DOD CONTRACTING

Opportunities Exist to Improve Pilot Program for Employee-Owned Businesses

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑107531. For more information, contact Mona Sehgal at (202) 512-4841 or sehgalm@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑107531, a report to congressional committees

Opportunities Exist to Improve Pilot Program for Employee-Owned Businesses

Why GAO Did This Study

Committees in Congress have stated that ESOP corporations can help DOD increase the number and range of companies it contracts with to foster innovation and broaden the defense industrial base. Congress authorized DOD to establish a pilot program to award follow-on contracts, on a noncompetitive basis, to contractors that are S corporations wholly owned by an ESOP. DOD awarded contracts valued collectively at over $450 million under the program, which expires in 2029.

The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2022 includes a provision for GAO to review DOD’s ESOP pilot program activities. This report assesses the extent to which (1) DOD has effectively managed the ESOP pilot program, and (2) the program aligns with leading practices for pilot program design.

GAO reviewed relevant legislation, pilot program requirements, and contract documentation; interviewed DOD officials and contractor representatives; and compared DOD’s pilot program plans and efforts against GAO leading practices for pilot program design.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making six recommendations to DOD, including that it provides additional guidance for contracting officials in implementing the ESOP pilot program, and ensures that the ESOP pilot program better aligns with the five leading practices for pilot program design. DOD concurred with all of GAO’s recommendations.

What GAO Found

The Department of Defense (DOD) awarded eight contracts under its employee stock ownership plan (ESOP) pilot program. ESOPs are benefit plans in which company stock held by a trust is allocated to employees as a retirement benefit. DOD issued a memorandum in November 2022 outlining the parameters of the pilot, but did not provide contracting officials with adequate guidance, such as collecting robust data to determine a contractor’s eligibility. GAO found evidence that DOD awarded a pilot program contract to an ineligible contractor. DOD issued updated guidance in December 2024 that included ways for contracting officers to determine a contractor’s eligibility. However, the updated guidance did not provide other information on key aspects of the program that could better position contracting officers to properly implement the pilot program.

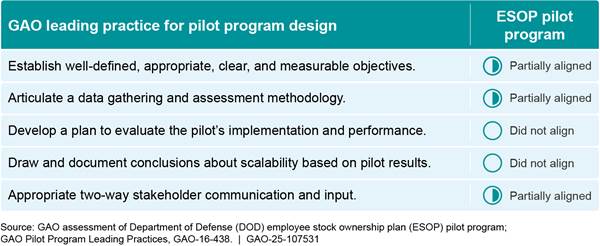

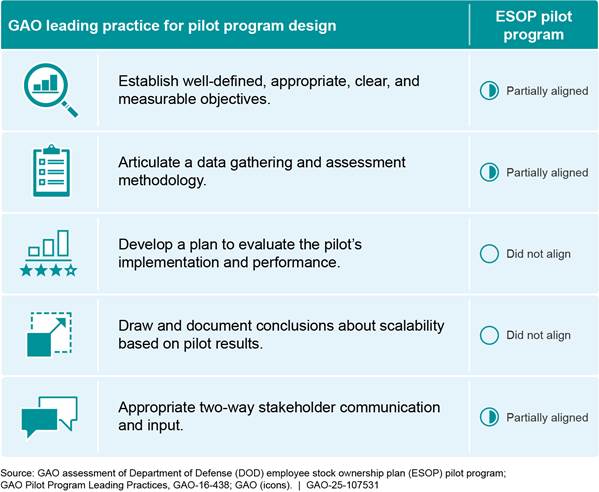

Furthermore, DOD’s efforts to develop and implement the pilot program do not fully align with GAO’s leading practices for pilot program design. These practices state that a pilot program should be designed to collect data for program officials to make well informed decisions.

DOD’s efforts partially align with three of the leading practices:

· DOD officials stated that one of their priorities was to expand the defense industrial base but did not identify any measurable objectives.

· DOD described the type of data needed to assess the pilot program, but did not clearly articulate an assessment methodology.

· DOD received some feedback from contracting officers and contractors and intends to solicit additional input, but does not yet have a plan for doing so.

DOD’s efforts do not align with the other two leading practices. First, DOD has not developed an evaluation plan. Second, DOD does not know the number of ESOP corporations that could benefit from the program—information needed to make a scalability determination. Without a well-designed pilot program that fully aligns with leading practices, DOD will not have data to identify program successes and challenges to inform future phases. But DOD still has an opportunity to make improvements, including implementing leading practices.

