MEDICAID MANAGED CARE

Actions to Improve the Extent to Which Children Receive Medical Screenings and Treatment

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights of GAO-25-107570, a report to congressional committees.

For more information, contact: Michelle B. Rosenberg at rosenbergm@gao.gov.

Why This Matters

Medicaid’s Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment requirements provide a range of preventive and medically necessary health care services to eligible children. Services include well-child screenings to identify potential medical issues, and treatment to improve or maintain the child’s health. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) oversees states’ provision of Medicaid.

GAO Key Takeaways

State Medicaid programs often contract with managed care plans to deliver health care services, including well-child screenings and treatment. In fiscal year 2022, the most recent data available, about 85 percent of the 33 million children covered by Medicaid were enrolled in managed care plans.

Three states we reviewed had programs that withheld a small portion of managed care plans’ funding. The funding was then used to reward plans that improved performance on well-child screening and treatment quality measures. Medicaid officials in Ohio and Washington said their programs were effective tools to encourage plans to improve performance, such as the extent to which eligible children receive well-child screenings. Results from North Carolina are not yet available, but officials said they may add more quality measures.

Selected managed care plans developed incentives for children, their caregivers, and providers to improve the extent to which children receive screenings and treatment. For example, Rhode Island offered children a teddy bear for completing a blood lead screening. Some plans offered providers support with coordinating care. Also, some plans increased payment rates for certain services to encourage improved access to screenings, including behavioral health screenings.

How GAO Did This Study

We reviewed documentation and interviewed Medicaid officials from a non-generalizable sample of four states with large child Medicaid managed care populations. We also reviewed CMS guidance, and interviewed CMS, two managed care plans per state, and seven stakeholder organizations, including those representing children.

Abbreviations

|

CMS |

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services |

|

EPSDT |

Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment |

|

HHS |

Department of Health and Human Services |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

June 25, 2025

The Honorable Mike Crapo

Chairman

The Honorable Ron Wyden

Ranking Member

Committee on Finance

United States Senate

The Honorable Brett Guthrie

Chairman

The Honorable Frank Pallone, Jr.

Ranking Member

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

Federal Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment (EPSDT) requirements are key to ensuring that eligible children (those aged 20 and under) covered by Medicaid have access to services necessary to improve or maintain their health.[1] Medicaid is a joint federal-state health care program for certain low-income and medically needy individuals. In general, EPSDT provides eligible children with a comprehensive set of covered services that includes a wide range of preventive services, including periodic screenings, such as physical exams and other well-child screenings. Services covered under EPSDT also include medically necessary treatment services to correct or ameliorate physical and behavioral health conditions, including those identified through the screenings.[2]

States are responsible for ensuring that the EPSDT requirements are met and that services are available to EPSDT-eligible children covered by Medicaid, even if states contract with one or more managed care plans to deliver some or all of those services.[3] As such, states must ensure that their managed care contracts clearly define plans’ responsibility for covering and providing EPSDT services, and states must monitor managed care plans’ performance. In turn, managed care plans, within the guidelines of the Medicaid program, support states in managing the care of eligible children. In fiscal year 2022, the most recent data available, about 85 percent of the 33 million children covered by Medicaid were enrolled in comprehensive managed care plans.[4]

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), an agency within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), is responsible for overseeing Medicaid at the federal level, including states’ provision of EPSDT to eligible children. According to CMS, during the COVID-19 pandemic, rates for vaccinations, as well as primary and preventive services, among all children in Medicaid declined.[5] For example, CMS reported 22 percent fewer vaccinations received by children up to age 2. In April 2021, nearly one in five caregivers reported they had delayed or forgone care for their children under age 19 in the prior 12 months over concerns about exposure to the virus.[6] In addition, we have reported that children are vulnerable and at-risk of new or exacerbated behavioral health symptoms or conditions related to the pandemic.[7]

As of fiscal year 2023, the most recent year for which data are available, well-child screening rates had not returned to the rates achieved prior to the pandemic. Since then, CMS has taken steps to encourage states to ensure that eligible children receive necessary services. For instance, in 2024, CMS released guidance that included strategies and best practices for states to ensure that eligible children received the full range of health care services under EPSDT, including for behavioral health conditions.[8]

The Bipartisan Safer Communities Act includes a provision for us to review the implementation of EPSDT in Medicaid managed care.[9] This report describes actions taken by (1) selected states, and (2) selected managed care plans, intended to improve the extent to which children in Medicaid managed care receive well-child screenings and treatment.

For both objectives, we selected a non-generalizable sample of four states—North Carolina, Ohio, Rhode Island, and Washington—with large percentages (at least 80 percent) of children in Medicaid enrolled in managed care, and to obtain variation in geography and the number of children enrolled. We reviewed relevant documentation from these states’ Medicaid agencies, as well as interviewed state officials about their efforts to improve well-child screenings and treatment for children in Medicaid managed care. For example, we reviewed documentation on selected states’ incentive programs for Medicaid managed care plans intended to improve the number of eligible children receiving well-child screenings. In each of the four selected states, we also selected a non-generalizable sample of two managed care plans to obtain variation in not-for-profit and for-profit operating status and enrollment size. We reviewed documentation and interviewed officials from each of the Medicaid managed care plans to understand their efforts to improve well-child screenings and treatment for eligible children.[10]

Additionally, for both objectives, we reviewed relevant CMS guidance on EPSDT, such as the 2024 CMS State Health Official Letter on best practices for adhering to EPSDT requirements, and interviewed CMS officials. Lastly, we interviewed officials from a non-generalizable sample of seven stakeholder organizations, including researchers and organizations representing providers and Medicaid beneficiaries, to understand their perspectives on EPSDT, including challenges eligible children face receiving well-child screenings and accessing treatment.

