OFFICE OF NATIONAL DRUG CONTROL POLICY

Experts' Views on Developing and Evaluating Media Campaigns Intended to Prevent Drug Misuse

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional committees.

For more information, contact: Triana McNeil at McNeilT@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

The 12 experts in a forum GAO convened said that to develop effective media campaigns and evaluate media campaigns, whether on drug misuse prevention or other topics, campaigns need to consider the following:

· Identify and understand intended audience. Once a campaign has identified who it wants to reach, it needs to understand the intended audience—including by identifying the underlying causes of the behavior the campaign wants to change. For example, experts noted that campaigns may decide to target the underlying reasons why people misuse drugs rather than developing campaigns to target specific drugs.

· Create content, select messengers, and decide on delivery methods. Campaigns need to create content to deliver their messages, which need to be credible and relevant for the intended audience. Campaigns also need to select messengers to deliver their messages, such as community leaders. Additionally, campaigns need to decide how to deliver their messages. For example, campaigns may use print and social media, among other options.

· Test messages. Campaigns need to test their messages with the intended audience to ensure that the messages are relevant and resonate with the intended audience. This testing can include using focus groups, interviews, or surveys, among other methods.

· Define the intended outcome. Campaigns need to have a clear understanding of what they are trying to achieve. Then, evaluators can decide what data are needed to determine whether a campaign is meeting its goals.

· Select qualified evaluators. Campaigns need independent evaluators who can speak to campaign managers about a campaign’s effectiveness using evidence from evaluations. Evaluators need expertise in research methods, evaluation, and other disciplines and need to understand the campaign substance.

· Decide when and how to measure effectiveness. Campaigns need to decide if they will evaluate the campaign while it is ongoing or after the campaign has concluded. They also need to decide what they want to measure and what data collection methods they will use.

Why GAO Did This Study

Drug misuse—the use of illicit drugs and the misuse of prescription drugs—has been a persistent and long-standing public health issue in the U.S. In recent years, hundreds of thousands of people have died from misusing drugs. The Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP) manages the National Anti-Drug Media Campaign, which aims to change attitudes about drug use and reverse drug use trends through targeted media advertisements.

The Substance Use-Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment (SUPPORT) for Patients and Communities Act includes a provision for GAO to review various ONDCP activities, including national media campaigns.

On February 11, 2025, GAO convened a forum with 12 experts selected for their expertise in public media campaigns, including but not limited to campaigns intended to prevent drug misuse. The experts discussed considerations for developing and evaluating media campaigns.

GAO selected experts to represent a range of experiences and viewpoints from academic institutions; nonprofit, communications, and consulting organizations; and federal and state governments. Experts reviewed a draft of our summary of their comments. Their comments were incorporated as appropriate. Views expressed during the proceedings do not necessarily represent the opinions of all experts, their affiliated organizations, or GAO.

GAO provided a draft of this report to the Departments of Health and Human Services and Justice and ONDCP for review. They did not have any comments on the report.

Abbreviations

|

CDC |

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

|

NASEM |

National Academies of Sciences,

Engineering, and |

|

ONDCP |

Office of National Drug Control Policy |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

July 30, 2025

Congressional Committees

From 2021 to 2023, the number of drug overdose deaths in the U.S. exceeded 100,000 per year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). In recognition of the significant loss of life and harmful effects resulting from drug misuse, we added national efforts to prevent, respond to, and recover from drug misuse to our High-Risk List in 2021.[1] While provisional data from the CDC for the 12-month period ending in December 2024 show overdose deaths declined to approximately 80,000, drug overdoses continue to be high. In addition, in March 2025, the Department of Health and Human Services renewed a 2017 determination marking the opioid crisis as a public health emergency.

The federal drug control budget for fiscal year 2024 was $43.6 billion, and the government has enlisted more than a dozen agencies to address drug misuse and its effects. The Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP), a component of the Executive Office of the President, is responsible for overseeing implementation of the nation’s drug control policy and leading the national drug control effort.[2] ONDCP’s work includes managing national media campaigns intended to change attitudes about drug use and reverse drug use trends.[3]

We conducted this work under the Substance Use-Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment (SUPPORT) for Patients and Communities Act, which includes a provision for us to review various ONDCP activities, including national media campaigns.[4] This report addresses the following questions:

1. What campaigns did ONDCP’s National Anti-Drug Media Campaign conduct from fiscal year 2018 through April 2025?

2. What are experts’ views on how to develop an effective media campaign?

3. What are experts’ views on how to evaluate media campaigns?

To answer our first research question, we interviewed ONDCP officials about media campaigns ONDCP has conducted over the past 10 years and reviewed ONDCP documentation about these campaigns. In addition, we reviewed prior GAO reports that included information about ONDCP’s media campaigns.[5]

To answer our second and third research questions, on February 11, 2025, we convened a group of 12 experts selected in coordination with the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Mathematics for their relevant expertise in public media campaigns, including but not limited to campaigns intended to prevent drug misuse. The experts, selected to represent a range of experience and viewpoints, were from academic institutions; federal and state governments; and communications, consulting, and nonprofit organizations.

We summarize the discussion among the experts, capturing the ideas and themes that emerged from the collective discussion.[6] Comments expressed during the proceedings do not necessarily represent the views of all experts, the organizations with which they are affiliated, or GAO. The forum was structured as a guided discussion with experts encouraged to openly comment on issues and respond to one another; not all experts commented on all topics. Following the forum, we gave experts the opportunity to review and comment on a draft of this summary, which was based on a transcript of the forum proceedings.

See appendix I for a full description of our scope and methodology. See appendix II for a list of the forum experts.

We conducted this performance audit from September 2024 to July 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

ONDCP’s mission is to reduce substance use disorder and its consequences by coordinating the nation’s drug control policy through developing and overseeing the National Drug Control Strategy and National Drug Control Budget.[7] ONDCP manages the Drug-Free Communities Support Program and the High Intensity Drug Trafficking Areas Program.[8] The Drug-Free Communities Support Program provides grants to community-based coalitions that engage multiple sectors of the community to prevent youth substance use.[9] The High Intensity Drug Trafficking Areas Program coordinates and assists federal, state, local, and Tribal agencies to reduce drug trafficking and drug production in the United States.

