HIGH-RISK SERIES

Critical Actions Needed to Urgently Address IT Acquisition and Management

Challenges

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Carol C. Harris at (202) 512-4456 or harriscc@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107852, a report to congressional committees

Critical Actions Needed to Urgently Address IT Acquisition and Management Challenges

Why GAO Did This Study

Federal agencies rely extensively on IT to carry out operations and fulfill their missions. Each year, the federal government invests more than $100 billion on IT. However, for several decades, GAO has reported that federal IT investments too frequently fail or incur cost overruns and schedule slippages while contributing little to mission-related outcomes. Because of these challenges, GAO added the federal government’s management of IT acquisitions and operations to its high-risk list as a government-wide challenge in 2015 and continues to designate it as a high-risk area.

Over time, this high-risk area has become increasingly more complex as technologies have matured and evolved. In addition, as technologies have changed, the skills needed to manage them have also changed.

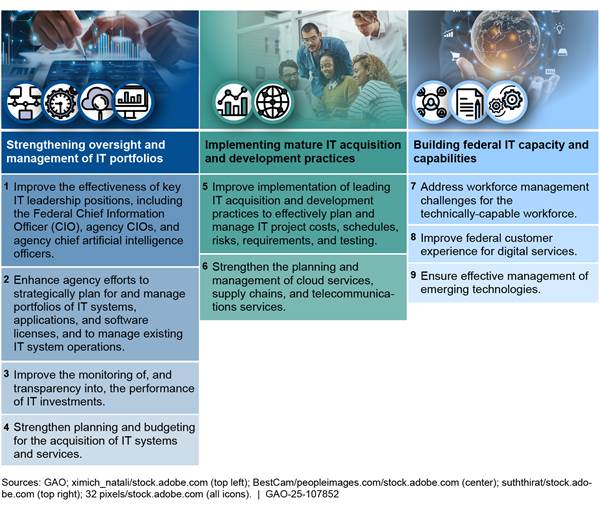

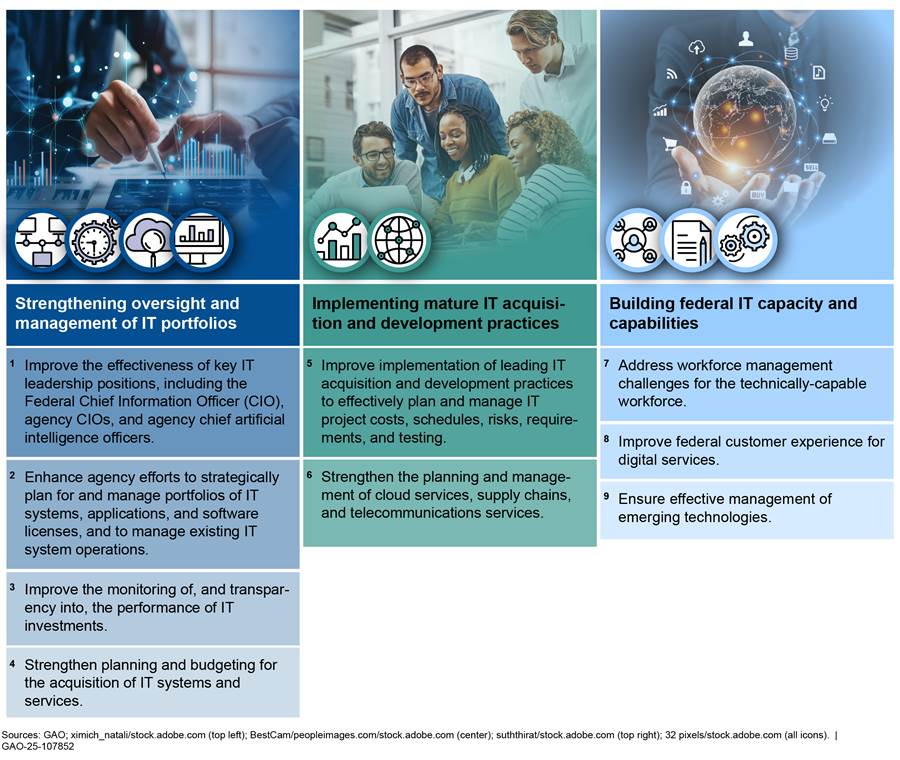

This report provides an update to the IT acquisitions and operations high-risk area. To do so, GAO identified three key IT acquisition and management areas in which federal agencies face continued challenges and nine critical actions that the agencies need to take to address those challenges. GAO reviewed its prior reports and prioritized reports that were government-wide and had open recommendations, among other things. Based on the results of its work, GAO is renaming this high-risk area to Improving IT Acquisitions and Management.

What GAO Recommends

GAO has made over 1,800 recommendations to agencies aimed at improving their management of IT since 2010. As of January 2025, 463 had not been implemented.

What GAO Found

GAO has identified three major IT acquisition and management challenges: (1) strengthening oversight and management of IT portfolios, (2) implementing mature IT acquisition and development practices, and (3) building federal IT capacity and capabilities. To address these challenges, it has identified nine critical actions that the federal government urgently needs to take.

GAO has made over 1,800 recommendations to the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and federal agencies aimed at improving their management of IT. However, many of these recommendations have not been implemented and many agencies continue to be challenged in effectively acquiring IT and managing IT projects. Of the 1,881 recommendations made since 2010 related to this high-risk area, 463 had not been implemented as of January 2025. GAO has also designated 69 as priority recommendations and, as of January 2025, 32 had not been implemented. Urgent actions are needed to address the ongoing challenges that the government faces in effective and efficient IT acquisition and management. Until OMB and federal agencies take the critical actions identified, they will continue to struggle with IT acquisitions that fail to consistently deliver capabilities in a timely manner, incur cost overruns and/or schedule slippages, and contribute little to mission-related outcomes.

Abbreviations

|

21st Century IDEA |

21st Century Integrated Digital Experience Act |

|

AI |

artificial intelligence |

|

ATC |

air traffic control |

|

CFO |

chief financial officer |

|

CIO |

chief information officer |

|

DHS |

Department of Homeland Security |

|

DOD |

Department of Defense |

|

DOT |

Department of Transportation |

|

EIS |

Enterprise Infrastructure Solutions |

|

FAA |

Federal Aviation Administration |

|

FAFSA |

Free Application for Federal Student Aid |

|

FITARA |

Federal IT Acquisition Reform Act |

|

FPAC |

Farm Production and Conservation |

|

FRTIB |

Federal Retirement Thrift Investment Board |

|

GSA |

General Services Administration |

|

HART |

Homeland Advanced Recognition Technology |

|

HHS |

Department of Health and Human Services |

|

ICT |

information and communications technology |

|

IRS |

Internal Revenue Service |

|

NextGen |

Next Generation Air Transportation System |

|

NIH |

National Institutes of Health |

|

OMB |

Office of Management and Budget |

|

SBA |

Small Business Administration |

|

TSP |

Thrift Savings Plan |

|

UI |

unemployment insurance |

|

USDA |

U.S. Department of Agriculture |

|

USDS |

U.S. Digital Service |

|

VA |

Department of Veterans Affairs |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

January 23, 2025

The Honorable Rand Paul, M.D.

Chairman

The Honorable Gary C. Peters

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable James Comer

Chairman

The Honorable Gerald E. Connolly

Ranking Member

Committee on Oversight and Government Reform

House of Representatives

Federal agencies rely extensively on IT to carry out operations and meet their missions. As part of this, federal IT systems provide essential services that are critical to the health, economy, and defense of the nation. Each year, the federal government invests more than $100 billion on IT investments.

However, for several decades, we have reported that federal IT investments too frequently fail or incur cost overruns and schedule slippages while contributing little to mission-related outcomes. To improve the management of IT, Congress enacted the Federal IT Acquisition Reform Act (FITARA) in December 2014.[1] This act enables Congress to monitor covered agencies’ efforts to manage their IT acquisitions and hold them accountable for reducing duplication and achieving cost savings.[2]

In the decade since FITARA was passed, sustained congressional focus on the implementation of the act led to improvement in agencies’ efforts to acquire and manage IT. However, additional work is needed to institutionalize agency processes established in response to FITARA, as well as tackle remaining challenges that hamper efficient and effective acquisition and management of the government’s IT assets. Such challenges include a lack of disciplined and effective management in areas such as project planning, requirements definition, and program oversight.

Because of these longstanding challenges, we added the federal government’s management of IT acquisitions and operations to our high-risk list as a government-wide challenge in 2015.[3] Underscoring the significance of the issues agencies face in effectively acquiring and managing IT, we have continued to designate IT acquisitions and operations as a high-risk area in each of our high-risk series updates since then.[4]

Over time, this high-risk area has become increasingly more complex as technologies have matured and evolved. In addition, as technologies have changed, the skills needed to manage them have also changed. Further, critical government systems have continued to age and either become obsolete or extremely costly to maintain.

This report provides an update to the IT acquisitions and operations high-risk area by identifying actions that the federal government and other entities need to take to address IT acquisition and management challenges. To do so, this report reflects work we conducted since the prior high-risk update was issued in April 2023, among other things. We also plan to issue an updated assessment of this high-risk area in February 2025. Based on the results of our work and the three key challenges that we identified (discussed in more detail later), we are changing the name of this area from Improving the Management of IT Acquisitions and Operations to Improving IT Acquisitions and Management.

We performed this work on the initiative of the Comptroller General to identify and describe the key challenges that the federal government faces in effectively managing its IT acquisitions and the critical actions it needs to take to address those challenges.

To do so, we first analyzed the topics and open recommendations discussed in previous updates to the IT acquisitions and operations area in our high-risk reports. From these topics, we developed an initial list of critical actions that federal agencies need to take to improve their IT acquisitions and management. We then analyzed these critical actions and grouped them into key challenge areas.

To validate the accuracy and completeness of the identified challenge areas and critical actions, we solicited input from internal experts and stakeholders responsible for and involved in our previous and ongoing work assessing the Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) and federal agencies’ IT acquisition and management efforts. Based on these actions, we identified three key IT acquisition and management areas in which federal agencies face continued challenges and nine critical actions that the agencies need to take to address those challenges.

To identify related GAO reports for potential inclusion in this report, we identified all reports related to this high-risk area that have been issued since fiscal year 2010. In selecting reports for inclusion, we prioritized reports that met one or more of the following criteria: (1) were government-wide, (2) pertained to multiple agencies, (3) had open priority recommendation(s), or (4) had significant attention from Congress or the Comptroller General.[5] We also identified and selected ongoing engagements related to this high-risk area that planned to publicly release a product by December 2024 and met one or more of the previous criteria.

We validated the list of selected reports with internal experts and stakeholders. For the selected reports, we summarized the key findings and open recommendations.[6] We also identified our ongoing work related to each challenge area.

We conducted this work from September 2024 to January 2025 in accordance with all sections of GAO’s Quality Assurance Framework that are relevant to our objective. The framework requires that we plan and perform the engagement to obtain sufficient and appropriate evidence to meet our stated objective and to discuss any limitations in our work. We believe that the information and data obtained, and the analysis conducted, provide a reasonable basis for any findings and conclusions in this product.

