolling stock, or motorcoach, or maintain the right of way, from coverage under the law. PUMP Act § 102. While the PWFA does not explicitly exclude airline crewmembers, covered employers (i.e., an employer with 15 or more employees), regardless of size or industry, do not have to provide the accommodation if it causes an undue hardship in the specific situation. PWFA §§ 102-103. Under the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission’s implementing regulations, lactation is a “related medical condition” under the PWFA, and reasonable accommodations may include accommodations related to pumping, such as breaks and a space for lactation. Implementation of the Pregnant Workers Fairness Act, 89 Fed. Reg. 29096 (Apr. 19, 2024); 29 C.F.R. § 1636.3(b), (i)(4).

[4]For instance, in 2019, Frontier Airlines crewmembers filed complaints against Frontier alleging that it discriminated against them and failed to accommodate their medical needs related to pregnancy and breastfeeding in violation of certain federal and state laws, in part because Frontier did not provide them with breaks to express breast milk or accessible, sanitary facilities to use for pumping during work. As a result, Frontier agreed to allow crewmembers to use wearable breast pumps to express milk while on flight duty, among other accommodations, according to the American Civil Liberties Union, which represented Frontier employees.

[5]Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), U.S. Civil Airmen Statistics, 2024. According to FAA, there were a total of 109,727 licensed commercial pilots and 246,402 flight attendants in the U.S. in 2024.

[6]See FAA, Work Flexibility for Lactating Flightcrew Member(s)/Crewmember(s) Onboard Aircraft, InFO 25001 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 16, 2025).

[7]FAA Reauthorization Act of 2024, Pub. L. No. 118-63, § 421, 138 Stat. 1025, 1165 (2024).

[8]Women in Aviation Advisory Board, Breaking Barriers for Women in Aviation: Flight Plan for the Future (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 28, 2022).

[9]The eight selected airlines were Alaska Airlines, American Airlines, Delta Air Lines, Frontier Airlines, JetBlue, Spirit Airlines, Southwest Airlines, and United Airlines.

[10]The seven selected labor unions were Air Line Pilots Association, representing pilots of Alaska, Delta, Frontier, JetBlue, Spirit, United, and others; Allied Pilots Association, representing American Airlines pilots; Association of Flight Attendants-CWA, representing Alaska, Frontier, Spirit, United, and others; the Association of Professional Flight Attendants, representing American Airlines flight attendants; Southwest Airlines Pilots Association, representing Southwest pilots; TWU Local 556, representing Southwest Airlines flight attendants; and TWU Local 579, representing JetBlue flight attendants.

[11]49 U.S.C. §§ 44702, 44705.

[12]All Part 121 air carriers, which are carriers that operate under the requirements of 14 C.F.R. Part 121 and generally include large, U.S.-based airlines, regional air carriers, and all cargo operators, must develop and implement a Safety Management System, which includes systematic procedures, practices, and policies for the management of risk. 14 C.F.R. §§ 5.1, 5.3, 5.51.

[13]14 C.F.R. §§ 121.467, 121.471.

[14]Existing FAA safety regulations do provide appropriate latitude for flight crewmembers to leave their station in connection with physiological needs, including their need to express breast milk, according to FAA. See 14 C.F.R. § 121.543(b)(2). FAA also provides minimum rest requirements for crewmembers. 14 C.F.R. § 121.471.

[15]FAA has regulations specifying what types of portable electronic devices may be brought and used on board an aircraft. These regulations allow the use of hearing aids, pacemakers, and certain other portable electronic devices that airlines have determined can be used safely during aircraft operations without interfering with the navigation and communications systems of the aircraft. 14 C.F.R. §§ 91.21, 121.306. Over the years, FAA has provided guidance to airlines on how to make such determinations.

[16]One of these airlines does have internal guidance directing managers and supervisors to inform any crewmember returning to work after giving birth about available lactation accommodations, according to an airline representative.

[17]A lactation pod is a private, prefabricated, or portable space for nursing mothers to breastfeed or pump breast milk.

[18]This requirement applies to large, medium, and small-hub airports. FAA Reauthorization Act of 2018, Pub. L. No. 115-254, § 132, 132 Stat. 3186, 3205 (2018); the Friendly Airports for Mothers Improvement Act, Pub. L. No. 116-190, § 2, 134 Stat. 974, 974 (2020) (codified as amended at 49 U.S.C. § 47107(w)).

[19]This does not include any state programs for paid parental leave.

[20]Critical phases of flight include all ground operations involving taxi, takeoff, and landing, and all other flight operations conducted below 10,000 feet, except cruise flight. Crewmembers may not perform any duties during a critical phase of flight besides those duties required for the safe operation of the aircraft. 14 C.F.R. § 121.542.

[21]FAA generally requires commercial airlines to staff a minimum of one flight attendant for every 50 passengers on board. Airlines may staff above the FAA minimum, as they see fit. 14 C.F.R. § 121.391.

[22]FAA, Work Flexibility for Lactating Flightcrew Member(s)/Crewmember(s) Onboard Aircraft.

[23]According to FAA, documents that provide information for operators such as airlines, also known as InFOs, help operators meet certain administrative, regulatory, or operational requirements that have relatively low urgency or impact on safety. InFOs do not have the force and effect of law and are not meant to bind the public in any way. Rather, they are intended only to provide clarity to the public regarding existing requirements under the law or agency policies. This InFO is in response to the FAA Reauthorization Act of 2024, directing that FAA issue guidance related to the expression of breast milk by crewmembers on an aircraft during noncritical phases of flight, consistent with the performance of the crewmember’s essential duties on board the aircraft. As such, the InFO does not address other options available to lactating crewmembers that do not have a connection to in-flight safety, such as pumping in the airport between flights or taking extended leave.

[24]Wearable breast pumps became commercially available during the 2010s. According to one manufacturer, it was the first to make a cordless wearable breast pump commercially available in 2017.

[25]FAA Certificate Management Offices specialize in certification, surveillance, and inspection of major air carriers.

[26]FAA has published several documents to aid in aircraft portable electronic device tolerance determinations and provide aircraft operators with a method for expanding the allowance of the use of portable electronic devices throughout various phases of flight: InFO 13010, Expanding Use of Passenger Portable Electronic Devices; InFO 13010SUP, FAA Aid to Operators for the Expanded Use of Passenger PEDS; and Advisory Circular No. 91.21-1D, Use of Portable Electronic Devices Aboard Aircraft. When followed, the guidance provides an acceptable method of compliance with 14 C.F.R. §§ 91.21, 121.306, 125.204, or 135.144, as applicable, when allowing for expanded use of portable electronic devices throughout various phases of flight.

[27]Although wearable breast pumps do not need to be plugged into an outlet to operate, an outlet may be required to charge the pump between uses.

[28]FAA reviews the information in the flight operations manual to ensure it complies with applicable regulatory standards. See FAA Order 8900.1, Volume 3, Chapter 32, Section 2 (providing direction and guidance on the acceptance process for manuals); 14 C.F.R. § 121.135(a)(3) (specifying that manuals must not be contrary to any applicable regulation or the air carrier’s operations specifications or operating certificate).