ILLICIT FENTANYL

DHS Has Various Efforts to Combat Trafficking but Could Better Assess Effectiveness

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Rebecca Gambler at GamblerR@gao.gov.

Why GAO Did This Study

DHS is responsible for securing the nation’s borders against the trafficking of drugs. This includes illicit fentanyl, which continues to be the primary cause of overdose deaths in the U.S. The James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for FY 2023 requires DHS to, among other things, establish a program to collect data and develop measures to assess the effectiveness of efforts to detect and deter illicit fentanyl, including its analogues and precursor chemicals, from being trafficked into the U.S. The Act includes a provision for GAO to review the data collected and measures developed by DHS’s program.

This report examines (1) DHS data on seizures of illicit fentanyl, its precursor chemicals, and production equipment from FY 2021 through 2024; (2) DHS efforts to combat the trafficking of these items into the U.S.; and (3) the extent DHS has assessed the effectiveness of its efforts. GAO analyzed DHS, CBP, and HSI documents and data on fentanyl-related seizures and investigations for FY 2021 through 2024. GAO also interviewed DHS, CBP, and HSI officials, including CBP and HSI field officials during visits to four locations.

What GAO Recommends

GAO recommends that DHS (1) establish a statutorily required program to collect data and develop measures to assess efforts to combat fentanyl trafficking into the U.S., (2) ensure the entity it tasks with establishing the program has access to needed information, and (3) develop performance goals and measures for its strategic goals. DHS concurred with the recommendations.

What GAO Found

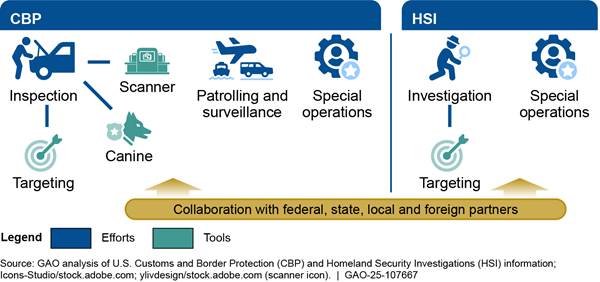

Department of Homeland Security (DHS) components—primarily U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s Homeland Security Investigations (HSI)—led or assisted on the seizure of almost 460,000 pounds of fentanyl and chemicals used to make fentanyl (precursors) and 10,000 pieces of equipment used to make fentanyl pills (production equipment) from fiscal years (FY) 2021 through 2024. DHS conducts various efforts to combat the trafficking of fentanyl, its precursor chemicals, and production equipment into the U.S. through CBP and HSI. Specifically, CBP inspects incoming travelers and shipments and patrols and surveils the border; and HSI investigates bad actors and transnational criminal organizations. CBP and HSI also conduct special operations to disrupt fentanyl-related supply chains and collaborate with federal, state, local, and foreign law enforcement partners.

DHS analyzes and reports data on its efforts to combat fentanyl trafficking, but its ability to fully assess the effectiveness of its efforts is limited. This is because it has not established a statutorily required program and incorporated key performance management practices. Specifically, DHS has not established a program to collect data and develop measures to assess the effectiveness of efforts to combat the trafficking of illicit fentanyl, including synthetic opioids with chemical structures related to fentanyl (analogues) and precursor chemicals, into the U.S., as required by law. DHS tasked CBP with establishing the program, but CBP does not have access to the information it needs to do so, such as other components’ data and measures. By establishing the required program, DHS would be better positioned to assess the effectiveness of its efforts. Additionally, DHS has not developed performance goals and measures related to its strategic goals for its efforts to combat fentanyl trafficking. By developing performance goals for its strategic goals as well as measures for those performance goals, which could be established through the statutorily required program, DHS would be better positioned to assess progress toward achieving its long-term goals.

Abbreviations

|

AMO |

Air and Marine Operations |

|

CBP |

U.S. Customs and Border Protection |

|

DHS |

Department of Homeland Security |

|

HSI |

Homeland Security Investigations |

|

ICE |

Office of Field Operations |

|

OFO |

Office of Field Operations |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

September 2, 2025

Congressional Committees

Fentanyl continues to be the primary cause of overdose deaths across the country. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated that in 2024 there were about 48,000 synthetic opioid overdose deaths—primarily fentanyl—in the U.S., accounting for 60 percent of all overdose deaths. Fentanyl is 100 times more potent than morphine and 50 times more potent than heroin. As a result, a very small amount of fentanyl or its analogues can increase the risk of overdose.[1] According to the Drug Enforcement Administration, 2 milligrams of fentanyl—the size of a few grains of sand—can cause a lethal overdose.

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has an important role in national efforts to prevent drug misuse, which has been a persistent public health issue in the U.S.[2] DHS is the lead federal agency for securing the nation’s borders against the trafficking of drugs, including illicit fentanyl.[3] The two primary DHS components involved in combating the trafficking of illicit fentanyl into the U.S. are (1) U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and (2) U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).[4]

The James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 included a provision for us to review DHS efforts to collect data and develop measures to assess the effectiveness of technologies and strategies used to detect and deter illicit fentanyl, including its analogues and precursor chemicals, from being trafficked into the U.S. at and between ports of entry.[5] This report examines (1) what DHS data show about seizures of illicit fentanyl, its precursor chemicals, and production equipment from fiscal years 2021 through 2024; (2) DHS efforts to combat the trafficking of illicit fentanyl, its precursor chemicals, and production equipment into the U.S.; and (3) the extent to which DHS has assessed the effectiveness of its efforts to combat the trafficking of illicit fentanyl, its precursor chemicals, and production equipment into the U.S.[6]

To address our first two objectives, we analyzed data on seizures of fentanyl, its analogues and precursor chemicals, and production equipment that occurred during fiscal years 2021 through 2024 from CBP’s SEACATS and U.S. Border Patrol’s e3.[7] To assess the reliability of these data, we performed electronic testing, reviewed information about the systems, compared the data to CBP’s public reports, and interviewed agency officials. We found these data to be sufficiently reliable for the purpose of describing (1) the total amount and number of fentanyl, fentanyl analogue, fentanyl precursor chemical, and production equipment seizures led and assisted by DHS and each of the DHS components with primary responsibility for combating drug trafficking at and between U.S. ports entry; and (2) the minimum amount and number of fentanyl, fentanyl analogue, fentanyl precursor chemical, and production equipment seizures that involved the use of targeting, canines, and non-intrusive inspection equipment from fiscal years 2021 through 2024.[8]

To describe DHS efforts to combat the trafficking of illicit fentanyl, its precursor chemicals, and production equipment into the U.S., we reviewed documentation from DHS, CBP, and ICE’s Homeland Security Investigations (HSI), including counter-fentanyl plans or strategies. We also analyzed summary-level data on fentanyl-related cases, indictments, arrests, convictions, disruptions, and dismantlements for fiscal years 2021 through 2024 from HSI’s Investigative Case Management system.[9] To assess the reliability of these data, we performed logic testing, reviewed information about the system, and interviewed agency officials. We found these data to be sufficiently reliable for the purpose of reporting the total and average annual number of fentanyl-related HSI cases, indictments, arrests, convictions, disruptions, and dismantlements from fiscal years 2021 through 2024.

In addition, we interviewed CBP and HSI officials from headquarters and the field to better understand CBP and HSI efforts to combat fentanyl trafficking. Specifically, in the field, we interviewed CBP officials from locations in California and Arizona and HSI officials from locations in California, Arizona, and Texas.[10] We conducted most of these interviews during in-person visits to Los Angeles and San Diego, California and Tucson, Arizona.[11] During these visits, we observed CBP efforts and tools to combat fentanyl trafficking at three land ports of entry, an international mail facility, air and sea cargo examination facilities, and two immigration checkpoints. The information we obtained from these interviews and visits cannot be generalized; however, it provided valuable insights on CBP and HSI efforts and tools to combat fentanyl trafficking.

To determine the extent to which DHS assessed the effectiveness of its efforts to combat the trafficking of illicit fentanyl, its precursor chemicals, and production equipment into the U.S., we reviewed DHS, CBP, and HSI documents describing agency goals, measures, and performance and interviewed DHS headquarters officials and the CBP and HSI headquarters and field officials cited above. We evaluated DHS’s efforts to assess its effectiveness at combating fentanyl trafficking against DHS’s Organizational Performance Management Guidance, GAO’s guide on evidence-based policymaking, and select key performance management practices identified in our prior work.[12]

We also interviewed or obtained responses to questions from officials from DHS’s Office of Strategy, Policy, and Plans and Office of the Executive Secretary as well as CBP’s Office of Field Operations (OFO), Office of the Executive Secretariat, and Office of Congressional Affairs to determine the status of DHS’s establishment of a statutorily required program to collect data and develop measures to assess the effectiveness of efforts to combat fentanyl trafficking into the U.S.[13] We evaluated DHS’s establishment of the required program against the applicable statutory provisions and select leading practices for interagency collaboration such as ensuring participants in a collaborative effort have access to the information needed to assess progress toward agreed-upon outcomes.[14] See appendix I for a more detailed explanation of our scope and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from June 2024 to September 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

DHS Component Responsibilities for Combating Fentanyl Trafficking into the U.S.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection

Among other responsibilities, CBP is responsible for stopping the unlawful movement of people, drugs, chemicals, and other contraband across U.S. borders.[15] In October 2023, CBP released its Strategy to Combat Fentanyl and Other Synthetic Drugs and established the Fentanyl Campaign Directorate to oversee the implementation of the strategy and facilitate coordination within CBP and with other federal, state, local, international, and industry partners. According to CBP, its strategy helps develop a whole-of-government and international effort to anticipate, identify, mitigate, and disrupt fentanyl producers, suppliers, and traffickers.

