U.S. ARMS TRANSFERS

State Department Should Improve Investigations and Reporting of Foreign Partners’ End-Use Violations

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional committees.

For more information, contact James A. Reynolds at ReynoldsJ@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

The State Department is responsible for investigating and reporting end-use violations to Congress—that is, foreign partners’ violations of requirements for the purpose, transfer, and security of defense articles and services they received from the U.S. government. State relies primarily on the Department of Defense (DOD) to identify incidents that could constitute violations. As of February 2025, DOD was tracking more than 150 incidents, many of them detected by DOD security cooperation organizations (SCO) at diplomatic posts. However, GAO found State has not provided clear guidance to DOD defining the types of incidents that warrant State’s attention. Without such guidance, SCO officials told GAO they exercise professional judgement in deciding whether to inform State about incidents. As a result, State may be unaware of potential violations it needs to investigate.

Further, State’s investigations of potential end-use violations are inconsistent, in part because its guidance for conducting investigations does not establish required actions or time frames. For example, for one potential violation, State officials gathered information, reviewed transfer agreements, and worked with SCO officials to resolve it. For another potential violation, State officials did not take any action. Moreover, State has not consistently documented the status or findings of its investigations since 2019. As a result, State does not have readily available information about foreign partners’ compliance with arms transfer agreements. Such information could inform decisions about future arms sales. In addition, State has not shared its findings with SCO officials, who could implement measures to address violations or prevent their recurrence.

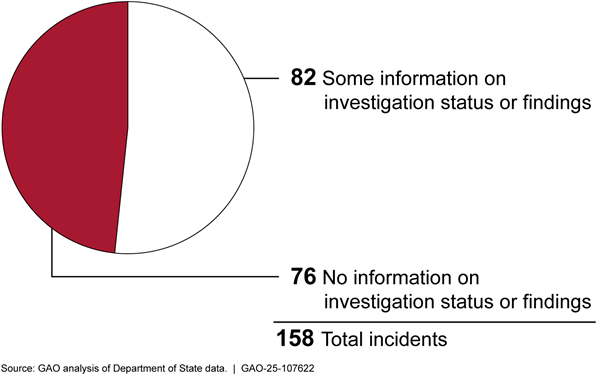

Status of State Department Investigations Is Missing for Many Incidents That Potentially Violated U.S. Arms Transfer Agreements as of February 2025

Since 2019, State has reported three end-use violations to Congress, but State cannot show that it determined whether most known incidents met legal reporting criteria. Under law, State is required to report to Congress (1) substantial violations of purpose, transfer, and security requirements that may have occurred and (2) any unauthorized transfers that did occur. State documented in memorandums its determinations for three incidents. However, State officials could not provide similar documentation for more than 150 others. State officials said they do not have formal procedures for determining whether incidents meet the reporting criteria or for recording these determinations. Without guidance establishing such procedures, State cannot ensure it is reporting to Congress in accordance with the law. As a result, Congress may not have information to support oversight, such as considering legislation to prohibit transfers of defense articles and services to foreign partners that have violated their agreements.

Why GAO Did This Study

To enhance U.S. national security, the U.S. government provides defense articles and services, such as weapons and military training, to dozens of foreign partners around the world. Recipients agree to comply with legal end-use requirements that prohibit using the provided articles or services for unauthorized purposes, transferring them to unauthorized entities, and failing to keep them secure.

Congress included a provision in House Report 118-301 for GAO to review State and DOD procedures related to alleged violations of relevant end-use requirements of defense articles and services. This report examines the extent to which (1) State and DOD identify and track potential violations, (2) State investigates potential violations and communicates its findings to agency stakeholders, and (3) State reports appropriate incidents to Congress.

GAO reviewed laws and agency policies for guidance on identifying, investigating, and reporting potential violations to Congress. GAO also analyzed documentation and information about potential violations, State’s investigations, and its reports to Congress. In addition, GAO interviewed agency officials in the U.S. and at 10 diplomatic posts, including during visits to five countries that GAO selected to reflect an array of incident types and geographic locations.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making six recommendations to State, including that it provide guidance to DOD for reporting incidents to State, update its guidance for investigating incidents, and develop guidance that establishes procedures for determining whether to report incidents to Congress. State agreed with these recommendations.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

AECA |

Arms Export Control Act, as amended |

|

DOD |

Department of Defense |

|

DSCA |

Defense Security Cooperation Agency |

|

FAA |

Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, as amended |

|

PM/RSAT |

Bureau of Political-Military Affairs, Office of Regional Security and Arms Transfers |

|

SCO |

security cooperation organization |

|

State |

Department of State |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

September 16, 2025

Congressional Committees

To enhance U.S. national security, the U.S. government has provided U.S. defense articles and services to more than 100 foreign partners around the world. Presidents have used the transfer of such articles and services to advance foreign policy goals, ranging from supporting strategically important foreign partners to building global counterterrorism capacity after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001.

To protect U.S. military and technological advantages and advance foreign policy objectives, and as a condition of this assistance, foreign partners agree to end-use requirements that prohibit using the provided articles or services for unauthorized purposes, transferring them to unauthorized entities, and failing to keep them secure. If a foreign partner is found to be in substantial violation of these requirements, future transfers to those partners can be prohibited by application of U.S. law.

U.S. law requires the President to report to Congress on receipt of information that certain types of end-use violations may have occurred and when transfer violations have occurred.[1] The President delegated this responsibility to the Secretary of State.[2] The Department of Defense’s (DOD) Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA) and security cooperation organizations (SCO), among others, identify potential violations and inform the Department of State.

House Report 118-301 included a provision for us to review State and DOD procedures related to foreign partners’ alleged violations of relevant end-use requirements.[3] In this report, we evaluate the extent to which (1) State and DOD identify and track potential violations; (2) State investigates these incidents and communicates its findings to relevant stakeholders; and (3) State reports appropriate incidents to Congress. This review focuses on government-to-government transfers,[4] such as transfers through State’s Foreign Military Sales program under Title 22 and DOD’s Building Partner Capacity programs under Title 10.[5]

To address our objectives, we focused on incidents identified, investigated, or reported to Congress from January 2019 through February 2025. We reviewed laws and assessed agency guidance on identifying, investigating, and reporting to Congress potential violations of bilateral arms transfer agreements. To understand how State and DOD have identified potential violations, we examined agency documents and information, such as embassy memos and data from an information module within DSCA’s Security Cooperation Information Portal. DSCA uses this module—which this report refers to as the DSCA tracker—to record potential violations of transfer agreements and to share information with State and SCO officials.

