DISASTER RECOVERY

Use of HUD Block Grant Funds to Meet Cost-Share Requirements

Report to the Ranking Member Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

U.S. Senate

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to the Ranking Member, Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, U.S. Senate.

For more information, contact: Jill M. Naamane at naamanej@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

Communities that receive Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) disaster assistance are generally required to cover a portion of recovery costs, known as the nonfederal cost share. Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR) and Mitigation (CDBG-MIT) funds, which are administered by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), can be used for this purpose.

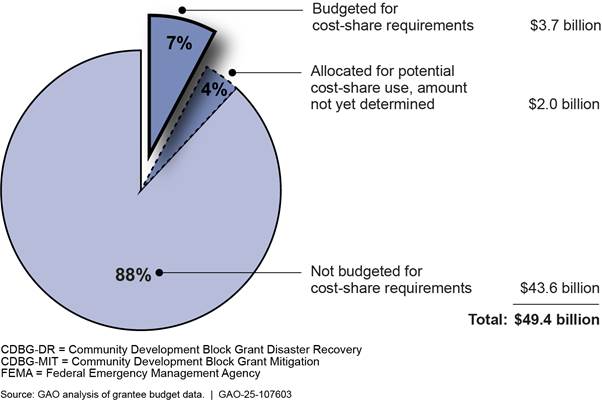

For disasters occurring from January 2017 through January 2023, grantees budgeted about 7 percent ($3.7 billion) of the $49.4 billion in CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds to meet FEMA cost-share requirements. In addition, four grantees allocated another $2 billion that could be used for cost share. However, as of December 2024, grantees had not yet determined how much of the $2 billion would be used for this purpose.

Different timelines and requirements can make it difficult for grantees to use CDBG-DR or CDBG-MIT funds for FEMA cost share, according to prior GAO work and seven grantees GAO interviewed:

· Timing of funding availability. CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds have historically become available later than FEMA funds. This can complicate planning, particularly when projects have already begun.

· Income requirements. Grantees generally must use at least 70 percent of CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds to assist people with low and moderate incomes, a requirement that does not apply to FEMA funds. This can be challenging, particularly when the benefits of large FEMA-funded infrastructure projects are difficult to isolate for these individuals alone.

· Wage and labor requirements. Grantees must follow federal wage and labor requirements when using CDBG-DR or CDBG-MIT funds for construction, including rules on how much and how often workers must be paid. However, these requirements do not apply to the two FEMA programs for which almost all of the CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds are used to meet cost-share requirements. As a result, FEMA officials said the agency may not cover the additional costs these requirements may impose.

Options for addressing these challenges include aligning HUD and FEMA requirements or eliminating the cost-share requirement altogether. However, these options present trade-offs and may require statutory changes. For example, eliminating the cost-share requirement completely would require congressional action and could result in FEMA funding fewer projects.

Implementing prior GAO recommendations on improving the federal disaster recovery framework could also help address these challenges. In a November 2022 report (GAO-23-104956), GAO recommended that Congress consider establishing an independent commission to propose reforms to the federal government’s approach to disaster recovery. GAO also recommended that HUD and FEMA take steps to better manage fragmentation across recovery programs. Implementing these recommendations could help alleviate challenges in using CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds to meet cost-share requirements.

Why GAO Did This Study

Natural disasters affect hundreds of U.S. communities each year, and the federal government provides billions of dollars to support recovery efforts. The Stafford Act generally requires communities to contribute up to 25 percent in nonfederal cost share for assistance provided through FEMA’s Public Assistance and Hazard Mitigation Grant programs.

GAO was asked to review the use of CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds to meet nonfederal cost-share requirements. This report examines (1) the portion of these funds that grantees have budgeted to meet cost-share requirements and (2) key challenges selected grantees face in using the funds for this purpose and options to address these challenges.

GAO focused on FEMA programs because they accounted for most of the cost-share funds. GAO collected and analyzed budget data from 52 of the 55 grantees that received CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds for recovery from disasters that occurred from January 2017 through January 2023.

GAO reviewed HUD and FEMA documentation and interviewed officials from both agencies. GAO also interviewed seven grantees. The selected grantees reflected a mix of characteristics, including varying funding amounts, levels of experience with cost share, and type of grant received (CDBG-DR or CDBG-MIT).

Abbreviations

|

CDBG |

Community Development Block Grant |

|

CDBG-DR |

Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery |

|

CDBG-MIT |

Community Development Block Grant Mitigation |

|

DHS |

Department of Homeland Security |

|

FEMA |

Federal Emergency Management Agency |

|

HMGP |

Hazard Mitigation Grant Program |

|

HUD |

Department of Housing and Urban Development |

|

OIG |

Office of Inspector General |

|

Stafford Act |

Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

September 29, 2025

The Honorable Gary C. Peters

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

United States Senate

Dear Senator Peters:

Under the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (Stafford Act), the federal government provides financial assistance to disaster-stricken communities for response, recovery, and resilience following major disasters.[1] From fiscal years 2015 through 2024, appropriations for disaster assistance totaled at least $448 billion.[2] The Stafford Act generally requires communities to cover a share of specified disaster-related costs, known as the nonfederal cost share, while federal relief covers the remainder.[3]

Although the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) is the federal department with primary responsibility for coordinating disaster response and recovery, the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) is also involved in disaster recovery. Within DHS, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has lead responsibility for delivering much of the assistance, operating programs like the Public Assistance program and the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP).[4] Both programs generally have a cost-share requirement of 25 percent. Congress also appropriates additional funding to HUD’s Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) program for disaster recovery (CDBG-DR) and mitigation (CDBG-MIT) through supplemental appropriations. HUD awards this funding for long-term disaster recovery, mitigation, and other related purposes under the CDBG program statutory authority.[5]

Congress appropriated $49.5 billion in CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds to respond to disasters occurring from January 2017 through January 2023. HUD awarded these funds to 55 state, territorial, and local governments (grantees).[6] Grantees are allowed to use CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds to fulfill cost-share requirements of other federal disaster assistance programs, including FEMA’s Public Assistance and HMGP.[7]

Typically, CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds are allocated later than other forms of federal disaster assistance and administered over a longer time frame. We have reported on and made recommendations to improve the coordination among federal disaster assistance programs, including CDBG-DR and FEMA’s Public Assistance and HMGP.[8] Further, some stakeholders have questioned whether cost-share requirements burden communities, potentially making disaster relief inaccessible to those unable to pay.

You asked us to review the use of CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds to satisfy cost-share requirements for other sources of federal disaster assistance. Further, the American Relief Act, 2025 provided GAO supplemental funds to audit issues related to presidentially declared major disasters that occurred in 2023 and 2024.[9] This report examines (1) the portion of CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds allocated to grantees for disasters from January 2017 through January 2023 that has been budgeted to meet cost-share requirements and (2) key challenges, if any, selected grantees faced in using these funds to meet cost-share requirements and options to address them.

For our first objective, because HUD does not require grantees to report data on the portion of CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds budgeted or expended for cost-share requirements, we requested these data from all 55 grantees that administered the $49.5 billion appropriated for disasters occurring from January 2017 through January 2023.[10] Specifically, we collected and analyzed data from 52 grantees on 100 of the 104 CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT grants to calculate the portion of funds grantees budgeted and expended to meet cost-share requirements, as of December 2024.[11]

To assess the reliability of the grantee data, we obtained information from grantees on the source of the data and system edit checks or controls in place to help ensure the data were entered accurately. We found these data to be sufficiently reliable to report on the portion of CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds budgeted and expended to meet cost-share requirements. We also found the data sufficiently reliable to identify the key federal programs for which these funds were budgeted to meet cost-share requirements.

