FEDERAL RULEMAKING

Potential Effects of Legislation to Offset Direct Spending Resulting from Regulations

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Yvonne D. Jones at jonesy@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107642, a report to congressional requesters

Potential Effects of Legislation to Offset Direct Spending Resulting from Regulations

Why GAO Did This Study

The Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023, enacted on June 3, 2023, reinstated certain administrative PAYGO requirements, which then expired on December 31, 2024. January 2021 to June 2023 was the only period between 2005 and 2024 when administrative PAYGO requirements did not exist in any form.

GAO was asked to review the effects of the administrative PAYGO provisions of the 2023 act. This report reviews (1) how many rules published between January 20, 2021, and June 3, 2023, could have been subject to the requirements of the act; (2) the estimated costs of the 28 major rules published in the first 5 months of the act; and (3) OMB’s process for monitoring agencies’ compliance with administrative PAYGO requirements under the act.

For the first objective, GAO analyzed rules and related documentation to determine whether they would have been subject to the act. When additional information was needed, GAO contacted the relevant agency to request that information. For the second objective, GAO reviewed economic analyses and summarized the federal cost estimates for each of the 28 major rules. For the third objective, GAO reviewed relevant laws, executive orders, and OMB guidance. GAO also interviewed OMB staff about their process for ensuring compliance with administrative PAYGO requirements.

What GAO Found

For most of the last 20 years, regulations issued by federal agencies have been subject to some version of administrative pay-as-you-go (PAYGO) requirements. Agencies were required to propose potential offsets to certain estimated increases in direct spending (also called mandatory spending) resulting from regulatory actions. In January 2021, President Biden revoked these requirements. In June 2023, the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023 reinstated similar administrative PAYGO requirements. GAO found that four rules published during the time frame when no requirements were in place could have been subject to offset reporting requirements had they been in place at the time. Most rules estimated increased federal costs of less than $1 billion in the first 10 years and therefore would have been exempt.

GAO’s Analysis of Rules That Could Have Been Subject to 2023 Administrative Pay-As-You-Go Provisions

GAO reviewed the 28 major rules published in the first 5 months following enactment of the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023. GAO found the range of federal costs agencies estimated to be $0 to $156 billion, with half of the 28 rules estimating no federal cost. According to Office of Management and Budget (OMB) staff, none of the 28 rules were ultimately subject to administrative PAYGO requirements because they did not increase direct spending above the law’s thresholds or they received a waiver.

OMB issued guidance and reviewed agency compliance with administrative PAYGO requirements through its established regulatory review process. OMB was responsible for assisting agencies in determining how the act applied to a rule, if a rule might be exempt or eligible for a waiver, and the required reporting.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

CMS |

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services |

|

CRA |

Congressional Review Act |

|

IRS |

Internal Revenue Service |

|

OIRA |

Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs |

|

OMB |

Office of Management and Budget |

|

PAYGO |

Pay-As-You-Go |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

May 15, 2025

The Honorable Jodey Arrington

Chairman

Committee on the Budget

House of Representatives

The Honorable Jack Bergman

Chair of the Oversight Task Force

Committee on the Budget

House of Representatives

For most of the last 20 years, regulations issued by the federal government have been subject to some version of administrative pay-as-you-go (PAYGO) requirements. Starting with an Office of Management and Budget (OMB) memorandum in 2005, these requirements have directed agencies to propose potential offsets to increases in certain types of spending that result from regulatory actions. On January 20, 2021, President Biden revoked prior administrative PAYGO requirements.[1] The Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023, enacted on June 3, 2023, reinstated certain administrative PAYGO requirements.[2] Those requirements expired on December 31, 2024. January 2021 to June 2023 was the only period between 2005 and 2024 when administrative PAYGO requirements did not exist in any form.

You asked us to review the effects of the administrative PAYGO provisions of the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023. This report examines (1) how many rules published between January 20, 2021, and the enactment of the act could have been subject to requirements of the PAYGO provision of that act, had it been in effect at the time; (2) the estimated costs of the 28 major rules published in the first 5 months after the enactment of the act; and (3) OMB’s process for monitoring agencies’ compliance with administrative PAYGO requirements under the act.

To address the first objective, we used our Congressional Review Act database to identify 153 major rules published between January 20, 2021, and June 3, 2023.[3] We then reviewed each rule and answered a series of questions to determine whether those rules could have been subject to the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023’s PAYGO requirements.[4] Because those PAYGO requirements were not in place when agencies published the regulations we reviewed, not all of the rules contained the information needed to determine whether a rule would have been subject to the PAYGO requirements. For rules without this information, we contacted the agencies that published them to ask for additional information to the extent it was available.[5] We did not review any rules from independent regulatory agencies because they were exempt from the act.[6]

To address the second objective, we reviewed the economic analyses of the 28 major rules published between June 3, 2023, and November 3, 2023, that we had identified in our November 2023 report on administrative PAYGO.[7] We summarized the estimated costs to the federal government of those 28 rules. For the purposes of this report, “costs” can include costs, transfers (when money is shifted from one party to another), or other monetized effects of rules excluding benefits. Some rules created costs to both the federal government and to other parties.

