PORT SECURITY

FEMA Should Improve Transparency of Grant Decisions

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional requesters

For more information, contact: Heather MacLeod at MacleodH@gao.gov

What GAO Found

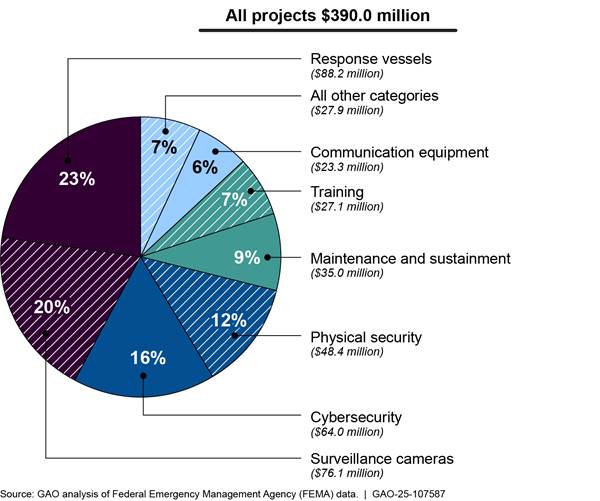

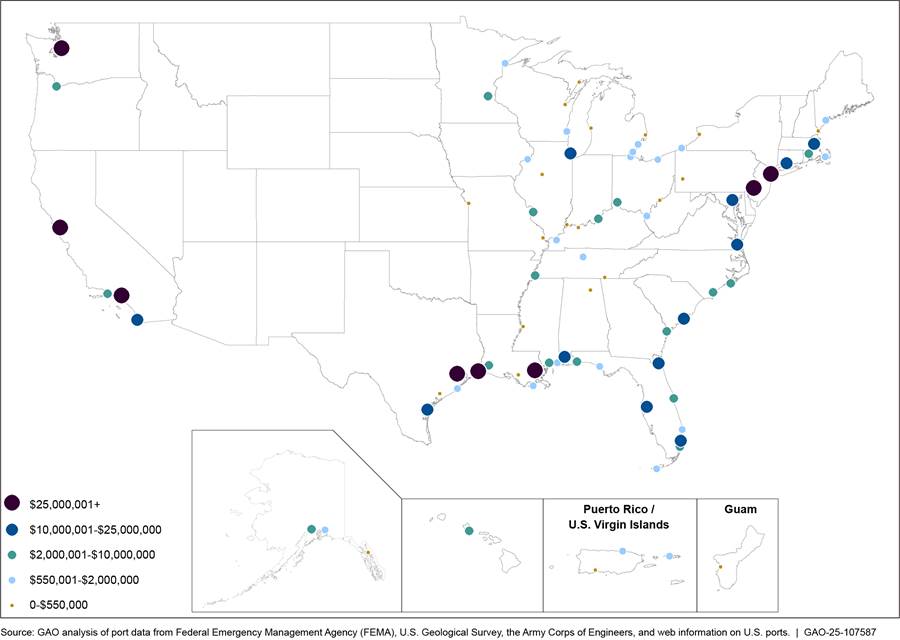

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) administers the Port Security Grant Program (PSGP), in coordination with the U.S. Coast Guard. This risk-based grant program provides funds to public and private sector entities to implement security plans and correct Coast Guard-identified vulnerabilities at U.S. ports. From fiscal year 2018 through 2024, FEMA awarded more than half of the $690 million in grant funds to eight port areas, and 82 port areas across the U.S. received funds. Three project types received 59 percent of grant funds from fiscal year 2021 through 2024: response vessels ($88.2 million), surveillance cameras ($76.1 million), and cybersecurity ($64.0 million). FEMA also awarded funds for other project types including communication equipment, physical security, and training.

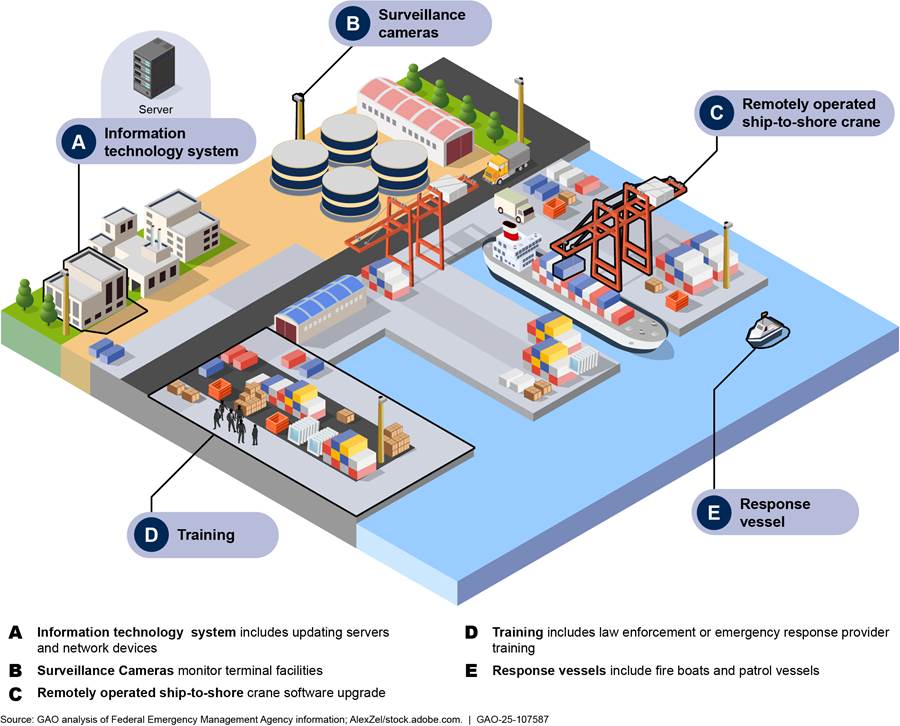

Examples of Projects Funded by the Port Security Grant Program

FEMA and the Coast Guard have processes to evaluate grant applications and make award recommendations. However, the grant announcement does not include a description of all criteria used in these processes, as federal regulations require. Specifically, the fiscal year 2024 grant announcement does not (1) fully or accurately describe the scoring criteria used in the Coast Guard-led portion of the application evaluation process or (2) describe all factors other than merit criteria that FEMA may use in selecting applications for award, such as the five percent of funds set aside for highly effective projects in lower-risk ports. Adding this required information to the grant announcement could improve transparency and fairness for applicants and help them put forward applications better aligned with the evaluation criteria FEMA uses when awarding PSGP funds to enhance port security.

Further, FEMA has not fully assessed the application evaluation process to ensure that its outcomes achieve the program’s multiple goals—funding projects in high-risk port areas; prioritizing projects aligned with national priorities; and funding highly effective projects in lower-risk port areas. For example, projects aligned with a national priority receive a 20 percent score increase, but FEMA has not assessed whether that increase leads to funding more projects aligned with national priorities. Assessing each step of the evaluation process could help FEMA ensure that the process leads to results aligned with FEMA’s program goals.

Why GAO Did This Study

U.S. ports are critical to the economy, and any disruption in maritime operations—such as an attack on a port—can impact the supply chain and the U.S. economy.

GAO was asked to examine FEMA’s management of PSGP. This report examines the types and locations of projects awarded PSGP funds from fiscal year 2018 through 2024 and the extent FEMA followed required and recommended practices for grants, among other objectives. GAO analyzed FEMA and Coast Guard’s grant and scoring data from fiscal years 2018 through 2024, reviewed FEMA and Coast Guard program documents, and interviewed FEMA and Coast Guard officials. GAO visited two ports to gather port stakeholders’ perspectives on PSGP and observe projects that received PSGP funding. GAO also interviewed port stakeholders from nine Coast Guard-led maritime security committees.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making three recommendations to the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to ensure that FEMA, in consultation with the Coast Guard, updates the PSGP grant announcement to include all (1) application review criteria and their relative weights and (2) factors other than merit criteria that FEMA may use in selecting applications for award. GAO also recommends that FEMA assess each step of the application evaluation process to determine if its results are consistent with FEMA’s goals for distributing the program funds. DHS concurred with the recommendations.

Abbreviations

|

DHS |

Department of Homeland Security |

|

FEMA |

Federal Emergency Management Agency |

|

OMB |

Office of Management and Budget |

|

PSGP |

Port Security Grant Program |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

September 17, 2025

Congressional Requesters

U.S. ports are critical to the economy on both a national and local level. The U.S. marine transportation system includes more than 300 ports that account for more than $5.4 trillion in annual U.S. economic activity, supporting more than 30 million jobs. A wide variety of goods—including automobiles, grain, and oil—and millions of cargo containers travel through these ports each day.

As a result, any disruption to maritime operations, such as an attack on a port or incident affecting port infrastructure, can impact the supply chain and the U.S. economy. For example, beginning in 2023 and continuing through 2025, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and other federal agencies have issued warnings about a cybersecurity threat known as Volt Typhoon.[1] The warnings say that a state-sponsored actor affiliated with China poses a threat to U.S. critical infrastructure, which includes ship-to-shore cranes.[2] This has raised concerns about potential threats to the cybersecurity infrastructure of U.S. ports.

The Port Security Grant Program (PSGP) is one of four grant programs that DHS’s Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) administers to strengthen U.S. critical transportation infrastructure against security risks, including potential terrorist attacks.[3] In fiscal year 2025, Congress appropriated $90 million for PSGP to fund public and private sector entities for activities and equipment that protect critical U.S. port infrastructure from threats.[4]

You asked us to review FEMA’s management of PSGP. This report examines the (1) types and locations of projects awarded PSGP funds; (2) PSGP competitive grant process and the extent to which FEMA followed certain required and recommended practices for such grants; and (3) extent to which FEMA awarded PSGP funds to projects expected to mitigate key port vulnerabilities.

To address our first objective and inform the remaining objectives, we collected and analyzed FEMA data on grant applications and awards from fiscal years 2018 through 2024. We selected this time frame because it provided sufficient data for identifying trends over time and through several 3-year grant performance cycles.[5] The fiscal year 2024 award cycle was the most recently completed at the time of our review.

