FOOD SAFETY

USDA Should Take Additional Actions to Strengthen Oversight of Meat and Poultry

Report to Congressional Addressees

|

Reissued with update to addressees on Jan. 23, 2025 Revised January 23, 2025 to update the list of report addressees. |

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Steve Morris at (202) 512-3841 or MorrisS@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107613, a report to congressional addressees

USDA Should Take Additional Actions to Strengthen Oversight of Meat and Poultry

Why GAO Did This Study

The U.S. food supply is generally considered safe, but foodborne illness remains a common and costly public health problem. Each year, foodborne illnesses sicken one in six Americans, and thousands die, according to CDC’s most recent estimates. A July 2024 outbreak of Listeria monocytogenes made at least 61 people in 19 states sick and had caused 10 deaths, as of November 21, 2024. Improving federal oversight of food safety has been on GAO’s High Risk List since 2007.

In September 2014 and March 2018, GAO reported on USDA actions to reduce foodborne pathogens and challenges that FSIS faced. In the 2018 report, GAO found that FSIS implemented recommendations from the 2014 report but had not set pathogen standards for many widely available products.

This report provides an update on the status of USDA’s efforts. It examines (1) the extent to which FSIS has developed pathogen standards for meat and poultry products and (2) challenges FSIS faces in reducing food pathogens and steps it has taken to address them. GAO reviewed relevant laws, regulations, and USDA documents. GAO also interviewed agency officials and food safety and industry organizations and visited a FSIS laboratory.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making five recommendations, including that FSIS document its prioritization of pathogen standards and assess risks to human health from any gaps in its oversight and that FSIS and APHIS update their MOU or create a new agreement. FSIS neither agreed nor disagreed.

What GAO Found

Salmonella and Campylobacter are among the types of bacteria known to commonly cause foodborne illness in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). In 2018, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) designated Salmonella in “not ready-to-eat” breaded stuffed chicken products an “adulterant”—a poisonous or deleterious substance—if present at certain levels. However, since that time, FSIS has not finalized any new or updated standards for Campylobacter and other illness-causing pathogens in meat and poultry products. It paused work on several standards to focus on a framework of standards for Salmonella in raw poultry.

|

Proposed standard |

Year proposed |

Status |

Year last updated |

||

|

Salmonella in raw ground beef and beef trimmings |

2019 |

Paused |

1996 (when initial standard was set) |

|

|

|

Campylobacter in not ready-to-eat comminuted chicken |

2019 |

Paused |

2016 |

|

|

|

Campylobacter in not ready-to-eat comminuted turkey |

2019 |

Paused |

2011 (for carcasses) 2016 (for comminuted turkey) |

|

|

|

Salmonella in raw comminuted pork and pork cuts |

2022 |

Paused |

No previous standards |

|

|

|

Framework of standards for Salmonella in raw poultry |

2024 |

Ongoing |

2016 |

|

|

Source: Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) information. │ GAO-25-107613

Note: Comminuted meat and poultry has been cut, chopped, or ground into small particles. According to FSIS, the term “not ready-to-eat” means that the product is heat treated but not fully cooked and is not shelf stable.

Agency officials said that after finalizing the raw poultry Salmonella framework, FSIS plans to use a similar approach to developing the other standards. But they did not know when the framework would be finalized or have a prioritization plan or time frame for resuming work on the other standards. FSIS officials could not confirm that the agency had assessed whether focusing on this framework has caused gaps in its oversight of Salmonella in meat and Campylobacter in turkey products. By assessing any risks to human health that these gaps created and documenting how it is prioritizing its actions, FSIS will better understand the tradeoffs of its approach to reducing pathogens and associated illnesses.

FSIS faces two ongoing challenges to reducing food pathogens: (1) developing and updating standards, as described above, and (2) its limited control outside of the slaughter and processing plants it oversees. USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) has jurisdiction over farms, where animals can become contaminated with pathogens before they are sent to slaughter and processing. FSIS and APHIS’s 2014 memorandum of understanding (MOU) for coordinating responses to foodborne illness outbreaks does not identify or detail the agencies’ responsibilities in addressing and responding to specific pathogens that occur on farms and can subsequently enter plants. Updating their MOU, or developing a new agreement, will better position FSIS and APHIS to reduce pathogens in meat and poultry products.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

APHIS |

Animal and Plant Inspection Service |

|

CDC |

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

|

FDA |

Food and Drug Administration |

|

FY |

fiscal year |

|

FSIS |

Food Safety and Inspection Service |

|

MOU |

memorandum of understanding |

|

USDA |

U.S. Department of Agriculture |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

January 22, 2025

The Honorable John Boozman

Chairman

The Honorable Amy Klobuchar

Ranking Member

Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry

United States Senate

The Honorable Angie Craig

Ranking Member

Committee on Agriculture

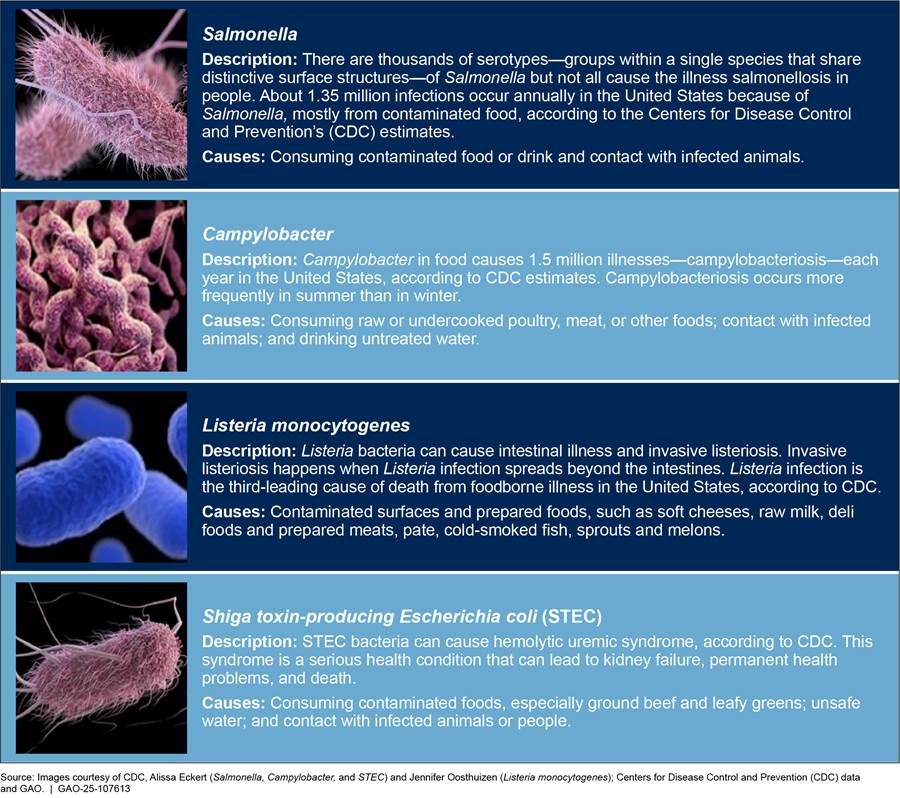

House of Representatives

Although the U.S. food supply is generally considered safe, one in six Americans get sick and 3,000 die from foodborne illness every year, according to estimates from the Department of Health and Human Services’ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).[1] In the United States, Salmonella, Campylobacter, Listeria monocytogenes (Listeria),[2] and Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) are among the leading bacterial causes of foodborne illnesses resulting in hospitalizations and death, according to CDC’s estimates.[3]

These pathogens are likely to exist in food products, including meat and poultry, regulated by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS). FSIS sets pathogen reduction performance standards (pathogen standards) for meat and poultry to verify whether plants have effective process controls to address pathogens. FSIS also makes adulterant determinations, which determine the level of pathogen that renders a product unsafe. An adulterant is a pathogen present on a product above a certain level that FSIS has determined unsafe, causing the product to be prohibited from sale.

USDA is responsible for ensuring the safety and wholesomeness of meat and poultry products that enter commerce, as provided by the Federal Meat Inspection Act and the Poultry Products Inspection Act.[4] Accordingly, USDA’s FSIS sets standards for the reduction of certain harmful bacteria and other disease-causing organisms known to cause foodborne illness—collectively referred to as pathogens—in certain meat (beef and pork) and poultry (chicken and turkey) products, among other products.[5] These pathogen standards apply at federally regulated processing and slaughter plants that produce meat and poultry products sold for human consumption.[6] FSIS conducts inspections at nearly 6,500 such plants nationwide, including testing samples of meat and poultry products for pathogens.

Federal oversight of food safety has been on our High Risk List of federal programs and operations that are vulnerable to waste, fraud, abuse, or mismanagement, or in need of transformation, since 2007.[7] In September 2014 and March 2018, we reported on actions FSIS took to reduce food pathogens and identified challenges the agency faced in doing so.[8] In our 2018 report, we found that USDA had implemented our recommendations from 2014 but had not set pathogen standards for many widely available products, such as ground pork, pork cuts, and turkey parts.

This report provides an update on the status of USDA’s efforts. We performed our work at the initiative of the Comptroller General to inform the 2025 update to our High Risk List. This report examines (1) the extent to which USDA has developed pathogen standards for meat and poultry products and (2) additional steps USDA has taken to address challenges we identified in 2014 and 2018 to reducing the level of pathogens, and new challenges the agency faces.