To address the third objective, we reviewed the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023, Executive Orders 12866 and 14094 on regulatory planning and review, and OMB’s guidance on administrative PAYGO.[8] We also interviewed OMB staff about their role in the administrative PAYGO process. Appendix I provides additional information on our scope and methodology for each of our three objectives.

We conducted this performance audit from June 2024 to May 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Federal regulation is a tool of government that agencies use to implement law. Agencies issue regulations to achieve public policy goals such as ensuring that workplaces, air travel, food, and drugs are safe; that the nation’s air, water, and land are not polluted; and that the appropriate amount of taxes is collected. Given the sizable benefits and costs of these regulations, Congress and presidents have taken a number of actions to refine and reform the regulatory process during the past few decades. Among the goals of such initiatives are enhancing oversight of rulemaking by Congress and the president, promoting greater transparency and participation in the process, and reducing regulatory burdens on affected parties.

Regulations can impose costs on both the public and the federal government, including effects on direct spending, also called mandatory spending.[9] In recent years, direct spending represented about two-thirds of all federal spending. Direct spending includes spending for certain entitlement programs such as Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid, as well as certain other payments to individuals, businesses, and state and local governments. Regulations can affect direct spending by, for example, adjusting eligibility criteria or payment requirements for those types of programs. Regulations affecting direct spending are only valid to the extent that they are consistent with the underlying statutory authority.

In 2005, the George W. Bush administration issued a memorandum that directed agencies proposing to increase direct spending through regulation or other actions to also propose actions to “comparably reduce” direct spending.[10] In 2009, the Obama administration said it would continue implementing this policy.[11] In 2019, the Trump administration issued Executive Order 13893 establishing similar requirements.[12] During the Bush and Obama administrations, OMB generally implemented administrative PAYGO requirements through the budget process rather than through OMB’s regulatory review process. Specifically, agencies were required to include in their budget requests (1) a list of planned administrative actions, including regulations, that would increase direct spending; and (2) a list of proposed actions to offset those increases. During the first Trump administration, agencies were required to submit proposed administrative actions and proposed offsets to OMB for review.

On January 20, 2021, the Biden administration revoked Executive Order 13893, ending administrative PAYGO requirements. The administration stated that its goal for revoking the order was to equip agencies with “the flexibility to use robust regulatory action to address national priorities.”[13]

The Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023 reinstated administrative PAYGO requirements on June 3, 2023. The act included administrative PAYGO provisions that required federal agencies to identify increases in direct spending that may result from federal rulemaking.[14] For final rules that expected to increase direct spending above certain thresholds, agencies were to identify one or more additional agency actions that could offset the direct spending associated with the rulemaking. Alternatively, agencies could request and receive a waiver from OMB.[15] The act did not require agencies to move forward with, or ultimately implement, proposed offsets. These requirements expired on December 31, 2024.[16]

We previously reported on the implementation of the act’s administrative PAYGO provisions in November 2023.[17] In that report, we discussed OMB’s guidance to agencies for implementing the law. We also identified 28 major rules that were issued in the first 5 months after the law’s enactment. We reported that OMB had determined that all 28 rules would either not result in enough direct spending to be subject to administrative PAYGO requirements or that the agencies had received a waiver.[18]

Few Rules Likely Would Have Triggered Administrative PAYGO Reporting During Period Without Requirements

Most rules we reviewed that were published between January 2021 and June 2023 were estimated to increase federal costs by less than $1 billion over the 10-year time frame. Therefore, they likely would have been exempt from the Fiscal Responsibility Act’s administrative PAYGO requirements had those requirements been in place at the time. When those requirements were in effect (from June 3, 2023, to December 31, 2024), rules issued by covered agencies were subject to administrative PAYGO requirements unless OMB provided a waiver or the rule was exempt.[19] Rules were subject to the requirements if they were estimated to increase direct spending by at least $1 billion in the first 10 years and by at least $100 million in each of those first 10 years, among other things. Rules were exempt if they did not meet one or both of those thresholds.[20]