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Abbreviations

|

DFARS |

Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement |

|

DOD |

Department of Defense |

|

DPCAP |

Defense Pricing, Contracting, and Acquisition Policy Office |

|

ESOP |

employee stock ownership plan |

|

NDAA |

National Defense Authorization Act |

March 20, 2025

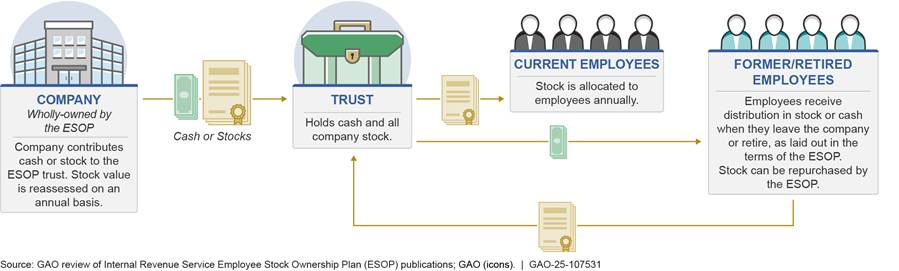

Congressional Committees

The Department of Defense (DOD) has longstanding efforts to increase the number and range of companies that it contracts with to foster innovation and broaden the defense industrial base. Committees in Congress have stated they believe that companies with employee stock ownership plans (ESOP) have the potential to help DOD achieve these goals.[1] ESOPs are employee benefit plans in which company stock held by a trust is allocated to employees as a retirement benefit. The National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year 2022 (a) authorized DOD to establish a 5-year pilot program to award noncompetitive follow-on contracts to wholly-owned ESOP S corporations, and (b) required DOD to collect and analyze data to inform program and policy decisions.[2] The NDAA for Fiscal Year 2024 subsequently amended aspects of the pilot program, including extending the pilot program to December 2029.[3]

The NDAA for Fiscal Year 2022 also includes a provision for us to review DOD’s ESOP pilot program activities. This report assesses the extent to which (1) DOD has effectively managed the ESOP pilot program, and (2) DOD’s ESOP pilot program aligns with leading practices for pilot program design.

To assess the extent to which DOD effectively managed the ESOP pilot program, we reviewed the authorizing legislation and the Defense Pricing, Contracting, and Acquisition Policy (DPCAP) office’s November 2022 memorandum that outlined the parameters of the pilot program and provided implementing guidance to DOD contracting personnel. We also reviewed DPCAP’s December 2024 memorandum that provided additional guidance and templates for the second phase of the ESOP pilot program. We interviewed DPCAP officials who manage the pilot program to identify their goals and any planned updates for the pilot program. Additionally, we reviewed applications for all eight of the contracts awarded under the pilot program. Specifically, we reviewed documentation that a company meets the definition of a qualified business, available performance ratings on predecessor contracts, and feedback on the pilot program from the contracting officers and contractors. We also reviewed contract documents, including the contractors’ current and predecessor contracts, as well as documents justifying the reasons for the use of noncompetitive contract awards. We interviewed officials from the eight contractors that were awarded follow-on contracts under the pilot program to obtain their views on the pilot program. Finally, we asked contracting officers who participated in the first phase of the pilot program about their experiences with the pilot program, including their knowledge of the pilot program and ESOPs in general. We assessed this information against criteria in Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, specifically those related to documenting internal control responsibilities in policies and communicating quality information.[4]

To determine whether DOD’s pilot program aligns with our leading practices for pilot program design, we reviewed documentation, such as the November 2022 memorandum outlining the program, and interviewed officials from DPCAP about how they developed and implemented the pilot program. We assessed their plans and efforts against five leading practices for pilot program design we identified in our prior work. These include activities such as establishing objectives and collecting information to determine whether a program should be continued. We shared these leading practices with DPCAP officials so they would know our assessment methodology and to give them an opportunity to provide supporting documentation of their efforts.[5]

We conducted this performance audit from April 2024 to March 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Employee Stock Ownership Plans

Companies can be wholly or partially owned by an ESOP, which is an employee benefit plan designed to invest primarily in shares of the sponsoring company.[6] ESOPs can also invest in other assets, such as other companies’ stocks or government securities. ESOPs are managed by a trustee who has fiduciary responsibilities for the ESOP. In other words, the trustee has legal ownership of the company’s stock and must make decisions and act in the best interests of the plan participants and beneficiaries, such as employees or retirees. The following figure shows the relationship between an ESOP corporation and employees.