To examine the extent to which USDA has developed pathogen standards for meat and poultry products, we reviewed relevant laws and regulations, FSIS annual performance plans for fiscal years 2018 through 2023, recent FSIS strategic plans, FSIS annual foodborne illness outbreak investigation reports from fiscal years 2018 through 2023,[9] and relevant Federal Register notices on specific pathogen standards and adulterant determinations for meat and poultry products. We also reviewed FSIS documentation and interviewed FSIS headquarters officials on the agency’s plans to update existing pathogen standards and develop new standards and the processes to do so. We compared these plans and processes with our 2024 risk-informed decision-making framework and the Project Management Institute’s standards and leading practices for project management.[10]

To examine additional steps USDA has taken to address the challenges we identified in 2014 and 2018 to reducing the level of pathogens in meat and poultry, we also reviewed agency documentation and reports; Federal Register notices; and FSIS strategic plans, annual performance plans, related performance reports from fiscal years 2018 through 2024; and USDA and FSIS websites. We compared FSIS’s memorandum of understanding for collaboration with the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) with leading practices to enhance interagency collaboration.[11] We also reviewed FSIS’s guidance, directives, and regulations regarding inspection and sanitation best practices and requirements.

For both objectives, we interviewed agency officials and inspectors. Specifically, we interviewed FSIS headquarters officials on the status of FSIS’s efforts to update existing pathogen standards and develop new standards. We also interviewed FSIS food and consumer safety inspectors about how these standards impact their work. We discussed with both groups the existing challenges we identified in our prior reports and challenges identified since then that FSIS faces in reducing pathogens in meat and poultry products. We also conducted a site visit to FSIS’s Eastern Laboratory to learn about the agency’s current protocols for inspecting and conducting microbiological testing on meat, poultry, and processed egg products that FSIS regulates, and its other foodborne pathogen-related activities.

We also interviewed industry, consumer, and advisory stakeholders on the status of FSIS updates to or development of pathogen standards, as well as their perspectives on the challenges the agency faces to reduce pathogens in meat and poultry products. We identified a nongeneralizable sample of eight stakeholders: four representatives from national industry groups, three representatives from consumer advocacy groups, and one federal advisory committee. We selected these stakeholders because they are knowledgeable about FSIS’s food safety programs and provide a range of views on the topic. Perspectives from those we selected cannot be generalized to all stakeholders. Appendix I provides more information on our scope and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from June 2024 to January 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Pathogens

Of 31 pathogens known to cause foodborne illness in the United States,[12] FSIS focuses on four pathogens that commonly cause foodborne illness: Salmonella, Campylobacter, Listeria monocytogenes, and STEC (see fig. 1).[13]

Adulterant Designations and Pathogen Standards

To reduce incidences of foodborne illness in meat and poultry products, FSIS has made adulterant determinations and established pathogen standards for certain products. Adulterant determinations and pathogen standards are based on the pathogen-product pair, not just the pathogen. For example, Listeria monocytogenes is an adulterant in ready-to-eat products but not in raw products, and Salmonella pathogen standards differ among poultry products based on the type of product.

· FSIS has determined that products containing certain levels and serotypes of pathogens are “adulterated” under the Federal Meat Inspection or Poultry Product Inspection Acts.[14] An adulterant determination means that the adulterated product cannot be sold in commerce.[15] Examples of adulterants include Listeria monocytogenes and Salmonella in ready-to-eat products and STEC in raw nonintact beef products.

· To control the spread of foodborne pathogens not ordinarily considered adulterants, FSIS sets pathogen standards, which allow plants to have a certain number of positive sample results for these pathogens over time. When a plant exceeds the maximum number of allowable positive results, FSIS verifies whether the plant has taken appropriate steps—such as sanitation, testing, and prevention practices—to reduce the occurrence of the pathogen. Pathogen standards typically apply to Salmonella, and sometimes Campylobacter, in certain meat and poultry products.[16]

Operational Changes and Guidance

FSIS announces operational changes—changes to the agency’s operational procedures—to its inspectors through FSIS notices and directives.[17] Notices include time-sensitive instructions to inspectors to support workplace policies and procedures. Directives generally clarify inspection procedures and provide official communications and instructions to agency personnel.

FSIS also issues guidance on sanitation, pathogen controls, and best practices to industry to help meat and poultry plants maintain sanitary conditions to prevent foodborne illness and control pathogen levels. For example, FSIS’s Sanitation Performance Standards Compliance Guide states that surfaces that come into contact with food must not have any open seams, cracks, or chips, and must be cleaned and sanitized as often as necessary to prevent products from becoming contaminated.[18]

Inspections

FSIS inspects and regulates the U.S. production of meat and poultry products to assess, among other things, compliance with the agency’s established pathogen standards. As part of this effort, FSIS carries out inspections to ensure that meat and poultry prepared for human consumption are wholesome, not adulterated, and properly marked, labeled, and packaged.

In 2014 and 2018, we reported that to improve its food safety approach, FSIS had moved to an increasingly science-based, data-driven, risk-based approach by adopting the Pathogen Reduction; Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point regulations in 1996.[19] Under this approach, plants identify food safety hazards that are reasonably likely to occur and establish controls that prevent or reduce these hazards in their processes. FSIS inspectors routinely check records to verify plants’ compliance with those plans and observe their operations. Figure 2 shows the types of FSIS food safety positions and their roles.

Figure 2: Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) Food Safety Positions in Regulated Plants and Their Roles in Preventing Foodborne Illness

Note: We interviewed FSIS inspectors, scientists, compliance investigators, and veterinarians. According to FSIS’s website, other positions include administrative and professional positions. We use “plants” to refer to meat and poultry slaughter and processing plants that are under FSIS’s jurisdiction.

While FSIS inspects meat and poultry products nationwide, states with programs that are “at least equal to” the federal program can conduct their own inspections of meat and poultry plants.[20]

Coordination

FSIS coordinates with numerous federal agencies, state agencies, and local entities to help ensure the safety of meat and poultry products from the farm to the consumer, known as the farm-to-table continuum.[21] Table 1 shows examples of the purposes for which FSIS coordinates with various entities.

|

Agencies and entities |

Purpose |

|

USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service |

To share information when investigating foodborne illnesses and outbreaks.a |

|

Department of Health and Human Services’ Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) |

Through the Interagency Food Safety Analytics Collaboration, to, among other things, identify which foods are the most important sources of selected major foodborne illnesses.b |

|

CDC and state health departments |

To respond to foodborne illness outbreaks, including identifying the pathogen, product, and where the product became contaminated along the farm-to-table continuum. |

Source: U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) information. | GAO‑25‑107613

aAccording to CDC’s website, when two or more people get the same illness from the same contaminated food or drink, the event is called a foodborne outbreak.

bFSIS is responsible for the safety of meat, poultry, catfish (Siluriformes), and processed egg products. FDA is responsible for virtually all other food.

USDA Has Not Prioritized Developing and Updating Pathogen Standards Except for Salmonella in Poultry

Since our 2018 report, FSIS has designated an additional adulterant and made some operational changes but has not finalized any updated or new pathogen standards for meat and poultry products. Additionally, while the agency has proposed several new or revised pathogen standards since 2018, none of these standards have been finalized or put into effect. The agency paused its work on proposed standards for Salmonella in meat and Campylobacter in poultry to focus on a proposed framework of standards for addressing Salmonella in raw poultry. This framework was undergoing public notice and comment as of early January 2025. FSIS has focused exclusively on its 2024 proposed framework of standards and adulterant determinations to address Salmonella in raw poultry products, and pausing development of other standards due to limited resources and has not assessed whether this shift in focus has caused any gaps in oversight. Outbreaks continue to occur that involve products for which FSIS has not updated or developed pathogen standards since 2018 or earlier.

FSIS Designated an Additional Adulterant but Has Not Finalized New or Updated Pathogen Standards Since 2018

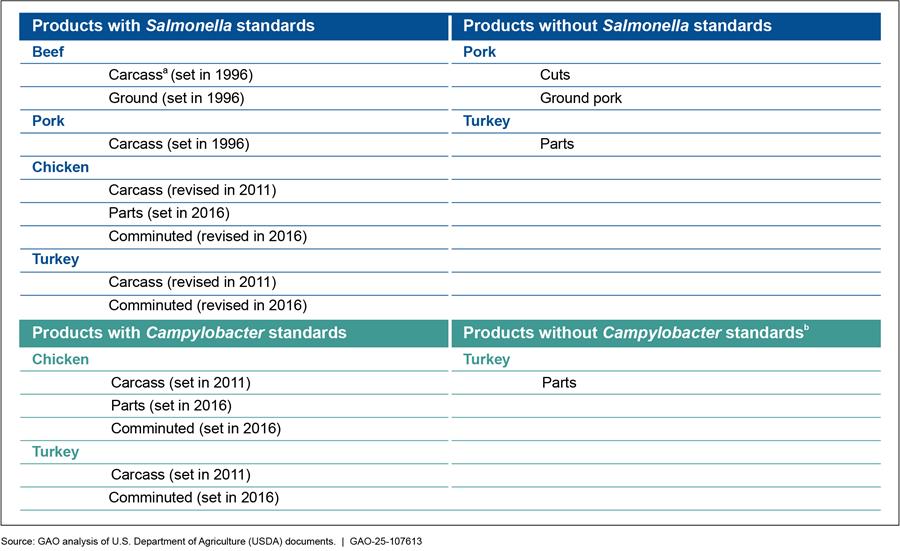

In 2018, we found that FSIS had developed pathogen standards for certain products but not for other commonly available products, such as pork cuts (e.g., pork chops), turkey parts (e.g., turkey breasts), and ground pork.[22] Since our 2018 report, FSIS has determined that Salmonella in “not ready-to-eat” breaded stuffed chicken products is an adulterant when present at certain levels, but it has not updated existing pathogen standards or finalized any new standards for other meat and poultry products.[23] For example, as of January 2025, FSIS had not finalized pathogen standards for Salmonella in pork cuts, ground pork, and turkey parts or for Campylobacter in turkey parts.[24] As a result, some pathogen standards (e.g., Salmonella in ground beef) have not been updated since 1996, and other products continue to have no pathogen standards (see fig. 3).

