SEXUAL HARASSMENT

Actions Needed to Ensure Consistent Agency Policies for Research Institutions

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional committees.

For more information, contact: Candice N. Wright at WrightC@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

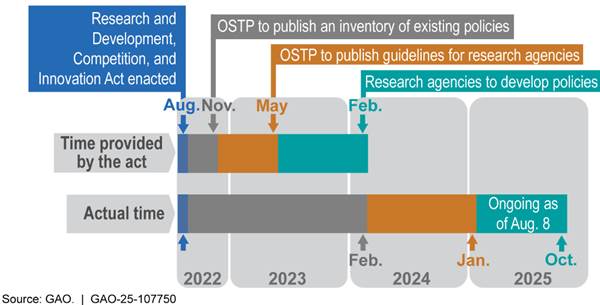

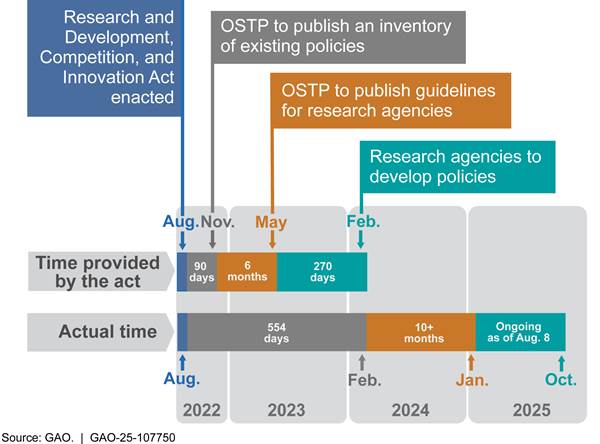

The Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) did not complete actions to address sexual harassment at federally funded research institutions within the Research and Development, Competition, and Innovation Act’s time frames. For example, OSTP was 15 months late in publishing its February 2024 required inventory of research agencies’ sexual harassment policies. This led to cascading delays in issuing required policy guidelines for agencies—January 2025 guidance was issued 20 months later than it should have been.

GAO’s review of 17 research agencies found that none had policies that were fully consistent with the OSTP guidelines issued in January 2025. These agencies are now evaluating how to align their policies with the guidelines and expressed concern about meeting the current October 2025 deadline.

OSTP is to monitor agencies’ development of policies. Such monitoring can ensure research agencies implement consistent policies, a goal specified in the act. However, OSTP does not have staff in place to lead this effort. OSTP officials stated they are recruiting to fill such positions, but the office had not yet hired staff as of July 2025, raising doubts about meeting the October deadline.

Consistent with the act’s requirements, in August 2023 the National Science Foundation (NSF) announced its intention to make awards to study sexual harassment. In analyzing NSF’s awards database, GAO identified four such awards. However, these four awards were terminated as of May 2025.

OSTP’s guidelines addressed most of the act’s requirements, but did not fully address sharing of harassment reports and reporting of investigative information. OSTP staff involved in developing the guidelines departed shortly after its release, which coincided with a change in administrations. Addressing these requirements can enhance research agencies’ awareness of recurring issues, a problem specified in the act.

Why GAO Did This Study

Academic science, engineering, and medicine are particularly susceptible to workplace sexual harassment, according to the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Amid these concerns, the Research and Development, Competition, and Innovation Act, enacted in 2022, identified various requirements for federal research agencies, OSTP, and NSF to combat sexual harassment at federally funded research institutions and increase consistency in research agencies’ policies. The act includes a provision for GAO to assess federal efforts to implement policies that address sexual harassment at research institutions. This report addresses: (1) the status of actions required of OSTP, NSF, and research agencies and (2) the extent to which the policy guidelines address the act’s requirements.

GAO analyzed documentation and written responses from OSTP and 17 research agencies, including NSF, on their existing sexual harassment policies and the extent to which they were consistent with the January 2025 OSTP guidelines. GAO also compared these guidelines to the act’s requirements. In addition, GAO interviewed OSTP officials.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making two recommendations to OSTP to (1) monitor agencies’ development of policies and (2) fully address sharing of reports and investigative information in its policy guidelines. OSTP responded that it did not have comments on the report.

Abbreviations

|

AOR |

Authorized Organizational Representative |

|

CHIPS |

Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semi- |

|

DOE |

Department of Energy |

|

EEOC |

U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission |

|

FAQs |

Frequently Asked Questions |

|

FERPA |

Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act |

|

HR |

Human Resources |

|

IWG-SISE |

Interagency Working Group on Safe and Inclusive |

|

NIH |

National Institutes of Health |

|

NSF |

National Science Foundation |

|

OCR |

Office for/of Civil Rights |

|

OSTP |

Office of Science and Technology Policy |

|

PI |

Principal Investigator |

|

STEM |

Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

September 30, 2025

The Honorable Ted Cruz

Chairman

The Honorable Maria Cantwell

Ranking Member

Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation

United States Senate

The Honorable Brian Babin

Chairman

The Honorable Zoe Lofgren

Ranking Member

Committee on Science, Space, and Technology

House of Representatives

Each year, federal agencies provide funding to institutions, such as universities, to conduct research and development in critical science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields. In 2022, federal agencies obligated over $100 billion for research and development to such institutions.[1] Members of Congress and others have raised concerns about sex-based or sexual harassment (which we refer to as sexual harassment) at institutions that receive federal research awards.[2] The fields of academic science, engineering, and medicine are particularly susceptible to workplace sexual harassment, according to a 2018 study by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.[3] The National Academies determined that this higher susceptibility is due to characteristics such as gender imbalances, organizational tolerance for harassing behavior, hierarchical relationships, and isolating environments. According to the National Academies, the prevalence of sexual harassment in STEM workplaces harms the workforce. We previously reported that federal science agencies lacked goals and an overall plan to assess progress in preventing sexual harassment, and we found that establishing such goals—along with regular monitoring and evaluation of policies and communication mechanisms—would better position agencies to coordinate and strengthen their efforts.[4] Federal research agencies generally maintain policies for reporting and responding to incidents of sexual harassment that apply to agency employees, but questions remain about those agencies’ ability to adequately monitor and address harassment involving award recipients at research institutions.[5]

The Research and Development, Competition, and Innovation Act, enacted in August 2022 as part of what is commonly known as the CHIPS and Science Act, directs the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) and the National Science Foundation (NSF) to take steps to reduce the prevalence of sexual harassment at institutions receiving federal research awards.[6] Specifically, the act directs OSTP to establish an interagency working group to develop an inventory of current agency policies on sexual harassment involving award recipients. In addition, the act requires OSTP to work with research agencies and other federal stakeholders to develop policy guidelines to address sexual harassment at the institutions that receive research awards. The act also requires NSF to enter into agreements with the National Academies to research and report on sexual harassment in the STEM workforce.

The Research and Development, Competition, and Innovation Act also includes a provision for us to review the extent to which research agencies have implemented the policy guidelines. This report addresses (1) the status of activities the act requires of OSTP, NSF, and the research agencies, and (2) the extent to which the policy guidelines address the act’s requirements.

For the first objective, we reviewed documentation such as announcements of agency actions and written responses from OSTP and NSF related to their responsibilities established in the act. We also interviewed officials from both agencies about their responsibilities under the act.