The length of time it takes to become a wholly-owned ESOP varies. According to some of the contractors participating in DOD’s ESOP pilot program, this process can take a few months to several years. The National Center for Employee Ownership told us in August 2024 that it estimates that there are approximately 470 companies in the United States that are 100 percent wholly owned through an ESOP.[7]

NDAA Requirements for ESOP Pilot Program

The NDAA for Fiscal Year 2022 authorized DOD to establish a pilot program to award noncompetitive follow-on contracts to existing contractors that are wholly-owned ESOP S corporations. Subsequently, in the NDAA for Fiscal Year 2024, Congress modified requirements to DOD’s pilot program. Table 1 shows the statutory criteria for contractors to participate in the program.

Table 1: Eligibility Requirements for the Department of Defense’s Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP) Pilot Program

|

The business must be an S corporation wholly-owned through an employee stock ownership plan.a |

|

The follow-on contract must be for the same products or services, or for substantially similar products or services procured under the contractor’s prior contract. Only one follow-on contract per predecessor contract can be awarded unless a waiver is provided. |

|

The business must have a rating of satisfactory or better in the applicable past performance database. |

|

No more than 50 percent of the amount paid under the follow-on contract may be expended on subcontracts unless the subcontractor is an S corporation wholly owned by an ESOP, or the needed materials are not available from a company that is wholly owned by an ESOP. |

Source: National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year 2022 as amended by the NDAA for Fiscal Year 2024. | GAO‑25‑107531

aS corporations elect to pass corporate income, losses, deductions, and credits to their shareholders for federal tax purposes. Shareholders of S corporations report the pass-through of income and losses on their personal tax returns and are assessed tax at their individual income tax rates.

The act also required us to report whether there are any other acquisition authorities that could be used to incentivize a corporation to become a wholly-owned ESOP. DPCAP officials stated that they are not aware of any such acquisition authorities.

Implementation of the ESOP Pilot Program

Following the enactment of the NDAA for Fiscal Year 2022, DOD assigned responsibility for managing and overseeing the pilot program to the Principal Director, DPCAP, who reports to the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment. DPCAP issued a memorandum in November 2022 to guide the implementation of the pilot program. We refer to this initiation as phase 1 of the pilot program. The memorandum authorized up to nine contract awards under the pilot and outlined documentation requirements that contracting officers had to prepare and submit to DCPAP for each contractor that wanted to participate in the pilot program. DPCAP issued an updated memorandum in December 2024, which we refer to as the beginning of phase 2 of the pilot program. See table 2 for the updated documentation requirements for the pilot program.

Table 2: Contracting Officers Documentation Requirements for the Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP) Pilot Program Participation

|

Prepare a justification and approval document for each contract approved for award under the pilot program. |

|

Submit an ESOP Pilot application package to the Defense Pricing, Contracting, and Acquisition Policy Office, which includes the ESOP Pilot application form and supporting documentation, such as documentation supporting that the contractor is an S Corporation wholly-owned by an ESOP and past performance documentation. The application form also asks contracting officers to respond to questions regarding requirements to participate in the pilot program. |

|

Submit feedback on the program to the Defense Pricing, Contracting, and Acquisition Policy Office via a data collection instrument upon completion of 6 months of contractor performance or no later than 30 days after the contract end date, whichever is sooner. |

Source: Department of Defense December 2024 Memorandum on Pilot Program to Incentivize Contracting with Employee-Owned Businesses. | GAO‑25‑107531

Once applications were received, DPCAP reviewed and approved which contractors would be awarded follow-on contracts. DPCAP officials stated that they approved the applications on a first-come, first-served basis to contractors that met pilot program criteria. DOD awarded eight contracts in the first phase of the pilot program. Table 3 summarizes five of these contracts awarded under the ESOP pilot program that had publicly available data, as of March 2025.

