BEHAVIORAL HEALTH

Federal Activities to Support Crisis Response Services

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO-25-107586. For more information, contact Alyssa M. Hundrup at HundrupA@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107586, a report to congressional committees

Federal Activities to Support Crisis Response Services

Why GAO Did This Study

Behavioral health conditions affect millions of Americans, and these numbers continue to grow. GAO has reported on multiple nationwide behavioral health issues, including longstanding shortages in the behavioral health provider workforce. Delays in accessing behavioral health care have been common and may increase the risk that an individual experiences a crisis.

SAMHSA has provided resources, such as funding, to states and others to enhance behavioral health services, including crisis response services. In March 2025, HHS announced that it would consolidate SAMHSA into a new Administration for a Healthy America. As of August 25, 2025, this transition had not yet occurred.

The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023, includes a provision for GAO to review SAMHSA’s behavioral health crisis response programs. Among other things, this report describes SAMHSA’s behavioral health crisis response efforts and how selected states used SAMHSA resources to support their crisis response activities through May 2025.

GAO reviewed SAMHSA data and documentation from 2020 through May 2025, and interviewed agency officials. GAO also reviewed documentation and interviewed behavioral health department officials from five states. These states—Arizona, Georgia, Oklahoma, Virginia, and Washington—were selected to reflect geographic variation among those with a high capacity to respond to crisis response needs in their state.

What GAO Found

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), an agency within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), has worked to reduce the effect of mental illness and substance use disorders—collectively referred to as behavioral health conditions. A behavioral health crisis, which can happen to anyone, puts an individual at risk of hurting themselves or others. Crisis response services can reduce the risk of immediate harm and help prevent future crises by providing access to behavioral health providers.

GAO found that from 2020 through May 2025, SAMHSA provided resources—guidance, funding, and technical assistance—to states and others, such as behavioral health clinics, to support crisis response services. For example,

· Guidance. SAMHSA issued guidance outlining best practices for providing crisis response services. In it, SAMHSA described the importance of offering a range of services across a continuum of care, which includes (1) someone to contact—contact centers, (2) someone to respond—mobile crisis teams, and (3) a safe place for help—crisis stabilization.

· Funding. GAO found that SAMHSA provided over $1.3 billion through 10 programs in fiscal years 2021 through 2024 to support states and others in developing and providing crisis response services. Five programs supported the 2022 launch of the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline—an easy-to-remember phone number that links those in crisis to a counselor. Other programs provided funding to support mobile crisis teams that provide in-person treatment and assessment.

· Technical assistance. SAMHSA offered trainings, expert panels, and other assistance to help states enhance their crisis response services.

The five selected states in GAO’s review used SAMHSA resources to support behavioral health crisis response services in a variety of ways across the continuum of care through May 2025. For example, officials from all five states said they used SAMHSA funding to hire staff to increase responsiveness to individuals in crisis. Others invested in infrastructure such as by building data-sharing platforms to help improve care coordination, according to state officials.

Note: For more details, see fig. 2 in GAO-25-107586.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

988 Lifeline |

988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline |

|

HHS |

Department of Health and Human Services |

|

SAMHSA |

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

September 4, 2025

The Honorable Bill Cassidy, M.D.

Chair

The Honorable Bernard Sanders

Ranking Member

Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions

United States Senate

The Honorable Brett Guthrie

Chairman

The Honorable Frank Pallone, Jr.

Ranking Member

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

Behavioral health conditions, which include mental health conditions and substance use disorders, affect millions of people in the United States and these numbers continue to grow.[1] In 2023, an estimated 85 million adults (33 percent) and 6 million adolescents (23 percent) had a behavioral health condition, according to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).[2] A behavioral health crisis puts individuals at risk of hurting themselves or others.[3] Anyone, including individuals with behavioral health conditions, can experience such a crisis. Similar to a physical health crisis, a behavioral health crisis can be devastating for individuals, families, and communities.

Providing care to individuals experiencing a behavioral health crisis can serve to reduce the risk of immediate harm as well as provide a gateway to further treatment and prevention of future crises. However, delays in accessing care have been common and may increase the risk that an individual experiences a behavioral health crisis. We have reported longstanding shortages in the behavioral health provider workforce, and as of 2019, the national average wait time for behavioral health care was 48 days.[4] In 2023, about 85 percent of youth and adults with a substance use disorder did not receive treatment that year, and about a third of adults with a serious mental illness did not receive treatment, according to SAMHSA data.[5]

SAMHSA, an agency within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), works to reduce the effect of substance use and mental illness on America’s communities.[6] To do so, the agency provides resources, such as funding, to states and others, such as behavioral health clinics. These resources are aimed at enhancing behavioral health services—including crisis response services that offer individuals experiencing a crisis with timely access to behavioral health professionals. Among these efforts, SAMHSA maintains the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline (988 Lifeline), which launched in July 2022, as the easy-to-remember national dialing code for behavioral health crisis services.[7] The 988 Lifeline is available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, and is staffed by trained crisis counselors via call, text, or chat, who can help people experiencing a behavioral health crisis and connect them to additional crisis response services. Since its launch through July 2025, the 988 Lifeline has answered over 16 million calls, texts, and chats.

