HOMELAND SECURITY

Office of Intelligence and Analysis Should Improve Strategic Oversight of Intelligence Enterprise

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Tina Won Sherman at shermant@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107540, a report to congressional requesters

Office of Intelligence and Analysis Should Improve Strategic Oversight of Intelligence Enterprise

Why GAO Did This Study

Violent extremists and adversarial nation-states pose a complex set of threats to the U.S. Addressing these threats requires coordinated intelligence sharing across the DHS Intelligence Enterprise—the primary method to integrate DHS’s intelligence programs. Led by I&A, it includes the intelligence offices of nine other DHS components. Internal DHS reviews have proposed enhancements to I&A’s oversight and coordination roles for the enterprise.

GAO was asked to review issues related to I&A’s oversight of the DHS Intelligence Enterprise. This report addresses the extent to which I&A is (1) conducting its required strategic oversight, and (2) addressing leading practices in its required collaboration with the DHS Intelligence Enterprise.

GAO reviewed DHS policies for I&A’s strategic oversight requirements and enterprise collaboration efforts. GAO interviewed management officials from all enterprise components. GAO conducted discussion groups with analysts in three components and three I&A analytic centers that collaborate most frequently with I&A on intelligence products. Finally, GAO compared I&A efforts to leading collaboration practices.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making seven recommendations to DHS, including that I&A develop and implement procedures to complete its required strategic oversight activities. DHS concurred with the recommendations.

What GAO Found

The Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) Office of Intelligence and Analysis (I&A) has four primary strategic oversight requirements based in statute and policy: develop (1) an annual consolidated budget proposal, (2) an annual intelligence priorities framework, (3) enterprise program reviews and submit an evaluation report annually to the DHS Secretary, and (4) intelligence training for enterprise staff.

Although these have been policy requirements since 2013, GAO found that I&A has not consistently completed them due to a lack of leadership focus. For example, I&A had not fulfilled its requirement to propose a consolidated budget for the Intelligence Enterprise until fiscal year 2025. Developing and implementing procedures to develop a consolidated budget would help I&A complete this annual requirement. In turn, this would help ensure components are budgeting the necessary resources to share intelligence on threats.

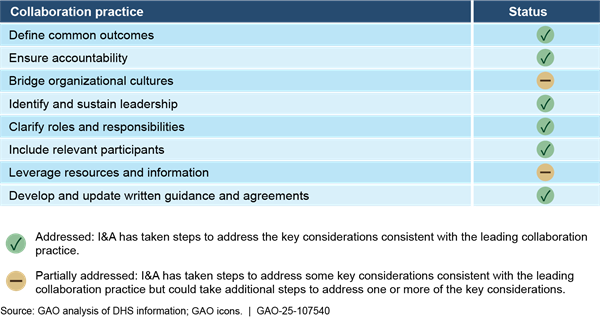

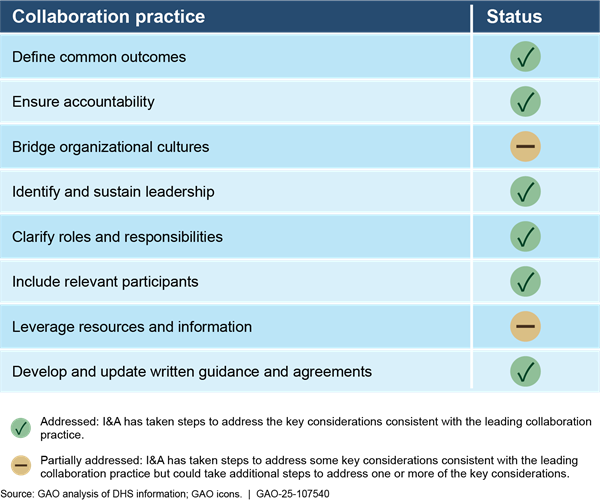

GAO found that I&A addressed six of eight leading collaboration practices. For example, I&A ensured accountability for enterprise-wide activities by establishing performance standards to evaluate collaboration.

However, I&A has partially addressed two of eight practices. For instance, with respect to the leading practice of leveraging resources and information, GAO found that at the time of its review, I&A lacked a process to identify experts in relevant components to coordinate on reviews of intelligence products. According to I&A and component analysts this has caused errors in products. In June 2025, I&A finalized a coordination list of experts, but it is too soon to tell if it is working as intended. Fully implementing this process could help I&A ensure its product reviews are more robust and avoid publishing inaccurate or incomplete information.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

DHS |

Department of Homeland Security |

|

I&A |

Office of Intelligence and Analysis |

|

CBP |

U.S. Customs and Border Protection |

|

CISA |

Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

July 16, 2025

Congressional Requesters

Violent extremists, transnational criminal organizations, and adversarial nation-states pose a complex set of threats to U.S. public safety, border security, critical infrastructure, and the economy. These threats underscore the need for coordinated intelligence and information sharing across Department of Homeland Security (DHS) entities. Within DHS, the Office of Intelligence and Analysis (I&A) is responsible for accessing, receiving, and analyzing intelligence and information from various sources to support the Department’s missions.[1] To help with this mission, DHS policy requires that I&A provide strategic oversight of the DHS Intelligence Enterprise, which is the primary mechanism to integrate and manage DHS’s intelligence programs, projects, and activities.[2] The Intelligence Enterprise is composed of I&A and the intelligence offices from nine DHS components and led by the DHS Chief Intelligence Officer, who is also the DHS Under Secretary for Intelligence and Analysis.[3]

Members of Congress and others have raised questions about I&A’s oversight of the Intelligence Enterprise. In March 2017, the DHS Office of Inspector General found a lack of coordination between I&A and Intelligence Enterprise components and recommended that I&A formalize collaboration procedures for field personnel.[4] This recommendation was open as of May 2025.[5] More recently, DHS reviews have identified proposed enhancements to I&A’s oversight and coordination roles for the Intelligence Enterprise.[6]

In light of this, you asked us to review issues related to I&A’s oversight of the DHS Intelligence Enterprise. This report addresses the extent to which DHS I&A (1) is conducting its required strategic oversight of the DHS Intelligence Enterprise; and (2) is addressing leading practices in its required collaboration with the DHS Intelligence Enterprise.

To address our objective on strategic oversight requirements, we reviewed applicable statutes and DHS policies to determine I&A’s authorities, roles, and responsibilities for strategic oversight of the Intelligence Enterprise. To determine the extent to which I&A was executing its primary strategic oversight requirements, we reviewed documentation about I&A’s ongoing and planned actions to fulfill these requirements and discussed such actions with relevant officials. We assessed I&A’s efforts to develop and document procedures for its primary strategic oversight requirements against the control activities component of Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government—specifically the principle that management should implement control activities through policies and document such policies—and select project management standards.[7]

To address our objective on collaboration, we reviewed documentation related to I&A’s collaboration with Intelligence Enterprise components. We also discussed I&A’s collaboration activities and their benefits and challenges during interviews with I&A headquarters officials and Intelligence Enterprise management officials from the nine DHS components we identified.[8]

In addition, we conducted discussion groups with a nongeneralizable sample of analysts at three of the nine Intelligence Enterprise components. In selecting the three components, we prioritized the components with which I&A either co-produced or coordinated the most finished intelligence products from fiscal year 2022 through June 30, 2024. We also conducted similar discussion groups with analysts from three of I&A’s four analytic centers that interacted most frequently with the components we selected. While the information we obtained from these interviews cannot be generalized to all Intelligence Enterprise components and I&A analysts, the discussions provided a range of valuable perspectives regarding I&A’s collaboration with the Intelligence Enterprise.

Finally, we compared I&A’s Intelligence Enterprise collaboration activities against eight leading collaboration practices identified in our prior work.[9] We determined if I&A actions either addressed or partially addressed the leading practice. For the leading collaboration practices that I&A partially addressed, we further assessed I&A’s actions against project management standards.[10]

For more information on our scope and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from May 2024 through July 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Key Roles within the DHS Intelligence Enterprise

I&A, specific offices within the nine other DHS Intelligence Enterprise components, and the Homeland Security Intelligence Council play key roles within the DHS Intelligence Enterprise.