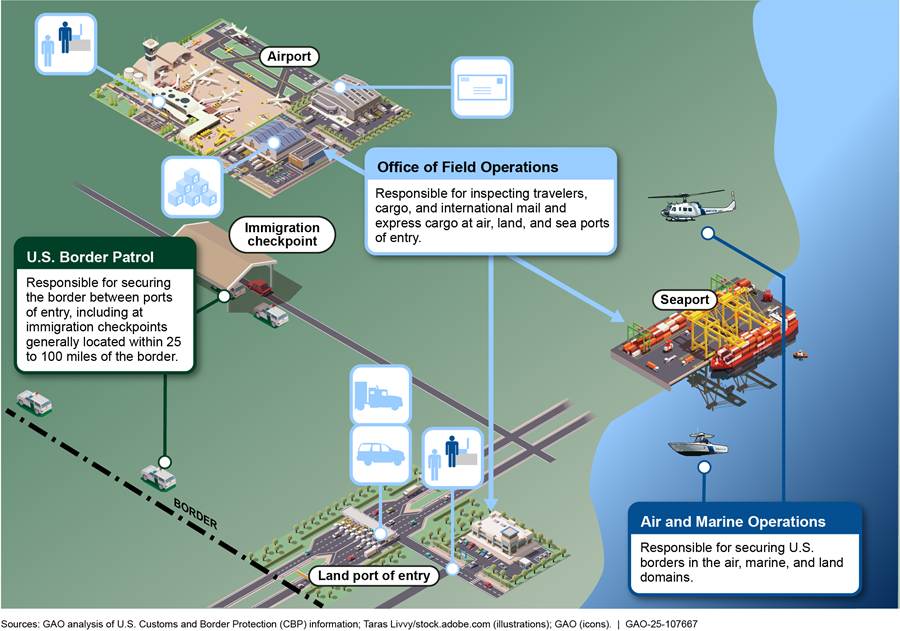

Within CBP, three components—OFO, Border Patrol, and Air and Marine Operations (AMO)— have primary responsibility for border security, which includes seizing drugs discovered during inspections and operations in their various areas of responsibility.

· OFO is responsible for inspecting people, vehicles, international mail,[16] and cargo at more than 320 air, land, and sea ports of entry.[17]

· Border Patrol is responsible for securing U.S. borders between ports of entry, including at more than 110 immigration checkpoints on U.S. highways and secondary roads, generally located between 25 and 100 miles inland from the southwest and northern borders.[18]

· AMO is responsible for securing U.S. borders between ports of entry in the air, marine, and land environments.[19] AMO uses air and maritime assets (e.g., aircraft and vessels) to help detect drug threats and provide support to drug interdiction efforts. See figure 1 for an illustration of examples of CBP components’ operating locations where they typically seize drugs.

Additional entities within CBP assist OFO, Border Patrol, and AMO with their drug seizure responsibilities by identifying and sharing information on high-risk travelers and shipments—also referred to as targeting—and monitoring and sharing drug-related intelligence and trends in the field. For example:

· OFO’s National Targeting Center provides advance information about high-risk travelers and shipments—including suspected drugs—to ports of entry. The center also targets shipments of fentanyl, its precursor chemicals, and production equipment, and analyzes intelligence to identify the organizations involved in trafficking, producing, and distributing these items and other synthetic drugs.

· Field targeting and intelligence units conduct drug targeting and monitor drug seizure trends in the field.

· CBP’s Office of Trade provides agency personnel with trade-related intelligence and analytics to help target people and organizations involved in drug trafficking.

· CBP’s Office of Intelligence develops, coordinates, and implements the agency’s intelligence capabilities and provides agency personnel with intelligence on drug-related threats and trends. According to CBP officials, the Office of Intelligence has eight Regional Intelligence Centers—five along the southern border and three along the northern border—responsible for producing information for CBP field units on threats within their area of responsibility.

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement

ICE enforces federal laws governing border control, customs, trade, and immigration.[20] Among other responsibilities, ICE’s HSI is responsible for investigating the illicit movement of goods, including drugs, into and out of the country.[21] HSI special agents, who are deployed to over 230 domestic offices and 90 international offices, are responsible for collecting and developing evidence to identify and advance criminal cases against transnational criminal organizations and other threats to the homeland.[22] HSI’s Narcotics and Contraband Smuggling Unit is responsible for overseeing matters related to counternarcotics investigations with a connection to the U.S. border. This unit is also responsible for managing the day-to-day implementation of HSI’s Strategy for Combating Illicit Opioids. This strategy, which HSI released in September 2023, details the agency’s plan for disrupting the supply of illicit fentanyl and other opioids fueling the overdose epidemic.

DHS Components Conducted About 15,000 Fentanyl-Related Seizures from Fiscal Years 2021 Through 2024, Totaling Over 150,000 Pounds Seized

DHS Components Seized Almost 161,000 Pounds of Fentanyl and Its Precursor Chemicals and 9,800 Pieces of Production Equipment

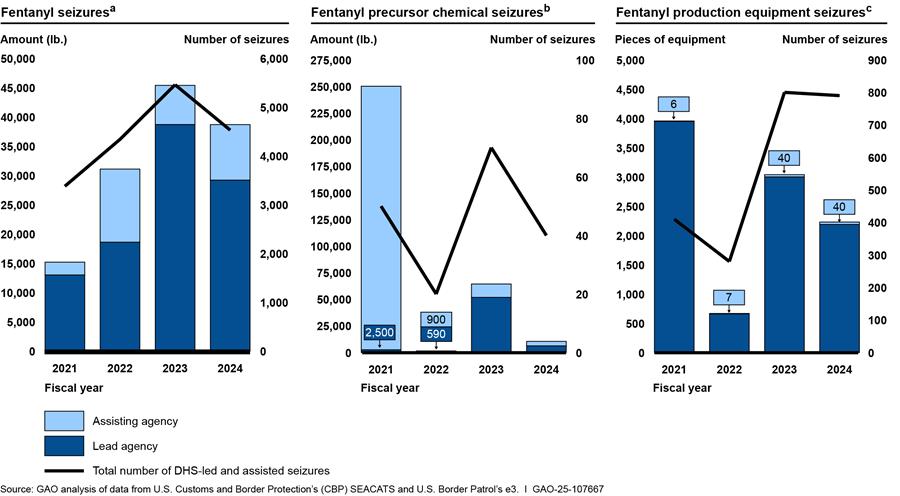

Our analysis of DHS seizure data shows that from fiscal years 2021 through 2024, DHS components conducted about 15,000 seizures resulting in about 99,500 pounds of fentanyl, 61,100 pounds of fentanyl precursor chemicals, and 9,800 pieces of production equipment being seized.[23] Over the same period, DHS components also assisted other federal, state, local, and foreign agencies on about 5,100 seizures that resulted in about 30,900 pounds of fentanyl, 265,500 pounds of fentanyl precursor chemicals, and 90 pieces of production equipment being seized.[24]

As shown in figure 2, DHS components seized more fentanyl, fentanyl precursor chemicals, and production equipment as the lead agency from fiscal years 2023 through 2024 than they did from fiscal years 2021 through 2022. According to CBP officials, CBP’s implementation of special operations, which we describe later in this report, contributed to this increase. CBP began these operations in March 2023 to provide more resources to interdict fentanyl, fentanyl precursor chemicals, and production equipment at select border locations.

Figure 2: Amount and Number of Illicit Fentanyl, Fentanyl Precursor Chemical, and Production Equipment Seizures on Which DHS Was a Lead and Assisting Agency, Fiscal Years 2021–2024

Notes: The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) led a seizure if a DHS entity was identified as the main seizing agency in SEACATS, which is the official system of record for tracking all DHS drug seizures. DHS assisted a seizure if a DHS entity was identified as a participating agency and not the main seizing agency in SEACATS or Border Patrol’s e3, which agents use to collect and transmit data related to its law enforcement activities, including drug seizures. The data for DHS-assisted seizures include about 570 seizures from e3. Agents are required to transfer all Border Patrol drug seizures into SEACATS but do not typically transfer seizures on which Border Patrol assisted another agency conducting a seizure. We rounded amounts of pounds seized above 1,000 to the nearest 100 pounds and amounts between 10 and 1,000 to the nearest 10 pounds. We rounded amounts of production equipment seized above 10 to the nearest 10 pieces. We rounded numbers of seizures above 10 to the nearest 10 seizures.

aThe amount of seized fentanyl represents the total weight of fentanyl powder, pills, and analogues, and may include other drugs or chemicals that were mixed with fentanyl or fentanyl analogues. The number of seizures represents the total number of seizures of fentanyl, fentanyl analogues, and other drugs or chemicals that were mixed with fentanyl or fentanyl analogues. DHS components led or assisted on about 80 seizures of fentanyl analogues resulting in about 180 pounds seized from fiscal years 2021 through 2024.

bThe amount of seized fentanyl precursor chemicals represents the weight of chemicals that are or could be used to produce illicit fentanyl, according to CBP’s Laboratories and Scientific Services, other federal agencies, and international entities. If a seizure contained fentanyl precursor chemicals and fentanyl or fentanyl analogues, we counted that seizure in our analysis of fentanyl seizures. From fiscal years 2021 through 2024, DHS components led or assisted on about 60 seizures that contained fentanyl precursor chemicals and fentanyl or fentanyl analogues. The data for fiscal year 2021 include two DHS component-assisted fentanyl precursor chemical seizures of about 114,300 pounds each.

cThe amount of seized production equipment represents the total number of pill presses, dies, and parts.

