SERIOUS MENTAL ILLNESS

HHS Assessments of Assisted Outpatient Treatment Have Yielded Inconclusive Results

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO-25-107526. For more information, contact Michelle B. Rosenberg at rosenbergm@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107526, a report to congressional committees

July 2025

SERIOUS MENTAL ILLNESS

HHS Assessments of Assisted Outpatient Treatment Have Yielded Inconclusive Results

Why GAO Did This Study

Serious mental illnesses affected an estimated 14.6 million adults in 2023. Some of these individuals had not received any treatment in the previous year. Untreated mental illnesses can have negative effects, including worsening health, increased medical costs, and possible involvement with the criminal justice system.

Assisted outpatient treatment can help individuals with serious mental illnesses who do not recognize they are ill to receive needed treatment, according to its proponents. However, its involuntary nature makes its use controversial, and research on its effectiveness has produced mixed results.

The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023, includes a provision for GAO to report on assisted outpatient treatment programs that received grants from SAMHSA. This report describes HHS’s efforts to assess the effects of the grant program on participants’ health and social outcomes, and what the assessments have revealed.

GAO reviewed documentation and interviewed officials from HHS regarding its assessment efforts. GAO interviewed a nongeneralizable sample of six grantees, which GAO selected to obtain variation in, among other things, geographic location and levels of urbanization. GAO also interviewed representatives of six stakeholder organizations, including mental health professional associations and advocacy groups. The groups were selected to provide a range of views on assisted outpatient treatment.

What GAO Found

Under assisted outpatient treatment, adults with serious mental illnesses can be ordered by a judge in a civil court proceeding to adhere to community-based treatment in accordance with applicable state laws. It is generally intended for individuals who have been assessed as unlikely to be able to live safely in the community without supervision. In 2014, federal law authorized the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to award grants to organizations to implement assisted outpatient treatment programs. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), a component agency of HHS, has awarded about $146 million in assisted outpatient treatment grants to 63 grantees since the program’s inception in 2016. These 4-year grants were primarily awarded in three cycles: 2016, 2020, and 2024.

Two HHS agencies—the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) and SAMHSA—have made efforts to assess the grant program. Topics studied included participant outcomes such as treatment adherence, psychiatric emergency room visits, hospitalizations, and arrests.

|

Assessment characteristic |

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation |

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration |

|

Assessment type |

Cross-site impact evaluation focused on six of the 17 grantees from 2016. Published in 2024. |

Two reports focused on program outcomes submitted to Congress in 2019 and 2024. |

|

Primary data source(s) used |

Surveys of participants, supplemented with other data, where available. |

Surveys of participants. |

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) information. | GAO-25-107526

Based on its review, GAO determined that HHS’s assessments were inconclusive. Both efforts were hampered by methodological challenges, many of which were inherent in the program and beyond the two agencies’ control.

|

Challenge |

Description |

|

Program variation |

Assisted outpatient treatment programs are governed by state laws and are highly variable. Some of the programs studied included characteristics that differed from what was expected, such as enrolling participants voluntarily in what is inherently an involuntary program, which complicated evaluation efforts. |

|

Self-reported data |

HHS primarily relied on self-reported data from participants. Self-reported data have drawbacks, including the potential for hesitancy to candidly answer questions on sensitive topics such as substance use. |

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) information. | GAO-25-107526

ASPE’s outcome report also included an analysis comparing assisted outpatient treatment participants to individuals enrolled in voluntary treatment of similar intensity. However, data on both groups came from one of the six grantees, and factors such as small sample size limited ASPE’s ability to detect differences between the two groups.

Challenges assessing the grant program are likely to persist because, for example, state laws will continue to vary.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

AOT |

assisted outpatient treatment |

|

ASPE |

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation |

|

HHS |

Department of Health and Human Services |

|

SAMHSA |

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

July 10, 2025

The Honorable Bill Cassidy, M.D.

Chair

The Honorable Bernard Sanders

Ranking Member

Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions

United States Senate

The Honorable Brett Guthrie

Chairman

The Honorable Frank Pallone, Jr.

Ranking Member

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

Serious mental illnesses—those that interfere with major life activities, such as the ability to care for oneself, sleep, eat, and work—affect a substantial number of adults in the United States. According to data from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), about 14.6 million adults had a serious mental illness, such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, in 2023.[1] SAMHSA data show that almost a third of people with serious mental illnesses did not receive any mental health treatment within the last year. Untreated mental health conditions can have wide-ranging negative effects, including worsening health, increased medical costs, strain on personal and social relationships, and possible involvement with the criminal justice system. Mental health treatment can help individuals with serious mental illnesses reduce their symptoms, improve their ability to function, and maximize their ability to live in and contribute to their communities.

According to SAMHSA, as of 2024, most states have laws that permit assisted outpatient treatment (AOT), a civil court procedure whereby a judge orders an adult with a serious mental illness to adhere to community-based treatment.[2] AOT programs must be authorized by state law, and eligibility criteria can vary by state. According to SAMHSA, typical criteria include the risk of worsening health, multiple previous hospitalizations or incarcerations, and nonadherence to treatment.

The Protecting Access to Medicare Act of 2014 authorized the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to establish a program to award grants to organizations for AOT programs for certain individuals with serious mental illnesses.[3] According to SAMHSA, the agency within HHS that administers the AOT grant program, the purpose of the program is to reduce the incidence and duration of psychiatric hospitalization, homelessness, incarcerations, and interactions with the criminal justice system for individuals with serious mental illnesses, while improving the health and social outcomes of these individuals. In addition to authorizing the AOT grant program, the Protecting Access to Medicare Act of 2014 also required HHS to report information to Congress on outcomes of the program.[4]

Mandating the participation of individuals with serious mental illnesses in treatment on an involuntary basis, as AOT does, has been the subject of debate. Those who support AOT believe that it helps ensure treatment for people who need services but whose illness prevents them from recognizing their need, thus enabling them to remain in the community instead of being institutionalized. Those who oppose it are concerned that it threatens civil liberties, diverts scarce resources from those voluntarily seeking treatment, and undermines the relationship between people with serious mental illnesses and service providers. The evidence base supporting the effectiveness of AOT, particularly in comparison to treatment on a voluntary basis, has also been debated, with research showing mixed results.[5]

The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023, includes a provision for us to report to Congress on the efficacy of AOT programs that received grants from SAMHSA.[6] In this report, we describe how HHS has assessed the effects of the AOT grant program on participants’ health and social outcomes, and what HHS’s assessment efforts have revealed.[7]