I&A

The Under Secretary for Intelligence and Analysis holds the role of DHS Chief Intelligence Officer.[11] In that capacity, the Under Secretary, through I&A, is to lead the DHS Intelligence Enterprise, which includes coordinating and integrating among its components, and conducting strategic oversight.[12] I&A, therefore, must also lead efforts to coordinate and deconflict national and departmental intelligence through the Intelligence Enterprise.[13]

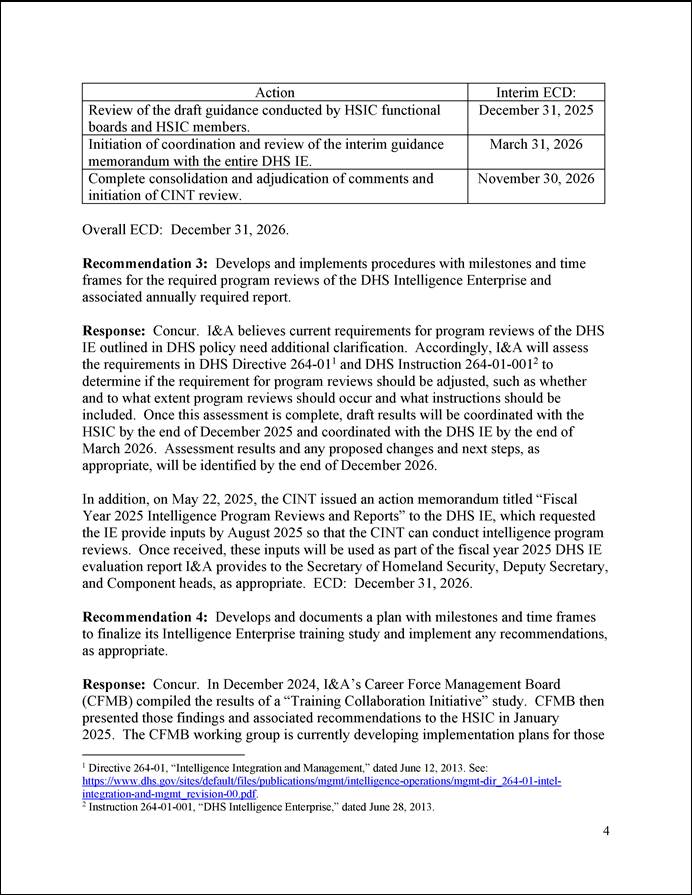

In addition to its leadership of the DHS Intelligence Enterprise, I&A is a member of the U.S. Intelligence Community and is to facilitate departmental coordination with it.[14] Figure 1 identifies the components of the DHS Intelligence Enterprise, including the two that are also members of Intelligence Community.

Figure 1: Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Components Comprising the DHS Intelligence Enterprise

Notes: The Office of Intelligence and Analysis is a member of the U.S. Intelligence Community. It also leads the DHS Intelligence Enterprise. The U.S. Coast Guard is both a member of the DHS Intelligence Enterprise and an independent member of the Intelligence Community. 50 U.S.C. § 3003(4) (designating the U.S. Coast Guard and DHS Office of Intelligence and Analysis as members of the Intelligence Community).

Component Intelligence Programs

I&A works directly with specific offices within the nine other DHS Intelligence Enterprise components responsible for intelligence-related work. These offices—Component Intelligence Programs—review intelligence and other information to produce intelligence products.[15] For example, within U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), the Office of Intelligence is the Component Intelligence Program. It produces intelligence products for CBP border security operations. Intelligence Enterprise components may have more than one entity within them that makes up their Component Intelligence Program. For example, the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) is one Component Intelligence Program with two entities—CISA Intelligence and the Component Counter-Intelligence Element. We discuss issues related to I&A’s processes for updating the list of Intelligence Enterprise components later in this report.

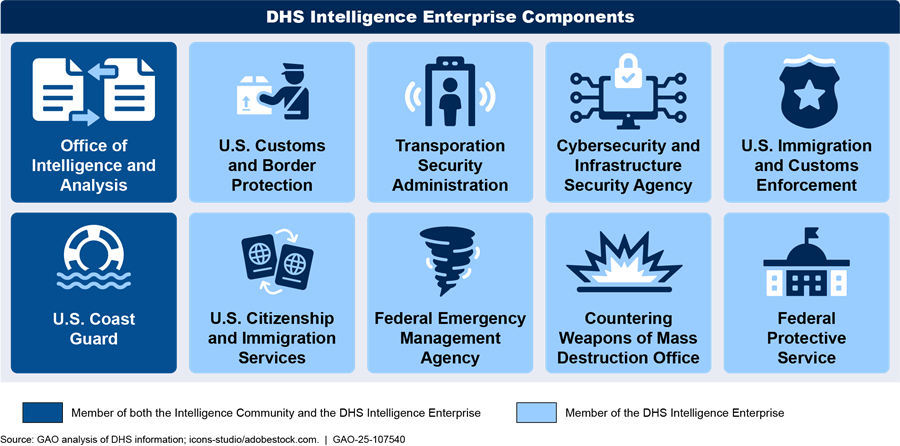

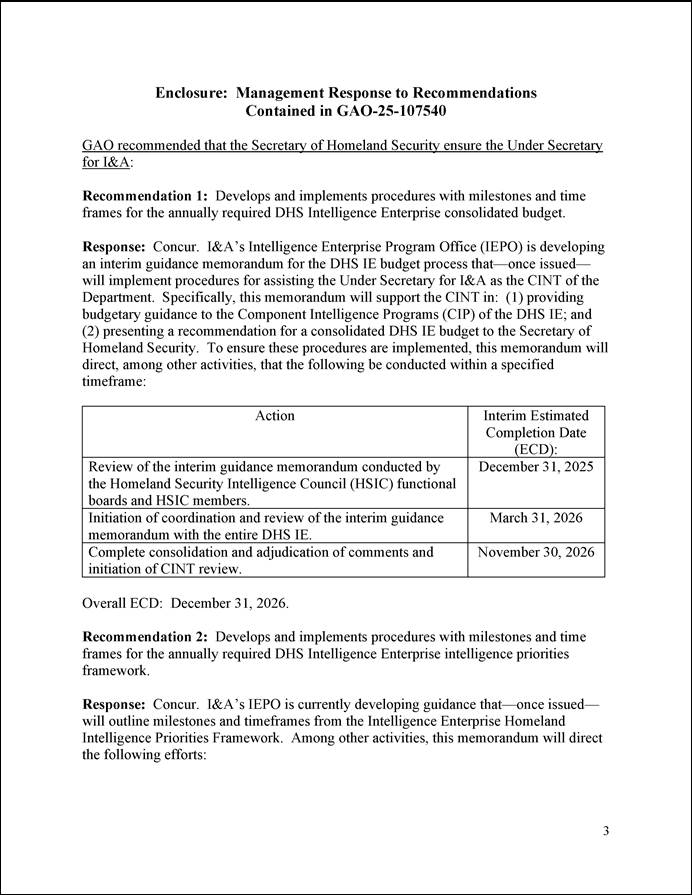

Homeland Security Intelligence Council

Established through a charter in 2009, the Homeland Security Intelligence Council assists the Under Secretary for Intelligence and Analysis in performing strategic oversight of the Intelligence Enterprise. As shown in Figure 2, the council includes six functional boards, each of which focuses on a specific topic. The Under Secretary for Intelligence and Analysis appoints Intelligence Enterprise components to co-chair the functional boards.

![]()

aThe DHS Intelligence Enterprise is composed of I&A and the intelligence components of the following DHS entities: the Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction Office, the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, Federal Protective Service (within the Management Directorate), the Transportation Security Administration, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, U.S. Coast Guard, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

bFunctional board co-chairs are current as of March 2025.

cThe Office of the Chief Security Officer in the Management Directorate is not a member of the DHS Intelligence Enterprise. However, I&A officials told us the office is a co-chair on the Counterintelligence and Security Board because of its subject matter expertise.

I&A’s Responsibilities for Strategic Oversight of the Intelligence Enterprise and Its 2023 Reorganization

I&A’s authority for strategic oversight of the Intelligence Enterprise is found in both statute and policy. For some activities, DHS policy both restates and expands upon the roles and responsibilities outlined in statute. For example, I&A is statutorily responsible for providing training and guidance on the collection, processing, analysis, and dissemination of information on homeland security and national intelligence for employees, officials, and others within DHS intelligence components.[16] DHS policy restates this responsibility and provides further details, such as which branch is responsible for developing, advertising, and presenting the training.[17]

Conversely, some responsibilities outlined in DHS policy are related to I&A’s statutory responsibility for strategic oversight but are not specifically identified in statute. For example, I&A, with input from Intelligence Enterprise components, is to annually develop the Homeland Intelligence Priorities Framework (a list of intelligence topics ranked by priority) to integrate the priorities of the Intelligence Enterprise.[18] Table 1 identifies I&A’s four primary strategic oversight activities and requirements for the Intelligence Enterprise.