In addition, to understand State and DSCA processes, we reviewed a nongeneralizable sample of 12 potential violations that we selected from among the incidents listed in the DSCA tracker and other incidents identified by U.S. officials but not listed in the DSCA tracker. We selected these incidents to illustrate, among other things, a variety of different violation types, open and closed investigations, and incidents reported or not reported to Congress. We used the 12 selected incidents as examples when asking State and DSCA for information. We requested interviews with officials of the 12 SCOs at diplomatic posts in the countries where the selected incidents occurred, and we met with officials of 10 SCOs.

We evaluated State’s processes for identifying, investigating, and reporting incidents against its objectives as well as principles 3, 6, 10, 12, and 15 of Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government.[6] In addition, we reviewed relevant laws and analyzed State documentation of its reporting to Congress on potential violations. We also discussed identifying potential violations, investigating or supporting investigations of incidents, and reporting incidents to Congress with State, DOD, and embassy officials. Moreover, we visited five countries with alleged end-use violations that reflected a variety of numbers and types of incidents, geographic locations, and presence of conflict. In these countries, we observed, among other things, inventory checks of U.S. defense articles provided to foreign partners.

We conducted this performance audit from June 2024 to August 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

The United States is the world’s largest provider of defense articles and services to foreign partners. In fiscal year 2024, the total value of transferred defense articles, security services, and security activities reached an all-time high of $117.9 billion, according to State reporting. (Fig. 1 shows examples of defense articles the U.S. government has transferred to foreign partners.)

Mechanisms for these transfers include the Foreign Military Sales program, in which the U.S. government and a foreign government negotiate an agreement for the purchase of defense articles or services. Transfer mechanisms also include DOD’s Building Partner Capacity programs to provide equipment and training to foreign partners’ national security forces.

Legislative Authorities

The Arms Export Control Act (AECA), as amended, provides the President the authority to control the transfer of defense articles and establishes congressional notification requirements for transfers of U.S. defense articles and services to foreign entities.[7] The AECA states that no sales or deliveries may be made to a foreign partner if the partner has previously used defense articles in a manner that substantially violates agreed-on terms.[8] A violation may be substantial in terms of either the quantities involved or the gravity of its consequences. These terms are generally documented in transfer agreements between the U.S. and partner governments. If no such terms exist regarding the purposes for which defense articles or services are used, recipients must limit their use to those purposes set forth at section 4 in the AECA, which include internal security, legitimate self-defense, and prevention of the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction.[9]

The Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 (FAA), as amended, includes provisions establishing eligibility requirements for the transfer of defense articles to foreign partners. The FAA requires—subject to specified exceptions—the termination of future transfer of defense articles if a recipient is found to be in substantial violation of an agreement with the United States or otherwise uses U.S. defense articles for unauthorized purposes.[10]

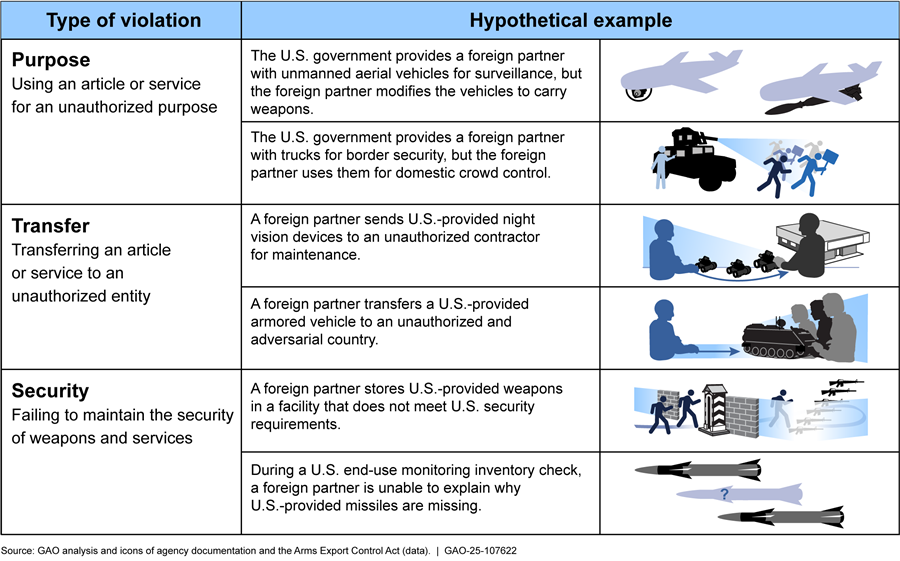

The AECA and the FAA establish three types of violations with regard to U.S. defense articles and services provided to foreign partners: (1) using an article or service for an unauthorized purpose, which this report refers to as a purpose violation; (2) transferring an article or service to an unauthorized entity, which this report refers to as a transfer violation; and (3) failing to maintain the security of articles and services, which this report refers to as a security violation.[11] Either the President or Congress may determine that a recipient is in substantial violation of a transfer agreement with respect to these categories, thereby rendering the recipient ineligible for continued transfers of defense articles.[12] The recipient would remain ineligible until the President determines that the violation has ceased and the recipient has given satisfactory assurances to the President that such a violation will not recur.

The AECA requires the President to establish a program for monitoring the end use of defense articles and defense services sold, leased, or exported under that act or the FAA. This monitoring program must, to the extent practicable, be designed to provide reasonable assurance that recipients are complying with requirements imposed by the U.S. government on the purpose, transfer, and security of defense articles and defense services.

Department of State’s Role

The Secretary of State is responsible for executing foreign policy, including arms transfer agreements. State ensures that foreign partners agree to the requirements in the AECA and FAA through

· letters of offer and acceptance, in which the recipient agrees to comply with purpose, transfer, and security requirements for the specific items being transferred, and

· bilateral agreements, also known as Section 505 agreements, in which the foreign partner agrees to comply with purpose, transfer, and security requirements for U.S. items provided under various U.S. authorities. According to State and DOD officials, Section 505 agreements are often necessary to ensure State can monitor items provided under DOD authorities.[13]

The Bureau of Political-Military Affairs’ Office of Regional Security and Arms Transfers (PM/RSAT) oversees the Foreign Military Sales program and other arms transfers to foreign partners, according to State’s Foreign Affairs Manual.[14] Section 3 of the AECA requires the President, who delegated the authority to the Secretary of State, to report to Congress (1) on receipt of information that a substantial violation of an arms transfer agreement with respect to a U.S. item’s purpose, transfer, or security may have occurred; and (2) when an unauthorized transfer of a U.S. item has occurred, such as the transfer of a U.S.-provided article to another country without U.S. approval. According to State’s website, on being notified of a potential violation, State gathers information to confirm the reported incident, assesses whether it constitutes a violation, and determines any U.S. government actions needed to prevent a recurrence.

