IMMIGRATION DETENTION

DHS Should Define Goals and Measures to Assess Facility Inspection Programs

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Rebecca Gambler at gamblerr@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107580, a report to Congressional Committees

DHS Should Define Goals and Measures to Assess Facility Inspection Programs

Why GAO Did This Study

ICE is responsible for providing safe, secure, and humane confinement for noncitizens in immigration detention facilities. In fiscal year 2024, ICE had an average daily population of over 37,000 detained noncitizens at over 100 facilities owned and operated by ICE or private, state, or local entities.

The explanatory statement accompanying the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2024, includes a provision for GAO to review DHS entities responsible for inspections of immigration detention facilities. This report (1) describes the DHS entities that have conducted inspections and the processes used, (2) examines the results of inspections regarding compliance with detention standards, and (3) analyzes the extent to which DHS entities have assessed their detention facility inspection programs. GAO analyzed documents and data on inspections of facilities that held individuals for over 72 hours for fiscal years 2022 through 2024, and interviewed ICE and DHS officials and operators at selected facilities.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making three recommendations for DHS to establish goals and measures to assess facility inspections. DHS concurred with two recommendations. It did not concur with the third to ensure the Immigration Detention Ombudsman establishes goals and measures, noting that DHS is realigning responsibilities and issued Reduction in Force notices to OIDO employees. GAO maintains that DHS should establish goals and measures given the Ombudsman’s statutory oversight responsibilities related to detention facility inspections.

What GAO Found

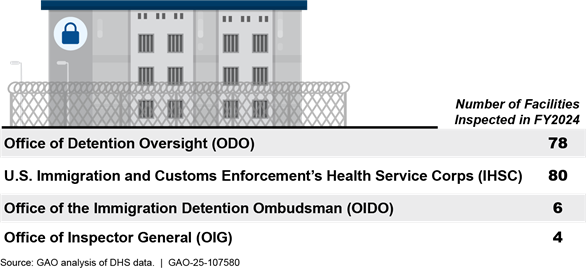

Four Department of Homeland Security (DHS) entities have conducted inspections of immigration detention facilities: (1) U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s (ICE) Office of Detention Oversight (ODO); (2) the ICE Health Service Corps; (3) DHS’s Office of the Immigration Detention Ombudsman (OIDO); and (4) DHS’s Office of Inspector General (OIG). Each of the four entities’ inspections have varied in terms of focus, purpose, and the number of inspections conducted each fiscal year.

Note: These data refer to inspections of facilities that detained noncitizens for more than 72 hours. ODO inspections include facilities that had an average daily population of 10 or more.

Inspections data from fiscal years 2022 through 2024 show that nearly all facilities received passing ratings but that the four inspections entities identified a range of deficiencies. ODO rated facilities as acceptable or above in 238 of 241 inspections during this period. But it found deficiencies related to, for example, environmental health and safety, such as water quality; and food service, such as sanitary conditions. The ICE Health Service Corps, which focuses on medical related standards, found that its staffed facilities complied with applicable detention standards in 46 of the 47 inspections, and common deficiencies related to medical care, safety, and sanitation. OIDO found that of the 33 facilities it inspected, 31 did not comply with the specific standard associated with the complaint or concern that led to the inspection. OIG identified deficiencies in the 12 inspection reports it published covering this period.

Three of the entities that have specifically focused on immigration detention facility oversight have had goals and measures for their facility inspection programs, such as measures related to the number of identified deficiencies or percentage of facilities inspected each year. However, they have not had goals that articulate target levels of performance to be accomplished and performance measures that track progress. Establishing goals and measures would provide insight into how effective detention facility inspection efforts are in achieving desired outcomes. This in turn would help better ensure that detained noncitizens are provided care that meets the standards for immigration detention.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

DHS |

Department of Homeland Security |

|

ICE |

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement |

|

IHSC |

ICE Health Service Corps |

|

ODO |

Office of Detention Oversight |

|

OIDO |

Office of the Immigration Detention Ombudsman |

|

OIG |

Office of Inspector General |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

May 21, 2025

The Honorable Katie Britt

Chair

The Honorable Chris Murphy

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Homeland Security

Committee on Appropriations

United States Senate

The Honorable Mark Amodei

Chairman

The Honorable Lauren Underwood

Acting Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Homeland Security

Committee on Appropriations

House of Representatives

Within the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) is the lead agency responsible for providing safe, secure, and humane confinement for detained noncitizens in the United States.[1] ICE’s fiscal year 2024 appropriation included $3.4 billion for the immigration detention system to support a detention bed level of 41,500.[2] According to ICE’s 2024 annual report, ICE had an average daily population of over 37,000 detained noncitizens in fiscal year 2024.[3]

According to ICE guidance, because the agency exercises significant authority when it detains noncitizens, ICE must do so in the most humane manner possible, focusing on providing sound conditions and care.[4] ICE has established standards for immigration detention that cover a variety of areas, including medical care, legal services, and grievance procedures.

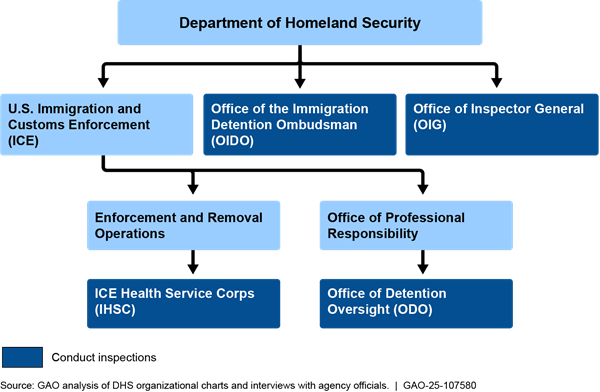

Various ICE and DHS offices and entities have had roles and responsibilities for overseeing ICE detention facilities and inspecting them to determine if they are meeting those standards. Within ICE, the Office of Professional Responsibility’s Office of Detention Oversight (ODO) has conducted inspections of each facility on a semiannual basis. The ICE Health Service Corps (IHSC), within Enforcement and Removal Operations, has overseen or provided health care services to all detained noncitizens in the facilities. Also, as part of IHSC’s oversight responsibilities, it has conducted inspections of immigration detention facilities with a focus on standards related to medical care. Within DHS, other entities that have had responsibilities related to inspecting immigration detention facilities include the Office of the Immigration Detention Ombudsman (OIDO), which reviews detention conditions, and the DHS Office of Inspector General (OIG).[5]

We have previously reported on ICE and other DHS entities’ oversight of immigration detention facilities. For example, in August 2020 we reported on ICE and other DHS entities’ mechanisms for overseeing compliance with facility standards and how ICE used oversight information to address any identified deficiencies.[6] We reported that ICE collected the results of its various inspections, such as information on identified deficiencies, but it did not comprehensively analyze the results to identify trends. ICE also did not record all inspection results in a format conducive to such analyses. We recommended that ICE ensure oversight data were recorded in a format conducive to analysis and regularly conduct trend analyses of these data. ICE concurred with our recommendations and has implemented them by capturing inspections results in a data system and conducting analyses of inspections results data.

The explanatory statement accompanying the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2024, includes a provision for us to review the policies and practices of DHS entities responsible for inspections at immigration detention facilities.[7] This report (1) describes the DHS entities that have inspected immigration detention facilities and the processes they have used, (2) examines the results of inspections regarding compliance with detention standards, and (3) analyzes the extent to which the DHS entities that have conducted these inspections have assessed the performance of their inspection programs. In appendix I of this report, we also discuss how ICE detention standards compare to the standards and guidelines of other federal entities with detained populations.