Table 1: Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Office of Intelligence and Analysis (I&A) Primary Strategic Oversight Requirements and Activities for the DHS Intelligence Enterprise

|

Intelligence Enterprise strategic oversight requirement |

Description of strategic oversight activitiesa |

|

Develop a consolidated budget |

With input from Intelligence Enterprise components, I&A is to review each Component Intelligence Program’s proposed budget annually and incorporate them into a consolidated budget for presentation to the Secretary of Homeland Security.b |

|

Develop the Homeland Intelligence Priorities Frameworkc |

With input from Intelligence Enterprise components, I&A is to develop the Homeland Intelligence Priorities Framework annually to integrate the priorities of the Intelligence Enterprise. The framework is a ranked and prioritized list of national and departmental intelligence topics intended to serve as the guide for the DHS Intelligence Enterprise activities. |

|

Conduct intelligence program reviews and prepare an evaluation report |

I&A is to review Intelligence Enterprise Component Intelligence Programs periodically and submit the results in an annual evaluation to the Secretary of Homeland Security. |

|

Provide intelligence training |

I&A is to train Intelligence Enterprise employees and executives on developing the knowledge to collect, gather, process, analyze, produce, and disseminate intelligence. |

Source: GAO analysis of statute (6 U.S.C. §§ 121, 124e) and DHS policy. | GAO‑25‑107540

aWe refer to I&A’s strategic oversight requirements, which I&A is to conduct through the Under Secretary for Intelligence and Analysis in their role as Chief Intelligence Officer.

bWe use the term “consolidated budget” to refer to I&A’s responsibility in policy and statute to present the Secretary with a recommendation for a consolidated budget for the intelligence components of the Department, together with any comments from the heads of such components. 6 U.S.C. § 121(d)(21)(B); Department of Homeland Security, DHS Intelligence Enterprise, Instruction 264-01-001 (Washington, D.C.: June 28, 2013). The recommended consolidated budget that I&A presents to the Secretary does not represent a finalized budget, nor does it represent what Intelligence Enterprise components may ultimately receive from the appropriations process.

cWhile DHS policy refers to the framework as the Homeland Security Intelligence Priorities Framework, I&A shortened the name to the Homeland Intelligence Priorities Framework. I&A also develops an Intelligence Priorities Framework specific to I&A. We use the term “Homeland Intelligence Priorities Framework to refer to the Intelligence Enterprise framework, not the I&A framework.

I&A has had three major organizational realignments since 2015. The first two realignments, in 2018 and 2022, did not involve I&A responsibilities for leading the Intelligence Enterprise. In contrast, I&A’s most recent organizational realignment in May 2023 responded to recommendations from an I&A review of its mission and management practices initiated in June 2022. The review found I&A historically had not had the organizational structure to fully execute its coordination and strategic oversight of the Intelligence Enterprise. As a result, in May 2023, I&A established the Intelligence Enterprise Program Office to provide strategic, administrative, and functional support to the Under Secretary and to ensure that I&A carries out its strategic oversight requirements for the enterprise.

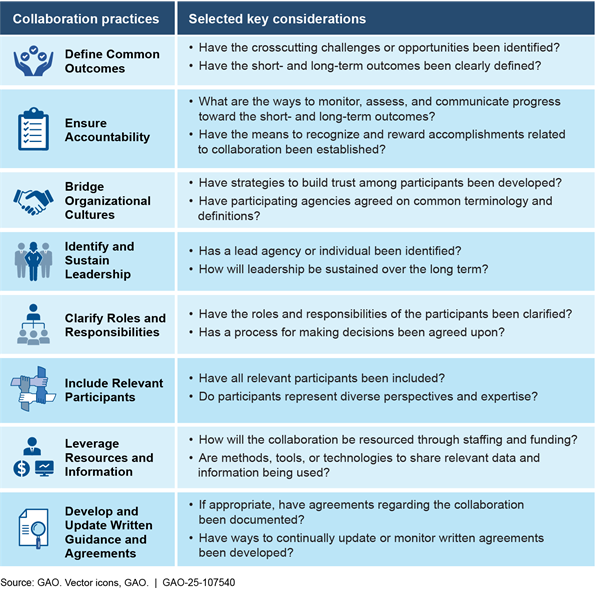

GAO’s Leading Collaboration Practices

In our prior work, we found that effective collaboration—such as collaboration among the DHS Intelligence Enterprise components—benefits from implementing certain leading practices such as defining common outcomes and clarifying roles and responsibilities.[19] Figure 3 shows eight practices for agency officials to consider when working collaboratively.

DHS I&A Has Not Fully Implemented Required Intelligence Enterprise Strategic Oversight Activities

I&A Has Not Consistently Completed a Consolidated Budget, Intelligence Priorities Framework, or Reported Results of Its Program Reviews, as Required

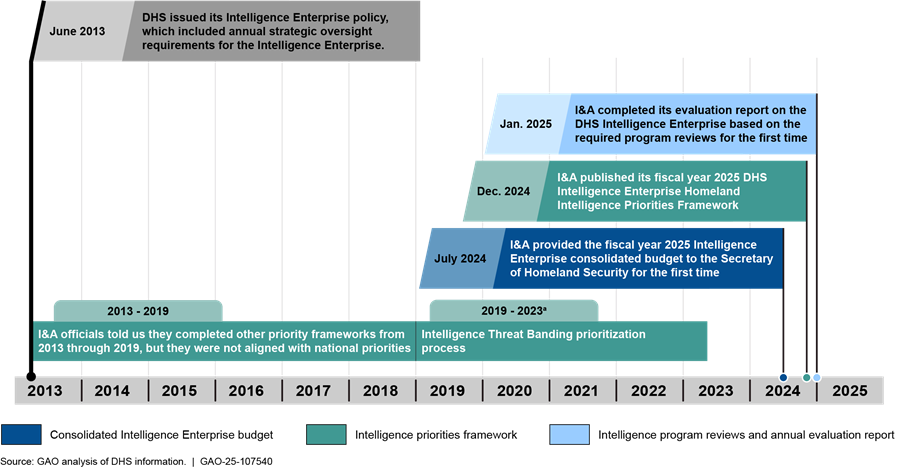

Since 2013, DHS I&A has been required by policy to perform three annual strategic oversight activities for the Intelligence Enterprise—namely, developing a consolidated budget and an intelligence priorities framework, and reporting the results of its intelligence program reviews—but it has not consistently done so.[20] For example, I&A had not developed a consolidated budget until fiscal year 2025 or reported the results of its intelligence program reviews until fiscal year 2024. Furthermore, as of June 2025 I&A has not developed and implemented procedures to ensure that it will continue to meet these annual requirements. Figure 4 provides additional details on I&A’s implementation of these annual strategic oversight requirements for the DHS Intelligence Enterprise.

Figure 4: Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Office of Intelligence and Analysis (I&A) Implementation of Primary Annual Strategic Oversight Requirements for the DHS Intelligence Enterprise, 2013-2025

aAccording to I&A officials, as of May 2023, they paused Intelligence Threat Banding. See GAO, Homeland Security: Office of Intelligence and Analysis Should Improve Privacy Oversight and Assessment of Its Effectiveness, GAO‑23‑105475 (Washington, D.C.: Aug. 28, 2023).

Consolidated budget. Although a 2013 DHS policy required that I&A develop an annual, consolidated Intelligence Enterprise budget, I&A had not fulfilled this requirement until July 2024.[21] Fiscal year 2025 was the first time I&A provided the consolidated budget to the Secretary of Homeland Security. To develop the consolidated budget, I&A—working through the Homeland Security Intelligence Council’s Strategy, Plans, and Resources Board—provided instructions and a template to Intelligence Enterprise components.[22] It requested data on component’s intelligence programs, projects, activities, and staff. Intelligence Enterprise management officials from four of the nine components we spoke with told us they also had preliminary discussions about the consolidated budget effort during which I&A sought their input on the process.

I&A officials told us that establishing a baseline consolidated budget to better understand departmental spending on intelligence activities is foundational to its oversight of the Intelligence Enterprise. Furthermore, I&A officials explained that they expect the usefulness of the Intelligence Enterprise budget will increase moving forward.