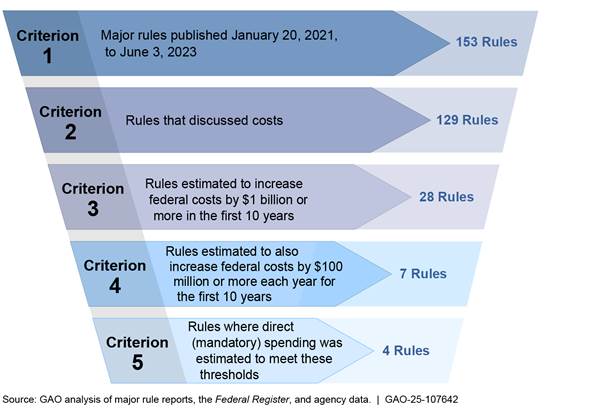

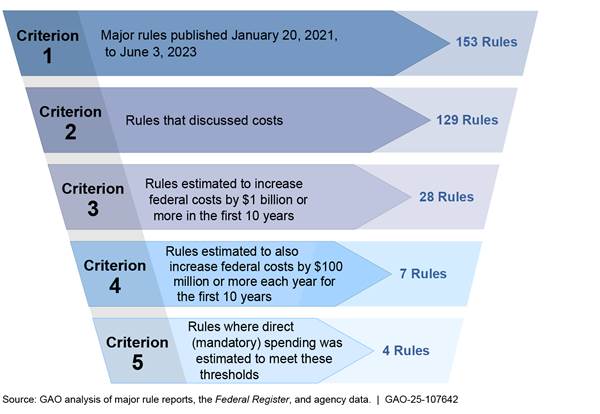

We analyzed rules published between January 2021 and June 2023 based on the act’s administrative PAYGO exemption criteria. While the act’s administrative PAYGO requirements focused on increases in direct spending relative to certain baselines, this information was not readily available for the 153 rules we reviewed. Once we identified these 153 rules, we determined whether these rules discussed costs. For those rules that did, we then applied the exemption criteria (cost thresholds) for these estimated costs. For those rules that met these criteria, we determined whether the estimated costs were direct spending or not. After conducting our analysis, we found that four rules published during the time frame could have been subject to administrative PAYGO requirements. See figure 1 for the results of our analysis.

Figure 1: GAO’s Analysis of Rules That Could Have Been Subject to 2023 Administrative Pay-As-You-Go Provisions

Note: Office of Management and Budget guidance recognizes that there are some instances in which agencies cannot estimate the costs of a rule. Office of Management and Budget, Circular A-4: Regulatory Analysis (Sept. 17, 2003). These totals do not include rules issued by independent regulatory agencies.

Major rules published January 20, 2021, to June 3, 2023. We identified 153 major rules published between January 20, 2021, and June 3, 2023.[21]

Rules that discussed costs. Agencies discussed costs in 129 of the 153 rules. The other 24 rules did not discuss costs, and we were therefore not able to determine whether they could have been subject to administrative PAYGO requirements.

OMB guidance recognizes that there are some instances in which agencies cannot estimate the costs of a rule.[22] Eleven of these 24 rules were related to the COVID-19 pandemic and agencies determined it was impractical or not in the public interest to delay rule implementation. In other cases, rules were announcements. For example, several Department of Agriculture rules we reviewed advertised existing funding opportunities and no new spending resulted from the rules.[23]

Rules increasing federal costs by at least $1 billion in first 10 years. Of the 129 rules that discussed costs, 28 met this criterion. Several of these 28 rules were related to Medicare or other health care programs. For example, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) estimated that one rule revising outpatient and surgical center payment systems, among other actions, would result in more than $1.2 billion in federal costs in the first 10 years.[24]

Another 98 of the 129 rules estimated cost increases to the federal government of less than $1 billion in the first 10 years and therefore did not meet this criterion. As a result, those rules would have been exempt from administrative PAYGO requirements. For example, the Department of Education estimated that its rule on a school-based mental health services grant program would transfer approximately $100 million from the federal government to state and local education agencies, not meeting the $1 billion criterion.[25]

Further, some of these 98 rules were estimated to reduce costs to the federal government. For example, we reviewed a CMS rule that ended a program intended to provide Medicare beneficiaries faster access to breakthrough medical devices. CMS estimated that this rule would reduce transfers from the federal government to Medicare providers.[26]

For the remaining three rules, we were not able to determine whether the rule estimated increased federal costs of at least $1 billion in the first 10 years based on the available information and consultation with the issuing agencies.[27]

Rules increasing federal costs by $100 million each year for first 10 years. Of the 28 rules, seven also met this criterion. For the remaining 21 rules that estimated increased costs of at least $1 billion, 20 estimated increased costs of less than $100 million in at least one of the first 10 years and therefore did not meet this criterion. For one rule, the available analysis, including our consultation with the agency, did not provide the information needed to make a determination.

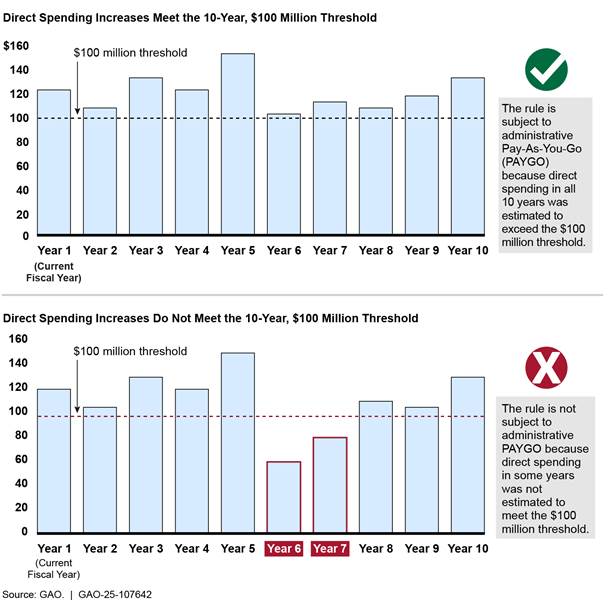

For example, CMS estimated that its 2022 rule revising the Medicare Advantage program and Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit program regulations would result in more than $4 billion in transfers from the federal government over the first 10 years.[28] However, the rule estimated increased federal costs of fewer than $100 million in one of these years and so would have been exempt from administrative PAYGO requirements. Figure 2 shows a hypothetical example of how rules may be exempt from administrative PAYGO requirements if they do not meet this threshold in each of the first 10 years.

