FINANCIAL COMPANY BANKRUPTCIES

Regulators Continued Efforts to Improve the Resolvability of Large Firms

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Michael E. Clements at clementsm@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107720, a report to congressional committees

FINANCIAL COMPANY BANKRUPTCIES

Regulators Continued Efforts to Improve the Resolvability of Large Firms

Why GAO Did This Study

The failure of systemically important financial companies during the 2007–2009 financial crisis highlighted challenges in resolving them under the Bankruptcy Code.

The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act includes a provision for GAO to report periodically on the effectiveness of the Bankruptcy Code in facilitating orderly liquidation or reorganization of financial companies. GAO issued five prior reports on this topic (GAO-20-608R, GAO-15-299, GAO-13-622, GAO-12-735, GAO-11-707).

This report examines (1) recent legislative changes to the Bankruptcy Code involving financial companies or to Orderly Liquidation Authority, and related agency actions; and (2) efforts by the Federal Reserve and FDIC to improve resolution plans and identify plan weaknesses.

GAO reviewed relevant laws, regulations, guidance, and agency reports. It also reviewed Federal Reserve and FDIC feedback letters on 2013–2023 plans, as well as policies and procedures for reviewing plans. For a nongeneralizable sample of 10 filers—selected because their plans had the most identified weaknesses—GAO reviewed agencies’ internal workpapers assessing 2017–2023 resolution plans. GAO also interviewed officials from the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts, FDIC, and the Federal Reserve.

What GAO Found

Large financial companies may be liquidated or reorganized under a judicial bankruptcy process or resolved under special legal and regulatory resolution regimes created to address insolvent financial institutions. This includes Orderly Liquidation Authority, which allows the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) to resolve certain financial companies outside the bankruptcy process. Congress has not significantly revised the Bankruptcy Code for resolving financial companies or Orderly Liquidation Authority since GAO’s most recent report in 2020. Nevertheless, FDIC has continued to develop its capabilities under this authority in response to a 2023 internal audit and as part of its strategic planning.

Certain large financial companies must periodically file plans describing how they could be resolved under the Bankruptcy Code in an orderly manner in the event of material financial distress or failure. In 2019, the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and FDIC revised their rule governing resolution plans, generally dividing companies into biennial and triennial filers based on their asset size and risk profile.

The Federal Reserve and FDIC review companies’ resolution plans to identify weaknesses and determine whether they are deficiencies (which could undermine a plan’s feasibility) or shortcomings (which are less severe). The agencies then send companies feedback letters outlining weaknesses companies are required to address. For a nongeneralizable sample of 10 filers, GAO found that regulators considered multiple factors when evaluating weaknesses, including the nature of the issue, its potential effect, and the likelihood that the effect would occur.

Federal Reserve and FDIC officials noted that resolution plans have “matured” as companies refined their strategies and addressed vulnerabilities. The number of identified deficiencies and shortcomings declined over time, with most weaknesses identified in 2013–2015 plans. The plans submitted by eight U.S. (biennial) and seven foreign (triennial) global systemically important banks accounted for all the deficiencies and nearly all the shortcomings. As of the last plan submissions, 79 financial companies were required to file plans.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

Code |

U.S. Bankruptcy Code |

|

Dodd-Frank Act |

Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act |

|

FBO |

foreign banking organization |

|

FDIC |

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation |

|

Federal Reserve |

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System |

|

IDI |

insured depository institution |

|

GSIB |

global systemically important bank |

|

OIG |

Office of Inspector General |

|

OLA |

Orderly Liquidation Authority |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

July 21, 2025

Congressional Committees

The failure of systemically important financial companies during the 2007–2009 financial crisis exposed challenges in resolving such companies under the U.S. Bankruptcy Code (Code) without causing further harm to the U.S. financial system. In response, Congress established the Orderly Liquidation Authority (OLA) under the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. OLA provides a regulatory alternative to bankruptcy for resolving certain failing financial companies, including systemically important financial institutions.

The Dodd-Frank Act also requires certain financial companies to file periodic resolution plans.[1] These plans, submitted to the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), must describe how the companies could be resolved under the Code in an orderly manner in the event of material financial distress or failure.[2] The Federal Reserve and FDIC must review a company’s resolution plan. If the agencies jointly determine that its plan is not credible or would not facilitate an orderly resolution under the Code, the agencies must notify the company of the deficiencies, and the company must submit a revised plan to address deficiencies identified by regulators.

The Dodd-Frank Act also includes a provision for us to study, at specified intervals, the effectiveness of the Code in facilitating orderly liquidation or reorganization of financial companies and ways to make orderly liquidation under the Code more effective.[3] This report examines (1) legislative changes to the Code involving financial companies or OLA since our last report in 2020 and related agency actions, and (2) efforts by the Federal Reserve and FDIC to improve resolution plans and identify plan weaknesses.

For the first objective, we analyzed legislation that was proposed and enacted from April 2020 through January 2025 and designed to revise the liquidation or reorganization of financial companies under relevant chapters of the Code or OLA. We reviewed proposed and final rules related to OLA issued by the Federal Reserve, FDIC, or other regulators during this period. To assess FDIC’s efforts to improve its OLA planning and capabilities, we reviewed agency reports, strategic plans, and related materials, including from the FDIC Office of Inspector General. We also reviewed relevant provisions of the Dodd-Frank Act, prior GAO reports, and other materials to assess whether the three regional banks that failed in spring 2023 could have been resolved under OLA.[4] We interviewed staff of the Administrative Office of the United States Courts about any relevant changes to the Code since April 2020. We also interviewed Federal Reserve and FDIC officials about OLA, including its potential use to resolve the regional banks that failed in 2023.

For the second objective, we reviewed resolution plan guidance issued by the Federal Reserve and FDIC from 2019 through 2024, as well as their 2019 resolution plan rule, and internal policies and procedures for reviewing plans and vetting potential findings.[5] We reviewed proposed and final rules related to resolution planning issued by the Federal Reserve, FDIC, or other regulators from April 2020 through January 2025.