Figure 3: Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) Pathogen Standards for Poultry and Meat, as of January 2025

Notes: Ground pork is a type of comminuted (i.e., cut, chopped, or ground in small particles) product that also includes sausage and patties. Comminuted chicken and turkey include ground and deboned products. Chicken and turkey parts include breasts, legs, and wings.

Pathogen reduction performance standards (pathogen standards) set in 1996 are expressed as a prevalence level, that is, the proportion of a product that would test positive for a pathogen if the entire population of that product was sampled and analyzed during a specific period. Pathogen standards set or revised in 2011 or 2016 are calculated as the percentage of samples with detectable levels of pathogens from a specified set of samples, which varies by pathogen standard.

aUSDA has separate pathogen standards for cows/bulls and steers/heifers.

bAccording to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Campylobacter outbreaks are not commonly reported, but the frequency has generally increased since 1998. Many Campylobacter infections are not diagnosed or reported and are not part of recognized outbreaks. Campylobacter can live in the intestines, liver, and other organs of many animals—such as chickens and cows—without the animals becoming sick.

Food safety consumer groups we interviewed expressed concerns that outdated or nonexistent pathogen standards could contribute to more human foodborne illnesses. For example, some consumer safety representatives said the absence of standards could hinder FSIS’s ability to reduce the occurrence of pathogens. Specifically, according to these representatives, the absence of standards leaves establishments without clear direction and FSIS without objective criteria to assess performance. As a result, one group said the potential for pathogens to reach consumers and cause illness can worsen over time.

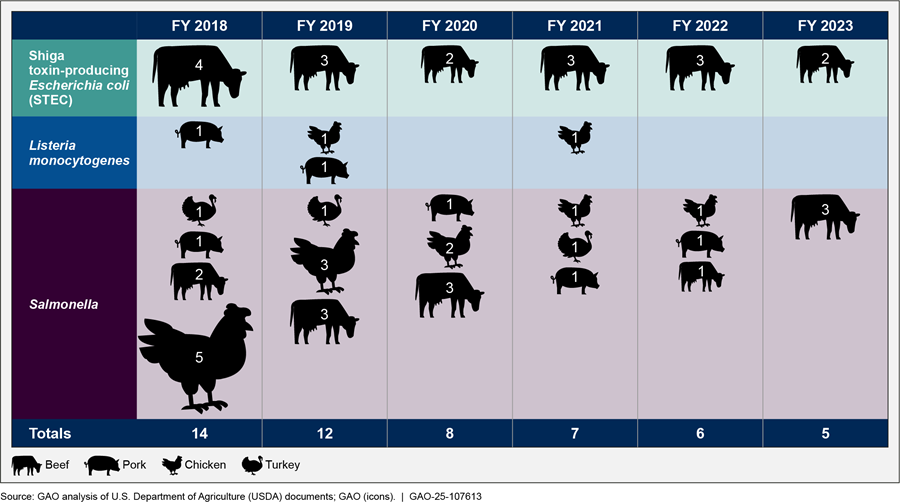

Foodborne illness outbreaks have continued to occur since 2018, including outbreaks related to products for which FSIS has not finalized updated or new standards, such as Salmonella in beef products. For example, beef was identified as the product of interest for 29 of 52 outbreaks involving pathogens such as Salmonella, Listeria monocytogenes, and STEC, according to FSIS Foodborne Illness Outbreak Investigations reports for fiscal years 2018 through 2023. According to the reports, which do not record related deaths, these outbreaks and others resulted in 3,220 infections and more than 845 hospitalizations (see fig. 4).[25]

Figure 4: Characteristics and Numbers of Foodborne Illness Outbreaks Investigated by USDA’s Food Safety Inspection Service (FSIS), Fiscal Years (FY) 2018 through 2023

Notes: FSIS conducts foodborne illness investigations in response to situations in which an FSIS-regulated product may be associated with human illness. According to FSIS Foodborne Illness Outbreak Investigations data for fiscal years 2018 through 2023, FSIS investigated a total of 52 outbreaks involving the above pathogens in meat and poultry products. These pathogens included Salmonella (31 outbreaks), Listeria monocytogenes (four outbreaks), and STEC (17 outbreaks). A foodborne outbreak occurs when two or more persons experience a similar illness after ingestion of a common food, and epidemiologic analysis implicates the food as the source of the illness. FSIS investigated these outbreaks in coordination with local, state, and federal public health partners. These products were investigated by FSIS as possible, likely, or confirmed cause of illnesses during the investigations. FSIS’s Foodborne Illness Outbreak Investigations data also include information about non-FSIS regulated products, products that include multiple ingredients, and multiple products (in which a single food was not identified). In addition to the pathogens listed in the figure, the agency investigated other pathogens such as clostridium botulinum and outbreaks involving multiple pathogens.

According to a 2016 Federal Register notice, FSIS reviews its standards on at least a 5-year basis, and its decision on whether to revise a performance standard is based in part on the standard’s potential contribution to reducing pathogen prevalence.[26] One recent example is the proposed framework for Salmonella in raw poultry.[27] According to the proposed rule for the framework that FSIS published in August 2024, FSIS decided on this approach because the current pathogen standards did not have an observable impact on human illness rates, even though they were reducing the prevalence of Salmonella in poultry products.[28]

Similarly, in May 2024, FSIS designated Salmonella in “not ready-to-eat” breaded stuffed chicken products as an adulterant when present at certain levels. In the final determination, FSIS noted that “not ready-to-eat” breaded stuffed chicken products were associated with 14 Salmonella outbreaks between 1998 and 2021, resulting in 195 reported illnesses and 41 reported hospitalizations.[29]

FSIS Made Some Operational Changes to Existing Pathogen Standards and Took Other Steps to Reduce Pathogens

Since 2018, FSIS has announced some operational changes to its pathogen reduction efforts for Salmonella in poultry products through FSIS notices (see table 2). Outside of setting pathogen standards and designating adulterants, FSIS uses notices and directives to announce operational changes to adjust its processes and procedures. As discussed earlier, FSIS directives and notices provide a means of clarifying procedures or providing time-sensitive instructions to inspectors and other agency personnel.[30] In addition to directives and notices, FSIS announces some operational changes through Federal Register notices and constituent updates, which are similar to press releases.

Table 2: Examples of Operational Changes FSIS Has Made Since 2018 to Reduce the Prevalence of Salmonella in Poultry Products

|

Categorizing plants |

In a 2018 Federal Register notice and request for comments, FSIS announced revisions to its operational procedures for categorizing slaughter and processing plants (plants) that produce raw poultry products and are required to follow pathogen standards for Salmonella in raw poultry.a In a related July 2019 constituent update (i.e., press release), FSIS announced scheduling changes to ensure that plants producing more than 1,000 pounds per day are consistently categorized on a weekly basis concerning achievement of the standard.b |

|

Vaccines as a preharvest intervention |

To remove barriers to use of vaccines as preharvest intervention to control Salmonella in poultry, FSIS announced in a March 2024 constituent update that it intended to exclude current commercial vaccine subtypes confirmed in raw poultry samples from the calculation used to categorize plants under the pathogen standards for Salmonella in raw poultry.c |

Source: Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS). │ GAO‑25‑107613

a83 Fed. Reg. 56,046 (Nov. 9, 2018).

bSpecifically, FSIS categorizes plants according to the following scale: category 1 – achieved 50 percent or less of the standard; category 2 – met the standard but had results greater than 50 percent of the standard; category 3 – exceeded more positive samples than allowed in the standard; or uncategorized – insufficient number of samples collected and tested.

cIn October 2021, the U.S. Department of Agriculture announced it would start a more comprehensive effort to reduce Salmonella in poultry products through identifying ways to incentivize the use of preharvest controls to reduce Salmonella contamination entering slaughterhouses. In November 2021, the agency held listening sessions with industry and consumer groups to answer questions about the establishment of pilot projects. Between March 2023 and March 2024, FSIS granted pilot projects to nine poultry slaughter and processing plants to examine the exclusion of Salmonella poultry vaccine strains from the FSIS Salmonella performance categorization.

|

Listeria monocytogenes (Listeria) Outbreak in 2024 According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in July 2024, ready-to-eat meats sliced at delis, including Boar’s Head brand liverwurst, were contaminated with Listeria. The contaminated products were associated with a 19-state Listeria outbreak resulting in 61 cases of illness and hospitalizations and 10 deaths. According to CDC’s website, when two or more people get the same illness from the same contaminated food or drink, the event is called a foodborne outbreak. The U.S. Department of Agriculture Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) worked with CDC and state public health partners to investigate the outbreak.