Department of Defense’s Role

DOD, which is responsible for end-use monitoring of defense articles provided under Foreign Military Sales and Title 10 authorities, conducts this monitoring through its Golden Sentry End-Use Monitoring program. DOD’s Security Assistance Management Manual provides guidance for the program. DSCA and SCOs have various monitoring roles. For example, SCO officials at U.S. diplomatic posts manage defense articles transfer programs, liaise with foreign partner officials for defense article transfer issues, and conduct end-use monitoring.

According to the Security Assistance Management Manual, DSCA is also responsible for tracking reported potential violations and, when necessary, collecting additional information about incidents and reporting them to State for investigation.

State Largely Relies on DOD to Identify Potential Violations but Has Not Specified Incident Types Warranting Attention

To support State’s investigations of potential violations of arms transfers agreements, PM/RSAT largely relies on DOD SCO officials to identify potential violations and on DSCA officials to track them. However, the types of violations PM/RSAT expects DSCA and SCOs to report and the expected timing of these reports are unclear. Providing guidance to DSCA and SCOs for reporting incidents would help PM/RSAT ensure it is informed in a timely manner about potential violations requiring investigation. Such information would, in turn, give PM/RSAT and relevant stakeholders a more accurate understanding of foreign partners’ compliance with arms transfer agreements.

State Primarily Relies on DOD to Identify and Track Potential Violations

State Learns of Potential Violations Mainly Through SCOs’ End-Use Monitoring

PM/RSAT officials told us that they become aware of potential violations primarily as a result of end-use monitoring that SCOs conduct in partner countries. According to the Security Assistance Management Manual, SCOs are required to immediately report any potential purpose, transfer, or security violations to PM/RSAT, DSCA, and the relevant combatant command. PM/RSAT and DSCA have dedicated e-mail accounts for receiving information about potential violations.

|

Limitations Affecting DOD End-Use Monitoring Limited access for end-use monitoring. Several SCOs we spoke with said that because of security concerns, such as active conflict, or access limitations imposed by foreign partners, they were unable to travel to facilities storing weapons that require enhanced end-use monitoring. In 2024, we reported that DOD had had difficulty accessing sites to conduct enhanced end-use monitoring in Ukraine (see GAO‑24‑106289). DSCA revised the Security Assistance Management Manual in 2022 to allow foreign partners to conduct inventory checks in hostile environments and self-report the results to complement direct observations by U.S. officials. Monitoring activities not designed to identify purpose violations. In 2022, we found that end-use monitoring activities were not designed to identify foreign partners’ violations of transfer agreements regarding the use of U.S. defense articles and services for authorized purposes (see GAO‑23‑105856). We recommended that DOD evaluate whether its Golden Sentry program provides reasonable assurance that DOD-provided equipment is used only for its intended purpose and develop a plan to address any deficiencies it identifies. In response to this recommendation, as of September 2024, DOD officials said that they are collaborating with State to implement a study to evaluate the Golden Sentry program. Source: GAO. | GAO‑25‑107622 |

SCOs can identify potential violations through routine end-use monitoring and enhanced end-use monitoring. (The sidebar discusses limitations affecting DOD end-use monitoring that we identified while conducting work for this and prior reports.)

· Routine end-use monitoring. SCO officials must conduct at least one routine check of a U.S.-provided defense article each quarter. These checks are conducted during the course of other official duties. For example, during one of our visits to foreign military installations, SCO officials observed U.S.-provided helicopters undergoing maintenance. Following the visit, SCO officials completed a routine end-use monitoring report, which includes a question asking whether a potential violation was reported to State, DSCA, and the combatant command. The officials noted in the report that they had not identified or reported a potential violation. In another instance, a SCO official identified a potential violation after noticing markings on U.S-provided vehicles that indicated the foreign partner may have transferred the vehicles to a unit not authorized by the U.S. government, according to SCO documentation.

· Enhanced end-use monitoring. Enhanced end-use monitoring requires annual physical security assessments and inventory checks by serial number. During an inventory check, SCO officials may identify violations such as insufficient security measures at storage facilities, the loss of defense articles, or tampering with articles. For example, officials of one SCO told us that a SCO official conducting an inventory check had identified the loss of some night vision devices (see fig. 2).

Figure 2: Security Cooperation Organization Officials Conducting Enhanced End-Use Monitoring Inspection of Night Vision Devices

Another SCO official told us that when he conducted inventory checks of missiles, he always checked the seals on the missile storage containers (see fig. 3). If the seals on the container were broken, he would check the missile for evidence of tampering.

In addition to learning of potential violations through SCOs’ end-use monitoring, State and DSCA may obtain such information from news and social media, foreign partners’ self-reporting, DSCA compliance assessment visits, or other U.S. officials. For example:

· News and social media. According to the DSCA tracker, State or DSCA became aware of 12 potential violations through news sources or social media, including CNN, Time, The New York Times, and X (formerly Twitter).

· Foreign partners. Foreign partners can self-report potential violations. In 15 incidents, SCOs received reports from foreign partners about loss of articles, storage issues, and modifications of articles, according to the DSCA tracker. However, some foreign partners may be more willing or able than others to self-report potential violations, according to SCO officials.

· DSCA compliance assessment visits. DSCA may identify potential violations during compliance assessment visits. DSCA conducts these visits to assess SCOs’ compliance with end-use monitoring requirements and foreign partners’ compliance with requirements in the letters of offer and acceptance. In four instances DSCA officials identified potential third-party transfers to unauthorized maintenance facilities, problems with storage security, or potential unauthorized use of articles, according to the DSCA tracker.

· Other U.S. officials. Other U.S. officials can also provide information to State and DSCA about potential violations. In two instances, U.S. officials reported potential violations identified through intelligence channels, according to the DSCA tracker. Additionally, a military department program manager, a contractor, and a Defense Technology Security Agency official have notified DSCA of potential violations.

While State Does Not Track Potential Violations, DSCA Has Recorded Many Incidents

Although PM/RSAT officials said they do not systematically track potential violations, as of February 2025 DSCA had maintained information about more than 150 incidents in its tracker, which it shares with PM/RSAT.

PM/RSAT officials told us that, in response to a recommendation we made in 2022, they are developing a mechanism, with associated guidance, that will allow PM/RSAT to track information related to investigations of potential violations.[15] According to PM/RSAT officials, they plan for this mechanism to include information about the status of investigations, resolution of potential violations, and any reporting of potential violations to Congress. PM/RSAT officials told us that the development of this mechanism and associated guidance has been delayed due to competing responsibilities.

