OTHER TRANSACTION AGREEMENTS

Improved Contracting Data Would Help DOD Assess Effectiveness

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional committees

For more information, contact: Mona Sehgal at Sehgalm@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

The Department of Defense (DOD) can use a contracting mechanism known as an “other transaction agreement,” or OTA, to develop prototypes. Rather than using standardized federal acquisition terms and conditions, OTAs rely on DOD contracting officials to customize the terms and conditions they deem necessary to protect the government’s interests. This flexibility may help DOD attract nontraditional defense contractors that otherwise may not choose to contract with DOD. However, this flexibility could also increase risk, such as by reducing oversight of contractors’ costs.

After DOD successfully develops a prototype, it may produce it on a larger scale by awarding either (1) another OTA—known as a production OTA, or (2) a standard contract, which is subject to the Federal Acquisition Regulation.

In fiscal year 2024, DOD’s prototype OTA obligations totaled over $16 billion. However, DOD does not know the extent to which these prototype OTAs directly resulted in production awards. DOD systematically tracks production OTAs, reporting $2 billion in production OTA use in fiscal year 2024. However, DOD does not similarly track standard contracts for production that resulted from prototype OTAs. Without a systematic process to track these data, DOD cannot assess the extent to which OTAs are delivering capabilities to the warfighter.

Ten of GAO’s 18 selected weapon systems that used prototype OTAs planned to switch to standard contracts for production. DOD officials said that while they saw benefits of OTA flexibilities during the prototyping phase, such as collaboratively working with contractors on the statements of work, they used standard contracts during the production phase to help mitigate risks. For example, officials said that standard contracts can help increase DOD’s insight into contractor costs and reduce the risk of overpayment.

Moreover, DOD officials told GAO that like any procurement approach, OTAs offer different advantages and disadvantages, and do not ensure successful outcomes. DOD officials added that a well-written OTA cannot compensate for a poorly planned acquisition. DOD officials stated they are collecting lessons learned associated with transitioning prototype OTAs into production.

Why GAO Did This Study

DOD obligations through OTAs for prototyping and production have significantly increased, growing from $1.8 billion in fiscal year 2016 to over $18 billion in fiscal year 2024. The current administration has also encouraged the use of OTAs, particularly for defense acquisitions. Prior GAO and DOD Inspector General reports found that data challenges limited DOD’s visibility into the use of OTAs, including the extent to which nontraditional defense contractors were participating.

A Conference report includes a provision for GAO to review DOD’s use of OTAs. GAO’s report examines (1) the extent to which DOD used prototype OTAs and the data it collects to determine their effectiveness, and (2) how selected DOD weapon system development efforts using prototype OTAs planned to transition into production.

To do this work, GAO analyzed OTA data from fiscal years 2021 through 2024 and compared these data against DOD’s reports to Congress. GAO reviewed a nongeneralizable sample of 18 weapon systems using prototype OTAs. GAO selected the sample from two DOD components that accounted for a majority of OTA use, based on GAO’s annual assessments of DOD’s major weapon systems. GAO also interviewed contracting officials from DOD components.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making two recommendations, including that DOD should develop and implement a systematic process to track standard contracts for production that resulted from prototype OTAs. DOD agreed with both recommendations.

Abbreviations

DOD Department of Defense

FAR Federal Acquisition Regulation

FPDS Federal Procurement Data System

NDC nontraditional defense contractor

OTA other transaction agreement

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

September 3, 2025

Congressional Committees

The Department of Defense (DOD) has the authority to use other transaction agreements (OTA), a flexible contracting mechanism not subject to the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) System. DOD may use an OTA to attract nontraditional defense contractors (NDC) that might not otherwise choose to contract with DOD under traditional FAR-based contracts. We previously found that NDCs identified the complexity and cost of complying with government-unique terms and conditions as one of multiple barriers to working with the government.[1] OTAs allow contracting officials to use their professional judgment to tailor the terms and conditions deemed appropriate and relevant for a particular project to protect the government’s interests. Prior GAO and DOD Inspector General reports found that data challenges limited DOD’s visibility into the use of OTAs. We also found that these challenges limited visibility into the extent to which NDCs were participating.[2]

DOD obligations through OTAs for prototype development and production have significantly increased, growing from $1.8 billion in fiscal year 2016 to nearly $17 billion in fiscal year 2021 after adjusting for inflation. Most of DOD’s OTA obligations were through prototype OTAs—a type of OTA generally used to prototype technologies or products and test their suitability for military use. Successful prototypes may be transitioned into fielding or production to mass-produce the technologies or products. If a prototype meets certain criteria, as provided in the prototype OTA, DOD can noncompetitively make a follow-on production award either through (1) a production OTA, or (2) a standard contract, which is subject to the FAR.[3]

The current administration has also encouraged the use of OTAs. In March 2025, the Secretary of Defense issued a memorandum directing DOD components to use OTAs as the default procurement approach for software acquisition pathway efforts.[4] In April 2025, the President signed an executive order directing preferential use of OTAs for DOD acquisitions, among other things.[5]

Conference Report 118-301 accompanying the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024 includes a provision for GAO to review DOD’s use of OTAs.[6] This report examines (1) the extent to which DOD used prototype and production OTAs and data it collects to determine the effectiveness of OTAs, and (2) how selected DOD weapon system efforts using prototype OTAs planned to deliver capabilities using OTAs or FAR contracts.[7]

To assess the extent to which DOD used prototype and production OTAs, we analyzed Federal Procurement Data System (FPDS) data from fiscal years 2021 through 2024. This time frame covers data available after fiscal year 2020, a year significantly influenced by federal spending supporting the COVID-19 response. We then compared these data against DOD’s most recent annual reports to Congress, which are generated through a department-wide manual data request. To assess the data DOD collects to assess the effectiveness of OTAs, we analyzed available FPDS data on production contracts awarded using DOD’s follow-on production authority, consortia-based OTAs, and NDC participation from fiscal years 2021 through 2024. We compared these data against DOD’s annual report to Congress for fiscal year 2023, and additional data sources such as contracting documentation for individual weapon system efforts. We also interviewed contracting headquarters officials from the military services and other relevant DOD components, including agreements officers—officials specially trained and warranted to award OTAs. We found the data to be sufficiently reliable for discussing DOD’s use of OTAs during this time.

To examine how selected DOD weapon systems using prototype OTAs planned to deliver capabilities, we selected a nongeneralizable sample of 18 weapon systems by analyzing our annual assessments of DOD’s major weapon systems from fiscal years 2017 through 2024. We selected this time range to align with DOD’s increase in OTA obligations.

We established selection criteria for weapon portfolios—groups of efforts with a particular focus, such as aviation or ground vehicles—that had more than three efforts using OTAs. Three portfolios met our criteria: Army air and missile defense (eight efforts), Army long range fires (four efforts), and Space Force/Space Development Agency space systems (six efforts). We analyzed documentation such as acquisition strategies, status briefings, and awarded contracts or OTAs to identify how these 18 selected efforts planned to transition their prototyping efforts into capability delivery. We also collected data for four selected consortia-based OTAs that aligned with the three portfolios mentioned above, including the extent to which NDCs participate in these consortia. We interviewed acquisition and contracting officials from each selected effort.