Officials told us in March 2025 that they are working on guidance for the consolidated budget process but are deferring publication of the guidance to coincide with the next DHS-wide resource allocation planning process. I&A officials estimate the guidance will be completed by December 2026 and they told us it will outline an annual repeatable process. I&A officials from the Intelligence Enterprise Program Office also said they plan to incorporate lessons learned from this year’s process into next year’s process. However, as of June 2025, I&A had not provided any draft procedures or other documentation to demonstrate progress towards it December 2026 goal.

Intelligence priorities framework. Although I&A has been required by DHS policy to develop an intelligence priorities framework annually since 2013, it has not done so consistently. For example, I&A officials told us they completed other priority frameworks from 2013 through 2019, but they were not aligned with national priorities, as required by policy. I&A also conducted a version of a priority framework from 2019 through 2023—Intelligence Threat Banding.[23] In December 2024, I&A published its fiscal year 2025 DHS Intelligence Enterprise Homeland Intelligence Priorities Framework.[24] To create the framework, I&A provided instructions and a template to Intelligence Enterprise components requesting that they rank a list of national and departmental subtopics from highest to lowest priority.

Intelligence Enterprise management officials we spoke with said the process they performed to produce the fiscal year 2025 framework was an improvement over Intelligence Threat Banding because the process was clearer. Therefore, I&A officials told us they plan to use the process they developed for fiscal year 2025 moving forward. I&A also emphasized the importance of updating the framework annually to reflect changes in the threat environment.

Although I&A plans to use the fiscal year 2025 process moving forward, I&A has not yet developed and implemented standard operating procedures with milestones and time frames to ensure the process takes place annually. I&A officials told us in March 2025 that they had drafted guidance for the Homeland Intelligence Priorities Framework process that contains milestones and time frames, but it is currently under review. I&A officials estimate the guidance will be completed by December 2026. However, as of June 2025, I&A had not provided any draft procedures or other documentation to demonstrate progress towards its December 2026 goal.

Intelligence program reviews and annual evaluation report. Although I&A has been required by DHS policy to annually report the results of its periodic intelligence program reviews since 2013, it had not fulfilled this requirement until January 2025 when it completed its fiscal year 2024 report. According to I&A officials, they combined the policy requirement to produce an annual evaluation report on the Intelligence Enterprise with I&A’s annual report to congressional intelligence committees required by the Intelligence Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2015.[25]

To complete the fiscal year 2024 report, I&A conducted program reviews of Intelligence Enterprise components by providing a template to components for them to provide details on staffing, technology, and intelligence products. Prior to the 2024 review, I&A inconsistently conducted the program review requirement. For example, I&A officials told us that in previous years they conducted program reviews through informal discussions with Intelligence Enterprise component officials, but did not document the results. Further, as of June 2025, I&A has not developed and implemented procedures—including milestones and time frames for components to provide the required information—to ensure the program review process is done periodically and the resulting evaluation report is done annually.

Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government state that management should implement and document control activities—such as I&A’s Intelligence Enterprise consolidated budget, priorities framework, and program review and associated annual evaluation report efforts—through policies and procedures.[26] In addition, project management standards state that organizations should estimate the duration of activities and create a schedule, such as milestones and time frames, to execute them.[27]

In a September 2023 memo to the Secretary of Homeland Security, I&A noted that its strategic oversight responsibilities, such as the consolidated budget and the intelligence priorities framework, have not been prioritized because of a lack of I&A leadership focus on these issues. Furthermore, in March 2025, I&A officials told us the agency has limited capabilities to exercise strategic oversight of the intelligence activities of other components with its existing resources.

Although I&A previously developed instructions to assist components in developing a consolidated budget, priorities framework, and completing intelligence program reviews, these instructions were limited to one fiscal year or budget cycle and did not ensure the annual completion of these strategic oversight requirements on a routine basis. Developing and implementing procedures with milestones and time frames for providing information would help I&A standardize its annual strategic oversight requirements for the Intelligence Enterprise, even if leadership is not focused on these responsibilities. Specifically, developing and implementing such procedures for these three requirements would help ensure I&A has the key information to meet its annual requirements. Furthermore, by developing a consolidated budget and a priorities framework for the enterprise, and reporting the results of its intelligence program reviews, I&A would be better positioned to ensure that components are coordinating and sharing intelligence and other information to address threats.

I&A Has Not Completed Efforts to Improve Its Intelligence Enterprise Training

I&A has had challenges implementing efforts to improve its Intelligence Enterprise training program that would help meet its statutory and policy requirements to coordinate and provide training and guidance for Intelligence Enterprise staff.[28] Intelligence Enterprise training covers topics to help DHS intelligence professionals develop foundational skills to more effectively deliver an intelligence brief or draft intelligence products. To help meet these requirements, I&A—through the Homeland Security Intelligence Council’s Career Force Management Board—initiated the Training Collaboration Initiative in September 2023. I&A tasked the board with studying long-standing issues, such as curriculum updates, classroom facility improvement, and instructor availability and certifications.

I&A’s Training Collaboration Initiative is built on a prior study I&A commissioned in 2019. That study made several recommendations that I&A update its training curriculum, improve classroom facilities, and increase instructor availability, among other things. However, officials said I&A did not fully implement the recommendations from the 2019 study because of changes during the COVID-19 pandemic, such as a shift to virtual training. According to I&A officials, they initiated the September 2023 study to revisit training needs after the pandemic.

Management officials from six of eight DHS Intelligence Enterprise components we spoke with, as well as I&A officials responsible for training administration, identified challenges with I&A’s Intelligence Enterprise training.[29] For example, officials from four components said that their personnel have difficulty getting into I&A courses because the course demand exceeds capacity, and officials from two components said the course material is not always relevant to their personnel. In addition, I&A training officials described challenges, such as tailoring courses to suit personnel from across the Intelligence Enterprise with varying missions.

As of March 2025, I&A had not completed the Training Collaboration Initiative. Specifically, I&A officials told us that the Career Force Management Board had finished the report, which identifies training issues, and its recommendations were to be presented to the Homeland Security Intelligence Council in June 2025. I&A anticipates that the Under Secretary, in coordination with the Homeland Security Intelligence Council, will determine which recommendations from the Training Collaboration Initiative to implement by January 2026.

I&A officials said that there have been changes in I&A leadership since 2019 with differing visions for training. This, among other issues, has hindered its ability to develop time frames to complete the current study—the Training Collaboration Initiative—or implement any recommendations from the 2019 study that remain relevant. Project management standards state that organizations should estimate the duration of activities and create a schedule, such as milestones and time frames, to execute them.[30]

By developing and documenting a plan that includes milestones and time frames for completing the Training Collaboration Initiative report and implementing any recommendations, as appropriate, I&A would be better positioned to ensure it is fully meeting its requirement to provide training to enhance the skills of intelligence professionals across the Intelligence Enterprise.

I&A Has Facilitated Collaboration within the Intelligence Enterprise by Addressing Most, but Not All, Leading Practices

I&A Has Addressed Most Leading Practices for Collaboration

I&A has addressed six of eight leading collaboration practices for the DHS Intelligence Enterprise identified in our prior work.[31] For example, I&A addressed one collaboration practice—ensure accountability—by establishing performance standards to evaluate collaboration. Specifically, I&A assesses individual analysts’ collaboration with their Intelligence Enterprise counterparts in their annual performance evaluations by measuring the extent to which they share information.

To help address another leading collaboration practice—develop and update written guidance and agreements—I&A developed key guidance documents and agreement memoranda that address collaboration across the Intelligence Enterprise. For example, I&A issued several memoranda in September 2023 that charged the functional boards of the Homeland Security Intelligence Council to lead efforts to implement the various requirements discussed earlier in this report, such as the consolidated budget. See appendix II for more details on how I&A has addressed leading collaboration practices.