Figure 2: Hypothetical Examples of Applicability of Administrative Pay-As-You-Go Requirements in the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023

Rules where direct spending met these thresholds. Of the seven rules estimated to meet both cost thresholds, four involved estimated direct spending above thresholds for exemption, and so could have been subject to administrative PAYGO requirements based on our analysis. For example, the Department of Education’s 2021 rule updating regulations for total and permanent disability student loan discharge for veterans included estimated direct spending above the thresholds for administrative PAYGO exemption.[29]

Of the three remaining rules, two did not involve estimated direct spending above the exemption thresholds. For example, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) published a rule that, among other things, amended eligibility standards for a tax credit providing affordable employer-sponsored healthcare coverage for family members. IRS estimated this rule would reduce federal revenue by more than $1 billion, including by more than $100 million in each of the first 10 years.[30] However, this reduction in revenue is not considered direct spending, and so the rule could have been exempt from administrative PAYGO requirements. For the remaining rule, we were unable to determine the extent to which the estimated cost increases were direct spending based on the available information and after consultation with the agency.

Half of Major Rules Published Shortly After Fiscal Responsibility Act Estimated No Federal Cost

For the 28 major rules published in the first 5 months following enactment of the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023, agencies estimated between $0 and $156 billion in federal costs (see table 1).[31]

Table 1: Number of Rules by Reported Federal Cost Estimate for Major Rules Issued June 3–November 3, 2023

|

Federal Cost Range |

Number of Rules |

Specific Range of Estimates |

|

Rule did not include cost estimates |

3 |

Not applicable |

|

$0 |

14 |

$0 |

|

Greater than zero but less than |

6 |

$5.3 million–$903 million |

|

$1 billion or more |

5 |

$1.4 billion–$156 billion |

Source: GAO analysis of Federal Register data. | GAO-25-107642

Note: For the purposes of this report, “costs” can include costs, transfers, or other monetized effects of rules, excluding benefits. We observed variability in how agencies presented cost estimates. When agencies presented multiple estimates—such as estimates using both a 3 percent and 7 percent discount rate—we used the smallest estimate for the bottom of the range and the largest estimate for the top of the range. In addition, when agencies presented average annual costs instead of total costs, we calculated the total based on either the number of years of expected costs or 10 years, whichever was smaller.

Rules that did not estimate costs. Three rules did not include cost estimates. For example, one Department of the Treasury rule providing definitions and requirements related to a tax credit did not include a cost analysis.[32] The agency stated in its analysis that tax regulatory actions issued by IRS are not subject to regulatory impact assessment requirements.[33]

Rules that estimated no federal costs. Half of the rules (14 of 28) estimated that there would be no federal cost. For example, one Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) rule removed expired COVID-19 language from a preexisting rule and estimated no federal cost impact of the action.[34] Nine of these rules, however, estimated they would impose non-federal costs, such as costs to manufacturers.[35] For example, one Department of Transportation rule set accessibility standards that would require airlines to retrofit affected aircraft.[36]

Rules that estimated federal costs of less than $1 billion. About one quarter of the rules (six of 28) estimated nonzero costs to the federal government of less than $1 billion. Moreover, four of the six rules estimated federal costs of $355 million of less. For example, a Department of Education rule on the lower end of the range estimated federal costs of $30 million over 10 years to enhance transparency of gainful employment outcomes for higher education programs.[37] In contrast, on the higher end of the range was a rule issued jointly by the Department of Defense, General Services Administration, and National Aeronautics and Space Administration to implement supply chain security measures with an estimated 10-year cost of $903 million.[38]

Rules that estimated federal costs of $1 billion or more. The remaining rules (five of 28) estimated costs over $1 billion. On the low end of estimated costs was a CMS rule to update skilled nursing facility-related rates, with an estimated 1-year cost of $1.4 billion.[39] On the high end of estimated costs was a Department of Education rule amending the terms of income-based student loan repayments, with an estimated 10-year cost of $156 billion.[40]

As we reported in November 2023, according to OMB staff, none of the 28 rules were ultimately subject to administrative PAYGO reporting requirements for various reasons.[41] For example, in the case of the Department of Education rule mentioned above, OMB granted the agency a waiver after staff determined that the rule was necessary for effective program delivery.[42]

OMB Reviewed Administrative PAYGO Compliance Through Its Established Rulemaking Process

OMB’s Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) ensures that rules are consistent with applicable law, the president’s priorities, and the principles set forth in executive orders, among other things.[43] To do this, OIRA reviews certain rules at both the proposed and final rule stages, although it may waive either or both reviews.[44] Part of OIRA’s review included the administrative PAYGO requirements in the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023 during the time the requirements were in effect.[45]

To assist agencies with compliance and as required by the act, OMB issued guidance on September 1, 2023.[46] The guidance instructed agencies on (1) how to evaluate whether a rule was subject to the act’s administrative PAYGO requirements or eligible for a waiver, and (2) reporting required if the act applied to a rule being finalized. OIRA staff said they were not aware of any challenges faced by agencies when implementing the guidance.