For additional information on our objectives, scope, and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from April 2024 to September 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Overview of DOD’s OTA Authority

Congress authorized DOD to use OTAs in the late 1980s and has expanded the authority over several decades. Congress first provided the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency—the agency responsible for DOD’s breakthrough technologies for national security—with the authority to temporarily use OTAs for research projects in 1989.[8] Since then, Congress made OTA authority permanent, extended it to the entire DOD, and expanded its scope to include prototyping and production efforts.[9]

OTAs enable agencies and awardees to start with a “blank sheet of paper” to negotiate terms and conditions since they are not governed by the FAR. This flexibility may help address concerns from NDCs—entities that do not typically do business with the federal government. We previously reported that concerns related to intellectual property rights, the length of time it can take DOD to award a contract, and the need to establish a government-unique cost accounting system make DOD an unattractive customer for some NDCs.[10] Our prior work found that OTAs with NDCs have been used for research, prototyping, and production of new technologies or products.[11] We found that these agreements can be more flexible because they are exempt from the FAR and related oversight mechanisms. We also found, however, that the use of OTAs carries the risk of reduced accountability and transparency.[12]

DOD generally has department-wide authority to award OTAs for multiple purposes:

· Research OTA. DOD can use this type of OTA to carry out basic, applied, or advanced research.[13] According to DOD’s July 2023 Other Transactions Guide, research OTAs are intended to spur dual-use research and development that would benefit both commercial companies and the government, leveraging economies of scale without burdening companies with government regulations.[14] For the purposes of this report, we excluded research OTAs.

· Prototype OTA. DOD can use this type of OTA to carry out prototype projects, including those that are directly relevant to enhancing the mission effectiveness of military personnel and the supporting platforms, systems, components, or materials that DOD proposes to acquire or develop.[15] Under 10 U.S.C. § 4022(e), a prototype project includes a proof of concept, model, or a novel application of commercial technologies for defense purposes, among other things.

DOD may not use an OTA for a prototype project unless at least one of four statutory conditions is met: (1) participation by at least one nontraditional defense contractor or nonprofit research institution; (2) all significant participants are small businesses or NDCs; (3) specified cost sharing between government and industry; or (4) senior procurement executive approval based on exceptional circumstances.[16]

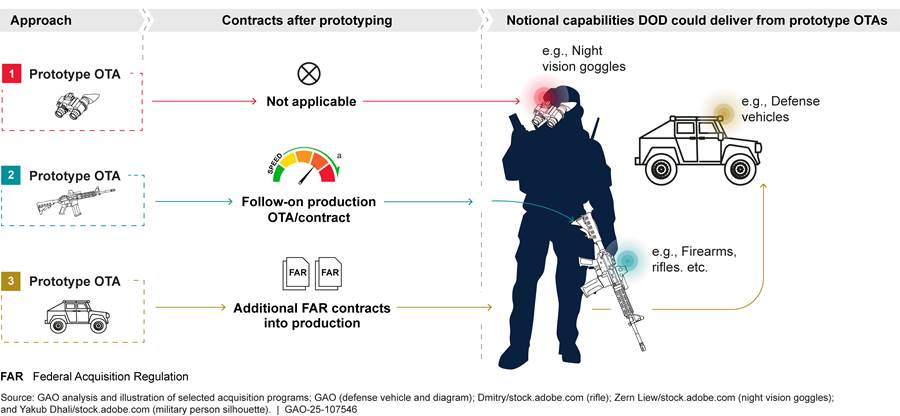

Upon successful completion of a prototype OTA, DOD may award follow-on production work noncompetitively to the participants of a competitively awarded prototype OTA.[17] DOD can award follow-on production work using another OTA, or a FAR contract (see figure 1). For the purposes of this report, we define “production OTAs” as agreements awarded using this follow-on production authority.

Figure 1: Notional Depiction of the Transition from Prototype Other Transaction Agreements (OTA) into Production Using Follow-On Production Authority

Consortia-based OTAs

DOD can award OTAs directly to an organization, such as an NDC, traditional defense contractor, or a university. Alternatively, DOD can award OTAs through a consortium—a group of members organized around one or more specific technology areas, which provides the government with a ready pool of stakeholders to innovate in that technology area. Consortium members can include traditional defense contractors, NDCs, academic institutions, and nonprofit organizations. Consortia are generally managed by consortium management organizations—typically nonprofit entities that can provide acquisition support and administrative services to the government, such as performing market research, releasing requests for proposals to consortium members on behalf of the government, and recruiting new consortium members. The government pays the organizations for such services.

DOD Weapon System Acquisition and Development

In January 2020, DOD established the Adaptive Acquisition Framework.[18] The framework emphasizes several principles, including simplifying acquisition policy, tailoring acquisition approaches, and conducting data-driven analysis. The Adaptive Acquisition Framework defines six acquisition pathways that have distinct processes for reviews, cost and schedule goals, and documentation. Weapon system efforts can follow one or more pathways during development, including the three pathways described below.

· Major capability acquisition pathway. This pathway leads complex acquisitions through phases such as technology development, system development, and production. DOD separates these phases by major reviews known as milestone decisions.[19] DOD can conduct prototyping during the technology development phase to reduce technical risk and validate technology designs, among other things. DOD can use a variety of contracting instruments for prototyping, such as FAR contracts or prototype OTAs.

· Software acquisition pathway. This pathway is intended to facilitate rapid and iterative delivery of software capability, including software-intensive systems, to users.[20]

· Middle tier of acquisition. This pathway includes two expedited approaches.[21] The first approach, rapid prototyping, is intended to quickly develop and demonstrate a capability in an operational environment within 5 years. Rapid prototyping also results in a product that a military department can field to the warfighter as an interim capability solution. The second approach, rapid fielding, is intended to begin production of a new or upgraded capability within 6 months, and complete fielding of that capability within 5 years.[22]

These acquisition pathways are separate from the contracting approach (OTA, FAR contract, etc.). Except for the Secretary of Defense’s March 6, 2025 memorandum directing to use OTAs for the software pathway, contracting officers may choose the procurement approach they believe most appropriate for the acquisition. For example, the major capability acquisition is designed for more complex weapon systems and generally contains more structured development and review processes. In contrast, the middle tier of acquisition rapid fielding pathway is designed for acquisitions with relatively mature technologies that require less rigorous development, and typically has fewer required reviews and less process. As such, DOD could use an OTA or FAR contract for any of these acquisition pathways if the relevant conditions are met.

DOD Increased Use of OTAs but Data Challenges Limit Insight into Effectiveness

DOD’s OTA obligations increased from nearly $17 billion in fiscal year 2021 to over $18 billion in fiscal year 2024 after adjusting for inflation, with overall increases in obligations for both prototype and production OTAs. While OTA use continues to grow, DOD lacks full information about the outcomes of OTA use. For example, DOD cannot systematically track the extent to which it transitioned prototype projects using OTAs into production efforts. DOD also lacks aggregated data on the extent of NDC participation on OTAs.

DOD Primarily Uses Prototype OTAs, but Production OTA Use Is Increasing

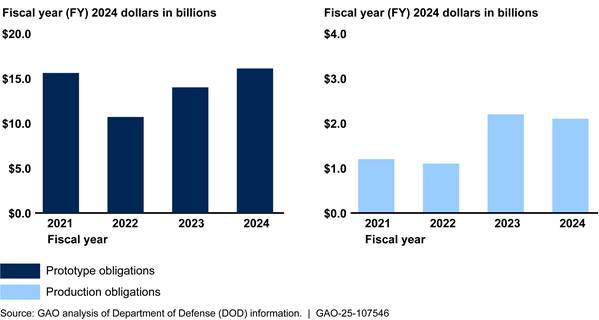

From fiscal year 2021 to 2024, DOD obligations on prototype and production OTAs increased from nearly $17 billion to over $18 billion. Collectively, prototype OTAs accounted for $56.3 billion of the $62.9 billion—or 90 percent of the total amount—DOD obligated on OTAs over this 4-year period. See figure 2 for total OTA obligations by OTA type and by fiscal year.