ONDCP also manages the National Anti-Drug Media Campaign, which aims to change attitudes about drug use and reverse drug use trends through targeted media advertisements. Between fiscal years 1998 and 2006, ONDCP was appropriated over $1.4 billion for the National Youth Anti-Drug Media Campaign. The campaign aimed to prevent the initiation of or curtail the use of drugs among the nation’s youth. We reported on the campaign in August 2006, when our review of program evaluations provided credible evidence that the program’s activities focused on marijuana use were not effective at reducing youth drug use.[10] As a result, we recommended that Congress consider limiting appropriations for the media campaign until ONDCP provides credible evidence of the effectiveness of exposure to the campaign on youth drug use outcomes.[11] We also suggested to Congress that an independent evaluation of the new campaign be considered as a means to help inform both ONDCP and Congressional decision-making. Congress implemented our recommendation by limiting appropriations and requiring that ONDCP report to Congress with recommendations on the development of improved and meaningful measurements of the effectiveness of the media campaign.

ONDCP Conducted Two National Anti-Drug Media Campaigns from 2018 Through April 2025

As of April 2025, ONDCP’s National Anti-Drug Media Campaign has not received an appropriation since 2011, following Congress’s decision to implement our 2006 recommendation. However, ONDCP has undertaken two media campaigns in the last 10 years, The Truth About Opioids and the Real Deal on Fentanyl using its no-year carry-over and recovery funds from amounts available for that purpose, according to ONDCP officials.[12]

· ONDCP conducted The Truth About Opioids campaign in collaboration with the Ad Council and Truth Initiative from June 2018 through August 2019.[13] The campaign focused on preventing and reducing misuse of opioids among youth and young adults. The Truth Initiative evaluated this campaign and found it increased awareness of opioid misuse in young people, among other accomplishments.

· ONDCP has been conducting the Real Deal on Fentanyl campaign in collaboration with the Ad Council since 2022 to increase awareness of the dangers and prevalence of fentanyl.[14] According to ONDCP officials, the campaign will continue through August 2025. These officials told us the Ad Council pays an independent evaluator to conduct a monthly field tracking study on advertisement awareness. ONDCP also receives metrics about the campaign’s reach, such as webpage views and social media interactions. For example, ONDCP reported that the campaign website has received 5.6 million visitors since the campaign’s launch in its Congressional Budget Submission for Fiscal Year 2026.[15]

As of November 2024, ONDCP had no funds remaining for future media campaigns, according to ONDCP officials. Additionally, in its Congressional Budget Submission for Fiscal Year 2026, ONDCP did not request any funds for the National Anti-Drug Media Campaign.[16] The submission also stated, however, that seven manufacturers of Federal Drug Administration-approved opioid products have announced they will donate funds to expand the reach of the Real Deal on Fentanyl campaign. Additionally, ONDCP officials told us that if an emerging drug threat is designated, ONDCP will determine if a national anti-drug media campaign would be feasible and appropriate to address the threat.[17]

Considerations for Developing Effective Media Campaigns

The 12 forum experts told us that to develop an effective media campaign, whether on drug misuse prevention or other topics, the campaign needs to (1) identify and understand the intended audience, (2) create content, select messengers, and decide on delivery methods, and (3) test its messages before deploying the campaign.

Campaigns Need to Identify and Understand the Intended Audience

The first step to developing a campaign is to identify who the campaign wants to reach, or the intended audience, forum experts noted. The intended audience could include a primary and secondary intended audience, or the general public.

· Primary intended audience. The primary intended audience includes the people whose behavior the campaign is intended to influence. These are the people who are most at risk for a behavior and are willing to change their behavior. For drug prevention campaigns, this can include individuals who are open to drug use.

· Secondary intended audience. Campaigns may also identify a secondary intended audience, particularly if the primary intended audience is difficult to reach. These are the entities who are close to and interact with the primary intended audience, including friends, family, and community organizations. These people can have discussions with the primary intended audience, about the behavior that the campaign wants to address. For example, one expert described a campaign that encouraged women to talk with their family members about the importance of getting mammograms when trying to influence Black women ages 40 to 64 to get them.

· General public. Some campaigns may target the general public as their intended audience. For example, campaigns aiming to reduce stigma about drug use or drug treatment options may encourage the general public to carry the overdose reversal drug, naloxone.

Forum experts explained that once the campaign has identified the intended audience, it needs to work to better understand the intended audience.[18] Specifically, the campaign needs to identify the underlying causes of the behavior that the campaign wants to change. For example, experts noted that the drugs people misuse continuously change. Rather than developing campaigns to target specific drugs as they become more common, campaigns may instead target the underlying reasons why people choose to misuse drugs, such as social isolation or anxiety.

Additionally, campaigns can seek to understand people’s reasons for choosing not to misuse drugs and design a campaign to encourage those protective behaviors. This could include promoting ways to mitigate stress, encouraging conversations about mental health, and directing people to resources they need such as housing and food assistance, according to forum experts.

Finally, forum experts noted that the campaign needs to consider the intended audience’s readiness to receive the campaign’s messages. For example, a campaign about improving mental health directed to a community without running water will not be effective because it is not addressing the community’s more immediate needs.

Forum experts suggested campaigns use population data to understand the intended audience’s behavior around the campaign’s specific issue. For example, an expert involved in a bowel screening campaign said population monitoring helped the campaign understand who was intending to screen, refusing to screen, or unaware of the need to screen for bowel cancer. The population data revealed that most of the people who had not screened intended to do so but had not prioritized it nor taken the steps to get it done. By using available data to inform decisions about the campaign’s messages, campaigns can also avoid outside influence and maintain independence, according to forum experts.

Campaigns Need to Create Content, Select Messengers, and Decide on Delivery Methods

Forum experts told us that campaigns need to create content, select messengers, and decide how they intend to deliver messages to the intended audience during the campaign’s design phase.

Creating Content

Campaigns need to create content to deliver their campaign messages. Forum experts mentioned the following items that campaigns need to consider when creating content:

· Theory of the campaign. Campaigns need to have a theory for what they are trying to change and how the campaign will affect that change. For example, one expert described a drug prevention media campaign that outlined the expected effects, including individual belief change, peer and parental social influences on individual belief, and institutional action affecting individual decisions. Campaigns need to have a clear understanding of their goal and align their strategy with that goal. To do so, campaigns need to understand the existing body of research on what is and is not effective and be grounded in evidence of effectiveness.