Our analysis of DHS seizure data shows that CBP’s OFO seized the most fentanyl, fentanyl precursor chemicals, and production equipment among DHS components from fiscal years 2021 through 2024. Table 1 presents data on fentanyl-related seizures for DHS components except CBP’s AMO, which supports the efforts of other DHS components and other federal, state, and local agencies but does not lead drug interdiction efforts. See appendix II for our analysis of DHS data on component-assisted seizures from fiscal years 2021 through 2024.

Table 1: Number and Amount of Illicit Fentanyl, Fentanyl Precursor Chemical, and Production Equipment Seizures by CBP Components and HSI, Fiscal Years 2021–2024

|

|

|

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

2024 |

||||

|

|

Component |

Number of seizures |

Amount |

Number of seizures |

Amount |

Number of seizures |

Amount |

Number of seizures |

Amount |

|

Fentanyl (lb.)a |

OFO |

1,350 |

9,100 |

1,100 |

11,100 |

1,050 |

24,700 |

730 |

17,600 |

|

Border Patrol |

190 |

640 |

300 |

1,800 |

290 |

2,700 |

310 |

3,100 |

|

|

HSI |

1,040 |

3,200 |

1,760 |

5,700 |

2,530 |

11,300 |

1,950 |

8,500 |

|

|

Fentanyl precursor chemicals (lb.)b |

OFO |

40 |

2,300 |

20 |

600 |

40 |

44,900 |

30 |

6,100 |

|

Border Patrol |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

|

HSI |

6 |

230 |

- |

- |

20 |

6,900 |

3 |

70 |

|

|

Production equipment (pieces)c |

OFO |

380 |

3,900 |

260 |

650 |

450 |

1,700 |

730 |

2,070 |

|

Border Patrol |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

|

HSI |

20 |

50 |

10 |

10 |

330 |

1,300 |

40 |

120 |

|

Source: GAO analysis of data from U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s (CBP) SEACATS. I GAO‑25‑107667

Notes: A component led a seizure if it was identified as the main seizing agency in SEACATS, which is the official system of record for tracking all CBP and Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) drug seizures. Three CBP components—the Office of Field Operations (OFO), Border Patrol, and Air and Marine Operations (AMO)—have primary responsibility for border security, which includes drug interdiction efforts. AMO supports the efforts of other Department of Homeland Security (DHS) components and other federal, state, local, and foreign agencies, but does not lead drug interdiction efforts. We rounded amounts of pounds seized above 1,000 to the nearest 100 pounds and amounts between 10 and 1,000 to the nearest 10 pounds. We rounded amounts of production equipment seized above 10 to the nearest 10 pieces. We rounded numbers of seizures above 10 to the nearest 10 seizures.

aThe amount of seized fentanyl represents the total weight of fentanyl powder, pills, and analogues, and may include other drugs or chemicals that were mixed with fentanyl or fentanyl analogues. The number of seizures represents the total number of seizures of fentanyl, fentanyl analogues, and other drugs or chemicals that were mixed with fentanyl or fentanyl analogues. DHS components conducted about 80 seizures of fentanyl analogues resulting in about 180 pounds seized from fiscal years 2021 through 2024.

bThe amount of seized fentanyl precursor chemicals represents the weight of chemicals that are or could be used to produce illicit fentanyl, according to CBP’s Laboratories and Scientific Services, other federal agencies, and international entities. If a seizure contained fentanyl precursor chemicals and fentanyl or fentanyl analogues, we counted that seizure in our analysis of fentanyl seizures. A “-” means that all relevant seizures contained fentanyl or fentanyl analogues. From fiscal years 2021 through 2024, OFO conducted two seizures of fentanyl precursor chemicals that also contained fentanyl or fentanyl analogues. HSI conducted about 60 such seizures over the same period.

cThe amount of seized production equipment represents the total number of pill presses, dies, and parts.

Most Fentanyl Was Seized in the Southwest Border Region and the Majority of Fentanyl and Related Items Were Seized at Ports of Entry

Region of DHS Fentanyl-Related Seizures

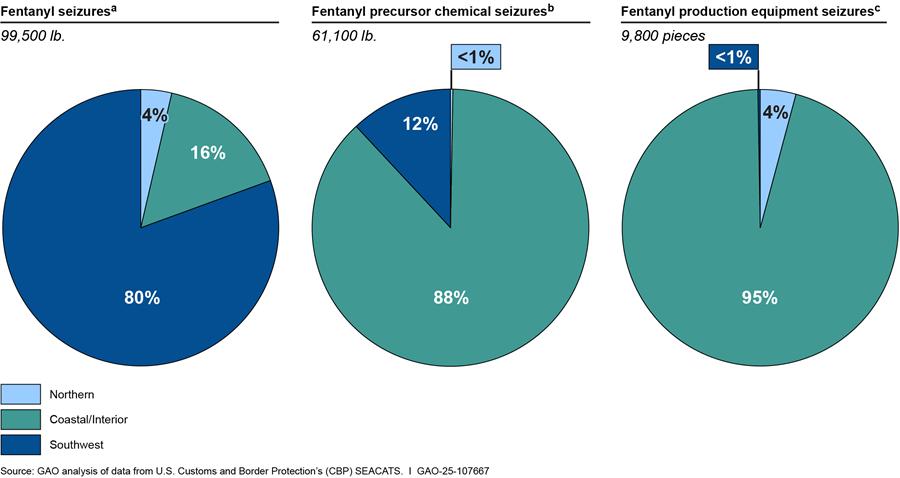

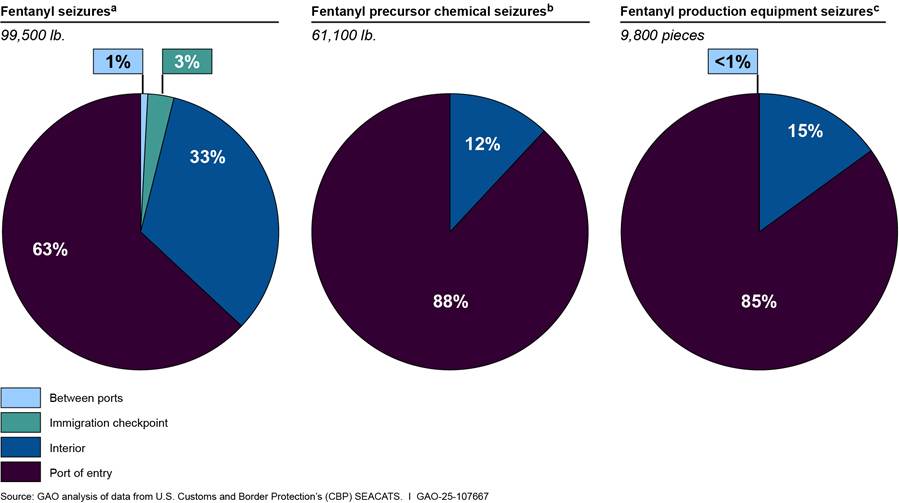

Our analysis of DHS seizure data shows that from fiscal years 2021 through 2024, about 80 percent of the fentanyl DHS components seized was in the southwest border region. As shown in figure 3, most of the fentanyl precursor chemicals (about 88 percent) and production equipment (about 95 percent) DHS components seized from fiscal years 2021 through 2024 was in the coastal and interior regions of the U.S.[25]

Figure 3: Percentage of DHS Illicit Fentanyl, Fentanyl Precursor Chemical, and Production Equipment Seizures by Region, Fiscal Years 2021–2024

Notes: We rounded the total amounts of pounds seized to the nearest 100 pounds and the total amount of production equipment seized to the nearest 10 pieces. Percentages may not add up to 100 due to rounding. We used the same regions that CBP uses in its public drug seizure data—northern, coastal/interior, and southwest.

aThe amount of seized fentanyl represents the total weight of fentanyl powder, pills, and analogues, and may include other drugs or chemicals that were mixed with fentanyl or fentanyl analogues. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) components seized about 180 pounds of fentanyl analogues from fiscal years 2021 through 2024.

bThe amount of seized fentanyl precursor chemicals represents the weight of chemicals that are or could be used to produce illicit fentanyl, according to CBP’s Laboratories and Scientific Services, other federal agencies, and international entities. If a seizure contained fentanyl precursor chemicals and fentanyl or fentanyl analogues, we counted that seizure in our analysis of fentanyl seizures. From fiscal years 2021 through 2024, DHS components led about 60 seizures that contained fentanyl precursor chemicals and fentanyl or fentanyl analogues.

cThe amount of seized production equipment represents the total number of pill presses, dies, and parts.