The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023, includes a provision for us to review SAMHSA’s behavioral health crisis response programs.[8] In this report, we describe

1. SAMHSA’s behavioral health crisis response efforts,

2. how selected states have used SAMHSA resources to support their behavioral health crisis response activities, and

3. the status of SAMHSA’s evaluations of its behavioral health crisis response efforts.

To describe SAMHSA’s behavioral health crisis response efforts, we reviewed SAMHSA documentation—including published guidance, program funding announcements, and reports—and interviewed SAMHSA officials. Specifically, we asked SAMHSA officials to identify and describe efforts supporting crisis response services from 2020 through May 2025, including the agency’s role in administering and coordinating these programs. We focused our review on efforts that directly aided the development and implementation of crisis response services.[9] In describing these efforts, we examined SAMHSA data on funding awarded to states and others in fiscal years 2021 through 2024, the latest data available during our review.[10] To determine the reliability of these data, we reviewed relevant documentation, interviewed knowledgeable agency officials, and reviewed the data for reasonableness by checking for obvious errors across multiple sources of SAMHSA awards information. Based on these steps, we determined that these data were sufficiently reliable for the purpose of our reporting objective.

To describe how selected states have used SAMHSA resources to support their behavioral health crisis response activities, we reviewed documents and interviewed behavioral health department officials from five states: Arizona, Georgia, Oklahoma, Virginia, and Washington. We selected these states to provide geographic variation among a set of states that received SAMHSA funding to support their behavioral health crisis response activities and had demonstrated a high capacity to respond to the behavioral health crisis needs of their state.[11] For each state, we reviewed program documents submitted to SAMHSA, such as grant progress reports, that described states’ use of SAMHSA resources. In addition, we interviewed state behavioral health department officials about their crisis response activities, including how SAMHSA resources—guidance, funding and technical assistance—supported these activities. We updated this information through May 2025.

To describe the status of SAMHSA’s evaluations of its behavioral health crisis response efforts, we reviewed SAMHSA documentation, such as the agency’s evaluation plans for its 988 Lifeline and certified community behavioral health clinic grant programs. We also interviewed SAMHSA officials about the status and progress of any planned and ongoing evaluations through May 2025.

We conducted this performance audit from May 2024 to September 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

SAMHSA and State Roles in Behavioral Health Crisis Response

SAMHSA’s mission is to lead public health and service delivery efforts that promote mental health, prevent substance abuse, and provide treatments and supports to foster recovery while ensuring access and better outcomes. The agency implements these efforts by providing resources, such as funding, to states and others—including counties, Tribes, and health care providers—that are responsible for delivering substance use and mental health services, including behavioral health crisis services.

To meet the needs of their jurisdictions, states and others often combine, or braid, SAMHSA funding with other funds, including state appropriations and payments from Medicaid and private insurance. As a result of disparate needs and priorities of each state and differences in the availability of funding, states collectively exhibit a range of capacity in offering behavioral health crisis services.[12]

Behavioral Health Crisis Response Services and the Continuum of Care

Behavioral health crisis response services provide access to behavioral health professionals for individuals experiencing mental health or substance use-related crises and offer an alternative to emergency departments and law enforcement intervention. According to SAMHSA, behavioral health crisis service providers should strive to offer a range of crisis response services 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.[13] Available services should ideally vary in intensity, duration, range of behavioral health professionals, and care settings to meet the level of acuity of an individual’s crisis.

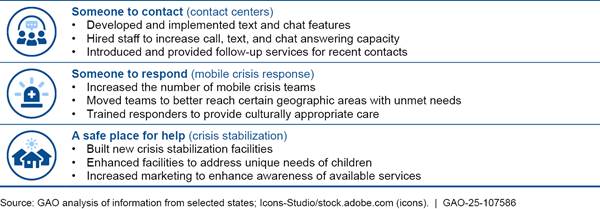

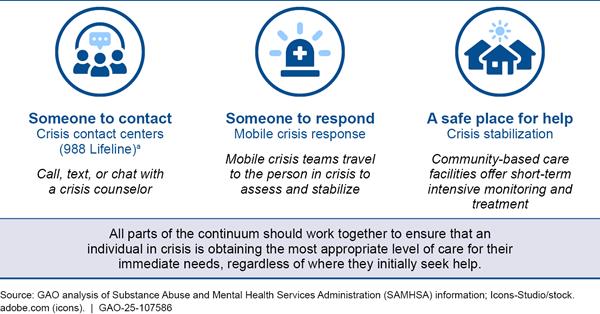

SAMHSA refers to the range of crisis response services ideally available to individuals as the behavioral health crisis response continuum of care. This continuum consists of (1) someone to contact, (2) someone to respond, and (3) a safe place for help.