· Co-creating with the intended audience. Campaigns need to be built with the communities the campaign seeks to serve. They need to listen to what the intended audience wants and what is important to them, as well as what is appropriate for them. Members of the intended audience can be involved in creating content, such as having community members create campaign messages in their own languages. Campaigns need to avoid translating the words of campaign messages from one language to another because simple translation may disregard culture and nuance for the intended audience. Additionally, youth can co-create messages to reach their peers in their communities. To represent different communities within the intended audience, campaigns also need to include a variety of voices during development—including diversity in race, ethnicity, demographics, discipline, and thought.

· Characteristics of the message. Campaign messages need to be relevant, believable, credible, and easy to understand. Campaigns need to carefully consider the tone of their messages to mitigate backlash and eroding trust with the intended audience. Campaigns may build on cultural moments, such as trends on social media, to keep their messages current and to reach a wider audience. Finally, campaign messages can break down complex problems into smaller components and offer steps for meaningful progress. For example, one expert described how a drunk driving prevention media campaign identified a narrowly focused approach that could achieve progress at the time—by popularizing the concept of the designated driver. This concept provided a simple, concrete message with a call to action that led to progress.

· Segmenting. Campaigns need to segment different groups within the intended audience and ensure that the campaign’s messages resonate with these segmented audiences, including on the local level. For example, within the audience of active smokers, there are “delayers” (the people who know they should quit smoking but are putting it off for now) and “tryers” (the people who have tried and failed to quit smoking). The campaign could tailor its messages to reach each group. Some messages may be universal, and a national campaign can provide an umbrella message that can be adapted to local conditions.

· Appeals. Campaigns may appeal to the intended audience using positive or negative emotions. Appeals using positive emotions may frame the campaign around the intended audience’s near-term goals and aspirations and use themes such as resiliency, agency, and self-affirmation or build on relationships, friendships, and cultural norms. These appeals can also include a call to action, such as advising the audience to do something good rather than telling them not to do something the campaign says is bad. Appeals using individual decision making are more effective than authoritarian approaches that tell the audience what to do, which takes away their agency.

Appeals using negative emotions may frame the campaign around consequences, fear, or risk. However, experts stated that campaigns based on fear tactics alone are not proven to be effective and that it is important to be truthful in campaign messages. Negative emotional appeals can work when paired with suggestions regarding what the audience can do. They can also work to raise awareness but need to balance seriousness or urgency with hope or action. Experts noted that when trying to improve people’s beliefs in their capability to change, other emotions work better than negative appeals.

· Storytelling approaches. Campaigns may also consider various approaches for delivering the message to the intended audience. For example, campaigns may use storytelling to activate emotions to help the message resonate with the intended audience. Storytelling can be an effective approach to show what an issue looks like in real life for people in the community. For example, having people recovering from addiction talk about what worked for them and how they changed their situation could resonate with people currently experiencing addiction.

Selecting Messengers

Forum experts stated that campaigns need to use trusted messengers to deliver campaign messages, allowing the intended audience to feel that it had a part in building the messages. Forum experts mentioned the following types of messengers that campaigns may consider using:

· Community leaders.[19] Community leaders can help sustain long-term campaign efforts because these leaders have built-in credibility and longevity in their communities. Campaigns can also utilize messengers from existing groups with an infrastructure around them, such as Boys and Girls Clubs that partner youths with adults. Campaigns need to allow these messengers to tailor campaign messages in the manner the messengers think will be the most effective in their communities.

· Influencers. Campaigns may use macro-influencers or micro-influencers to reach the intended audience. Macro-influencers, such as celebrities, have millions of followers and can be helpful for promoting awareness. Micro-influencers are niche but have closer connections with particular groups. Campaigns need to vet influencers thoroughly to make sure they do not post or sponsor conflicting or controversial content that will distract from the campaign’s message.

· Youths. Campaigns may use young people to deliver messages to their peers, including youths who participated in developing campaign messages. Experts noted that youth leaders need to be able to reach and be taken seriously by their peers.

Types of Media and Delivery Methods

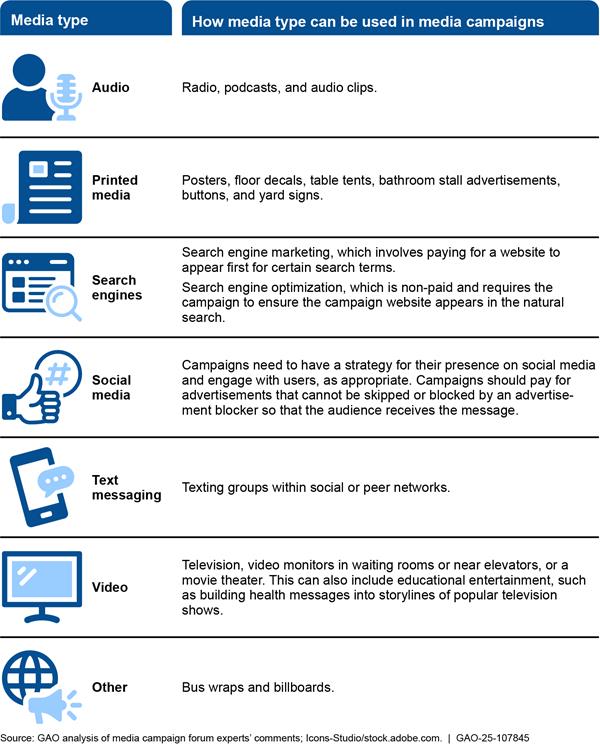

Campaigns need to decide how they will deliver their messages to the intended audience. Forum experts mentioned various types of media and delivery methods that campaigns may consider using, as shown in figure 1 below.

Note: The figure represents examples of the types of media that forum experts discussed. It is not an exhaustive list of all types of media that can be used to deliver media campaign messages.

Delivery Methods Used to Reach the Intended Audience

· Cross-platform. Campaigns may decide to combine two or more of the types of media described above to ensure the intended audience receives campaign messages repeatedly in a specific environment. For example, one expert told us about a campaign for youth that used a combination of media in schools, including posters, floor decals, table tents, buttons, morning news announcements, and yard signs, among others.