To describe how HHS assessed the effects of the AOT grant program on participants’ health and social outcomes, and what HHS’s assessment efforts have revealed, we reviewed documentation related to HHS’s assessments of the AOT grant program and interviewed cognizant agency officials. Specifically, we reviewed documentation for the impact evaluation conducted by contractors for the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE)—the HHS component agency that coordinates HHS’s evaluation, research, and demonstration activities.[8] Documentation included published reports describing the methods and results of the evaluation, contract documentation for the contractors who completed the evaluation on ASPE’s behalf, and other documentation from those contractors to better understand the evaluation. Our review included unpublished information that we requested and received from ASPE’s primary contractor, RTI International. In this report, we describe the methods and data sources of ASPE’s evaluation. However, we decided not to include the evaluation’s results because (1) we determined that ASPE and RTI International lacked information needed to help understand the extent to which the results represented all AOT participants included in SAMHSA’s grant program; and (2) our analysis of information we received from RTI International showed a high level of uncertainty for some of the results.[9]

We also reviewed SAMHSA’s reports to Congress on the AOT program, which contain the results of routine data collection and monitoring that SAMHSA conducts for all of its discretionary grant programs, including AOT. As with ASPE’s evaluation, we decided not to include specific results from SAMHSA’s reports to Congress in our report, because SAMHSA’s assessments were affected by some of the same limitations we identified in ASPE’s evaluation.

To better understand the context around AOT and SAMHSA’s grant program, and to provide illustrative examples, we reviewed applications from, and conducted interviews with, a nongeneralizable selection of six AOT grantees from the most recently completed four-year grant funding cycle, which began in 2020. We selected the six grantees to obtain variation in geography, levels of urbanization, and Medicaid expansion status (i.e., whether states opted to expand eligibility for Medicaid to certain low-income adults under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act).[10] We also interviewed representatives from six stakeholder organizations, including mental health professional associations and advocacy groups. We selected these stakeholders to provide a range of views on the effectiveness and appropriateness of AOT; information from these stakeholders cannot be generalized.

We conducted this performance audit from April 2024 to July 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Overview of AOT

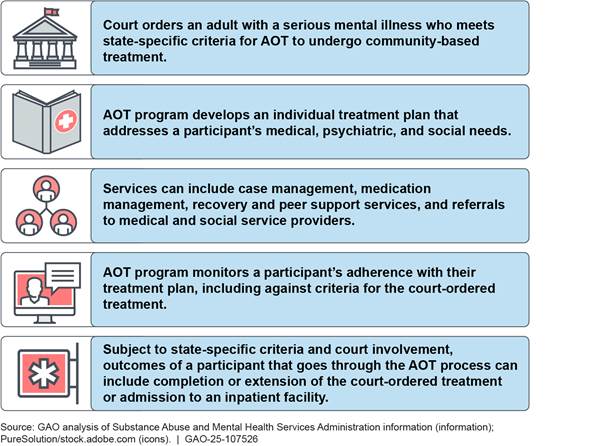

AOT is intended for adults with serious mental illnesses who are assessed as unlikely to be able to live safely in the community without supervision and have a history of treatment nonadherence. In general, AOT involves a civil court procedure whereby a judge orders an adult with a serious mental illness to adhere to community-based treatment for a specified period of time in accordance with applicable state laws. (See fig. 1.) Individuals with an AOT court order are legally mandated to participate in outpatient treatment, which may include routine services such as case management, intensive services like assertive community treatment (see sidebar), and medication management services, among others. They also are monitored for adherence to the treatment plan included as part of the AOT court order.

|

Assertive Community Treatment Assertive community treatment is designed to provide comprehensive community-based services to people with a serious mental illness. Assertive community treatment programs use a variety of treatment and rehabilitation practices, including medications; behaviorally oriented skill teaching; crisis intervention; support, education, and skill teaching for family members; supportive therapy; cognitive-behavioral therapy; group treatment; and supported employment. Under the assertive community treatment model, services are delivered by a mobile, multidisciplinary treatment team. These services are to be available 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. Source: GAO, Mental Health: Community-Based Care Increases for People With Serious Mental Illness, GAO‑01‑224 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 19, 2000). | GAO‑25‑107526 |

Notes: This figure provides an illustrative example of the AOT process. How AOT works in practice depends on a variety of factors including the governing AOT law of the state and the AOT program involved, among others.

According to ASPE and SAMHSA, state laws can specify who may be subject to an AOT court order within the state; the maximum duration of and process for obtaining the initial court order; and the terms for renewing the court order, among other provisions. State laws also can provide judges with discretion over the exact terms of an individual’s AOT court order. In addition, some states may provide funding for AOT programs and services.

According to ASPE, as of 2024, nearly all states have authorized some form of AOT.[11] There is considerable variation across states in the criteria for eligibility, duration and terms of the AOT court order, financing, and other areas. For example:

· Eligibility. Out of the 47 states with AOT laws as of 2016, 32 had a “preventive” type of AOT law, where eligibility criteria required a determination that outpatient commitment is needed to prevent future danger to self or others, or to prevent clinical deterioration that would predictably lead to future danger, according to a SAMHSA report.[12] Under such laws, a person with a serious mental illness who is not currently dangerous, and therefore does not meet legal criteria for inpatient commitment, could be ordered to community treatment on the basis of a complex clinical assessment and prediction about the future.

· Duration. The initial AOT court order is most commonly 90 days (17 states), followed by 180 days (15 states), 12 months (nine states), and 60 days (two states), according to a 2024 ASPE report.[13]

· Financing. Not all states with AOT laws and an active AOT program provide funding for AOT. Out of 20 such states, only four state legislatures had authorized any designated funding for AOT, according to a 2016 survey of how states implemented their AOT programs.[14]

Variation among state AOT laws, and among AOT programs, both within and across jurisdictions, means that no two programs in the U.S. are exactly alike. Specifically, programs differ in their application of AOT’s eligibility criteria and associated target populations, approach to treatment and level of judicial involvement during the order, and the court order renewal or closeout processes. These variations contribute to differences among AOT participants and may also affect the outcomes of AOT and any efforts to examine the effectiveness of AOT.