· Someone to contact. Crisis contact centers, including the 988 Lifeline, offer free and accessible virtual support through call, text, or chat to individuals experiencing a crisis. Trained crisis counselors use a range of techniques to resolve a crisis. Contact center staff may also refer the individual to additional services for further assessment and treatment or call for emergency services if immediate assistance is needed. All 50 states provide live crisis counseling services through the 988 Lifeline; however, states vary in both their capacity to staff their contact centers and to respond to calls originating in their state.[14]

· Someone to respond. Where available, mobile crisis response teams travel to the location of individuals experiencing a crisis to provide an array of in-person assessments and interventions. Teams are responsible for assessing and stabilizing the individual, providing brief treatment, ensuring their safety, and providing transport or coordinating higher levels of care as needed. These teams may include a combination of behavioral health professionals, including crisis counselors, social workers, and certified peer specialists.[15] According to SAMHSA, 44 states reported supporting or working to establish mobile crisis teams in 2022; however, only 20 states offered statewide coverage 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.[16]

· A safe place for help. Crisis stabilization services can be provided at community-based facilities equipped to support a range of crisis severity. Where available, these services include walk-in urgent care, initial substance use detoxification, short-term peer support, and beds for 24-hour monitoring. Crisis stabilization services typically transition individuals to longer-term care, such as peer-supported recovery housing services, as needed. According to SAMHSA, 34 states offered crisis stabilization services in 2022. However, SAMHSA found that ensuring these programs are available statewide and 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, has been a challenge for nearly all states.[17]

See figure 1 for an illustration of SAMHSA’s behavioral health crisis response continuum of care.

Notes: SAMHSA described the full range of behavioral health crisis response services across the continuum of care in its 2025 National Guidelines for Behavioral Health Coordinated System of Crisis Care. The availability of these services varies by location, with contact centers being the most accessible, according to SAMHSA. Information presented reflects our analysis of SAMHSA information through May 2025.

a988 Lifeline refers to the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline, a network of contact centers staffed by trained crisis counselors via call, text, or chat, who can help people experiencing a behavioral health crisis and connect them to additional services.

SAMHSA Provided Guidance, Funding, and Technical Assistance to Support Behavioral Health Crisis Response

Based on our review of SAMHSA’s crisis response efforts from 2020 through May 2025, we found that SAMHSA issued guidance and provided funding and technical assistance to help states and others develop and coordinate their behavioral health crisis response services. Collectively, these resources supported the provision of behavioral health crisis response services across the continuum of care.

Guidance. SAMHSA issued several guidance documents to support states and others in developing and coordinating an array of behavioral health crisis response services for individuals in crisis. In 2020, SAMHSA issued its first guidance on crisis response services, which included a description of the crisis response continuum of care and best practices for implementation of related services.[18] From 2022 through May 2025, SAMHSA expanded upon and updated this guidance to include information on special considerations for providing crisis response services to children and families, incorporated information about the 988 Lifeline, and defined key terms used in crisis care settings.[19] Collectively, these guidance documents addressed the provision of crisis response services across the continuum of care and included considerations for serving a range of populations. See table 1 for a summary of SAMHSA’s crisis response guidance from 2020 through 2025.

|

Title |

Year issued |

Description |

|

National Guidelines for Behavioral Health Crisis Care: Best Practice Toolkit |

2020 |

National guidance for the implementation and coordination of state and local crisis response services, such as contact centers, mobile crisis response teams, and crisis stabilization facilities. |

|

National Guidelines for Child and Youth Behavioral Health Crisis Care |

2022 |

National guidance for crisis response services specific to the needs of children, youth, and families, including strategies to support youth at home and keep families intact. |

|

Connecting Communities to Substance Use Services: Practical Approaches for First Responders |

2023 |

Guidance for first responders, such as law enforcement and emergency medical service personnel, about effective interactions with people experiencing a substance use-related crisis and connections to community substance use services. |

|

Saving Lives in America: 988 Quality and Services Plan |

2024 |

National operational and technical requirements for the administration of the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline (988 Lifeline) network, including minimum requirements for crisis contact centers, such as counselor training, contact routing, cybersecurity, privacy, performance targets, and quality assurance. |

|

Advising People on Using 988 Versus 911: Practical Approaches for Healthcare Providers |

2024 |

Guidance for providers, including primary care and emergency medical services, about the availability and appropriate use of the 988 Lifeline compared to 911. The guidance offers steps for integrating crisis care into daily practice, crisis scenarios, and de-escalation techniques. |

|

2025 National Guidelines for Behavioral Health Coordinated System of Crisis Care |

2025 |

SAMHSA updated its 2020 guidance to incorporate the 988 Lifeline launch in 2022, to update guidance for substance use disorder crisis response services, and to emphasize coordination across the continuum of care. |

|

Model Definitions for Behavioral Health Emergency, Crisis, and Crisis-Related Services |

2025 |

SAMHSA further supplemented its 2025 updated national guidance with uniform definitions and descriptions for services within the crisis response continuum of care. |

Source: GAO analysis of Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) information. | GAO‑25‑107586

Note: Information presented reflects our analysis of SAMHSA information through May 2025.

Funding. We found that, in fiscal years 2021 through 2024, SAMHSA awarded over $1.3 billion to states and others, such as 988 Lifeline contact centers, through 10 programs to support the development and provision of crisis response services. SAMHSA directed some of this funding to support a particular area of the behavioral health crisis response continuum, and, in some cases, included flexibility for awardees to choose how to use it to enhance crisis response services. Separately, through three of the 10 programs, SAMHSA awarded an additional $2.3 billion to support general behavioral health services—offering awardees (behavioral health clinics and states) flexibility in using this funding, which could include the provision of crisis response services.