To address our three objectives, we focused our review on DHS entities that conducted inspections of immigration detention facilities that held detained noncitizens for over 72 hours from fiscal year 2022 through 2024.[8]

To describe the entities that have conducted immigration detention facility inspections, we identified entities within DHS that have had responsibilities for oversight of detention facilities and determined which of those entities have conducted inspections as part of their oversight efforts. The DHS entities we identified as having conducted inspections within the scope of our review were ODO, IHSC, OIDO, and the DHS OIG.

To identify the purpose, scope, process, and frequency of inspections regarding each of these entities, we reviewed applicable laws, policies and procedures, and guidance documents, such as inspection procedures and checklists. We reviewed ICE detention standards, which immigration detention facilities are expected to comply with and inspections are to follow.[9]

We interviewed officials from ODO, IHSC, OIDO, and the DHS OIG. We also interviewed officials from ICE Enforcement and Removal Operations, which has overseen confinement of detained noncitizens across facilities. In addition, we interviewed officials from DHS’s Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties. This office has received and responded to allegations of civil rights and civil liberties violations and abuses, including those related to immigration detention, by DHS personnel and contractors.[10]

With regard to detention facilities, we selected a non-generalizable sample of six over-72-hour immigration detention facilities and interviewed their operators regarding inspections in general and inspections conducted by the four DHS entities in particular.[11] We selected these facilities based on various factors, including:

· inspected by different entities (e.g., ODO, IHSC, OIDO, and DHS OIG);

· type (e.g., facilities owned and operated by ICE that house only detained noncitizens, and facilities owned by state or local governments that house detained noncitizens with other confined populations); and

· average daily population (e.g., facilities that have a range of population sizes of detained noncitizens).

The information we obtained from officials at these six facilities is not generalizable but provided perspectives on, and examples related to, detention facility inspections.

To examine what inspections have shown regarding compliance with the applicable detention standards, we obtained and analyzed DHS data for fiscal years 2022 through 2024 related to deficiencies identified by the inspection entities.[12] Specifically, we analyzed the data to determine any trends in inspection results, such as common deficiencies across immigration detention facilities. We also analyzed the data to determine the extent to which facilities developed and implemented corrective action plans to address identified deficiencies. We interviewed officials from the four DHS entities to obtain their perspectives on the results of inspections.

We assessed the reliability of the inspection data by reviewing documentation and interviewing officials knowledgeable about how the data were entered and maintained. In particular, we interviewed DHS officials regarding data integrity and controls over data systems, and we reviewed the data for errors and outliers. We determined the data were sufficiently reliable to describe the results of DHS’s inspections of immigration detention facilities.

To analyze the extent to which DHS entities have assessed the performance of their immigration detention facility inspection programs, we obtained and analyzed DHS documents such as strategic plans, annual performance reports, Congressional budget justification documentation, ICE’s detention standards, and policies and procedures. We focused our work on ODO, IHSC, and OIDO because these three entities have specifically focused on oversight of immigration detention facilities. While the DHS OIG’s work includes oversight of detention facilities, the OIG has generally focused on broader, departmentwide issues, not just oversight of detention facilities. We interviewed officials within the DHS entities to understand how, if at all, they have assessed the performance and effectiveness of their inspection programs. We compared the information we obtained to key practices of results-oriented performance management and Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government.[13] The Standards states that defining program goals in specific and measurable terms allows for the assessment of performance toward achieving objectives.

We conducted this performance audit from May 2024 to May 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Within DHS, ICE is responsible for providing safe, secure, and humane confinement for detained noncitizens who are charged as removable while they wait for resolution of their immigration court cases, or removal from the United States.[14] Noncitizens detained by ICE for violations of immigration law may include individuals with criminal and noncriminal backgrounds from a wide variety of countries. ICE owns and operates some facilities that it uses for detained noncitizens. Other detention facilities are owned and operated by private companies under contracts with ICE, or owned by state, local, or private entities and operated through intergovernmental service agreements with ICE. Some facilities exclusively hold ICE detained noncitizens, while others hold detained noncitizens with other confined populations, including those under the jurisdiction of the Department of Justice’s U.S. Marshals Service and the Federal Bureau of Prisons. In December 2024, ICE reported that it detained noncitizens in over 100 detention facilities.[15]

ICE Standards for Immigration Detention Facilities

ICE has developed standards for immigration detention that dictate how facilities should operate to ensure safe, secure, and humane confinement. ICE has updated or introduced new detention standards multiple times since they were initially developed in 2000, resulting in various versions—or “sets”—of standards that differ with respect to their scope, rigor, and other factors they incorporate. Contracts or agreements between ICE and detention facilities specify which set of standards facilities are required to follow. Table 1 summarizes the principal sets of detention standards applicable to over-72-hour immigration detention facilities.[16]

Table 1: U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) Detention Standards for Over 72-Hour Facilities

|

Detention Standards |

Description |

|

2000/2019 National Detention Standards |

These standards were derived from American Correctional Association standards and developed by the former Immigration and Naturalization Service within the Department of Justice in 2000. In December 2019, ICE issued the 2019 National Detention Standards, in which it condensed or eliminated several of the 2000 standards, such as those related to emergency plans, marriage requests, and contraband. In the 2019 update, ICE also streamlined certain detention standards, such as those pertaining to food service and environmental health and safety, and expanded others, such as those related to medical care, accommodations for disabilities, and sexual abuse and assault prevention and intervention. |

|

2008 Performance- Based National Detention Standards |

These standards are a revised version of the 2000 National Detention Standards that prescribe both the expected outcomes of each detention standard and the expected practices required to achieve them. |

|

2011 (Rev.2016) Performance-Based National Detention Standards |

These standards, and a successive revision in 2016, codified changes resulting from federal laws, DHS regulations, and ICE policies that had been established since the 2008 standards. Changes included those related to standards for sexual abuse and assault prevention and intervention, accommodations for disabilities, and language access. These standards also introduce provisions that represent optimal levels of compliance with the standards. |

Source: GAO analysis of ICE information. | GAO‑25‑107580

Note: ICE also has developed a set of detention standards to apply to facilities that house families in detention.

DHS entities that have conducted inspections of immigration detention facilities assess facilities’ compliance with these standards. Each set of detention standards cover a variety of different topics used to guide inspections. One of these ICE inspection entities—ODO, which has conducted semiannual inspections of each facility that serve as the facility’s inspection of record—has focused its inspections on a core set of standards that are intended to directly safeguard the life, health, and safety of detained noncitizens.[17]

Four DHS Entities Have Inspected Immigration Detention Facilities Using Varying Processes

DHS Inspection Entities

Four DHS entities have conducted inspections of immigration detention facilities: ODO and IHSC, within ICE, and OIDO and the DHS OIG.[18] Figure 1 illustrates the organizational structure of DHS entities with inspection responsibilities for ICE’s immigration detention facilities, as of fiscal year 2024.

Figure 1: Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Entities that Have Conducted Inspections of Immigration Detention Facilities, as of Fiscal Year 2024

In addition to these four inspection entities, ICE officials and the six facility operators we interviewed noted that immigration detention facilities can be subject to other types of inspections or investigations. For example, officials stated that DHS’s Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties has conducted investigations of alleged violations of civil rights and civil liberties by DHS components, including allegations involving ICE detention facilities. According to ICE officials, the Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties conducted 14 onsite investigations of ICE detention facilities in fiscal year 2024. After each investigation at an immigration detention facility, the office was to develop a memorandum with any recommendations and ICE’s response.