We conducted this performance audit from May 2024 to June 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

EPSDT

Federal law specifies that EPSDT covers screening, vision, dental, and hearing services, as well as other Medicaid coverable services that are necessary to correct or ameliorate any conditions.[11] EPSDT generally entitles eligible children to these services regardless of whether such services are covered in a state’s Medicaid state plan and regardless of any restrictions the state may impose on coverage for adult services.[12]

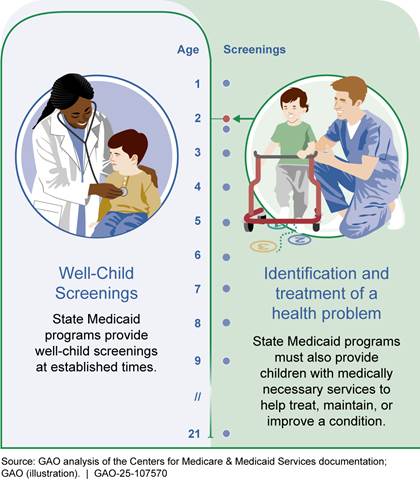

The federal government and states jointly share responsibility for implementing EPSDT. CMS, as part of its Medicaid oversight responsibilities, approves state Medicaid plans, which describe how the state administers its Medicaid program, including components related to the provision of EPSDT. CMS also develops and issues general guidance to states about EPSDT, such as explanations of covered services and strategies for providing those services. States inform eligible children and their caregivers about EPSDT, including providing information on child health assessments, known as well-child screenings.[13] States also establish age-appropriate timelines, or periodicity schedules, for well-child screenings, as well as inform eligible children and their caregivers how to access needed services, such as treatment. (See fig. 1.)

· Well-child screenings. Well-child screenings play a critical role in assessing and identifying health issues early by checking children’s health at age-appropriate intervals. In general, states’ periodicity schedules call for multiple screenings for infants up to age 2, and annual screenings for children 3-years or older. Early identification of potential medical conditions through well-child screenings allows for timely intervention and treatment, potentially leading to better outcomes.[14] A provider, whether participating in Medicaid or not, can conduct a screening that initiates EPSDT coverage for treatment.

· Treatment. Under EPSDT, when a well-child screening suggests a need for treatment, states must provide all medically necessary Medicaid coverable diagnostic and treatment services to the child. According to CMS, eligible children are entitled to treatment services even if they do not cure a condition, such as when services would maintain or improve a condition, prevent it from worsening, or prevent development of additional health issues.[15] In addition, EPSDT covers treatment for conditions identified outside of a periodic well-child screening. For example, if an eligible child experiences a behavioral health episode, EPSDT covers medically necessary Medicaid coverable services regardless of whether the condition was present and identified during a well-child screening.

Medicaid Managed Care

Managed care has become the predominant method for delivering services in Medicaid. Over 40 states used comprehensive managed care plans to provide benefits to beneficiaries, including children, according to analysis of fiscal year 2022 data from the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission.[16] Under managed care, the state Medicaid agency contracts with managed care plans to provide a range of services and pays a set amount for each beneficiary. The state makes these payments, referred to as capitation payments, regardless of how much the plan then pays providers or the number of services Medicaid beneficiaries use. This is in contrast to a fee-for-service delivery system in which the state pays providers for each service delivered to a Medicaid beneficiary.

Managed care plans generally cover all or most Medicaid-covered services, including EPSDT; however, some services may be delivered separately.[17] For instance, some states elect to deliver dental or behavioral health services on a fee-for-service basis or through a different managed care plan. State Medicaid agencies’ contracts with managed care plans specify what services they are responsible for providing, as well as other requirements. For example, contracts may specify that managed care plans are to maintain adequate provider networks to deliver contractually required services, including EPSDT services, and they are expected to conduct ongoing efforts to improve the quality of care Medicaid beneficiaries receive. CMS has issued guidance to support states in their efforts to improve the monitoring and oversight of managed care.[18]

EPSDT Reporting and Performance Monitoring

CMS requires states to annually report about the provision of certain EPSDT services. These data provide information about the utilization of well-child screenings and access to treatment, and can also support efforts to develop performance targets that assist both CMS and state efforts to improve care. Two key data sources for information on EPSDT services are the Form CMS-416 and the Core Set of Children's Health Care Quality Measures (Child Core Set).

· CMS-416. The CMS-416 provides aggregate information about EPSDT services, such as the total number of eligible children receiving age-appropriate well-child screenings and total number of eligible children referred to treatment.[19] CMS and states can use data reported on the CMS-416 to assess performance on key metrics, such as the participant ratio, which refers to the percentage of eligible children who received at least one recommended well-child screening. According to the most recent data from CMS, in fiscal year 2023, 51 percent of eligible children received at least one recommended well-child screening, down from the 59 percent we reported in 2019.[20]

· Child Core Set. The Child Core Set provides information about the quality of health care provided to eligible children and supports state efforts to improve health care quality and health outcomes.[21] Broadly, the Child Core Set includes performance measures related to the provision of EPSDT services. For example, the 2023 Child Core Set included eight measures to assess the receipt of primary and preventive care, such as the extent to which children receive developmental screenings and visits for well-child screenings.[22] In addition, the Child Core Set includes measures about access to treatment for certain conditions, such as asthma, or timeliness accessing follow up treatment.[23]

While these data sources provide some information that can be helpful for monitoring eligible children’s access to and use of Medicaid services, CMS and some stakeholders we interviewed noted that monitoring access to and coordination of treatment can be more challenging than monitoring well-child screenings for several reasons. For example:

· Treatment can refer to an entire spectrum of care involved with a diagnosis and is based on specific clinical guidelines, which may be too complex to be contained within a specific code a provider would use to bill for a service or quality measure.

