FINANCIAL LITERACY AND SMALL BUSINESS LENDING

Resources Available to Military-Affiliated People

Report to Congressional Requestors

United States Government Accountability Office

financial literacy and small business lending

A report to congressional requesters.

For more information, contact: Courtney LaFountain at lafountainc@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

Military-affiliated people—including active-duty service members, reservists, transitioning service members, veterans, and military and veteran spouses—may face challenges building credit and accessing capital to fund their small businesses. For example, veterans who relocate to a new area after military service can have difficulty establishing credit and developing business relationships. Officials told us military-affiliated people may also face limited access to mentors and professional networks that can help their businesses.

Military-affiliated people can access financial literacy programs and resources through federal agencies including the Department of Defense (DOD), the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), and the Small Business Administration (SBA). These resources provide help with managing personal or business finances, and tips for avoiding fraud and scams.

Military-affiliated people can access capital for small businesses through various private funding sources and federal lending programs. Private sources include self-funding, investors, and business loans. However, according to self-reported responses in the 2024 Small Business Credit Survey, veteran business owners reported facing challenges obtaining financing from large banks, such as high interest rates and difficult application processes. Federal lending options include SBA’s 7(a) program and Department of Agriculture loans for agricultural businesses. SBA lending to veteran-owned businesses generally increased from fiscal year 2019 through fiscal year 2024.

Federal agencies raise awareness of financial literacy and lending programs for military-affiliated people through in-person and virtual presentations, networking events, and the use of social media and websites. For example, SBA’s Office of Veterans Business Development conducted more than 100 presentations annually in fiscal years 2023 and 2024. Agencies such as SBA and DOD have online tools, including program-specific webpages, to improve access to financial education and loan information.

Why GAO Did This Study

Military-affiliated people play a vital role in the nation’s economy, including through veteran-owned businesses. According to the Census Bureau’s 2023 Annual Business Survey, veteran-owned businesses had an estimated $884.5 billion in receipts, 3.2 million employees, and $179.7 billion in annual payroll in 2022.

GAO was asked to review financial literacy and lending resources for military-affiliated people. This report examines (1) challenges military-affiliated people may face in building credit or accessing capital to fund their small businesses, (2) federal financial literacy resources available to them, (3) sources of capital available to them, and (4) agency efforts to raise awareness among this population about financial literacy and lending programs.

GAO interviewed or received written comments from nine agencies, including SBA, VA, and DOD, selected based on prior work, or because they serve the military community. GAO analyzed participation and usage data for financial literacy programs for fiscal years 2019–2023. GAO reviewed national small business survey data from the Census Bureau for 2023 and the Federal Reserve Banks for 2024, the most recent available. GAO also reviewed small business lending data from SBA and Department of Agriculture for 2019–2024, the most recent available. In addition, GAO interviewed or received written comments from representatives of four nonprofit organizations and five financial services firms, selected for their work with military-affiliated people and their businesses.

Abbreviations

CFPB Consumer Financial Protection Bureau

DOD Department of Defense

SBA Small Business Administration

USDA U.S. Department of Agriculture

VA Department of Veterans Affairs

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

September 10, 2025

The Honorable Joni K. Ernst

Chair

Committee on Small Business and Entrepreneurship

United States Senate

The Honorable Jeanne Shaheen

United States Senate

Small businesses owned by active-duty service members, reservists, those transitioning from service, veterans, and military and veteran spouses—collectively referred to as military-affiliated people—are an important part of the nation’s economy. In 2022, veteran-owned businesses generated an estimated $884.5 billion in receipts and employed roughly 3.2 million people, according to a Census Bureau survey.[1] However, military-affiliated people may face challenges in building credit and accessing capital, which can negatively affect their ability to start a small business. Research suggests that veterans have a harder time establishing credit and developing business relationships, particularly after relocating to a new area after military service.[2]

The federal government supports military-affiliated people in building credit and starting, growing, or expanding businesses through a variety of resources, including financial literacy and lending programs. Agencies including the Department of Defense (DOD), Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), and Small Business Administration (SBA) offer counseling to help military-affiliated people make informed financial decisions.

You asked us to review federal efforts to assist military-affiliated people in accessing capital and provide them with financial literacy education. This report examines (1) any challenges that military-affiliated people may face in building credit or accessing capital for their small businesses, (2) federal financial literacy resources available to military-affiliated people, (3) sources of capital available to military-affiliated people, and (4) agency efforts to raise their awareness about financial literacy and lending programs.

For this report, we focused on federal financial literacy resources and lending programs available to, or specifically designed for, military-affiliated people at nine agencies: SBA, DOD, VA, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Federal Trade Commission, National Credit Union Administration, and Securities and Exchange Commission. We selected SBA based on our prior work on veteran lending.[3] We selected the other agencies based on our prior work on financial literacy programs, based on interviews with other agencies in our scope, or because their mission includes services for military-affiliated people.[4]

For the first objective, we interviewed or received written comments from representatives of four nonprofit organizations that support military-affiliated small business owners, as well as five financial services firms or associations with initiatives targeting this population. We identified these organizations from our prior work, our interviews, or because they serve the military community. The views expressed by those we interviewed cannot be generalized to all such entities. For more information on our scope and methodology, see appendix I.

For the second objective, we reviewed our prior relevant work on federal financial literacy programs.[5] We also conducted interviews or received written responses from representatives of the nine agencies we selected for information on their financial literacy programs, including participant data from 2019 through 2023. Appendix II provides more information about federal financial literacy programs.

For the third objective, we reviewed SBA’s website and the Federal Reserve Banks’ Small Business Credit Survey questionnaire and conducted interviews to identify private sources of capital. We analyzed data from the Federal Reserve’s 2022 Survey of Consumer Finances to examine how small business owners fund their businesses. We also used the Small Business Credit Survey to assess veteran-owned business’ challenges with obtaining financing and the proportion of financing that veterans and non-veterans received.

We analyzed SBA data on loans made to veteran-owned small businesses through four SBA lending programs (7(a), 504, Microloan, and Military Reservist Economic Injury Disaster Loan) for fiscal years 2019 through 2024.[6] We also analyzed USDA data on five Farm Service Agency programs and five Rural Development programs for fiscal years 2019 through 2024. We reviewed documentation related to these data and found the data to be sufficiently reliable for describing trends in program lending to such businesses in this period. We also interviewed SBA and USDA officials about the data. Appendixes III and IV provide more information about SBA and USDA lending programs.

For the fourth objective, we interviewed or received written comments from representatives of the nine agencies in our scope and reviewed program websites to determine how they target military-affiliated people.

We conducted this performance audit from May 2024 to September 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

The term financial literacy generally refers to the ability to make informed decisions and take effective actions regarding money. The federal government supports financial literacy through dozens of programs and resources. These efforts are coordinated by the multiagency Financial Literacy and Education Commission, which includes a working group focused specifically on financial literacy resources for members of the U.S. military.[7] DOD is the lead agency for this working group.[8]

In addition to financial education, the federal government also provides access to capital through targeted small business lending programs. SBA helps small business owners and entrepreneurs start, build, and grow businesses through several programs, including 7(a), 504, and Microloan (see table 1).[9] The SBA Express loan—a 7(a) subprogram—offers a fee waiver to applicants who are veterans or veteran spouses.[10] In addition, SBA offers Military Reservist Economic Injury Disaster Loans which help sustain businesses adversely that are adversely affected when an employee is called up for active duty. These programs help provide financing to small businesses—including those owned by military-affiliated people—that may not otherwise qualify for loans on reasonable terms and conditions.

|

Program |

Maximum amount |

Loan type |

Use of funds |

Example requirements |

|

7(a) SBA Express |

$5 million $500,000 |

Loan guarantee Same as 7(a) |

Provides loans for working capital and other sound business purposes, including acquiring, refinancing, or improving real estate and purchasing and installing machinery and equipment. Same as 7(a)a |

A business must be an operating, for-profit small firm (according to SBA’s size standards) located in the U.S. that can demonstrate a need for the desired credit. It must also be unable to obtain the desired credit at reasonable terms from nongovernment sources without SBA assistance. Same as 7(a) |

|

504 |

$5 millionb |

Loan guarantee |

Provides long-term, fixed-rate financing to new or growing small businesses for fixed assets such as land, buildings, or machinery. |

Small businesses may apply for 504 financing through a Certified Development Company serving the project area in which the project is located. Applicants must be unable to obtain the desired credit on reasonable terms from nongovernment sources without SBA assistance. |

|

Microloan |

$50,000 |

Loan guarantee or direct |

Provides loans to use as working capital and to acquire materials, supplies, furniture, fixtures, and equipment. |

Participating lenders must be private nonprofit entities or quasi-governmental economic development entities with at least one year of experience making microloans to small businesses and one year providing technical assistance to its borrowers. |

|

Military Reservist Economic Injury Disaster Loan |

$2 million |

Direct |

Provides working capital assistance to small businesses that experience, or will experience, financial difficulties as a result of an essential employee being called up for active duty. |

The business must have an essential employee who is a military reservist or member of the National Guard called to active duty. |

Source: GAO analysis of Small Business Administration (SBA) documentation. | GAO‑25‑107561

aSBA Express—a 7(a) subprogram—loan borrowers may also use loan proceeds as revolving lines of credit but cannot use working capital to refinance existing debt.

bThere is a limit of $5.5 million for certain projects. See 13 CFR 120.931(c).