We determined that the FEMA data were sufficiently reliable to describe the number, amount, and port locations of grants awarded each fiscal year from fiscal year 2018 through 2024 and whether projects addressed national priorities or local vulnerabilities. We also determined the data were sufficiently reliable to describe the number and amount of grants awarded by project category from fiscal year 2021 through 2024.

For each of our research objectives, we interviewed port stakeholders to gather their perspectives on PSGP. Port stakeholders we interviewed were members of nine Coast Guard-led Area Maritime Security Committees representing 32 FEMA port areas.[6] We also visited two port areas—New York-New Jersey and Houston-Galveston—to interview PSGP award recipients and observe PSGP-funded projects. We selected these locations based on geographic dispersion, the amount of PSGP grants they received, and the frequency of their PSGP grant awards from fiscal years 2017 through 2023, the most recent data available at the time we made our selections.

To address our second objective, we reviewed FEMA’s fiscal year 2024 PSGP grant announcement and collected documentation and interviewed officials about FEMA and Coast Guard’s application evaluation and award recommendation processes. We selected fiscal year 2024 because it was the most recently completed grant cycle at the time of our review. We compared the description of the application evaluation and award recommendation processes in the fiscal year 2024 grant announcement with information about these processes we collected from FEMA and the Coast Guard. We evaluated FEMA’s grant announcement against selected provisions of the Uniform Administrative Requirements, Cost Principles, and Audit Requirements for Federal Awards.[7] These requirements are in federal regulations and provide a government-wide framework for grants management.

In addition, we evaluated FEMA’s PSGP scoring process by comparing the scoring process FEMA and Coast Guard used to evaluate applications with PSGP statutory requirements and goals described in FEMA documentation, such as the grant announcement, and by FEMA officials. We also reviewed Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government and determined that the monitoring component of internal controls was significant to this objective, along with the underlying principle that management should establish and operate monitoring activities to monitor the internal control system and evaluate the results.[8]

To address our third objective, we analyzed FEMA data on PSGP awards to identify projects awarded funds that aligned and did not align with key port vulnerabilities. We analyzed this data by port area for fiscal years 2018 through 2024. We aggregated information from our interviews with port stakeholders to analyze stakeholder perspectives on the extent to which PSGP funds mitigated port vulnerabilities, including perspectives on the benefits and limitations of PSGP.

For additional details on our scope and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from May 2024 to September 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Port Operations and Security

Many ports are governed by port authorities—these can be an independent entity organized under state law, part of a local or state government, or an interstate authority.[9] Ports generally undertake their activities in coordination with a variety of stakeholders, including federal, state, and local governments and private commercial entities that operate at the port, such as freight carriers, terminal operators, and railroad companies.

The Coast Guard is generally the lead federal agency for port security.[10] Each port is affiliated with a Coast Guard Captain of the Port-led regional Area Maritime Security Committee.[11] One of the functions of the Committees is to advise DHS on how to enhance communication among port stakeholders (including federal, state, and local agencies and private commercial entities) and to improve security—including against terrorism threats—within the port environment.[12]

Through their participation in Area Maritime Security Committees, port stakeholders collaborate with the Coast Guard Captain of the Port to identify at least three potential Transportation Security Incidents that pose a high risk to their port and document them in Area Maritime Security Plans.[13] Examples of such potential security incidents could include an attack on a ferry or cruise ship carrying a large number of people, a cyberattack on a port facility, or a release of toxic chemicals from a vessel.

PSGP Overview

FEMA’s Grant Programs Directorate administers PSGP and other FEMA preparedness grants.[14] The statute establishing PSGP provides for the allocation of PSGP funds based on risk.[15] As such, PSGP is a risk-based grant program that provides funds to state, local, territorial, and private sector entities to implement security plans and correct Coast Guard-identified vulnerabilities. According to FEMA officials, their primary goal for PSGP is to award funds to high-risk ports. FEMA’s additional goals for allocating PSGP funds include ensuring a broad geographic distribution of funds and maintaining consistent funding to ports year after year.

According to the PSGP grant announcement, the purpose of PSGP is to support increased port-wide risk management and protect port infrastructure from acts of terrorism, major disasters, and other emergencies.[16] Eligible applicants include, but are not limited to, port authorities, facility operators, and state, territorial, and local government agencies.[17] Eligible projects include maritime cybersecurity enhancements; physical security enhancements at ports, including ferry and cruise terminals; training for personnel with maritime security responsibilities; exercises specific to maritime security, such as drills and tabletop exercises; and equipment, such as response vessels. Figure 1 shows an example port with eligible PSGP projects.

PSGP has a cost share requirement in which grant recipients are required to match a portion of each project’s cost. According to the grant announcement, public sector or nonprofit grant recipients must generally contribute 25 percent of the total approved project costs and private sector grant recipients must generally contribute 50 percent of the approved project costs.[18] The performance period for PSGP—from the time a project is awarded funds to the time it must be fully implemented—is 3 years.

Evaluation Criteria and Award Process

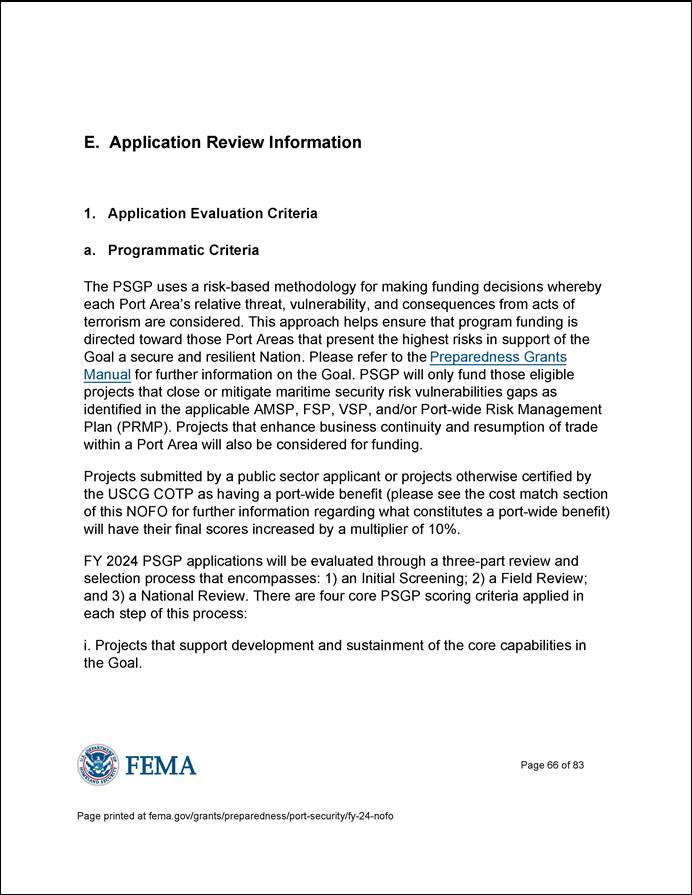

Office of Management and Budget (OMB) regulations address how federal agencies in the executive branch are to administer discretionary grant programs, including PSGP.[19] Specifically, the OMB regulations outline what information to include in the grant announcement, how to evaluate applications, and how to make the application process transparent to maximize fairness of the process.

As required by these regulations and to facilitate the evaluation and award of PSGP grants, FEMA makes a grant announcement regarding the availability of funds, the program’s funding priorities, and the criteria by which FEMA will evaluate applications.

FEMA and the Coast Guard work together to evaluate PSGP applications and make award recommendations through a competitive process.[20] DHS’s Transportation Security Administration and the Department of Transportation’s Maritime Administration also participate in the application evaluation process.

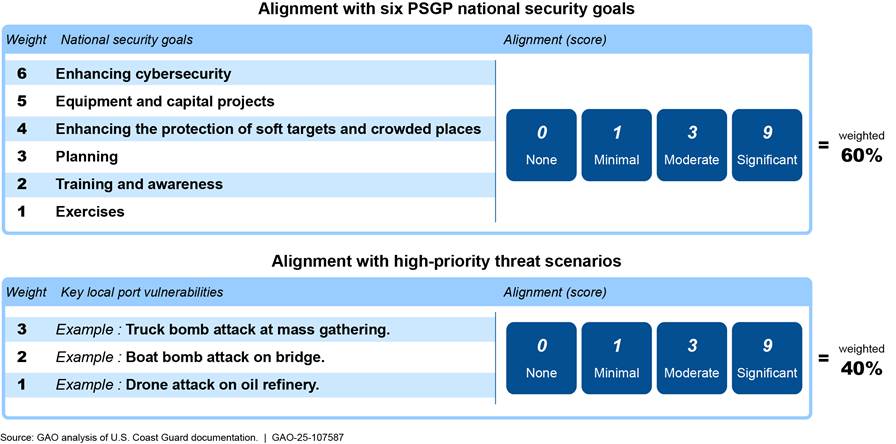

The PSGP evaluation process includes examining applications’ alignment with:

· DHS’s national security priorities for PSGP. According to FEMA and Coast Guard officials, DHS determines the national priority areas each year through a process in which they solicit input from various stakeholders within the agency.[21] FEMA officials told us they determine which DHS national priorities are applicable to PSGP. They said the national priority areas are responsive to the needs of Congress and the DHS Secretary and have evolved over time. In fiscal year 2024, the PSGP national security priorities were (1) enhancing cybersecurity and (2) mitigating threats to soft targets and crowded places.

· National security enduring needs. According to FEMA officials, the four national security enduring needs align with PSGP’s authorizing legislation and have remained the same over time. The enduring needs are equipment and capital projects, planning, training and awareness, and exercises.[22]

· Key port vulnerabilities. Each port’s Area Maritime Security Plan is to identify at least three potential Transportation Security Incidents that port stakeholders believe present the highest-priority threats to the port. For the purposes of this report, we refer to projects mitigating the risks associated with these high-priority threats as those that address key port vulnerabilities.