For our second objective, we focused on FEMA’s Public Assistance and HMGP because we determined that these were the primary programs for which grantees budgeted funds for cost-share requirements. We reviewed relevant laws and HUD and FEMA documentation. For example, we reviewed the Federal Register notices allocating the CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds for the January 2017–January 2023 disasters and guidance on the Public Assistance and HMGP cost-share requirements. In addition, we reviewed our prior reports and reports from the HUD Office of Inspector General (OIG) and others on challenges HUD and grantees have faced in administering CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds and on the overall federal approach to disaster recovery.[12]

We also interviewed officials from HUD, FEMA, and a nongeneralizable sample of seven grantees—California, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, Nebraska, Puerto Rico, and West Virginia—as well as state emergency management agencies in these states. These grantees were selected to represent a mix of grant sizes, types (CDBG-DR or CDBG-MIT), and geographic locations. Appendix I describes our objectives, scope, and methodology in greater detail.

We conducted this performance audit from May 2024 to September 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Federal Role in Disaster Recovery

Natural disasters affect hundreds of U.S. communities each year. The Stafford Act establishes the process for states, territories, and Tribes to request a presidential major disaster declaration.[13] If approved, this declaration triggers a variety of federal response and recovery programs for government and nongovernmental entities, households, and individuals.[14] State and local officials are responsible for disaster response and recovery activities, but the President may declare a disaster after the governor of a state requests a disaster declaration based on the finding that the severity of the damage is beyond the combined capabilities of state and local governments. This declaration is the key mechanism by which the federal government becomes involved in funding and coordinating response and recovery activities.

At least 30 federal agencies administer disaster assistance programs and activities. DHS is the federal department with primary responsibility for coordinating disaster response and recovery. Within DHS, FEMA has lead responsibility. Other federal agencies, including HUD, also play roles in disaster recovery activities. In February 2025, we added “Improving the Delivery of Federal Disaster Assistance” to our High-Risk List, noting the large-scale fragmentation across federal disaster assistance programs.[15]

FEMA Recovery Programs

FEMA operates disaster recovery programs, including Public Assistance and HMGP, for state, territorial, tribal, and local governments and certain nonprofit organizations (FEMA recipients) affected by disasters. Both programs are established under the Stafford Act and funded through FEMA’s Disaster Relief Fund.[16] Generally, FEMA recipients must pay a share of the costs—known as the nonfederal cost share—under both programs.

Public Assistance. Public Assistance is the largest disaster recovery grant program established under the Stafford Act. It is available to eligible applicants in areas affected by a major disaster for which such assistance has been approved.[17] There is no predetermined limit to the amount of Public Assistance a community can receive. The program reimburses FEMA recipients for the cost of disaster-related debris removal, emergency measures to protect life and property, and permanent repair work for damaged or destroyed infrastructure. Permanent repair work includes projects such as restoration and repair of roads, bridges, water control facilities, buildings, equipment, utilities, and parks and recreational facilities. FEMA recipients may also apply for funding for hazard mitigation measures in conjunction with permanent work projects.[18]

The nonfederal cost share for Public Assistance is generally 25 percent but has, in some cases, been reduced to 10 percent or waived entirely.[19]

Hazard Mitigation Grant Program. HMGP is designed to support cost-effective hazard mitigation measures that substantially reduce the risk of, or increase resilience to, future damage, hardship, loss, or suffering in any area affected by a major disaster.[20] It funds a wide range of hazard mitigation projects, generally executed by state, tribal, or local governments. Examples include acquiring existing properties to limit future development in flood-prone areas and adding shutters to windows for wind protection.

HMGP funds can be awarded to states, territories, or Tribes with a major disaster declaration, which can then allocate the funds to any eligible hazard mitigation activity within their jurisdictional boundaries. HMGP generally has a nonfederal cost share of 25 percent.[21]

FEMA also operates disaster recovery programs that are not authorized under the Stafford Act, such as the Flood Mitigation Assistance Swift Current program. This program provides grants to mitigate buildings insured through the National Flood Insurance Program after a major disaster declaration following a flood-related event, with the goal of reducing future flood damage risk.[22]

HUD Recovery Programs

HUD’s Community Development Block Grant was established in 1974 with the stated goal of developing viable urban communities by providing decent housing and expanding economic opportunities, principally for low- and moderate-income persons.[23] Since 1992, Congress has passed several dozen supplemental appropriations for CDBG after disasters, which have provided the funding for CDBG-DR. In 2018 and 2019, HUD received CDBG-DR appropriations that specifically included funding for disaster mitigation, which became CDBG-MIT. After supplemental appropriations are made, HUD issues a notice in the Federal Register announcing allocations to eligible grantees.

Grantees develop action plans that outline activities to be funded with the CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds, which HUD must approve before grantees can access the funds. Grantees may use these funds to satisfy the cost-share requirements of disaster assistance programs when the funds are used for eligible CDBG-DR activities.[24]

Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery. CDBG-DR provides grants to help communities with unmet needs after a disaster, especially in low- and moderate-income areas. Grantees may use their CDBG-DR grants to address a wide range of unmet recovery needs related to housing, infrastructure, and economic revitalization.[25] Eligible activities include acquisition of damaged properties, rehabilitation and reconstruction of damaged homes, rehabilitation of public facilities and infrastructure such as neighborhood centers and roads, and certain public service activities.

Community Development Block Grant Mitigation. After enactment of the Further Additional Supplemental Appropriations for Disaster Relief Requirements Act, 2018, HUD allocated $15.9 billion in CDBG funds specifically for mitigation activities related to qualifying disasters in 2015, 2016, and 2017, establishing CDBG-MIT.[26] According to HUD, CDBG-MIT grants provide eligible grantees the opportunity to implement strategic, high-impact activities to mitigate disaster risks and reduce future losses in areas affected by recent disasters. These projects aim to reduce the risk of damage to community services that benefit human health, safety, or economic security during natural disasters.[27] According to HUD, CDBG-MIT activities should align with other federal hazard mitigation programs, with a goal of maximizing impact through coordination with other federal resources and private-public partnerships.

CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT Requirements

Because CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds are provided under the basic framework of HUD’s conventional CDBG program, they are subject to this program’s statutory and regulatory requirements. They are also subject to any disaster-specific requirements or waivers established by HUD through Federal Register notices. For example:

Low- and moderate-income requirement. The Housing and Community Development Act, which established the CDBG program, requires that at least 70 percent of grant funds be expended on activities that benefit individuals with low and moderate incomes.[28] HUD generally does not use the waiver and alternative requirement authority provided by the appropriations language to alter this requirement for CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds.[29]

Federal labor standards requirements. CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds are subject to federal labor standards for construction work. For example, HUD-assisted construction projects are subject to prevailing wage requirements established in the Davis-Bacon and Related Acts.[30] Federal regulations also require that these construction contracts include labor standards clauses and wage determinations, and that contractors maintain payroll and basic records for all laborers and mechanics.[31]

Environmental reviews. The National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 and other related federal environmental laws require federal agencies, including FEMA and HUD, to conduct environmental reviews for all federally assisted construction projects.[32] This process is to ensure that proposed projects do not negatively affect the surrounding environment and that the property site will not have adverse environmental or health effects on end users.

Grantees Have Budgeted About 7 Percent of CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT Funds for FEMA Cost-Share Requirements

According to grantee data we collected as of December 2024, about 7 percent of the CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds allocated for disasters occurring from January 2017 through January 2023 were budgeted to meet the cost-share requirements of FEMA disaster assistance programs.[33]

We collected these data from grantees because HUD does not track these data. The HUD OIG found that HUD recommends but does not require that grantees report data to HUD on their use of CDBG-DR to meet cost-share requirements, creating a risk of incomplete or inaccurate reporting.[34] The HUD OIG recommended that HUD require grantees to report these data.[35]

As of December 2024, 18 of the 52 grantees had budgeted about $3.7 billion (or 7 percent) of the $49.4 billion in CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds allocated for the disasters in our review to meet FEMA cost-share requirements (see fig. 1).[36] The funds budgeted for cost-share requirements ranged widely, from less than 1 percent to 31 percent of each grantee’s total grant allocation.[37]

Figure 1: CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT Funds Budgeted for FEMA Cost-Share Requirements for January 2017–January 2023 Disasters, as of December 2024

Notes: Amounts do not sum because of rounding. The Department of Housing and Urban Development awarded 104 CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT grants to 55 grantees for recovery from January 2017–January 2023 disasters. We excluded two grants totaling $65.4 million—one did not have an approved action plan, and the other was being transferred to another state agency. One additional grantee, with two grants totaling $50.6 million, did not respond to our data request. As a result, the $49.4 billion reflects grants awarded to 52 grantees. In addition, the $3.7 billion excludes $31 million in CDBG-DR funds budgeted to meet the cost share of non-FEMA programs.

