DEFENSE BUDGET

DOD Should Address All Statutory Elements for Unfunded Priorities

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights of GAO-25-107581, a report to congressional committees

DOD Should Address All Statutory Elements for Unfunded Priorities

Why GAO Did This Study

Specific DOD components are required by law to annually submit lists of unfunded priorities to Congress within 10 days of release of the President’s budget request. Unfunded priority lists include billions of dollars’ worth of additional military needs not included in the President’s budget request, such as aircraft and military construction.

Senate Report 118-58 included a provision for GAO to review how specific DOD components develop unfunded priority lists. This report examines how amounts for unfunded priorities changed over time and the extent to which selected DOD components addressed statutory elements in the fiscal year 2025 submissions for unfunded priorities, among other objectives.

GAO reviewed the 87 unfunded priority lists submitted to Congress between fiscal years 2020 and 2025 by all 18 DOD components required to do so. GAO also reviewed associated budget documentation. GAO selected a mix of 11 DOD components, varying by type, to assess whether their respective fiscal year 2025 unfunded priority lists addressed statutory elements.

What GAO Recommends

GAO recommends that Congress consider revising 10 U.S.C. 222a to clarify how unfunded priorities should be prioritized. GAO is also making five recommendations to DOD to ensure that all statutory elements are addressed in future submissions. DOD concurred with four recommendations and did not concur with one. GAO continues to believe that this recommendation is warranted, as discussed in the report.

What GAO Found

Department of Defense (DOD) components submitted unfunded priorities to Congress totaling $134 billion from fiscal year 2020 through fiscal year 2025, an increase of 73 percent over the time frame when adjusted for inflation, according to GAO’s analysis. These DOD components include the military services, the combatant commands, the National Guard Bureau and the Missile Defense Agency. For example, during the 6-year period, the military services identified $91.8 billion, which comprised 69 percent of the total amount for unfunded priorities. Of that, the Navy identified the most funding overall, $27 billion, largely for aircraft procurement and ship building. In fiscal year 2025, combatant commands identified the most for unfunded priorities, with U.S. Indo-Pacific Command having the largest amount of $11 billion.

Note: The other components from DOD include the National Guard Bureau and the Missile Defense Agency. Amounts are not adjusted for inflation.

Selected DOD components inconsistently addressed required statutory reporting elements and used different methodologies to prioritize and report their fiscal year 2025 submissions for unfunded priorities, according to GAO analysis. Six of the 11 DOD components GAO reviewed addressed all required statutory elements in their submissions to Congress. However, five did not do so, leaving out information on appropriation accounts and the reason why the recommended funding was not in the President’s budget request. GAO also found the statute is unclear on how unfunded priorities should be prioritized, which led to variation in the submissions reviewed. Without revising the statute to clarify how DOD should prioritize and report unfunded priorities to Congress, and without DOD components addressing all statutory elements, Congress may not have critical input to make informed funding decisions when assessing how to best address DOD’s readiness and warfighter needs for the fiscal year.

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Abbreviations

DOD Department of Defense

FYDP Future-Years Defense Plan/Program

MDA Missile Defense Agency

NDAA National Defense Authorization Act

PPBE Planning, Programming, Budgeting, and Execution

UPL Unfunded Priority List

September 4, 2025

Congressional Committees

The Department of Defense (DOD) is the largest federal agency with a discretionary budget of $848.3 billion in fiscal year 2025. During the formulation of the President’s annual budget request, DOD must prioritize its needs and make decisions about which items to include and exclude as part of the budget request. However, the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year 2017 directed certain DOD components to communicate to Congress about defense priorities that were not included in the President’s budget request.[1] These DOD components include the military services, the combatant commands, the National Guard Bureau and the Missile Defense Agency (MDA). Specifically, the NDAA requires these DOD components to submit unfunded priority lists (UPLs) to Congress not later than 10 days after submission of the President’s annual budget request.[2] UPL submissions typically include programs or mission requirements associated with an operational need, which would have been recommended for funding in the President’s budget request had additional resources been available, or the requirement emerged while the budget was being developed and was not included.[3] These UPLs include billions of dollars’ worth of military requirements, such as military construction or the procurement of aircraft.

While members of Congress have debated the utility and effect of UPLs, Congress uses UPLs and their associated justifications to evaluate DOD’s annual budget request and consider appropriating more funding than requested in the President’s budget to address unfunded priorities. The Senate report accompanying a bill for the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024 included a provision for us to review the development of and changes in UPLs over time, among other things.[4] This report examines (1) how the amounts for unfunded priorities submitted by DOD components changed from fiscal year 2020 through fiscal year 2025; (2) how selected DOD components received funding for unfunded priorities from fiscal year 2020 through fiscal year 2024; and (3) the extent to which selected DOD components addressed the required elements in relevant federal statutes in their respective unfunded priority list submissions for fiscal year 2025.

To address our first objective, we obtained documentation and received written responses to questions from all 18 DOD components that were required to submit UPLs between fiscal year 2020 and fiscal year 2025. We aggregated total amounts of UPL priorities by DOD component, fiscal year, and appropriation account.[5] To address our second objective, we reviewed unclassified UPL submissions, budget documentation, and tracking methods for 11 of the 18 DOD components required to submit UPLs. We chose these 11 DOD components to include a mix of military services, combatant commands, and other components. These 11 DOD components include the five military services (Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps, and Space Force); four combatant commands (U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, U.S. Northern Command, U.S. Space Command, and U.S. Special Operations Command); and two other components (the National Guard Bureau and MDA).[6] We reviewed appropriations accounts for the following: (1) Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation, (2) Procurement, and (3) Military Construction.[7] We also reviewed DOD’s quarterly budget execution reports to track funding trends and adjustments, including transfers and reprogramming, and interviewed agency officials.[8] To address our third objective, we reviewed the unclassified fiscal year 2025 UPL submissions of the same 11 DOD components selected for the second objective to evaluate whether the lists included all elements required by statute.[9] We also interviewed agency officials regarding their UPL submissions. We only assessed the official UPL transmitted to Congress and any supporting documentation provided at the same time or within the 10-day time frame to submit the UPLs after the release of the President’s budget request.[10] See appendix I for more details about our scope and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from May 2024 to September 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

DOD Budget Process Overview

The budget process begins with an examination of the military role and defense posture of the U.S. and DOD in the world environment, considering enduring national security objectives and the need for efficient management of resources. Based on internal programming guidance incorporating strategic objectives, including military roles and posture for the upcoming fiscal year, DOD components develop programs consistent with the guidance.[11] Following review and approval of component programs by the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the components develop and submit detailed budget estimates for their programs to the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller). The DOD Comptroller, in coordination with the Office of Management and Budget, reviews and prepares DOD’s budget for inclusion in the President’s annual budget request submitted to Congress. The Office of Management and Budget also reviews congressional budget justification materials prepared by departments and agencies, which are needed to explain their budget requests to their responsible congressional subcommittees.

Congress then considers the budget proposals and passes appropriations acts providing amounts for DOD and its components. Some DOD components receive appropriations into multiple accounts such as Operation and Maintenance; Procurement; Military Personnel; and Military Construction. Congress directs in conference reports or explanatory statements accompanying an appropriation how appropriated amounts are to be spent on authorized programs, projects, and activities. However, programmatic spending levels designated in conference reports or explanatory statements are not legally binding on a department or agency unless incorporated by reference into the actual appropriations act.

Legislative History of UPLs

DOD’s annual budget submission may not include all activities and programs identified as priorities. Beginning in fiscal year 2013, Congress began to encourage certain DOD components to submit a list of priorities that needed more funding, if available, and would substantially reduce operational or programmatic risk.

NDAA for Fiscal Year 2013. This Act included a “sense of Congress” provision that certain military services should submit to Congress, through the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the Secretary of Defense, a list of any priority military programs or activities that, if funded, would substantially reduce operational or programmatic risk or accelerate the creation or fielding of critical military capabilities.[12]

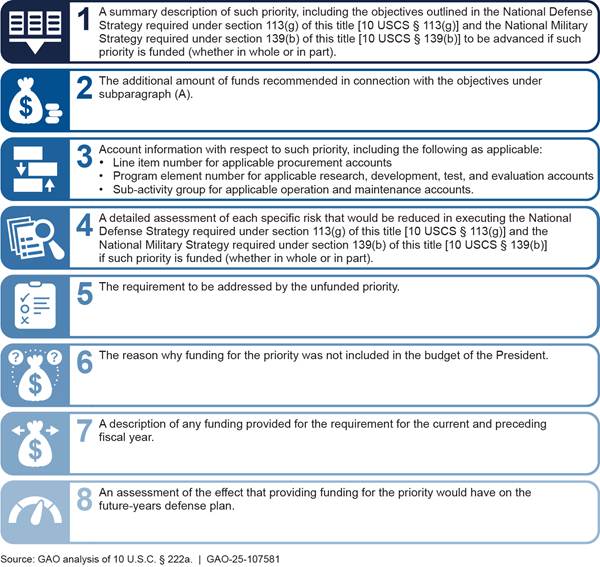

NDAA for Fiscal Year 2017. This Act established a statutory requirement designated at 10 U.S.C. 222a that annual lists of unfunded priorities be submitted to Congress by the military services and combatant commands within 10 days of the President’s budget request submission.[13] The four required UPL elements included in newly enacted 10 U.S.C. 222a included (1) a summary description of such priority, including the objectives outlined in the national defense strategy and the national military strategy; (2) additional amounts recommended in connection with the objectives; (3) account information with respect to such priority, such as line-item numbers, program element numbers, or sub-activity groups; and 4) a detailed assessment of each specific risk that would be reduced in executing the national defense strategy and the national military strategy if such priority was funded.[14] The NDAA also established a requirement that MDA submit to Congress its unfunded priorities within the same 10-day period with three similar elements. MDA is required to provide (1) a summary description of each priority, including objectives to be achieved if funded in whole or in part; (2) the additional amount recommended in connection with the objectives; and (3) account information with respect to such priority.[15]

NDAA for Fiscal Year 2019. This Act transferred the 2017 reporting requirement for the Missile Defense Agency to title 10, U.S. Code and redesignated it as section 222b.[16]

NDAA for Fiscal Year 2020. This Act amended 10 U.S.C. 222a to specifically provide for the inclusion of “covered” military construction projects in annual UPLs.[17] Covered military construction projects that may be included are those included in any fiscal year of the 5-year future-years defense program (FYDP) submitted with the President’s budget request, or are considered by a combatant commander and are executable in the fiscal year.[18]

NDAA for Fiscal Year 2021. This Act amended 10 U.S.C. 222a to include the Chief of Space Operations and the Chief of the National Guard Bureau amongst those required to submit a UPL.[19]

NDAA for Fiscal Year 2023. This Act added a requirement for the Secretary of Defense, in consultation with the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, to submit a report prioritizing each specific unfunded priority across all unfunded priorities submitted by the services, combatant commands, and the National Guard Bureau according to the risk reduced in executing the National Defense Strategy and the National Military Strategy.[20] For fiscal years 2024 and 2025, the Secretary of Defense responded to this requirement by submitting letters to Congress stating that no priorities on the UPLs were a higher priority than those included in the President’s budget request.