According to ICE officials, the investigations conducted by the Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties were similar to inspections, as the office may have investigated areas related to conditions of detention or environmental health and safety, for example. Additionally, according to an official within ICE’s Enforcement and Removal Operations, detention facilities were responsible for implementation of recommendations made by the Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties.

Immigration detention facilities have also been inspected by other entities. For example, as previously noted, some facilities that ICE has used to detain noncitizens also house individuals detained by the U.S. Marshals Service. In these instances, according to DOJ officials, facilities have been subject to inspections by both ICE and the U.S. Marshals. Additionally, according to DHS officials, state and local entities have inspected immigration detention facilities. In particular, a facility may have been inspected by local fire marshals or by a state corrections department. All six facility operators we spoke with stated that their facility has been inspected by entities outside of DHS, such as national correctional associations, the state corrections department, and a local fire marshal.

The facility operators we interviewed told us that inspections have benefits and challenges. For example, all six operators described benefits of inspections done by multiple entities, including helping the facility identify different areas that need improvement. Four of six operators, however, identified challenges related to this approach, noting that the facility must devote significant time and operational resources for each inspection.

DHS Inspection Processes

As shown in table 2, the four entities’ inspections have differed in various ways, including purpose and frequency.

Table 2: Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Entities that Conducted Inspections of Over-72-Hour Immigration Detention Facilities in Fiscal Year 2024

|

DHS entity |

Purpose and focus of inspections |

Frequency of inspections |

Types of inspection (announced or unannounced) |

Number of inspections in fiscal year 2024 (number of facilities inspected) |

|

Office of Detention Oversight (ODO) |

To inspect and rate facilities against the applicable detention standards for each facility. For over-72-hour facilities with an average daily population of 10 or more, ODO inspectors have focused their inspections on the 14 core standards and divided the non-core standards into two groups, inspecting facilities against them every other year.a Inspectors have documented their ratings, and these ratings represent each facility’s official rating against the applicable standards. These inspections represented the inspection of record for ICE and meet the congressional direction for ODO to conduct semiannual facility inspections.b |

Twice per year for each over-72-hour facility with an average daily population of 10 or more |

Announced and unannounced |

156 semiannual inspections (78 facilities with an average daily population of 10 or more) c |

|

ICE Health Service Corps (IHSC) |

To ensure facilities are adhering to medical standards. The inspections have focused on ICE’s standards that pertain to medical care. |

Annually or every other yeard |

Announced |

80 (15 IHSC-staffed facilities and 65 non-IHSC-staffed facilities)e |

|

Office of the Immigration Detention Ombudsman (OIDO) |

To address specific issue areas. The inspections have focused on selected issues identified by: OIDO staff; prior ODO or Office of Inspector General inspections or DHS’s Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties investigations; complaints made to OIDO; and referrals from other DHS entities. |

Ad hoc |

Announced and unannounced |

6 (6 facilities) |

|

DHS Office of Inspector General (OIG) |

To determine whether ICE detention facilities have been complying with select ICE detention standards. |

Ad hoc |

Unannounced |

4 (4 facilities)f |

Source: GAO analysis of DHS information and interviews with agency officials. | GAO‑25‑107580

aThe 14 core standards are those that are specifically related to health, life, and safety conditions for detained noncitizens. ODO inspectors have inspected each facility twice per year against these core standards. ODO has divided the remaining non-core standards into two groups and inspects facilities against each group every other year.

bThe inspection of record is the inspection compliance report that ODO has prepared at the conclusion of its first round of inspections of facilities each year. ODO has conducted the inspection of record consistent with the statutory responsibility of ICE’s Office of Professional Responsibility for performance evaluations of contracted detention facilities. These determine whether funds may be used to continue detention facility contracts. See Pub. L. No. 116-93, div. D, title II, § 215, 133 Stat. 2317, 2513 (2019) (classified at 6 U.S.C. § 211 note). ODO’s inspections have occurred on a semiannual basis as directed by the 2019 Joint Explanatory Statement, Conference Report accompanying H.J. Res. 31, H. Rep. No. 116-9, at 485 (Feb. 13, 2019).

cODO also has conducted inspections—called special reviews—of immigration detention facilities that have an average daily population of 1 to 9 noncitizens and that house noncitizens for longer than 72 hours, or have an average daily population of 1 or more noncitizens and house noncitizens for under 72 hours. According to ODO, during fiscal year 2024, ODO conducted 38 special reviews. According to ODO, these special reviews focused on approximately 10 standards related to the health, life, and safety of detained noncitizens (e.g. medical care, food service, and suicide prevention and intervention).

dAccording to IHSC officials, for facilities at which IHSC has directly provided medical care, IHSC inspections have occurred every year for the first 3 years and every other year thereafter. For those detention facilities at which medical care has been provided by local government or contract personnel, IHSC has conducted inspections annually.

eIHSC is responsible for overseeing or providing health care for all noncitizens detained in ICE custody. At some detention facilities, IHSC staff directly provide on-site medical care. At other facilities, non-IHSC staff (local government personnel or private contractors) provide this care and IHSC oversees the care.

fAccording to DHS OIG officials, the DHS OIG conducted four inspections and published two inspection reports in fiscal year 2024.

The four DHS entities have used various processes and procedures for conducting inspections of immigration detention facilities, as discussed below.

ODO

ODO has conducted semiannual inspections of immigration detention facilities that house detained noncitizens for over 72 hours with an average daily population of ten or more detained noncitizens.[19] By law, funds may not be used to continue any contract for detention services if the two most recent overall performance evaluations received by the contracted facility are less than “adequate” or the equivalent median score in any subsequent performance evaluation system.[20]

In particular, during the first semiannual inspection each year, ODO inspectors have assessed immigration detention facilities for compliance with the 14 core standards. They have done this to mitigate the agency’s risk and liability and, as previously mentioned, to identify issues related to the life, health, and safety of detained noncitizens. During the second inspection each year, ODO inspectors have assessed the corrective actions facilities took to address any deficiencies identified in ODO’s first inspection.

ODO has inspected each facility’s compliance with the non-core standards every other year. More specifically, ODO has inspected facilities using the core standards along with non-core standards for the first semiannual inspection each year. Although the 14 core standards have remained the same each year, the non-core standards have changed every other year. For example, in fiscal year 2024, ODO inspections focused on the 14 core standards, as well as a subset of 16 non-core standards, such as personal searches, personal hygiene, and the voluntary work program. For fiscal year 2025, ODO plans to inspect facilities against the 14 core standards and 15 non-core standards that were not included in the fiscal year 2024 inspections. ODO’s first inspections each year have focused on assessing facilities’ compliance with the core standards, and the second inspections have focused on facilities’ implementation of corrective actions. In addition, according to ODO officials, the office’s semiannual inspections have been both announced and unannounced, and ODO has conducted at least one unannounced inspection of each facility every 3 years.

ODO has conducted inspections in three phases—the pre-inspection phase, the inspection phase, and the post-inspection phase, according to ODO officials. During the pre-inspection phase for announced inspections, ODO has notified the facility and the relevant Enforcement and Removal Operations field office 4 weeks in advance of an upcoming inspection. For an unannounced inspection ODO has notified the facility on the Friday prior to the inspection, usually scheduled for the following Tuesday.