The $3.7 billion in CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds that grantees had budgeted for cost-share requirements as of December 2024 could change over the course of the grants’ periods of performance.[38] Grantees can revise budgets to address shifting unmet needs. For example, one grantee originally allocated $43.7 million to a cost-share activity but later reallocated $10 million to a non-cost-share activity. As discussed later, grantees sometimes experience challenges using these funds for cost-share purposes, and some reallocate funds to other non-cost-share activities. Of the 52 grantees in our analysis, 15 told us they had amended or canceled activities.

In addition to the $3.7 billion, four grantees allocated about $2 billion to 12 activities that included a cost-share component but had not, as of December 2024, determined how much of these funds would be used for that purpose. These activity allocations ranged from about $522,000 to $1.2 billion.

These four grantees told us the 12 activities had either not yet started or were still in the project selection phase. As a result, grantees had not determined how many projects would use CDBG-DR or CDBG-MIT funds to meet cost-share requirements. Because grantees had not yet determined how much of the $2 billion allocated to these activities would be used for cost share, the total portion of the $49.4 billion that may ultimately support cost-share requirements could exceed the $3.7 billion grantees budgeted for this purpose as of December 2024.

Of the $3.7 billion budgeted for cost-share requirements, 70 percent ($2.6 billion) were CDBG-DR funds and 30 percent ($1.1 billion) were CDBG-MIT funds. Most of the CDBG-DR funds were budgeted to meet the cost-share requirements of the Public Assistance program, and nearly all of the CDBG-MIT funds were budgeted to meet the cost-share requirements for HMGP (see table 1).

Table 1: CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT Funds Budgeted for FEMA Cost-Share Requirements for January 2017–January 2023 Disasters, as of December 2024

Dollars in millions

|

|

CDBG-DR |

CDBG-MIT |

Aggregate total of CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds |

|||||||

|

FEMA disaster assistance program |

Amount budgeted |

Percent budgeted |

Amount expended |

Percent of budgeted funds expended |

Amount budgeted |

Percent budgeted |

Amount expended |

Percent of budgeted funds expended |

Total amount budgeted |

Total amount expended |

|

FEMA Public Assistance program |

$2,197.5 |

84.7% |

$271.8 |

12.4% |

$0.4 |

0.0%a |

$0.1 |

15.7% |

$2,197.9 |

$271.8 |

|

FEMA Hazard Mitigation Grant Program |

$391.4 |

15.1% |

$12.3 |

3.2% |

$1,103.0 |

100% |

$4.8 |

0.4% |

$1,494.5 |

$17.1 |

|

Other FEMA programsb |

$5.2 |

0.2% |

$0.3 |

6.5% |

$0.9 |

0.0%a |

$0.0 |

0.0% |

$5.3 |

$0.3 |

|

All FEMA programs |

$2,594.1 |

100.0% |

$284.4 |

11.0%c |

$1,103.5 |

100.0% |

$4.8 |

0.4%c |

$3,697.6 |

$289.3 |

Legend: CDBG-DR = Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery; CDBG-MIT = Community Development Block Grant Mitigation; FEMA = Federal Emergency Management Agency

Source: GAO analysis of grantees’ CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT budget and expenditure data. | GAO‑25‑107603

Notes: Totals may not sum because of rounding. The table excludes an additional $31 million in CDBG-DR funds grantees budgeted to meet the cost-share requirements of the Economic Development Administration’s Economic Adjustment Assistance program, the Federal Highway Administration’s Emergency Relief Program, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ Flood Damage Reduction Projects.

aThe percent budgeted is less than 0.1 percent.

bOther FEMA programs are the Flood Mitigation Assistance grant program (including the Swift Current program), Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities Program, and Pre-Disaster Mitigation Grant Program.

cThe “Percent of budgeted funds expended” in the “All FEMA programs” row is not a sum of the percentages in the rows above because it is the total expended funds divided by the total budgeted funds.

Of the CDBG-DR funds budgeted for cost-share requirements of FEMA programs, grantees budgeted 85 percent, or $2.2 billion, for Public Assistance projects. This is likely because both CDBG-DR and Public Assistance funds aim to address disaster-related damage.

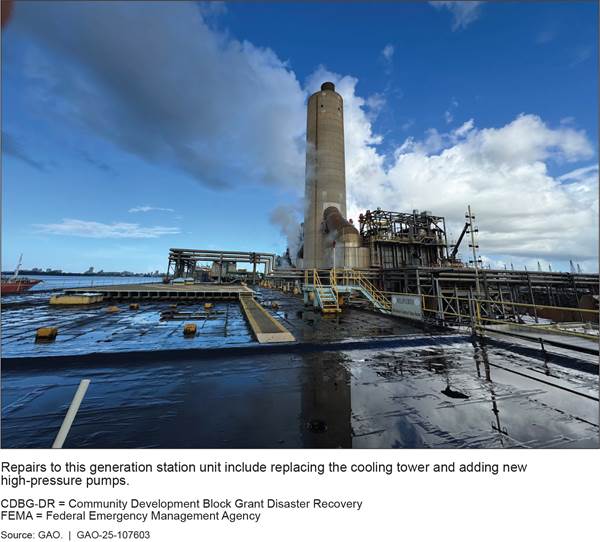

For example, Puerto Rico is using CDBG-DR funds for a Public Assistance project to repair the San Juan Central Generation Station. According to officials, the station supplies 400 megawatts to the island’s electrical grid. The project includes major repairs to two of the station’s units (see fig. 2). The estimated project cost is $75 million, with an estimated amount of $7.5 million in CDBG-DR funds budgeted to meet the cost-share requirement. According to the grantee, the project will increase efficiency, reliability, and capacity and reduce the risk of forced outages.

Figure 2: FEMA Public Assistance Project Using CDBG-DR Funds for the Cost-Share Requirement: San Juan Central Generation Station

Nearly all the CDBG-MIT funds (about $1.1 billion) budgeted for the cost-share requirements of FEMA programs were budgeted for HMGP projects. This is likely because both funding sources are intended to mitigate disaster risks and HMGP has a 25 percent cost-share requirement, which can be challenging for some states and local governments to fund from available resources.

For example, Louisiana is using CDBG-MIT funds for an HMGP project to upgrade the Conway Bayou Pump Station (see fig. 3). The project involves installing two new pumps on a new platform to expand the intake basin and direct water along the natural flow of the Bayou Conway, a flood-prone area. This upgrade is expected to reduce flooding and related damage to nearby homes. The project’s estimated cost is $7.2 million, with $6.4 million in CDBG-MIT funds budgeted to meet the cost-share requirement.[39]

Figure 3: FEMA Hazard Mitigation Grant Program Project Using CDBG-MIT Funds for the Cost-Share Requirement: Conway Bayou Pump Station

Varying Program Requirements Can Create Challenges for Grantees; Options, Including Broader Reform Efforts, Exist to Address Them

Timing differences in the availability of HUD and FEMA funds can make it difficult for grantees to plan for and meet certain HUD requirements when using CDBG-DR or CDBG-MIT funds for FEMA cost share. In addition, according to HUD and selected grantees we interviewed, navigating these requirements is burdensome, particularly given limited state and local capacity. Options exist to address these challenges, but each involves trade-offs or limitations. Implementing our prior recommendations on improving the federal disaster recovery framework could also help address these challenges.