In July 2024, the Boar’s Head company recalled approximately 7 million pounds of deli meats adulterated with Listeria from the Boar’s Head plant in Jarratt, Virginia. In addition, the company recalled additional deli meats that were produced on the same food line and day as the liverwurst products. Because the plant fell under a Talmadge-Aiken Cooperative Inspection Agreement, products there were inspected and passed by state employees. According to CDC, Listeria spreads easily among deli equipment, surfaces, hands, and food. Refrigeration does not kill Listeria, but reheating to a high enough temperature before eating will kill any pathogens that may be on these meats. Source: GAO summary of FSIS and CDC outbreak information;

EvgenyTkachev/stock.adobe.com. |

In addition to operational changes to address Salmonella in poultry products, FSIS issued industry guidance from September 2019 through June 2024 for addressing Salmonella, Campylobacter, Listeria monocytogenes, and STEC in meat and poultry products.[31] The guidance covered issues related to education, training, and best practice recommendations for regulated plants. For example, FSIS issued guidance that outlined specific processes and described steps for plants to use in designing their sanitation plans to prevent foodborne illness. According to FSIS, sanitation is a major factor in preventing foodborne illness and controlling pathogens levels within plants.

FSIS officials acknowledged recent outbreaks of foodborne illness and the need to make changes to ensure plants were effectively addressing the pathogens. These officials said that operational changes provide a measure of administrative oversight in the interim.

USDA Has Not Prioritized Which Proposed Pathogen Standards to Address After It Finalizes a New Framework for Salmonella in Raw Poultry

FSIS had proposed standards for a range of meat and poultry products but paused its work on these standards to focus exclusively on its 2024 proposed framework of standards and adulterant determinations to address Salmonella in raw poultry products. In 2018, we reported that FSIS was taking steps that could lead to new pathogen standards for a range of products such as comminuted (i.e., cut, chopped, or ground in small particles) pork products, which includes ground pork.[32]

Since then, FSIS has expended resources to develop several proposed standards, including by publishing risk assessments on public health effects of the proposed pathogen standards and holding public comment periods and public meetings. FSIS decided to pause its work on most of these proposed standards to focus on developing a framework of standards for Salmonella in poultry, according to agency officials. FSIS continues to test raw products for which it has pathogen standards but does not assess the samples against a performance standard, agency officials said. According to these officials, it would not be an efficient use of resources to move forward with the current approach and finalize the proposed standards, if a new approach (i.e., the Salmonella in raw poultry framework) might be more effective in reducing foodborne illnesses associated with FSIS-regulated products. Table 3 shows the status of pathogen standards FSIS has proposed since 2018.

|

Proposed standard |

Year proposed |

Status |

Year last updated |

|

|

Salmonella in raw ground beef and beef trimmings |

2019 |

Paused |

1996 (when initial standard was set) |

|

|

Campylobacter in not ready-to-eat comminuted chicken |

2019 |

Paused |

2016 |

|

|

Campylobacter in not ready-to-eat comminuted turkey |

2019 |

Paused |

2011 (for carcasses) 2016 (for comminuted turkey) |

|

|

Salmonella in raw comminuted pork and pork cuts |

2022 |

Paused |

No previous standards |

|

|

Framework of standards for Salmonella in raw poultry (including proposed adulterants) |

2024 |

Ongoing |

2016 |

|

Source: Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) information. │ GAO‑25‑107613

Note: Comminuted meat and poultry is broken into pieces, such as by grinding or deboning. According to FSIS, the term “not ready-to-eat” means that the product is heat treated but not fully cooked and is not shelf stable.

In 1994, FSIS initially notified the public that any raw ground beef contaminated with E. coli O157:H7 would be considered adulterated following an E. coli outbreak in the early 1990s. Since then, USDA has also prioritized reducing Salmonella in poultry, and according to the regulations, FSIS selected it for pathogen standards in part because it is one of the most common bacterial causes of foodborne illness. The agency said the current pathogen performance standards do not distinguish between products that are heavily contaminated and contain the most virulent type of Salmonella from those that contain trace amounts not typically associated with foodborne illnesses. The proposed framework would address this by targeting specific Salmonella serotypes more frequently associated with illness and limiting the concentration of Salmonella permitted in certain raw poultry products.

According to agency officials, FSIS’s proposed strategy for determining levels at which Salmonella in raw poultry products is an adulterant is consistent with its existing approach to addressing STEC in specific raw beef products. Therefore, FSIS believes that intervention strategies aimed at reducing Salmonella on raw poultry products should be effective against other pathogens, these officials said. Once FSIS finalizes the proposed framework, the agency plans to assess whether it is more effective in reducing foodborne illnesses and consider applying this approach to developing standards for Salmonella in meat products and Campylobacter, according to agency officials. However, representatives from two groups we interviewed in 2024—a consumer safety and an industry stakeholder group—said that pathogens are not “one size fits all” and that strategies for addressing Salmonella may not work for other pathogens such as STEC.

FSIS officials did not know when the framework for Salmonella in raw poultry would be finalized and implemented.[33] Similarly, in 2018, we reported that FSIS did not have time frames for completing revisions to standards for Salmonella in beef products (carcasses and ground beef) or developing new standards for additional pork products. At the time, FSIS officials said that developing or revising pathogen standards required time and resources. We recommended that FSIS set time frames for determining what pathogen standards or additional policies would be needed to address pathogen levels in beef carcasses, ground beef, and pork products.

However, as discussed above, the agency has since paused four of its efforts to revise or develop new pathogen standards, such as for Salmonella in pork cuts and ground pork. The agency had proposed new standards for Salmonella in these two products in 2022, in response to our 2018 recommendation, which we then closed. In addition, FSIS does not have a prioritization plan or set time frame for when it will resume the development of new or updated standards for products other than raw poultry. When we asked FSIS about how it would prioritize the development of standards for these products and set time frames, FSIS officials cited limited resources as it focuses on the development of the proposed framework of standards for Salmonella in poultry.

Our 2024 risk-informed decision-making framework calls for agencies to collect new or existing information to specify a problem, define the decision that is to be made, and consider ranking projects by priority in order to direct limited resources to address these priorities.[34] As we have previously reported, FSIS generally develops new pathogen standards after the agency is directed to do so—for example, by a federal working group and an advisory committee—or after widespread outbreaks indicate a public health need.[35] In 2018, we reported that stakeholder groups we interviewed questioned whether the agency’s approach proactively addressed food safety risks. (See app. II for a timeline of foodborne illness outbreaks and FSIS’s actions in response to update or develop pathogen standards and adulterant determinations.)

As described above, it is not clear how agency officials are making prioritization decisions, including in developing or updating standards for reducing Salmonella in meat and Campylobacter in turkey parts. Furthermore, as previously stated, foodborne illness outbreaks have continued to occur since 2018, including outbreaks related to products for which FSIS has not finalized updated or new standards. Until FSIS develops a prioritization plan, it is unclear when FSIS will revise and develop new standards for Salmonella in meat and Campylobacter in turkey parts. Such a plan would need to fully document which products to address—including the basis on which such decisions should be made—and the additional policies needed to effectively reduce pathogens.

Further, our 2024 risk-informed decision-making framework also calls for agencies to develop an analysis plan that identifies options, assesses human health risks, gathers information about associated data gaps, and provides for coordination and consistency.[36] In addition, project management principles state that an analysis that identifies gaps allows organizations to manage shifting strategies.[37] Such an analysis would compare the organization’s current focus and future vision, which, according to these principles, is essential to properly managing strategic change and determining next steps.

The absence of standards leaves plants without clear direction on how they should approach reducing pathogens in their products, and FSIS without objective criteria to assess these plants’ performance, according to consumer safety groups. This can result in more pathogens reaching consumers and causing illness, the representatives said. However, agency officials could not confirm or provide indications that FSIS had assessed whether its current approach to focusing on the proposed framework for Salmonella in raw poultry is causing these or other gaps in oversight. As discussed above, risk-informed decision-making includes assessing risks to human health and gathering information about associated data gaps. Without reviewing the potential gaps or risks to public health that result from delaying proposed standards, the agency cannot fully understand the trade-offs of its approach or guide a prioritization plan. For example, as we previously mentioned, beef has been identified as the product of interest for outbreaks involving Salmonella, a standard for which FSIS paused its efforts to update.

USDA Has Taken Steps to Address Previously Identified Challenges but Faces Persistent Challenges

FSIS has taken steps to address challenges we identified

in our prior reports but continues to face challenges with developing and

updating standards and addressing its limited control over factors affecting

pathogen levels outside of meat and poultry processing and slaughter plants.

FSIS officials also said that challenges to its oversight efforts include plant

employees’ attention to sanitation.

|

FSIS’s Efforts to Improve Pathogen Detection and Quantification Some methods that the Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) uses to detect and quantify certain pathogens in food products are inefficient, resource intensive, and limited in scope, and take a long time to report sample results, according to FSIS officials. FSIS is undertaking efforts to improve existing methods used to detect and quantify Salmonella, Listeria monocytogenes, and STEC within its laboratories, according to agency officials. For example, FSIS coordinated with the Agricultural Research Service to develop sufficient scientific data and identify approaches that support new methods to detect and quantify pathogens, such as Salmonella.

