NONBANK MORTGAGE COMPANIES

Greater Ginnie Mae Involvement in Interagency Exercises Could Enhance Crisis Planning

Report to Congressional Addressee

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Jill Naamane at (202) 512-8678 or NaamaneJ@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑107862, a report to congressional addressee.

Greater Ginnie Mae Involvement in Interagency Exercises Could Enhance Crisis Planning

Why GAO Did This Study

Nonbanks service the majority of federally backed home mortgages. Nonbank failures could significantly disrupt mortgage markets and increase federal fiscal exposure.

Federal monitoring and oversight of nonbanks is spread among several agencies. These include Ginnie Mae and FHFA, which play key roles in supporting stable markets for mortgage-backed securities. Interagency coordination can help address the challenges of managing systemwide risks in a fragmented federal structure.

Since 2013, GAO has designated the federal role in housing finance as a high-risk area. This report examines the extent to which FHFA and Ginnie Mae coordinate to monitor nonbanks.

GAO reviewed FHFA and Ginnie Mae policies and procedures, as well as documentation on an FSOC exercise simulating a major nonbank failure. GAO also interviewed FHFA, Ginnie Mae, and FSOC officials.

What GAO Recommends

GAO recommends that Ginnie Mae develop processes for participating in interagency exercises—taking into consideration the potential risks and benefits of sharing nonpublic information in a crisis—and for incorporating lessons learned from the exercises into its strategy for managing nonbank failures. Ginnie Mae neither agreed nor disagreed with GAO’s recommendation.

What GAO Found

Nonbank mortgage companies—nondepository institutions specializing in mortgage lending—play a major role in the housing finance system. Nonbanks service most mortgages backing securities guaranteed by Ginnie Mae, a government-owned corporation, and by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, enterprises under Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) conservatorships.

Since 2020, FHFA and Ginnie Mae have coordinated on aspects of nonbank monitoring, including

· jointly updating program eligibility requirements (such as capital and liquidity standards) to strengthen nonbank financial capacity and promote consistency;

· enhancing nonbank reporting of financial data the agencies use for monitoring and risk analysis; and

· participating in the Financial Stability Oversight Council’s (FSOC) task force on nonbank mortgage servicing. Both agencies contributed to a May 2024 FSOC report on the risks of nonbanks. They also have been supporting initiatives to develop risk-monitoring metrics and a plan for interagency coordination in a crisis.

However, Ginnie Mae played a limited role in the task force’s October 2023 crisis planning exercise, which simulated the failure of a large nonbank working with Ginnie Mae and the enterprises. Ginnie Mae did not produce responses to discussion questions during the exercise, citing legal restrictions and risks of sharing nonpublic information about its counterparties. But not all the exercise questions required sharing such information. For example, participants were asked to consider the possible consequences of their actions on external parties, information they would need from other agencies, and how they would communicate with other agencies. Ginnie Mae also did not identify or document lessons learned from the interagency exercise and lacks processes for doing so. By developing processes to guide participation in these exercises and incorporating lessons learned into its strategy for managing nonbank failures, Ginnie Mae could enhance its interagency coordination during a nonbank crisis and bolster overall federal preparedness.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

enterprise |

government-sponsored enterprise |

|

FHFA |

Federal Housing Finance Agency |

|

FSOC |

Financial Stability Oversight Council |

|

MBS |

mortgage-backed security |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

January 31, 2025

The Honorable French Hill

Chairman

Committee on Financial Services

House of Representatives

Since the 2007–2009 financial crisis, mortgage markets increasingly have depended on federal support and on nonbanks to originate and service single-family mortgage loans.[1] Nonbanks play a particularly large role in supporting the approximately $9 trillion in outstanding federally backed mortgages. As of 2024, nonbanks serviced most loans in mortgage-backed securities (MBS) guaranteed by Ginnie Mae and by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, government-sponsored enterprises (enterprises) under Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) conservatorships.[2]

Federal oversight of nonbanks is somewhat fragmented. Nonbanks generally do not have a federal regulator comprehensively overseeing their safety and soundness, although Ginnie Mae and FHFA are among several federal entities that monitor nonbanks to help manage the risks of agency MBS guarantee programs and for other purposes.

The fragmented nature of federal housing finance oversight can make it challenging to manage systemwide risks or events.[3] For instance, nonbanks may face financial challenges under stress conditions.[4] The failure of a large nonbank or multiple nonbanks could significantly disrupt the availability and servicing of mortgage loans and increase federal fiscal exposures. In such cases, interagency coordination can help define agencies’ roles and responsibilities and promote accountability in a crisis.

Since 2013, we have designated resolving the federal role in housing finance as a high-risk area because of the government’s large fiscal exposure and because objectives for the future federal role remain unestablished. We prepared this report at the initiative of the Comptroller General.