Challenges Include Differing HUD and FEMA Timelines

According to our prior work, CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds can take months and even years to become available to grantees, and funding availability can lag behind FEMA programs. In our November 2022 report on the federal approach to disaster recovery, we found that CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funding was less predictable than FEMA’s Public Assistance and HMGP funding.[40] We also found that CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funding had historically become available later. Specifically, a presidential disaster declaration activates the process for providing funding for these FEMA programs.[41] In contrast, CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT have been funded through supplemental appropriations, which require both presidential and congressional action before HUD can allocate funds to states and localities.

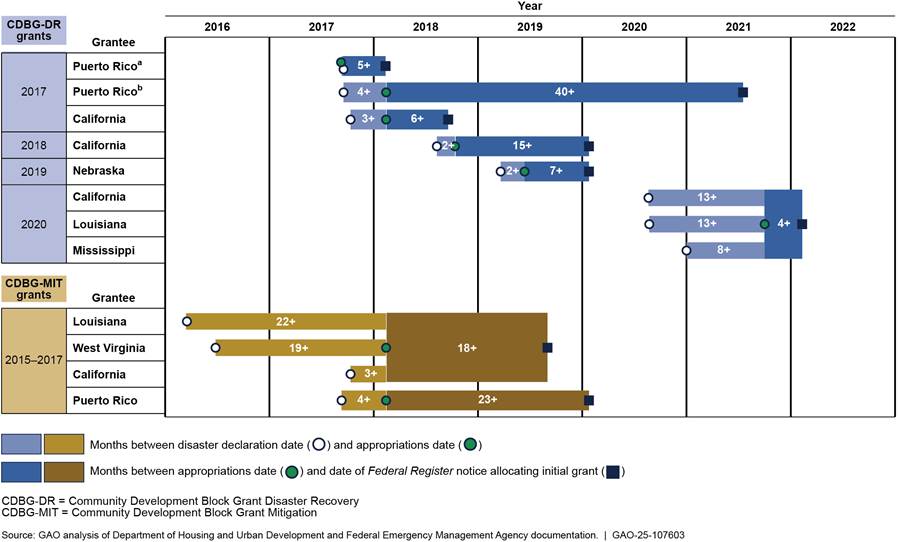

In our March 2019 report on CDBG-DR funds for 2017 disasters, we found delays between key steps in the process.[42] There can be a significant lag (1) between when a disaster occurs and when CDBG-DR funds are appropriated and (2) between when funds are appropriated and when HUD allocates them through Federal Register notices.

Our current review of selected CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT grants that budgeted funds to meet cost-share requirements showed that the time between the disaster declaration and congressional appropriation ranged from more than 2 months to almost 2 years (see fig. 4).[43] The time between appropriation and HUD allocation ranged from more than 4 months to more than 3 years.

Notes: We use (+) to add more specificity to the time frames. For example, “5+” indicates that the time frame is more than 5 months but less than 6 months. California, Louisiana, and Puerto Rico received grants associated with more than one disaster declaration. To illustrate the funding timeline for these grants, we used the date of the first related disaster declaration. In addition, some selected grantees received more than one grant for a single disaster declaration; only one grant per disaster is shown in this figure. The above timelines are based on the effective dates of the disaster declarations and other notices.

aHurricane Irma made landfall on Sept. 6, 2017, Congress appropriated funds for recovery on Sept. 8, 2017, and the President declared it a major disaster on Sept. 10, 2017. This CDBG-DR grant was to address unmet needs related to housing, infrastructure, and economic revitalization.

bThis CDBG-DR grant was to address unmet needs related to repairing and improving Puerto Rico’s electrical power systems.

Consistent with our prior work, officials from HUD, all seven grantees, and six of the seven state emergency management agencies we met with cited the differing timelines for when HUD and FEMA funding becomes available as a major challenge when using CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds to meet FEMA cost-share requirements.

In addition, officials from six of the seven grantees and six of the seven state emergency management agencies we met with said that differing periods of performance for the HUD and FEMA funding complicate planning for cost-share use. Unless Congress or HUD approves an extension, HUD generally requires grantees to expend CDBG-DR funds within 6 years of receipt and CDBG-MIT funds within 12 years.[44]

Grantees can typically use CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds for the cost-share portion only after the FEMA-funded project is nearly complete and FEMA has paid its federal share. FEMA regulations allow recipients up to 4 years following a disaster declaration to complete Public Assistance permanent work projects and up to 6 years to expend HMGP funds, depending on the circumstances at hand. However, FEMA can administratively extend these periods. For example, according to FEMA, as of February 2025, the agency was managing over 600 open major disaster declarations—some dating back nearly 20 years.

As a result, aligning time frames for large infrastructure projects can be difficult, according to two grantees. One noted that FEMA projects for which it had budgeted CDBG-DR funds had 10-year implementation periods, compared with the 6-year CDBG-DR deadline. The other said that an HMGP project’s design phase, including the environmental review, could take several years, potentially delaying construction beyond the CDBG-DR or CDBG-MIT performance period.

Differing HUD and FEMA Program Requirements Can Also Create Challenges

Officials from HUD, all seven grantees, and six of the seven state emergency management agencies we interviewed said it is challenging to meet program requirements when combining HUD and FEMA funds. Virtually all of these officials noted that combining these funds is challenging because HUD has requirements that FEMA does not. (These HUD requirements are statutorily imposed by the Housing and Community Development Act and CDBG-DR congressional appropriations.) Specifically, officials cited HUD’s income, wage and labor, or environmental review requirements as challenging to meet when using CDBG-DR or CDBG-MIT funds for FEMA cost share. All but one grantee and one state emergency agency also noted that limited staff or program expertise further complicate compliance.

Income Requirements

Generally, grantees must use at least 70 percent of their total CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds to assist individuals with low and moderate incomes, a requirement that does not apply to FEMA funds.[45] One way that HUD defines an activity to principally benefit individuals with low and moderate incomes is if at least 51 percent of the population of the community or project beneficiaries are considered to have low and moderate incomes.[46] According to six of the seven grantees and five of the seven state emergency management agencies, this definition can be challenging to meet for large infrastructure projects because it is difficult to isolate the benefits specifically to individuals with low and moderate incomes.

In a January 2025 Federal Register notice—intended to standardize CDBG-DR requirements—HUD noted that large infrastructure projects may benefit many individuals with low and moderate incomes even if they do not meet the 51 percent threshold.[47] The notice stated that when a project serves a large area, the proportion of individuals with low and moderate incomes may fall below the required threshold. To address this circumstance, it introduced flexibilities to help newer grantees meet the requirement for such projects.[48] The notice does not apply to the $49.5 billion in CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds awarded for the disasters in our review period. However, it states that grantees not subject to the notice may ask HUD to approve an alternative requirement that incorporates this flexibility.

In addition, five of the seven grantees and five of the seven state emergency management agencies we interviewed said that timing differences between when HUD and FEMA funds become available make it more difficult to meet the income requirement. According to two grantees, it takes time to determine whether FEMA-assisted projects benefit individuals with low and moderate incomes, especially when those projects began or were completed before CDBG-DR or CDBG-MIT funds became available. These projects do not initially track income, which adds to the difficulty. Because making these determinations is burdensome, one grantee did not count projects that used CDBG-DR or CDBG-MIT funds for cost share toward meeting the overall 70 percent low- and moderate-income benefit requirement. Instead, the grantee relied on other projects that did not have a cost-share component to meet the requirement.