AOT Grant Program

SAMHSA’s AOT grant program has awarded federal funding to eligible entities to provide services to individuals with serious mental illnesses who meet state-specific criteria for AOT. SAMHSA has awarded these grants as part of three grant cycles (2016, 2020, and 2024) and each grant provides up to four years of funding. The Protecting Access to Medicare Act of 2014 specifies that eligible entities are counties, cities, mental health systems, mental health courts, or any other entity with authority under state law to implement, monitor, and oversee AOT programs.[15] In addition, only entities that have not previously implemented an AOT program are eligible for these grants.[16] SAMHSA also requires AOT grantees to take certain steps to protect the civil rights of AOT program participants.[17] See appendix I for more details of SAMHSA’s requirements.

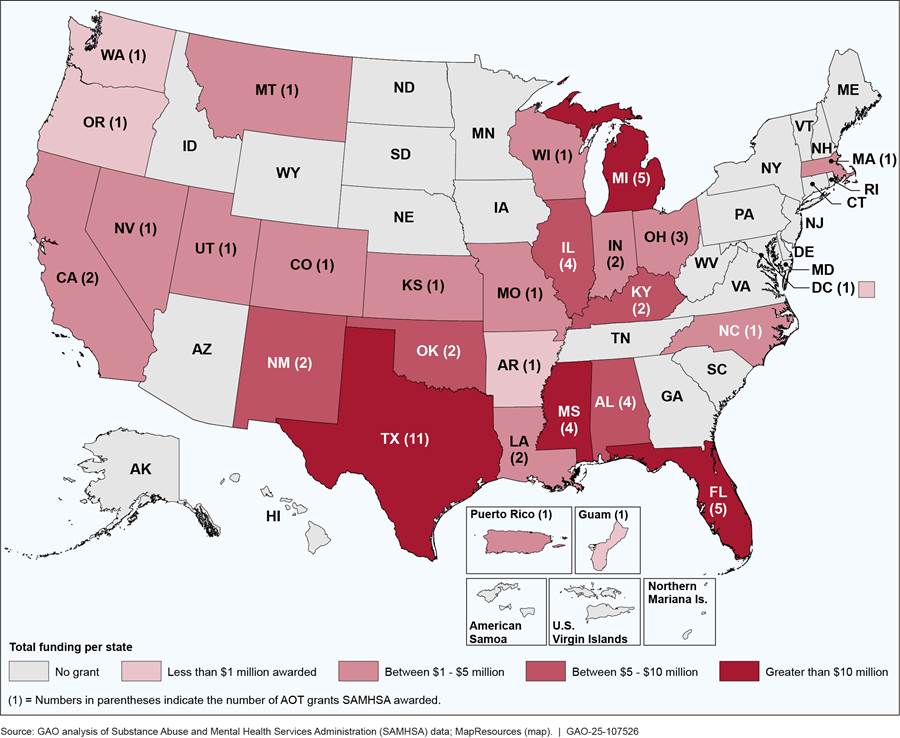

Since 2016, SAMHSA has awarded about $146 million in AOT grants to 63 grantees across 28 states and U.S. territories.[18] (See fig. 2).

Figure 2: States and U.S. Territories That Have Received SAMHSA Assisted Outpatient Treatment (AOT) Grants, Fiscal Years 2016–2024

Notes: Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of AOT grants SAMHSA awarded. Dollar amounts and number of grants do not include three grantees that gave up their grants. Although only entities that have not previously implemented an AOT program are eligible for funding under SAMHSA’s AOT grant program, the dollar amounts and number of grants for Alabama, Florida, and Oklahoma each include a grantee that received funding from both the 2016 and 2020 grant cycles.

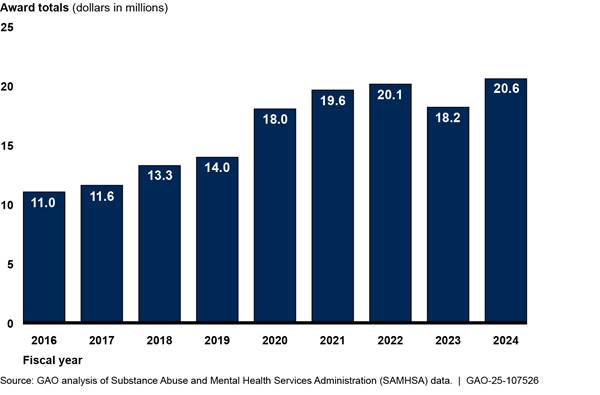

The total amount awarded each year has ranged from $11 million to approximately $21 million from fiscal years 2016 through 2024. (See fig. 3).

Notes: SAMHSA awarded a total of 66 grants, including 21 as part of the 2016 grant cycle, 23 as part of the 2020 grant cycle, and 22 as part of the 2024 grant cycle. Three grantees gave up their grants, leaving a total of 63 grants. Dollar amounts and number of grants do not include grantees that gave up their grants. Each grantee can receive funding for up to four years. Totals include three grantees that received funding under both the 2016 and 2020 grant cycles.

AOT Research

Academic studies assessing the effectiveness of AOT are limited and have produced varying results. Two randomized controlled trials published in 2001 that examined the effectiveness of AOT in the United States—one focusing on a pilot in New York City from 1996 to 1998 and the other on AOT in North Carolina from 1993 to 1996—constitute much of the research on AOT along with non-controlled trials in New York.[19] A randomized controlled trial prospectively and randomly assigns participants to a treatment group that receives the intervention being examined or a control group that does not receive the intervention. Any differences in these groups’ subsequent outcomes are believed to represent the program’s effect because the factors that influence outcomes other than the program should be evenly distributed between the two groups through the random assignment. Studies that do not employ randomized controlled trials—e.g., those that compare outcomes of a single group before and after the intervention or outcomes of the treatment group against a comparison group selected for certain characteristics—may end up with groups that have other factors that affect outcomes. This limits the ability to generalize the studies’ findings.

The New York City randomized controlled trial found no statistical differences between the AOT and control groups with respect to hospitalizations, hospital days, and arrests. The North Carolina study also found that the two groups did not differ significantly in hospital outcomes. However, it identified some statistically significant differences between a subset of the AOT group—i.e., those who had their AOT orders extended—and the control group.

Both studies prospectively randomized assignments to the AOT and control groups to help minimize selection bias.[20] However, the studies had underlying differences in the programs they assessed as well as limitations in their generalizability. For example, New York City’s AOT program did not implement procedures that would have allowed police to transport noncompliant participants to the hospital, whereas local mental health programs in North Carolina followed a protocol to request a court order directing local sheriff departments to locate and bring noncompliant AOT participants to the community mental health program for evaluation and persuasion to accept treatment. In addition, both the New York City and North Carolina studies excluded individuals with a history of violence from the randomized controlled trials. These exclusions mean that the results of the studies may not be generalizable to other AOT programs that included such populations.