SBA is statutorily required to give special consideration to veterans in carrying out its lending programs.[11] In a December 2023 report, we recommended that SBA develop and implement policies and procedures to ensure SBA gives special consideration to veterans in its lending programs.[12] SBA described such policies and procedures in a revised standard operating procedure for its Lender and Development Company Loan program, effective June 1, 2025. Specifically, the revised standard operating procedure states that SBA will (1) waive the upfront fee for SBA Express Loans to businesses owned and controlled by veterans; (2) prioritize processing applications from businesses owned by veterans for loans processed by SBA under nondelegated procedures; and (3) encourage participating lenders to give special consideration to veterans during application processing for loans processed under delegated procedures. SBA stated that, since implementing the procedures, the agency has processed applications under nondelegated procedures faster for veteran-owned businesses than for non-veteran-owned businesses.

USDA also provides loans to small business owners in agriculture and agribusiness, including military-affiliated people, through its Farm Service Agency and Rural Development programs.[13] These programs help expand access to credit and capital in rural areas where capital options may be limited (see tables 2 and 3).

|

Program |

Maximum loan amount |

Loan type |

Use of funds |

Example requirements |

|

Direct Farm Ownership |

$600,000 |

Direct |

Provides loans to purchase a farm, grow an existing farm, construct new farm buildings or improve structures, pay closing costs, or promote soil and water conservation and protection. |

The operation must be a family farm that is unable to obtain commercial credit for the farm or project. To be eligible, applicants must have 3 years of farming experience, or other relevant training and education. Funds must be used for agricultural operations that commercially produce food or fiber agricultural commodities. |

|

Direct Farm Operating |

$400,000 |

Direct |

Provide loans for normal operating expenses, machinery and equipment, minor real estate repairs or improvements, and refinancing certain debt. |

The operation must be a family farm that is unable to obtain commercial credit for the farm or project. To be eligible, applicants must have 1 year of farming experience, or other relevant training and education. Funds must be used for agricultural operations that commercially produce food or fiber agricultural commodities. |

|

Direct Emergency Farm |

$500,000 |

Direct |

Provides loans to restore or replace essential property; pay all or part of production costs associated with the disaster year; pay essential family living expenses; reorganize the farming operation; or refinance certain debts. |

In addition to requirements for Farm Ownership and Operating Loans, the county or counties where the farm is located must be declared a disaster area by the President or designated by the Secretary of Agriculture. |

|

Guaranteed Farm Ownership |

$2,251,000a The maximum loan amount is adjusted annually for inflation |

Loan guarantee |

Provides loans to purchase a farm, enlarge an existing farm, construct new farm buildings and/or improve structures, pay closing costs, and promote soil and water conservation and protection. |

The operation must be a family farm that is unable to obtain commercial credit for the farm or project without a guarantee. Funds must be used for agricultural operations that commercially produce food or fiber agricultural commodities |

|

Guaranteed Farm Operating |

$2,251,000a The maximum loan amount is adjusted annually for inflation |

Loan guarantee |

Provides loans for normal operating expenses, machinery and equipment, minor real estate repairs or improvements, and refinancing debt. |

The operation must be a family farm that is unable to obtain commercial credit for the farm or project without a guarantee. Funds must be used for agricultural operations that commercially produce food or fiber agricultural commodities. |

Source: GAO analysis of U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) documentation. | GAO‑25‑107561

aMaximum loan amount for fiscal year 2025.

|

Program |

Maximum loan amount |

Loan type |

Use of funds |

Example requirements |

|

Business & Industry Loan Guarantee |

Generally, $25 million Up to $40 million for certain rural cooperatives with approval from the Secretary of Agriculture |

Loan guarantee |

Provides loans for business development, growth, modernization, conversion, or repair; buying and developing land, buildings, or associated infrastructure for commercial or industrial use; buying and installing machinery, equipment, supplies, or inventory; refinancing debt to improve cash flow and create jobs; acquiring businesses when the loan will create or save jobs. |

Businesses with facilities located in rural areas that save or create jobs. Eligible entities include partnerships, individuals, cooperatives, for-profit and nonprofit entities, corporations, including publicly traded companies, tribal groups, or local governments. |

|

Rural Energy for America Program Renewable Energy Systems & Energy Efficiency Improvement Guaranteed Loans |

$25 million maximum total amount |

Loan guarantee |

Provides loans for purchasing and installing renewable energy systems, such as small and large wind generation, small and large solar generation, and hydropower below 30 megawatts. |

Projects must be for purchasing a new, exiting, or refurbished renewable energy system, or retrofitting an existing renewable energy system. The system must use commercially available technology. |

|

Intermediary Relending Program |

The lesser of $400,000 or 50 percent of the originally approved loan amount to an intermediarya |

Direct |

Provides loans for purposes that include business and industrial acquisitions when the loan will keep the business from closing, prevent the loss of employment opportunities, or provide expanded job opportunities; purchase and development of land; and debt refinancing. |

Applicants must not owe any delinquent debt to the federal government, must be unable to obtain affordable commercial financing for the project elsewhere, and must hold no legal or financial interest or influence in the work of the intermediary lender.b |

|

Rural Economic Development Loan and Grant Programs |

$1 millionc |

Direct |

Provides loans for business incubators; community development assistance to nonprofits and public bodies (especially for job creation); education and training facilities for rural economic development; medical care facilities and equipment; startup costs including real estate, equipment, or working capital; business expansion; and technical assistance. |

Projects must be in rural areas or towns with a population of 50,000 or fewer residents. |

|

Rural Microentrepreneur Assistance Program |

$50,000 |

Direct |

Provides loans for qualified business activities and expenses including working capital, debt refinancing, equipment and supply purchases, and real estate improvements. |

Projects must be in rural areas outside a city or town with a population of 50,000 or fewer residents. |

Source: GAO analysis of U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) data. | GAO‑25‑107561

aSee 7 C.F.R. §4274.331.

bIntermediary lenders are local lenders that re-lend to businesses to improve economic conditions and create jobs in rural communities. They include nonprofits and cooperatives, federally recognized tribes, and public agencies.

cThis is the 2025 maximum. The maximum loan amount is published yearly. See 7 CFR 4280.38.

Certain features of military life may affect entrepreneurship after service. For example, a military deployment involves relocating a service member from their home station to a location outside the continental U.S. and its territories. Deployments are not limited to combat and may support missions such as humanitarian aid, evacuation of U.S. citizens, restoration of peace, or increased security. They can last from 90 days to 15 months. In addition, service members may make a permanent change of station, which involves longer-term relocations—generally 2 to 4 years—either within or outside the continental U.S.

Frequent Moves, Limited Networks, and Other Factors Can Hinder Military-Affiliated People’s Access to Credit and Capital

Several factors affect military-affiliated people in building credit or accessing capital to fund their small businesses, according to representatives of two nonprofit organizations and officials from a financial services firm we interviewed, as well as reports we reviewed.

Active-Duty Service Members

Active-duty service members may face financial challenges that affect their ability to pursue entrepreneurship after leaving the military. A 2022 DOD survey estimated that 40 percent of active-duty service members reported some financial difficulty or described their financial condition as not comfortable. The survey also estimated that 13 percent reported borrowing money from family or friends to pay bills, and 9 percent reported failing to make monthly or minimum credit card payments.[14] A representative of a nonprofit organization noted that service members’ lack of knowledge of the business world could be a barrier to successful business ownership. In addition, a financial services firm we interviewed said that frequent moves due to deployment can hinder the development of networks with lenders or investors.

Transitioning Service Members

A representative of a nonprofit organization we interviewed noted that transitioning from active duty can be a challenging time that affects service members’ employment, financial stability, and family and social relationships. A 2020 CFPB report found that selected active-duty service members experienced declining credit scores and increased delinquencies and defaults following their separation from service.[15] In addition, we reported in 2022 that transitioning service members may experience challenges transferring their military skills and credentials—such as certifications and licenses—to civilian jobs.[16]

DOD makes efforts to assist service members with their transition to civilian life, including assistance with planning to start a business. Prior to separating from service, transitioning service members participate in the mandatory Transition Assistance Program, which provides career readiness services and information on veterans’ benefits.[17] The program is designed to help participants access veterans’ benefits and develop post-transition plans and goals, including starting a business.[18]

Veterans

As we have reported previously, research suggests that veterans have a harder time than nonveterans in establishing credit and developing business relationships, particularly those who relocate to a new area after military service.[19] An official from a financial services firm we interviewed noted that, due to their military background, veterans often lack access to business networks.

Veterans may also face unique challenges in accessing capital for their businesses. For example, lenders may be unfamiliar with the skill and experience gained during military service or the specific business type for which they seek financing.[20] Veterans may also lack personal startup funds, capital, or demonstrable business income, as we have previously reported.[21]

Reservists

Reservists who own small businesses may experience challenges resulting from deployment. For example, reservists whose businesses depend on their specialized skills—such as doctors and dentists—can experience disruptions when called to active duty, according to representatives of a financial services firm and a nonprofit organization we interviewed. In addition, frequent relocations may require adapting to new regulations, certifications, and tax requirements with each move into a different state or local jurisdiction, according to the nonprofit representative. The same nonprofit representative also noted that these disruptions can make it difficult for reservists to establish stable local networks, limiting social and human capital needed for business success.