Background

The federal government invests more than $100 billion on IT investments each year. A large majority of these investments are to support the operation and maintenance of existing IT systems—such as those that support tax filings, Census survey information, and veterans’ health records. These investments also support system development and activities, including software upgrades, replacement of legacy IT, and the adoption of new technologies.

Notwithstanding the billions of dollars spent annually, federal IT investments too frequently fail to deliver capabilities in a timely manner, incur cost overruns, and/or experience schedule slippages while contributing little to mission-related outcomes. These investments often lack disciplined and effective management in areas such as project planning, requirements definition, and program oversight and governance. In many instances, agencies have not consistently applied best practices that are critical to successfully acquiring IT investments. Federal IT projects have also failed due to a lack of oversight and governance. Executive-level governance and oversight across the government has often been ineffective, specifically from chief information officers (CIO).

Over the past two decades, the executive branch has undertaken multiple initiatives in an attempt to address the persistent issues with IT acquisitions and management. For example,

· In June 2009, OMB launched the IT Dashboard.[7] It is intended to provide transparency for IT investments to facilitate public monitoring of government operations and accountability for investment performance by the Federal CIO who oversees them.[8] Among other things, agencies are to submit CIO ratings for major investments. According to OMB’s instructions, these ratings should reflect the level of risk facing an investment relative to that investment’s ability to accomplish its goals.[9]

· In January 2010, OMB began conducting TechStat sessions. OMB envisioned these sessions as face-to-face, evidence-based reviews of an at-risk IT investment. The sessions were an effort to turnaround, halt, or terminate IT projects that were failing or not producing results. At the time, OMB used CIO ratings from the IT Dashboard, among other sources, to select at-risk investments for the TechStats. OMB conducted TechStats from 2010 through 2011 and subsequently required federal agencies to hold them, too.[10]

· In December 2010, the White House issued a 25-point plan intended to reform federal IT management.[11] Among other things, the document directed agencies to reform and strengthen their investment review boards and begin holding TechStats at the department and bureau levels.

· In March 2012, recognizing the proliferation of duplicative and low-priority IT investments within the federal government and the need to drive efficiency, OMB launched the PortfolioStat initiative.[12] This required agency CIOs to conduct annual agency-wide reviews of their IT portfolios to, among other things, assess the current maturity of their IT portfolio management processes, reduce duplication, demonstrate how investments align with the agencies’ missions, and achieve savings by identifying opportunities to consolidate investments or move to shared services.

· In 2014, the General Services Administration (GSA) established 18F, a team that provides IT services (e.g., develop websites and provide software development training) to federal agencies on a reimbursable basis. Also in 2014, the President established the U.S. Digital Service within OMB. Similar to 18F, the U.S. Digital Service aims to improve the most important public-facing federal digital services.[13]

Despite these initiatives aimed at improving federal IT, implementation has been inconsistent and significant issues persisted. Recognizing the severity of these issues, in December 2014, Congress enacted federal IT acquisition reform legislation, commonly referred to as FITARA.[14] This act enables Congress to monitor covered agencies’ efforts and hold them accountable for reducing duplication and achieving cost savings. Among other things, the act strengthens the authority of CIOs to provide needed direction and oversight of covered agencies’ IT acquisitions.[15] In June 2015, OMB released guidance describing how agencies are to implement the act.[16] The guidance emphasized the need for CIOs to have full accountability for IT acquisition and management decisions.

In December 2017, Congress also enacted legislation that established a new funding mechanism to improve, retire, or replace existing IT systems. The provisions of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2018, commonly referred to as the Modernizing Government Technology Act,[17] established the Technology Modernization Fund within the Department of the Treasury.[18] By using this fund to improve, retire, or replace aging legacy systems, agencies could improve the effectiveness of federal IT systems. The act also established a Technology Modernization Board, which is chaired by the Federal CIO. The board evaluates the proposals submitted by agencies seeking funding to replace legacy systems or acquire new systems, recommends the funding of modernization projects to the Administrator of General Services, and monitors the progress and performance of approved projects.

Managing IT Acquisitions and Operations Included on GAO’s High-Risk List Since 2015

Because of the longstanding challenges in the federal government’s management of IT, we added the management of IT acquisitions and operations as a government-wide challenge on our high-risk list in 2015.[19] We have also continued to designate it as a high-risk area in each of our high-risk series updates since then.[20]

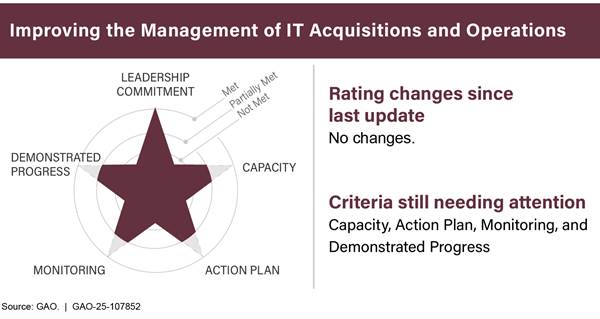

Our experience has shown that the key elements needed to make progress toward being removed from the high-risk list are top-level attention by the administration and agency leaders grounded in the five criteria for removal, as well as any needed congressional action.

The five criteria for removal that we identified in November 2000 are as follows:[21]

· Leadership Commitment. Demonstrated strong commitment and top leadership support.

· Capacity. The agency has the capacity (i.e., people and resources) to resolve the risk(s).

· Action Plan. A corrective action plan exists that defines the root cause, solutions, and provides for substantially completing corrective measures, including steps necessary to implement solutions we recommended.

· Monitoring. A program has been instituted to monitor and independently validate the effectiveness and sustainability of corrective measures.

· Demonstrated Progress. Ability to demonstrate progress in implementing corrective measures and in resolving the high-risk area.

These five criteria form a road map for efforts to improve and ultimately address high-risk issues. Addressing some of the criteria leads to progress, while satisfying all of the criteria is central to removal from the list.

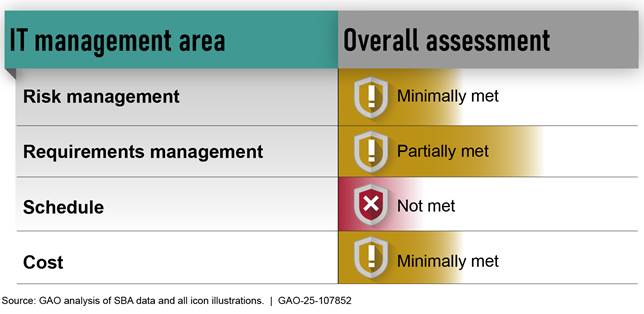

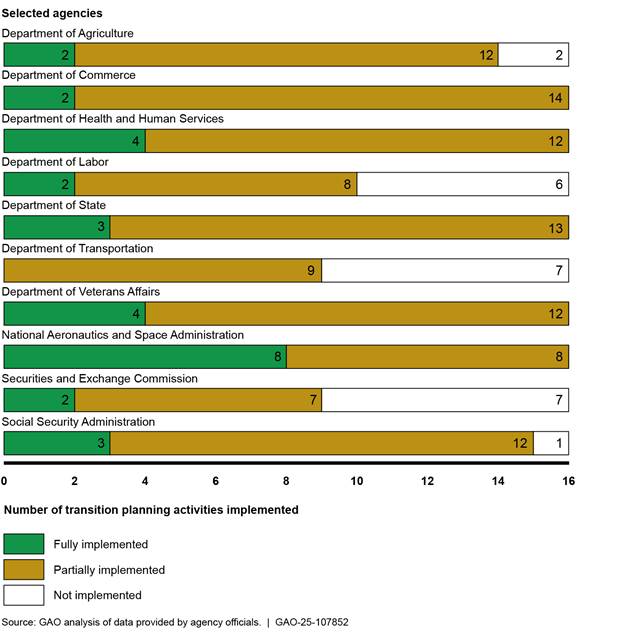

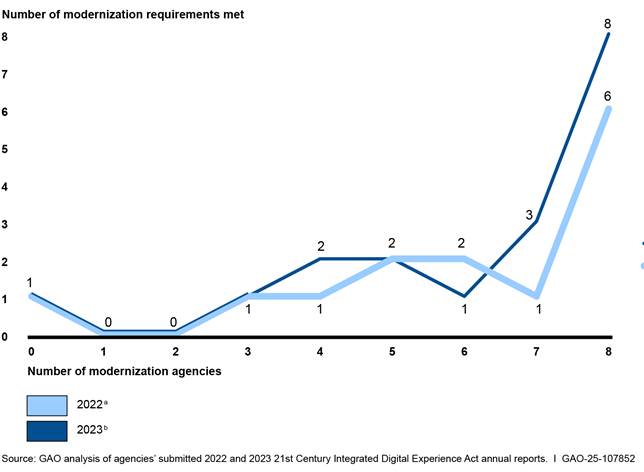

In our April 2023 high-risk report, the federal government’s efforts to improve its management of IT acquisitions and operations had fully met one of the five criteria for removal from the high-risk list—leadership commitment—and partially met the other four, as shown in figure 1.[22] However, since that report, OMB has not maintained its level of leadership commitment to ensure that agencies improve IT acquisitions and management. In addition, agencies have not maintained efforts to develop and implement action plans to address IT management issues. We plan to update our assessment of this high-risk area against the five criteria in February 2025.

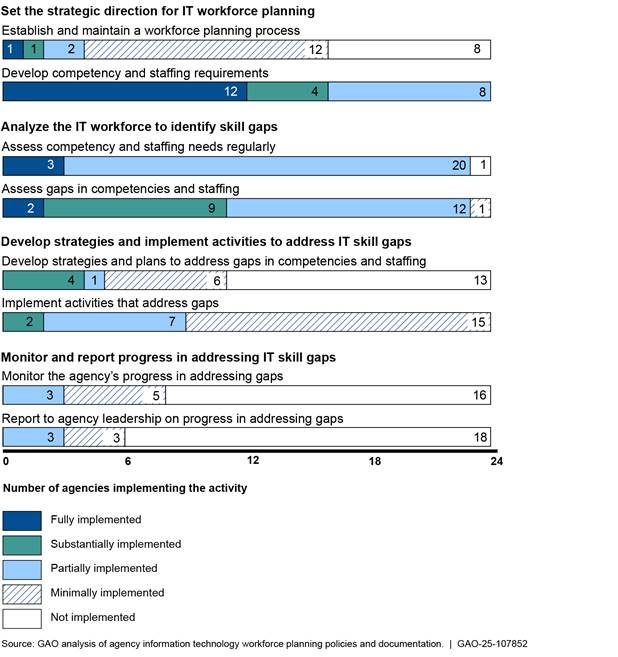

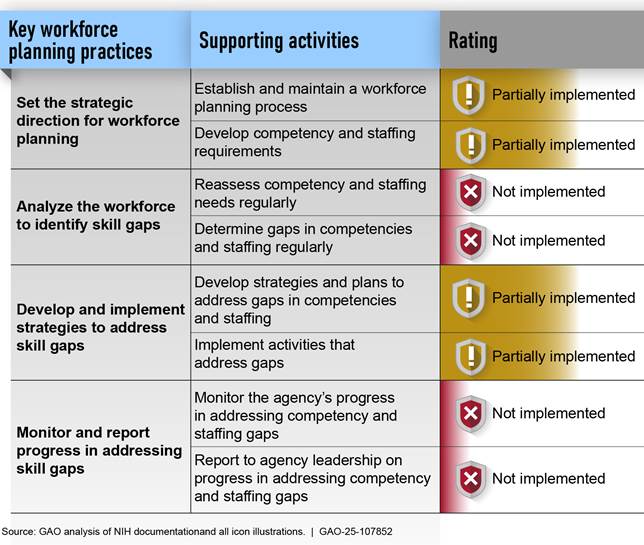

Nine Critical Actions Needed to Address Major IT Acquisition and Management Challenges

Based on our prior work, we have identified three major IT acquisition and management challenges: (1) strengthening oversight and management of IT portfolios, (2) implementing mature IT acquisition and development practices, and (3) building federal IT capacity and capabilities. To address these challenges, we have identified nine critical actions that the federal government needs to take (see figure 2). These three challenges and nine critical actions are discussed in more detail following the figure.