To assess how the agencies identified and classified plan weaknesses, we analyzed feedback letters sent to companies, covering plans filed in 2013 through 2023.[6] We analyzed the number and types of identified plan weaknesses (deficiencies or shortcomings) and whether companies addressed such weaknesses within specified time frames. We analyzed Federal Reserve and FDIC workpapers summarizing findings of reviews of resolution plans submitted in 2017 through 2023 for a nongeneralizable sample of 10 biennial and triennial full filers.[7] This analysis helped identify factors the agencies used to classify plan weaknesses as deficiencies or shortcomings. We reviewed agency policies and guidance for determining whether an identified plan weakness may be classified as a deficiency or shortcoming. Finally, we interviewed Federal Reserve and FDIC officials about their review processes and classification criteria.

We conducted this performance audit from July 2024 to July 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Resolution Process and Regimes

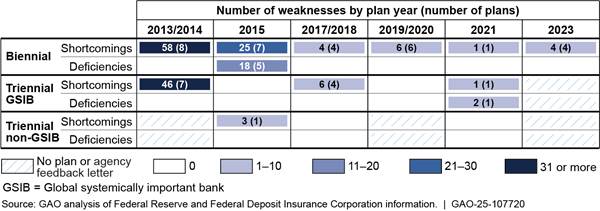

Large financial companies may be liquidated or reorganized under a judicial bankruptcy process or resolved under special legal and regulatory resolution regimes created to address insolvent financial institutions (see fig. 1).

aThis figure excludes broker-dealers, commodity

brokers, and insurance companies. Chapter 7 of the Bankruptcy Code contains

special provisions for liquidations of broker-dealers and commodity brokers. In

addition, certain broker-dealers may be liquidated under the Securities

Investor Protection Act of 1970, codified at 15 U.S.C. 78aaa-78lll.

bBankruptcy prohibited by law.

cThe Secretary of the Treasury, in consultation with the President,

determines, upon the recommendation of at least two-thirds of the members of

the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve and (depending on the nature of

the financial company or its largest U.S. subsidiary) two-thirds of the members

of the Board of Directors of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation,

two-thirds of the members of the Securities and Exchange Commission, or the

Director of the Federal Insurance Office, that, among other things, the company

is in default or danger of default and the company’s failure and its resolution

under applicable law, including bankruptcy, would have serious adverse effects

on U.S. financial stability and no viable private-sector alternative is

available to prevent default.

Bankruptcy: Bankruptcy is a federal court procedure, the goal of which is to help eliminate or restructure debts individuals and businesses cannot repay and to help creditors receive some payment in an equitable manner. Business debtors may seek liquidation, governed primarily by Chapter 7 of the Code, or reorganization, governed by Chapter 11. Chapters 7 and 11 petitions can be voluntary (initiated by the debtor) or involuntary (generally initiated by at least three creditors holding at least a certain minimum dollar amount in claims against the debtor).

Orderly Liquidation Authority: Title II of the Dodd-Frank Act established OLA, which gives FDIC the authority, subject to certain constraints, to resolve certain financial companies, including a bank holding company or certain nonbank financial companies, outside of the bankruptcy process.[8] This authority allows for FDIC to be appointed receiver for a financial company if the Secretary of the Treasury determines, among other things, that the company is in default or danger of default. The Secretary also must determine that the company’s failure and its resolution under applicable law, including bankruptcy, would have serious adverse effects on U.S. financial stability and no viable private-sector alternative is available to prevent the default.[9]

Resolution Plans

Title I of the Dodd-Frank Act requires certain financial companies to provide the Federal Reserve, FDIC, and the Financial Stability Oversight Council with periodic reports on their plans for rapid and orderly resolution under the Code in the event of “material financial distress or failure.”[10] As discussed previously, the Federal Reserve and FDIC must review the resolution plans. If they jointly determine and notify a company in writing that its plan is not credible or would not facilitate an orderly resolution under the Code, the financial company would have to submit a revised plan to address deficiencies identified by regulators.

In November 2019, the Federal Reserve and FDIC finalized amendments to the resolution plan rule, which in part addressed statutory changes made by the 2018 Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act.[11] The joint rule, which aims to better match resolution planning requirements to the risks of the covered companies, made the following key changes:

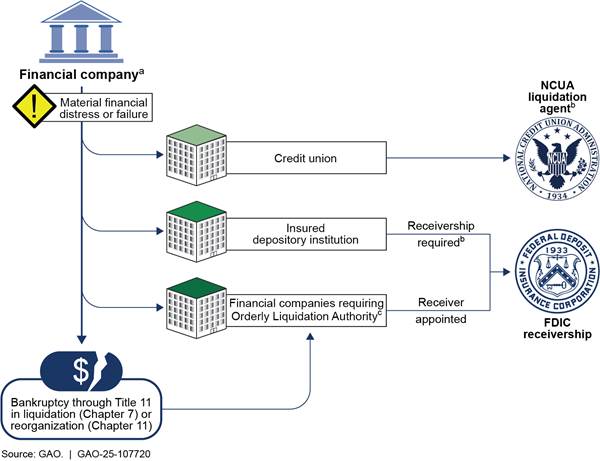

· Raised minimum asset size thresholds and created risk-based indicators and categories for covered companies based on asset size and risk profile (see fig. 2)[12]

· Lengthened the filing cycle for plan submissions from annual to biennial or triennial, depending on the category

· Established content requirements for new plan types (targeted and reduced) and a schedule alternating between full and targeted plans for biennial and triennial full filers

· Formalized critical operations requirements by establishing processes to be used by covered companies and agencies to identify operations of companies most important to U.S. financial stability[13]

· Imposed time requirements for regulators to provide feedback to covered companies on their resolution plan

This figure summarizes which U.S. and foreign financial companies are required to file resolution plans by category based on asset thresholds or risk indicators, which determines the type and frequency of their required plans.