This report examines the extent to which FHFA and Ginnie Mae coordinate to monitor nonbanks.[5] To address this objective, we reviewed FHFA and Ginnie Mae documentation on their goals, policies, and procedures for nonbank monitoring and interagency coordination. We also reviewed agency documentation to identify instances in which they coordinated on nonbank monitoring from 2020 through 2024. This included documentation on a 2023 Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) tabletop exercise simulating a major nonbank failure.[6] Additionally, we interviewed FHFA and Ginnie Mae officials and officials from FSOC’s Nonbank Mortgage Servicing Task Force. We then assessed FHFA and Ginnie Mae coordination efforts against the agencies’ goals and strategies.

To provide context on the role of nonbanks in the housing finance system, we analyzed Inside Mortgage Finance data on the share of federally backed mortgage loans and loans serviced by nonbanks.[7] We are conducting related, ongoing work on the evolving role of nonbanks in the housing finance system and on FHFA’s and Ginnie Mae’s financial assessments of nonbanks.

We conducted this performance audit from September 2024 to January 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Mortgage Lending and Servicing

In the primary mortgage market, lenders originate mortgage loans to borrowers to purchase housing. After origination, loans must be serviced until paid off or foreclosed. Lenders engage mortgage servicers to perform various functions, including collecting payments from the borrower and remitting them to the lender, sending borrowers monthly account statements and tax documents, and responding to customer service inquiries. The right to service a mortgage loan becomes a distinct asset—a mortgage servicing right—when contractually separated from the loan as the loan is sold or securitized.

Federal Support of Mortgage Markets

Lenders hold mortgage loans in their portfolios or sell them to institutions in the secondary market to transfer risk or to increase liquidity. Secondary market institutions, such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, can hold the loans in their portfolios or pool them into MBS that are sold to investors.

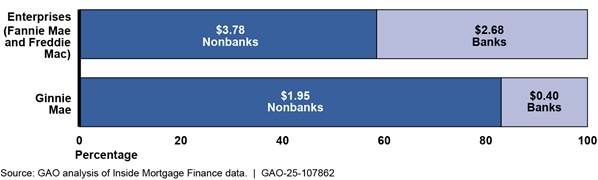

As shown in figure 1, as of 2024, the federal government supported a large share of the mortgage market through enterprise and Ginnie Mae MBS (collectively, agency MBS).[8] As of the second quarter of 2024, single-family mortgage servicing outstanding in the United States totaled over $14 trillion. About 65 percent of that amount, or $9 trillion, consisted of loans in agency MBS.

Figure 1: Share of Single-Family Mortgage Servicing Outstanding by Market Segment, as of Second Quarter 2024

Notes: “Other” refers to loans held by real estate investment trusts, life insurance companies, and individual investors, among others. Market segment percentages do not sum to 100 due to rounding.

Nonbank Loan Servicing of Agency Mortgage-Backed Securities

The role of nonbanks in the mortgage market has increased since the 2007–2009 financial crisis. We previously reported that reasons for the rise in nonbanks include banks’ retreat from mortgage markets, caused partly by changes in capital requirements that made it more expensive for banks to hold mortgage loans.[9] Banks also incurred financial costs from mortgage-related litigation in the wake of the 2007–2009 financial crisis.

