U.S. TERRITORIES

Public Debt and Economic Outlook —2025 Update

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Yvonne Jones at JonesY@gao.gov or Latesha Love-Grayer at LoveGrayerL@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107560, a report to congressional committees

Public Debt and Economic Outlook – 2025 Update

Why GAO Did This Study

The five permanently inhabited U.S. territories—the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, Guam, USVI, CNMI, and American Samoa—have borrowed through financial markets to bridge the gap between tax receipts and the financial resources required to fund government programs.

The territories all face challenges to achieving continued economic growth and financial accountability, both of which are key to debt management. GAO has previously reported on some of the common challenges, including (1) the location of the islands, which leads to a high cost of energy and imported goods; (2) increasing vulnerability to frequent and severe episodes of extreme weather; (3) undiversified economies based on few industries with limited job opportunities; and (4) outmigration and population loss.

In 2016, Congress passed and the President signed the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act. It contains a provision for GAO to review the territories’ public debt every 2 years. This is the fifth report in this series.

In this report, for each of the five territories, GAO presents public debt figures and describes risk factors that may affect their ability to repay public debt, among other updates. GAO analyzed audited financial statements for fiscal years 2020 through 2023, as available.

GAO also reviewed demographic and economic data and interviewed officials from the territories’ governments.

What GAO Found

The U.S. territories’ levels of public debt vary, along with the factors that affect each of their capacities for economic growth and debt repayment. To assess their ability to repay debt, GAO used the most recently available audited financial statements. Audited financial statements for some territories are almost 2 years late, and independent auditors have identified issues that raise data reliability concerns for the available statements. These financial reporting limitations can lead to poor financial decisions and lost access to capital markets.

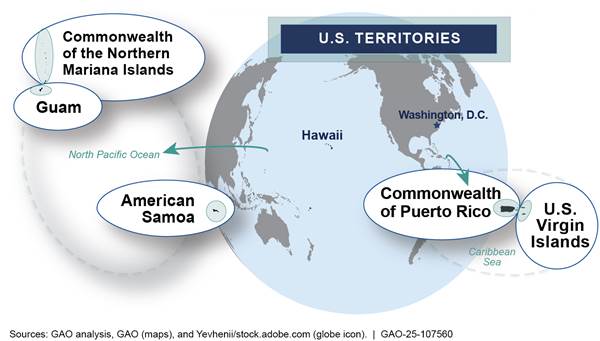

Geographic Locations of U.S. Territories

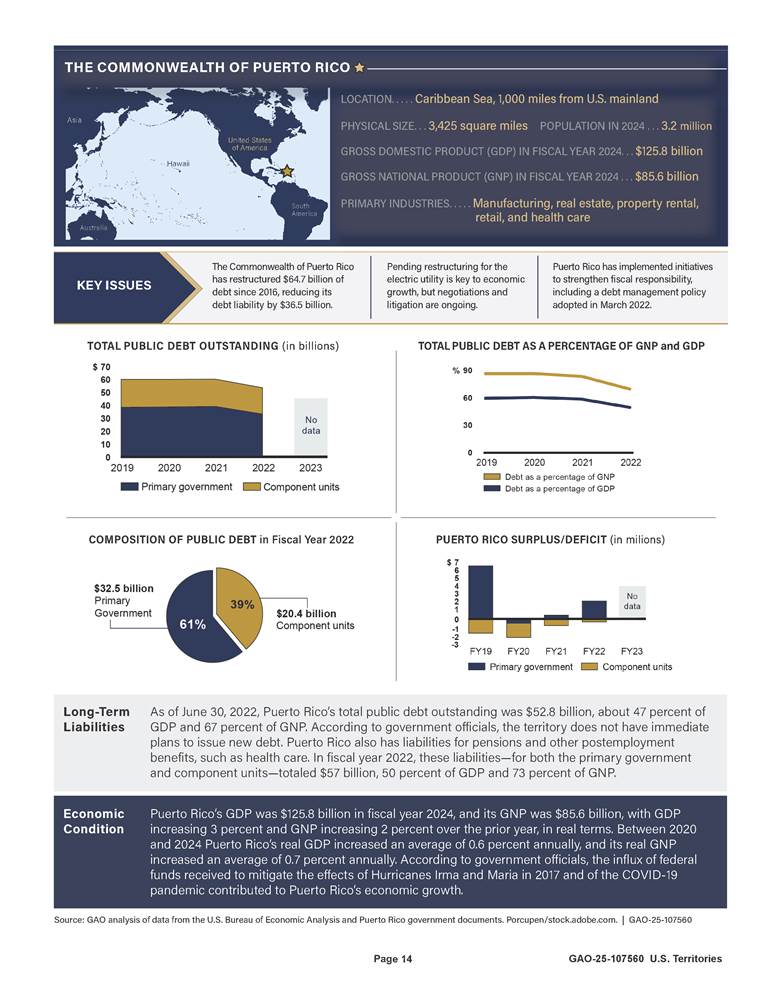

Commonwealth of Puerto Rico: As of June 30, 2022, total public debt outstanding was $52.8 billion, 47 percent of gross domestic product (GDP). Negotiations and litigation to restructure the electric utility debt are ongoing, and the utility has been struggling to make its pension payments in the meantime.

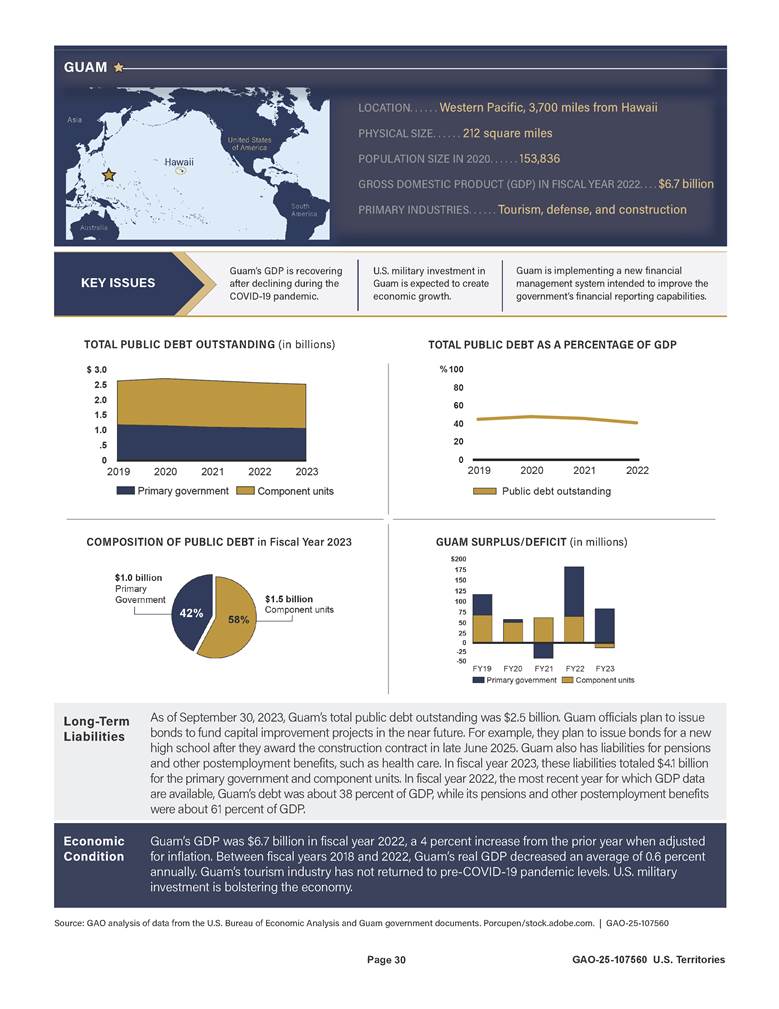

Guam: As of September 30, 2023, total public debt outstanding was $2.5 billion. 2023 GDP data are not available, but the fiscal year 2022 total public debt was $2.6 billion, about 38 percent of GDP. Its tourism industry has not returned to pre-COVID-19 levels, but U.S. military investment is bolstering the economy.

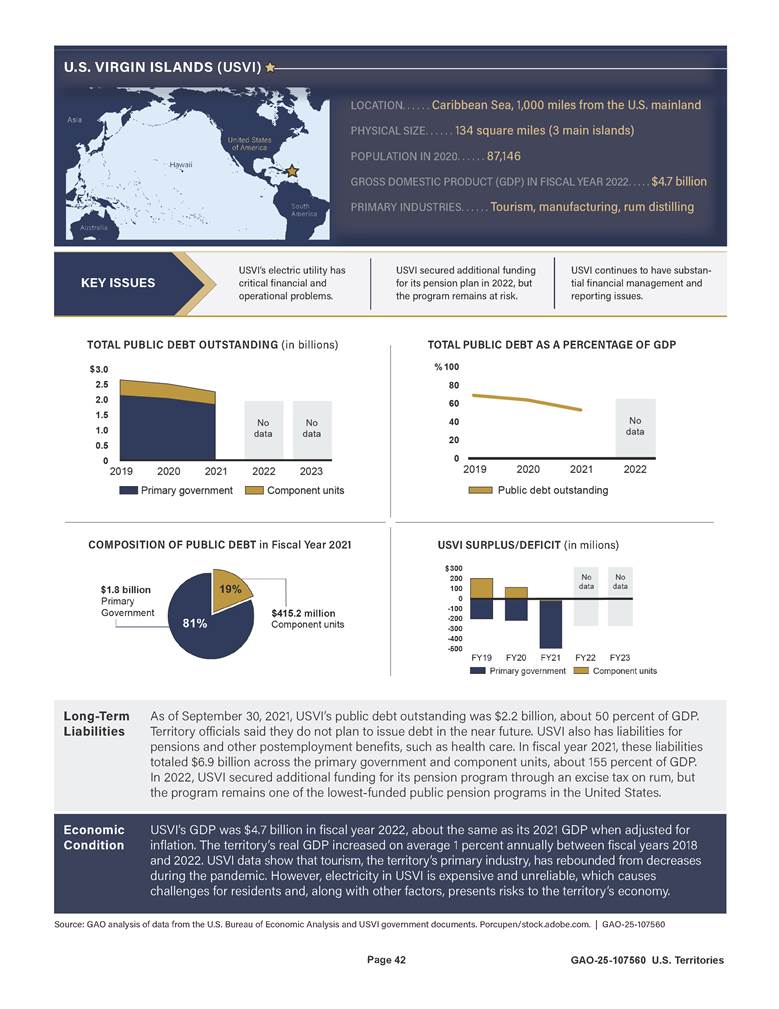

U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI): As of September 30, 2021, total public debt outstanding was more than $2.2 billion, or 50 percent of GDP. USVI’s electric utility has critical financial and operational problems, which create challenges for residents and can inhibit economic development.