Figure 2: Department of Defense’s Obligations by Other Transaction Agreement Type, Fiscal Years 2021-2024

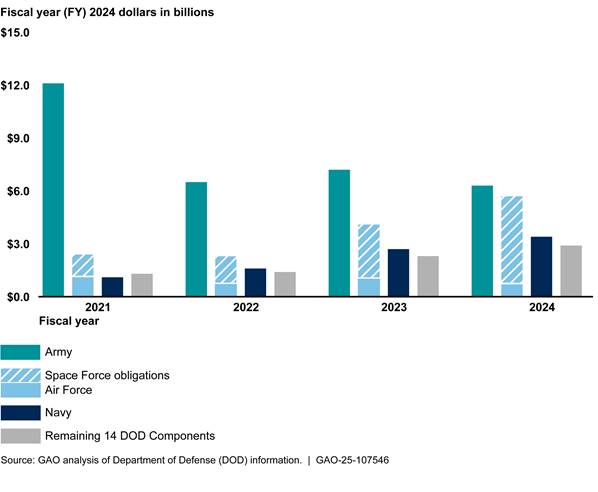

DOD components generally increased their use of OTAs between fiscal years 2021 and 2024. The Army, which has been the largest user of OTAs, experienced a decrease from 2021. It should be noted that the Army’s OTA obligations peaked in fiscal year 2021, which included $3.4 billion in obligations to develop a vaccine in support of the federal COVID-19 response. See figure 3 for prototype and production OTA obligations by DOD component and fiscal year.

Figure 3: Department of Defense Components’ Other Transaction Agreement Obligations, Fiscal Years 2021-2024

Note: In fiscal year 2021, the Army obligated $3.4 billion for other transaction agreements in support of the COVID-19 pandemic response.

From fiscal years 2021 through 2024, 10 vendors accounted for the majority of DOD’s OTA obligations. Specifically, these vendors received $35.9 billion of the $62.9 billion in OTA obligations, or about 57 percent. Four of these vendors are consortium management organizations, four are traditional defense contractors, and the remaining two are NDCs, including a pharmaceutical NDC that helped support the federal COVID-19 response (see table 1).

Table 1: Top 10 Vendors with Highest Overall Department of Defense Other Transaction Agreement (OTA) Obligations, Fiscal Years 2021-2024

Dollars in billions

|

Vendor name |

Vendor type |

Obligations |

|

Advanced Technology International |

Consortium management organizationa |

$15.5 |

|

National Security Technology Accelerator |

Consortium management organization |

$5.2 |

|

Lockheed Martin |

Traditional |

$3.1 |

|

Northrop Grumman |

Traditional |

$2.7 |

|

Consortium Management Group |

Consortium management organization |

$2.3 |

|

Microsoft |

Nontraditional defense contractor |

$1.7 |

|

AstraZeneca |

Nontraditional defense contractor |

$1.5 |

|

System of Systems Consortium |

Consortium management organization |

$1.5 |

|

L3Harris |

Traditional |

$1.3 |

|

Raytheon |

Traditional |

$1.1 |

|

All remaining vendors |

Various |

$27.0 |

Source: GAO analysis of Federal Procurement Data System data. | GAO‑25‑107546

aThis analysis only includes obligations for data where the consortium management organization is listed as the vendor in FPDS. There may be additional entries in FPDS in cases where another entity such as an individual consortium is listed as the vendor rather than the management organization, and those obligations are not reflected in this table

As we reported in November 2019, obligations for consortium management organizations reflect all obligations to members of individual consortia that they manage.[23] For example, Advanced Technology International did not receive the $15.5 billion in obligations, but rather distributed most of this amount to projects and members across the various consortia that it manages.[24]

Consortia-based OTAs account for half of DOD’s prototype OTA obligations from fiscal years 2021 to 2024. See table 2 for DOD’s OTA obligations by consortium status and OTA type from fiscal years 2021 through 2024.

Table 2: Department of Defense’s Obligations by Consortium Status and Other Transaction Agreement (OTA) Type, Fiscal Years 2021-2024

|

Fiscal year |

Consortia prototype |

Non-consortia prototype |

Consortia production |

Non-consortia production |

|

2021 |

$8.1 billion |

$7.5 billion |

$24 million |

$1.2 billion |

|

2022 |

$6.0 billion |

$4.7 billion |

$23 million |

$1.1 billion |

|

2023 |

$7.1 billion |

$6.9 billion |

$190 million |

$2.0 billion |

|

2024 |

$7.0 billion |

$9.1 billion |

$450 million |

$1.6 billion |

Source: GAO analysis of Federal Procurement Data System data. | GAO‑25‑107546

Additionally, nearly all consortia-based OTA obligations were through prototype OTAs rather than production OTAs. According to DOD officials, production OTAs are typically awarded directly to vendors that successfully complete prototypes. As we reported in September 2022, because the government has already identified the vendor with the successful prototype, the government can award the production OTA directly to the vendor rather than continuing to use the consortium.[25]

As we stated above, DOD increased its use of production OTAs from fiscal years 2021 through 2024. During this time, the 50 production OTAs with the highest obligations accounted for about $5.3 billion—or 84 percent—of DOD’s overall production OTA obligations. DOD used some of these high-dollar production OTAs to acquire software, information technology systems, and weapon systems that were commercially available items modified for military use.

Some illustrative examples of these high-dollar production OTAs are noted below.

· Integrated Visual Augmentation System: This is a commercial augmented-reality headset that Microsoft modified for Army use. The headset includes a display, sensors, on-body computer, and other elements intended to improve situational awareness, decision-making, and target acquisition for soldiers wearing the headset. The Army originally awarded Microsoft a 10-year production OTA valued up to $21.9 billion, but the Army later reduced the scale of the program and overall award value. As we reported in June 2023, the program faced technical issues with both hardware and software that led to delays.[26] Currently, the Army plans to recompete and award at least one OTA by the end of fiscal year 2025 for the design and prototype for a new version of the headset. The Army has obligated about $1.4 billion on the effort as of April 2025.

· National Background Investigation Services: This is an information technology system intended to support background investigations for most federal agencies and over 13,000 organizations that work with the government. DOD awarded a prototype OTA to develop this system in 2018. The Defense Counterintelligence and Security Agency originally planned for full deployment of the system in 2019, but the system encountered several delays. We previously reported that the Defense Counterintelligence and Security Agency had not established a reliable schedule and cost estimate for the program.[27] The agency awarded a production OTA in 2021 and has obligated $324 million as of April 2025.

· Direct View Optic: The Army awarded a production OTA in September 2020 to procure a commercial optic from Sig Sauer to be installed on an M4 rifle and its variants for use by soldiers. The Army obligated $49.4 million as of April 2025.

DOD Lacks Full Visibility into OTAs That Transition to Production Contracts

DOD does not have full visibility into the extent to which its prototype OTAs have successfully transitioned into production, and if so, whether it used production OTAs or FAR-based production contracts.[28] DOD systematically tracks data on production OTAs in FPDS, a web-based tool for federal agencies to report contract and OTA actions. DOD can identify production OTAs, the vendors awarded production OTAs, and associated obligations.[29] However, it lacks a reliable method for tracking FAR production contracts that used follow-on production authority when transitioned from prototype OTAs. According to DOD officials, they internally discussed potential changes to FPDS, but did not pursue the changes due to it not being a priority.

In the absence of a systematic approach to track such data, DOD manually collects data on follow-on FAR production contracts as part of its annual report to Congress. Since 2019, in response to Section 873 of the John S. McCain National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019, DOD has submitted annual reports to Congress on its use of prototype OTAs. DOD also included data on production OTAs and FAR production contracts in this report starting in fiscal year 2022. To support this effort, DOD’s Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment sends an annual data request to all DOD components that, in turn, task agreements officers with manually collecting and reporting the data.

We found that DOD’s reporting of FAR production contracts in its annual report to Congress for fiscal year 2023 was unreliable and inaccurate. Specifically, our analysis of DOD’s manual reporting identified 48 FAR production contracts that transitioned from prototype OTAs using follow-on production authority. However, only seven of these 48 contracts (15 percent) were actually FAR production contracts. The majority of these 48 contracts were instead prototype and production OTAs.

We shared this finding with DOD officials in November 2024. These officials stated that they inadvertently omitted a data field from the fiscal year 2023 data request, which may have caused some mistakes during the data entry process. We confirmed that DOD added this missing field back into the fiscal year 2024 data request. Additionally, DOD provided additional guidance to agreements officers regarding how to report information as part of the annual data request. It is too early to determine whether DOD’s actions will result in more reliable and accurate FAR production contract data in the future. As of April 2025, DOD was in the process of compiling the fiscal year 2024 annual report to Congress.