Table 3: Description of Contracts Awarded Under the Department of Defense Employee Stock Ownership Plan Pilot Program, as of March 2025

|

Description of contract |

Product and service code |

Estimated contract value at time of awarda |

|

Leadership coaching sessions within the Department of Defense Educational Activity |

Professional Support Services: Other |

$570,000 |

|

Technical and functional support services for Washington Headquarters Services |

Professional Support Services: Program and Management Support |

$6 million |

|

Engineering, analysis, and test support for the Department of the Navy |

National Defense Research and Development Services: Experimental Development |

$29 million |

|

Software Services to the Defense Health Agency to transform existing infrastructure into modern software |

Information Technology and Telecom: Business Application Development Support Services |

$78 million |

|

Acquisition and financial services to Space Systems Command |

National Defense Research and Development Services: Administrative Expenses |

$131 million |

Source: GAO review of employee stock ownership plan pilot program contract documents. | GAO‑25‑107531

Note: The Department of Defense awarded eight contracts in the first phase of the pilot program. However, the Federal Procurement Data System did not include information for three of them.

aContract value includes base and all option years.

All eight contractors self-certified as wholly-owned ESOP corporations and indicated that they had operated as a wholly-owned ESOP from 4 to 26 years. Six of the eight contracts were awarded to small businesses and two were awarded to large businesses.

Following amendments to the pilot program in the Fiscal Year 2024 NDAA, DOD proposed a Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement (DFARS) rule on May 30, 2024, outlining the requirements for the pilot program.[8] DOD issued the final rule updating the DFARS on October 10, 2024.[9]

GAO Leading Practices for Pilot Program Design

Our prior work identified five leading practices for pilot program design:[10]

· Develop clear and measurable objectives. A well-designed pilot program should have well-defined, appropriate, clear, and measurable objectives. This will help ensure that appropriate evaluation data are collected from the start of the pilot. Objectives are needed to develop an assessment methodology to help determine what data and information will be collected. Objectives also inform the evaluation plan because performance of the pilot should be evaluated against them.

· Clearly articulate assessment methodology. Key features of a clearly articulated methodology include a strategy for comparing the pilot implementation and results with other efforts, a clear plan that details the type and source of data necessary to evaluate the pilot, and methods for data collection, including the timing and frequency.

· Develop a plan to evaluate pilot results. An evaluation plan should be developed to track the pilot program’s implementation and performance, and evaluate results to draw conclusions on whether, how, and when to integrate pilot activities into overall efforts.

· Ensure scalability of pilot design. The purpose of a pilot is to generally inform a decision on whether and how to implement a new approach in a broader context—or in other words, whether the pilot can be scaled up or increased in size to a larger number of projects over the long term. Criteria to measure scalability should provide evidence that the target population is known.

· Ensure appropriate two-way stakeholder communication. Appropriate two-way stakeholder communication and input should occur at all stages of the pilot, including design, implementation, data gathering, and assessment. To that end, it is critical that agencies identify relevant stakeholders and communicate with them early and often. This process may include communication with both external and internal stakeholders.

These practices enhance the quality, credibility, and usefulness of pilot program evaluations and help ensure that time and resources are used effectively. While each of the five practices serves a purpose on its own, taken together, they form a framework for effective pilot design.

DOD’s Guidance Did Not Address Key Aspects of the Pilot Program

DPCAP’s November 2022 memorandum provided guidance to contracting officers on pilot program participation requirements and limitations but did not include information that would have helped inform them about key aspects of the pilot program. The memorandum, which DPCAP distributed to commands and published it on its web page, introduced the pilot program but did not provide guidance on ways to determine whether a contractor met eligibility requirements. In our interviews with contracting officers for the eight follow-on contracts awarded under the pilot program, we found the officers had limited knowledge on ESOPs. Additionally, we found that contracting officers lacked guidance on what documentation to collect from contractors to ensure they met program eligibility requirements.

· Limited knowledge about ESOPs. DPCAP did not provide contracting officers with adequate information about ESOPs. For example, all eight contracting officers who participated in the first phase of the program stated that they were unfamiliar with or had very little knowledge of what an ESOP was prior to the start of the pilot program. In December 2024, DPCAP issued an updated memorandum that included ways to determine if a company is a wholly-owned ESOP, as discussed below. However, while it included some relevant characteristics of a qualified business, such as that a business has to be a S corporation that is wholly-owned by an ESOP, the updated memorandum still did not clarify what ESOPs are. For example, the memorandum did not mention that a wholly-owned ESOP is owned through a trust and not through an individual.

· Lack of guidance about what ESOP documentation to collect. In its November 2022 memorandum, DPCAP did not identify the type of documentation that contracting officers should obtain to determine a contractor’s ESOP status. However, the memorandum required contracting officers to obtain a representation of this status. As a result of DPCAP not identifying the type of documentation required, the self-certifications from the eight contractors attesting to their wholly-owned ESOP status varied:

· Three contractors provided attestations on company letterhead signed by company representatives.

