DISASTER LOAN PROGRAM

Enhanced Procedures and Data Needed to Address Duplication of Benefits

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Courtney LaFountain at LaFountainC@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107608, a report to congressional committees

Enhanced Procedures and Data Needed to Address Duplication of Benefits

Why GAO Did This Study

Natural disasters cause billions of dollars in damage to U.S. communities each year. SBA’s Disaster Loan Program helps borrowers, including homeowners and businesses, rebuild or replace damaged property or continue business operations.

The Joint Explanatory Statement accompanying the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2024, includes a provision for GAO to examine duplication of benefits in SBA disaster assistance. This report examines (1) SBA policies and procedures for preventing, identifying, and resolving cases of duplicative benefits, and (2) SBA data on such cases and SBA efforts to resolve them.

GAO analyzed SBA disaster loan data from June 2020 through December 2023—the latest available data. GAO also reviewed related documentation from SBA and other federal agencies, and interviewed agency officials.

What GAO Recommends

GAO recommends that SBA (1) develop documented procedures for resolving cases of duplicative disaster benefits and (2) enhance the collection and accessibility of its data on these cases. SBA partially agreed with the first recommendation and agreed with the second. SBA stated that it would address both recommendations.

What GAO Found

Duplication of disaster benefits occurs when disaster survivors receive compensation from multiple sources—such as insurance and federal aid—that exceeds their total eligible losses. To prevent this, the Small Business Administration (SBA) requires borrowers to self-report any additional assistance they have received when applying for an SBA disaster loan. SBA uses the information to determine the maximum loan amount needed to cover eligible losses. SBA also contacts borrowers before each loan disbursement to check whether they have received any other potentially duplicative compensation, such as insurance payments or grants. If duplication of benefits is identified, SBA notifies borrowers of corrective actions they may take to resolve the issue.

SBA has identified cases of duplicative disaster assistance (see table), but SBA could not determine whether or how the duplication was resolved or how much over-disbursement was recovered in these cases. SBA is statutorily required to recover any duplicative benefits that it has provided to disaster assistance recipients when deemed in the government’s best interest. However, it does not have documented procedures outlining how its staff should ensure borrowers take corrective actions to fully resolve such cases. Establishing documented procedures could better ensure that SBA staff fully and appropriately resolve cases of duplication and identify recovered amounts.

|

Time period |

Loans with duplication |

|

June 2020–Sept. 2020 |

59 |

|

Oct. 2020–Sept. 2021 |

738 |

|

Oct. 2021–Sept. 2022 |

592 |

|

Oct. 2022–Sept. 2023 |

541 |

|

Oct. 2023–Dec. 2023 |

57 |

|

No date provided |

3 |

|

Total |

1,990 |

Source: GAO analysis of Small Business Administration (SBA) data. | GAO-25-107608

Notes: SBA could not provide data before June 2020 or after December 2023 due to tracking system transitions. For more details, see table 3 in GAO-25-107608.

Additionally, SBA’s ability to track these duplications is limited. SBA relies on borrower self-reporting and data-sharing with federal agencies to detect duplications. However, its data management systems cannot automatically retrieve detailed case data. As a result, staff must manually review text fields in individual loan records to verify the status of duplicative benefits, repayment actions, or adjustments made, leading to inconsistencies and inefficiencies. By enhancing data collection and accessibility, SBA could better monitor and address duplication of benefits involving disaster assistance, and thereby improve efficiency and help ensure recovery of duplicate funds. Enhanced data collection would also strengthen its ability to evaluate the effectiveness of its procedures.

Abbreviations

|

CDBG-DR |

Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery |

|

FEMA |

Federal Emergency Management Agency |

|

HUD |

Department of Housing and Urban Development |

|

SBA |

Small Business Administration |

|

Stafford Act |

Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

May 22, 2025

The Honorable Bill Hagerty

Chair

The Honorable Jack Reed

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Financial Services and General Government

Committee on Appropriations

United States Senate

The Honorable Dave Joyce

Chairman

The Honorable Steny Hoyer

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Financial Services and General Government

Committee on Appropriations

House of Representatives

From 2019 through 2024, the United States experienced 126 weather and climate disasters causing $1 billion or more in damage, with cumulative costs exceeding $679 billion.[1] Following a major disaster or emergency, affected homeowners and businesses may have access to various resources to aid response, recovery, and rebuilding. Among these, the Small Business Administration’s (SBA) Disaster Loan Program plays a critical role.

Although SBA’s primary mission is to support small businesses, its Disaster Loan Program extends low-interest loans to homeowners, renters, businesses and nonprofit organizations affected by declared disasters. Most of these loans go to individuals and households to help repair and replace homes and personal property. In fiscal year 2023, SBA approved almost $3 billion in loans to disaster survivors nationwide. This amount included over $670 million in loans to businesses and more than $2.3 billion to homeowners and renters.[2]

We previously reported on challenges in the federal approach to disaster recovery, which are partly due to fragmentation across multiple federal entities.[3] The array of disaster recovery assistance available to businesses and individuals can result in awarding funds that exceed the replacement cost of losses suffered, known as duplication of benefits. Under the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (Stafford Act), federal agencies must ensure that individuals, businesses, and other entities do not receive more assistance than necessary to cover their eligible disaster-related costs.

The Joint Explanatory Statement accompanying the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2024, includes a provision for GAO to review SBA’s handling of duplicative benefits in its Disaster Loan Program. This report examines (1) the extent to which SBA has policies and procedures for preventing, identifying, and resolving cases of duplicative benefits in its Disaster Loan Program, and (2) available data on cases of duplicative benefits identified by SBA for fiscal years 2020–2024 and SBA’s efforts to resolve them.