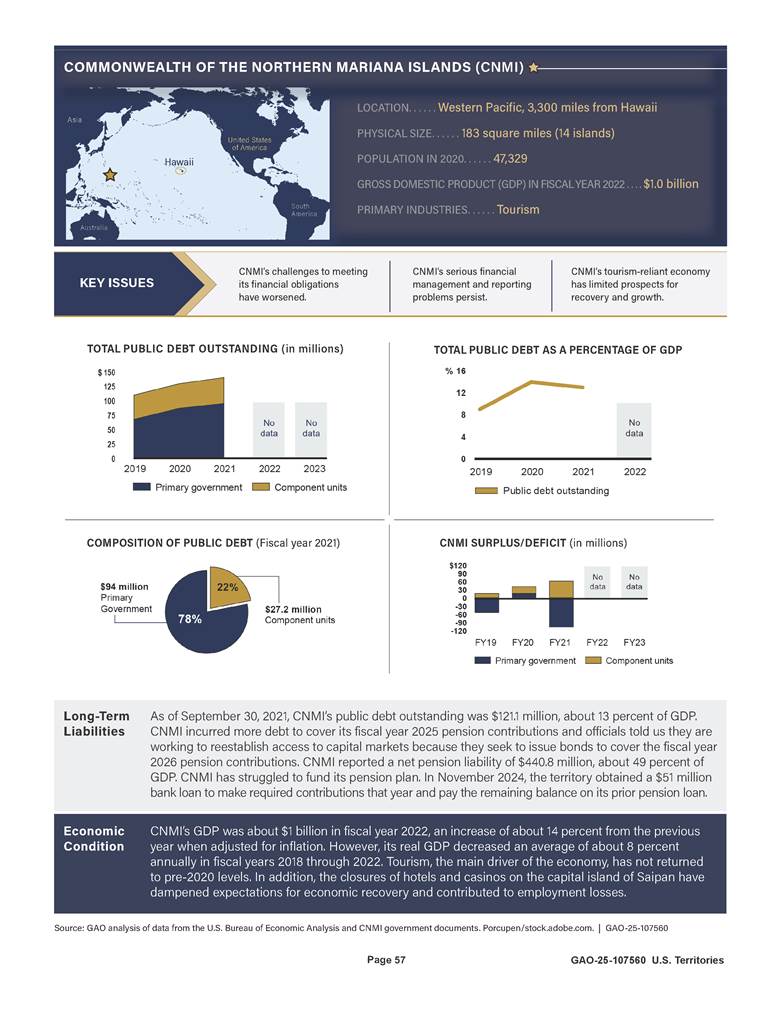

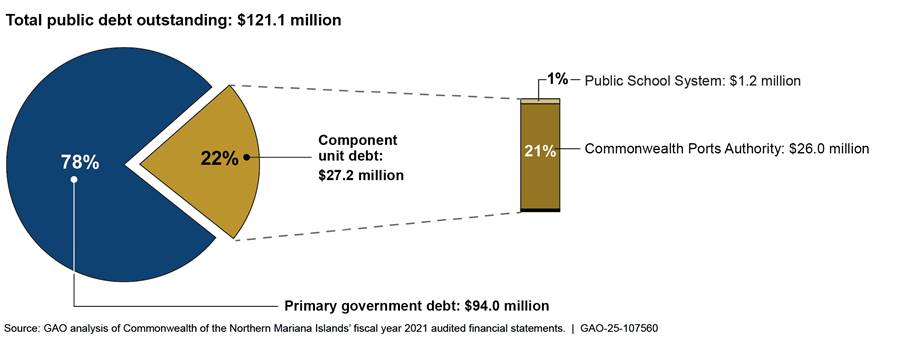

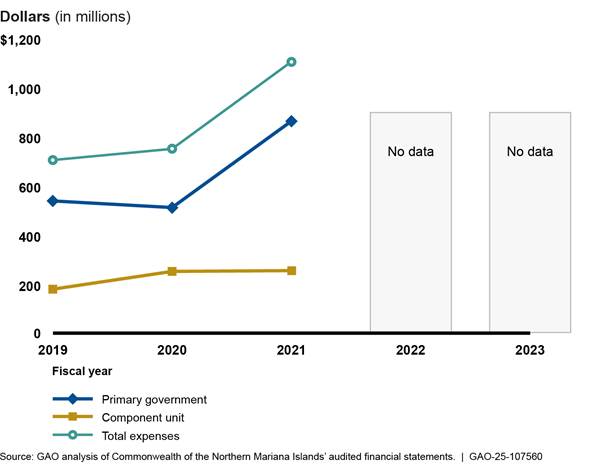

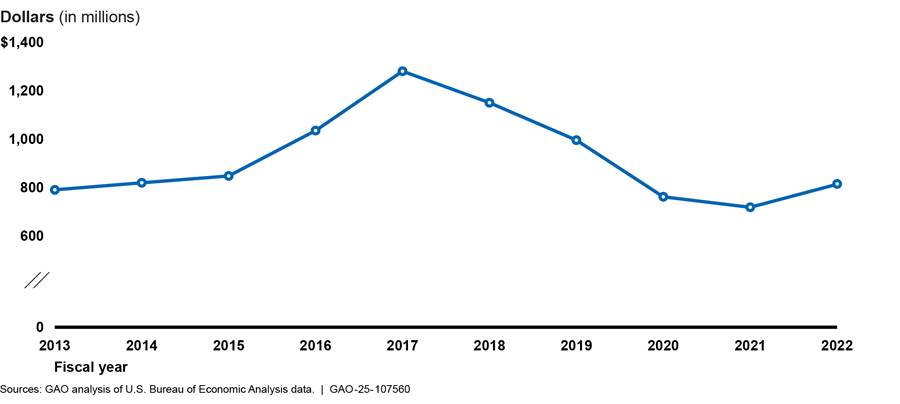

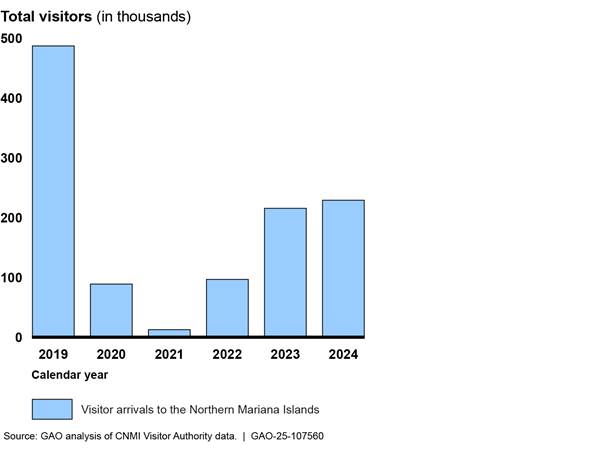

Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI): As of September 30, 2021, total public debt outstanding was $121.1 million, about 13 percent of GDP. Its tourism-reliant economy has limited prospects for recovery, and the challenges to meet its financial obligations have deepened.

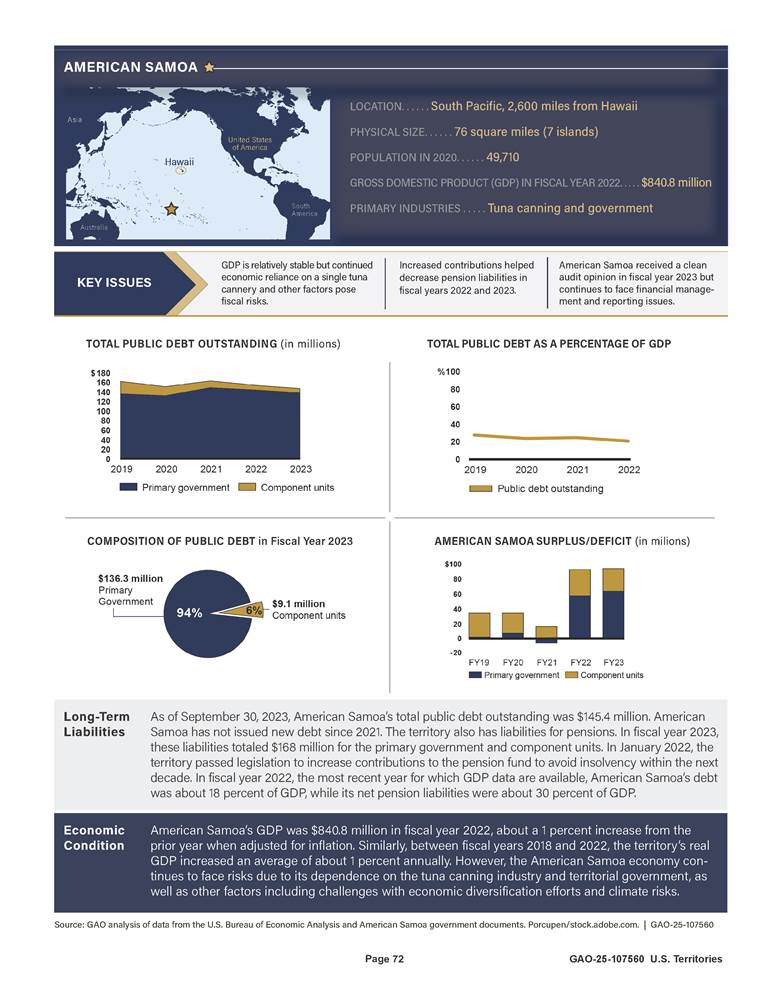

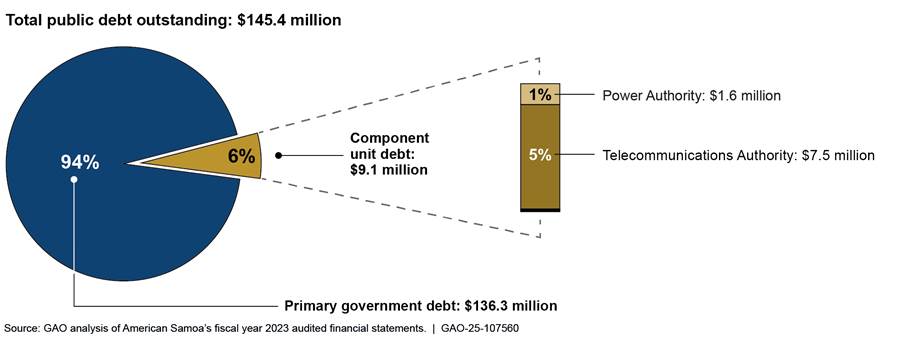

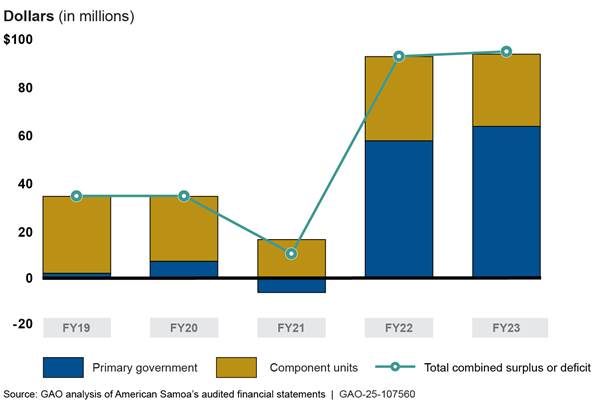

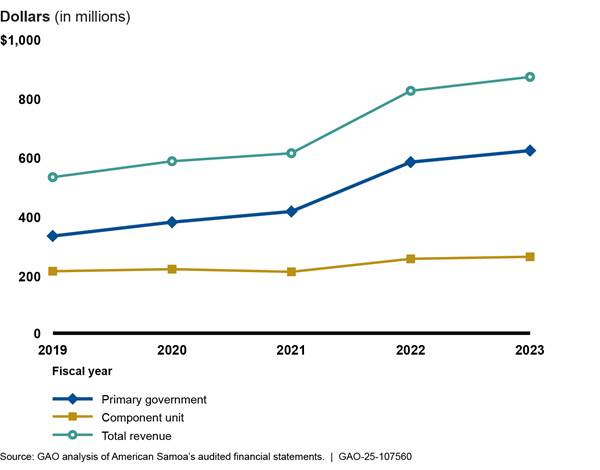

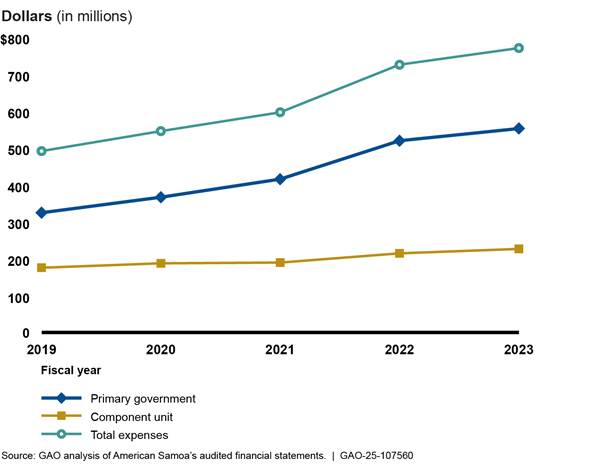

American Samoa: As of September 30, 2023, total public debt outstanding was $145.4 million. While 2023 GDP data are not available, the fiscal year 2022 total public debt was $152.4 million, about 18 percent of GDP. Its continued economic reliance on a single tuna cannery presents risks.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

Puerto Rico |

Commonwealth of Puerto Rico |

|

CNMI |

Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands |

|

FOMB |

Financial Oversight and Management

Board for |

|

FY |

fiscal year |

|

GDP |

gross domestic product |

|

GNP |

gross national product |

|

Moody’s |

Moody’s Ratings |

|

OPAL |

Oficina de Presupuesto de la Asamblea Legislativa |

|

PREPA |

Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority |

|

PROMESA |

Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act |

|

S&P |

S&P Global Ratings |

|

BEA |

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis |

|

USVI |

U.S. Virgin Islands |

|

WAPA |

USVI Water and Power Authority |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

June 30, 2025

The Honorable Mike Lee

Chairman

The Honorable Martin Heinrich

Ranking Member

Committee on Energy and Natural Resources

United States Senate

The Honorable Bruce Westerman

Chairman

The Honorable Jared Huffman

Ranking Member

Committee on Natural Resources

House of Representatives

The five permanently-inhabited U.S. territories—the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, Guam, the U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI), the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI), and American Samoa—continue to emerge from the challenging economic conditions resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic and recover from severe weather events. Each of these territories faces challenges to achieving continued economic growth and financial accountability, both of which are key to debt management.

The Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA) includes a provision for us to review the public debt of each U.S. territory every 2 years.[1] We issued reports on the territories’ public debt in October 2017, June 2019, June 2021, and June 2023.[2] For each of the five territories, this report updates information from our prior reports on (1) trends in public debt and composition; (2) trends in surpluses and deficits, including changes in revenue and expenses and their composition; and (3) risk factors that may affect each territory’s ability to repay public debt.