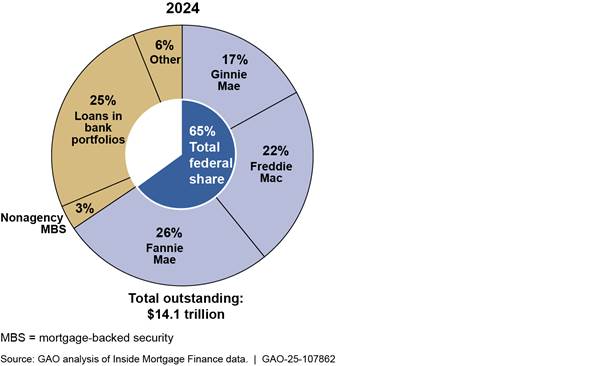

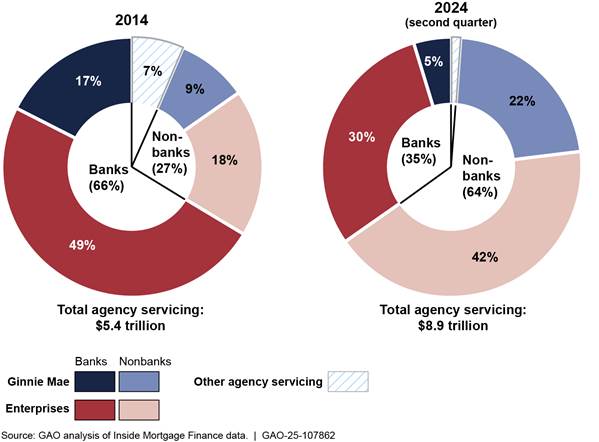

Since 2014, nonbanks serviced an increasing share of loans in agency MBS compared to banks. Overall, the share of loans in agency MBS serviced by nonbanks rose from 27 percent in 2014 to 64 percent as of the second quarter of 2024 (see fig. 2). In 2014, nonbanks serviced about 25 percent of loans by dollar value in enterprise MBS and 33 percent in Ginnie Mae MBS, according to Inside Mortgage Finance data. As of the second quarter of 2024, nonbanks serviced about 58 percent of loans in enterprise MBS and 81 percent of loans in Ginnie Mae MBS.

Figure 2: Percentage of Loans in Agency Mortgage-Backed Securities Serviced by Nonbanks, by Dollar Value, as of 2014 and Second Quarter 2024

Notes: Agency securities are those that Ginnie Mae or the enterprises (Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac) guaranteed. “Other” refers to loans that Ginnie Mae or the enterprises serviced or state housing finance agencies held. Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

As of the second quarter of 2024, a number of large nonbanks were approved to participate in both Ginnie Mae and enterprise programs, presenting counterparty risks to both sectors.[10]

· According to data from Inside Mortgage Finance, six nonbanks were among the top 10 servicers for both Ginnie Mae and the enterprises. Collectively, these six nonbanks had agency MBS servicing portfolios of more than $3.45 trillion.[11]

· Of the top 25 agency MBS servicers, 17 were nonbanks. Fifteen of the 17 serviced loans in both Ginnie Mae and enterprise MBS programs. Collectively, these 15 companies had agency MBS servicing portfolios of about $4.5 trillion.

The large market share that nonbanks hold poses some concerns because nonbanks may face liquidity challenges under stress conditions. For example, nonbank mortgage servicers may have difficulty funding payments to MBS investors during periods of increased mortgage delinquencies. Nonbanks do not have access to the liquidity facilities that the Federal Reserve System or Federal Home Loan Bank System make available to member banks. Instead, nonbanks rely on short-term credit facilities, such as lines of credit and advances with borrowing limits. During difficult economic conditions, these creditors may tighten loan terms or face incentives to call loans due and seize collateral in the event of default. Furthermore, because of the specialized nature of these nonbanks, their assets are concentrated in mortgage-related assets, like mortgage servicing rights, which are sensitive to market developments such as changes in mortgage delinquency rates. The value of servicing rights also can vary with interest rate changes.

Nonbank Monitoring and Oversight

State regulators are the primary regulators of nonbanks.[12] States have authority to examine, investigate, and take enforcement action against nonbanks that are chartered or licensed to operate in their respective jurisdictions.[13] States coordinate nonbank supervision through the Conference of State Bank Supervisors, which includes state banking and financial regulators from all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and U.S. territories. In 2021, the Conference approved model prudential standards for nonbank mortgage servicers.[14] As of November 2024, 10 states had wholly or partially adopted these or comparable standards.[15]

Nonbanks generally do not have a federal regulator comprehensively overseeing their safety and soundness.[16] However, a number of federal agencies and the enterprises play a role in monitoring nonbanks.

· Ginnie Mae is a government-owned corporation in the Department of Housing and Urban Development that provides an explicit federal guarantee of the performance of MBS backed by mortgages insured or guaranteed by federal agencies. Ginnie Mae relies on approved financial institutions (issuers) to pool and securitize eligible loans and issue Ginnie Mae-guaranteed MBS. Ginnie Mae’s issuers can service the MBS themselves or hire a third party.

Ginnie Mae is not an independent regulatory agency but sets capital, liquidity, and other eligibility requirements for issuers that participate in Ginnie Mae’s MBS program. Ginnie Mae also conducts compliance reviews of its issuers and, since 2019, has conducted stress tests of its nonbank issuers.[17] If an issuer defaults on its obligations under Ginnie Mae’s MBS program—for instance, by failing to make timely payment of principal and interest to MBS investors—Ginnie Mae can take several actions.[18] These include extinguishing the issuer’s legal or other right to the pooled loans in the Ginnie Mae MBS for which the issuer has responsibility. Ginnie Mae also can seize the issuer’s Ginnie Mae MBS portfolio and service it itself, or permit the transfer of the portfolio to another issuer.

· Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac purchase mortgage loans that meet certain criteria and hold the loans in their portfolios or pool them as collateral for MBS sold to investors. In exchange for a fee, the enterprises guarantee the timely payment of interest and principal on MBS they issue.

