COAST GUARD

Arctic Risks Assessed, but Information Gaps and Numerous Challenges Threaten Operations

Statement of Heather MacLeod, Director, Homeland Security and Justice

Testimony

Before the Subcommittee on Coast Guard and Maritime Transportation, Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, House of Representatives

For Release on Delivery Expected at 11:00 a.m. ET

Thursday, November 14, 2024

GAO-25-107910

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Heather MacLeod at (202) 512-8777 or macleodh@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑107910, a testimony before the Subcommittee on Coast Guard and Maritime Transportation, Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, House of Representatives

November 14, 2024

COAST GUARD

Arctic Risks Assessed, but Information Gaps and Numerous Challenges Threaten Operations

Why GAO Did This Study

Since the Arctic is largely a maritime domain, the U.S. Coast Guard, a multi-mission military service within the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), plays a key role in Arctic policy implementation and enforcement. As more navigable ocean water has emerged and human activity increases in the region, the Coast Guard faces growing responsibilities to assess and manage risks. These include risks to maritime safety, security, and the environment.

This statement discusses: (1) Coast Guard actions to assess and mitigate risks in the Arctic region, and (2) key challenges the Coast Guard faces that may affect its Arctic operations and its ability to meet its strategic commitments.

This statement is based primarily on our 2024 report examining Coast Guard Arctic operational risks, and our 2023 report on Coast Guard acquisitions. This statement also includes updated 2024 data on the Coast Guard’s shore infrastructure backlog. For the reports cited in this statement, GAO analyzed Coast Guard and Department of Defense documentation and data, and interviewed officials from these agencies.

What GAO Recommends

GAO has made more than 30 recommendations since 2016 to the Coast Guard and DHS in reports on Coast Guard Arctic operations, acquisition, and shore infrastructure issues. As of November 2024, 19 remain open. GAO continues to monitor progress on these recommendations.

What GAO Found

The Coast Guard has assessed risks that affect its ability to carry out its missions in the U.S. Arctic region, such as those posed by increased maritime activity and by potential adversaries such as Russia and China. It has partnered with the Department of Defense and others to mitigate these risks and included this information in planning documents. These plans include the Coast Guard’s Arctic strategy and its implementation plan. However, the implementation plan does not include key metrics such as performance measures, targets, or timeframes for action items. This may make it difficult for the Coast Guard to determine resource needs, assess progress toward strategic objectives, and ensure its efforts are aligned with national Arctic efforts. GAO also found that key mission performance information was incomplete or missing, such as the number of days ships were deployed in the Arctic region and the time they spent on various missions there.

The Coast Guard has multiple strategic commitments for its Arctic operations but has been unable to meet all of them in recent years in part due to asset availability challenges. These include a lack of icebreakers, and competing demands for major cutters elsewhere. Further, limited infrastructure and logistics capabilities in Alaska amplify asset challenges in the Arctic region. The Coast Guard is making efforts to address them via major acquisition projects, such as for the new Polar Security Cutter, but these ships continue to face significant delays and cost issues. Since 2016, GAO has issued several reports and made numerous recommendations to improve Coast Guard Arctic planning and acquisition programs.

The Coast Guard uses its shore infrastructure assets—such as piers and maintenance buildings—to support legacy assets that operate in the Arctic region, such as icebreakers and other cutters. In 2019, GAO found that the estimated cost of the Coast Guard’s shore infrastructure project backlog totaled at least $2.6 billion. GAO made six recommendations to address these issues, two of which the Coast Guard has fully implemented. However, as of November 2024, GAO’s preliminary analysis showed that the estimated cost of this shore infrastructure backlog had more than doubled to over $7 billion.

November 14, 2024

Chairman Webster, Ranking Member Carbajal, and Members of the Subcommittee

Thank you for the opportunity to discuss our work on the U.S. Coast Guard’s risks and challenges in the Arctic.[1] As an Arctic nation, the United States has substantial security and economic interests in the region. Current geopolitical trends indicate that it is growing more important to the United States, its allies, and strategic adversaries.[2] In recent years, there has been an escalation of competition among the United States, Russia, and China in the region. The effects of climate change, technological advancements, and economic opportunities have also driven increased interest and activity in the region, which has increased maritime activity and risks.