Section 873 of the John S. McCain National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019 requires DOD to collect, analyze, and report data on the use OTAs. Additionally, the Joint Explanatory Statement accompanying the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023 requires DOD to report on lessons learned and the success of follow-on production OTAs as compared to FAR production contracts. Without a systematic process to track data on follow-on FAR production contracts, DOD cannot assess the extent to which OTAs have resulted in capabilities fielded to the warfighter.

DOD Lacks Full Visibility into Consortia OTA Awardees

Despite recent data collection efforts, DOD still cannot fully identify which consortia members are performing the work awarded under consortia-based OTAs. In July 2021, we found that for consortia-based OTAs, the consortium management organization, rather than the awardees performing the work, is reflected in the FPDS data.[30] We noted that without information on the awardees, decision-makers have limited insight into the extent to which DOD is attracting NDCs—one of DOD’s goals for awarding OTAs. We recommended that DOD develop and implement a systematic approach to track consortium members performing on OTAs awarded through consortia. DOD concurred with this recommendation.

In response to our recommendation, the General Services Administration added new data fields to FPDS in June 2022 to identify awardees performing on consortia-based OTAs, among other things. For example, these new fields allow users to identify the specific members performing on and the amount obligated for projects awarded through consortia. To identify the extent to which these fields were completed, we reviewed data records from fiscal years 2023 and 2024 related to known consortium management organizations.[31] DOD accurately identified and completed 2,036 of 2,431 of the applicable records (84 percent). These records correctly identified the consortia members actually performing the work on consortia-based projects. The remaining 395 records inaccurately list the consortium management organization as the vendor performing work.[32]

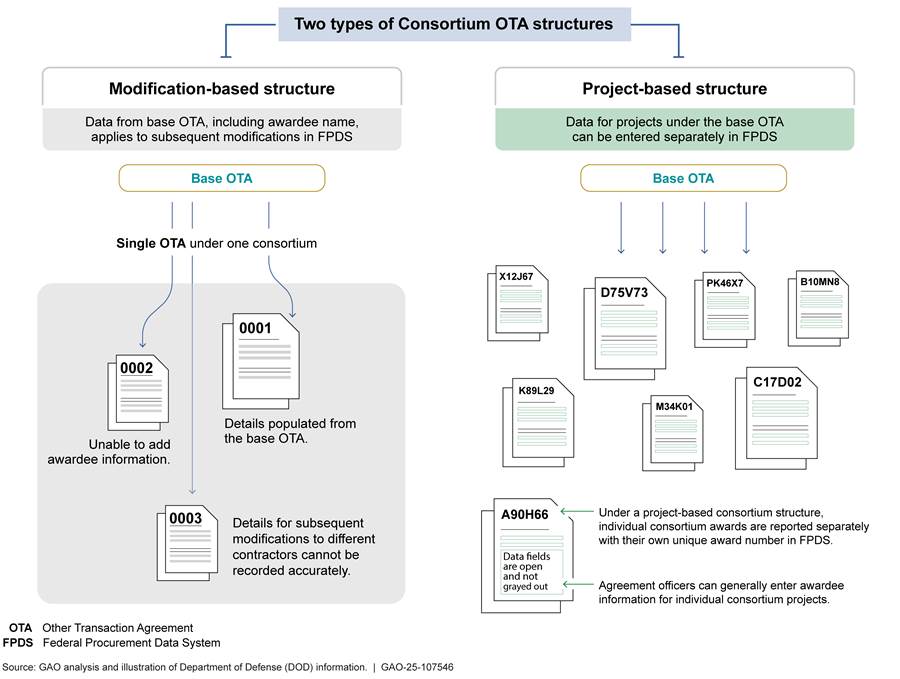

DOD’s approach to structuring consortia-based OTAs contributes to the challenges associated with determining who is performing the work. DOD can structure consortia-based OTAs in one of two approaches: (1) a modification-based structure in which there is recorded a single data row in FPDS for the consortium and all subsequent project awards are made via modifications to this base OTA, or (2) a project-based structure in which individual awards are recorded separately with their own unique award numbers in FPDS.[33] According to Army officials, DOD can also use both types of consortium structures under a single consortia-based OTA. For more information on the two types of consortium structures, see figure 4.

For modification-based structures, the FPDS data entry structure prevents DOD from completing information such as awardee names when the base OTA is modified. According to DOD officials, this is because FPDS automatically populates data from the initial award into all subsequent modifications to that award. As a result, when an agreements officer modifies an OTA to make a new award, they are unable to add information such as the names of the specific consortium participants performing on projects. DOD officials stated that agreement officers can add this information for project-based structures because new projects show up as separate, individual OTAs in FPDS. Therefore, agreements officers either cannot complete the consortium fields for modification-based OTAs or accurately identify the awardees. Despite the data visibility limitation of the modification-based structure, it offers other benefits such as allowing FPDS users to more easily track obligations by consortium compared to the project-based structure.

Agreement officers can maintain information on consortia-based OTAs than is maintained in FPDS, such as the names of consortium participants performing work on consortium awards and the obligations they received. Therefore, agreements officers could manually collect and report information for consortia, including modification-based OTAs, to supplement the incomplete consortium fields in FPDS. For example, we found one instance of a modification-based OTA with the consortium fields incomplete in FPDS, but the agreement officers responsible for it manually reported the missing information as part of the annual report to Congress for fiscal year 2023.

Section 873 of the John S. McCain National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019 requires DOD to collect and analyze OTA data. DOD’s July 2023 Other Transactions Guide explains that the objective of using consortia is to promote collaboration with capable partners, including NDCs. Although modification-based OTAs can offer some benefits, this OTA structure does not allow identification of awardees in FPDS. Nevertheless, DOD has detailed information available on consortium OTAs, including awardee names, in contracting officials’ records. Without fully and accurately reporting data on the awardees of consortia-based OTAs, DOD cannot provide congressional decision-makers with a complete picture of the awardees performing on consortium projects and the extent to which DOD is attracting NDCs—one of DOD’s goals for awarding OTAs.

Lack of Department-wide Data Limits DOD’s Analysis of Nontraditional Defense Contractor Engagement

DOD’s ability to analyze NDC engagement is limited by the lack of department-wide data. Specifically, DOD lacks aggregated data on whether OTA awardees are NDCs, the obligations they have received, and their contributions to the OTA projects. DOD lacks these data because it does not have a systematic approach to collect these types of data either in FPDS or another data system.

DOD systematically collects only one data point related to NDC engagement, which is a data field in FPDS that indicates whether there is “a significant extent” of NDC participation on an OTA. This field can therefore indicate whether there is at least one NDC performing on an OTA but does not explain whether it is the prime contractor or subcontractor, or if there are multiple NDCs contributing to a project. For example, our analysis of FPDS data for fiscal years 2021 through 2024 found that about 94 percent of DOD’s total OTA obligations went to OTAs that cited “a significant extent” of NDC participation.[34] However, DOD does not know how much of the $59 billion that it obligated on OTAs with at least one NDC participating to a significant extent went to NDCs as prime contractors or subcontractors. According to DOD’s July 2023 Other Transactions Guide, “significant extent” can mean that one or more NDCs will supply a new key technology or accomplish a significant amount of the project, among other things.

Despite the lack of aggregated data on NDCs, there are two main sources of information on NDC participation.

· Agreement officers. According to Space Force officials, agreement officers document the names of the NDCs performing on OTAs for which they are responsible. They also generally document how NDCs contribute to a particular project to meet the statutory condition of significant NDC participation. Collecting this information as standardized data would be difficult because it is subjective and can vary from project to project. For example, significant NDC participation could mean that a vendor is supplying a key technology or performing a significant portion of the work.