Location of DHS Fentanyl-Related Seizures

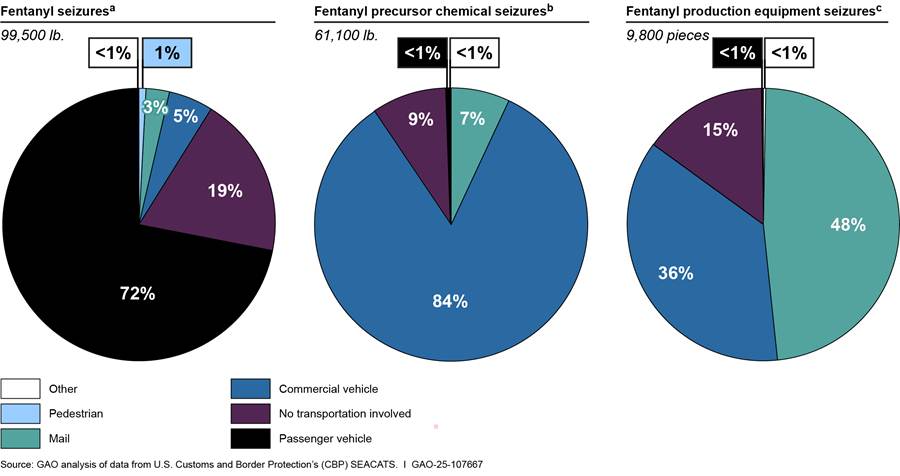

Our analysis of DHS seizure data shows that from fiscal years 2021 through 2024, the majority of fentanyl (about 63 percent) and most fentanyl precursor chemicals and production equipment (about 88 percent and 85 percent, respectively) DHS components seized was at ports of entry.

The ports of entry at which DHS components seized the largest amounts of fentanyl, fentanyl precursor chemicals, and production equipment from fiscal years 2021 through 2024 varied. Specifically, over that period, DHS components seized the largest amount of fentanyl at land ports of entry along the southwest border.[26] For example, of the fentanyl DHS components seized at ports of entry from fiscal years 2021 through 2024 (62,900 pounds), almost 70 percent was seized at three land ports of entry along the southwest border. In comparison, DHS components seized the largest amount of fentanyl precursor chemicals and production equipment from seaports, airports, and express consignment carrier facilities located across the country.[27] For example, of the fentanyl precursor chemicals and production equipment DHS components seized at ports of entry from fiscal years 2021 through 2024 (54,000 pounds and 8,300 pieces), over 90 percent of the precursors were seized at one seaport and two airports, and almost 55 percent of the equipment was seized at one seaport and two express consignment carrier facilities.

As shown in figure 4, most of the remaining fentanyl (about 33 percent), fentanyl precursor chemicals (about 12 percent), and production equipment (about 15 percent) was seized within the U.S. interior. Much of HSI’s work to combat fentanyl trafficking, which we describe later in this report, takes place within the U.S. interior. More specifically, of the DHS component seizures that occurred within the U.S. interior, HSI accounted for about 85 percent of fentanyl seizures, all fentanyl precursor chemical seizures and almost all production equipment seizures.

Figure 4: Percentage of DHS Illicit Fentanyl, Fentanyl Precursor Chemical, and Production Equipment Seizures by Location, Fiscal Years 2021–2024

Notes: We rounded the total amounts of pounds seized to the nearest 100 pounds and the total amount of production equipment seized to the nearest 10 pieces. Percentages may not add up to 100 due to rounding. Between port seizures occurred within the border area but not at a port of entry or immigration checkpoint. Interior seizures occurred beyond the border area within the U.S. interior.

aThe amount of seized fentanyl represents the total weight of fentanyl powder, pills, and analogues, and may include other drugs or chemicals that were mixed with fentanyl or fentanyl analogues. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) components seized about 180 pounds of fentanyl analogues from fiscal years 2021 through 2024.

bThe amount of seized fentanyl precursor chemicals represents the weight of chemicals that are or could be used to produce illicit fentanyl, according to CBP’s Laboratories and Scientific Services, other federal agencies, and international entities. If a seizure contained fentanyl precursor chemicals and fentanyl or fentanyl analogues, we counted that seizure in our analysis of fentanyl seizures. From fiscal years 2021 through 2024, DHS components led about 60 seizures that contained fentanyl precursor chemicals and fentanyl or fentanyl analogues.

cThe amount of seized production equipment represents the total number of pill presses, dies, and parts.

Seized Fentanyl and Related Items Were Transported Using a Variety of Methods and Came Primarily from Mexico or China

Our analysis of DHS seizure data shows that fentanyl, fentanyl precursor chemicals, and production equipment were transported into the U.S. using various methods and came primarily from either Mexico or China.[28] As shown in figure 5, from fiscal years 2021 through 2024, about 72 percent of fentanyl DHS components seized was transported by passenger vehicles, while about 84 percent of seized fentanyl precursor chemicals were transported by commercial vehicles—such as cargo trucks, ships, and planes—and 48 percent of seized production equipment was transported by mail.[29]

Figure 5: Percentage of DHS Illicit Fentanyl, Fentanyl Precursor Chemical, and Production Equipment Seizures by Transportation Method, Fiscal Years 2021–2024

Notes: We rounded the total amounts of pounds seized to the nearest 100 pounds and the total amount of production equipment seized to the nearest 10 pieces. Percentages may not add up to 100 due to rounding. Mail includes packages handled by express consignment carriers such as FedEx and the United Postal Service. Seizures for which there was no transportation involved reflects scenarios where an officer or agent seizes a drug outside of a mode of transportation, such as an abandoned drug.

aThe amount of seized fentanyl represents the total weight of fentanyl powder, pills, and analogues, and may include other drugs or chemicals that were mixed with fentanyl or fentanyl analogues. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) components seized about 180 pounds of fentanyl analogues from fiscal years 2021 through 2024.

bThe amount of seized fentanyl precursor chemicals represents the weight of chemicals that are or could be used to produce illicit fentanyl, according to CBP’s Laboratories and Scientific Services, other federal agencies, and international entities. If a seizure contained fentanyl precursor chemicals and fentanyl or fentanyl analogues, we counted that seizure in our analysis of fentanyl seizures. From fiscal years 2021 through 2024, DHS components led about 60 seizures that contained fentanyl precursor chemicals and fentanyl or fentanyl analogues.

cThe amount of seized production equipment represents the total number of pill presses, dies, and parts.

Our analysis of DHS seizure data shows that from fiscal years 2021 through 2024, the majority of fentanyl seized by DHS components (about 68 percent) came from Mexico. Most seized fentanyl precursor chemicals (about 84 percent) and production equipment (about 78 percent) came from China.[30] The results of our analysis align with the trafficking trends DHS and its components have identified. For example, according to DHS, CBP, and HSI documents, Mexico is the main source country for fentanyl and China is the main source country for fentanyl precursor chemicals. In addition, officials from CBP’s National Targeting Center identified China as the main source country for production equipment.

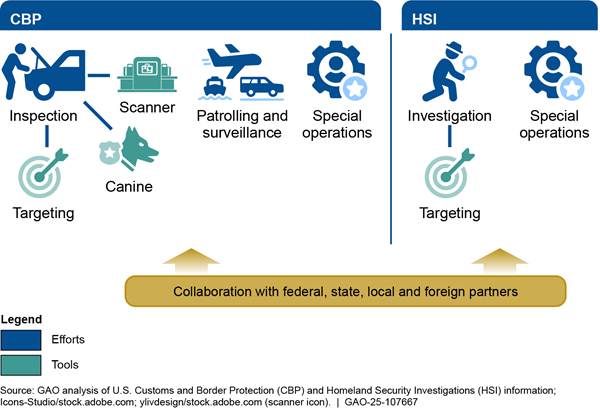

DHS Combats Fentanyl Trafficking Through CBP Inspections, Patrols, and Surveillance; HSI Investigations; and Collaborative Efforts

DHS combats the trafficking of fentanyl, its precursor chemicals, and production equipment into the U.S. through various efforts. These include CBP inspections of travelers, vehicles, and shipments; CBP patrols and surveillance along the border; and ICE’s HSI investigations of bad actors and transnational criminal organizations. As shown in figure 6, CBP and HSI use various tools, such as targeting, to conduct inspections and investigations. In addition, CBP and HSI conduct special operations that focus agency personnel and resources on disrupting fentanyl-related supply chains. CBP’s and HSI’s efforts to combat fentanyl trafficking are enhanced through collaboration with other federal, state, local, and foreign law enforcement partners.

CBP Inspects Travelers, Vehicles, and Shipments; Patrols and Surveils the Border; and Conducts Special Operations to Combat Fentanyl Trafficking

CBP efforts to combat fentanyl trafficking include OFO and Border Patrol inspections at ports of entry and immigration checkpoints, respectively, as well as Border Patrol and AMO patrol and surveillance activities between ports of entry. In addition, CBP conducts special operations that provide additional resources for inspections and patrols at specific locations along the border.

Inspections. CBP’s OFO inspects travelers, vehicles, and shipments at ports of entry and Border Patrol inspects travelers and their vehicles at immigration checkpoints using a variety of tools, including targeting, canines, and non-intrusive inspection equipment. CBP inspections involve a targeting process in which CBP uses intelligence and other information to identify and target higher-risk travelers, vehicles, and shipments for additional scrutiny at ports of entry and immigration checkpoints. CBP’s National Targeting Center provides advance information and research about high-risk travelers, vehicles, and shipments to officials at ports of entry.

CBP field officials may also review seizure and arrest reports and other law enforcement information to identify travelers, vehicles, and shipments associated with known drug traffickers and place a “lookout” on them in CBP systems. A traveler, vehicle, or shipment with a “lookout” will receive additional scrutiny at ports of entry and immigration checkpoints.

