UKRAINE ASSISTANCE

U.S. Coordinated on a Broad Range of Aid to Displaced Persons and Refugees Amidst Various Challenges

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO-25-107535. For more information, please contact Latesha Love-Grayer at lovegrayerl@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107535, a report to Congressional Committees

U.S. Coordinated on a Broad Range of Aid to Displaced Persons and Refugees Amidst Various Challenges

Why GAO Did This Study

Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 created a forced migration crisis, with millions of Ukrainians forced to flee and millions more internally displaced within Ukraine. As of September 2024, USAID’s Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance and State’s Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration had provided over $3.75 billion in humanitarian assistance for the Ukraine response. Much of this assistance has benefited IDPs and refugees.

GAO initiated this review in response to a provision in Division M of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023. GAO’s review examines (1) the extent to which the U.S. and its international partners have strategies for addressing the needs of Ukrainian IDPs and refugees; (2) the types of assistance State and USAID have provided and any associated challenges; and (3) the extent to which State and USAID coordinated the implementation of this assistance with each other and international partners. GAO examined assistance provided between February 2022 and December 2024.

GAO analyzed agency documentation; met with USAID and State officials; conducted a site visit to Ukraine, Poland, and Moldova to observe assistance provided and met with officials and beneficiaries from these countries; and reviewed international strategies for humanitarian assistance and supporting documents.

What GAO Found

The U.S. contributed to key international strategies to address the needs of Ukrainian internally displaced persons (IDPs) and refugees between February 2022 and December 2024. The UN-led Ukraine Humanitarian Needs and Response Plan and Ukraine Regional Refugee Response Plan are the primary international strategies that underpin the humanitarian responses inside Ukraine and in refugee hosting countries, according to State and USAID. The U.S. played a consultative role in developing these strategies, including providing feedback on drafts. GAO found that these strategies contain many characteristics of an effective national strategy identified in GAO’s prior work, including a clear purpose, goals, and clear responsibilities. However, donor-provided funding fell short of estimated needs despite significant U.S. contributions. For example, in 2024, the refugee response plan received 21 percent of the estimated funding needed to implement it, with the U.S. providing over half of the funding received.

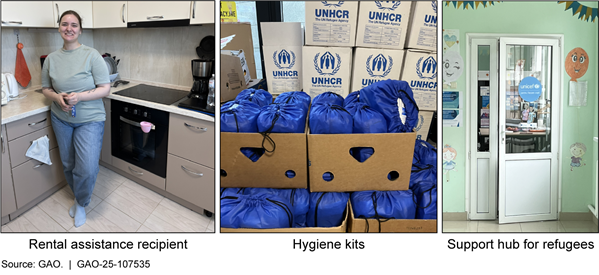

USAID and State provided a broad range of humanitarian assistance to IDPs and refugees between February 2022 and December 2024 amidst the ongoing conflict with Russia. USAID and State assistance to IDPs in Ukraine and refugees in surrounding countries included mental health services, shelter, water, sanitation, hygiene kits, and legal services. U.S. and partner officials reported challenges in delivering this assistance, such as security concerns near the front lines in Ukraine and shortages of skilled workers.

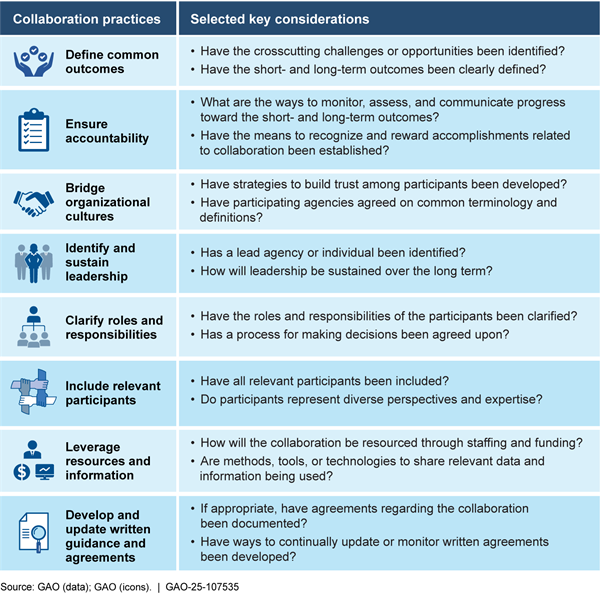

As of December 2024, USAID and State closely coordinated their humanitarian assistance for Ukrainian IDPs and refugees and had also taken steps to coordinate with international partners. Coordination between USAID and State was guided by a memorandum of understanding between the two agencies. GAO found that the coordination of this humanitarian assistance generally met all eight of GAO-identified leading practices for interagency collaboration, including defining common outcomes and clarifying roles and responsibilities. USAID and State also coordinated their assistance with international partners, primarily through regular meetings of United Nations forums.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

BHA |

Bureau of Humanitarian Assistance |

|

HNRP |

Humanitarian Needs and Response Plan |

|

IDP |

Internally Displaced Person |

|

MOU |

Memorandum of Understanding |

|

NGO |

Non-governmental Organization |

|

OCHA |

Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs |

|

OTI |

Office of Transition Initiatives |

|

PRM |

Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration |

|

RRP |

Regional Refugee Response Plan |

|

UN |

United Nations |

|

UNHCR |

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees |

|

USAID |

U.S. Agency for International Development |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

July 29, 2025

Congressional Committees

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 has had devastating consequences, threatening a democratic country’s sovereignty and creating a humanitarian crisis in Europe. The invasion also created a forced migration crisis, with millions of Ukrainians forced to flee to other countries as refugees and millions more were internally displaced within Ukraine. As of December 2024, Ukraine had approximately 3.7 million internally displaced persons (IDPs) and an additional 6.9 million Ukrainians were refugees outside of Ukraine, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

The U.S. government appropriated more than $174 billion in assistance, including assistance for IDPs and refugees, through five Ukraine supplemental appropriations acts as of April 2024.[1] USAID’s Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance (BHA) has primary responsibility for assisting IDPs, and the Department of State’s Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration (PRM) has primary responsibility for assisting refugees. As of September 2024, BHA and PRM had obligated over $3.75 billion in humanitarian assistance for the Ukraine response, with much of this assistance benefitting IDPs and refugees.[2]

The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023 includes a provision for GAO to conduct oversight, including audits and investigations, of amounts appropriated in response to the war-related situation in Ukraine.[3] This report examines (1) the extent to which the U.S. and its international partners have international strategies for addressing the needs of Ukrainian IDPs and refugees; (2) the types of assistance State and USAID have provided to Ukrainian IDPs and refugees through implementing partners, and challenges they have faced in providing this assistance; and (3) the extent to which State and USAID have coordinated the implementation of this assistance with each other and international partners. Our review focuses on assistance provided to Ukrainian IDPs and refugees from February 2022 through December 2024.

We traveled in September 2024 to Ukraine to examine IDP assistance and to Poland and Moldova to examine refugee assistance.[4] We based our selection of Poland and Moldova on the following criteria: 1) number of Ukrainian refugees in each country as of December 2023; 2) amount of funding provided by State/PRM to other countries from fiscal year 2022 through August 2024; and 3) the presence of a PRM Refugee Coordinator.[5]

To examine the extent to which the U.S. and its international partners have international strategies for addressing the needs of Ukrainian IDPs and refugees, we interviewed USAID, State, UN, and other international donor officials, and reviewed the UN’s Ukraine Humanitarian Needs and Response Plan (HNRP) and Ukraine Situation Regional Refugee Response Plan (RRP). [6] We also examined the most recent versions of these UN-led strategies-–the 2025 Ukraine HNRP and 2025-2026 Ukraine Situation RRP–-to determine the extent to which they incorporated desirable characteristics of national strategies previously identified by GAO.[7]

To report on the types of assistance USAID and State provided to Ukrainian IDPs and refugees and the challenges they faced in providing this assistance, we reviewed documents and interviewed USAID and State officials in Washington, DC. We also conducted site visits to observe the assistance provided and met with U.S., other donor, and host government officials as well as with U.S. implementing partners and beneficiaries in Ukraine, Poland, and Moldova.

To examine the extent to which USAID and State coordinated the implementation of assistance to Ukrainian IDPs and refugees with each other and international partners, we examined the Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) and annexes between USAID/BHA and State/PRM. We analyzed the MOU and its annexes, as well as its implementation in Ukraine against eight leading practices we have identified in prior work to help agencies collaborate more effectively.[8] We also reviewed documentation and interviewed relevant officials from USAID, State, implementing partners, host governments, and the UN. See Appendix I for additional details on our scope and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from May 2024 to July 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

USAID and State Bureaus Providing Assistance to Ukrainian IDPs and Refugees

BHA and PRM were the two main bureaus responsible for providing U.S. humanitarian assistance to internally displaced persons in Ukraine and Ukrainian refugees.