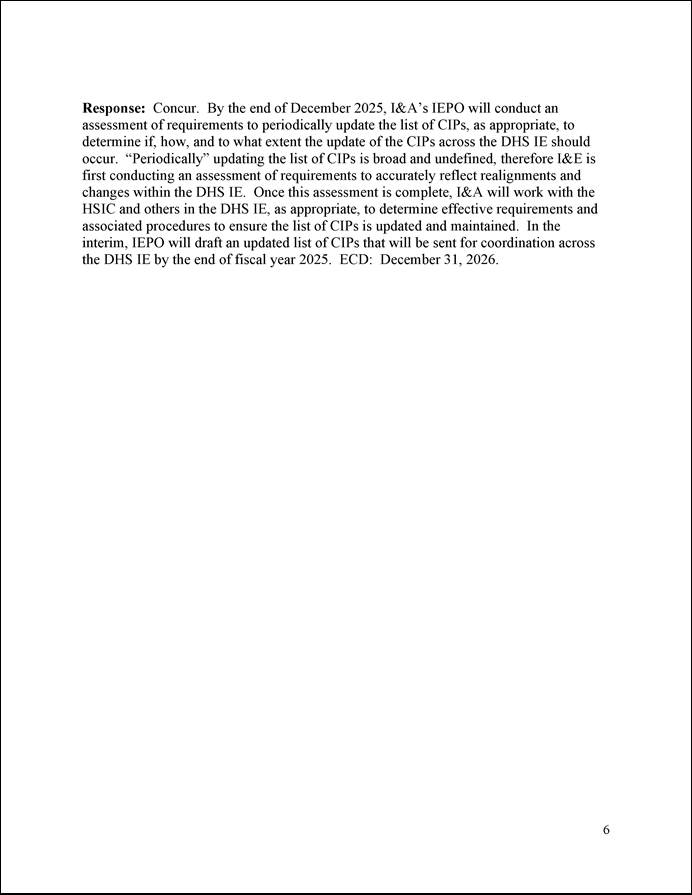

However, we also found that I&A has partially addressed two of eight leading collaboration practices: leverage resources and information and bridge organizational cultures. I&A has not leveraged resources and information for reviewing intelligence products for accuracy because it has not yet fully implemented its June 2025 process for finished intelligence product coordination. In addition, I&A has not bridged organizational cultures because it has not completed its efforts to address inconsistent designations of Component Intelligence Programs. Figure 5 provides I&A’s status in addressing leading collaboration practices for the Intelligence Enterprise.

Figure 5: Status of Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Office of Intelligence and Analysis (I&A) Actions to Collaborate with the DHS Intelligence Enterprise that Address Leading Practices

I&A Has Not Fully Implemented Its Process for Coordinating Product Reviews

At the time of our review, I&A lacked a process for Intelligence Enterprise components to review relevant information for accuracy when coordinating finished intelligence products. Finished intelligence products provide actionable intelligence for operational and policy-level decision-making to stakeholders outside of DHS. Finished intelligence products can contain the assessment, judgment, analytic conclusions, or other analytic input of personnel from multiple Intelligence Enterprise components. It is important that subject matter experts across the enterprise review products that contain information and analytic views relevant to their component. Therefore, as part of its Intelligence Enterprise oversight responsibilities identified in DHS policy, I&A is required to coordinate and deconflict DHS intelligence activities, which includes coordinating reviews of finished intelligence products. To carry out this process, analysts are to send their drafts to other Intelligence Enterprise components for their concurrence or disagreement with the report’s content.

However, at the time of our review, I&A did not ensure Intelligence Enterprise analysts sent their drafts to analysts at other components with the appropriate expertise. For instance, management officials from eight of nine components said that I&A generally had not instituted a process for coordinating finished intelligence products. In addition, officials at both I&A and Intelligence Enterprise components told us analysts have not consistently coordinated products with each other, despite I&A’s acknowledgment that finished intelligence product coordination is a best practice. Component management officials told us that product coordination was dependent on relationships between analysts at Intelligence Enterprise components. However, management officials at six of nine Intelligence Enterprise components described issues with the relationship-based product coordination process.

Similarly, I&A officials told us there have been instances when I&A analysts did not obtain feedback or concurrence from their Intelligence Enterprise counterparts with relevant expertise on high-profile I&A products. Intelligence Enterprise management officials also said I&A sent product coordination requests to the wrong points of contact at their respective component or did not send such requests at all. In addition, analysts from two of three Intelligence Enterprise components we spoke with said they lacked updated contact information for subject matter experts at I&A.

According to analysts from I&A and two of three Intelligence Enterprise components we spoke with, a lack of coordination between analysts drafting intelligence products and components’ subject matter experts has led to the publication of errors in those products. For example, I&A analysts from one analytic center told us that an Intelligence Enterprise component published a finished intelligence product under the DHS seal that was factually wrong. Published products that contain factually wrong information could negatively impact the intelligence used in operational and policy-level decision-making.

In January 2024, I&A, working through the Homeland Security Intelligence Council’s Analysis and Production Board, initiated efforts to improve Intelligence Enterprise-wide product coordination for finished intelligence products. This effort included working with the heads of Intelligence Enterprise components to develop (1) a list of required coordinators and (2) a requirement that components develop corresponding internal processes for product coordination that align with Intelligence Community standards on product coordination. The coordinator list was to identify components that should be consulted for products addressing certain intelligence topics, along with subject matter experts on relevant topics from each Intelligence Enterprise component.[32] The corresponding internal processes would outline how each Intelligence Enterprise component would obtain from other components feedback, concurrence, or dissent on draft products. I&A was to complete these efforts by January 2025.

After we submitted our report to DHS for review and comment, I&A provided the finalized coordination list that it sent to components in June 2025. However, I&A did not provide documentation of the corresponding component processes—one of the two improvement efforts outlined in January 2024. Therefore, it is too soon to determine whether I&A and enterprise components are fully implementing the June 2025 product coordination process. Leading practices for collaboration identified in our prior work state that agencies should leverage resources and information, which includes ensuring that methods—such as I&A’s finished intelligence coordination process—are being used as intended.[33]

By taking steps to ensure that the heads of Intelligence Enterprise components are fully implementing the required product coordination process, I&A would have better assurance that the DHS Intelligence Enterprise has a method to leverage resources and information for product reviews. These steps could include ensuring that components have developed corresponding processes and are using the product coordination list as intended. Ensuring the relevant subject matter expertise for product coordination could also help DHS avoid the publication of inaccurate or incomplete products.

Intelligence Enterprise Components Have Inconsistently Designated Component Intelligence Programs

Component Intelligence Program Designations

Intelligence Enterprise components have inconsistently designated their Component Intelligence Programs, which could hinder I&A’s ability to provide strategic oversight of the Intelligence Enterprise. Regarding the designation of Component Intelligence Programs, the policy

1. States that any organization within a component should be designated as a Component Intelligence Program if it is significantly involved with the collection, gathering, processing, analysis, production, or dissemination of intelligence.[34]

2. Defines Component Intelligence Programs as any organization within a component that employs intelligence professionals from a specific intelligence job series.[35]

In addition, an August 2024 memorandum from the Under Secretary for Intelligence and Analysis said that components may consider either one or both criteria in the definition when identifying their Component Intelligence Programs.

Intelligence Enterprise components have applied I&A’s guidance on designating Component Intelligence Programs differently. For example, CBP employs intelligence job series professionals in offices outside of its Component Intelligence Program, the Office of Intelligence, but it does not consider the offices employing those positions to be separate Component Intelligence Programs.[36] I&A officials told us they consider the intelligence staff employed outside CBP’s Component Intelligence Program to conduct work that is a part of the Intelligence Enterprise’s mission. In contrast, CISA officials said they have staff in two offices who hold positions in the intelligence job series, both of which comprise their Component Intelligence Program. Additionally, the Federal Emergency Management Agency has four offices which comprise its Component Intelligence Program, three of which employ staff under the intelligence job series.

According to I&A officials, there is an inconsistent understanding of the entities that comprise Component Intelligence Programs because the policy that defines which entities are Component Intelligence Programs includes two definitions. I&A officials also told us that because of the differences in interpreting what comprises a Component Intelligence Program, the Under Secretary for Intelligence and Analysis could have an incomplete understanding of which component activities should be included in its oversight. For example, officials said the Under Secretary may not include all of a component’s intelligence activities in its consolidated budget and priorities framework if these activities are not included as part of the component’s Component Intelligence Program.

Leading practices for collaboration identified in our prior work state that agencies should bridge organizational cultures by using common terminology—such as a common definition of a Component Intelligence Program—in collaborative efforts.[37] In April 2024, the Under Secretary for Intelligence and Analysis issued a memorandum stating I&A had plans to update and clarify the policy that defines a Component Intelligence Program. I&A officials told us that clarifying the definition of a Component Intelligence Program would help ensure that its strategic oversight encompasses all staff who conduct intelligence activities. However, as of June 2025, I&A had not yet completed the effort. By updating and clarifying the policy definition of Component Intelligence Program, I&A would be better able to bridge organizational cultures across the enterprise and ensure that all staff within components who conduct intelligence-related work are included in I&A’s strategic oversight efforts.