Our analysis of DHS seizure data shows that from fiscal years 2021 through 2024, targeting contributed to at least 2,530 fentanyl-related seizures at ports of entry resulting in about 11,300 pounds of fentanyl, 50,900 pounds of fentanyl precursor chemicals, and 4,810 pieces of production equipment seized.[31] Over the same period, targeting contributed to at least six fentanyl seizures at immigration checkpoints resulting in about 210 pounds seized.

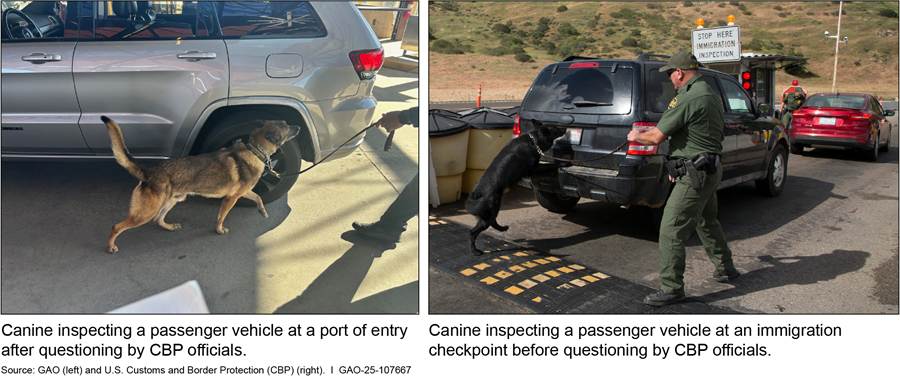

When inspecting travelers, vehicles, and shipments at some ports of entry and immigration checkpoints, CBP uses canines that are trained to detect various drugs, among other things. As shown in figure 7, CBP officials may use canines to inspect passenger vehicles before and after they question the driver and any passengers. Our analysis of DHS seizure data shows that from fiscal years 2021 through 2024, OFO canines contributed to at least 2,280 fentanyl-related seizures at ports of entry resulting in about 46,800 pounds of fentanyl and 200 pounds of fentanyl precursor chemicals seized.[32] From fiscal years 2021 through 2024, Border Patrol canines contributed to at least 140 fentanyl seizures at immigration checkpoints resulting in about 2,000 pounds seized.[33]

Figure 7: Selected Images of CBP Canines Inspecting Vehicles at a Port of Entry and Immigration Checkpoint

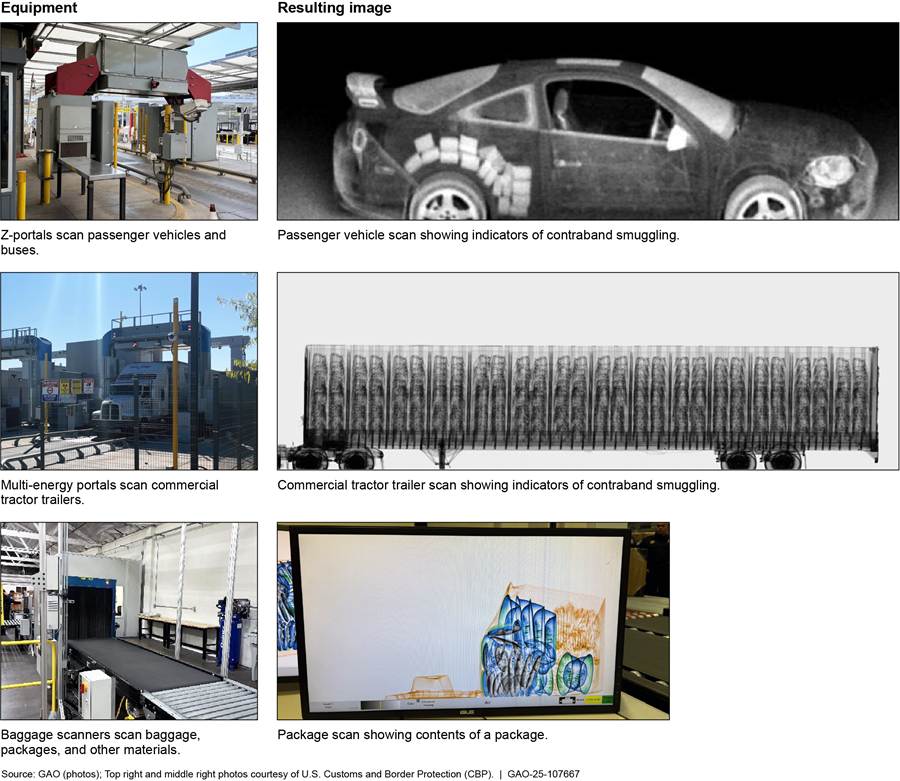

CBP also uses various types of non-intrusive inspection equipment to screen travelers, vehicles, and shipments coming into the U.S. This equipment includes small-scale handheld devices and large-scale systems designed to help CBP officials detect drugs and other illicit items without requiring them to conduct a physical inspection.[34] Figure 8 shows selected non-intrusive inspection equipment and the resulting scans that CBP officials review for anomalies that may require further inspection. Our analysis of DHS seizure data shows that from fiscal years 2021 through 2024, non-intrusive inspection equipment contributed to at least 1,030 fentanyl-related seizures at ports of entry resulting in about 20,400 pounds of fentanyl, 290 pounds of fentanyl precursor chemicals, and 1,370 pieces of production equipment seized. Over the same period, non-intrusive inspection equipment was used in at least one fentanyl seizure at an immigration checkpoint resulting in about 150 pounds seized.

|

Examples of CBP Special Operations to Combat Fentanyl Trafficking During fiscal years 2021 through 2024, CBP conducted multiple special operations. For example, between March and May 2023, CBP conducted two concurrent operations—Blue Lotus and Four Horsemen—that provided additional personnel for inspections and interdiction efforts at and between ports of entry in California and Arizona. Between May and September 2023, CBP conducted two more concurrent operations—Rolling Wave and Artemis. Rolling Wave surged personnel and resources to checkpoints in the southwest border region. Artemis deployed multidisciplinary interagency teams to strategic locations and leveraged information obtained through prior operations to target the illicit fentanyl supply chain. In addition, from August 2023 to March 2024, CBP implemented Operation Argus, which provided trade-focused intelligence and analysis in support of Artemis and Homeland Security Investigation’s Operation Blue Lotus 2.0 (described later in this report). Lastly, in April 2024, CBP implemented Operation Plaza Spike to disrupt Mexico-based plazas, which are key points in the illicit fentanyl supply chain. Plazas are territories controlled by a cartel often located directly south of a U.S. border crossing. The first two phases of this operation targeted plazas south of Nogales, Arizona and El Paso, Texas. Source: GAO analysis of U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) information. | GAO‑25‑107667 |

Patrols and Surveillance. CBP’s Border Patrol and AMO are the uniformed law enforcement components responsible for securing U.S. borders between ports of entry in the air, land, and maritime environments. For example, to detect and prevent the illegal trafficking of people, drugs, and contraband into the country, Border Patrol agents patrol international land borders and waterways and AMO interdiction agents use aircrafts and vessels to conduct surveillance and investigative activities. Our analysis of DHS seizure data shows that from fiscal years 2021 through 2024, Border Patrol conducted about 400 fentanyl seizures in areas surrounding ports of entry resulting in almost 3,900 pounds seized. Over the same period, AMO assisted other agencies with about 10 fentanyl seizures in areas surrounding ports of entry resulting in about 9 pounds seized.[35]

Special Operations. During fiscal years 2021 through 2024, CBP conducted 10 special operations to combat fentanyl trafficking. These operations provide additional personnel and tools to support inspections and patrol activities in select locations. For example, in October 2023, CBP implemented Operation Apollo, its national counter-fentanyl operation. This operation had three phases—California, Arizona, and El Paso, Texas—and focused on collecting and sharing intelligence and developing and leveraging partnerships with federal, state, local, tribal, and territorial agencies to target the smuggling of fentanyl into the U.S.

HSI Investigates Fentanyl Cases at and Beyond the Border and Conducts Special Operations

HSI combats fentanyl trafficking by investigating bad actors and transnational criminal organizations. These investigations are supported by efforts to target the methods and individuals involved in trafficking fentanyl, its precursor chemicals, and production equipment into the U.S. Additionally, HSI conducts special operations to disrupt fentanyl-related supply chains.

Investigations. HSI investigates individual seizures made by CBP at the border and conducts larger, more-complex investigations into transnational criminal organizations involved in producing or trafficking fentanyl, its precursor chemicals, and production equipment. On average, from fiscal years 2021 through 2024, HSI initiated over 2,100 fentanyl-related cases annually.[36] Over that same period, on average, HSI made over 3,600 fentanyl-related criminal arrests and obtained almost 1,400 fentanyl-related convictions annually.[37] Furthermore, HSI investigations resulted in, on average, 66 disruptions and 10 dismantlements of transnational criminal organizations involved in producing or trafficking fentanyl each year from fiscal years 2021 through 2024.[38]

|

Examples of HSI Special Operations to Combat Fentanyl Trafficking During fiscal years 2021 through 2024, HSI conducted multiple special operations. For example, HSI conducted Operations Hydra and Chain Breaker, which targeted the illicit shipment of chemicals and equipment needed to produce fentanyl from foreign locations to the U.S. In addition, from June to July 2023, HSI implemented Operation Blue Lotus 2.0, which targeted fentanyl distribution networks along the southwest border and within the U.S. interior. During this operation, HSI surged personnel to strengthen field interdiction, enforcement, and investigative efforts at ports of entry and major international commercial express consignment centers. Source: GAO analysis of Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) information. | GAO‑25‑107667 |

To support its investigative work, HSI targets the methods and individuals involved in producing or trafficking fentanyl, its precursor chemicals, and production equipment. HSI has a unit at CBP’s National Targeting Center that targets the trafficking of fentanyl, its precursor chemicals, and production equipment within the commercial air and maritime transportation systems. This unit analyzes shipping data to identify suspicious shipments and information from HSI and CBP seizures to identify the individuals and organizations involved in producing or trafficking fentanyl, its precursor chemicals, and production equipment. HSI’s targeting efforts also support CBP interdiction efforts because HSI officials may place “lookouts” on individuals or shipments in CBP systems.