We analyze each territory as a distinct entity and report the results of our three objectives separately for each territory because the context related to each can vary, including differences in size, population, geography, and economies. We present the territories in order of the size of their respective economies, as measured by gross domestic product (GDP): Puerto Rico, Guam, USVI, CNMI, and American Samoa.[3] Each section begins with a summary page, highlighting the key issues and statistics that are most salient to each territory’s fiscal condition.

|

The primary government is any state or local government or special–purpose government with a separately elected governing body that is legally separate and fiscally independent of other state and local governments. Component units are legally separate entities for which the primary government is financially accountable. A component unit may be a governmental organization, a nonprofit corporation, or a for-profit corporation. Source: Government Accounting Standards Board. | GAO‑25‑107560 |

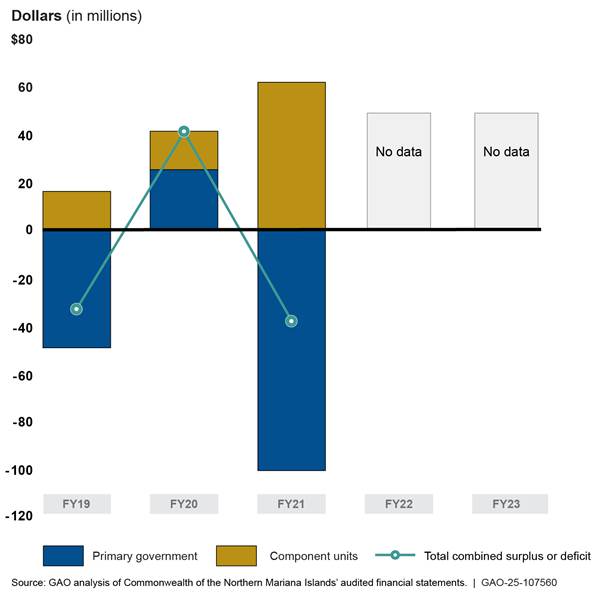

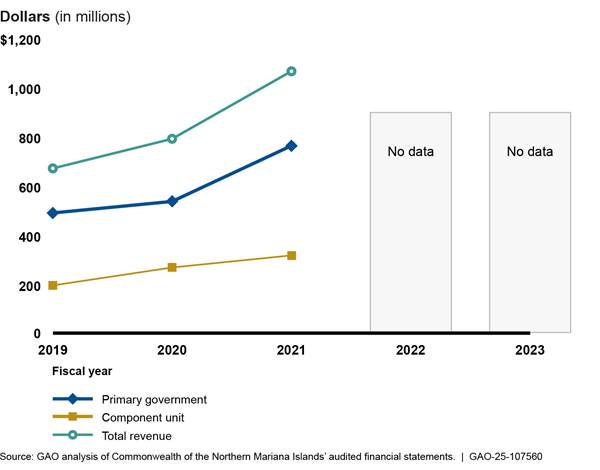

To describe trends in public debt, we analyzed financial data reported in each territory’s audited government-wide financial statements for the most recent fiscal years available as of June 1, 2025.[4] To provide consistency, we generally compared the most recent financial data available to the same data from 2 years prior. Although some territories may have more recent unaudited financial data, we generally use audited financial statement data because they are the most reliable data available. Since our prior report of June 2023, Puerto Rico issued audited financial statements for fiscal year 2022; Guam for fiscal years 2022 and 2023; USVI for fiscal years 2020 and 2021; CNMI for fiscal year 2021; and American Samoa for fiscal years 2022 and 2023. Government-wide financial statements include separate financial information for the territories’ primary government and component units (see sidebar).[5]

To describe recent trends in territories’ surpluses and deficits, we analyzed revenue and expense data for primary governments and component units from each territory’s audited government-wide financial statements. If total revenues exceeded total expenses, a territory would report a surplus for that fiscal year. On the other hand, if total expenses exceeded total revenues, a territory would report a deficit.[6]

Timely audited financial statements were not available from all territories. Accordingly, to provide more recent context about public debt and revenue and expenses, we interviewed officials from each of the five territorial governments, including departments of finance or treasury.

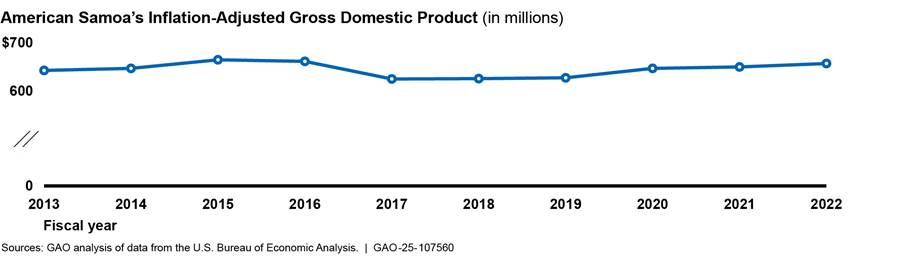

To determine risk factors that may affect each territory’s ability to repay its debt, we obtained and reviewed relevant documentation, reports, and analyses from the territorial governments and rating agencies. Because economic growth is key to debt sustainability, we also analyzed the most recently available GDP estimates from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) from 2013 to 2022 and population estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau from the 2010 and 2020 censuses.[7] For Puerto Rico, we analyzed the most recently available GDP and gross national product (GNP) estimates from the Puerto Rico Planning Board from 2014 to 2023.[8] We also interviewed officials from the Department of the Interior’s Office of Insular Affairs, which provides grants and technical assistance and support to the territories.

As a part of our analysis of risk factors affecting territories’ abilities to repay public debt, we also present available information on each territory’s liabilities for pensions and other postemployment benefits, since these are a fiscal risk not accounted for in our calculation of total public debt outstanding. We also include analysis of each territory’s financial management and reporting practices, given their importance for making informed financial decisions, maintaining access to capital markets, and managing federal awards.

To understand the reliability of financial information from each territory, we reviewed independent auditors’ reports on the territories’ annual financial statements and the types of opinions they expressed. To understand the territories’ financial management and reporting practices, we reviewed the auditor’s reports on the territories’ compliance with program requirements for each major federal award program. We also reviewed the auditor’s reports on internal control and any identified audit findings. Additionally, we assessed the timeliness of the territories’ audited financial reports. We also interviewed each territory’s independent auditor.

We traveled to Puerto Rico, USVI, and CNMI to conduct our audit work, which we selected based in part on changes in their fiscal conditions since our last update in 2023. We conducted our work with American Samoa and Guam virtually. We conducted this performance audit from April 2024 to June 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Geography and Economic Activity in U.S. Territories

Puerto Rico and USVI are located in the Caribbean near both the mainland U.S. and Central and South America. Guam, CNMI, and American Samoa are located across stretches of the south and west Pacific. All five territories lie in strategic shipping and military locations. The territories comprise approximately 0.1 percent of the U.S. land mass but 6.1 percent of the U.S. territorial waters. As figure 1 shows, Puerto Rico and USVI in the Caribbean Sea are geographically much closer to the U.S. capital in Washington, D.C. than the Pacific territories are.

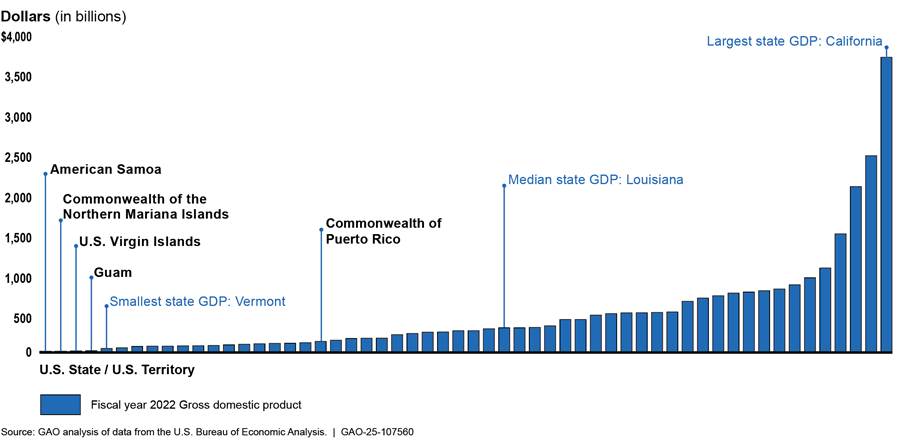

Guam, USVI, CNMI, and American Samoa are small island areas with commensurately

small economies. In 2022, each of these four territories had a GDP level lower

than that of all 50 U.S. states (see fig. 2).

Financial Accountability Responsibilities of Management, Auditors, and Federal Agencies

A key part of financial accountability is transparency and the availability of reliable and timely information to policymakers, oversight entities, and the public. Financial reporting by state and local governments is used for economic, social, and political decisions and in assessing accountability. Reliable and timely financial statements also provide valuable information to government creditors and investors considering investing in municipal bonds.

|

Internal control is a process effected by an entity’s oversight body, management, and other personnel that provides reasonable assurance that the objectives of an entity will be achieved. Source: GAO Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government. | GAO‑25‑107560 |

Territorial governments—similar to states and municipalities—publish annual financial statements. The territories’ management is responsible for preparing these statements and designing, implementing, and maintaining internal controls relevant to the timely preparation and fair presentation of the financial statements. Strong internal controls over financial reporting help ensure financial statements are free from material misstatement, whether due to error or fraud. Management is also responsible for designing, implementing, and maintaining a system of internal controls to reasonably ensure compliance with the territories’ federal award program requirements.

In addition to facilitating timely and reliable financial reporting and compliance with federal award requirements, an effective internal control system helps provide reasonable assurance that the territory’s financial and program objectives will be achieved. It also helps the territorial governments and their managers adapt to shifting environments, evolving demands, changing risks, and new priorities.

|

Questioned Cost is a cost that is questioned by the auditor because (1) there was a violation or possible violation of a statute, regulation, or the terms and conditions of a federal award; (2) the cost is not supported by adequate documentation; or (3) the cost appears unreasonable and does not reflect the actions a prudent person would take in the circumstances. Source: 2 C.F.R. § 200.1. | GAO‑25‑107560 |

Each territory undergoes an annual single audit, which is an audit of the territory’s financial statements and federal awards.[9] Single audit reporting packages are generally required to be submitted nine months after the territories’ fiscal year end.[10] Independent auditors conducting the single audit determine if the financial statements are presented fairly in accordance with U.S. generally accepted accounting principles. Auditors express multiple opinions on the territories’ combined financial statements, one for each opinion unit.[11] Auditors also express an opinion on the territories’ compliance with the applicable program requirements for each major federal award program. If auditors identify compliance issues that have a direct and material effect on a certain major federal award program, they will issue a modified opinion on that specific program.

As part of the single audit, auditors also report any deficiencies they identify in the territories’ internal control over financial reporting (known as financial reporting audit findings) and on any issues related to the management of the territories’ federal award programs (known as federal award audit findings). Among other issues, federal award findings include auditor-identified deficiencies in internal control over the territories’ major federal award programs. When applicable, auditors will also identify and report on questioned costs associated with federal award audit findings. For all audit findings, auditors will provide the territory’s management with recommendations for corrective action to resolve them.

Federal agencies are responsible for providing oversight of the federal awards they provide and use the territories’ single audit results to help ensure federal funds are properly used in accordance with applicable requirements. Among other responsibilities, federal awarding agencies must monitor the timeliness of the territories’ single audits, follow up on the territories’ corrective actions in response to federal award audit findings, and determine if any questioned costs should be sustained (disallowed) or reinstated (allowed). Questioned costs that are disallowed must be returned to the federal government. Federal awarding agencies also have discretion to impose additional award requirements or even withhold funding to territories with a history of unresolved single audit issues.

The Territories Issue Debt as a Financial Management Tool

|

Municipal bonds are debt securities issued by states, counties, and other governmental entities to fund day-to-day obligations and to finance capital projects such as building schools, highways, or sewer systems. Investors buying municipal bonds are, in effect, lending money to the bond issuer in exchange for a promise of regular interest payments, and the return of the original investment—the principal—when the bond matures. Source: Securities and Exchange Commission. | GAO‑25‑107560 |

Similar to U.S. states and municipalities, the territories’ primary governments and component units can issue bonds to borrow money through financial markets. Borrowing is a common financial management tool for governments to bridge the gap between tax receipts and the financial resources required to fund government programs. Borrowing also provides a government with the flexibility to finance long-term investments, such as building schools, roads, and hospitals.

For the purposes of this report, total public debt outstanding refers to the sum of bonds and other debt held by and payable to the public. Marketable debt securities—primarily bonds with long-term maturities—are the main vehicle by which the territories access capital markets. Our definition of public debt outstanding also includes other debt payable, which may be marketable notes issued by territorial governments, nonmarketable intragovernmental notes, notes and loans held by local banks, federal loans, and intragovernmental loans. Liabilities related to retirement benefits, such as pension payments to retirees, are not included in our definition of public debt, but are discussed as part of the risk factors that affect each territory’s ability to repay its public debt.