· Contact centers. In fiscal years 2021 through 2024, SAMHSA awarded over $1.1 billion through five programs to support the 988 Lifeline—a nationwide network of crisis contact centers that provide crisis counseling and referral services to people experiencing a behavioral health crisis. One program designated and provided funding for a 988 Lifeline administrator to operate the network by developing and operating the 988 Lifeline contact center network infrastructure, establishing system requirements, providing technology support, and implementing counselor training standards.[20] Funding to four other programs supported states, Tribes, and others in their efforts to build and improve the 988 Lifeline network, including hiring and training staff, and to expand efforts to provide after-contact support. See table 2 for a description of 988 Lifeline programs funded by SAMHSA.

Table 2: SAMHSA-Funded 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline (988 Lifeline) Programs, Fiscal Years 2021-2024

|

Program |

Total award amount (dollars in millions) |

Total number of awardees |

Description |

|

988 Lifeline network administrator |

$536 |

Nationwide network administrator (one nonprofit organization) |

Managed the national implementation of the 988 Lifeline network, including technical and infrastructure support for states and backup contact centers. |

|

Build 988 Lifeline capacity |

$151 |

48 states, the District of Columbia, and five U.S. territories |

Supported the development of infrastructure (e.g., contact centers, counselor staffing, and call routing) to respond to 988 Lifeline calls, texts, and chats originating within the state. |

|

Improve 988 Lifeline capacity |

$355 |

47 states, the District of Columbia, and five U.S. territories |

Supported efforts to improve the capabilities of 988 Lifeline contact centers, such as building capacity to answer a higher call volume and enhancing contact center technology and data security. |

|

988 Lifeline crisis center follow-up |

$10 |

10 contact centers |

Supported contact centers in connecting 988 Lifeline callers with local services and follow-up outreach. |

|

988 Lifeline tribal responsea |

$54 |

38 Tribes |

Supported contact center services for American Indian and Alaska Native 988 Lifeline callers, including integration with after-contact support and connection to follow-on services. |

Source: GAO analysis of Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) information. | GAO‑25‑107586

Notes: Information presented reflects our analysis of SAMHSA information through May 2025. All 50 states received funding through at least one of the SAMHSA-funded 988 Lifeline programs.

aThis includes two separate SAMHSA programs that provided funding for 988 Lifeline tribal response efforts.

· Mobile response services. SAMHSA awarded $45 million to 25 state and local entities in fiscal years 2022 through 2024 to support the development of mobile crisis response services for adults, children, and youth in high-need communities through its Community Crisis Response Partnership program. SAMHSA established this program in 2022 to assist local communities in enhancing these services, including by increasing the number of two-person mobile crisis teams staffed by behavioral health professionals (e.g., social workers, crisis counselors, and certified peer specialists), tracking mobile response times across service areas, and incorporating telehealth services to increase access for rural and remote communities.

· Flexible funding. We found that through the Community Mental Health Services Block Grant requirement to set aside at least 5 percent of the grant amount for evidence-based crisis services, SAMHSA required awardees to collectively spend at least $219 million to enhance crisis response services in fiscal years 2021 through 2024.[21] These funds offered states the flexibility to support crisis response services across the continuum of care based on their needs.

In addition to the $1.3 billion SAMHSA directed to support crisis response services in fiscal years 2021 through 2024, the agency awarded $2.3 billion through two programs supporting certified community behavioral health clinics.[22] SAMHSA requires certified clinics to offer behavioral health services regardless of an individual’s ability to pay and to provide crisis stabilization services 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Separately, through another program, SAMHSA awarded 15 state behavioral health authorities with up to $1 million each in fiscal year 2023 for their efforts in assisting these community-based clinics with attaining certification.

Technical assistance. As of May 2025, SAMHSA administered six technical assistance programs that supported states and others in the development, planning, and implementation of behavioral health crisis response services. This technical assistance included trainings, publications, webinars, and real-time information sharing and feedback sessions.

Some technical assistance programs directly supported awardees in the implementation of specific SAMHSA crisis response funding programs, while others supported general efforts to enhance crisis response services. For example, the State Program Improvement Technical Assistance program supported states’ planning and use of Community Mental Health Services Block Grant funds, including the required 5 percent for crisis response services. In contrast, the Crisis Systems Response Training and Technical Assistance Center was available to any state and local crisis response providers implementing an array of crisis response-related services, including the development of the 988 Lifeline contact center network. See appendix I for a description of SAMHSA’s six crisis response technical assistance programs.