For the first objective, we reviewed SBA standard operating procedures and training materials on managing disaster loans. These included procedures for preventing and identifying duplication of benefits to applicants and recipients and for resolving them through loan adjustments or repayments. We also reviewed Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) documentation on the disaster assistance sequence of delivery to understand how SBA and FEMA coordinate to prevent duplication. Additionally, we reviewed memorandums of understanding and data-sharing agreements between SBA and other federal agencies, such as FEMA and the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). We compared SBA’s processes for preventing, identifying, and resolving duplicative benefits against Stafford Act requirements, relevant internal control standards, and selected principles for managing improper payments.[4]

We interviewed SBA officials about their processes for managing duplication of benefits for disaster loans and their coordination with FEMA and HUD. We also interviewed FEMA and HUD officials to understand their roles and interactions with SBA for preventing and resolving cases of duplicative benefits.

For the second objective, we requested data from SBA on loans that had begun disbursement and had at least one case of duplicative benefits identified by SBA for fiscal years 2019 through 2024.[5] SBA provided these data for June 2020 through December 2023, as this was the time frame for which the agency had such data.[6] We calculated the total number of loans that SBA identified with duplicative assistance. We also analyzed available data on the status of these cases, including whether they were resolved, and the timelines and costs for closing them. We analyzed the data on borrowers required to repay duplicative benefits, including the associated dollar amounts.[7]

Additionally, we compared SBA’s collection and use of data against relevant provisions of the Stafford Act as well as SBA’s most recent strategic plan to assess its effectiveness in addressing cases of duplicative disaster assistance. We also reviewed our prior work on key practices for performance management.[8] We did not independently verify whether SBA’s identified cases of duplication met the Stafford Act’s definition of duplicative benefits. Additionally, we did not assess whether additional cases of duplicative benefits existed that were not identified by SBA.

We conducted this performance audit from May 2024 to May 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Federal agencies can respond to a disaster when effective response and recovery are beyond the capabilities of affected state and local governments. The SBA Disaster Loan Program is activated through federal disaster declarations. Declarations can be issued by the President or the SBA Administrator if certain criteria are met.[9]

SBA’s Disaster Loan Program

SBA’s Disaster Loan Program, administered by its Office of Capital Access with the support and assistance of its Office of Disaster Recovery and Resilience, is designed to help homeowners, renters, businesses, and nonprofit organizations recover from physical damage and economic loss following a declared disaster. Eligibility is restricted to uninsured or otherwise uncompensated disaster losses. Disaster loans are generally categorized into three main types: home and personal property loans, business physical disaster loans, and economic injury disaster loans (see table 1).

|

Type of loan |

Eligible borrowers |

Lending limits |

Use of funds |

|

Home and personal property loans |

Homeowners and renters |

Up to $500,000

|

Replace or repair damaged or destroyed primary residences |

|

Up to $100,000 |

Replace or repair damaged or destroyed household and personal effects, including clothing, furniture, cars, and appliances

|

||

|

Up to $500,000

|

Eligible refinancing purposesa

|

||

|

20 percent of the verified loss, before deduction of compensation from other sources, up to $500,000

|

Post-disaster mitigation

|

||

|

Up to $500,000 |

Eligible malfeasanceb |

||

|

Business physical disaster loans |

Most types of businesses and nonprofit organizations regardless of size |

Up to $2 million |

Repair or replace property owned by the business, including leasehold improvements, machinery, and fixtures; refinance liens on damaged property; or implement mitigation measures to protect damaged or destroyed property from future disasters. |

|

Economic injury disaster loans |

Small businesses, small agricultural cooperatives and similar entities, and most private nonprofit organizations |

Up to $2 million of working capitalc |

Help meet financial obligations and operating expenses that cannot be met as a result of the disaster |

Source: GAO summary of Small Business Administration (SBA) information. | GAO‑25‑107608

aIf the loan applicant’s primary residence is totally destroyed or substantially damaged, as defined by regulation, and the applicant does not have credit elsewhere, SBA may allow that applicant to borrow money to refinance recorded liens or encumbrances on the residence.

bSBA may provide additional loan funds if the borrower suffered substantial economic damage or health/safety risks as a result of malfeasance in connection with the repair or replacement of real property. Malfeasance may include contractor malfeasance, such as nonperformance or substandard work.

cSBA regulations state that business disaster loans, including both physical and economic injury loans to the same borrower, together with its affiliates, cannot exceed the lesser of the uncompensated physical loss and economic injury or $2 million.

Other Federal Agencies Providing Disaster Assistance

In addition to SBA, several other federal agencies provide disaster assistance. FEMA is primarily responsible for coordinating disaster response and recovery. Other agencies—such as HUD and the Departments of Transportation, Health and Human Services, and the Interior—may also assist communities and individuals following a disaster. Among these, FEMA’s Individuals and Households Program and HUD’s Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR) offer financial assistance by providing disaster recovery funds similar to SBA’s Disaster Loan Program.[10]

FEMA’s Individuals and Households Program provides direct services and financial assistance for housing to individuals and households with uninsured or underinsured expenses and serious needs after a declared disaster. It also covers other essential needs, such as the repair or replacement of personal property and vehicles.

HUD’s CDBG-DR provides funds to communities for disaster relief, long-term recovery, restoration of infrastructure and housing, economic revitalization, and mitigation of unmet recovery needs. Eligible activities include repairing, rehabilitating, or rebuilding homes; reimbursing out-of-pocket expenses for home repairs; or constructing new homes for affected homeowners.[11] Unlike SBA’s Disaster Loan Program, CDBG-DR is not a permanently authorized program. Instead, Congress appropriates CDBG-DR funds through supplemental appropriations that HUD allocates to grantees. Additionally, rather than disbursing funds directly to recipients, HUD awards CDBG-DR grant funds to Tribes, states, and local governments, which then assist individuals, businesses, nonprofits, and local governments in their communities.[12]