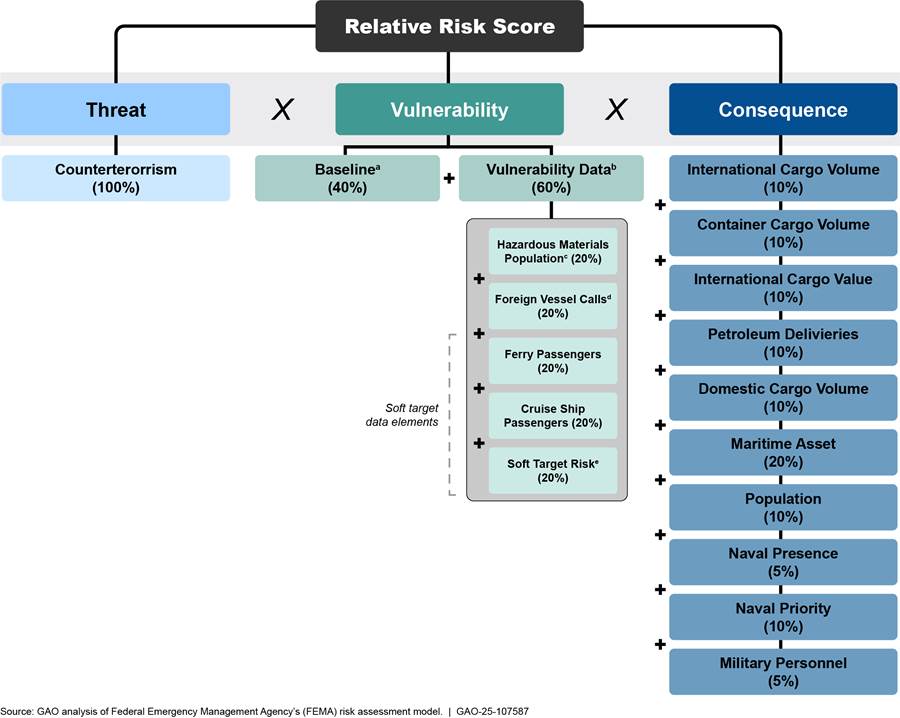

· Terrorism risk. PSGP funding recommendations are based partially on the risk of terrorism to a port. FEMA combines individual ports into larger regions called FEMA port areas based on its assessment that they share geographic proximity, waterways, and risk. In fiscal year 2024, there were 131 FEMA port areas. FEMA calculates a risk score for each port area based on its assessment of the level of risk terrorism poses to that port area.[23]

The Majority of PSGP Funds Went to Vessels, Surveillance, and Cybersecurity Projects Across the U.S.

About Sixty Percent of PSGP Funds Awarded by FEMA Went to Response Vessels, Surveillance Cameras, and Cybersecurity

From fiscal years 2021 through 2024, FEMA awarded 59 percent of PSGP funds ($228.3 of $390.0 million) to response vessels, surveillance cameras, and cybersecurity projects.[24] During this period, FEMA awarded funds to 824 projects in these three categories. The total funds awarded in each of these three project categories ranged from $64.0 million (cybersecurity) to $88.2 million (response vessels) (see figure 2).

Notes: All other categories include exercises, personnel costs, and unmanned aircraft systems (drones), among other categories. Coast Guard began assigning Port Security Grant Program applications to specific project categories in 2021. The Department of Homeland Security requires that each application be assigned to one of the following categories: planning, organizing, equipping, training, or exercising. According to officials, Coast Guard implemented the more specific project categories because DHS’s broader project categories did not meet Coast Guard’s data analysis needs. Our analysis includes the four most recent years of awards and their associated Coast Guard-assigned project categories.

FEMA awarded the remaining 41 percent of PSGP funds ($161.7 million) to 714 projects in other categories, including communication equipment, physical security, and training.

From fiscal years 2021 through 2024, FEMA awarded PSGP funds to the following:

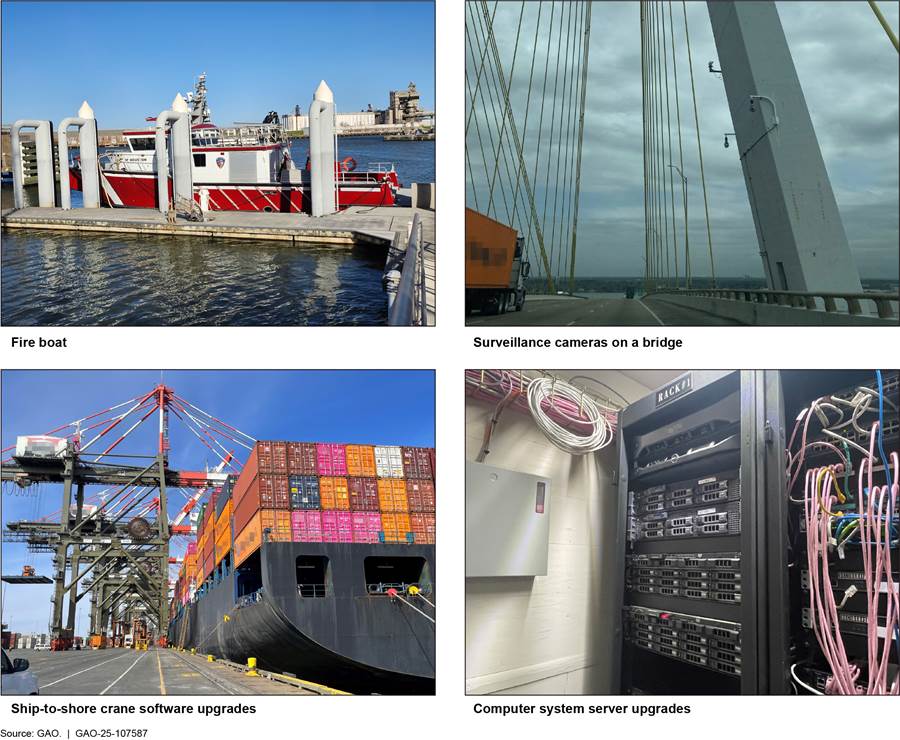

· Response vessels. FEMA awarded $88.2 million to 306 projects to acquire or maintain response vessels. According to FEMA data, response vessel projects funded by PSGP funds included purchasing a boat to patrol waterways and updating boat equipment, such as motors and electronics, to extend a vessel’s service life. Port stakeholders we interviewed in four locations told us that although response vessels purchased with PSGP funds are owned by one agency, they benefitted other agencies and entities, including those that did not have sufficient assets to address incidents on their waterway. See figure 3 for an example of a response vessel (fire boat) purchased with PSGP funds.

· Surveillance cameras. FEMA awarded $76.1 million to 321 projects involving surveillance cameras or remote viewing. The remote viewing projects included purchasing cameras and upgrading server infrastructure to enhance surveillance capability at port facilities, according to FEMA data. Port stakeholders in four locations told us surveillance cameras purchased with PSGP funds allow them to quickly respond to incidents that they might not have been aware of without the cameras. See figure 3 for an example of cameras on a bridge surveilling a port waterway that were purchased with PSGP funds.

· Cybersecurity. FEMA awarded $64.0 million to 197 cybersecurity projects. Enhancing cybersecurity has been a DHS national security priority for PSGP every year from 2021 through 2024.[25] Further, beginning in 2023 and continuing through 2025, DHS and other federal agencies issued warnings about cybersecurity threats to U.S. critical infrastructure, including ship-to-shore cranes in U.S. ports.[26] FEMA awarded funds to 11 PSGP projects focused on addressing cybersecurity concerns related to remotely operated ship-to-shore cranes in fiscal years 2023 and 2024.[27] See figure 3 for an example of a ship-to-shore crane with upgraded software purchased with PSGP funds.

More than 80 Port Areas Received PSGP Funds; Eight Port Areas Received Over Half of All Funding

From fiscal years 2018 through 2024, FEMA awarded $690 million in PSGP funds to 82 port areas across the U.S., with eight port areas receiving over half of all funding.[28] Demand for PSGP awards generally exceeded available funds. For example, in fiscal year 2024, FEMA funded 326 projects with the $90 million in appropriated PSGP funds but could not fund an additional 297 projects that FEMA and the Coast Guard deemed qualified.[29]

Figure 4 shows the port areas across the U.S. that received PSGP funds from fiscal year 2018 through 2024.

Notes: FEMA combines individual ports into larger regions called FEMA port areas based on FEMA’s assessment that ports in a port area share geographic proximity, waterways, and risk. According to FEMA documentation, there were 131 FEMA port areas across the U.S. as of 2024. Of the 131 FEMA port areas, about 50 FEMA port areas did not receive a PSGP award from fiscal years 2018 through 2024.

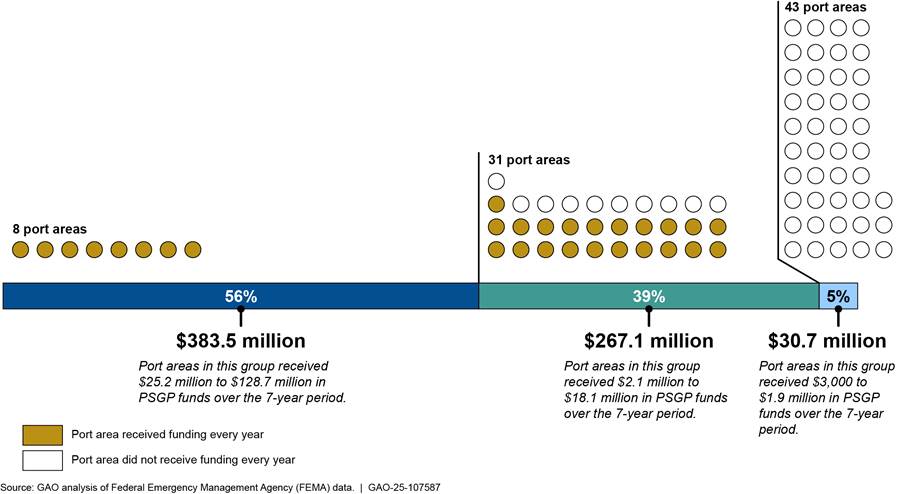

Although many port areas received some PSGP funding, PSGP awards were concentrated in certain port areas. Figure 5 shows that eight port areas received more than half of all PSGP funding during this 7-year period.