Similarly, experts told us campaigns need to be active across platforms when sharing their messages. For example, people may watch videos on television or YouTube, and campaigns need to be on both these platforms to increase their reach. Experts told us campaigns can no longer use just mass or local media channels to reach their audience; now they need to reach niche communities online through methods such as podcasts, social media, and peer groups. Experts noted that campaigns can repurpose some of the content they create across various platforms. For example, video content can be used in television, streaming services, and YouTube, and the corresponding audio can be used for radio and podcast advertisements.

· Repeated exposure. Campaigns need to expose the intended audience to their messages frequently. Sustaining the engagement of the intended audience is challenging and expensive, and campaigns need to reach audiences where they are and when they are ready. Campaigns may consider developing a series of messages that returns to the intended audience at various times because audiences cycle through periods when they are willing to change their behavior or hear campaign messages. Campaigns can use available national data that measure media audiences, such as Nielsen Media Research, to identify where audiences are going for information so that campaigns can reach them in the right place.

However, experts warned that over-exposure to campaign messages could have the opposite of the intended effect or unintentionally shift social norms around an issue. For example, one expert explained how a youth anti-drug media campaign contributed to an increase in youth interest in that drug because repeated exposure to the campaign message led youth to believe that their peers’ use of that drug was more prevalent than it was. To mitigate such perceptions, one expert indicated that a campaign could share positive facts about the issue in their messages, including that most youths are not misusing drugs.

· Paid vs. earned media. Experts said that campaigns can use paid media to drive awareness and earned media to reinforce messages and activate communities. Paid media involves the campaign paying for its advertising across different media platforms to reach the people around the intended audience, which can be impactful.[20] Earned media involves generating public exposure through social media mentions or unpaid news media coverage resulting from the campaign’s content, which can activate communities. Campaigns need to work with organizations to share the campaigns’ resources with the intended audience through earned media.

· Timing. Campaigns need to consider when to reach the intended audience using their selected media types. For example, campaigns may use geolocation or geofencing to target the intended audience in real-time. This could include targeting advertisements for cell phone users in specific locations within a region, such as grocery stores or pharmacies. Campaigns can also use daily routines to target the intended audience when the message may be most appropriate. For example, one expert described a campaign for bowel cancer screening that used radio advertisements in the morning to get the audience thinking about when to use their screening kits that day.

Other Factors to Consider

Forum experts told us campaigns need to consider other factors when choosing how to deliver their messages to the intended audience. For example:

· Funding. Campaigns need funding to buy media time and space, and because they typically have limited funds, need to use their funding wisely.[21] For example, using macro-influencers such as celebrities to deliver messages may reach more people, but it will cost campaigns more than micro-influencers, who may be more impactful with the intended audience. Campaigns also need to consider common themes that resonate across broad audiences and leverage more expensive media, such as television advertisements, to deliver those messages. Meanwhile, they need to segment messages across less expensive media, such as posters and radio, for specific groups. To supplement available funding, campaigns may consider partnering with a prominent organization, such as a professional sports team or league.

One example of a successful campaign that leveraged television and radio that experts discussed was the Legacy Foundation’s “truth” campaign, which was a nationwide smoking prevention campaign that spent its funding at the highest levels from 2000 to 2004.[22] This campaign used its available funds to both deliver its public education messages nationally and to support grassroots-level research and associated activities, which allowed it to reach different audiences.[23]

· Appropriateness. Campaigns need to meet the intended audience where they are by using appropriate platforms, images and language for the communities they want to reach. For example, one expert suggested using radio to reach low-technology and low-literacy communities. Similarly, if using social media, campaigns need to target the platforms that the intended audience uses. Experts noted that some messages will work well in some places but not everywhere.

· Campaign phase. Campaigns need to deliver messages differently throughout the course of a campaign. In the early stages when the campaign is focused on broad awareness, campaigns may consider using videos to explain their messages. Later, when some of the intended audience is already interested, the campaign can use social media, search engine optimization, or share links to direct the audience to resources they can use to take action.

· Balancing campaign roles. Campaigns need to carefully balance and encourage close relationships among various campaign roles when designing and delivering messages. These roles include the subject matter experts, researchers, creatives and advertisers, and evaluators. Collaboration among these roles will help ensure the campaign uses delivery methods that work best for the campaign. Similarly, campaigns need to give some control to the local communities they work with, such as allowing community leaders to influence the intended audience using their own voices. Community leaders know what is best for their communities.

Campaigns Need to Test Messages Before Deploying Campaigns

Forum experts said that campaigns may fail if they do not test their campaign messages with the intended audience, including within audience segments, before deploying the campaign.[24] Testing helps ensure that the messages are culturally relevant, resonate with the intended audience, and are responsive to the intended audience. Experts described various aspects of testing:

· Formative research. Formative research, conducted in the early stages of a campaign’s development, can help a campaign ensure it has a clear, consistent, relevant, credible messages delivered to make a difference. Campaigns may use, for example, rapid ethnographic methods to quickly understand an audience’s knowledge, beliefs, perceptions, and behaviors from their perspective. Rapid ethnographic methods include observation, interviews, and contextual inquiry conducted in a short amount of time. This can generate in-depth data to improve campaign development and delivery.

· Data sources. To inform message development, campaigns need to use multiple data sources to determine what people want from the campaign and what is going to work. This can include testing data from focus groups, interviews with partners, workshops, surveys, social media conversations, listening sessions, and digital testing. Campaigns need to consider how social and peer influence can affect testing results and may need to interview people one-on-one to avoid such influence. Additionally, campaigns can test for the perceived effectiveness of their messages through surveys. Perceived effectiveness is the audience’s perception of a persuasive campaign message on their knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors, according to one expert. It is concerned with perceptions of likely message effectiveness and campaign success. For example, a campaign may measure perceived effectiveness by asking people to indicate if a campaign message is memorable, interesting, meaningful, and how effective it is at persuading them to engage in a behavior or talk to others about engaging in a behavior.

· Testing message themes. Campaigns need to test their message themes, or concepts, prior to testing the actual messages they plan to use. One expert stated that a campaign could test message themes by conducting a cross-sectional survey of the intended audience. An example of a message theme is the negative cosmetic outcomes from smoking for a smoking prevention campaign.

Considerations for Evaluating Media Campaigns

The 12 forum experts discussed how campaign evaluations can provide important information about the effectiveness of campaigns. Before campaigns can be evaluated, they need to (1) define the intended outcome, (2) select qualified evaluators, and (3) decide when and how to measure effectiveness.