Figure 2: Nine Critical Actions Needed to Address Three Major IT Acquisition and Management Challenges

Strengthening Oversight and Management of IT Portfolios

Overview

Over the years, Congress has enacted various laws to improve the government’s oversight and management of IT. For example, the Clinger-Cohen Act of 1996 required agency heads to designate CIOs to lead reforms that would help better manage technology spending, among other things.[23] In addition, FITARA, enacted in December 2014, strengthened the role of covered agency CIOs in managing IT and includes various requirements for OMB and agencies to perform annual IT portfolio reviews.[24] However, agencies have continued to be challenged in providing effective oversight and management of their IT portfolios. To address this challenge, it is critical that agencies: (1) improve the effectiveness of key IT leadership positions, including the Federal CIO, agency CIOs, and agency chief artificial intelligence (AI) officers; (2) enhance agency efforts to strategically plan for and manage portfolios of IT systems, applications, and software licenses, and to manage existing IT system operations; (3) improve the monitoring of, and transparency into, the performance of IT investments; and (4) strengthen planning and budgeting for the acquisition of IT systems and services.

For more than three decades we have been proponents of having strong agency CIOs and a central federal government CIO in order to address the government’s many IT management challenges.[25] These positions are vital to achieving better results through IT management. However, we have reported that agency CIO responsibilities have not been fully addressed in agency policies consistent with federal laws and guidance and agency CIOs face numerous challenges that impede their ability to effectively manage IT.[26] We have also reported that, because the Federal CIO position is not established in law, its responsibilities are often more limited in key CIO management areas than those of the other types of CIOs.[27] In addition to the leadership provided by agency CIOs and the Federal CIO, OMB recently established a new IT leadership position—the chief AI officer. Specifically, in 2024, OMB issued guidance directing each of the 24 major federal agencies to designate this position, which is to have primary responsibility for coordinating the agency’s use of artificial intelligence.[28] However, given the recent establishment of this position, it is unclear how effective it will be.

In addition, annual agency-wide portfolio reviews—including IT systems, applications, and software licenses—are crucial for assessing the performance, cost-effectiveness, and alignment of IT investments with agency missions and goals. By conducting such reviews, agencies can identify areas of duplication within their IT portfolios and develop strategies to streamline operations and optimize resource allocation. However, we have reported that OMB and agencies are not fully following FITARA’s requirements for portfolio management reviews.[29] As a result, the federal government may be expending resources on IT investments that could be duplicative or may not fulfill the needs of the government or the public. Moreover, approximately 80 percent of the billions of dollars that the federal government invests in IT each year is reportedly spent on operating and maintaining these systems—many of which are legacy systems (i.e., systems that are outdated or obsolete). Given the magnitude of these investments, it is important that agencies effectively manage their operations and maintenance.[30]

Further, monitoring and transparency of IT investment performance are critical to identifying poorly performing investments and holding them accountable for their results. By monitoring such performance, agencies can gain the necessary insight to get ahead of critical problems in an investment, turn around underperforming investments, or terminate investments if appropriate. Without such insight into investment performance, agencies are at risk of not being able to properly manage their IT costs, schedule, performance, and security. Moreover, limited insight into the performance of federal IT investments puts hundreds of millions of dollars at risk of mismanagement and potential waste, if any performance problems are not addressed. The executive branch has implemented various initiatives intended to improve the monitoring of IT investments and provide insight into their performance. However, we have reported on numerous instances where agencies need to improve performance measurement and reporting, and address gaps in performance oversight.[31]

Finally, FITARA was intended to strengthen the authority of CIOs to provide needed direction and oversight of covered agencies’ IT budgets. As part of this, FITARA requires the CIOs of major civilian agencies to have a significant role in the decision processes for all annual and multi-year planning and to approve the IT budget requests of the agencies. However, in March 2018—over 3 years after FITARA was enacted—the President’s Management Agenda pointed out that federal executives were challenged by the lack of visibility into, and accuracy of IT spending data.[32] Since then, we have also reported on weaknesses in agencies’ processes for developing their IT budgets and instances where agencies procured IT and IT-related assets that were often not approved by their CIOs.[33]

What actions should agencies take to improve the effectiveness of key IT leadership positions, including the Federal CIO, agency CIOs, and agency chief artificial intelligence officers?

Federal agencies need to address shortcomings and challenges in implementing CIO responsibilities.

Congress established the CIO position to serve as an agency focal point for IT. Over the past several decades, Congress enacted various laws that established roles and responsibilities for agency CIOs to improve the government’s performance in IT and related information management functions. For example, the Clinger-Cohen Act of 1996 required agency heads to designate CIOs to lead reforms that would help control system development risks, better manage technology spending, and achieve measurable improvements in agency performance.[34]

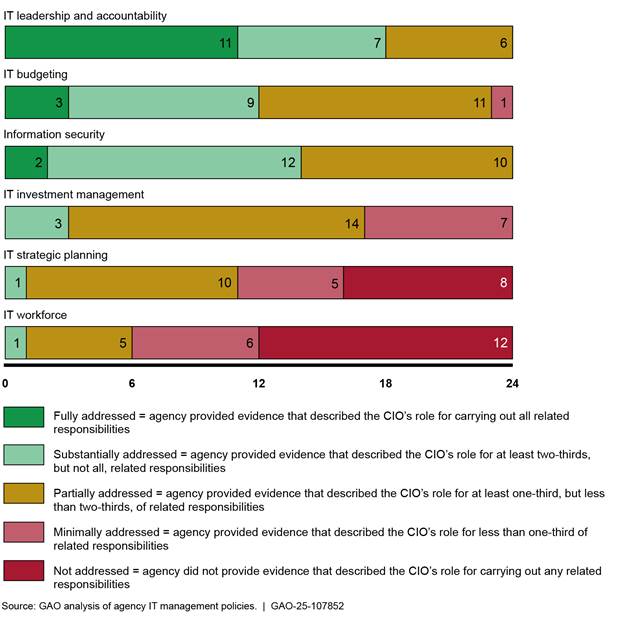

In August 2018, we found that none of the 24 Chief Financial Officers (CFO) Act agencies had policies that fully addressed the role of their CIO consistent with federal laws and guidance.[35] In addition, the majority of the agencies did not fully address the role of their CIOs for any of the six key areas that we identified (see figure 3).

Figure 3: Extent to Which 24 Agencies’ Policies Addressed the Role of Their Chief Information Officers (CIO), Presented from Most Addressed to Least Addressed Area (as of August 2018)

Officials from most agencies stated that their CIOs were implementing the responsibilities even when not required in policy. Nevertheless, the 24 selected CIOs acknowledged in their responses to our survey that they were not always very effective in implementing the six IT management areas.

Shortcomings in agencies’ policies were partially attributable to weaknesses in OMB guidance. We found that OMB guidance did not comprehensively address all CIO responsibilities. For example, OMB guidance did not ensure that CIOs had a significant role in (1) IT planning, programming, and budgeting decisions and (2) execution decisions and the management, governance, and oversight processes related to IT. Until agencies fully address the role of CIOs in their policies, agencies will be limited in addressing longstanding IT management challenges.

Ø We recommended that each of the 24 federal agencies address weaknesses related to the six key areas of CIO responsibility. We also recommended that OMB update and issue guidance related to particular CIO responsibilities, including those relating to the IT workforce, among other things. Fourteen agencies agreed with our recommendations and five agencies had no comments on them. Five agencies (including OMB) partially agreed with our recommendations and one agency disagreed. As of December 2024, 10 agencies had not yet fully implemented our recommendations to address weaknesses related to the six key areas of CIO responsibility, and OMB had not yet addressed two recommendations.

The federal government should use private sector practices to inform CIO roles.

The Comptroller General convened a forum in September 2016 that explored the challenges and opportunities for CIOs to improve federal IT acquisitions and operations.[36] The panel participants—which included private sector IT executives, current and former federal agency CIOs, and members of Congress—identified, among other things, challenges in IT areas such as budget formulation, governance, workforce, operations, and transition planning.

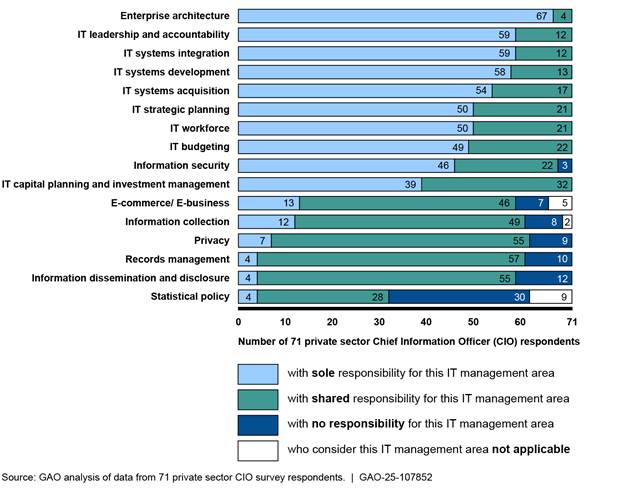

In September 2022, we found that most of the 71 private sector CIOs we surveyed reported having responsibilities that aligned with those of agency CIOs in 13 of 14 key IT management areas.[37] These areas included strategic planning, investment management, and IT systems acquisition. The private sector CIO respondents also reported sharing responsibility with other executives in each IT management area (see figure 4).

Figure 4: Extent of Sharing of IT Management Area Responsibilities Reported by 71 Private Sector Chief Information Officer (CIO) Respondents (as of September 2022)

Responsibilities that were assigned to the Federal CIO (as of September 2022) corresponded to those of agency CIOs in 10 of the 14 key IT management areas. The Federal CIO’s responsibilities also corresponded to those of private sector survey respondents in each of the five responsibility areas directly relevant to the roles of both (e.g., identifying, developing, and coordinating projects to improve government performance through use of IT).