Since the Arctic is largely a maritime domain, the U.S. Coast Guard, a multi-mission military service within the Department of Homeland Security plays a key role in Arctic policy implementation and enforcement. As more navigable ocean water has emerged and human activity increases in the region, the Coast Guard faces growing responsibilities to assess and manage risks there, including those posed to maritime security, safety, and the environment. These include, among others, (1) security risks from increased militarization of the Arctic region and potential conflict with Russia or China; (2) safety risks from more frequent and intense winter storms and greater shipping traffic; and (3) environmental risks, such as coastal erosion and oil spills.

My statement today addresses (1) the Coast Guard’s actions to assess and mitigate risks in the Arctic region, and (2) key challenges the Coast Guard faces that may affect its Arctic operations and its ability to meet its strategic commitments.

This statement is based primarily on our 2024 report examining the Coast Guard’s efforts to plan for and mitigate its Arctic operational risks and our 2023 report on Coast Guard acquisitions that could affect its Arctic operations.[3] This statement also includes data on the Coast Guard’s shore infrastructure backlog that we previously reported on in 2019, as well as updated data from 2024.[4] For the reports cited in this statement, we analyzed Coast Guard and Department of Defense documentation and data, and interviewed officials from these agencies, among other methodologies. More detailed information on our scope and methodology can be found in the reports cited in this statement.

Since 2016, we have made 38 recommendations to the Coast Guard and the Department of Homeland Security in reports related to Coast Guard Arctic operations, acquisition, and shore infrastructure issues.[5] As of November 2024, 15 of 38 recommendations have been implemented and 19 remain open.[6] We will continue to monitor the Coast Guard’s progress in implementing them.

We conducted the work on which this statement is based in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

The Coast Guard Has Assessed and Taken Steps to Mitigate Arctic Risks but Lacks Complete Information to Inform Its Efforts

The Coast Guard Has Identified and Assessed Arctic Risks and Collaborates with Federal and Regional Partners to Mitigate Them

The Coast Guard has identified and assessed risks—such as those posed by climate change and increased maritime activity—that affect its ability to carry out its missions in the Arctic region and incorporated this information in various planning documents. These documents include the Coast Guard’s 2019 Arctic Strategic Outlook (Coast Guard Arctic strategy), its 2023 Arctic Strategic Outlook Implementation Plan (Coast Guard Arctic implementation plan), and other region-specific documents that identify risks specific to their areas of operation.[7] For example, the Coast Guard Arctic strategy notes that Russia seeks to consolidate sovereign claims and control access to the region while China aims to gain access to Arctic resources and sea routes to secure and bolster its military, economic, and scientific rise.

The Coast Guard and Department of Defense collaborate to mitigate risks in the Arctic in several ways, including sharing relevant information and expertise and providing operational assistance. Officials from both agencies told us they collaborated on the development of their respective Arctic strategies, work with one another to maintain Arctic maritime domain awareness, and participate in joint exercises in the region.[8] For example, the Coast Guard provides standby search and rescue support for Operation Arctic Edge, the Department of Defense’s joint biennial exercise with the Canadian Armed Forces.

The Coast Guard’s collaboration to develop region-specific documents has generated maritime security plans and contingency plans for its field units that identify various risks specific to their operations in the Arctic region and elsewhere, among other efforts.[9] To develop these plans, the Coast Guard collaborates through various committees, which may include maritime industry stakeholders; federal, state, territorial or Tribal governments; and others, to identify security and marine environmental risks.

The Coast Guard’s Arctic Implementation Plan Lacks Key Performance Information

The Coast Guard Arctic implementation plan outlines initiatives and actions that it intends to take to achieve the strategic objectives identified in the Coast Guard Arctic strategy. However, we found in August 2024 that the plan generally does not include key metrics such as performance measures, targets, or time frames for action items.[10] This may make it difficult for the Coast Guard to plan activities, determine resource needs, assess its progress toward strategic objectives, and ensure its efforts are aligned with national efforts. As a result, we recommended that the Coast Guard include performance measures with associated targets and time frames in its implementation plan. The Coast Guard concurred with our recommendation, and we continue to monitor its progress.