The inspection phase has taken place over 3 days with a team consisting of two to five ODO staff and two to four contractor subject matter experts. According to ODO guidance, each subject matter expert has been required to have a requisite number of years of operational experience in detention or corrections facilities in areas such as the provision of medical care, food services, or environmental health and safety. The inspection team has toured the facility, interviewed detained noncitizens and facility staff, and inspected the facility in accordance with the 14 core standards as well as the alternating non-core standards.

In conducting each inspection, the team has determined the standards to be inspected based on the contract signed by the facility. ODO has maintained worksheets that cover each standard which also provides space for the inspectors to record observations and actionable information, however, the worksheet is not a replacement for the standard. The worksheet has been used in conjunction with the applicable standard to assist the inspector in completing a thorough and objective inspection.

During the conclusion of the inspection, ODO’s inspection team typically has met with facility officials to provide an overview of the team’s findings. At the conclusion of the post-inspection phase and within 60 calendar days of the conclusion of the inspection, ODO has issued a final inspection report documenting any deficiencies found and providing a rating for the facility overall.[21] The report provides a summary of the inspection findings and any corrective actions the facility may have implemented during the inspection to address identified deficiencies. The results of ODO inspections serve as the official rating of record.[22] Altogether, the final report cites deficiencies, areas of concern, and corrective actions.

According to ODO officials, ODO has maintained a schedule of when it plans to conduct each initial and second inspection of immigration detention facilities. It has updated its schedule throughout the year for the following fiscal year, having shared this schedule with other DHS inspection entities such as IHSC, OIDO, and the DHS OIG.

IHSC

IHSC is responsible for providing medical care for detained noncitizens at some detention facilities and overseeing medical care across all facilities.[23] At some detention facilities, IHSC staff directly provide on-site medical care. At other facilities, non-IHSC staff (private contractors) provide this care and IHSC ensures that the medical care meets detention standards. In fiscal year 2024, IHSC staff provided on-site medical care at 15 IHSC-staffed facilities and oversaw medical care at 80 non-IHSC-staffed detention facilities.

According to IHSC officials, for IHSC-staffed facilities, IHSC staff have inspected facilities every year for 3 years, before transitioning to inspections every other year based on the findings of those initial inspections.[24] For non-IHSC-staffed facilities, IHSC staff have inspected them annually. These officials stated that prior to conducting inspections, IHSC inspectors have conducted clinical chart reviews of a random sample of medical records at each facility. Furthermore, officials stated that, in conducting inspections, a two-person team—one clinical inspector and one operations inspector—has observed clinical and administrative processes of the facility on-site, and interviewed facility staff.

According to officials, IHSC inspection teams have used the medical standards within the overall set of detention standards applicable to each facility to assess a facility’s compliance. Four to six weeks prior to an inspection, IHSC has informed the facility via email. Officials stated that during the inspection, the team has observed onsite health conditions and health care delivery systems, processes, and outcomes to assess and document a facility’s compliance with the applicable standards. At the conclusion of inspections, IHSC has provided the facility with an overall score and recommendations to address compliance issues, according to IHSC officials.[25] Two of the six facility operators we interviewed stated that IHSC’s inspections more comprehensively reviewed the provision of health care than inspections by ODO. IHSC officials stated that facilities are asked to develop corrective actions to address any findings and recommendations to address compliance issues identified in IHSC inspections.

OIDO

In December 2019, the position of Immigration Detention Ombudsman was established by statute and in 2020, OIDO was formed.[26] The statutory functions of the Immigration Detention Ombudsman include, among other responsibilities, conducting unannounced inspections of detention facilities holding individuals in federal immigration custody, including those owned or operated by units of state or local government and privately-owned or operated facilities; and reviewing, examining, and making recommendations to address concerns or violations of contract terms identified in reviews, audits, investigations, or detainee interviews regarding immigration detention facilities and services.[27] The Ombudsman’s statutory functions also include receiving, investigating, and resolving detention-related complaints. According to DHS officials, OIDO was dissolved and is no longer operating as of March 2025.[28]

In conducting inspections of immigration detention facilities, an OIDO official stated that the office was not required to inspect a set number of facilities each year or use specific criteria for selecting a facility for inspection. OIDO officials told us that the office decided to inspect a facility based on a trend or issue identified by (1) information obtained internally by OIDO staff, (2) previous ODO or DHS OIG inspections or DHS Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties investigations, or (3) complaints received by OIDO or referrals from other DHS entities.

While tailored to the specific facility and the issue (e.g., medical care, food service) that triggered the inspection, OIDO’s inspections followed a multi-stage process, beginning with the intake of submitted referrals. Next, officials stated OIDO prepared a proposal that involved reviewing and evaluating prior inspections, such as those conducted by other DHS offices, and considered the applicable standards the facility is required to follow. According to officials, OIDO then conducted research relating to the specific facility or issue under review by analyzing news searches and cases that had been referred and are related to conditions of immigration, and by gathering any compliant information OIDO had received. Based on this work, OIDO created an outline of key topics, developed a workplan, and proceeded with the onsite inspection.

The work plan and inspection checklist were designed to review the issue at a facility and to help OIDO assess evidence of compliance. The work plan identified the areas of review and OIDO team members were assigned specific areas to review. The inspection checklists guided the on-site inspections, helping to assess evidence of compliance, and assisting the team in conducting a thorough, systematic, and consistent inspection. At the conclusion, OIDO drafted an inspection report summarizing its findings, conclusions, and any recommendations and shared the report with the facility. The facility has 60 days to comment on any recommendations.[29]

According to OIDO officials, OIDO met with ICE and other DHS entities to coordinate inspections and minimize overlap.[30] According to these officials, OIDO could cancel or postpone an inspection if a conflict existed with another inspection entity’s schedule. OIDO officials stated that while OIDO worked to deconflict with other components early in its scheduling process, if a scheduling conflict arose, OIDO generally deferred to other offices conducting inspections and cancelled or delayed its inspection. For example, OIDO had rescheduled several inspections due to schedule conflicts with DHS’s Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties investigations. According to OIDO officials, in fiscal year 2024, OIDO conducted six inspections of ICE immigration detention facilities.

DHS OIG

Under its broad statutory authority, DHS OIG has conducted unannounced inspections of immigration detention facilities to ensure compliance with detention standards.[31] DHS OIG officials stated that any of the facilities that ICE owns or contracts with could be subject to an inspection. According to DHS OIG officials, the DHS OIG has selected four to six facilities to inspect each year. When determining the facilities to inspect, DHS OIG officials stated they have reviewed inspection findings from ICE (e.g., ODO findings) and other DHS entities and any complaints the DHS OIG has received about specific facilities. Although DHS OIG inspections have been unannounced, officials stated the office has coordinated with other DHS components to avoid conducting simultaneous inspections.

According to DHS OIG officials, inspection teams have been comprised of four to six inspectors depending on the size of the facility, as well as a doctor and nurse provided by a contracted entity. Teams have provided facilities with 30 minutes of advance notice before the inspection begins. Each inspection has spanned approximately 3 days and began with a walkthrough of the facility, according to these officials, and the teams have typically been focused on a subset of the detention standards that were applicable to the facility being inspected. In particular, officials stated that their inspections have primarily focused on standards related to health and sanitation, food service, and segregated housing. But they noted that teams have reviewed compliance with any of the applicable detention standards as part of their inspections. Inspection teams have used a checklist focused on the specific areas included in the scope, but they have also addressed any observed issues outside the checklist. Officials stated that inspection teams also have interviewed ICE field office officials, facility staff, and detained noncitizens.