However, the Federal CIO position was not established in law, and its main legal authorities remained those established in 2002 for the OMB position from which the role was established. As such, its responsibilities were often more limited in key CIO management areas than those of agency and private sector CIOs.

Private sector and former agency CIOs reported challenges faced by federal agency CIOs. Specifically, private sector CIOs stated that collaboration with other senior executives was essential to driving successful business outcomes. Conversely, former federal CIOs reported difficulty achieving meaningful collaboration with other managers. In addition, private sector CIOs stated that their companies often look for managerial skills, such as project management skills, when hiring CIOs. By contrast, former agency CIOs stated that technical skills were often a primary driver in the selection of agency CIOs. Fostering shared collaboration and increasing focus on managerial skillsets for agency CIOs could assist federal agencies and their CIOs in securing resources and implementing IT priorities.

Ø We recommended that Congress consider formalizing the Federal CIO position and establishing responsibilities and authorities for government-wide IT management. We also recommended that OMB increase the emphasis placed on collaboration between CIOs and other executives, and take steps to ensure that managerial skills, such as communication and program management skills, have an appropriate role in CIO hiring criteria. OMB did not agree or disagree with our recommendations. As of December 2024, OMB and Congress had not yet addressed these issues.

What actions should agencies take to enhance efforts to strategically plan for and manage portfolios of IT systems, applications, and software licenses, and to manage existing IT system operations?

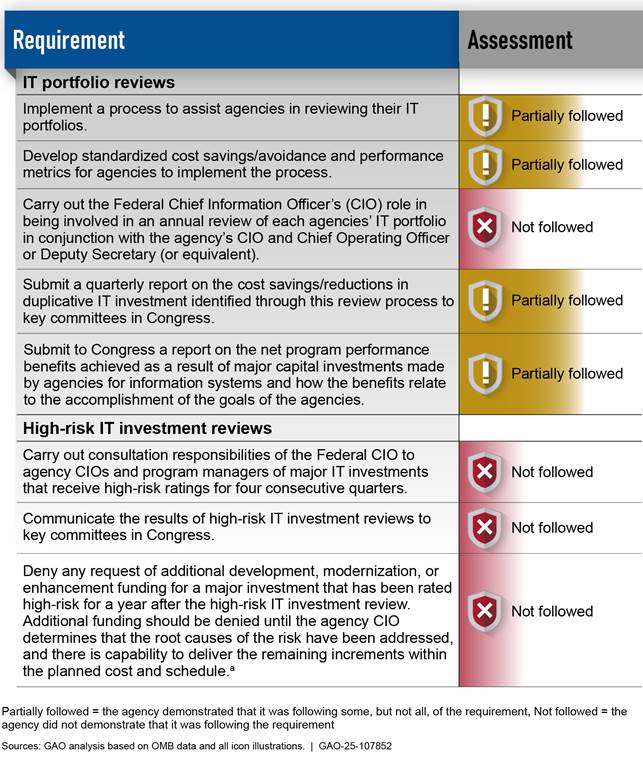

OMB and federal agencies need to address selected statutory requirements for IT portfolio management.

Agency-wide reviews of IT portfolios can be used to, among other things, assess the current maturity of an agency’s IT portfolio management processes, reduce duplication, and achieve savings by identifying opportunities to consolidate investments or move to shared services. FITARA includes various requirements for OMB and agencies on performing annual IT portfolio reviews. FITARA also codifies requirements for OMB and agencies on conducting reviews of high-risk IT investments. Such reviews, when implemented effectively, can be used to turn around, halt, or terminate IT projects that are failing or not producing results.

In November 2024, we found that OMB was not fully addressing eight key statutory requirements contained in FITARA.[38] Specifically, OMB was partially following four of the five requirements on IT portfolio reviews, and not following the three requirements on high-risk IT investments (see figure 5). Until OMB adheres to FITARA’s portfolio management requirements, its oversight of agencies’ IT portfolios, including potentially troubled IT investments, will be limited. As a result, the federal government will likely continue to expend resources on IT investments that do not meet the needs of the government or the public.

Figure 5: Extent to Which the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) Followed Statutory Requirements (as of November 2024)

aThis requirement does not apply to investments at the Department of Defense.

In addition, as of November 2024, 24 CFO Act agencies had not fully addressed FITARA requirements for IT portfolio management. Specifically, none of the 24 agencies fully met the requirements for annual IT portfolio reviews. In addition, eight agencies with major IT investments rated as high-risk for four consecutive quarters did not follow the FITARA requirements for performing high-risk IT investment reviews. Three of the eight agencies performed the reviews, but they did not address the specific requirements in law. The remaining five agencies did not perform the reviews. Not performing these required reviews can permit investments with substantial cost, schedule, and performance problems to continue unabated without necessary corrective actions.

Ø We recommended that OMB improve its IT portfolio review guidance, processes, and reporting and the 24 agencies improve their IT portfolio processes. OMB neither agreed nor disagreed with the 10 recommendations we made to it. OMB responded on behalf of all the agencies to whom we made 36 recommendations but noted that some agencies might respond to address their own circumstances. Of the 24 agencies, six agencies agreed with our recommendations, two neither agreed or disagreed with the recommendations in their comments, 12 deferred to OMB to provide a response, three agencies stated that they had no comments, and one agency provided comments too late to be included in the report but agreed with its recommendations. As of December 2024, the 46 recommendations had not yet been implemented.

Agencies need to apply leading application rationalization practices to improve their software management and achieve cost savings.

Since 2013, OMB has advocated the use of application rationalization—a process by which an agency streamlines its portfolio of software applications with the goal of improving efficiency, reducing complexity and redundancy, and lowering the cost of ownership.[39] Agencies can use application rationalization to identify duplicative, wasteful, and low-value applications in their portfolios and identify opportunities for savings. To effectively perform rationalization, agencies should first establish a complete inventory of applications.

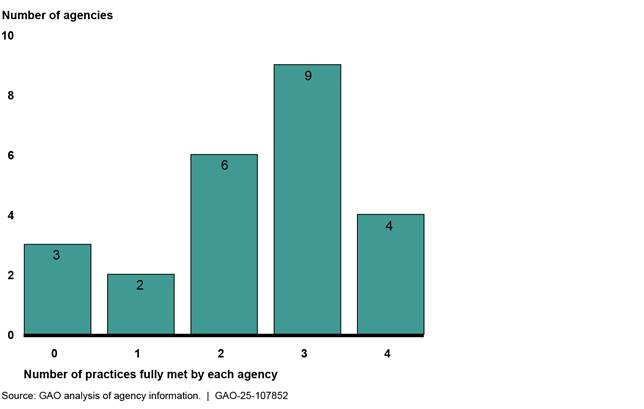

In September 2016, we reported that most of the 24 selected agencies we reviewed had fully met at least three of the four practices we identified for establishing complete application inventories.[40] To be considered complete, agencies’ inventories should (1) include business and enterprise IT systems as defined by OMB; (2) include these systems from all organizational components; (3) specify application name, description, owner, and function supported; and (4) be regularly updated with quality controls in place to ensure the reliability of the information collected. Specifically, four agencies fully met all four practices, nine agencies fully met three practices, six agencies fully met two practices, two agencies fully met one practice, and three agencies did not fully meet any practice (see figure 6). Not accounting for all applications may have resulted in missed opportunities to identify savings and efficiencies.

Figure 6: Assessment of Whether Agencies Fully Met Practices for Establishing Complete Software Application Inventories (as of September 2016)

In addition, we found that six selected agencies relied on their investment management processes and, in some cases, supplemental processes to rationalize their applications to varying degrees. However, five of the six agencies acknowledged that their processes did not always allow for collecting or reviewing the information needed to effectively rationalize all their applications. The sixth agency, the National Science Foundation, stated its processes allowed it to effectively rationalize its applications, but agency documentation supporting this assertion was incomplete. Only one agency—the National Aeronautics and Space Administration—had plans to address shortcomings.

Ø We recommended that 20 agencies improve their software application inventories and five agencies improve their processes to rationalize their applications more completely. DOD disagreed with both recommendations made to it. After reviewing additional evidence, we removed the recommendation associated with improving the inventory but maintained the other. The other agencies agreed to or had no comments on the draft report. As of December 2024, all 24 recommendations had been implemented.

By taking action to implement our recommendations, the agencies are better positioned to identify opportunities to rationalize their applications, which could lead to cost savings and efficiencies. Implementing our final recommendation could lead to additional savings and efficiencies.

In June 2019, OMB published an update to its Federal Cloud Computing Strategy, called Cloud Smart.[41] As part of Cloud Smart, OMB required all federal agencies to rationalize their application portfolios. In doing so, OMB required agencies to assess which applications are best suited for the cloud.

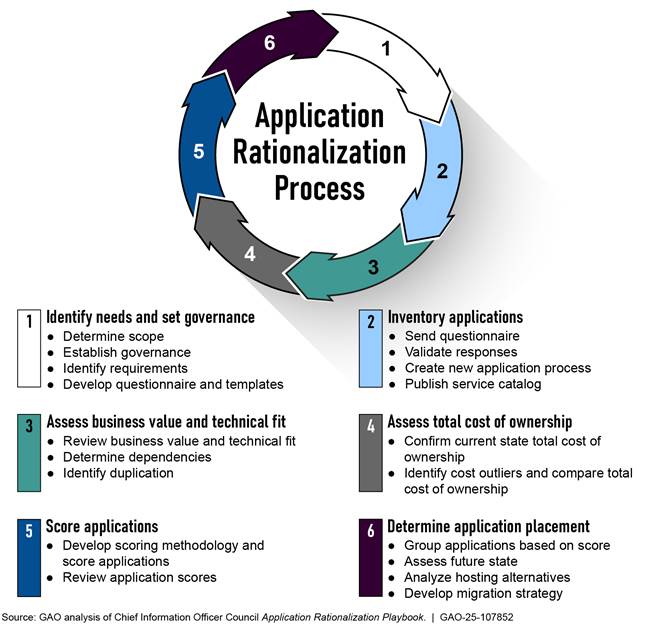

Also in June 2019, the CIO Council issued The Application Rationalization Playbook to assist agencies with implementing the application rationalization process to decide which applications belong in the cloud. The playbook included a six-step rationalization process with discrete actions for agencies to consider when undergoing application rationalization (see figure 7).[42]

Figure 7: CIO Council’s Six-step Application Rationalization Process Outlined in The Application Rationalization Playbook: An Agency Guide to Portfolio Management

In June 2022, we reported that DOD had reported making progress in implementing an enterprise-wide application rationalization effort.[43] However, among other things, DOD had not established a plan to develop and implement an enterprise-wide rationalization process with measurable objectives, milestones, and timelines. DOD also lacked a definition of who was responsible within the department for ensuring application rationalization was successful. Without measurable objectives, milestones, and time frames for rationalization efforts—and holding department components accountable for these efforts—DOD would be less likely to make consistent measurable progress on rationalization or effectively reduce IT duplication.

Ø We recommended that DOD improve its application rationalization planning, among other things. DOD partially concurred with the three related recommendations and described planned actions to address them. As of December 2024, the recommendations had not yet been implemented.

