MILITARY MOVES

DOD Needs Better Information to Effectively Oversee Relocation Program Reforms

Report to the Committee on Armed Services, House of Representatives

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to the Committee on Armed Services, House of Representatives.

For more information, contact: Alissa Czyz at CzyzA@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

The Department of Defense’s (DOD) Transportation Command (TRANSCOM) awarded its Global Household Goods Contract (GHC) in 2021 with the goal of improving both service members’ experiences with military moves and the government’s ability to oversee quality service. TRANSCOM intended to fully transition the household goods shipment and storage aspects of its Defense Personal Property Program to the contract. Various challenges delayed contract implementation initially, but limited GHC shipments began in April 2024. According to TRANSCOM, as GHC shipment volume and geographic coverage increased, the contractor faced limits in its capacity to manage the higher volumes, which resulted in missed or delayed pickups and deliveries. Citing continuous performance challenges, the Secretary of Defense directed the creation of a Permanent Change of Station Joint Task Force in May 2025 to develop recommendations for DOD's strategic path forward for the program. DOD ultimately terminated the GHC in June 2025.

TRANSCOM did not have sufficient, comprehensive information about GHC (1) capacity, (2) performance, and (3) costs to effectively manage risks and oversee contract implementation.

· TRANSCOM officials had identified capacity constraints as a risk to the GHC before implementation, but they had only limited information on the contractor’s capacity and could not verify that information.

· DOD lacked comprehensive feedback on service members’ experiences with the GHC, limiting its assessment of contractor performance. Respondents to GAO’s survey of service members and spouses reported inadequate communication with the contractor’s customer service representatives about the status of their shipments and delays in multiple phases of the moving process.

· TRANSCOM did not have complete information regarding costs associated with the GHC transition; DOD incurred unplanned transition costs, paid management fees for task orders ultimately not carried out by the contractor, and lacked clarity on how GHC costs compared to existing program costs.

By obtaining more comprehensive information on program capacity, performance, and costs, DOD will be better positioned to manage risks and oversee the program effectively as it develops its strategic path forward.

Why GAO Did This Study

DOD arranges for the worldwide movement and storage of about 300,000 personal property shipments of service members and their families each year, at an annual cost of approximately $2 billion. As a result of dissatisfaction with its relocation program, TRANSCOM awarded the GHC, worth up to $17.9 billion over approximately 9 years, to a single commercial move manager in November 2021. However, DOD terminated the contract in June 2025 due to the contractor’s failure to perform services specified in the terms and conditions of the contract.

The House report accompanying a bill for the Servicemember Quality of Life Improvement and National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2025 included a provision for GAO to review DOD’s management and oversight of the GHC. This report (1) describes DOD’s implementation of the GHC and (2) assesses the extent to which DOD had the information needed to effectively oversee contract implementation.

GAO reviewed the GHC and implementation plans, DOD guidance, and acquisition regulations; interviewed DOD officials and performed two site visits; and surveyed service members and spouses on their experiences with GHC moves. GAO met with moving industry and contractor representatives and reviewed capacity, performance, and cost information.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making one recommendation for DOD to obtain comprehensive information on capacity, performance, and costs to effectively oversee DOD’s personal property program and inform future decisions. DOD concurred with this recommendation.

Abbreviations

DOD Department of Defense

DP3 Defense Personal Property Program

GHC Global Household Goods Contract

ToS Tenders of Service

TRANSCOM U.S. Transportation Command

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

September 11, 2025

The Honorable Mike Rogers

Chairman

The Honorable Adam Smith

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

House of Representatives

The Department of Defense (DOD) is the single largest customer in the nation’s personal property moving and storage industry, representing approximately 15 percent of all domestic and international moves. Each year, the U.S. Transportation Command (TRANSCOM), through the Defense Personal Property Program (DP3), arranges for the worldwide movement and storage of approximately 300,000 personal property shipments of service members and their families, at an annual cost of approximately $2 billion, according to TRANSCOM officials.

As a result of widespread dissatisfaction with DOD’s relocation program and calls for change from military families and congressional leaders, TRANSCOM awarded the Global Household Goods Contract (GHC), worth up to $17.9 billion over approximately 9 years, to a single commercial move manager, HomeSafe Alliance, in November 2021.[1] The GHC was intended to improve satisfaction with military moves through better quality, capacity, and customer experience, and TRANSCOM previously reported that savings from the GHC could be as much as $2 billion over 5 years. According to TRANSCOM, cost savings was not a primary goal of the GHC. HomeSafe Alliance was expected to oversee activities related to the worldwide movement and storage-in-transit of household goods for service members and their families. TRANSCOM began implementing the GHC in April 2024. However, citing challenges with GHC performance, the Secretary of Defense in May 2025 established a Permanent Change of Station Joint Task Force to develop a strategic path forward for DOD’s relocation program. Subsequently, on June 18, 2025, DOD terminated the contract, citing the contractor’s failure to perform the services specified in the terms and conditions of the contract.

The House report accompanying a bill for the Servicemember Quality of Life Improvement and National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2025 included a provision for us to review DOD’s management and oversight of the GHC.[2] In our report, we (1) describe DOD’s implementation of the GHC and (2) assess the extent to which DOD had the information needed to effectively oversee contract implementation.

To address both objectives, we reviewed relevant documentation, including GHC documentation, the Federal Acquisition Regulation, DOD guidance related to personal property shipments, and documentation that described plans for GHC implementation. We interviewed TRANSCOM and military service officials responsible for executing and overseeing DP3 and the GHC, including the nine joint personal property shipping offices executing GHC shipments. We conducted site visits at two locations where the GHC was first implemented, which were among those with the largest volumes of GHC shipments. We met with a non-generalizable sample of about 40 moving industry representatives, including the GHC contractor, moving companies, and industry associations, and reviewed documentation on contractor capacity.