The Coast Guard Has Taken Steps to Mitigate Arctic Operational Challenges, but Lacks Key Planning Data

The Coast Guard has taken steps to mitigate the effects on its missions resulting from its limited available assets. For example, the Coast Guard forward deploys cutters and helicopters into the U.S. Arctic region seasonally to reduce transit and response times, which helps to mitigate the effects of having limited assets available for Arctic missions. Similarly, the Coast Guard annually deploys its medium polar icebreaker, the Healy, to the Arctic region in support of national objectives and research efforts for several federal agencies. This deployment provides additional seasonal presence in the region that helps to mitigate operational risks. However, the Healy’s ability to carry out its annual planned deployments has been limited in recent years in part due to fires onboard the ship in 2020 and 2024.

In August 2024, we reported that key Coast Guard mission performance information was incomplete or missing, such as the number of days that cutters were deployed and the time they spent on various missions in the region.[11] Specifically, from fiscal years 2016 through 2023, Coast Guard operational performance reports were either partially complete, incomplete, or unavailable, for reasons such as losses during data migrations and shortages of qualified personnel, according to Coast Guard officials.[12] These performance reports noted that data system limitations may also have affected the accuracy of resource hour use and mission performance data.

The Coast Guard’s performance reports are a key input in its operational planning process because they enable the service to quantitatively assess its mission performance, identify capability gaps, and forecast future operational requirements. Accordingly, in August 2024 we recommended that the Coast Guard collect and report complete information about resource use and mission performance in accordance with its guidance. This would better position the service to monitor its activity and make more informed operational planning decisions for the Arctic region. The Coast Guard concurred with our recommendation, and we continue to monitor its progress.

The Coast Guard Faces Asset and Infrastructure Challenges That May Affect Its Ability to Carry Out Arctic Operations and Meet Strategic Commitments

The Coast Guard has multiple strategic commitments for operations in the U.S. Arctic region but has been unable to meet all of them in recent years for various reasons.[13] According to the Coast Guard, these include asset availability challenges, such as a lack of reserve major cutters, and competing demands for major cutters in other areas such as the Indo-Pacific region, among other factors.[14] Further, limited infrastructure and logistics capabilities in Alaska amplify asset availability challenges. Efforts to address these challenges in the long term via major acquisitions, such as the Polar Security Cutter program, continue to face significant delays. This program also faces a pending cost increase that puts pressure on the Coast Guard’s resource-constrained acquisition budget. At the same time, the Coast Guard has a backlog of shore infrastructure projects that is contributing to affordability concerns for recapitalization and related efforts to sustain existing and planned assets. Collectively, these factors will continue to limit the operational availability of Coast Guard assets in the Arctic region, jeopardizing the service’s ability to meet its Arctic strategy goals and conduct planning efforts to address known capability gaps.

The Coast Guard’s Polar Security Cutter Program Continues to Experience Significant Schedule Delays and Pending Cost Increases

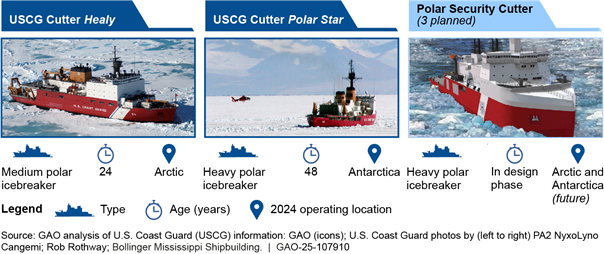

To address operational challenges and meet its strategic commitments in the Arctic, the Coast Guard plans to acquire three new Polar Security Cutters capable of traversing the Arctic and Antarctic regions (see fig. 1).[15] These ships will be the first heavy polar icebreakers that any U.S. government agency has acquired in almost 50 years.[16] However, until these ships are fully operational, the Coast Guard has assessed that it currently does not have the capability to assure continuous presence and reliable access to the Arctic.