· Two contractors provided attestations on their ESOP status via email.

· One contractor submitted tax forms that showed its ESOP status.

· One contractor included a shareholder certification showing the corporation is a wholly-owned ESOP, signed by a witness.

· One contractor did not provide a self-certification, but the contract file included the company’s web page that stated it was a 100 percent wholly-owned ESOP.

Furthermore, we found that one of the contractors participating in the program may not be wholly owned by an ESOP. The contractor established its ESOP status via an email—signed by the Chief Operating Officer—sent to the contracting officer stating that it was a wholly-owned ESOP. However, other documentation shows that this contractor is listed as a woman-owned small business.[11] In order to be a woman-owned small business, a company must be directly owned rather than owned through a trust—the ownership mechanism for an ESOP.[12] Therefore, a company cannot be both a wholly-owned ESOP and a woman-owned small business. When we asked about the eligibility of the company, DPCAP officials told us they would assess the contractor’s ESOP status. In December 2024, an official told us that DOD determined that this contractor is not an ESOP and was not eligible to be awarded a contract under the pilot program. The contract’s current period of performance will end in March 2025 and DOD officials stated that they will not continue the contract beyond that.[13]

To help clarify this issue for future awards, DPCAP’s December 2024 guidance includes information that states that a woman-owned business cannot qualify as a wholly-owned ESOP. The updated guidance, however, does not make clear that companies that are eligible for other socioeconomic programs may also be precluded from being a wholly-owned ESOP for similar reasons. For example, a veteran-owned or service-disabled-veteran-owned business has to be owned directly by a qualifying veteran, and not through a trust as is the case for an ESOP. These businesses therefore would not qualify as wholly-owned ESOPs.

DPCAP’s 2022 memorandum did not provide specific guidance about what type of documentation contracting officers should obtain to determine a contractor’s eligibility, such as asking for a certified list of shareholders. DPCAP officials stated that they relied on self-certifications because DOD is not permitted to independently access federal tax information, which could confirm a business’s ESOP status.[14] This lack of guidance, however, resulted in limited information to determine ESOP status and created a risk that contracting officers would unintentionally award contracts to ineligible contractors. To mitigate this risk, DPCAP’s 2024 memorandum suggests several documents that contracting officers could collect to determine a contractor’s ESOP status. These documents include, for example, trust agreements, trustee certifications, or annual ESOP reports.

DPCAP officials stated that DOD can face negative consequences if an ineligible company is awarded a contract under the pilot program. They explained that if a contractor is found ineligible for a contract award and that contract is then terminated, the agency would need to delay necessary work while seeking a new contractor. DPCAP officials also told us that the government can take action against companies that willfully misrepresent their ESOP status.[15]

Federal internal controls state that management should document and internally communicate the necessary quality information, including policies and procedures, to achieve the entity’s objectives—in this case, the information needed for DPCAP’s contracting officers to properly implement the pilot program.[16] While DPCAP’s updated guidance included information on additional documents that contracting officers can collect to determine a contractor’s ESOP status, the guidance does not include other key information. Such key information includes examples of other company ownership structures that would make contractors ineligible for the pilot program, as well as clarify what an ESOP is and characteristics that contracting officers could identify when determining whether a company is a wholly-owned ESOP. Providing such additional guidance to contracting officers would better position them to implement the program.

DOD ESOP Pilot Program Does Not Fully Align with Leading Practices

DPCAP’s approach to managing and evaluating the ESOP program does not fully align with our leading practices for pilot program design. A pilot program is designed to collect information needed for program officials and policymakers to evaluate the potential effectiveness of a new initiative and make well-informed decisions. Our assessment showed that DPCAP partially aligned with three leading practices but did not align with two others, as shown in figure 2.

Note: For this analysis, “fully aligns” means GAO found evidence that fully or significantly satisfied the leading practice; “partially aligns” means GAO found evidence that satisfied some, but not a significant portion of, the leading practice; and “does not align” means GAO found little or no evidence that satisfied the leading practice.