To analyze the differences between the policy guidelines—published on January 6, 2025—and the research agencies’ existing policies, we reviewed the February 14, 2024, inventory of agencies’ sexual harassment policies to obtain a baseline set of policies. We then contacted all 22 agencies included in that inventory to obtain any new or revised policies on sexual harassment issued between publication of the February 14, 2024, inventory and the January 6, 2025, guidelines. Next, we used data from NSF’s National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics to determine whether each of the 22 agencies met the act’s definition of a federal research agency. Based on this analysis, we excluded five agencies from our analysis that did not meet the definition. Of the remaining 17 agencies, five did not have any policies at the time the guidelines were published. We analyzed each agency’s policies to determine whether they applied to recipients of federal research awards and whether they were consistent with the guidelines’ recommendations. Using a standardized coding framework, a GAO analyst assessed whether each policy was consistent, partially consistent, or not consistent with each guideline recommendation. A second analyst independently reviewed each policy to confirm the coding. In cases of disagreement that could not be resolved between the first two analysts, a third analyst would make the final determination. In addition, we obtained written responses from the agencies about their current efforts to develop or revise policies consistent with the guidelines.

For the second objective, we compared the guidelines to the act’s nine requirements and seven considerations for the guidelines.[7] A GAO analyst reviewed each statutory requirement and examined the guidelines for corresponding language. In consultation with GAO legal experts, the analyst identified any discrepancies and determined whether each requirement was (1) consistent, (2) partially consistent, or (3) not consistent with the guidelines.

We conducted this performance audit from August 2024 to September 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Sexual Harassment in Academic STEM Fields

According to the National Academies, progress in closing the gender gap in science, engineering, and medicine is jeopardized by the persistence of sexual harassment and its adverse impact on women’s careers in colleges and universities. Sexual harassment undermines women’s professional and educational attainment and mental and physical health. When women experience sexual harassment in the workplace, the professional outcomes include declines in job satisfaction; withdrawal from their organization (i.e., distancing themselves from the work either physically or mentally without actually quitting, having thoughts or intentions of leaving their job, and actually leaving their job); declines in organizational commitment (i.e., feeling disillusioned or angry with the organization); increases in job stress; and declines in productivity or performance. Decades of research demonstrate how quality and innovation in business and science benefit from having a diverse workforce. The cumulative effect of sexual harassment is a significant and costly loss of talent in academic science, engineering, and medicine, which has consequences for advancing the nation’s economic and social well-being and its overall public health, as the National Academies have reported.[8]

OSTP and Research Agency Requirements

The act requires OSTP to work through the National Science and Technology Council to establish an interagency working group to coordinate research agencies’ efforts to reduce the prevalence of sexual harassment involving award personnel.[9] The term ‘‘award personnel’’ refers to the principal investigators and co-principal investigators, faculty, postdoctoral researchers, and other employees supported by a grant, cooperative agreement, or contract under federal law.[10] The act requires the working group to coordinate with an existing working group and a subcommittee and to consult with: (1) a representative from each federal research agency, (2) the civil rights offices of the Departments of Health and Human Services and Education, and (3) the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. The act requires the working group (1) to develop an inventory of existing policies within 90 days of enactment—by November 2022, and (2) to develop policy guidelines within 6 months of the inventory, by May 2023. The act mandates OSTP to ensure that the policy guidelines developed by the working group include nine requirements. The act also mandates that OSTP contemplate requiring or incentivizing seven considerations (see table 1, below).

Table 1: Requirements and Considerations for Policy Guidelines to Reduce Sexual Harassment at Research Institutions Included in the Act

|

Requirements · The guidelines should require, to the extent practicable, recipients of federal research awards to submit reports to the funding federal research agency or agencies about: · any decision to launch a formal investigation of sexual harassment by or of award personnel · any administrative actions related to an allegation against award personnel of any sexual harassment that affects the ability of award personnel or their trainees to carry out the award’s activities · the total number of investigations with no findings of misconduct including sexual harassment · findings of sexual harassment by, or of, award personnel, including the final findings, appeals, court proceedings, or any disciplinary action taken. · The guidelines should require, to the extent practicable, federal research agencies to share, update, and archive reports of sexual harassment from recipients with relevant research agencies annually and by agency request. · The guidelines should require, to the extent practicable, research agencies to be consistent with regard to the policies and procedures for receiving reports of sexual harassment from award recipients. · The guidelines should be consistent with the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act of 1974. · The guidelines should not infringe upon the privacy rights of individuals associated with reports submitted to research agencies. · The guidelines should not require recipients to provide interim reports to federal agencies. Considerations · The Office of Science and Technology Policy should consider using the guidelines to require or incentivize: · Recipients to periodically assess their organizational climate, which may include the use of climate surveys, focus groups, or exit interviews. · Recipients to publish online the results of climate assessments conducted, disaggregated by sex and, if possible, by race, ethnicity, disability status, and sexual orientation, without including personally identifiable information. · Recipients to annually publish the number of reports of sexual harassment at that institution or organization. · Recipients to regularly assess and improve policies, procedures, and interventions to reduce the prevalence of sexual harassment and to improve the reporting of it. · Each entity applying for a research and development award to certify that a code of conduct is in place and online for maintaining a healthy and welcoming workplace for award personnel. · Each recipient and federal research agency to have mechanisms for addressing the needs of individuals who have experienced sexual harassment, including those individuals seeking to reintegrate at the recipient entity. · Recipients to work to create a climate intolerant of sexual harassment and that values and promotes diversity and inclusion. |

Source: GAO summary of section 10536 of the Research and Development, Competition, and Innovation Act. | GAO‑25‑107750

The act also assigns OSTP three ongoing responsibilities:

1. Encourage and monitor the research agencies’ efforts to develop or maintain and implement policies consistent with the guidelines.

2. Report on the research agencies’ implementation of the policy guidelines 1 year after the release of the policy inventory and every 5 years thereafter.

3. Update the policy guidelines as needed.

Within 270 days of the guidelines’ publication, research agencies are to develop and maintain policies that are consistent with the policy guidelines. Research agency policies must protect the privacy of all parties involved in any reports or investigations to the maximum extent practicable and the research agencies must broadly disseminate sexual harassment policies to current and potential award recipients.