Campaigns Need to Define the Intended Outcome

Forum experts explained that to measure effectiveness, a campaign needs a clear understanding of what it is trying to achieve or its intended outcome. Once a campaign has defined its goals or objectives, evaluators can decide what data would demonstrate whether the campaign has met or is making progress toward meeting them. For example, if a campaign is trying to get people to take a particular action, such as reducing drug misuse, it would evaluate if the intended audience took that action.

Forum experts said that evaluators need to keep in mind that it is difficult for a campaign to get people’s attention, and campaigns should not be expected to change behavior quickly because behavior change is a long-term process. In addition, it is difficult to prove that a campaign contributed to sustained behavior change, especially in the context of addictive behaviors such as drug misuse. They may choose instead to measure people’s behavioral intent to change their drug misuse rather than measuring actual sustained behavior change. Alternatively, they may choose to measure progress toward the ultimate behavior change, such as misusing drugs less frequently.

Campaigns Need to Select Qualified Evaluators

Forum experts told us that certain qualifications are essential for individuals selected to evaluate campaigns. Two key qualifications are independence and experience:

· Independence. Campaigns need independent evaluators who can speak to campaign managers about a campaign’s effectiveness using evidence from evaluations.[25] Managers are invested in the campaign’s success and therefore desire to receive evidence that the campaign is working. Advertisers also have an interest in demonstrating to managers that the campaign is successful.

Independence does not mean that evaluators need to be entirely separated from managers and advertisers. The evaluator having some relationship with the managers can be beneficial to help the evaluator understand what the campaign is trying to achieve. That close working relationship also allows the evaluator to provide evidence throughout the campaign regarding what is or is not working. To maintain independence, the evaluator can report to someone other than whoever is funding the campaign.

· Experience. Evaluators also need expertise in research methods, evaluation, and other disciplines. For example, evaluators need to understand communications, including key concepts such as exposure. The field of campaign evaluation is multidisciplinary, and evaluators may have degrees in a variety of disciplines including political science, sociology, psychology, business, communication, or other fields.

Evaluators need to understand the substance of the campaign. For example, someone evaluating an anti-drug campaign needs to understand drug misuse. In addition, evaluators need to understand the broader policy and sociocultural context the behaviors of interest are occurring within because these other systemic factors could drive change in the behavior, rather than the campaign. Evaluators need to consider all the other potential influences on that behavior occurring at the same time to be able to attribute any change to the campaign.

Campaigns Need to Decide When to Measure Effectiveness

Forum experts described two types of evaluations that are characterized by when they occur during a campaign:

· Process evaluations. Process evaluations are continuous evaluations conducted during the course of a campaign allowing for mid-course corrections, if needed. The interim data from these evaluations can provide valuable information to help make decisions about the campaign. This real-time data collection also allows campaigns to be flexible if the environment surrounding the issue changes and to be responsive to changes in cultural trends. However, this type of evaluation should only be done if the campaign is ready to use the data effectively, according to forum experts. For example, one expert described an anti-drug campaign that convened focus groups with youth and found that while many of the youth acknowledged using marijuana, few would acknowledge any negative consequences. However, many responded that their friends’ marijuana use had negative impacts, such as disappointing friends and families. As a result, the campaign developed and tested new messages featuring youth showing concern about their friends’ use and the harm it was causing to relationships.

· Summative evaluations. Summative evaluations occur after a campaign has ended, providing an overall picture of the campaign. These evaluations can measure long-term changes in behavior or beliefs and determine whether the campaign met its goal. These evaluations can also help inform subsequent campaigns. However, because summative evaluations occur after a campaign ends, they cannot help inform or improve the campaign being evaluated.

Campaigns Need to Decide How to Measure Effectiveness

Forum experts told us that when deciding how to measure a campaign’s effectiveness, evaluators need to consider several factors and select which variables to measure and what methods they will use to collect data about the campaign’s effectiveness.

Factors to Consider

Forum experts said that when evaluating campaigns for effectiveness, evaluators need to consider the following factors:

· Campaign goals. Campaigns need to think from the beginning about how they will evaluate whether they have achieved their goals. Therefore, having a logic model is the first step in developing a campaign, according to experts. A logic model will articulate the inputs, outputs, and what the campaign is trying to do over time. To measure behavior change at the population level, campaigns first need to achieve extensive exposure to the campaign messages across the population over time. This process is slow and long term. Therefore, evaluators need to think about short-, mid-, and long-term outcomes they can measure and build them into the logic model.

· Environmental influences. Campaigns do not exist in a vacuum; they need to consider environmental influences because external variables may influence the behavior that is the focus of the campaign. For campaigns that span many years, a multitude of policy and other changes at the state and national levels could affect the behavior of interest. For example, marijuana legalization in some states may affect the prevalence of marijuana use in those states. There are also often competing and contradictory messages surrounding a campaign that result in mixed messages. For example, a youth anti-alcohol or anti-drug campaign may be conflicting for children who see their parents consume alcohol or use marijuana. Paid alcohol placements in media can also dilute anti-alcohol campaigns.

· Challenges in media. People are exposed to more media today than ever before, which can make reaching people challenging. Campaigns need to be aware that even if they implement a campaign based on the best available evidence, it still may not work as intended, but they may be able to collect other useful information and learn from it.

· Funding. Campaigns need to have funding available to conduct robust evaluations. For example, one expert said the Legacy Foundation’s early 2000s nationwide smoking prevention campaign described previously, was demonstrated successful through a well-funded campaign evaluation.[26]

Variables to Measure

Forum experts told us that evaluators also need to choose what variables they want to measure. These will be the outcomes in the logic model. The selection of variables will depend on what data are possible to collect and the purpose of the campaign. Examples of the variables a campaign may choose to measure include the following:

· Exposure. Exposure data indicate how many people the campaign has reached. This is important because a campaign cannot be effective if people have not been exposed to it, but exposure data are not sufficient for a full evaluation.

· Recall. Recall refers to the intended audience’s ability to remember and recognize a campaign’s message when asked. Evaluators can measure unaided recall by asking the audience generally about what messages they have seen, or aided recall, by asking the audience if they have seen a specific campaign message.

· Perceived effectiveness. As stated previously, perceived effectiveness is the audience’s perception of a persuasive campaign message on their knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors.