· Existing performance measures may not fully capture specific challenges eligible children experienced accessing treatment. For example, measures such as follow-up after an emergency department visit provide aggregate information on the timeliness of follow-up care. The measures do not, however, capture why timely follow-up care was not provided, such as if the provider did not have an appointment available within the measured time frame.

Selected States Provided Incentives to Managed Care Plans to Improve Performance on Well-Child Screening and Treatment Quality Measures

Three of our selected states—North Carolina, Ohio, and Washington—had ongoing financial incentive programs aimed at improving Medicaid managed care plans’ performance on certain quality measures related to well-child screenings and treatment. Medicaid officials from our fourth selected state, Rhode Island, told us the state has previously used financial incentives aimed at improving managed care plans’ performance on certain EPSDT-related quality measures; however, the state no longer uses these performance improvement incentives, due in part to changes the state made to its managed care plan structure.[24]

Medicaid officials in North Carolina, Ohio, and Washington told us they used various data sources to monitor how well managed care plans performed on well-child screening and treatment performance measures.[25] For instance, these three states included in their financial incentive programs certain quality measures similar to those found in CMS’s Child Core Set. For example, the 2023 Child Core Set included the well-child visit measure, which assesses the percentage of eligible children who completed at least one well-child screening during the year, across various age groups, such as eligible children aged 0-15 months, 3-11 years, and 12-17 years. Subsequently, the states set performance improvement goals for these measures and used financial incentives as rewards for managed care plans’ performance relative to those goals.

The states financed the incentives using capitation payment withholds wherein the state retains a small percentage of the capitation payments (e.g., 1 percent to 3 percent) and uses a portion or all of the withheld amount later to reward plans that performed well on the performance measures.[26] (See table 1.) For example, Ohio’s incentive program includes goals across a number of performance measures for certain populations, such as increasing the number eligible children aged 0-15 months who receive well-child visits. The managed care plans in Ohio can earn back withheld funds—up to 3 percent of capitation payments—by demonstrating improvements across key components of the overall program.[27]

|

State |

Performance period |

Program description |

|

North Carolina |

January 2024 – |

North Carolina designed its program to withhold 1.5 percent of all capitation payments. The program included a goal to increase the percentage of eligible children receiving all recommended vaccines by age 2. The state set targets for managed care plans to individually achieve a 5 percent increase in the childhood immunization status quality measure for all eligible children insured by the plan, and a 10 percent increase for eligible Black children. North Carolina’s managed care plans earn full or partial amounts of the withheld capitation payments according to their performance relative to these targets at the end of the performance period. |

|

Ohio |

January 2025 – |

Ohio designed its program to withhold 3 percent of all capitation payments, which are returned when managed care plans achieve certain goals within the fixed period of time and performance period, such as increasing rates for the following quality measures for eligible children: · well-child visits for children (ages 0–15 months, 12–17 years); · follow-up after an emergency department visit for substance use (13–17 years); · follow-up after an emergency department visit for mental health (6–17 years); and · asthma medication ratio for children (5–18 years).b The state set targets for managed care plans to achieve a 5 percent to 10 percent rate increase collectively, depending on the quality measure. The state also set specific health equity-related targets for eligible Black children, ranging from 3.3 percent to 6.7 percent rate increases, depending on the quality measure. Managed care plans earn 27 percent of the withheld capitation payments for meeting the targeted increases. |

|

Washington |

January 2024 – |

Washington designed its program to withhold 2 percent of monthly capitation payments and included goals to increase rates for the following quality measures for eligible children: · child and adolescent well-child visits (3–11 years); · antidepressant medication management (18+ years); · follow-up care for children prescribed medication for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (6–12 years); · follow-up after an emergency department visit for substance use (13+ years); and · follow-up after an emergency department visit for mental health (6+ years). The state set targets for managed care plans to perform either in the 75th percentile nationally or achieve a statistically significant improvement in performance. Managed care plans can earn up to 75 percent of the withheld capitation payments within the fixed period of time and performance period by meeting certain targets on quality measures and the remaining is earned through implementing other activities to improve quality, such as implementing provider incentives. |

Source: GAO analysis of selected states’ Medicaid and managed care plans documentation. | GAO‑25‑107570

Note: We selected four states for our review. One state, Rhode Island, told us the state previously used quality measure incentives for well-child screenings and treatment. Although the state continues to collect data to monitor quality, state Medicaid officials said the measures are no longer used as part of the withhold program.

aThe state’s withhold program includes a number of projects that managed care plans complete to earn back withhold amounts. Managed care plans are expected to focus on improving certain child quality measures during the period of January 2025 – December 2025.

bThis measure assesses the percentage of children with persistent asthma who were dispensed appropriate medication to control their condition.

Medicaid officials in Ohio and Washington view their incentive programs as effective tools to encourage plans to focus on improving performance across well-child screening and treatment measures. For example, in Washington, data from prior years showed improvement in the completion of well-child screenings among children 3- to 11-years of age. Specifically, the percentage of children in this age group who completed their well-child screenings increased from 46.9 percent in 2020 to 57.2 percent in 2023.[28] Given the performance periods of the selected states’ current incentive programs, data are not yet available to evaluate their effectiveness. For instance, data on North Carolina’s incentive program performance will not be available until 2026.[29] In the meantime, Medicaid officials in North Carolina told us they are considering adding more quality measures to their program that focus on EPSDT-related screenings and treatment.