Determining the act’s applicability. During the proposed rule stage of the review process, OIRA’s role was to assist agencies in identifying relevant requirements, such as administrative PAYGO. OMB’s guidance instructed agencies to provide a preliminary determination of the act’s applicability to the rule—and the basis for that determination—to OIRA as early as possible. The guidance noted that OMB would review the draft rule and preliminary determination and might ask the agency to submit additional information. According to OIRA staff, they helped agencies identify if additional analyses might be required before the rule was finalized.

During the final rule stage of the review process, OIRA’s role was to assist agencies in confirming and addressing relevant requirements. According to OIRA staff, as agencies finalized their rules, OIRA discussed with them potential direct spending increases and potential offsets. OIRA staff noted they did not independently replicate any agency analyses. Finally, the guidance instructed agencies to inform OIRA in writing about its final administrative PAYGO determinations.

Where applicable, OMB’s role included reviewing requests for and granting waivers, as appropriate, from administrative PAYGO requirements. According to OMB’s guidance, an agency could request a waiver from OIRA if it determined that the rule was necessary for the delivery of essential services, necessary for effective program delivery, or both.[47] OIRA staff told us that they did not use any other criteria or factors beyond those in the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023 to determine whether to grant a waiver. In cases where OMB granted the waiver, that decision was published in the Federal Register.[48] According to OIRA staff, there was no other formal documentation of the waiver decision.

Complying with the act’s requirements. In the event a rule was not exempt and did not receive a waiver, OIRA’s role was to assess the agency’s compliance with the act’s reporting requirements for that rule.[49] To assist with this, OMB’s guidance instructed agencies to consult with OIRA staff prior to addressing the reporting requirements. As summarized in the guidance, the requirements for discretionary rules included a written notice to OIRA of an estimate of the direct spending effects and a proposal to undertake one or more other rules that collectively would reduce direct spending by an amount that would offset the new rule’s increase in direct spending.[50] The guidance informed agencies that OMB would review the proposals to ensure they included sufficient offsets. If the proposal did not, OMB would instruct the agency to resubmit it with sufficient offsets.

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to OMB for review and comment. OMB did not provide comments on the report.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Director of OMB, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at jonesy@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix II.

Yvonne D. Jones

Director, Strategic Issues

This report examines (1) how many rules published between January 20, 2021, and the enactment of the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023[51] could have been subject to the requirements of the administrative pay-as-you-go (PAYGO) provision of that act; (2) the estimated federal costs of the 28 major rules published in the first 5 months after the enactment of the act; and (3) the Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) process for monitoring agencies’ compliance with administrative PAYGO requirements under the act.

To address our first objective, we used our Congressional Review Act (CRA) database to identify 153 major rules published between January 20, 2021, and June 3, 2023. The database contains rules that agencies submit to us, as required by the CRA. The database may not contain all major rules if an agency fails to submit a rule to us as required. We determined that this data source was sufficiently reliable for identifying rules that could have been subject to administrative PAYGO requirements.

We included both final and interim final rules in our analysis.[52] This decision was consistent with OMB’s guidance to agencies on administrative PAYGO implementation, which stated that the act applied to both final and interim final rules.[53] For this reason, where interim final rules were published within our scope, we assessed the information available on the interim final rules and not any information on any subsequently published related final rules.

We reviewed only major rules because any rule with an estimated annual effect on the economy of $100 million or more is considered a major rule under the CRA.[54] Any rule that would be subject to the administrative PAYGO requirements would have at least met that threshold and would therefore be a major rule. We also excluded all rules from independent regulatory agencies because those agencies were not subject to the requirements.

We then reviewed each rule and answered a series of questions to determine whether those rules could have been subject to the administrative PAYGO requirements had those requirements been in place at the time. These questions were:

1. Did the agency discuss costs, transfers, or other monetized impacts?

2. Do the costs to and transfers from the federal government total at least $1 billion over 10 years?

3. Do the costs to and transfers from the federal government total at least $100 million each year for 10 years?

4. Are the costs and transfers referenced in questions 2 and 3 direct spending?

A rule could have been subject to PAYGO requirements if the answer to all these questions was “yes.”

Two analysts coded each rule independently. The two analysts then resolved any differences in how they coded each rule. If they could not reach agreement on how to code a rule, at least one additional analyst reviewed the rule and the rule was coded based on the majority opinion.