Figure 5: Distribution of Port Security Grant Program (PSGP) Funds to FEMA Port Areas, Fiscal Years 2018 through 2024

Note: FEMA combines individual ports into larger regions called FEMA port areas based on FEMA’s assessment that ports in the designated area share geographic proximity, waterways, and risk. FEMA and Coast Guard assign projects that will be implemented within two miles of the boundary of a FEMA port area to that port area. From fiscal year 2018 through 2024, FEMA awarded $8.7 million to projects located beyond the two-mile boundary of any port area.

The port areas that received the most PSGP funds were New York-New Jersey ($128.7 million), Los Angeles-Long Beach ($60.7 million), and Houston-Galveston ($47.2 million). See appendix II for more information about PSGP funding by FEMA port area, including the total funds each port area received in fiscal years 2018 through 2024.

FEMA Followed Some Required Grant Practices, but Its Application Evaluation Process Lacks Transparency

FEMA has a process to administer PSGP grants, as federal regulations and statute require. The process involves announcing the funding opportunity, evaluating applications, and making award recommendations. However, the PSGP grant announcement does not include all required information. Specifically, it does not include a description of all criteria used to evaluate applications or all factors FEMA uses to make award recommendations. In addition, FEMA has not fully assessed the PSGP application evaluation process to ensure that its outcomes align with FEMA’s goals.

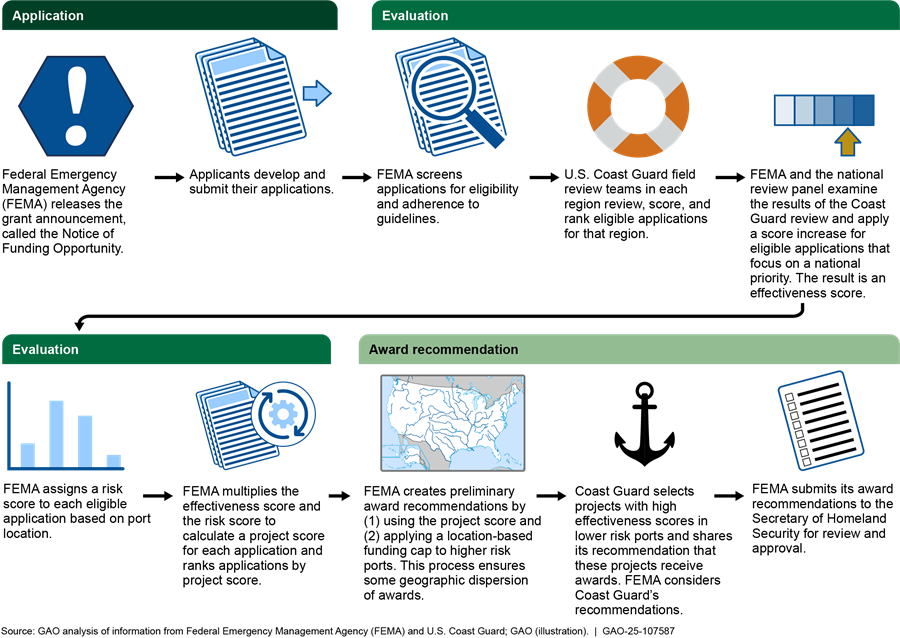

FEMA and Coast Guard Have an Application, Evaluation, and Award Recommendation Process

FEMA has a process to administer PSGP grants, as federal regulations and statute require. The process involves announcing the funding opportunity, evaluating applications, and making award recommendations. FEMA and Coast Guard play key roles in the application evaluation and award recommendation process, as shown in figure 6.

Application

After enactment of the annual DHS appropriations act, FEMA issues a grant announcement regarding the availability of funds, the program’s funding priorities, and the corresponding criteria by which FEMA will evaluate applications. In response to the grant announcement, public and private sector entities submit applications.

Evaluation

Eligibility. Following the application submission deadline, FEMA officials screen submitted applications for eligibility and adherence to the grant guidelines, as described in the grant announcement. For example, eligible applicants include port authorities and facility operators (e.g. terminal operators, ferry systems). FEMA’s screening evaluates whether each application was submitted by an eligible applicant. Eligible applications are advanced to the Coast Guard for further evaluation.

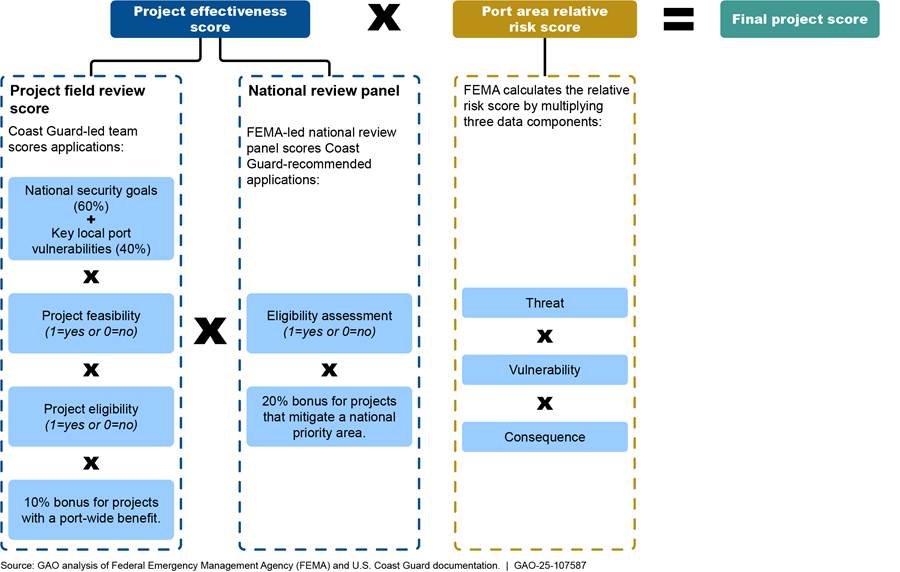

Field review. The Coast Guard-led field review team evaluates and scores applications by evaluating a project’s feasibility, eligibility, and effectiveness. If the field review team finds a project is not feasible or not eligible for PSGP, the project is not recommended for funding. In general, field review teams are aligned with Coast Guard’s Area Maritime Security Committees and led by a field-based Coast Guard staff member. The composition of field review teams varies by location, but teams generally include Gateway Directors from the Maritime Administration and some other port stakeholders. All field review teams use Coast Guard guidance and the same scoring system to ensure that the review and scoring process is uniform across locations.

The field review team evaluates a project’s effectiveness based on how well it addresses FEMA’s PSGP national security goals (including national priorities and enduring needs) and key local port vulnerabilities.[30] The field review score is based on the weighted average of the project’s national security goal score (weighted 60 percent) and key local port vulnerabilities score (weighted 40 percent), as shown in figure 7.

Projects that offer a port-wide benefit receive an additional 10 percent score increase.[31] According to Coast Guard officials, each field review team determines who participates in the application review and scoring process for that location. For example, in some locations a committee of port stakeholders convenes to review and score applications. In other locations, the Coast Guard Port Security Specialist leads the scoring process with limited participation by other stakeholders.

The Coast Guard Port Security Specialist ranks projects within each FEMA port area based on their scores. Finally, the Coast Guard Captain of the Port reviews the project rankings and may suggest changes to ensure that the rankings align with Captain of the Port priorities. Coast Guard aggregates the information from each field review team and sends it to FEMA.

National review panel. The FEMA-led national review panel examines the results of Coast Guard’s field review and confirms that each recommended project is eligible for PSGP. According to FEMA officials, FEMA instructs the national review panelists to concur with Coast Guard’s field review recommendations unless they find that Coast Guard recommended a project that is not eligible for PSGP.

The national review panel includes representatives from FEMA, DHS’s Transportation Security Administration, and the Department of Transportation’s Maritime Administration. Officials who participate in the national review told us they act as generalists and that each member of the national review panel has a similar role. In addition, the national review panel assesses whether each project addresses one or more of DHS’s PSGP national priorities.[32] Projects that address a national priority receive a 20 percent score increase to their field review score. A project’s effectiveness score, which may range from 0 to 100, is the field review score combined with any score increase based on national priority alignment.

Risk score. FEMA uses a risk model to calculate a relative risk of terrorism score for each FEMA port area and then assigns that risk score to all applications in the port area. Figure 8 shows how FEMA uses a variety of inputs to calculate a threat, vulnerability, and consequence score for each port area. FEMA then multiplies the threat, vulnerability, and consequence scores together to generate a scaled relative risk score for each port area. Port area relative risk scores may range from 1 to 100.

aAccording to FEMA guidance, all port areas have a baseline level of vulnerability. Therefore, the model includes a vulnerability baseline of 40 percent for all port areas.

bVulnerability data are intended to capture operational attributes and other features that may render a port open to exploitation or susceptible to a given hazard.

cHazardous materials population captures the surrounding population’s vulnerability to potential attacks that may cause hazardous materials to release into the surrounding environment.

dForeign vessel calls data captures the number of foreign-flagged vessels that enter a port.

eSoft target risk data is derived from the Coast Guard’s Maritime Security Risk Analysis Model (MSRAM) and provides a count of maritime assets on which people traveling through crowded areas of a port may be vulnerable to an attack.

Project score. FEMA multiplies the effectiveness score by the risk score to calculate a final project score for each project recommended for funding. FEMA uses the project score to rank all applications recommended for funding.

Award Recommendation

Preliminary award recommendations. FEMA uses the ranked list of project scores to select those it recommends for a PSGP award. When making these selections, FEMA considers 1) the project score and 2) location-based funding caps.

FEMA calculates a location-based funding cap for the highest-risk port areas. This limits awards in those areas to a certain amount of the overall pool of PSGP funds. Table 1 shows examples of port areas where the location-based funding cap limited PSGP awards in fiscal year 2024.