Selected Managed Care Plans Used Education, Support Services, and Incentives to Improve Children’s Receipt of Screenings and Treatment

The selected Medicaid managed care plan officials we spoke with described various efforts to improve the extent to which children receive well-child screenings and treatment. Specifically, these efforts include education, support services, and incentives for (1) eligible children and their caregivers, and (2) providers.[30]

EPSDT Education, Support Services, and Incentives for Eligible Children and Their Caregivers

EPSDT Education

Officials from the selected managed care plans told us they used various strategies to educate eligible children and their caregivers on the importance of well-child screenings. These strategies included the use of handbooks, other supplemental materials, well-child reminders, and community outreach.[31] Officials at a managed care plan in North Carolina told us that much of the EPSDT education involves educating eligible children and their caregivers on the expectations for and benefits of routine well-child visits, and helping them get back on track without fear of judgment if they have missed appointments.

Beneficiary handbook updates. In general, officials at the selected managed care plans reported updating, standardizing, and ensuring that their plans’ beneficiary handbook language about EPSDT was clear and accessible. For example, handbook updates included revisions to the definition of EPSDT to make it easier for eligible children and their caregivers to understand. In other cases, revisions included better alignment with standardized language developed by the state Medicaid agency or in response to a CMS effort that reviewed handbooks across all states for accuracy and clarity.[32]

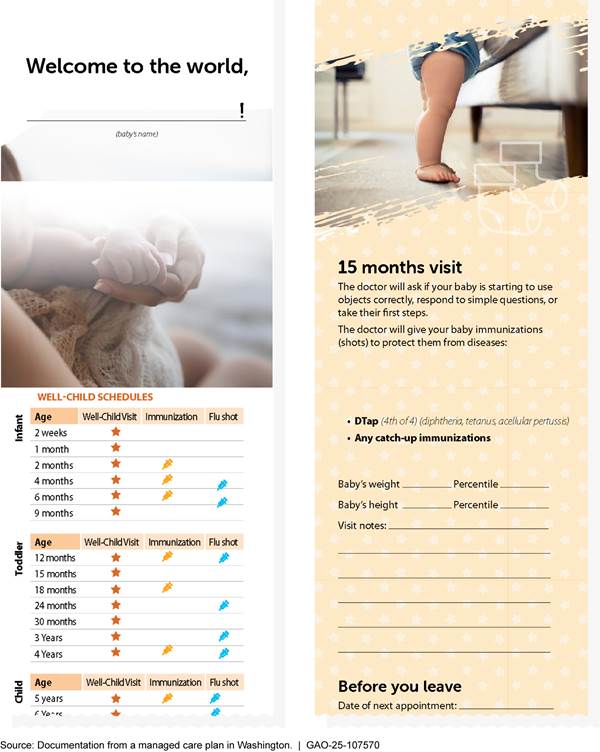

Supplemental materials. Officials from the selected managed care plans told us they leveraged supplemental materials to provide additional education on the importance of regular well-child screenings.[33] For example, officials at a managed care plan in Washington told us the plan distributed “baby passports” that included information to educate caregivers about routine well-child screenings and immunizations during the first 18 months of life. (See fig. 2.) The initiative began in 2018; as of November 2024, according to plan officials, they had distributed over 24,000 baby passports. Plan officials noted they found the initiative to be successful and may explore other opportunities to provide materials to other age groups or for vulnerable populations. Ohio officials described a plan to distribute wellness calendars to eligible children and their caregivers to encourage regular visits. The calendar included pictures and easy to read language, as well as relevant images depicting health observances—such as a heart for “Heart Month” in February.

Figure 2: Example of a Medicaid Managed Care Plan’s Supplemental Materials about Well-Child Screenings

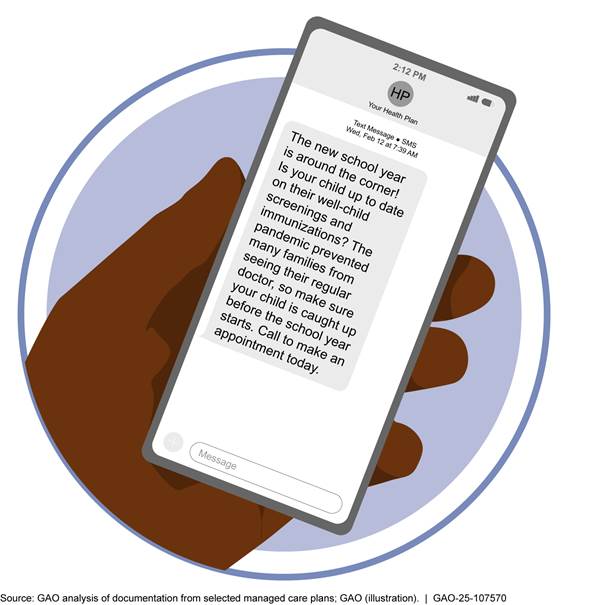

Well-child visit reminders. Officials from several of the selected managed care plans told us they send reminders to eligible children and their caregivers about well-child screenings. The types of reminders and their method of delivery varied. For instance, plan officials described reminders that encouraged eligible children and their caregivers to schedule appointments for well-child screenings, as well as reminders about upcoming appointments or overdue visits. Additionally, officials described sending reminders through multiple methods—such as through text messages, phone calls, or mailings—and at various times of the year, which can help increase the likelihood of eligible children attending appointments and receiving age-appropriate screenings.[34] For example, officials from a managed care plan in Washington described sending more than 47,000 text message reminders during the back-to-school period.[35] (See fig. 3.)