· Consortium management organizations. According to representatives from consortium management organizations, these organizations generally collect data on NDCs for consortia-based OTAs. Specifically, these organizations can collect information on their members such as vendor status (traditional, NDCs, or nonprofit), their participation on individual consortium projects (prime contractor or subcontractor), and the obligations they have received on consortia-based OTAs. Consortium management organizations can share this information with the agreements officers responsible for a given consortium. For example, some consortium agreements require quarterly and final reports to the government.

Our analysis of NDC data from four selected consortia found that NDCs comprised the majority of the members of those consortia (see table 3).

Table 3: Overview of Nontraditional Defense Contractor Participation among Selected Consortia, Fiscal Years 2021-2024

|

Consortium |

Number of nontraditional defense contractor members in consortium |

|

Aviation and Missile Technology Consortium |

1,048 of 1,262 (83%) |

|

Department of Defense Ordnance Technology Consortium |

890 of 1,058 (84%) |

|

Information Warfare Research Project |

650 of 810 (80%) |

|

Space Enterprise Consortium |

534 of 629 (85%) |

Source: GAO analysis of selected consortia data. | GAO‑25‑107546

Note: GAO obtained these data from Advance Technology International and National Security Technology Accelerator, the consortium management organizations responsible for these consortia.

The selected consortia awarded OTAs to NDC prime contractors in about 50 to 60 percent of projects awarded from fiscal years 2021 through 2023, but NDCs participated to a significant extent on nearly all of their awarded OTAs, according to consortium management data.

Section 888 of the Servicemember Quality of Life Improvement and National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2025 directed DOD to establish a process by December 2025 to track the number and value of awards made to NDCs and small businesses performing on OTAs, including those executed through consortia. We will continue to monitor how DOD responds to this requirement, to include what process, if any, DOD establishes to track data on NDC participation.

Most Selected Weapon Systems Prototype Development Efforts Using OTAs Eventually Transitioned to Production Contracts

While DOD is authorized to use production OTAs under certain circumstances, DOD officials elected to use FAR-based contracts to support production for the majority of the 18 weapons development efforts we selected. DOD officials cited multiple factors for choosing FAR contracts, including generally increased protections, insight into contractor costs, and workforce availability and experience. Additionally, DOD officials for some efforts reported benefits of using OTAs during the prototyping phase, including a shortened time to award by following streamlined procedures, among other things.

Selected Programs Generally Used OTAs for Prototyping and Contracts for Production

We analyzed 18 selected DOD efforts that used prototype OTAs and identified three primary approaches that they took or planned to take to deliver capability:[35]

· Prototype OTA only – DOD plans to deliver capability exclusively through prototype OTAs without transitioning further into production.

· Prototype OTA to production using follow-on production authority[36] – As noted earlier, under this authority, upon successful completion of a prototype OTA that was competitively awarded, DOD can award follow-on production work noncompetitively to successful participants, either through another OTA or a FAR contract.

· Prototype OTA to production without using follow-on production authority – DOD plans to award one or more FAR contracts to further develop and test the prototype before awarding a FAR production contract.[37]

Most selected efforts followed the third approach, meaning that they transitioned from an OTA to a FAR contract environment, or plan to do so in the future (see figure 5).[38]

Figure 5: Notional Depiction of How DOD Can Transition from Prototype Other Transaction Agreement (OTA) to Capability Delivery

aDOD can award follow-on production OTAs or contracts non-competitively provided certain statutory conditions are met. See 10 U.S. Code § 4022(f). According to DOD officials, non-competitive awards could potentially result in time savings.

Prototype OTA Only

Two of 18 selected efforts plan to deliver capability through prototype OTAs exclusively. Efforts following this approach plan to use spiral development—incremental development of new capabilities in cycles. Both efforts using this approach are Space Development Agency efforts. The satellites are designed with a 5-year lifespan and will be replaced by successive increments, rather than relying on a single, linear production approach. Successive increments will be developed and launched under separate prototype OTAs.

According to a contracting official, due to their reported speed and accessibility as prototyping vehicles, OTAs helped the agency attract and retain NDCs that otherwise would not be working with the office. For example, they said that their OTAs were structured closer to commercial contracts than FAR contracts, which lowered the barrier for NDCs to work with the agency. The efforts will provide warfighting, communications and missile warning satellite capabilities. These efforts plan to field more than 100 satellites by 2026. In a recent report, however, we highlighted potential issues with this development approach, though not OTA use specifically.[39] We noted that the Space Development Agency’s iterative development is inconsistent with leading practices and increases the risk of unnecessarily investing in new efforts without delivering on promised capabilities intended to support critical missions.

Prototype OTA to Production Using Follow-On Production Authority

Two of 18 selected efforts plan to use follow-on production authority to deliver capabilities. In both cases, officials emphasized that the ability to move noncompetitively into production was the main benefit of this approach. Follow-on authority allows for either a production OTA or FAR contract award, and officials told us that this choice of procurement approach was less important than the potential time savings from a noncompetitive transition accessible through this authority.

The Space Force awarded prototype OTAs to four teams of awardees in September 2023 to competitively prototype a software-intensive open-architecture system to support development and delivery of a command-and-control capability for missile warning satellites. Space Force officials stated that they considered a prototype OTA because it could allow them to transition directly into follow-on production noncompetitively, which would save significant time. Officials said that the effort is smaller-scale and software-intensive rather than a hardware-based effort, which makes it a better fit for using follow-on production authority. Space Force officials also said that using a prototype OTA helped reduce the overall source selection timeline by about 2 to 3 months from an expected 5-month process. They explained that they used a flexible and streamlined source selection process with oral presentations, rather than the more standardized written or oral procedures typically used under the FAR.[40]

This effort is conducting prototyping under the middle tier of acquisition pathway for rapid prototyping. The Space Force plans to award a follow-on production OTA or FAR- based contract in 2028 and transition to the software acquisition pathway to build additional software capabilities onto the prototype system, according to officials.

The second example is an Army effort supporting integration of new missile and ammunition technologies onto an existing mobile air-defense system.[41] The Army initiated this effort on the middle tier of acquisition rapid prototyping pathway in 2023. It awarded two OTAs in September 2023 to prototype and test a new missile capability to defend against missiles and other ranged threats, such as uncrewed aerial vehicles. The Army intends to achieve an initial operational capability by fielding a limited quantity (two platoons with 48 missile interceptors apiece) by March 2028.[42] Army officials said that using the middle tier of acquisition pathway coupled with an OTA allowed them to meet their accelerated timeline for this effort. The Army anticipates transitioning to the major capability acquisition pathway at Milestone C, or low-rate initial production, in fiscal year 2028.[43] As of March 2025, the Army is assessing the option of using the follow-on production authority to support this transition.

Prototype OTA to Production FAR Contract Without Using Follow-on Authority

Ten of the 18 selected efforts have awarded or plan to award FAR contracts to conduct additional development and testing before entering into FAR production contracts.

Of these 10 efforts, at least two have transitioned to production as of March 2025. For example, the Army initiated the first increment of a ground-based air defense weapon system in 2018 on the urgent capability acquisition pathway to address an immediate need for air defense capability identified by senior Army leadership. The Army awarded three prototype OTAs in 2018 and 2019, which allowed it to move faster on the effort, according to contracting officials. The Army fielded its first vehicles in 2021, fielded a battalion in fiscal year 2024, and plans to complete fielding of another battalion in the first quarter of fiscal year 2026. After using an OTA in the initial prototyping and fielding phase, the Army transitioned to a FAR contract to procure the remaining vehicles.

Of the remaining eight efforts, most are still under development and plan to transition into production within the next 6 to 12 months. For example, for a space anti-jamming satellite effort, the Space Force reported awarding prototype OTAs in February and March 2020 to develop critical technologies and reduce risk for the production phase. This effort transitioned to the major capability acquisition pathway in June 2024 to further mature and scale the prototyped technologies. The Space Force plans to launch the two resulting prototypes in November 2025 and January 2026, and anticipates awarding a FAR contract in the third quarter of fiscal year 2025 to develop advanced anti-jamming capabilities. The Space Force chose a FAR production contract because of the forecasted costs and additional development required to properly scale the capability to the larger requirements.