NSF Requirements

The act has three requirements for NSF in its sections on combating sexual harassment. First, within 180 days after enactment, NSF must enter into an agreement with the National Academies to update their report from 2009, entitled On Being a Scientist: A Guide to Responsible Conduct in Research. The report is due no later than 18 months after the effective date of the agreement and must address updated professional standards of conduct in research; promising practices to prevent, address, and mitigate the effects of sexual harassment—including standards of treatment, bystander intervention, and professional standards for mentorship and teaching; and promising practices for mitigation potential risks that threaten research security. Second, within 3 years after enactment, NSF must undertake a new study and issue a report on the influence of sexual harassment in higher education on career advancement of individuals in the STEM workforce. Third, NSF must make awards available to research institutions to study sexual harassment in the STEM workforce (see table 2, below). The act did not include deadlines for NSF to make those awards.

|

Make awards to external research institutions to: · Expand research efforts to better understand the factors contributing to and consequences of sexual harassment affecting individuals in the STEM workforce, including students and trainees; and · Examine approaches to reduce the incidence and negative consequences of sexual harassment. Activities funded may include: · Research on the sexual harassment experiences of individuals, including in racial and ethnic minority groups, disabled individuals, foreign nationals, and sexual-minority individuals; · Development and assessment of policies, procedures, trainings, and interventions, with respect to sexual harassment, conflict management, and ways to foster respectful and inclusive climates; · Research on approaches for remediating the negative effects and outcomes of sexual harassment on individuals; · Support for institutions of higher education or nonprofit organizations to develop, adapt, implement, and assess the effect of innovative, evidence-based strategies, policies, and approaches to prevent and address sexual harassment; · Research on alternatives to the power dynamics, and hierarchical, and dependent relationships, including the mentor-mentee relationship, in academia that have been shown to create higher levels of risk for and lower levels of reporting of sexual harassment; and · Establishing a center for the ongoing compilation, management, and analysis of organizational climate survey data. |

Source: GAO summary of section 10534 of the Research and Development, Competition, and Innovation Act. | GAO‑25‑107750

OSTP and NSF Efforts to Address Sexual Harassment at Research Institutions Started Late

OSTP began its efforts to meet the act’s requirements to address sexual harassment at research institutions but not within the time frames established in the act, thereby delaying research agency implementation of new sexual harassment policies. NSF entered into an agreement with the National Academies to update one of two required reports and made awards to research institutions related to the prevention of sexual harassment that were later terminated.

OSTP Took More Time than Directed Thereby Delaying Research Agency Implementation of New Sexual Harassment Policies

OSTP has taken most of the actions required by the act, but these actions were delayed. According to OSTP officials we spoke with in October 2024, there were many competing priorities in the act that prevented them from completing statutorily required activities. First, OSTP was late in forming the new working group required by the act.[11] More specifically, OSTP formed the working group to engage federal agencies in July 2023, approximately 8 months after the working group’s first responsibility from the act was due. Further, the working group did not conduct its first meeting until November 2023. The working group, known as the Interagency Working Group on Safe and Inclusive STEM Environments, was composed of representatives from 25 federal agencies, including the civil rights offices of the Departments of Health and Human Services and Education, and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

On February 14, 2024, the working group released an inventory of existing research agency policies. This was 554 days after enactment of the law, rather than the 90 days directed in the act.[12] On January 6, 2025, the working group published the policy guidelines. This was about 10 months after release of the inventory rather than the 6 months directed in the act (see fig. 1 below).[13]

The act also required OSTP to report on agencies’ implementation of the guidelines within 1 year of the inventory’s release and every 5 years thereafter and update such policy guidelines as needed. On January 9, 2025, OSTP announced publication of the guidelines in an existing report series, but at that point the only notable development was the guidelines’ publication.[14]

According to the deadlines established in the act, agencies would have completed their efforts to implement polices consistent with the guidelines by February 2024. As a result of the delays in publishing the inventory of existing policies and publishing the policy guidelines, research agencies are only now in the 270-day period—ending October 3, 2025—provided by the act for developing policies consistent with the guidelines.

Because that deadline had not yet passed at the time of our review, we could not review agencies’ implementation efforts. Instead, we assessed the extent to which agencies’ policies were already consistent with the guidelines at the time they were published in January 2025. We found that the 17 research agencies included in the inventory will have to develop policies to become consistent with the guidelines. For details on our analysis, see appendix I.

While the time frame for the research agencies to develop and implement policies consistent with the guidelines is ongoing, research agency officials cited a variety of reasons for not expecting to meet the act’s time frame for implementation. These reasons included reduced staffing and agency restructuring activities. Agency officials told us that they were considering developing policies based on the guidelines but had not completed them as of July 2025 and few officials expected them to be complete by the October 2025 deadline.

On an ongoing basis, the act requires OSTP to encourage and monitor research agencies’ implementation of policies consistent with the guidelines and update the guidelines as needed. The previous administration published the policy guidelines on January 6, 2025, and OSTP’s leadership and staff changed soon after. OSTP has not assigned staff to encourage and monitor implementation nor has it reconvened the working group. Research agencies are developing policies for implementation without an active working group or OSTP’s encouragement and monitoring, which may result in inconsistent policies.

In July 2025, OSTP told us they were recruiting subject matter experts across numerous policy areas including on sexual harassment. As OSTP assigns staff and recruits experts, performing the monitoring role outlined for it in the act could help the research agencies implement consistent policies, a goal specified in the act, and later to update the policy guidelines as needed.

NSF Funded One of Two Required National Academies Reports and Made Awards that Were Later Terminated

NSF was required, within 180 days of enactment of the act, to contract with the National Academies to update a 2009 report On Being a Scientist.[15] We found that NSF did so about 19 months later than the act’s deadline.[16] NSF officials told us they delayed contracting with the National Academies until appropriations were available. The National Academies project—On Being a Scientist: An Updated and Online Guide to the Responsible and Ethical Conduct of Research—is in progress as of September 2025. According to the National Academies, the update will reflect significant developments and changes in the practice of research, including increased scrutiny of international collaboration and research security practices, and emerging technologies like artificial intelligence. The National Academies noted that the resource is widely used in graduate-level courses on the responsible conduct of research and often serves as the first formal introduction to professional standards of conduct for early-career scientists.

NSF also was required, within 3 years of enactment of the act, to contract with the National Academies to initiate a new study and issue a report on the influence of sexual harassment in institutions of higher education on the career advancement of individuals in the STEM workforce. NSF officials told us in February 2025 that they were in conversation with the National Academies to produce the report on the influence of sexual harassment on career advancement. However, in July 2025, NSF officials told us they had not entered into an agreement for the new study due to funding constraints. The August 2025 deadline for the study and report has now passed without an award to the National Academies for the work.

The act also required NSF to make awards available to research institutions to study sexual harassment, and NSF published a “dear colleague letter” in August 2023 to announce the agency’s interest in making awards to study the prevalence and effects of sexual harassment in the STEM workforce.[17] This action signaled NSF’s intent to fund research consistent with the act’s requirements that it make awards to conduct research to accomplish two goals: (1) to better understand the factors contributing to and consequences of sexual harassment affecting individuals in the STEM workforce, including students and trainees; and (2) to examine approaches to reduce the incidence and negative consequences of such harassment (see table 2, above).

Due to limitations in NSF’s award database, it is not possible to link an award directly to a specific dear colleague letter. Nonetheless, NSF identified 43 awards and one proposal for award as potentially having been proposed in response to their dear colleague letter. We therefore reviewed the abstracts for these awards and the proposal and found that four of the awards were consistent with the act’s requirements for activities to be funded. However, these four awards, along with 21 others, were terminated by May 2025, and the proposal for award was never awarded, according to NSF officials in July 2025.

OSTP Guidelines Include Language that Addresses Most but Not All Requirements

The OSTP policy guidelines included 62 recommendations for the research agencies to address as they develop their policies to meet the act’s October 2025 deadline. We found that the guidelines address federal privacy protections and do not require interim reports, consistent with the act’s requirements. They also include language that addresses most requirements related to coordinating and standardizing efforts. However, the guidelines do not explicitly state that the reporting requirements extend to investigations and only partially address the act’s requirement for agencies to share, update, and archive reports of harassment.