Notes: All metrics are calculated as four-quarter averages. GSIBs are banking organizations whose distress or disorderly failure could cause significant disruption to the wider financial system and economy (because of attributes such as their size, complexity, and interconnectedness). Triennial full and reduced filers include some foreign GSIBs. The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System established criteria for identifying a GSIB in 2015. See Regulatory Capital Rules: Implementation of Risk-Based Capital Surcharges for Global Systemically Important Bank Holding Companies, 80 Fed. Reg. 49,082 (Aug. 14, 2015).

Bankruptcy and Orderly Liquidation Regimes Largely Unchanged Since 2020, but FDIC Continued to Develop Its Resolution Processes

Bankruptcy Code and OLA Have Remained Substantially Unchanged Since 2020

Since our last report in 2020, Congress has not substantively revised the Code for resolving financial companies or OLA. Congress enacted several technical changes to the Code from April 2020 to January 2025, including threshold adjustments for inflation. Members of Congress also introduced many bills proposing amendments to the Code. Those bills spanned numerous topics, including protecting employee benefits in bankruptcy and restricting special compensation payments to executives and other highly compensated employees in the event of a bankruptcy. None of the enacted or proposed legislation specifically targeted financial companies.

Congress enacted a technical amendment to OLA during the period we reviewed.[14] Additionally, legislators introduced—but did not enact—several bills that would have expanded FDIC’s authority under OLA to recover (or “clawback”) compensation of parties responsible for a financial company’s financial losses.

FDIC Issued One Rule and Proposed Expanding Another to Strengthen OLA

Since our last report in July 2020, FDIC issued a joint final rule to clarify an OLA provision and separately proposed a joint rule on long-term debt aimed at increasing resolution options for a larger number of financial companies:

· Final rule on broker-dealer resolution under OLA. In August 2020, FDIC and the Securities and Exchange Commission finalized a rule to implement provisions applicable to the orderly liquidation of covered brokers and dealers under OLA.[15] The rule, among other things, clarifies the distribution of responsibilities between the two agencies and the Securities Investor Protection Corporation in the event of a broker-dealer’s failure.[16] It also allows FDIC, as receiver, to establish one or more bridge broker-dealers to maintain day-to-day activities of the broker-dealer and prevent a distressed sale of the assets, among other potential benefits.

· Proposed rule on long-term debt. In September 2023, FDIC, the Federal Reserve, and Office of the Comptroller of the Currency issued a proposed rule that would require certain large bank holding companies and banks to issue and maintain a minimum amount of long-term debt.[17] Because such debt can be used to absorb losses, the proposed rule is intended to increase the options available to resolve a covered insured depository institution (IDI) in case of failure.[18] Global systemically important banks (GSIB) are already subject to long-term debt requirements.[19] This proposed rule would expand the companies subject to these long-term debt requirements.

FDIC Took Actions to Address Inspector General’s OLA Recommendations and Included OLA in Its Strategic Planning

FDIC took actions to respond to recommendations from its Office of Inspector General (OIG) and incorporated OLA-related goals into its broader strategic planning efforts.

Office of the Inspector General recommendations. In 2023, FDIC’s OIG reported that FDIC had made progress implementing elements of its OLA program, including on OLA resolution planning for U.S. GSIBs.[20] However, the OIG found FDIC had not maintained a consistent focus on maturing the OLA program and had not fully established key elements to execute its OLA responsibilities.

· The OIG made 17 recommendations to strengthen FDIC’s ability to execute its OLA responsibilities. According to the office, FDIC concurred with all the recommendations and proposed corrective actions that were sufficient to address their intent.

· As of March 2025, FDIC had fully addressed seven of the recommendations, according to OIG officials. Actions taken included assessing the baseline resources needed for an OLA team, establishing an operational readiness exercise program, and establishing performance metrics for the OLA program, according to OIG officials.

· Recommendations not fully addressed as of that date included enhancing policies and procedures for resolution implementation and putting in place institution-specific resolution planning documents for systemically important nonbank financial companies and financial market utilities. FDIC officials told us they were working to fully address the remaining recommendations but noted that planned staffing reductions may affect the timing of their corrective actions.

Strategic planning. In response to the OIG recommendations, in February 2024 FDIC adopted a performance goal as part of its strategic planning: to strengthen operational readiness to resolve a systemically important large, complex financial institution.[21] Under this performance goal, the agency plans to develop additional OLA policies, procedures, and resolution planning documents for GSIBs, systemically important central counterparties, and designated financial market utilities. FDIC also plans to establish action plans for developing OLA regulations required by the Dodd-Frank Act related to risk-based assessments and banning certain activities by senior executives.

FDIC Issued a Report on Its OLA Resolution Process

In 2024, FDIC issued a report explaining how the agency expected to use OLA in practice to resolve a U.S. GSIB in an orderly manner.[22] The report’s goal was to enhance transparency and promote public understanding of the resolution process under OLA. According to the then FDIC Chairman, the report provided the most comprehensive detail to date on FDIC’s operational steps for resolving a U.S. GSIB under OLA. The Chairman also noted that while the report focused on a U.S. GSIB, many of the plans and processes described would apply to other types of systemically important financial companies.

As discussed in the report, unless circumstances require otherwise, FDIC expects to use a single point of entry strategy to resolve a U.S. GSIB under OLA.[23] The operational steps under this type of resolution strategy generally are the following:

· Launching the resolution. FDIC would be appointed receiver of the parent holding company and transfer its subsidiaries, assets, and certain liabilities to a bridge financial company.

· Stabilizing operations. FDIC would take steps to stabilize the bridge financial company and its operations by recapitalizing material subsidiaries with the firm’s internal resources, providing adequate liquidity to the group, replacing the most senior leadership while retaining key personnel, communicating with stakeholders, and maintaining operational continuity.