Community-based outreach. Several of the selected managed care plans described organizing community-based outreach efforts and events to help educate eligible children and their caregivers on the importance of regular well-child screenings. These included events such as health fairs, block parties, and baby showers. Officials at a managed care plan in North Carolina described hosting an event at a local bowling alley, which allowed plan officials to meet with eligible children and their caregivers to address questions. Officials at a plan in Rhode Island told us that community-based efforts are particularly important because some eligible children and their caregivers may not be responsive to text and email reminders about well-child screenings. Other managed care plan officials described how community-based events provide opportunities to identify and address misunderstandings about well-child screenings. For example, officials at a plan in Ohio said through their community-based efforts, they learned that eligible children and their caregivers were unaware that the human papillomavirus vaccine was part of a two-dose series.[36] Officials said they attributed improvements in the vaccination rate to their efforts to educate eligible children and their caregivers about the importance of completing the vaccine series.

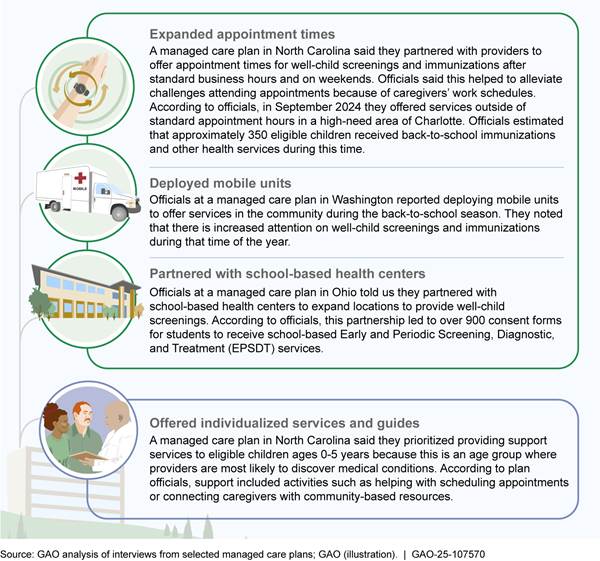

Support Services

Selected managed care plans reported providing support services to eligible children and their caregivers through a range of activities, such as by offering expanded appointment times for well-child screenings or additional assistance accessing EPSDT services for treatment.[37] (See fig. 4.)

Figure 4: Examples of Support Services Medicaid Managed Care Plans Provided to Eligible Children and Their Caregivers

Note: The involvement of caregivers—including parents or other legal guardians—often helps to facilitate eligible children’s access to benefits.

Financial Incentives and Other Rewards

Each of the selected managed care plans offered financial incentives to eligible children and their caregivers to encourage them to complete a well-child visit or certain other services. According to documentation we reviewed, the plans varied in the financial incentive amounts and the design of the programs. Across the managed care plans, financial

|

Blood Lead Screenings for Children

Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment entitles children to a comprehensive set of Medicaid covered services, including blood lead screening tests. According to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), screenings are important for identifying children with elevated blood lead levels at as young an age as possible, because lead exposure can harmfully affect nearly every system of the body and cause developmental delays. Blood lead screenings should occur at 12 months and 24 months of age. Additionally, children between 24 and 72 months of age should receive a blood lead screening if they have not been previously screened. Officials at a managed care plan in Rhode Island reported giving children a teddy bear after completing laboratory testing for blood lead screening. In August 2019, we recommended CMS work with states and relevant federal agencies to collect accurate and complete data on blood lead screening to monitor state compliance with its blood lead screening policy As of June 2025, CMS had taken some action to improve blood lead screening data, but further action is needed to fully implement the recommendation. Source: GAO review of documentation from a managed care plan in Rhode Island, didesign/stock.adobe.com (photo); and GAO, Medicaid: Additional CMS Data and Oversight Needed to Help Ensure Children Receive Recommended Screenings, GAO‑19‑481 (Washington, D.C.: Aug. 16, 2019). | GAO‑25‑107570 |

incentives ranged from $10 to $50 per eligible service or visit.[38] For example, a managed care plan in Rhode Island offered $25 gift cards for each qualifying service an eligible child received within a 12-month period. Similarly, a managed care plan in Ohio provided reward cards with amounts ranging from $10 to $30 for each qualifying service an eligible child received. The reward program in Ohio allowed eligible children and their caregivers to use the reward card for purchases for health and wellness items (e.g., lotion, toothpaste) or at approved retail stores.

In addition to financial incentives, officials at the selected managed care plans described other rewards for well-child visits or certain other services. For example, officials at a managed care plan in North Carolina described offering rewards, such as diapers, for achieving healthy outcomes or to encourage caregivers to bring newborns in to complete well-child visits.

Some managed care plan officials also described success with programs that incentivize specific components of well-child screenings. For example, officials at a managed care plan in Rhode Island described creating a program that offered eligible children a teddy bear after completing laboratory testing for blood lead screening. According to analysis by the managed care plan, lead screening rates among eligible children 2-years of age increased from 78.0 percent in 2022 to 80.6 percent in 2023; officials attribute these increases to the teddy bear program. Furthermore, officials at the managed care plan told us they believed the teddy bear motivated caregivers to have their child screened more than the $25 gift card that was also available for completing the screening. As of November 2024, officials at the managed care plan anticipated expanding the program and incorporating lessons learned.