OSTP Guidelines Address Federal Privacy Protections

We compared the OSTP guidelines to the act’s nine requirements and assessed whether they included language that addressed those requirements (see table 3, below).

Table 3: Comparison of Research and Development, Competition, and Innovation Act’s Requirements and Office of Science and Technology Policy Guidelines

|

Requirement |

GAO assessment |

|

Recipients are required to report any decision to launch a formal investigation of sexual harassment by or of award personnel |

Not explicitly addressed |

|

Recipients are required to report on any administrative actions related to an allegation against award personnel of any sexual harassment that affects the ability of award personnel or their trainees to carry out the award’s activities |

Included |

|

Recipients are required to report the total number of investigations with no findings of misconduct including sexual harassment |

Not explicitly addressed |

|

Recipients are required to report findings or determinations of sexual harassment by or of award personnel |

Included |

|

Federal research agencies are required to share, update, and archive reports of sexual harassment from recipients with relevant research agencies annually and by agency request |

Partially addresseda |

|

Research agencies are required to be consistent with regard to the policies and procedures for receiving reports of sexual harassment from award recipients |

Included |

|

Guidelines are consistent with the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act of 1974 |

Included |

|

Guidelines do not infringe upon the privacy rights of individuals associated with reports submitted to research agencies |

Included |

|

Guidelines do not require recipients to provide interim reports to federal agencies |

Included |

Source: GAO. | GAO‑25‑107750

aThe guidelines addressed archiving reports but no other aspect of this requirement.

The act requires the guidelines developed by OSTP’s working group to be consistent with the requirements of Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), which protects students’ personal information held by academic institutions. Guideline Recommendation 2a.1 included language clarifying that any descriptions of harassment submitted to research agencies are to be consistent with the requirements of FERPA.[18] Second, the act requires that mandatory harassment reports submitted by award recipients to research agencies not infringe on the privacy rights of the individuals involved. Guideline Recommendation 2a.1 also includes language specifying that mandatory harassment reports do not disclose any personally identifiable information of those involved, in addition to the protections established through its consistency with FERPA. Finally, the act requires that the guidelines not require interim reports related to incidents of sexual harassment. Our analysis found that the guidelines do not include any such reporting requirement.

OSTP Guidelines Include Language that Addresses Most Requirements to Coordinate and Standardize Agency Efforts

The OSTP guidelines include language to address the act’s requirement for agencies to establish consistent policies for processing reports of sexual harassment but only partially addressed the requirement to coordinate with other agencies in sharing, updating, and archiving such reports. Specifically, the act requires, to the extent practicable, that the guidelines establish consistent policies and procedures among research agencies for receiving mandatory reports of harassment-related incidents from award institutions. The guidelines include language to address this requirement by making 13 recommendations for improving the consistency of policies and procedures for reporting sexual harassment (see app. I). These recommendations aim to establish consistent policies and procedures for three different reporting pathways: (1) mandatory notifications by awardee institutions, (2) voluntary reporting options for award personnel or other individuals, and (3) voluntary sharing of information related to harassment that does not constitute a complaint for award personnel or other individuals. These recommendations include the following:

· Guideline Recommendation 2a.1 establishes consistent standards for what information award institutions are to include in mandatory harassment reports to research agencies.

· Guideline Recommendation 2b.4 establishes a standard for research agencies to have an online reporting system in place through which individuals can submit harassment complaints about award personnel.

· Guideline Recommendation 2c.1 establishes a standard for research agencies to have a procedure in place for individuals to confidentially report information related to harassment without making a formal complaint.

The guidelines also recommend that research agencies archive the reports they receive from recipient research institutions, addressing part of the act’s requirement for the guidelines to promote the sharing, updating, and archiving of mandatory sexual harassment reports with other research agencies.

However, the guidelines did not include a recommendation that research agencies update these reports or share them with other agencies. Instead, the guidelines identify a centralized interagency reporting and information sharing mechanism as an area for further exploration by the research agencies. In its coordinating role, OSTP has not convened the working group since the guidelines were released and has not taken further action to examine centralized reporting and information sharing mechanisms. OSTP cited staffing shortages from when the administration changed as a reason for not taking further action since the guidelines were released in January 2025. As OSTP identifies staff, determining how it will continue work to fully implement the act’s requirement to identify a mechanism for updating and sharing information would ensure research agencies have critical information about recurring issues, such as researchers’ past misconduct, when making award decisions. Specifically, this information would help research agencies minimize the potential for offenders to continue receiving federal support.

OSTP Guidelines Do Not Explicitly Address All Requirements Related to Incident Reporting

The guidelines include language that addresses the act’s requirements for recipients to report any findings or determinations of harassment involving award personnel and any administrative actions related to an allegation of harassment against award personnel. Our analysis found that Guideline Recommendation 2a.1 includes both of those reporting requirements by establishing mandatory reporting if any principal investigator or co-principal investigator is subject to a finding or determination of harassment, or an administrative action related to harassment. The act’s language does not limit mandatory reporting to harassment involving principal investigators or co-principal investigators, but we found that the guidelines address this discrepancy by including a recommendation for agencies to consider expanding these reporting requirements to include other award personnel.

The guidelines’ language does not explicitly address the act’s requirement for recipients to report on any decision to launch a formal investigation of sexual harassment and the number of investigations with no findings of misconduct. Specifically, the guidelines do not elaborate on whether administrative or disciplinary actions include or do not include investigations, which creates ambiguity. While FERPA, a related law, includes investigations in its definition of a disciplinary action, we observed differences in agency policies. For example, in policies we reviewed, the National Institutes of Health distinguishes between disciplinary actions and investigations, and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration defines administrative actions without referencing investigations. An administrative action could include removal from a research project. We were not able to confirm with OSTP how broadly they intended the language on administrative and disciplinary actions to be interpreted because staff working on this issue area departed OSTP in January 2025 when the administration changed, and the new administration was actively recruiting subject matter experts across numerous policy areas, including on sexual harassment, as of July 2025.

If OSTP decides to continue work on the guidelines, clarifying the requirement to report investigations and continuing to work on the requirement for agencies to share reports would assist the research agencies in accurately monitoring sexual harassment and in assessing investigative efforts at research institutions. Taking steps to explicitly reference investigations could provide clarity for all and ensure consistency in research agencies’ understanding and implementation, thus achieving the act’s goal of consistency across agencies.

OSTP Guidelines Include Language that Address Some but Not All Considerations

In addition to the requirements discussed above, the act specified seven considerations for OSTP. The guidelines were not required to include these considerations, but our analysis found that they explicitly included three of the considerations and partially addressed another. OSTP’s guidelines include considerations related to:

· recipients conducting periodic reviews of their organizational climate,

· recipients having mechanisms in place to address the needs of individuals who have experienced sexual harassment, and

· recipients working to create a climate intolerant of sexual harassment.

The guidelines partially addressed a consideration to have award applicants certify that a code of conduct for maintaining a healthy and welcoming workplace is in place and published on their website. More specifically, Guideline Recommendation 5a.2 calls for recipients to have such a code of conduct in place, but only for off-site research environments such as field sites and conferences; however, it does not require the code to be published on the recipients’ website.