NDAA for Fiscal Year 2024. This Act added additional reporting elements to 10 U.S.C. 222a.[21] These reporting elements included (1) reporting the requirement addressed by the unfunded priority; (2) the reason why funding for the priority was not included in the President’s budget request; (3) a description of any funding provided for the requirement for the current and preceding fiscal year; and (4) an assessment of the effect that providing funding for the priority would have on the FYDP.

NDAA for Fiscal Year 2025. This Act repealed 10 U.S.C. 222b requiring the Missile Defense Agency to submit an annual UPL and reenacted as 10 U.S.C. 5513.[22] Required report elements remained unchanged.

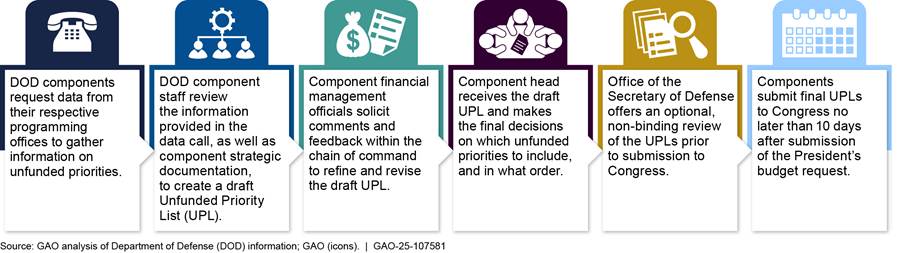

Overview of UPL Development Process

The development of UPLs is a by-product of DOD’s budget process. Designated DOD components are required to submit UPLs to Congress within 10 days of submission of the President’s budget request. Officials from multiple DOD components stated that the discussions about potential priorities to include in their UPL begin months before the President’s budget is finalized and submitted to Congress. Figure 1 illustrates the steps DOD components follow when developing and submitting their UPLs.

According to DOD officials, the contents of a DOD component’s UPL submission can vary yearly due to component leadership priorities, or the changing needs of the particular component or other components based on emerging situations or requirements. Each component has the discretion to present its UPL in the format that it chooses, though all UPL submissions must include the statutory elements cited above. DOD components may also use their own prioritization processes, such as scoring systems and internal planning guidance, to develop their UPL. Officials from multiple DOD components noted that they include priorities that can be executed within one fiscal year and would not carry costs beyond those budgeted in the FYDP. According to DOD officials, statutory changes over time have resulted in format changes, such as components presenting UPLs using tables, narrative responses, or a mix of both.

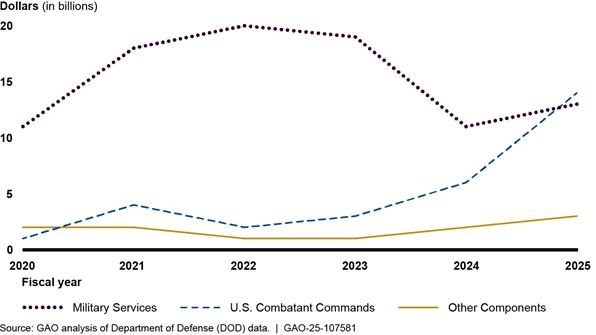

DOD Components Submitted Unfunded Priorities Totaling $134 Billion from Fiscal Years 2020 through 2025, with a 73 Percent Increase Over That Time Frame

DOD components submitted unfunded priorities to Congress totaling $134 billion overall, or an increase of 73 percent from fiscal year 2020 to fiscal year 2025 when adjusted for inflation, according to our analysis. We reviewed 87 UPLs from all 18 DOD components that were required to submit UPLs between fiscal years 2020 through 2025, totaling over 1,600 unfunded priorities. Specifically, DOD components increased their cumulative funding recommendations to Congress for unfunded priorities from $14.7 billion in fiscal year 2020 to $30 billion in fiscal year 2025, as shown in figure 2. The total amount of funding submitted for unfunded priorities during fiscal year 2020 through fiscal year 2025 represented an addition of 3 percent above the President’s DOD budget request totaling $4.6 trillion over the same time frame.[23]

Note: Amounts are not adjusted for inflation and may not add due to rounding.

DOD officials attribute the increase in amounts for unfunded priorities to many factors such as changes in DOD component needs; the creation of new components; and changes in data available to the components. For example:

· Army and Navy officials stated that emerging needs and world events can affect the inclusion and order of priorities on the UPL.

· In fiscal year 2020, the Space Force and U.S. Space Command were newly established DOD components that did not submit unfunded priorities in their early years. Subsequently, their cumulative submissions added between $700 million to $2.4 billion to yearly UPL amounts.

· U.S. Indo-Pacific Command did not include a dollar value for its unfunded priorities until fiscal year 2021, when it developed an internal assessment that allowed it to identify amounts.

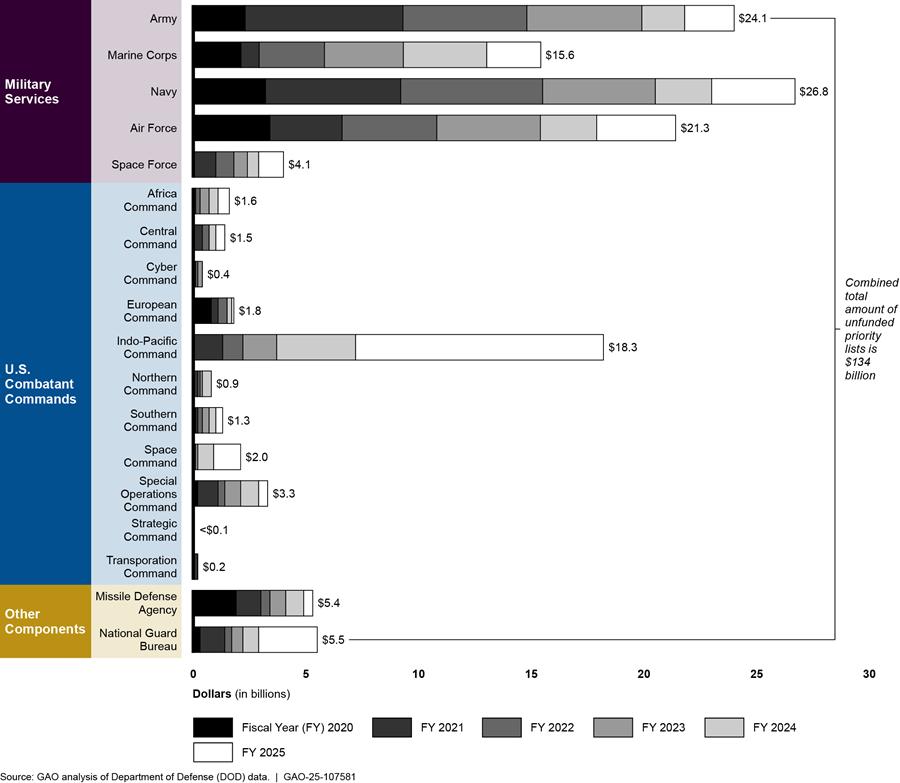

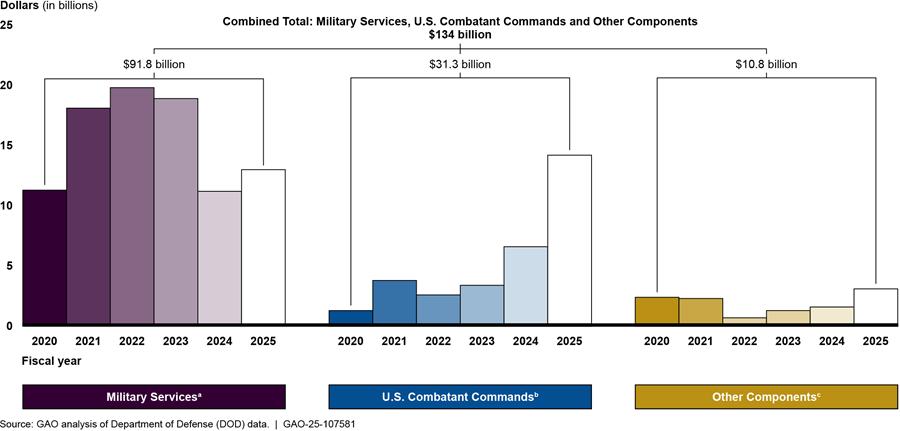

We also found that of the $134 billion of UPLs submitted to Congress from fiscal year 2020 through fiscal year 2025, (1) military services comprised 69 percent or $91.8 billion; (2) combatant commands comprised 23 percent, or $31.3 billion; and (3) other agencies (the National Guard Bureau and the MDA) comprised 8 percent, or $10.8 billion (see figure 3).

Figure 3: Total Amounts Submitted for Unfunded Priorities by DOD Component Type, Fiscal Years 2020–2025

Note: Amounts are not adjusted for inflation and may not add due to rounding. The military services consist of the Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps, and Space Force. The U.S. combatant commands include U.S. Africa Command, U.S. Central Command, U.S. Cyber Command, U.S. European Command, U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, U.S. Northern Command, U.S. Southern Command, U.S. Space Command, U.S. Special Operations Command, U.S. Strategic Command, and U.S. Transportation Command. The other DOD components are the National Guard Bureau and the Missile Defense Agency.