The enterprises each set capital, liquidity, and other eligibility requirements for the financial institutions that participate in their MBS programs (known as seller/servicers) and have processes to approve and monitor compliance with these and other program requirements.[19] If a seller/servicer fails to comply with eligibility or other program requirements, the enterprises can take several mitigating actions up to and including suspending or terminating the seller/servicer’s participation in enterprise programs and requiring the transfer of the related enterprise MBS portfolios to another approved seller/servicer.

· FHFA placed the enterprises into conservatorships in September 2008 because of a substantial deterioration in the enterprises’ financial condition. As both conservator and regulator of the enterprises, FHFA has authorities that can help manage risks associated with the enterprises’ nonbank counterparties. For example, in recent years, FHFA issued Advisory Bulletins to the enterprises on valuation of mortgage servicing rights, managing counterparty risk, and oversight of third-party service providers. Since 2021, FHFA has used its conservatorship authority to conduct on-site reviews of several nonbanks.[20]

Other federal entities that monitor or oversee various aspects of nonbanks include FSOC’s nonbank mortgage servicing task force, which includes Ginnie Mae and FHFA and other FSOC members. The task force was established in March 2020 in response to concerns about the financial condition of nonbanks during the COVID-19 pandemic. The task force facilitates interagency coordination and monitors the nonbank market and risks nonbanks pose to U.S. financial stability. Additionally, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau has supervisory and enforcement authority over nonbanks with respect to federal consumer financial protection laws.[21] Finally, federal agencies that insure or guarantee home loans, such as the Federal Housing Administration, conduct some oversight of nonbanks that participate in their programs, such as reviewing and approving lenders and setting financial eligibility requirements.[22]

Agencies Coordinated on Aspects of Nonbank Monitoring but Ginnie Mae’s Involvement in an Interagency Exercise Was Limited

FHFA and Ginnie Mae Have Coordinated on Nonbank Financial Requirements, Nonbank Data, and through an FSOC Task Force

In recent years, FHFA and Ginnie Mae have coordinated on some aspects of nonbank monitoring, as follows.

Financial requirements. In August 2022, FHFA and Ginnie Mae announced a joint update to minimum financial eligibility requirements for companies (including nonbanks) approved as enterprise seller/servicers or Ginnie Mae issuers.[23] Ginnie Mae and the enterprises each set minimum requirements for their counterparties—including net worth, capital, and liquidity criteria—to strengthen the financial capacity of these companies and promote consistency. FHFA and Ginnie Mae previously released separate proposals to update these requirements and obtain industry feedback in 2020 and 2021, respectively. However, at least two industry groups called on the agencies to align these requirements and feedback collection efforts. For example, the Mortgage Bankers Association (a major industry group that represents many nonbanks) cited the compliance costs of having multiple requirements.[24]

To develop the requirements, FHFA and Ginnie Mae officials said they coordinated their analyses, conducted stakeholder outreach, and held a joint listening session with industry groups.[25] Ginnie Mae officials said the agencies shared their quantitative analyses of issuer and seller/servicer financial data to identify requirements needing updates and inform discussions of the final requirements. In April 2022, FHFA and Ginnie Mae held a listening session with 11 groups representing stakeholders on mortgage issues to obtain their feedback on the potential impact of the updated requirements. During the session, the FHFA Acting Director and Ginnie Mae President each commented on the importance of collaboration to enhance consistency in how nonbanks manage their capital and liquidity.

Nonbank financial data. FHFA and Ginnie Mae officials said they regularly meet as part of a consortium that manages financial reporting by nonbanks. This consortium comprises the enterprises, Ginnie Mae, and the Mortgage Bankers Association. Ginnie Mae and the enterprises require their approved nonbank issuers and seller/servicers, respectively, to submit financial data quarterly (monthly for certain large nonbanks) using the Mortgage Bankers Financial Reporting Form. FHFA and Ginnie Mae use these data to monitor nonbanks’ financial condition and risks.

The reporting process is managed by the consortium. Although FHFA is not a formal member, officials said they attend the monthly meetings in their role as the enterprises’ conservator. The officials said these meetings include discussions on improving data quality and usefulness and considering new data fields. For example, in 2020, FHFA worked with the consortium to require that senior nonbank executives attest to the accuracy of their Mortgage Bankers Financial Reporting Form submissions.

FSOC task force. FHFA and Ginnie Mae also coordinated through FSOC’s Nonbank Mortgage Servicing Task Force, analyzing nonbank risks and presenting findings on trends and emerging issues.[26]

In May 2024, based on the task force’s work, FSOC issued a report on the critical role and financial stability risks associated with nonbank mortgage servicers.[27] Among other things, the report stated the following:

· Nonbanks’ heavy reliance on mortgage-related products and services makes them vulnerable to market shocks, potentially causing simultaneous deterioration in their income, balance sheets, and access to credit.