Production Efforts Still to Be Determined

The remaining four selected efforts are prototyping under OTAs and their future paths have not yet been determined. One of these efforts anticipates entering production in 2027. Two other efforts do not anticipate entering production within the next several years. Army officials noted several factors that will influence their decision to transition into production and their contracting strategy, including the outcome of the post-prototyping developmental and operational testing and the ability and willingness of the current NDCs used by the program to move into a FAR contract environment.

The fourth effort was an Army self-propelled howitzer effort. The Army awarded an OTA in 2019 to develop a self-propelled howitzer and specific enabling technologies on the middle tier of acquisition for rapid prototyping pathway. The Army planned to extend the range of its current self-propelled howitzer system, Paladin, by upgrading the top half of the system, consisting of the turret and gun tube that fire the munitions. However, this effort experienced significant development challenges and the Army canceled it in 2023. For example, the Army found that the upgraded turret and gun tube could not withstand multiple gun firings due to the force from improved exceeding design limits.[44] In December 2022, the Army paused testing and ended the prototyping effort after determining that technical challenges made further development unwarranted. This outcome is generally attributed to the immaturity of key technologies, rather than other factors such as the choice of an OTA for the procurement approach. The Army is instead contemplating procurement of similar existing systems from industry by the end of fiscal year 2027.

DOD officials told us that like any procurement approach, OTAs are not a guaranteed solution and do not ensure successful outcomes. They noted that in the case of complex weapon system acquisitions, a well-written OTA cannot compensate for a poorly planned acquisition. These statements generally align with our decades of prior work, which demonstrate that knowledge-based acquisition practices and a sound business case are essential to achieving better program outcomes.[45] Over the years, we have identified a number of factors that undermine business cases and drive cost and schedule overruns, such as poorly defined or changing requirements, immature technologies, and overly optimistic assumptions.

Factors Such as Increased Protections and Workforce Availability Influenced Use of Standard Contracts for Production

DOD contracting officials from multiple components cited various factors that influenced their use of FAR contracts for production rather than using production OTAs. These factors include greater risk protections and a cultural preference for using FAR contracts, the type of product being acquired, and the type of contractor. As a result, officials said that they believed OTAs may not be the appropriate contracting approach for every program’s production effort. In addition, these officials noted that the only way to award a production OTA is through the follow-on production authority, which requires certain conditions be met. DOD officials also cited contracting workforce experience and availability as potential limiting factors to expanded use of OTAs in the future.

Risk Protections and Cultural Preference

Contracting officials highlighted a range of specific protections included by default in FAR contracts that may not be included in OTAs.[46] For example, the FAR includes provisions that give the federal government the unilateral right to terminate a contract, while a contractor generally may not unilaterally terminate a contract. In contrast, DOD officials told us that some OTAs permit mutual termination, allowing a contractor to withdraw from a project without requiring government consent.

DOD officials also highlighted the benefits of FAR clauses that allow more oversight into contractors’ reported costs. For example, multiple officials stated that the clauses included within FAR contracts may require additional data from contractors that would support the reasonableness of proposed costs. For example, covered noncommercial FAR contracts require compliance with applicable cost accounting standards, which provide a standardized framework for calculating and categorizing contractor costs. Compliance with these standards can help ensure contractors are appropriately allocating costs and reduce the risk of government overpayment. One contracting official who had executed a production OTA told us that, in their opinion, the government would have negotiated a better deal under a FAR contract because the FAR clauses would have required the contractor to provide greater insight into their proposed costs, among other things. In another example, an official stated that with FAR contracts, it is easier to involve DOD audit services to have additional oversight and help ensure DOD is paying a fair and reasonable cost.

Officials from multiple DOD components stated that the wide-ranging set of protective clauses included in FAR-based contracts are likely a safer, more culturally accepted option for contracting officials supporting major weapon system efforts. For example, Army officials stated that they intended to move into production using OTAs but were told by Army leadership that the efforts were too expensive to use OTAs and needed to use FAR contracts instead.[47]

Type of Product

The type of product DOD acquires can also influence the choice of a FAR contract or an OTA for production efforts. For example, DOD officials told us that acquisitions of existing commercial products are generally considered less risky and may be better candidates for a production OTA. In contrast, DOD officials stated that complex new weapon system designs or large, high-dollar acquisitions may be better candidates for a FAR contract. These statements align with our findings above that DOD typically used production OTAs to support either software or IT systems, or weapon systems derived from commercial products, rather than more expensive, government-unique weapon systems.

Type of Contractor

DOD officials stated that if DOD is working primarily with NDCs, then an OTA may be a better choice. For example, NDCs may not have experience with FAR clauses or have the necessary tools such as business systems required to comply with cost accounting requirements. In contrast, officials said that if DOD is working primarily with traditional contractors it may be more appropriate to award a FAR contract than an OTA. According to these officials, this is because a primary justification for using OTAs is to reduce barriers to entry for NDCs working with the government. By definition, traditional contractors have previously worked with DOD and generally have business systems and processes that are FAR-compliant, so it is not necessary to leave behind the risk protections of FAR contracts.

Follow-on Production Authority

As noted above, DOD is required to meet certain criteria, such as demonstrating a successful prototype, to use the authority to award a follow-on production OTA or FAR contract. DOD officials told us that it can be more difficult for larger-scale development efforts to meet these criteria and use this authority, as compared to smaller-scale projects such as a software application prototype. Officials also said that follow-on production authority offers an effective method to deliver prototypes relatively quickly but lacks provisions for sustainment and maintenance that are critical for fielded weapon systems. For example, major hardware-intensive systems are complex, and the underlying technologies may not be ready at the conclusion of prototyping to immediately transition into production. Army officials said they ended up not using follow-on production authority for a missile defense effort because they needed to continue developing and testing their technologies and building logistics and sustainment plans and documentation. Other contracting officials also said that DOD may have to build new production facilities and develop supply chain networks for more complex weapon systems, and these activities may not be completed in time to support an immediate transition using follow-on production authority.

DOD can only award a production OTA using the follow-on authority at 10 U.S.C. § 4022(f). Efforts that do not meet the follow-on authority requirements cannot use this authority and must award FAR contracts instead if they continue into production. Officials from an Army missile effort told us that they did not pursue the follow-on production authority for this reason, and instead transitioned to FAR contracts on the major capability acquisition pathway to continue maturing their technology prior to entering production.

Recently proposed legislation may change these requirements. Specifically, Section 309 of the proposed FoRGED Act would amend 10 U.S.C. § 4022 and instead allow DOD to award production OTAs to produce emergent or proven technology, when justified, without having to award and successfully complete a prototype OTA first. Contracting officials told us that this change could encourage greater use of production OTAs and potentially attract more NDCs. However, they also stated that this approach would require careful planning and vetting because there would be no prototyping phase to test the adequacy of key technologies to meet DOD’s needs.

Workforce Experience and Availability

Defense Acquisition University guidance states that use of OTAs requires experienced, empowered agreements officers who are comfortable using their judgment to adequately manage risks without the process and protections inherent within the FAR. Officials from one DOD component told us that they have turned down some requests to award production OTAs due to a lack of experienced agreements officials. DOD officials also told us that DOD may not have enough experienced agreements officers available to award and oversee OTAs for major weapons system efforts, especially if demand for OTA use increases and if DOD’s acquisition workforce is reduced. DOD officials noted that OTAs do not inherently have as many guardrails as FAR contracts, so relying on less experienced contracting personnel could lead to challenges with OTA execution and oversight.

DOD Officials Cited Benefits of OTAs for Selected Efforts and Reported Minor Challenges with Standard Contracts for Production

DOD officials from most of the 10 selected efforts that have transitioned or plan to transition to FAR contracts cited benefits of using OTAs to prototype, such as shorter times to award, flexibility in contracting terms, and attracting NDCs. These officials generally did not report challenges when transitioning from prototype OTAs to FAR contracts for production.