One PM/RSAT official said that he only became aware of some incidents by reviewing DSCA’s tracker. However, an official said that not all PM/RSAT personnel responsible for investigating potential violations had access to the PM/RSAT e-mail account for information about potential violations.

As of February 2025, DSCA’s tracker included 158 incidents, although it does not include every incident reported to State by other sources. Most of these incidents were reported to State from 2019 through 2024. DSCA officials said that when they receive notice of a potential violation, they record it in the tracker and share the information with State.[16] PM/RSAT officials confirmed that they have access to DSCA’s tracker. In addition, PM/RSAT and DSCA officials said that they hold routine meetings to discuss updates on incidents listed in the tracker. During these meetings, PM/RSAT officials can notify DSCA of potential violations they have learned about from other sources. However, State officials cannot add incidents to DSCA’s tracker. Both PM/RSAT and DSCA officials told us that DSCA’s tracker is not a complete record of reported incidents. We identified three incidents that other sources had reported directly to PM/RSAT and that were not listed in DSCA’s tracker.

State Has Not Defined Types of Incidents That Warrant Its Attention

State’s expectations of the types of incidents that warrant its attention and of when it should be informed are unclear because PM/RSAT has not provided guidance defining its expectations. DOD’s Security Assistance Management Manual says that all potential purpose, transfer, and security violations must be reported immediately to State and DSCA. (Fig. 4 shows hypothetical examples of such violations.)

PM/RSAT officials said that they do not expect to hear about every potential infraction, such as every incident related to combat losses, but officials’ views of what should be reported varied. A PM/RSAT official said that if a combat loss occurred due to the carelessness of the foreign partner, the loss could be considered a violation. Additionally, PM/RSAT officials provided mixed perspectives on whether SCOs should inform them of a foreign partner’s noncompliance with security requirements at facilities storing weapons that require enhanced end-use monitoring. One PM/RSAT official thought that SCOs should report any noncompliance with the security requirements; another PM/RSAT official thought that some security issues—such as a hole in a facility’s fencing—could be addressed by the SCO and would not need to be reported to State.

DOD guidance includes some general guidelines on what should be reported. The Security Assistance Management Manual states that SCO officials must notify State and DSCA of all potential unauthorized access, unauthorized transfers, and security violations or known equipment losses. The manual also says that SCO officials shall report “any indication that U.S. origin defense articles are being used for unauthorized purposes, are being tampered with or reverse engineered, or are accessible by persons who are not officers, employees, or agencies of the recipient government.” Other DSCA guidance for completing enhanced end-use monitoring checklists cites two specific examples of expectations or thresholds for reporting potential violations: (1) if a missile was destroyed without approval and (2) if a missile guidance control unit is missing and the foreign partner was not authorized to remove or replace it.

However, PM/RSAT has not documented its expectations in guidance or communicated them to officials in country, on whom PM/RSAT relies to identify potential violations. A PM/RSAT official said that when meeting in person with SCO officials, PM/RSAT officials may describe the types of violations that they expect to be informed of. However, the official could not provide any details of what such a discussion might entail. PM/RSAT officials noted that they have competing responsibilities, limiting their time for developing guidance related to potential end-use violations.

Without clear guidance from State, DSCA and SCOs have relied on professional judgement to determine what to report and when to report it. For example:

· Transfer agreements can establish physical security requirements for defense articles, and any deviation from these requirements could be a violation. However, SCO officials in four countries told us that if they observed an issue with the foreign partner’s security measures at a facility—such as a storage door without the required type of lock—they might first work with the partner to address the issue rather than immediately reporting it as a potential violation. In addition, according to a DOD official, SCO officials might not inform State when night vision devices are not properly secured, because the SCO officials may be concerned that their reporting it as a potential violation might disrupt the bilateral relationship.

· The Security Assistance Management Manual requires that State be notified immediately about potential violations. However, DSCA and SCO officials have sometimes conducted initial fact finding on the details of an incident before reporting it to State. For example, in one instance, a potential violation was brought to the geographic combatant command’s attention and, shortly thereafter, to DSCA. DSCA, the combatant command, and the SCO corresponded to uncover more information about the incident before notifying State. As a result, DSCA did not notify State until more than a year after the potential violation was initially identified. According to DSCA’s tracker, most incidents were reported to both DSCA and PM/RSAT around the same time. However, 17 incidents were reported to PM/RSAT more than a month after they were reported to DSCA.

Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that management should define objectives clearly to enable the identification of risks and define risk tolerances and should externally communicate the necessary information to achieve the entity’s objectives.[17] According to the Foreign Affairs Manual, State must maintain effective systems of internal controls that incorporate GAO internal control standards.[18]

Unless State provides guidance defining what types of incidents it expects to be informed of and when it expects to be informed, DSCA, SCO, and other U.S. officials may not have a clear, consistent, and timely understanding of the parameters for exercising professional judgment. This may reduce or delay reporting or result in their informing State of irrelevant incidents. Moreover, if relevant incidents are not reported, State cannot ensure that it is informed of incidents it may need to investigate and has an accurate and up-to-date understanding of a foreign partner’s history of compliance with arms transfer agreements.

State Investigates Potential Violations Inconsistently and Does Not Make Their Status and Findings Clear

State Investigates Potential Violations Inconsistently

PM/RSAT officials stated that they use an ad hoc approach to investigate potential violations, in part because State has not established a process or time frames for its investigations. According to a State fact sheet, the U.S. government takes all allegations of diversion or unauthorized use of defense articles seriously and engages with partners at all levels to ensure adherence to end-use agreements.[19] Furthermore, according to the factsheet, once notified of a potential violation, State aims to promptly gather information to validate the report, assess whether a violation occurred, and determine the actions the U.S. government will take to prevent a recurrence. Yet, of the 53 open investigations on DSCA’s tracker, 23 were reported to PM/RSAT more than 3 years ago.

PM/RSAT officials described some steps they take when investigating incidents. According to the officials, they typically gather information about the incident by contacting the relevant SCO, State’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research, or other U.S. government agencies. The officials also said they consult with State’s Office of the Legal Adviser regarding the circumstances of the investigation.

However, according to PM/RSAT officials, they do not have a consistent method for investigating incidents. As a result, PM/RSAT officials design a different approach for each case. For example:

· Regarding a January 2023 incident involving the transfer of military vehicles between units within a foreign partner’s government, PM/RSAT requested additional information from the SCO, reviewed the transfer agreements, and consulted with State’s Office of the Legal Adviser. By March 2023, PM/RSAT had determined that the incident was not a violation but should be addressed. As of April 2025, PM/RSAT and the SCO were continuing to work with the foreign partner to resolve it.