Table 1: Examples of Port Areas Where Location-Based Funding Caps Limited Port Security Grant Program Awards in Fiscal Year 2024

|

FEMA port area |

Location-based funding cap in fiscal year 2024 |

|

New York-New Jersey |

$16,506,106 |

|

Los Angeles-Long Beach |

$8,623,172 |

|

Houston-Galveston |

$8,591,891 |

|

Puget Sound |

$4,069,986 |

|

Delaware Bay |

$3,737,881 |

|

Sabine-Neches River |

$2,620,892 |

Source: GAO analysis of Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) data. | GAO‑25‑107587

According to FEMA, the purpose of the cap is to ensure that the highest-risk port areas receive the most PSGP funding while also allowing funds to remain available for effective projects in lower-risk port areas. When the cap is met in a given port area, FEMA stops recommending projects in that port area and selects the next highest-scoring project. FEMA continues this process until it has allocated all available funds.

One effect of the cap is that projects with high effectiveness scores in lower-risk port areas may be funded ahead of projects with lower relative effectiveness scores in high-risk port areas. For example, in fiscal year 2024, a project required an effectiveness score of 26 or higher to receive a PSGP award in Los Angeles-Long Beach due to the funding cap.[33] Conversely, projects with effectiveness scores as low as seven received PSGP awards in New Orleans and San Francisco, port areas where the number of projects recommended for funding did not exceed the funding cap.[34]

Selection of highly effective projects in lower-risk port areas. According to Coast Guard and FEMA officials and FEMA data, beginning in fiscal year 2021 and in response to Coast Guard concerns that projects in lower-risk port areas rarely received PSGP awards, FEMA created a set-aside of five percent of PSGP funds for highly effective projects in lower-risk port areas. In fiscal year 2024, this set-aside was $4.5 million. Coast Guard and FEMA officials told us that Coast Guard recommends these projects to FEMA for consideration. Coast Guard prioritizes (1) distributing the set-aside funds as geographically broadly as possible and (2) selecting projects that are as impactful as possible.

Secretary’s approval. FEMA submits its award recommendations to the DHS Secretary for review and final approval.[35] FEMA officials told us that the DHS Secretary generally concurs with FEMA’s recommendations for PSGP awards.

PSGP Grant Announcement Does Not Include Required Information About the Application Evaluation and Award Recommendation Process

The PSGP grant announcement does not include a description of all criteria used to evaluate applications and make award recommendations, as federal regulations require. As a result, potential applicants may not understand how to put forward a project application that best aligns with the evaluation criteria or what information FEMA considers in making award recommendations.

Federal regulations require agencies to include all criteria used to influence final award decisions in their grant announcements to make the application process transparent and maximize the fairness of the process. Specifically, OMB’s Uniform Administrative Requirements, Cost Principles, and Audit Requirements for Federal Awards states that public grant announcements must include, among other things: (1) the merit-based criteria that will be used to evaluate grant applications, (2) the relative weights that will be applied to those evaluation criteria, and (3) any program, policy or other factors or elements, other than merit criteria, that the selecting official may use in selecting applications for federal award (e.g., geographical dispersion, program balance, or diversity).[36] The intent of these requirements is to make the application process transparent and maximize fairness.[37]

Application Evaluation Process

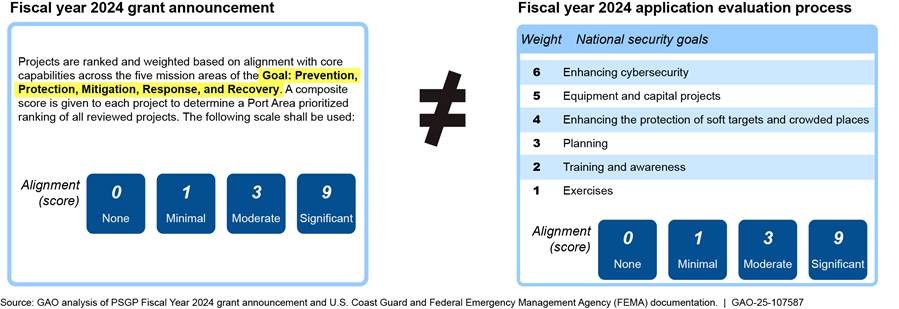

The PSGP grant announcement does not include all merit-based criteria used to evaluate grant applications and does not include the relative weights of all criteria, as required by OMB regulations.[38] Specifically, the Application Evaluation Criteria section in the fiscal year 2024 grant announcement does not fully or accurately describe the scoring criteria or relative weights the Coast Guard-led field review uses to evaluate applications.[39] For example, the section of the grant announcement that describes the Coast Guard field review does not accurately describe the evaluation of a project’s alignment with PSGP national security goals and does not describe the weights assigned to those goals. Figure 9 shows the difference between the section of the grant announcement describing Coast Guard’s field review and the criteria field reviewers use to evaluate projects.

Figure 9: Comparison of Part of the Port Security Grant Program (PSGP) Grant Announcement and Related Part of the Application Evaluation Process

Note: This figure shows the grant announcement description and the criteria used for one step of the PSGP application evaluation process. This step is the Coast Guard’s field review evaluation of the extent to which a PSGP application aligns with FEMA’s national security goals for the program.

Projects offering a port-wide benefit receive a 10 percent increase to their field review score. The field review is one of the early steps in the application evaluation process. However, the grant announcement says that a project with a port-wide benefit receives a 10 percent increase to their “final score.” The grant announcement does not define or explain what constitutes a project’s final score.

Further, the PSGP grant announcement does not clearly describe how the various application evaluation criteria are weighted and summed to collectively lead to an overall project score. Port stakeholders from two of nine Area Maritime Security Committees told us they consult with Coast Guard field review staff to better understand the application evaluation process because the description of the process in the grant announcement is not clear. Figure 10 shows the criteria and weights used in the application evaluation process.[40]

Specifically, the PSGP grant announcement does not state that a project’s field review score is based on the weighted average of the project’s national security goal score (60 percent) and key local port vulnerabilities score (40 percent), with a 10 percent increase for any project with a port-wide benefit. Further, the PSGP grant announcement does not state that a relative risk score based on port location—and therefore out of an applicant’s control—is multiplied by a project’s effectiveness score to calculate the final project score.[41] See appendix III for an excerpt of the relevant section of the PSGP grant announcement.[42]

FEMA officials told us that they were not aware of the requirement that the grant announcement include all application evaluation criteria and their relative weights.[43] They further said that they were willing to include this information in future grant announcements because adding it would improve transparency for applicants and port stakeholders. By adding the application evaluation criteria and their relative weights to the PSGP grant announcement, as required by OMB regulations, FEMA would give applicants a better understanding of the evaluation process and better position them to make an informed decision to apply for award funds.

Award Recommendation Process

The section of the PSGP grant announcement that describes the award recommendation process does not include all factors FEMA officials use to make award recommendations, as required by OMB regulations.[44] Specifically, the grant announcement does not describe the informal set-aside of five percent of appropriated funds for highly effective projects in lower-risk port areas.[45] Further, the grant announcement states that FEMA may use a location-based funding cap to make award recommendations, but it does not say that FEMA may develop multiple award scenarios using different funding caps and then select the one that best aligns with its program goals, which FEMA officials told us was part of the process.

We found that the five percent set-aside selection factor (1) increased the number of port areas that received PSGP awards and (2) recommended awards in some port areas that would otherwise have been mathematically precluded from receiving an award recommendation due to their low port area risk score.[46] Port stakeholders in six locations told us that the process by which FEMA used the field review scores and other factors to make award recommendations was not clear or transparent to them. In four of these locations, port stakeholders said they were sometimes surprised by PSGP award decisions because they did not always align with the projects ranked highly after the field review.

In addition, as previously discussed, the funding cap scenario FEMA selected in fiscal year 2024 limited PSGP awards in some ports. According to the grant announcement, the purpose of the funding cap is to ensure that minimally effective projects in the highest-risk port areas are not funded ahead of highly effective projects in lower-risk port areas. However, the scenario FEMA selected for the funding cap in fiscal year 2024 did not preclude funding some projects with relatively low effectiveness scores in higher-risk port areas. Specifically, projects with effectiveness scores as low as seven received PSGP awards in 2024 in New Orleans and San Francisco, both of which are higher-risk ports.[47]

FEMA officials agreed that the grant announcement does not describe all factors they use to make award recommendations. They told us that one reason the grant announcement does not fully describe all factors they use to make award recommendations—including the five percent set-aside for highly effective projects in lower-risk ports and the fact that FEMA considers multiple funding cap scenarios—is because the DHS Secretary has discretion to make all final funding determinations. However, OMB regulations require that agencies include in their grant announcement all factors that may be used in selecting applications for award.[48] Officials told us that they could more fully describe the factors they use to make award recommendations in the grant announcement.

FEMA officials also told us they are working to adhere to a 2024 OMB directive to write grant announcements in concise and plain language and need to balance adding information on evaluation criteria and award recommendation factors with adhering to other OMB regulatory requirements.[49] However, including all application evaluation criteria and factors FEMA uses to make award recommendations in the PSGP grant announcement, as required by OMB regulations, would make the process more transparent and help maximize fairness to applicants. Specifically, clearer information in the grant announcement could help PSGP applicants better align their projects with the evaluation criteria FEMA uses when awarding PSGP funds to enhance port security.

FEMA Has Not Fully Assessed the PSGP Application Evaluation Process

FEMA has not fully assessed the PSGP application evaluation process to ensure that its outcomes align with FEMA’s goals of funding projects in high-risk port areas while also prioritizing projects aligned with national priorities and those that are highly effective and located in lower-risk port areas.[50]

National Priorities

As previously discussed in this report, projects receive a 20 percent score increase if the primary purpose is to address one of DHS’s PSGP national priorities. According to FEMA officials, FEMA first implemented a 10 percent score increase for projects that addressed a national priority in 2019. In 2020, FEMA changed the increase to 20 percent. FEMA officials told us they made this change because it further increased the effectiveness score of projects addressing a national priority and could improve their chances of being funded. However, from 2020 through May 2025, FEMA did not assess whether the score increase for projects that addressed a national priority increased awarded funding to those projects.