FSIS Eastern Laboratory mass spectrometer and SCIEX 7500, used to test samples and detect compounds. Source: GAO summary of FSIS information (text) and GAO (image). | GAO‑25‑107613 |

FSIS Continues to Face Challenges with Setting Pathogen Standards and Addressing Its Limited Control Outside of Plants

FSIS has taken steps to address various challenges, including those we identified in our 2014 and 2018 reports. For example, FSIS made efforts to improve methods to detect and quantify certain bacteria in its laboratories (see sidebar and app. III). However, FSIS still faces two challenges we previously reported on: developing and updating pathogen standards and addressing its limited control over factors affecting the levels of pathogens outside of FSIS-regulated plants.

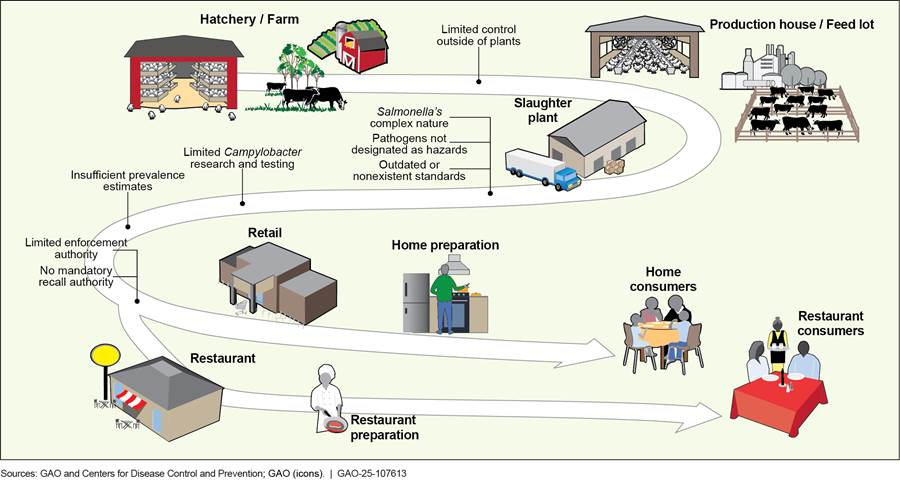

In our reports, we identified eight challenges that could hinder FSIS’s efforts to reduce pathogens in meat and poultry products across the farm-to-table continuum.[38] These challenges were

· FSIS’s limited control over factors that affect the level of pathogens outside of plants,

· pathogens not designated as hazards,

· the complex nature of Salmonella,

· limited Campylobacter research and testing,

· limited enforcement authority,[39]

· absence of mandatory recall authority,

· insufficient prevalence estimates,[40] and

· outdated or nonexistent standards.[41]

Similarly, representatives of the eight stakeholder organizations we interviewed for this report identified one or more of the following as persistent challenges: FSIS’s limited control outside of regulated plants, the complex nature of Salmonella, limited Campylobacter research, and insufficient prevalence estimates.

Figure 5 depicts each challenge and where it affects FSIS’s efforts to reduce pathogens in meat and poultry products along the farm-to-table continuum.

Figure 5: Challenges to Reducing Pathogens in Meat and Poultry Products Along the Farm-to-Table Continuum

Table 4 describes these challenges and FSIS’s actions, as of January 2025, to address them.

Table 4: Description of Previously Identified Challenges FSIS Faces in Reducing Pathogens in Meat and Poultry Products, and Its Actions Since 2018 to Address Them, as of January 2025

|

Limited control outside of regulated plants |

No regulatory jurisdiction over farm practices to reduce contamination before slaughter and processing or to prevent contamination of products in retail establishments, restaurants, and homes. |

|

· Removed barriers to the use of vaccines as a preharvest intervention method. · Updated poultry, beef, and pork guidance to include recommendations for preharvest interventions, and on-farm best practices. · Developed outreach materials for retailers on how to comply with recordkeeping requirements and best practices for sanitation to prevent Listeria monocytogenes contamination. |

|

|

Salmonella’s complex nature |

Salmonella is difficult to control as it is widespread in the natural environment, making it important to understand the genetic makeup of various serotypes. |

|

· Proposed a framework of standards for Salmonella in raw poultry products in 2024 focused on certain Salmonella levels and serotypes. · Conducted a comprehensive search of peer-reviewed scientific articles and epidemiological databases to develop a Salmonella risk profile. · Conducted two quantitative microbiological risk assessments for Salmonella in poultry to evaluate risk management options and public health benefits. |

|

|

Pathogens not designated as hazards |

Plants do not designate Salmonella and Campylobacter as hazards reasonably likely to occur. |

|

· Determined, in May 2024, that all plants that produce “not ready-to-eat” breaded stuffed chicken products should reassess, and, if necessary, revalidate hazard analysis and critical control point plans by May 1, 2025. · Developed guidance for pathogen and hazard control in specific food commodities and processes to clarify the circumstances under which plants should identify Salmonella and Campylobacter as hazards. · Published resources for small and very small plants with recommendations for designating certain pathogens, including Salmonella and Campylobacter, as hazards. |

|

|

Developing and updating standardsa |

Infrequent revision and development of standards to reflect changes in industry practices and consumption patterns. |

|

· Published, in May 2024, a final determination for “not ready-to-eat” breaded stuffed chicken. · Made two operational changes to existing pathogen standards since 2018. |

|

|

Limited Campylobacter research and testing |

Less is known about Campylobacter than Salmonella, and attribution methods need improvements. |

|

· Issued guidance in 2018 and 2021 to help plants control Campylobacter. · Developed new Campylobacter detection methods in 2018. · In 2022 implemented a new Campylobacter enrichment medium that provides accelerated results. · Identified and published several research priorities to improve the development of new scientific knowledge and research efforts for Campylobacter. · Collaborated with the Agricultural Research Service in 2023 to determine the combined effectiveness of antimicrobials on Campylobacter in poultry. |

|

|

Insufficient prevalence estimates |

Insufficient prevalence estimates, which are critical to understanding and addressing public health risks of foodborne illness. |

|

· Continued its testing approach, as described in our 2018 report, to routinely sample for Salmonella and Campylobacter to obtain better prevalence estimates and monitor changes over time. · Changed its verification and exploratory poultry sampling programs in 2019. |

|

|

Limited enforcement authority |

Federal court ruling that FSIS could not withdraw inspectors from a plant solely due to the plant’s failure to meet Salmonella standards.b |

|

· Congress has authorized FSIS to use enforcement tools to stop adulterated products from entering commerce.c With its recent adulterant determination, FSIS can now use enforcement tools to ensure that “not ready-to-eat” breaded stuffed chicken products containing certain levels of Salmonella do not enter commerce. |

|

|

No mandatory recall authority |

FSIS does not have mandatory food recall authority similar to FDA. |

|

· FSIS maintains its 2018 position that mandatory recall authority is not necessary for two reasons. FSIS has the authority to (1) recommend companies initiate voluntary recalls and (2) detain and pursue the seizure of any adulterated or misbranded meat or poultry product entering commerce. |

|

Source: GAO analysis of Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) information. │ GAO‑25‑107613

aIn our 2014 report, we used the term “outdated or nonexistent standards” to describe FSIS’s progress in developing and updating pathogen standards.

bSupreme Beef Processors v. U.S. Dep’t of Agric., 113 F. Supp. 2d 1048 (N.D. Tex. 2000). The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit upheld this decision in 2001.

cSee, e.g., Poultry Products Inspection Act, 21 U.S.C. 467a, and Federal Meat Inspection Act, 21 U.S.C. 672.

Of the eight challenges we previously identified, two notably continue to hamper FSIS’s efforts to reduce pathogens in food products: developing and updating pathogen standards and addressing its limited control outside of plants.

Developing and updating pathogen standards. As we previously discussed, though FSIS has designated one additional adulterant, it has not updated its existing pathogen standards or finalized any new pathogen standards since our 2018 report. We previously reported that FSIS generally develops new pathogen standards after a federal working group directs the agency to do so or after widespread outbreaks indicate a public health need. However, the agency’s Foodborne Illness Outbreaks investigation reports for fiscal years 2018 through 2023 indicate that since 2018, outbreaks have continued to occur related to products for which FSIS has not finalized new or updated pathogen standards.

Representatives from one industry and two consumer advocacy groups told us that FSIS’s existing pathogen standards for meat and poultry products have not achieved the intended public health impacts. Specifically, these three stakeholders stated that while the prevalence of Salmonella has declined, there has not been a correlating decline in human illnesses associated with Salmonella. As previously discussed, FSIS officials stated that the current pathogen performance standards do not distinguish between products that are heavily contaminated and contain the most virulent type of Salmonella from those that contain trace amounts not typically associated with foodborne illnesses. According to officials, the proposed Salmonella framework would address this by targeting specific Salmonella serotypes more frequently associated with illness and limiting the concentration of Salmonella permitted in certain raw poultry products.

An additional consumer advocacy group we interviewed generally expressed concerns about FSIS’s outdated or nonexistent pathogen standards for meat and poultry products and the impact on the agency’s ability to effectively protect public health and achieve pathogen reduction goals. Specifically, this stakeholder stated that by not updating existing or developing new pathogen standards, FSIS puts consumers at risk because the potential for foodborne illnesses may increase.

As previously stated, without reviewing whether delaying several proposed standards could cause gaps, or risks to public health, the agency cannot fully understand the trade-offs of its approach to focus on Salmonella in raw poultry.