The SBA, FEMA, and HUD disaster assistance programs differ in key ways (see table 2). SBA’s Disaster Loan Program provides low-interest loans directly to individuals, nonprofit organizations, and businesses to help them recover from physical and economic losses caused by disasters. These loans are intended to cover losses not fully compensated by insurance or other assistance. In contrast, FEMA’s Individuals and Households Program focuses on providing immediate financial relief for emergency needs, while HUD’s CDBG-DR funds are distributed to communities for long-term recovery and rebuilding, often months after a disaster.

|

Program |

Purpose |

Application period |

|

SBA’s Disaster Loan Program |

Provides low-interest loans for disaster recovery to individuals, nonprofit organizations, and businesses |

Applications generally due within 60 days of a disaster declaration for physical disaster loans and within 9 months for economic injury disaster loans |

|

FEMA’s Individuals and Households Program |

Offers immediate assistance for individuals and households for emergency disaster recovery needs |

Applications generally due within 60 days of a disaster declaration |

|

HUD’s Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery |

Funds long-term recovery and rebuilding efforts for communities |

HUD allocates funds to grantees after Congress appropriates funding through supplemental appropriations acts, which may occur months or years after a disaster declaration |

Source: GAO summary of information from the Small Business Administration (SBA), Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), and Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). | GAO‑25‑107608

Other federal agencies, such as the Departments of Transportation, Health and Human Services, and the Interior, also play a role in disaster recovery. Transportation assists in restoring transportation infrastructure, Health and Human Services offers medical and public health services, and Interior helps protect natural and cultural resources.

Duplication of Benefits

Duplication of benefits occurs when disaster survivors receive financial compensation from multiple sources for the same recovery purpose and the total amount received for that purpose exceeds the total eligible losses. Under the Stafford Act, federal agencies must ensure that individuals, businesses, and other entities do not receive more compensation than necessary to cover their eligible disaster-related costs.[13] Duplication of benefits can arise when different forms of financial compensation—such as insurance payments, federal aid, or charitable grants—are awarded for the same purpose.[14] Congress has allowed prohibitions against duplication of benefits to be waived under limited circumstances and for specific disasters.[15]

SBA’s statute, regulations, and procedures generally limit disaster loan eligibility to underinsured or uncompensated losses. Therefore, any insurance payments or other financial compensation not deducted from the total reported losses may be considered duplicative. However, SBA treats only compensation directly related to actual loss or damage to an eligible property as duplicative. For example, SBA does not consider assistance in the form of food vouchers or clothing to duplicate financial compensation addressing loss or damage to an eligible property.

SBA policies identify several types of financial compensation as potentially duplicative and requiring action to remedy, including the following:

· FEMA housing assistance provides funds for repairs or the replacement of an eligible residence, including permanent housing construction.

· FEMA Other Needs Assistance, a component of FEMA’s Individuals and Households Program, provides additional funds for nonhousing needs, such as transportation, childcare, and medical and dental expenses.

· Net insurance proceeds refer to any insurance settlements or payments an individual receives to cover damages.

· American Red Cross grants may provide funds for permanent repairs to an eligible property.

· Labor and materials from charitable third parties can include any volunteer labor or donated materials used in property repairs.

To prevent duplication of benefits, federal disaster programs coordinate to ensure that compensation from different sources does not overlap. For instance, after homeowners receive FEMA grants for emergency needs, SBA coordinates with FEMA to ensure that any disaster loans offered cover only remaining, unmet financial needs.

Section 312 of the Stafford Act places the responsibility on federal agencies to verify that no recipient is compensated more than once for the same loss. If duplication is identified after funds have been disbursed, recipients of duplicated federal benefits are liable to the United States for the amount of duplicative benefits received.

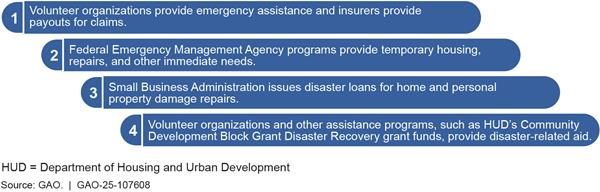

Sequence of Disaster Assistance Delivery

To ensure compliance with the Stafford Act, FEMA established a sequence of delivery for disaster assistance provided by federal agencies and organizations (see fig. 1). This sequence is intended to prevent duplication of benefits by outlining the order in which assistance should be provided. According to FEMA regulations, any agency or organization later in the sequence should ensure its assistance does not duplicate benefits already provided by earlier agencies. If this sequence is disrupted, the agency responsible for the disruption should take corrective action to resolve any duplication of benefits. SBA is responsible for identifying and addressing duplicative benefits from sources that precede it in the sequence.

Notes: 44 C.F.R. § 206.191. Volunteer organizations may provide emergency assistance and insurers may provide payouts for claims at any time during a disaster recovery. Federal Emergency Management Agency programs include housing assistance and Other Needs Assistance for other critical needs. The regulation revising the sequence of delivery became effective in March 2024. Individual Assistance Program Equity, 89 Fed. Reg. 3990, 4049 (Jan. 22, 2024). Before that, Small Business Administration assistance preceded some types of the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s Other Needs Assistance.

SBA’s position in the sequence of delivery makes it responsible for ensuring that its disaster loans do not overlap with compensation that borrowers have already received from sources such as insurance or FEMA. For example, if an individual has already received FEMA Individual Assistance, an SBA disaster loan may be considered duplicative if the total aid exceeds that individual’s uninsured losses.

Similarly, any disaster assistance provided after SBA loans in the delivery sequence, such as CDBG-DR funding, would also be considered duplicative if total assistance exceeds the recipient’s actual needs and exclusions do not apply.[16] In accordance with the sequence of delivery, CDBG-DR grantees are required to ensure that CDBG-DR funds do not duplicate SBA assistance provided for the same purpose.