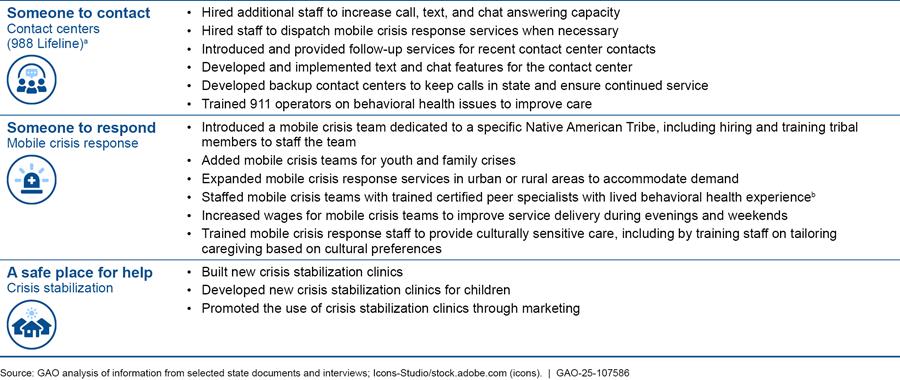

Selected States Used SAMHSA Resources to Enhance Their Crisis Response Services

The five selected states we reviewed—Arizona, Georgia, Oklahoma, Virginia, and Washington—used SAMHSA resources, including guidance, funding, and technical assistance, in a variety of ways to enhance their behavioral health crisis response services across the continuum of care. These states, which had demonstrated a high capacity to respond to crisis response needs of their state, used SAMHSA resources to further enhance these services. Collectively, we found that these five states used SAMHSA resources to directly enhance the services they provided through their contact centers, mobile crisis teams, and crisis stabilization facilities.[23] For example, all states used funding to hire additional crisis response staff to increase responsiveness, and some states added new services such as mobile crisis teams. See figure 2 for examples of selected state efforts to enhance crisis response services using SAMHSA resources.

Figure 2: Examples of Selected States’ Efforts to Enhance Crisis Response Services Using SAMHSA Resources

Notes: Selected states include Arizona, Georgia, Oklahoma, Virginia, and Washington. Information presented reflects our analysis of states’ use of Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) resources, which includes guidance, funding, and technical assistance, through May 2025.

a988 Lifeline refers to the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline, a network of contact centers staffed by trained crisis counselors via call, text, or chat who can help people experiencing a behavioral health crisis and connect them to additional services.

bCertified peer specialists are state-certified individuals with lived experience who have sustained recovery from a mental or substance use disorder, or both. Their role is to help people enter and stay engaged in the recovery process and reduce the likelihood of relapse.

We also found the five selected states invested in infrastructure to enhance their crisis response services. This enabled them to more readily understand and deliver services to address the needs of their populations. For example, officials from three states told us they used SAMHSA funding and technical assistance to develop or improve a digital registry to track crisis bed availability. According to SAMHSA, this tool allows contact center staff and mobile crisis responders to more efficiently refer and transport, as necessary, individuals to facilities that offer the appropriate crisis response services and have available space for them to receive treatment. See table 3 for other examples of how our selected states developed infrastructure to better assess and respond to the needs of their populations.

Table 3: Examples of Selected States’ Efforts to Enhance Crisis Response Infrastructure Using SAMHSA Resources

|

State |

Infrastructure |

Description |

|

Arizona |

Assessment of needs |

Arizona conducted an assessment to identify what additional crisis response infrastructure and services were most needed in the state. Based on the results of the assessment, it added new services. Specifically, Arizona introduced a mobile crisis response team in a rural area to decrease wait times and hired additional mobile crisis response staff to provide night and weekend coverage to an urban area that was facing a staffing shortage. |

|

Georgia |

911 and 988 Lifeline coordinationa |

Georgia leveraged SAMHSA guidance and technical assistance to improve coordination between 911 and the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline (988 Lifeline) contact center operators. For example, the state developed a script for 911 operators to use when an individual calls with a behavioral health issue. They also provided training on behavioral health issues to 911 operators to improve awareness of these issues. Georgia’s crisis response contact center has a dedicated line for transferring 911 calls to the 988 Lifeline. |

|

Oklahoma |

Law enforcement iPad program |

Oklahoma distributed iPads to law enforcement, emergency departments, and individuals discharged from crisis stabilization facilities to enable them to immediately connect individuals in crisis to behavioral health care professionals staffed at crisis stabilization facilities. This program has enabled the state to reduce costs because individuals can be immediately assessed by behavioral health care professionals, and therefore they can be more quickly connected to an appropriate level of care. |

|

Virginia |

Crisis response data-sharing platform |

Virginia developed and deployed a data-sharing platform to connect crisis response providers across the continuum of care, such as providing referrals for mobile crisis response. With this tool, responders of all types can coordinate to connect and refer individuals in crisis to an appropriate level of care and follow-up services through emails, text messages, or calls. |

|

Washington |

988 Lifeline network for Native Americans |

Washington used SAMHSA funding to support a statewide 988 Lifeline network to address the unique needs of Native Americans. Designed for and by Native Americans, the state’s Native and Strong Lifeline links 988 Lifeline callers with Native American crisis counselors trained in crisis intervention and support. Anyone who calls the 988 Lifeline in Washington has the option to be directly connected to the Native and Strong Lifeline. In addition to providing real-time support emphasizing cultural and traditional values, counselors are able to link callers with culturally appropriate follow-up services. |

Source: GAO analysis of state and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) documents and interviews. | GAO‑25‑107586

Note: Information presented reflects our analysis of states’ use of SAMHSA resources through May 2025.

aUnless otherwise stated, 988 Lifeline refers to the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline, a network of contact centers staffed by trained crisis counselors via call, text, or chat who can help people experiencing a behavioral health crisis and connect them to additional services.