Reservists may also face additional challenges that are not well understood due to gaps in data collection. For example, while DOD includes information about reservists in its annual Status of Forces survey, SBA and USDA loan data do not report information on applicants who are reservists. Further, national surveys of business owners, such as Census Bureau’s Annual Business Survey and the Federal Reserve Banks’ Small Business Credit Survey, do not collect information on whether a respondent is a reservist.

Military Spouses

As with other military-affiliated people, deployment or a permanent change of station can present challenges for military spouses. These challenges include irregular income, finding mentorship opportunities, and finding quality childcare, according to one nonprofit organization that we interviewed. Additionally, we reported in 2021 that varying occupational licensing requirements across state lines—in fields such as cosmetology and medicine—can hinder military spouses’ ability to find and maintain employment with each move.[22]

A representative of a nonprofit organization noted that while SBA’s lending programs are well-known in the military community, some military spouses may hesitate to apply due to uncertainty about their eligibility. This hesitancy may stem from frequent relocations, limited income or credit history, or lack of collateral.

DOD reports information about military spouses in its Active-Duty Spouse survey. SBA collects information on loan applications about their status as a spouse of a veteran but does not report on this information separately. As with reservists, USDA does not report information from loan applications about a person’s status as a military spouse. Further, national surveys of business owners, such as Census Bureau’s Annual Business Survey and the Federal Reserve Banks’ Small Business Credit Survey, do not collect information on whether a respondent is a military spouse.

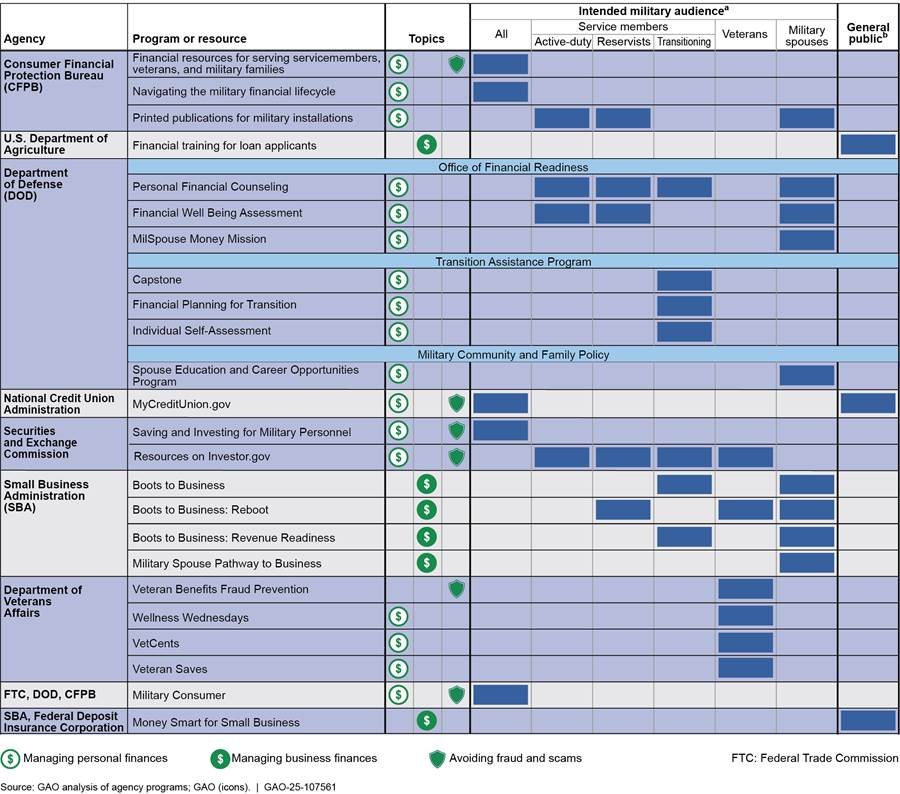

Federal Agencies Offer Resources to Help Military-Affiliated People with Financial Decision-Making

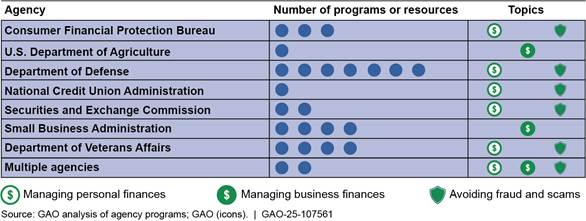

Among the nine federal agencies in our review, we identified 24 programs or resources aimed at helping military-affiliated people or small business owners with their financial decision-making (see fig. 1). These programs and resources provide help with managing personal or businesses finances, as well as tips for avoiding fraud and scams. DOD and SBA financial literacy education programs reached an estimated 2.7 million people in 2023.[23] See appendix II for more information about these programs.

Figure 1: Federal Financial Literacy Programs and Resources Targeted to Military-Affiliated People or Small Business Owners

aThe intended audience is the individual or group whose financial literacy the program or resource intends to improve. For example, if a resource is designed for a financial literacy educator to improve the financial literacy of veterans, we would consider the intended audience to be veterans.

bSome programs or resources are intended for the general public or other groups but also have information that is specific to the needs of military-affiliated people.

DOD is required to provide financial literacy training to members of the armed forces.[24] Specifically, DOD must provide training to service members at different points in their career, including upon entry into service, upon arrival at their first duty station, and at major life events such a marriage, divorce, or the birth of a first child. DOD and the military services (such as the Coast Guard) have several programs intended to address this requirement, including the following:

· The Personal Financial Counseling Program provides in-person, virtual, and telephone counseling, information and referral, as well as briefings and financial literacy training and education. The program serves active-duty service members, reservists, spouses, and other eligible beneficiaries. According to DOD, the Office of Financial Readiness provided counseling to over 2 million participants in 2023.

· MilSpouse Money Mission is a financial education website designed for military spouses to help them enhance their financial knowledge and skills. According to DOD, over 100,000 users accessed this website in 2023.

· The Transition Assistance Program includes a financial planning component to help ensure that departing service members have a viable plan for transitioning to civilian life, including a post-separation financial plan.

Additionally, SBA maintains a nationwide network of resource partners that provide counseling, training, mentoring, and funding guidance to small business owners, including those who are military-affiliated. This network includes Veterans Business Outreach Centers, which offer resources to veterans and other eligible parties interested in starting or growing a small business.[25] These centers are operated by eligible organizations that include institutions of higher education, nonprofits, and local and state government agencies.[26] They offer entrepreneurial training through three programs that provide participants with an introductory understanding of business ownership and guidance on accessing financing:

· Boots to Business courses are hosted by military installations worldwide and targeted to transitioning service members and military spouses.

· Boots to Business Reboot courses are offered in local communities or virtually for participants who cannot access military installations. The program targets veterans of all eras, National Guard and reserve members, and military spouses.

· Military Spouse Pathway to Business is a course delivered in person or virtually through Veterans Business Outreach Centers to military spouse entrepreneurs.

Military-Affiliated Business Owners Rely on Self-Funding, Investors, and Business Loans for Capital

A Range of Private Sources Provide Capital, but Survey Data Suggest Challenges

Military-affiliated small business owners and entrepreneurs can access the same sources of private capital as any business owner, including self-funding, business loans, and investors (see fig. 2).

· Self-funding. Military-affiliated and other small business owners can leverage their own financial resources to start or grow their businesses. These can include personal savings, borrowing from family or friends, or withdrawing funds from a retirement account. For example, the 2022 Survey of Consumer Finances showed that 86 percent of veteran and 87 percent of nonveteran respondents reported using personal savings and assets to start or acquire their small business.[27] In the same survey, 82 percent of veteran and 68 percent of nonveteran respondents reported using personal savings and assets to finance ongoing operations and improvements of their small business.[28]

· Business loans. Military-affiliated and other small business owners can seek loans from banks, credit unions, and other nonbank financial companies to start or grow their businesses. CFPB estimated the market for small business financing products totaled $1.2 trillion in outstanding balances in 2019.[29] Some banks have initiatives targeted to veterans—for example, one bank we identified provides discounts on origination fees for veteran small business loans. In addition, the American Bankers Association supports access to capital through its Basic Bank Training for Veterans courses, which help veterans, transitioning service members, and military spouses better understand financial services.

· Investors. Military-affiliated and other small business owners may pursue external funding sources, such as venture capital or crowdfunding, to start or grow their businesses. Venture capital provides funding in exchange for an ownership share and often involves investors taking an active role in the company. In contrast, crowdfunding involves raising funds from a large number of individuals, often through an online platform. Crowdfunders do not generally receive an ownership stake or expect a financial return. We spoke with officials from a financial services firm who said they have provided funding to veteran-founded venture capital firms.

Survey data suggest veteran-owned businesses may face challenges accessing capital from large banks. In the 2024 Small Business Credit Survey, majority-veteran-owned businesses (i.e., those at least 51 percent veteran-owned) most frequently cited high interest rates (25 percent), long wait for credit decisions or funding (21 percent), difficult application processes (20 percent), unfavorable repayment terms (7 percent), and lack of transparency (6 percent) (see table 4). Non-majority-veteran-owned businesses (i.e., 0–50 percent veteran-owned) reported these challenges with similar frequency.