We also reviewed GHC performance and cost data. To determine the reliability of the data, we reviewed supporting documentation and interviewed knowledgeable officials. As a result, we determined that the data were sufficiently reliable for reporting general information on GHC performance and costs associated with the program. We also surveyed service members and spouses on their experiences with the GHC, and we received 1,217 responses.[3] This non-generalizable survey primarily asked open-ended questions about the challenges, benefits, and effects on military families of moving under the GHC. We compared DOD’s process for managing and overseeing the GHC to internal control standards and key practices for evidence-based policymaking related to identifying information requirements, determining corrective actions, and leveraging evidence to achieve desired results.

We conducted this performance audit from August 2024 to September 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Overview of DP3

DP3, managed by TRANSCOM, arranges the shipment and storage of household goods for service members and their families.[4] When service members receive transfer orders, they contact their local personal property processing office to receive counseling on their allowances and entitlements. With guidance from these offices, service members enter their transfer and move information into the Defense Personal Property System.[5] As of 2024, over 800 commercial transportation service providers participate in DP3 via Tenders of Service (ToS) to move service members’ personal property, with many either relinquishing control to a move manager or acting as move managers, according to TRANSCOM officials.[6] The military departments own, operate, and staff most of the infrastructure involved in managing and overseeing the timeliness and quality of household goods moves, including personal property shipping and processing offices.[7] These offices work with transportation service providers, move managers, and subcontractors to schedule moves, oversee performance, and, when appropriate, take or recommend punitive action for poor performance. The military services’ lines of accounting pay the commercial transportation service providers, and the military services reimburse TRANSCOM for costs associated with program management, according to TRANSCOM officials.

Overview of GHC

In implementing the GHC, TRANSCOM planned to fully transition the shipment and short-term storage of household goods under DP3, from ToS to the GHC. TRANSCOM’s intended goal was to improve both service members’ experiences with military moves and the department’s ability to oversee and hold transportation service providers accountable for providing quality service. Under the GHC, transportation service providers, including move managers, would work as potential subcontractors to the GHC contractor rather than working directly with the military service shipping offices as they do in the ToS program, under the DP3, according to TRANSCOM. The GHC contractor would work with these providers as subcontractors to provide the capacity needed to pack, store, and transport household goods shipments. Although the services did not organize moves directly, according to officials, they continued to counsel service members and monitor performance quality. Specifically, the services were responsible for evaluating contractor performance against GHC requirements and documenting and reporting results to TRANSCOM. The services also directly approved invoices and authorized payment for GHC shipments, as they do in the ToS program, under the DP3.

DOD’s Transition to GHC Experienced Many Delays and Was Ultimately Terminated

In November 2021, TRANSCOM awarded the GHC to HomeSafe Alliance; several bid protests and a lawsuit challenging the contract award followed but were denied in 2022.[8] According to officials, both DOD and the contractor required additional time to develop IT systems for the GHC, leading to delays in implementation. TRANSCOM began conducting a small number of domestic, local shipments under the GHC in April 2024. For example, TRANSCOM conducted about 100 local shipments at 15 locations from April through August 2024. It then slowly expanded the number of locations and volume of shipments, and introduced intra- and interstate shipments, coordinating with the military services, U.S. Coast Guard, and the GHC contractor to determine when and where to increase the volume of shipments moving under the GHC.[9]

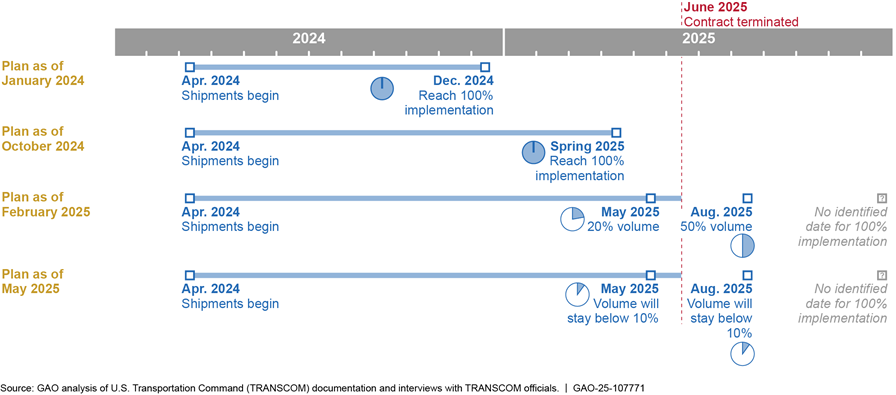

From April 2024 through June 2025, TRANSCOM continuously delayed implementation milestones and time frames in response to changing conditions regarding DOD site readiness and challenges with the contractor’s capacity and performance, as shown in figure 2.

Note: TRANSCOM refers to shipments between locations within the continental United States as domestic shipments. All shipments between, to and from locations outside the continental United States, including Alaska and Hawaii, are considered international shipments. According to officials, reaching 100 percent implementation meant managing all shipments for household goods across all locations under the GHC. GHC implementation for international shipments was likewise delayed. For example, in January 2024, TRANSCOM estimated that international shipments would begin in January 2025. By December 2024, TRANSCOM officials estimated international shipments would begin in September 2025, and by May 2025, officials did not have an estimated time frame for reaching 100 percent implementation for international shipments. Forty percent of DOD’s service member moves occur during peak season, which, according to officials, runs from May 15 through September 30.