Wage and Labor Requirements

Federal law requires that grantees follow wage and labor standards—which establish how much and how often workers must be paid—when using CDBG-DR or CDBG-MIT funds for construction.[49] However, these requirements, known as Davis-Bacon Act requirements, do not apply to work performed under the Public Assistance program and HMGP.[50]

Communities may be reluctant to incorporate these requirements into their construction contracts if they are not mandatory, as doing so could increase project costs or deter contractors from bidding. Officials from one state emergency management agency said FEMA may not approve the extra cost associated with Davis-Bacon compliance. According to FEMA officials, FEMA will reimburse payroll rates reflected in the FEMA recipient’s official payroll policy in effect at the time of the disaster.[51] Officials from one grantee said even when local wage rates meet or exceed Davis-Bacon rates, contractors often find the associated paperwork burdensome.

Differences in the timing of when HUD and FEMA assistance becomes available further complicate compliance, according to representatives of HUD, six of the seven grantees, and two of the seven state emergency management agencies we interviewed. Specifically, construction work completed before CDBG-DR or CDBG-MIT funds become available may not have met wage and labor requirements because they were not yet in effect.

HUD noted that timing could be a challenge in implementing Davis-Bacon Act requirements. In April 2019 and May 2020, HUD asked the Department of Labor not to apply these wage requirements retroactively to selected CDBG-DR grants. For example, to avoid undue hardship to communities, HUD requested that these requirements not apply if all construction work was completed before HUD and the grantee signed a grant agreement.

In June 2020, the Department of Labor approved this request, stating that retroactively applying these requirements could delay or disrupt disaster recovery construction.[52] The approval applies to 2015–2019 CDBG-DR grants and all CDBG-MIT grants. In March 2025, Labor approved a similar HUD request for funds provided to respond to disasters that occurred from January 2020 through 2024.[53]

However, federal wage and labor requirements continue to apply to CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds used to meet the cost-share requirements of projects that were ongoing when or begun after HUD and the grantee signed a grant agreement. In addition, these HUD requests occur on an ad hoc basis and apply only to grants included in the request.

Environmental Reviews

FEMA and HUD each have statutory requirements for environmental reviews.[54] Since 2013, federal law has generally allowed CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT grantees to adopt FEMA’s environmental review for Stafford Act programs when using funds for cost-share requirements.[55] However, this is generally only permitted if the actions covered by an existing FEMA environmental review are substantially the same as the actions proposed for the CDBG-DR supplemental funds.

Until recently, grantees included in our review were required to conduct separate environmental reviews for projects funded under federal programs not authorized under the Stafford Act. Three of the seven grantees and six of the seven state emergency management agencies we interviewed indicated that this made it challenging to use HUD’s funds to meet the cost-share requirements of non-Stafford Act programs. In 2023, one grantee requested that HUD allow it to adopt FEMA’s environmental review for a non-Stafford Act program, stating that conducting a separate HUD review would be duplicative and delay the project by 4 to 6 months. According to HUD, it did not approve the request, citing a lack of authority under the grant’s appropriation to waive this requirement.

The Disaster Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2025 changed this by allowing grantees to adopt the environmental review conducted by any agency—not just those carried out under Stafford Act programs—when supplementing a project with CDBG-DR funds.[56] According to the act, this flexibility applies to all CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT grants. However, grantees may still be required to conduct a separate or supplemental HUD review if the project scope differs from that covered in the original review.

Officials from one state emergency management agency stated that FEMA’s environmental assessments are often not comprehensive enough to fully satisfy HUD’s broader environmental standards, which require supplemental analysis or documentation. Similarly, officials from another state emergency management agency told us that even minor deviations in scope can sometimes trigger a new environmental review.

Limited Capacity

Limited staffing or program expertise (capacity) made it challenging to comply with HUD requirements, according to six of the seven grantees and six of the seven state emergency management agencies we interviewed. They said this limitation created additional administrative burdens for grantees or their subrecipients.[57] Two grantees noted that identifying FEMA Public Assistance projects suitable for meeting HUD requirements was time-consuming. For example, one grantee said its staff had to review over 7,600 projects to determine which met HUD criteria. The other grantee said FEMA collects less documentation for projects below a certain dollar threshold than HUD requires, making it burdensome to evaluate those projects for compatibility.[58] As a result, the grantee chose not to use HUD funds for such projects.

Similarly, officials we interviewed for our November 2022 report stated that navigating differing requirements, time frames, and authorities across federal programs increased the need for resources and technical expertise to access disaster recovery assistance.[59]

However, HUD officials, five grantees, and five state emergency management agencies we interviewed said that despite these challenges, CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds were valuable in helping FEMA recipients complete projects. Without this support, many recipients might not have had the financial capacity to undertake this work, they said. This is consistent with findings from our November 2022 report, which found that states and localities often had insufficient financial capacity to cover FEMA cost-share requirements.[60]

Options Exist to Address Challenges to Using HUD Funds for Cost-Share Requirements, but Each Presents Trade-Offs or Limitations

To help address the challenges associated with using CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds to meet FEMA cost-share requirements, HUD officials, grantees, and state emergency management agencies we interviewed suggested two main types of options: (1) aligning FEMA and HUD program requirements or (2) eliminating cost-share requirements altogether. However, these options have trade-offs or limitations.

Align FEMA and HUD Program Requirements

Apply only FEMA requirements for cost-share contributions. All seven grantees and five of the seven state emergency management agencies we interviewed suggested that when CDBG-DR or CDBG-MIT funds are used solely for the cost-share portion of FEMA-funded projects, only FEMA requirements should apply. Five of these grantees and two state emergency management agencies noted that this would reduce administrative burden for the grantee or subrecipients. Similarly, FEMA and three state emergency management agencies stated that this option would reduce the complexity of using HUD funds for cost share. Applying only FEMA requirements could also reduce compliance challenges by eliminating the need to meet two sets of program rules. In addition, it could address timing issues—for example, by allowing HUD funds to be used more easily for FEMA projects already in progress.

However, applying only FEMA requirements may lead to use of HUD funds in ways that do not align with the CDBG program objectives. For example, cost-share expenditures may not meet the national objective of benefiting individuals with low and moderate incomes. According to HUD and FEMA, this option would require statutory changes to implement. For example, HUD officials noted that they do not currently have the authority to waive the Davis-Bacon wage requirements.

Expand flexibility for Public Assistance projects. Officials from five grantees and six state emergency management agencies we interviewed said FEMA should extend the flexibility currently available under HMGP to the Public Assistance program.

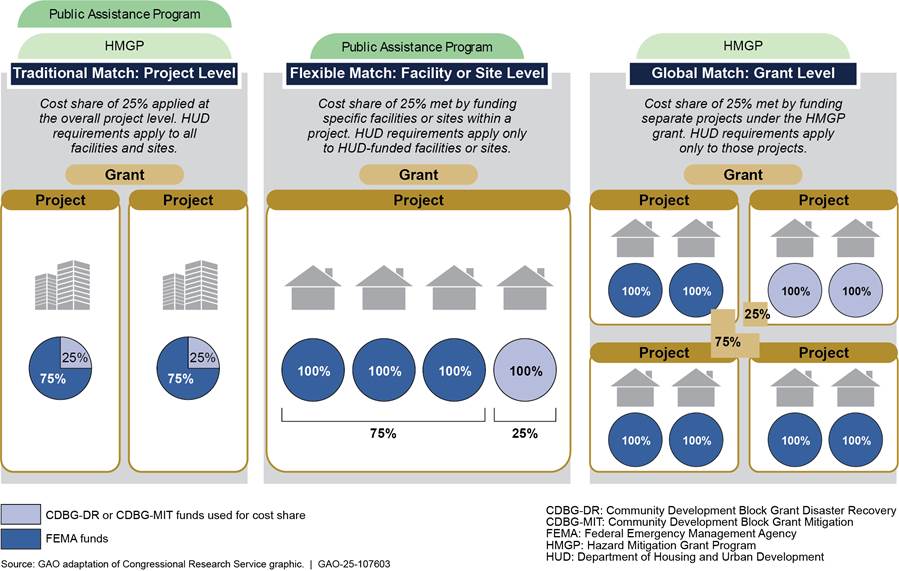

Traditionally, Public Assistance and HMGP recipients are required to provide up to 25 percent in cost share at the project level. When CDBG-DR or CDBG-MIT funds are used for cost share, both HUD and FEMA requirements apply to all facilities and sites within the project (see fig. 5).