Officials added that approximately 90 days after completing the on-site inspection, inspection teams have summarized their findings in a Notice of Findings and Recommendations and submitted the Notice to ICE headquarters, which has 10 business days to provide technical comments. Furthermore, these officials stated that these comments have been incorporated into the final report, which is signed by the Inspector General and published on the DHS OIG’s website.

Most Facilities Received Passing Ratings, but Inspections Identified Deficiencies

ODO Rated Nearly All Facilities as Acceptable or Above, but Identified Deficiencies Across Standards

ICE has collected information on the results of ODO inspections, including deficiencies identified and corrective actions taken to address those deficiencies. It also has collected information on each facility’s rating from an inspection: superior, good, acceptable, or failure. ICE has maintained this information in its Inspection Management System database. ICE has considered a rating of acceptable or higher as indicating that, if deficiencies existed, they have not detracted from the facility’s operation. According to ODO’s operation manual, a rating of superior indicates a facility’s high level of compliance with applicable detention standards. As a result of semiannual inspections performed in fiscal year 2022, ODO rated 83 of 85 facilities as acceptable or above.[32] In fiscal year 2023 and fiscal year 2024, ODO rated 77 of 78 facilities and 78 of 78 facilities as acceptable or above, respectively.[33]

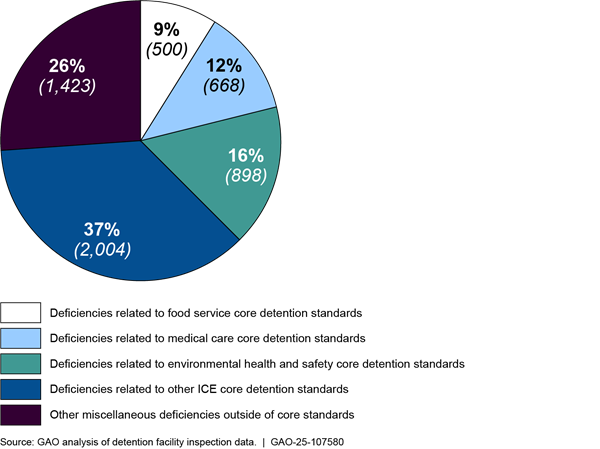

While nearly all detention facilities received a rating of acceptable or higher, ODO identified a number of deficiencies in these inspections for fiscal years 2022 through 2024. Specifically, ODO identified 5,493 deficiencies in its 477 inspections of immigration detention facilities over these fiscal years. As shown in figure 2, deficiencies related to ICE’s 14 core detention standards—which include environmental health and safety, medical care, and food service standards—accounted for approximately 74 percent of the total deficiencies.[34] The remaining 26 percent of deficiencies ODO identified were other miscellaneous deficiencies outside of the core detention standards. These included deficiencies related to standards such as correspondence and other mail, facility security and control, and transportation. As previously noted, in conducting each inspection, ODO inspection teams have used a standard worksheet to identify line item deficiencies. Line items have represented smaller components of an overall detention standard, and facilities have received deficiencies for individual line items without receiving a deficiency on the standard overall.

Figure 2: Number and Type of Deficiencies at Immigration Detention Facilities as Reported by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s (ICE) Office of Detention Oversight, Fiscal Years 2022 through 2024

Note: ODO performed 477 detention facility inspections from fiscal year 2022 through fiscal year 2024 based on its 14 core detention standards. The 14 core detention standards include environmental health and safety (shown in the figure), medical care/health care and medical care (women)/health care (combined under medical care as shown in the figure), and food service (shown in the figure). Violations of the remaining 10 core detention standards are captured under the “other core detention standards” in the figure and are as follows: emergency plans, admissions and release, custody classification system, funds and personal property, use of force and restraints, special management units, significant self-harm and suicide prevention and intervention, staff-detainee communication, grievance system, and sexual abuse and assault prevention and intervention. ICE’s detention standard for environmental health and safety covers a wide variety of requirements for facilities, including those related to general environmental health and hygiene, training for staff and detainee safety, general housekeeping, control of pests and vermin, water quality, hazardous materials, and other concerns. Other miscellaneous deficiencies outside of the core detention standards related to standards such as correspondence and other mail, facility security and control, and transportation.

To address deficiencies identified by ODO inspectors, facilities have engaged in corrective actions. According to ODO officials, facilities are obligated, by contract or agreement, to correct all deficiencies identified during ODO inspections. ODO officials said that examples of corrective actions include a facility providing training to staff or detained noncitizens, providing guidance via policy or memorandum, or instituting an internal self-audit program. Specifically, for the 5,493 deficiencies identified by ODO inspectors in fiscal years 2022 through 2024, the detention facilities engaged in a total of 3,642 corrective actions.[35]

During inspections conducted during fiscal years 2022 through 2024, ODO also identified 348 “areas of concern” outside of the detention standards the facilities are required to follow.[36] According to ODO, its inspectors may identify additional areas of concern that might affect facility operations. According to ODO in its fiscal year 2023 annual report, these additional issues may still pose a risk to detainee life, health, safety, or detention center operations. Further, according to ODO, areas of concern may involve issues that run contrary to industry-accepted practices, or that may conflict with standards developed by other government agencies or other national certifying bodies and non-governmental organizations.[37] In addition, areas of concern may involve ICE detention standards a particular facility is not obligated by contract or agreement to follow. For example, in fiscal year 2023, ODO identified 120 areas of concern related to the ICE standard on sexual abuse and assault prevention and intervention, since many facilities inspected were not required to comply with this standard at the time of their inspections.

ODO added that it has not required detention facilities to resolve these areas of concern since they are not among the detention standards the facilities are required to follow. However, ODO has brought these issues to the facilities’ attention so that the facility can use the information to mitigate any potential risks to health, life, and safety of the detained population.

IHSC Inspections Found Overall Compliance with Standards, but Identified Deficiencies

IHSC has also collected and maintained data on the results of its inspections. IHSC conducted 47 inspections of IHSC-staffed detention facilities and 238 annual inspections of non-IHSC facilities from fiscal years 2022 through 2024. During that time, the number of IHSC-staffed facilities decreased from 17 in fiscal year 2022 to 15 in fiscal year 2024.

IHSC’s inspections during fiscal years 2022 through 2024 indicated that IHSC-staffed immigration detention facilities complied with applicable ICE detention standards in 46 of the 47 inspections.[38] According to IHSC officials, when their inspectors have rated a facility as having met standards, it means that the facility received a passing score of 80 percent or higher on its inspection. A score of 79 percent or lower means the facility failed its inspection.

IHSC identified a total of 134 deficiencies during the 47 inspections of IHSC-staffed facilities it conducted during this period. Eighty-eight percent of these deficiencies were related to medical care, and the remaining 12 percent were related to other detention standards such as safety and sanitation. According to IHSC officials, their inspectors also have reviewed issues concerning the environment surrounding the provision of medical care, which can result in deficiencies not directly related to medical care. For example, IHSC inspectors may review whether medical care is provided in a clean and safe environment. This may result in deficiencies identified that are not directly related to medical issues, such as safety and sanitation.