The Department of Health and Human Services needs to identify duplicative pandemic IT systems.

The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and its component agencies are responsible for managing data collection activities to support public health preparedness and response during public health emergencies, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023 reiterated the need for HHS to improve its data collection capabilities and included a provision for us to review those capabilities.[44]

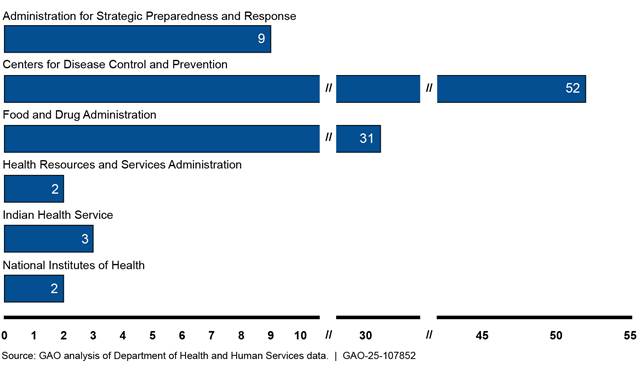

In September 2024, we found, among other things, that HHS had not identified and reduced unnecessary duplication of data in its systems supporting pandemic public health preparedness and response.[45] Because the department did not have a comprehensive list of these systems, we worked with key HHS component agencies and identified a total of 99 systems (see figure 8).

Figure 8: Number of Department of Health and Human Services Systems Supporting Pandemic Public Health Preparedness and Response, per component (as of September 2024)

HHS did not attempt to identify duplication or overlap for these systems. However, in our high-level review of the 99 systems, we identified instances of duplicative pandemic public health preparedness and response data in multiple systems. For example, two pandemic systems that collected similar COVID-19 data, such as cases, deaths, and hospitalization data, were managed by the same program office.

Ø We recommended that HHS (1) develop and maintain an inventory of systems that support pandemic public health preparedness and response, and (2) conduct reviews of such systems across the department to identify and reduce any unnecessary duplication, overlap, or fragmentation and identify mitigation options (e.g., consolidation or elimination of systems). HHS did not agree or disagree with the recommendation to establish a system inventory. The agency agreed with the recommendation to identify duplication, overlap, and fragmentation of pandemic-related data systems and stated that it would analyze the costs and benefits of doing so. As of December 2024, the recommendations had not been implemented.

When these recommendations are implemented, HHS could achieve cost savings by consolidating or decommissioning multiple systems. The agency could also avoid purchasing or developing new systems that would introduce duplication. GAO cannot precisely estimate the savings that could occur. However, given that HHS has identified 99 systems that support pandemic preparedness and response, if even one of these systems could be consolidated or decommissioned, the agency could save hundreds of thousands of dollars over the planned lifespan of the system.

Agencies need to take action to achieve additional savings on software licenses.

Each year, federal agencies purchase thousands of software licenses from vendors. Effective management of commercial software licenses can help organizations avoid purchasing too many licenses—referred to as over-purchasing—that result in unused software. In addition, effective management can help avoid purchasing too few licenses—referred to as under-purchasing— which may result in noncompliance with license terms and cause the imposition of additional fees.

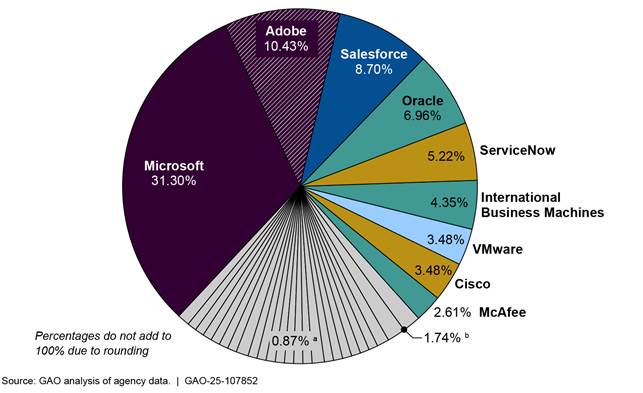

In January 2024, we reported that 24 federal agencies collectively identified 36 software vendors as those with the highest quantity of licenses installed, as of July 2022.[46] Similarly, agencies reported 34 software vendors that were paid the highest amounts for fiscal year 2021 (see figure 9).

aThe 23 vendors shown as 0.87 percent are Broadcom, Computer Associates International, Entrust, ESCgov, FCN, Four, Intelligent Editing, LinkedIn, Mercom, MicroStrategy, NCS Technologies, Palantir Technologies, PKWARE, PTC, Quest Software, SAS Institute, Skillsoft, Splunk, Symantec, Thomson Reuters, Unison Software, Zoom Video Communications, and Zscaler.

bThe two vendors shown as 1.74 percent are Environmental Systems Research Institute and Google.

Key activities for assessing the appropriate number of software licenses are (1) tracking licenses currently in use and (2) regularly comparing the inventory of software licenses currently in use to purchase records. We found that none of the nine selected agencies fully determined whether their five most widely used software licenses were over- or under-purchased.

Ø We recommended that the nine selected agencies consistently track software license usage and compare the inventories with purchased licenses. Eight agencies agreed with the recommendations and one neither agreed nor disagreed. As of December 2024, none of the 18 recommendations had been fully implemented.

As of May 2024, two agencies in our review reported millions in cost savings from assessing one of their five widely used software licenses for over- or under-purchasing. If each of the remaining agencies were able to produce similar results for at least one of their widely used licenses, it could amount to millions of dollars of potential savings.

In May 2014, we reported that OMB and the vast majority of the 24 agencies we reviewed did not have adequate policies for managing software licenses.[47] While OMB had a policy on a broader IT management initiative that was intended to assist agencies in gathering information on their IT investments, including software licenses, it did not guide agencies in developing comprehensive license management policies.

Regarding the 24 agencies, two had comprehensive policies that included the establishment of clear roles and central oversight authority for managing enterprise software license agreements, among other things; 18 agencies had policies but they were not comprehensive; and four had not developed any. The weaknesses in agencies’ policies were due, in part, to the lack of a priority for establishing software license management practices and a lack of direction from OMB.

In addition, the 24 agencies were generally not following the leading practices we identified for managing their software licenses. Specifically, four agencies had fully demonstrated at least one of the leading practices, and none of the agencies had implemented all of the leading practices. Until weaknesses in how agencies manage licenses are addressed, the most widely used applications cannot be determined and thus opportunities for savings across the federal government may be missed.

Ø We recommended that OMB issue a directive to help guide agencies in managing licenses and that the 24 agencies improve their policies and practices for managing licenses. OMB disagreed with the need for a directive, but we believed it was needed, as discussed in the report. Of the 24 agencies to which we made specific recommendations, 11 agencies agreed, five partially agreed, two neither agreed nor disagreed, and six had no comments. As of December 2024, the agencies and OMB had fully implemented 134 of our 136 recommendations, and two recommendations were not yet implemented.

As of January 2024, agencies had reported about $2.1 billion in cost savings since our work in 2014 related to better management of software licenses. Fully implementing our two remaining recommendations could lead to additional savings.

OMB and GSA need to strengthen efforts to lead federal adoption of the Technology Business Management framework.

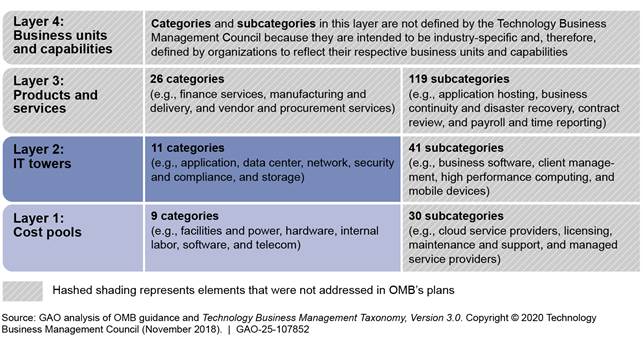

The government has faced longstanding challenges in IT management and spending transparency. In 2017, OMB announced its intention to improve insights into IT spending through government-wide adoption of the Technology Business Management Council’s framework. This framework provides a standard taxonomy that is organized into four layers (cost pools, IT towers, products and services, and business units and capabilities) intended to show an organization’s total IT spending from different perspectives. These four layers are comprised of spending categories and subcategories.

In September 2022, we found that OMB and the General Services Administration (GSA) had taken steps to lead government-wide Technology Business Management adoption, but progress and results were limited.[48] For example, OMB’s initial plans for government-wide adoption required agencies to report IT spending using categories in the first two layers (cost pools and IT towers). However, 5 years after establishing initial plans, OMB had not expanded on requirements to include the rest of the taxonomy—the categories in layers 3 and 4, and subcategories for all layers (see figure 10).

Figure 10: Extent to Which the Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) Plans Addressed Elements of the Technology Business Management Taxonomy Version 3.0 (as of September 2022)

In addition, OMB and GSA assisted agency efforts to implement the Technology Business Management framework by, for example, developing implementation guidance and a maturity model assessment tool. However, OMB and GSA had not assessed agency maturity. Further, they had not analyzed the quality of agencies’ data reported in the first two layers.

OMB and GSA officials maintained that Technology Business Management implementation continues to be a priority. Nevertheless, until OMB establishes documented plans and agency expectations for the remainder of the taxonomy, uncertainty will cloud agency efforts. Further, the continued absence of OMB direction could prevent the federal government from fully achieving intended benefits such as optimizing IT spending.

Ø We recommended that OMB establish requirements for completing the remainder of the taxonomy and assess maturity of agencies’ implementation, among other things. We also recommended that GSA address benchmarking use. We incorporated suggested OMB and GSA revisions for two of the seven total recommendations; the agencies had no comments on the remaining five. As of December 2024, GSA had implemented the one recommendation we made to it and OMB had not implemented any of the six recommendations we made to it.

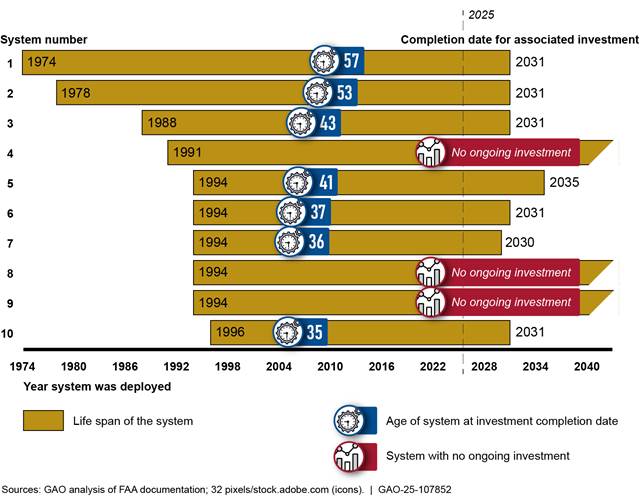

Federal agencies need to modernize aging legacy systems.

The federal government invests more than $100 billion on IT annually, with much of this amount reportedly spent on operating and maintaining existing (legacy) IT systems. Given the magnitude of these investments, it is important that agencies effectively manage their operations and maintenance.