SBA Does Not Have Procedures for Fully Resolving Identified Duplicative Benefits

SBA Requires Disaster Loan Applicants to Self-Report Compensation from Other Sources

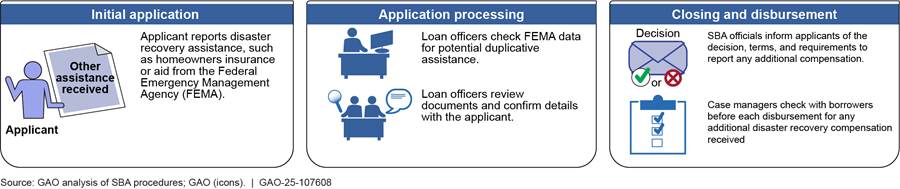

To prevent duplication of benefits, SBA loan officers review disaster loan applicants’ self-reported information and follow procedural steps to calculate an appropriate loan amount. Applicants are required to report all disaster-related assistance or compensation they have received for a given loss as part of their loan application.[17] SBA staff then review this information, along with applicants’ personal information and property damage assessments (see fig. 2).

Figure 2: Small Business Administration’s (SBA) Steps for Identifying Duplication of Benefits in the Disaster Loan Process

SBA procedures state that SBA loss verifiers should then estimate the applicant’s cost to repair or replace damaged property and contents. Loan officers must deduct any compensation the applicant received for damages from the total loss amount to determine the eligible loan amount.[18] Loan officers can verify the applicant’s insurance information through documentation submitted with the application; verbal contact with the insurer or applicant; or written communication such as emails, claim summaries, or an adjuster’s proof of losses. If relevant documentation is unavailable, loan officers are to rely on any amount disclosed by the applicant and deduct it from the eligible loss amount.[19]

After reviewing a loan application, SBA must inform the applicant of its pending loan approval or denial decision. At this time, SBA provides the proposed terms and conditions, including the requirement that borrowers promptly notify SBA and repay any insurance proceeds or other compensation that exceeds the approved loan amount and may constitute a duplication of benefits. Loan decisions are not final until the applicant receives written confirmation and agrees to the terms and conditions.

According to standard operating procedures, SBA disburses most disaster loans in stages after validating total losses and approving the loan. Before each disbursement, case managers must verify whether the borrower has received any additional insurance payouts, grants, or other compensation. To do this, they contact the borrower and confirm whether the borrower has received any new disaster-related compensation. Borrowers must notify SBA of any additional benefits or insurance proceeds that may constitute duplication. Additionally, if collateral is required and damaged property is used as collateral, borrowers must name SBA as mortgagee or loss payee on their insurance coverage.

SBA Has Data-Sharing Agreements with FEMA and HUD Grantees to Help Prevent Duplication of Benefits

SBA has agreements with FEMA and HUD’s CDBG-DR grantees to share data on disaster assistance recipients. SBA and FEMA have an agreement that allows real-time access to each agency’s assistance applicant data through a shared interface. These data include identifying information, financial benefits, and awards decisions. SBA officials said loan officers use this interface to identify applicants who have already received FEMA assistance and adjust eligible loan amounts before approving loans or disbursing funds.

Additionally, both SBA and FEMA have mechanisms in place to share relevant data—including applicants’ personally identifiable information—with tribal, local, state, and territorial governments and voluntary organizations.[20] These arrangements seek to further prevent duplication of benefits and facilitate additional disaster assistance for applicants.

SBA also offers voluntary memorandums of understanding with CDBG-DR grantees to share data on SBA disaster loan recipients.[21] Unlike the computer-matching agreement with FEMA, each CDBG-DR grantee must request such a memorandum to access SBA’s applicant-level disaster loan data, according to SBA officials. Once approved, SBA and grantees share reports based on an agreed upon time frame that meets grantees’ needs (e.g., weekly, biweekly, or monthly). SBA’s memorandums of understanding are valid for 18 months (unless parties agree to terminate sooner) and are renewable as needed.

SBA Does Not Have Written Procedures to Resolve Cases of Identified Duplicative Benefits After Notifying Borrowers

SBA generally has procedures for identifying and responding to duplicative benefits, but it does not have procedures for ensuring that borrowers take corrective actions to fully resolve identified duplication. Specifically, SBA’s procedures do not specify how staff should ensure that borrowers repay over-disbursed amounts or take alternative actions to address duplications (such as demonstrating additional eligible losses).

SBA’s standard operating procedures describe the steps SBA loan officers should take if they identify a duplication of benefits after a loan has been approved. A borrower may report receiving additional compensation after approval, or SBA may learn of it through one of its data-sharing agreements. If duplicative benefits are confirmed before disbursement begins, the borrower’s eligible loss amount decreases, and SBA must modify the loan amount.

If SBA has already disbursed funds to the borrower, it must determine the actions necessary to resolve the duplication. SBA officials told us that following an identified duplication SBA notifies the borrower of options for resolution, including (1) reducing the loan amount if funds remain undisbursed, (2) requesting reimbursement from the borrower’s disbursed funds for the amount of duplicated benefits, or (3) both. SBA officials noted that in cases of over-disbursement, the agency must send the borrower a letter requiring them to either repay the excess amount or submit documentation of additional disaster damages for SBA review. However, the procedures do not specify how staff should ensure that repayments are made or that alternative actions are taken to resolve the duplication.

SBA requires borrowers to take corrective actions to resolve a duplication of benefits in other circumstances as well. For example, if FEMA awards out-of-sequence Other Needs Assistance to an applicant who has already received SBA disaster disbursements, SBA procedures require the borrower to use loan proceeds to repay the duplicated amount to FEMA.[22] However, SBA does not have procedures for ensuring whether repayments occur or tracking other actions borrowers may take to address the duplication.[23]

We found that SBA documentation included examples of identified but unresolved cases of duplicative benefits. Disaster loan files undergo internal reviews to ensure compliance with procedures, according to SBA officials. SBA documentation of its reviews indicated that loan files did not consistently demonstrate that over-disbursements caused by duplication of benefits had been resolved. For instance, one review finding stated that a borrower reported a duplication of benefits, but no corrective action was recorded.