Generally, debt in itself is not an indicator of financial or economic distress. In fact, the ability to issue bonds and access capital markets is often a sign of sound fiscal and economic fundamentals. In theory, borrowing to finance capital improvements, rebuilding efforts, and infrastructure projects would yield economic activity and growth, helping to offset the cost of borrowing. In contrast, in state and local budgeting, issuing debt to finance general government operations may signal fiscal and economic distress. For example, we previously reported that Puerto Rico’s use of bonds to balance its budgets was a key contributor to its debt and fiscal crisis.[12]

In prior reports in this series we highlighted the risks that arise if a government is not able to borrow through capital markets, either because the cost to borrow is prohibitive, or the issuer is in default.[13] Governments that cannot borrow from capital markets do not have access to a source of financing that can provide flexibility to respond to an unexpected event, such as the COVID-19 pandemic or an extreme weather event.

Shifts in Territories’ Revenues and Expenses Drive Changes in Surpluses and Deficits

Territories’ surpluses and deficits can vary considerably from year to year as expenses and revenues shift. Like state and municipal governments, territorial governments spend money on a variety of services and projects. These include general government expenses as well as services such as education, public housing and welfare, and public safety. Territories collect revenues from individual and business taxes, grants, and other sources.

Federal assistance is a major component of revenue for the territories. Combined, the territories receive billions in federal grants annually for activities such as health care, disaster recovery, and education. As we previously reported, federal agencies allocated more than $32 billion in COVID-19 relief funding to the territories as of May 2023.[14] For American Samoa and CNMI, the total allocations received exceeded their pre-pandemic (fiscal year 2019) GDPs (see table 1).

|

Territory |

Total COVID-19 Relief Allocations (billions of dollars) |

Fiscal Year 2019 Gross Domestic Product (billions of dollars) |

|

Commonwealth of Puerto Rico |

$24.8 |

$105.1 |

|

Guam |

$2.7 |

$6.3 |

|

U.S. Virgin Islands |

$1.5 |

$4.1 |

|

Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands |

$1.9 |

$1.2 |

|

American Samoa |

$1.3 |

$0.6 |

|

Total |

$32.1 |

- |

Source: GAO analysis of appropriations, federal agency allocations, U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis data, and Puerto Rico Planning Board data. | GAO‑25‑107560

Notes: Total allocations include COVID-19 relief funding for which U.S. territory government agencies were the recipients. Allocation data were collected between May 2022 and May 2023, prior to the rescission of unobligated funds in a number of COVID-19 relief programs under the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023 in June 2023. See Pub. L. No. 118-5, div. B, tit. I, 137 Stat. 10, 23–30 (2023). Allocations do not sum to total due to rounding. COVID-19 relief funding awarded directly to local governments is not included.

As federal COVID-19 programs wind down, territorial governments are now readjusting their budgets and, in some cases, face challenges identifying long-term funding sources to replace this temporary assistance. The International Monetary Fund has found that disbursements of emergency spending like these can heighten volatility in revenue and expenditures.[15] As past patterns of spending and revenue may no longer be a good predictor of future cash flows, the increased uncertainty can pose challenges for managing budget execution.

Population Decline, Financial Management Issues, and Other Factors Pose Risks to Territories’ Abilities to Repay Debt

Economic and other factors present risks to territories’ abilities to manage their debt. Fiscal risks refer to responsibilities, programs, and activities that may legally commit or create the expectation for future government spending. Fiscal risks may be explicit in that the government is legally required to fund the commitment, or implicit in that a risk arises not from a legal commitment, but from current policy, past practices, or other factors that may create the expectation of future spending.

We have previously reported on some of the common economic challenges the territories face, which present risks to their ability to manage public debt. These challenges include (1) the location of the islands, which leads to the high cost of energy and imported goods; (2) increasing vulnerability to frequent and severe episodes of extreme weather; (3) undiversified economies based on few industries with limited job opportunities; and (4) outmigration and population loss.[16]

Each of the U.S. territories faces risks from changes in their populations. All five territories experienced population decline between 2010 and 2020, according to the most recent data available from the U.S. Census (see table 2).

|

Territory |

Population in 2020 |

Population change between 2010 and 2020 |

|

Commonwealth of Puerto Rico |

3,285,874 |

12% decrease |

|

Guam |

153,836 |

3% decrease |

|

U.S. Virgin Islands |

87,146 |

18% decrease |

|

Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands |

47,329 |

12% decrease |

|

American Samoa |

49,710 |

10% decrease |

Source: GAO analysis of Census data | GAO‑25‑107560

|

Gross Domestic Product is a comprehensive time-series measure of economic activity for a territory, specifically the value of the goods and services produced within its border. Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. | GAO‑25‑107560 |

These demographic trends pose a challenge as population decline among working-age residents means lower employment tax revenue and economic activity.

The status of a territory’s economy may also present a risk to its ability to successfully manage debt. Economic activity—as measured by GDP—in the territories reflects the structures of their economies, the influx of federal disaster funds and pandemic-related financial assistance, and the severity of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. A territory’s economy affects its fiscal position, and thus its ability to repay debt and access capital markets.

Liabilities for pension benefits represent an explicit fiscal risk. We have previously reported that several territories have faced challenges funding their pension benefits.[17] In addition to pension benefits, governments may also provide retired employees other benefits, such as health care benefits, life and disability insurance, as well as other services. These are referred to as “other postemployment benefits” or OPEB liabilities in the government-wide financial statements.[18] Like most states and municipalities, the territories pay for these benefits on an ongoing basis rather than from a dedicated funded system in which benefits are financed by prior investments in a pension fund. Given that health care costs are increasing at a rate faster than inflation, liabilities for other postemployment benefits could present a significant fiscal risk to the government. Obligations to provide pension and other postemployment benefits can significantly affect a territory’s financial health and may impair its ability to make debt service payments on outstanding bonds and other debt held by and payable to the public.

Financial management and reporting issues also pose risks, as the territories’ independent auditors continue to identify a number of long-standing issues during annual single audits. For several of the territories, this includes poor audit opinions, numerous audit findings, and questioned federal award costs. For USVI and CNMI, the severity of the reported issues raises concerns about the reliability of these territories’ financial statements. Further, some territories have struggled to issue timely financial statements and other required single audit reports. For example, fiscal year 2022 single audit reports for USVI and CNMI are currently delayed by almost 2 years as of June 1, 2025. We discuss these financial management and reporting issues further throughout this report.

Without timely and reliable financial reporting, the territories risk making poor financial decisions, including those pertaining to debt management. The territories also risk losing access to capital markets because there is insufficient information to support credit ratings. Furthermore, as federal funding makes up a large portion of the territories’ revenue, mismanagement of federal awards poses a financial risk for the territories if federal funding is disallowed or restricted.

As previously noted, we are reporting the results of our work on our three objectives separately for each of the five territories. Each of the five territory sections begins with a summary of key issues and data. We then address the results of our work, by objective, for each of the five territories.

Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico Has Restructured Much of its Debt but Electric Utility Debt Remains in Negotiation

As of August 2024, Puerto Rico has restructured $64.7 billion of debt since the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA) was enacted in 2016.[19] The total restructured debt immediately after restructuring was $28.2 billion, and was about $24.1 billion as of March 2025, according to government officials. Since our last update, Puerto Rico has restructured several smaller debts under debt restructuring mechanisms established by PROMESA, but the final major restructuring for the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority (PREPA) is still in process.[20] PREPA’s in-court restructuring began in 2017, when PREPA filed for protections under Title III of PROMESA. In 2022, the Financial Oversight and Management Board for Puerto Rico (FOMB) filed an initial proposed Plan of Adjustment for PREPA.[21]

The primary government of Puerto Rico does not have short term plans to issue debt unrelated to restructuring or refinancing, according to government officials. As of April 2025, the primary government does not have a credit rating. Officials told us that they will not pursue a rating until PREPA’s restructuring is complete, though they have been regularly meeting with the principal rating agencies.

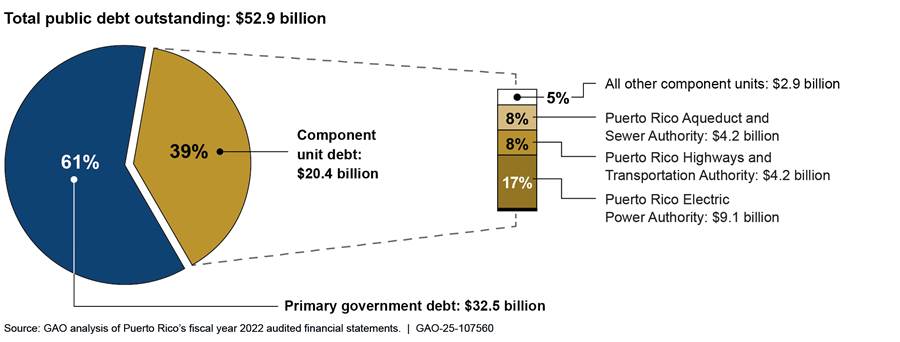

Puerto Rico’s fiscal year 2022 audited financial statements show that as of June 30, 2022, the territory’s total public debt outstanding was about $52.9 billion, or 47 percent of its fiscal year 2022 GDP and 67 percent of its fiscal year 2022 GNP. The total public debt was 11 percent lower in fiscal year 2022 compared to fiscal year 2020. The primary government held more of the territory’s public debt than did the component units. Of the component units, the power utility, PREPA, held the largest share as of fiscal year 2022 (see fig. 3).

Notes: Our calculation of public debt outstanding includes the sum of bonds and other debt payable, which may be marketable notes issued by territorial governments, nonmarketable intragovernmental notes, notes and loans held by local banks, and federal and intragovernmental loans. Fiscal year 2022 is the most recent year for which audited financial data are available. Numbers may not add due to rounding.

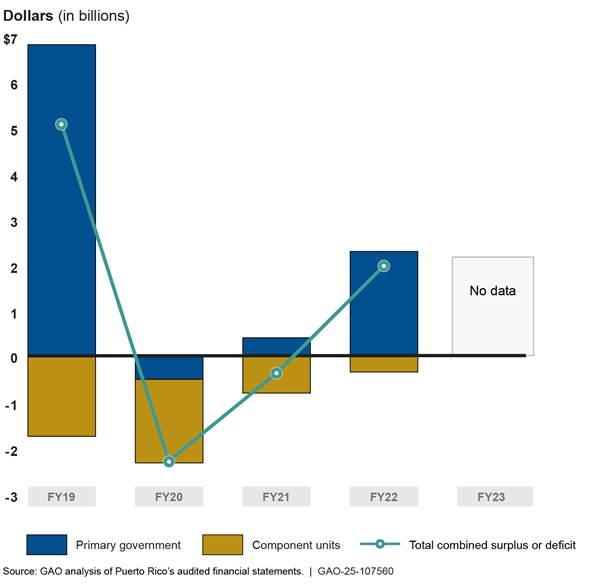

Puerto Rico Reported a Surplus in Fiscal Year 2022, After 2 Years of Deficits

Our analysis of Puerto Rico’s fiscal year 2022 audited financial statements shows a total combined surplus of $1.9 billion in fiscal year 2022. This is a reversal from the prior 2 years, which had deficits of $424.1 million in fiscal year 2021 and $2.3 billion in fiscal year 2020.

· The primary government had a $2.3 billion surplus in fiscal year 2022, a $2.8 billion improvement from its fiscal year 2020 deficit, as increases in revenue outpaced increases in expenses.

· The component units had a deficit of $355.4 million in fiscal year 2022, a $1.5 billion improvement over the deficit in fiscal year 2020, as increases in revenue outpaced increases in expenses. See figure 4.

Notes: FY 2022 is the most recent year for which audited financial

data are available. Puerto Rico’s primary government later restated its FY 2019

and FY 2020 revenues and expenses. As the differences were not material, we

include the original audited revenues and expenses in this report. Special and

extraordinary one-time gains related to the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management,

and Economic Stability Act Title III and VI proceedings and debt forgiveness in

FY 2019 and FY 2022 have been excluded from the revenue figures included in our

report. If these special and extraordinary items were included in Puerto Rico’s

revenues, the primary government would have a $13.1 billion surplus in FY 2019

and a $8.2 billion surplus in FY 2022 and the component units would have a $2.4

billion surplus in FY19 and a $7.7 million deficit in FY 2022

Revenues

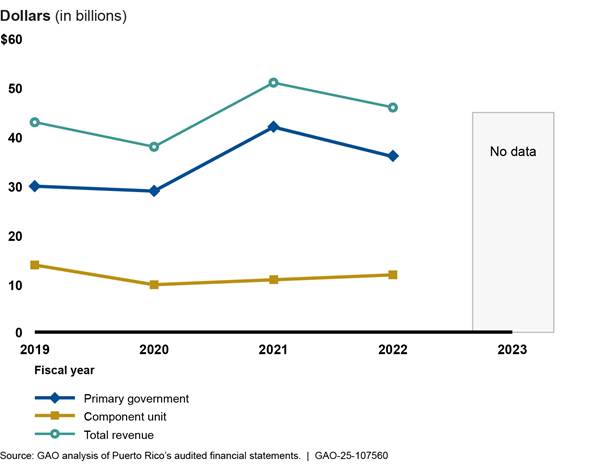

In fiscal year 2022, Puerto Rico’s total combined revenue was $45.8 billion, an increase of 24 percent from fiscal year 2020.