Military services. Prior to fiscal year 2025, the military services submitted the most UPL funding in each fiscal year compared with other DOD components. Overall, the Navy submitted the most UPL funding of all DOD components. Its UPLs comprised 20 percent, or $27 billion, of the $134 billion total between fiscal years 2020 and 2025, largely for aircraft procurement and shipbuilding. The Army followed, comprising 18 percent, or $24 billion—almost a third of which was for the procurement of equipment, including combat vehicles, aircraft, and missiles. The Air Force comprised 16 percent, or $21 billion—almost 40 percent of which was for the procurement of aircraft.

Combatant commands. In fiscal year 2025, the combatant commands submitted the highest dollar amount for unfunded priorities. For example, in fiscal year 2025 U.S. Indo-Pacific Command submitted unfunded priorities totaling $11 billion, which was 37 percent of the approximately $30 billion that DOD components submitted that year. By comparison, in fiscal year 2024, U.S. Indo-Pacific Command submitted $3.5 billion in unfunded priorities. According to the officials, new command leadership chose to include all unfunded priorities in the fiscal year 2025 submission, whereas in prior years U.S. Indo-Pacific Command only included a subset of its unfunded priorities—those the commander deemed most important—on the list it submitted to Congress.

Other components. Other DOD components—the National Guard Bureau and MDA—comprised a smaller portion of the overall amount submitted for unfunded priorities. Between fiscal years 2020 and 2025, the unfunded priorities of the National Guard Bureau and MDA accounted for $10.8 billion of the $134 billion overall total, or just over 8 percent.

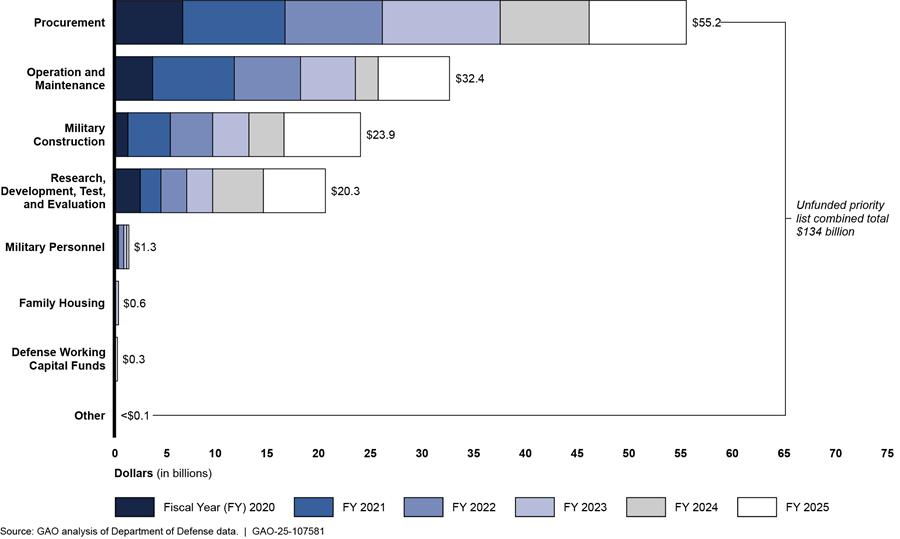

Additionally, our analysis of DOD data show that from fiscal year 2020 through fiscal year 2025, DOD components primarily submitted unfunded priorities associated with seven types of appropriation accounts: (1) Procurement; (2) Operation and Maintenance; (3) Military Construction; (4) Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation; (5) Military Personnel; (6) Family Housing; and (7) Revolving and Management Funds, which is the appropriation for Defense Working Capital Funds (see figure 4).

Figure 4: Total Amounts Submitted for Unfunded Priorities by Appropriation Type, Fiscal Years 2020–2025

Note: Appropriation type amounts were not adjusted for inflation and may not add due to rounding. The “other” category represents $16 million for a U.S. European Command unfunded priority from its fiscal year 2020 submission. The amount was to be split between the Navy’s Operation and Maintenance and Military Personnel appropriations, but U.S. European Command officials could not provide the breakdown of how much funding was for each appropriation.

DOD components submitted the most funding for Procurement accounts associated with unfunded priorities in each fiscal year from fiscal year 2020 through fiscal year 2025. Procurement account UPLs during this time frame comprised 41 percent, or $55.2 billion of the $134 billion submitted in total. Aircraft procurement represented a large portion of those unfunded priorities at approximately $23 billion. Procurement represented the majority of funding for the Air Force, Marine Corps, Navy, National Guard Bureau, and U.S. Special Operations Command unfunded priorities. For the Army, U.S. Africa Command, U.S. Central Command, U.S. Cyber Command, and U.S. Southern Command, Operation and Maintenance comprised the majority of the funding for their unfunded priorities.

Selected DOD Components Support Unfunded Priorities Through Lump-Sum Appropriations and DOD Flexibilities

DOD components receive amounts for unfunded priorities through lump-sum appropriations and can support these priorities using funds management flexibilities, such as allotments, reprogramming, and transfers.[24] DOD budget execution documentation—reporting of obligations and expenditures, reprogramming and transfers—does not always identify amounts used to support unfunded priorities as separate from amounts used to support other budgetary priorities.[25] However, for the 11 selected DOD components we reviewed, we identified budget lines specifically associated with unfunded priority submissions and found that about half of these budget lines received more funds than was requested in the President’s budget.[26]

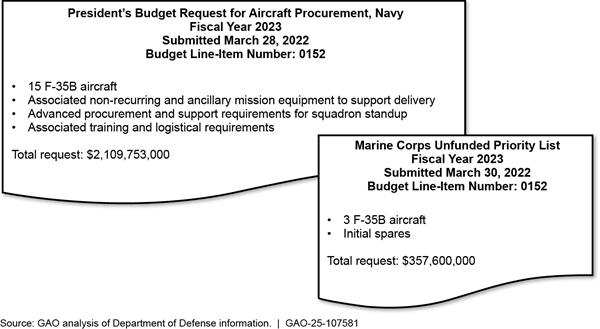

A budget line may support multiple activities, some of which may be associated with an unfunded priority. See figure 5 for an example. In this example, an unfunded priority submission for additional aircraft refers to a budget line-item number from the President’s budget that includes a range of activities such as procurement of aircraft and support requirements.

Figure 5: Example of a Budget Line with Multiple Activities, Some of Which Are Associated with an Unfunded Priority

Note: The President’s budget request for the Department of the Navy also resources the Marine Corps. This figure reflects an example of activities associated with an unfunded priority. In this example, an unfunded priority submission for additional aircraft references a budget line-item number from the President’s budget that includes a range of activities such as procurement of aircraft and support requirements.

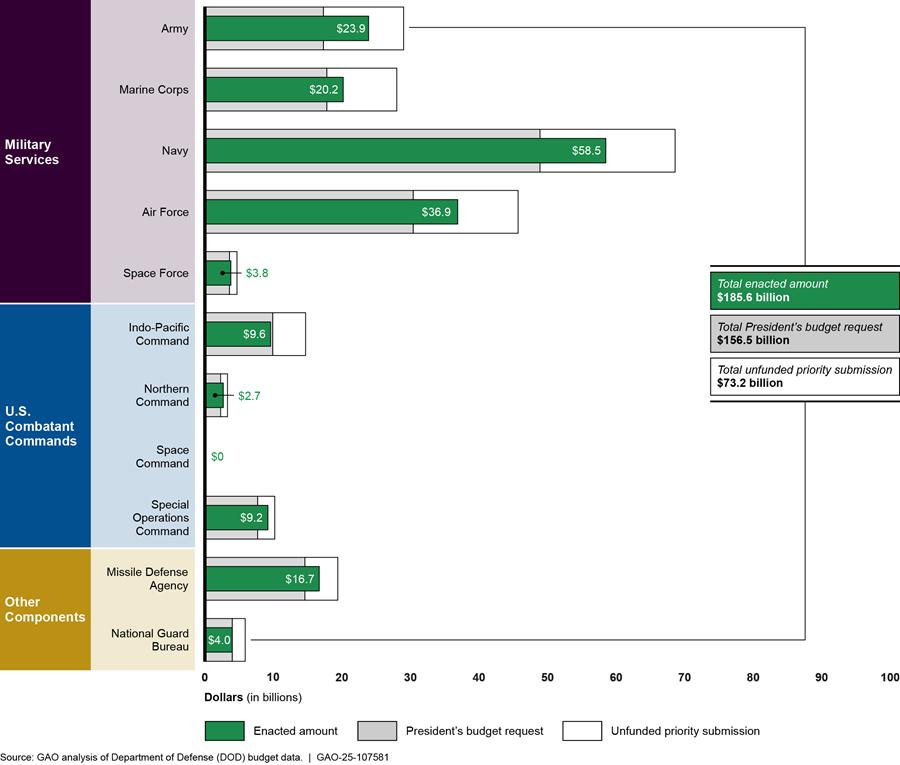

Our analysis of funding for activities associated with unfunded priorities for the 11 DOD components we reviewed resulted in several observations regarding amounts requested and appropriated, as well as the use of funds management flexibilities, in support of unfunded priorities. For the 11 selected DOD components where we identified activities associated with unfunded priorities, we found that approximately half of such activities received more funding from Congress than was requested in the President’s budget for fiscal year 2020 through fiscal year 2024. For example, the Air Force requested a total of $30.4 billion for activities associated with unfunded priorities in the President’s budget across this period. The Air Force also submitted UPLs amounting to an additional $15.3 billion for those activities over the same time frame. The Air Force’s total enacted amounts for activities associated with unfunded priorities over that period, as reported in DOD data, totaled $36.9 billion, or $6.5 billion above the Air Force’s funding request included in the President’s budget. Figure 6 shows, for the selected 11 DOD components, the total amounts requested and enacted for activities associated with unfunded priorities for fiscal year 2020 through fiscal year 2024.