Table 4: Reported Challenges Obtaining Financing from Large Banks, by Veteran Ownership Status, 2024

|

Challenge |

Majority-veteran-owned businesses |

Non-majority-veteran-owned businesses |

|

High interest rate |

25% |

30% |

|

Long wait for credit decision or funding |

21% |

21% |

|

Difficult application process |

20% |

22% |

|

Unfavorable repayment terms |

7% |

10% |

|

Lack of transparency |

6% |

12% |

|

Other |

0% |

3% |

Source: GAO analysis of Small Business Credit Survey data. | GAO‑25‑107561

Note: Majority-veteran-owned businesses are those at least 51 percent owned by veterans, and non-majority-veteran-owned businesses are 0–50 percent veteran-owned. Estimates in this table have relative standard errors of less than 40 percent except for “unfavorable repayment terms” and “lack of transparency” for majority-veteran-owned businesses.

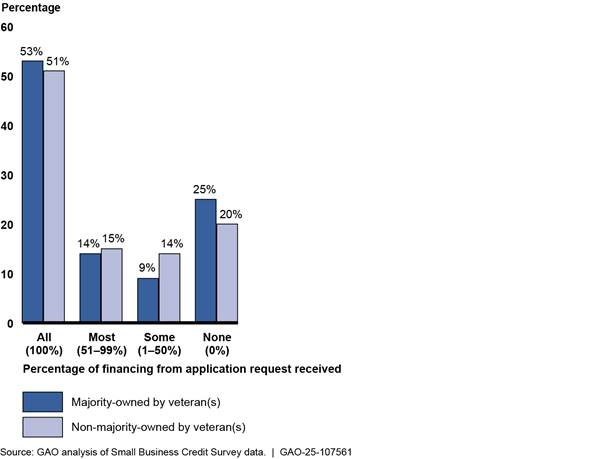

Some majority-veteran-owned small businesses also reported receiving less financing than they applied for through loans, lines of credit, and merchant cash advance applications. In 2024, 25 percent of these businesses reported receiving none of the financing they applied for, 9 percent received some, and 14 percent received most (see fig. 3). Non-majority-veteran-owned small businesses generally reported similar challenges. Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland officials noted that since the COVID-19 pandemic, a growing share of applications has been approved for less than full amount requested. They attributed this trend in part to an increased use of online lenders, which are more likely than other lenders to approve partial amounts. The officials also noted that while the challenges at large banks are similar for majority-veteran and non-majority-veteran-owned businesses, their survey data show that majority-veteran businesses generally have more challenges at small banks than at large banks, and non-majority-veteran businesses generally have fewer challenges at small banks than at large banks.

Note: Majority-veteran-owned businesses are at least 51 percent veteran-owned. Non-majority-veteran-owned businesses are 0–50 percent veteran-owned. Estimates in this figure have relative standard errors of 36 percent or less.

SBA Lending to Veterans Increased in 2019–2024, While USDA Lending Decreased

According to our analysis of fiscal year 2019–2024 SBA data, veterans received approximately 3.9 percent to 4.4 percent of all loans in the 7(a), 504, and Microloan programs (see table 5).[30] The total number of loans provided to veterans generally increased by the end of 2024. SBA did not approve any Military Reservist Economic Injury Disaster loans for veteran-owned businesses during this period. For additional analysis, see appendix III.

Table 5: Number and Percentage of Loans Provided to Veterans for Three SBA Loan Programs, Fiscal Years 2019–2024

|

Number of loans to veterans |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

2024 |

Percentage change, 2019–2024 |

|

7(a) program |

2,491 |

1,934 |

2,175 |

2,242 |

2,706 |

2,999 |

20.4% |

|

(percentage of total) |

(4.8%) |

(4.6%) |

(4.2%) |

(4.7%) |

(4.7%) |

(4.3%) |

|

|

SBA Express programa |

1,070 |

921 |

774 |

901 |

1,112 |

1,031 |

-3.6% |

|

(percentage of total) |

(4.7) |

(5.1) |

(4.3) |

(4.5) |

(4.4) |

(3.9) |

|

|

504 program |

129 |

197 |

242 |

250 |

135 |

163 |

26.4% |

|

(percentage of total) |

(2.1) |

(2.8) |

(2.5) |

(2.7) |

(2.3) |

(2.7) |

|

|

Microloan program |

183 |

221 |

181 |

173 |

196 |

200 |

9.3% |

|

(percentage of total) |

(3.3) |

(3.7) |

(4.0) |

(3.4) |

(3.5) |

(3.8) |

|

|

Total for all programs |

2,803 |

2352 |

2598 |

2665 |

3037 |

3362 |

19.9% |

|

(percentage of total) |

(4.4) |

(4.2) |

(3.9) |

(4.3) |

(4.4) |

(4.1) |

Source: GAO analysis of Small Business Administration (SBA) data. | GAO‑25‑107561

aSBA Express is a 7(a) subprogram.

The proportion of 7(a) loans—SBA’s primary lending program—provided to veterans ranged from 4.2 percent to 4.8 percent during fiscal years 2019–2024, closely reflecting the share of U.S. employer firms that were veteran-owned.[31] According to SBA officials, several agency efforts likely contributed to increased lending to veterans during this period. These efforts include outreach by SBA offices—particularly the Office of Veterans Business Development— and its partners. In addition, officials said that expanded communications about SBA’s COVID-era products and services may have increased awareness of its core offerings. The total number of SBA Express loans provided to veterans fluctuated during fiscal years 2019–2024 but ended on a downward trend. SBA said it could not explain the downward trend in SBA Express lending to veterans during this period.

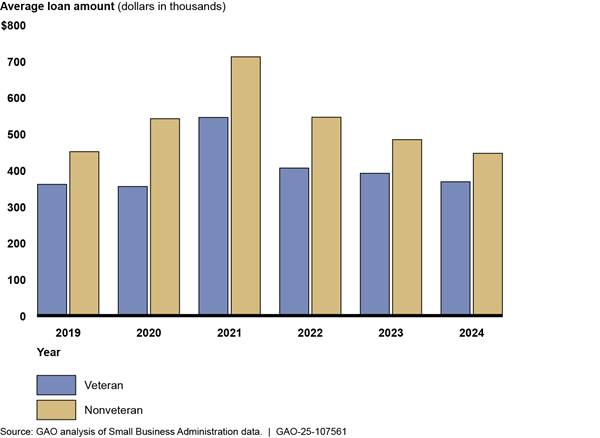

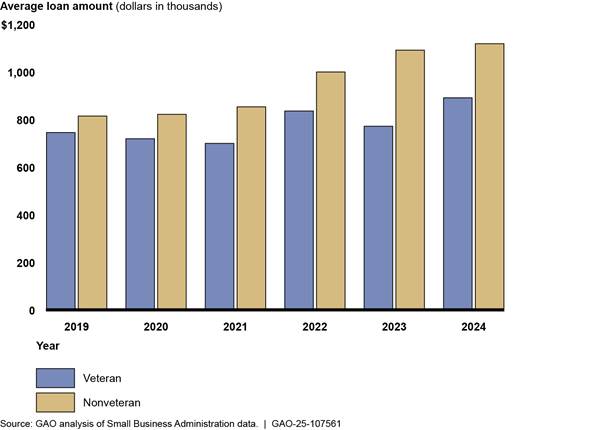

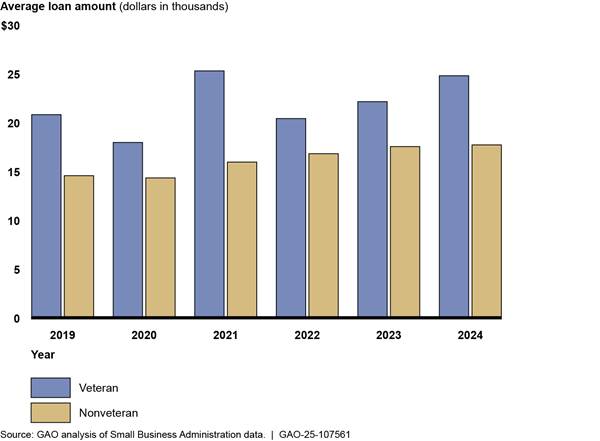

Average loan amounts for veterans generally were lower than for nonveterans in the 7(a) and 504 loan programs in fiscal years 2019–2024. However, for the SBA Express and Microloan programs, veterans averaged higher loan amounts than nonveterans (see table 6).

|

|

Average approved amount (dollars) |

|

|

Loan program |

Veteran |

Nonveteran |

|

7(a) |

$401,752 |

$522,969 |

|

SBA Expressa |

$98,766 |

$98,411 |

|

504 |

$775,390 |

$941,360 |

|

Microloan |

$21,820 |

$16,043 |

Source: GAO analysis of Small Business Administration (SBA) data. | GAO‑25‑107561

aSBA Express is a 7(a) subprogram.

Note: Averages were calculated by dividing the total value of the loans approved during the 6-year period by the total number of loans approved during the 6-year period.

USDA also offers loans through its Farm Service Agency and Rural Development programs for military-affiliated small businesses engaged in farming, ranching, and other agricultural activities in rural communities. In fiscal years 2019–2024, USDA approved between 2.9 and 3.5 percent of all Farm Service Agency loan applications for veterans, based on our analysis of agency data. The number of approved applications for veterans from the Direct Farm Operating, Guaranteed Farm Operating, and Guaranteed Farm Ownership programs generally declined over this period, while loans from the Direct Farm Ownership program increased by the end of 2024 (see table 7). According to USDA officials, these reductions are consistent with the reduction in the total number of approved applications. In particular, the proportion of all Farm Service Agency loans made to veterans was the same in both 2019 and 2024 (3.3 percent). For additional analysis, see appendix IV.