BHA

USAID’s BHA provided life-saving humanitarian assistance, including food, health, nutrition, protection, shelter, and water, sanitation, and hygiene services, to the most vulnerable and hardest-to-reach people. BHA had the lead responsibility for providing assistance to IDPs in Ukraine and emergency food assistance to Ukrainian refugees outside the country. Immediately after the full-scale invasion in February 2022, BHA deployed a Disaster Assistance Response Team to lead the U.S. humanitarian response.[9] The team was supported by a Response Management Team based out of Washington, D.C. In March 2025, State and USAID notified Congress of their intent to undertake a reorganization of foreign assistance programming that would involve realigning certain USAID functions to State by July 1, 2025, and discontinuing the remaining USAID functions. According to BHA officials, some of the humanitarian assistance being funded by BHA in Ukraine will continue under State, while the assistance not transferred to State will be terminated. As of May 2025, BHA’s Disaster Assistance Response Team in Kyiv reported that it was in the process of ending its operations because of these changes.

PRM

State’s PRM has the lead responsibility within the U.S. government for providing U.S. humanitarian assistance, protection, and durable solutions for refugees, asylum seekers, migrants in situations of vulnerability, and stateless persons. PRM has provided assistance to Ukrainian refugees in over 10 countries, including Poland and Moldova, and to IDPs in Ukraine. PRM has Refugee Coordinators in Warsaw, Poland; Kyiv, Ukraine; and Chisinau, Moldova. These coordinators serve as PRM’s primary representatives and liaisons to implementing partners, host governments, donors, and embassies as well as other U.S. government agencies in the countries under their purview. The coordinators have primary responsibility for direct monitoring and oversight of PRM’s assistance, including through meetings with partners, site visits of partner activities, and engagement with IDPs and refugees themselves as well as other partners within the international humanitarian response, according to PRM officials.

Ukrainian IDP and Refugees in Ukraine, Poland, and Moldova

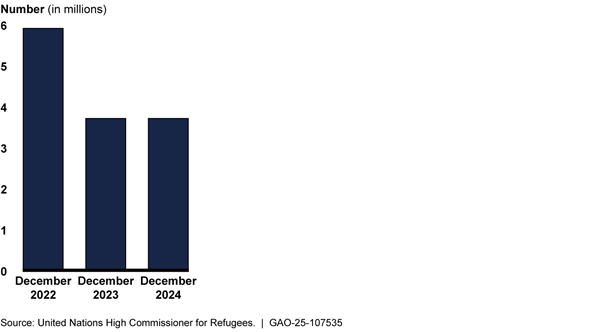

As of December 2024, an estimated 3.7 million people in Ukraine remained internally displaced as a result of the ongoing conflict, according to UNHCR. This is down from the estimated 5.9 million internally displaced reported in December 2022, but consistent with the 3.7 million reported in December 2023 (see fig. 1.)

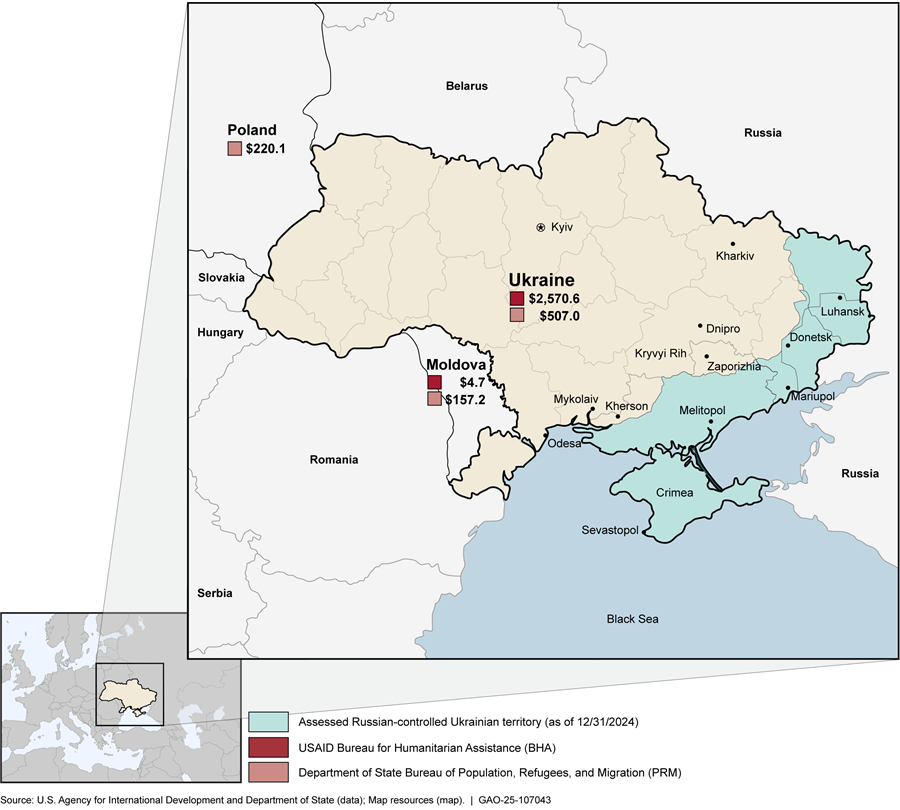

The UN-led 2025 Ukraine Humanitarian Needs and Response Plan reported that 82 percent of IDPs have been displaced for more than a year, with no viable prospects for return to their homes in the foreseeable future. Following expanded government-led evacuation mandates, more people have been evacuated and displaced from and within Ukraine’s east and north. The plan also estimates that there are 12.6 million people who were not displaced but directly affected by the war.[10] These conflict-affected groups, concentrated in front-line regions and areas along the Russian border, have greater needs due to destruction of critical civilian infrastructure and limited access to services, according to the UN. As of December 2024, BHA reported having obligated $2.6 billion and PRM reported having obligated $507.0 million in assistance within Ukraine.[11] (See fig. 2.)

Figure 2: Reported Obligations of U.S. Humanitarian Funding to Ukraine, Poland, and Moldova (in millions) as of December 2024

Note: U.S. humanitarian assistance in Ukraine is targeted at vulnerable populations, which include IDPs, but also includes other non-displaced populations affected by the war, according to U.S. officials.

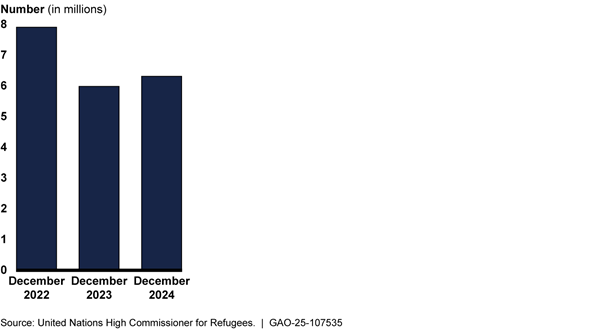

Approximately 6.9 million Ukrainians have fled the country as refugees as of December 2024, with the overwhelming majority—92 percent, or 6.3 million—have sought safety in Europe, according to the UN’s Regional Refugee Coordinator for the Ukraine Situation. This is down from the 7.9 million refugees recorded throughout Europe as of December 2022, but up from the 5.9 million refugees reported in December 2023 (fig. 3).

In Poland, approximately 1.9 million refugees have applied for temporary protection since the 2022 escalation of the war in Ukraine, according to the UN-led 2025-2026 Ukraine Situation Regional Refugee Response Plan.[12] The plan also states that currently approximately 980,000 Ukrainians are actively registered for temporary protection, or roughly half of the overall total. Poland’s refugee numbers are affected by some new arrivals, individuals crossing back and forth between Ukraine and surrounding countries, and some voluntary returns, according to the UN. As of December 2024, PRM reported having obligated $220.1 million in assistance for assisting refugees in Poland.[13]

Moldova has approximately 123,000 Ukrainian refugees representing nearly 4 percent of its population, the highest percentage of refugees relative to population size among countries hosting Ukrainian refugees, according to the UN-led 2025-2026 Ukraine Situation Regional Refugee Response Plan. As of December 2024, PRM reported having obligated $157.2 million in assistance for assisting refugees in Moldova. BHA reported having obligated $4.7 million in food assistance to Moldova.