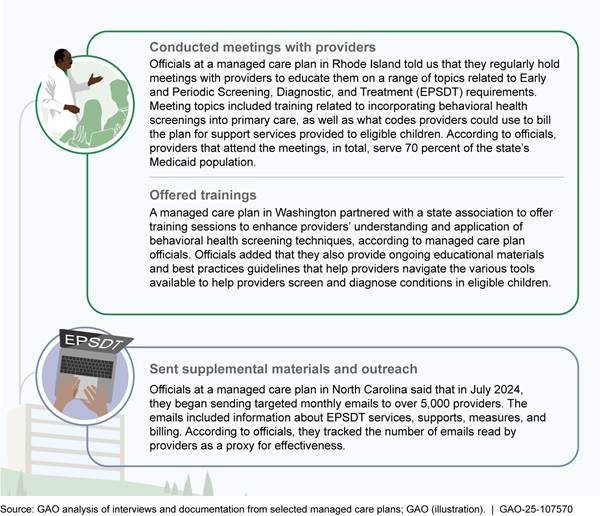

EPSDT Education, Support Services, and Incentives for Providers

EPSDT Education

Officials from selected managed care plans reported hosting meetings and trainings, and reaching out to providers to educate them about EPSDT in an effort to improve well-child screening rates and access to and coordination of treatment. (See fig. 5.) The methods used to provide education to providers included methods similar to those that plan officials reported using for educating eligible children and their caregivers, such as providing emails with information to supplement handbooks. Further, because providers are generally aware of the periodicity schedule for well-child screenings, according to some plan officials, education efforts focused on other topics, such as highlighting the fact that EPSDT includes comprehensive treatment and care coordination for eligible children.

Support Services

Officials at some of the selected managed care plans described efforts to offer additional support services to providers to assist with care coordination. Such efforts included providing additional staff or software to assist with care coordination that requires different levels of plan involvement or engagement with providers. (See fig. 6.) According to officials at a managed care plan in Rhode Island, providers have different needs or capabilities for conducting care coordination, and the level of plan involvement varies based on those needs. Additionally, some stakeholders we interviewed told us that eligible children and their caregivers are more likely to view their providers as a trusted source of information, and as such, care coordination generally occurs more at the provider level than at the managed care plan level.

Figure 6: Examples of Selected Medicaid Managed Care Plans’ Efforts to Provide Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment (EPSDT) Support Services

Financial Incentives and Billing Flexibility

Officials from some of the selected managed care plans included in our review said they used various financial incentives to encourage providers to focus on EPSDT-related state or plan initiatives. This included incentive payments for reaching performance targets. According to plan officials and documentation we reviewed, in some cases, the performance programs are designed to improve well-child screening rates as part of state-wide Medicaid initiatives. For example, managed care officials at both plans we interviewed in Washington said they developed pay-for-performance measures to improve well-child screening and immunization rates, which were areas of focus for the state. Specifically, officials at one of the plans told us providers could earn bonus payments—which can vary based on the individual contract with the provider—by meeting performance targets for well-child screening and immunization rate improvement. Alternatively, the other plan’s performance program rewarded providers for improvements in well-child screening rates among eligible children ages 3- to 11-years old. According to documentation we reviewed, the incentive program rewarded providers for both increases in the number of completed well-child visits between July 15, 2024, and December 31, 2024, and how well the provider increased rates for well-child screenings overall.[39] For example, at the end of the program, providers whose well-child screening rates were below the 75th percentile earned $75 per eligible child that completed a visit, while providers at or above the 75th percentile earned $125 per eligible child.

Similarly, officials at a managed care plan in Rhode Island described an incentive program that offered providers an opportunity to earn incentives for performance on well-child measures that were part of a state-wide initiative to improve well-child screenings. Officials at the plan noted that their provider incentives were so successful in improving well-child visit performance that their focus shifted to providing incentives for child behavioral health screenings, like depression.

Additionally, some managed care plans in the selected states offered increased payment rates for certain services, or same-day billing flexibilities, to encourage providers to improve access to well-child screenings, including those for behavioral health.[40] For instance, according to documentation from a selected managed care plan in Ohio, providers may receive enhanced payment rates for including well-child screenings in the physical exams children receive to allow them to play sports, if the eligible child is due for that screening. In addition, according to officials from both Ohio managed care plans included in our review, all plans in the state permit same-day billing for a well-child visit and a behavioral health visit.

The officials noted that providers have shared that it is challenging for eligible children and their caregivers to attend an additional appointment for behavioral health services after leaving a primary care visit. As such, same-day billing helps to alleviate billing challenges for providers and to encourage the provision of behavioral health services by allowing providers to be paid for both a physical health and behavioral health exam or screening that occur during the same visit, according to some plan officials. In addition, same-day billing may reduce the need for multiple appointments or potential delays in coordinating behavioral health treatment, according to some stakeholders we interviewed. They also noted that same-day billing may help address provider apprehension in administering certain behavioral health services or improve care coordination for treatment.

Agency Comment

We provided a draft of this report to HHS for review and comment. HHS provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Health and Human Services, and other interested parties. In addition, this report will be available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff members have any questions about this report, please contact me at RosenbergM@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix I.

Michelle B. Rosenberg

Director, Health Care

GAO Contact

Michelle B. Rosenberg, RosenbergM@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Peter Mangano (Assistant Director), Kimberly Perrault (Analyst-in-Charge), Ariel Landa-Seiersen, Drew Long, Jennifer Rudisill, Claire Rueth, Ethiene Salgado-Rodriguez and Brian Schmidt-Meyer made key contributions to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]For the purposes of our report, we refer to individuals aged 20 and under as children, unless otherwise noted.

[2]EPSDT is defined in federal law to include screening, vision, dental, and hearing services, as well as other medically necessary services identified in section 1905(a) of the Social Security Act to correct or ameliorate any condition discovered through screening, regardless of whether such service is covered under the state Medicaid plan. 42 U.S.C. § 1396d(r).