Component Intelligence Program List

DHS policy requires the Under Secretary for Intelligence and Analysis, in coordination with Intelligence Enterprise components, to identify and designate Component Intelligence Programs. The Under Secretary formally designates Component Intelligence Program in a list, which according to I&A officials, should be updated periodically. However, the list was last updated in 2016 and does not include Intelligence Enterprise components such as the Federal Protective Service, which established an intelligence division in 2023, or the Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction Office, which was created in 2018. I&A is to use the Intelligence Enterprise to coordinate and deconflict national and departmental intelligence. I&A officials told us that without an updated list of Component Intelligence Programs, the Intelligence Enterprise lacks the organizational structure to function as DHS or Congress intended.

In August 2024, the Under Secretary for Intelligence and Analysis issued a memorandum requesting that all components provide I&A with an updated list of their Component Intelligence Programs by September 30, 2024. As of June 2025, this effort remained incomplete. I&A officials said this was because they continued to negotiate details related to the effort with Intelligence Enterprise components. Project management standards state that organizations should estimate the duration of activities and create a schedule, such as milestones and time frames, to execute them.[38] Developing and documenting procedures with milestones and time frames for periodically updating the list of Component Intelligence Programs would help ensure that I&A has an accurate list of programs over which to carry out its strategic oversight requirements.

Conclusions

Effectively preventing and responding to threats to homeland security is a responsibility across all DHS components that have intelligence programs. I&A must execute its strategic oversight requirements for the DHS Intelligence Enterprise to help ensure that components are addressing threats through coordinated information and intelligence sharing. Accordingly, developing and implementing procedures with milestones and time frames for the required consolidated budget, intelligence priorities framework, and program review and associated annual report would help I&A perform these requirements annually. This would also help I&A ensure it continues to implement activities required by statute and policy, when it must also respond to changes in leadership priorities. Additionally, given that DHS policy and statutory responsibilities require I&A to coordinate and provide training to Intelligence Enterprise staff, developing a plan with milestones and time frames to finalize I&A’s training study and implement appropriate recommendations would help provide reasonable assurance that I&A training is suitable for the various DHS Intelligence Enterprise missions and accessible to staff.

I&A’s Intelligence Enterprise collaboration efforts have addressed most of the leading collaboration practices identified in our prior work, but additional actions are needed to address two of eight practices. For instance, I&A has not fully implemented its product coordination process for finished intelligence reports. Doing so could help I&A ensure that its product coordination is more robust and help it prevent the publication of inaccurate or incomplete information. Additionally, clarifying the definition of Component Intelligence Programs and developing procedures with milestones and time frames for updating the list of such programs could give I&A the assurance that Intelligence Enterprise officials have an accurate list of programs with which to coordinate.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following seven recommendations to DHS:

· The Secretary of Homeland Security should ensure the Under Secretary for Intelligence and Analysis develops and implements procedures with milestones and time frames for the annually required DHS Intelligence Enterprise consolidated budget. (Recommendation 1)

· The Secretary of Homeland Security should ensure the Under Secretary for Intelligence and Analysis develops and implements procedures with milestones and time frames for the annually required DHS Intelligence Enterprise intelligence priorities framework. (Recommendation 2)

· The Secretary of Homeland Security should ensure the Under Secretary for Intelligence and Analysis develops and implements procedures with milestones and time frames for the required program reviews of the DHS Intelligence Enterprise and associated annually required report. (Recommendation 3)

· The Secretary of Homeland Security should ensure the Under Secretary for Intelligence and Analysis develops and documents a plan with milestones and time frames to finalize its Intelligence Enterprise training study and implement any recommendations, as appropriate. (Recommendation 4)

· The Secretary of Homeland Security should ensure the Under Secretary for Intelligence and Analysis, in coordination with the heads of DHS Intelligence Enterprise components, fully implements the required product coordination list and process for finished intelligence products. (Recommendation 5)

· The Secretary of Homeland Security should ensure the Under Secretary for Intelligence and Analysis updates and clarifies the policy definition of a Component Intelligence Program. (Recommendation 6)

· The Secretary of Homeland Security should ensure the Under Secretary for Intelligence and Analysis develops and documents procedures with milestones and time frames for periodically updating the list of Component Intelligence Programs. (Recommendation 7)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this product to DHS for review and comment. DHS provided comments, which are reproduced in full in appendix III. In its comments, DHS agreed with our seven recommendations and described I&A’s planned actions to address them. However, for the fifth recommendation, DHS requested we close the recommendation as implemented based on action I&A had taken since receiving our draft report. We adjusted the recommendation to reflect I&A’s action, as discussed below. DHS also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

Regarding the fifth recommendation related to the coordination process for finished intelligence products, I&A provided the finalized product coordination list that it sent, via email, to components in June 2025, after we provided our draft to DHS for review and comment. In response, we adjusted our initial recommendation, which asked I&A to develop milestones and timeframes to finalize and implement guidance, given the delays in establishing the new process. The modified recommendation—that I&A, in coordination with the heads of DHS Intelligence Enterprise components, fully implements the required product coordination list and process for finished intelligence products—is focused on the implementation of the list and process. For example, I&A did not provide documentation of the components’ corresponding internal processes for product coordination, as outlined in its January 2024 effort. In addition, because the list was distributed to components in June 2025, it is too soon to determine whether I&A and enterprise components are routinely using the product coordination process as outlined.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees and the Secretary of Homeland Security. In addition, this report is available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov. If you or your staff have any questions, please contact me at shermant@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made significant contributions to this report are listed in appendix IV.

Tina Won Sherman

Director, Homeland Security and Justice

List of Requesters

The Honorable Gary C. Peters

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable Bennie G. Thompson

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security

House of Representatives

The Honorable Seth Magaziner

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Counterterrorism and Intelligence

Committee on Homeland Security

House of Representatives

This report addresses the following objectives:

1. To what extent is the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Office of Intelligence and Analysis (I&A) conducting its required strategic oversight of the DHS Intelligence Enterprise?

2. To what extent does DHS I&A’s required collaboration with the DHS Intelligence Enterprise address leading practices?

To address both objectives, we interviewed officials from several I&A headquarters offices. Specifically, we met with officials from the Intelligence Enterprise Program Office; Office of the Deputy Under Secretary for Analysis; Office of the Deputy Under Secretary for Collection; Field Intelligence Directorate; Engagement, Liaison, and Outreach Division; Workforce Management and Engagement Division; Financial Resources Management Division; Intelligence Training Academy; and Program Performance and Evaluation Division. In addition, we interviewed management officials from the remaining nine DHS Intelligence Enterprise components using a semi-structured questionnaire about I&A’s oversight activities and collaboration with the components.[39] At the time of our review, I&A had not formally updated the list of Intelligence Enterprise components since 2016, so we asked I&A to identify the current components, which we verified during our outreach and interviews with components.

To address our objective on strategic oversight requirements, we reviewed applicable statutes and DHS policies to determine I&A’s authorities, roles, and responsibilities for strategic oversight of the Intelligence Enterprise. These included, for example, DHS directives and instructions focused on the Intelligence Enterprise.[40] We identified primary strategic oversight requirements by considering which policy requirements corresponded with statutory requirements and which requirements necessitated annual updates from I&A, for example. To determine the extent to which I&A is executing the four primary Intelligence Enterprise strategic oversight requirements we identified in DHS policy—developing a consolidated budget, developing an intelligence priorities framework, conducting intelligence program reviews and reporting the results, and providing training—we reviewed documentation about I&A’s ongoing and planned actions to fulfill these requirements since June 2013, the date DHS issued its Intelligence Enterprise policy.[41] This included memoranda, plans, and reports. We also discussed ongoing and planned actions with I&A headquarters officials from the Intelligence Enterprise Program Office and the Intelligence Training Academy, among others.

We further assessed I&A’s efforts to develop and document procedures for its four primary strategic oversight requirements against select project management standards.[42] Those standards emphasize the need for activities to have a schedule, such as milestones and time frames, to execute them. In addition, we compared I&A’s consolidated budget, priorities framework, and program review and reporting efforts against the control activities component of Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, specifically the principle that management should implement control activities through policies and document such policies.[43]

To address our objective on collaboration, we reviewed documentation related to I&A’s collaboration with Intelligence Enterprise components, such as DHS policies, memoranda, charters for the Homeland Security Intelligence Council and its functional boards, and guidance documents.[44] We also discussed I&A’s Intelligence Enterprise collaboration activities and their benefits and challenges during our interviews with I&A headquarters officials and management officials from the nine DHS Intelligence Enterprise components. For example, we solicited officials’ feedback on the benefits and challenges of the Intelligence Enterprise’s finished intelligence product coordination processes.