SAMHSA’s Evaluations of Its Crisis Response Efforts Were Largely in the Planning Stages

SAMHSA’s evaluations of its behavioral health crisis response efforts were largely in the planning stages and focused on two programs, as of May 2025. One of the two program evaluations focused on the 988 Lifeline. In September 2023, SAMHSA hired a contractor to plan and perform an evaluation, including an assessment of the implementation and effects of the 988 Lifeline and its interaction with the crisis response continuum of care. In April 2024, the contractor issued a SAMHSA-approved evaluation plan, which includes five distinct studies, such as an evaluation of coordination across the continuum of care, use of crisis response services, and effect on individual outcomes such as suicide and overdose deaths. According to its plan, the contractor will begin collecting data to support all five studies in fiscal year 2025 and will provide final evaluation findings for all five studies to the agency in fiscal year 2028.[24] As of May 2025, SAMHSA officials planned to continue this evaluation and noted that the contractor had started collecting data. Table 4 describes each component of the evaluation.

Table 4: Summary of SAMHSA’s 988 Lifeline and Crisis Services Program Evaluation Plan, Fiscal Years 2024-2028

|

Evaluation component |

Purpose |

|

System Composition and Collaboration Study |

To describe the structure of the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline (988 Lifeline) and other components of the behavioral health crisis response continuum of care, including mobile crisis response and crisis stabilization, and highlight potential areas for improvement such as practices that contribute to more effective and efficient coordination and delivery of crisis response services. |

|

System-Level Service Utilization Study |

To provide information about how the 988 Lifeline and the continuum of care affect the use of crisis response services across the continuum. This study offers the opportunity to identify successes and areas where additional support is needed to ensure that appropriate services are provided during and after a behavioral health crisis. |

|

Client-Level Service Utilization and Outcome Study |

To provide insight into the effect of the 988 Lifeline and related crisis response services across the continuum of care on individuals who experience a behavioral health crisis and help identify opportunities to improve the implementation of crisis response services. |

|

Client-Level Risk Reduction Study |

To collect data on the effectiveness of contacting the 988 Lifeline as reported by individuals seeking and using crisis response services and provide information on how and whether the 988 Lifeline and related crisis response services reduce immediate risks of suicide, violence toward others, or overdose. |

|

Impact Evaluation Study |

To examine the overall effect of the 988 Lifeline and crisis response services on the outcomes of adverse crisis-related events such as suicide or overdose deaths. |

Source: GAO analysis of Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) documentation. | GAO‑25‑107586

Notes: Information presented reflects our analysis of SAMHSA’s 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline and Crisis Services Program Evaluation Plan through May 2025. 988 Lifeline refers to the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline, a network of contact centers staffed by trained crisis counselors via call, text, or chat who can help people experiencing a behavioral health crisis and connect them to additional services.

As of May 2025, SAMHSA officials said they were also evaluating the Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinic programs, which support states and others in providing community-based behavioral health services, including crisis response services. In May 2023, the agency hired a contractor to develop an evaluation plan to assess the development, implementation, and sustainability of the participating clinics. In February 2024, SAMHSA also updated the measures that these clinics are required to report, including one related to the timeliness of crisis response services. SAMHSA officials told us that, as of May 2025, initial data collection efforts were beginning, and they expected to review evaluation results annually for each year of the contract. According to the evaluation plan, the contractor planned to collect a variety of data for this evaluation including from interviews and surveys of clinic directors on their experiences, challenges, and linkages with other providers such as 988 Lifeline contact centers.

In addition to its efforts to evaluate these two programs, SAMHSA has reviewed routine program data reported by awardees for other behavioral health crisis response efforts to monitor program implementation, according to agency officials. While these efforts are not formal evaluations, they help ensure agency efforts are being implemented as intended. For example, SAMHSA officials told us the agency reviewed monthly reports prepared by the Crisis Systems Response Training and Technical Assistance Center contractor to ensure the center’s technical assistance, such as webinars, trainings, and other materials, aligned with SAMHSA’s requirements and guidance. SAMHSA officials told us they also reviewed awardee-reported data for its funding programs, such as contact center answer rates for the 988 Lifeline funding programs, to monitor the awardees’ progress towards completing program requirements.

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to HHS for review and comment. HHS provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Health and Human Services, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at HundrupA@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix II.

Alyssa M. Hundrup

Director, Health Care

As of May 2025, we identified six Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) technical assistance programs that provided ongoing support for the development and enhancement of behavioral health crisis response services.

· Crisis Systems Response Training and Technical Assistance Center. Provided technical assistance to state and local crisis response entities, including support for the integration of the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline (988 Lifeline) with 911 and mobile crisis response services; meetings and webinars with experts and leaders in mental health and substance use crisis response services; and materials for policymakers, agency leadership, and the crisis response services’ workforce.