International Humanitarian Coordination in Ukraine, Poland, and Moldova

Ukraine

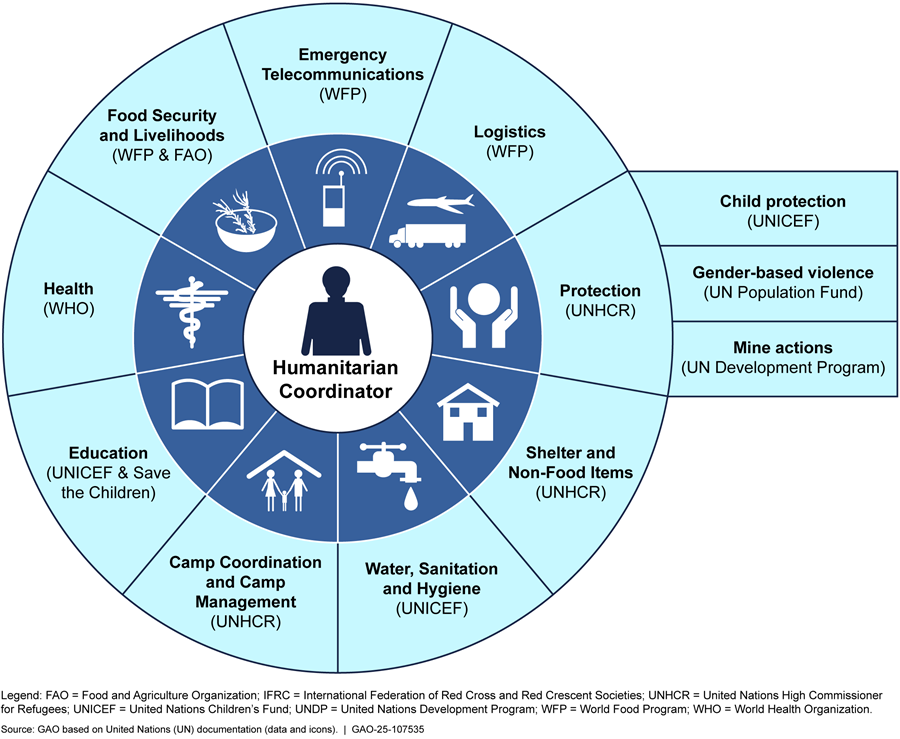

The UN supports humanitarian efforts in Ukraine through “clusters”, groups of humanitarian organizations within and outside the UN system. These clusters are organized into sectors of humanitarian action, such as water, health, and shelter, and have a lead agency to provide strategic direction and coordination. Since December 2014, when the armed conflict in the eastern oblasts of Donetska and Luhanska began, the UN has coordinated the efforts of these clusters through the Inter-Agency Standing Committee Humanitarian Cluster Coordination System (hereafter the UN cluster system). This system was expanded to cover the whole of Ukraine in response to Russia’s full-scale invasion in February 2022.

The Humanitarian Coordinator, with support from the UN’s Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) in a country, leads both the Humanitarian Country Team and oversees the cluster system.[14] The Humanitarian Country Team is a forum for decision-making and oversight related to humanitarian action for a specific country or response. The team is composed of leaders of UN agencies, representatives from non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement.[15] Heads of agencies who also lead clusters represent both their agency and their respective clusters in this forum.

There are nine active clusters and three sub-clusters contributing to the Ukraine response (fig. 4).

The UN cluster system in Ukraine also has a cash working group co-led by OCHA, the International Organization for Migration, and Ukrainian Red Cross Society.[16]

Poland and Moldova

In refugee contexts, including Poland and Moldova, coordination is guided by the UN’s Refugee Coordination Model. According to UNHCR, this model is designed to ensure effective, inclusive, and accountable responses to refugee crises. It also emphasizes government leadership, including local authorities, civil society, and refugee-led organizations, and works to avoid duplication and promote sustainability. The model is meant to help ensure that all actors—humanitarian organizations, governments, development partners, and local communities—work together effectively. According to UNHCR, this coordinated approach enables faster, more efficient delivery of aid and protection to refugees while supporting host communities.

The refugee coordination model is customized by UNHCR in each country to align with specific needs, capacities, and dynamics of the local context. For example:

· Poland’s coordination framework includes five main sectors: economic inclusion; shelter, housing and accommodation; health and nutrition; protection; and education.

· Moldova’s refugee coordination framework includes six main sectors: livelihoods and economic inclusion; protection; education; inclusion and solutions; health and nutrition; and information management.

U.S. and Its International Partners Developed Strategies to Address the Needs of Ukrainian IDPs and Refugees

The U.S. Consulted in Developing International Strategies to Address the Needs of both Ukrainian IDPs and Refugees

The U.S. consulted on the development of the UN-led Ukraine Humanitarian Needs and Response Plans (HNRP) and the Ukraine Situation Regional Refugee Response Plans (RRP) as of December 2024. These are the main international strategies that underpin the humanitarian responses for Ukraine, including assistance to IDPs and in refugee-hosting countries, respectively, according to both BHA and PRM officials. BHA took the lead in providing U.S. input into the development of the Ukraine HNRP and PRM took the lead for the RRP during the scope of our review, from February 2022 through December 2024.[17]

The Ukraine HNRP is developed each year through a collaborative process, primarily through the UN cluster coordination system. It involves the UN’s OCHA, local Ukrainian NGOs, international NGOs, and other humanitarian actors. BHA did not have a direct role in authoring the HNRP but provided feedback on drafts. According to BHA officials, the Disaster Assistance Response Team based in Kyiv and the Ukraine Response Management Team in USAID headquarters both reviewed the draft HNRP. They reported that they typically provided high-level feedback, such as suggestions for strengthening social cohesion and increasing localization efforts.

BHA also provided input into the HNRP through other avenues, including providing input through the Disaster Assistance Response Team’s donor observer seat on the Ukraine Humanitarian Country Team, according to officials.[18] BHA’s implementing partners also helped develop the HNRP through their engagement in the humanitarian sector-specific clusters (e.g., shelter, food, health) by providing inputs on needs and planned program activities and funding.

The Ukraine RRP is coordinated by UNHCR in collaboration with other UN agencies and partner organizations. The 2025-2026 plan prioritizes ensuring that refugees have effective access to legal status and rights, fostering socio-economic inclusion, addressing the specific vulnerabilities of certain groups, promoting social cohesion between refugees and host communities and ensuring government ownership and localization of the response. Although the U.S. does not have a formal approving role in the Ukraine RRP, PRM took the lead in providing U.S. input on its development, according to PRM officials.[19] PRM refugee coordinators based in Ukraine, Poland, and Moldova met regularly with partners, particularly UNHCR, the lead drafter of the RRP. The refugee coordinators outlined U.S. assistance priorities and provided donor feedback during the RRP development process. PRM also participated in donor coordination groups that worked together to provide feedback shared through implementing partners as part of developing the RRP, according to PRM officials.

Lastly, PRM also reported using collective engagement mechanisms such as the Senior Officials Meetings to ensure that both the RRP and, with support from BHA, the HNRP continued to reflect the priorities as outlined by the United States.[20]

Current International Strategies Have Elements of Effective National Strategies but Limited Funds Despite U.S. Contributions

The UN-led 2025 Ukraine HNRP and 2025-2026 Ukraine RRP both generally addressed all six desirable characteristics of an effective national strategy as identified by GAO in previous work.[21] The six desirable characteristics are: (1) purpose, scope, and methodology; (2) problem definition and risk assessment; (3) goals, subordinate objectives, activities, and performance measures; (4) resources, investments, and risk management; (5) organizational roles, responsibilities, and coordination; and (6) integration and implementation.[22]

For example, we found that the 2025 HNRP generally addressed the characteristic of having goals, subordinate objectives, activities, and performance measures by incorporating overall strategic objectives and sector-specific sub-objectives, as well as a monitoring framework to track progress towards achieving those objectives, including performance indicators. We also found that the RRP provided discussions on the regional risks and needs that the plan intends to address, as well as country-specific overviews of the situation, risks, and needs, thereby generally addressing the problem definition and needs assessment characteristic. See Table 1 for more examples of how each strategy generally addressed selected elements of the six desirable characteristics.

Table 1: Selected Elements of GAO’s Desirable Characteristics in International Strategies to Address the Needs of Ukrainian IDPs and Refugees

|

Desirable Characteristic |

Brief Description |

Examples Of Elements from UN-led 2025 Ukraine Humanitarian Needs and Response Plan (HNRP) and 2025-2026 Ukraine Situation Regional Refugee Response Plan (RRP) |

|

Purpose, Scope and Methodology |

Addresses why the strategy was produced, the scope of its coverage, and the process by which it was developed. |

HNRP: The HNRP’s purpose is to outline the strategy to ensure an adequate, timely, life-saving and life-sustaining humanitarian response in Ukraine. RRP: The RRP serves as an inter-agency strategic planning, coordination, programming, advocacy and fundraising tool. It supports host governments in providing protection and assistance to refugees, the communities hosting them, and other relevant population groups in large and complex emergencies. |

|

Problem Definition and Risk Assessment |

Addresses national problems and threats the strategy is directed towards. |

HNRP: The HNRP contains an overview of the crisis, as well as an analysis of shocks, risks, and humanitarian needs in Ukraine. For example, it states that an estimated 12.7 million people in Ukraine need humanitarian assistance. RRP: The RRP contains an overview of regional risks and needs. Each country chapter also includes a discussion of the current situation, as well as country-specific risks and needs. For example, the RRP states that refugees’ vulnerabilities are compounded by their protracted displacement, and the diminishing resources in host countries heighten the urgency of reinforcing protection systems, healthcare access, education inclusion, and economic support. |

|

Goals, subordinate objectives, activities, and performance measures |

Addresses what the strategy is trying to achieve, steps to achieve those results, as well as the priorities, milestones, and performance measures to gauge results. |

HNRP: The HNRP has strategic objectives with targets to measure progress and performance. For example, one objective is to “provide principled and timely multisectoral life-saving emergency assistance to the most vulnerable internally displaced people and non-displaced war-affected people, ensuring their safety and dignity, with a focus on areas with high severity levels of need” and has a target of assisting 5.6 million people under this objective. RRP: The RRP also has strategic objectives and targets to measure progress and performance. For example, one objective is to “support host countries to ensure that refugees have continued access to protection, legal status, and rights, with a particular focus on groups in vulnerable situations” and has a target of supporting approximately 2.5 million people, over a two-year span, in accessing protection services. |

|

Resources, investments, and risk management |

Addresses what the strategy will cost, the sources and types of resources and investments needed, and where resources and investments should be targeted. |