TRANSCOM and service officials generally agreed that DOD site readiness required functional IT capabilities and contractor capacity in the area, and TRANSCOM officials stated that ensuring these requirements were met in some cases delayed GHC implementation. Officials from TRANSCOM, the services, and the contractor all acknowledged that contractor performance issues were largely due to the lack of a sufficient subcontractor network—also known as industry capacity—supporting the GHC. They also stated delaying implementation time frames was necessary to ensure a successful program transition.

According to TRANSCOM, as GHC shipment volume and geographic coverage increased, so did instances of poor performance, such as late or missed pickups and deliveries. For example, in 2025, the GHC contractor failed to pick up over 3,300 shipments and deliver over 3,600 shipments on time. According to TRANSCOM officials, to mitigate risks to customer service, TRANSCOM responded by issuing move task order terminations, show cause notices, contract discrepancy reports, and letters of concern regarding contract performance challenges.[10] TRANSCOM also reduced the number of shipments assigned to the GHC contractor by reverting certain geographic areas to ToS, according to officials. For example, according to documentation from a leadership meeting, in March 2025, TRANSCOM established a minimum lead time required to assign shipments to the GHC contractor, and officials said they limited shipments in locations where it was difficult to obtain transportation service providers.

Officials stated they expected this strategy could improve performance by better aligning GHC shipment volumes with the contractor’s actual capacity. However, the strategy did not reduce delays in GHC implementation and did not result in the contractor meeting established performance requirements. According to officials, this was due to inaccurate capacity information provided by the contractor to TRANSCOM. Specifically, out of about 20,000 shipments initiated with the contractor from April 2024 through June 2025, TRANSCOM officials stated that they terminated about 7,400 orders due to the contractor’s failure to meet performance requirements or lack of capacity to manage the shipments. Given the low volume of shipments carried out under the GHC, the department’s costs associated with invoiced GHC shipments totaled about $24 million as of April 2025—one year after GHC shipments began. In comparison, DOD annually spends approximately $2 billion on global household goods shipments in ToS.

In May 2025, the Secretary of Defense directed the creation of a Permanent Change of Station Joint Task Force, citing challenges with the GHC. DOD ultimately terminated the GHC in June 2025. The Task Force includes the Under Secretaries of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment and Personnel and Readiness, as well as TRANSCOM’s Defense Personal Property Management Office, among others. The Task Force is to develop recommendations for DOD’s strategic path forward for the program by September 5, 2025.[11]

DOD Did Not Have Adequate Information to Effectively Oversee the GHC

TRANSCOM did not have sufficient, comprehensive information about GHC (1) capacity, (2) performance, and (3) costs to effectively manage risks and oversee contract implementation. As a result, DOD faced continuous challenges implementing the GHC and terminated the contract in June 2025 due to the contractor’s inability to fulfill its contract obligations.

Capacity. TRANSCOM officials agreed that the contractor did not secure sufficient capacity needed to manage DOD’s relocation requirements, which thereby limited timely and effective GHC implementation.[12] TRANSCOM obtained some information regarding contractor capacity, but that information was not sufficiently accurate or comprehensive to fully manage risks and provide oversight of the contractor’s capacity to manage full DOD relocation requirements. The contractor was unable to secure the capacity needed to fulfill contract requirements, in part because of the following:

· Compensation for subcontractors was less competitive than market rates for moving services. DOD acknowledged in a May 2025 memo that GHC prices were in general lower than market rates in the ToS program, under DP3. ToS rates had increased rapidly in the years since the GHC was awarded. Officials from both TRANSCOM and the contractor stated that differences in rates between the ToS program and the GHC made the GHC less attractive for the moving industry and limited the contractor’s ability to build a sufficient subcontractor network. According to TRANSCOM officials, they did not have visibility into the rates the GHC contractor paid subcontractors. Some moving industry associations and companies we spoke with after the GHC was awarded told us that GHC rates were too low to cover costs of doing business and that consequently many companies would not carry out GHC shipments. Some companies that had carried out GHC shipments told us they were unlikely to continue to do so over the longer term, absent increases in their compensation from the GHC contractor. Further, some industry representatives told us some companies had already been or would consider exiting the military moving market in anticipation that a full transition to the GHC would make military moves unprofitable.[13]

· Service Contract Act minimum wage requirements raised concerns from industry representatives.[14] Moving industry representatives we spoke with told us they were unsure of how to apply certain requirements of the Act to their business models, and that existing guidance is vague. For example, industry representatives stated they had questions regarding compliance for multi-shipment loads from, to, and through multiple, separate locations with different wage requirements under the Act, or whether companies would be able to continue employing subcontractors and temporary labor, as they stated is common in the moving industry. Some also told us the Act requirements may be operationally or administratively burdensome for some smaller companies and therefore discouraged participation in the GHC.[15]

TRANSCOM had identified capacity constraints as a risk to GHC implementation and performance years before implementation. For example, Logistics Management Institute developed a GHC business case analysis for TRANSCOM in 2020, prior to GHC contractor selection, which identified capacity-related risks. In its report, Logistics Management Institute recommended that DOD review the results of the analysis once the department had selected a GHC contractor and better understood that contractor’s specific capabilities. TRANSCOM did not conduct additional analyses after the contract was awarded to reassess those risks, but did take some steps to assess risks during GHC implementation planning, such as establishing a risk management board, according to officials. In addition, a January 2024 DOD report to a congressional committee on GHC risk mitigation identified capacity-related risks but did not specifically address how TRANSCOM would conduct oversight of capacity to manage that risk as it implemented the GHC.