We found that the guidelines did not explicitly include language that addressed the three other considerations. However, we could not determine whether the working group considered but did not include these items in the guidelines, because staff who developed them and have the requisite knowledge departed in January 2025 when the administration changed. Those three considerations related to:

· recipients publishing results of organizational climate assessments,

· recipients publishing the number of internal reports of harassment, and

· recipients regularly assessing and improving policies, procedures, and interventions meant to address sexual harassment.

Conclusions

Sexual harassment in federally funded research environments threatens the safety and productivity of the U.S. STEM workforce. While OSTP and NSF have taken steps to implement statutory requirements under the act, missed deadlines and incomplete implementation hinder the government’s efforts to reduce the prevalence of harassment involving award personnel.

Without OSTP assigning staff, monitoring agency progress, or reconvening the working group, the research agencies may not implement the guidelines consistently. Further, research agencies may not take timely and coordinated action, undermining congressional intent and limiting the impact of the guidelines.

OSTP’s interagency working group issued policy guidelines that provide a useful foundation, but the guidelines omit or lack clarity on key elements required by law—most notably, the need for recipients to report initiated investigations and for agencies to share harassment reports. Without these mechanisms, research agencies may lack critical information about past misconduct when making award decisions, potentially enabling offenders to continue receiving federal support.

Implementing the full set of statutory requirements, including improving data collection and coordinating among agencies, is essential to ensure accountability and prevent future harm.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following two recommendations to OSTP:

The Director of OSTP should fulfill its statutory role to encourage and monitor the research agencies’ development, implementation, and maintenance of policies consistent with federal guidelines to reduce sexual harassment involving award personnel. (Recommendation 1)

The Director of OSTP should revise federal guidelines to fully address the sharing among agencies of harassment reports about individuals working on federal research awards and indicate that research agencies should be collecting data on initiated sexual harassment investigations involving award personnel and the results of all such investigations. (Recommendation 2)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of our report to the Environmental Protection Agency, the National Institutes of Health, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, NSF, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, the National Institute of Standards and Technology, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, OSTP, the Smithsonian Institution, the U.S. Agency for International Development, the U.S. Geological Survey, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, and the Departments of Agriculture, Defense, Education, Energy, the Interior, Health and Human Services, Homeland Security, State, Justice, Transportation, and Veterans Affairs.

The Environmental Protection Agency, the National Institutes of Health, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, NSF, the National Institute of Standards and Technology, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, OSTP, the Smithsonian Institution, the U.S. Agency of International Development, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, and the Departments of Education, Energy, Health and Human Services, Homeland Security, State, Justice, Transportation, and Veterans Affairs responded that they did not have comments on our report. The Department of Agriculture did not respond to our request for comments. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission, the U.S. Geological Survey, and the Departments of Defense and the Interior provided technical comments which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Director of the Office of Science and Technology Policy, the heads of the federal research agencies, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact Candice N. Wright at wrightc@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix II.

Candice N. Wright

Director

Science, Technology Assessment, and Analytics

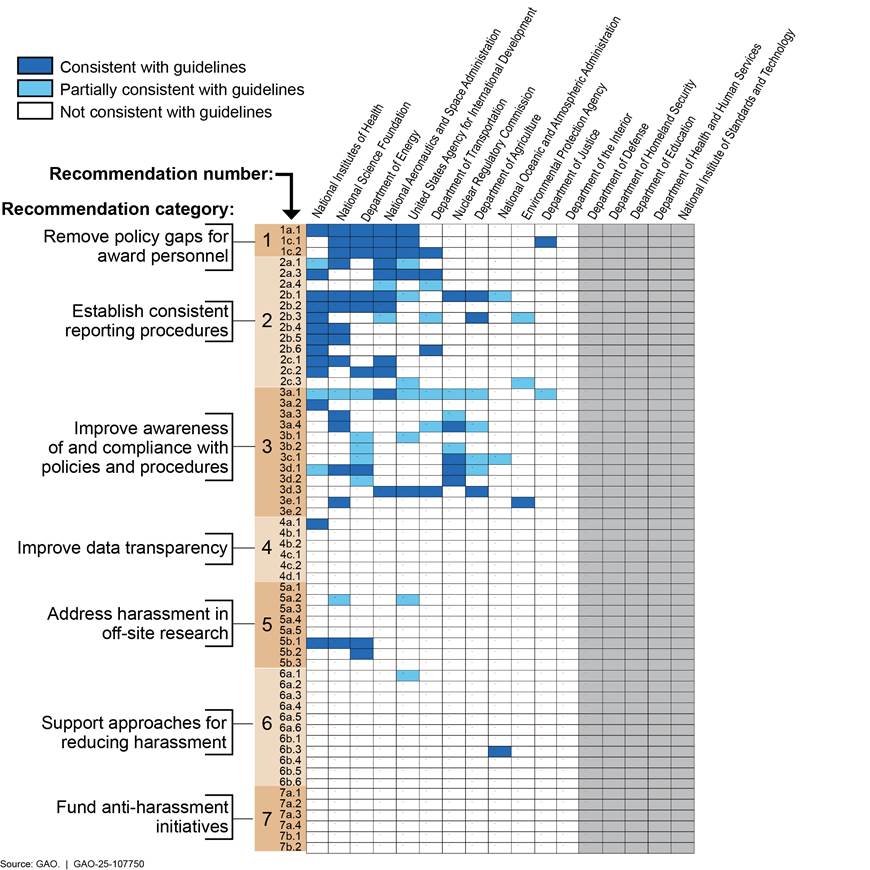

We analyzed the policies, procedures, and resources (policies) for addressing sexual harassment involving award personnel that the agencies had in place as of January 2025, when OSTP and its working group published guidelines to address sexual harassment at the institutions that receive research awards, by comparing those policies to the 62 recommendations included in the guidelines.[19] The guidelines included 62 recommendations, each falling into one of seven categories related to different aspects of harassment prevention and response.

Of the 22 agencies included in the working group’s policy inventory, five did not meet the Research and Development, Competition, and Innovation Act’s definition of a research agency—the Department of State, Smithsonian Institution, U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, U.S. Geological Survey, and Department of Veterans Affairs.[20] Of the remaining 17 agencies, five had no policies at the time the guidelines were published, and 12 had existing policies to analyze.

We found that none of the 12 research agencies with applicable policies had policies that were consistent with all the guidelines’ 62 recommendations when their time frame for developing policies began in January 2025.[21] Five of the 12 research agencies had policies that were partially or fully consistent with some (approximately one-fifth) of the guidelines’ recommendations. These research agencies included the Department of Energy, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, and the United States Agency for International Development (see fig. 1 below). Six of the remaining seven research agencies had policies that were partially or fully consistent with fewer than one-fifth of the recommendations, and one of the remaining seven research agencies did not have policies consistent with any of the recommendations. Overall, no research agency was fully or partially consistent with 26 of the guidelines’ 62 recommendations. For example, no research agency’s policies were consistent with Guideline Recommendation 4b.2 for agencies to review the effectiveness of their sexual harassment and response policies at regular intervals. Table 4, below, provides details of the guidelines’ recommendations.