HNRP: The HNRP states that in 2025 the humanitarian community will need $1.75 billion to provide multisectoral humanitarian assistance to 4.8 million people in Ukrainea. It also discusses prioritization of assistance within the sectors. RRP: The RRP States that $1.24 billion is needed in 2025-2026 to meet the needs of 2.1 million refugees in over 10 countries. The country-specific strategies in the plan also discuss priorities. |

|

|

|

|

|

Desirable Characteristic |

Brief Description |

Examples Of Elements from UN-led 2025 Ukraine Humanitarian Needs and Response Plan (HNRP) and 2025-2026 Ukraine Situation Regional Refugee Response Plan (RRP) |

|

Organizational roles, responsibilities, and coordination |

Addresses who will be implementing the strategy, what their roles will be compared to others, and mechanisms for them to coordinate their efforts. |

HNRP: The HNRP includes a section on coordination that discusses coordination both within and amongst the humanitarian sectors. RRP: The RRP outlines a regional coordination structure and country-specific coordination frameworks. |

|

Integration and implementation |

Addresses how a national strategy relates to other strategies’ goals, objectives and activities; and how to subordinate levels of government and their plans to implement the strategy. |

HNRP: The HNRP states that the humanitarian country team will promote more inclusive engagement with government and development actors, including through the UN Sustainable Development Cooperation Framework. It also discusses integration of cash assistance with host government systems. RRP: Country-specific objectives include linkages to other plans. For example, the Moldova strategy provides linkages for each objective to UN Sustainable Development Goals. |

Source: GAO and GAO Analysis of the UN-led 2025 Ukraine Humanitarian Needs and Response Plan and the 2025 – 2026 Ukraine Situation Regional Refugee Response Plan and supporting documents. I GAO-25-107535

Notes: a While the original 2025 HNRP stated that the humanitarian community would require $2.63 billion to provide multisectoral humanitarian assistance to 6 million people in Ukraine in 2025, it was reduced in April 2025 to $1.75 billion to assist 4.8 million people. According to the revised 2025 HNRP, this is due in part to a sharp and sudden contraction in humanitarian funding.

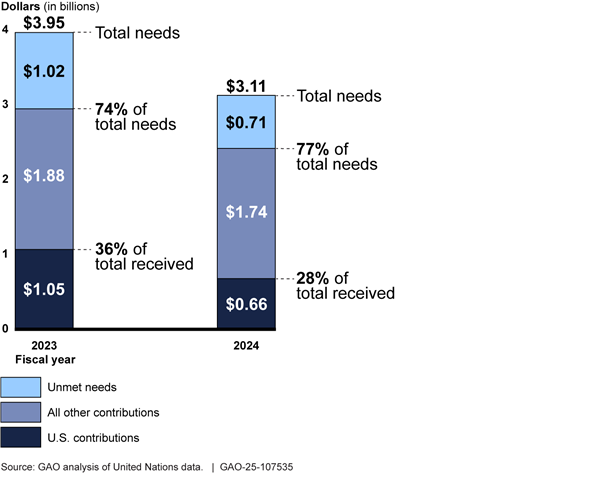

Implementation of both the Ukraine HNRP and Ukraine RRP has been affected by constraints in donor funding over the past few years. While the strategies aim to address the needs of the IDPs and refugees, previous versions of both the HNRP and RRP identified financial needs to implement the strategies that exceeded funding received from donors, despite significant U.S. contributions.[23]

For example, the 2023 Ukraine HNRP received $2.93 billion of the $3.95 billion that the plan identified as needed for full implementation. The 2024 Ukraine HNRP received $2.40 billion out of the $3.11 billion identified in the plan. The 2025 HNRP originally set financial needs at $2.63 billion, but in April 2025 the amount requested was lowered to $1.75 billion. According to the revised 2025 HNRP, the change is due in part to what the re-prioritized plan called a sharp and sudden contraction in humanitarian funding driven in part by the U.S. government’s suspension of humanitarian programming in January 2025.[24] The plan further states that the change is also due to the anticipated reduction of overall humanitarian funding for the year. The U.S. had been the largest single contributor to the Ukraine HNRP, providing 36 percent of the total funding received for 2023 and 28 percent for 2024 (fig. 5). The next closest contributor in both 2023 and 2024 was Germany, which contributed 13 percent in 2023 and 19 percent in 2024.

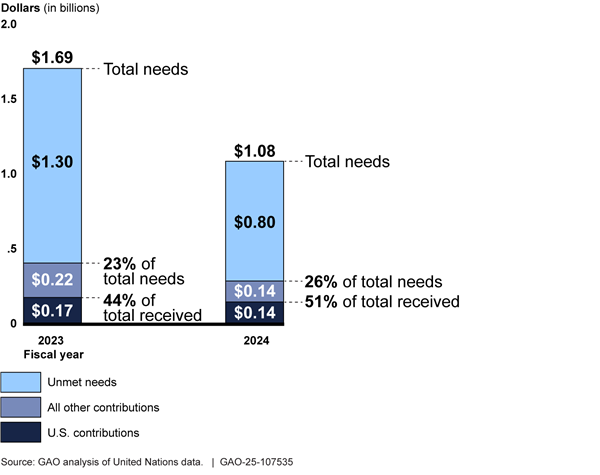

The 2023 Ukraine RRP received $393 million out of $3.89 billion that the plan identified as necessary for full implementation, while the 2024 Ukraine RRP received $226 million out of a needed $1.08 billion. The 2025-2026 RRP has set its 2025 financial needs at $690 million. The U.S. has been the largest single contributor to the Ukraine RRP, providing 43 percent of the total funding received for 2023 and 51 percent for 2024 (fig. 6). The second largest contributor in 2023 was Germany, contributing 12 percent of total funding received, and in 2024 it was the European Commission, contributing 11 percent of the total received.

U.S. and international donor officials stated that they expect humanitarian funding to continue decreasing as the war continues, despite a sustained high level of need. According to PRM officials, rising global humanitarian needs and declining global humanitarian funding will continue to limit partners’ abilities to achieve targets outlined in the RRP. PRM has advocated for additional support from other donors while encouraging partners to develop streamlined and sustainable programming that can meet needs in more cost-effective ways. BHA and PRM officials told us that in making award decisions, they considered factors such as which sectors in the HNRP or RRP, as appropriate, have the greatest needs and have received the least amount of funding from other donors. Both of these UN-led strategies also discuss the importance of transitioning to more longer-term sustainable assistance and, in the case of refugees, integration into host government national systems, as people remain displaced for extended periods of time.

USAID and State Offered Critical Humanitarian Assistance to Ukrainian IDPs and Refugees Despite Various Challenges

USAID and State Provided a Broad Range of Humanitarian Assistance to IDPs and Refugees

Between February 2022 and December 2024, BHA and PRM provided multi-sector humanitarian assistance through various implementing partners to those affected by the conflict in Ukraine, including IDPs and refugees, in alignment with the needs outlined in the HNRP and RRP (Table 2).[25]

Table 2: Selected Types of Humanitarian Assistance BHA and PRM-Funded Partners Provided to Ukrainian IDPs and Refugees Between February 2022 and December 2024

|

|

Multipurpose Cash Assistance |

Cash in the form of cash-based transfers and vouchers allowed displaced or other conflict-affected people to meet their immediate needs (such as clothing, food, fuel, shelter, or utilities) through local markets. |

|

|

Shelter Assistance |

Emergency shelter assistance to conflict-affected populations supported the rehabilitation of damaged shelters and bolstered vulnerable populations’ preparedness for winter across Ukraine. Assistance included emergency shelter kits, small and medium repairs to houses, and repairs to collective sites, which serve as hubs for temporary accommodations for displaced persons, according to a UN official. |

|

|

Protection Assistance |

Protection assistance, such as legal aid for lost document cases and forced displacement consultations, gender-based violence prevention and response services, case management and mental health psychosocial services helped conflict-affected populations cope with threats such as exclusion from life-saving humanitarian assistance, exploitative labor, family separation, and sexual violence. |

|

|

Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene Services (WASH) |

Water, sanitation, and hygiene services (WASH) supported conflict-affected populations, including distributing hygiene kits, repairing damaged WASH infrastructure, and transporting safe drinking water to conflict-affected areas in Ukraine and for refugees in surrounding countries such as Moldova and Poland. |

|

|

Health Assistance |

Health assistance, including health care supplies, medicine, and other health assistance in Ukraine and neighboring countries supported the health needs of conflict-affect populations. |

Source: GAO analysis of USAID and State Documents released as of January 2025. I GAO-25-107535

Multipurpose Cash Assistance

The multipurpose cash assistance program in Ukraine evolved during the conflict to become more targeted to the most vulnerable people, focusing on individuals residing along the front-line conflict areas in eastern and southern Ukraine, according to an implementing partner. Vulnerability criteria have been agreed upon and adopted by the cash working group, which is part of the UN’s humanitarian assistance coordination structure in Ukraine. Specific criteria include earning less than UAH 5,400 (around $142) per person and single headed households with at least one minor child or person over 55 years of age. Other criteria include head of households over 55 years of age and/or households with one or more persons with specific needs such as a disability or chronic illness.