Despite identifying capacity as a risk to successful contract implementation, TRANSCOM did not collect sufficient information to conduct effective oversight of contractor capacity during GHC implementation. The contractor’s June 2021 proposal provided some information regarding how it expected to secure needed capacity.[16] TRANSCOM obtained capacity reporting information, such as the number of subcontractors and estimated number of shipments the GHC could manage; however, TRANSCOM officials stated that the GHC did not require DOD to verify those capacity reports.[17] Further, TRANSCOM officials stated that it was the responsibility of the contractor to obtain the needed capacity, which was what the government paid for as part of the contract.

The GHC did not specifically require the contractor to continuously provide TRANSCOM detailed information on its capacity. TRANSCOM officials stated in December 2024 they did not have access to business sensitive or proprietary information held by the contractor, such as detailed information regarding capacity. TRANSCOM officials stated they later obtained some information on contractor capacity in February 2025, after capacity issues led to poor performance, but that the information they received was limited. For example, they told us the contractor provided TRANSCOM a list of potential subcontractors that had signed an agreement with the contractor, but this list did not provide details on those companies’ actual capacity or willingness to carry out moves.[18] Further, TRANSCOM officials stated that information on capacity that was provided by the GHC contractor misrepresented the contractor’s capacity to manage shipments. For example, TRANSCOM officials stated that the GHC contractor had reported that it had the capacity to manage about 200,000 shipments per year, but the contractor was unable to successfully carry out the roughly 20,000 shipments it was assigned from April 2024 through June 2025.

Without accurate information regarding capacity to manage the risk to contract implementation, the volume of shipments TRANSCOM ordered from the contractor exceeded the contractor’s realistic capacity, resulting in performance failures and impacts on military families. According to officials, at the request of the contractor in February and April 2025, TRANSCOM had to move about 6,700 shipments it had assigned to the contractor back into ToS in order to meet the mission need for service member moves. Military service officials told us this caused substantial additional work for personal property shipping offices. TRANSCOM responded to the contractor’s capacity and performance issues by terminating some move task orders, preemptively moving some into ToS, issuing show cause notices to the contractor, and ultimately terminating the contract. As DOD identifies the path forward for its relocation program, ensuring it obtains comprehensive information on the moving industry’s capacity to meet DOD’s relocation needs would improve the department’s program management and oversight.

Performance. The GHC contractor generally did not meet performance requirements defined in the contract, according to DOD data, and we identified some limitations in the information DOD collected as part of its performance management process. TRANSCOM’s process for monitoring GHC performance included monitoring nine key performance indicators defined in the contract, including metrics for timeliness of shipment scheduling, pickup, and delivery, and customer satisfaction, among other things. TRANSCOM also established specific surveillance and quality assurance roles for TRANSCOM and military service offices. For example, quality assurance evaluators performed inspections during GHC moves.

TRANSCOM measured contractor performance on key performance indicators for each shipment, as well as overall, at least every month. According to TRANSCOM’s key performance indicator data, from January through June 2025, the GHC contractor failed to meet the defined performance thresholds for most key performance indicators, including timely scheduling, pickup, and delivery, and customer satisfaction. For example, according to DOD data, the GHC contractor picked up 64 percent of shipments on time, and delivered 58 percent of shipments on time.

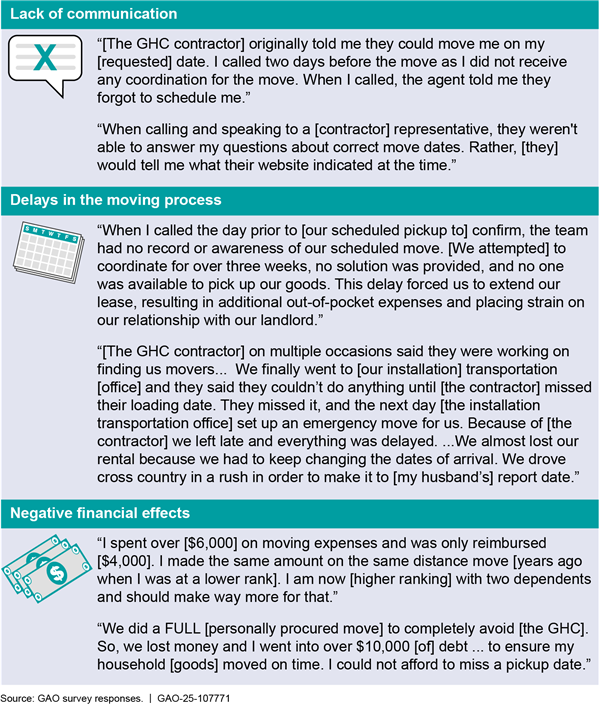

Additionally, we surveyed service members and spouses on their experiences moving under the GHC and found that poor contractor performance negatively affected military families. Survey respondents identified some challenges with GHC moves, such as inadequate communication with the contractor’s customer service representatives about the status of shipments, delays in multiple phases of the moving process, and decreased funding for personally procured moves.[19] For example, some respondents said their household goods arrived several days to weeks later than anticipated, and that the contractor was unable to provide answers regarding the status of their shipments. Some respondents also stated they did not hear from the contractor to schedule or confirm packing, pickup, or delivery, or that movers did not show up on the date or at the time they were expected. In addition, some respondents stated they incurred out-of-pocket costs to pay additional rent at their origin location or stay in a hotel, or that their families had to stay in their new homes for several days without their household goods or furniture while waiting for their household goods to be delivered.