Figure 6: Selected DOD Components’ Requested and Enacted Amounts for Activities Associated with Unfunded Priorities for Fiscal Years 2020–2024

Note: Congress has the authority to establish and authorize appropriations higher or lower than requested amounts for federal agencies, programs, policies, projects, or activities. Therefore, the President’s budget request and unfunded priority submissions may not equal the enacted amount. This figure reflects analysis of budget lines for activities we identified as associated with unfunded priorities and amounts may not add due to rounding. It includes amounts associated with the following appropriations accounts: 1) Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation, 2) Procurement, and 3) Military Construction. We did not include unfunded priorities for Operation and Maintenance or classified program budget lines. The Department of Defense (DOD) budget request and explanatory statements accompanying appropriations do not include Operation and Maintenance budget information at the same level of detail as other appropriations accounts. Enacted amounts as reported in DOD data may not match actual amounts appropriated due to internal reprogramming actions, authorized transfers, or other account transactions occurring during the period of execution.

Of the amounts appropriated in excess of amounts requested, not all was for unfunded priorities. Such additional funding may also address congressional special interest items, emergent requirements, or other activities. For example, the Air Force submitted $858 million in funding for the F-35 aircraft in its fiscal year 2023 UPL. Air Force officials told us that the subsequent appropriation included $819 million in additional funding for the UPL, and $115 million of that was unrelated to the UPL.

We found other instances in which DOD components received more funding than they submitted for some unfunded priorities and no funding for others on their UPL submissions. For example, in fiscal year 2020, the Marine Corps submitted funding for procurement of two F-35B aircraft and spare parts in its UPL. Marine Corps officials told us that in the subsequent appropriation, the associated activity received an increase in funding for procurement of an additional four aircraft, but did not receive funding for the spare parts. Officials from all the selected DOD components told us they track all appropriated amounts to ensure amounts are used consistent with congressional intent. For example, MDA officials told us they specifically track UPL funding using an internal tag with which officials can identify specific funding added by Congress as well as related obligations and expenditures.

Congress can appropriate more than was requested and also provide additional funding through supplemental appropriations acts. For example, the Army included a recommendation for funding for the Improved Bradley Acquisition Subsystem Upgrade in its fiscal year 2023 UPL submission. Army budget officials told us that this unfunded priority was not funded as part of enacted regular appropriations for the associated activity, but instead through a supplemental appropriations act. In addition, we found that the 11 selected DOD components used their authority to transfer or reprogram appropriated funding, within certain limits, to unfunded priorities. We found that from fiscal years 2020 through 2024, the 11 selected DOD components reported moving approximately $7.9 billion—via transfers or reprogramming—into activities associated with unfunded priorities, and approximately $1.5 billion out, for a net increase of $6.4 billion.

Some Components Did Not Address All Statutory Elements in Their Unfunded Priority Submissions, and the Statutory Requirement Is Unclear About Prioritization

Five of 11 Selected DOD Components Did Not Address All Statutory Elements for Unfunded Priorities in Their Fiscal Year 2025 Submissions

We reviewed the fiscal year 2025 UPL submissions to Congress from the 11 selected DOD components and found that six of them addressed all the statutory elements which we assessed, while UPLs of five DOD components contained priorities that did not address all of the elements we assessed.[27] The six DOD components that addressed all of the statutory elements we assessed were the Air Force, Marine Corps, MDA, Navy, Space Force, and U.S. Space Command. The six DOD components provided different levels of information in response to each statutory element. For the complete details of our assessment, see appendix II.

Five of the 11 DOD components we assessed—U.S. Northern Command, Army, U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, National Guard Bureau, and U.S. Special Operations Command—did not address all of the required statutory elements we assessed for some unfunded priorities in their respective fiscal year 2025 UPL submissions. The UPL statute requires DOD components to include, among other required elements, (1) appropriation account information; (2) the reason why funding for the priority was not included in the President’s budget request; and (3) an assessment of the effect that providing funding for the priority would have on the FYDP.[28] However, the UPLs of the five DOD components did not address these elements required in statute for some unfunded priorities.

U.S. Northern Command. U.S. Northern Command did not include appropriation account information for its only unfunded priority in its fiscal year 2025 UPL submission. U.S. Northern Command officials cited a lack of visibility into the account information as the reason why it was not included. The officials explained that the unfunded priority belongs to a military service, and that the military service’s budget justification book containing the appropriation account information was not published in time for U.S. Northern Command to include the information in its UPL given the 10-day time frame within which the command must provide its list after the budget is submitted. However, the UPL statute requires DOD components to include appropriation account information.[29] The other combatant commands that we assessed provided the account information for the unfunded priorities on their respective lists.

Army. The Army identified a reason why some unfunded priorities were not included in the President’s budget request, but did not do so for all of the unfunded priorities in its fiscal year 2025 UPL submission to Congress. Also, the Army did not include an assessment of the effect that providing funding would have on the FYDP for any of its unfunded priorities. Army officials cited the military service’s large number of unfunded priorities (39) as well as its process for evaluating its unfunded priorities as reasons why these elements were not addressed in the fiscal year 2025 submission. That process consists of a structured evaluation where each unfunded priority under consideration for the final UPL is scored against defined criteria. The resulting list then undergoes multiple rounds of review and revision, with feedback exchanged between the Army staff, combatant commands, and the Army Chief of Staff’s office, according to Army officials. However, the UPL statute requires DOD components to clearly identify why an unfunded priority was not included in the President’s budget request and to provide an assessment that funding the priority would have on the FYDP.[30] Army officials acknowledged they could have more clearly articulated the potential effects on the FYDP and the rationale for excluding these requirements from the President’s Budget, and stated that they would take steps to include the information in future submissions.

U.S. Indo-Pacific Command. U.S. Indo-Pacific Command identified a reason why some unfunded priorities were not included in the President’s budget request, but did not do so for all of the priorities on its UPL submission for fiscal year 2025. Also, U.S. Indo-Pacific Command did not include an assessment of the effect that providing funding would have on the FYDP for any of its UPL priorities. U.S. Indo-Pacific Command officials stated that almost all unfunded priorities on its UPL are owned by the military services and that they do not always have visibility into the reasons why something was not included in a military service’s budget request, or the effect that funding a priority might have on the FYDP. According to one official, as required UPL elements have increased, it has become increasingly difficult for U.S. Indo-Pacific Command to produce a meaningful list within 10 days. They cited the classification challenges associated with some of the programs and the need to ensure that the list is consistent with the capability needs of the command. U.S. Indo-Pacific Command officials added that they believed information related to these two elements was included in a classified annex and additional budget documentation, such as briefings, that they provided to Congress. These officials said that to include this information separately in the unclassified UPL submission would be a duplication of effort. We reviewed the classified annex that was part of U.S. Indo-Pacific Command’s UPL submission and found that it did indicate a reason why some unfunded priorities were not included in the President’s budget request, but did not address this element for most of its unfunded priorities. Further, the classified documentation did not identify potential effects on the FYDP. The UPL statute requires DOD components to clearly identify why an unfunded priority was not included in the President’s budget request and to provide an assessment of the effect that funding the priority would have on the FYDP.[31]

National Guard Bureau. The National Guard Bureau did not always identify the reason why priorities were excluded from the President’s budget request, and did not identify the effect on the FYDP of funding its priorities.[32] Specifically, the National Guard Bureau identified a reason why three priorities were not included in the President’s budget request, but did not do so for the remainder of the priorities on its UPL submission for fiscal year 2025. The National Guard Bureau also did not include an assessment of the effect that providing funding would have on the FYDP for any of its unfunded priorities. In discussing the reasons why this information was not provided, National Guard Bureau officials stated that congressional staff provided them with a UPL template to complete and that the template did not include a field for either the reason an unfunded priority was not included in the President’s budget request or the effect that providing funding for the priority would have on the FYDP. The UPL statute requires DOD components to clearly identify why an unfunded priority was not included in the President’s budget request and to provide an assessment of the effect that funding the priority would have on the FYDP.[33]

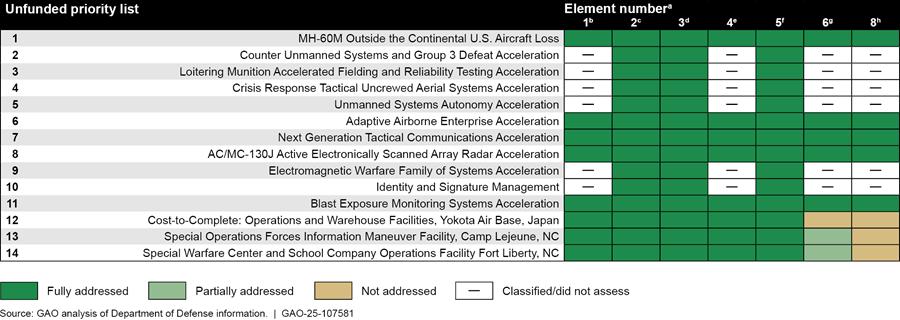

U.S. Special Operations Command. U.S. Special Operations Command did not identify the reason why one unfunded military construction priority was excluded from the President’s budget request, and did not always identify the effect on the FYDP of funding its priorities. Specifically, U.S. Special Operations Command included a reason why unfunded priorities were excluded from the President’s budget request and the effect that providing funding would have on the FYDP for its unfunded non-military construction priorities. However, it did not always include similar information for its unfunded military construction priorities. When soliciting information from program managers for its unfunded priorities, U.S. Special Operations Command uses different questionnaires for military construction and non-military construction priorities. The non-military construction questionnaire includes a question specifically asking for the reason the priority was not included in the President’s budget request and two questions intended to identify quantifiable impacts on the FYDP of funding a given UPL priority. However, U.S. Special Operations Command’s military construction questionnaire does not have similar questions. The UPL statute requires DOD components to clearly identify why an unfunded priority was not included in the President’s budget request and to provide an assessment of the effect that funding the priority would have on the FYDP.[34]

Designated DOD components are required by statute to submit annual UPLs and include certain elements in their submission.[35] Five of the DOD components we selected for our review did not include all required elements because they did not take steps to ensure that the necessary information was included in their UPL submissions. By providing complete information about UPLs to Congress as required by statute, U.S. Northern Command, the Army, U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, the National Guard Bureau, and U.S. Special Operations Command would better position Congress to make informed decisions about funding to help DOD achieve its objectives. Specifically, by providing appropriation account information, U.S. Northern Command would help Congress know where to direct funding if it chooses to provide support for an unfunded priority. By providing a reason why an unfunded priority was not included in the President’s budget request, the Army, U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, the National Guard Bureau, and U.S. Special Operations Command would inform Congress whether a priority is a new emerging requirement that did not go through the normal budget process, or one that went through the process but was not deemed a high enough priority. Those same components could provide information to help Congress understand whether funding a priority would have future budget impacts. Without this information, Congress may lack critical input to make informed decisions about budget tradeoffs when assessing DOD’s funding needs for the fiscal year.