Clear and measurable objectives: partially aligned. DPCAP stated it had a broad objective, but it did not develop specific measurable objectives for the pilot program. This leading practice emphasizes that broad pilot objectives should be translated into specific researchable questions that articulate what will be assessed. DPCAP officials stated they interpreted that Congress’s objective of the pilot program was to incentivize more businesses to become wholly-owned ESOP corporations.[17] Officials stated that measuring this objective would be difficult, especially because becoming a wholly-owned ESOP is a lengthy legal process. Secondarily, DPCAP officials stated that the pilot program may help meet priorities in the National Defense Strategy by reducing consolidation of the defense industrial base. Without measurable objectives, however, DPCAP cannot assess whether the program is an effective approach to achieving either of these broad objectives.

Establishing well-defined objectives is a critical first step to effectively implementing the subsequent leading practices for a pilot program’s design. Objectives are needed to: (a) develop an assessment methodology to help determine the data and information that will be collected, (b) inform the evaluation plan, as performance of the pilot should be evaluated against these objectives, and (c) assess the scalability of the pilot to help inform decisions on whether and how to incorporate it into broader efforts.

Assessment methodology: partially aligned. DPCAP identified data and feedback that it wanted to collect, but it did not articulate an assessment methodology. For example, DPCAP’s November 2022 memorandum required contracting officers to agree to submit formal feedback on the benefits and challenges of the pilot program.[18] For each of the contracts awarded, DPCAP used a standardized questionnaire to collect information on the experiences of both contracting officers and contractors. Specifically, the questionnaire asked how long the contractor had been a wholly-owned ESOP corporation, and whether the contractor’s corporate structures affected its abilities to contract with DOD or obtain needed capital to fund certain projects. Contracting officers had to report on the contractor’s performance, their views on the advantages and disadvantages of the pilot program, and any lessons learned about the pilot that DPCAP should consider. DPCAP’s December 2024 memorandum requires a similar questionnaire. The data DPCAP collected from this approach, while potentially providing useful insights, do not comprise an assessment methodology that would help to assess if the program is meeting its intended objectives. Articulating such a methodology would better enable DPCAP to ensure it is collecting and using the most relevant data to evaluate the pilot program.

Evaluation plan: did not align. DPCAP has not developed a plan to evaluate the results of the pilot program. Without an evaluation plan, DPCAP will not have data-driven results that show the successes and challenges of the pilot, and in turn, how the pilot can be incorporated into broader efforts.

Program scalability: did not align. DPCAP has considered where the program fits into contracting preference programs but has not taken steps to determine whether the program could be expanded. As part of the rulemaking process, DPCAP officials stated that they discussed how this pilot program would coexist with preference programs such as small business set-asides. Officials stated they do not want this program to negatively affect small businesses and that careful consideration was given when deciding where this program would fit within that framework. The DFARS rule issued in October 2024, among other changes, placed many of the pilot program’s implementing regulations in a new DFARS part that is separate from those that address small business contracting programs. An understanding of how a program fits into and would influence or be influenced by an organization’s existing programs and objectives is part of considering a pilot’s scalability. However, such an evaluation needs to be documented based on the information gathered during the pilot program.

On the other hand, DOD has told us that it has no knowledge about the number of companies that may be able to participate in the pilot. DOD further stated in its May 2024 Federal Register notice that it cannot estimate the number of contracting officers who will submit applications for participation in the pilot program. DPCAP officials, however, stated that DOD may award 16 contracts in the next phase but were not confident of this number. The second phase of the pilot program is underway, with applications being accepted on a rolling basis through the end of the pilot program in December 2029. However, without determining the target population—i.e., contractors that may be eligible for the program—on an ongoing basis or providing evidence that program objectives are being met, DPCAP will not be able to make an informed decision on scalability when the pilot ends.

Two-way stakeholder communication: partially aligned. We found that DPCAP had some communication with contracting officers and industry prior to and during implementation of the pilot program. For example, DPCAP’s November 2022 memorandum communicated the parameters of the program and how contracting officers and contractors could participate. However, this communication may have had a limited reach. We found that five of the eight contracting officers who participated in the pilot program were unaware of the program until a contractor or the office requiring the goods and services brought it to their attention. DPCAP officials stated they did not ask for input from DOD contracting commands or industry prior to implementing the pilot program, since DPCAP officials told us that they had enough contracting knowledge to adequately implement the pilot program.