As discussed later in this report, SBA identified 1,990 loans with duplication of benefits from June 2020 through December 2023. SBA was unable to confirm the resolution of identified cases of duplication in part because it does not have procedures that specify what steps staff should take to record whether duplications were resolved.

The Stafford Act calls for federal agencies to recover any duplicative benefits that have been provided to disaster assistance recipients. Additionally, federal internal control standards state that management should implement control activities through policies. Such control activities can include documented procedures for achieving the agency’s objectives. By establishing documented procedures for staff to follow after notifying borrowers of a duplication of benefits––including recording any actions taken by the borrower––SBA could better ensure appropriate and consistent resolution of these cases.

SBA Identified Cases of Duplicative Benefits but Has Gaps in Its Ability to Track and Report Them

SBA Found Some Duplication of Benefits, Primarily from Private Insurance and FEMA

From June 2020 through December 2023, SBA identified 1,990 disaster loans with at least one instance of duplicative benefits (see table 3).[24] These cases involved borrowers who received financial assistance from other sources, such as private insurance or FEMA grants, that duplicated SBA loan funds. SBA identified these cases after initial loan disbursement using self-reported borrower information and data shared by other federal agencies, according to officials.

Table 3: SBA Disaster Loans with Identified Duplication by Date Duplication Was Identified and Date of Initial Disbursement, June 2020–Dec. 2023

|

Time period |

Loans with duplication identified during time perioda |

Loans initially disbursed during time period |

|

|

Number of loans |

Number of loans with duplication identified |

||

|

June 2020–Sept. 2020 |

59 |

985 |

70 |

|

Oct. 2020–Sept. 2021 |

738 |

25,143 |

766 |

|

Oct. 2021–Sept. 2022 |

592 |

30,621 |

593 |

|

Oct. 2022–Sept. 2023 |

541 |

27,675 |

524 |

|

Oct. 2023–Dec. 2023 |

57 |

5,293 |

33 |

|

No date provided |

3 |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Total |

1,990b |

89,717 |

1,986c |

Source: GAO analysis of Small Business Administration (SBA) data. | GAO‑25‑107608

Note: SBA data were not available before June 2020 or after December 2023 due to tracking system transitions.

aRepresents cases where SBA identified a duplication of benefits after initial disbursement and modified the loan accordingly. Loans are represented by the date duplication was initially identified.

bTwenty-eight loans with duplications spanning multiple fiscal years are represented only in the fiscal year of initial identification. Three cases did not have recorded identification dates.

cFour loans with duplication identified between June 2020 and December 2023 started disbursement before June 2020.

As previously discussed, if a case of duplication is identified after disbursement, SBA must determine the actions necessary to resolve the issue. According to SBA officials, this typically involves either reducing the loan amount or issuing an over-disbursement letter to the borrower. Each modification is assigned a unique tracking number to maintain a record of changes over time, according to officials. One borrower may have several modifications associated with their loan, which may correspond to one or more cases of duplication. As a result, the number of duplication-related modifications exceeds the number of affected loans. Specifically, SBA recorded 2,293 loan modifications across 1,990 loans with identified duplicative benefits.

SBA data indicate that private insurance and FEMA grants are the primary sources of duplication with SBA assistance (see table 4). Private insurance alone accounted for about 80 percent of identified cases, while FEMA grants alone accounted for about 6 percent. The remaining cases involved multiple sources, such as a combination of insurance, FEMA grants, local grants, and sales of damaged property and local grants. However, SBA could not provide the specific dollar amounts attributed to each source without manual reviews of individual electronic records, according to officials. Additionally, SBA officials said that other sources of duplication, such as CDBG-DR grants, may be recorded in loan files if recipients disclose them, but SBA could not determine the number of such cases without manually reviewing individual electronic records for this information.

Table 4: Sources of Identified Duplication with SBA Disaster Loans by Date Duplication Was Identified, June 2020–Dec. 2023

|

Time period |

Federal Emergency Management Agency |

Private insurance |

Other sourcesa |

|

June 2020–Sept. 2020 |

31 |

46 |

0 |

|

Oct. 2020–Sept. 2021 |

127 |

851 |

0 |

|

Oct. 2021–Sept. 2022 |

131 |

621 |

2 |

|

Oct. 2022–Sept. 2023 |

133 |

581 |

10 |

|

Oct. 2023–Dec. 2023 |

16 |

46 |

3 |

|

No date provided |

1 |

3 |

0 |

|

Total |

439 |

2,148 |

15 |

Source: GAO analysis of information provided by the Small Business Administration (SBA). | GAO‑25‑107608

Note: Duplication sources are represented by the date duplication was initially identified. SBA data were not available before June 2020 or after December 2023 due to tracking system transitions. The total number of duplication sources exceeds the number of cases SBA identified because some loans had duplications from a combination of multiple sources.

a“Other sources” include sales of damaged property, special assessments, and Department of Housing and Urban Development Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery grants.

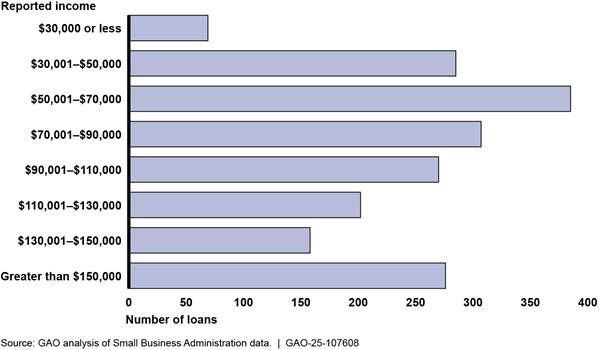

For disaster loans with identified duplication, borrower incomes exhibited a broad range (see fig. 3). SBA provided borrower income data for 1,952 home loans with identified duplicative benefits in fiscal years 2020–2024 but not for the 38 business loans during that period. According to the data, the median annual income of these borrowers was about $86,000.[25] SBA did not provide a breakdown of borrower income by category, such as tax filing status or household size.