Of the 153 rules assessed, the final determination about whether or not to request clarifying information from the agency was made by independent agreement of both coders for 138 (about 90%). For the other 15 rules (about 10%), the independent coders initially disagreed on whether to move forward to the next assessment step, then met to discuss, and ultimately agreed that the rules did not require further assessment.

Our primary sources of information for each rule were our major rule reports and the rules published in the Federal Register. We also reviewed a rule’s regulatory docket if the rule directed us to the docket for additional information and we could not code the rule using only our major rule reports and the Federal Register.

When determining whether costs and transfers imposed by the rule reached the $1 billion and $100 million thresholds, we examined the net effects of the rule. For example, if one part of a rule increased federal costs and another part decreased federal costs, we used the net increase or decrease in federal costs to answer these questions.

In addition, we did not extrapolate information in a rule’s cost-benefit analysis to future years. For example, if a rule estimated increased federal costs for 1 year but did not state how that rule would affect costs beyond 1 year, we only included in our analysis the costs for that one year. This decision was consistent with OMB guidance that an agency’s “analysis should cover a period long enough to encompass all the important benefits and costs likely to result from the rule.”[55]

Because administrative PAYGO requirements were not in place when agencies published the rules we reviewed, some rules did not explicitly include the information needed to determine whether a rule could have been subject to the administrative PAYGO requirements. For the 20 rules without this information, we contacted the agencies that published them to ask for additional information, if available.[56] We did not ask agencies to conduct any new analyses of previously published rules for this report.

To address our second objective, we reviewed the economic analyses of the 28 major rules published between June 3, 2023, and November 3, 2023, that we identified in our November 2023 report on administrative PAYGO.[57] An economist reviewed each rule, and a second economist reviewed that analysis for accuracy. We then summarized the estimated costs to the federal government for those 28 rules. For the purposes of this report, “costs” can include costs, transfers, or other monetized effects of rules, excluding benefits. Some rules created costs to both the federal government and to other parties, although costs to other parties were not relevant for the purposes of our analysis. The rules we reviewed did not always report costs using the same inflation-adjusted formulas or discount rates. We reported the numbers as published in the rules and did not adjust them to make them consistent.

To address our third objective, we reviewed the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023, Executive Order 12866 (as amended by Executive Order 14094) on regulatory planning and review, and OMB’s September 2023 guidance on administrative PAYGO. We also interviewed OMB staff about their role in the administrative PAYGO process.

We conducted this performance audit from June 2024 to May 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

GAO Contact

Yvonne D. Jones, jonesy@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Danielle Novak (Assistant Director), Alexander Ray (Analyst-in-Charge), Michael Bechetti, Kimberly Bohnet, Lilia Chaidez, Jacqueline Chapin, Steven Putansu, Andrew J. Stephens, and Leanne V. Sullivan made key contributions to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

https://www.gao.gov/about/contact-us

[1]President Biden issued Executive Order 13992, which revoked Executive Order 13893, which had established the requirements then in effect. Exec. Order No. 13992, Revocation of Certain Executive Orders Concerning Federal Regulation, 86 Fed. Reg. 7049 (Jan. 25, 2021).

[2]Pub. L. No. 118-5, §§ 261–270, 137 Stat. 10, 31–33 (2023). Similar to prior requirements, the act required agencies to propose offsets to increases in certain types of spending resulting from regulatory actions.

[3]We only reviewed major rules because, among other criteria, any rule with an expected annual effect on the economy of $100 million or more is considered a major rule under the Congressional Review Act. 5 U.S.C. § 804(2). Any rule that would be subject to the administrative PAYGO requirements would have at least met that threshold and would therefore have to be a major rule. Our Congressional Review Act Database can be found at https://www.gao.gov/legal/congressional‑review‑act.

[4]For the purposes of this report, we refer to the requirements in section 263 of the act as administrative PAYGO requirements. We refer to rules issued by covered agencies that were not or would not have been exempt because they had effects below the statutory thresholds as rules that are subject or could have been subject to the administrative PAYGO requirements.

[5]We did not ask agencies to conduct any new analyses of previously promulgated rules for this report.

[6]The act excludes independent regulatory agencies from its definition of agency. Pub. L.

No. 118-5, § 262(2), 137 Stat. at 31; 44 U.S.C. § 3502(5).

[7]GAO, Federal Rulemaking: Status of Actions to Offset Direct Spending from Administrative Rules, GAO‑24‑106968 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 30, 2023).

[8]Pub. L. No. 118-5, §§ 261–270, 137 Stat. at 31–33; Exec. Order No. 12866, Regulatory Planning and Review, 58 Fed. Reg. 51,735 (Oct. 4, 1993); Exec. Order No. 14094, Modernizing Regulatory Review, 88 Fed. Reg. 21,879 (Apr. 11, 2023); and Office of Management and Budget, Guidance for Implementation of the Administrative Pay-As-You-Go Act of 2023, M-23-21 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 1, 2023). Exec. Order No. 14094 was in effect during the time period covered by our review but was subsequently revoked by Exec. Order No. 14148, Initial Rescissions of Harmful Executive Orders and Actions, 90 Fed. Reg. 8237 (January 28, 2025).