In Ukraine, cash assistance generally totaled UAH 3,600 (around $95) per person per month for three months. According to a PRM-funded partner (PRM partner), IDPs faced a 2-to-3-month enrollment period to obtain government assistance. Therefore, cash assistance typically lasted 3 months to provide for people waiting on the government assistance program. According to post-distribution monitoring conducted by this partner, the most common expenditures reported were food (76 percent), health costs (67 percent), utilities and bills (50 percent), hygiene items (35 percent), and clothes and shoes (29 percent).

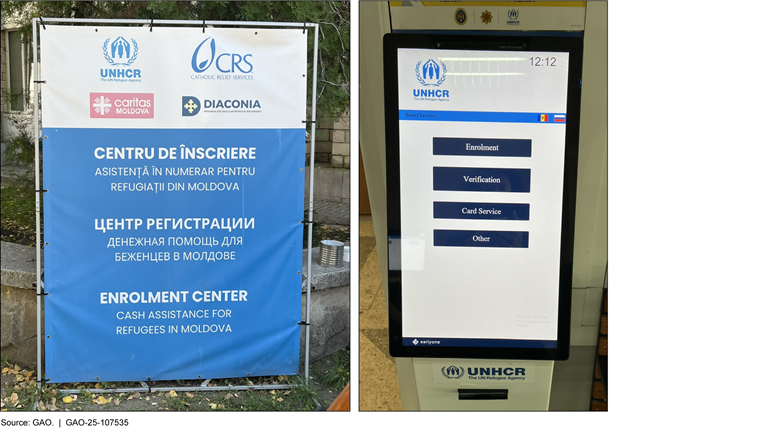

Outside Ukraine, PRM provided assistance to UN partners to provide multipurpose cash assistance to refugees in neighboring countries, often focusing on households with children or people with disabilities, among other criteria. One PRM partner began a multipurpose cash assistance program for refugees in Moldova in March 2022. The program announced in mid-2023 it would require beneficiaries to obtain legal status by February 2024 to continue receiving cash assistance. In December 2023, there were 41,000 beneficiaries. The program further introduced strict vulnerability criteria in July 2024, which decreased the total number of beneficiaries to 17,500, according to PRM officials. In September 2024, we visited a cash assistance enrollment center in Moldova and observed some of the security and identification systems in use to enroll refugees in a common registration system and financial platform (fig. 7). UNHCR officials said they used biometrics on all recipients over 6 years of age and use 35 different data fields to cross-check eligibility requirements as their standard operating procedure.

In Poland, PRM partners began offering cash assistance to Ukrainian refugees in March 2022, but cash assistance had been discontinued as of July 2024. Other types of assistance, such as access to the labor market, medical services, education, and social assistance, have continued for those who have established their temporary protection status in the country as of December 2024.

Shelter Assistance

The initial movement of IDPs was from east to west in Ukraine at the onset of the conflict in February 2022, according to a partner. This led to the creation of many collective sites, which are temporary accommodations for IDPs or those displaced from areas affected by hostilities, in the west. According to the Camp Coordination and Camp Management Cluster, the central coordinating body for shelter assistance, there were 1,958 collective sites across Ukraine as of December 2024. BHA and PRM partners provided repairs to collective sites between February 2022 and December 2024. Partner officials said that they are seeing more localized displacement, where people are staying closer to their homes, than during the early months of the conflict in 2022.

BHA and PRM partners also provided shelter materials, commodities, and cash assistance to help with IDPs’ shelter needs. For example, a BHA partner rehabilitated child-friendly shelters and provided winter-related relief commodities, including blankets and children’s winter clothing, to vulnerable populations. Another partner offered a rental assistance program to help IDPs find affordable and suitable accommodations (fig. 8).

Outside Ukraine, PRM partners and host government officials supported temporary housing called “refugee accommodation centers” in Moldova and “collective centers” in Poland. In the refugee accommodation centers, PRM partners provided assistance such as hot meals because residents generally had no access to cooking facilities. A PRM partner said that those Ukrainian refugees who had the means transited through Moldova to Romania and other countries. According to another partner, this left the more vulnerable behind, including women and children, people with disabilities, and elderly refugees. Similarly in Poland, a PRM partner said that approximately 80 percent of the refugees with temporary protection status were women and children.

PRM partners in Poland have provided assistance to collective shelters, including site management, small-scale renovations, and providing equipment for collective sites and integration centers, and household appliances for shelters. In September 2024, we visited the largest collective center in Warsaw, Poland, that was designed to ensure accessibility for individuals with disabilities. We observed the range of modifications made to the building to meet the needs of this population, such as tactile ground surface indicators to help visually impaired individuals understand their exact location in the building. In addition, the facility had platform and stair-climbing devices at the entrance to allow wheelchair access (fig. 9).

Figure 9: Collective Center in Poland with Tactile Ground Surface Indicators for Visually Impaired Individuals

Protection Assistance

BHA and PRM partners in Ukraine provided various types of protection assistance including child protection, gender-based violence and human trafficking prevention, and legal assistance such as legal aid for lost document cases and forced displacement consultations. According to the World Health Organization the war in Ukraine has placed additional pressure on an already strained mental health system, disrupting much-needed mental health and psychosocial support services for people in need. USAID reported that the most common mental conditions are depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder, and substance abuse.

Other protection assistance provided by BHA and PRM partners in Ukraine included case management for vulnerable children, legal assistance and protection monitoring.

· According to guidance issued by the case management working group, services are focused on supporting the most vulnerable children. These services are intended to protect children experiencing or at heightened risk of physical, emotional, or psychosocial harm, as well as children whose specific needs were exacerbated by the war and forced displacement.

· Partners also provide legal assistance. For example, partners we spoke to provided legal assistance such as free legal aid consultations related to forced displacements; helped improve access to legal rights for stateless persons; and helped resolve lost documentation issues.

· In addition, PRM partners offered protection monitoring, which aims to identify human rights violations and other protection risks encountered by IDPs and the conflict-affected population. According to a PRM partner, their protection monitoring findings allow them to shape their response in addressing issues or gaps.

As in Ukraine, PRM partners provided various types of protection assistance in Moldova and Poland. PRM partners in Moldova said there is a high level of need for mental health services. Some of the services that PRM supported are provided at centers and border crossing points, but a PRM partner was also developing mobile teams to provide services to less accessible areas. Likewise, in Poland, mental health and psychosocial support was consistently identified as a persistent, critical need. A PRM partner said that Ukrainian as well as Polish individuals have difficulty accessing mental health care in Poland. They went on to say that aid partners need to create a care system that does not parallel the Polish system but rather works to find gaps. The PRM partner said they are aided by a multi-sector needs assessment to help them provide an integrated road map to the overall health care system.

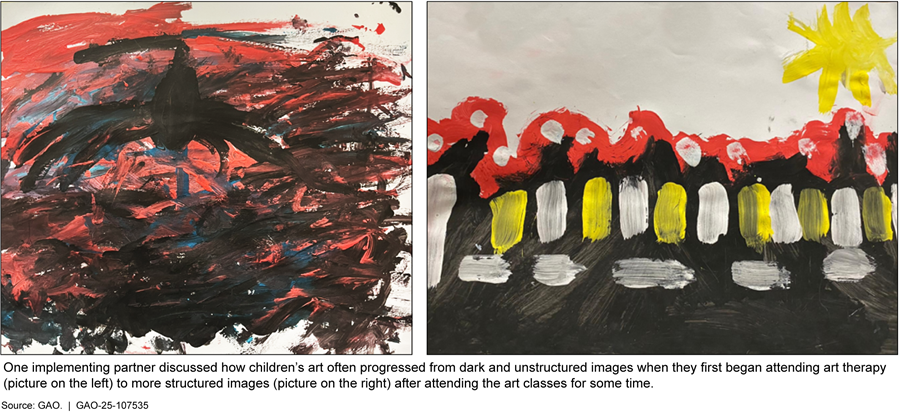

Examples of mental health and psychosocial assistance provided by BHA partners include community mental health teams providing consultations to individuals with severe mental health disorders, running support sessions with art projects, and group discussions to help individuals express themselves and connect with others. According to a BHA partner, painting and other similar activities are a form of group therapy. In September 2024, we visited a support center for education and development in Poland for children and observed an art therapy class and spoke to the children participating int it. The students described the benefits they were receiving from the therapy and teachers showed us the difference between the pictures drawn by a student when the student first arrived and after months of therapy (fig. 10).

PRM partners in both Poland and Moldova have also established Blue Dot centers, which are multi-agency facilities that provide one-stop protection services and social service referrals to newly arrived refugees (fig. 11). The Blue Dot centers were set up at border crossing points, train stations an accommodation center, and a community center. They have been phased out in Poland as of the end of December 2023, but several were still operating in Moldova as of December 2024.