· Social norms. Social norms are people’s perceptions of how acceptable a behavior is.

· Behavior determinants. Behavior determinants are variables that may be correlated with changes in behavior, such as shifts in knowledge, changes in attitudes, and intention to change. Depending on how complex the targeted behavior is and how difficult it is to measure, these intermediate steps before behavior change may be the closest an evaluator can get to measuring actual behavior change.

· Behavior change. It may be possible to measure the actual behavior the campaign is intended to change. However, often there is no “ultimate” behavior for recurring, chronic conditions. Behaviors may improve, then decline repeatedly. Another option is to measure micro-behaviors, such as quit attempts or a reduction in the use or misuse of addictive substances.

Methods to Collect Data

Finally, forum experts stated that evaluators need to choose what data collection methods to use to measure their selected variables. A campaign needs to look at all the available data sources and triangulate across them.[27] Some options include:

· Media metrics. Collecting media metrics can help evaluate awareness or how well the campaign is reaching people. Examples include social media views, website clicks, and QR code use. These metrics are generally readily available to campaigns. However, media metrics are sometimes collected through algorithms into which the evaluator does not have visibility.

· Surveys. Surveys can be useful to measure recall, perceived relevance, believability, intention to change, and behavior change. However, surveys may over-estimate exposure because people might claim they recall something during a survey just to be nice. Evaluators can counter this by surveying pre- and post-campaign or asking about ads that do not exist (i.e., dummy ads) to gauge false positives. Survey results may also over-estimate behavior change or intention to change because they contain self-reported data.

· Existing population data. Some campaigns may have access to state or national-level data collected by others (for example, the National Survey on Drug Use and Health). These data can provide valuable information about the prevalence of certain behaviors or beliefs in the general population. However, the timing of these surveys may not align with campaigns, and the same data need to be collected over years for the data to be useful. Campaigns may also need specific information that is not already collected by these surveys. Campaigns can try to have their questions added to an existing survey, but this is challenging due to testing requirements and timing.

· Direct observations. Directly observing behavior changes may be useful for longer-term outcome evaluations. For example, one expert described using wastewater surveillance to measure the prevalence of drugs in certain areas.

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to the Departments of Health and Human Services and Justice and ONDCP for review and comment. They did not have any comments on the report.

I wish to thank all the experts for their thoughtful contributions to our discussion of media campaigns. The discussion enhanced our understanding and provided valuable insight on this important issue.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Attorney General, the Director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy, the Secretary of Health and Human Services, and other interested parties. In addition, this report is available at no charge on the GAO website at www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at McNeilT@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix III.

Triana McNeil,

Director, Homeland Security and Justice

List of Committees

The Honorable Bill Cassidy, M.D.

Chair

The Honorable Bernard Sanders

Ranking Member

Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions

United States Senate

The Honorable Rand Paul, M.D.

Chairman

The Honorable Gary C. Peters

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable Charles E. Grassley

Chairman

The Honorable Richard J. Durbin

Ranking Member

Committee on the Judiciary

United States Senate

The Honorable Bill Hagerty

Chair

The Honorable Jack Reed

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Financial Services and General Government

Committee on Appropriations

United States Senate

The Honorable Brett Guthrie

Chairman

The Honorable Frank Pallone, Jr.

Ranking Member

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

The Honorable Jim Jordan

Chair

The Honorable Jamie Raskin

Ranking Member

Committee on the Judiciary

House of Representatives

The Honorable James Comer

Chairman

The Honorable Robert Garcia

Ranking Member

Committee on Oversight and Government Reform

House of Representatives

The Honorable Dave Joyce

Chairman

The Honorable Steny Hoyer

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Financial Services and General Government

Committee on Appropriations

House of Representatives

This report answers the following research questions:

1. What campaigns did the Office of National Drug Control Policy’s (ONDCP) National Anti-Drug Media Campaign conduct from fiscal year 2018 through April 2025?

2. What are experts’ views on how to develop an effective media campaign?

3. What are experts’ views on how to evaluate media campaigns?

To answer our first objective question, we interviewed ONDCP officials about media campaigns ONDCP has conducted over the past 10 years and reviewed ONDCP documentation about these campaigns. We also reviewed ONDCP’s Congressional Budget Submission for Fiscal Year 2026.[28] In addition, we reviewed prior GAO reports that included information about ONDCP’s media campaigns. [29]

To answer our second and third objective questions, we conducted a literature review, selected experts, convened a virtual discussion forum, and performed a content analysis of the forum discussion.

Topic research. We conducted a literature review to inform discussion topics and questions for the forum and completed an initial literature search based on our research objectives. We conducted these searches in databases with scholarly articles and government articles, including EBSCOhost Databases, Harvard Think Tank Search, Policy File, and Scopus. A team member reviewed the abstracts compiled from the literature search and selected articles for inclusion that were published within a 10-year period (2014 through 2024). Additionally, the articles selected for inclusion met any of the following criteria: (1) provide examples or case studies of successful or unsuccessful public media campaigns, (2) describe lessons learned or good practices for conducting public media campaigns, (3) evaluate a public media campaign, (4) describe criteria or assessment mechanisms to evaluate public media campaigns, or (5) describe issues that could be lessons learned or good practices for evaluating public media campaigns. A second team member confirmed the determination to include or exclude articles.

Following the abstract screening, team members reviewed the full text of each article and determined whether the articles were relevant. Team members next identified characteristics that could be leading practices and practices to avoid when conducting and evaluating media campaigns. A research methodologist reviewed the relevant articles to determine whether they were methodologically sound and sufficient for our purposes. Using information gained from the relevant articles, we developed a moderator guide with discussion questions for the forum.

Expert selection. We contracted with the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) to identify subject matter experts knowledgeable in both (1) developing public media campaigns, including those intended to prevent drug misuse and other behaviors such as tobacco use or gambling, among others, and (2) evaluating media campaign effectiveness. NASEM identified an initial set of experts to invite to a virtual discussion forum. The criteria for selecting experts for this initial list included but was not limited to: (1) the type and depth of relevant experience, (2) recognition in the professional community and relevance of any published work, (3) employment history and professional affiliations, and (4) other relevant experts’ recommendations. GAO was responsible for all final decisions regarding discussion topics and expert participation.