Selected DOD Components Used Different Methodologies to Prioritize and Report Unfunded Priorities Because the Statutory Requirement Is Unclear

The selected DOD components used different methodologies to prioritize and report their UPLs to Congress. This resulted in inconsistencies in the unfunded priority lists, both in terms of the information provided and the number of lists each component provided. DOD components, except for MDA, are directed to prioritize their respective unfunded priorities in the following ways: (1) in overall order of urgency according to the amount of risk reduced; (2) in overall order of urgency among unfunded priorities (other than covered military construction projects); and (3) in overall order of urgency among covered military construction projects.[36] For example, we found:

· Five DOD components—Army, Marine Corps, U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, U.S. Special Operations Command, and the National Guard Bureau—provided one list each to Congress, combining military construction priorities and non-military construction priorities.

· One DOD component, the Navy, provided two different lists—one with military construction priorities and one with non-military construction priorities.

· Two DOD components—the Air Force and Space Force—provided two lists, one list with military construction priorities and another list with mostly non-military construction priorities, and a single entry for the total amount of military construction projects included.

· Three DOD components—U.S. Northern Command, U.S. Space Command, and MDA—did not identify any military construction priorities on their respective fiscal year 2025 UPLs.

The statutory requirement for prioritizing unfunded priorities is unclear because it does not identify how designated components should present their prioritized UPLs, whether there should be one list or multiple lists, and what each list should contain, such as whether military construction and non-military construction priorities should remain separate or be comingled.[37] By clarifying the statutory requirement on how the DOD components should prioritize and report their unfunded priorities, Congress can help ensure that DOD components prioritize and submit their UPLs in a consistent manner. This would help Congress evaluate unfunded priorities and make informed funding decisions to address DOD’s readiness and warfighter needs.

Conclusions

DOD’s UPLs include billions of dollars’ worth of military requirements not included in the President’s budget request. While these yearly recommendations are small in comparison with DOD’s overall budget request over the same time frame, they represent billions in additional funding needs identified by the DOD components. The statutory elements required for UPL submissions provide specific information—such as appropriation account information; reasons why an unfunded priority was not requested in the President’s budget request; and how funding the priority could affect DOD’s future year funding—to help Congress make informed budget decisions.[38] UPLs and supporting documentation can help Congress to evaluate DOD’s annual budget request and determine annual funding amounts. Without information that addresses all statutory elements on unfunded priorities, Congress will not have critical input needed to make informed budget tradeoffs when assessing DOD’s funding needs for the fiscal year.

However, the UPL statutory reporting language is not clear about how UPLs are to be prioritized. Revising the language to clarify this requirement will help DOD to better present its prioritized UPLs.[39] Without clarifying how the designated DOD components should present their prioritized UPLs, Congress will continue to receive inconsistent UPL prioritization presentations, which may make it difficult for Congress to evaluate the importance of each requirement and make informed funding decisions to address readiness and warfighter needs.

Matter for Congressional Consideration

Congress should consider revising 10 U.S.C. 222a to clarify how designated DOD components should present their prioritization of unfunded priority lists. (Matter for Consideration 1)

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making a total of five recommendations to DOD.

The Commander of U.S. Northern Command should take steps to ensure that all information required by 10 U.S.C. 222a, particularly identifying and including appropriation account information, is included in future UPL submissions. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of the Army should take steps to ensure that all information required by 10 U.S.C. 222a, particularly the reason why an unfunded priority is not included in the budget request of the President and the effect of funding a priority on the FYDP, is included in future UPL submissions. (Recommendation 2)

The Commander of U.S. Indo-Pacific Command should take steps to ensure that all information required by 10 U.S.C. 222a, particularly the reason why an unfunded priority is not included in the budget request of the President and the effect of funding a priority on the FYDP, is included in future UPL submissions. (Recommendation 3)

The Chief of the National Guard Bureau should take steps to ensure that all information required by 10 U.S.C. 222a, particularly the reason why an unfunded priority is not included in the budget request of the President and the effect of funding a priority on the FYDP, is included in future UPL submissions. (Recommendation 4)

The Commander of U.S. Special Operations Command should take steps to ensure that all information required by 10 U.S.C. 222a, particularly the reason why an unfunded priority is not included in the budget request of the President and the effect of funding a priority on the FYDP, is included in future UPL submissions. (Recommendation 5)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to DOD for review and comment. In written comments, reproduced in appendix III, DOD concurred with four of our recommendations directed to U.S. Northern Command; Army; U.S. Indo-Pacific Command; and the National Guard Bureau. DOD did not concur with one recommendation directed to U.S. Special Operations Command.

DOD, specifically U.S. Special Operations Command, did not concur with our recommendation to the Commander of U.S. Special Operations Command. U.S. Special Operations Command responded that it does not include an unfunded priority submission unless the need emerged after the President’s budget request was submitted. U.S. Special Operations Command further stated that for non-military construction unfunded priorities, it asks all subordinate organizations why the priorities are not included in the President’s budget request. For military construction unfunded priorities, U.S. Special Operations Command stated that, historically, all priorities submitted to Congress are projects for which it submitted initial documentation and are already in progress in the FYDP. These projects can be accelerated with additional resourcing through the UPL process, according to U.S. Special Operations Command. We agree that U.S. Special Operations Command fully addressed all statutory elements in its fiscal year 2025 UPL submission for unfunded non-military construction priorities. However, U.S. Special Operations Command did not do so for three military construction priorities. Specifically, as discussed in our report, for one of the three military construction priorities, U.S. Special Operations Command did not identify a reason why the military construction project was not included in the fiscal year 2025 President’s budget request, as required by statute. Additionally, U.S. Special Operations Command did not explicitly identify in its fiscal year 2025 UPL submission any effects that funding the three military construction priorities would have on the FYDP, as required by statute.

The NDAA for Fiscal Year 2024 added additional reporting requirements which are to be specified, and were not required historically, such as the reason why the priority was not included in the President’s budget request and the effect of funding the priority on the FYDP.[40] We maintain that taking steps to ensure that all information required by statute is explicitly included in future UPLs will improve Congress’s ability to make informed funding decisions for U.S. Special Operations Command. Without U.S. Special Operations Command addressing all statutory elements, Congress may not have critical input to make informed funding decisions when assessing how to best address DOD’s readiness and warfighter needs for the fiscal year.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Defense, the Secretaries of the Military Departments, the Commanders of the Combatant Commands, the Chief of the National Guard Bureau, the Director of the Missile Defense Agency, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact Rashmi Agarwal at AgarwalR@gao.gov or Mona Sehgal at SehgalM@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix IV.

Rashmi Agarwal

Acting Director, Defense Capabilities and Management

Mona Sehgal

Director, Contracting and National Security Acquisitions

List of Committees

The Honorable Roger Wicker

Chairman

The Honorable Jack Reed

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

United States Senate

The Honorable Mitch McConnell

Chair

The Honorable Christopher Coons

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Defense

Committee on Appropriations

United States Senate

The Honorable Mike Rogers

Chairman

The Honorable Adam Smith

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

House of Representatives

The Honorable Ken Calvert

Chairman

The Honorable Betty McCollum

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Defense

Committee on Appropriations

House of Representatives

This report examines (1) how the amounts for unfunded priorities submitted by Department of Defense (DOD) components changed from fiscal year 2020 through fiscal year 2025; (2) how selected DOD components received funding for unfunded priorities from fiscal year 2020 through fiscal year 2024; and (3) the extent to which selected DOD components addressed the required elements in relevant federal statutes in their respective unfunded priority list (UPL) submissions for fiscal year 2025.

For our first objective, we obtained and reviewed the UPLs of designated DOD components that were required to submit for fiscal year 2020 through fiscal year 2025.[41] For the 18 designated DOD components submitting UPLs, we reviewed 87 total UPLs, identifying the funding amounts for over 1,600 priorities and the appropriation account(s) associated with the priority. We conducted our analysis by aggregating total amounts by DOD component, fiscal year, and appropriation account for all unfunded priorities submitted, including classified and unclassified priorities. For each unfunded priority, the team used the appropriation codes and additional support from information requests to identify the amounts submitted for each of the following DOD appropriation categories, per fiscal year: (1) Family Housing, (2) Military Construction, (3) Military Personnel, (4) Operation and Maintenance, (5) Procurement, (6) Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation, and (7) Revolving and Management Funds, which is the appropriation for Defense Working Capital Funds. To further understand the development of the UPL, we obtained documentation, conducted interviews, or received written responses from all 18 DOD components required to submit UPLs, as well as the Office of the Secretary of Defense. We reviewed the official UPL submissions for gaps or inconsistencies in the data and, in instances where UPL documentation conflicted as to the amount or appropriation account, we requested clarification and supporting documentation from agency officials. We used the follow-up information to update our analysis. We determined the data was sufficiently reliable for the purposes of presenting amounts submitted by DOD components for unfunded priorities.