Note: In June 2025, we conducted an anonymous, open-ended web survey of service members and spouses on their experiences with the Global Household Goods Contract (GHC). Our anonymous survey was designed to capture their views and experiences for illustrative purposes and results are not generalizable. We received 1,217 responses.

While DOD regularly used key performance indicators and quality assurance reporting from military service shipping offices to inform decisions about contract implementation and ultimately termination, DOD’s information and processes associated with performance management had some limitations due to the following:

· DOD lacked comprehensive feedback on service members’ experiences with the GHC. TRANSCOM used customer satisfaction surveys to collect information on satisfaction with personal property moves in both the ToS and the GHC. Under the GHC, service members electronically received up to five separate surveys after completing each stage of their moves.[20] However, officials stated service members did not receive a survey when the contractor failed to carry out or complete a specific stage of a move. For example, they told us if a service member’s GHC move was never picked up by the contractor and instead transferred into ToS, that service member would not receive a survey regarding the GHC contractor’s pickup services. According to TRANSCOM officials, the customer satisfaction survey was intended to measure only satisfaction with services provided. However, not providing a survey to customers who had experienced such failures limited TRANSCOM’s formal feedback on the full range of experiences with the GHC. As a result, TRANSCOM lacked full information on military families’ perspectives on the GHC and therefore was less able to ensure its evidence was sufficient to evaluate GHC performance on overall customer satisfaction, a metric that was an important program goal for DP3 reforms, according to TRANSCOM.[21]

· DOD faced challenges with the quality assurance processes that affected performance management. For example, officials from five of the nine joint personal property shipping offices we met with told us they had less authority to intervene on quality issues during a move than they did under ToS. They told us that under ToS, they could provide real-time direction to correct errors or unsafe conditions, such as the mishandling of household goods during a move. However, some officials stated that under the GHC, joint personal property shipping offices could only document and report any quality issues to TRANSCOM, and TRANSCOM would address those issues with the GHC contractor, who would in turn take action to address problems with its subcontractors.

· Officials from joint personal property shipping offices described challenges arising from data inconsistencies across the contractor and government IT systems for the GHC. For example, officials from five of the nine joint personal property shipping offices we met with said scheduled packing and pickup dates were sometimes different across IT systems, which made it difficult to schedule quality assurance inspections. Officials also said they had to take on extra work to determine correct dates and ensure moves proceeded as scheduled, as well as to develop workarounds for this issue.

As DOD considers next steps for its relocation program, ensuring its performance management processes incorporate key information—including comprehensive feedback from service members—and enable effective quality assurance would position the department to more effectively manage and oversee its program.

Costs. TRANSCOM lacked complete information regarding costs associated with the GHC transition. Specifically, DOD incurred unplanned transition costs, paid management fees for task orders ultimately not completed by the contractor, and lacked clarity on how GHC costs compared to ToS costs, as discussed below:

· DOD incurred higher costs than anticipated for the transition to the GHC. Specifically, the contract included $54 million over 9 months to pay for administrative expenses and IT development and integration needed to transition ToS to the GHC. However, according to TRANSCOM, in February 2024, the contract was modified to incorporate an amount up to an additional $60 million over one year for these transition costs. According to officials, this increase was due to the need for more time and further work to fully develop and integrate IT systems for the domestic implementation of the GHC and to address issues regarding implementation delays arising under the contract. In addition, officials from TRANSCOM and the GHC contractor we interviewed provided conflicting perspectives about a need for additional transition costs to develop IT capabilities for implementation of the GHC for international shipments. The GHC contractor stated additional funding would be needed to develop those capabilities. TRANSCOM officials stated they did not plan to pay additional transition costs for the international program, specifically because the GHC performance work statement already required that the contractor provide, maintain, and integrate an IT system to manage worldwide household goods relocation services.

· DOD paid up-front management fees for work not performed—specifically for shipments that were assigned to, but ultimately not completed by, the contractor. Per the contract terms, the services paid the GHC contractor an immediate management fee of approximately $563 per move task order for administrative costs associated with managing the shipments.[22] According to TRANSCOM officials, these included task orders that were subsequently terminated by DOD or returned to DOD by the GHC contractor due to inability to carry out those task orders, meaning DOD had paid for work not performed by the contractor. TRANSCOM officials stated that they had issued a demand for payment from the contractor of about $3.2 million to cover already paid management fees for about 7,400 terminated task orders. However, as of June 2025, the contractor had appealed those task order terminations, litigation was ongoing, and no reimbursement had occurred.

· DOD lacked clarity on whether the GHC would be more cost effective for the department than ToS. Although cost savings was not a primary goal of the GHC according to TRANSCOM officials, in February 2023, prior to initial shipments under the GHC, TRANSCOM reported to Congress that it expected the GHC to save the department about $2.23 billion over 5 years. However, in 2024, after initial shipments under the GHC began, TRANSCOM officials had not determined the extent of potential cost savings and reiterated that the goal was not cost savings but improved customer experience for service members and their families. According to officials, TRANSCOM conducted some analysis to compare GHC and ToS costs but did not complete a detailed analysis of cost differences, in part because cost structures of the contract and ToS differed. For example, the base rates differed in each program, and the GHC did not incorporate certain accessorial costs permitted in ToS.[23] In addition, in August 2025, TRANSCOM officials stated that clarity on whether the GHC would be more cost effective than ToS could not be determined. Specifically, they stated TRANSCOM did not have enough time between when ToS rates for peak season 2025 were finalized in April 2025 and the GHC was terminated in June 2025 to complete such an analysis.