Aside from these two randomized controlled trials, researchers have completed other types of studies to demonstrate the effectiveness of AOT, although these studies also have limitations affecting generalizability to all AOT programs. For example, researchers have analyzed available administrative data retrospectively to identify any differences in outcomes between those with AOT court orders and those without.[21] For these types of studies, it would be difficult to conclude that any observed differences were due to AOT and not to another factor influencing the results, in part, because participants were not randomly assigned to AOT or control groups prior to study outcomes.

Two HHS Agencies Conducted Assessments of Assisted Outpatient Treatment, but Methodological Challenges Led to Inconclusive Results

HHS Assessment Efforts

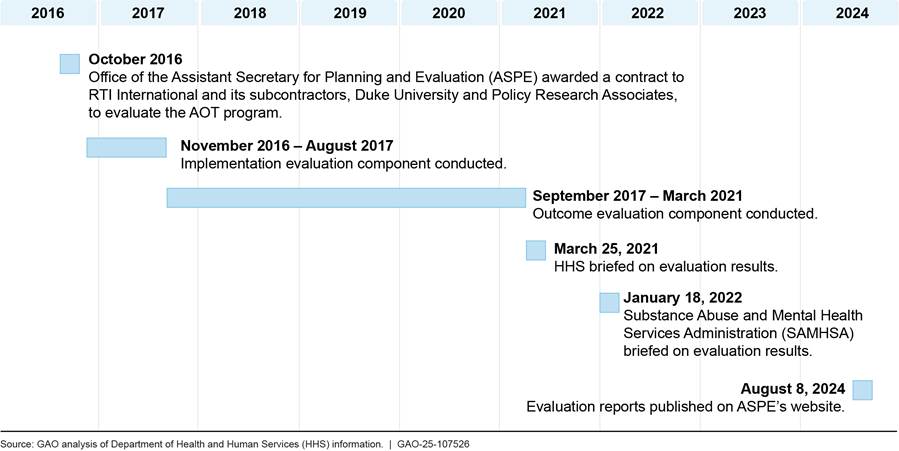

Two HHS agencies have made efforts to assess SAMHSA’s AOT grant program since it began in 2016: ASPE conducted a cross-site impact evaluation and SAMHSA generated two outcome reports based on routine collection of data from grantees. ASPE’s evaluation included an implementation report and an outcome report, which each focused on six of the 17 grantees from the initial cohort of 2016 grant recipients.[22] ASPE began work on its evaluation in 2016 and published it in 2024. Figure 4 provides a timeline of the ASPE evaluation.

Note: This figure presents a timeline of selected ASPE activities related to its evaluation of SAMHSA’s AOT grant program. The evaluation reports published on August 8, 2024, comprise an implementation report, an outcome report, a summary report that provides an overview of the implementation and outcome reports, and an issue brief on assessing the level of judicial involvement in AOT programs.

ASPE’s implementation report describes the design of grantees’ AOT programs, such as civil court processes, target populations, and services provided. ASPE’s outcome report presents information on participants’ outcomes, primarily based on voluntary interviews with participants that occurred when they first joined the program and at later points to assess change over time. The report contains data on topics such as (1) participants’ health and social outcomes and feedback on their experience in the program; (2) costs associated with the AOT program; and (3) a comparison of outcomes of AOT participants and individuals pursuing voluntary treatment of similar intensity.

Outcomes and feedback. The outcome report provides data from all six grantees included in the evaluation on participants’ health and social outcomes, such as treatment adherence, psychiatric emergency room visits, psychiatric hospitalizations, arrests, and substance use. Data were primarily gathered via structured survey instruments ASPE developed to obtain information from AOT participants who agreed to be interviewed. Participants were surveyed as they entered the program and at 6- and 12-month follow-up points, with analysis focusing on comparing initial responses with later time points to gauge the effect of participating in the program. These surveys also collected feedback from participants on the AOT program, such as whether they were satisfied with the services they received, whether they felt coerced to receive treatment, and their views on the general pressures to adhere to treatment. Some AOT participants declined to be interviewed, which is also referred to as participant nonresponse.[23]

Costs. The outcome report contains an analysis comparing the costs of implementing an AOT program with potential costs avoided based on data from three of the six grantees. Specifically, ASPE looked at potential cost avoidance associated with reducing the number of psychiatric emergency room visits and the number and length of inpatient psychiatric hospitalizations among AOT participants. ASPE limited this analysis to three grantees because ASPE’s primary contractor, RTI International, was not able to collect data on the costs of court processes (e.g., hearing costs) directly from courts for the other three grantees. ASPE estimated the costs of emergency room visits and inpatient hospitalizations from costs reported in a 2017 study, adjusted to 2020 dollars.[24] The analysis excluded early implementation costs, such as time spent participating in planning meetings, in part, because such costs may represent one-time, nonrecurring expenses.

Comparison to voluntary treatment. The outcome report compares outcomes between AOT participants and a non-AOT group of individuals with serious mental illnesses who were receiving voluntary, community-based treatment of similar intensity using data from one of the six grantees. The non-AOT group comprised individuals enrolled in assertive community treatment and bridge team programs.[25]

ASPE’s outcome report concludes with a section on implications for the design of future AOT programs based on the evaluation’s results and prior research on AOT.

In addition to the ASPE evaluation, SAMHSA has also produced two outcome reports based on routine data submissions from AOT grantees. These reports cover fiscal years 2018 and 2023, and SAMHSA officials said they were transmitted to Congress in November 2019 and June 2024, respectively.[26] Grantees’ data submissions were based on surveys of participants they conducted at intake, every six months thereafter, and at program discharge.[27] Grantees surveyed participants about topics such as mental health and substance use, employment, housing, criminal justice status, and social connectedness.

Assessment Challenges

Based on our review, we determined that HHS’s assessments of the effects of the AOT grant program were inconclusive. This is because the ASPE and SAMHSA assessment efforts were both hampered by methodological challenges, many of which were inherent in the program and beyond their control. Challenges ASPE faced in conducting its evaluation, some of which were mentioned in its reports, included variation among the AOT grantee programs studied; reliance on self-reported data; participant nonresponse and risk of bias; and reduced ability to detect differences in outcomes between AOT and voluntary treatment programs.[28] SAMHSA also experienced some of these challenges.