The most prevalent medical deficiencies identified in IHSC inspections of IHSC-staffed facilities included those related to chronic care (13 percent) and suicide watch (10 percent). The most common deficiency IHSC identified outside of its primary focus on medical issues concerned violations of standards governing safety and sanitation (7 percent). As of November 2024, IHSC inspectors reached agreement with the facilities for corrective actions to address all 134 deficiencies.

With regard to non-IHSC staffed facilities, IHSC inspectors found that facilities were 100 percent compliant with ICE medical standards in the majority (63 percent) of the 238 annual inspections they conducted from fiscal year 2022 through fiscal year 2024. According to IHSC officials, the most common deficiencies for non-IHSC staffed facilities stemmed from (1) meeting requirements for annual training for non-IHSC facility staff, (2) meeting contract and staffing requirements, and (3) meeting timeline requirements for examinations of noncitizens—such as conducting comprehensive health assessments within 14 days of a noncitizen’s placement in the facility. IHSC officials stated that, as a result of their inspections, the non-IHSC staffed facilities implemented 94 corrective action plans to bring their operations into compliance with ICE medical standards.

OIDO Inspections Found Noncompliance with Selected Detention Standards

From fiscal year 2022 through fiscal year 2024, OIDO performed 31 inspections of ICE immigration detention facilities and found that most facilities did not comply with the specific detention standards that were the focus of each inspection. As previously mentioned, OIDO has performed inspections typically in response to a complaint or specific concern. Therefore, OIDO’s inspections have often focused on areas already identified as concerning, which have made them different from other entities’ inspections such as those performed by ODO. OIDO inspectors found that two of 31 facilities were in compliance with the specific standards reviewed. Furthermore, OIDO identified 174 deficiencies in its inspections of the remaining 29 facilities where they found non-compliance with the detention standards that were the subject of the inspections.

The most prevalent deficiency OIDO found in these inspections involved standards for medical care for detained noncitizens, which accounted for 48 percent of the deficiencies identified from fiscal years 2022 through 2024. After medical care, the most prevalent deficiencies related to environmental health and safety and staff-detainee communication—accounting for 8 percent and 5 percent, respectively, of the deficiencies during the period. OIDO also identified other types of deficiencies, which each accounted for 5 percent or less of all deficiencies during these fiscal years. These other categories of deficiencies included such areas as food service, staff training, and use of force and restraints.

According to OIDO officials, detention facilities could address a deficiency when it was identified by OIDO inspectors or prior to publication of the inspection report. The published inspection reports have included recommendations related to any remaining deficiencies that were not resolved prior to the reports’ publication. From fiscal year 2022 through fiscal year 2024, OIDO made 68 recommendations to ICE for facilities to address unresolved deficiencies identified by OIDO inspectors. OIDO made 44 of these recommendations in fiscal year 2024. According to the 2024 OIDO operations manual, ICE was to provide a plan for addressing each recommendation from an OIDO inspection of an ICE detention facility.[39]

DHS OIG Found a Variety of Deficiencies in its Inspections of 12 Detention Facilities

From fiscal year 2022 through fiscal year 2024, the DHS OIG published 12 reports on inspections of detention facilities. In these reports, the DHS OIG identified 155 deficiencies covering 19 separate categories and resulting in 106 recommendations for improvements.[40] According to DHS OIG officials, ICE has either implemented these recommendations or developed corrective action plans to address them.

The most prevalent deficiencies identified by the DHS OIG related to medical care (38), staff-detainee communication (32), and grievance procedures (20), which collectively accounted for 90 of 155 deficiencies (58 percent). The remaining deficiencies during this period were in categories with eight or fewer deficiencies. These categories included access to legal resources, environmental health and safety, and use of force and restraints.

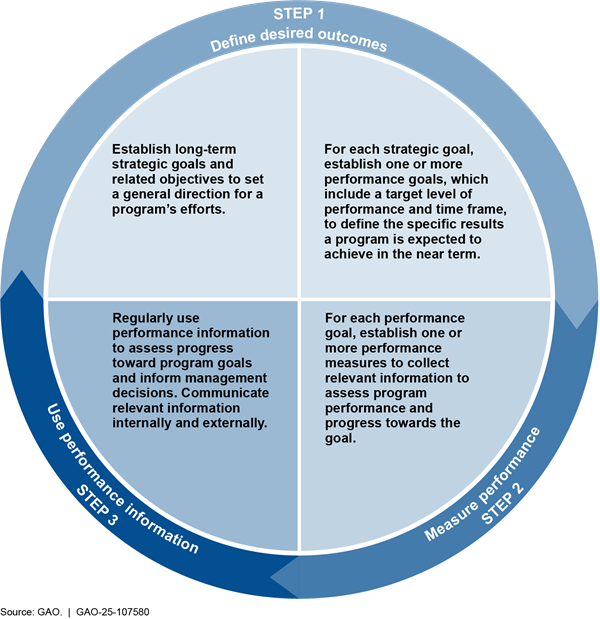

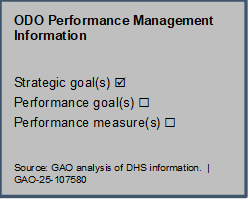

DHS Entities Have Not Assessed Their Detention Facility Inspection Programs

ODO, IHSC, and OIDO have not assessed their respective detention facility inspection programs using the key practices of results-oriented performance management. Identifying strategic goals, performance goals, and performance measures are important steps in managing the performance of federal programs. In our prior work, as shown in figure 3, we have described results-oriented performance management as a three-step process by which organizations (1) define desired outcomes—or strategic goals—and identify the results the program is intended to achieve—or performance goals, (2) measure performance by collecting information, and (3) use performance information to assess progress and inform decisions as well as communicate information externally.[41]

Additionally, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that defining program goals in specific and measurable terms allows for the assessment of performance toward achieving objectives.[42]

We found that ODO, IHSC, and OIDO have followed some components of performance management. However, none of these entities have had the combination of all three key components described above—results-oriented strategic goals, performance goals that have articulated target levels of performance, and performance measures that have tracked progress.

Strategic goals are an outgrowth of the mission, and explain what results are expected from the program’s major functions and when to expect those results. An example of a strategic goal that indicates a desired outcome for an inspection program would be ensuring that immigration detention facilities are humane and safe. Performance goals describe a target level of performance expressed as a tangible, measurable objective against which actual achievement is to be compared. An example of a performance goal would be aiming for 100 percent of identified deficiencies in a year to be resolved through corrective actions by the end of the next fiscal year. Finally, performance measures are the specific pieces of information that track whether the performance goal is achieved. An example of a performance measure would be the percentage of identified deficiencies that are resolved through corrective action.

ODO. ODO has not established performance goals and performance measures for assessing the inspection program’s progress in meeting its strategic goal. ODO officials told us that the strategic goal of the inspection program has been to ensure the health, life, safety, and welfare of detained individuals. This is a strategic goal because it articulates the desired outcome for ODO’s inspection program.

Officials told us that ODO has worked to achieve this strategic goal by conducting semiannual inspections of all over-72-hour facilities each year, rating each facility based on those inspections, and publicly posting all inspection reports within 60 days of the inspection completion date. These are inspection activities, but they are neither performance goals or performance measures because they do not describe how the inspection program will reach this desired outcome or how it will measure its progress. Performance goals identify detailed target levels of performance for how the inspection program will reach its desired outcome, and performance measures track the program’s ability to achieve its performance goals and ultimately, its strategic goals. For example, posting inspection reports within 60 days describes an activity, but it does not provide the specific performance information needed to assess progress toward ODO’s goal to ensure the health, life, safety, and welfare of detained individuals.