We also interviewed officials from the Office of National Drug Control Policy, the Drug Enforcement Administration, and the Department of Health and Human Service’s Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration to learn about campaigns they have conducted to prevent drug misuse. We also asked these agency officials to recommend experts for our forum.

Using the initial list provided by NASEM and the recommendations of the agencies we interviewed, we selected a list of experts to invite to the forum. These experts represented a range of experiences in conducting and evaluating media campaigns in academia, and were from federal and state governments; and communications, consulting, and nonprofit organizations. Our final group of experts that agreed to participate in the forum included 12 such experts. See appendix II for a list of the forum experts.

Comptroller General forum. The discussion forum was a 1-day event conducted virtually on February 11, 2025. In addition to the Comptroller General of the United States, two GAO officials participated as moderators. The forum was structured as a guided discussion where experts were encouraged to openly comment on issues and respond to one another, but not all experts commented on all topics. GAO contracted with a professional court reporting service to ensure we accurately captured a transcript of the forum proceedings.

The forum was divided into three sessions, each 90 minutes in duration. The topics of discussion for these sessions were as follows:

· key elements of an effective media campaign and intended audiences

· modes of dissemination for media campaigns and characteristics of campaigns’ messages and messengers

· evaluation of media campaigns, including data collection and evaluation methods

Content analysis and forum summary report. To summarize the discussions held during the forum, we reviewed a transcript of the proceedings and developed a process to analyze and thematically summarize the content of the forum. Two analysts developed an initial list of thematic categories and then refined these categories iteratively to develop a final list. These two analysts then jointly reviewed the transcript and organized experts’ statements using these thematic categories, which formed the basis for this summary report.

While this report summarizes the key ideas that emerged during the forum, it is not intended to present an exhaustive catalogue of all ideas discussed by experts nor to represent all perspectives.[30] In addition, the information presented in this summary does not necessarily represent the views of all experts, the views of their organizations, or the views of GAO. We provided a draft of this report to the forum experts to ensure we captured their discussion accurately and incorporated their comments as appropriate.

We conducted this performance audit from September 2024 to July 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

|

Linda Bergonzi-King |

Health Communication Strategist and Media Producer, TriBella Productions; and Workplace Violence Prevention Coordinator, Yale New Haven Health System |

|

Amelia Burke-Garcia |

Director, Center for Health Communication Science and Program Area Director, Digital Strategy and Outreach, NORC at the University of Chicago |

|

Robert Denniston |

Former Director, Media Campaigns, Office of National Drug Control Policy |

|

Sarah Durkin |

Director, Cancer Council Victoria; and Principal Research Fellow, University of Melbourne |

|

Cheryl Healton |

Professor, Public Health Policy and Management; and Founding Dean, School of Public Health, New York University |

|

Robert C. Hornik |

Wilbur Schramm Professor Emeritus of Communication and Health Policy, Annenberg School for Communication, University of Pennsylvania |

|

Ashani Johnson-Turbes |

Vice President, The Bridge, NORC at the University of Chicago |

|

Jim Kooler |

Special Consultant, Center for Healthy Communities, California Department of Public Health |

|

Emma Maceda-Maria |

Program Manager, Grupo Asesor Latino |

|

Lora Peppard |

Executive Director, Center for Advancing Prevention Excellence, University of Baltimore; and Deputy Director, Treatment and Prevention, Washington/Baltimore High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area |

|

Maria Elena Villar |

Professor and Chair, Department of Communication Studies, Northeastern University |

|

Jay Winsten |

Former Associate Dean and Founding Frank Stanton Director, Center for Health Communication, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health |

GAO Contact

Triana McNeil, McNeilT@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, the following staff made key contributions to this report: Julia Vieweg (Assistant Director), Stephanie Heiken (Analyst in Charge), Ryan Basen, Colleen Candrl, Billy Commons, Eric Hauswirth, Amanda Miller, Rebecca Sero, Walter Vance, and Kelsey Wilson.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]Drug misuse is defined as the use of illicit drugs and the misuse of prescription drugs. Every two years at the start of a new Congress, GAO calls attention to agencies and program areas that are high risk due to their vulnerabilities to fraud, waste, abuse, and mismanagement, or are most in need of transformation. In March 2019, we named drug misuse as an emerging issue requiring close attention. In March 2020, we determined that national efforts to prevent, respond to, and recover from drug misuse were high risk. We issued the most recent update to the High-Risk List in February 2025. See GAO, High-Risk Series: Heightened Attention Could Save Billions More and Improve Government Efficiency and Effectiveness, GAO‑25‑107743 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 25, 2025). In addition, GAO has issued work on drug misuse. See GAO, Combatting Illicit Drugs: Improvements Needed for Coordinating Federal Investigations, GAO‑25‑107839 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 5, 2025); Opioid Use Disorder Grants: Opportunities Exist to Improve Data Collection, Share Information, and Ease Reporting Burden, GAO‑25‑106944 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 17, 2024); Health Care Capsule: Treatment for Drug Misuse, GAO‑25‑107640 (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 3, 2024); Substance Misuse Treatment and Recovery: Federal Guidance Needs to Address Work Arrangements for Those Living in Residential Facilities, GAO‑24‑106101 (Washington, D.C.: July 8, 2024).

[2]21 U.S.C. § 1702(a)(1)-(2).

[3]21 U.S.C. § 1708(f).

[4]Pub. L. No. 115-271, § 8220, 132 Stat. 3894, 4134 (codified at 21 U.S.C. § 1715).

[5]See GAO, ONDCP Media Campaign: Contractor’s National Evaluation Did Not Find that the Youth Anti-Drug Media Campaign Was Effective in Reducing Youth Drug Use, GAO‑06‑818 (Washington, D.C.: Aug. 25, 2006); Drug Control: Office of National Drug Control Policy Met Some Strategy Requirements but Needs a Performance Evaluation Plan, GAO‑23‑105508 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 19, 2022).

[6]There was general consensus among experts on the themes that emerged from the collective discussion. When we refer to “forum experts” in this report, we are referring to consensus among all 12 unless otherwise stated.

[7]21 U.S.C. § 1703(b)(2), (c)(2)(A).

[8]21 U.S.C. §§ 1531 and 1706.

[9]We have an ongoing review of the Drug-Free Communities Support Program. We expect to issue a report in fiscal year 2025.