Since 2016, we have issued several reports and made 27 recommendations addressing the status of Coast Guard acquisition programs, including seven recommendations related to the Polar Security Cutter program, which is at least 4 years behind schedule.[17] Our prior work found that four primary factors contributed to the Polar Security Cutter program delays, according to program officials: (1) lack of shipbuilder experience designing and building polar icebreakers; (2) complexity of the design; (3) significant changes from the original design; and (4) COVID-19 pandemic impacts.[18] As of April 2024, the program had not yet established an updated schedule. A preliminary draft schedule projected a lead ship delivery by the end of 2029.

The Polar Security Cutter program has also been subject to significant cost growth, with the full extent yet to be determined. As of 2023, the Coast Guard planned to invest about $3 billion to acquire the three Polar Security Cutters and $9 billion to maintain them.[19] However, in November 2023, based on updated cost data, the program determined it required additional funding of at least $600 million (or 20 percent) above its previous threshold.[20] Moreover, an April 2024 Congressional Budget Office estimate showed costs for the program, not including maintenance, increasing by over 60 percent, to $5.1 billion. As we previously reported, the issues affecting the Polar Security Cutter program raise questions about scheduled delivery of these ships, as well as the affordability of this program in a constrained budget environment.[21]

In the interim period before its fleet of new polar icebreakers are complete, the Coast Guard anticipates it will have a reduced number of ships available for Arctic operations. To mitigate this, the Coast Guard is relying on its aged fleet of existing polar icebreakers. While these ships have generally maintained operations, their continued use increases the risk they will fail before they are replaced. For example, the Coast Guard is annually accomplishing its Antarctic mission with its sole existing heavy polar icebreaker, the Polar Star, which is 48 years old and well beyond its 30-year service life. However, there is no backup if the Polar Star becomes inoperable before the Polar Security Cutters are delivered. We have an ongoing review that discusses the Coast Guard’s role and how its current polar icebreakers enable it to operate in the Arctic; how the Coast Guard analyzed its polar icebreaking needs; and the extent to which it has considered options to expand the future fleet. We expect to issue a report on the results of this review in fall 2024.

The Estimated Cost of the Coast Guard’s Backlog of Shore Infrastructure Projects Has More than Doubled Since 2019

The Coast Guard uses its shore infrastructure assets—such as piers, maintenance buildings, and warehouses—to support legacy assets such as polar icebreakers and other major cutters that operate in the Arctic region. However, the estimated cost of the Coast Guard’s shore infrastructure project backlog has more than doubled since 2019, according to our preliminary 2024 analysis. In February 2019, we found that the Coast Guard had a backlog of shore infrastructure projects related to docks, air stations, and other assets that totaled at least $2.6 billion. We made six recommendations to address these issues, two of which the Coast Guard has fully implemented.[22] However, as of November 2024, our preliminary analysis of Coast Guard data found that the estimated cost of this backlog exceeded $7 billion and included over 1,900 recapitalization, new major construction, and deferred maintenance projects.[23] Moreover, our analysis of the Coast Guard’s fiscal year 2024 shore infrastructure project list found that 235 of the projects lacked cost estimates, making it difficult to determine the costs of addressing many of these projects.[24]

In conclusion, the Coast Guard faces growing responsibilities to assess and manage risks to safety and security in the Arctic region as conditions continue to change. The Coast Guard has taken actions to manage these risks by including them in strategic planning documents and deploying cutters and aircraft to the U.S. Arctic region during peak maritime activity. The Coast Guard has also initiated plans to acquire new polar icebreakers to enhance its capabilities in the region. However, the Coast Guard Arctic implementation plan—a key planning document used to inform its efforts in the region—does not include key metrics that would help the Coast Guard plan activities, determine resource needs, and assess its progress toward strategic objectives. Further, continued delays in delivering the Polar Security Cutter increase the likelihood of operational capability gaps in the region. As we previously reported, the Coast Guard faces service-wide limitations that can affect its ability to plan for, and meet, its strategic commitments in the Arctic region and throughout its operating domain. Implementation of our recommendations would help the Coast Guard manage its Arctic-related resource needs. It would also help ensure that the service makes progress toward achieving its strategic objectives and remains aligned with national Arctic priorities.