Figure 3: Reported Household Borrower Income for Disaster Loans with Identified Duplicative Benefits Following Initial Disbursement, June 2020–Dec. 2023

Note: The data apply to home loans only; borrower income information was not available for the 38 business disaster loans during this period.

Data Tracking and Reporting Limitations Affect SBA’s Ability to Address Duplicative Benefits

SBA has significant limitations in its ability to track and report on duplicative benefits. SBA does not capture certain critical information in its data systems and captures other critical information only in narrative text fields, including some information on the resolution of duplication cases. According to SBA officials, information in these fields cannot be automatically queried, which requires staff to manually review the text fields in individual electronic records.

· Method of identifying duplications. SBA does not capture how each duplication case was identified in its data systems, such as through borrower self-reporting or data shared by other agencies.

· Status of identified cases. SBA does not know whether or how cases of duplication were resolved without manually reviewing individual electronic records for this information. For example, SBA does not have data on the number of cases requiring borrower repayments, the number of completed repayments, or the number of cases resolved by increasing the eligible loan amount to reflect additional disaster losses. Additionally, SBA does not have information available on cases where it applied a de minimis exception (for duplication of $1,000 or less) without conducting a manual review of text fields in individual records.

· Amount of assistance identified as duplicative. SBA collects the total reported amounts borrowers received from other sources but does not have information on the specific dollar amounts of assistance borrowers received that caused a duplication of benefits. SBA officials said that determining the specific duplicative portion would require manual file reviews.

· Source of duplication. SBA does not have information available on sources of duplication other than FEMA grants and private insurance without manual review of text fields in individual electronic records. For example, SBA does not know which duplication cases resulted from CDBG-DR grants without manual file reviews, according to officials.

Further, SBA cannot track duplication cases identified before June 2020, when it added a field to its data system to identify such cases. In fiscal year 2024, SBA implemented a new loan data system, but as of December 2024, officials stated the system had limited reporting capabilities and restricted data access.

SBA is required to report annual estimates of improper payments—including those due to duplication of benefits—for risk-susceptible programs under the Payment Integrity Information Act of 2019.[26] However, SBA’s Office of the Inspector General found that SBA’s fiscal year 2023 estimates of improper payments in the disaster loan program did not implement adequate sampling and estimation methodology plans to produce accurate estimates.[27]

SBA also has limited information on the length of time and costs associated with resolving duplication cases. The available data SBA provided indicate that it took an average of about 12 days to issue a letter notifying borrowers of an over-disbursement. However, SBA could not identify when borrowers completed repayment or when loan amounts were increased to reflect additional disaster losses. While SBA did not provide actual cost data for resolving duplication cases, it estimated that each loan modification incurred about $85 in administrative and operational costs (based on prorated staff salary costs for loan processing and review).

SBA’s strategic plan includes a strategic goal to implement strong resource stewardship, with an accompanying strategy to integrate robust data into its resource management and build and use quality data.[28] In addition, our prior work has identified that collecting information to measure progress and understand results can help federal officials manage and assess the effectiveness of their efforts.[29] For example, collecting and making data accessible for analysis can help determine whether goals are being met, such as information on instances of duplication that are occurring and if they are being effectively resolved.

Without readily accessible data on key factors such as repayment details and resolution status, SBA cannot ensure duplication cases are being resolved consistently and accurately, nor can it adequately assess the effectiveness of its procedures. By enhancing the collection and accessibility of its data on duplications of benefits, SBA would be better positioned to monitor and address this issue, thereby improving efficiency and helping to ensure recovery of duplicative funds. Additionally, enhanced data collection would strengthen SBA’s ability to evaluate the effectiveness of its procedures.

Conclusions

SBA’s Disaster Loan Program has played a key role in helping homeowners and businesses recover from disaster-related losses. SBA has taken some meaningful steps to manage cases of duplicative benefits, such as data-sharing with other federal agencies. However, it does not have documented procedures for how staff should resolve and record these cases following borrower contact. Developing such procedures would allow SBA to better ensure that cases of duplicative benefits are resolved appropriately and consistently.

Further, SBA tracks some loan and borrower data, but it lacks readily accessible information on several key factors, including whether identified duplications were repaid or otherwise resolved. SBA is unable to describe key information on its portfolio of disaster loans with duplicative benefits, such as how instances of duplication were identified and what actions loan officers have taken to resolve cases. SBA is also unable to describe other key information, such as the number of cases that have been fully resolved and the amount of duplicative benefits that borrowers have repaid, without labor-intensive manual file reviews. Without such information, SBA is constrained in its ability to monitor and address duplication of benefits. Enhanced data collection would also facilitate SBA’s ability to evaluate and improve its procedures for addressing these duplications.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following two recommendations to SBA:

The Administrator of SBA should ensure that the Associate Administrator for the Office of Capital Access develops documented procedures for resolving cases of duplicative benefits after a disaster loan has begun disbursement. (Recommendation 1)

The Administrator of SBA should ensure that the Associate Administrator for the Office of Capital Access enhances the collection and accessibility of data on cases of duplication of benefits in disaster loans and their resolution. (Recommendation 2)