· State Program Improvement Technical Assistance. Supported states with planning and implementation of the Community Mental Health Services Block Grant, including the crisis services 5 percent “set aside.”[25] The program also convened and facilitated sessions for states to learn from other states about implementing behavioral health crisis response services and produced reports on the status and trends of such services.

· Technical Assistance Coalition. Provided support to states and others in the implementation of programs and services supported by SAMHSA resources, including the implementation of crisis response services in state and local behavioral health systems. Comprising a consortium of eleven behavioral health nongovernmental organizations, the program was associated with the Transformation Transfer Initiative, a competitive award program that supported state behavioral health projects, including some related to crisis response services.

· Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinic State Technical Assistance Center. Supported state planning and implementation of the Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinic model, including tailored state consultations, as well as trainings and other published materials.

· Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinic Expansion National Training and Technical Assistance Center. Provided training and guidance to health care clinics participating in SAMHSA’s Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinic programs on the development and delivery of services, including mobile crisis response and stabilization services.

· Gather, Assess, Integrate, Network, and Stimulate Center. Provided support and training for behavioral health and criminal justice professionals, states, and communities to expand access to services for people with mental health conditions or substance use disorders, including people experiencing behavioral health crises who encounter the adult criminal justice system.

GAO Contact

Alyssa M. Hundrup, HundrupA@gao.gov.

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Patricia Roy (Assistant Director), William Garrard (Analyst-in-Charge), Eric Chen, and Riley Grube made key contributions to this report. Also contributing were Sonia Chakrabarty, Laura Elsberg, David Jones, Diona Martyn, and Eric Peterson.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]We define behavioral health conditions as mental, emotional, and substance use disorders, which are often co-occurring. Examples of mental health conditions include anxiety disorders; mood disorders, such as depression; post-traumatic stress disorder; and schizophrenia. Examples of substance use disorders include alcohol use disorder and opioid use disorder.

[2]Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2023 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (Rockville, Md.: July 2024).

[3]A behavioral health crisis is a disruption in a person’s thoughts, emotions, behaviors, or functioning that puts an individual at risk of hurting themselves or others and leads to an urgent need for assessment and treatment to prevent the condition from worsening or becoming dangerous.

[4]GAO, Behavioral Health: Available Workforce Information and Federal Actions to Help Recruit and Retain Providers, GAO‑23‑105250 (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 27, 2022). We have also reported on a range other nationwide behavioral health issues. For more information, see GAO, Mental Health Care: Access Challenges for Covered Consumers and Relevant Federal Efforts, GAO‑22‑104597 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 29, 2022) and Health Care Capsule: Treatment for Drug Misuse, GAO‑25‑107640 (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 3, 2024).

The average wait time is based on the most recent information available from the following: Health Resources and Services Administration, National Center for Health Workforce Analysis, State of the Behavioral Health Workforce, 2024 (Rockville, Md.: Nov. 2024).

[5]Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators. Serious mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, affect about 14.6 million adults. They interfere with major life activities, such as the ability to care for oneself, sleep, eat, and work.

[6]On March 27, 2025, HHS announced that it would be restructuring the department, including by consolidating SAMHSA into a new Administration for a Healthy America. See Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Public Affairs, HHS Announces Transformation to Make America Healthy Again (Mar. 27, 2025). In May, several states filed a lawsuit challenging the March 27 announcement; litigation is ongoing. See New York v. Kennedy, No. 25-cv-00196 (D.R.I. May, 5, 2025). As of August 25, 2025, the transition to a new structure had not occurred and accordingly, we refer to the agency as SAMHSA throughout this report.

[7]See National Suicide Hotline Designation Act of 2020, Pub. L. No. 116-172, § 3, 134 Stat. 832, 832-22 (codified at 47 U.S.C. § 251(e)). See also 33 FCC Rcd. 7373 (2020); 36 FCC Rcd. 16901 (2021). SAMHSA has maintained the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline since 2005. One study of the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline reported that callers in 2020 and 2021 who were at risk for suicide found their crisis counselors to be helpful in reducing their immediate risk of suicide and creating a safety plan for a future crisis. See Madelyn S. Gould et al., “National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (Now 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline): Evaluation of Crisis Call Outcomes for Suicidal Callers,” Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, vol. 55, no. 3 (2025). SAMHSA transitioned to the 988 Lifeline in 2022.

[8]Pub. L. No. 117-328, §1102, 136 Stat. 4459, 5635 (2022).

[9]SAMHSA also supports a range of behavioral health programs that are indirectly related to crisis response, such as suicide prevention programs; we do not include such programs in this report.

[10]Specifically, we describe the amount of funding SAMHSA awarded through cooperative agreements and grant programs in fiscal years 2021 through 2024.

[11]Specifically, we selected states that (1) answered at least 80 percent of the 988 Lifeline calls placed in their states from May 2024 through August 2024 (instead of sending calls to backup contact centers that may be located out of state), and (2) according to SAMHSA, offered an array of crisis response services, in addition to those available through the 988 Lifeline. See 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline, “State-Based Monthly Reports,” accessed May 8, 2025; and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Connected and Strong Compendium: Strategies for Accessible and Effective Crisis and Mental Health Services, (Rockville, Md.: 2024).