Special Operations. During fiscal years 2021 through 2024, HSI conducted four special operations focused on disrupting fentanyl-related supply chains. For example, in August 2023, HSI implemented Operation Opioid Response and Investigation of Networks, its nationwide counter-opioid initiative. Through this operation, HSI targets actors engaged in fentanyl distribution via the internet and plans surges of people to support task forces focused on fentanyl supply reduction and joint operations with CBP at ports of entry.

Collaboration Enhances CBP and HSI Efforts to Combat Fentanyl Trafficking

CBP and HSI collaborate with other federal agencies, state and local law enforcement, and other countries to combat fentanyl trafficking. According to CBP and HSI, partnerships with other federal, state, local, and foreign law enforcement agencies are critical to their efforts to interdict fentanyl, its precursor chemicals, and production equipment, and disrupt fentanyl-related supply chains. See table 2 for specific examples.

Table 2: Examples of CBP and HSI Collaboration with Other Agencies and Countries to Combat the Trafficking of Illicit Fentanyl, its Precursor Chemicals, and Production Equipment

|

|

Other federal agencies |

State and local law enforcement agencies |

Other countries |

|

CBP |

CBP’s fentanyl targeting unit at the National Targeting Center (NTC) includes staff from other federal agencies such as the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) and Department of Defense. CBP’s California and Arizona Regional Intelligence Centers share information on targets for counter-fentanyl efforts with federal partners such as the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). CBP’s San Diego and Tucson Air and Marine Operations Branches provide air support to DEA, FBI, and other federal agencies on fentanyl interdiction efforts. |

The National Guards of California and Arizona provided members to help guide travelers through the CBP inspection process at ports of entry and support field intelligence units. CBP field units in California and Arizona participate in highway interdiction efforts with state and local law enforcement. In addition, CBP field units share information on seizures and targets and provide air support to state and local law enforcement. |

CBP offices, such as the NTC, Office of Trade, and Office of Intelligence share information about fentanyl trafficking with other countries. Officials from one Border Patrol sector told us they conduct mirrored patrols with Mexican law enforcement in high-risk areas along the border on a weekly basis. In addition, the sector’s Foreign Operations Branch shares information about fentanyl trafficking with Mexico. CBP works with other countries to assess and improve fentanyl detection capabilities within their canine programs. |

|

HSI |

HSI works with other federal agencies on Operation Hydra, which targets fentanyl precursor chemicals, and Operation Chain Breaker, which targets production equipment. For example, HSI works with the U.S. Postal Service to target inbound pill presses. At Arizona ports of entry, HSI and CBP collaborate on fentanyl seizures and investigative efforts through Joint Port Enforcement Groups. |

HSI works with state and local law enforcement agencies through its Border Enforcement Security Task Forces (BEST) and Fentanyl Abatement Suppression Teams (FAST). BESTs investigate a wide range of criminal activity including fentanyl trafficking and are located along the northern and southwest land borders and at sea and airports. FASTs focus on identifying and disrupting fentanyl distribution networks across the U.S. |

HSI has Transnational Criminal Investigative Units composed of vetted and trained local law enforcement officers based in several countries. These units identify targets and share information with HSI to help prosecute members of transnational criminal organizations. Through Operation Hydra, HSI works with the Mexican military on efforts to seize fentanyl precursor chemicals and take down covert fentanyl labs. HSI also works with other countries to disrupt the fentanyl precursor chemical supply chain. |

Source: GAO analysis of U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) information. | GAO‑25‑107667

DHS Analyzes and Reports Data on Its Efforts to Combat Fentanyl Trafficking but Lacks the Goals and Measures Needed to Fully Assess Effectiveness

DHS and Its Components Analyze and Report Data on Their Efforts to Combat Fentanyl Trafficking

DHS and its components analyze and report a variety of data related to their efforts to combat fentanyl trafficking. For example, DHS has a public webpage that describes its efforts to combat fentanyl and presents fiscal year 2024 data on the pounds of fentanyl and number of pill presses seized, number of people connected to criminal fentanyl networks arrested, and number of drug-related HSI investigations initiated.

In addition, DHS’s Office of Homeland Security Statistics publishes fiscal year data on four measures related to CBP and HSI efforts to disrupt the flow of illicit fentanyl into the U.S. The four measures are (1) pounds of fentanyl seized by CBP and HSI; (2) number of drug-producing devices seized by CBP and HSI; (3) dollar value of U.S. cash and currency seized by HSI during fentanyl disruption operations; and (4) dollar value of personal property seized by HSI during fentanyl disruption operations.[39] Officials from the Office of Homeland Security Statistics told us that they plan to develop and report on additional measures in the future—specifically, fentanyl precursor chemical seizures and fentanyl-related arrests, indictments, and convictions. They explained that fentanyl precursor chemicals are a key focus for DHS and that arrests, indictments, and convictions are important for understanding DHS’s effectiveness at disrupting illicit activity. The office also develops internal dashboards to provide monthly updates to DHS leadership on the four measures as well as arrests.

CBP also analyzes and reports a variety of data on its efforts to combat fentanyl trafficking. For example, CBP has public dashboards that include fiscal year data on the number of fentanyl seizure events and pounds of fentanyl seized by CBP and the number of doses and value of fentanyl seized by OFO. According to CBP’s dashboard, in fiscal years 2023 and 2024, OFO seized over 40,000 pounds of fentanyl, which CBP equated to over 2 billion doses and valued at roughly $137 million. CBP also analyzes and internally reports fentanyl-related arrests and seizures of fentanyl, its precursor chemicals, and production equipment. Furthermore, CBP monitors overdose deaths and the street value of fentanyl to better understand the effectiveness of its efforts to combat fentanyl trafficking. Lastly, according to CBP officials, the Fentanyl Campaign Directorate regularly collects information to assess progress made toward the goals and objectives of CBP’s Strategy to Combat Fentanyl and Other Synthetic Drugs.

HSI analyzes and internally reports data on its efforts to combat fentanyl trafficking. For example, HSI develops an internal report that includes monthly data on national investigative activity related to fentanyl. Specifically, the report includes data on fentanyl-related arrests, and personal property, U.S. currency, and production equipment seizures, among other things. In addition, according to HSI officials, the Narcotics and Contraband Smuggling Unit holds monthly meetings to review progress made on efforts related to its Strategy for Combating Illicit Opioids.

DHS Has Not Established a Program to Collect Data and Develop Effectiveness Measures for Efforts to Combat Fentanyl Trafficking

DHS has not established a program to collect data and develop measures to assess the effectiveness of efforts to combat fentanyl trafficking into the U.S. (hereafter referred to as the data and measures program), as required by the James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023.[40] As a result, DHS’s ability to fully understand the effectiveness of these efforts is limited. More specifically, the Act requires the Secretary of Homeland Security to establish a program to collect data and develop measures to assess how technologies and strategies used by DHS and other relevant federal agencies have helped combat the trafficking of illicit fentanyl, including its analogues and precursor chemicals, into the U.S. at and between ports of entry. It also requires DHS to report to Congress based on the data collected and measures developed by the program.[41]

DHS delegated the responsibility for establishing the data and measures program and the related reporting requirement to CBP. Specifically, DHS first delegated the reporting requirement to CBP in October 2023. In August 2024, after DHS submitted its first report to Congress, CBP officials told us that DHS advised them that the agency was also responsible for establishing the data and measures program. However, in October 2024, CBP officials told us that CBP should not be responsible for establishing the program because it does not have visibility into the measures of other relevant agencies, such as HSI, or access to other agencies’ data.

DHS’s first report to Congress on its efforts to combat fentanyl trafficking, which was drafted by CBP, primarily described CBP efforts and provided more limited information on DHS’s or other components’ efforts.[42] In particular, the report did not contain data or measures related to the efforts of other DHS components, such as HSI. In December 2024, DHS officials told us that CBP would have to confer with DHS if it wants another entity to take responsibility for establishing the data and measures program. As of April 2025, DHS had not informed us that it reassigned the responsibility for establishing the program or addressed CBP’s lack of access to the information needed to develop and assess effectiveness measures.

As stated earlier, DHS’s Office of Homeland Security Statistics currently analyzes and reports data on four measures related to DHS fentanyl disruption operations. While these measures are helpful for understanding DHS’s efforts, their usefulness for assessing effectiveness is limited because the measures do not reflect indicators that CBP and HSI officials told us are helpful for understanding effectiveness. For example, CBP and HSI officials told us that overdose deaths, street price, and disruptions and dismantlements of transnational criminal organizations are helpful for understanding the effectiveness of efforts to combat fentanyl trafficking.[43] Furthermore, officials from DHS’s Office of Homeland Security Statistics told us that the office is not responsible for establishing the required data and measures program. They explained that the office began reporting data on the measures to provide the public with official, validated statistics on DHS fentanyl disruption efforts.