· In fiscal year 2022, Puerto Rico’s primary government revenue was $34.8 billion, a 14 percent decrease from fiscal year 2021 but an increase of about 24 percent compared to fiscal year 2020. Officials attribute the revenue growth between 2020 and 2022 mainly to increased tax revenues and increased operating grants and contributions.

· Revenue from the component units was 23 percent higher in fiscal year 2022 compared to fiscal year 2020, growing from $9.0 billion to $11.1 billion, as shown in figure 5. According to officials, the increase in revenue was mainly driven by higher service charges for electricity as Puerto Rico’s electric utility, PREPA, passed higher fuel costs for electricity on to its customers.

Note: Fiscal year 2022 is the most recent year for which

audited financial data are available. Puerto Rico’s primary government later

restated its fiscal year 2019 and 2020 revenues. As the differences were not

material, we include the original audited revenues in this report. Special and

extraordinary one-time gains related to the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management,

and Economic Stability Act Title III and VI proceedings and debt forgiveness in

fiscal years 2019 and 2022 have been excluded from the revenue figures included

in our report. If these special and extraordinary items were included, primary

government revenues would increase by $6.3 billion in fiscal year 2019 and $5.9

billion in fiscal year 2022 and component unit revenues would increase by $4.2

billion in fiscal year 2019 and $347.7 million in fiscal year 2022

Expenses

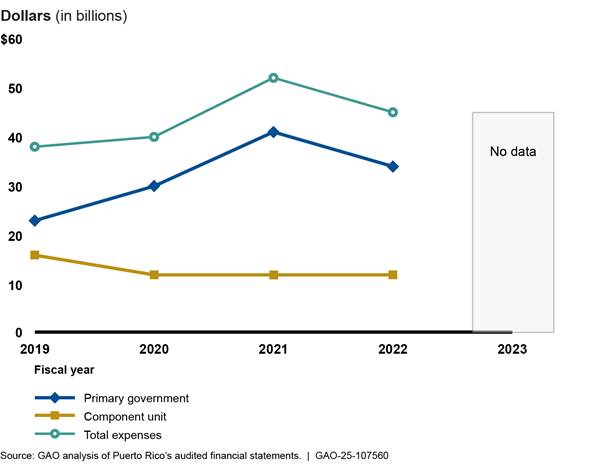

In fiscal year 2022, Puerto Rico’s total combined expenses were $43.9 billion, an 11 percent increase from fiscal year 2020.

· In fiscal year 2022, Puerto Rico’s primary government expenses were $32.5 billion, a 19 percent decrease from fiscal year 2021, but an increase of about 14 percent compared to fiscal year 2020. When comparing fiscal years 2022 and 2020, expenses for public housing and welfare, education, and general government increased the most.

· Expenses for the government’s component units increased 5 percent in fiscal year 2022 compared to fiscal year 2020, growing from $10.8 billion to $11.4 billion. Officials said that this increase is largely due to a rise in the cost of fuel used to generate electricity. At Puerto Rico’s electric utility, PREPA, increases in total expenses outpaced increases in service charge revenues. See figure 6.

Note: Fiscal year 2022 is the most recent year for which audited financial data are available. Puerto Rico’s primary government later restated its fiscal year 2019 and 2020 expenses. As the differences were not material, we include the original audited expenses in this report.

Puerto Rico Continues to Strengthen its Fiscal Position but Electric Utility Status and Other Risks Remain

Puerto Rico’s GDP Has Grown, but Recent Indicators Are Less Positive

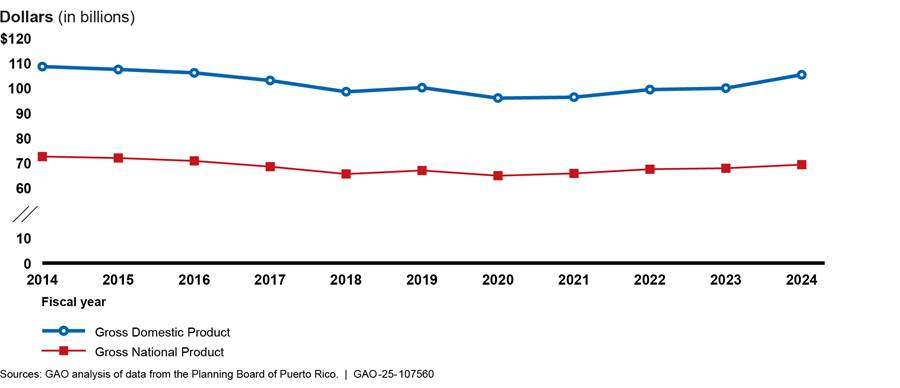

Puerto Rico’s economy grew in fiscal year 2024, continuing three years of modest growth. The territory’s GDP in fiscal year 2024, the most recent data available, was $125.8 billion.[22] Its GNP in that year was $85.6 billion. Between fiscal years 2023 and 2024 Puerto Rico’s real GDP increased 3 percent, and its real GNP increased 2 percent (see fig. 7). Puerto Rico’s annual real GDP growth between fiscal years 2020 and 2024 averaged 0.6 percent, and its annual real GNP growth averaged 0.7 percent. This is a reversal from the prior period (fiscal years 2016 through 2019), during which both the territory’s real GDP and real GNP on average declined about 2 percent annually.

Figure 7: Puerto’s Real Gross Domestic Product and Real Gross National Product in Fiscal Years 2014 Through 2024 (in 2017 dollars)

According to government officials, the influx of federal funds provided to mitigate the effects of Hurricanes Irma and Maria in 2017 and of the COVID-19 pandemic contributed to Puerto Rico’s economic growth. Despite recent growth Puerto Rico’s Economic Activity Index was lower for each month between September 2024 and February 2025 than the same month in the previous year, which may indicate the economy is slowing.[23] As stated previously, the strength of a territory’s economy affects its ability to repay debt and access capital markets.

Puerto Rico Is Implementing Strategies to Strengthen Its Fiscal Position

The government of Puerto Rico and FOMB have worked to strengthen Puerto Rico’s fiscal responsibility and thus its fiscal position. FOMB was established by PROMESA to help the territory achieve fiscal responsibility and access to capital markets. To promote fiscal responsibility, FOMB certifies the fiscal plans and annual budget of the government of Puerto Rico, and several of its major component units.

Officials from FOMB expressed concerns about Puerto Rico’s ability to remain fiscally responsible. To support fiscal responsibility, FOMB reviews new legislation to ensure that new laws are consistent with the fiscal plan.[24] Legislation that incurs expenses or reduces revenue without offsetting measures could be found to be inconsistent with the fiscal plan. For example, in 2024, FOMB determined a bill that would have set a new base salary for school cafeteria employees was inconsistent with the fiscal plan because, among other things, the bill did not include corresponding savings or new revenue to offset the additional cost.[25]

The government adopted a debt management policy in 2022 to help guard against unsustainable borrowing. The policy generally (1) requires that new long-term issuances of tax-supported debt must be for capital improvements or refinancing for savings and (2) specifies that maximum annual tax-supported debt service cost cannot exceed 7.94 percent of the average debt policy revenues from the preceding 2 fiscal years.[26] The government has not issued any tax-supported debt unrelated to restructuring since it adopted the policy, according to government officials.

The creation of the Legislative Assembly Budget Office, or Oficina de Presupuesto de la Asamblea Legislativa (OPAL) also marks an elevated focus on fiscal responsibility. Created in 2023 by the Puerto Rican legislature, OPAL provides estimates of the fiscal effect for legislative proposals. These estimates can help the legislature better understand how proposed measures would affect levels of revenue or expenses. FOMB has encouraged the legislature not to move bills forward until they have been analyzed for fiscal effect by OPAL. However, the use of these estimates in the decision-making process is currently at the discretion of the legislature. OPAL officials told us they produced 185 estimates in fiscal year 2024, including estimates for 11 bills that became law, while 180 laws were enacted without estimates. Government officials told us that it is common for the legislature to pass bills that OPAL warned would have adverse fiscal consequences.

Puerto Rico’s Electric Utility and Other Factors Present Fiscal Risks

Electric Utility

While Puerto Rico has restructured most of its debt, PREPA bondholders and FOMB have not reached an agreement to settle the electric utility’s debt. FOMB filed its proposed plan for PREPA’s restructuring in December 2022. In June 2024 the First Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that PREPA’s bondholders had a lien and non-recourse claim on PREPA’s net revenues, a change that increased the bondholders’ allowable claim from $2.4 billion to $8.5 billion.[27] FOMB moved to reargue this decision, but after granting one rehearing motion the court declined further rehearing in December 2024.

PREPA has been struggling to make its pension payments. PREPA’s pension funding was exhausted in December of 2024, and it no longer had the resources to provide monthly pension benefits to current and former employees. As of May 2025, the primary government has provided PREPA with $375 million in loans, which will cover PREPA’s pension payments through June 2025. In response, FOMB has suggested increasing electricity prices so that PREPA can meet its pension obligations in the long term.

Puerto Rico’s power grid has still not recovered from the damage caused by the 2017 hurricanes, and electricity continues to be relatively expensive. Residents in Puerto Rico lose power more often than residents in any state.[28] Equipment failures caused several major outages in 2024.[29] For example, on December 31, 2024, 90 percent of PREPA customers lost power when an underground power line failed.[30] In January 2025, the average price of electricity was about 29 cents per kilowatt hour, about 80 percent higher than the average price in the mainland United States in the same period, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.[31]

The Puerto Rican government and PREPA have been working on an energy sector transformation since 2018. As part of the transformation, LUMA Energy—a private company—assumed operation of PREPA’s electricity transmission system in 2021. Genera PR—a separate private company—began to operate, maintain, and decommission PREPA’s aging power-generation assets in 2023. Additionally, Puerto Rico’s then Governor-elect established a working group in December 2024 to review Puerto Rico’s energy policy. In January 2025, the Governor created a new position—energy czar—to oversee Puerto Rico’s grid recovery, which includes supervising Genera PR and LUMA Energy. Figure 8 shows a transmission tower in Puerto Rico.

Improving the reliability and cost of Puerto Rico’s electricity is critical to attract and retain business and to support sustained economic growth. Puerto Rico has made efforts to reform its energy sector. Rising energy prices are a risk to balancing spending and revenue in coming years, according to Puerto Rico officials. Officials also told us that energy prices may pose more of a risk to Puerto Rico than to the mainland because the territory is more dependent on fossil fuels to generate electricity.

Climate Risks

Increasingly powerful storms pose a risk, according to Puerto Rico officials. For example, Hurricanes Irma and Maria in September 2017 caused widespread damage to critical infrastructure, livelihoods, and property. Additionally, a 2024 report from Puerto Rico’s Department of Natural and Environmental Resources estimated that Puerto Rico will lose $380 billion in GDP by 2050 if global temperatures increase by 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.[32]

Population Changes

Population decline and an aging population remain concerns. Puerto Rico’s population was 3.2 million in 2024, according to census data. In 2020, Puerto Rico’s population increased, and in subsequent years resumed declining, but at a slower rate than the previous historic trend. Officials from OPAL estimated that if population had remained stable, rather than decreasing between 2008 and 2022, the economy would have grown 1.4 percent rather than contracting 15.8 percent. Meanwhile, Puerto Rico’s population is older on average than the population of the mainland United States. Government officials recognized that future population loss poses a risk to Puerto Rico’s continued economic growth and stability, as fewer working-age residents leads to lower employment tax revenue and diminished economic activity. These officials said they remain optimistic that increased economic growth and infrastructure improvements may retain and attract residents.

Disaster Assistance

Officials told us that Puerto Rico’s recent economic growth has been fueled in part by federal funds provided to rebuild after Hurricanes Maria and Irma and to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. Officials expressed concern that the wind down of these funds could diminish commercial and economic activity, which would lower government revenue.