Notes: Under all three approaches, FEMA requirements apply to all projects under a grant, including those used to meet the cost-share requirement. According to FEMA officials, Public Assistance recipients may combine traditional and flexible match approaches, and HMGP recipients may combine traditional and global match approaches to meet the cost share. The figure illustrates the standard 25 percent cost share, but for Public Assistance this may be reduced to 10 percent or waived entirely.

In October 2020, FEMA and HUD introduced a flexible match option for Public Assistance projects to give recipients flexibility on how to meet the cost-share requirement of up to 25 percent.[61] Under this option, the cost share is calculated at the project level, but recipients apply CDBG-DR or CDBG-MIT cost-share funds only to specific facilities or sites within a project. In those cases, only the HUD-funded facilities or sites must meet both HUD and FEMA requirements.

In contrast, HMGP recipients can elect the global match option, which allows them to meet the cost-share requirement at the grant level rather than at the individual project level. As a result, only the projects funded with CDBG-DR or CDBG-MIT funds need to comply with both HUD and FEMA requirements. One grantee we interviewed said this option allowed it to fund seven projects with CDBG-MIT to satisfy the full HMGP grant cost share.[62] This allowed the grantee to select projects aligned with HUD requirements and significantly reduce administrative costs.

None of the state emergency management agencies we interviewed had used the flexible match option. Officials from two grantees said this option did not address the challenge of having to meet both HUD and FEMA requirements at the project level.

FEMA officials said the agency had offered the maximum flexibility allowed under current law, and that allowing Public Assistance recipients to use the global match option may require statutory changes. According to FEMA, this option would provide additional flexibility to recipients. Currently, however, the Stafford Act and FEMA regulations require that the Public Assistance cost share be met at the project level rather than the grant level. Additionally, neither the flexible nor global match options addresses challenges related to the timing differences between HUD and FEMA assistance or the other challenges in meeting HUD requirements. Finally, officials from three state emergency management agencies said that tracking compliance under the global option could be challenging. For example, one noted that enhanced financial tracking and reporting would be required to ensure compliance.

Align periods of performance. Six grantees and six state emergency management agencies we interviewed said aligning HUD and FEMA periods of performance would help grantees use CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds to meet cost-share requirements. Specifically, two grantees and two state emergency management agencies said this option could help grantees manage delays in HUD funding availability or take advantage of FEMA-approved project extensions. Unless the period of performance is statutorily established, HUD can administratively establish it for CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds. For example, as previously discussed, HUD currently imposes a requirement that CDBG-DR funds be expended within 6 years of receipt.[63] Both HUD and FEMA can approve extensions to their respective periods of performance, suggesting they may have the administrative flexibility to better align them.

According to HUD, grantees can request an extension to better align with FEMA timelines, and HUD considers this a valid justification. FEMA stated that aligning periods of performance would improve consistency, but noted it may not always be feasible.

However, administratively aligning periods of performance could lead to longer delays in the expenditure of grant funds. Historically, we and others have raised questions about the long life cycle of FEMA, CDBG-DR, and CDBG-MIT funds.[64] Additionally, this option may be impractical because it would extend the performance period for the entire CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT grant even when only a small portion of the grant is being used for cost share. As previously discussed, only about 7 percent of CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds in our review were budgeted to meet cost-share requirements.

Eliminate Cost-Share Requirements

Given the reported challenges of using HUD funds to meet FEMA cost-share requirements, three grantees and four state emergency management agencies we interviewed suggested eliminating the cost-share requirement altogether. For example, one grantee noted that when the nonfederal share is ultimately covered by other federal funds, the requirement may no longer make sense. Eliminating it would allow FEMA to fully fund projects, removing the difficulties grantees face when applying CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds toward cost share. It could also benefit communities that lack the financial capacity to contribute nonfederal funds.

However, eliminating cost-share requirements completely would require statutory changes. In addition, cost-share requirements are intended to control federal spending and promote shared responsibility for disaster relief across all levels of government. A 2023 Congressional Research Service report noted this intent, and FEMA officials similarly told us that communities should have a financial stake in disaster relief.[65] Two grantees and three state emergency management agencies also opposed eliminating the cost-share requirement. For example, one state emergency management agency noted that without state and local participation, federal costs would increase. This would reduce the total number of projects FEMA could fund. The Congressional Research Service report also cited concerns that increasing the share of federal funding for recovery projects could weaken incentives for communities to invest in projects to mitigate against future disasters.

Broader Efforts to Improve the Federal Approach to Disaster Recovery Could Help Address Cost-Share Challenges

Our body of work on the overall federal approach to disaster recovery includes broad recommendations to Congress and relevant federal agencies on addressing the negative effects of fragmentation across federal recovery programs.[66] These broad recommendations also could help address challenges associated with using CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds to meet FEMA cost-share requirements.

In our November 2022 report on improving the federal government’s approach to disaster recovery, state and local officials we interviewed noted challenges similar to those described in this report.[67] Specifically, they cited difficulties navigating multiple federal recovery programs due to differing requirements and time frames. We identified several options for addressing these challenges and improving the federal approach to disaster recovery.[68] For example, one option we identified in our 2022 report for standardizing program requirements is to prioritize the requirements of the primary federal funding source over those of a secondary source.

As a result, we recommended that Congress consider establishing an independent commission to propose reforms to the federal government’s approach to disaster recovery.[69] We also recommended that HUD and FEMA take steps to better manage fragmentation across disaster recovery programs.[70]

In addition, in a March 2019 report on CDBG-DR, we recommended that Congress consider legislation establishing permanent statutory authority for a disaster assistance program that responds to unmet needs.[71] We stated that permanent authorization would help grantees better plan for how to use CDBG-DR funds in coordination with other disaster recovery funding. We reiterated this recommendation in our 2022 report, noting that implementing it could help standardize requirements across federal disaster recovery programs.

The difficulties in using CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds for FEMA cost share reflect challenges similar to those we identified in our November 2022 report. In that report, we attributed these challenges to fragmentation across federal recovery programs.[72] We concluded that past efforts to address disaster recovery challenges have largely focused on individual agencies or programs rather than taking a government-wide approach. Consequently, addressing our prior recommendations to Congress and relevant agencies to reduce fragmentation across federal recovery programs could also help resolve challenges associated with using CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds for FEMA cost share.

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to DHS and HUD for their review and comment. DHS and HUD provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretaries of Homeland Security and Housing and Urban Development, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at naamanej@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix II.

Sincerely,

Jill M. Naamane

Director, Financial Markets and Community Investment

This report examines (1) the portion of Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR) and Mitigation (CDBG-MIT) funds allocated to grantees for disasters from January 2017 through January 2023 that has been budgeted to meet cost-share requirements and (2) key challenges, if any, selected grantees faced in using these funds to meet cost-share requirements and options to address them.

We focused on disasters that occurred from January 2017 through January 2023 because they represented about 50 percent ($49.5 billion) of the $99.8 billion in CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds appropriated from 1993 through December 2022.[73] (Some of the funds appropriated in December 2022 were used for the January 2023 disasters.[74]) These were also the most recent disasters for which CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds had been appropriated when we began our review.

For both objectives, we reviewed relevant laws and Federal Register notices governing the CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds for the January 2017–January 2023 disasters. We also interviewed officials from the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

To address the first objective, we requested data from the 55 grantees that received the $49.5 billion in CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds on the portion they had budgeted and expended to meet the cost-share requirements of other federal disaster assistance programs. We requested these data from all 55 grantees directly because HUD does not require grantees to report data on the use of CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds for cost-share purposes.