In May 2016, we reported that federal legacy IT investments were becoming increasingly obsolete: many used outdated software languages and hardware parts that were unsupported.[49] Agencies reported using several systems that had components that were, in some cases, at least 50 years old. For example, the Department of Defense (DOD) had one system that was still running on a 1970s computing system and used 8-inch floppy disks, which are a 1970s-era storage device (see figure 11). Replacement parts for the system in 2016 were difficult to find because they were obsolete.

OMB began an initiative to modernize, retire, and replace the federal government’s legacy IT systems. As part of this, OMB drafted guidance requiring agencies to identify, prioritize, and plan to modernize legacy systems. However, until this policy is finalized and fully executed, the government runs the risk of maintaining systems that have outlived their effectiveness.

Ø We recommended that OMB finalize draft guidance to identify and prioritize legacy IT needing to be modernized or replaced. We also recommended that 12 selected agencies address at-risk and obsolete legacy investments that spend a significant proportion of their funding on operations and maintenance activities. OMB and eight of the agencies agreed with our recommendations, two partially agreed, and two had no comments. As of December 2024, 11 recommendations had been fully implemented. Of the three remaining open recommendations, two were to OMB. In March 2024, OMB stated that it believed it had met the intent of the recommendations and considered them implemented. However, we disagree and will continue to monitor the implementation of these recommendations.

In January 2023, we reported that IRS’s legacy IT environment included applications, software, and hardware that were outdated but still critical to day-to-day operations.[50] Specifically, IRS relied extensively on IT to annually collect trillions of dollars in taxes, distribute hundreds of billions of dollars in refunds, and carry out its mission of providing service to America's taxpayers in meeting their tax obligations. Our analysis showed that about 33 percent of IRS’s applications, 23 percent of its software instances in use, and 8 percent of its hardware assets were considered legacy. This included applications ranging from 25 to 64 years in age.

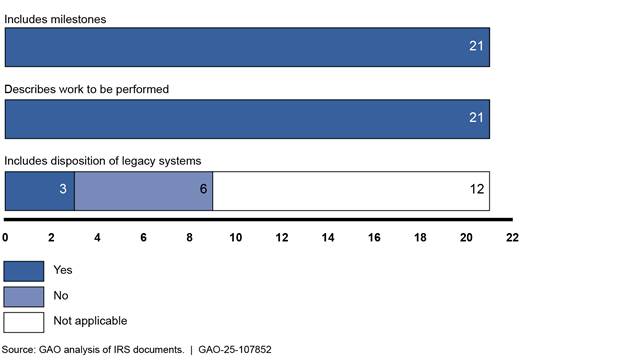

Modernization best practices call for documenting plans that include three key elements: milestones, work to be performed, and disposition of legacy systems. As of August 2022, IRS had documented plans for the 21 modernization initiatives that were underway, including nine associated with legacy systems. All 21 plans addressed two key elements. However, the plans for six of the nine initiatives did not address the disposition of legacy systems (see figure 12). Officials stated they would address this key element at the appropriate time in the initiatives’ lifecycle; however, they did not identify time frames for doing so.

Figure 12: GAO Assessment of the Internal Revenue Service’s (IRS) Modernization Plans (as of August 2022)

IRS suspended operations of six modernization initiatives that had been underway, including two that were essential to replacing the 60-year-old Individual Master File—the authoritative data source for individual tax account data. IRS had been working to replace that File for over a decade. According to officials, the suspensions were due to IRS’s determination to shift resources to higher priorities; staff members working on these suspended initiatives were reassigned to other projects. As a result, the schedule for these initiatives was unknown. In addition, it was unknown whether the agency would meet the 2030 target completion date for replacing the Individual Master File, which would lead to mounting challenges in continuing to rely on a critical system with software written in an archaic language requiring specialized skills. As of September 2024, IRS had resumed three of the initiatives, including the two that are essential to replacing the Individual Master File.

Ø We recommended that IRS establish time frames to complete selected modernization plans, among other things. IRS agreed with the recommendations. However, as of December 2024, none of the nine recommendations had been fully implemented.

What actions should agencies take to improve the monitoring of, and transparency into, the performance of IT investments?

Digital service programs need to measure performance and assess results.

In an effort to improve IT across the federal government, in March 2014 GSA established 18F, which provides IT services (e.g., develop websites) to agencies. In addition, in August 2014 the Administration established the U.S. Digital Service (USDS), which aims to improve public-facing federal IT services.

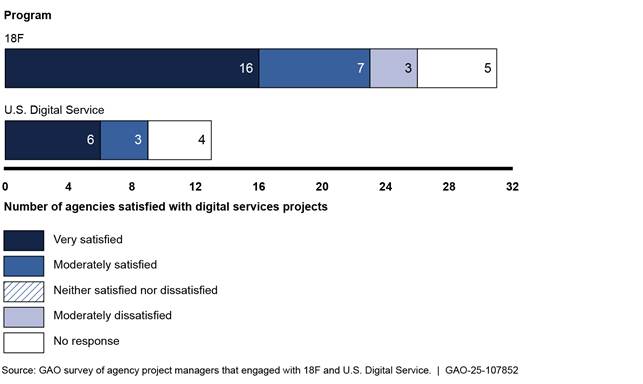

In August 2016, we found that 18F and USDS had provided a variety of services to agencies supporting their IT efforts.[51] Specifically, 18F staff helped 18 agencies with 32 projects and generally provided development and consulting services, including software development solutions and acquisition consulting. In addition, USDS provided assistance on 13 projects across 11 agencies and generally provided consulting services, including quality assurance and problem identification and recommendations. According to our survey, managers were generally satisfied with the services they received from 18F and USDS on these projects (see figure 13).

We also found that both 18F and USDS had partially implemented practices to identify and help agencies address problems with IT projects. Specifically, 18F had developed several outcome-oriented goals and related performance measures, as well as procedures for prioritizing projects; however, not all of its goals were outcome-oriented and it had not yet fully measured program performance. Similarly, USDS had developed goals, but they were not all outcome-oriented and it had established performance measures for only one of its goals. USDS had also measured progress for just one goal. Without fully implementing these practices, it would be difficult to hold the programs accountable for results.

Ø We recommended that OMB and GSA improve goals and performance measurement. OMB and GSA agreed with the recommendations. As of December 2024, GSA had implemented the two recommendations we made to it. OMB had implemented one of our three recommendations and had not yet implemented the other two.

IRS needs to improve reporting for its modernization programs.

IRS relies extensively on IT to annually collect trillions of dollars in taxes, distribute hundreds of billions of dollars in refunds, and carry out its mission of providing service to America's taxpayers in meeting their tax obligations. In August 2022, Congress appropriated tens of billions of dollars to IRS through the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022. These appropriations were intended to be used to bolster taxpayer services and enforcement of the tax code, and modernize IT, among other things.

In March 2024, we reported that, in April 2023, the IRS issued its agency-wide strategic operating plan outlining its vision to use the appropriations contained in the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022.[52] The plan identified five objectives, including a technology objective underpinning the other four (see figure 14).

Figure 14: Inflation Reduction Act Strategic Operating Plan Transformation Objectives (as of April 2023)

The IRS plan stated that it would use the technology objective to, among other things, retire and replace legacy systems. Projects under the technology objective included ongoing modernization programs that had been modified to account for the new appropriations.

Regarding cost and schedule performance of IT modernization programs, IRS reported meeting most of its quarterly targets for fiscal years 2022 and 2023. However, while IRS’s quarterly status reports provide important information on modernization progress, they could be improved by including programs’ historical cost and schedule goals and how quarterly performance compares to overall program goals. For example, we previously reported that a key IT investment was within schedule estimates for 2019 and 2020 but that IRS had changed its overall program plans several times. These changes led to a 9-year milestone delay—from 2014 to 2023. However, the quarterly reports did not show this lengthy delay because they did not include programs’ historical cost and schedule goals.

Ø We recommended that IRS improve its reporting on IT modernization program progress, among other things. IRS concurred with our three recommendations. As of December 2024, the recommendations had not been implemented.

The Department of Labor needs to measure the performance of states’ unemployment insurance IT systems.

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the nation experienced historic levels of job loss. According to Labor data, approximately $878 billion in benefits were paid across all unemployment insurance (UI) programs from April 2020 to September 2022. However, state UI programs with legacy IT systems faced performance issues in processing the unprecedented number of UI claims.[53]

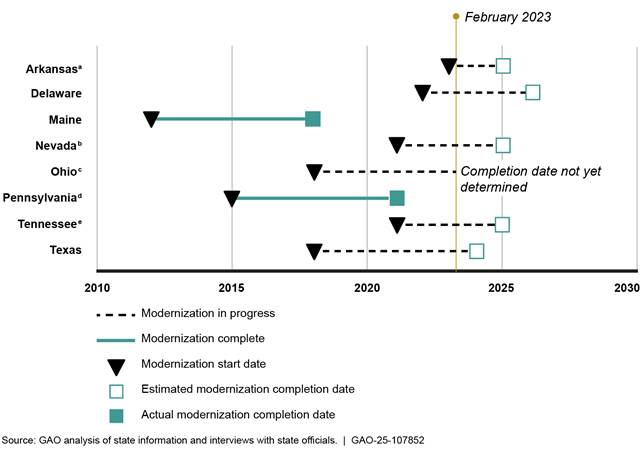

In July 2023, we found that eight selected states were in varying phases of modernizing their UI IT systems, ranging from planning to operations and maintenance.[54] As of February 2023, six of the eight states had modernization efforts underway, but not yet completed (see figure 15).

Figure 15: Unemployment Insurance System Modernization Timeline for Selected States (as of February 2023)

Note: Timelines represent state efforts to modernize their unemployment insurance benefits, appeals, and tax systems, unless otherwise noted.

aArkansas’ modernization effort is focused on its benefits and tax systems only.

bNevada previously completed a modernization of its benefits, appeals, and tax systems in 2015

cOhio’s tax system modernization effort was initiated in 2018 and completed in 2021. As of February 2023, the state was in the planning stages of its benefits and appeals system modernization and had not yet determined an anticipated completion date.

dPennsylvania’s 2015 to 2021 modernization effort focused on its benefits and appeals systems only.

eTennessee previously completed a modernization of its benefits and appeals system in 2016.

We also found that Labor had gaps in its oversight of states’ UI IT performance. Specifically, although Labor is responsible for overseeing the UI program to ensure that the states are operating the program effectively and efficiently, it had not measured states’ UI IT performance. For example, it had not measured the number of states using cloud infrastructures to support their UI systems. Measuring areas such as this is important because it could help inform Labor of where gaps may exist in states’ IT capabilities and where to commit additional resources.

According to Labor officials, the department had not measured states’ UI IT performance because it had not yet defined IT standards to measure states against. As a result, Labor was limited in its ability to monitor whether states’ UI IT systems were performing efficiently and effectively, identify gaps in UI IT modernization, and ensure that resources are properly allocated to address any gaps.

Ø We recommended that Labor (1) define UI IT modernization standards for states and (2) measure states’ performance against the established standards. Labor partially agreed with the first recommendation and agreed with the second one. As of December 2024, the recommendations had not yet been implemented.