Table 7: Number and Percentage of Applications Approved for Veterans for Five Farm Service Agency Programs, Fiscal Years 2019–2024

|

Loan program |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

2024 |

Percentage

change, |

|

Direct Emergency Farm |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

N/Aa |

|

(percentage of total) |

(2.1%) |

(0.0%) |

(0.0%) |

(0.0%) |

(0.0%) |

(4.3%) |

|

|

Direct Farm Operating |

673 |

734 |

561 |

431 |

444 |

512 |

-23.9% |

|

(percentage of total) |

(3.8) |

(4.1) |

(4.0) |

(3.7) |

(3.6) |

(3.9) |

|

|

Guaranteed Farm Operating |

67 |

68 |

27 |

29 |

28 |

29 |

-56.7% |

|

(percentage of total) |

(1.9) |

(1.8) |

(1.1) |

(1.3) |

(1.6) |

(1.5) |

|

|

Direct Farm Ownership |

234 |

290 |

228 |

173 |

208 |

248 |

6.0% |

|

(percentage of total) |

(3.5) |

(3.8) |

(3.2) |

(2.8) |

(3.3) |

(3.5) |

|

|

Guaranteed Farm Ownership |

86 |

109 |

87 |

68 |

41 |

35 |

-59.3% |

|

(percentage of total) |

(2.2) |

(2.1) |

(1.9) |

(1.8) |

(1.7) |

(1.3) |

|

|

Total for all programs |

1,062 |

1,201 |

903 |

701 |

721 |

826 |

-22.2% |

|

(percentage of total) |

(3.3) |

(3.5) |

(3.2) |

(2.9) |

(3.2) |

(3.3) |

Source: GAO analysis of U.S. Department of Agriculture data | GAO‑25‑107561

aWe did not calculate a percentage change for Direct Emergency Farm loans because the number of loans to veteran-owned businesses during fiscal years 2019–2024 is not sufficient to draw any conclusions.

The number of applications approved for veterans ranged from zero to 734, depending on the program in fiscal years 2019 through 2024. Veterans averaged higher loan amounts than nonveterans under the Direct Emergency Farm, Direct Farm Operating, and Guaranteed Farm Operating loan programs during fiscal years 2019–2024. However, for Direct Farm Ownership and Guaranteed Farm Ownership programs the average approved loan amounts for veterans were lower than those for nonveterans (see table 8).

Table 8: Average Loan Amounts Approved by Veteran Status, USDA Farm Service Agency Loan Programs, Fiscal Years 2019–2024

|

|

Average approved amount (dollars) |

|

|

Loan program |

Veteran |

Nonveteran |

|

Direct Emergency Farm |

$149,148 |

$147,559 |

|

Direct Farm Operating |

$81,973 |

$55,053 |

|

Guaranteed Farm Operating |

$340,508 |

$329,926 |

|

Direct Farm Ownership |

$232,446 |

$278,461 |

|

Guaranteed Farm Ownership |

$550,428 |

$563,678 |

Source: GAO analysis of U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) data. | GAO‑25‑107561

Note: Averages were calculated by dividing the total value of the loans approved during the 6-year period by the total number of loans approved during the 6-year period.

In fiscal years 2019–2024, USDA approved 25 loan applications for veterans under one of its Rural Development programs—the Business & Industry Guarantee Loan program.

Agency Outreach Includes Presentations, Networking, and Online Tools

Federal agencies have taken steps to raise awareness of lending and financial literacy programs among military-affiliated individuals.

· Presentations. Agency officials told us they promoted awareness of lending and financial literacy programs both in-person and virtually during workshops, training events, and webinars. For example, SBA officials said staff from its Office of Veterans Business Development delivered over 100 presentations annually in fiscal years 2023 and 2024. These presentations included information on eligibility for SBA’s guarantee fee waiver and marketing of SBA loan programs. VA’s website promoted an online event, “SBA Hour with Veterans,” in which veterans working at SBA discussed resources available to military-affiliated people. USDA officials reported promoting lending programs during workshops, presentations, and webinars.

· Networking events and program referrals. Agency officials also said they attended networking events where they meet directly with military-affiliated business owners and can connect them to a variety of resources. According to an SBA report, the Office of Veterans Business Development participated in 118 outreach and networking events nationwide in fiscal year 2023, including SBA’s Military Spouse Entrepreneur Summit and the American Legion Small Business Conference.[32] According to USDA officials, USDA staff attend conferences and other events to meet directly with veteran business owners and promote USDA programs.

· Targeted social media and websites. Agencies also used social media and websites to raise awareness about programs and resources available to military-affiliated people. For example, VA uses social media to raise awareness of small business resources offered by other agencies such as SBA. SBA’s Office of Veterans Business Development officials noted that they promote SBA programs, initiatives, and resources several times a month via SBA’s social media channels. In addition, SBA’s website has dedicated pages on its main website focused on training programs, loan programs, and support for veteran and military spouse-owned businesses.[33] DOD’s Office of Financial Readiness website offers help for service members seeking information on accessing personal financial counseling and other information about benefits, saving, and investment. In 2020, DOD launched the MilSpouse Money Mission website to help military spouses access financial education.

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to SBA, DOD, VA, CFPB, USDA, the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, the Department of the Treasury, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the Federal Trade Commission, the National Credit Union Administration, and the Securities and Exchange Commission for review and comment. The National Credit Union Administration provided written comments, reprinted in appendix V. VA also provided written comments, reprinted in appendix VI. VA’s comments summarized various agency financial literacy resources available to military-affiliated people, such as a mandatory course provided to transitioning service members under the Transition Assistance Program that provides information on how service members can protect themselves from scams, fraudulent actions, and predatory lending practices. The other agencies and the National Credit Union Administration provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees and the Acting Director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Secretary of Defense, Secretary of Agriculture, Secretary of the Treasury, Acting Chairman of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Chairman of the Federal Trade Commission, Chair of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve, Chairman of the National Credit Union Administration, and the Chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at lafountainc@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix VII.

Courtney LaFountain

Acting Director, Financial Markets and Community Investment

This report examines (1) any challenges that military-affiliated people may face in building credit or accessing capital for their small businesses, (2) federal financial literacy resources available to military-affiliated people, (3) sources of capital available to military-affiliated people, and (4) agency efforts to raise their awareness about financial literacy and lending programs.

For this report, we focused on federal financial literacy resources and lending programs available to, or specifically designed for, military-affiliated people at nine agencies: Small Business Administration (SBA), Department of Defense, Department of Veterans Affairs, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Federal Trade Commission, National Credit Union Administration, and Securities and Exchange Commission. We selected SBA based on our prior work on veteran lending.[34] We selected the other agencies based on our prior work on financial literacy programs, based on interviews with other agencies in our scope, or because their mission includes services for military-affiliated people.[35] In addition, we interviewed officials from the Department of the Treasury about the Financial Literacy and Education Commission and corresponded with officials from the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland regarding their Small Business Credit Survey data.

To examine the challenges that military-affiliated people may face when building credit or accessing capital for a small business, we interviewed or received written comments from representatives of four nonprofit organizations that support military-affiliated small business owners, as well as five financial services firms or associations with initiatives targeting this population.[36] We identified these organizations from our prior work, our interviews, or because they serve the military community. We contacted two additional organizations that advocate for reservists that did not respond to our request for an interview. We contacted two additional financial services firms but did not conduct interviews with them. In the interviews, we discussed how military-affiliated people access federal and private sources of capital and any challenges they face in building credit and accessing capital. We analyzed our interviews to determine the most frequently noted challenges for each of the populations we discussed. The views expressed by those we interviewed cannot be generalized to all such entities.

We also reviewed government reports, studies, and other literature to identify challenges faced by military-affiliated people. We identified these materials by conducting keyword searches—such as “veteran,” “military,” “small business,” and “entrepreneur” —in databases such as EBSCO, ProQuest, and Scopus. We focused on peer-reviewed literature, government reports, trade and industry articles, and publications from associations or nonprofits covering the period from January 2014 through June 2024. We then selected studies that discussed topics such as obstacles, combat exposure or deployment, and disruptions or gaps related to access to capital or financial literacy. We excluded materials that focused on procurements or contracting, COVID relief funding, federal grants, or state-level funding. We reviewed 47 relevant results.

To describe federal financial literacy efforts for military-affiliated people, we reviewed our prior relevant work on federal financial literacy programs.[37] We also obtained updated information from the nine agencies in our scope through interviews or written responses. This included participant counts and webpage views for 2019 through 2023, where applicable.

To describe the characteristics of veteran- and nonveteran-owned small businesses, we reviewed data from the Census Bureau’s American Business Survey for 2023 and Nonemployer Statistics by Demographics for 2022, the most recent year available. The American Business Survey collects information on the economic and demographic information of approximately 300,000 employer businesses (i.e., those with paid employees) annually. Although these data cover businesses of all sizes, small businesses account for more than 99 percent of all businesses. The Nonemployer Statistics by Demographics provide similar information for nonemployer businesses, using existing administrative records to assign demographic and economic characteristics.

To identify private sources of capital available to military-affiliated people, we reviewed SBA’s website, the Federal Reserve Banks’ Small Business Credit Survey questionnaire, and interviews with representatives of nonprofit organizations and financial services firms that assist military-affiliated small business owners. We analyzed data from the Federal Reserve’s 2022 Survey of Consumer Finances to examine how small business owners fund their businesses. The Survey of Consumer Finances is a triennial, cross-sectional survey with data on U.S. families’ balance sheets, pensions, income, and demographic characteristics. These were the most recent available data at the time of our study.