· In an economic stress scenario, nonbanks’ vulnerabilities and interconnections (such as working with the same subservicers or funders) could transmit shocks to the broader mortgage market and financial system.[28] This could harm mortgage borrowers and create large losses for the enterprises, Ginnie Mae, and other credit guarantors.

· Interagency coordination on nonbanks is important given the fragmented oversight structure. The report made recommendations to improve coordination among federal agencies and state regulators.

As of September 2024, the task force was helping coordinate two agency-led initiatives to identify emerging nonbank servicing stresses and to coordinate member agencies’ communication in a stress scenario:

· Monitoring metrics. FHFA officials said the task force has started developing a standard set of metrics—including financial and macroeconomic indicators—to monitor nonbank exposures and emerging trends. Ginnie Mae officials said they have been working with FHFA on this effort.

· Interagency response plan. According to FHFA officials, FHFA and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency are leading development of an interagency plan for how task force agencies will coordinate during a nonbank stress event. Ginnie Mae officials said they have been contributing to the planning process.

Ginnie Mae Made Limited Contributions to an Interagency Planning Exercise and Did Not Develop Lessons Learned

Ginnie Mae participated in an interagency planning exercise for a hypothetical nonbank crisis, but was limited in what it contributed to and drew from the exercise. According to the Department of Homeland Security, tabletop and other scenario-based exercises play a vital role in emergency preparedness and should engage team members and encourage collaboration to manage the response to a hypothetical incident.[29] Such exercises can play a key role in risk management by helping agencies evaluate program plans, procedures, and capabilities for responding to crises.

In October 2023, FHFA organized a tabletop exercise for the FSOC task force to evaluate participants’ processes and preparedness for addressing nonbank stress events or failures. The exercise examined a hypothetical scenario in which a top-five nonbank servicer working with Ginnie Mae and the enterprises was at risk of failure. Participants were to assess their agencies’ internal and external responses at “decision points” by addressing a series of discussion questions. One decision point involved FHFA and Ginnie Mae announcing coordinated risk-mitigation actions to reduce losses on MBS guarantees and protect borrowers. Although the October 2023 exercise was the first and only one conducted by the task force, FSOC’s May 2024 report recommended the continued development of tabletop exercises to prepare for the potential failure of one or more nonbank mortgage servicers.[30]

FHFA documented potential external coordination issues that could arise during a nonbank stress event, which could involve transferring mortgage portfolios from a failing servicer to a new servicer. FHFA noted the importance of coordination and communication with Ginnie Mae, given different Ginnie Mae and enterprise rules for transferring mortgage portfolios and the potential financial impact of the transfers on the new servicer.

FHFA officials also cited internal challenges with ensuring that multiple personnel would be able to quickly access data for decision-making in a crisis. They said these challenges stem from “key person dependency” on one or two staff who conduct analysis. If these staff were unavailable, others could have difficulty locating and updating their analysis. FHFA officials said they have been addressing the issues identified in the tabletop exercise through the ongoing FSOC initiatives and by creating an intranet page with key analysis, data, and contacts that is accessible to multiple analysts. These actions are consistent with FHFA’s objective of identifying risks to the enterprises as part of a strategic goal to secure the safety and soundness of regulated entities.[31]

Ginnie Mae officials said they engaged other agencies during the tabletop exercise. But, in contrast to FHFA, Ginnie Mae did not produce responses to discussion questions to share with others or draw lessons learned for internal use. Ginnie Mae officials cited two reasons for their limited involvement:

· Confidentiality concerns. Officials said they did not produce a response to share with the group because of challenges and potential impacts of sharing nonpublic information. As a counterparty to its approved issuers, Ginnie Mae collects financial, commercial, and other information from issuers, some of which is provided on a confidential basis.[32] Ginnie Mae officials cited legal restrictions, such as the Trade Secrets Act, that may limit their ability to share certain nonpublic, issuer-specific information with FSOC members, which include both federal and state agencies.[33] Ginnie Mae has a policy that provides for the sharing of confidential information with federal agencies. However, Ginnie Mae officials expressed concern that sharing negative information about specific issuers could inadvertently trigger actions by other entities that might create legal risks for Ginnie Mae.[34] The officials also expressed concern that sharing such information could result in the loss of legal privilege.

· Ginnie Mae has its own default planning activities. Ginnie Mae officials said that although they did not produce lessons learned from the FSOC exercise, the agency conducts its own planning activities to increase preparedness for issuer defaults.

While these reasons may affect Ginnie Mae’s level of information sharing or its perceived need to identify lessons learned, Ginnie Mae did not leverage opportunities provided by the exercise to evaluate aspects of interagency coordination or internal planning. For example, Ginnie Mae did not develop responses to exercise discussion questions it could have answered without sharing specific issuer information with others. The questions addressed issues such as

· how the agency ensures it considers possible consequences of an action on external parties;

· what specific information or analysis the agency would need from other agencies, which agency would provide it, and how that information would be used; and

· the processes and authorizations for communicating with other agencies.