FEMA officials told us they examined their data in response to our questions and believe the score increase has been effective because it emphasized the importance of national priorities as a goal of PSGP and has led to a general upward trend of funding national priority projects. However, it is unclear whether the 20 percent score increase prioritizes funding to national priorities, as intended. The 2020 grant announcement said that FEMA’s goal that year was to allocate 50 percent of PSGP funds to projects that addressed cybersecurity, the only national priority that year. FEMA data indicate that 12 percent of PSGP funds—well below the 50 percent goal—went to projects with a primary purpose of cybersecurity in 2020. Further, from fiscal years 2021 through 2024, the percent of PSGP funds allocated each year to projects that received a national priority score bonus has ranged widely—from 16 to 42 percent, or $16.4 to $41.7 million.[51]

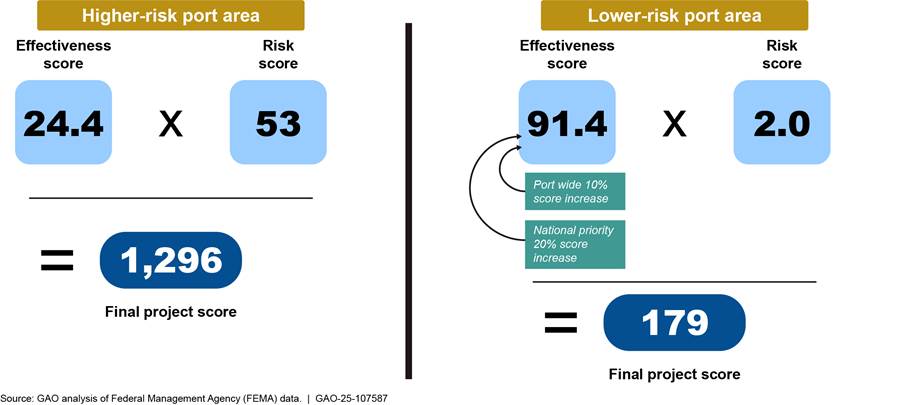

High-Risk Port Areas

To achieve the goal of funding projects in high-risk port areas, FEMA calculates a final project score for each PSGP application by multiplying the project’s effectiveness score by the port location risk score. Both scores are equally weighted in this calculation. Port area risk scores are not evenly distributed; there are many lower-risk port areas and few higher-risk port areas. As a result, projects with high effectiveness scores in lower-risk port areas may have a final project score that is much lower than projects with low effectiveness scores in higher-risk port areas (see figure 11).

Figure 11: Examples of Port Security Grant Program (PSGP) Final Project Scores for Higher- and Lower-Risk Port Areas

Multiplying the risk and effectiveness scores affects which projects FEMA recommends for PSGP awards. Specifically, in fiscal year 2024, projects in 79 port areas with relative risk scores of 1.26 or lower could not mathematically achieve a high enough final project score to receive a PSGP award.[52]

FEMA officials told us that the decision to multiply risk and effectiveness to calculate the project scores was made in the early years of PSGP and vetted through Congress at that time.[53] This decision aligns with PSGP’s goal of prioritizing funds to high-risk port areas. According to FEMA documentation, FEMA considered alternative approaches to this and other calculations in the PSGP scoring process in 2021. Specifically, they considered reducing the weight of the risk score to increase the influence of the effectiveness score on the final project score. They also considered implementing a minimum threshold for the effectiveness score to ensure that funding would be directed to projects with effectiveness scores above that threshold.[54] However, FEMA did not make any changes to the PSGP calculations as a result of these assessments.[55]

Dispersion of Awards to Lower-Risk Port Areas

After FEMA scores and ranks all applications, it implements a location-based funding cap and works with Coast Guard to select highly effective projects in lower-risk port areas. According to FEMA officials, FEMA takes these steps to ensure that its award recommendations are aligned with the goal of ensuring that some PSGP funds go to projects in lower-risk port areas to fund highly effective projects. This is because using project scores alone does not meet that goal. FEMA data show that if FEMA made award recommendations based on final project scores only, the awards would be more concentrated in high-risk port areas and would not be available for highly effective projects in lower-risk port areas.

According to federal internal control standards, management should monitor the internal control system to ensure that its activities consistently meet its goals and evaluate the results of this monitoring.[56] The ongoing monitoring of the internal control system allows management to respond to changes to the system and to ensure that the system is working as intended. The additional steps FEMA takes to select projects it recommends for awards after the application evaluation process is an indication that the evaluation process could be improved so its results better align with FEMA’s goals for PSGP.

FEMA officials told us that they have assessed some parts of the PSGP application evaluation process, but that they have not revisited these assessments since 2021. Further, these prior assessments did not fully address the gaps between the results of the application evaluation process and FEMA’s goals for PSGP. Assessing each step of the PSGP evaluation process—including the selection of weights and calculations used in the process and their effect on project scores—and making adjustments, as appropriate, could help FEMA ensure that the outcome of the PSGP application evaluation process is aligned with FEMA’s goals for the program, consistent with the authorizing statute.

Almost All PSGP Awards Went to Projects Mitigating Key Port Vulnerabilities

FEMA Awarded More than 90 Percent of PSGP Funds to Projects Expected to Mitigate a Key Local Port Vulnerability

Ninety-one percent of PSGP funds awarded from fiscal years 2018 through 2024 ($629.3 of $690.0 million) went to projects that, according to their application project scores, were expected to moderately or significantly mitigate a key local port vulnerability.[57] Table 2 shows the eight port areas that, collectively, received 56 percent of PSGP funds from fiscal years 2018 through 2024 and the percent of those funds in each port awarded to projects that addressed one or more of the highest-priority threat scenarios by mitigating a key local port vulnerability.

Table 2: Port Security Grant Program (PSGP) Awards Received and Percent of Funds Expected to Mitigate a Key Local Vulnerability, by Port Area, Fiscal Years 2018 through 2024

|

FEMA port area |

PSGP awards received |

Percent of PSGP award funds expected to mitigate a key local vulnerability |

|

New York-New Jersey |

$ 128,675,849 |

>99% |

|

Los Angeles-Long Beach |

$ 60,693,586 |

97% |

|

Houston-Galveston |

$ 47,237,998 |

83% |

|

New Orleans |

$ 33,350,500 |

61% |

|

San Francisco Bay |

$ 33,230,783 |

91% |

|

Delaware Bay |

$ 28,204,820 |

89% |

|

Puget Sound |

$ 26,902,284 |

81% |

|

Sabine-Neches River |

$ 25,187,371 |

94% |

Source: GAO analysis of Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) data. | GAO‑25‑107587

Note: This table includes the eight ports that collectively received 56 percent of PSGP awards ($383.5 of $690.0 million awarded) from fiscal years 2018 through 2024. The remaining $306.5 million were awarded across 74 ports and to projects outside FEMA port areas. Ninety-two percent of those remaining funds targeted one or more of the three highest-priority threats to the port.

In the two port areas that received the most PSGP funding from 2018 through 2024 (New York-New Jersey and Los Angeles-Long Beach), FEMA awarded 97 and more than 99 percent of PSGP funds to projects that reviewers scored as moderately or significantly likely to mitigate one or more key local vulnerabilities.[58] In the six other port areas that received more than $25 million in PSGP funding from 2018 through 2024, FEMA awarded the majority of PSGP funds (61 to 94 percent) to projects that targeted the highest priority threats.

Projects awarded funds that reviewers scored as not likely to mitigate a key local vulnerability had other characteristics that made them competitive for PSGP funding. For example, a project in a high-risk port area aligned with one or more national security goals could receive a high total project score, even if it did not mitigate a key local vulnerability. Additionally, the Captain of the Port could prioritize a project for funding by ranking it highly even if it didn’t target one of the three highest-priority threat scenarios for the port. According to Coast Guard documentation and officials, all projects Coast Guard recommends for PSGP funding mitigate Coast Guard-identified vulnerabilities, as required by statute.[59] This is because Captains of the Port are to ensure that all projects for which they recommend funding are aligned with the local Area Maritime Security Plan or other security plan, as appropriate.

FEMA is in the process of implementing a tool—the Port Risk Assessment Methodology—to measure risk reduction attributable to PSGP investments.[60] The tool uses input from port stakeholders to develop a baseline measure of risk for each port area and provides a visual representation of a port’s assets and risks. FEMA anticipates that port stakeholders will update the tool each year and, in doing so, document any changes in port facilities, infrastructure, threats, or relative risks. Over time, FEMA officials expect the data this tool captures will have multiple purposes. It will demonstrate how PSGP helps improve or maintain capabilities within each port, provide port stakeholders with information about how to prioritize their PSGP funding requests, and may improve port incident prevention and response plans.

According to Stakeholders, PSGP Has Improved Port Security

Port stakeholders we spoke with from nine Coast Guard-led Area Maritime Security Committees across the U.S. told us that PSGP funds have enhanced port security because they encouraged participation in Area Maritime Security Committees, mitigated risks at their ports, and supplemented available local resources.[61] Stakeholders also shared their perspectives on the limitations of PSGP, such as the effect that decreasing appropriations and increasing project costs has had on their ability to implement high-cost, high-impact projects.

PSGP Benefits

Port stakeholders from seven of nine Area Maritime Security Committees we spoke with and Coast Guard headquarters officials told us that PSGP is important because it is a tool for stakeholder engagement, especially at small ports. Specifically, stakeholders and officials told us that the potential access to PSGP funds encouraged participation in Area Maritime Security Committees. Officials emphasized that such participation is important because the Coast Guard’s layered approach to maritime security relies on stakeholders who voluntarily participate in Area Maritime Security Committee activities.