What actions should agencies take to strengthen planning and budgeting for the acquisition of IT systems and services?

Agencies need to improve CIOs’ review and approval of IT budgets.

One of the purposes of FITARA was to strengthen the authority of CIOs at major departments and agencies to provide needed direction and oversight of covered agencies’ IT budgets. Among other things, FITARA requires the CIOs of certain major civilian agencies to have a significant role in the decision processes for all annual and multi-year planning and to approve the IT budget requests of the agencies.

In November 2018, we reported that four selected departments—Energy, HHS, Justice, and Treasury—took steps to establish policies and procedures that align with eight selected OMB requirements intended to implement FITARA and to provide the CIO visibility into and oversight over the IT budget.[55] For example, of the eight OMB requirements, all four departments had established policies and procedures related to the level of detail with which IT resources are to be described in order to inform the CIO during the planning and budgeting processes. However, the departments varied in how fully they had established policies and procedures related to some other OMB requirements, and none of the four departments had yet established procedures for ensuring that the CIO had reviewed whether the IT portfolio includes appropriate estimates of all IT resources included in the budget request (see figure 16).

Figure 16: Evaluation of Selected Departments’ Policies and Procedures for Key IT Budgeting Requirements (as of November 2018)

Where the departments had not fully established policies and procedures, it was due, in part, to having not addressed in their FITARA implementation and delegation plans how they intended to implement the OMB requirements.

In addition, all four selected departments lacked quality assurance processes for ensuring their IT budgets were informed by reliable cost information. Specifically, the selected departments did not have IT capital planning processes for (1) ensuring government labor costs had been accurately reported, (2) aligning contract costs with IT investments, and (3) utilizing budget object class data to capture all IT programs. This resulted in billions of dollars in requested IT expenditures without departments having comprehensive information to support those requests, and nearly $4.6 billion in IT contract spending that was not explicitly aligned with investments in selected departments’ IT portfolios. This was due to a lack of processes for periodically reviewing data quality and estimation methods for government labor estimates, as well as a lack of mechanisms to cross-walk IT spending data in their procurement and accounting systems with investment data in their IT portfolio management systems.

Ø We recommended that the selected departments address gaps in their IT budgeting policies and procedures, and establish procedures to ensure IT budgets are informed by reliable cost information, among other things. Two agencies and their component agencies agreed with our recommendations. One agency neither agreed nor disagreed with the recommendations, while its component agency agreed with the recommendations made to it. One agency partially agreed with one recommendation and agreed with the other recommendations made to it and its component agency. As of December 2024, the departments had implemented 38 of our 43 recommendations and had not yet fully implemented five.

By implementing these recommendations, we estimate that the agencies have the potential to realize financial benefits of hundreds of millions of dollars in total. These savings could be achieved through better accounting of government labor and contract costs and improved oversight of IT spending.

The Department of Veterans Affairs needs to improve CIO oversight of procurements.

The Department of Veterans Affairs’ (VA) mission is to promote the health, welfare, and dignity of all veterans in recognition of their service to the nation by ensuring that they receive benefits, social support, medical care, and lasting memorials. In carrying out this mission, the department operates one of the largest health care delivery systems in America, providing health care to millions of veterans. VA’s ability to effectively serve veterans and other eligible individuals depends on the functionality of the underlying IT systems that support its core activities. The department annually spends billions of dollars on IT each year to support the delivery of veterans’ benefits and health care services.

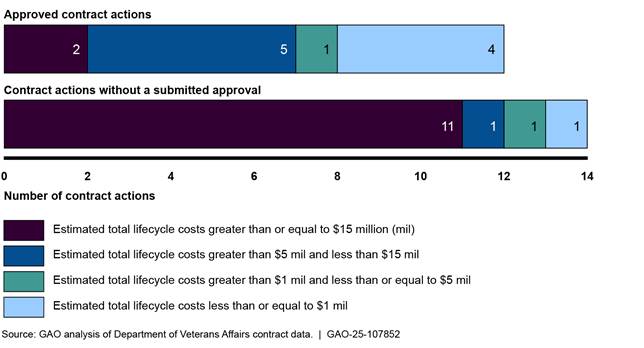

In March 2023, we found that VA procured IT and IT-related assets and activities that were often not approved by its CIO,[56] as required by FITARA. Specifically, between March 2018 and the end of fiscal year 2021, VA awarded 11,644 new contract actions categorized as IT. However, VA did not provide evidence of CIO approval for 4,513 (or 39 percent) of these contract actions.

A more in-depth review of 26 selected IT contract actions from fiscal year 2021 confirmed that 12 had documentation showing approval by appropriate agency officials at the required level of authority. The remaining 14 contract actions lacked CIO approval documentation (see figure 17).

Figure 17: The Department of Veterans Affairs’ Documented Chief Information Officer Approvals for Selected Fiscal Year 2021 IT Contract Actions (as of March 2023)

Of the 14 contract actions lacking CIO approval, 13 were managed by non-IT contracting offices. According to VA officials, their contracting systems lacked an automated control that would remind contracting officers of CIO review and approval requirements. Without an automated check or control to ensure contracting officer compliance, it is likely that there will continue to be IT procurements that will not be routed for CIO review. This lack of visibility into the procurement of much of VA’s IT assets and activities constrained the CIO’s opportunity to provide input on current and planned IT acquisitions. This, in turn, could result in awarding contracts that are duplicative or poorly conceived.

Ø We recommended that VA implement automated controls into relevant contracting systems to ensure CIO review of IT procurements. VA concurred with the recommendation. As of December 2024, this recommendation had not yet been implemented.

What ongoing work is GAO doing related to this challenge area?

Given the importance of addressing this challenge, we are continuing to review and assess agencies’ various IT acquisition and management efforts in this area. It is essential that executive branch agencies focus on improving the effectiveness of key IT leadership positions, including the Federal CIO, agency CIOs, and agency chief AI officers; enhance efforts to strategically plan for and manage IT portfolios and operations; improve the monitoring of, and transparency into, IT investment performance; and strengthen the planning and budgeting for the acquisition of IT systems and services. These actions are critical to improving federal agencies’ oversight and management of their IT portfolios and ensuring the efficient and cost-effective use of the billions of dollars the government spends on IT each year. Table 1 identifies our ongoing work related to each action associated with this challenge area.

Table 1: GAO’s Ongoing Work Related to the Strengthening Oversight and Management of IT Portfolios Challenge Area (as of December 2024)

|

Critical action |

Related ongoing GAO work |

|

1. Improve the effectiveness of key IT leadership positions, including the federal CIO, agency CIOs, and agency chief artificial intelligence officers. |

We do not have any ongoing work related to this action area. |

|

2. Enhance agency efforts to strategically plan for and manage portfolios of IT systems, applications, and software licenses, and to manage existing IT system operations. |

A review of the extent to which federal agencies have adopted selected key Technology Business Management practices to improve insight into IT investment spending. |

|

3. Improve the monitoring of, and transparency into, the performance of IT investments. |

A review of the Social Security Administration’s management and oversight of its IT investments, including the extent to which the agency’s IT investment management process complies with federal laws, guidance, and key practices; and the extent to which the agency is evaluating the outcomes of selected IT investment management efforts. |

|

4. Strengthen planning and budgeting for the acquisition of IT systems and services. |

A review of the extent to which federal agencies have identified their legacy IT systems in need of modernization and developed plans for modernizing those most in need. |