Specifically, we reviewed the action plans developed by the 55 grantees to identify the grantees’ activities that allowed for the use of these funds to meet cost-share requirements.[75] Based on this review, we developed a questionnaire, customized for each grantee, to confirm the accuracy of the information we collected from their plans. As part of the questionnaire, we also requested information, as of December 31, 2024, on the (1) portion of CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds budgeted and expended to meet the cost-share requirements of other federal disaster assistance programs and (2) the names of those programs.

We conducted pretests with three grantees to check that (1) the questions were clear and unambiguous, (2) terminology was used correctly, (3) the questionnaire did not place an undue burden on respondents, (4) the information could feasibly be obtained, and (5) the questionnaire was comprehensive and unbiased. We selected the three grantees primarily to reflect a mix of total grant amounts and to ensure each had at least one activity that allowed for the use of funds to meet cost-share requirements.[76] We made changes to the questionnaire’s content and format after each of the three pretests, based on feedback received.

Of the 55 grantees we contacted via email, 54 responded to our questionnaire. We excluded two grantees—with two separate grants totaling $65.4 million—from our analysis because, at the time of our data collection, (1) one grantee did not have an approved action plan for its grant and (2) the other grantee was in the process of transitioning its grant to another state agency. One additional grantee, with two grants totaling $50.6 million, did not respond to our data request. As a result, our calculation of funds budgeted and expended to meet cost-share requirements was based on data from 52 grantees, which together received about $49.4 billion of the $49.5 billion allocated for the disasters included in our review.[77]

To assess the reliability of the grantee data, we reviewed each of the 52 questionnaires we received for obvious errors in accuracy and completeness and requested that grantees clarify or correct responses as needed. We also obtained information from grantees on (1) the source of the data, (2) whether the budgeted and expenditure figures provided were actual amounts or estimates, (3) any system edit checks or controls to help ensure the data were entered accurately, and (4) any concerns about the reliability of the figures provided. We found these data to be sufficiently reliable to report on the portion of CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds budgeted and expended to meet cost-share requirements, as of December 2024. We also found the data sufficiently reliable to identify the key federal disaster assistance programs for which these funds were budgeted to meet cost-share requirements.

To address the second objective, we reviewed October 2020 guidance jointly issued by HUD and the Department of Homeland Security on the use of CDBG-DR funds as cost share for the Public Assistance program.[78] We also reviewed FEMA’s policy guide on its Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP) and related guidance on its cost-share requirement.[79] We focused on the Public Assistance program and HMGP because these were the primary FEMA programs for which grantees budgeted funds for cost-share requirements.

In addition, we reviewed our prior reports and reports by HUD’s Office of Policy Development and Research, HUD’s Office of Inspector General, and the Congressional Research Service that addressed CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT challenges, as well as broader issues related to the federal approach to disaster recovery.

We also interviewed officials from seven grantees—California, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, Nebraska, Puerto Rico, and West Virginia—as well as state emergency management agencies in these states. To select this nongeneralizable sample, we first used the results of our action plan review to identify grantees with at least one activity that allowed use of CDBG-DR or CDBG-MIT funds to meet cost-share requirements of other federal programs. We then categorized these grantees as small, medium, or large based on the total allocation of grants that included such activities.[80] Each size category included nine grantees.

To ensure a range of experience with using CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds for cost-share purposes, we selected two small and medium grantees and three large grantees that met at least one of the following primary criteria:

· To include grantees with longer implementation timelines, we selected four that administered only grants for disasters occurring from 2017 through 2019.

· To assess whether challenges varied by grant age, we selected two grantees that administered both pre- and post-2020 disaster grants or managed multiple CDBG-DR grants.

· To ensure representation of both grant types, we selected three grantees that administered both CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT grants.

We placed greater weight on the disaster year of relevant grants to prioritize grantees with more historical experience using CDBG-DR or CDBG-MIT funds for cost-share requirements.

To ensure diversity among the selected grantees, we also required each to meet at least one of the following secondary criteria:

· The grantee was in the top half of its size category (small, medium, or large) to account for a larger share of CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds.

· The grantee’s action plan specifically cited the name of a FEMA or non-FEMA disaster assistance program for which funds were budgeted to meet the cost-share requirement, allowing us to determine whether challenges differ across federal disaster assistance programs.

We also selected grantees from different HUD-designated geographic regions to obtain geographic diversity.

We conducted site visits to Louisiana and Puerto Rico to interview officials and tour FEMA Public Assistance and HMGP projects for which CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds were budgeted to meet cost-share requirements. We selected these grantees for site visits because they had experience using HUD funds for this purpose. Specifically, they had implemented cost-share activities across different years, disaster types, and grant types. We also selected them because they were cited in our background research as notable examples related to our review. For the remaining five grantees and state emergency management agencies that coordinate with these grantees, we held virtual interviews.

During interviews with officials from the seven grantees—and the seven state emergency management agencies they coordinate with—we asked them to identify (1) key challenges in using CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds to meet cost-share requirements and (2) options for addressing those challenges. From their responses, we developed a preliminary list of key challenges and potential options.

If a grantee or state emergency management agency had not identified a challenge during our initial interview, we presented a list of additional challenges we had identified and asked whether they viewed each as relevant. We also shared the full list of potential options with all seven grantees and state emergency management agencies, asking whether they agreed with the options and to describe their advantages and disadvantages. All but one grantee responded to this request.

To determine how long after the disaster the grantees received CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT allocations—one of the challenges noted—we reviewed HUD notices and other sources. From these sources, we identified the dates for the disaster declarations, appropriations, and allocations for eight CDBG-DR and four CDBG-MIT grants that six of the seven grantees planned to use for cost share.[81] California, Louisiana, and Puerto Rico each received grants associated with more than one disaster declaration. To illustrate the funding timeline for these grants, we used the date of the first related declaration. Some grantees also received more than one grant for a single disaster declaration; these additional grants were not included in this analysis.

We conducted this performance audit from May 2024 to September 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

GAO Contact

Jill M. Naamane, naamanej@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Paige Smith (Assistant Director), Josephine Perez (Analyst in Charge), Meghana Acharya, Laura Gibbons, Daniel Horowitz, Jill Lacey, Marc Molino, and Jennifer Schwartz made key contributions to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]42 U.S.C. §§ 5121–5207.

[2]This total includes $312 billion in selected supplemental appropriations to federal agencies for disaster assistance and approximately $136 billion in annual appropriations to the Disaster Relief Fund for fiscal years 2015 through 2024. It does not include other annual appropriations to federal agencies for disaster assistance. Of the supplemental appropriations, $97 billion was included in supplemental appropriations acts enacted primarily in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, in December 2024, the Disaster Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2025, which was passed as part of the American Relief Act, 2025, appropriated approximately $110 billion in supplemental disaster assistance. Pub. L. No. 118-158, div. B, 138 Stat. 1722, 1726–61 (2024).

[3]42 U.S.C. § 5193(a); 44 C.F.R. §§ 206.47, 206.65, 206.432(c). For purposes of this report, we refer to the nonfederal cost share as cost share.

[4]Public Assistance is the largest disaster recovery grant program established under the Stafford Act, providing funds for disaster-related debris removal, emergency protective measures to protect life and property, and permanent repairs to damaged or destroyed infrastructure. HMGP is designed to support cost-effective hazard mitigation measures that substantially reduce the risk of, or increase resilience to, future damage, hardship, loss, or suffering in areas affected by a major disaster.

[5]42 U.S.C. § 5305.

[6]On Dec. 21, 2024, the Disaster Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2025 made available an additional $12.1 billion in CDBG-DR funds for major disasters that occurred in 2023 or 2024. On Jan. 16, 2025, HUD published a Federal Register notice allocating these funds to eligible communities, which had 90 days from that date to develop an action plan outlining how they planned to use the funds. These funds are not included in the $49.5 billion because, at the time of our analysis, eligible communities had not yet developed such plans. However, we do include three CDBG-DR grants totaling about $138 million that were allocated to three states for recovery from major disasters in 2023. HUD used remaining funds from the Disaster Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2023, passed on Dec. 29, 2022, to make these three grants. Pub. L. No. 117-328, div. N, tit. X, 136 Stat. 4459, 5224 (2022). This act provided $3 billion in CDBG-DR funds to major disasters that occurred in 2022 or later, until such funds were fully allocated.