Port stakeholders from all nine Area Maritime Security Committees we spoke with told us that PSGP investments mitigated risks at their ports. While stakeholders generally said that it is difficult to quantify the extent to which a PSGP investment improves security, they provided specific examples of how PSGP investments have improved security and mitigated risk. For example, stakeholders from four ports told us that, after the implementation of certain PSGP projects, Coast Guard’s field-based risk analysis tool showed a reduction in risk for the port.[62] Stakeholders in other ports said that they noticed how PSGP investments mitigated risk when conducting exercises related to security risks at their ports. These risk mitigations included improved law enforcement response times and improved visibility into portions of a port waterway using remote cameras. In addition, a stakeholder from one port told us that he documented a decrease in the number of port intrusion attempts after implementing a physical barrier using PSGP funds.

Finally, stakeholders said that PSGP investments positioned them to respond more quickly—and with the right resources—to incidents in their waterways by, for example, supplementing available local resources for port security. In one location, stakeholders said that PSGP-funded cameras and response vessels helped them apprehend a person who had dropped multiple pipe bombs from a bridge onto vessels in their waterway.[63] In another location, port stakeholders said that PSGP-funded cameras on ferry boats helped them track the movements of persons of interest to law enforcement in multiple criminal incidents. In two locations, stakeholders described PSGP as having an outsize effect on security because it allowed them to develop capabilities that improved communication and collaboration across multiple first responder entities and multiple ports. These stakeholders described PSGP as providing the initial investment that allowed them to develop new capabilities—such as a unified radio communication system—that ultimately benefited an entire port or region.

PSGP Limitations

Port stakeholders also shared perspectives about some limitations of PSGP. Stakeholders from four of nine Area Maritime Security Committees we spoke with told us that the costs of projects, especially those such as equipment and vessels, have increased while available PSGP funds have remained the same or decreased. This means that it is difficult to secure PSGP funds for high-impact, high-cost projects, such as fire boats or other response vessels.[64] For example, port stakeholders in one location told us that, after about 15 years of service in a saltwater ship channel, a PSGP-funded fire boat is nearing obsolescence. They expressed concern that replacing the vessel with another funded by PSGP would be nearly impossible because equipment costs have increased and available PSGP funds have decreased.

Stakeholders also told us that equipment purchased using PSGP funds—including software, cameras, servers, and other equipment—eventually reaches the end of its useful life and that it can be difficult to secure PSGP funds to replace that equipment. According to FEMA data, from fiscal years 2021 through 2024, about nine percent of PSGP funds were awarded to maintain or sustain existing capabilities. Port stakeholders in one location described keeping up with evolving technology as one challenge associated with sustaining PSGP projects. They said it can be more cost effective to replace equipment—such as a server or software package—every few years rather than pay for a contractor or other service provider to keep an older service or system operational.

Finally, stakeholders said that the cost of port security enhancements they would like to make exceeds available PSGP funds. For example, stakeholders in one location said that they can generally get their top three projects funded each year, but the bottom half of applicants know they do not have a good chance to receive funding. In another location, stakeholders said they put forward projects they need that align with PSGP priorities, but that some years, the port area does not receive any awards. In a third location, stakeholders emphasized that it is expensive—but vital—to protect ports because of their economic impact. They said that PSGP is the only grant available with funds dedicated to port security.

Conclusions

From 2018 through 2024, FEMA awarded $690 million in PSGP grants to 82 ports across the U.S. to fund activities and equipment that protect critical U.S. port infrastructure from threats. However, the PSGP grant announcement does not include all application evaluation criteria or all factors used to make award recommendations, as federal regulations require. Including all application evaluation criteria and factors FEMA may use in selecting applications for award in the PSGP grant announcement, as federal regulations require, would make the process more transparent and, in doing so, help maximize fairness to applicants. It could also lead to applications that are better aligned with the evaluation criteria FEMA uses when awarding PSGP funds to enhance port security.

In addition, FEMA has not fully assessed the PSGP application evaluation process to ensure that its outcomes align with their multiple goals for the program. These goals include funding projects in high-risk port areas, prioritizing projects aligned with national priorities, and prioritizing projects that are highly effective and located in lower-risk port areas. Assessing each step of the application evaluation process and making adjustments, as appropriate, could help FEMA ensure that the outcome of the PSGP application evaluation process is aligned with FEMA’s goals for the program, consistent with the authorizing statue.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following three recommendations to DHS:

The Secretary of Homeland Security should ensure that the Administrator of FEMA, in consultation with the Commandant of the Coast Guard, updates the PSGP grant announcement to fully describe the application evaluation process, including all application review criteria and their relative weights. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of Homeland Security should ensure that the Administrator of FEMA, in consultation with the Commandant of the Coast Guard, updates the PSGP grant announcement to include all factors or elements other than merit criteria that FEMA may use in selecting applications for award. (Recommendation 2)

The Secretary of Homeland Security should ensure that the Administrator of FEMA, in consultation with the Commandant of the Coast Guard, assesses each step of the PSGP application evaluation process to determine if the results are consistent with FEMA’s goals for distributing the program’s funds and make adjustments, as appropriate. (Recommendation 3)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to DHS and the Department of Transportation for review and comment. DHS provided written comments, which are reproduced in appendix V. In its written comments, DHS concurred with all three of our recommendations and identified actions that it has taken, or plans to take, to implement them. DHS also provided technical comments, which we incorporated ad appropriate. The Department of Transportation did not have comments on the draft report.

We are sending copies to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Homeland Security, the Secretary of Transportation, and other interested parties. In addition, this report is available at no charge on the GAO web site at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at MacLeodH@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix VI.

Heather MacLeod

Director, Homeland Security and Justice

List of Requesters

The Honorable Andrew A. Garbarino

Chairman

Committee on Homeland Security

House of Representatives

The Honorable Dale Strong

Chairman

Subcommittee on Emergency Management and Technology

Committee on Homeland Security

House of Representatives

The Honorable Carlos Gimenez

Chairman

Subcommittee on Transportation and Maritime Security

Committee on Homeland Security

House of Representatives

The Honorable John Moolenaar

Chairman

Select Committee on the Chinese Communist Party

House of Representatives

This report examines the (1) types and locations of projects awarded Port Security Grant Program (PSGP) funds; (2) PSGP competitive grant process and the extent to which the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) followed certain required and recommended practices for such grants; and (3) extent to which FEMA awarded PSGP funds to projects expected to mitigate key port vulnerabilities. To address these objectives and obtain background information, we reviewed relevant statutes and regulations and internal policies for FEMA’s grant programs.[65] We also reviewed previous GAO reports related to FEMA’s risk-informed preparedness grant programs, including PSGP.[66]

To address our first objective and inform the remaining objectives, we collected and analyzed FEMA data on grant applications and awards from fiscal years 2018 through 2024. We selected this time frame because it provided sufficient data for identifying trends over time and through several 3-year grant performance cycles.[67] The fiscal year 2024 award cycle was the most recently completed at the time of our review.

We analyzed FEMA data on the number of grants and funds awarded to projects from fiscal years 2018 through 2024 by port area.[68] We also analyzed additional data fields, including those that identified projects that addressed a national priority and those that identified projects that addressed a key local vulnerability. FEMA’s data includes some fields populated by U.S. Coast Guard officials as part of the PSGP application review process. For example, in 2021, Coast Guard began documenting project categories for PSGP applications. We used Coast Guard’s project categories, documented in FEMA’s data, to analyze the number of grants and funds awarded by project category from fiscal years 2021 through 2024.[69]

We assessed the reliability of FEMA’s application and award data by checking for missing values, errors, or inconsistencies. We identified some errors and inconsistencies, such as changes in port location names, across the 7 years of grant data. We confirmed port location names with FEMA officials and made updates, as appropriate. We also interviewed FEMA and Coast Guard officials to understand the sources for each field in the data and any steps FEMA and Coast Guard took to ensure data accuracy. For example, we interviewed Coast Guard officials to understand how they developed the project categories and implemented guidance to ensure that staff would apply the categories consistently during the PSGP application evaluation process. We determined that the FEMA data were sufficiently reliable to describe the number, amounts, and port locations of grants awarded each fiscal year from fiscal year 2018 through 2024 and whether projects addressed national priorities or local vulnerabilities. We also determined the data were sufficiently reliable to describe the number and amounts of grants awarded by project category from fiscal year 2021 through 2024. For reporting purposes, we rounded percentages to the nearest whole percent and dollars to the nearest 0.1 million.

For each of our research objectives, we interviewed port stakeholders to gather their perspectives on PSGP. Port stakeholders we interviewed included Coast Guard and other federal officials and representatives from (1) port authorities; (2) state and local law enforcement and first responders; and (3) private sector entities. They included PSGP applicants and recipients. Port stakeholders we interviewed were members of nine Coast Guard-led Area Maritime Security Committees representing 32 FEMA port areas.[70] We selected these locations based on geographic dispersion, the amount of PSGP grants they received, and the frequency of their PSGP grant awards from fiscal years 2017 through 2023, the most recent data available at the time we made our selections. Specifically, we selected locations that represented east coast, west coast, and lake and river ports. We selected locations that received (1) a relatively high amount of grant funds overall and grants in each year we analyzed or (2) any amount of grant funds overall and grants in most of the years we analyzed. Table 3 shows the Area Maritime Security Committees and FEMA port areas from which we interviewed stakeholders.