DPCAP received some feedback from contracting officers and contractors after they had participated in the pilot program, but the information it collected was incomplete. For example, we found that some of the feedback did not include contractors’ perspectives as was requested by the DPCAP memorandum implementing the program.[19] Additionally, one contracting officer did not submit any feedback. As of October 2024, DPCAP officials stated they were still reviewing the feedback collected, but that most contracting officers reported no challenges with implementing the program. DPCAP also received some industry feedback on the program as part of the rulemaking process in 2024. According to DPCAP officials, the comments received during the rulemaking process did not result in any changes to the pilot program and most of the comments praised the program.

The December 2024 memorandum has the same requirement to collect contractors’ perspectives, and DPCAP officials stated they plan to solicit additional feedback about the program.[20] However, they had not yet determined how they would solicit that feedback, or from whom. DPCAP officials stated that their plan on how to collect this feedback would be included in a report to Congress, which they hope to complete by March 2025. Without ongoing two-way communication, with both its contractors and contracting staff, DOD cannot ensure that the program is appropriately designed and operating as intended. Additionally, DOD risks not having the necessary data for program managers and policymakers to make well-informed decisions about the pilot program.

Conclusions

DOD’s ESOP pilot program is well underway, as evidenced by DOD awarding eight contracts with a collective value of more than $450 million. DOD has taken some steps, through its updated pilot program guidance, to help contracting officers better implement the program. However, the updated guidance does not provide key information about eligibility requirements. Additionally, DOD’s approach to managing and evaluating the program did not fully meet leading practices for pilot program design, such as establishing measurable objectives and an evaluation plan that can help determine program effectiveness and scalability. Aligning its efforts with these leading practices can help DOD measure the success of the pilot program. Better alignment can also inform congressional decision-making about whether the program should be further expanded or modified, made permanent, or ended upon its completion. Since the pilot program is expected to continue until 2029, DOD still has time to improve how it is implementing and evaluating the pilot program.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following six recommendations to DOD:

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment provides additional guidance to contracting officials on key program requirements to further reduce the risk of awarding a contract to ineligible contractors. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment establishes well-defined, appropriate, clear, and measurable objectives for the ESOP pilot program. (Recommendation 2)

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment, after establishing clear and measurable objectives, clearly articulates a data collection and assessment methodology for its ESOP pilot program. (Recommendation 3)

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment, after establishing clear and measurable objectives, develops a plan to evaluate ESOP pilot program results. (Recommendation 4)

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment includes an assessment of scalability in the ESOP pilot program to inform decisions about whether and how to implement the program more broadly. (Recommendation 5)

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment incorporates appropriate, two-way communications with internal and external ESOP pilot program stakeholders, such as contracting officers and industry, about the design and operation of the pilot. (Recommendation 6)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to DOD for review and comment. DOD provided written comments, which are reprinted in appendix I. In its comments, DOD agreed with all six of our recommendations and highlighted a number of actions it is taking or plans to take to implement them.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees and the Secretary of Defense, the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment, and the Principal Director, Defense Pricing, Contracting and Acquisition Policy. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at (202) 512-4841 or sehgalm@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix II.

Mona Sehgal

Director, Contracting and National Security Acquisitions

List of Committees

The Honorable Roger Wicker

Chairman

The Honorable Jack Reed

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

United States Senate

The Honorable Mike Rogers

Chairman

The Honorable Adam Smith

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

House of Representatives

GAO Contact:

Mona Sehgal, (202) 512-4841, or sehgalm@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments:

In addition to the contact named above, Guisseli Reyes-Turnell (Assistant Director), Victoria Klepacz (Analyst-in-Charge), Cassidy Cramton, Lorraine Ettaro, Edward Harmon, Scott Hepler, Julie Kirby, Alec McQuilkin, Alyssa Weir, and Adam Wolfe made key contributions to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on Facebook, Flickr, X, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our RSS Feeds or Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7700

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, ClowersA@gao.gov, (202) 512-4400, U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7125, Washington, DC 20548

Public Affairs

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, KaczmarekS@gao.gov, (202) 512-4800, U.S.

Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7149

Washington, DC 20548

Strategic Planning and External Liaison

Stephen J. Sanford, Managing

Director, spel@gao.gov, (202) 512-4707

U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7814, Washington,

DC 20548

[1]The Explanatory Statement to the NDAA for Fiscal Year 2022 stated the innovative potential of encouraging nontraditional companies, like businesses wholly owned by an ESOP, to work with DOD.