DHS’s efforts to combat fentanyl trafficking are collaborative in nature because multiple agencies—primarily CBP and HSI—conduct and maintain information on these efforts. According to our leading practices for interagency collaboration, participants in a collaborative effort—in this case, DHS, CBP, and HSI—should work together to define common outcomes they want to achieve, such as agreed-upon goals and measures.[44] Furthermore, participants should ensure that the data and information needed to assess progress toward those outcomes is accessible. Our prior work on these leading practices also found that collaborative efforts benefit from identifying the appropriate leadership model (e.g., one agency or person, or assigning shared leadership) and clarifying roles and responsibilities.

By establishing the data and measures program, DHS would address a statutory requirement and be better positioned to assess the effectiveness of efforts to combat fentanyl trafficking into the U.S. Furthermore, ensuring that the entity or entities it tasks with establishing the program have access to information from across the department, including from relevant components, would enable DHS to develop measures that reflect the outcomes that DHS and its components want to achieve and assess progress toward those outcomes.

DHS Has Strategic Goals for Its Efforts to Combat Fentanyl Trafficking but Has Not Developed Related Performance Goals and Measures

In addition to not establishing the statutorily required data and measures program, DHS has not developed performance goals and measures that relate to its long-term strategic goals for its efforts to combat fentanyl trafficking. As a result, DHS’s ability to assess progress toward its strategic goals is limited.

DHS established the following long-term strategic goals for its efforts to combat fentanyl trafficking in its Plan to Combat Fentanyl and a July 2023 memorandum for operational components regarding the implementation of the plan:

· Reduce the amount of illicit fentanyl entering the U.S. and disrupt the illicit fentanyl market by disrupting and degrading transnational criminal organizations’ networks.

· Commercially disrupt global illicit fentanyl production and the trafficking supply chain to halt the flow of fentanyl and their precursor chemicals and save lives.

DHS’s Plan to Combat Fentanyl describes four lines of effort— (1) precursor chemicals, (2) pill presses and parts, (3) movement, and (4) proceeds—and actions for each line of effort. However, the plan does not include performance goals and measures that link back to DHS’s strategic goals for its efforts to combat fentanyl trafficking.

According to DHS, the primary purpose of the Plan to Combat Fentanyl was to operationalize DHS’s responsibilities found in the National Security Council’s Strategic Implementation Plan to Commercially Disrupt the Illicit Fentanyl Supply Chain. Officials from the office responsible for implementing DHS’s plan confirmed that they did not establish any performance goals and measures related to DHS’s strategic goals for its efforts to combat fentanyl trafficking. These officials explained that they did not establish performance goals and measures for DHS’s strategic goals because they were working towards the goals and measures included in the National Security Council’s plan. While the National Security Council’s plan includes a strategic goal, multiple strategic objectives, and output- and outcome-oriented performance measures for the plan’s action items, these goals, objectives, and measures define the results the federal government wants to achieve, not the specific results that DHS wants to achieve through its own efforts.

According to DHS’s Organizational Performance Management Guidance, programs should use various types of performance measures (e.g., outcome-, output-, process-oriented) with target levels of performance for the fiscal year—or performance goals—to tell the story of how a program is achieving high-level mission goals and contributing to the accomplishment of DHS strategy.[45] According to our guide on evidence-based policymaking, to ensure that an agency can assess progress toward its long-term goals, it should break those goals down into one or more related performance goals that define the specific results the agency expects to achieve in the near-term.[46] The guide also states that performance goals help direct an organization’s activities and allow decision-makers, staff, and stakeholders to assess performance by comparing planned and actual results. Furthermore, a key practice of results-oriented performance management that we identified in our prior work is establishing one or more performance measures for each performance goal to collect relevant information to assess program performance and progress toward the goal.[47]

DHS, CBP, and HSI officials we met with described various challenges with assessing the effectiveness of efforts to combat fentanyl trafficking. For example,

· DHS officials explained that outputs related to DHS enforcement, such as arrests and seizures, are not clear signs of effectiveness. For example, an increase in the number of fentanyl seizures could be a sign of more effective enforcement or increased supply.

· CBP and HSI officials said it is difficult to determine the discrete impact of their agencies’ efforts on broader outcomes (e.g., drug prices and overdose deaths) because improvements could be attributed to other factors, such as increased drug education or access to overdose reversal medicine.

· CBP officials also told us that the lack of an estimate for total illicit fentanyl production makes it difficult to assess the effectiveness of efforts to reduce the supply of illicit fentanyl. These officials explained that total illicit production cannot be estimated because fentanyl can be produced in a small, enclosed space (e.g., a basement), using a few chemicals in relatively small amounts and some basic tools. These officials added that fentanyl and its precursor chemicals do not spoil so they can be stored indefinitely, and new precursor chemicals are constantly being developed.

DHS’s Organizational Performance Management Guidance states that measuring the effectiveness of DHS efforts to prevent or deter bad things from happening can be challenging because there is often no clear causation between the lack of something occurring and DHS’s efforts. According to DHS’s guidance, to develop useful goals, programs need to consider what event it is trying to prevent, what activities are in place to prevent it from happening, and how to measure how well those activities are working. The guidance also states that “proxy” goals—an indirect way to measure progress toward a closely-related outcome that the program is trying to achieve—are often needed for programs with a prevention mission.[48] DHS’s guidance recommends that programs have a number of proxy goals, in addition to other types of goals that represent the layered security or enforcement measures that are in place.

By establishing performance goals that relate to the outcomes reflected in its strategic goals for its efforts to combat fentanyl trafficking, DHS and other stakeholders would be better able to assess the department’s progress toward disrupting the illicit fentanyl market and the flow of fentanyl into the U.S. Furthermore, by establishing measures for its performance goals, which could be developed through the statutorily required program discussed above, DHS would be better positioned to collect the information it needs to assess program performance and progress towards its goals.

Conclusions

Each year, tens of thousands of Americans die from fentanyl overdoses. DHS plays a key role in preventing fentanyl overdose as the lead agency for federal efforts to combat the trafficking of fentanyl, its precursor chemicals, and production equipment into the country. DHS, through its components, conducts various efforts to combat fentanyl trafficking including inspections of incoming travelers and shipments, investigations into transnational criminal organizations, and collaboration with federal, state, local, and foreign law enforcement partners.

DHS analyzes and reports data on its efforts to combat fentanyl trafficking. However, additional actions are needed to fully assess the effectiveness of its efforts. Specifically, DHS has not established a program to collect data and develop measures to assess the effectiveness of efforts to combat the trafficking of fentanyl, including its analogues and precursor chemicals, into the U.S., as required by law. DHS tasked CBP with establishing this program, but CBP does not have access to the information it needs to do so, such as other components’ data and measures. By establishing the program and ensuring that the entity or entities it tasks with doing so has access to the necessary information, DHS would satisfy a statutory requirement and be better positioned to develop and assess effectiveness measures that reflect the outcomes that DHS and its components want to achieve.

Additionally, DHS has not developed performance goals and measures related to the strategic goals for its efforts to combat fentanyl trafficking. Developing performance goals related to its strategic goals would better enable DHS and stakeholders to assess the department’s progress toward disrupting the illicit fentanyl market and halting the flow of fentanyl into the U.S. Furthermore, establishing measures for its performance goals, which could be developed through the statutorily required program, would help ensure that DHS collects the information it needs to assess program performance and progress towards its goals.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following three recommendations to DHS:

The Secretary of Homeland Security should establish a program to collect data and develop measures to assess the effectiveness of technologies and strategies used to detect and deter illicit fentanyl, including its analogues and precursor chemicals, from being trafficked into the U.S. at and between ports of entry, as required by law. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of Homeland Security should ensure that the entity or entities the department tasks with establishing the required program have access to the necessary information from across the department. (Recommendation 2)

The Secretary of Homeland Security should establish performance goals and measures that relate to DHS’s strategic goals for its efforts to combat fentanyl trafficking. (Recommendation 3)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to DHS for review and comment. In its comments, reproduced in appendix III, DHS concurred with each of our recommendations. DHS also noted that it plans to take steps to address each of the recommendations. Specifically, DHS stated that it will establish the statutorily required data and measures program, which will involve identifying where the program should be situated—within a component or headquarters office—and implementing a mechanism, such as a directive, to ensure that the entity or entities tasked with establishing the program have access to the necessary information from across the department. Furthermore, DHS stated that it will develop performance goals and measures that relate to the strategic goals for its efforts to combat fentanyl trafficking. DHS also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees and the Secretary of DHS, Commissioner of CBP, and Acting Director of ICE. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions, please contact me at GamblerR@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made major contributions to this report are listed in appendix IV.

Rebecca Gambler

Director, Homeland Security and Justice

List of Committees

The Honorable Ted Cruz

Chairman

The Honorable Maria Cantwell

Ranking Member

Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation

United States Senate

The Honorable Rand Paul, M.D.

Chairman

The Honorable Gary C. Peters

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable Chuck Grassley

Chairman

The Honorable Richard J. Durbin

Ranking Member

Committee on the Judiciary

United States Senate

The Honorable Brett Guthrie

Chairman

The Honorable Frank Pallone, Jr.