Figure 2: Research Agency Policies, as of January 2025, Compared with Guidelines to Address Sexual Harassment at Institutions that Receive Research Awards

The extent to which existing agency policies were consistent with the guidelines’ recommendations varied across the seven recommendation categories. The three categories that agencies’ policies were most consistent with included:

1. identifying and removing gaps in policies pertaining to sexual harassment that apply to award personnel (see fig. 1, category 1),

2. improving consistency across procedures for reporting harassment to agencies (see fig. 1, category 2), and

3. ensuring awareness of, and compliance with, agency harassment policies and reporting procedures among federal employees, awardees, award personnel, and trainees (see fig. 1, category 3).

Most agencies will require a significant effort to develop their policies to become consistent with the guidelines’ recommendations before the end of 270-day period provided by the act—October 3, 2025. Specifically, we found that the 17 research agencies that were included in the February 2024 inventory of existing policies will have to develop policies to become consistent with the guidelines.[22] For example, existing policies largely are not consistent with recommendations related to data transparency, off-site research, strategies for preventing harassment, and opportunities to research harassment.

The full text of the guidelines’ 62 recommendations to reduce sexual harassment at research institutions is provided below in table 4.[23]

Table 4: OSTP Guideline Categories and Recommendations to Reduce Sexual Harassment at Research Institutions

|

Guideline Categories |

Guideline Recommendations |

|

1. Identify and remove gaps in policies pertaining to sexual harassment that apply to extramural award personnel |

1a.1: All federal research agencies should institute policies that prohibit sex-based and sexual harassment involving award personnel as a condition of receiving a federal research and development award. 1b.1: Through interagency coordination bodies such as IWG-SISE, with leadership from the Department of Education, Department of Justice, and Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, federal research agencies should collaborate to develop and implement a standard definition of sex-based and sexual harassment in policies that apply to award personnel as a condition of an awardee institution receiving a federal research and development award. 1b.2: The government-wide, standard definition should be adopted by all federal research agencies and should: · Include definitions of sex-based and sexual harassment in policies that apply to award personnel as a condition of an awardee institution receiving a federal research and development award. · Account for all possible forms of sex-based and sexual harassment and include a list of prohibitive behaviors. 1c.1: Federal research agency sex-based and sexual harassment policies should clarify that such protections are not location-based and extend to all on-site and off-site activities sponsored by the federally funded institution or organization. 1c.2: Federal research agency policies that prohibit sex-based and sexual harassment among extramural award personnel should consistently and clearly indicate who is covered under the policy. |

|

2. Improve consistency across procedures for reporting harassment across three pathways: mandatory notifications by awardee institutions; optional reporting by individuals of civil rights violation complaints; and optional reporting to agencies without filing a complaint |

2a.1: All federal research agencies should require awardees—as a term and condition of an award—to report any finding or determination of sex-based and sexual harassment or an administrative or disciplinary action taken against principal investigators or co- investigators to be completed by an AOR at the awardee institution. If possible, agencies should establish an online portal or web form for AORs to submit reports. The term and condition should require, at a minimum, that an AOR disclose the following information to agencies within 10 days of the date the finding/determination is made, or 10 days from when an awardee imposes an administrative action on the reported individual, whichever is sooner. Reports should include: · Award number · Name of PI or Co-PI being reported · Awardee Name · Awardee Address · AOR name, title, phone, and email address · Indication of the report type: · Finding or determination has been made that the reported individual violated awardee policies or codes of conduct, statutes, or regulations relating to sexual harassment, sexual assault, or other forms of harassment, as defined by the agency · Date that the finding/determination was made · Imposition of an administrative or disciplinary action by the awardee on the reported individual related to a finding/determination or an investigation of an alleged violation of awardee policies or codes of conduct, statutes, or regulations related to sexual harassment, sexual assault, or other forms of harassment, as defined by the agency · The date and nature of the administrative/disciplinary action · A basic explanation or description of the event, which should not disclose personally identifiable information regarding any complainants or other individuals involved · Per the CHIPS and Science Act, any description provided must be consistent with the Family Educational Rights in Privacy Act (FERPA) 2a.2: Agencies should assess the impact and feasibility of expanding the mandatory notification requirement to all senior/key personnel and postdocs. Per the definition of award personnel provided in the CHIPS and Science Act, this would expand the mandatory notification requirement beyond PIs and Co-PIs to include other senior/key personnel such as faculty, postdocs, and other employees supported by a research and development federal award. · Agencies should remain mindful that expanding the mandatory notification requirement beyond PIs and Co-PIs will increase administrative burden, both among awardees and agencies. Other senior/key personnel, while named on the budget agreement with the awardee institution, often change throughout the life cycle of the award. Agencies should explore the practicality of expanding this reporting requirement, given the volume of funding awards they administer and the number of award personnel they fund, and consider what additional resources would be necessary for implementation. 2a.3: As part of the mandatory notification policy, agencies should clearly detail how the information provided by awardees will be considered and what the possible agency responses could entail. Agencies should make clear that responsive actions will be appropriate and proportional to the severity of the behavior found to have occurred. · Agencies may consider responsive actions based on the severity of the harassment, including the substitution or removal of the PI or any co-PI, reduction of the award funding amount, or suspension or termination of the award. · Agencies may also consider when to share the information within the interagency context (e.g., when the incident involves a J-1 visa holder which requires the U.S. Department of State’s mandatory incident reporting requirement). 2a.4: Agencies should also indicate where digital records of mandatory notifications will be stored and whether an individual’s personal information profile with an agency will temporarily or permanently reflect the notification report and/or agency action taken. This information should be easy to locate within an agency’s mandatory notification policy. · Agencies should also indicate whether any responsive actions taken will impact the eligibility of the reported individual for future award consideration. 2b.1: All federal research agencies should provide clear and comprehensive instructions for civil rights compliance reporting procedures to award personnel. Agencies should make clear that award personnel and other individuals who have experienced, witnessed, or are aware of sex-based or sexual harassment in a federally funded program can use these procedures to file complaints with the agency. 2b.2: Reporting procedure instructions should also include information about other venues available to complainants for assistance. This action would allow the person to consider their options and make a fully informed choice on how they would like to move forward with their complaint. 2b.3: Instructions for reporting/filing a complaint should clearly describe the full agency investigative process. Details should include at a minimum: how a complaint is filed; who receives the complaint at the agency; how, where, and for how long the information is stored; potential timelines for agency notification, investigation, resolution, and monitoring; the role of the awardee institution in the investigative process; potential options for agency actions for possible report outcomes; retaliation protections; and any agency supports or policies that exist to minimize educational, training, and career disruptions to the complainant, or to support reintegration of the complainant at the awardee institution. These details should be summarized on an agency’s webpages with instructions for reporting, and additional details provided on a separate page/document easily accessible by a complainant. 2b.4: Federal research agencies should establish an electronic reporting system and/or web form to file complaints, in addition to a mailing address and email address. 2b.5: The electronic reporting system or webform should provide an option for complainants to remain anonymous, with the caveat that confidentiality may not be guaranteed during the investigation process and anonymity may limit the scope of the agency’s ability to evaluate and investigate a complaint. 2b.6: When contacting awardee institutions to provide information in support of the complaint, agencies should make expectations clear by providing guidance to awardees with examples of necessary and sufficient information. · Recommendations 2a.2 and 2a.3 should also apply to the investigations that follow a complaint filed by an individual. 2c.1: All federal research agencies should establish a reporting procedure, either via email or web platform, for individuals to share information about instances of harassment involving agency-funded programs and personnel that does not necessitate the filing of a complaint. · This reporting procedure should have an anonymous option. · If complaints are not anonymous, agencies should take all reasonable steps to protect confidentiality. 2c.2: Agency responses to such reports should direct the individual to information about different options (i.e., see Recommendation 2b.2), including how to: file a complaint with the agency and what that process entails, file a complaint with the Department of Education OCR (or other agency civil rights offices), and file a complaint with the awardee institution’s administrative offices. 2c.3: Agencies should make clear what they will do with the information they receive from individuals, where and for how long that information will be stored, and how the information provided in the report may be used for compliance checks, audits, or reviews of awardee institutions. |

|

3. Ensure awareness of, and compliance with, agency harassment policies and reporting procedures among federal employees, awardees, award personnel, and trainees |