[2]National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2022, Pub. L. No. 117-81, § 874 (2021). Companies can elect with the Internal Revenue Service to be an S corporation for the purposes of federal taxation. Unlike C corporations that are subject to corporate income tax, S corporations pass corporate income, losses, deductions, and credits through to their shareholders for federal tax purposes. Shareholders then report the pass-through income and losses on their personal tax returns and are assessed tax at their individual income tax rates. As ESOP trusts are exempt from federal income taxes, income passed through an S corporation to an ESOP trust is generally not taxed.

[3]Among other things, the amendment allows eligible contractors to be awarded noncompetitive follow-on contracts on all their existing contracts, instead of one follow-on contract per eligible contractor. The amendment also allows contractors to expend more than 50 percent of the contract cost on subcontracting if a subcontractor is also wholly-owned by an ESOP or if material needed for contracted products is not available from another business wholly-owned by an ESOP. National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024, Pub. L. No. 118-31, § 872 (2023). However, no contractors were selected using these new criteria at the time we initiated our review.

[4]GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO‑14‑704G (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 10, 2014).

[5]GAO, Data Act: Section 5 Pilot Design Issues Need to Be Addressed to Meet Goal of Reducing Recipient Reporting Burden, GAO‑16‑438 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 19, 2016). For our analysis, “fully aligns” means we found evidence that fully or significantly satisfied the leading practice; “partially aligns” means we found evidence that satisfied some but not a significant portion of the leading practice; and “does not align” means we found little or no evidence that satisfied the leading practice.

[6]The Internal Revenue Service defines an ESOP as an Internal Revenue Code § 401(a) qualified contribution plan that is a stock bonus plan or a stock bonus/money purchase plan. An ESOP must be designed to invest primarily in qualifying employer securities as defined by Internal Revenue Code § 4975(e)(8). See www.IRS.gov for more information on ESOPs.

[7]The National Center for Employee Ownership is a nonprofit organization that supports the employee ownership community by providing resources, including research on employee ownership.

[8]The proposed DFARS rule is published in the Federal Register. Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement: Pilot Program to Incentivize Contracting with Employee-Owned Businesses (DFARS Case 2024-D004), 89 Fed. Reg. 46,831 (proposed May 30, 2024). For more information on the rulemaking process, see GAO, Defense Acquisitions: DOD Needs to Improve How It Communicates the Status of Regulation Changes, GAO‑19‑489 (Washington D.C.: July 11, 2019).

[9]Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement: Pilot Program to Incentivize Contracting with Employee-Owned Businesses (DFARS Case 2024-D004), 89 Fed. Reg. 82,183 (Oct. 10, 2024).

[11]This information is located in the System for Award Management, which is the primary government repository for prospective federal awardees and federal awardee information. See SAM.gov for more information.

[12]A woman-owned small business is not “less than 51 percent unconditionally and directly owned and controlled by one or more women who are United States citizens.” 13 C.F.R. § 127.200(b)(2). In addition, 13 C.F.R. § 127.201(c) specifies that ownership must be direct and not through a trust, including not through an ESOP.

[13]DOD officials stated they will not exercise any remaining options on the contract.

[14]Internal Revenue Code § 6103 provides that federal tax information is confidential and to be used to administer federal tax laws except as otherwise specifically authorized by law.

[15]One deterrent against false self-certifications is the False Claims Act. 31 U.S.C. §§ 3729–3733. The False Claims Act provides treble damages and per claim penalties for false claims submitted to the government, including claims submitted by federal contractors. Federal contractors liable for a False Claims Act violation may be debarred, meaning they would be excluded from receiving federal contracts for a period of years.

[17]The Explanatory Statement to the NDAA for Fiscal Year 2022 stated the innovative potential of encouraging nontraditional companies, like businesses wholly owned by an ESOP, to work with DOD.

[18]This feedback was to be submitted upon completion of 6 months of contractor performance or no later than 30 days after the contract end date, whichever was sooner.

[19]Contracting officers were required to have companies participating in the pilot agree to provide feedback within 30 days of contracting officer request. Contracting officers were required to submit this request upon completion of 6 months of contractor performance or no later than 30 days after the contract end date, whichever was sooner.

[20]In addition, the new DFARS clause 252.270-7002 Pilot Program to Incentivize Contracting with Employee-Owned Businesses, when applicable, requires contractors participating in the pilot to report to the contracting officer no later than 30 days after the end of the contract period of performance certain information, such as the number of years the contractor has been wholly-owned by its ESOP and certain challenges it may or may not have experienced.