· Exiting the resolution. FDIC and the bridge financial company’s management would develop and implement a restructuring and wind-down plan, which might include selling or liquidating subsidiaries or business lines.

|

Orderly Liquidation Authority (OLA) Not Used for Regional Bank Failures in 2023 Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank failed on March 10 and 12, 2023 (respectively), and First Republic Bank failed on May 1, 2023. State banking regulators closed each institution at the time of its failure. At that time, they were among the 30 largest U.S. banks. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) was named the receiver of the three banks and generally sold them. Signature Bank and First Republic Bank were insured depository institutions without a parent holding company. Insured depository institutions are excluded from resolution under OLA. Therefore, OLA was not an option for resolving them, according to FDIC officials. In contrast, Silicon Valley Bank had a parent holding company, SVB Financial Group, that entered bankruptcy and subsequently was liquidated. OLA was not used to resolve SVB Financial Group. However, according to FDIC officials, OLA could have been used if the holding company’s resolution under the Bankruptcy Code would have had serious adverse effects on U.S. financial stability, among other criteria. For the holding company of a regional bank, such as SVB Financial Group, the insured depository institution often comprises the largest asset of the bank holding company, and the holding company’s other assets generally do not pose systemic risk, according to FDIC officials. FDIC resolves insured depository institutions under the Federal Deposit Insurance Act, which has a systemic risk exception for resolutions that do not meet the least cost test. Under this exception, FDIC can provide certain emergency assistance when resolving a failed bank if, upon the recommendation of FDIC and the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, and in consultation with the President, the Treasury Secretary determines that it would avoid or mitigate serious adverse effects on the economy or financial stability. On March 12, 2023, the Secretary approved the systemic risk exception for Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank. For additional information, see GAO, Bank Regulation: Preliminary Review of Agency Actions Related to March 2023 Bank Failures, GAO‑23‑106736 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 28, 2023); and Federal Deposit Insurance Act: Federal Agency Efforts to Identify and Mitigate Systemic Risk from the March 2023 Bank Failures, GAO‑25‑107023 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 23, 2025). |

Source: GAO analysis of FDIC information and GAO reports. I GAO‑25‑107720

Agencies Have Provided Guidance and Feedback to Improve Resolution Plans

Federal Reserve and FDIC Issued Guidance to Improve Companies’ Resolution Plans

Since our last report in 2020, the Federal Reserve and FDIC have continued their efforts to improve resolution plans through plan guidance and feedback issued following plan reviews. In August 2024, the agencies issued guidance for triennial foreign and domestic filers that submit full plans.[24] The guidance does not have the force of law. Rather, it describes the agencies’ expectations and priorities for these companies’ plans.[25]

· The new guidance consolidates prior guidance and is informed by agency reviews of past triennial full filer plans and the agencies’ experiences with the 2023 regional bank failures. For example, in reviewing the 2021 targeted triennial full filer resolution plans, the agencies found inconsistencies in the amount and nature of information submitted. They also found that some of the plans included optimistic assumptions about the availability of resources in bankruptcy or access to financial assistance before and during resolution.

· The guidance identifies key challenges in resolution and describes expectations for how companies should address them. These challenges vary by resolution strategy and include capital, liquidity, governance mechanisms, operations, legal entity rationalization, and resolution of IDIs.

· The guidance does not prescribe a specific resolution strategy but identifies and discusses the different considerations, challenges, and vulnerabilities that should be addressed for resolution strategies with single point of entry or multiple point of entry resolution.[26] For example, the guidance on multiple point of entry focuses on separate resolution of the material legal entities because the holding company typically files for bankruptcy, the FDIC-insured bank subsidiary is resolved by FDIC, and other entities separately enter the appropriate resolution regimes.

· Unlike biennial filers that all use a single point of entry strategy, most triennial full filers use a multiple point of entry strategy, according to the agencies.

In July 2024, FDIC finalized a rule revising the frequency and content of resolution plans for IDIs that must be submitted by certain large banks.[27] FDIC adopted the IDI rule to facilitate its readiness to resolve a failed bank. While the IDI rule and resolution plan rule serve different purposes, the rules are complementary. For example, the IDI rule would help FDIC be prepared to resolve a bank subsidiary under a multiple point of entry resolution strategy, which most triennial full filers use.[28]

Agency officials told us that they did not plan to update the 2019 guidance to biennial filers. They said the 2019 guidance was developed in conjunction with the 2019 resolution plan rule and has been effective. However, the agencies provided additional direction to biennial filers as part of their feedback on the 2023 plans. For example, the feedback letters provided additional information on derivatives portfolio segmentation and detailed the components of an effective resolution assurance framework.[29]

Agencies Continue to Review Resolution Plans to Identify Weaknesses and Provide Feedback

The Federal Reserve and FDIC both review companies’ resolution plans to identify and determine the severity of any weakness. In the 2019 resolution plan rule, the agencies defined two categories of weaknesses: deficiency and shortcoming.[30] A deficiency generally is a weakness that agencies jointly determine could undermine the feasibility of a resolution plan. A shortcoming generally is a weakness or gap that raises questions about a plan’s feasibility but does not rise to the level of a deficiency for both agencies.[31]

According to agency officials, their senior staffs and boards largely use their professional judgment and consider each company’s unique characteristics when assessing whether an identified weakness might rise to the level of a shortcoming or deficiency. Depending on the firm, agency staff conducts a joint review of the resolution plan or an independent review of the resolution plan followed by coordination with each other.[32] Based on these reviews, the agencies’ senior staffs assess whether identified weaknesses may be deficiencies or shortcomings and make recommendations to their respective boards.[33] Each board then determines whether a weakness constitutes a deficiency or shortcoming.

If the agencies’ boards disagree on whether a weakness is a shortcoming or a deficiency, the finding is classified as a shortcoming. If they disagree on whether it is a shortcoming, the finding is described in the feedback letter but not characterized as a formal finding.[34]

The agencies send feedback letters to notify companies of weaknesses identified in their plan reviews. Companies generally are required to remedy deficiencies within 90 days and remedy shortcomings in their next plan submission.[35]

We analyzed Federal Reserve and FDIC workpapers provided to their boards for 27 resolution plans submitted from 2017 through 2023 by 10 biennial and triennial full filers.[36] We found that agency staffs considered multiple factors when assessing whether a weakness might rise to the level of a shortcoming or deficiency. These factors included the nature of the weakness, its potential effect, and the likelihood that the weakness would have that effect.