Pension and Other Postemployment Benefit Liabilities

As stated earlier, pension and other postemployment benefit liabilities represent a fiscal risk. Puerto Rico’s total net pension liability in fiscal year 2022 was $55.1 billion, a 9 percent increase from fiscal year 2020.[33] The territory’s total liability for other postemployment benefits in fiscal year 2022 was $1.9 billion, a 2 percent decrease from fiscal year 2020.

Liability for both pensions and postemployment benefits for the primary government and component units totaled $57.0 billion in fiscal year 2022, representing 50 percent of Puerto Rico’s GDP in fiscal year 2022, and 73 percent of its GNP. Government officials told us they expect these liabilities to decrease in the future due to reductions in benefits that were part of the debt restructuring.

Puerto Rico established a pension trust in 2022 as part of the Commonwealth’s Plan of Adjustment to support future pension payments. The trust will be funded through annual contributions until fiscal year 2031, according to government officials. The payments are calculated using a formula based on Puerto Rico’s annual surpluses and is projected to be fully funded (i.e., the pension fund assets will be equal to or greater than the estimated liability) by fiscal year 2039. The government will be able to withdraw funds to help pay for pensions under certain conditions starting in fiscal year 2032, according to government officials. As of April 2025, Puerto Rico has contributed a total of $3.4 billion to the pension reserve trust, with the most recent payment of $906 million made in November 2024, according to government officials.

Puerto Rico Continues to Have Some Financial Management and Reporting Issues

While Puerto Rico has made some improvement in the timeliness of its audited financial statements, the territory’s continued delays and issues obtaining clean audit opinions present a risk. Several of the departments included in Puerto Rico’s primary government also have recurring audit findings related to financial reporting and federal awards, along with some questioned costs.[34] As stated previously, timely and reliable financial reporting is important to ensure territories can make informed debt management decisions and access capital markets if needed.

Timeliness. Puerto Rico has made some progress in issuing more timely audited financial statements, but the territory’s fiscal year 2021 and 2022 statements were delayed. Both of these financial statements were issued about 22 months after the end of their respective fiscal years.[35] As of June 1, 2025, the territory had not yet issued its fiscal year 2023 or 2024 statements. Puerto Rico officials stated that these delays were due to their inability to obtain timely financial information from PREPA, which the government includes in its government-wide financial statements.

Audit opinions. In Puerto Rico’s last two completed audits, fiscal years 2021 and 2022, the territory received a disclaimer of opinion on its business-type activities.[36] Puerto Rico received this opinion because auditors were unable to obtain sufficient appropriate audit evidence to conclude that certain financial balances and activities in its unemployment insurance fund were free of material misstatement. Of the individual departments we reviewed, all received qualified audit opinions on a significant portion of their major federal award programs, meaning auditors found compliance issues that had a direct and material effect on those programs.

Audit findings. Several of the departments included in Puerto Rico’s primary government have serious audit findings that have remained unresolved for at least 2 years. For example, auditors reported that Puerto Rico’s Department of Labor and Human Resources did not have adequate accounting procedures for the reconciliation and analysis of financial transactions and did not properly supervise and train accounting personnel. Among other risks, this increases the likelihood that this department will not adhere to applicable financial reporting regulations or detect budget variances, errors, or fraud on a timely basis. Additionally, auditors for Puerto Rico’s Department of Education reported that inadequate payroll processing controls prevented it from detecting incorrect or duplicate payments to employees in a timely manner. Auditors also reported that this department had inadequate controls related to equipment and property management, including deficiencies in safeguarding, physical inventory, and records maintenance.

Questioned costs. The total expenditures questioned by an auditor—known as questioned costs—associated with the federal award findings was close to $1 million for the three departments we reviewed. While this is a small amount in the context of the territory’s annual budget, these three departments make up a relatively small portion of Puerto Rico’s primary government. If other departments are experiencing federal award management issues, the territory’s total questioned costs could potentially be much higher.

These findings are important for the following reasons:

· Timely and reliable financial data provide important information for investors, policymakers, oversight bodies, and the public on the financial and economic condition of the territory.

· Robust internal controls are important to support managers as they make financial decisions or adapt to shifting environments, evolving demands, changing risks, and new priorities as they arise.

· Strong controls over compliance help ensure federal award programs meet objectives and are compliant with applicable laws and regulations. Furthermore, they reduce the risk that territories will have to return disallowed costs or be excluded from future federal funding due to noncompliance with federal award program requirements.

Puerto Rico has begun to implement an enterprise resource planning system, which is intended to streamline the government’s financial, supply chain, human capital management, and payroll systems. Puerto Rico’s auditors said they expect full implementation of the system will resolve a significant portion of Puerto Rico’s issues with financial reporting and internal controls. The government began implementing the system in 2022, but the implementation has faced delays. To address delays, the government revised its implementation to prioritize the essential financial functions, focusing on the financial management and supply chain modules.

Guam

As Fiscal Position Improves, Guam Plans to Issue New Debt to Finance Infrastructure Projects

Guam officials told us they plan to issue bonds for infrastructure and capital improvement projects in the near future. For example, they plan to issue bonds for a new high school after they award the construction contract in late June 2025. The primary government and component units issued bonds in fiscal years 2022, 2023, and 2024 to refinance existing debt, reducing its interest payments on outstanding debt.

In January 2024, Moody’s Ratings, a company that provides credit ratings and risk analyses to help investors analyze credit risk, upgraded the government of Guam’s credit rating from a substantial credit risk to a moderate credit risk.[37] According to Moody’s, the new rating reflects significant improvement in the government’s financial position due to federal support and military construction activity. In February 2025, S&P Global Ratings, another company that provides credit ratings, assigned a positive outlook to all ratings of the government of Guam.[38] S&P has ratings for several of Guam’s bonds, all of which are speculative grade.[39]

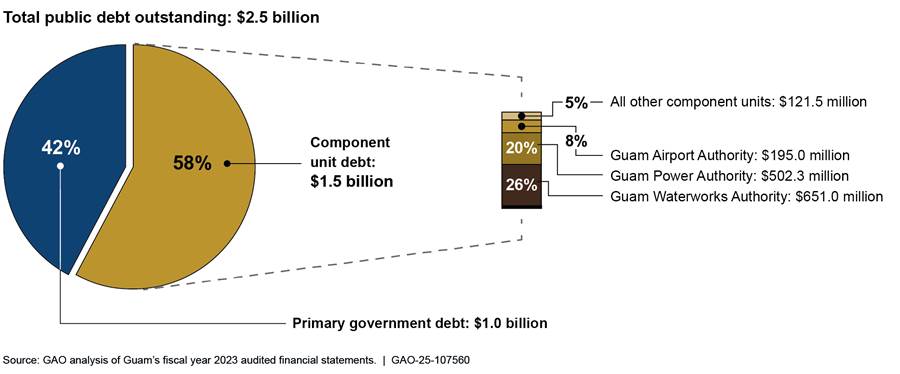

According to our analysis of Guam’s fiscal year 2023 audited financial statements, Guam’s total public debt outstanding was $2.5 billion as of September 30, 2023, a 4 percent decrease from fiscal year 2021. Component units held more of the territory’s public debt than the primary government. The water and electric utilities held the largest shares of component unit debt as of fiscal year 2023 (see fig. 9).[40]

Notes: Our calculation of public debt outstanding includes the sum of bonds and other debt payable, which may be marketable notes issued by territorial governments, nonmarketable intragovernmental notes, notes and loans held by local banks, and federal and intragovernmental loans. Fiscal year 2023 is the most recent year for which audited financial data are available. Numbers may not add to 100 due to rounding.

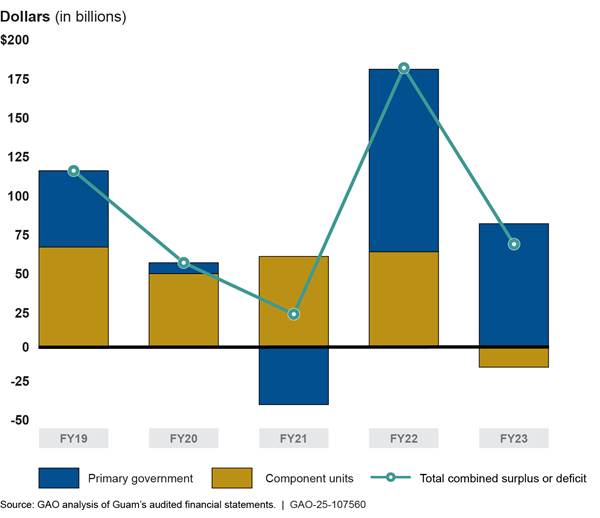

Guam Reported Surpluses in Fiscal Years 2022 and 2023

Our analysis of Guam’s fiscal year 2023 audited financial statements shows a total combined surplus of $66.0 million in fiscal year 2023.

· The primary government had a $78.5 million surplus in fiscal year 2023, a $115.5 million improvement from the fiscal year 2021 deficit, as decreases in expenses outpaced decreases in revenue.

· The component units had a deficit of $12.5 million in fiscal year 2023, a $71.0 million reversal from their fiscal year 2021 surplus, as increases in expenses outpaced increases in revenue, as shown in figure 10.

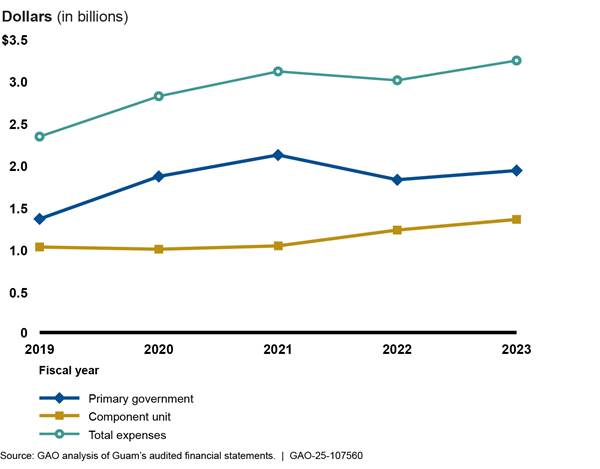

Note: FY 2023 is the most recent year for which audited financial data are available.

Revenues

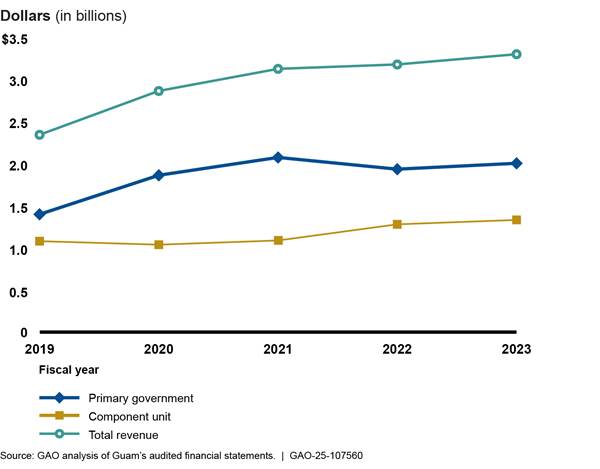

In fiscal year 2023, Guam’s total combined revenue was $3.3 billion, a 6 percent increase from fiscal year 2021.

· In fiscal year 2023, Guam’s primary government revenue was almost $2 billion, a decrease of 3 percent from fiscal year 2021. Guam officials said that this decrease in revenue can be mainly attributed to the end of federal grants related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

· Guam’s component unit revenue was $1.3 billion in fiscal year 2023, an increase of 23 percent from fiscal year 2021. Guam officials said that the increase in revenue was largely due to an increase in the price of fuel used to generate electricity, and that this increase was passed on to electricity customers in the form of service charges. At Guam’s electric utility, Guam Power Authority, increases in service charge revenue slightly outpaced increases in total expenses (see fig. 11).

Note: Fiscal year 2023 is the most recent year for which

audited financial data are available.

Expenses

In fiscal year 2023, Guam’s total combined expenses were $3.2 billion, a 4 percent increase from fiscal year 2021.

· In fiscal year 2023, Guam’s primary government expense was $1.9 billion, a decrease of 9 percent from fiscal year 2021. Guam officials said that this decrease in expenses can be largely attributed to decreased spending in response to reduced COVID-19 pandemic-related federal grants.

· Guam’s component unit expense was $1.3 billion in fiscal year 2023, an increase of 32 percent from fiscal year 2021. Guam officials said that the increase in expenses was mainly due to an increase in the price of fuel used to generate electricity (see fig. 12).

Note: Fiscal year 2023 is the most recent year for which audited financial data are available.