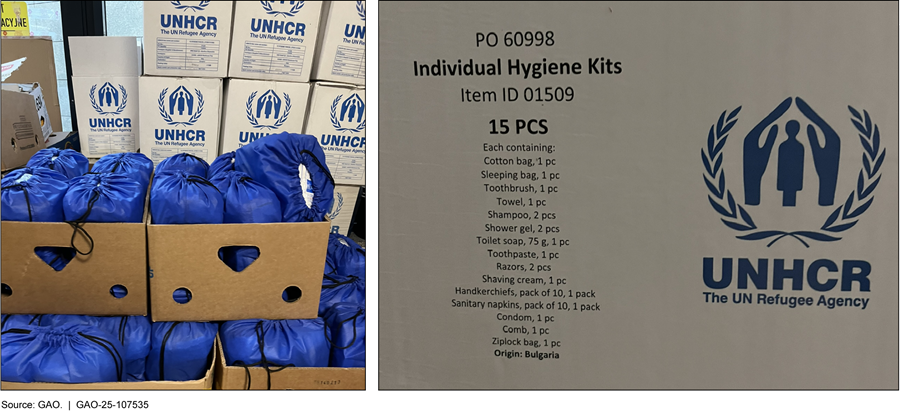

Water, Sanitation and Hygiene

BHA and PRM partners have provided water, sanitation, and hygiene assistance by distributing hygiene kits, repairing damaged infrastructure, and delivering clean water to affected areas. A partner we visited in September 2024 provided hygiene kits to beneficiaries that they said will last up to 3 months, and beneficiaries can get additional kits for a total of 9 months of support. We observed one of the storage rooms of these supplies, which was filled with hygiene kits that contained items such as a toothbrush, shampoo, and soap, during our visit in September 2024 (fig 12.).

Partners are providing water, sanitation infrastructure in shelters and hygiene kits to conflict-affected populations because they are often more susceptible to waterborne diseases. A PRM partner in Moldova said that assistance follows the refugees on the move. For example, water, sanitation and hygiene support, such as hygiene kits, are located at the border points and are given to the refugees on their way to the refugee accommodation centers. If they go to a refugee accommodation center, they receive additional appropriate services and supplies. In Poland, PRM partners said that they are working to ensure that refugees have access to quality water, sanitation, and hygiene services to prevent waterborne diseases and the associated morbidity and mortality. PRM partners also said that they are strengthening sanitation infrastructure in shelters.

Health Assistance

To help meet the health needs of IDPs and other conflict-affected populations, both BHA and PRM supported partners providing health assistance in Ukraine and neighboring countries. Assistance included supporting primary health care facilities and providing maternal, infant, and young child nutrition interventions to parents and caregivers in Ukraine.

In Moldova, according to a PRM partner, they provided immunization, emergency services and hospital care and worked with the Ministry of Health on integrating refugees into their health system. In Poland, a PRM partner utilized mobile psychosocial teams to provide direct assistance to residents in long-term accommodation centers.

Other Assistance

BHA and PRM also provided other types of assistance to IDPs and refugees, including food assistance, logistics support, education, and integration between February 2022 and December 2024. For example:

· In addition to meeting the food assistance needs of IDPs and refugees through cash assistance, BHA provided in-kind food baskets and food distribution in eastern and southern Ukraine where conflict and supply chain difficulties limit access. In Poland, PRM partners provided food assistance to vulnerable refugees at border areas, in urban areas, and while in transit.

· BHA has also supported the Logistics and Emergency Telecommunications clusters in Ukraine, comprising UN agencies, NGOs, and other stakeholders. These are two of the nine UN clusters working together for the coordination of Ukraine assistance. For example, with BHA assistance, the World Food Program coordinated logistics services for the broader humanitarian response, developed common advocacy to address logistical challenges, facilitated humanitarian convoys and corridors to hard-to-reach areas, and established logistics bases to consolidate and prioritize humanitarian cargo deliveries.

· PRM provided assistance in Poland and Moldova to assist Ukrainian refugees in receiving an education. In Poland, PRM partner assistance included early learning, skills development, catch up classes, language courses, and mental health support. It also included provision of learning materials and access to IT equipment, and capacity development for teachers, specialist teachers, and school principals focusing on inclusive education. In Moldova, a PRM partner implemented technology labs in schools where Ukrainian students could continue to learn online in Ukrainian schools, while being physically located in Moldovan schools. These labs are supervised, managed, and mentored by Ukrainian teachers to foster camaraderie between Ukrainian and Moldovan students and strengthen social cohesion among host and refugee communities.

· In Poland, PRM partners also support centers to integrate Ukrainian refugees in social, vocational and education activities. These centers, which can be run in cooperation with local authorities, provide refugees with assistance and services to help them integrate into their communities. For example, a center we visited in Rzeszow in September 2024 provided legal services, vocational training, and sponsored a local women’s council. Another center we visited in September 2024 provided adult and senior classes and workshops, language classes in Polish and English, legal services offered in Ukrainian and Polish, and art therapy classes.

Challenges Including Security, Access, and Resources Affect Humanitarian Assistance to IDPs and Refugees

BHA, PRM, and their partners faced numerous challenges in providing assistance to IDPs and refugees, including challenges related to safety and security, access, capacity, and resources.

Reported Challenges Related to IDP Assistance

Challenges reported in delivering assistance to IDPs included:

· Conflict-Related Safety, Security, and Access Issues. Agency officials said that while the front line of military activity is in eastern and southern Ukraine, Russian missile and drone attacks reach all areas of the country, targeting critical infrastructure and population centers (fig. 13). Russian attacks on Ukraine’s electrical grid have caused blackouts and led to a reduction in power generation, which affects partners’ ability to provide humanitarian assistance. Multiple partners and agency officials said that they experience difficulties getting access to some of the more vulnerable, such as the elderly and people with disabilities, who have been unable to leave their homes in the front-line conflict areas. Partners and an agency official told us that there were safety and security risks for their staff when providing humanitarian aid to Ukrainians. One partner said they balance the needs in a specific area with their capacity to respond safely and another partner said that they provide services in unsafe and dangerous regions. The agency official said that humanitarian workers are at risk of injury or death when delivering assistance to the frontlines. PRM officials stated that partners in frontline areas have experienced situations where they cannot deliver needed assistance. PRM officials also told us that security concerns due to the ongoing conflict present a challenge for monitoring the assistance, as they cannot visit sites in person.

· Decreasing Humanitarian Funding. BHA, PRM, and partner officials also reported that decreasing donor funding is a challenge and that humanitarian needs in Ukraine outpace the available funding. Similarly, OCHA officials told us that the decrease in humanitarian funding available for Ukraine was significant and half of the resources that were available last year were no longer available. The officials expected this downward trend to continue. Limited resources have forced donors to focus assistance on the most vulnerable and in conflict areas where there is the greatest need, according to partner officials. This has resulted in neglecting ongoing humanitarian needs in western Ukraine, according to one partner. Due to the decrease in funding for humanitarian assistance, agency officials told us that BHA and their partners had to implement stricter vulnerability criteria to ensure assistance reached those that needed it most.

· Long-term and Multiple Displacements. U.S. and partner officials also described challenges stemming from multiple, long-term displacements. An agency official said that many IDPs in Ukraine have been displaced for an extended period, living in collective centers or with host families. According to this official, if the IDPs are not able to find suitable employment or feel integrated into their host community, they may try to return to their original home near the front lines or hazardous areas because they feel that they do not have other options. As noted above, partners have difficulty accessing these areas to provide assistance. A partner said that IDPs living outside of collective centers especially in the west and central regions of Ukraine were very vulnerable and the needs of these IPDs were more transitional or developmental, but this type of assistance were not very present in Ukraine at this time. Another partner noted that some challenges affecting IDPs, such as damage to the electrical grid, cannot be addressed by short-term humanitarian assistance.

· Limited Local Capacity. The capacity of local NGOs is another significant challenge cited by partners and agency officials. BHA officials told us that it is challenging for local NGOs and organizations to meet the stringent eligibility and application criteria to qualify for BHA assistance awards and, as such, only four have received awards. Several partners also stated that many local NGOs and organizations lacked the capacity or skills to provide the needed assistance. In addition, according to one partner official, some of the local organizations lack qualified staff to provide certain services, creating a shortage in needed services such as social workers. According to partner officials, male Ukrainian contractors and staff who are eligible for mobilization and conscription may be recalled for the war effort, which limits organization capacity. Additionally, one partner reported that the influx of IDPs placed a strain on local health systems, resulting in longer wait times.

In addition to challenges in delivering assistance to IDPs, agency and partner officials reported some challenges that IDPs faced in obtaining assistance. These included:

· Transportation Access Issues. Difficulty accessing transportation services near front-line areas may prevent some individuals from accessing services, according to partner officials.

· Documentation Issues. According to partner officials, loss of IDs or lack of documentation, especially for Ukrainians who had resided in Russian-occupied territories of Ukraine, can create issues for IDPs accessing assistance.

· Conscription Fears. The fear of conscription may lead men not to seek registration or access to services in Ukraine because they do not want to provide details that could identify them as eligible for conscription, according to partner officials.