GSIBs Accounted for Most Identified Plan Weaknesses and Generally Met Remediation Deadlines

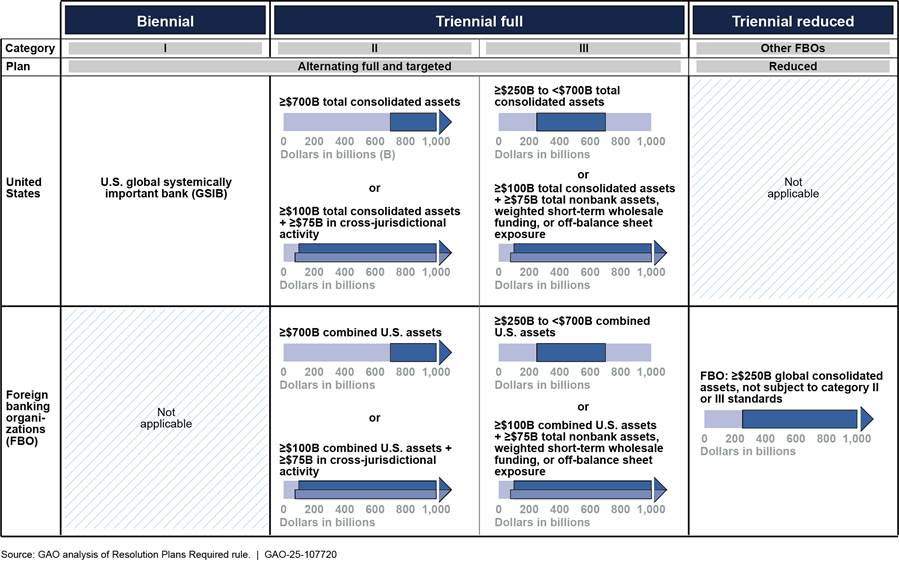

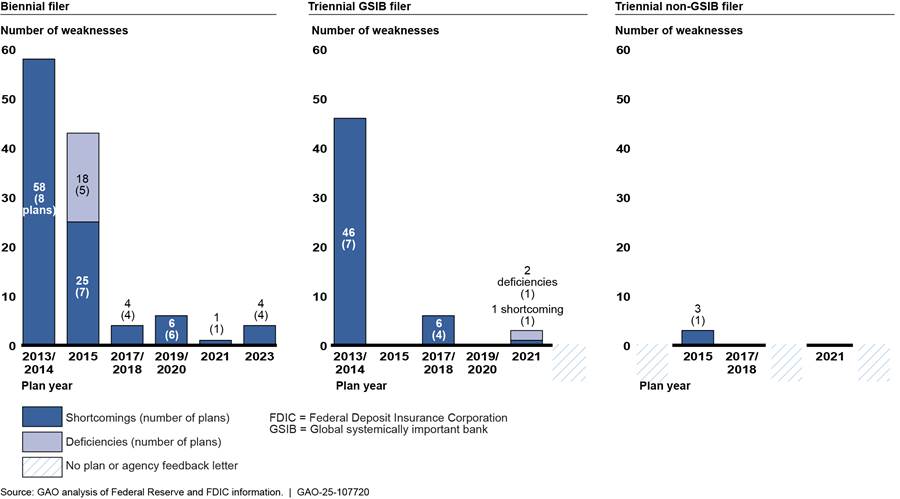

The agencies first began to identify shortcomings in companies’ 2013 resolution plans. Based on our analysis of the Federal Reserve and FDIC’s feedback letters, U.S. and foreign GSIBs accounted for all the deficiencies and nearly all the shortcomings in resolution plans (see fig. 3). As of the last plan submissions, 79 financial companies were required to file plans.[37]

· The agencies jointly identified 20 deficiencies, all in plans submitted by U.S. GSIBs (biennial filers) and foreign GSIBs (triennial filers).[38] Of these, the agencies found 18 deficiencies in five plans submitted by biennial filers in 2015. Since then, the agencies have not identified any deficiencies in plans submitted by U.S. GSIBs. The agencies identified two deficiencies in a plan filed by a foreign GSIB in 2021.

· The agencies also identified 151 shortcomings in the plans submitted by U.S. and foreign GSIBs, which accounted for 98 percent of all shortcomings. They identified multiple shortcomings in plans submitted by the eight U.S. GSIBs and seven foreign GSIBs.

· The agencies identified most of the total number of shortcomings and deficiencies (86 percent) in plans submitted from 2013 through 2015. Since then, the agencies identified relatively few shortcomings and deficiencies in each review cycle.

Figure 3: Number of Deficiencies and Shortcomings in Resolution Plans of Financial Companies, 2013–2023

Notes: GSIBs are banking organizations whose distress or disorderly failure could significantly disrupt the wider financial system and economy. We identified biennial and triennial filers based on the groupings established in the 2019 resolution plan rule, although some of the companies have changed groups over time or are no longer required to file resolution plans. Resolution Plans Required, 84 Fed. Reg. 59,194 (Nov. 1, 2019).

Our review of feedback letters generally found that companies addressed the

identified deficiencies and shortcomings within the time frames specified in

feedback letters.[39]

For deficiencies, the letters typically required submission within 90 days. For

shortcomings, companies generally were required to address them in their next

resolution plan.

According to agency officials, resolution plans have matured over time as the regulators and the companies developed greater knowledge about the requirement and resolvability challenges. The agencies’ review and feedback initially focused on fundamental issues. Over time, they shifted to also evaluating the substance of the resolution strategy and the capabilities needed to implement them.

Based on our review of feedback letters, the agencies identified plan weaknesses across the six key vulnerabilities for biennial filers and five for triennial full filers (see fig. 4).[40] In their guidance, the agencies identified key vulnerabilities that filers generally are expected to address, as applicable, to support orderly resolution under the Code. The vulnerabilities cover (1) capital, (2) liquidity, (3) governance mechanisms, (4) operational, (5) legal entity rationalization and separability, and (6) derivatives and trading activities.[41]

Plan weaknesses identified by agencies reflect the following patterns:

· For biennial filers with plan weaknesses, the agencies found the greatest number of weaknesses in the liquidity and operational areas. They also found weaknesses in the derivatives and trading activities area across four of their review cycles.