Source: GAO. I GAO-25-107852

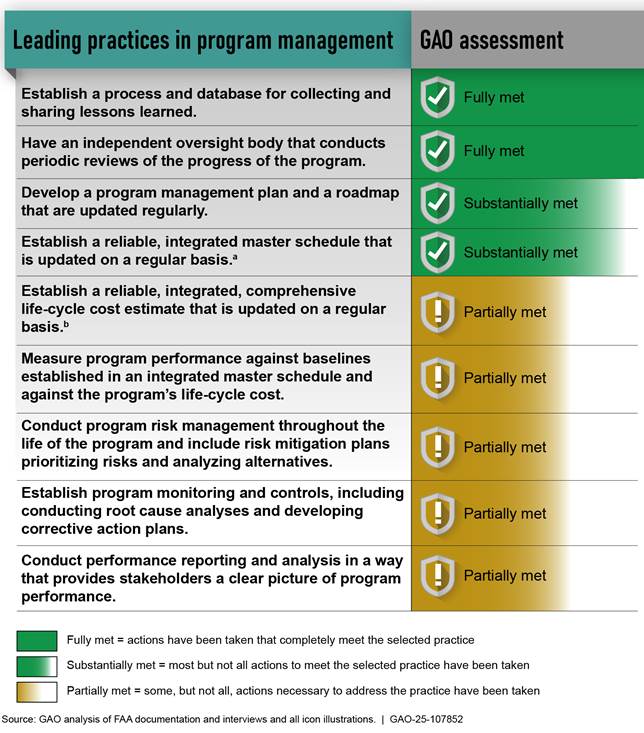

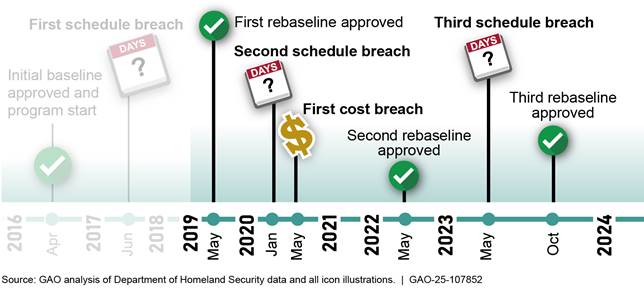

Implementing Mature IT Acquisition and Development Practices

Overview

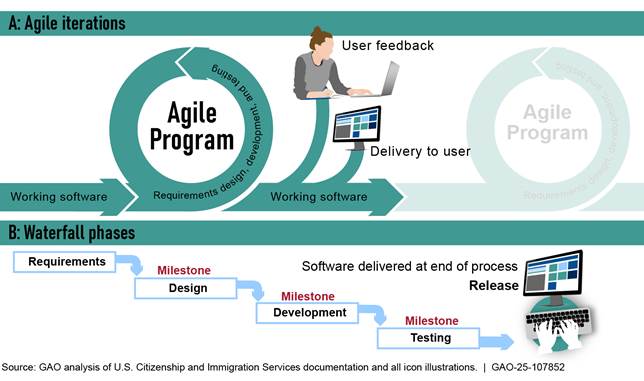

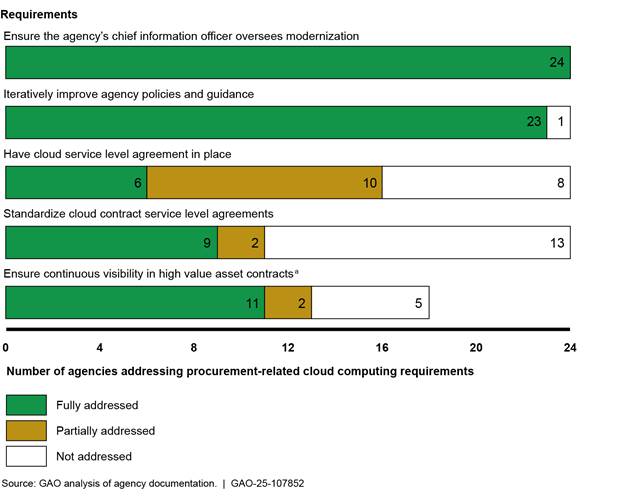

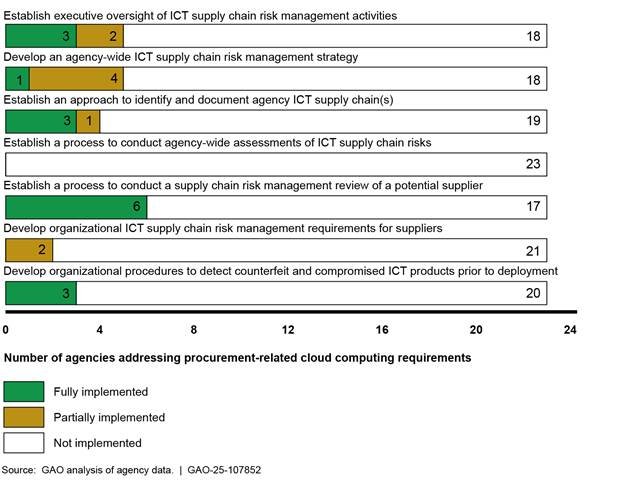

Over the past two decades the executive branch has undertaken numerous initiatives to better manage the more than $100 billion that is annually invested in IT. However, agencies have continued to be plagued by IT investments that too frequently fail to deliver capabilities in a timely manner and incur cost overruns or schedule slippages while contributing little to mission-related outcomes. To address the government’s challenge in implementing mature IT acquisition and development practices that are essential to successfully acquiring IT, it is critical that agencies improve implementation of leading IT acquisition and development practices to effectively plan and manage IT project costs, schedules, risks, requirements, and testing. It is also imperative that agencies strengthen the planning and management of cloud services, supply chains, and telecommunications services.

Leading IT acquisition and development practices have been developed by both industry and the federal government.[57] These practices identify key actions that should be taken to effectively and efficiently manage IT project costs, schedules, risks, requirements, and testing. By implementing these practices, agencies can help guide the successful acquisition of IT, thereby increasing the likelihood that systems will meet users’ needs and perform as intended. Effective implementation of these practices may also lead to financial benefits for agencies by reducing the risk of cost increases and schedule overruns and enabling agency leadership to make decisions based on quality cost and schedule project control data. However, for decades we have reported on instances of poor program performance that were the results of agencies’ inconsistent and incomplete implementation of these practices.

We have also reported on practices that agencies should implement to effectively plan and manage their cloud services, supply chains, and telecommunications. These practices are based on guidance from OMB and the National Institute of Standards and Technology and our prior work. For example, one of the practices is for agencies to establish guidance related to cloud service level agreements (which define the levels of service and performance the agency expects its cloud providers to meet).[58] Other practices include developing agency-wide strategies for managing information and communications technology supply chain risks[59] and developing accurate inventories of telecommunications assets and services.[60] However, we have reported on limitations in numerous agencies’ implementation of these important practices.

What actions should agencies take to improve implementation of leading IT acquisition and development practices to effectively plan and manage IT project costs, schedules, risks, requirements, and testing?

The Small Business Administration needs to implement leading acquisition practices for managing its IT projects’ risks, requirements, cost, and schedule.

The Small Business Administration (SBA) administers contracting assistance programs and promotes small business participation in federal contracting through a variety of programs. To certify small businesses for eligibility in its contracting assistance programs, SBA relies on multiple IT systems. However, SBA’s past attempts to modernize its IT systems experienced challenges and did not deliver expected results. To help address these shortcomings, in 2023, SBA initiated the Unified Certification Platform project. This project was intended to deploy a new system to allow small businesses to more efficiently apply for and maintain certifications to SBA’s contracting assistance programs.

In November 2024, we reported on SBA’s efforts to deploy the Unified Certification Platform system.[61] SBA deployed the system on October 18, 2024. However, work remained to develop additional, more complex functionality, secure the system, and migrate data.

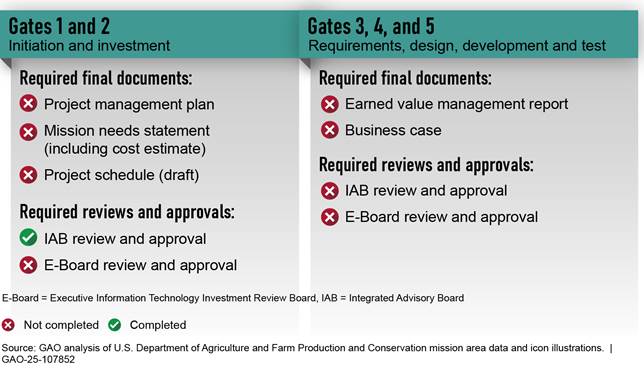

Our analyses of SBA’s efforts showed that, among other things, leading practices for risk and requirements management and schedule and cost estimation had not been fully implemented (see figure 18).

Figure 18: Extent to Which the Small Business Administration (SBA) Met Selected IT Management Areas for the Unified Certification Platform Modernization (as of November 2024)

Specifically, we identified critical management gaps, including that SBA did not have a project level risk management strategy, a risk mitigation plan, and did not fully identify and document risks. In addition, the agency had not conducted a traceability analysis to ensure project security requirements had been met. Further, the project’s schedule and cost estimates were unreliable and did not follow leading cost and schedule estimating practices. The weaknesses in SBA’s risk, requirements, cost, and schedule management practices were due, in part, to shortcomings in SBA’s policies and procedures.

Ø We recommended that SBA address critical project risk management issues and, among other things, establish and implement policies and procedures to ensure that cost and schedule estimates are developed using leading practices. Of 14 total recommendations, SBA concurred with three, partially concurred with three, and did not concur with eight recommendations. We maintained that the recommendations were warranted. As of December 2024, SBA had not yet implemented any of the recommendations.

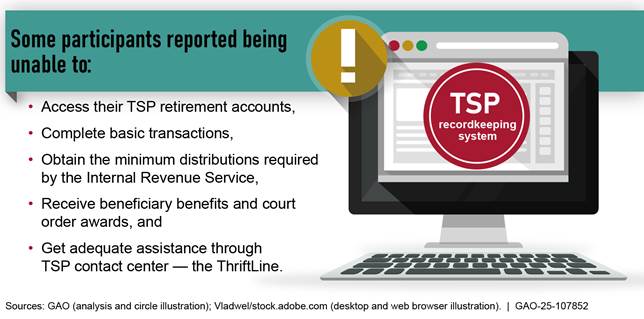

The Department of Education needs to apply disciplined system acquisition practices to its new student aid system.

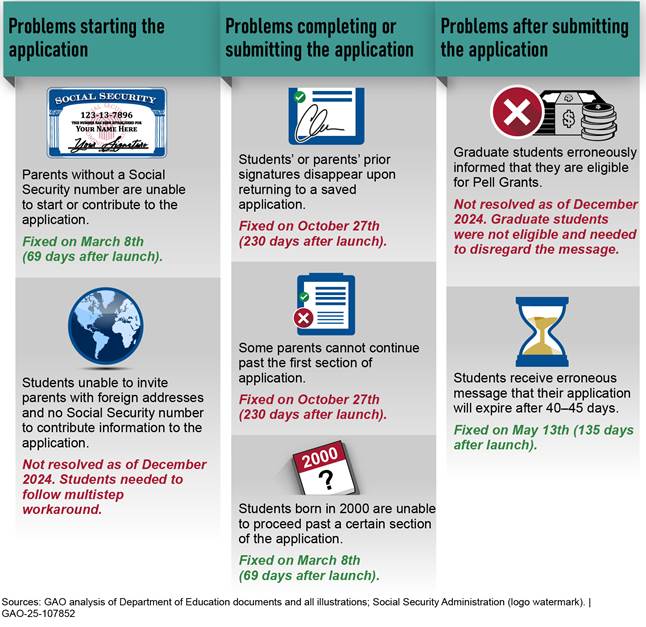

Students and parents can apply for financial aid by completing the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) form and submitting it to the Department of Education’s Office of Federal Student Aid (FSA). In 2021, FSA initiated an effort to replace the aging system that processes the forms, and in December 2023 the office deployed a new system to process forms for the 2024-2025 school year. However, student aid applicants reported that the new system had availability issues, recurring errors, and long wait times.

In September 2024, we reported that technical problems had impeded students’ ability to complete the FAFSA.[62] As of August 2024, Education had identified over 40 separate technical issues with the initial rollout of the FAFSA form. These issues included problems that blocked some students from completing the application—or in some cases prevented them from starting it (figure 19 provides examples of the issues users experienced).

Figure 19: Examples of Technical Issues Affecting the Rollout of the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) (as of December 2024)

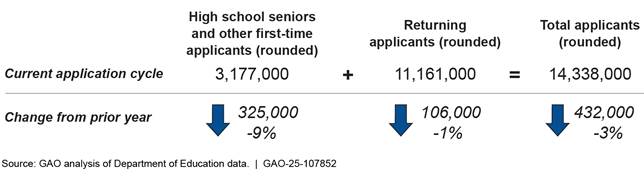

These technical issues led to troubling impacts on students, parents, and schools, including their ability to plan for the upcoming school year. This contributed to about 9 percent fewer high school seniors and other first-time applicants submitting a FAFSA (see figure 20).

Figure 20: Decline in Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) Submissions, Current Application Cycle Compared to Prior Year

Notes: Numbers may not add up due to rounding. Data are through August 25 of each cycle. The current application cycle refers to applications for the 2024-25 award year and the prior cycle refers to the 2023-24 award year. According to Education, first-time applicants are identified as individuals who do not have a processed FAFSA from a previous cycle. Education identified high school seniors using several criteria, including those who are no older than 19 years of age and entering college as a freshman with a high school diploma.

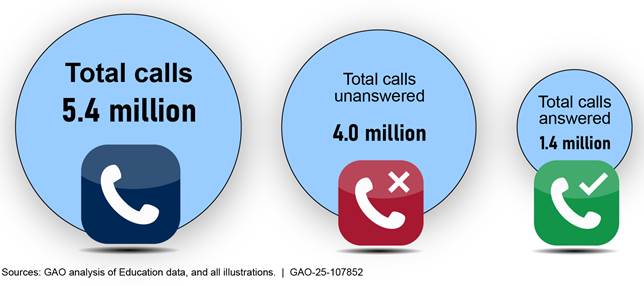

In addition, Education did not consistently provide students with timely and sufficient information or support necessary to complete the new FAFSA. Nearly three-quarters of calls to Education’s call center went unanswered during the first 5 months of the rollout due to understaffing (see figure 21).

Notes: “Total calls unanswered” is the total of calls that were either automatically disconnected or abandoned by the caller; and “total calls answered” is the total of calls that were answered by a call center agent when offered the call.