To further address our objective on collaboration, we conducted discussion groups with a nongeneralizable sample of analysts at three of nine Intelligence Enterprise components to discuss I&A’s Intelligence Enterprise collaboration activities and their benefits and challenges using a semi-structured questionnaire. In selecting the three components, we prioritized the components with which I&A either co-produced or coordinated the most finished intelligence products from fiscal year 2022 through June 30, 2024. To make our selections, we used summary data on finished intelligence products for this time period, the most recent data available at the time of our selection.[45] In addition, we conducted similar discussion groups with analysts from the three of I&A’s four analytic centers that interacted most frequently with the components we selected. While the information we obtained from these interviews cannot be generalized to all Intelligence Enterprise component and I&A analysts, the discussions provided a range of valuable perspectives regarding I&A’s collaboration with the Intelligence Enterprise.

We compared I&A’s Intelligence Enterprise collaboration activities—identified through documentation and interviews with I&A headquarters officials and Intelligence Enterprise management officials and analysts—against eight leading collaboration practices identified in our prior work.[46] Each of these practices contains key considerations or questions of which we determined in our prior work to be relevant to collaboration.[47] For example, a key consideration of the “define common outcomes” leading practice is if agencies have identified crosscutting challenges or opportunities.

We determined if I&A actions either addressed or partially addressed the leading practice. Specifically, for those we rated as “addressed”, our assessment of documentation and interviews found that I&A had taken steps to address the key considerations consistent with the leading collaboration practice. For those we rated as “partially addressed”, our assessment of documentation and interviews found that I&A had taken steps to address some key considerations consistent with the leading practice but could take additional steps to address one or more of the key considerations. To determine the rating, a first analyst established an initial rating, and a second analyst reviewed supporting evidence and verified it. If there were discrepancies, both analysts discussed the evidence and assessment and made a final determination.

For the leading collaboration practices that I&A partially addressed, we further assessed I&A’s actions against select project management standards.[48] Those standards emphasize the need for plans to have a schedule, such as milestones and time frames, to execute them. Specifically, we assessed I&A’s efforts to develop and document procedures for its Intelligence Enterprise product coordination list and process and Component Intelligence Program policy and list update against those standards.

We conducted this performance audit from May 2024 through July 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Appendix II: DHS Actions to Collaborate with the DHS Intelligence Enterprise that Address Leading Practices

DHS policy requires that I&A oversee the DHS Intelligence Enterprise, which is the primary mechanism to integrate and manage DHS’s intelligence programs, projects, and activities.[49] I&A and the following DHS entities make up the DHS Intelligence Enterprise: the Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction Office, the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, Federal Protective Service (within the Management Directorate), the Transportation Security Administration, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, U.S. Coast Guard, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

As shown in Table 2, I&A has taken actions that addressed six of eight leading collaboration practices identified in our prior work and has partially addressed two of eight.[50] For additional information on how we analyzed I&A actions taken, see appendix I.

Table 2: Status of Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Office of Intelligence and Analysis (I&A) Actions to Collaborate with the DHS Intelligence Enterprise that Address Leading Practices

|

Leading practice and key considerations |

Status |

Summary of I&A actions takena |

|

Define common outcomes · Have the crosscutting challenges or opportunities been identified? · Have short- and long-term outcomes been clearly defined? · Have the outcomes been reassessed and updated, as needed? |

|

I&A has taken steps to define common outcomes by aligning its collaboration activities with its mission. The Under Secretary for Intelligence and Analysis issued a memorandum in May 2023 that identified challenges and opportunities to align I&A’s priorities with its mission. As a result of this assessment, I&A established the Intelligence Enterprise Program Office to support the Under Secretary for Intelligence and Analysis in exercising their strategic oversight authorities and responsibilities for the Intelligence Enterprise. To better enable collaboration between Intelligence Enterprise components, I&A revised how the Homeland Security Intelligence Council—which assists the Under Secretary for Intelligence and Analysis in performing strategic oversight of the enterprise—communicates desired outcomes for Intelligence Enterprise initiatives. For example, management officials from all nine Intelligence Enterprise components accurately described the purpose of the Homeland Security Intelligence Council. |

|

Ensure accountability · What are the ways to monitor, assess, and communicate progress toward the short- and long-term outcomes? · Have collaboration-related competencies or performance standards been established against which individual performance can be evaluated? · Have the means to recognize and reward accomplishments related to collaboration been established? |

|

I&A addressed the collaboration practice of ensuring accountability by establishing performance standards to evaluate collaboration. For example, I&A assesses individual analysts’ collaboration with their Intelligence Enterprise counterparts in their annual performance evaluations by measuring the extent to which they share information. Additionally, management officials from five of nine components told us that I&A incorporates their feedback regarding its management of the Homeland Security Intelligence Council. For instance, management officials from one component said they provide routine feedback to I&A, enabled by open lines of communication. |

|

Bridge organizational cultures · Have strategies to build trust among participants been developed? · Have participating agencies established compatible policies, procedures, and other means to operate across agency boundaries? · Have participating agencies agreed on common terminology and definitions? |

|

I&A has not taken needed steps to bridge organizational cultures. Although management officials from seven of nine components told us the actions of the Homeland Security Intelligence Council have built trust between components, we found that components have not agreed upon common definitions. Intelligence Enterprise components have inconsistently designated their Component Intelligence Programs because the policy that defines such programs includes two definitions. In addition, we found that the memo certifying the list of Component Intelligence Programs is outdated and does not account for recent internal realignments within the Intelligence Enterprise. The list was last updated in 2016 and does not include Intelligence Enterprise components such as the Federal Protective Service, which established an intelligence division in 2023, or the Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction Office, which was created in 2018. |

|

Identify and sustain leadership · Has a lead agency or individual been identified? · If leadership will be shared between one or more agencies, have roles and responsibilities been clearly identified and agreed upon? · How will leadership be sustained over the long term? |

|

I&A has taken steps to identify and sustain leadership by establishing the Intelligence Enterprise Program Office in 2023. The office is to support the Under Secretary for Intelligence and Analysis in performing their responsibilities for strategic oversight over the Intelligence Enterprise.b Furthermore, the Under Secretary created the office because I&A historically has not had the organizational structure to fully execute its Intelligence Enterprise coordination and strategic oversight responsibilities. Management officials from two Intelligence Enterprise components said they noticed benefits resulting from the establishment of the Intelligence Enterprise Program Office, such as improvements in how the Homeland Security Intelligence Council functions. |

|

Clarify Roles and Responsibilities · Have the roles and responsibilities of the participants been clarified? · Has a process for making decisions been agreed upon? |

|

I&A has taken steps to clarify roles and responsibilities for Intelligence Enterprise collaboration by documenting them in policy. For example, the Homeland Security Intelligence Council Charter established a process for decision-making in 2009. In November 2024, I&A issued a charter to clarify the roles and responsibilities of both the Council’s Coordinating Committee—a group that coordinates the various activities of the Council’s functional boards and working groups—and its six functional boards, which focus on specific topics. The charter lists the functions and responsibilities of the Coordinating Committee, such as overseeing functional board activities. It also lists the roles and responsibilities of each functional board, such as recommending Intelligence Enterprise improvements to the Homeland Security Intelligence Council. |

|

Include relevant participants · Have all relevant participants been included? · Do the participants have the appropriate knowledge, skills, and abilities to contribute? · Do participants represent diverse perspectives and expertise? |

|

I&A has taken steps to include staff with the appropriate knowledge, skills, and abilities in collaboration mechanisms. For example, I&A appointed a Senior Executive Service level position to lead the Intelligence Enterprise Program Office, which ensured the office included employees with leadership experience. In addition, the Homeland Security Intelligence Council is comprised of Key Intelligence Officials from all Intelligence Enterprise components. Part of the Intelligence Enterprise Program Office’s revitalization efforts for the Homeland Security Intelligence Council is ensuring these officials have a venue to elevate and address collaboration issues. For example, each Homeland Security Intelligence Council functional board is co-chaired by I&A and a representative from an Intelligence Enterprise component. |