Guam’s Economy Shows Continued Signs of Recovery After COVID-19 Pandemic, but Fiscal Risks Remain

Most Recent Data Show Increase in Guam’s GDP

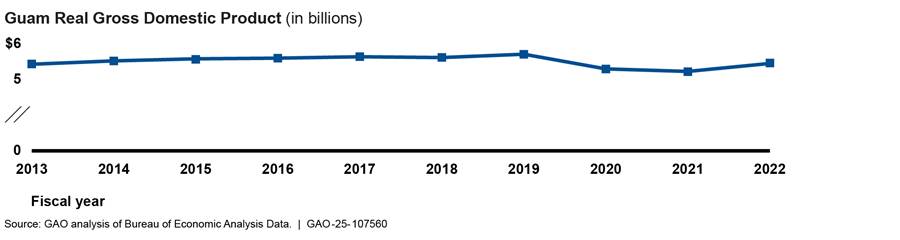

Guam’s economy has continued to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic. Guam’s GDP was $6.7 billion in fiscal year 2022, the most recent year for which data are available.[41] In real terms, this represented economic growth of about 4 percent from the previous year (see fig. 13). Real GDP on average declined 0.6 percent annually between fiscal years 2018 and 2022 and increased 1 percent annually between fiscal years 2013 and 2017. As stated previously, the strength of a territory’s economy affects its ability to repay debt and access capital markets.

Note: The most recent available data are for 2022.

U.S. Military Presence in Guam Has Bolstered the Economy

The U.S. military’s growing presence on the territory provides a stable and increasing source of economic activity. Guam’s location enables it to serve as a strategic hub supporting crucial operations and logistics for U.S. military forces operating in the Indo-Pacific region. Guam hosts three U.S. military bases and, approximately 21,700 military members and their families as of 2020, according to the Department of Defense. According to the Department of Defense, of the amounts Congress appropriated for military construction and family housing for fiscal years 2020 through 2025, the military plans to use a total of $3.9 billion in Guam. This is in addition to the $1.3 billion it used from appropriations for the same purposes for fiscal years 2014 through 2019.[42]

The military’s presence in Guam is expected to expand in coming years. Guam is expecting that the new Marine Corps Base Camp Blaz, which opened in January 2023, will be home to approximately 5,000 Marines (see fig. 14). According to Guam officials, Marines began relocating from Okinawa, Japan, in December 2024.

Recovery of Guam’s Tourism Industry and Other Factors Present Risks

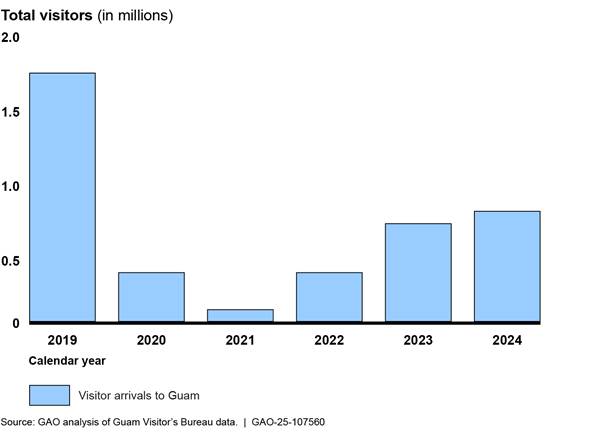

Tourism

Tourism is one of Guam’s primary industries, along with

military-related activities and construction. Due to visitor growth, Guam’s hotel

tax revenue has increased from its pandemic low. Guam collected $29 million in

hotel tax revenues in fiscal year 2023, an increase of 130 percent from a low

of $12 million in fiscal year 2021. However, the fiscal year 2023 hotel tax

revenues were still 36 percent lower than those collected in fiscal year 2019,

prior to the pandemic, reflecting that the tourism industry has not fully

recovered. While tourism remains well below pre-pandemic levels, the government

of Guam’s visitor arrival numbers have continued to increase annually after

reaching a low in 2021, as shown in figure 15.

Economic Risks

Despite its relatively stable GDP, Guam faces several additional risks. In its January 2024 rating action, Moody’s identified several fiscal risks to the territory. These included Guam’s small and concentrated economy and the economy’s heavy reliance on tourism, residents’ low incomes, and what Moody’s considered to be very high long-term government liabilities. A 2019 report created for Guam’s government shows that the island’s infrastructure would be greatly affected by sea-level rise, and that the frequency of strong tropical cyclones will likely increase. Guam officials we spoke with also identified the high cost of living and population loss as fiscal risks. Guam’s population decreased about 4 percent between 2010 and 2020, according to the U.S. Census.

Pension and Other Postemployment Benefit Liabilities

As stated earlier, pension and other postemployment benefit liabilities represent a fiscal risk. Guam’s total net pension liability in fiscal year 2023 was $1.8 billion, a 10 percent increase from fiscal year 2021. Officials said this was partly due to employees joining a new defined benefit plan. Additionally, they stated that there was a loss to the pension plan’s assets, which caused the net liability to increase.

Guam’s total liability for other postemployment benefits, such as health care, in fiscal year 2023 was $2.3 billion, a 9 percent decrease from fiscal year 2021. Officials stated that this was due to a change in the actuarial assumptions used in the plan’s most recent valuations.

Liability for both pensions and postemployment benefits for the primary government and component units totaled $4.1 billion in fiscal year 2023, a 1 percent decrease from fiscal year 2021.[43]

Officials told us that annual contributions to the territory’s pension fund are based on actuarial recommendations. The required contribution rate has recently risen in response to the higher pension liability and is estimated to further increase in the future. Officials expect the pension to be fully funded by 2034 (i.e., the pension fund assets will be equal to or greater than the estimated liability). The government pays other postemployment benefits as they are due.

Guam’s Financial Statements Are Reliable but Some Weaknesses in Internal Control Exist

Guam’s financial statements have consistently been of high quality, according to independent auditors, and the territory has made some progress in addressing its internal control deficiencies. However, the territory has had recent issues with the timeliness of its single audit reports and independent auditors continue to identify significant audit findings and some questioned costs associated with its federal award programs. As stated previously, timely and reliable financial reporting is important to ensure territories can make informed debt management decisions and access capital markets if needed.

Timeliness. Until recently, Guam generally issued its single audit reports on time. However, the territory’s fiscal year 2022 reports were issued about 5 months late, and its fiscal year 2023 reports were issued more than 7 months late. Guam officials stated the delays were partially due to their inability to recruit and retain trained accountants and obtain timely financial information from Guam’s Department of Education. Additionally, officials stated that delays occurred due to a change in independent auditors in fiscal year 2022 and issues with extending the contract with those auditors for fiscal year 2023.

Audit opinions. The territory has consistently received unmodified audit opinions since at least 2010. This means that the independent auditors have determined that the financial information included in Guam’s government-wide financial statements is reliable. However, Guam received a qualified opinion on over half of its major federal award programs in fiscal year 2023, meaning auditors found compliance issues that had a direct and material effect on those programs.

Audit findings. While Guam has made some progress in this area by implementing a new financial management system, it has struggled to remediate several material weaknesses in internal control over financial reporting and compliance identified by its independent auditors.[44] For example, auditors reported that Guam has not performed timely reconciliations, properly recorded certain revenue and expense transactions, completed a comprehensive physical inventory count, consistently provided appropriate supporting documentation, or effectively monitored compliance with all program requirements. These reported issues have resulted in Guam’s noncompliance with a number of federal award program requirements. Additionally, they increase the risk that misstatements and delays may occur in unaudited financial information that is being used to make financial and policy decisions throughout the fiscal year.

Questioned costs. Guam’s questioned costs associated with its federal award findings were $15.5 million in fiscal year 2023, which is 2 percent of the territory’s total federal award expenditures in that year.[45]

These findings are important for the following reasons:

· Timely and reliable financial data provide important information for investors, policymakers, oversight bodies, and the public on the financial and economic condition of the territory.

· Robust internal controls are important to support managers as they make financial decisions or adapt to shifting environments, evolving demands, changing risks, and new priorities as they arise.

· Strong controls over compliance help ensure federal award programs meet objectives and are compliant with applicable laws and regulations. Furthermore, they reduce the risk that territories will have to return disallowed costs or be excluded from future federal funding due to noncompliance with federal award program requirements.

Guam implemented a new financial management system in February 2024, according to officials. The system handles the government of Guam’s financial reporting, as well as other functions such as budget, payroll, human resource, and grants management. Guam’s auditors said they anticipate the system will greatly improve financial reporting. According to officials, the first full year of financial management using the system will be reflected in fiscal year 2025 audited financial statements, with a partial year reflected in the fiscal year 2024 audited financial statements.

U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI)

USVI Issued New Debt in 2025

|

Reliability of U.S. Virgin Islands’ Financial Information Independent auditors have consistently identified issues that raise concerns about the reliability of the U.S. Virgin Islands’ (USVI) financial statements. For example, USVI has struggled to obtain clean audit opinions. We present USVI’s financial statement information from fiscal years 2019 through 2021 because it is the most recent comprehensive data available on the territory’s financial status as of June 1, 2025. However, given the material and pervasive nature of the issues identified, the public debt, revenue, expense, and net pension and other postemployment liability data in our report could be significantly misstated. Source: GAO analysis of the U.S. Virgin Islands’ audited financial statements. | GAO‑25‑107560 |

USVI most recently issued debt in May 2025 in the amount of $150.2 million. The Virgin Islands Transportation and Infrastructure Corporation, a subsidiary of the Virgin Islands Public Finance Authority, issued the debt to finance Federal Highway Administration projects, among other things. Prior to that, the Public Finance Authority issued two series of bonds through a private placement in the amounts of $64.9 million and $18.3 million. These bonds funded a grant for hotel development and related costs. The territory also secured a $100 million line of credit in 2023 to fund disaster-related projects that are reimbursable through federal funding.

USVI officials told us they do not have plans to issue new debt in the near term. The territory has not had an active credit rating since Moody’s withdrew its rating in 2023.[46]

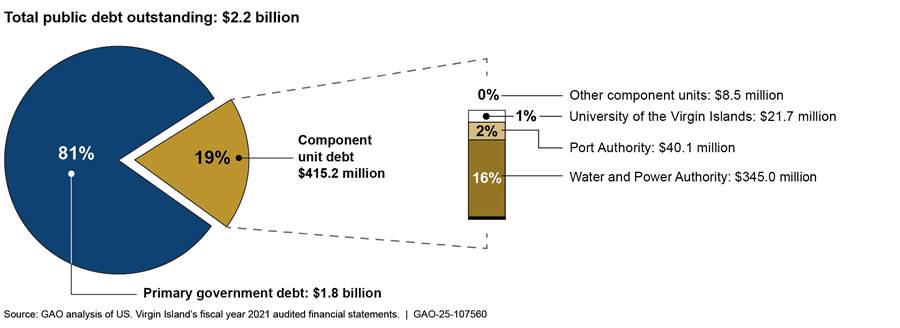

Our analysis of USVI’s fiscal year 2021 audited financial statements—the most recent available—shows that USVI’s total public debt outstanding was more than $2.2 billion, or 50 percent of GDP.[47] This represents a decrease from the territory’s total public debt of about $2.7 billion—66 percent of GDP—in fiscal year 2019.

The primary government is responsible for most of the territory’s public debt. Of the government components, the USVI Water and Power Authority held the largest share, as of fiscal year 2021 (see fig.16).

Figure 16: Composition of the U.S. Virgin Islands’ Public Debt Outstanding, as of September 30, 2021

Note: Our calculation of public debt outstanding includes the sum of bonds and other debt payable, which may be marketable notes issued by territorial governments, nonmarketable intragovernmental notes, notes and loans held by local banks, and federal and intragovernmental loans. Fiscal year 2021 is the most recent year for which audited financial data are available. Numbers may not add due to rounding.

USVI Reported Growing Deficits in Fiscal Years 2020 and 2021

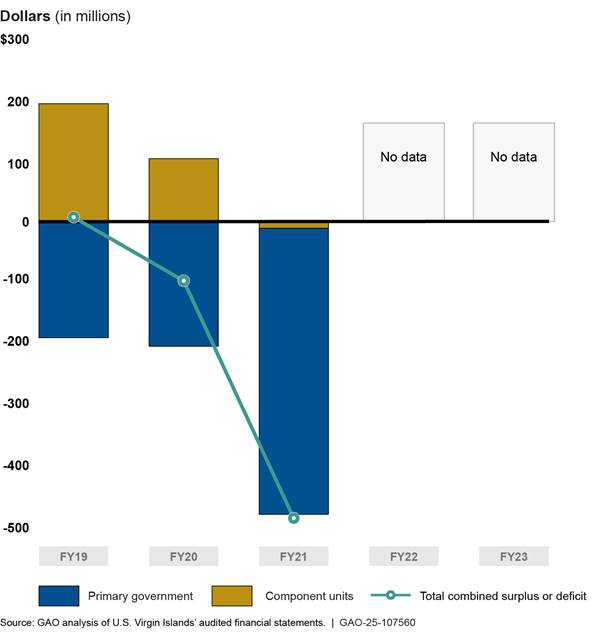

According to its fiscal year 2021 audited financial statements, USVI recorded a deficit of about $484 million that year, an increase from the prior year’s deficit of $97.8 million.[48] In fiscal year 2019, the territory had a surplus of $7.1 million.