We also used the 2024 Small Business Credit Survey to assess veteran-owned business’ challenges with obtaining financing and the proportion of financing that veterans and non-veterans received. This survey—conducted in collaboration with all 12 Federal Reserve Banks—collects information from a national sample of firms with fewer than 500 employees. It provides insights into small businesses’ financial condition, credit risk, and financing experiences. These were the most recent available data at the time of our study.

We reviewed data reliability documentation for the sources of survey data (American Business Survey, Nonemployer Statistics by Demographics, Small Business Credit Survey, and Survey of Consumer Finances). We deemed the data to be sufficiently reliable for describing business characteristics of and challenges experienced by veteran-owned small businesses.

In addition, we analyzed SBA data on the number and dollar amount of loans made to veteran-owned small businesses through four SBA lending programs—7(a), 504, Microloan, and Military Reservist Economic Injury Disaster Loan—from fiscal year 2019 through 2024. We also analyzed data on five USDA Farm Service Agency programs and five USDA Rural Development programs from fiscal years 2019 through 2024. These were the most recent data at the time of our study. For 7(a), we reported information that includes all subprograms and only highlighted SBA Express loans because they provide fee relief to veteran-owned as well as veteran spouse-owned small businesses. We did not include other types of SBA disaster loans in our review but focused on Military Reservist Economic Injury Disaster Loans because of their relevance to small business owners with essential employees who are reservists. We reviewed supporting documentation and found the data to be sufficiently reliable for describing trends in program lending to such businesses in this period. We also interviewed SBA and USDA officials about data reliability and their views on trends in the data.

To examine agency efforts to raise awareness about federal financial literacy and lending programs, we interviewed or received written comments from representatives of the nine agencies in our scope. We also reviewed program websites to determine how the selected agencies target military-affiliated people.

We conducted this performance audit from May 2024 to September 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) offers web-based resources for service members, veterans, and military families, which include information about credit, fraud, scams, and service members’ legal rights. One resource, Navigating the Military Financial Lifecycle, provides resources to help military families make financial decisions aligned with military career milestones. CFPB officials said they also distribute printed publications to Military Entrance Processing Stations on financial literacy topics. From 2018 through 2024, according to CFPB officials, there have been approximately 1.3 million users of Ask CFPB web pages related to military questions. They also noted that about 250,000 of the 1.3 million users accessed the Office of Servicemember Affairs’ military-specific pages and tools. CFPB officials also said they distributed more than 680,000 publications to Military Entrance Processing Stations.

Department of Agriculture

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Farm Service Agency provides technical assistance to all loan applicants—such as support with developing financial information and navigating the loan process—through training delivered in partnership with third-party vendors, according to USDA officials. From 2019 through 2023, between 755 and 1,461 people participated in these classes (see table 9).

Table 9: Number of Participants in USDA Farm Service Agency Training Classes, Fiscal Years 2019–2023

|

Fiscal year |

Number of participants |

|

2019 |

1,461 |

|

2020 |

1,232 |

|

2021 |

1,124 |

|

2022 |

850 |

|

2023 |

755 |

Source: GAO analysis of U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) data. | GAO‑25‑107561

Department of Defense

The Department of Defense’s (DOD) Office of Financial Readiness and the military services’ Personal Financial Counseling Programs provide in-person, virtual, and telephone counseling to active-duty service members, reservists, military spouses, and eligible beneficiaries. Personal financial counselors are available during the week, as well as evenings and weekends, and are stationed at military installations worldwide, including armories and reserve centers. From fiscal year 2020 through fiscal year 2023, the program served between 1,925,116 and 3,268,226 participants annually (see table 10).

Table 10: Number of Participants in DOD Office of Financial Readiness Personal Financial Counseling Program, Fiscal Years 2020–2023

|

Fiscal year |

Number of participants |

|

2020 |

1,925,116 |

|

2021 |

3,042,596 |

|

2022 |

3,268,226 |

|

2023 |

2,340,786 |

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Defense (DOD) data. | GAO‑25‑107561

Note: According to DOD, data for fiscal year 2019 are not available.

In addition, beginning in 2022, Office of Financial Readiness officials said they began offering a Financial Well-Being Assessment, which uses 12 questions to identify areas for improvement and provides resources focused on improving financial well-being. The assessment is based on research from CFPB and reflects key elements of financial well-being, including present and future financial security and freedom of choice. It is accessible directly through a DOD website or may be integrated into training and counseling activities. From June 2022 through December 2023, the assessment website had over 9,000 visits.

The Office of Financial Readiness also offers MilSpouse Money Mission, a financial education website designed for military spouses to help them with financial decisions. From fiscal year 2021 through 2023, the site received between 41,966 and 106,710 users annually (see table 11).

|

Fiscal year |

Website sessions |

Users |

|

2021 |

58,875 |

48,364 |

|

2022 |

50,792 |

41,966 |

|

2023 |

128,108 |

106,710 |

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Defense (DOD) data. | GAO‑25‑107561

Note: According to DOD, data for fiscal year 2019 and 2020 are not available.

DOD’s Transition Assistance Program provides training for service members transitioning from active duty to civilian life. According to DOD officials, the program provides financial literacy information through a mandatory Financial Planning for Transition class that helps to ensure departing service members have a viable plan for transitioning to civilian life.[38] It also includes a financial planning module and an individual self-assessment program that encourages service members to evaluate the financial aspects of their transition. From calendar year 2020 through calendar year 2023, annual participation ranged from 171,657 to 193,968 participants annually (see table 12).

|

Calendar year |

Participants |

|

2020 |

193,968 |

|

2021 |

177,125 |

|

2022 |

186,756 |

|

2023 |

171,657 |

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Defense (DOD) data. | GAO‑25‑107561

DOD collects customer satisfaction data from service members participating in the Transition Assistance Program. From 2019 through 2022, more than 80 percent of respondents agreed or strongly agreed with questions related to their satisfaction with the program (see table 13).

Table 13: DOD Transition Assistance Program Customer Satisfaction Survey Results, Percentage of Respondents Who Agreed or Strongly Agreed with Each Question, Fiscal Year 2019–2022

|

Survey question |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

|

I know how to access resources (counselors, online resources) to get answers to transition questions I may have in the next several months. |

93% |

86.6% |

90% |

93% |

|

Overall, the classroom facilities (or virtual environments) were adequate for the program. |

91 |

83.9 |

87 |

90 |

|

Overall, this program was beneficial in helping me gain the information and skills I need to better plan my transition. |

91 |

82.8 |

88 |

91 |

|

Overall, this program enhanced my confidence in transition planning. |

90 |

83 |

87 |

90 |

|

Overall, I will use what I learned in this program in my transition planning. |

91 |

84.3 |

88 |

91 |

|

Overall, the program has prepared me to meet my post-transition goals (employment, education, entrepreneurship goals). |

90 |

82.5 |

86 |

89 |

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Defense (DOD) data. | GAO‑25‑107561

DOD’s Office of Military Community and Family Policy also offers the Spouse Education and Career Opportunities Program, which connects military spouses with tools and resources such as education and training, career coaching and exploration, and employment opportunities. From fiscal year 2019 through fiscal year 2023, program officials said they conducted between 154,000 and 161,000 career coaching sessions annually (see table 14).

Table 14: Number of Coaching Sessions for the DOD Spouse Education and Career Opportunities Program, Fiscal Years 2019–2023

|

Year |

Number of coaching sessions |

|

2019 |

159,000 |

|

2020 |

161,000 |

|

2021 |

154,000 |

|

2022 |

155,000 |

|

2023 |

159,000 |

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Defense (DOD) data. | GAO‑25‑107561

National Credit Union Administration

The National Credit Union Administration offers web-based resources on MyCreditUnion.gov for active-duty servicemembers and military families. According to National Credit Union Administration officials, these resources include information about the Military Lending Act, which protects active-duty servicemembers and their families from unscrupulous lenders by setting a limit on the amount of interest, fees, and other charges on certain loans, among other protections; the Servicemembers Civil Relief Act, which provides protections for military members including an interest rate cap, protection against foreclosure, provisions for lease termination, stay of court proceedings, and protection against repossession; and student loans, including access to special education benefits under the G.I. Bill.[39] Officials said the MyCreditUnion.gov website attracted more than 4.2 million views from 2019 through 2023.

Securities and Exchange Commission

The Securities and Exchange Commission’s Office of Investor Education and Advocacy offers online resources for veterans and military families on its websites, Investor.gov and SEC.gov. Officials provided written comments noting this content receives approximately 25,000 page views annually.

In addition, Securities and Exchange Commission officials noted that they conduct in-person outreach and distribute brochures at military installations. According to the officials, military briefings for junior enlisted and junior officers focus on smart use of credit and debt, establishing an emergency fund, building wealth through tax-advantaged accounts like the Thrift Savings Plan and retirement accounts, the benefits of diversification to reduce risk in investing, and how to spot and avoid investment scams. Briefings for more senior personnel include financial considerations when transitioning from military to civilian careers, the risk and return of investing, common investment products, diversification, how fees impact investing, and how to spot and avoid scams. According to agency officials, during fiscal years 2019–2023, staff participated in more than 300 events and distributed more than 100,000 print publications as part of their veterans and military outreach.