For our second objective, we selected 11 of 18 DOD components required to submit UPLs.[42] We chose these 11 components to include a mix of military services, DOD combatant commands, the National Guard Bureau, and the Missile Defense Agency (MDA). These 11 DOD components included the five military services (Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps, and Space Force); four combatant commands (U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, U.S. Northern Command, U.S. Space Command, and U.S. Special Operations Command); and two other components (the National Guard Bureau and MDA).[43] We chose U.S. Special Operations Command and U.S. Space Command because they have acquisition authority or oversight responsibility.[44] We also chose U.S. Indo-Pacific Command and U.S. Northern Command to represent the geographic combatant commands in our analyses. We obtained and reviewed unclassified budget documents and UPL submissions for each of the 11 selected DOD components for fiscal year 2020 through fiscal year 2024, which together accounted for approximately 95 percent of the total amount submitted for unfunded priorities during that time frame.[45] Specifically, we reviewed unclassified appropriations documentation and budget justification materials associated with the following categories: (1) Research, Development, Test and Evaluation, (2) Procurement, and (3) Military Construction.[46] We conducted our analysis by identifying the budget lines associated with unfunded priorities and reviewing DOD’s quarterly budget execution reports to understand UPL funding, execution, and adjustments, including transfers and reprogramming.[47] We also reviewed tracking methods the components used for funding received for activities associated with unfunded priorities, and discussed these methods with DOD component officials. To understand the budget and UPL processes, we met with military service, combatant command, National Guard Bureau, and MDA officials responsible for coordination and oversight. We also met with DOD officials responsible for UPL submission time frames, budget justification processes, and the tracking of activities associated with UPL funding.

For our third objective, we reviewed UPLs from the same 11 designated DOD components from the previous objective for fiscal year 2025 to evaluate whether the lists included all elements required by statute.[48] In determining the statutory elements for which to assess the UPL submissions, we selected seven of the eight elements contained in the UPL statute covering the military services and combatant commands, the first three of which overlap with the three required elements in the UPL statute covering the MDA.[49] Those elements were

· a summary description of the priority, including the objectives outlined in the National Defense Strategy and the National Military Strategy to be advanced if the priority is funded (whether in whole or in part);[50]

· the additional amount of funds recommended in connection with the objectives;

· appropriation account information with respect to the priority, including, as applicable, (1) the line-item number for Procurement accounts, (2) the program element number for Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation accounts, and (3) sub-activity group for Operation and Maintenance accounts;

· a detailed assessment of each specific risk that would be reduced in executing the National Defense Strategy and the National Military Strategy if the priority is funded (whether in whole or in part);

· the requirement to be addressed by the unfunded priority;

· the reason why funding for the priority was not included in the budget of the President; and

· an assessment of the effect that providing funding for the priority would have on the future-years defense plan.

With input from a GAO attorney and a methodologist, we developed a codebook that established what factors we would consider when determining whether an unfunded priority fully addressed, partially addressed, or did not address each statutory element. Two GAO analysts reviewed the unclassified fiscal year 2025 UPLs for the 11 designated components and assessed them for the seven statutory elements (three in the case of the MDA). This assessment was done with real-time input from the GAO attorney and methodologist to ensure the team was applying the criteria consistently, and a third analyst’s role was to adjudicate any differences of opinion. We only assessed the official UPL transmitted to Congress and any supporting documentation provided at the same time or within the statutorily required 10-day time frame to submit the UPLs after the release of the President’s budget request.[51]

If we determined that an unfunded priority on the UPL addressed all aspects of an element, we rated it as “fully addressed.” If we determined that an unfunded priority on the UPL addressed some aspect of an element but not all aspects, then we rated it as “partially addressed.” If we determined that an unfunded priority on the UPL did not address any aspect of an element, we rated it as “not addressed.” With one exception, we did not include classified material in our assessments, so when agency documentation indicated that information related to an unfunded priority was contained in a classified attachment to the UPL, we rated those elements as “classified/did not assess.” Where components indicated that information needed to assess a particular element was classified, we did not include those priorities in our counts of whether “all” or “some” of the priorities addressed that specific element. In one instance related to U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, we did include a classified document in our assessment. In discussions with command officials, we noted the absence of two elements from many of the unfunded priorities on its unclassified UPL, and they indicated that the information might be in a classified attachment. Because the command cited this possibility, we reviewed the classified attachment to determine if the elements were addressed and included that review in our assessment. We also interviewed officials representing the components to discuss how they address the statutory elements.

We conducted this performance audit from May 2024 to September 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

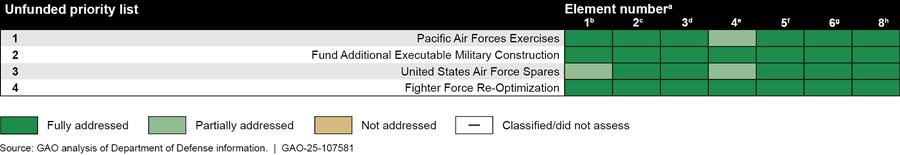

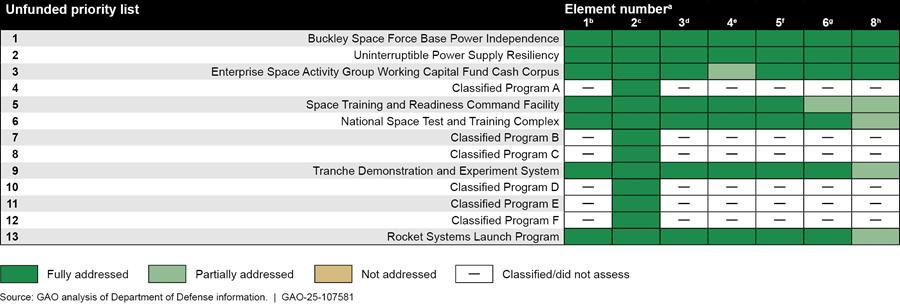

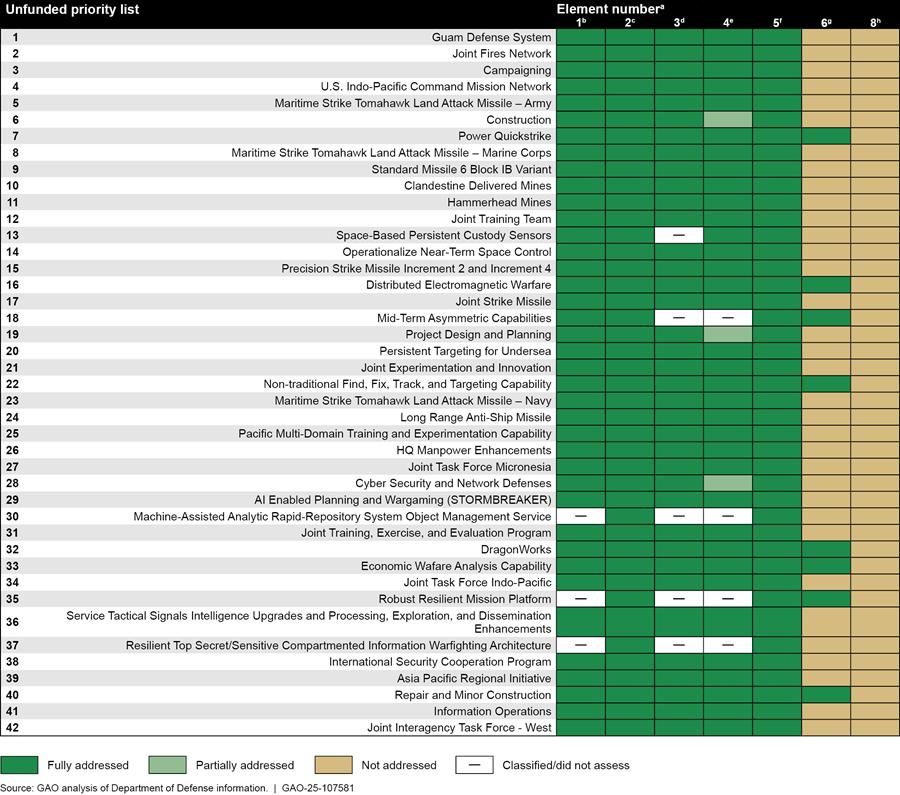

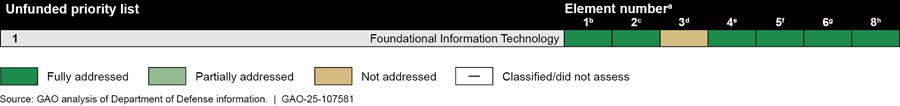

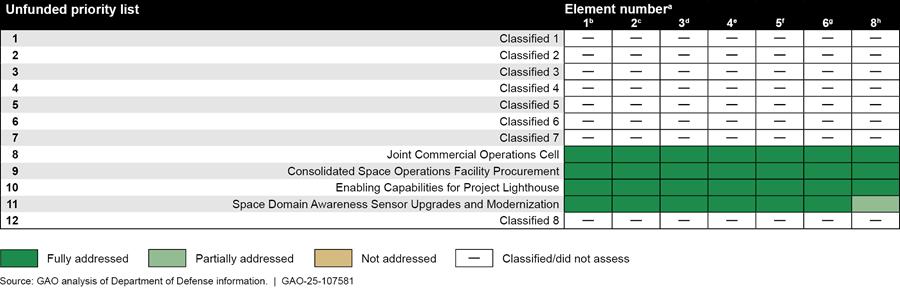

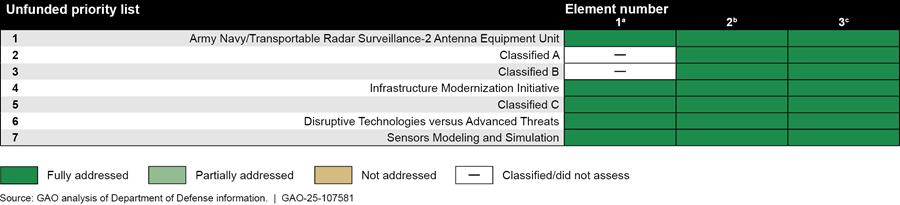

We assessed the fiscal year 2025 unfunded priority lists (UPLs) of selected Department of Defense (DOD) components for the presence of statutorily required elements (see figure 7).[52]

Note: We omitted the element describing funding provided in the current and preceding fiscal year for an unfunded priority because the Department of Defense’s final fiscal year 2024 appropriation was enacted after components had submitted their unfunded priority lists for fiscal year 2025. In the case of the Missile Defense Agency, there are only 3 required elements, which parallel the first 3 in this list.