[3]Managed care plans can include comprehensive, risk-based managed care through managed care organizations, and limited benefit plans, such as prepaid inpatient health plans and prepaid ambulatory health plans.

[4]See Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, MACStats: Medicaid and CHIP Data Book (Washington, D.C.: December 2024).

[5]See Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, CMS Issues Urgent Call to Action Following Drastic Decline in Care for Children in Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program Due to COVID-19 Pandemic, (Baltimore, Md.: Sept. 23, 2020).

[6]The Urban Institute analyzed survey data from the Health Reform Monitoring Survey (April 2021), which included responses from randomly selected households with children. Data included information for a sample of approximately 2,400 children. See Gonzalez, Dulce; Karpman, Michael; Haley, Jennifer, Worries about the Coronavirus Caused Nearly 1 in 10 Parents to Delay Needed Health Care for their Children in Spring 2021, Urban Institute (2021). The involvement of caregivers—including parents or other legal guardians—often helps to facilitate access to benefits.

[7]See GAO, Behavioral Health and COVID-19: Higher-Risk Populations and Related Federal Relief Funding, GAO‑22‑104437 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 10, 2021).

[8]See Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, State Health Official Letter 24-005: Best Practices for Adhering to Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment (EPSDT) Requirements (Baltimore, Md.: Sept. 26, 2024).

[9]Pub. L. No. 117-159, § 11004, 136 Stat. 1313, 1319 (2022). In addition, the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act required CMS to review state implementation of EPSDT and provide technical assistance and issue guidance to states about EPSDT requirements, among other things. The agency is also required to submit a report to Congress.

[10]Due to the open-ended nature of our interview questions, we cannot quantify the number of plans that have certain efforts. Rather, efforts presented represent examples reported by plan officials.

[11]Medicaid coverable services are those identified in section 1905(a) of the Social Security Act.

[12]EPSDT is mandatory for categorically eligible individuals aged 20 and under covered under the state plan and may be provided at state option to other eligible children for Medicaid or CHIP. However, EPSDT is not available to individuals with limited Medicaid eligibility, such as those without satisfactory immigration status who are eligible only for treatment of an emergency medical condition or those receiving limited services, such as family planning.

[13]At a minimum, well-child screenings include comprehensive health and developmental history, including both physical and mental health development assessments; physical exams; age-appropriate immunizations; vision and hearing tests; dental exams; laboratory tests, including blood lead level assessments at certain ages; and health education, including anticipatory guidance.

[14]Without routine screening, at least 50 percent of children with developmental or behavioral disorders are not detected before kindergarten, according to research published by the American Academy of Pediatrics. See Lipkin, Paul H., Michelle M. Macias, “Promoting Optimal Development: Identifying Infants and Young Children with Developmental Disorders Through Developmental Surveillance and Screening,” Pediatrics (January 2020); 145 (1): e20193449.

[15]According to CMS guidance on EPSDT, limits cannot be placed on the number of screenings covered and prior authorization cannot be required for children’s periodic screenings. Additionally, states may not place hard limits on EPSDT services. According to CMS, states may be permitted to place tentative limits on services, as a form of utilization control, but additional services must be provided if deemed medically necessary. See Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, EPSDT – A Guide for States: Coverage in the Medicaid Benefit for Children and Adolescents (June 2014). We have previously reported on the use of utilization management tools, such as prior authorization, and made two recommendations to CMS on the use of prior authorization for EPSDT services. See GAO, Medicaid: Managed Care Plans’ Prior Authorization Decisions for Children Need Additional Oversight, GAO‑24‑106532 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 30, 2024). As of March 2025, these recommendations had not been implemented.

[16]See Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, “Exhibit 30. Percentage of Medicaid Enrollees in Managed Care by State and Eligibility Group, FY 2022,” MACStats: Medicaid and CHIP Data Book (Washington, D.C.: December 2024).

[17]Any medically necessary EPSDT services not provided by the managed care plan remain the responsibility of the state Medicaid agency. As such, eligible children should have access to all EPSDT covered-services either through managed care, on a fee-for-service basis, or through a combination of these delivery systems.

[18]See, for example, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Medicaid and CHIP Managed Care Monitoring and Oversight Tools (Baltimore, Md.: June 28, 2021).

[19]States are required by law to report annually to HHS the number of eligible children provided child health screening services, the number of eligible children referred for corrective treatment, the number of eligible children receiving dental services, and states’ results in attaining EPSDT participation goals established by the department. States must submit data to CMS by April 1 for the prior fiscal year’s reporting. Beginning in 2021, states could opt to have CMS complete their annual submission of the CMS-416 using data from the Transformed Medicaid Statistical Information System. According to CMS officials, for fiscal year 2023, 31 states, the District of Columbia, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands opted to have CMS generate CMS-416 data. See 42 U.S.C. § 1396a(a)(43).

[20]See Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment,” accessed Feb. 5, 2025, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/benefits/early-and-periodic-screening-diagnostic-and-treatment/index.html; and GAO, Medicaid: Additional CMS Data and Oversight Needed to Help Ensure Children Receive Recommended Screenings, GAO‑19‑481 (Washington, D.C.: Aug. 16, 2019).

[21]The Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2009 required HHS to identify and publish a core set of children’s health care quality measures for voluntary use by state Medicaid programs and Children’s Health Insurance Programs. See Pub. L. No. 111-3, § 401, 123 Stat. 8, 72 (codified as amended at 42 U.S.C. § 1320b-9a). As required by federal law, CMS released the final rule for Mandatory Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Core Set Reporting, which made annual Child Core Set reporting mandatory for fiscal year 2024 data.