Time to award. Officials reported procurement administrative lead times from about 1 month to 16 months for OTAs of selected efforts. By way of comparison, our prior work found award times ranged from 45 days to 370 days for a nongeneralizable sample of 11 prototype OTAs.[48] We also previously reported award times from 27 days to 8 months for the OTAs awarded to develop COVID-19 vaccines.[49]

In general, DOD officials from our selected efforts reported that the use of OTAs helped them save time overall. For example:

· DOD officials reported savings from using a modified proposal review process. Specifically, officials from one effort used an oral proposal review process in person with contractors, rather than relying on a paper-based solicitation review. According to officials, this method saved upwards of 3 months just in the proposal review period.

· Officials from several efforts told us that OTAs do not require adherence to the FAR’s detailed and time-consuming requirements, such as publishing formal requests for proposals or conducting formal source selection methods. One official said that the average time from a solicitation release to proposal receipt was between 3 and 6 months for a FAR contract, as compared to 1 to 2 months for an OTA.

· Officials said that administrative review processes were generally faster for OTAs as compared to FAR contracts. For example, multiple Army officials stated that the standard internal review and approval time frames for OTAs were at least 2 months shorter.

However, DOD’s Other Transactions Guide states that it is a myth that OTAs will always be awarded faster than other procurement approaches. For example, the guide notes that all terms and conditions in an OTA are negotiable, so OTAs could take longer to award than a FAR contract. The guide also states that if source selection and approval processes are not streamlined, then OTA awards can take longer.

Further, officials from two efforts identified minor challenges in transitioning back to a FAR environment, such as collecting certified cost or pricing data.[50] Officials from one effort reported that ensuring compliance with these additional FAR requirements added up to 3 months to the effort’s schedule.

OTA flexibilities. DOD officials told us that they saw benefits from OTA flexibilities during the prototyping phase. For example, officials stated they reopened competition to award an additional deliverable for one effort. Officials explained that they would not have been able to make this change as easily with a FAR contract. In another example, one DOD agency developed a secure information technology architecture using a prototype OTA followed by a production OTA. Officials stated that they tailored the architecture to meet the needs of multiple DOD components. They stated that this would not have been possible to do in a FAR contract environment. Specifically, they said that using an OTA allowed them to tailor the technology capabilities of their cloud-based prototype to meet the unique needs of multiple DOD offices. DOD officials noted that a FAR contract would have been too restrictive and would not have allowed tailoring to meet multiple sets of needs.

DOD officials also cited the benefit of negotiating directly with vendors and working collaboratively on statements of work. Under an OTA, the government may share draft agreement language with the vendor and collaborate in real time to obtain input and refine terms and conditions. In contrast, in a FAR-based competitive contract, direct communication during the solicitation phase is generally restricted and must follow standardized procedures defined in the request for proposal process under FAR part 15.[51]

NDC participation. Most efforts used NDCs as subcontractors, and NDCs provided a range of contributions. For example, officials for several efforts noted that NDCs allowed them access to highly specialized areas of expertise and novel or innovative approaches to software development. Officials also stated that NDC participation was critical to the success of their projects. Specific examples include specialized components related to high-energy lasers (e.g., specialty optics) and providing high strength alloys used for artillery applications.

The prime contractors for most of the analyzed efforts were traditional defense contractors such as Raytheon, Lockheed Martin, and Northrup Grumman. In two cases, however, the Army selected NDCs as prime contractors.

Five of 18 efforts maintained, or plan to maintain, NDC participation when transitioning from the prototype to the production phase. Seven efforts have not yet determined their NDC transition plans. The remaining six efforts either do not have NDCs participating, or they do not have an applicable production phase.

DOD officials reported only minor challenges when transitioning NDCs intro production. For example, two Army efforts experienced difficulties with NDCs’ transition from an OTA to a FAR contract due to cost accounting requirements. Officials from one effort stated that the NDCs they worked with were used to submitting proposals in a commercial context and had difficulty adapting to government-unique requirements. Officials from both efforts also stated that their NDCs experienced challenges with cost requirements, such as lacking a government-approved cost accounting system. In one case, the prime contractor acquired the NDC and monitored its cost information. In the other case, the prime contractor helped the NDCs overcome cost compliance challenges, although the effort added two to three months to the program timelines. Officials from two other Army efforts under development noted that their NDCs’ ability and willingness to transition into a FAR environment after the prototyping phase would influence whether their efforts remained as OTAs or transitioned to FAR contracts.

DOD is in the process of collecting lessons learned about OTA use. Officials from the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment stated that they plan to continue refining their data collection process, which informs the annual report to Congress. Additionally, contracting officials from multiple DOD components stated that they are identifying and sharing lessons learned, including those on transitioning prototype OTAs into production. Additionally, an Army contracting office developed an OTA guidebook that included best practices for transitioning prototype OTAs.

Conclusions

DOD has increasingly relied on OTAs to help leverage commercially available capabilities, attract nontraditional defense contractors, and broaden the defense industrial base. Congress and the current administration have also encouraged greater use of OTAs going forward for software acquisitions as well as major weapon system development. However, because OTAs do not always include default protections and rely on the individual judgment of agreements officers instead, they can carry increased risks compared with FAR contracts. DOD officials acknowledged that OTAs do not guarantee successful outcomes and that a well-written OTA cannot overcome a poorly planned acquisition.

DOD is in the process of collecting lessons learned on the use of OTAs. DOD has also improved its visibility into its use of OTAs, specifically the transition of prototype OTAs into production OTAs and its use of certain consortia-based OTAs. However, gaps still remain in DOD and congressional decision-makers’ visibility into the use of consortia-based OTAs, and the extent to which prototype OTAs transition into capabilities through FAR production contracts. Improved data in these two areas would help DOD gauge what changes, if any, are needed to ensure OTAs are delivering capability to the warfighters as well as attracting nontraditional defense contractors, two of the overarching goals for using OTAs.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following two recommendations to DOD:

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment develops and implements a systematic process to track FAR production contracts using follow-on production authority. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment reports data fully and accurately for individual consortia-based OTAs to identify the consortia members performing on projects. (Recommendation 2)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to DOD for review and comment. In its written comments (reproduced in appendix IV), DOD concurred with both of our recommendations.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Defense, the Secretary of the Army, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov/.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at sehgalm@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix V.

Mona Sehgal

Director, Contracting and National Security Acquisitions

List of Committees

The Honorable Roger Wicker

Chairman

The Honorable Jack Reed

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

United States Senate

The Honorable Mike Rogers

Chairman

The Honorable Adam Smith

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

House of Representatives

Conference Report 118-301 accompanying the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024 directed GAO to review the Department of Defense’s (DOD) use of other transaction agreements (OTA). Our report examines (1) the extent to which DOD used prototype and production OTAs and data it collects to determine the effectiveness of OTAs, and (2) how selected DOD weapon system efforts using prototype OTAs planned to deliver capabilities using OTAs or Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) contracts.

To assess the extent to which DOD used prototype and production OTAs, we analyzed Federal Procurement Data System (FPDS) data from fiscal years 2021 through 2024. This time frame covers data available after fiscal year 2020, a year significantly influenced by federal spending supporting the COVID-19 response. For example, DOD awarded around $9 billion to support vaccine development and manufacturing during this fiscal year, after adjusting for inflation. We then compared these data against DOD’s most recent annual report to Congress, which are generated through a department-wide manual data request. We found the data to be reliable for discussing DOD’s use of OTAs during this time.

To assess the data DOD collects to assess the effectiveness of OTAs, we analyzed available FPDS data on production OTAs awarded using DOD’s follow-on production authority, consortia-based OTAs, and nontraditional defense contractor (NDC) participation from fiscal years 2021 through 2024. We compared these data against DOD’s annual report to Congress for fiscal year 2023, and additional data sources such as contract documentation for individual weapon system efforts. We also interviewed contracting headquarters officials from the military services and other relevant DOD components, including agreement officers—officials specially trained and warranted to award OTAs. For the purposes of this report, relevant DOD components had more than $400 million of OTA obligations during our time frame, including the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, Defense Counterintelligence and Security Agency, Defense Health Agency, Defense Information Systems Agency, Space Development Agency, Special Operations Command, and Washington Headquarters Service.