At the direction of the Secretary of Defense, DOD is currently working to develop recommendations for the long-term reform of and strategic path forward for DP3. DOD is also considering additional changes to its relocation program that include reductions in the number of military moves and permanent change of station budgets. Greater clarity on cost implications of all potential changes would help DOD make better informed decisions regarding the future of the program.

Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that management should identify information requirements needed to achieve the objectives of a program and address risks, use quality information for decision making, and evaluate identified issues and determine appropriate corrective actions to remediate deficiencies.[24] Key practices for evidence-based policymaking include using and leveraging evidence to understand why desired results were not achieved and to inform decision making, such as changes to strategies to achieve better results.[25]

DOD’s process for managing risks and overseeing GHC implementation did not enable TRANSCOM to collect comprehensive information needed for effective program management and oversight. Specifically, DOD had not ensured its process for program management and oversight incorporated comprehensive information on capacity, performance, and costs. As DOD considers its strategic path forward after GHC termination, understanding and mitigating information gaps that negatively affected GHC risk management and oversight would help inform DOD’s efforts to identify changes needed for its relocation program to meet TRANSCOM’s mission and program goals of providing high-quality moves for service members and improving transparency and accountability. Ensuring there is a process in place to obtain more comprehensive information on program capacity, performance, and costs as DOD moves forward will better position them and Congress to manage risks and oversee the program effectively.

Conclusions

Implementing the GHC was intended to address challenges in DOD’s existing relocation program by improving move quality, accountability, and customer experience. However, DOD found that the GHC contractor was unable to fulfill contract requirements, and sustained capacity and performance challenges led DOD to terminate the contract after spending millions. While the department had a performance monitoring and oversight structure in place for the GHC, it lacked comprehensive information on contractor capacity, performance management, and program costs, which would have better positioned DOD to oversee contract implementation and appropriately manage risks. DOD is currently considering how it might move forward and improve its program. As it does so, obtaining comprehensive information related to capacity, performance, and costs will better position DOD to ensure it can effectively oversee its program in the future.

Recommendation for Executive Action

The Secretary of Defense should—as the department develops its path forward for DP3—ensure that the Under Secretaries of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment and Personnel and Readiness, in coordination with TRANSCOM Defense Personal Property Management Office, obtain comprehensive information needed on capacity, performance, and costs to effectively oversee and manage risks to DOD’s personal property program. (Recommendation 1)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to DOD and the Department of Labor (DOL) for review and comment. In its comments, reproduced in appendix II, DOD concurred with our recommendation. DOD and DOL provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Defense, and the Secretary of Labor. In addition, the report is available at no charge on our website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at CzyzA@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix III.

Alissa H. Czyz

Director, Defense Capabilities and Management

The House report accompanying a bill for the Servicemember Quality of Life Improvement and National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2025 included a provision for us to review the Department of Defense’s (DOD) management and oversight of the Global Household Goods Contract (GHC).[26] Our report (1) describes DOD’s implementation of the GHC; and (2) assesses the extent to which DOD had the information needed to effectively oversee contract implementation.

To address these objectives, we reviewed relevant documentation, including GHC documentation, the Federal Acquisition Regulation, DOD guidance related to personal property shipments, and documentation that described plans for GHC implementation.[27] We interviewed U.S. Transportation Command (TRANSCOM) and Army, Marine Corps, Navy, and Air Force officials responsible for executing and overseeing the Defense Personal Property Program (DP3) and the GHC, including the nine joint personal property shipping offices executing GHC shipments. We also met with a non-generalizable sample of about 40 moving industry associations and moving companies, including the GHC contractor. We identified initial industry associations to interview based on our prior work on DP3 and the GHC.[28] From these interviews, we solicited recommendations for additional associations and moving companies to speak with. We also identified some stakeholders through our own research. Moving companies we interviewed ranged in size—including large national van lines and smaller, local movers—and in experience with DOD moves and the GHC.

We conducted two in-person site visits at locations where the GHC was first implemented, which were among those with the largest volumes of GHC shipments. To develop our sample of installations for the site visits, we reviewed a list of all locations where the GHC was implemented as of December 2024. From that list we then identified nine joint personal property shipping offices across the continental United States that had begun carrying out GHC moves and had conducted at least one shipment.[29] From these nine offices, we selected our two site visit locations—Joint Personal Property Shipping Office Northwest (at Joint Base Lewis-McChord, Washington) and Consolidated Personal Property Shipping Office Norfolk (at Naval Station Norfolk, Virginia). These locations were among the first of these offices to begin carrying out GHC moves and among those with the highest volume of shipments, based on TRANSCOM data current at the time of site selection.

We conducted virtual, semi-structured interviews with the seven remaining joint personal property shipping offices to obtain information on GHC implementation in their geographic areas of responsibility, including information on GHC benefits and challenges, and management and oversight of the GHC at the military service and installation levels. During the in-person site visits and virtual, semi-structured interviews, we met with leaders at the joint personal property shipping offices, including office directors, deputy directors, and supervisors of functional teams—such as quality assurance, ordering, and invoicing.

For our first objective, we reviewed DOD and contractor GHC implementation plans to describe DOD’s contract implementation in fiscal year 2022 through contract termination in June 2025. We also interviewed officials at TRANSCOM and the military services, including the joint personal property shipping offices, regarding GHC implementation and related challenges. Further, we interviewed industry association representatives and moving companies, including the GHC contractor, to discuss their perspectives on GHC implementation. We also requested and reviewed information from TRANSCOM on the volume of shipments under the GHC and contractor capacity.