3a.1: Federal research agency sex-based and sexual harassment policies and reporting procedures that apply to awardees and award personnel should be clearly labelled, separated from policies that pertain only to federal employees, and easy to locate on an agency’s website. · These policies should be linked on webpages where prospective award personnel can search for funding opportunities. 3a.2: Agencies should create infographics or other visual representations of their complaint review and investigation processes, such as a flowchart, diagram, or infographic (e.g., see the National Institutes of Health (NIH)’s visualizations). · Agencies should also consider posting short, informational videos that provide a succinct overview of available reporting mechanisms. These can be disseminated through social media channels of the agency and its partner organizations (e.g., institutions of higher education; professional societies). 3a.3: As part of agencies’ language access obligations, agencies should offer copies of harassment policy and reporting procedure documents in languages other than English. 3a.4: Agency anti-harassment policy and reporting procedure documents—and the communication of these documents—should comply with agency obligations under Section 504 and Section 508 of the Rehabilitation Act. · Agencies should provide 508-compliant document and website formats and engage in practices that facilitate effective communication with individuals with disabilities. 3b.1: Federal research agencies should require awardees to provide information to all award personnel about federal research agency discrimination/harassment policies and complaint reporting procedures at the onset of the award period: · Agencies should require a notice be given to each person supported by an award that explains what the civil rights laws require, what constitutes discrimination, and where to go to report allegations of harassment. · Agencies may consider including information about alternate reporting mechanisms (i.e., see Recommendation 2b.2). · Compliance with the distribution of information could be periodically reviewed by agencies during audits or compliance reviews. 3b.2: A poster (e.g., U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) or U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) posters) or brochure (e.g., Ship Operations Cooperative Program brochures) containing information provided in the notice proposed in 3b.1 should also be posted/provided in physical (research lab, PI office, graduate student and postdoc office areas, restroom stalls) and virtual places (PI’s research lab website) frequently used by the personnel participating in the award or activity. 3c.1: Federal research agencies should develop training and technical assistance resources regarding harassment policies, civil rights compliance, and agency reporting procedures for awardee staff—including senior leadership (e.g., Provosts and Deans), grants management administrators, Title IX coordinators, Equal Employment Opportunity offices, and/or Human Resources (HR) staff, general counsel—and all award personnel. These trainings should include details on how to report harassment to federal agencies and what the requirements are for harassment investigations to occur. 3d.1: Federal research agencies should determine how to examine awardee compliance with sex-based and sexual harassment policies and reporting procedures that institutions accept as a condition of receiving federal research and development awards. · Agencies should ramp up tools at their disposal (e.g., annual compliance checks, desk audits, culture audits, site visits, etc.) to ensure awardee compliance. 3d.2: Agencies could tailor training and technical assistance offerings, as described in n 3c.1, to improve policy and procedure uptake/adherence among awardee institutions who are found to have issues with compliance. 3d.3: Agencies should outline potential disciplinary measures that will be taken against awardee institutions that are found to be noncompliant with sex-based and sexual harassment policies that institutions accept as a condition of receiving federal research and development awards. 3e.1: Agencies should send an annual internal memo or bulletin (e.g., NSF bulletin) to all employees that includes links to the agency’s harassment policies and reporting procedures for harassment that occurs involving award personnel. · Such a memo/bulletin should include instructions on what the federal employee should do and who they should contact in the event they become aware of a harassment issue in an agency-funded program, project, or institution. · Employees should also be directed to: provide contact information for the agency office that handles complaints of harassment to the person(s) that reported the information, consider all information received as confidential, and only share the information with the appropriate agency officials for reporting purposes and those who have a need to know. 3e.2: Agencies should require that all employees complete an annual training module that provides details on harassment policies and reporting procedures for harassment that occurs involving award personnel; it should remind employees about what to do and who to contract in the event they become aware of harassment in an agency-funded program, project, or institution. |

|

4. Increase data transparency and accountability to support evidence-based policy improvements |

4a.1: All federal research agencies should publicly release statistics on the reports of sexual and other types of harassment/discrimination they have received. Agencies should: · Include information from both mandatory institutional reports and from complaints by individuals. · Consider disaggregating data by institution type or geographic region if it does not jeopardize the anonymity of complainants or affected individuals. · Include information on agency actions taken, not just what was included by the awardee/individual in the report to the funding agency. 4b.1: Federal research agencies should conduct data collection and evaluations to determine which policies, procedures, and agency actions have been effective at changing institutional reporting rates and/or reducing incidence rates of sex-based and sexual harassment involving award personnel. Data collection and evaluations should happen within individual agencies and collectively among agencies, as institutions are funded by multiple agencies, and reduction in harassment at the awardee institutions could be attributed to the actions of more than one agency. Agencies should: · Provide examples of successful use cases. · Release data, evaluations, and case examples to the public. · Conduct analysis with multiple metrics of harassment reduction in mind, including but not limited to: number of individual reports received, number of proactive awardee reports, knowledge of reporting mechanisms by award personnel, and suitability of follow up actions taken by awardee institutions. · Share results of policy effectiveness with other agencies to generate best practices as part of communities of practice, working groups, or other interagency coordination bodies. 4b.2: All federal research agencies should review effectiveness of their sex-based and sexual harassment prevention and response policies that pertain to award personnel in regular intervals (e.g., every 3 to 5 years). These policies should include a brief summary of changes/amendments made since its inception and their effects. 4c.1: Federal research agencies should consider dispersing brief exit surveys to award personnel, including supported trainees, upon the closure of an award. Surveys should include questions about whether PIs fulfilled actions outlined in mentoring plans, whether students, postdocs, or trainees had a positive experience with their training and research experience, and whether they felt they were in an environment free from sex-based and sexual harassment. Given that this information will be requested at the end of the award and/or project, these individuals may feel empowered to honestly share their experiences. · Exit surveys could be part of the award closeout for all types of research training and career development awards (i.e., awards that support trainees, such as graduate research fellowship or postdoctoral research fellowship awards). · The survey results should not be accessible to the PI. · Surveys should direct the respondent to appropriate agency webpages, platforms, and email addresses where respondents can disclose information about harassment, discrimination, and/or bullying that occurred as part of the funded program or award activities (i.e., see Recommendation 2b.2). 4c.2: Agencies responsible for such surveys should consider adding questions to collect information from individuals about if and how sex-based and sexual harassment have impacted their career in STEM. · Agencies should have a plan of what they will do with this information and how they will respond to allegations of harassment or other misconduct. 4d.1: Through additions to their current strategic plans, or in future strategic plans, federal research agencies should consider setting goals, with measurable and trackable benchmarks for success, aimed at reducing sex-based and sexual harassment across federally funded research programs. · Agencies should publicly release such plans and publish annual updates toward progress. |