· Regarding an April 2022 incident, according to DSCA’s tracker, PM/RSAT was informed that U.S. articles, including an anti-tank missile, had been obtained by an adversary. DSCA’s tracker showed that the incident was reported to State in 2022 and was closed in 2024. However, although the tracker included the missile’s serial number, the responsible PM/RSAT official told us that he had not investigated the incident.

· Regarding a February 2020 incident, the responsible PM/RSAT official, whom we interviewed in March 2025, had no recollection of the alleged transfer of a U.S. military vehicle to a terrorist organization. According to the DSCA tracker, the incident was reported to DSCA and PM/RSAT and remained open as of February 2025. The PM/RSAT official told us that he would need more information, likely from DSCA or the SCO, about the article’s procurement to determine whether he should gather additional information.

|

State’s Process for Responding to Other Types of Incidents Involving U.S. Defense Articles State has previously assigned responsibility and developed guidance for gathering information about other types of incidents involving U.S.-provided defense articles. Specifically, in 2023, State implemented the Civilian Harm Incident Response Guidance and reporting process. This process pertains when State receives a report of civilian harm that may have involved the use of U.S.-provided defense articles by a foreign security force. State’s process includes three stages: (1) incident analysis, which includes determining if a U.S. article was involved; (2) policy impact assessment, which includes assessing for potential violations; and (3) determining necessary reporting and responsive actions. (See GAO‑22‑105988 and GAO‑25‑107077.) Source: GAO. | GAO‑25‑107622 |

According to PM/RSAT officials, State has no guidance outlining required actions or setting time frames for investigations. State’s Foreign Affairs Manual calls for maintaining effective systems of internal controls that incorporate GAO internal control standards. Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that management should implement control activities through policies.[20] For example, with guidance from management, each unit should determine, on the basis of the objectives and related risks, the policies and day-to-day procedures necessary to operate. For other types of incidents involving U.S.-provided defense articles, State has assigned responsibility and developed guidance for gathering information.

Further, although PM/RSAT officials said they have investigated incidents for several years, State’s Foreign Affairs Manual does not assign this responsibility. According to PM/RSAT officials, PM/RSAT has investigated incidents since approximately 2019, when the Bureau of Political-Military Affairs directed it to investigate and report to Congress regarding violations of AECA section 3. Previously, another bureau office, the Office of Defense Trade Controls Compliance, was assigned this responsibility. In July 2024, the Foreign Affairs Manual still designated the Office of Defense Trade Controls Compliance as responsible for reporting to Congress violations of AECA section 3. The manual was subsequently revised to eliminate this provision. However, as of September 2025, the manual does not designate any office as responsible for investigating AECA section 3 violations or reporting them to Congress. Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that management should assign responsibility to achieve the entity’s objectives.[21]

Without guidance establishing required actions and time frames for investigating incidents, PM/RSAT officials may not consistently and promptly gather evidence, confirm whether a violation occurred, and determine whether follow-up actions could prevent another violation. Further, until State updates the Foreign Affairs Manual to assign PM/RSAT the responsibility for investigating AECA section 3 violations, it cannot be assured that PM/RSAT officials will prioritize this responsibility appropriately. Timely investigations into whether a foreign partner has violated transfer agreements are important to inform deliberations about future arms transfers. For example, as of February 2025, PM/RSAT had not completed its investigation of a foreign partner’s potential tampering with a U.S.-provided weapon in November 2023, and the U.S. government was considering providing the foreign partner with similar additional weapons.

Status and Findings of State’s Investigations Are Unclear and Not Shared with DSCA and SCOs

Status and Findings of State’s Investigations Are Often Unclear

Although PM/RSAT officials told us that they look into every incident of which they are notified, they could not readily provide the number of incidents reviewed from 2019 through 2024, the status of those incidents, or the findings of their investigations. According to officials, although DSCA’s potential violations tracker is incomplete, it contains the best available information about the incidents communicated to State. As of February 2025, DSCA’s tracker included 105 closed cases and 53 open cases, but PM/RSAT officials were unable to provide the number of these incidents they had reviewed.

Although PM/RSAT officials cannot add incidents to DSCA’s tracker, they have the ability to update it with information about the status or findings of their investigations. However, they do not always do so. As of February 2025, the tracker included information about the status of PM/RSAT’s open investigations or the findings of completed investigations for about half of the incidents listed (see fig. 5).

Figure 5: Status or Findings of State Investigations Are Missing for Many Incidents That May Have Violated Legal Requirements for U.S. Arms Transfers

Note: The data shown reflect State Department information

about 158 incidents recorded in a Defense Security Cooperation Agency system as

of February 2025.

For 82 incidents, the tracker included some information about the status or findings of PM/RSAT’s investigations. It showed 20 of those incidents as open investigations and provided some information about their status, such as whether PM/RSAT had requested information from the responsible SCO. The tracker showed 62 investigations as completed and provided some information about PM/RSAT’s findings, such as corrective actions taken by the foreign partner. However, for 30 of the completed investigations, the tracker did not include clear findings, such as whether State had determined that a violation occurred.

For 76 incidents, the tracker included no information about the status or findings of PM/RSAT’s investigations. It showed 33 of the investigations as open but did not indicate their status to help officials understand whether PM/RSAT needed more information. The tracker showed the remaining 43 investigations as completed but did not include information about PM/RSAT’s findings of whether a violation had occurred. Further, in two instances where PM/RSAT confirmed a violation, PM/RSAT officials had not updated the DSCA tracker to include State’s findings.

For the 12 foreign partners involved in the 12 incidents we selected, U.S. officials approved at least $46 billion in new arms sales while the incidents were under investigation. However, when we asked for documentation of investigations of the 12 incidents we had selected for our review, PM/RSAT was unable to provide any documentation of findings or actions related to 10 of the incidents. Officials told us that they do not document their findings for most completed investigations. Documentation PM/RSAT provided for two of the 12 incidents showed the following:

· For one of the 12 incidents, the U.S. embassy had reported that an unauthorized non-state actor was using U.S.-provided vehicles. PM/RSAT told us they determined that the incident was a violation. PM/RSAT documented its determination in a memorandum approved by the Under Secretary for Arms Control and International Security.

· For another of the 12 incidents, DSCA reported that an aircraft was potentially being used for unauthorized purposes. PM/RSAT officials told us they had determined that the incident was not a violation because the letter of offer and acceptance had not clearly defined limitations on the use of the aircraft. PM/RSAT documented its determination in a diplomatic cable to the U.S. embassy instructing the embassy to take steps to clarify the requirements.