· For triennial full filers with plan weaknesses, the agencies also found the greatest number of weaknesses in the liquidity and operational areas, across five review cycles.

· The agencies have not identified any weaknesses in the capital area after 2015.

Figure 4: Deficiencies and Shortcomings in Resolution Plans of Financial Companies, by Type of Vulnerability and Type of Filer, 2013–2023

Note: We used the 2019 resolution plan rule groupings of biennial and triennial filers to analyze and categorize identified plan weaknesses, although some of the companies have changed groups over time or are no longer required to file resolution plans. Resolution Plans Required, 84 Fed. Reg. 59,194 (Nov. 1, 2019).

According to agency officials, the governance mechanisms, liquidity, operational, and derivatives areas generally form the core elements of resolution plans and are interconnected.[42] They said the agencies generally assess and test these areas regularly, with some tested during each review cycle. For example, GSIBs must be able to calculate their capital and liquidity needs not only to support their decision to file for bankruptcy but also to ensure they can fund their subsidiaries in the period before the parent holding company files and thereafter at least until markets and the firm’s condition stabilize. These funding calculations also can affect a GSIB’s ability to unwind its derivatives portfolio, which can be a source of systemic risk during times of market stress.[43]

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to the Federal Reserve, FDIC, and the Administrative Office of the United States Courts for review and comment. The agencies provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Chair of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Acting Chairman of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Director of the Administrative Office of the United States Courts, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at clementsm@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix I.

Michael E. Clements

Director, Financial Markets and Community Investment

List of Committees

The Honorable Tim Scott

Chairman

The Honorable Elizabeth Warren

Ranking Member

Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable Charles E. Grassley

Chairman

The Honorable Richard J. Durbin

Ranking Member

Committee on the Judiciary

United States Senate

The Honorable French Hill

Chairman

The Honorable Maxine Waters

Ranking Member

Committee on Financial Services

House of Representatives

The Honorable Jim Jordan

Chairman

The Honorable Jamie Raskin

Ranking Member

Committee on the Judiciary

House of Representatives

GAO Contact

Michael E. Clements, clementsm@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Richard Tsuhara (Assistant Director), Katherine Carter (Analyst in Charge), Lauren Capitini, Joseph Cruz, Robert Dacey, Rachel DeMarcus, Gretta Goodwin, Anar Jessani, Marc Molino, and Barbara Roesmann made key contributions to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]Pub. L. No. 111-203, Title I, § 165(d), 123 Stat. 1376, 1426-1427 (2010) (codified at 12 U.S.C. § 5365(d)).

[2]The Federal Reserve and FDIC must make these resolution plans available to the Financial Stability Oversight Council upon request. 12 C.F.R. § 243.4(g), 12 C.F.R. § 381.4(g).

[3]Pub. L. No. 111-203, § 202(e), 124 Stat. 1376, 1448-1449 (2010) (codified at 12 U.S.C. § 5382(e)). Also see GAO, Financial Company Bankruptcies: Congress and Regulators Have Updated Resolution Planning Requirements, GAO‑20‑608R (Washington, D.C.: July 21, 2020); Financial Company Bankruptcies: Information on Legislative Proposals and International Coordination, GAO‑15‑299 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 19, 2015); Financial Company Bankruptcies: Need to Further Consider Proposals’ Impact on Systemic Risk, GAO‑13‑622 (Washington, D.C.: July 18, 2013); Bankruptcy: Agencies Continue Rulemakings for Clarifying Specific Provisions of Orderly Liquidation Authority, GAO‑12‑735 (Washington, D.C.: July 12, 2012); and Bankruptcy: Complex Financial Institutions and International Coordination Pose Challenges, GAO‑11‑707 (Washington, D.C.: July 19, 2011).

[4]Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank failed in March 2023, and First Republic Bank failed in May 2023.

[5]Resolution Plans Required, 84 Fed. Reg. 59,194 (Nov. 1, 2019).

[6]As of May 1, 2025, the most recently available feedback letters covered resolution plans submitted by July 1, 2023.

[7]There were eight biennial and 16 triennial full filers based on their 2023 and 2021 plan submissions, respectively. We judgmentally selected four biennial filers and six triennial full filers, because their plans had the most identified weaknesses for plans filed from 2013 through 2023. Resolution plan requirements use consolidated asset thresholds and complexity factors to determine whether a company is a triennial full filer or triennial reduced filer. A full filer must submit a detailed plan that describes how the company could be resolved in a rapid and orderly manner under the Code in the event of material financial distress or failure. Subsequent to an initial full plan filing, a reduced filer must submit a plan that describes any material changes experienced by the company since its last filing and any changes to the strategic analysis presented in the last filing. 12 C.F.R. §§ 243.4(b), (c), 243.7 (Federal Reserve Board) and 12 C.F.R. §§ 381.4(b), (c), 381.7 (FDIC). See also 12 C.F.R. §§ 243.2, 381.2, 252.5.

[8]Pub. L. No. 111-203, § 204, 124 Stat. 1376, 1454-1456 (2010). Nonbank financial companies are domestic or foreign companies that predominantly engage in financial activities (such as insurance companies, consumer finance providers, commercial lenders, asset managers, investment funds, and financial market utilities) but are not bank holding companies or certain other types of institutions (such as registered securities exchanges, clearing agencies, and swap execution facilities). Holding companies own or control one or more subsidiary companies.

[9]In determining whether to appoint FDIC as receiver, the Secretary of the Treasury is to consult with the President, upon the recommendation of two-thirds of the members of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and (depending on the nature of the financial company or its largest U.S. subsidiary) two-thirds of the members of the Board of Directors of FDIC, two-thirds of the members of the Securities and Exchange Commission, or the Director of the Federal Insurance Office. The factors the Secretary of the Treasury is to consider are set forth in Section 203(b) of the Dodd-Frank Act. Pub. L. No. 111-203, § 203(b), 124 Stat. 1376, 1451 (2010) (codified at 12 U.S.C. § 5383(b)).