For our second objective, we reviewed contract documents, as well as DOD guidance and other documentation outlining requirements for and efforts taken by DOD to oversee and collect information regarding contractor capacity, performance, and program costs. We interviewed TRANSCOM, military service, and industry officials to discuss the extent to which DOD had the information needed to oversee GHC implementation. In addition, we interviewed the GHC contractor, industry associations, and moving companies regarding DOD’s oversight of GHC implementation.

Further, we reviewed GHC performance and cost data. Specifically, we obtained and reviewed TRANSCOM data on the contractor’s performance on key performance indicators defined in the contract and on GHC costs—including costs for transitioning DP3 to the GHC and for shipments carried out and invoiced under the GHC. To determine the reliability of the data, we reviewed supporting documentation and interviewed knowledgeable officials. We determined that the data were sufficiently reliable for reporting general information on GHC performance and costs associated with the program.

In June 2025, we also conducted an anonymous, open-ended web survey of service members and their spouses on their experiences with the GHC, including challenges, benefits, and effects. Our anonymous survey was designed to capture their views and experiences for illustrative purposes. The survey results are not generalizable. The survey asked primarily open-ended questions about the challenges and benefits of moving under the GHC, as well as the effects of those challenges or benefits for military families. We pretested the survey with two service members and one spouse to ensure questions were clear, interpreted consistently, and answerable. We analyzed the survey for illustrative examples and quotes regarding the challenges and effects of moving under the GHC. We received 1,217 responses.

We compared DOD’s process for managing and overseeing the GHC to internal control standards and key practices for evidence-based policymaking related to identifying information requirements needed to achieve the objectives of a program and address risks, determining corrective actions, and leveraging evidence to understand why desired results were not achieved and to inform decision making.[30]

We conducted this performance audit from August 2024 to September 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

GAO Contact

Alissa H. Czyz, CzyzA@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact listed above, Suzanne Perkins (Assistant Director), Andrew Altobello (Analyst in Charge), Nicole Ashby, Gina Hoover, Amie Lesser, Angie Nichols-Friedman, Jordan Tibbetts, Guiovany Venegas, Theologos Voudouris, and Nathaniel B. Walker made key contributions to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]In October 2020, GAO sustained a bid protest from HomeSafe Alliance against the initial award of the contract to another company, HomeSafe Alliance, LLC, B-418266.5 et al., Oct. 21, 2020, 2020 CPD ¶ 350, after which DOD recompeted and awarded the contract to HomeSafe Alliance in November 2021. See also Connected Global Solutions, LLC, B-418266.4, B-418266.7, Oct 21, 2020.

[2]H.R. Rep. No. 118-529, at 122-23 (2024).

[3]We conducted our survey in June 2025. Findings from the survey are not generalizable but provide illustrative examples of these individuals’ experiences.

[4]DOD Instruction 4500.57, Transportation and Traffic Management (Mar. 7, 2017) (incorporating change 4, effective Dec. 11, 2024). DP3 administers government-contracted shipping and storage programs for household goods and privately owned vehicles for service members, the U.S. Coast Guard, DOD civilians, and their families. The military services reimburse TRANSCOM for program and operating costs based on the proportion of their personnel’s shipments administered through the program, according to TRANSCOM officials.

[5]The Defense Personal Property System is a web-based system that supports the DP3 with management, invoicing, damage claims, and quality assurance of DOD personal property shipments.

[6]Transportation service providers operate through “channels,” or combinations of origin and destination locations, within and outside the continental United States. TRANSCOM refers to its existing household goods shipment program—within the broader DP3—as the tender of service program. A “tender of service” is an offer by a qualified carrier to provide transportation service to DOD at specified rates or charges and is submitted to a central authority for acceptance—TRANSCOM, in the case of household goods. See Department of Defense 4500.9-R, Defense Transportation Regulation, Definitions (Nov. 8, 2019).

[7]According to TRANSCOM officials, joint personal property shipping offices are regional offices that typically execute and oversee DOD’s relocation program within geographic areas of responsibility. Personal property shipping and processing offices are installation-level offices that execute specific functions within the program. For example, the processing offices oftentimes provide counseling for service members on the relocation process and the shipping offices conduct quality assurance inspections.

[8]See Connected Global Solutions, LLC, B-418266.10, B-418266.12, Mar. 3, 2022; American Roll-On Roll-Off Carrier Group, Inc., B-418266.9 et al., Mar. 3, 2022; Connected Global Solutions, LLC v. United States, 162 Fed. Cl. 720 (Fed. Cl. 2022). Separate from the initial challenges to the contract award, a lawsuit was brought in the U.S. Court of Federal Claims in November 2024 alleging that changes to the contract should have resulted in a new solicitation; the court dismissed the case as moot in July 2025 following termination of the contract. Suddath Co. v. United States, 2025 U.S. Claims LEXIS 1185 (Fed. Cl. 2025).

[9]During initial implementation, TRANSCOM evaluated installations’ readiness, including IT and staff training, and contractor performance to determine where and at what volume to implement the contract. Officials stated doing so enabled them to identify and rectify challenges on a small scale and better manage risks. By March 2025, TRANSCOM reported that the GHC was technically operational for shipments to and from most locations within the continental United States.

[10]A show cause notice is a formal notification from the government to a contractor requiring a contractor to explain why it has failed to fulfill certain contract requirements. Under the GHC, contract discrepancy reports were considered punitive action against the contractor and used to formally report, track, and resolve significant performance deficiencies. Letters of concern were sent to the contractor to formally express concerns about performance.