PM/RSAT also provided documentation of investigations of two incidents unrelated to the 12 we selected. PM/RSAT identified one of these incidents as a transfer violation, according to a State memorandum. As a result of the violation, State decided to pause security assistance to the foreign partner and reprogram millions of unobligated dollars it had planned to provide to that country. PM/RSAT identified a second incident as a security violation, according to a State memorandum and a letter to the foreign partner. PM/RSAT confirmed that the partner had relocated and operated U.S.-provided fighter jets at bases that the U.S. government had not approved.

During the Foreign Military Sales process, U.S. embassy officials are required to assess a foreign partner’s ability to use requested defense articles in accordance with their intended purpose and the partner’s ability to safeguard sensitive technology. Moreover, the Foreign Affairs Manual requires bureaus to ensure that personnel create, capture, and preserve records containing adequate and proper documentation of State’s decisions.[22] Without current, reliable, and readily available documentation of the status and findings of PM/RSAT’s investigations, embassy officials may lack awareness of any prior incidents when assessing a partner for future arms sales. As a result, they may approve additional arms transfers to foreign partners that have demonstrated an inability or unwillingness to comply with end-use requirements.

State Does Not Consistently Communicate Investigation Findings to DSCA and SCOs

PM/RSAT does not consistently communicate findings of its investigations to DSCA or SCOs. According to PM/RSAT officials, they do not consistently update the DSCA tracker when they determine whether a violation occurred. As of February 2025, State had entered no information about its findings for 43 of 105 closed cases on DSCA’s tracker. Further, according to State and DOD officials, they do not discuss the findings of every open incident during their regular meetings. Officials in one SCO told us that State had not communicated investigation results to them or updated DSCA’s tracker and that, as a result, they assumed PM/RSAT had determined that the incidents were not violations.

DSCA officials told us that they consider previous violations, among other factors, when deciding where to conduct their annual compliance assessment visits. The Security Assistance Management Manual requires SCOs to monitor confirmed end-use violations and take precautionary measures to reduce the risk of repeat violations. However, PM/RSAT officials told us that communicating results of their investigations to DSCA and SCOs was not always a priority for them because their office balances several other responsibilities.

According to the Foreign Affairs Manual, State must maintain effective systems of internal controls that incorporate GAO internal control standards.[23] Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that management should communicate quality information externally through reporting lines so that external parties can help the entity achieve its objectives and address related risks.[24] In addition, DOD’s Security Assistance Management Manual—which State helped to draft—states that PM/RSAT will communicate its findings to all relevant parties, including DSCA, SCOs, and others.

Without accurate and complete information from PM/RSAT about the status and results of its investigations—in particular, confirmation of violations—DSCA, SCO, and other U.S. officials may not know whether foreign partners have violated purpose, transfer, and security requirements. Several SCO officials we spoke with were unfamiliar with the status of investigations in the countries where they conducted monitoring. As a result, they may not take steps to address violations or implement precautionary measures, such as targeting compliance assessment visits or end-use monitoring, to reduce the risk of recurring violations.

State Has Reported Several End-Use Violations to Congress but Cannot Show It Assessed Other Incidents

State Has Informed Congress of Three End-Use Violations Since 2019

Since January 2019, State has reported three end-use violations to Congress after determining they were violations. The AECA establishes two requirements for when the President must report potential end-use violations to Congress (see table 1). The President delegated this responsibility to the Secretary of State in Executive Order 13637.

Table 1: Selected Provisions for Reporting of Foreign Partner Violations of Transfer Agreements to Congress

|

|

Arms Export Control Act, as amended |

|

|

|

Section 3(c) |

Section 3(e) |

|

Types of violation |

Substantial violation of requirements regarding the purpose, transfer, and security of U.S. defense articles |

Any violation of requirement regarding the transfer of U.S. defense articles |

|

Confirmation of violation |

Not required. The State Department must report any substantial violation that “may have occurred.” |

Required. State must report any unauthorized transfer that “has been made.” |

|

Timing of report |

State must report “promptly upon the receipt of information.” |

State “shall report such information immediately.” |

|

Recipients of report |

Congressional committees |

House Speaker, House Committee on Foreign Affairs, Senate Committee on Foreign Relations |

Source: GAO analysis of 22 U.S.C. §§ 2753 and 2314. | GAO‑25‑107622

Note: The descriptions shown are summaries. The full legal

text can be found in the statutes cited. According to the Arms Export Control

Act (AECA), as amended, a violation is measured as substantial “either in terms

of quantities or in terms of the gravity of the consequences regardless of the

quantities involved.” 22 U.S.C. § 2753. A similar requirement exists within

Section 505 of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, as amended. 22 U.S.C. §

2314.

In Executive Order 13637, the President delegated to the Secretary of State the

responsibility to report to Congress as required in AECA Section 3.

From January 2019 through February 2025, State reported three incidents to Congress informally or formally, after determining that each incident was a violation.

· In one incident, U.S.-provided articles were not appropriately secured. State determined the incident was a nonsubstantial security violation and informally briefed Congress about it, according to a State memorandum.

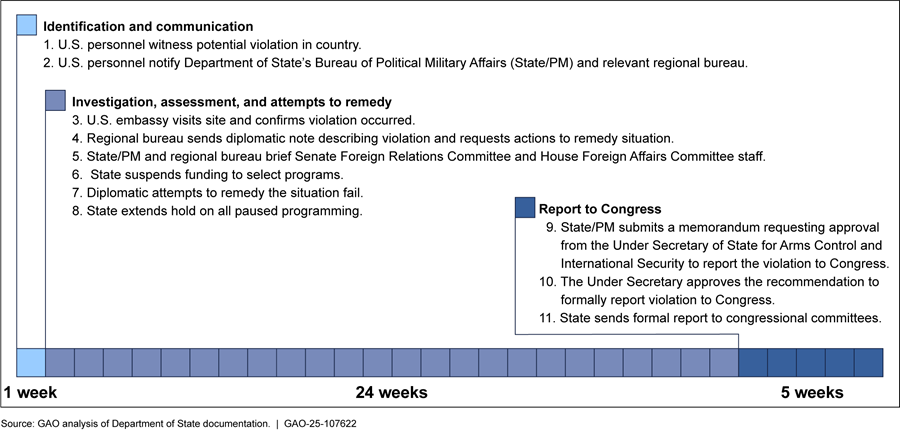

· In two incidents, which occurred in the same country, U.S.-provided vehicles were operated by an adversarial nonstate actor. State determined that both incidents were nonsubstantial transfer violations and submitted formal, written reports to Congress. Figure 6 illustrates the 30-week timeline for State’s making the determination for the second of these incidents and reporting it to Congress.