To examine how selected DOD weapon systems using prototype OTAs planned to deliver capabilities, we selected a nongeneralizable sample of 18 of DOD’s major weapon systems. First, we analyzed our annual reports assessing selected DOD weapon systems from fiscal years 2017 through 2024. These reports analyze dozens of DOD’s costliest weapon systems each year. We selected this time range to align with DOD’s increase in OTA obligations. We identified 18 overall efforts that had used prototype OTAs. Within this universe, we found that the Army or Space Force managed nearly all of these efforts (10 and six, respectively).

We established selection criteria for weapon portfolios—groups of efforts with a particular focus, such as aviation or ground vehicles—which had more than three efforts using OTAs. To avoid over-counting, we did not increase the count of OTA use for efforts that may have awarded multiple OTAs to support the same effort. For example, if an effort awarded four prototype OTAs to multiple contractors for competitive prototyping, we counted this is as single use of OTAs for that effort. Three portfolios containing 13 efforts met our criteria: Army air and missile defense (three), Army long range fires (four), and Space Force/Space Development Agency space systems (six). We did not select two other Army portfolios with OTA use because they did not meet our criteria: future vertical lift (2), and soldier lethality (1). After our initial portfolio selection, we identified five additional efforts within the Army air and missile defense portfolio that were also using prototype OTAs, and we also included them in our nongeneralizable sample. This brought our total to 18 efforts: eight from Army air and missile defense, four from Army long range fires, and six from space systems.

We analyzed documentation such as acquisition strategies, status briefings, and awarded contracts or OTAs to identify how these 18 selected efforts planned to transition their prototyping efforts into capability delivery. We also collected data for four selected consortia-based OTAs that aligned with the three portfolios mentioned above, including the extent to which NDCs participate in these consortia. We interviewed acquisition and contracting officials from each selected effort.

We conducted this performance audit from April 2024 to September 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Appendix II: Summary of Selected Weapon Development Efforts Using Prototype Other Transaction Agreements

Table 4: Summary of Selected Weapon Development Efforts Using Prototype Other Transaction Agreements (OTA)

|

Procurement approach supporting capability delivery |

Effort name |

Date of initial OTA prototype award |

Production status |

Acquisition approach |

Capability fielding status |

|

Prototype OTA only |

Tranche 1 Tracking Layer |

July 2022 |

Not applicable |

Middle tier of acquisition |

September 2026 (planned) |

|

Tranche 1 Transport Layer |

February 2022 |

Not applicable |

Middle tier of acquisition |

January 2026 (planned) |

|

|

Prototype OTA to follow-on production authority |

Future Operationally Resilient Ground Evolution (FORGE) - Command and Control |

August 2020 |

Planned for July 2026 (entering the software acquisition pathway) |

Middle tier of acquisition |

July 2026 (planned) |

|

Maneuver Short Range Air Defense Increment 3 |

September 2023 |

Planned for second quarter of fiscal year 2028 |

Middle tier of acquisition; transition to major capability acquisition |

2028 (planned) |

|

|

Prototype OTA to production outside of follow-on authority |

Precision Strike Missile |

June 2020 |

September 2025 (planned) |

Urgent capability acquisition and major capability acquisition |

February 2026 (planned) |

|

Long Range Hypersonic Weapon System |

Fourth quarter fiscal year 2019 |

To be determined |

Middle tier of acquisition |

Third quarter of fiscal year 2025 (planned) |

|

|

Army Integrated Air and Missile Defense |

November 2019 |

Approved for full-rate production in fiscal year 2023 |

Major capability acquisition for hardware elements; software acquisition for software elements |

Third quarter of fiscal year 2023 (fielded) |

|

|

Maneuver - Short Range Air Defense Increment 1 (Sgt. Stout) |

September 2018 |

September 2020 |

Middle tier of acquisition; transition to major capability acquisition |

Third quarter of fiscal year 2021 (fielded) |

|

|

National Security Space Launch |

January – February 2016, October 2018 |

FAR contract awarded |

Not applicable |

Fielded |

|

|

Strategic Mid-Range Fires |

Fiscal year 2020 |

June 2025 (planned) |

Middle tier of acquisition |

Fiscal year 2024 (fielded) |

|

|

Indirect Fire Protection Capability Increment 2 |

September 2021 |

March 2025 |

Middle tier of acquisition; transition to major capability |

Fourth quarter of fiscal year 2025 (planned) |

|

|

Lower Tier Air and Missile Defense |

October 2019 |

Second quarter of fiscal year 2025 (planned) |

Middle tier of acquisition; transition to major capability acquisition |

Not applicable |

|

|

Protected Tactical SATCOM |

2020 |

To be determined |

Middle tier of acquisition; transition to major capability acquisition |

November – December 2025, and March – April 2026 (planned) |

|

|

Deep Space Advanced Radar Capability |

February 2022 |

May 2025 (planned) |

Middle tier of acquisition; transition to major capability acquisition |

January 2027 (planned) |

|

|

To be determined |

Extended Range Cannon Artillery |

July 2019 |

To be determined |

Not applicable – canceled |

Not applicable |

|

Indirect Fire Protection Capability – High Energy Laser |

July 2023 |

Will not enter production within the next several years |

To be determined |

Third quarter of fiscal year 2025 (planned) |

|

|

Indirect Fire Protection Capability – High Power Microwave |

December 2022 |

Will not enter production within the next several years |

To be determined |

Fourth quarter of fiscal year 2024 (fielded) |

|

|

Directed Energy Maneuver Short Range Air Defense – Increment 2 |

July 2019 |

Fiscal year 2027 (planned) |

To be determined |

Fourth quarter of fiscal year 2023 (fielded) |

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Defense information. | GAO‑25‑107546

Appendix III: Nontraditional Defense Contractors’ (NDC) Contributions to Selected Weapon Development Efforts

Table 5: Nontraditional Defense Contractors’ (NDC) Contributions to Selected Weapon Development Efforts and Production Status According to DOD

|

Production approach supporting capability delivery |

Effort name |

NDCs transitioned into production? |

NDC contribution |

|

Prototype other transaction agreement (OTA) only |

Tranche 1 Tracking Layer |

Not applicable, no production phase |

Providing key technologies such as the spacecraft itself, telescopes, and encryption boxes for communications. |

|

Tranche 1 Transport Layer |

Not applicable, no production phase |

Providing key technologies such as the spacecraft itself, telescopes, and encryption boxes for communications. |

|

|

Prototype OTA to follow-on production authority |

Future Operationally Resilient Ground Evolution (FORGE) - Command and Control |

To be determined |

Providing software development. |

|

Maneuver Short Range Air Defense Increment 3 |

To be determined |

To be determined |

|

|

Prototype OTA to production outside of follow-on authority |

Precision Strike Missile |

Not applicable – The Army is working with a traditional defense contractor under a cost sharing arrangement rather than using NDC participation to meet statutory requirements for use of an OTA. |

|

|

Long Range Hypersonic Weapon System |

Yes |

Providing the critical technology and manufacturing for two-dimensional carbon compound tape wrap and fabrication of Thermal Protection System critical components |

|

|

Army Integrated Air and Missile Defense / Integrated Battle Command System |

Not applicable |

Contributing to a system providing air tracking data. |

|

|

Maneuver Short Range Air Defense Increment 1 (Sgt. Stout) |

Yes |

Providing key technologies and systems, such as an integrated-weapons platform turret with a cannon and machine gun. |

|

|

National Security Space Launch |

Not applicable |

Not applicable |

|

|

Strategic Mid-Range Fires |

Planned to transition |

Building, delivering, and testing the actuation system for the Payload Deployment System, which is critical for the ability to handle the system fully loaded while transporting the system and when elevated to execute the mission. |

|

|

Indirect Fire Protection Increment 2 |

To be determined |