[7]Other federal agencies administer programs with a cost-share requirement that CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds may be used to meet, including those administered by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the Environmental Protection Agency, and the Federal Highway Administration.

[8]GAO, Disaster Recovery: Actions Needed to Improve the Federal Approach, GAO‑23‑104956 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 15, 2022).

[9]Pub. L. No. 118-158, 138 Stat. 1722, 1754 (2024).

[10]The January 2023 disasters were the most recent for which CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds had been appropriated when we began our review. The funds appropriated for disasters that occurred from January 2017 through January 2023 accounted for about 50 percent of all CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funds appropriated for disasters through January 2023.

[11]We excluded two grants because one grantee did not have an approved action plan and the other was transitioning its grant to another state agency. A third grantee, which administered two grants, did not respond to our data request.

[12]See, for example, GAO, Disaster Recovery: Better Monitoring of Block Grant Funds Is Needed, GAO‑19‑232 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 25, 2019); GAO‑23‑104956; Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Inspector General, Opportunities Exist for CPD to Improve Collection of Disaster Recovery Grantee Data for Non-Federal Match Activities, 2025-FW-0801 (Fort Worth, TX: Feb. 28, 2025); and Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research, Housing Recovery and CDBG-DR: A Review of the Timing and Factors Associated with Housing Activities in HUD’s Community Development Block Grant for Disaster Recovery Program (Washington, D.C.: April 2019).

[13]The Stafford Act also authorizes the President to declare an emergency for any occasion or instance when the President determines federal assistance is needed. Emergency declarations supplement state, local, and tribal government efforts to provide emergency services, such as the protection of lives, property, public health, and safety, or to lessen or avert the threat of a catastrophe in any part of the United States.

[14]42 U.S.C. §§ 5170, 5191. Disaster response activities focus on short- and medium-term priorities like saving lives, protecting property and the environment, and providing for basic human needs after a disaster. Disaster recovery activities, on the other hand, encompass a range of short- and long-term efforts that contribute to rebuilding resilient communities equipped with the physical, social, cultural, economic, and natural infrastructure required to meet future needs.

[15]GAO, High-Risk Series: Heightened Attention Could Save Billions More and Improve Government Efficiency and Effectiveness, GAO‑25‑107743 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 25, 2025).

[16]The Disaster Relief Fund is the primary source of federal disaster assistance for state and local governments following a declared disaster. This fund is appropriated annually, allowing FEMA to fund, direct, coordinate, and manage response and recovery efforts associated with domestic disasters and emergencies. The appropriated funds usually do not expire at the end of a given fiscal year and remain available until expended, and Congress can provide supplemental appropriations to ensure sufficient resources for large or severe disasters.

[17]Public Assistance is also made available in response to emergency declarations. Under the Stafford Act, an emergency occurs when, in the President’s determination, federal assistance is needed to supplement state and local efforts and capabilities to save lives and to protect property and public health and safety, or to lessen or avert the threat of a catastrophe in any part of the United States. 42 U.S.C. § 5122(1). The President may declare an emergency exists after the governor of a state requests an emergency declaration. 42 U.S.C. § 5191(a).

[18]FEMA may provide Public Assistance for cost-effective hazard mitigation measures for facilities damaged by a disaster. To be eligible for Public Assistance funding, the mitigation measures must directly reduce the potential for future damage to the damaged portions of the facility. State and local governments may receive an increased federal cost share if they implement certain hazard mitigation-related measures.

[19]42 U.S.C. §§ 5170b(b), 5172(b)(1), and 5173(d) establish the minimum federal cost share for essential assistance, permanent work, and debris removal under the Public Assistance program. 44 C.F.R. § 206.47(b) recommends the President increase the maximum federal share to 90 percent when certain thresholds are met, and 44 C.F.R. § 206.47(d) recommends a federal cost share of up to 100 percent for emergency work and debris removal when warranted by the needs of the disaster for a limited period in the initial days of the disaster irrespective of the per capita impact.

[20]42 U.S.C. § 5170c.

[21]42 U.S.C. § 5170c(a); 44 C.F.R. § 206.432(c).

[22]The National Flood Insurance Program is intended to protect homeowners from flood losses, minimize the exposure of properties to flood damage, and alleviate taxpayers’ exposure to flood loss by offering federal flood insurance.

[23]The Housing and Community Development Act of 1974 authorized the CDBG program. See 42 U.S.C. § 5301.

[24]Section 105(a)(9) of title I of the Housing and Community Development Act of 1974, codified at 42 U.S.C. § 5305(a)(9), authorizes use of CDBG funds for “payment of the non-Federal share required in connection with a Federal grant-in-aid program undertaken as part of activities assisted” under title I of the act.

[25]Generally, according to Federal Register notices allocating CDBG-DR funds, HUD considers several factors when making the allocations to communities, including the extent of damage to homes and businesses, as well as contributions from insurance, FEMA grants, and Small Business Administration loans. This information helps HUD estimate unmet needs—that is, losses not covered by insurance or other forms of assistance.

[26]In the supplemental appropriation, Congress required that no less than $12 billion be allocated for mitigation activities. Pub. L. No. 115-123, 132 Stat. 63, 103–06 (2018). The Additional Supplemental Appropriations for Disaster Relief Act, 2019 appropriated $2.4 billion in CDBG-DR funds for major disasters that occurred in 2017–2019. Any remaining funds, after addressing unmet disaster needs, must be awarded for mitigation activities resulting from a major disaster that occurred in 2018. Pub. L. No. 116-20, 133 Stat. 871, 896–99 (2019). On Jan. 6, 2021, HUD awarded about $186.8 million in CDBG-MIT funds for 2018 disasters.

[27]For CDBG-MIT grants, mitigation activities are defined as those that increase resilience to disasters and reduce or eliminate the long-term risk of loss of life, injury, damage to and loss of property, and suffering and hardship by lessening the impact of future disasters.

[28]The Housing and Community Development Act of 1974, as amended, requires that each activity funded—except for program administration and planning—meet one of three national objectives: (1) benefit individuals with low and moderate incomes, (2) aid in the prevention or elimination of slums or blight, or (3) meet a need having a particular urgency. 42 U.S.C. §§ 5301(c), 5304(b)(3), 5305(c); 24 C.F.R. § 570.208.

[29]Unless the supplemental appropriation includes low- and moderate-income requirements, HUD has the flexibility to retain this requirement or reduce it through an alternative requirement or waiver outlined in a Federal Register notice governing CDBG-DR or CDBG-MIT funds.

[30]The Davis-Bacon Act requires the payment of locally prevailing wages and fringe benefits on federal contracts for construction. 40 U.S.C. §§ 3141–3148. In addition to the Davis-Bacon Act itself, other federal laws that authorize federal assistance for construction through grants, loans, and other methods and apply Davis-Bacon labor standards to federally assisted construction are Davis-Bacon “Related Acts.” The Housing and Community Development Act of 1974 is a “Related Act.” See 42 U.S.C. § 5310.

[31]29 C.F.R. § 5.5(a)(1)(i). Key information that contractors are required to document includes the name, address, and Social Security number of each worker; the hourly rates of wages paid (including rates of contributions or costs anticipated for bona fide fringe benefits or cash equivalents); the daily and weekly number of hours worked; the deductions taken out of gross wages; the actual wages paid; and a statement of compliance, which serves as a certification. 29 C.F.R. § 5.5(a)(3)(i)(B).

[32]See 42 U.S.C. § 4332. According to HUD, an environmental review is the process of reviewing a project and its potential environmental impacts to determine whether it meets federal, state, and local environmental standards.