[9]Direct spending is defined as (1) budget authority by law other than appropriation acts, (2) entitlement authority, and (3) the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. Pub. L. No. 118-5, § 262(4), 137 Stat. at 31; 2 U.S.C. § 900(c)(8).

[10]Office of Management and Budget, Budget Discipline for Agency Administrative Actions, M-05-13 (Washington, D.C.: May 23, 2005).

[11]Office of Management and Budget, Analytical Perspectives: Budget of the U.S. Government Fiscal Year 2010 (Feb. 26, 2009).

[12]Exec. Order No. 13893, Increasing Government Accountability for Administrative Actions by Reinvigorating Administrative PAYGO, 84 Fed. Reg. 55,487 (Oct. 16, 2019).

[13]Exec. Order No. 13992, Revocation of Certain Executive Orders Concerning Federal Regulation, 86 Fed. Reg. 7049 (Jan. 25, 2021).

[14]The act refers to rules that affect direct spending and are not required by law or for which an agency has discretion in the matter in which to implement the rule as “covered discretionary administrative actions.” Pub. L. No. 118-5, § 262(3), (6), 137 Stat. at 31. Under the act, before an agency finalizes any covered discretionary administrative action, the agency was required submit to OMB a written notice including an estimate of the budgetary effects of the covered discretionary administrative action. Pub. L. No. 118-5, § 263(a), 137 Stat. at 32.

[15]Pub. L. No. 118-5, §§ 263, 265, 266, 137 Stat. at 32–33.

[16]Pub. L. No. 118-5, § 268, 137 Stat. at 33.

[18]For rules that were not exempt, OMB was able to waive the administrative PAYGO requirements if it concluded that the waiver was necessary for delivery of essential services or effective program delivery. Pub. L. No. 118-5, § 265, 137 Stat. at 33.

[19]Rules published by independent regulatory agencies were not subject to the administrative PAYGO requirements. Pub. L. No. 118-5, § 262(2), 137 Stat. at 31. The independent regulatory agencies are listed in statute at 44 U.S.C. § 3502(5).

[20]Pub. L. No. 118-5, § 266, 137 Stat. at 33.

[21]The Congressional Review Act (CRA) requires federal agencies to submit a report on each new rule to Congress and us before it can take effect. 5 U.S.C. § 801(a)(1)(A). We reviewed all 153 major rules in our CRA database that were (1) published during this period, and (2) from agencies subject to the Fiscal Responsibility Act. We only reviewed major rules because any rule subject to the administrative PAYGO requirements would have been a major rule.

[22]Office of Management and Budget, Circular A-4: Regulatory Analysis, (Sept. 17, 2003). This version of circular A-4 is currently in effect and was in effect when the rules discussed in this report were published.

[23]87 Fed. Reg. 51,641 (Aug. 23, 2022); 88 Fed. Reg. 19,239 (Mar. 31, 2023); 88 Fed. Reg. 31,232 (May 16, 2023); 88 Fed. Reg. 31,218 (May 16, 2023).

[24]86 Fed. Reg. 63,458 (Nov. 16, 2021).

[25]87 Fed. Reg. 60,092 (Oct. 4, 2022).

[26]86 Fed. Reg. 62,944 (Nov. 15, 2021).

[27]For all rules where we were not able to initially complete our analysis based on the available information, we requested more information from agencies. While we were able to complete our analysis after consulting with the agencies in some cases, for these three rules and two others discussed below, we were still unable to determine whether a rule could have been subject to administrative PAYGO requirements.

[28]87 Fed. Reg. 27,704 (May 9, 2022).

[29]86 Fed. Reg. 46,972 (Aug. 23, 2021).

[30]87 Fed. Reg. 61,979 (Oct. 13, 2022). In its economic analysis of this rule, IRS refers to the payments resulting from this tax credit as transfers from the federal government. As stated above, for the purposes of this report we refer to such transfers from the federal government as increases in federal costs.

[31]In November 2023, we reported that 28 major rules had been issued as of November 3, 2023, since the act was signed into law on June 3, 2023. See GAO‑24‑106968.

[32]88 Fed. Reg. 55,506 (Aug. 15, 2023).

[33]We have previously reported on the exemption of IRS rules from regulatory review requirements. See GAO, Regulatory Guidance Processes: Treasury and OMB Need to Reevaluate Long-standing Exemptions of Tax Regulations and Guidance, GAO‑16‑720 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 6, 2016). We recommended that Treasury and OMB reconsider their long-standing agreement that exempted certain IRS regulations from Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) review. In April 2018, Treasury and OMB signed a memorandum of agreement that set forth terms under which OIRA would review tax regulatory actions. Then, in June 2023, Treasury and OMB issued a new memorandum of agreement that superseded the earlier agreement, reestablishing that tax regulations would not be subject to OIRA review. In January 2025, Executive Order 14192 reinstated the 2018 memorandum of agreement. See Exec. Order No. 14192, Unleashing Prosperity Through Deregulation, 90 Fed. Reg. 9065 (Feb. 6, 2025). For more information on this topic, see Congressional Research Service, Reliance on Treasury Department and IRS Tax Guidance, IF11604, Version 3 (Sept. 24, 2024).