|

5. Prevent sexual harassment in federally funded off-site locations, including field research sites and conferences |

5a.1: Agencies should provide frequent opportunities for students, postdocs, researchers, and other personnel affiliated with federally funded off-site and field locations to provide feedback on the effectiveness of sex-based and sexual harassment policies and reporting procedures. · If possible, an opportunity for providing anonymous feedback should be included. 5a.2: All federal research agencies that fund off-site research should require awardee institutions to have in place a plan/policy/code of conduct for creating physically safe and psychologically safe environments, establishing clear protocols for project personnel to take should they fear being at risk of harassment (e.g., unfettered access to a phone with GPS capabilities in remote locations), and clear protocols for immediately addressing harassment and other kinds of misconduct before it rises to the level of illegal harassment specifically at that off-site location. At minimum, plans should: · Not conflict with the awardee institutions’ obligations under Title IX and other nondiscrimination statutes. · Include descriptions of how the institution aims to cultivate an inclusive and harassment-free environment and clearly detail processes for reporting, responding to, and resolving incidents, including details on how the awardee institution will direct impacted individuals to necessary resources (such as advocacy resources and medical exams). · Detail what kinds of prevention training (strategic resistance, bystander intervention, and/or workplace culture, etc.) the awardee institution will provide for off-site research participants. · Provide participants in the off-site research activity with information on how to file discrimination and harassment complaints with the funding agency or with other agencies/entities (i.e., see Recommendation 2b.2). · Specifically address online and technology-facilitated harassment and abuse. · Be read and signed by all participants, and awardees should keep a record of this documentation. 5a.3: Federal research agencies should provide technical assistance for prospective awardees to prepare such plans, including FAQ documents, a list of considerations for developing the plan, relevant peer-reviewed research and best practices, recordings of webinars and workshops, blogs, podcasts, and videos. · Agencies should also consider posting examples of promising policies on their websites. 5a.4: If requiring a plan for safe and inclusive off-site research environments, agencies should consider allowing perspective award personnel to request funds for additional staff support or project funding to carry out the stated strategies, goals, and activities of the plan. 5a.5: Agencies could pilot the inclusion of off-site and field site harassment policies, codes of conduct, and other related plans as part of the merit review process, if they have the authority to conduct merit review of proposal components beyond scientific criteria. 5b.1: All federal research agencies that fund conferences, meetings, workshops, and other convenings should require awardee institutions to develop a plan for addressing sex-based and sexual harassment and other kinds of misconduct specifically for that event, including through online and technology-facilitated means. Plans should include descriptions of how the organizers aim to cultivate an inclusive and harassment-free environment and clearly detail processes for reporting, responding to, and resolving incidents. Plans should be read and signed by all participants (including attendees, presenters, and speakers) and organizers should keep a record of this documentation. · Plans should also provide participants with information on how to file discrimination and harassment complaints with the agency (or agencies, in cases where a convening that has support from multiple agencies) that provides funding for the event. · A link to this plan and/or a timeline of plan development should be provided to the agency. 5b.2: Agencies should require conference proposals to describe plans for evaluating efforts to cultivate an inclusive environment post-conference. 5b.3: Federal research agencies should provide technical assistance for prospective awardees to prepare such plans, which may include offering FAQ documents, a list of topics to consider in the development of the plan, and links to relevant peer-reviewed research and best practices. · Agencies should also post examples of promising plans on their websites. |

|

6. Support innovative approaches for reducing harassment in STEM environments including requiring award proposals to include plans for safe, inclusive, and equitable research and instituting policies that address power dynamics in STEM |

6a.1: All federal research agencies should consider piloting requirements for perspective award personnel to submit plans for cultivating safe, inclusive, and equitable research environments. Agencies should clearly outline the information that should be included in such a plan, including metrics which will be used to determine the effectiveness of the proposed plan. Plans should be specific to the research environment, i.e., laboratory, instead of referencing the awardee institution as a whole, and sections of this plan should be devoted to mentorship and career development if students, postdocs, and early career investigators are included in the award. Additionally, PIs should include steps they will take to personally grow and develop as leaders, including how they will ensure knowledge of policies and best practices regarding sex-based and sexual harassment. 6a.2: Federal research agencies should provide technical assistance for prospective awardees to prepare such plans, including FAQ documents, a list of considerations for developing the plan, relevant peer-reviewed research and best practices, recordings of webinars and workshops, blogs, podcasts, and videos. · Agencies should also consider posting examples of promising plans on their websites. 6a.3: If requiring a plan for cultivating safe, inclusive, and equitable research environments, agencies should allow perspective award personnel to request funds for additional staff support or project funding to carry out the stated strategies, goals, and activities of the plan. Cost should be justified in the plan and clearly identified in the proposal budget. 6a.4: Agencies could pilot the review of such plans in a process separate from scientific merit review. 6a.5: Agencies should provide clear guidance on how adherence to these plans will be evaluated, including the expectation for progress to be documented in progress reports and final grant summaries. 6a.6: Within 3 years of piloting these plans, agencies should evaluate the effectiveness of such plans to consider how best to cultivate inclusive environments; support all staff, including award personnel from underrepresented groups; support the professional development of trainees; and/or prevent and reduce discrimination, harassment, and bullying pursuant to applicable law. · Agencies should share results of plan effectiveness with other agencies as part of communities of practice, working groups, or other interagency coordination bodies. Results of plan effectiveness should also be shared with awardees and the public. 6b.1: Agencies should explore mechanisms for decoupling trainee funding from PI funding on a research award, such that if the funding for the PI or project is terminated, trainees would not lose their funding. This may be accomplished through policies that more easily allow trainees to transfer funding to another PI at the awardee institution. 6b.2: Federal research agencies should increase the number of funding opportunities in which graduate students and postdocs themselves receive funding independent of a PI or are otherwise not impeded by changes in funding of faculty members/senior award personnel. In the event of harassment, discrimination, or other abuse and misconduct, agencies should assist with transfer of these awards such that trainees are able to work with another mentor/institution. 6b.3: Federal research agencies should offer administrative supplements to promote reintegration and short-term support for all award personnel who experience harassment, including graduate students, postdocs, and other early career researchers. 6b.4: Agencies should expand/revise existing policies regarding leave within fellowships and other programs to allow for paid leaves of absence, which may be utilized by individuals who have experienced harassment. 6b.5: Federal research agencies that support students and postdocs should encourage the identification of mentoring teams rather than a single advisor and require the creation of mentorship plans and/or mentor-mentee contracts that identify expectations of behaviors and mentoring at the beginning of an award. 6b.6: Federal research agencies should consider mechanisms to reward principal investigators for excellent mentorship, the creation of inclusive STEM environments, and other service activities that contribute to the success of the research environment. |

|

7. Support funding opportunities for awardees to conduct sexual harassment policy research, evaluation, and training |