Table 3: Area Maritime Security Committees and FEMA Port Areas Included in Port Stakeholder Interviews

|

Area Maritime |

FEMA port area |

State(s) |

|

Columbia River |

Columbia-Snake River System |

OR, WA, ID |

|

Houston-Galveston |

Freeport |

TX |

|

Houston-Galveston |

TX |

|

|

Lake Michigan |

Escanaba |

MI, WI |

|

|

Green Bay |

WI |

|

|

Milwaukee |

WI |

|

|

Muskegon-Grand Haven |

MI |

|

|

Southern Tip Lake Michigan |

IL, MI, IN |

|

Southeast Florida |

Miami |

FL |

|

|

Palm Beach |

FL |

|

|

Port Everglades |

FL |

|

New York |

New York-New Jersey |

NY, NJ |

|

Ohio Valley |

Chattanooga |

TN |

|

|

Cincinnati |

OH |

|

|

Guntersville |

AL |

|

|

Huntington-Tri-State |

WV, OH, KY |

|

|

Louisville |

KY |

|

|

Mid-Ohio Valley |

OH, WV |

|

|

Mount Vernon |

IN |

|

|

Nashville |

TN |

|

|

Owensboro |

KY |

|

|

Paducah-Metropolis |

KY, IL |

|

|

Pittsburgh |

PA |

|

|

Southeast Missouri |

MO |

|

Puget Sound |

Puget Sound |

WA |

|

Southeastern New England |

Nantucket Sound |

MA |

|

Narragansett-Mt. Hope Bays |

RI, MA |

|

|

St. Louis |

Kansas City |

MO |

|

|

Mid-America-Quad Cities |

IA, IL, MO |

|

|

Minneapolis-St. Paul |

MN |

|

|

Peoria-Illinois Waterway |

IL |

|

|

St. Louis |

MO, IL |

Source: GAO and GAO analysis of Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) data. | GAO‑25‑107587

Note: FEMA combines individual ports into larger regions called FEMA port areas based on FEMA’s assessment that ports in the designated area share geographic proximity, waterways, and risk.

We also visited two port areas—New York-New Jersey and Houston-Galveston—to interview PSGP award recipients and observe PSGP-funded projects. We aggregated the information from these interviews with other port stakeholder interviews. We selected these port areas because they were among those that received the most funding between fiscal years 2018 and 2024. We asked the port stakeholders we interviewed about their perspectives on PSGP; these perspectives are not generalizable to perspectives from port stakeholders in all Area Maritime Security Committees or all FEMA port areas.

To address our second objective, we reviewed FEMA’s fiscal year 2024 PSGP grant announcement and collected documentation and interviewed officials about FEMA and Coast Guard’s application evaluation and award recommendation processes. We selected fiscal year 2024 because it was the most recently completed grant cycle at the time of our review. We compared the description of the application evaluation and award recommendation processes in the fiscal year 2024 grant announcement with information about these processes we collected from FEMA and the Coast Guard. This information included guidance on the Coast Guard-led field review, such as scoring rubrics and training materials. It also included FEMA guidance used in the national panel review’s application evaluation process. We also reviewed FEMA documentation describing its PSGP port area risk methodology and project scoring process. To obtain additional information about the application evaluation and award recommendation process, including their respective roles in PSGP, we interviewed officials from FEMA’s Grant Programs Directorate, Coast Guard headquarters, the Transportation Security Administration, and the Department of Transportation’s Maritime Administration.

We evaluated FEMA’s grant announcement against selected provisions of the Uniform Administrative Requirements, Cost Principles, and Audit Requirements for Federal Awards.[71] These requirements are in federal regulations and provide a government-wide framework for grants management. We selected these sections of the regulations because they contain requirements for how FEMA is to design its PSGP application evaluation process and select applications for award, a significant aspect of FEMA’s management of the program. Specifically, we evaluated the extent to which the information described in the fiscal year 2024 grant announcement aligned with FEMA and Coast Guard’s processes to evaluate applications and select applications for award, as the regulations require. We interviewed FEMA officials to understand how they developed the grant announcement, including the internal processes and guidance used to decide what information to include in the grant announcement.[72]

In addition, we evaluated FEMA’s PSGP scoring process by comparing the scoring process FEMA and Coast Guard used to evaluate applications with PSGP statutory requirements and goals described in FEMA documentation, such as the grant announcement, and by FEMA officials. To understand the calculations used in the scoring process, we reviewed FEMA and Coast Guard documentation and interviewed officials from both agencies. We also reviewed Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government and determined that the monitoring component of internal controls was significant to this objective, along with the underlying principle that management should establish and operate monitoring activities to monitor the internal control system and evaluate the results.[73] We compared the results of FEMA and Coast Guard’s PSGP application scoring process with their program goals and examined the extent to which FEMA had monitored the scoring process and evaluated its results.

To address our third objective, we analyzed FEMA data on PSGP awards to identify projects awarded funds that aligned and did not align with key port vulnerabilities. We analyzed this data by port area for fiscal years 2018 through 2024. In addition, we reviewed documentation on FEMA’s Port Risk Assessment Methodology, a tool FEMA is implementing to measure port area risk and risk reduction. We aggregated information from our interviews with port stakeholders to analyze stakeholder perspectives on the extent to which PSGP funds mitigated port vulnerabilities, including perspectives on the benefits and limitations of PSGP.

We conducted this performance audit from May 2024 to September 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Table 4: Port Security Grant Program Funds Awarded by FEMA Port Area, Fiscal Years 2018 through 2024

|

FEMA port area |

State or territory |

Funds awarded (dollars) |

Received funds |

|

New York-New Jersey |

NY, NJ |

128,675,849 |

√ |

|

Los Angeles-Long Beach |

CA |

60,693,586 |

√ |

|

Houston-Galveston |

TX |

47,237,998 |

√ |

|

New Orleans |

LA |

33,350,500 |

√ |

|

San Francisco Bay |

CA |

33,230,783 |

√ |

|

Delaware Bay |

DE, NJ, PA |

28,204,820 |

√ |

|

Puget Sound |

WA |

26,902,284 |

√ |

|

Sabine-Neches River |

TX, LA |

25,187,371 |

√ |

|

Tampa Bay |

FL |

18,121,864 |

√ |

|

Hampton Roads |

VA |

17,784,511 |

√ |

|

Southern Tip of Lake Michigan |

IL, MI, IN |

15,599,403 |

√ |

|

Baltimore |

MD |

15,590,029 |

√ |

|

Corpus Christi |

TX |

15,579,814 |

√ |

|

Boston |

MA |

15,070,080 |

√ |

|

Long Island Sound |

NY, CT |

14,498,362 |

√ |

|

Charleston |

SC |

13,166,333 |

√ |

|

Port Everglades |

FL |

11,286,451 |

√ |

|

San Diego |

CA |

11,190,096 |

√ |

|

Jacksonville |

FL |

11,182,149 |

√ |

|

Mobile |

AL |

10,582,704 |

√ |

|

Miami |

FL |

10,041,792 |

√ |

|

Outside a FEMA port areaa |

Variousa |

8,685,625 |

— |

|

Honolulu |

HI |

8,377,235 |

— |

|

Wilmington |

NC |

7,416,362 |

√ |

|

Savannah |

GA |

6,766,054 |

√ |

|

Memphis |

TN, AR |

6,667,406 |

√ |

|

Port Canaveral |

FL |

5,799,600 |

— |

|

Minneapolis-St. Paul |

MN |

5,612,407 |

— |

|

Lake Charles |

LA |

5,241,330 |

√ |

|

Apra Harbor |

GU |

4,993,602 |

— |

|

Louisville |

KY |

4,891,744 |

√ |

|

Cincinnati |

OH |

4,717,115 |

√ |

|

Cook Inlet |

AK |

4,114,282 |

— |

|

St. Louis |

MO, IL |

4,083,687 |

√ |

|

Morehead City |

NC |

4,031,740 |

— |

|

Pensacola |

FL |

3,514,763 |

— |

|

Port Hueneme |

CA |

3,431,878 |

— |

|

Columbia-Snake River System |

OR, WA, ID |

3,306,227 |

— |

|

Gulfport |

MS |

2,396,038 |

√ |

|

Narragansett-Mt. Hope Bays |

RI, MA |

2,076,770 |

— |

|

Cleveland |

OH |

1,923,900 |

— |

|

Mid-America-Quad Cities |

IA, IL, MO |

1,882,865 |

— |

|

Detroit |

MI |

1,824,883 |

— |

|

Portland |

ME |

1,799,185 |

— |

|

Key West |

FL |

1,666,576 |

— |

|

Freeport |

TX |

1,527,113 |

— |

|

San Juan |

PR |

1,446,798 |

— |

|

Palm Beach |

FL |

1,341,179 |

— |

|

Nashville |

TN |

1,336,785 |

— |

|

Duluth-Superior |

MN, WI |

1,271,411 |

— |

|

Huntington-Tri-State |

WV, OH, KY |

1,243,279 |

— |

|

Pascagoula |

MS |

1,081,339 |

— |

|

Nantucket Sound |

MA |

907,875 |

— |

|

Milwaukee |

WI |

895,775 |

— |

|

Toledo |

OH |

847,643 |

— |

|

St. Thomas |

VI |

776,780 |

— |

|

Monroe |

MI |

770,983 |

— |

|

Valdez |

AK |

732,717 |

— |

|

Port Fourchon Louisiana Offshore Oil Port |

LA |

677,216 |

— |

|

Panama City |

FL |

642,103 |

— |

|

Erie |

PA |

589,206 |

— |

|

Paducah-Metropolis |

KY, IL |

578,327 |

— |

|

Guntersville |

AL |

561,674 |

— |

|

Southeast Missouri |

MO |

542,250 |

— |

|

Chattanooga |

TN |

415,777 |

— |

|

Peoria-Illinois Waterway |

IL |

395,250 |

— |

|

Portsmouth |

NH |

387,597 |

— |

|

Green Bay |

WI |

364,440 |

— |

|

Victoria-Port Lavaca-Point Comfort |

TX |

357,654 |

— |

|

Kansas City |

MO |

320,172 |

— |

|

Buffalo |

NY |

308,335 |

— |

|

Muskegon-Grand Haven |

MI |

262,906 |

— |

|

El Segundo |

CA |

250,000 |

— |

|

Vicksburg |

MS |

220,905 |

— |

|

St. Clair River |

MI |

152,719 |

— |

|

Pittsburgh |

PA |

118,980 |

— |

|

Guayanilla |

PR |

67,590 |

— |

|

Morgan City |

LA |

60,498 |

— |

|

Mount Vernon |

IN |

54,675 |

— |

|

Mid-Ohio Valley |

OH, WV |

43,688 |

— |

|

Lynn Canal |

AK |

24,730 |

— |

|

Owensboro |

KY |

22,583 |

— |

|

Escanaba |

MI, WI |

2,995 |

— |

|

Total |

690,000,000 |

|

Legend: √ = Yes; — = No

Source: GAO analysis of Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) data. | GAO‑25‑107587