· Stigmas and Cultural Norms. One partner reported that stigma and discrimination, particularly toward women, people with disabilities, and those with mental health issues, create barriers to accessing assistance. Cultural norms may also deter help-seeking behavior, especially related to mental health and psychosocial assistance.

Reported Challenges Related to Refugee Assistance in Moldova and Poland

In Moldova and Poland, agencies and partners reported facing similar challenges related to providing assistance to refugees.

· Decreasing Humanitarian Funding. PRM officials said that declining humanitarian funding for Ukrainian refugees from international donors limits what partners can do to assist refugees.

· Limited Local Capacity. The lack of specialized care in Moldova created challenges for assisting some refugees. In Moldova, partner officials said that there was a high need for mental health support services for the elderly, children and youth. While they said that some of these services were provided at common centers and border crossing points, they were also developing mobile teams to provide services to less accessible areas. Officials cited the “brain drain” of health service providers and the lower wages paid in Moldova compared to other countries.

· Lack of Employment Opportunities. In Moldova, PRM partners said that challenges to the labor market included the language barrier, access to childcare, skills mismatches, low salaries, and barriers to self-employment. Similarly, in Poland, obstacles to finding employment for refugees included the language barrier, limited job opportunities, and skill mismatches. A significant percentage of working-age women are also unable to work because of family responsibilities, highlighting the need for better access for childcare and care services. In October 2024, a PRM partner cosponsored a job and entrepreneurship fair in Warsaw that attracted more than 3,500 participants.

· Education-related Integration Challenges. PRM partners in Moldova and Poland reported challenges related to providing education assistance. The governments of Moldova and Poland have approached the integration of refugee children into their education system differently, which has created challenges to education sector assistance in each country.

· According to the Moldova Ministry of Education and Research, fewer than 10 percent of refugee children were enrolled in Moldovan schools as of September 2024. The Ukraine government supported online schooling for Ukrainian children, but Moldovan and partner officials pointed out the negative impact of relying solely on online learning, which may isolate students because of no interaction with peers and may increase protection risks. As described earlier, a PRM partner has implemented technology labs in Moldova schools where students could continue to learn online in Ukrainian schools and still interact with their fellow students. According to partner officials, there is a concern that in the future there will be a notable segment of Ukrainian students who are uneducated and unable to integrate effectively into the host country or even back into Ukraine.

· In mid-2024, the Polish government made it mandatory for refugee children to attend Polish schools for refugee families to continue receiving additional assistance, according to PRM officials. Some Ukrainian refugees delay enrollment of their children into school because classes are in Polish, and they fear that their children will lose their Ukrainian identity. PRM partners are providing assistance to Ukrainian refugees to ease this transition, such as offering Polish language classes, and support outside of school to help students catch up.

Agency officials and partners reported some other challenges related to providing and obtaining humanitarian assistance to refugees:

· Discrimination: Roma refugees in both Moldova and Poland faced discrimination and other challenges, according to partner and Polish and Moldovan government officials.[26] According to a report from the European Parliament, civil society organizations and the media have reported that Ukrainian Roma have been facing increasing difficulties along the evacuation route, at border crossing points, and on arrival in Europe. The Roma have had to cope with racial discrimination and segregation in transportation, humanitarian assistance and accommodation, and also with food and water deprivation and poor living conditions as a result of this discrimination. In Moldova, the government officials said that Roma refugees needed dedicated support for assistance in finding employment and ensuring their children attend school. In Poland, PRM partners stated that the Roma experience discrimination in receiving housing assistance and highlighted that there was only one out of 30 private and government shelters that accepted Roma refugees because of discrimination issues. Moreover, getting transportation to that center was difficult as it was 30 kilometers away from the train station.

· Documentation: Officials in both Moldova and Poland said that they face challenges when refugees do not have documents such as birth certificates or electronic registration already established for their identity. A PRM partner said that Ukrainian refugees without documentation are still processed and allowed through to Moldova, but they must report to authorities and complete additional paperwork. Moreover, a lack of documentation complicates partners’ efforts to avoid duplication of assistance. In addition, some individuals are stateless and do not have any documentation proving their identity. It is a time-consuming process for legal consultation and to obtain documents.

· Disinformation: A PRM official in Poland said there was a Russia disinformation campaign against refugees and there was a need to combat that campaign. A European humanitarian aid official in Moldova said that Russia disinformation challenged the Moldova government and international organizations and donors. A U.S. inspector general report described Russian disinformation campaigns in Europe that aimed to legitimize Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, promote regional instability, and erode Western institutions and their influence in the region.

· Access issues in Transnistria: PRM partners said that they were concerned about refugees in Transnistria because delivering and monitoring services in this area is difficult due to access issues. Transnistria, located in eastern Moldova, is a region of approximately 1,350 square miles and home to where about 367,000 people of Russian, Moldovan and Ukrainian descent. While generally recognized by the U.N. as part of Moldova, Transnistria has its own government and currency, and is economically, politically, and militarily supported by Russia, with an estimated 1,500 Russian troops stationed there. A PRM partner in Moldova said thousands of Ukrainian refugees have had challenges obtaining temporary protection status in Transnistria, as Ukrainian refugees must register for temporary protection status in Moldova first even though many enter directly from Ukraine.

USAID and State Closely Coordinated IDP and Refugee Assistance with Each Other and International Partners

BHA and PRM Generally Followed Leading Practices for Collaboration in Coordinating Ukraine Humanitarian Assistance

Between February 2022 and December 2024, BHA and PRM coordinated closely to implement humanitarian assistance in Ukraine and surrounding countries, guided by a global Memorandum of Understanding (MOU), signed between the two bureaus in January 2020. We analyzed the MOU as well as Ukraine-specific collaboration efforts as of December 2024 against eight leading practices we have previously identified to help agencies collaborate more effectively.[27] We found that between February 2022 and December 2024 BHA and PRM generally followed all eight leading practices described below (see fig. 14). Specifically, we found that through the MOU, and BHA’s and PRM’s implementation of it related to Ukraine, they (1) defined common outcomes; (2) ensured accountability; (3) bridged organizational cultures; (4) identified and sustained leadership; (5) clarified roles and responsibilities; (6) included relevant participants; (7) leveraged resources and information; and (8) developed and updated written guidance and agreements. In addition to the MOU, which guides BHA and PRM coordination on a global scale, BHA and PRM have other coordination mechanisms specific to assistance for Ukrainian IDPs and refugees that also followed many of these practices.

Define Common Outcomes

The MOU provides a framework for collaboration between BHA and PRM. Using this framework, both parties seek to build upon each other’s expertise, capacities, skills, and knowledge to support collaboration and communications on preparedness for, and response to, humanitarian crises. The MOU sets collaboration objectives such as:

· to strengthen external communication with donor governments, partners, and the public through joint messaging and joint planning processes,

· to improve internal information sharing, including for oversight and monitoring arrangements; and

· to promote more effective and efficient operational coordination through its coordination frameworks.

In the Ukraine context, other U.S. and international strategies we reviewed contained shared goals and outcomes for providing humanitarian assistance specifically to Ukrainian IDPs and refugees. These include the State and USAID Bureau for Europe and Eurasia/Bureau of European and Eurasian Affairs Joint Regional Strategy, the Ukraine Integrated Country Strategy, the HNRP, and the RRP. For example, one of the goals from the 2022-2026 USAID and State Joint Regional Strategy was to support emergency humanitarian assistance to displaced persons, vulnerable populations, and refugees inside and outside of Ukraine, particularly those bordering Ukraine with the goal of creating the conditions to allow refugees and displaced persons to return.

Ensure Accountability

BHA and PRM developed award-specific performance standards and oversight processes specific to their respective activities and partners to ensure accountability. For example, State and USAID’s standard operating procedures for joint field monitoring and assessments is intended to further enhance consistent collaboration between the two agencies in humanitarian contexts where they have programs.

At the working level, BHA and PRM also shared information about award due diligence and monitoring processes and requirements. PRM officials reported that they used this information to update their approaches to strengthen alignment. To ensure accountability at the country level, UN agencies also measured collective results, including those of BHA and PRM implementing partners. Results are included under the Ukraine HNRP for assistance inside Ukraine and through the RRP in other countries. The HNRP has two strategic objectives: to provide life-saving emergency assistance and to enable access to prioritized essential services, which are based on feedback from implementing partners and others. The UN tracked progress towards these goals through targets established in the HNRP.

Bridge Organizational Cultures

In their MOU, BHA and PRM developed strategies to share information and expertise, including agreeing upon principles for increased coherence in joint trainings. For example, BHA and PRM officials could attend courses that describe the function of each organization and an overview of international humanitarian assistance. The courses include other topics, like refugee and migration policy, and program portfolios. To bridge organizational cultures in providing assistance to Ukraine, agency officials noted that BHA’s Assistant to the Administrator and PRM’s Assistant Secretary met weekly to discuss higher-level engagement and decision making, coordinate to deconflict assistance, discuss joint policy and advocacy, and work to maintain a clear understanding of each other’s responsibilities. In Ukraine, officials from USAID’s Disaster Assistance Response Team stated that they also coordinated and worked closely with the PRM Refugee Coordinator in Kyiv from the beginning of the response.