|

Leverage resources and information · How will the collaboration be resourced through staffing? · How will the collaboration be resourced through funding? If interagency funding is needed, is it permitted? · Are methods, tools, or technologies to share relevant data and information being used? |

|

I&A has not taken needed steps to leverage resources and information. I&A has not fully implemented its process for Intelligence Enterprise components to review relevant information for accuracy when coordinating finished intelligence products throughout the enterprise.c Management officials at six of nine Intelligence Enterprise components described issues with the relationship-based product coordination process. For example, officials said I&A sent product coordination requests to the wrong points of contact at their respective component or did not send such requests at all. According to I&A analysts and analysts from two of three Intelligence Enterprise components we spoke with, a lack of coordination between analysts drafting intelligence products and components’ subject matter experts has led to the publication of errors in those products. In January 2024, I&A, working through the Homeland Security Intelligence Council’s Analysis and Production Board, initiated efforts to improve Intelligence Enterprise-wide product coordination for finished intelligence products. This effort included developing (1) a list of required coordinators and (2) a requirement that components develop corresponding internal processes for product coordination. Despite an initial deadline of January 2025, I&A did not complete this effort until June 2025, after we submitted this report to DHS for review and comment. As such, it is too soon to tell whether I&A is ensuring that components are implementing the coordination process outlined in the June 2025 document. |

|

Develop and update written guidance and agreements · If appropriate, have agreements regarding the collaboration been documented? · A written document can incorporate agreements reached for any or all of the practices. · Have ways to continually update or monitor written agreements been developed? |

|

I&A has taken steps to develop and update written guidance and agreements. I&A developed key guidance documents and agreement memoranda that address collaboration across the Intelligence Enterprise. For example, I&A issued several memoranda in September 2023 that charged the functional boards of the Homeland Security Intelligence Council to lead efforts to implement the various requirements discussed earlier in this report, such as the consolidated budget. Regarding specific collaboration activities, I&A has documented key decisions made at quarterly Homeland Security Intelligence Council meetings and attached memoranda that support those decisions. In addition, I&A has documented several memoranda of understanding with Intelligence Enterprise components to assign I&A liaison officers to temporary details at components’ intelligence offices. These liaison officers serve as senior I&A representatives at their host component and provide subject matter expertise. |

Legend:

![]() Addressed: I&A has taken steps to address the key considerations

consistent with the leading collaboration practice.

Addressed: I&A has taken steps to address the key considerations

consistent with the leading collaboration practice.

![]() Partially addressed: I&A has taken steps to address some key

considerations consistent with the leading collaboration practice but could

take additional steps to address one or more of the key considerations.

Partially addressed: I&A has taken steps to address some key

considerations consistent with the leading collaboration practice but could

take additional steps to address one or more of the key considerations.

Source: GAO analysis of DHS information; GAO icons. | GAO‑25‑107540.

aWe conducted various semi-structured interviews and discussion groups to assess I&A’s Intelligence Enterprise collaboration: (1) semi-structured interviews with Intelligence Enterprise management officials from nine Intelligence Enterprise components; (2) discussion groups with analysts from three Intelligence Enterprise components that co-produced or coordinated the most finished intelligence products with I&A; and (3) discussion groups with the three I&A analytic centers that interacted most frequently with the components we selected.

bSee 6. U.S.C. § 121(d)(16) (requiring the Under Secretary for Intelligence and Analysis to coordinate and enhance integration among the intelligence components of the Department, including through strategic oversight of the intelligence activities of such components).

cFinished intelligence products contain the assessment, judgment, or other analytic input of personnel, contain analytic conclusions, and are intended to be distributed outside of DHS.

GAO Contact

Tina Won Sherman, shermant@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgements

In addition to the contact named above, Mona Nichols Blake (Assistant Director), Natalie Swabb (Analyst-in-Charge), Lincoln Dow, Michele Fejfar, Schuyler Janzen, Mary Turgeon, and Sarah Veale made key contributions to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]6 U.S.C. § 121(d)(1). Further, I&A is statutorily responsible for disseminating, as appropriate, information analyzed by the Department to other DHS and federal agencies as well as to state and local governments and private sector entities with homeland security responsibilities in order to deter, prevent, preempt, or respond to terrorist attacks against the U.S. See 6 U.S.C. § 121(d)(6).

[2]Department of Homeland Security, DHS Intelligence Enterprise, Instruction 264-01-001 (Washington, D.C.: June 28, 2013). See also 6 U.S.C. § 121(d)(16) (requiring I&A to coordinate and enhance integration among the intelligence components of the Department, including through strategic oversight of the intelligence activities of such components).

[3]The DHS Intelligence Enterprise is composed of I&A and the intelligence components of the following DHS entities: the Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction Office, the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, Federal Protective Service (within the Management Directorate), the Transportation Security Administration, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, U.S. Coast Guard, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. We discuss issues with I&A’s processes for updating the list of Intelligence Enterprise components later in this report. See also 6 U.S.C. § 121(b)(2) (designating the Under Secretary for Intelligence and Analysis as the Chief Intelligence Officer of the Department).

[4]See Intelligence Community, Department of Homeland Security, and Department of Justice Inspector Generals, Review of Domestic Sharing of Counterterrorism Information, OIG-17-49 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 30, 2017).

[5]See DHS, Implementation Status of Public Recommendations: Supplement to Annual Budget Justification for Fiscal Year 2026, (Washington, D.C.: May 30, 2025).

[6]In June 2022, I&A began an examination of I&A’s mission and management practices (a “360 review”) initiated by the Under Secretary for Intelligence and Analysis and in September 2023, an examination with the DHS Counterterrorism Coordinator. These reports both identified opportunities for I&A to enhance its leadership of the DHS Intelligence Enterprise, among other things.

[7]See GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Removed the border around the images

Government, GAO‑14‑704G (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 2014); and Project Management Institute, Inc. A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide), Seventh Edition (Newtown Square, PA: 2021). PMBOK is a trademark of Project Management Institute, Inc.

[8]At the time of our review, I&A had not formally updated the list of Intelligence Enterprise components since 2016. To identify the components, we asked I&A to identify the current Intelligence Enterprise components, which we verified during our outreach and interviews with components.

[9]GAO, Government Performance Management: Leading Practices to Enhance Interagency Collaboration and Address Crosscutting Challenges, GAO‑23‑105520 (Washington, D.C., May 24, 2023).

[10]Project Management Institute, Inc. A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide), Seventh Edition (Newtown Square, PA: 2021).

[11]6 U.S.C. § 121(b)(2); Department of Homeland Security, Delegation to the Under Secretary for Intelligence and Analysis/Chief Intelligence Officer, Delegation 08503 (Washington, D.C.: Aug. 10, 2012).

[12]See DHS Instruction 264-01-001; 6 U.S.C § 121(d)(16) (“The responsibilities of the Secretary relating to intelligence and analysis shall be as follows: …To coordinate and enhance integration among the intelligence components of the Department, including through strategic oversight of the intelligence activities of such components.”). The activities and responsibilities we discuss in this report align with the Under Secretary’s dual role as the DHS Chief Intelligence Officer. However, in this report, we use the title Under Secretary for Intelligence and Analysis.

[13]See DHS Instruction 264-01-001.

[14]50 U.S.C. § 3003(4)(K) (designating the DHS I&A as a member of the Intelligence Community); Department of Homeland Security, Intelligence Integration and Management, Directive 264-01 (Washington, D.C.: June 12, 2013). The U.S. Intelligence Community is composed of 18 members: two independent agencies (the Office of the Director of National Intelligence and the Central Intelligence Agency); nine members within the Department of Defense; and seven members from other departments and agencies, including DHS. See generally 50 U.S.C. § 3003(4). While a member of the DHS Intelligence Enterprise, the U.S. Coast Guard is also an independent member of the Intelligence Community.

[15]Intelligence entities generally produce and disseminate two types of products: (1) raw intelligence reports and (2) finished intelligence products. Raw intelligence is unanalyzed content whereas finished intelligence products contain the assessment, judgment, or other analytic input of personnel, contain analytic conclusions, and are intended to be distributed outside of DHS.

[16]6 U.S.C. § 124e; see also 6 U.S.C. § 121(d)(13) (requiring I&A to coordinate training and other support to the elements and personnel of the Department, among others, to facilitate the identification and sharing of information revealed in their ordinary duties and the optimal utilization of information received from the Department).

[17]See DHS Instruction 264-01-001.