In doing so, we considered a selected statutory element to be addressed for purposes of our review if it was at least minimally responsive to the statute for a given unfunded priority on its list. In this appendix, we further distinguish whether those unfunded priorities that addressed a statutory element either “fully addressed” the element, or “partially addressed” the element. Priorities might have received assessments of “partially addressed” by providing some, but not all, of the information required by statute. In instances where we assessed that a priority did not address a statutory element, we made recommendations to the relevant DOD component.

Air Force

In figure 8 we present our assessment of the Air Force’s efforts to address statutory elements in its fiscal year 2025 UPL submission. Of the 4 unfunded priorities submitted, we found the Air Force fully addressed five of the seven elements we assessed. For two of the seven, we found the Air Force had partially addressed the selected statutory elements for some of its priorities.

Figure 8: GAO Assessment of Selected Statutory Elements in Air Force’s Fiscal Year 2025 Unfunded Priority List

Notes:

aWe could not assess the element which asks for a description of funding provided for the requirement in the current and preceding fiscal years (element 7). The Department of Defense’s final fiscal year 2024 appropriation was enacted after components had submitted their unfunded priority lists for fiscal year 2025. Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2024, Pub. L. No. 118-47, div. A (March 23, 2024). As such, Department of Defense components could not provide information about current year funding of requirements to be addressed by unfunded priorities.

bA summary description of the priority, including the objectives outlined in the National Defense Strategy and the National Military Strategy to be advanced if the priority were funded in whole or in part.

cThe additional amount of funds recommended for the priority.

dPriority account information.

eA detailed assessment of each specific risk that would be reduced in executing the National Defense Strategy and the National Military Strategy if the priority were funded in whole or in part.

fThe requirement to be addressed by the unfunded priority.

gThe reason why funding for the priority was not included in the budget of the President.

hAn assessment of the effect that providing funding for the priority would have on the future-years defense plan.

The unfunded priorities that we assessed as partially addressing the UPL statute include those elements requiring a summary description related to the objectives in the National Defense Strategy and National Military Strategy, as well as the element related to the risk reduced to those objectives if the priority were funded. We assessed these as partially addressing the elements because it was not clear from the descriptions how those priorities related to the objectives in the strategies or reduced the risk of accomplishing them if the priorities were funded. However, in all other cases we found that the Air Force fully addressed the selected elements.

For its military construction priorities, the Air Force submitted one consolidated priority comprising 26 separate projects, which the Air Force identified in a separate part of its UPL submission. Those 26 individual military construction projects are not included in the figure above, but the one consolidated military construction priority is included. We considered the information related to those 26 individual military construction projects in our assessment of the one military construction priority on the Air Force’s list.

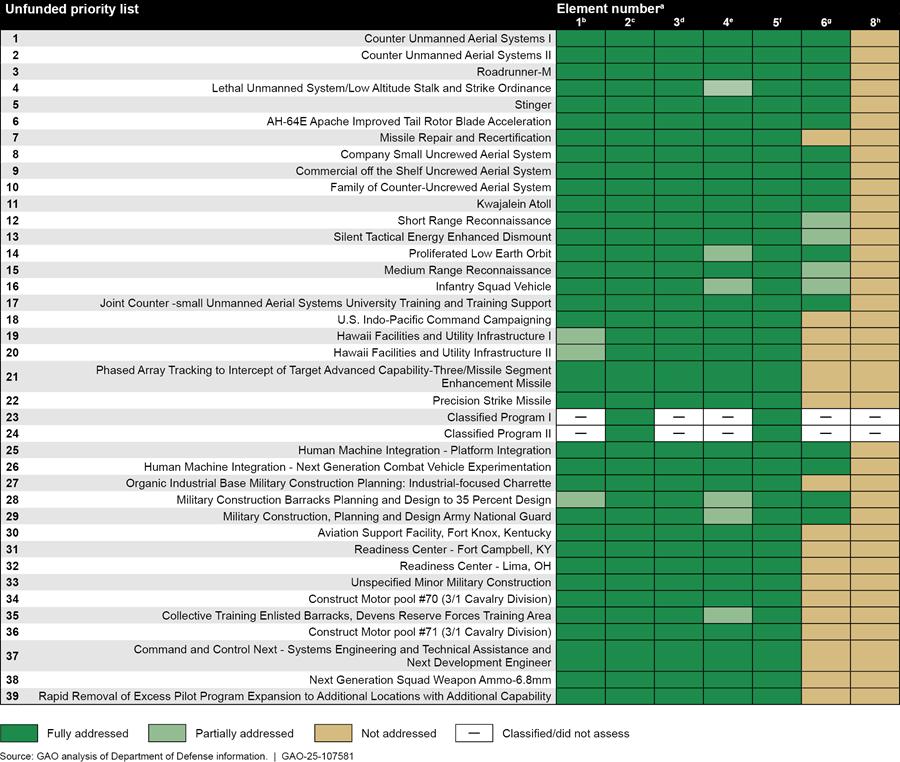

Army

In figure 9, we present our assessment of the Army’s efforts to address statutory elements in its fiscal year 2025 UPL submission. Of the 39 priorities submitted, we found the Army fully addressed three of the seven elements we assessed. For two of the others, we found the Army had either fully or partially addressed all statutory elements for its unfunded priorities. Two priorities had aspects that were classified, and we did not assess those priorities for those elements.

Figure 9: GAO Assessment of Selected Statutory Elements in Army’s Fiscal Year 2025 Unfunded Priority List

Notes:

aWe could not assess the element which asks for a description of funding provided for the requirement in the current and preceding fiscal years (element 7). The Department of Defense’s final fiscal year 2024 appropriation was enacted after components had submitted their unfunded priority lists for fiscal year 2025. Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2024, Pub. L. No. 118-47, div. A (March 23, 2024). As such, Department of Defense components could not provide information about current year funding of requirements to be addressed by unfunded priorities.

bA summary description of the priority, including the objectives outlined in the National Defense Strategy and the National Military Strategy to be advanced if the priority were funded in whole or in part.

cThe additional amount of funds recommended for the priority.

dPriority account information.

eA detailed assessment of each specific risk that would be reduced in executing the National Defense Strategy and the National Military Strategy if the priority were funded in whole or in part.

fThe requirement to be addressed by the unfunded priority.

gThe reason why funding for the priority was not included in the budget of the President.

hAn assessment of the effect that providing funding for the priority would have on the future-years defense plan.

For most priorities on its UPL, the Army fully addressed the statutory elements related to providing a summary description of the priority and how it relates to the objectives in the National Defense Strategy and National Military Strategy, as well as how funding the priority would reduce the risk to accomplishing those objectives. There were some unfunded priorities on the list where (1) the connection to the objectives in those strategies or (2) the risk reduced accomplishing the objectives if funding was provided was not as clear. We assessed those priorities as partially addressed for those two elements. Similarly, the Army identified a reason why some priorities were not included in the President’s budget request, or in other cases included language that may have been intended to be a reason but was not explicitly stated as such, and thus we assessed those as partially addressed. However, for most of its unfunded priorities the Army did not identify a reason. Finally, the Army did not describe the effect that funding any of the priorities on its list would have on the future-years defense plan (FYDP).[53]

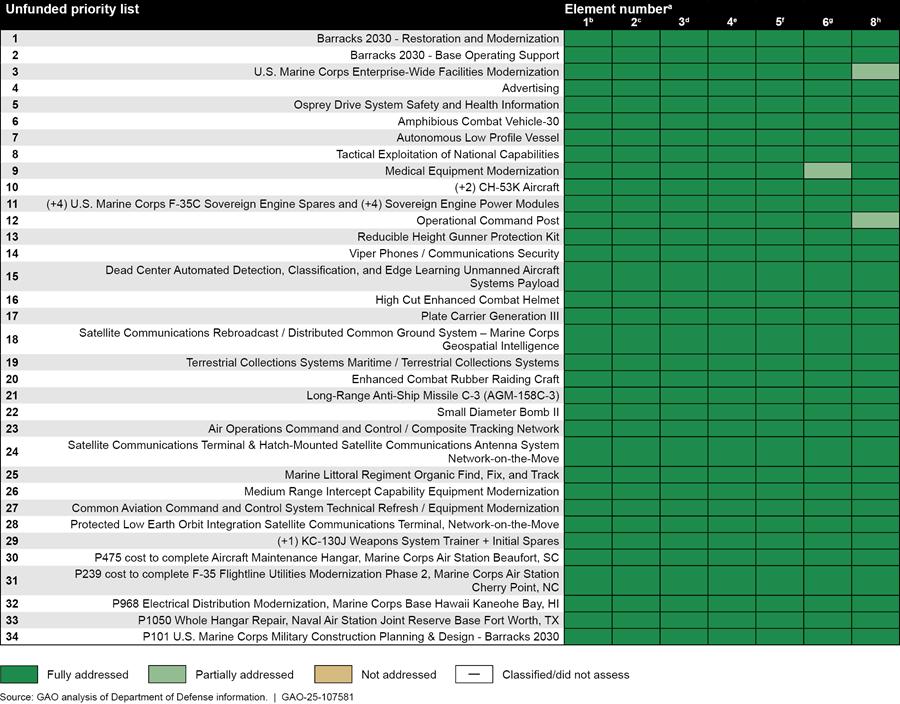

Marine Corps

In figure 10 we present our assessment of the Marine Corps’s efforts to address statutory elements in its fiscal year 2025 UPL submission. Of the 34 priorities submitted, we found the Marine Corps fully addressed five of the seven elements we assessed. For two of the seven selected elements, we found the Marine Corps had partially addressed them for some of its priorities.