[10]Rapid and orderly resolution means a reorganization or liquidation of the covered company (or, in the case of a covered company that is incorporated or organized in a jurisdiction other than the United States, the subsidiaries and operations of such foreign company that are domiciled in the United States) under the Code that can be accomplished within a reasonable period of time and in a manner that substantially mitigates the risk that the failure of the covered company would have serious adverse effects on financial stability in the United States. 12 C.F.R. § 243.2; 12 C.F.R. § 381.2.

[11]Resolution Plans Required, 84 Fed. Reg. 59,194 (Nov. 1, 2019). The 2019 joint rule implements the resolution plan requirement found in the Dodd-Frank Act, Sec. 165(d). Pub. L. No. 111-203, § 165(d), 124 Stat. 1376, 1423-1432 (2010) (codified at 12 U.S.C. § 5365(d)).

[12]The categories were consistent with a broader recategorization of financial companies under the Federal Reserve’s 2019 “Tailoring Rule,” which establishes risk-based categories for determining prudential standards for large U.S. banking organizations and foreign banking organizations, consistent with statutory requirements. See Prudential Standards for Large Bank Holding Companies, Savings and Loan Holding Companies, and Foreign Banking Organizations, 84 Fed. Reg. 59,032 (Nov. 1, 2019).

[13]The rule defines these critical operations as those of a covered company, including associated services, functions, and support, the failure or discontinuance of which would pose a threat to U.S. financial stability. 12 C.F.R. §§ 243.2, 381.2.

[14]The amendment revised 12 U.S.C. § 5391(d)(3) to refer to the U.S. Code instead of the Inspector General Act of 1978. Pub. L. No. 117-286, § 4(B)(36), 136 Stat. 4347 (Dec. 27, 2022).

[15]Covered Broker-Dealer Provisions Under Title II of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, 85 Fed. Reg. 53,645 (Aug. 31, 2020).

[16]The Securities Investor Protection Act of 1970, as amended, created the Securities Investor Protection Corporation to restore funds and securities to investors and to protect the securities markets from disruption following the failure of broker-dealers.

[17]The proposed rule, if adopted, would apply to certain large depository institution holding companies, U.S. intermediate holding companies of foreign banking organizations, and certain insured depository institutions. Long-Term Debt Requirements for Large Bank Holding Companies, Certain Intermediate Holding Companies of Foreign Banking Organizations, and Large Insured Depository Institutions, 88 Fed. Reg. 64,524 (Sept. 19, 2023).

[18]The proposed rule also is intended to improve the likelihood of an orderly and cost-effective resolution for these covered IDIs and minimize costs to the Deposit Insurance Fund. The Fund, which is supported mainly by assessments on FDIC-insured institutions, is used to insure the deposits and protects the depositors of insured banks up to a statutory amount and is used to resolve failed banks. Losses (primarily from bank failures) and operating expenses reduce the Fund’s balance.

[19]See 12 C.F.R. part 252, subpart G. GSIBs are banking organizations whose distress or disorderly failure could cause significant disruption to the wider financial system and economy (because of attributes such as their size, complexity, and interconnectedness). The Federal Reserve established criteria for identifying a GSIB in 2015. See Regulatory Capital Rules: Implementation of Risk-Based Capital Surcharges for Global Systemically Important Bank Holding Companies, 80 Fed. Reg. 49,082 (Aug. 14, 2015). In addition, the Financial Stability Board, in consultation with Basel Committee on Banking Supervision and national authorities, publishes an annual list that identifies GSIBs. The Financial Stability Board is an international body that monitors and makes recommendations about the global financial system, and its U.S. members include the Federal Reserve, Securities and Exchange Commission, and Department of the Treasury.

[20]Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Office of Inspector General, The FDIC’s Orderly Liquidation Authority, EVAL-23-004 (Arlington, Va.: Sept. 28, 2023).

[21]FDIC included a similar strategic objective on OLA in its 2022–2026 strategic plan, which stated that the agency would carry out an orderly resolution if a large, complex institution failed. Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, 2022–2026 Strategic Plan (Washington, D.C.: December 2021).

[22]Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Overview of Resolution Under Title II of the Dodd-Frank Act (Washington, D.C.: April 2024).

[23]Under a single point of entry strategy, FDIC generally would place one entity (the parent holding company in the case of U.S. GSIBs) into resolution, while the ownership interests in the underlying subsidiaries would be transferred from the failed parent to a new bridge financial company.

[24]See Guidance for Resolution Plan Submissions of Domestic Triennial Full Filers, 89 Fed. Reg. 66,388 (Aug. 15, 2024); and Guidance for Resolution Plan Submissions of Foreign Triennial Full Filers, 89 Fed. Reg. 66,510 (Aug. 15, 2024). This guidance to foreign full filers supersedes the previous guidance to certain of these filers. Guidance for Resolution Plan Submissions of Certain Foreign-Based Covered Companies, 85 Fed. Reg. 83,557 (Dec. 22, 2020).

[25]The agencies made the guidance available for public comment by publishing the proposed and final guidance in the Federal Register.

[26]In a single point of entry strategy, the top-tier legal entity (such as the parent holding company) would be placed into resolution. Its material subsidiaries would remain open and operating in most instances through the transfer of the interests in the underlying subsidiaries to a bridge entity, which then would manage an orderly resolution of the group. In a multiple point of entry strategy, the company’s resolution would be implemented by placing distinct subsidiaries or subgroups into different insolvency regimes at the beginning of the resolution process and managing multiple resolution processes independently.