[11]See GAO‑06‑818 and GAO‑23‑105508.

[12]No-year funds remain available for an indefinite period and can therefore be carried over into future years. Recoveries occur when a prior year obligation is reduced or canceled. Pursuant to 21 U.S.C. § 1708(f)(2)(B)(iv), ONDCP is required to designate an independent entity to evaluate the effectiveness of its media campaigns. As such, we did not independently evaluate these campaigns.

[13]This campaign cost $498,000, according to ONDCP officials.

[14]This campaign cost $500,000 in fiscal year 2022 and an additional $2.1 million during fiscal years 2023 through 2024, according to ONDCP officials. “The Real Deal on Fentanyl,” accessed June 11, 2025, https://realdealonfentanyl.com.

[15]Executive Office of the President of the United States, Congressional Budget Submission: Office of National Drug Control Policy Fiscal Year 2026, (Washington, D.C.: May 2025).

[16]Executive Office of the President of the United States, Congressional Budget Submission.

[17]Pursuant to 21 U.S.C. § 1708(e), upon designation of an emerging drug threat, the Director of ONDCP is to evaluate whether a media campaign would be appropriate to address that threat. In March 2022, Congress declared methamphetamine an emerging drug threat under the Methamphetamine Response Act of 2021, Pub. L. No. 117-99, § 2, 136 Stat. 43 (2022). We previously reported that in November 2022, ONDCP officials told us that they would not consider undertaking a new media campaign focused on an emerging drug threat without dedicated funding. See GAO‑23‑105508. Further, on April 12, 2023, the then-Director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy designated fentanyl adulterated or associated with xylazine as an emerging drug threat. In response, ONDCP coordinated and released a government-wide response plan in the summer of 2023, outlining high priority actions needed. As part of this effort, the CDC created dedicated social media posts and graphics around xylazine and integrated xylazine messaging into its existing campaign efforts related to overdose, including in its web content and other events and activities.

[18]From this point forward, we use the term “intended audience” to refer to who the campaign wants to reach generally. This may include the campaign’s identified primary and secondary intended audiences or the general public.

[19]Pursuant to 21 U.S.C. § 1708(f)(5)(C)-(D), generally, none of the funds made available for the ONDCP National Anti-Drug Media Campaign may be obligated or expended for partisan political purposes, or to express advocacy in support of or to defeat any clearly identified candidate, clearly identified ballot initiative, or clearly identified legislative or regulatory proposal or fund advertising that features any elected officials, persons seeking elected office, cabinet level officials, or certain other federal officials.

[20]For the ONDCP National Anti-Drug Media Campaign, 21 U.S.C. § 1708(f)(2) outlines the allowable uses of funds, such as for the purchase of media time and space, including the strategic planning for, tracking, and accounting of such purchases; advertising production costs, which may include television, radio, internet, social media, and other commercial marketing venues; testing and evaluation of advertising; and evaluation of the effectiveness of the national media campaign.

[21]Pursuant to 21 U.S.C. § 1708(f)(2)(A)(i), funds made available to carry out the ONDCP National Anti-Drug Media Campaign may be used for the purchase of media time and space. While funds made available to carry out the ONDCP National Anti-Drug Media Campaign may be used for creative and talent costs under 21 U.S.C. § 1708(f)(2)(A)(ii), in using amounts for these creative and talent costs, the Director of ONDCP is required to use creative services donated at no cost to the government whenever feasible and may only procure creative services for advertising when responding to high-priority or emergent campaign needs that cannot timely be obtained at no cost or intended to reach a minority, ethnic, or other special audience that cannot reasonably be obtained at no cost pursuant to 21 U.S.C. § 1708(f)(2)(B)(i).

[22]Legacy Foundation is now called Truth Initiative.

[23]Forum experts described this campaign as successful. We did not conduct an independent review to evaluate its effectiveness.

[24]For the ONDCP National Anti-Drug Media Campaign, pursuant to 21 U.S.C. § 1708(f)(2)(A)(iv), funds made available for the national media campaign may be used for testing and evaluation of advertising. In using funds for testing and evaluation of this advertising, generally, the Director of ONDCP is required to test all advertisements prior to use in the national media campaign to ensure that the advertisements are effective with the target audience and meet industry-accepted standards under 21 U.S.C. § 1708(f)(2)(B)(ii).

[25]Pursuant to 21 U.S.C. § 1708(f)(2)(A)(v), funds made available to carry out the ONDCP Anti-Drug Media Campaign may be used for the evaluation of the effectiveness of the national media campaign. Pursuant to 21 U.S.C. § 1708(f)(2)(B)(iv), in using funds for the evaluation of the effectiveness of the national media campaign, the Director of ONDCP is required to designate an independent entity to evaluate by April 20 of each year the effectiveness of the national media campaign based on certain specified data and ensure that the effectiveness of the national media campaign is evaluated in a manner that enables consideration of whether the national media campaign has contributed to changes in attitude or behaviors among the target audiences with respect to substance use and such other measures of evaluation as the Director determines are appropriate.

[26]Forum experts described this campaign as successful. We did not conduct an independent review to evaluate its effectiveness.

[27]Pursuant to 21 U.S.C. § 1708(f)(2)(B)(iv), in using funds to evaluate the effectiveness of the national media campaign, the Director of ONDCP is required to designate an independent entity to evaluate by April 20 of each year the effectiveness of the national media campaign based on data from the Monitoring the Future Study published by the Department of Health and Human Services; the National Survey on Drug Use and Health; and other relevant studies or publications, as determined by the Director, including tracking and evaluation data collected according to marketing and advertising industry standards.

[28]Executive Office of the President of the United States, Congressional Budget Submission: Office of National Drug Control Policy Fiscal Year 2026 (Washington, D.C.: May 2025).

[29]See GAO, ONDCP Media Campaign: Contractor’s National Evaluation Did Not Find that the Youth Anti-Drug Media Campaign Was Effective in Reducing Youth Drug Use, GAO‑06‑818 (Washington, D.C.: Aug. 25, 2006); Drug Control: Office of National Drug Control Policy Met Some Strategy Requirements but Needs a Performance Evaluation Plan, GAO‑23‑105508 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 19, 2022).

[30]There was general consensus among experts on the themes that emerged from the collective discussion. When we refer to “forum experts” in this report, we are referring to consensus among all 12 unless otherwise stated.