ODO officials acknowledged that they have not developed

performance goals or performance measures for assessing and managing ODO’s

inspection program. The reason they gave for this was that, although the

desired outcome of the inspections is to ensure the health, life, and safety of

detained individuals, ODO is not responsible for day-to-day management of

immigration detention facilities. The officials stated that they believe ODO

cannot identify performance goals when they are not responsible for the conditions

at individual facilities. However, in implementing components of performance

management, agencies often identify performance goals that may involve a topic

or objective that is affected by factors beyond the agency’s direct control.[43] Agencies may develop strategies to

leverage or mitigate the effects of external factors on the accomplishment of

strategic and performance goals. In this case, ODO could identify performance

goals and measures to track the program’s progress in achieving its strategic

goal to ensure the health, life, safety, and welfare of detained individuals

while acknowledging those factors and other agencies that influence that goal.

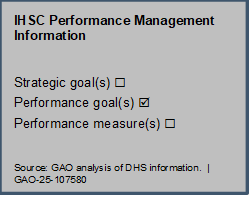

IHSC. IHSC has not established strategic goals or performance measures for its inspection program. IHSC officials told us its inspection program has aimed to ensure that 100 percent of IHSC-staffed facilities and at least 80 percent of non-IHSC-staffed facilities are inspected each year. This can be considered a performance goal because it identifies a specific performance target and timeframe. However, to be useful, performance goals should be linked to and support a program’s strategic goal—which IHSC does not have.

IHSC officials told us that they have not developed strategic goals or performance measures for their inspection program because until recently they did not have the data or a data collection tool that provided the information they need to develop appropriate goals and measures. However, in 2024, IHSC implemented its Quality Review Program review tool, which collects information related to facilities’ medical policies and procedures. With this information, IHSC can analyze data across facilities of all types, including IHSC-staffed facilities or non-IHSC-staffed facilities, according to IHSC officials. For example, the tool is intended to help IHSC analyze the number of deficiencies related to medical standards across facilities, or from year to year. Such information could assist IHSC in identifying goals and measures.

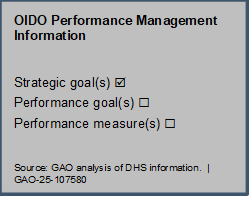

OIDO. OIDO described strategic goals and objectives related to its inspections in its 2022-2024 Strategic Plan.[44] For example, the plan included a strategic goal to identify, develop, and deliver recommended solutions to improve conditions within immigration detention facilities. In support of this goal the plan included related objectives, such as the full deployment of detention oversight staff and capabilities in the field. The plan also included initiatives in support of the objectives, such as establishing risk-based assessment of detention facilities for oversight and inspection. Although the plan had a strategic goal and supporting objectives related to oversight of detention facilities, the plan did not have performance goals or performance measures to track the inspection program’s performance toward achieving the strategic goal.

OIDO officials told us that because OIDO was established by statute in 2019 and DHS formed it as an office in 2020, it was too new to have goals or performance measures related to its inspection program. However, OIDO created a strategic plan and program plans in 2021, but did not identify a plan for how it was going to track its inspection program’s progress in achieving desired outcomes.

ODO and IHSC have an opportunity to develop or improve the goals and measures they use for their inspection programs. For example, ODO officials also told us that ICE’s Office of Professional Responsibility, of which ODO is a component, is currently working on updating its strategic plan and intends to include goals as well as performance measures to track ODO’s progress in achieving its goals. After IHSC develops strategic goals, performance goals, and performance measures, it can use its new inspection tool to collect data to measure progress toward achieving its goals. Prior to the dissolution of OIDO in March 2025 that DHS noted in its comments on our draft report, OIDO officials told us that they had hoped to establish goals and performance measures for their inspection program when updating their strategic plan in 2025.

Establishing strategic goals and performance goals and measures would allow each entity to gain insight into how effective its detention facility inspection efforts are in achieving their desired outcomes. Strategic goals supported by appropriate performance goals and measures would also allow DHS inspection entities to assess the overall performance of each of the respective inspection efforts. As a result, DHS and ICE leaders and managers would be better positioned to make well-informed decisions to manage and adjust inspection activities and use resources effectively, as well as communicate information externally (to Congress for example). This in turn would help better ensure that detained noncitizens are provided care that meets the standards for immigration detention facilities.

Conclusions

DHS entities have inspected immigration detention facilities to determine facilities’ compliance with detention standards. Some of these entities—ODO, IHSC, and OIDO—have not established some of the key practices of results-oriented performance management, such as developing performance goals and measures, that could help better assess their inspection programs. Developing and implementing performance goals and measures would provide officials with the information they need to assess the overall performance of their inspection efforts. Using this information, DHS and ICE would then be able to make informed decisions about their inspections of immigration detention facilities and communicate to Congress about their use of resources. As ODO develops its updated strategic plan, IHSC begins to collect additional inspection data through its inspection tool, and DHS determines how it will continue to conduct the legally required functions of OIDO while realigning responsibilities, DHS and ICE would benefit from instituting a performance management system and beginning to assess and adjust inspection programs to achieve desired outcomes. This, in turn, would help better ensure that immigration detention facilities are providing safe, secure, and humane confinement for detained noncitizens.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following three recommendations:

The Director of ICE should develop and implement performance goals and measures to assess the performance and effectiveness of ODO’s program for inspecting immigration detention facilities. (Recommendation 1)

The Director of ICE should develop and implement strategic goals and performance measures to assess the performance and effectiveness of IHSC’s program for inspecting immigration detention facilities. (Recommendation 2)

The Secretary of Homeland Security should ensure that the Immigration Detention Ombudsman develops and implements performance goals and measures to assess the performance and effectiveness of its inspections of immigration detention facilities. (Recommendation 3)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to DHS and DOJ for their review and comment. DHS provided written comments, which are reproduced in appendix II. In its comments, DHS concurred with the first two recommendations and described planned actions to address them by the end of 2025. It did not concur with the third recommendation, as discussed below. Both DHS and DOJ provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

With regard to the first recommendation that the Director of ICE should develop and implement performance goals and measures to assess the performance and effectiveness of ODO’s program for inspecting immigration detention facilities, DHS concurred and stated ODO and ERO will establish program performance goals and measures. For example, DHS noted that ODO will provide the ICE Enforcement and Removal Operations Executive Associate Director a quarterly report that outlines trends in detention standards that impact life, health, and safety concerns, to illustrate each facility’s performance over time. DHS also noted that ERO will ensure corrective action plans are generated for inspection results and submitted to the appropriate Enforcement and Removal Operations Field Office Director for action.

DHS also agreed with the second recommendation, that the Director of ICE should develop and implement strategic goals and performance measures to assess the performance and effectiveness of IHSC’s program for inspecting immigration detention facilities. DHS stated that IHSC will develop strategic goals and performance measures as well as create a dashboard to provide for enhanced tracking and trends of inspection findings.