Variation among grantee programs. Programs included in the ASPE evaluation varied in whether they enrolled participants with pending criminal charges and whether participants could be enrolled voluntarily.[29] Enrolling participants with pending criminal charges and enrolling participants voluntarily (or declining to order individuals to participate if they do not agree) pose challenges to evaluating AOT as defined as a civil, involuntary process. An evaluation that includes programs that vary significantly from the expected components of AOT programs, regardless of the results achieved, may not be relevant to the effectiveness of AOT. ASPE’s implementation report states that including participants with pending criminal changes can create significant differences in court orders, monitoring, and consequences for nonadherence between those with charges and those without them. The report also states that voluntary programs conflict with the underlying intent of AOT to provide treatment to those who would otherwise be unwilling to engage in treatment.

An ASPE official told us that despite differences among programs, the six grantees included in ASPE’s evaluation each had minimum elements defining AOT because they (1) served adults aged 18 years and older with serious mental illnesses who had been judged unlikely to be able to live safely in the community, and (2) involved the use of civil court orders to facilitate comprehensive mental health treatment, including procedures for monitoring treatment adherence. However, the official also told us that the variability among the selected programs reduced ASPE’s ability to assess the core concept of AOT. Representatives we interviewed from two of the stakeholder groups noted that variation among states’ laws, which govern the operation of AOT programs, contribute to the differences among AOT programs and make it difficult to evaluate AOT.

Self-reported data. Most of the data ASPE used in its evaluation were self-reported by program participants through interviews with AOT grantee program staff. Self-reported data are prone to bias, as individuals may not remember all incidents of interest, and they may be hesitant to candidly answer questions on sensitive topics such as substance use.[30] An ASPE official said that the use of self-reported measures was intended to give a voice to participant perspectives and experiences and that some measures, such as suicidal ideation, can only be reported by the participant themselves. ASPE also reported that grantees attempted to collect corroborating data, for example, from jails and hospitals.[31] However, the ASPE official also told us that the ability to collect such corroborating data depended heavily on relationships between grantees and external entities and that, even when data were collected, some were incomplete or could not be aggregated with other grantees’ data.

Regarding the use of AOT program staff to collect data, an ASPE official noted that interviewers’ familiarity with participants and clinical knowledge was needed to interview participants, particularly around sensitive topics such as suicidal ideation. However, a report on measuring AOT participant feedback by an advocacy group stated that using AOT program staff to survey participants may result in more positive feedback, because participants may feel uncomfortable sharing negative thoughts about the program with people affiliated with the program.[32]

Participant nonresponse and risk of bias. ASPE did not conduct a nonresponse bias analysis to determine whether AOT participants who did not agree to be interviewed differed systematically from those who did. Participation in data collection was voluntary, and not all participants provided data, also referred to as participant nonresponse. ASPE’s outcome report stated that 392 participant interviews were completed, but did not include a response rate—the number of AOT participants who completed an interview divided by the number of participants who were eligible to be interviewed.[33] ASPE’s primary contractor, RTI International, told us they had requested, but did not receive, information regarding the six selected AOT programs that would be necessary to calculate a response rate. Response rate information can be a useful indicator of the risk of bias, that is, the inability to generalize to the larger population of AOT participants. Moreover, ASPE did not conduct a nonresponse bias analysis, which can help assess the risk of bias and potentially adjust the data to account for nonresponse.[34]

Reduced ability to detect differences between AOT and voluntary treatment. ASPE’s analysis comparing AOT participants to individuals enrolled in voluntary treatment programs of similar intensity was limited to data from one grantee. The outcome report states that this analysis had a reduced ability to detect differences between the two groups, also referred to as low statistical power.[35] Factors such as small sample size, or a large amount of variation, can hamper the ability to detect true differences, particularly when differences are small. Similarly, the report notes that the cost avoidance analysis, which was based on data from three grantees, was affected by substantial variation among these grantees.[36]

The final section of ASPE’s outcome report includes implications for the design of future AOT programs based on the results of its evaluation and prior research on AOT. For example, based on the reduction in inpatient psychiatric hospitalizations in AOT participants relative to individuals receiving voluntary treatment for one grantee, the report states that individuals with repeated inpatient psychiatric hospitalizations may be better suited to AOT than to voluntary treatment.[37] It is unclear, however, whether analysis of data from one grantee is sufficient support for this statement, particularly given that ASPE states in the report that the evaluation results are not generalizable. In addition, suggesting that individuals with repeated inpatient psychiatric hospitalizations should receive AOT does not take into account other considerations SAMHSA and stakeholder groups told us were important for deciding who is a good candidate for AOT. SAMHSA officials and stakeholder group representatives we spoke with told us that AOT should be applied narrowly, including being restricted to individuals unable to engage in treatment voluntarily.

An ASPE official we spoke with noted that the implications for policy and practice included in the outcome report were not intended to be interpreted as best practices and that there is no one correct way to implement AOT programs.[38] The ASPE official we spoke with also said that the impact evaluation was not intended to provide conclusive evidence of AOT’s effectiveness, but rather to add to the evidence base, and should be viewed in the context of the scientific body of knowledge on AOT.

SAMHSA experienced some of the same challenges as ASPE and faced additional challenges related to the measures it used to generate its two outcome reports. Specifically, similar to ASPE, SAMHSA’s outcome reports were affected by variation among AOT programs, self-reported data, and participant nonresponse and risk of bias.[39] In addition, SAMHSA’s use of National Outcome Measures resulted in further challenges.[40] For example, the survey questions included in these measures were generally limited to experiences that occurred in the prior 30 days. For participants interviewed at a 6-month follow-up, this means that incidents that occurred during the program’s intervening months were not captured and could result in an undercount of certain outcomes, such as emergency room visits, hospitalizations, and arrests. SAMHSA officials told us the purpose of SAMHSA’s data collection is program monitoring, and that data do not provide clinical information on participants.

Many of the challenges ASPE and SAMHSA faced were inherent in the AOT program and beyond their control. For example, both agencies faced the challenge of studying AOT programs that were highly variable, and both experienced participant nonresponse, as some AOT participants declined to take part in their data collection efforts. These challenges are likely to persist, as state AOT laws will continue to vary, and participants can continue to decline to participate in data collection efforts. As a result of these and other challenges, the agencies’ assessments of the effectiveness of SAMHSA’s AOT grant program in achieving its intended purpose—to improve the health and social outcomes for individuals with serious mental illnesses—were inconclusive.