[22]See Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Quality of Care for Children in Medicaid and CHIP: Findings from the 2023 Child Core Sets (December 2024). According to CMS, in 2023, the developmental screening measure showed the percentage of eligible children who turned 1, 2, or 3 years of age during calendar year 2022 and who were screened for risk of developmental, behavioral, or social delays using a standardized screening tool. In total, 43 states reported data on the measure.

[23]We previously recommended that CMS develop a plan for using Transformed Medicaid Statistical Information System data to generate the necessary data from the Child Core Set. See GAO‑19‑481. As of February 2025, CMS stated the agency continues to assess the feasibility of extracting Child Core Set data for selected quality measures using Transformed Medicaid Statistical Information System data.

[24]According to state documentation, Rhode Island continues to collect data from managed care plans for various quality measures. However, the state’s financial incentive program does not include quality measures for well-child screenings or treatment for eligible children.

[25]Performance measurement is the ongoing monitoring and reporting of program accomplishments, particularly progress toward pre-established goals. It involves identifying performance goals and measures, including establishing performance baselines and tracking performance over time; identifying quantifiable, numerical targets for improving performance; and measuring progress against those targets.

[26]A withhold arrangement is any payment mechanism under which a portion of a capitation payment is withheld from a managed care plan, and a portion of or all of the withheld amounts will be paid for meeting targets specified in the managed care plan’s contract. 42 C.F.R. § 438.6(a).

[27]The program also includes components related to adult quality measures. Payments are based on the overall progress toward meeting performance goals, as well as other collaborative state-wide initiatives.

[28]See Washington Apple Health, 2024 EQR Annual Technical Report (Seattle, Wash.: January 2025).

[29]North Carolina transitioned to a managed care delivery system for Medicaid on July 1, 2021, and launched its incentive program in 2024. The first performance period for the program was January 2024 to December 2024, and the state plans to provide data on withholds to managed care plans in early 2026.

[30]The education, support services, and incentives offered to EPSDT-eligible children were frequently directed to their caregivers who make decisions about children’s receipt of health care services.

[31]CMS requires states to inform eligible children and their caregivers about EPSDT, including information about the benefits of preventive health care, the services available under EPSDT, and how to obtain them. 42 C.F.R. § 441.56(a) (2024). Medicaid managed care plans are required to provide handbooks to beneficiaries that outline coverage, services, and how to access care for all individuals covered under the plan. This includes information on EPSDT services available to eligible children. 42 C.F.R. § 438.10(g).

[32]In 2022, CMS hired a contractor, NORC at the University of Chicago, to research EPSDT, including reviewing states’ beneficiary handbooks, and conduct research activities from fiscal year 2023 through 2027, including producing a report due to Congress in accordance with the 2022 Bipartisan Safer Communities Act. See Pub. L. No. 117-159, § 11004(a)(2), 136 Stat. 1313, 1320 (2022). State Medicaid officials in Rhode Island told us they recently revised language explaining EPSDT and have worked to ensure managed care plans in their state use this standardized language when describing EPSDT in their beneficiary handbooks. The state took this action in response to the findings from NORC’s review. Furthermore, according to state Medicaid officials in Ohio, managed care plans obtain approval from the state Medicaid agency before making changes to handbook materials to ensure consistency.

[33]According to some stakeholders, eligible children and their caregivers may not fully understand the importance of well-child screenings, particularly for seemingly healthy children, and may be unaware of the services available to them under EPSDT. Additionally, according to NORC’s review, handbooks are often written at reading levels that may be challenging for eligible children and their caregivers to understand.

[34]We found that some managed care plans also encouraged providers to send reminders to eligible children and their caregivers. For example, officials at a managed care plan in Washington said they distribute information to providers on how to identify upcoming or missed well-child appointments within their patient registries and send appointment reminders.

[35]Officials said that the text messages during the back-to-school period, in addition to other efforts—social media updates, educational materials, and incentives—have had positive effects on well-child screening rates.

[36]According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, the human papillomavirus vaccination is part of well-child screenings and recommended between 9 and 12 years of age to protect against human papillomavirus infections, as well as cancers caused by the virus.

[37]CMS requires states to offer eligible children certain supports, such as assistance with scheduling appointments for services or transportation assistance to appointments, as may be necessary. 42 C.F.R. § 441.62 (2024). CMS’s September 2024 guidance identified best practices, such as offering a phone number that eligible children and their caregivers can call to obtain assistance with finding providers or scheduling appointments. Other best practices include being specific in contracts with managed care plans about expectations for conducting outreach and scheduling support. Additionally, some officials from managed care plans in Ohio and Rhode Island noted that supports can include assistance to address social determinants of health, vocational support, and access to community or social service resources.

[38]To receive a financial incentive, managed care plans generally required an eligible child to receive a periodic well-child screening or other service, such as obtaining an annual flu vaccination, according to plan documentation. Financial incentives could be in the form of gift cards, rewards points, or funds added to a health benefit card provided by the managed care plan, depending on the qualifying services the child received.

[39]The program included performance goals for improvements on the quality measure assessing the extent to which eligible children turned out for visits and completed well-child screenings. According to plan documentation, the managed care plan distributed a list of eligible children to providers that qualified to participate in the program, for example, by having a certain number of eligible children ages 3- to 11-years old. Managed care plans anticipated calculating performance and awarding providers in August 2025.

[40]According to CMS, some states have removed prohibitions on same day billing, which allows a provider to be paid for multiple services provided to the same eligible child on the same day, if these services are not duplicative. As a result, an eligible child would not be required to seek care elsewhere or return another day to receive services.