Identify and Sustain Leadership

The MOU assigns both agencies specific responsibilities. It also states that in conflict situations, BHA and PRM have roles for responding to humanitarian needs. Lead responsibility does not preclude the other agency from its responsibilities to engage, but rather indicated who provides general direction and coordination of U.S. assistance in these areas. The MOU’s funding guidelines annexes provide further detail on coordination for shared responsibilities with respect to public international organizations, such as UNHCR and NGOs. They each have a shared responsibility in representing the U.S. government within the international humanitarian system, with UN humanitarian coordinators, and with humanitarian country teams.

At the global leadership level, officials stated that regular meetings between BHA’s assistant administrator and PRM’s assistant secretary helped support alignment and close coordination on high-level advocacy, prioritization, and funding where both USAID and State were providing assistance to IDP or refugee populations, as of December 2024. They also noted that the assistant administrator and assistant secretary also had regular meetings or calls about Ukraine during the timeframe of our review. Based on our review of meeting documents provided by BHA and PRM, staff who participated in the standing meetings also coordinated with ad hoc meetings and communications to share information, coordinate responses, and jointly prepare for relevant engagements.

Clarify Roles and Responsibilities

The MOU assigns lead roles and responsibilities to BHA and PRM regarding the types of beneficiaries they assist and the partners they work with. The MOU also includes a process for making decisions and guidelines for managing disputes. For example, if disputes cannot be resolved at the working level, the MOU describes procedures for escalating disputes to help ensure they are referred within ten business days.

BHA and PRM both had a role in Ukraine assisting IDPs, and they maintained a framework on who leads with certain funding partners within Ukraine. According to PRM officials, this helped to maintain a consistent and clear understanding of each Bureau’s respective responsibilities to the response and leverage the comparative advantages and longstanding relationships of each Bureau. For example, BHA led the US humanitarian response in Ukraine, but PRM led the institutional relationship with UNHCR in Ukraine (and Poland and Moldova) because of its longstanding relationship with the agency.

Include Relevant Participants

The MOU names BHA and PRM as the relevant participants with the appropriate knowledge, skills, and abilities to provide humanitarian assistance. Between February 2022 and December 2024, BHA and PRM met regularly in Washington, D.C. and Ukraine to coordinate and deconflict assistance and discuss joint policy and advocacy issues. According to USAID officials, USAID’s Ukraine Response Management Team enables USAID and State to coordinate their assistance. For example, the D.C.-based Response Management Team and the Kyiv-based Disaster Assistance Response Team coordinated and worked closely with PRM from the beginning of the response through December 2024, meeting regularly at the leadership and working levels to ensure alignment in messaging, strategy, and response activities. This included regular coordination activities at headquarters level in D.C. and in the field. In D.C. there are also working-level weekly or biweekly standing calls between the Response Management Team’s Coordination team and PRM’s Ukraine desk officers. PRM and BHA officials said that in Kyiv, there are regular meetings between PRM Refugee Coordinators and BHA’s Disaster Assistance Response Team lead, and monthly coordination meetings between PRM’s two locally employed staff and their BHA counterparts.

Leverage Resources and Information

In the MOU, the collaboration objectives are expected to be achieved through three coordination frameworks: two for public international organization partners and one for NGO partners. The coordination frameworks are used to share relevant data and information among the participants. The objective of the public international organization frameworks is to provide guidance to BHA and PRM staff to strengthen analysis, planning, and funding decisions. For example, the framework calls for BHA and PRM to hold twice-annual consultations to discuss joint strategies for engagement and planned funding with public international organizations receiving funding from both BHA and PRM, and they have met to do so.

According to PRM and BHA officials, between February 2022 and December 2024 they met often in Ukraine or the surrounding region and shared information and leveraged resources. PRM officials told us that BHA and PRM exchanged emails on key topics and discussions and provided clearances on each Bureau’s respective papers to ensure coordination. Our review of documents showed that BHA and PRM also regularly shared information such as briefers and briefer checklists for important meetings, fact sheets, and other official communications. BHA and PRM also coordinated on technical-level exchanges in the field, according to BHA officials. For example, according to USAID officials, USAID had a pool of local organizations that were strong candidates for PRM grants, and USAID shared that resource information with PRM.

Develop and Update Written Guidance and Agreements

The MOU and coordination frameworks that document the collaboration agreements between BHA and PRM were updated and reviewed within the specified timeframes. The framework states that BHA and PRM leadership intend to review the coordination frameworks every 2 years (or as requested) and update as required to address any gaps or challenges identified by staff through regular meetings. The MOU states that it should be reviewed every 5 years to determine if updates are required. It was negotiated and effective as of January 2020, and its complete annexes were last reviewed and updated for technical edits on January 13th, 2025.

In addition to the collaboration objectives in the MOU, the State and USAID E&E/EUR Joint Regional Strategy (2022-2026), the Ukraine Integrated Country Strategy (2023), and the 2025 HNRP and the 2025-2026 RRP have been updated regularly, and all contain shared goals and outcomes for providing humanitarian assistance to Ukrainian IDPs and refugees.

BHA and PRM Took Steps to Coordinate Their Assistance with Other Relevant USAID offices

In addition to BHA and PRM coordinating their humanitarian assistance with each other, they also coordinated their assistance with USAID’s Office of Transition Initiatives (OTI) and the relevant USAID missions as of December 2024. OTI provided transitional assistance and the USAID missions provided longer-term development assistance in Ukraine and Moldova.[28]

Both OTI and the missions provided assistance that could benefit IDPs and refugees. For example, OTI officials said that they had short-term activities in Ukraine that directly benefitted IDPs and other vulnerable populations, and they also provided indirect support to IDPs. OTI’s activities included assisting in civilian evacuations from frontline areas and providing fuel to Ukrainian and NGO service providers that supported these evacuations. USAID officials told us that USAID’s missions in Ukraine and Moldova provided development assistance in their respective countries that benefited Ukrainian IDPs and refugees, either directly or indirectly. For example, in Moldova in early 2022, USAID Moldova expanded programs where possible to accommodate increased needs for vulnerable people in Moldova, which often included Ukrainian refugees. One of the programs was designed to disseminate information and support refugees to document potential war crimes in Ukraine.

BHA Coordination with OTI and USAID Missions

The relevant USAID missions, OTI, and BHA met as needed to discuss programs and activities, according to USAID officials. For example, OTI and BHA staff in Kyiv and in Washington reported having both scheduled and informal meetings to share updates on their activities and coordinate efforts.

In addition, according to mission officials, the USAID mission coordinated regularly with BHA in Ukraine through meetings and working groups that are designed to link humanitarian assistance and development programs. For example, the USAID mission engaged regularly with BHA in the internal Nexus working group, which focused on coordination between humanitarian and development programs. BHA also shared information on their humanitarian assistance programming during mission staff meetings, one-on-one meetings with the mission’s technical offices, and in consolidated briefs and mission documents. USAID mission officials told us that they also invited BHA to attend the weekly senior staff meeting as well as quarterly implementing partners meetings, which included implementing partners of both humanitarian and development assistance.

PRM Coordination with OTI and USAID Missions

PRM also coordinated both directly and indirectly with OTI and the missions, according to PRM and USAID officials. OTI officials said they produced and distributed biweekly reports on its activities, events, and program insights, which were shared with colleagues at the U.S. Embassy in Kyiv, including those from BHA and PRM. OTI also produced ad hoc reports on urgent activities and lines of effort to ensure the U.S. offices operating out of the embassy in Kyiv were apprised of its most recent activities. PRM officials added that they met as needed with OTI staff in Kyiv to share priorities, programming, and ensure deconfliction. For example, according to officials, PRM and OTI engaged on issues related to children and IDP legislation. According to both PRM and OTI officials, ad hoc engagement was sufficient.

USAID mission officials in Ukraine told us that coordination with PRM primarily occurred through BHA. However, the mission in Ukraine and PRM coordinated directly as needed to discuss USAID programming and any potential overlap with PRM’s programs, according to officials and documentation. This was done through regular meetings, joint engagement in donor working groups, joint engagement in embassy working groups, and collaboration on written documents. For example, when there was potential for an overlap in issues, such as children’s health, PRM and the mission’s Health Team coordinated attendance and talking points at meetings with the government of Ukraine.

USAID and State Used Established Mechanisms to Coordinate Their Assistance with International Partners

Between February 2022 and December 2024, BHA and PRM coordinated their assistance in Ukraine with international partners primarily through the UN humanitarian cluster system, the main mechanism for coordinating humanitarian assistance in Ukraine. In Poland and Moldova, PRM coordinated its assistance primarily through the Refugee Coordination Forum in each country.

Cluster System in Ukraine

BHA officials told us that BHA and PRM primarily coordinated their humanitarian assistance in Ukraine with international partners, including the Ukrainian government, through the UN cluster system. The clusters meet regularly to coordinate assistance and have meetings at various levels. For example, UN officials told us that many clusters hold:

· national-level monthly meetings with donors, researchers, and local authorities. The frequency of these meetings has changed over time and were more frequent at the beginning of the war.

· sub-national operational meetings at the regional level that typically occur once a month or once every three months, depending on the location and the associated needs.

· sector-specific technical working groups that may meet as frequently as once a week.