USVI’s growing deficits are due to declining fiscal positions of both the primary government and its component units.

· The primary government has had an increasing deficit for the most recent 3 fiscal years for which data are available, as increases in expenses have continued to outpace increases in revenue.

· Component units had surpluses in fiscal years 2019 and 2020 before falling into deficit in fiscal year 2021. When comparing fiscal years 2019 and 2020, decreases in revenue slightly outpaced decreases in expenses. In fiscal year 2021, revenues decreased while expenses increased compared to the prior fiscal year.

Figure 17 shows the territory’s primary government and component units’ surpluses or deficits by fiscal year.

Note: FY 2021 is the most recent year for which audited

financial data are available. USVI’s FY 2019, FY 2020, and FY 2021 revenues and

expenses do not include special items related to gains from pandemic

assistance, debt cancellation, insurance recoveries, and losses on the sale of

assets. If these special items were included in USVI’s revenues and expenses,

primary government deficits would have been $190.5 million in FY 2019, $100.2

million in FY 2020, and $178.8 million in FY 2021 and component unit surpluses

would have been $232.3 million in FY 2019, $109.9 million in FY 2020, and

$155.0 million in FY 2021.

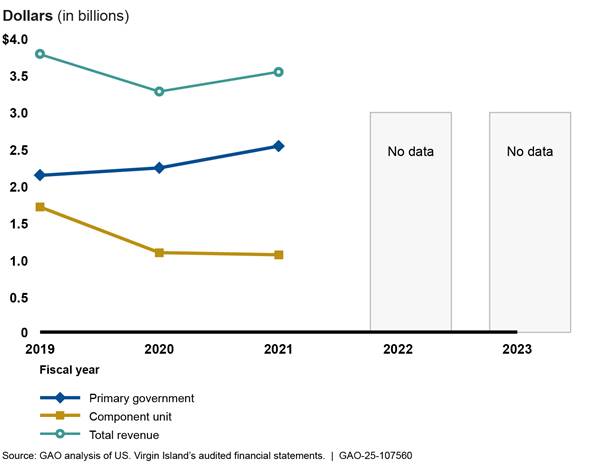

Revenues

Over the most recent years for which data are available, USVI’s total revenue declined slightly from about $3.7 billion in fiscal year 2019 to about $3.5 billion in fiscal year 2021. As shown in figure 18, the primary government’s revenues increased over this period, while component unit revenue decreased and then plateaued. USVI officials told us that the most significant changes in revenue in recent years were due to federal assistance in the wake of the 2017 hurricanes and COVID-19 pandemic. They said that the assistance for both of these events resulted in revenue increases for the territory.

Note: Fiscal year 2021 is the most recent year for which audited financial data are available. USVI’s fiscal year 2019, 2020, and 2021 revenues do not include special items related to gains from pandemic assistance, debt cancellation, and insurance recoveries. If these special items were included, primary government revenues would increase by $5.9 million in fiscal year 2019, $105.6 million in fiscal year 2020, and $294.4 million in fiscal year 2021 and component unit revenues would increase by $34.9 million in fiscal year 2019, $1.9 million in fiscal year 2020, and $165.7 million in fiscal year 2021

· In fiscal year 2021, USVI’s primary government revenue was about $2.5 billion, an increase of almost 20 percent from fiscal year 2019. Officials attributed the increase in the primary government’s revenue to several factors, including an increase in tax revenue that they said was due to increased spending as a result of federal stimulus payments by both USVI residents and tourists who visited USVI.[49]

Despite the increase in primary government revenue, officials at the Bureau of Internal Revenue noted that they are unable to collect all the taxes owed to the government. Collection challenges include businesses closing before taxes can be collected, a lack of qualified bureau staff, and high levels of staff turnover at the bureau. They estimate they collect 50 percent of taxes that are due.

·

USVI’s component revenue was about $1.0 billion in fiscal year

2021, a decrease of almost 40 percent from close to $1.7 billion in fiscal year

2019. According to USVI officials, the decrease was mainly driven by a decline

in the revenue from operating grants and contributions between fiscal years

2019 and 2020. USVI officials explained that the decrease in this category was

mainly due to decreases in grants provided through the Emergency Home Repairs

Program.[50]

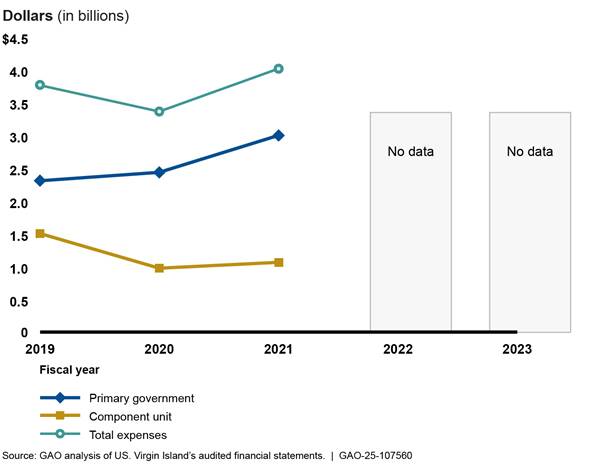

Expenses

Over the most recent years for which data are available, USVI’s total expenses increased slightly from about $3.7 billion in fiscal year 2019 to almost $4.0 billion in fiscal year 2021. As shown in figure 19, the primary government’s expenses increased over this period, while component unit expenses decreased and then increased relatively modestly.

Note: Fiscal year 2021 is the most recent year for which audited financial data are available. USVI’s fiscal year 2019 expenses do not include a one-time special item related to losses on the sale of assets of $6.1 million.

· In fiscal year 2021, USVI’s primary government expenses were about $2.9 billion, an increase of 31 percent from fiscal year 2019. Officials attributed the increase in expenses to costs related to the COVID-19 pandemic and unemployment insurance payments.

· USVI’s component expenses were about $1.0 billion in fiscal year 2021, a decrease of 30 percent from fiscal year 2019. This decrease in expenses for the government’s components was primarily due to a decrease of $406.0 million in expenses between fiscal years 2019 and 2020 for the Emergency Home Repair program.

USVI Tourism Has Recovered, but Electric Utility and Other Risk Factors Pose Challenges

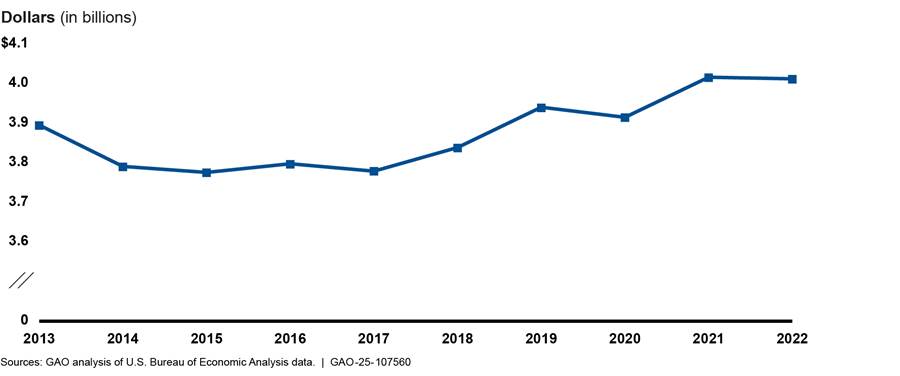

Most Recent GDP Trends Have Been Relatively Stable

In fiscal year 2022, USVI’s GDP was about $4.6 billion.[51] In real terms, this represented a 0.1 percent decrease from the previous year. Over the past 10 years, the territory’s GDP has remained relatively stable. The territory’s real GDP grew by an average of about 1 percent per year between fiscal years 2018 and 2022. Over the prior 5 fiscal years (2013 through 2017) real GDP on average declined by about 2 percent annually. As stated previously, the strength of a territory’s economy affects its ability to repay debt and access capital markets. Figure 20 shows USVI’s real GDP for fiscal years 2013 through 2022.

Figure 20: U.S. Virgin Islands’ Real Gross Domestic Product in Fiscal Years 2013 Through 2022 (in 2012 dollars)

Note: The most recent available data are for 2022.

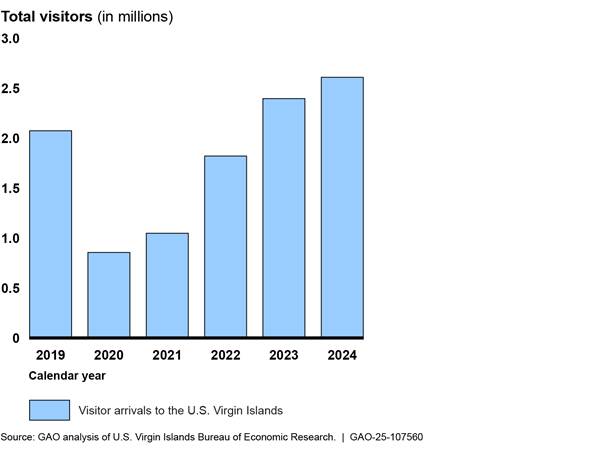

USVI Tourism Has Rebounded but Reliance on a Single Industry Presents Risk

Tourism, the territory’s primary industry, has recovered from a decline during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to data from the Virgin Islands Bureau of Economic Research. USVI’s tourism industry was not as severely affected as that of some of the other U.S. territories, as discussed elsewhere in this report, but the bureau’s data show the number of visitors to the territory declined by over half between 2019 and 2020. As shown in figure 21, by 2023 and 2024 government-calculated visitor numbers exceeded pre-pandemic levels.

Although the tourism industry is currently doing well, the territory’s

dependence on a single industry poses a risk to its economy. By relying so

heavily on tourism, USVI is vulnerable to events that affect the industry.

Territory officials are working on initiatives to diversify its economy, but doing so remains a challenge. For example, officials said they are working with the Environmental Protection Agency to address issues that led to the closure of the territory’s Limetree Bay oil refinery in 2021. The refinery had been one of the territory’s largest employers, and officials estimated that reopening it would add 1,000 jobs to the territory’s economy.

USVI’s Electric Utility and Other Factors Present Risks

Electric Utility

Electricity in USVI is both expensive and unreliable, which creates challenges for residents and can inhibit economic development. Specifically:

· The cost of electricity is USVI is high, and officials said that metering and billing can be inconsistent. The average price of electricity paid by USVI residents was about 42 cents per kilowatt hour at the end of 2023, almost three times higher than the U.S. national average. Additionally, officials from the territory’s electric and water utility—the Water and Power Authority (WAPA)—said they have had problems with its electricity metering and billing systems that lead to unpredictable costs for consumers and unpredictable revenues for the utility.

· Electric service is not consistent and the territory experiences frequent outages due in part to aging and poorly maintained infrastructure. A January 2025 assessment of WAPA’s current status estimated the cost of the utility’s deferred maintenance to be approximately $33 million.[52] The assessment noted that the delay in proper and timely maintenance is one of the primary contributors to the territory’s rolling blackouts.

WAPA is also liable for a significant amount of debt. As of December 2024, the utility’s debt was approximately $238 million.

A significant contributor to WAPA’s financial problems is electricity rates that are not sufficient to cover its costs. Officials we interviewed said that expenses exceed revenue by about $6 million per month. An unaudited notice of WAPA’s financial status from 2024 acknowledged the utility’s substantial operating deficit, but stated that it is not feasible to raise rates because doing so would likely reduce demand. Additionally, the utility has had issues with unpaid bills belonging to large customers, including components of the territory’s government.[53]

WAPA’s ongoing deficits affect its ability to make critical payments, including to fuel suppliers. Its independent auditor has highlighted growing deficits as a risk to WAPA’s ability to pay its debt, fund pensions and other postemployment benefits, and access capital markets in the future.

WAPA officials told us that the utility has strategic initiatives focused on increasing operational stability and lowering costs that they said aim to prevent default on its debt. Additionally, the January 2025 assessment noted that WAPA management has initiated a debt consolidation process and is working to refinance its debt.

Like the rest of the USVI government, WAPA has been delayed in issuing audited financial statements. Both Fitch and Moody’s withdrew their ratings for WAPA in 2023 due to lack of information.

Climate Risks

USVI is also vulnerable to climate risks, though the territory has plans and projects underway aimed at mitigating these risks. According to the territory’s long-term economic strategy, potential effects of sea level rise include coral reef loss, water shortages, and public health problems.[54]

While the cost of the damage from Hurricanes Irma and Maria in 2017 was close to $11 billion, USVI anticipates receiving about $20 billion in federal funding to aid in rebuilding. Officials told us that the funds will support projects over the next 10 to 15 years to rebuild damaged infrastructure and improve climate resilience, among other things. They said they expect the projects to also have a positive effect on the territory’s economy and revenues.

Population Changes