Figure 10: GAO Assessment of Selected Statutory Elements in Marine Corps’s Fiscal Year 2025 Unfunded Priority List

Notes:

aWe could not assess the element which asks for a description of funding provided for the requirement in the current and preceding fiscal years (element 7). The Department of Defense’s final fiscal year 2024 appropriation was enacted after components had submitted their unfunded priority lists for fiscal year 2025. Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2024, Pub. L. No. 118-47, div. A (March 23, 2024). As such, Department of Defense components could not provide information about current year funding of requirements to be addressed by unfunded priorities.

bA summary description of the priority, including the objectives outlined in the National Defense Strategy and the National Military Strategy to be advanced if the priority were funded in whole or in part.

cThe additional amount of funds recommended for the priority.

dPriority account information.

eA detailed assessment of each specific risk that would be reduced in executing the National Defense Strategy and the National Military Strategy if the priority were funded in whole or in part.

fThe requirement to be addressed by the unfunded priority.

gThe reason why funding for the priority was not included in the budget of the President.

hAn assessment of the effect that providing funding for the priority would have on the future-years defense plan.

We assessed that the Marine Corps included a reason why the unfunded priorities on its UPL were not included in the President’s budget request for every priority on its list except one. We assessed that Marine Corps partially addressed the element for that unfunded priority by providing a reason, but the reason did not clearly explain why the priority could not have been included in the fiscal year 2025 President’s budget request. The Marine Corps also included the effect that funding the priorities on its UPL would have on the FYDP for every priority except two, which we also assessed as partially addressed because there was information related to the FYDP, but the effect was not clearly identified.

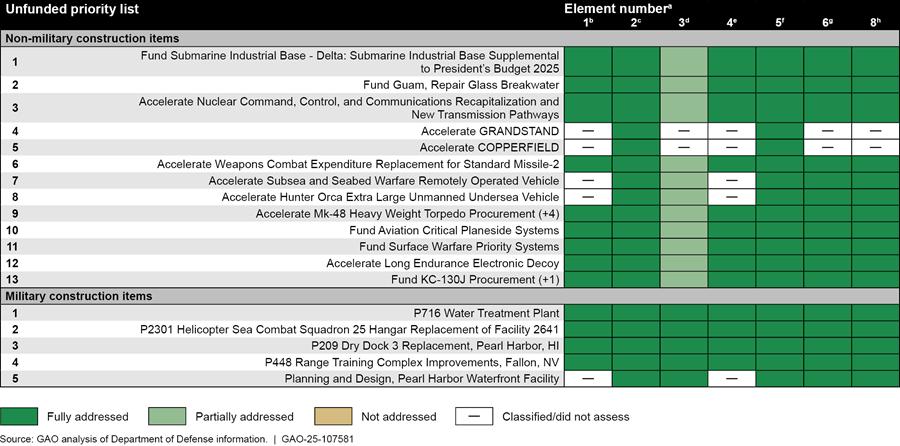

Navy

In figure 11, we present our assessment of the Navy’s efforts to address selected statutory elements in its fiscal year 2025 UPL submission. Of the 18 unfunded priorities submitted, we found the Navy fully addressed six of the seven elements we assessed. For the remaining element, we found the Navy had partially addressed the selected statutory element for some of its unfunded priorities. Five priorities had aspects that were classified, and we did not assess those priorities for those elements.

Figure 11: GAO Assessment of Selected Statutory Elements in Navy’s Fiscal Year 2025 Unfunded Priority List

Notes:

aWe could not assess the element which asks for a description of funding provided for the requirement in the current and preceding fiscal years (element 7). The Department of Defense’s final fiscal year 2024 appropriation was enacted after components had submitted their unfunded priority lists for fiscal year 2025. Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2024, Pub. L. No. 118-47, div. A (March 23, 2024). As such, the Department of Defense components could not provide information about current year funding of requirements to be addressed by unfunded priorities.

bA summary description of the priority, including the objectives outlined in the National Defense Strategy and the National Military Strategy to be advanced if the priority were funded in whole or in part.

cThe additional amount of funds recommended for the priority.

dPriority account information.

eA detailed assessment of each specific risk that would be reduced in executing the National Defense Strategy and the National Military Strategy if the priority were funded in whole or in part.

fThe requirement to be addressed by the unfunded priority.

gThe reason why funding for the priority was not included in the budget of the President.

hAn assessment of the effect that providing funding for the priority would have on the future-years defense plan.

Specifically, the unfunded priorities on the Navy’s list fully addressed every element except the one related to appropriation account information. For that element, the Navy identified the appropriation accounts but did not include the additional information, such as line-item numbers, program elements, or sub-activity groups. Therefore, we assessed those unfunded priorities as having partially addressed the required element. Navy officials stated that they did provide additional documentation to the congressional defense committees at a later date after the 10-day statutory deadline. We could not assess all of the selected elements for five of the Navy’s priorities due to classification.

The Navy’s submission included two lists—one with its unfunded non-military construction priorities and one with its unfunded military construction priorities. We also assessed the military construction list and found that those priorities fully addressed every selected element. One of the military construction priorities included some details that are classified.

Space Force

In figure 12, we present our assessment of the Space Force’s efforts to address selected statutory elements in its fiscal year 2025 UPL submission. Of the 13 unfunded priorities submitted, we found the Space Force fully addressed four of the seven elements we assessed. Six priorities had aspects that were classified, and we did not assess those priorities for those elements. For three of the seven selected elements, we found the Space Force had partially addressed the statutory elements for some of its priorities.

Figure 12: GAO Assessment of Selected Statutory Elements in Space Force’s Fiscal Year 2025 Unfunded Priority List

Notes:

aWe could not assess the element which asks for a description of funding provided for the requirement in the current and preceding fiscal years (element 7). The Department of Defense’s final fiscal year 2024 appropriation was enacted after components had submitted their unfunded priority lists for fiscal year 2025. Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2024, Pub. L. No. 118-47, div. A (March 23, 2024). As such, Department of Defense components could not provide information about current year funding of requirements to be addressed by unfunded priorities.

bA summary description of the priority, including the objectives outlined in the National Defense Strategy and the National Military Strategy to be advanced if the priority were funded in whole or in part.

cThe additional amount of funds recommended for the priority.

dPriority account information.

eA detailed assessment of each specific risk that would be reduced in executing the National Defense Strategy and the National Military Strategy if the priority were funded in whole or in part.

fThe requirement to be addressed by the unfunded priority.

gThe reason why funding for the priority was not included in the budget of the President.

hAn assessment of the effect that providing funding for the priority would have on the future-years defense plan.

Space Force fully addressed the element related to assessing the risk reduced to accomplishing the strategic objectives in the National Defense Strategy and the National Military Strategy for all but one of its unfunded priorities. For that priority, we could infer how the risk might be reduced but it was not explicitly stated, so we rated it as partially addressed. Space Force also fully addressed the element related to providing a reason why the priorities were not included in the President’s budget request for all but one of its unfunded priorities. For that unfunded priority, Space Force provided a response, but it was not clear in the response why or whether the priority was considered as part of the President’s fiscal year 2025 budget request. Finally, for the element related to identifying the effect of funding the priority on the FYDP, Space Force fully addressed the element for three of its unfunded priorities and partially addressed it for four of its unfunded priorities. For those four priorities, Space Force provided information describing potential future effects, but did not provide estimates or whether there would be a future cost associated with those effects.

Six of the priorities on Space Force’s list included classified aspects to them, which we did not include in our assessment. Additionally, like the Air Force UPL, Space Force included an unfunded priority for military construction on its list, along with a separate list with additional details on the specific military construction project. There was only one military construction project comprising the entry, and we included the details that Space Force provided in that separate table in our overall assessment.

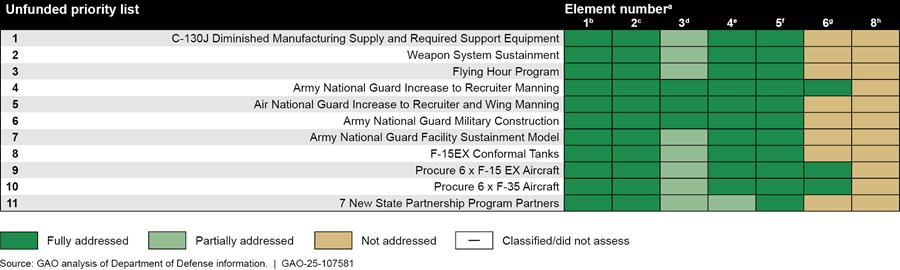

National Guard Bureau

In figure 13, we present our assessment of the National Guard’s efforts to address selected statutory elements in its fiscal year 2025 UPL submission. Of the 11 priorities submitted, we found the National Guard Bureau fully addressed three of the seven elements we assessed. For two of the others, we found the National Guard Bureau had either fully or partially addressed the statutory elements for its unfunded priorities.

Figure 13: GAO Assessment of Selected Statutory Elements in National Guard Bureau’s Fiscal Year 2025 Unfunded Priority List

Notes:

aWe could not assess the element which asks for a description of funding provided for the requirement in the current and preceding fiscal years (element 7). The Department of Defense’s final fiscal year 2024 appropriation was enacted after components had submitted their unfunded priority lists for fiscal year 2025. Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2024, Pub. L. No. 118-47, div. A (March 23, 2024). As such, Department of Defense components could not provide information about current year funding of requirements to be addressed by unfunded priorities.

bA summary description of the priority, including the objectives outlined in the National Defense Strategy and the National Military Strategy to be advanced if the priority were funded in whole or in part.

cThe additional amount of funds recommended for the priority.

dPriority account information.

eA detailed assessment of each specific risk that would be reduced in executing the National Defense Strategy and the National Military Strategy if the priority were funded in whole or in part.

fThe requirement to be addressed by the unfunded priority.

gThe reason why funding for the priority was not included in the budget of the President.

hAn assessment of the effect that providing funding for the priority would have on the future-years defense plan.

For the element related to account information, the National Guard Bureau included appropriation accounts, which was sufficient to address the element for its military construction and military personnel priorities. But it only partially addressed its other priorities because it did not include line-item numbers, program elements, or sub-activity groups. National Guard Bureau officials stated that they did provide the full account information, including line-item numbers and sub-activity groups, the day after the UPL deadline when it was requested by a congressional subcommittee. The National Guard Bureau did address the reason that three of its priorities were not included in the President’s budget request, but did not provide a reason for the other eight priorities. Finally, the National Guard Bureau did not provide information on the effect on the FYDP of funding any of the priorities on its UPL. We did not assess one unfunded priority which the National Guard Bureau initially submitted but later removed from its list.

U.S. Indo-Pacific Command