[27]This final IDI rule requires the submission of resolution plans by IDIs with $100 billion or more in total assets and informational filings by IDIs with at least $50 billion but less than $100 billion in total assets. Resolution Plans Required for Insured Depository Institutions With $100 Billion or More in Total Assets; Informational Filings Required for Insured Depository Institutions With at Least $50 Billion but Less Than $100 Billion in Total Assets, 89 Fed. Reg. 56,620 (July 9, 2024). On April 18, 2025, FDIC announced that it was exempting IDIs from certain content requirements of the rule, such as the requirements to utilize a bridge bank strategy and a hypothetical failure scenario.

[28]The resolution plan rule’s requirements also are focused on financial stability and mitigating systemic risk. In contrast, the IDI rule’s requirements are focused on FDIC’s readiness to resolve a particular bank.

[29]Derivatives portfolio segmentation includes the covered company demonstrating the ability to model the unwind of its derivatives portfolio by counterparty for segmenting the portfolio in resolution. Assurance is the process of identifying, testing, and reporting on resolution capabilities. An assurance framework provides the governance, policies, and procedures to carry out this process.

[30]Resolution Plans Required, 84 Fed. Reg. 59,194 (Nov. 1, 2019). In the proposed rule, the agencies noted that they defined the terms deficiency and shortcoming in a public statement in 2016 but had not defined the terms in the 2011 rule. In the proposed rule, the agencies sought public comment on these terms and aimed to more clearly articulate the standards used to identify deficiencies and shortcomings. Resolution Plans Required, 84 Fed. Reg. 21,600 and 21,613 (May 14, 2019).

[31]12 C.F.R. § 243.8(b), (e) (Federal Reserve); 12 C.F.R. § 381.8(b), (e) (FDIC).

[32]The agencies use subject matter experts to conduct firm-specific resolution plan reviews across multiple companies, considering unique aspects of each firm’s business model. For U.S. GSIBs, the agencies typically conduct these reviews jointly. For other companies, the agencies conduct separate reviews and share their findings with each other before submitting them to their respective boards.

[33]After completing their plan reviews, staff prepare workpapers that summarize their areas of concern and document key issues and areas identified for further discussion. For U.S. GSIBs only, agency staffs hold vetting sessions to discuss the preliminary findings. After vetting, the agency staffs strive to develop agreed-upon recommendations to present to their boards.

[34]Our review of feedback letters identified seven cases in which the agencies disagreed whether a weakness was a deficiency, and one case in which they disagreed on whether it constituted a shortcoming.

[35]The agencies may jointly specify a shorter or longer period than 90 days to remedy deficiencies. A shortcoming not addressed in the next resolution plan may remain outstanding or be found to be a deficiency. 12 C.F.R. § 243.8(c) (Federal Reserve Board), 12 C.F.R. § 381.8(c) (FDIC). If the agencies jointly agree that the company has not adequately remediated the deficiency, they may jointly impose more stringent prudential requirements or other operational restrictions on the company until it remediates the deficiency. If, following a 2-year period beginning on the date of the imposition of such requirements, the company still has failed to adequately remediate that deficiency, the agencies, in consultation with the Financial Stability Oversight Council, may jointly require the firm to divest certain assets or operations necessary to facilitate orderly resolution under the Bankruptcy Code.

[36]We judgmentally selected four biennial filers and six triennial full filers, because their plans had the most identified weaknesses for plans filed from 2013 through 2023.

[37]As of their most recent plan submissions, there were eight biennial filers (all U.S. GSIBs), 16 triennial full filers (including 11 foreign GSIBs), and 55 triennial reduced plan filers (including 10 foreign GSIBs). Except in their feedback letters covering plans submitted in 2013 and 2014, the agencies specifically identified which findings were deficiencies or shortcomings. In the feedback letters covering plans submitted in 2013 and 2014, the agencies included “shortcoming” sections that discussed aspects of the plans but did not specifically label them as shortcomings. If the feedback letter described an aspect of the plan as a weakness, we counted it as a shortcoming. Similarly, if the letter specifically cited the reviewed plan when discussing the need for additional information or more stringent assumptions, we counted the finding as a shortcoming, because the agencies’ press release highlighted such findings as shortcomings.

[38]The Federal Reserve and FDIC’s 2019 resolution plan rule divides companies into three groups of filers: (1) biennial filers, (2) triennial full filers, and (3) triennial reduced filers. Prior to the 2019 resolution plan rule, the agencies required companies to file plans annually on a staggered schedule and were assigned to four groups, referred to as waves. The first and second waves generally included U.S. and foreign GSIBs. For our analysis, we used the three post-2019 categories to classify plan weaknesses, although some companies changed categories over time or are no longer required to file resolution plans.

[39]In our review of the agencies’ feedback letters covering plans submitted in 2015 and later, we found two deficiencies that were not addressed by the deadline set by the agencies. Both deficiencies have since been remediated. We also identified one shortcoming by another filer that was not fully addressed by the time of the subsequent submission. As of April 28, 2025, this shortcoming remained open and is subject to an extended remediation timeline. In their feedback letters covering plans submitted before 2015, the agencies did not explicitly state whether shortcomings or deficiencies identified in the prior submission had been addressed adequately.

[40]We categorized each identified deficiency and shortcoming according to the vulnerabilities described in the 2019 resolution plan guidance for biennial filers. See Final Guidance for the 2019 [sic], 84 Fed. Reg. 1,438 (Feb. 4, 2019).

[41]Each vulnerability is described in detail in agency guidance. See Final Guidance for the 2019 [sic], 84 Fed. Reg. 1,438 (Feb. 4, 2019).

[42]According to Federal Reserve officials, the Federal Reserve rule on total loss-absorbing capacity, long-term debt, and clean holding company requirements for GSIBs has helped mitigate resolution challenges related to capital. Total Loss-Absorbing Capacity, Long-Term Debt, and Clean Holding Company Requirements for Systemically Important U.S. Bank Holding Companies and Intermediate Holding Companies of Systemically Important Foreign Banking Organizations, 82 Fed. Reg. 8,266 (Jan. 24, 2017).

[43]GAO, Macroprudential Oversight: Principles for Evaluating Policies to Assess and Mitigate Risks to Financial System Stability, GAO‑21‑230SP (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 28, 2021).