Limited control outside of regulated plants. FSIS has taken steps since our 2018 report to address its lack of regulatory jurisdiction before slaughter and processing. Food safety stakeholders we interviewed stated that the agency has taken steps to mitigate its limited control beyond regulated slaughter plants. However, the agency is still limited in its control because APHIS maintains regulatory jurisdiction over farms, and FSIS’s jurisdiction begins once products enter slaughter plants, according to FSIS officials.

Five of the eight stakeholders we interviewed stated that FSIS’s limited control outside of plants continues to affect its ability to effectively reduce pathogens in meat and poultry products. Specifically, these stakeholders stated that the introduction of pathogens and contamination in FSIS-regulated products often begins at farms, over which the agency lacks oversight authority. This results in FSIS having to implement additional pathogen control methods to minimize the spread of pathogens in its regulated slaughter plants, according to stakeholders.

APHIS officials stated that while APHIS maintains regulatory jurisdiction over farms, it does not conduct surveillance for foodborne pathogens on farms prior to harvest of livestock and poultry. Instead, according to APHIS and FSIS officials, the agencies coordinate in various ways. In 2017, we reported that coordination with stakeholders who have the relevant authority and access to farms could help APHIS and FSIS fully investigate an outbreak.[42] We recommended that developing a framework for deciding when on-farm investigations are warranted during outbreaks would help APHIS and FSIS identify factors that contribute to or cause foodborne illness outbreaks. To address this recommendation, APHIS, FSIS, and state and industry representatives hold quarterly preharvest meetings to provide updates on foodborne illness investigations, identify best practices, and discuss research initiatives. In addition, FSIS and APHIS staff hold quarterly “farm to fork” meetings to share information. During these meetings, FSIS presents high-level pathogen trends that are not outbreak or occurrence specific, and APHIS provides information on pathogen occurrence and trends occurring at the farms and breeding facilities prior to entering processing plants. These conversations help to inform FSIS of the pathogens entering plants from farms.

FSIS and APHIS have an existing memorandum of understanding (MOU), established in 2014, that outlines each agency’s roles and responsibilities in assessing the root cause of foodborne illness outbreaks. According to FSIS officials, the MOU provides structure for working with APHIS to communicate findings, interventions, and actions that can be taken during outbreak investigations. The MOU does not identify specific foodborne pathogens of concern (such as Salmonella, Campylobacter, Listeria monocytogenes, or STEC) or detail how the agencies are to coordinate on root cause assessment and outbreak investigation activities involving those pathogens. Additionally, in 2024, APHIS officials stated that the MOU was never fully implemented due to the limitations of the jurisdictional and regulatory authorities of the agencies involved.

Some stakeholders told us that FSIS could help address this challenge by better coordinating with APHIS. However, FSIS and APHIS officials stated that updating the MOU would not be an effective use of resources or an appropriate tool to engage on food safety issues. As previously stated, both agencies continue to communicate on foodborne illness investigations, best practices, and research initiatives during their collaborative meetings. Specifically, they highlighted their “farm to fork” meetings, weekly USDA food safety and One Health coordination meetings, and the Interagency Foodborne Outbreak Response Collaboration.

Our 2024 risk-informed decision-making framework calls for agencies to define different stakeholders’ and governments’ authorities and interests and, based on this information, define the roles they will play throughout the decision-making process.[43] In addition, leading practices for interagency collaboration call for agencies to, among other things, define common outcomes and leverage resources and information.[44] By updating their 2014 MOU, or developing a new agreement, APHIS and FSIS can more clearly define their desired outcomes to better prevent and control the likelihood of foodborne illness outbreaks and promote consistency in inspection, investigation, and information-sharing practices. Specifically, the agencies would need to clearly identify specific pathogens of concern and each agency’s responsibilities in coordinating and responding to occurrences of those pathogens in outbreak investigation activities. Doing so will also better position FSIS to address its limited control outside of plants and more effectively reduce pathogens in meat and poultry products.

FSIS Observed Challenges with Employee Sanitation Practices in Plants

FSIS officials and documents emphasize that sanitation in plants is critical in ensuring the production of safe and unadulterated products. FSIS’s Quarterly Enforcement Reports we reviewed identified actions FSIS initiated due to plants’ failure to follow established sanitation procedures or meet regulatory requirements. In addition, inspectors we spoke with characterized plant employees’ attention to maintaining adequate sanitation as a challenge.

Employee sanitation practices in plants. Poor sanitation in plants could present risks for the spread of pathogens on products, according to an FSIS food inspector and consumer safety inspectors we interviewed. FSIS officials stated that inspectors ensure each plant meets established regulatory requirements for sanitation practices in meat and poultry plants, and issue reports on their findings. As previously discussed, inspectors serve as the first line of defense in ensuring products are free of diseases or adulterants.[45] They maintain responsibility for much of the day-to-day in-plant inspections of animals before and after slaughter to ensure that plants operate within their written plans for sanitation, processing, and implementation of Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point regulations.[46]

According to FSIS documentation and regulations, Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point plans and sanitation regulations are necessary to ensure that products are handled and held in a sanitary manner and to support the protection of public health.[47] FSIS has the regulatory authority to take actions due to insanitary conditions or practices, among other things.[48] FSIS can also withdraw a grant of inspection or refuse to grant an inspection based on plants’ failure to meet the sanitation and food safety regulatory requirements.[49] For example, FSIS can take actions when plants do not have documented Sanitation Standard Operating Procedures or the plant produced and shipped an adulterated product.

To support its inspectors’ efforts, FSIS provides directives for plants on effective methods for maintaining sanitary conditions to comply with FSIS’s regulations. For example, FSIS’s Sanitation Performance Standards and Compliance Guide includes directions for plant employees on when and where to clean their hands when in contact with products, food contact surfaces, and packaging materials.

However, FSIS inspectors at both large and small plants have observed challenges with sanitation awareness among employees within plants. For example, three of the six inspectors we spoke with expressed concerns over employees infrequently washing their hands after handling several different raw products. Inspectors also observed products, guts, and equipment used to carve raw products being dropped onto the floor or open drains within plants.

FSIS summarizes enforcement actions it takes in its publicly available Quarterly Enforcement Reports.[50] FSIS can take a suspension action when products are produced under insanitary conditions, or plants ship adulterated products, among other things.[51] FSIS’s Quarterly Enforcement Reports identified approximately 260 suspension actions initiated at plants from fiscal years 2019 through 2024 because of insanitary conditions.[52] In some cases, FSIS suspended the establishment’s operations. In others, the agency deferred taking enforcement actions following a review of the plants’ submitted plans for corrective and preventative actions.[53] In one case, a plant was found to have also produced and distributed adulterated products.

According to some inspectors, plants emphasize safety protocols with readily available reminders on safety best practices and guidance. Three inspectors stated that there are informal and formal actions that they can and do take to communicate the importance of sanitation on food safety.[54] Additional inspectors expressed that increased awareness among employees on sanitation procedures would be beneficial.

Providing instruction to its regulated plants to more frequently remind their employees about FSIS’s sanitation procedures could be helpful, according to three of six inspectors. FSIS officials stated that the agency previously developed outreach materials to assist retailers in complying with recordkeeping requirements and improve awareness of best practices for sanitation to prevent Listeria monocytogenes contamination. Taking similar actions to offer educational materials or signage that focus on sanitation to its regulated plants would allow FSIS to better support these plants in ensuring that employees comply with FSIS’s requirements and guidance to reduce the spread of pathogens in meat and poultry products.

Conclusions

FSIS plays a key oversight role in preventing illness-causing pathogens such as Salmonella, Campylobacter, Listeria, and STEC from entering the raw and ready-to-eat meat and poultry products purchased and consumed by the public.

Since our 2018 report, FSIS has taken the important step of determining an adulterant for one type of poultry product in response to public health needs. However, outbreaks continue to occur, including those involving products for which FSIS has not updated or developed pathogen standards since 2018 or earlier. FSIS’s decision to focus its resources on a framework of standards for Salmonella in raw poultry, when finalized, will address one of the pathogens and products most responsible for illness and death. In the meantime, however, to avoid gaps in the oversight of pathogens that could impact other meat and poultry products, the agency needs to better understand the trade-offs of solely focusing on a single framework—such as by assessing risks to human health. FSIS also needs to document how it will prioritize its actions for other standards after it finalizes the Salmonella in raw poultry framework.

FSIS has taken steps to address the eight oversight challenges that we identified in 2018. However, the agency continues to face challenges with developing and updating pathogen standards and its limited control outside of its regulated plants. Updating their memorandum of understanding, or developing a new agreement, to identify specific pathogens of concern and each agency’s responsibilities would allow FSIS and APHIS to more clearly define their desired outcomes for preventing and controlling likelihood of foodborne illness outbreaks. It would also enable FSIS to better address its limited control outside of plants.