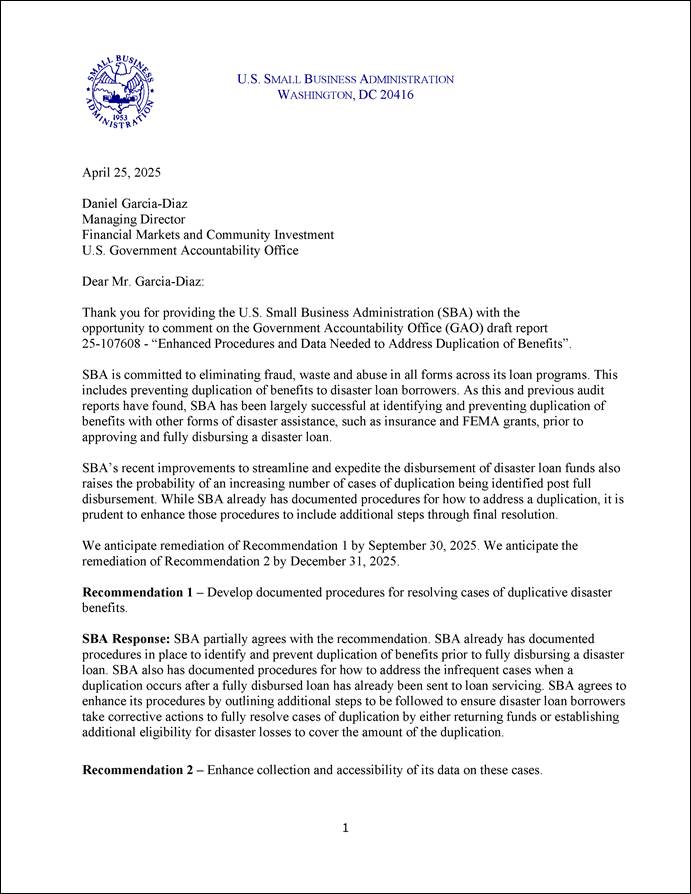

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to SBA, the Department of Homeland Security, and HUD for review and comment. They each provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

In its written comments, reproduced in appendix I, SBA agreed with our recommendation to enhance the collection and accessibility of data on cases of duplication of benefits and their resolution. SBA partially agreed with our recommendation to develop documented procedures for resolving cases of duplicative benefits after a disaster loan has begun disbursement. SBA stated that it has documented procedures to identify and prevent duplication of benefits prior to fully disbursing a disaster loan, as well as procedures to address cases that occur after a loan has been fully disbursed. SBA agreed to enhance its procedures to include steps to ensure borrowers take corrective actions to fully resolve cases by returning funds or establishing additional eligibility for disaster losses. As stated in our report, while SBA has general procedures for identifying and responding to duplicative benefits, it does not have procedures to ensure that borrowers have taken corrective actions.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Administrator of the Small Business Administration, and the Secretaries of Homeland Security and Housing and Urban Development. In addition, this report will be available at no charge on GAO’s website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at LaFountainC@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix II.

Courtney LaFountain

Acting Director, Financial Markets and Community Investment

GAO Contact

Courtney LaFountain, LaFountainC@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Kevin Averyt (Assistant Director), Jordan Anderson (Analyst in Charge), Garrett Hillyer, Daniel Horowitz, Jill Lacey, Marc Molino, Jared Smith, and Aida Woldu made key contributions to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]National Centers for Environmental Information, “Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters,” accessed January 8, 2025, https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/billions/summary-stats/US/2019-2024.

[2]U.S. Small Business Administration, Disaster Summary Report, accessed May 14, 2025, https://careports.sba.gov/views/DisasterSummary/Report.

[3]GAO, Disaster Recovery: Actions Needed to Improve the Federal Approach, GAO‑23‑104956 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 15, 2022). The most recent update to our High-Risk List added a new area needing attention by the executive branch and Congress on improving the delivery of federal disaster assistance. See GAO, High-Risk Series: Heightened Attention Could Save Billions More and Improve Government Efficiency and Effectiveness, GAO‑25‑107743 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 25, 2025).

[4]We determined that the control activities component of internal control was significant to this objective, along with the underlying principles that management should implement internal control activities through policies, such as the documentation of responsibilities. See GAO, A Framework for Managing Improper Payments in Emergency Assistance Programs, GAO‑23‑105876 (Washington, D.C.: July 13, 2023); and Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO‑14‑704G (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 10, 2014).

[5]The Joint Explanatory Statement to the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2024, includes a provision for us to submit a report that includes information on duplicative SBA disaster loans over the last 5 fiscal years.

[6]SBA could not provide data before June 2020 or after December 2023 due to tracking system transitions.

[7]To assess the reliability of the SBA disaster loan data, we reviewed related data documentation, interviewed and obtained written responses from SBA officials, performed electronic data tests, and reviewed the code SBA used to extract the data from its system. We determined the data fields related to cases and sources of duplicative benefits, and income of identified duplicative recipients were sufficiently reliable for reporting the numbers that SBA identified in its system. We determined that other data fields we requested were not sufficiently reliable for this report due to a large amount of missing data.

[8]GAO, Evidence-Based Policymaking: Practices to Help Manage and Assess the Results of Federal Efforts, GAO‑23‑105460 (Washington, D.C.: July 12, 2023).

[9]See 13 C.F.R. § 123.3. See also 42 U.S.C. § 5170 for further details on the criteria for issuing a major disaster declaration.

[10]Unlike SBA and FEMA Individuals and Households Program funds, CDBG-DR funds are not allocated directly to survivors but rather to CDBG-DR grantees, which may be Tribes, states, or local governments.

[11]Grantees may use these funds to carry out activities authorized under Title I of the Housing and Community Development Act of 1974, as amended, and HUD regulations, or as authorized by a waiver and alternative requirement. See Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery Universal Notice: Waivers and Additional Requirements. 90 Fed. Reg. 1754 (Jan. 8, 2025). See also 24 C.F.R. § 570.201. The Universal Notice describes the waivers and alternative requirements that HUD intends to implement with each allocation of CDBG-DR funding after a disaster declaration. Eligible activities include but are not limited to housing, economic revitalization, infrastructure, and public services. Housing may include but is not limited to new construction, reconstruction, rehabilitation, buyouts, and assistance payments.

[12]HUD allocates CDBG-DR funding according to supplemental appropriations acts, which typically provide funding for disaster relief, long-term recovery, restoration of infrastructure and housing, economic revitalization, and mitigation in the most impacted and distressed areas resulting from a qualifying major disaster. Generally, appropriations acts that provide CDBG-DR funds allow HUD to waive requirements or specify alternative requirements for any provision of any statute or regulation that HUD administers in connection with obligation by HUD of the funding. Historically, the appropriations acts specify that there are four types of requirements that HUD cannot waive under that authority: fair housing, nondiscrimination, wage and labor standards, and environmental protection.