Although Ginnie Mae has an issuer default strategy that outlines processes for coordinating with other agencies, its recent default planning activities have not addressed interagency coordination. Ginnie Mae also does not have processes to help ensure that lessons learned from interagency exercises are documented and incorporated into the issuer default strategy.

Ginnie Mae’s limited participation in the FSOC exercise and its lack of processes for interagency exercises did not align with agency goals and strategies. Ginnie Mae officials said their goal in attending the FSOC exercise was to identify gaps in internal procedures during shared situations. However, they did not produce any outputs indicating progress toward achieving that goal. Additionally, Ginnie Mae’s 2022–2026 strategic plan includes the strategies of (1) fostering federal collaboration to provide a leading voice in the housing finance system and to improve coordination and effectiveness and (2) developing programs and practices to reduce disruption and exposure to governmental losses when issuer failures occur.[35] By not developing and sharing responses to the discussion questions cited above, Ginnie Mae did not advance its strategy of fostering federal collaboration and the strategy’s potential benefits of improved coordination and effectiveness. Also, by not developing and incorporating lessons learned from the exercise, Ginnie Mae missed an opportunity to enhance its strategy for managing issuer defaults to help reduce disruption and exposure to losses.

Ginnie Mae may have additional opportunities to advance these strategies because FSOC recommended that the task force continue to hold tabletop exercises. By more fully participating in and developing lessons learned from interagency exercises, Ginnie Mae could enhance planning and coordination on challenges such as ensuring orderly transfers of mortgage servicing and maintaining market stability in a crisis. The agency would also be better positioned to contribute to task force efforts such as developing FSOC’s interagency response plan and scenarios for future tabletop exercises.

Conclusions

The growing role of nonbanks in the housing finance system poses challenges to a federal oversight structure that is divided among multiple entities, including FHFA and Ginnie Mae. These agencies’ recent coordination efforts have helped address these challenges, but Ginnie Mae could contribute more fully to and derive more from interagency tabletop exercises simulating a nonbank crisis. As the 2023 FSOC exercise suggested, this may include considering whether other agencies have market or other data that could inform decision-making and how Ginnie Mae can best communicate with other agencies. And while Ginnie Mae uses internal planning activities to increase preparedness for issuer defaults, it did not use the FSOC exercise in this way.

Developing processes for participating in interagency exercises and for incorporating lessons learned into its issuer default strategy could enhance Ginnie Mae’s coordination with other agencies during an issuer default and improve federal preparedness for a nonbank crisis. Such processes also could help Ginnie Mae navigate the risks and benefits of sharing nonpublic information.

Recommendation for Executive Action

The President of Ginnie Mae should develop processes for participating in interagency exercises—taking into consideration the potential risks and benefits of sharing nonpublic information in a crisis—and for incorporating lessons learned from the exercises into Ginnie Mae’s issuer default strategy. (Recommendation 1)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided FHFA, the Department of Housing and Urban Development, and the Department of the Treasury a draft of this report for their review and comment. FSOC (Treasury) provided comments in an email from its audit liaison and Ginnie Mae (Department of Housing and Urban Development) provided a comment letter reprinted in appendix I. Additionally, all the agencies provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

FSOC noted that Ginnie Mae has been a valued contributor to the Nonbank Mortgage Servicing Task Force and that its participation in the 2023 tabletop exercise helped inform the 2024 FSOC Report on Nonbank Mortgage Servicing.

In its comments, Ginnie Mae neither agreed nor disagreed with our recommendation. Ginnie Mae said it recognized the importance of assessing efforts to monitor nonbanks and referenced its goals for participating in the FSOC task force. Ginnie Mae also stated that its participation in the 2023 tabletop exercise was limited due to information-sharing challenges, as our draft report discussed. Ginnie Mae noted that its monitoring is limited by its role as a government corporation overseeing MBS programs but with no express authority to operate as a regulator of nonbanks. Our draft report contained similar information about Ginnie Mae’s role, including that Ginnie Mae is not an independent regulatory agency but has authorities governing participation in its MBS programs. Additionally, Ginnie Mae said it conducts its own scenario-based exercises and draws lessons learned from them. Our draft report acknowledged these efforts but also noted that recent exercises have not addressed interagency coordination. For this and other reasons, we recommend that Ginnie Mae develop processes for participating in interagency exercises and for incorporating lessons learned from such exercises into its issuer default strategy.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Acting Director of the Federal Housing Finance Agency, the Acting Secretary of the Treasury, the Acting Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact Jill Naamane at 202-512-8678 or NaamaneJ@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix II.