In addition, given the critical role of sanitation in FSIS’s oversight, inspectors’ observations of plant employees’ sanitation practices provide an opportunity for FSIS to further support plants’ efforts to ensure compliance with FSIS requirements. Providing educational materials or signage focused on sanitation for its regulated plants to encourage better sanitation practices among their employees could help reduce the potential for poor sanitation to spread harmful pathogens on products that can endanger human health.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making a total of five recommendations, including four to FSIS and one to APHIS. Specifically:

The Administrator of FSIS should develop a prioritization plan to fully document which products to address and the additional policies needed to effectively address pathogen reduction for Salmonella in meat and standards for Campylobacter in turkey parts. (Recommendation 1)

The Administrator of FSIS should review the public health impacts of delaying proposed pathogen standards for Salmonella in meat and standards for Campylobacter in turkey parts, to inform a prioritization plan. This review could include assessing risks to human health and gathering information about potential gaps in oversight. (Recommendation 2)

The Administrator of FSIS should update its memorandum of understanding with APHIS, or create a new agreement, to clearly identify specific pathogens of concern and each agency’s responsibilities in coordinating and responding to these pathogens’ occurrence in outbreak investigation activities. (Recommendation 3)

The Administrator of APHIS should update its memorandum of understanding with FSIS, or create a new agreement, to clearly identify specific pathogens of concern and each agency’s responsibilities in coordinating and responding to these pathogens’ occurrence in outbreak investigation activities. (Recommendation 4)

The Administrator of FSIS should offer educational materials, such as signage, to its regulated plants on sanitation to support their efforts to comply with FSIS’s requirements and guidance to reduce the spread of pathogens in meat and poultry products. (Recommendation 5)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) for review and comment. In its comments, reproduced in appendix IV, USDA did not agree or disagree with our five recommendations, stating that it will provide an additional response to formally address the recommendations of executive action upon receipt of the final report and statement of action. USDA also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Agriculture, the Administrator of the Food Safety and Inspection Service, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at (202) 512-3841 or MorrisS@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix V.

Steve D. Morris

Director, Natural Resources and Environment

This report examines (1) the extent to which the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) has developed pathogen standards for meat and poultry products and (2) additional steps USDA has taken to address challenges we identified in 2014 and 2018 to reducing the level of pathogens, and new challenges the agency faces.

To examine the extent to which USDA has developed pathogen standards for meat and poultry products, we reviewed our prior findings and recommendations from September 2014 and March 2018 on pathogen standards for meat and poultry products.[55] We also reviewed relevant laws and regulations and the Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) annual performance plans covering the period from fiscal years 2018 through 2023, as well as the agency’s two most recent strategic plans. We reviewed relevant Federal Register notices on specific pathogen standards, including proposed standards, for meat and poultry from 1996, when FSIS first established the standards, through 2024.[56] We identified relevant performance goals and measures in FSIS annual performance plans from fiscal years 2018 through 2023. We also reviewed FSIS annual foodborne illness outbreak investigations from 2018 through 2023.

We also obtained information from FSIS documentation and interviews with agency officials on the agency’s plans to review or revise pathogen standards. We obtained information from agency documentation and interviews with FSIS officials regarding the process for developing new pathogen standards and compared this process with the federal risk-informed decision-making framework and the Project Management Institute’s standards and leading practices for portfolio management.[57]

To examine any additional steps that USDA has taken to address the challenges we identified in 2014 and 2018 that it faces in reducing pathogens in meat and poultry, we reviewed agency documentation on the steps it has taken to address these challenges since 2018, including documentation on relevant laws and regulations; Federal Register notices; FSIS’s 2017 through 2023 strategic plans, annual performance plans and related performance reports from fiscal years 2018 through 2024, and USDA and FSIS websites. We also reviewed reports from the Interagency Food Safety Analytics Collaboration and USDA’s Office of Inspector General. We compared FSIS’s memorandum of understanding for collaboration with USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service with leading practices to enhance interagency collaboration.[58] We also reviewed FSIS’s guidance, directives, and regulations regarding inspection and sanitation best practices and requirements. To determine how FSIS undertakes enforcement efforts to ensure that meat, poultry, and processed egg products are safe and wholesome for consumers, we reviewed FSIS’s Quarterly Enforcement Reports to identify the total number of suspension actions initiated at plants due to insanitary conditions from fiscal years 2019 through 2024.[59]

In addition, we interviewed FSIS headquarters officials on the status of FSIS efforts to update existing pathogen standards and develop new standards. We also interviewed six FSIS food and consumer safety inspectors about how the status of updates to these standards impacts their ability to conduct inspections, and any challenges or observations.

We also conducted a site visit to FSIS’s Eastern Laboratory to learn about the agency’s current protocols for inspecting and conducting microbiological testing on meat, poultry, and processed egg products that FSIS regulates, and other foodborne pathogen-related activities.

We identified an initial group of stakeholders from our prior work, specifically from those we interviewed in our 2018 report on meat and poultry pathogens.[60] In addition, we asked these groups for recommendations on other stakeholders we should consider contacting and expanded the list, as needed. We selected these stakeholders because they are knowledgeable about FSIS’s food safety programs and provide a range of views on the topic.

In total, we identified a nongeneralizable sample of eight stakeholder groups: three representatives from industry, four representatives from consumer advocacy groups, and one federal advisory committee (see table 5 for stakeholders interviewed). Views from those we selected based on their knowledge cannot be generalized to all stakeholders who have knowledge about FSIS’s food safety programs (i.e., those we did not interview), but they provide illustrative examples.

|

Type of Organization |

Stakeholder |

|

Industry |

National Pork Producers Council |

|

Meat Institute |

|

|

U.S. Poultry and Egg Association |

|

|

Consumer advocacy |

Center for Science in the Public Interest |

|

Consumer Federation of America |

|

|

Consumer Reports, Inc. |

|

|

STOP Foodborne Illness, Inc. |

|

|

Federal advisory committee |

National Advisory Committee on Microbiological Criteria for Foods |

Source: GAO. | GAO‑25‑107613

We conducted this performance audit from June 2024 to January 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