[34]88 Fed. Reg. 36,485 (June 5, 2023).

[35]Non-federal costs were not a factor when determining if a rule was subject to administrative PAYGO requirements. Therefore, we did not include non-federal cost estimates in our analysis.

[36]88 Fed. Reg. 50,020 (Aug. 1, 2023).

[37]88 Fed. Reg. 70,004 (Oct. 10, 2023).

[38]88 Fed. Reg. 69,503 (Oct. 5, 2023). The total estimated federal costs associated with this rule were calculated to be $745 million using a 3 percent discount rate and $903 million using a 7 percent discount rate.

[39]88 Fed. Reg. 53,200 (Aug. 7, 2023).

[40]88 Fed. Reg. 43,820 (July 10, 2023). The agency also estimated that the rule would have largely one-time administrative costs of $17.3 million.

[41]GAO‑24‑106968. Rules could be exempt from administrative PAYGO requirements for multiple reasons, including if the rule did not increase direct spending by at least $1 billion over 10 years or $100 million in each of those 10 years. Pub. L. No. 118-5, § 266, 137 Stat. at 33. In addition, some rules could be eligible for a waiver from the administrative PAYGO requirements. Pub. L. No. 118-5, § 265(a), 137 Stat. at 33.

[42]88 Fed. Reg. 43,820, 43,867 (July 10, 2023).

[43]We have previously reported on OMB’s rulemaking processes. See, for example, GAO, Federal Rulemaking: Opportunities Remain for OMB to Improve the Transparency of Rulemaking Processes, GAO‑16‑505T (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 15, 2016).

[44]OIRA is responsible for reviewing rules deemed “significant,” as that term is defined in Executive Order 12866. For a brief time, Executive Order 14094 altered the definition of “significant,” but that executive order was rescinded in January 2025.

[45]Administrative PAYGO reporting requirements were in effect from June 3, 2023, until December 31, 2024.

[46]Pub. L. No. 118-5, § 264, 137 Stat. at 32; Office of Management and Budget, Guidance for Implementation of the Administrative Pay-As-You-Go Act of 2023, M-23-21 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 1, 2023).

[47]OMB could only grant a waiver if it concluded these conditions are met. Pub. L. No. 118-5, § 265, 137 Stat. at 33.

[48]See, for example, 88 Fed. Reg. 43,820, 43,867 (July 10, 2023), which includes a statement about OMB’s waiver determination.

[49]Pub. L. No. 118-5, § 263(a)(2)(B)(i), 137 Stat. at 32.

[50]Agencies were not legally required to implement any proposed offsets. As defined in the act, “discretionary” rules were rules that were not required by law as well as rules that were required by law but for which the agency had discretion in implementing the rule. Pub. L. No. 118-5, § 262(6), 137 Stat. at 31. In contrast, “nondiscretionary” rules were those required by law but for which the agency had no discretion in how to implement the rule. For such nondiscretionary rules, agencies were required to provide a legal opinion for their conclusion and a projection of the amount of direct spending under the “least costly option” for implementation. Pub. L. No. 118-5, § 263(b), 137 Stat. at 32. OMB’s guidance notes that since agencies, by definition, have no discretion with nondiscretionary rules, the “least costly option” would typically be the same as the rule. Therefore, the estimate of direct spending in these cases would typically be $0.

[51]Pub. L. No. 118-5, §§ 261–270, 137 Stat. 10, 31–33 (2023). The Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023 was enacted on June 3, 2023.

[52]Interim final rules vary from the notice-and-comment rulemaking process in that they go into effect without a prior notice, generally when an agency finds it has good cause to do so.

[53]Office of Management and Budget, Guidance for Implementation of the Administrative Pay-As-You-Go Act of 2023, M-23-21 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 1, 2023).

[54]5 U.S.C. § 804(2).

[55]Office of Management and Budget, Circular A-4: Regulatory Analysis (Sept. 17, 2003). This version of circular A-4 is currently in effect and was in effect when the rules discussed in this report were published.

[56]We contacted 10 agencies: the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, the Department of Agriculture, the Department of Education, the Department of Energy, the Department of Homeland Security, the Department of Housing and Urban Development, the Department of Labor, the Department of Transportation, the Department of the Treasury, and the Department of Veterans Affairs. While we were able to complete our analysis after consulting with the agencies in most cases, we were still unable to determine whether five rules could have been subject to administrative PAYGO requirements.

[57]GAO, Federal Rulemaking: Status of Actions to Offset Direct Spending from Administrative Rules, GAO‑24‑106968 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 30, 2023).