Ranking Member

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

The Honorable Andrew Garbarino

Chairman

The Honorable Bennie G. Thompson

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security

House of Representatives

The Honorable Jim Jordan

Chairman

The Honorable Jamie Raskin

Ranking Member

Committee on the Judiciary

House of Representatives

The Honorable Brian Babin

Chairman

The Honorable Zoe Lofgren

Ranking Member

Committee on Science, Space, and Technology

House of Representatives

The James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 included a provision for us to review the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) efforts to collect data and develop measures to assess the effectiveness of technologies and strategies used to detect and deter illicit fentanyl, including its analogues and precursor chemicals, from being trafficked into the U.S. at and between ports of entry.[49] This report examines (1) what DHS data show about seizures of illicit fentanyl, its precursor chemicals, and production equipment from fiscal years 2021 through 2024; (2) DHS efforts to combat the trafficking of illicit fentanyl, its precursor chemicals, and production equipment into the U.S.; and (3) the extent to which DHS has assessed the effectiveness of its efforts to combat the trafficking of illicit fentanyl, its precursor chemicals, and production equipment into the U.S.[50]

To describe what DHS data show about seizures of illicit fentanyl, its precursor chemicals, and production equipment from fiscal years 2021 through 2024, we analyzed data on seizures of fentanyl, its analogues and precursor chemicals, and production equipment that occurred during the selected time frame from U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s (CBP) SEACATS and U.S. Border Patrol’s e3.[51] We selected the fiscal year 2021 through 2024 time frame for our analysis because CBP officials told us they started collecting more precise data on production equipment seizures in fiscal year 2021 and fiscal year 2024 is the most recent year for which complete data were available at the time of our review. Regarding our analysis of the SEACATS data, we only analyzed records that had quantifiable amounts and were not identified as samples or residue. As a result, we excluded 3,884 records from our analysis, which represented about 16 percent of the dataset we received.

To assess the reliability of the SEACATS and e3 seizure data, we performed electronic testing, reviewed information about the systems, compared the data to CBP’s public reports, and interviewed agency officials. When we found discrepancies—such as missing data, duplicate records, or data entry errors—we worked with officials from CBP and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s (ICE) Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) to correct the discrepancies. For example, we reclassified 15 SEACATS records that were incorrectly entered as HSI-led seizures that took place outside of the U.S., as HSI-assisted seizures. Further, we removed an additional 216 SEACATS records, which was about 1 percent of the dataset we received, based on electronic tests and our discussions with agency officials.[52]

We found these data to be sufficiently reliable for the purpose of describing the total amount and number of fentanyl, fentanyl analogue, fentanyl precursor chemical, and production equipment seizures led and assisted by DHS and each of the DHS components with primary responsibility for combating drug trafficking at and between U.S. ports of entry—CBP’s Office of Field Operations (OFO), Border Patrol, and Air and Marine Operations (AMO), and HSI—for fiscal years 2021 through 2024.[53] The number and amount of fentanyl seizures we report include seizures of fentanyl analogues because DHS entities seized or helped other agencies seize a relatively small amount of fentanyl analogues from fiscal years 2021 through 2024.[54] See below for further details on our analysis of SEACATS and e3 seizure data.

To describe DHS efforts to combat the trafficking of illicit fentanyl, its precursor chemicals, and production equipment into the U.S., we reviewed documentation on DHS’s, CBP’s, and HSI’s counter-drug efforts, including DHS’s Plan to Combat Fentanyl, CBP’s Strategy for Combating Fentanyl and Other Synthetic Drugs and Fentanyl and Fentanyl Precursor Chemicals: Fiscal Year 2023 Report to Congress, and HSI’s Strategy for Combating Illicit Opioids. We also analyzed seizure and investigative data related to DHS efforts to combat fentanyl trafficking. Specifically, we analyzed the SEACATS data to identify seizures related to CBP’s efforts to patrol and surveil the border and its use of tools such as targeting, canines, and non-intrusive inspection equipment.[55] We also analyzed summary-level data on fentanyl-related cases, indictments, arrests, convictions, disruptions, and dismantlements from fiscal years 2021 through 2024 from HSI’s Investigative Case Management system.[56]

As described above, we took numerous steps to assess the reliability of the SEACATS data. We found these data to be sufficiently reliable for the purpose of describing (1) the total weight and number of both Border Patrol-led and AMO-assisted fentanyl seizures in areas surrounding ports of entry; and (2) the minimum amount and number of fentanyl, fentanyl analogue, fentanyl precursor chemical, and production equipment seizures that involved the use of targeting, canines, and non-intrusive inspection equipment from fiscal years 2021 through 2024. We report the minimum number of seizures and amount seized involving these tools because the fields in SEACATS that we reviewed to identify the use of these tools were not required to be completed or were free-text narratives. To assess the reliability of HSI’s investigative data, we performed logic testing, reviewed information about the system, and interviewed agency officials. We found these data to be sufficiently reliable for the purpose of reporting the total and average annual number of fentanyl-related cases, indictments, arrests, convictions, disruptions, and dismantlements from fiscal years 2021 through 2024.

In addition, we interviewed CBP and HSI officials from headquarters and the field to better understand CBP and HSI efforts to combat fentanyl trafficking. At CBP headquarters, we interviewed officials from the Fentanyl Campaign Directorate, OFO, Office of Intelligence, Office of Trade, and the National Targeting Center.[57] We also visited CBP’s National Targeting Center to better understand the agency’s efforts to target shipments of fentanyl, its precursor chemicals, and production equipment and identify the organizations involved in trafficking, producing, and distributing these items. At HSI headquarters, we interviewed officials from the Narcotics and Contraband Smuggling Unit.

In the field, we interviewed CBP officials from California and Arizona including officials from three field offices; two centralized cargo examination sites; an international mail facility; three ports of entry; two Border Patrol sectors; two immigration checkpoints; two AMO branches; two regional intelligence centers; and the entity overseeing the implementation of CBP’s Operation Apollo—the agency’s national counter-fentanyl operation.[58] We also interviewed HSI officials from California, Arizona, and Texas including officials from three field offices and two HSI operations focused on disrupting the fentanyl supply chain by targeting shipments of precursor chemicals and production equipment from China.[59]

We conducted most of these interviews during in-person visits to Los Angeles and San Diego, California and Tucson, Arizona. During these visits, we observed CBP efforts and tools to combat fentanyl trafficking at three land ports of entry, an international mail facility, air and sea cargo examination facilities, and two immigration checkpoints. We selected San Diego and Tucson because, according to CBP’s public drug seizure data, these locations had the greatest number of CBP fentanyl seizures and pounds of fentanyl seized in fiscal year 2023. We selected Los Angeles because the Acting CBP Commissioner at the time of our review identified the Los Angeles International Airport—which includes CBP international mail and cargo examination facilities—as the focal point in the agency’s efforts to combat fentanyl precursor chemicals. The information we obtained from these interviews and visits cannot be generalized; however, it provided valuable insights on CBP and HSI efforts and tools to combat fentanyl trafficking.

To determine the extent to which DHS assessed the effectiveness of its efforts to combat the trafficking of illicit fentanyl, its precursor chemicals, and production equipment into the U.S., we reviewed DHS, CBP, and HSI documents describing agency goals, measures, and performance such as DHS’s Plan to Combat Fentanyl and Nationwide Fentanyl Disruption Seizure report, as well as CBP’s and HSI’s implementation plans for their respective counter-fentanyl strategies. We also reviewed recent examples of internal data reports that DHS, CBP, and HSI developed to monitor their efforts to combat fentanyl trafficking.

In addition, we interviewed officials from DHS’s Office of Program Analysis and Evaluation and Office of Strategy, Policy, and Plans as well as the CBP and HSI headquarters and field officials cited above to better understand how each agency assesses the effectiveness of its efforts to combat fentanyl trafficking including any challenges officials experience. We evaluated DHS’s efforts to assess its effectiveness at combating fentanyl trafficking against DHS’s Organizational Performance Management Guidance, GAO’s guide on evidence-based policymaking, and select key performance management practices identified in our prior work related to establishing performance measures.[60]

We also interviewed or obtained responses to questions from officials from DHS’s Office of Strategy, Policy, and Plans and Office of the Executive Secretary as well as CBP’s OFO, Office of the Executive Secretariat, and Office of Congressional Affairs to determine the status of DHS’s establishment of a statutorily required program to collect data and develop measures to assess the effectiveness of efforts to combat fentanyl trafficking into the U.S.[61] We evaluated DHS’s establishment of the required program against the applicable statutory provisions and select leading practices for interagency collaboration related to defining common outcomes, ensuring access to necessary data and information, identifying appropriate leadership models, and clarifying roles and responsibilities.[62]

Analysis of Fentanyl-Related Seizures Using DHS Data

We analyzed seizures of fentanyl, fentanyl analogues, fentanyl precursor chemicals, and production equipment that occurred during fiscal years 2021 through 2024 from SEACATS and e3. Specifically, we analyzed what and how much was seized, which agency led or assisted the seizure, where the seizure occurred, the method by which the seized item was transported, where the seized item came from, and which tools were used to detect the seized item.

Analysis of What and How Much Was Seized and the Agency That Led the Seizure

We reviewed different fields in SEACATS and e3 to identify fentanyl, fentanyl analogues, fentanyl precursor chemicals, and production equipment. Specifically, to identify fentanyl and production equipment, we reviewed the property type field in SEACATS and property subtype field in e3.