Figure 6: Timeline of State Department’s Determination and Reporting to Congress of One Transfer Violation

State Cannot Show It Assessed Whether Most Incidents Identified Since 2019 Should Be Reported to Congress

For most of the incidents PM/RSAT has learned of since 2019, it does not have readily available information showing that it assessed whether to report them to Congress or showing any determinations it made. As of February 2025, PM/RSAT officials were aware of more than 150 incidents, including those listed in DSCA’s tracker or reported to PM/RSAT directly by other sources. Officials recalled some deliberations about the 12 incidents we selected for our review. However, PM/RSAT did not have readily available information about any assessments of whether incidents—other than the three violations State has reported to Congress since 2019—met the statutory reporting criteria. Entries in the DSCA tracker noted that some of these incidents may have resulted in the loss of dozens of sensitive items. Moreover, PM/RSAT officials could not confirm that five apparently unauthorized transfers listed in DSCA’s tracker had been reported to Congress.

Further, PM/RSAT did not consistently record its determinations whether to report incidents to Congress. State recorded in memorandums its determinations for the three incidents it has reported to Congress since 2019, which included one of the 12 we had selected. However, PM/RSAT officials were unable to provide documentation of PM/RSAT’s determinations whether the other 11 selected incidents met the statutory reporting criteria. Officials told us that they had struggled to respond to our requests for information, in part because they do not maintain official records. Instead, to find information, they relied on searching email correspondence, which could be lost if an official departed State.

PM/RSAT officials described some steps they might take when assessing whether incidents should be reported to Congress. Although the AECA and FAA require State to report to Congress promptly on receipt of information that a substantial violation related to purpose, transfer, or security may have occurred, PM/RSAT officials said they typically do not consider whether to report to Congress until after confirming that a violation did occur. PM/RSAT officials said that if they collected sufficient evidence of a violation, they would consult with State’s Office of the Legal Adviser regarding the circumstances of the incident. They would then prepare a memo for the Under Secretary for Arms Control and International Security. If the under secretary determined the violation was substantial, State would report it to Congress. Officials said that although determining whether an end-use violation was substantial is a subjective process, they might consider factors such as harm to the United States, effect on foreign relations, safeguarding of technology, and any prior violations by the foreign partner.

However, PM/RSAT officials said they do not have guidance for determining whether an incident should be reported to Congress and for recording these determinations. Specifically, State does not have guidance that clarifies the types of incidents that should be reported to Congress or the steps required to make such a determination, according to PM/RSAT officials.[25] Additionally, officials said there is no formal process for documenting their determinations. Although PM/RSAT officials said that a foreign partner’s history would influence their determination of whether a violation was substantial, the office has not maintained consistent records of past violations.

State’s Foreign Affairs Manual requires bureaus to, among other things, ensure that personnel create, capture, and preserve records containing adequate and proper documentation of State’s decisions.[26] Also, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that (a) management should establish structure, responsibility, and authority that enable the organization to comply with applicable laws and (b) management should implement control activities through policies.[27] For example, each unit, with guidance from management, determines the policies and day-to-day procedures necessary to operate on the basis of the objectives and related risks. In addition, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government calls for management to design control activities to achieve objectives and respond to risks. This should include clearly documenting internal control and all transactions and other significant events in a manner that allows the documentation to be readily available for examination.

Without guidance establishing procedures for determining whether an incident must be reported to Congress and for recording its determinations, State does not have reasonable assurance that it is reporting to Congress in accordance with law. Moreover, PM/RSAT officials may be unaware of previous incidents. As a result, State may fail to inform Congress of incidents that call into question a foreign partner’s willingness and ability to adhere to agreements or safeguard U.S. technology. Consequently, Congress may not have information that would support its oversight of U.S. arms transfers to foreign partners, including the possibility of legislation to prohibit future transfers to foreign partners that violated agreements.

Conclusions

Providing U.S. defense articles and services to foreign partners can enhance U.S. national security. However, this assistance may compromise U.S. military and technological advantages if foreign partners fail to keep the defense articles appropriately secure or if they transfer them to U.S. adversaries. Moreover, the U.S. government maintains a foreign policy interest in partners’ uses of the articles or services. For these reasons, foreign partners must agree to safeguard U.S. technology and to use the articles and services for only authorized purposes. Knowledge that a partner has violated those requirements informs U.S. government decisions whether to supply the partner with additional defense articles and services.

Yet not all violations pose the same risks to the United States. For example, neglecting to use the specified door lock would violate agreed-on security measures but likely would not present the same risk as transferring weapons to unauthorized military units. However, without guidance from State, DSCA and SCO officials do not have a clear understanding of what types of incidents warrant PM/RSAT’s attention and when it expects to be informed. As a result, State may not have an accurate and up-to-date understanding of foreign partners’ compliance history and cannot be assured that U.S. defense articles are used only for authorized purposes, remain in the custody of the appropriate foreign military organization, and are properly secured.

Further, PM/RSAT conducts investigations of potential violations on an ad hoc basis. Unless State provides guidance establishing required actions and timeframes for investigating incidents, it will not have reasonable assurance that its staff will consistently and promptly gather evidence, verify violations, and determine any actions needed to prevent their recurrence. Also, until it designates, in the Foreign Affairs Manual, PM/RSAT as responsible for investigating potential violations, State will not have reasonable assurance that PM/RSAT staff will prioritize this responsibility appropriately and investigate each potentially substantial violation.

In addition, without readily available documentation of the status and findings of PM/RSAT’s investigations, U.S. officials may not know about prior incidents when assessing a partner for future arms sales. As a result, they may approve additional arms transfers to foreign partners without awareness of foreign partners’ past practices, such as noncompliance with bilateral transfer agreements.

Moreover, unless PM/RSAT communicates the status and results of its investigations—in particular, confirmation that a violation has occurred—to DSCA, SCOs, and other U.S. stakeholders, they may not take steps to address violations or implement measures to reduce the risk of repeat violations.

Finally, without guidance establishing procedures for determining whether to report violations to Congress and for documenting each determination, PM/RSAT cannot ensure that it is reporting to Congress consistently, in accordance with the law, potential and actual violations of bilateral arms transfer agreements. As a result, Congress may not have access to information needed to support its oversight of U.S. security assistance.