[12]Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Snapshot of Behavioral Health Crisis Services and Related Technical Assistance Needs Across the U.S. (Updated Version); (Rockville, Md.: May 23, 2024).

[13]Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2025 National Guidelines for a Behavioral Health Coordinated System of Crisis Care; (Rockville, Md.: 2025).

[14]States that do not have adequate capacity to respond to calls originating in their state are able to reroute contacts to national backup contact centers for support.

[15]Certified peer specialists are individuals with lived experience who have sustained recovery from a mental illness or substance use disorder, or both, and have undergone special training or certification to be effective in their role to help people enter and stay engaged in the recovery process and reduce the likelihood of relapse or regression.

[16]Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Snapshot of Behavioral Health Crisis Services. The snapshot provides an overview of behavioral health crisis services states offer based on responses submitted by 48 state mental health agencies. Alternative crisis response services for individuals located in regions without mobile crisis services include law enforcement officers and emergency medical services.

[17]Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Snapshot of Behavioral Health Crisis Services.

[18]Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, National Guidelines for Behavioral Health Crisis Care: Best Practice Toolkit, (Rockville, Md.: 2020).

[19]Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, National Guidelines for Child and Youth Behavioral Health Crisis Care, (Rockville, Md.: 2022); Connecting Communities to Substance Use Services: Practical Approaches for First Responders, (Rockville, Md.: 2023); Saving Lives in America: 988 Quality and Services Plan, (Rockville, Md.: 2024); Advising People on Using 988 Versus 911: Practical Approaches for Healthcare Providers, (Rockville, Md.: 2024); 2025 National Guidelines for a Behavioral Health Coordinated System of Crisis Care; and Model Definitions for Behavioral Health Emergency, Crisis, and Crisis-Related Services, (Rockville, Md.: 2025).

[20]The 988 Lifeline administrator oversees the operations of the 988 Lifeline through a cooperative agreement with SAMHSA. In consultation with SAMHSA, the administrator implements service expectations, standards, and minimum requirements, and provides the clinical and technology resources necessary to deliver the 988 Lifeline.

[21]The Community Mental Health Services Block Grant program makes funds available to all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and eight U.S. territories to provide comprehensive community mental health services to adults and children with serious mental health conditions. SAMHSA determines the grant amount for each jurisdiction using a formula specified in statute that considers population needs and cost of services, among other factors. See 42 U.S.C. §§ 300x–-300x-9. In 2021, Congress directed SAMHSA to specify that grantees set aside 5 percent of their grant for evidence-based crisis systems. The set aside was codified in 2022. See Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023. Pub. L. No. 117-328, §1141, 136 Stat. 4459, 5657 (2022). Grantees must either spend at least 5 percent of the amount they receive each fiscal year to support evidence-based programs that address the crisis care needs of adults and children with serious mental health conditions or spend at least 10 percent by the end of two consecutive fiscal years. 42 U.S.C. § 300x-9(d). For fiscal years 2021 through 2024, we calculated 5 percent of the total $4.4 billion in block grant awards for all awardees to approximate the amount required to be spent across the four years.

[22]These clinics are required to offer crisis stabilization services alongside other behavioral health services. Because the agency had not specified a certain portion or amount of this $2.3 billion that the 573 grant recipients should use to support crisis response services, we did not include this funding amount in our sum of SAMHSA’s total funding for crisis response services. SAMHSA began the program to support clinics preparing for certification in fiscal year 2022.

[23]Behavioral health officials from all five selected states told us they combine, or braid, funding from federal and state sources to support behavioral health crisis services. This braided funding includes SAMHSA grants, Medicaid payments, and state appropriations.

[24]According to the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline and Crisis Services Program Evaluation Plan, the contractor will use existing awardee-reported data in addition to new data collected specifically for the purpose of evaluating the effects of the 988 Lifeline program. For example, the contractor is planning to conduct surveys and case studies to collect new data from crisis services providers on the implementation of the 988 Lifeline. While the contractor intends to gather information from other agency-funded crisis response programs, it does not intend to include a direct evaluation of the implementation or effects of those programs.

According to agency officials, the contractor continued to provide the agency with regular written updates on the evaluation, including quarterly progress reports and annual briefings and reports on the evaluation findings, as of May 2025.

[25]The Community Mental Health Services Block Grant program makes funds available to all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and eight U.S. territories to provide comprehensive community mental health services to adults and children with serious mental health conditions. SAMHSA determines the grant amount for each jurisdiction using a formula specified in statute that considers population needs and cost of services, among other factors. See 42 U.S.C. §§ 300x–-300x-9. In 2021, Congress directed SAMHSA to specify that grantees set aside 5 percent of their grant for evidence-based crisis systems. The set aside was codified in 2022. See Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023. Pub. L. No. 117-328, §1141, 136 Stat. 4459, 5657 (2022). Grantees must either spend at least 5 percent of the amount they receive each fiscal year to support evidence-based programs that address the crisis care needs of adults and children with serious mental health conditions or spend at least 10 percent by the end of two consecutive fiscal years. 42 U.S.C. § 300x-9(d).