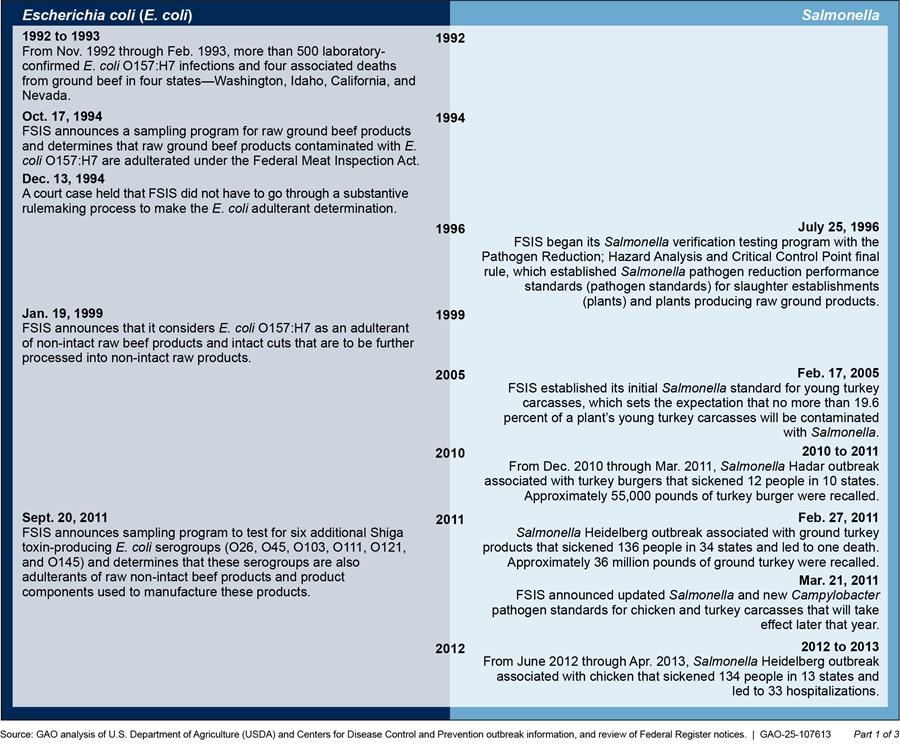

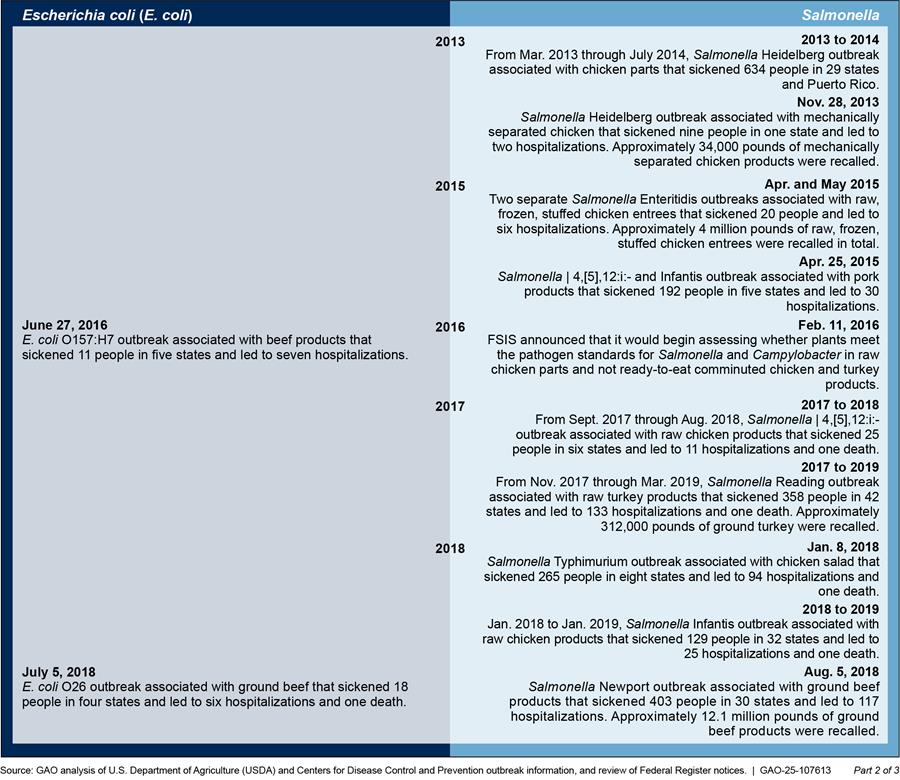

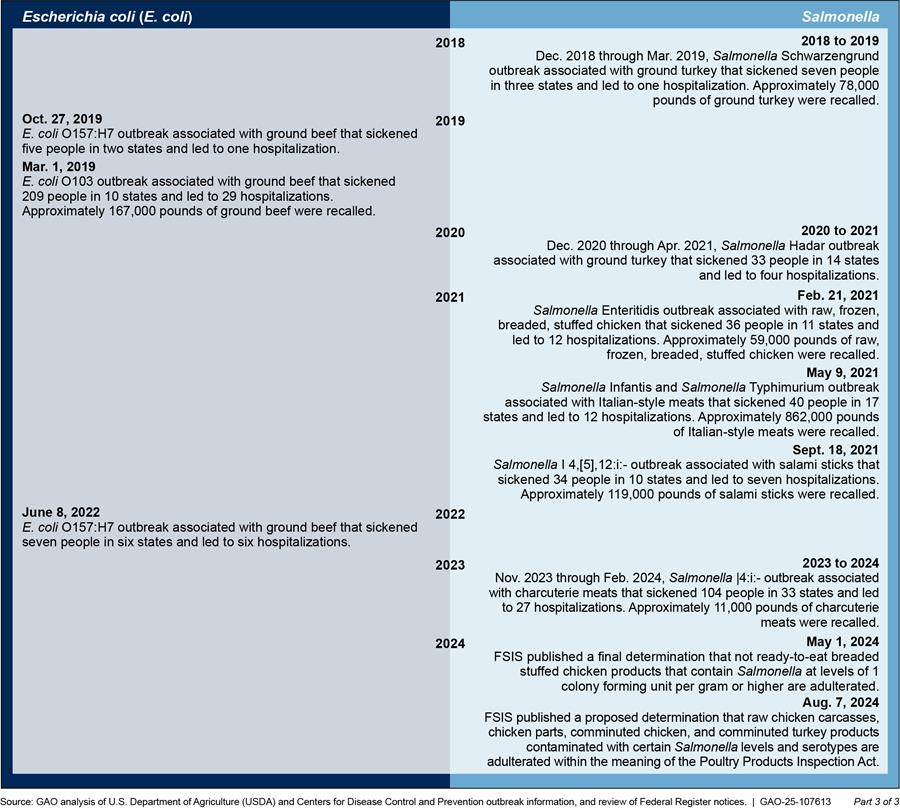

Appendix II: Timeline of Food Safety and Inspection Service’s (FSIS) Pathogen Standards and Adulterant Determinations

FSIS generally develops new pathogen standards after a federal working group or an advisory body directs it to do so or widespread outbreaks indicate a public health need. Figure 6 provides a timeline of foodborne illness outbreaks and FSIS’s actions in response to update or develop pathogen standards and adulterant determinations.

Figure 6: Timeline of E. coli and Salmonella Outbreaks and USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service’s (FSIS) Actions in Response to Update or Develop Pathogen Standards and Adulterant Determinations

Note: Specific dates listed indicate the first reported illness associated with the outbreak.

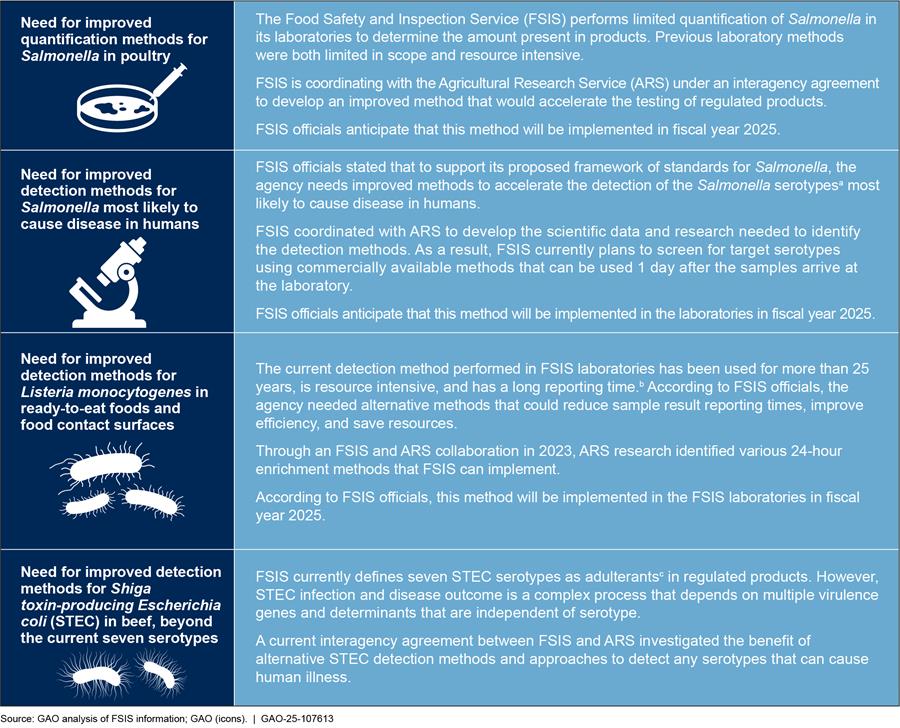

Appendix III: FSIS Efforts to Address Limitations to Pathogen Detection and Quantification Methods in Its Laboratories

FSIS officials identified limitations in existing methods used to detect or quantify Salmonella, Listeria monocytogenes, and STEC within FSIS laboratories. For example, FSIS officials said that some methods are inefficient, limited in scope, or have long reporting times. FSIS has begun taking steps to address these limitations, according to agency officials.

Figure 7 provides details on each of the newly identified challenges and FSIS’s actions to address them.

Figure 7: Newly Identified Challenges to the Food Safety and Inspection Service’s (FSIS) Pathogen Detection and Quantification Methods, and Steps FSIS Has Taken to Address Them, as of January 2025

aAccording to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), serotypes are groups within a single species of microorganism, e.g. bacteria, that share distinctive surface structures. Salmonella has various serotypes, some of which may cause greater illnesses to humans. CDC, “Serotypes and the Importance of Serotyping Salmonella,” https://www.cdc.gov/salmonella/reportspubs/salmonella-atlas/serotyping-importance.html, accessed Nov. 14, 2024.

bAccording to FSIS officials, as of August 2024, the agency continues to use a 2-step 48-hour enrichment period—the last of the 48-hour enrichments in major pathogen detection technologies.

cThe Federal Meat Inspection Act and Poultry Products Inspection Act define “adulterated” meat and poultry products to include, among other things, products that contain any added “poisonous or deleterious substance which may render it injurious to health.” 21 U.S.C. 601(m)(1), 453(g)(1). FSIS has determined that certain levels of a pathogen in a product render it “adulterated,” meaning it cannot be sold in commerce. Adulterant determinations are based on pathogen and product pairs.

Steve D. Morris, (202) 512-3841 or MorrisS@gao.gov

In addition to the contact above, Tahra Nichols (Assistant Director), Leah English (Analyst in Charge), Adrian Apodaca, Tara Congdon, Rebecca Conway, Lorraine Ettaro, Chaya Johnson, and Cynthia Norris made key contributions to this report.

Food Safety: USDA Needs to Strengthen Its Approach to Protecting Human Health from Pathogens in Poultry Products. GAO‑14‑744. Washington, D.C.: September 30, 2014.

Antibiotic Resistance: More Information Needed to Oversee Use of Medically Important Drugs in Food Animals. GAO‑17‑192. Washington, D.C.: March 2, 2017.

Food Safety: USDA Should Take Further Action to Reduce Pathogens in Meat and Poultry Products. GAO‑18‑272. Washington, D.C.: March 19, 2018.

High-Risk Series: Efforts Made to Achieve Progress Need to Be Maintained and Expanded to Fully Address All Areas. GAO‑23‑106203. Washington, D.C.: April 20, 2023.

Government Performance Management: Leading Practices to Enhance Interagency Collaboration and Address Crosscutting Challenges. GAO‑23‑105520. Washington, D.C.: May 24, 2023.

Environmental Hazards: A Framework for Risk-Informed Decision-Making, GAO‑24‑107595. Washington, D.C.: September 23, 2024.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on Facebook, Flickr, X, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our RSS Feeds or Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7700

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, ClowersA@gao.gov, (202) 512-4400, U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7125, Washington, DC 20548

Public Affairs

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, KaczmarekS@gao.gov, (202) 512-4800, U.S.

Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7149

Washington, DC 20548

Strategic Planning and External Liaison

Stephen J. Sanford, Managing

Director, spel@gao.gov, (202) 512-4707

U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7814, Washington,

DC 20548

[1]Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CDC and Food Safety, factsheet (Atlanta, GA: Mar. 13, 2023).