Jill Naamane

Director, Financial Markets and Community Investment

GAO Contact

Jill Naamane, (202) 512-8678 or NaamaneJ@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Steven Westley (Assistant Director), Miranda Berry (Analyst in Charge), Christopher Lee, Marc Molino, Kirsten Noethen, Vincent Patierno, and Barbara Roesmann made significant contributions to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on Facebook, Flickr, X, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our RSS Feeds or Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7700

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, ClowersA@gao.gov, (202) 512-4400, U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7125, Washington, DC 20548

Public Affairs

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, KaczmarekS@gao.gov, (202) 512-4800, U.S.

Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7149

Washington, DC 20548

Strategic Planning and External Liaison

Stephen J. Sanford, Managing

Director, spel@gao.gov, (202) 512-4707

U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7814, Washington,

DC 20548

[1]Nonbank financial institutions offer consumers financial products or services but do not take deposits. In this report, we generally use nonbanks to refer to nonbank mortgage companies (that is, a subset of nonbank financial institutions that engage primarily in activities related to home mortgage loans, including origination and servicing) and focus on mortgages for single-family homes.

[2]Ginnie Mae is a government-owned corporation in the Department of Housing and Urban Development. The enterprises are congressionally chartered, for-profit, shareholder-owned corporations that have been under FHFA conservatorships since 2008. While the enterprises are in conservatorship, the federal government assumes the responsibility for losses they incur.

[3]GAO, Housing Finance System: A Framework for Assessing Potential Changes, GAO‑15‑131 (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 7, 2014).

[4]As nondepository institutions, nonbanks have fewer financial resources than banks on which to draw and depend on short-term funding that may become unreliable during economic downturns.

[5]In this report, we use nonbanks to refer to nonbank mortgage companies approved to participate in Ginnie Mae, Fannie Mae, or Freddie Mac MBS programs.

[6]A tabletop exercise is designed to test existing plans, policies, or procedures for guiding a response to a simulated incident. The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act created FSOC—an interagency council led by the Secretary of the Treasury—to identify risks, promote market discipline, and respond to emerging threats to the stability of the U.S. financial system. Pub. L. No. 111-203, §§ 111-112, 124 Stat. 1376, 1392-1398 (2010). FSOC includes the heads of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Commodity Futures Trading Commission, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Department of the Treasury, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, FHFA, Federal Insurance Office, National Credit Union Administration, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, Office of Financial Research, and Securities and Exchange Commission. Other members include a state banking supervisor, a state insurance commissioner, a state securities commissioner, and an independent member with insurance expertise.

[7]We assessed the reliability of these data by (1) checking the data for outliers and errors, (2) comparing the results of our analysis with other sources, and (3) reviewing prior GAO reliability assessments of the data sources. We determined that the data were sufficiently reliable for describing the federally backed and nonbank shares of the mortgage market.

[8]The enterprises guarantee the timely payment of interest and principal on MBS they issue. While the enterprises are in conservatorship, the federal government assumes the responsibility for the losses they incur. Ginnie Mae provides an explicit federal guarantee of the performance of MBS backed by mortgages insured or guaranteed by federal agencies.

[9]GAO, Nonbank Mortgage Servicers: Existing Regulatory Oversight Could Be Strengthened, GAO‑16‑278 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 10, 2016).

[10]Counterparty risk is the risk that the other party in a transaction may not fulfill its part of the deal and may default on its obligations. For Ginnie Mae and the enterprises, counterparties include their servicers.

[11]This amount represents the unpaid principal balance of loans in agency MBS loan pools.

[12]Conference of State Bank Supervisors, Mortgage Companies – State Authorities (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 1, 2024).

[13]Conference of State Bank Supervisors, Mortgage Companies – State Authorities.

[14]Conference of State Bank Supervisors, Final Model State Regulatory Prudential Standards for Nonbank Mortgage Servicers (Washington, D.C.: July 23, 2021).

[15]Conference of State Bank Supervisors, Nonbank Mortgage Servicer Prudential Standards; accessed December 11, 2024, at https://www.csbs.org/nonbank-mortgage-servicer-prudential-standards.

[16]FSOC has the authority to subject a nonbank financial company to federal prudential supervision if FSOC determines that material financial distress at the company could pose a threat to the nation’s financial stability. 12 U.S.C. § 5323; 12 C.F.R. pt. 1310. FSOC did not identify any nonbank financial companies currently subject to this designation in its December 2024 Annual Report. See Financial Stability Oversight Council, 2024 Annual Report (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 6, 2024).

[17]A stress test is a “what-if” scenario that is not a prediction or expected outcome of the economy but shows the outcome of the model under stressful economic scenarios.