[13]Specifically, the Stafford Act provides that the federal government must assure that no person, business, or other entity suffering losses as a result of a disaster receives assistance with respect to any part of such loss for which they received financial assistance under any other program or from insurance. 42 U.S.C § 5155(a). Section 7(b) of the Small Business Act provides that disaster loans are limited to loss, damage, or injury that is not compensated for by insurance or otherwise. 15 U.S.C. § 636(b).

[14]A federal agency may provide assistance to a person entitled to benefits for the same purposes from another source if the person has not yet received those benefits and if the person agrees to repay all duplicative assistance to the federal agency. 42 U.S.C. § 5155(b)(1).

[15]The Disaster Recovery Reform Act of 2018 provided that the President may waive the general prohibition on duplication of benefits if (1) the governor of a state requests a waiver and (2) the President finds such a waiver is in the public interest and will not result in waste, fraud, or abuse. Section 1210 of the Disaster Recovery Reform Act also changed the treatment of loans under the Stafford Act, so that when certain conditions are met, the loans are no longer a duplication of benefits. These provisions applied only to disasters declared between January 1, 2016, and December 31, 2021. Pub. L. No. 115-254, div. D, § 1210(a)(1), 132 Stat. 3186, 3442–43 (codified at 42 U.S.C. § 5155(b)(4)).

[16]FEMA regulations do not specifically mention HUD CDBG-DR. However, FEMA considers CDBG-DR assistance as “other governmental assistance” that follows SBA disaster loans in the delivery sequence. CDBG-DR appropriations acts generally require that CDBG-DR grantees have policies and procedures in place to prevent any duplication of benefits. The acts also generally specify that CDBG-DR funds may not be used for activities that may duplicate assistance received from FEMA or other sources.

[17]This reporting must include specific details about other disaster-related assistance or compensation, including homeowner’s or renter’s insurance policies and any flood, car, windstorm, or other insurance.

[18]SBA training materials state that compensation from other sources of $1,000 or less is considered de minimis and is not immediately deducted as a duplication of benefits or addressed through a loan modification. However, if additional duplication of benefits is identified and the loan is modified, loan officers must include the de minimis amounts back in the recalculated duplicative total.

[19]Borrowers are required to agree to assign any insurance proceeds received for disaster recovery to SBA. SBA training documents note that prior to February 17, 2023, borrowers and insurers were required to execute an assignment of insurance proceeds form that notified insurance companies that SBA should be the co-payee on recovery-related checks. SBA officials said that this practice was discontinued because many insurance companies refused to sign the agreement and SBA lacked a way to enforce it.

[20]According to FEMA regulations, voluntary organizations are tax-exempt organizations or groups which have provided or may provide needed services to the states, local governments or individuals in coping with an emergency or major disaster. FEMA notes that these organizations commonly offer shelter, food, clothing, childcare, financial assistance, and financial counseling, and conduct or coordinate debris removal, disaster cleanup, home repair, and reconstruction.

[21]Because CDBG-DR grants are another form of agency assistance provided later in the sequence of delivery, CDBG-DR grantees are responsible under the Stafford Act for preventing and remediating duplicative benefits with assistance from agencies or organizations such as SBA and FEMA. 42 U.S.C. § 5155(a). HUD requires CDBG-DR grantees to use the best, most recent available data from FEMA, SBA, insurers, and any other local, state, and federal sources of funding to prevent duplication of benefits prior to an award of CDBG-DR assistance. To support this effort, SBA offers the memorandums of understanding on data sharing to help CDBG-DR grantees manage potential duplication. Additionally, HUD and FEMA have a computer-matching agreement that permits grantees access to data on FEMA assistance recipients.

[22]SBA officials noted that FEMA may award Other Needs Assistance out of sequence in certain situations prior to SBA approval.

[23]As discussed earlier, HUD and its CDBG-DR grantees are primarily responsible for preventing and resolving duplication of benefits from those agencies earlier in the sequence of delivery, per FEMA regulations, because CDBG-DR grants are considered a form of other agency assistance delivered later in the sequence. However, SBA officials told us that if SBA learns of a duplication with CDBG-DR assistance, it may modify the loan amount to resolve the duplication. For example, SBA may reverify the borrower’s disaster losses to determine if they warrant a higher loan amount.

[24]SBA did not have data for loans with identified duplication prior to June 2020 or after December 2023 due to tracking systems transitions.

[25]Incomes in the top 25 percent were above $125,000 and incomes in the bottom 25 percent were below $58,000.

[26]An improper payment is defined by law as any payment that should not have been made or that was made in an incorrect amount (including overpayments and underpayments) under statutory, contractual, administrative, or other legally applicable requirements. It includes any payment to an ineligible recipient, any payment for an ineligible good or service, any duplicate payment, any payment for a good or service not received (except for such payments where authorized by law), and any payment that does not account for credit for applicable discounts. Under the Payment Integrity Information Act of 2019, each executive agency is charged with conducting improper payment risk assessments for each of their programs at least once every 3 fiscal years. The agency is to identify all programs with outlays exceeding $10 million that may be susceptible to significant improper payments. Significant improper payments are those that may have exceeded $10 million and 1.5 percent of program outlays; or $100 million. Pub. L. No. 116-117, 134 Stat. 113, 114–115 (2020) (codified at 31 U.S.C. § 3352(a)).

[27]Small Business Administration, Office of Inspector General, Independent Auditors’ Report on SBA’s Fiscal Year 2023 Compliance with the Payment Integrity Information Act of 2019, Report 24-16 (Washington, D.C.: May 15, 2024). GAO has ongoing work on SBA improper payments and recoveries.

[28]SBA, Strategic Plan: Fiscal Years 2022–2026 (Washington, D.C.).