DHS did not concur with the third recommendation in our draft report that the Secretary of Homeland Security should ensure that the Immigration Detention Ombudsman develops and implements performance goals and measures to assess the performance and effectiveness of its program for inspecting of immigration detention facilities. According to DHS officials, OIDO was dissolved and is no longer operating as of March 2025. In its comments, DHS noted that Reduction in Force notices were issued to OIDO employees as DHS leadership realigns responsibilities they deem necessary and appropriate to be in line with the agency’s mission. DHS stated that all legally required functions of OIDO will continue to be performed. However, DHS did not explain how the Ombudsman’s statutory functions would continue to be carried out with the dissolution of OIDO. DHS requested that we consider this recommendation resolved and closed.

We maintain that DHS should ensure the development and implementation of performance goals and measures for the Immigration Detention Ombudsman’s inspections of immigration detention facilities. The statutory functions of the Immigration Detention Ombudsman include, among other responsibilities, conducting unannounced inspections of detention facilities holding individuals in federal immigration custody, including those owned or operated by units of state or local government and privately-owned or operated facilities; and reviewing, examining, and making recommendations to address concerns or violations of contract terms identified in reviews, audits, investigations, or detainee interviews regarding immigration detention facilities and services.

Given DHS’s stated commitment to continue to carry out the Ombudsman’s statutory oversight responsibilities, it should establish performance goals and measures for those activities, regardless of the size or structure of the organization carrying out those activities. As we noted in our report, with information on performance and effectiveness, DHS and ICE leaders and managers would be better positioned to make well-informed decisions to manage and adjust inspection activities and use resources effectively, as well as communicate information externally, such as to Congress. This in turn would help better ensure that detained noncitizens are provided care that meets the standards for immigration detention facilities. Given DHS’s dissolution of OIDO, we adjusted this recommendation to make clear it refers to the Ombudsman’s statutory responsibility for facility inspections. We also added information throughout our report to reflect DHS’s comments on the status of OIDO.

We are providing copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, Secretary of Homeland Security, the Attorney General, and other interested parties. In addition, the report will be available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions, please contact me at gamblerr@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made significant contributions to this report are listed in appendix IV.

Rebecca Gambler

Director, Homeland Security and Justice

Appendix I: Comparison of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement Core Detention Standards to U.S. Marshals Service and Federal Bureau of Prisons Standards

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), the U.S. Marshals Service, and the Federal Bureau of Prisons are federal agencies responsible for individually managing detained populations. There are differences between ICE civil immigration detention, U.S. Marshals pre-sentence criminal custody, and Bureau of Prisons imprisonment under a sentence imposed after criminal conviction.

Under the immigration enforcement system, individuals who are charged as removable while they wait for resolution of their court cases, or removal from the United States may be subject to non-punitive detention. Such detention is designed to facilitate their attendance at removal hearings and to execute a removal order. ICE data show that, as of September 2024, ICE detained individuals for an average of 47 days. Within the criminal justice system, a federal criminal defendant may be held in custody by U.S. Marshals before and during their trial to ensure appearance at criminal proceedings, and to allow for safe transfer to the Bureau of Prisons if they receive a prison sentence. An individual convicted of a federal crime and sentenced to a term of imprisonment is held in prison as a punishment for their crime. The Bureau of Prisons manages a population of individuals convicted of federal crimes for varying lengths of time based on their sentences, which generally range from 5 years to life. These differences in roles and responsibilities of each agency, based on its detained population, result in some variations in their detention standards, as discussed below.

ICE has developed standards for immigration detention that dictate how facilities should operate to ensure safe, secure, and humane confinement. ICE has updated or introduced new detention standards multiple times since they were initially developed in 2000, resulting in various versions—or “sets”—of standards that differ with respect to their scope, rigor, and the laws and regulations they incorporate. Across these sets of detention standards, there are 45 different standards governing inspections of detention facilities. ICE’s inspections of record are conducted by the Office of Detention Oversight, which focuses its inspections on 14 core standards.[45]

To ensure individuals are housed in facilities that are safe and humane, U.S. Marshals and the Bureau of Prisons each have developed and adopted standards for confinement with which the facilities they use must comply. U.S. Marshals has developed its Federal Performance-Based Detention Standards that address seven functional areas, such as health care, safety and sanitation.[46] The Bureau of Prisons has developed its Program Review Guidelines that focus on a variety of areas, such as correctional services and food service operations.

The 14 ICE core detention standards, like the U.S. Marshals standards and Bureau of Prisons guidelines, are partially based on the American Correctional Association’s guidance, as well as relevant regulations and other sources utilized by each respective entity. The U.S. Marshals standards and Bureau of Prisons guidelines generally cover the same topic areas that are encompassed by ICE’s 14 core detention standards. The U.S. Marshals detention standards and Bureau of Prisons detention guidelines include language similar to the following ICE core detention standards:

· Environmental health and safety (housekeeping, garbage, water quality, emergency power, pest management, etc.);

· Emergency plans;

· Admission and release (health and other screenings, orientation, etc.);

· Custody classification system (separating detainees based on risk or vulnerabilities;

· Funds and personal property;

· Use of force and restraints;

· Special management units (segregating detainees from the general population for administrative or disciplinary reasons);

· Food service;

· Medical care/health care;

· Medical care/health care (females);

· Significant self-harm, and suicide prevention and intervention;

· Staff-detainee communication

· Grievance system; and

· Sexual abuse and assault prevention and intervention.

While all 14 ICE core standards are generally similar to the U.S. Marshals standards and Bureau of Prisons guidelines, there are some differences. These differences are attributable to the mission focus and detained population of each entity. For example, both the U.S. Marshals and Bureau of Prisons detention standards and guidelines include provisions for handling physical evidence related to potential legal violations committed by detained individuals—whether they are awaiting trial or serving sentences. Bureau of Prisons guidelines also include occupational and educational programs to prepare inmates for reentry into society along with other standards requiring communications and financial transactions to be monitored for evidence of criminal or terrorist activity.

In contrast to the Bureau of Prisons, ICE’s detained population consists of individuals being held for relatively shorter periods of time for civil violations of immigration law while they wait for removal from the country. They are also held if their removal proceedings are pending a decision by the immigration judge resolving their case.[47] Therefore, ICE may not have a need, for example, to provide occupational and educational programs similar to those in Bureau of Prisons facilities.

GAO Contact

Rebecca Gambler at gamblerr@gao.gov.

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact above, Meghan Squires (Assistant Director), Gary M. Malavenda (Analyst-in-Charge), Nasreen Badat, Russell Brown, Jr, Benjamin Crossley, Peter Del Toro, Michele Fejfar, Michael Harmond, Beatrice Kahn, Sasan J. “Jon” Najmi, and Janet Temko-Blinder all made key contributions to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]For clarity, we generally use the term “noncitizen” to refer to an “alien,” which is defined under U.S. immigration law as any person who is not a U.S. citizen or national. See 8 U.S.C. § 1101(a)(3).

[2]See 2024 Explanatory Statement, 170 Cong. Rec. H1501, H1812, H1850 (daily ed. Mar. 22, 2024), accompanying Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2024, Pub. L. No. 118-47, 138 Stat. 460. In March 2025, ICE received an additional appropriation for Operations and Support for the remainder of fiscal year 2025. See Full-Year Continuing Appropriations and Extensions Act, 2025, Pub. L. No. 119-4, div. A, title VII, § 1701(1), 139 Stat. 9, 27.

[3]ICE, Fiscal Year 2024 Annual Report, (Washington, D.C.: Dec.19, 2024).

[4]ICE, Performance-Based National Detention Standards 2011 (Revised 2016).