[18]Ginnie Mae can declare an issuer in default for certain specified causes and exercise remedies, in accordance with governing statutes, regulations, and contracts. See, e.g., 12 U.S.C. § 1721(g)(1); 24 C.F.R. § 320.15; Ginnie Mae MBS Guide (5500.3, Rev. 1), ch. 23. Other examples of defaults include impending insolvency, unauthorized use of custodial funds, and submission of false reports.

[19]“Seller/servicer” is the enterprises’ term for institutions approved to sell loans to the enterprises, service enterprise loans, or both.

[20]Federal Housing Finance Agency, Office of the Inspector General, DER Provided Effective Oversight of the Enterprises’ Nonbank Seller/Servicers Risk Management But Needs to Develop Policies and Procedures for Two Supervisory Activities, AUD-2024-003 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 28, 2024).

[21]See, e.g., 12 U.S.C. § 5514.

[22]The Department of Veterans Affairs and the Department of Agriculture’s Rural Housing Service also have mortgage insurance or guarantee programs.

[23]Federal Housing Finance Agency and Ginnie Mae, “FHFA and Ginnie Mae Announce Updated Minimum Financial Eligibility Requirements for Enterprise Seller/Servicers and Ginnie Mae Issuers” (Washington, D.C.: Aug. 17, 2022); see https://www.fhfa.gov/news/news-release/fhfa-and-ginnie-mae-announce-updated-minimum-financial-eligibility-requirements-for-enterprise.

[24]Mortgage Bankers Association, “Request for Input on Eligibility Requirements for Single-Family MBS Issuers” (Washington, D.C.: Aug. 9. 2021); see https://www.mba.org/industry-resources/resource/mba-letter-to-ginnie-mae-on-issues-eligibility-requirements-x283683.

[25]The updated enterprise and Ginnie Mae requirements are not identical because of program differences.

[26]Although Ginnie Mae is not a member of FSOC, it was invited to participate in the task force because of its role in the housing finance system and work with nonbanks. FSOC and Ginnie Mae signed a memorandum of understanding to facilitate Ginnie Mae’s participation in the task force.

[27]Financial Stability Oversight Council, Report on Nonbank Mortgage Servicing (Washington, D.C.: May 10, 2024).

[28]Subservicers perform servicing and loan administration activities (such as payment collection) on behalf of the servicer but do not hold mortgage servicing rights. Funders refer to the companies that provide financing to nonbanks, generally from lines of credit provided by banks, bank affiliates, and private lenders.

[29]Emergency preparedness can include planning for and simulation of a range of threats, including threats to financial sectors. Homeland Security defines preparedness as a continuous cycle of planning, organizing, training, equipping, exercising, evaluating, and taking corrective action to help ensure effective coordination during incident response. Tabletop exercises are one example of exercises suited for emergency preparedness. Other exercises include walkthroughs, workshops, education seminars, functional exercises, and full-scale exercises.

[30]Financial Stability Oversight Council, Report on Nonbank Mortgage Servicing.

[31]Federal Housing Finance Agency, Strategic Plan Fiscal Years 2022–2026 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 14, 2022). The objective includes a related strategy of monitoring industry trends and emerging risks to inform risk assessments and adjust supervisory approaches where appropriate.

[32]For example, see Ginnie Mae’s MBS Guide (5500.3, Rev. 1), app. IV-1 (permitting issuers to label certain data as confidential commercial or financial information exempt from public disclosure), app. V-1, ch. 8 (describing Ginnie Mae's obligations to safeguard privileged or confidential commercial or financial information and business practices), app. VIII-1 (providing confidential treatment for certain information pertaining to the pledge of mortgage servicing rights), and app. XI-01B (the Department of Housing and Urban Development will protect confidential information submitted in connection with a COVID-19 assistance program against public disclosure).

[33]The Trade Secrets Act, as amended, prohibits federal agencies from disclosing certain types of information—such as trade secrets and confidential commercial or financial information—unless authorized by law. 18 U.S.C. § 1905. See, e.g., McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Widnall, 57 F.3d 1162, 1164 (D.C. Cir. 1995).

[34]FSOC’s May 2024 report recommended Congress consider legislation that would (1) authorize Ginnie Mae, and encourage state regulators, to share information with each other and with FSOC member agencies to facilitate coordination; and (2) ensure that the sharing of confidential information would not result in the loss of any applicable privilege or confidentiality protections. As of December 2024, Congress had not enacted legislation to explicitly implement that recommendation. Our report focuses on actions Ginnie Mae may be able to take under its existing authorities and confidentiality policies.

[35]Ginnie Mae, Creating A More Accessible & Inclusive Housing Finance System: Ginnie Mae Strategic Plan 2022–2026 (Washington, D.C.). These strategies correspond to Ginnie Mae’s strategic goals of strengthening the MBS program and managing program risk, respectively.