Small Business Administration

The Small Business Administration’s (SBA) Veterans Business Outreach Centers offer entrepreneurial training through the Boots to Business and Boots to Business Reboot programs. These programs provide participants with an introductory understanding of business ownership. Boots to Business courses are hosted by military installations worldwide as part of DOD’s Transition Assistance Program and is transitioning service members and military spouses. Boots to Business Reboot is offered virtually or in community settings for those participants who cannot access military installations. It targets veterans, reservists, and military spouses.

SBA also offers a Boots to Business Revenue Readiness course under a cooperative agreement with Mississippi State University. The course helps participants create a business model and plan in a compressed time frame. The 6-week course is offered in an online classroom format and targets veterans and military spouses.

Between fiscal year 2019 and fiscal year 2023, the Boots to Business program had between 9,515 and 18,125 attendees annually (see table 15). The Boots to Business Reboot program had between 1,623 and 3,290 attendees annually (see table 16).

|

Fiscal year |

Number of training events |

Number of attendees |

|

2019 |

816 |

11,827 |

|

2020 |

733 |

9,515 |

|

2021 |

945 |

12,666 |

|

2022 |

1,014 |

17,076 |

|

2023 |

1,007 |

18,125 |

Source: GAO analysis of Small Business Administration (SBA) data. | GAO‑25‑107561

|

Fiscal year |

Number of training events |

Number of attendees |

||

|

2019 |

141 |

1,623 |

||

|

2020 |

160 |

2,489 |

||

|

2021 |

195 |

3,290 |

||

|

2022 |

184 |

2,790 |

||

|

2023 |

200 |

3,104 |

||

Source: GAO analysis of Small Business Administration (SBA) data. | GAO‑25‑107561

Additionally, the Boots to Business Revenue Readiness program had between 259 and 764 attendees annually between fiscal year 2019 and fiscal year 2023 (see table 17).

Table 17: Number of Events and Attendees, Boots to Business Revenue Readiness Program, Fiscal Years 2019–2023

|

Fiscal year |

Number of training events |

Number of attendees |

|

2019 |

20 |

259 |

|

2020 |

32 |

686 |

|

2021 |

39 |

712 |

|

2022 |

36 |

674 |

|

2023 |

37 |

764 |

Source: GAO analysis of Small Business Administration (SBA) data. | GAO‑25‑107561

SBA also offers the Military Spouse Pathway to Business program, a course designed for military spouse entrepreneurs. The course is delivered in person or virtually through Veterans Business Outreach Centers and covers topics such as market research, economics, and available support resources. The course is intended to help participants learn how to access startup capital, receive technical assistance, and pursue contract opportunities.

Department of Veterans Affairs

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Office of Outreach, Transition, and Economic Development officials said they offer a Wellness Wednesday Financial Literacy Series, a weekly seminar on financial topics presented in partnership with a financial services company. In addition, officials said VA offers three web-based resources. Veteran Benefits Fraud Prevention provides information on fraud and scams that may target veterans. VetCents offers general financial literacy information. Finally, Veteran Saves provides information aimed at helping veterans grow their savings. From 2019 through 2023, the Wellness Wednesday Financial Literacy Series had a total of 1,713 participants, according to agency officials.

Multiple Agencies

Several agencies collaborate to offer financial literacy resources tailored to military-affiliated individuals and small business owners:

· The Federal Trade Commission developed and manages the Military Consumer webpage in collaboration with DOD and CFPB. The site provides financial education for military-affiliated people, including information related to specific military life events such as deployments, permanent changes of station, and promotions. It also covers general financial topics such as money management, buying or renting a home or car, and understanding credit and investments. In addition, Federal Trade Commission officials noted that their website provides information about enforcement actions, including those regarding servicemembers, their families, and veterans, and those that address unfair or deceptive practices in violation of the Federal Trade Commission Act and other illegal practices in violation of numerous statutes and regulations, including the Military Lending Act, enforced by the Commission. Between fiscal year 2019 and fiscal year 2023, the Military Consumer webpage was accessed by around 500,000 unique users, according to agency officials.

· The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation and SBA jointly provide Money Smart for Small Business, a free, instructor-led financial literacy resource. According to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation website, the program includes learning modules on financial management, recordkeeping, and risk management. The curriculum is designed to be taught by staff from financial institutions, small business development centers, economic development offices, and other organizations. In addition, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation officials said they offer financial literacy resources and webinars intended for military-affiliated individuals and small business owners as a part of its Consumer Resource Center website. According to Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation officials, approximately 630 member organizations use Money Smart for Small Business.

This appendix provides data on the number, total dollar amount, and average loan amount of loans approved under the 7(a), 504, and Microloan programs, disaggregated by veteran status, for fiscal years 2019 through 2024. All years cited below refer to fiscal years.

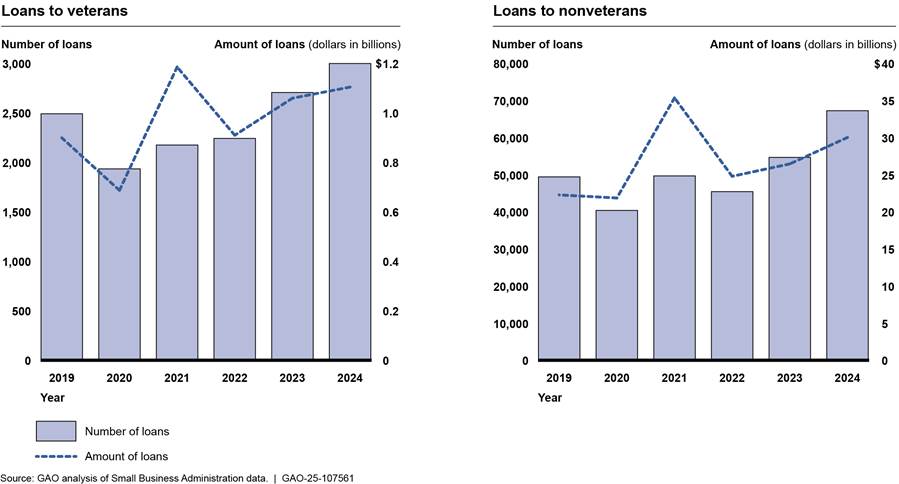

7(a) Program

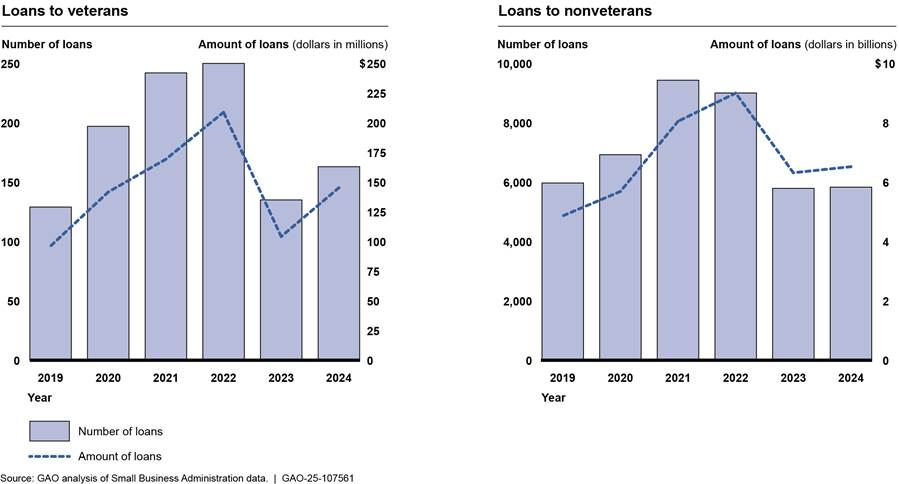

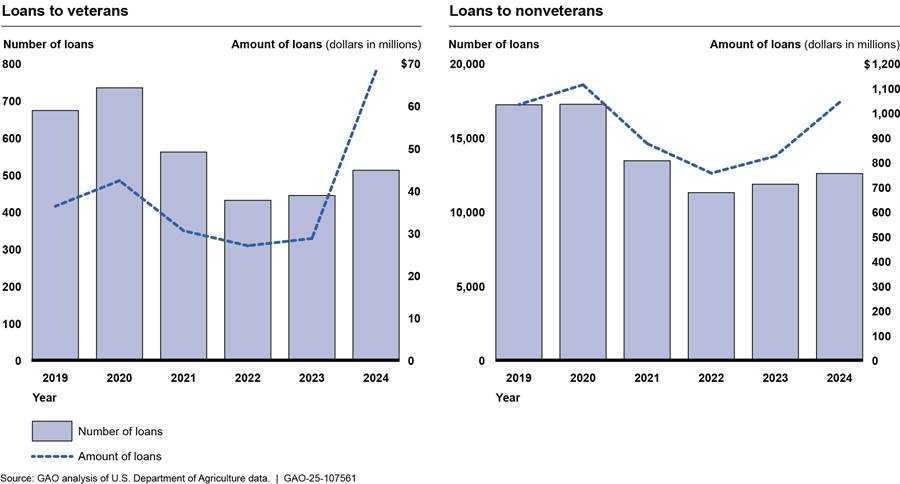

The number and dollar amount of loans to veterans through the 7(a) program generally increased during fiscal years 2019 through 2024. The number and dollar amount of 7(a) loans to nonveterans fluctuated more during the same period but ended on an upward trend. (see fig. 4).