Agency Comments

We provided a copy of this draft report to HHS for review and comment. HHS provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Health and Human Services, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at rosenbergm@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. Other major contributors to this report are listed in appendix II.

Michelle B. Rosenberg

Director, Health Care

Appendix I: Assisted Outpatient Treatment (AOT) Grant Program Requirements Related to Participants’ Civil Rights

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) has included several requirements for grantees related to protecting the civil rights of participants as a condition of receiving federal funding for the AOT grant program. Specifically, in the 2024 notice of funding opportunity, SAMHSA required grantees to:

· Administer AOT programs in compliance with federal civil rights laws. This includes Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and the Americans with Disabilities Act.[41] Because serious mental illnesses are considered a disability, complying with those laws requires, among other things, that individuals be treated in the most integrated setting that is appropriate to their needs.[42]

· Develop protocols to ensure civil rights are protected. Grantees must develop protocols to ensure participants’ civil rights are protected, participants are educated about their rights, and proper legal procedures such as obtaining legal representation in court proceedings are being followed.

· Include criteria for court-ordered treatment as part of the treatment plan. Grantees must include criteria for court-ordered treatment as part of participants’ treatment plans, in addition to addressing medical, psychiatric, and social needs.[43] While the 2024 notice of funding opportunity does not define criteria for court-ordered treatment, one grantee we interviewed set criteria for discharging a participant based on their ability to maintain mood stability through natural supports, therapy, and medication so that they can successfully function at lower levels of care.

· Involve participants in treatment planning. Grantees must provide individualized, evidence-based treatment to participants using person-centered planning.[44] SAMHSA officials we spoke with confirmed that they expect grantees to honor participant preferences whenever possible, develop individualized treatment plans using person-centered practices, use multidisciplinary approaches, and adhere to the bounds of the civil court order.

Although not included as a requirement in the 2024 notice of funding opportunity, SAMHSA officials told us they also expect grantees to offer voluntary services to individuals prior to enrolling them in the AOT program. Officials explained that individuals who are willing to engage with treatment services would not generally meet AOT eligibility requirements and should not be enrolled in AOT. Officials added that for individuals who are voluntarily engaging in treatment services, SAMHSA requires grantees to provide referrals to other programs where individuals can be seen on a voluntary basis outside of the AOT program.

In addition to the requirements outlined in the 2024 notice of funding opportunity, SAMHSA officials said they educated 2024 grantees on the requirements to protect civil rights by providing additional written materials and in discussions as part of virtual weekly office hours that were offered at the beginning of the grant program. For example, SAMHSA published a question-and-answer document, which details SAMHSA’s standards for participant protections, including adequate consent procedures, discussion of risks and benefits, and privacy and confidentiality.[45] SAMHSA also held a virtual office hour session in November 2024 that discussed policies and protocols grantees are required to develop to protect participants’ civil and privacy rights. In addition, SAMHSA officials indicated they held office hours in May 2025 to provide support for AOT grantees.

GAO Contact

Michelle B. Rosenberg, rosenbergm@gao.gov.

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Karen Doran (Assistant Director), Hannah Locke (Analyst-in-Charge), Valerie Caracelli, Sonia Chakrabarty, Laura Elsberg, Xiaoyi Huang, Diona Martyn, Rithi Mulgaonker, Ravi Sharma, Roxanna Sun, and Sirin Yaemsiri made key contributions to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]See Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2023 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (Rockville, Md.: 2024).

[2]The Protecting Access to Medicare Act of 2014 defines AOT as “medically prescribed mental health treatment that a patient receives while living in a community under the terms of a law authorizing a State or local court to order such treatment.” Pub. L. No. 113-93, § 224(f)(1), 128 Stat. 1040, 1084.

AOT may also be referred to using other terms, such as involuntary outpatient commitment or mandatory outpatient treatment. AOT is distinct from mental health court or diversion programs. Mental health court and diversion programs serve individuals with mental health conditions who are facing criminal charges and offer them a voluntary option to suspend or waive criminal charges by agreeing to receive treatment. Those who choose not to participate may proceed to trial. By contrast, AOT is a civil rather than a criminal process and is involuntary for participants.

[3]Pub. L. No. 113-93, § 224, 128 Stat. at 1083.

[4]Pub. L. No. 113-93, § 224(e), 128 Stat. at 1083. Specifically, the law required HHS to submit reports containing information on cost savings associated with the AOT grant program; public health outcomes such as participant mortality, suicide, substance use, hospitalization, and service utilization; rates of incarceration; rates of homelessness; and program satisfaction.

[5]See for example Henry J. Steadman et al., “Assessing the New York City Involuntary Outpatient Commitment Pilot Program,” Psychiatric Services, vol. 52, no. 3 (2001) and Marvin S. Swartz et al., “A Randomized Controlled Trial of Outpatient Commitment in North Carolina,” Psychiatric Services, vol. 52, no. 3 (2001).

[6]Pub. L. No. 117–328, § 1123(b)(2), 136 Stat. 4459, 5653 (2022).

[7]The provision also requires us to identify best practices used to ensure AOT program participants receive treatment in the least restrictive environment that is clinically appropriate consistent with federal and state law. Pub. L. No. 117-328, § 1123(b)(2)(B), 136 Stat. at 5654. We therefore reviewed SAMHSA’s requirements for grantees related to civil rights protections as part of our work. See appendix I.

[8]ASPE’s evaluation examined the policies, practices, and outcomes of a group of selected AOT grant programs. For the purposes of this report, we refer to ASPE as the author of the reports generated from its evaluation. See Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, “Evaluation of the Assisted Outpatient Treatment Grant Program for Individuals with Serious Mental Illness” (Washington, D.C.: Aug. 8, 2024), https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/evaluation-aot-grant-program-individuals-smi.

On March 27, 2025, HHS announced that it would be restructuring the department, including by consolidating SAMHSA into a new Administration for a Healthy America and ASPE into a new Office of Strategy. See Office of the Assistant Secretary for Public Affairs, HHS Announces Transformation to Make America Healthy Again. In May, several states filed a lawsuit challenging the March 27 announcement; litigation is ongoing. See New York v. Kennedy, No. 25-cv-00196 (D.R.I. May, 5, 2025). As of June 2025, the transition to a new structure had not occurred and accordingly, we refer to the agencies as SAMHSA and ASPE throughout this report.