[11]Secretary of Defense Memorandum, Implementation Memorandum for Permanent Change of Station Task Force (June 13, 2025).

[12]Under the GHC, the contractor was expected to use a network of subcontractors to provide the capacity needed to pack, store, and transport household goods shipments. Based on this model, the government would order moving services from the GHC contractor, which in turn would coordinate with its network of subcontractors to carry out individual moves.

[13]The GHC defined a process for adjusting contract prices annually to protect the government and the contractor against significant market fluctuations. Adjustments were expected to be calculated using market indices and executed via contract modifications. According to officials, at the time of contract termination, DOD and the GHC contractor were negotiating but had not yet executed a price adjustment. Officials told us that they anticipated that such a price adjustment would have better aligned GHC prices with market rates and therefore attracted more subcontractors for the GHC.

[14]Under this Federal Acquisition Regulation-based services contract, the GHC contractor and subcontractors were required to comply with the McNamara-O’Hara Service Contract Act of 1965, codified at 41 U.S.C. §§ 6701-07, which requires that contractors and subcontractors meet certain minimum wage requirements based on the locality in which work is performed, meet safety and health standards, and maintain appropriate records, among other things. Specifically, the Act requires that employees performing services on contracts exceeding $2,500 must be paid no less than the monetary wages and fringe benefits required by the Secretary of Labor for the locality in which the employees are working.

[15]The Service Contract Act requirements generally do not apply to contracts for the carriage of freight or personnel by vessel, airplane, bus, truck, express, railway line, or oil or gas pipeline where published tariff rates are in effect; see 41 U.S.C. § 6702(b)(3). DP3 falls within this exemption because it is governed by published tariff rates.

[16]The GHC solicitation required offerors to address capacity as part of their proposals. The selected contractor’s proposal stated it would leverage existing relationships in the moving industry, secure additional committed capacity through incentives, and increase effective capacity through route optimization.

[17]The contract required monthly transition reports during the transition period ending in February 2025 to include a statement on the service areas, or channels, the contractor was ready to assume. Transition reports contained some general information on the contractor’s capacity but were not required to include details such as a list of moving companies that had committed capacity to the GHC, or in-depth descriptions of efforts to expand contractor capacity.

[18]According to the contractor, potential subcontractors had to sign a master service agreement to obtain information regarding participation in the GHC, such as compensation rates, although subcontractors that signed this agreement were not specifically required to carry out any shipments under the GHC unless they chose to do so.

[19]Service members may choose to arrange their own household goods shipment, called a personally procured move. The government reimburses the service member based on the amount it would have cost the government to move the same goods through a contracted carrier. Because the GHC contractor’s rates were lower than rates in the ToS program, reimbursements for personally procured moves under the GHC may have been lower than reimbursements received in previous years or in areas where the GHC was not active.

[20]These included surveys on a service member’s experience with pre-move counseling; origin services (i.e., pickup); destination services (i.e., delivery); and damage claims.

[21]In November 2024, we reported that TRANSCOM did not sufficiently address or analyze the risk of nonresponse bias in its customer satisfaction survey as part of the prior DP3 program. In March 2025, DOD indicated it would take a series of phased actions to assess and address risks related to nonresponse bias for the survey with estimated completion dates between January 2026 and January 2028. See GAO, Coast Guard: Better Feedback Collection and Monitoring Could Improve Support for Duty Station Rotations, GAO‑25‑107238 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 18, 2024).

[22]This shipment management fee increased each year of the contract. For example, in base year 1, the fee was $557 and was increased to $562.55 for base year 2.

[23]Accessorial costs are charges for additional services provided by moving companies that can vary based on several factors such as size of shipment. According to TRANSCOM officials, under ToS, DOD authorized accessorial charges for most services that go beyond standard services, such as special handling for heavy items. These officials stated that under the GHC, fewer separate accessorial charges were allowed and the most common charges, such as for crating fragile personal property, were solicited for and included in the contract pricing.

[24]GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO‑14‑704G (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 10, 2014).

[25]GAO, Evidence-Based Policymaking: Practices to Help Manage and Assess the Results of Federal Efforts, GAO‑23‑105460 (Washington, D.C.: July 12, 2023).

[26]H.R. Rep. No. 118-529, at 122-23 (2024).

[27]Defense Transportation Regulation, Individual Missions, Roles, and Responsibilities (Apr. 18, 2025); DOD Instruction 4500.57, Transportation and Traffic Management (Mar. 7, 2017) (incorporating change 4, effective Dec. 11, 2024); DOD Directive 4500.09, Transportation and Traffic Management (Dec. 27, 2019) (incorporating change 1, effective Oct. 21, 2022); U.S. Transportation Command Instruction 1600.02A, vol. 11, Organizations and Functions – Defense Personal Property Management Office (DMPO/TCJ9) (Sept. 15, 2023).

[28]GAO, Movement of Household Goods: DOD Should Take Additional Steps to Assess Progress toward Achieving Program Goals, GAO‑20‑295 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 6, 2020).

[29]According to TRANSCOM officials, joint personal property shipping offices typically execute and oversee DOD’s relocation program within geographic areas of responsibility. According to TRANSCOM, the GHC was implemented at specific sites across the continental United States—including joint personal property shipping offices—based on shipment volumes, DOD shipping office capabilities and workforce experience, and contractor capabilities.

[30] GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO‑14‑704G (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 2014); Evidence-Based Policymaking: Practices to Help Manage and Assess the Results of Federal Efforts, GAO‑23‑105460 (Washington, D.C.: July 12, 2023).