The average 7(a) loan amount for veterans decreased from 2019 to 2020, then increased in 2021. In contrast, the average loan amount for nonveterans during fiscal years 2019 through 2021 increased. From fiscal years 2022 through 2024, the average loan amount for veterans and nonveterans decreased. In each year, the average loan amount for nonveterans was higher than that for veterans (see fig. 5).

504 Program

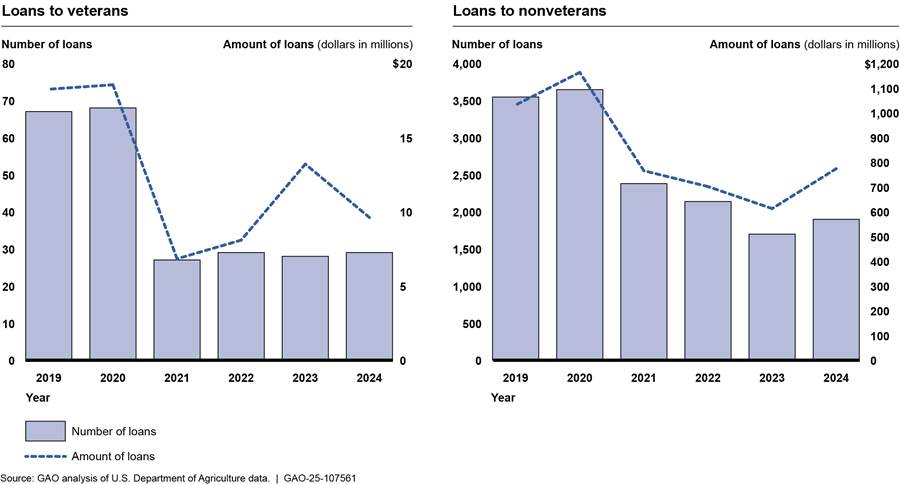

The number and dollar amount of 504 loans specifically to veterans increased each year from fiscal years 2019 through 2022, declined in 2023, then increased in 2024. The number and dollar amount of 504 loans to nonveterans increased from 2019 to 2020 and from 2020 to 2021. From 2021 to 2022, the number of loans to nonveterans decreased, while the dollar amount of these loans increased. In 2023 the number and dollar amount decreased, then increased slightly in 2024 (see fig. 6).

The average 504 loan amount was higher for nonveterans than for veterans in each year for fiscal years 2019 through 2024. Average loan amounts to nonveterans increased during the period, while average loan amounts to veterans fluctuated (see fig. 7).

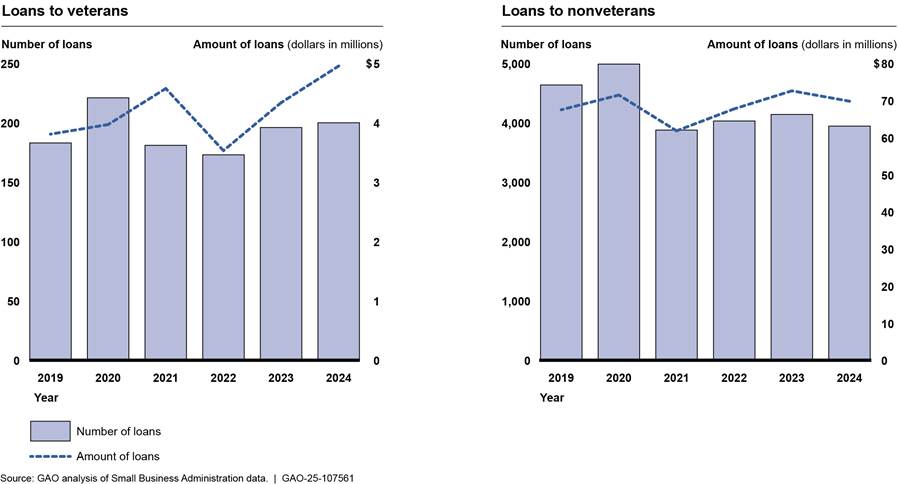

Microloan Program

The number and dollar amount of microloans provided to veterans fluctuated during fiscal years 2019 through 2024. The number and dollar amount of loans provided to nonveterans through the Microloan program also fluctuated during this period (see fig. 8).

In contrast to the 7(a) and 504 loan programs, the average Microloan amount was higher for veterans than for nonveterans in each fiscal year from 2019 through 2024 (see fig. 9).

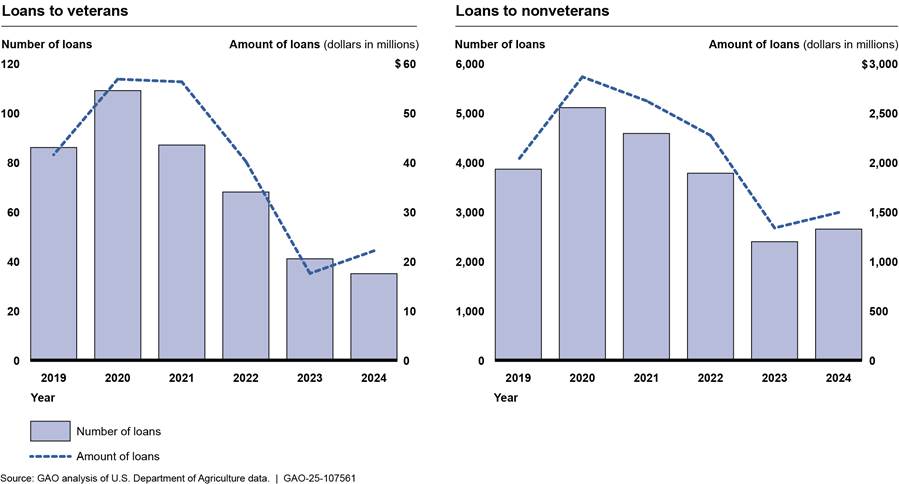

This appendix provides data on the number and total dollar amount of loans approved under the Direct Farm Operating, Guaranteed Farm Operating, Direct Farm Ownership, and Guaranteed Farm Ownership programs, disaggregated by veteran status, for fiscal years 2019 through 2024. All years cited below refer to fiscal years.

Direct Farm Operating Loans

The number and dollar amount of Direct Farm Operating loans to veterans increased from 2019 to 2020, decreased in 2021 and 2022, rose slightly in 2023, and rose in 2024. Loans to nonveterans followed a similar trend (see fig. 10).

Figure 10: Number and Amount of Direct Farm Operating Loans to Veterans and Nonveterans, Fiscal Years 2019–2024

Guaranteed Farm Operating Loans

The number and dollar amount of Guaranteed Farm Operating loans to veterans increased slightly from 2019 to 2020, decreased from 2020 to 2021, and rose in 2022. In 2023, the number of loans went down, and the dollar amount went up. In 2024, the number of loans went up slightly while the dollar amount went down. The number of loans to nonveterans generally decreased from 2019 through 2023, then increased in 2024 (see fig. 11).

Figure 11: Number and Amount of Guaranteed Farm Operating Loans to Veterans and Nonveterans, Fiscal Years 2019–2024

Direct Farm Ownership Loans

Lending to veterans through the Direct Farm Ownership program fluctuated somewhat during fiscal years 2019 through 2024. The number and dollar value of loans to nonveterans also fluctuated during the same period (see fig. 12).

Figure 12: Number and Amount of Direct Farm Ownership Loans to Veterans and Nonveterans, Fiscal Years 2019–2024

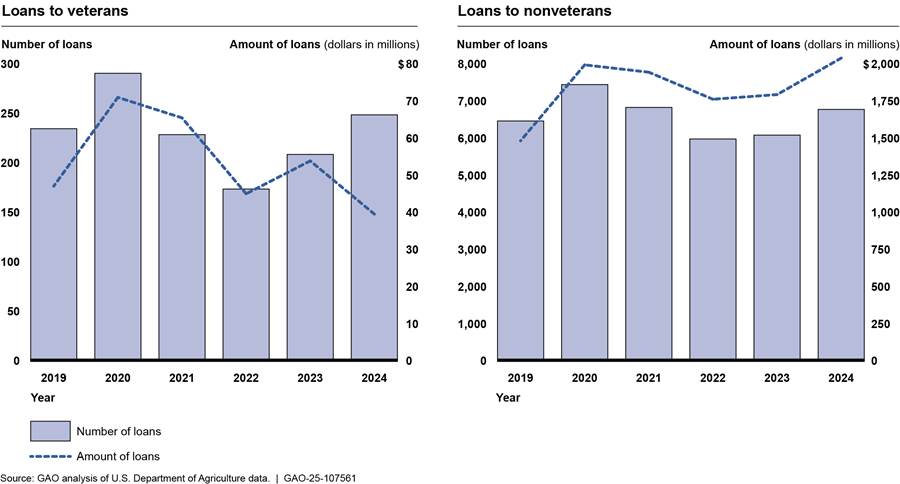

Guaranteed Farm Ownership Loans

The number and dollar amount of Guaranteed Farm Ownership loans specifically to veterans increased from 2019 to 2020. From 2020 to 2021, the number of loans decreased while the dollar amount remained steady. In 2022 and 2023, both the number and dollar amount decreased. In 2024, the number of loans to veterans decreased while the dollar amount increased. The number and dollar amount of Guaranteed Farm Ownership loans to nonveterans increased from 2019 to 2020, decreased from 2021 to 2023, and then increased in 2024 (see fig. 13).

Figure 13: Number and Amount of Guaranteed Farm Ownership Loans to Veterans and Nonveterans, Fiscal Years 2019–2024

GAO Contact