[9]We requested and received standard errors, which are a measure of the uncertainty associated with an estimate, for some of ASPE’s analyses. We used standard errors provided by ASPE’s contractor to calculate relative standard errors, which are calculated by dividing the standard error of an estimate by the estimate itself, then multiplying that result by 100. Relative standard errors for most measures indicated that estimates may be unreliable.

[10]Pub. L. No. 111-148, 124 Stat. 119 (2010). We considered states’ Medicaid expansion status because Medicaid is the largest payer of behavioral health services and whether states expanded Medicaid could affect funding available for services for individuals with serious mental illnesses.

[11]See Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Evaluation of the Assisted Outpatient Treatment Grant Program for Individuals with Serious Mental Illness: Outcome Evaluation Report, (Washington, D.C.: 2024). As of July 2024, 48 states and the District of Columbia authorize AOT; Connecticut and Massachusetts do not. For purposes of this report, the District of Columbia is included in the mention of states. In addition, U.S. territories also may authorize some form of AOT.

[12]Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Civil Commitment and the Mental Health Care Continuum: Historical Trends and Principles for Law and Practice, (Rockville, Md.: 2019).

[13]Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Evaluation of the Assisted Outpatient Treatment Grant Program for Individuals with Serious Mental Illness: Implementation Report, (Washington, D.C.: 2024). At the time ASPE conducted its evaluation, Maryland had not yet enacted a law authorizing AOT.

[14]Marcia L. Meldrum et al., “Implementation Status of Assisted Outpatient Treatment Programs: A National Survey,” Psychiatric Services, vol. 67, no. 6 (2016).

[15]Pub. L. No. 113-93, § 224(f)(2), 128 Stat. 1040, 1084. SAMHSA awarded a grant to an entity located in Massachusetts as part of the 2020 grant cycle. In its notice of funding opportunity for the 2024 grant cycle and the associated frequently asked questions document, SAMHSA clarified that Connecticut and Massachusetts do not have legislative authority for AOT and applicants from those states will be screened out.

[16]Pub. L. No. 113-93, § 224(c)(1), 128 Stat. at 1083. SAMHSA awarded grants to three entities twice, once as part of the 2016 grant cycle and a second time as part of the 2020 grant cycle. SAMHSA officials we interviewed did not provide an explanation as to why these awards—which preceded the officials’ time administering the program—were made.

[17]Individuals with disabilities, including serious mental illnesses, are entitled to civil rights protections under the Americans with Disabilities Act, including receiving community-based services that enable them to live in the most integrated setting appropriate to their needs. See Olmstead v. L.C., 527 U.S. 581 (1999).

[18]Since 2016, SAMHSA has received 94 applications and awarded 66 grants, including two each to three grantees in Alabama, Florida, and Oklahoma. Three other grantees later gave up their grants, resulting in a total of 63 grants.

[19]Henry J. Steadman et al., “New York City Involuntary Outpatient Commitment Pilot Program” and Marvin S. Swartz et al., “Outpatient Commitment in North Carolina.”

[20]Selection bias may occur when a subset of the population has no chance, or an unknown chance, of being selected for a sample, resulting in a sample that is not representative of the population. For example, positive outcomes among program participants may be because results came from individuals who remained in the program and did not include those who left.

[21]M. S. Swartz, J. W. Swanson, H. J. Steadman, P. C. Robbins, and J. Monahan, New York State Assisted Outpatient Treatment Program Evaluation, Duke University School of Medicine (Durham, N.C.: June 2009) and Bruce G. Link et al., “Arrest Outcomes Associated with Outpatient Commitment in New York State,” Psychiatric Services, vol. 62, no. 5 (2011).

[22]See Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, “Evaluation of the Assisted Outpatient Treatment Grant Program.” ASPE also published a summary report that provides an overview of the implementation and outcome reports and an issue brief on assessing the level of judicial involvement in AOT programs.

[23]SAMHSA’s 2016 notice of funding opportunity for the AOT grant program directs applicants to describe how they will inform participants that they may receive services even if they chose to not participate in or complete the data collection component of the program.

[24]See Kathryn McCollister et al., “Monetary Conversion Factors for Economic Evaluations of Substance Use Disorders,” Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, vol. 81, (2017).

[25]Bridge team services comprise intensive follow-up and support services provided by a multidisciplinary team to aid in the transition between hospitalization and outpatient services.

[26]The Protecting Access to Medicare Act of 2014 required SAMHSA to submit reports to Congress annually for fiscal years 2016 through 2018. Pub. L. No. 113-93, § 224(e), 128 Stat. 1040, 1083. Subsequent laws extended annual reporting through fiscal year 2023 and biennial reporting after that. See 21st Century Cures Act, Pub. L. No. 114-255, § 9014(1), 130 Stat. 1033, 1245 (2016); Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023, Pub. L. No. 117-328, § 1123(b)(1)(B)(i), 136 Stat. 4459, 5653 (2022). As of July 2024, SAMHSA officials told us they had submitted four reports to Congress covering fiscal years 2016, 2017, 2018, and 2023. SAMHSA officials said the reports were submitted to Congress but have not been publicly released. SAMHSA’s reports consist of a brief initial report on funding and the selection of grantees for 2016, a report on program implementation for 2017, and the two reports on outcomes for 2018 and 2023. SAMHSA officials we spoke with told us they had no record of preparing or submitting reports for fiscal years 2019 through 2022, which predated these officials’ time administering the program.

[27]AOT grantees are required to submit National Outcome Measures data through SAMHSA’s Performance Accountability and Reporting System. According to SAMHSA officials, the agency chose these measures as the basis for its reports to Congress because they are the agency-wide mechanism to gather data from all discretionary grant programs (such as AOT). In addition, these measures contain information on the topics SAMHSA is required to include in the reports to Congress, according to agency officials.

[28]In addition to these challenges, our review of documentation describing ASPE’s analysis of participants’ health and social outcomes from intake to 6- and 12-month follow-up suggests that some of the observed differences may be statistically unreliable. As mentioned previously, we used standard errors, which are a measure of the uncertainty of an estimate, to calculate relative standard errors. We found that, among 16 measures reported by ASPE, relative standard errors for the differences were 30 percent or higher for 12 measures. A relative standard error greater than 30 percent has been used as a criterion by HHS agencies, such as the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, to indicate an estimate is statistically unreliable. See Richard J. Klein, Suzanne E. Proctor, Manon A. Boudreault, and Kathleen M. Turczyn, Healthy People 2010 Criteria for Data Suppression, Statistical Notes, no. 24 (Hyattsville, Md.: National Center for Health Statistics, July 2002).