Recommendations

We are making the following six recommendations to the Secretary of State:

The Secretary of State should ensure that the Director of PM/RSAT, in consultation with DOD, provides guidance to officials at DSCA and relevant embassies defining the types of incidents that qualify as potential violations of arms transfer agreements and establishing timelines for informing PM/RSAT about potential violations. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of State should ensure that the Director of PM/RSAT, in consultation with DOD, develops guidance establishing required actions and timeframes for investigating potential violations of arms transfer agreements. (Recommendation 2)

The Secretary of State should ensure that the Director of PM/RSAT updates the Foreign Affairs Manual to ensure that responsibility for investigating potential violations of arms transfer agreements is assigned as appropriate and documented in policy. (Recommendation 3)

The Secretary of State should ensure that the Director of PM/RSAT documents the status and findings of its investigations related to potential violations of arms transfer agreements. (Recommendation 4)

The Secretary of State should ensure that the Director of PM/RSAT consistently communicates to DSCA, SCOs, and other agency stakeholders the status and findings of its investigations, including determinations of whether reported incidents constituted violations of arms transfer agreements. (Recommendation 5)

The Secretary of State should ensure that the Director of PM/RSAT develops guidance establishing procedures for determining whether, in accordance with AECA sections 3(c) and 3(e), State should report an incident to Congress and for documenting these determinations. (Recommendation 6)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to the Departments of State and Defense for review and comment. State provided written comments that we have reproduced in appendix I. State concurred with our recommendations and acknowledged that it would be taking steps to implement them. State and DOD also provided technical comments that we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretaries of Defense and State, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at ReynoldsJ@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix II.

James A. Reynolds

Acting Director, International Affairs and Trade

List of Committees

The Honorable Roger F. Wicker

Chairman

The Honorable Jack Reed

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

United States Senate

The Honorable James E. Risch

Chairman

The Honorable Jeanne Shaheen

Ranking Member

Committee on Foreign Relations

United States Senate

The Honorable Mike Rogers

Chairman

The Honorable Adam Smith

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

House of Representatives

The Honorable Brian Mast

Chairman

The Honorable Gregory Meeks

Ranking Member

Committee on Foreign Affairs

House of Representatives

GAO Contact

James A. Reynolds, ReynoldsJ@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Miriam Carroll Fenton (Assistant Director), Brandon L. Hunt (Analyst in Charge), Naina Azimov, Neil Doherty, Mark Dowling, Jeffrey Larson, Reid Lowe, Amarica Rafanelli, and Cameron Cheam Shapiro made key contributions to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]22 U.S.C. §§ 2314(d)(2)(B), 2753(c)(2), and 2753(e).

[2]See Executive Order 12163, “Administration of Foreign Assistance and Related Functions,” 44 Fed. Reg. 56673 (Sept. 29, 1979) as amended and set forth as a note to 22 U.S.C. § 2381 and Executive Order 13637, “Administration of Reformed Export Controls,” 78 Fed. Reg. 16129 (June 13, 2013) set forth as a note to 22 U.S.C. § 2751.

[3]House Report 118-301 is the conference report accompanying the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024. Pub. L. No. 118-31, 137 Stat. 136 (2023).

[4]Foreign partners can also obtain U.S. defense articles and services through direct commercial sales instead of government-to-government transfers. U.S. companies participating in these sales obtain commercial export licenses from State, allowing them to negotiate with, and sell directly to, foreign partners. See GAO, Export Controls: State Needs to Improve Compliance Data to Enhance Oversight of Defense Services, GAO‑23‑106379 (Washington, DC: Feb. 6, 2023).

[5]Statutory authority for transfers through DOD’s Building Partner Capacity programs includes the authority to build the capacity of foreign security forces, codified at 10 U.S.C. § 333.

[6]GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO‑14‑704G (Washington, DC: September 2014). Principle 3 calls for assigning responsibility to achieve objectives. Principle 6 states that management should define objectives clearly to enable the identification of risks and define risk tolerances. Principle 10 states that management should design controls activities to achieve objectives and respond to risks. Principle 12 states that management should implement control activities through policies. Principle 15 calls for external communication of necessary quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives.

[7]See 22 U.S.C. § ch.39.

[8]The AECA sets forth the process by which the President or Congress can deem a foreign partner ineligible. The act further sets forth procedures under which foreign partners may remain eligible for cash sales or deliveries pursuant to previous sales if the President certifies that termination of eligibility would have a significant adverse effect on U.S. security. A foreign partner remains ineligible until the President determines that the violation has ceased and the country concerned has given assurances satisfactory to the President that such a violation will not recur. See 22 U.S.C. § 2753(c).

[9]22 U.S.C. § 2754.

[10]22 U.S.C. § 2314.

[11]See 22 U.S.C. §§ 2753(c) and 2314(d).

[12]For sales under the AECA or for deliveries pursuant to prior AECA sales, the President may certify that termination of a foreign partner’s eligibility would have a significant adverse effect on U.S. security. However, such certification is not effective if Congress adopts or has adopted a joint resolution finding that the partner country is in substantial violation of a transfer agreement.

[13]According to the Security Assistance Management Manual, a ratified Section 505 agreement must be in place prior to release of appropriated funds to execute a Building Partner Capacity program.

[14]1 FAM 410.

[15]GAO, Northern Triangle: DOD and State Need Improved Policies to Address Equipment Misuse, GAO‑23‑105856 (Washington, DC: Nov. 2, 2022). In October 2024, State officials told us that they were updating guidance for recording and tracking allegations of misuse.

[16]In 2022, we recommended that DSCA develop policies outlining how to record and track incidents; DOD did not concur (see GAO‑23‑105856). In September 2024, DOD officials stated that they had these policies in guidance. However, we maintain that to ensure that allegations of misuse are recorded and tracked, DOD needs to develop clearer policies describing how and when DSCA officials should record such allegations. During our current review, we found that DSCA’s regional program managers enter information into DSCA’s tracker differently and that, as a result, it is difficult to identify trends among potential violations.

[18]2 FAM 021.1.c.

[19]“End-Use Monitoring of U.S.-Origin Defense Articles,” Department of State, January 20, 2025, https://www.state.gov/end‑use‑monitoring‑of‑u‑s‑origin‑defense‑articles/.

[22]5 FAM 418.8.

[23]2 FAM 021.1.c.

[25]For one of the three documented violations that State reported to Congress, PM/RSAT attached a 1993 memorandum that outlines procedures for providing information to the Under Secretary for Arms Control and International Security. However, the other two documented cases did not reference the 1993 memo and PM/RSAT officials whom we interviewed said they were not aware of it.

[26]5 FAM 418.8.

[27]GAO‑14‑704G. According to the Foreign Affairs Manual, State will implement internal controls (2 FAM 021c).