[29]These issues were not unique to the 2016 grantee programs included in ASPE’s evaluation. Among the six selected 2020 AOT programs we interviewed, five accepted voluntary participants into their programs, including three programs that accepted participants without a court order. An official from one program that accepted voluntary participants said that using involuntary court orders made it harder to engage participants, because they disliked feeling they were being forced into treatment. The official added that if individuals are forced to attend therapy, they receive little benefit from it. Four of the programs allowed participants with pending criminal charges to enroll, including two that suspended or waived criminal charges contingent on participation in the AOT program. Officials from one of these two programs told us that individuals who did not have pending charges were harder to serve, because they did not have the incentive of getting charges dropped to persuade them to adhere to treatment.

[30]An official from a mental health advocacy group we spoke with noted that survey responses can be affected when topics discussed are sensitive, embarrassing, or associated with judgment. In addition, participants may be reluctant to provide information when there are real or perceived negative consequences associated with their responses. For example, the official noted that participants may be concerned that their answers could affect how long they are required to remain in the program.

[31]Where available, ASPE used corroborating data, such as administrative records of inpatient psychiatric stays and arrest records, to conduct confirmatory analyses. ASPE found that administrative records of inpatient psychiatric stays showed substantially fewer stays than were reported by AOT participants. However, the results using administrative records and results using self-reported data both showed a significant change from intake to follow-up. For arrests, ASPE did not find a significant change from intake to follow-up using data from jails, while the analysis using self-reported arrests did show a significant change. However, ASPE noted that both arrest data from jails and self-reported arrest data showed a similar pattern of change over time.

[32]See Treatment Advocacy Center, Measuring Experiences: An Evaluation of AOT Participant Satisfaction, (Arlington, Va.: 2023), 22. The Treatment Advocacy Center is an organization that advocates for the expansion of AOT programs.

[33]While response rates may be calculated in different ways, one example is dividing the number of completed surveys by the number of eligible respondents who were selected to participate. See Office of Management and Budget, Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, Questions and Answers When Designing Surveys for Information Collections (Washington, D.C.: 2016).

[34]According to the Office of Management and Budget, a nonresponse bias analysis is needed when the expected unit response rate is less than 80 percent. Nonresponse refers specifically to unit nonresponse, which occurs when a respondent fails to fill out or return a survey. See Office of Management and Budget, Statistical Policy Directive No. 2: Standards and Guidelines for Statistical Surveys (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 2006).

[35]For this analysis and the larger analysis of differences between intake and follow-up for all six grantees, ASPE conducted additional analysis to determine the strength of the evidence using Bayes factors. ASPE used Bayes factors in conjunction with more traditional statistical methods to distinguish between results that were not significant because AOT was not associated with a change in outcomes versus results that were not significant due to low statistical power to detect differences.

[36]The analysis compared the cost per AOT participant with the estimated cost avoided by fewer psychiatric emergency room visits and fewer and shorter psychiatric inpatient hospitalizations. Although the analysis suggested potential cost savings, results were not statistically significant.

[37]ASPE reported that for AOT participants from one grantee, 71.3 percent were hospitalized during the preceding 6 months at intake, compared with 16.6 percent at the 6-month follow-up. For individuals engaged in voluntary treatment, 68.8 percent had been hospitalized during the preceding 6 months at intake, compared with 15.1 percent at the 6-month follow-up.

[38]SAMHSA officials said they found ASPE’s evaluation helpful and, as of November 2024, they were considering making changes to future notices of funding opportunity based on its results. For example, based on information on AOT program sustainability in ASPE’s outcome report, SAMHSA officials said the next notice of funding opportunity will include a requirement for grantees to develop a plan to determine whether they can sustain their programs after the conclusion of SAMHSA funding.

Officials from four of the six 2020 AOT grantees we interviewed said they had not continued their programs after their SAMHSA grant funding ended.

[39]SAMHSA reported a 65 percent response rate in its 2018 outcome report, but did not report results of a nonresponse bias analysis. SAMHSA’s report, however, states that participant nonresponse means that outcomes presented may not be generalizable to all AOT participants. The agency also stated that the population not reflected in the data may be less stable and harder to reach, meaning that they may have had worse outcomes than those who did respond. SAMHSA did not report a response rate in its 2023 report, but officials told us the response rate was 69 percent.

[40]We and others have previously reported on limitations of National Outcome Measures data, including the inability to determine the unique effect of the SAMHSA program being measured, because program participants may be receiving interventions from other programs; potential bias due to low follow-up rates or because individuals who participated in follow-up interviews may be different from individuals who did not; and difficulty interpreting the effect of the SAMHSA program on outcomes due lack of comparison groups. See GAO, Opioid Use Disorder: Opportunities to Improve Assessments of State Opioid Response Grant Program, GAO‑22‑104520 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 9, 2021).

In addition, in its evaluation implementation report, ASPE noted that relying solely on National Outcome Measures data would severely limit the ability to comment on the effectiveness of AOT.

[41]See 29 U.S.C. § 794; 42 U.S.C. ch. 126.

[42]See 42 U.S.C. § 12102; see also 45 C.F.R. § 84.76(b); 28 C.F.R. § 35.130(d).

[43]The 2024 notice of funding opportunity required grantees to include criteria for court-ordered treatment, rather than criteria for completion of court-ordered treatment as specified in the Protecting Access to Medicare Act of 2014. Pub. L. No. 113-93, § 224(d)(2)(A), 128 Stat. 1040, 1083. SAMHSA officials said that they removed the words “completion of” from the phrase in the 2024 notice of funding opportunity to separate the legal requirement for length of treatment that is derived from state AOT laws from the treatment plan. Officials clarified that state law determines the maximum amount of time an individual can be under an AOT court order, not the court-ordered treatment plan.

[44]SAMHSA defines person-centered planning as a process led by the individual receiving care, in collaboration with certain treatment team members, that results in the co-creation of an action or treatment plan centered around the individual’s most valued priorities and wellness goals. See Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Person-Centered Planning, PEP24-01-002 (Rockville, Md.: 2024)

[45]See Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) SM-24-006 Assisted Outpatient Treatment (AOT) Notice of Funding Opportunity (NOFO) (Rockville, Md.: 2024). SAMHSA also provided a guide on developing competitive grant applications that includes a chapter on participant protections and confidentiality. See Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Developing a Competitive SAMHSA Grant Application (Rockville, Md.: Sept. 2023), 41-44.