Chairman Webster, Ranking Member Carbajal, and Members of the Subcommittee, this completes my prepared statement. I would be pleased to respond to any questions that you may have at this time.

GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments

If you or your staff have any questions about this testimony, please contact Heather MacLeod, Director, Homeland Security and Justice at (202) 512-8777 or MacLeodH@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this statement. GAO staff who made key contributions to this testimony are Dawn Hoff (Assistant Director), Jason Blake (Analyst-in-Charge), Patrick Breiding, Andrew Curry, Bethany Gracer, Phoebe Iguchi, Claire Li, Samantha Lyew, James Madar, Amanda Miller, and Ben Nelson. Other staff who made key contributions to the reports cited in the testimony are identified in the source products.

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

GAO’s Mission

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on Facebook, Flickr, X, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our RSS Feeds or Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what‑gao‑does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7700

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, ClowersA@gao.gov, (202) 512-4400, U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7125, Washington, DC 20548

Public Affairs

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, KaczmarekS@gao.gov, (202) 512-4800, U.S.

Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7149

Washington, DC 20548

Strategic Planning and External Liaison

Stephen J. Sanford, Managing

Director, spel@gao.gov, (202) 512-4707

U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7814, Washington,

DC 20548

[1]In general, the Arctic is the polar region located at the northernmost part of the Earth. Arctic stakeholders define the Arctic geographical area in different ways. For example, the Arctic Research and Policy Act of 1984 defined the Arctic as all United States and foreign territory north of the Arctic Circle and all United States territory north and west of the boundary formed by the Porcupine, Yukon, and Kuskokwim Rivers (in Alaska); all contiguous seas, including the Arctic Ocean and the Beaufort, Bering, and Chukchi Seas; and the Aleutian chain. Pub. L. No. 98-373, tit. I, § 112, 98 Stat. 1242, 1248 (codified at 15 U.S.C. § 4111). The Arctic Circle is the line of latitude located at 66° 33’ 44” north of the equator. Other definitions of the Arctic use markers such as the southernmost extent of winter sea ice for oceanic boundaries or the northernmost tree line for terrestrial boundaries.

[2]GAO, Arctic Region: Factors That Facilitate and Hinder the Advancement of U.S. Priorities, GAO‑23‑106002 (Washington, D.C.: September 6, 2023).

[3]See GAO, Coast Guard: Complete Performance and Operational Data Would Better Clarify Arctic Resource Needs, GAO‑24‑106491 (Washington, D.C.: Aug. 13, 2024); GAO, Coast Guard Acquisitions: Polar Security Cutter Needs to Stabilize Design Before Starting Construction and Improve Schedule Oversight, GAO‑23‑105949 (Washington, D.C.: July 27, 2023).

[4]The Coast Guard uses a variety of shore infrastructure assets, such as piers, maintenance buildings, and warehouses, to support its missions. We previously reported on the Coast Guard’s backlog of construction and improvement projects within its shore infrastructure portfolio. See GAO, Coast Guard Shore Infrastructure: Applying Leading Practices Could Help Better Manage Project Backlogs of at Least $2.6 Billion, GAO‑19‑82 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 21, 2019).

[5]See GAO‑24‑106491; GAO, Coast Guard: Improved Reporting on Domestic Icebreaking Performance Could Clarify Resource Needs and Tradeoffs, GAO‑24‑106619 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 16, 2024); GAO‑23‑105949; GAO, Coast Guard Acquisitions: Offshore Patrol Cutter Program Needs to Mature Technology and Design, GAO‑23‑105805 (Washington, D.C.: June 20, 2023); GAO, Coast Guard Acquisitions: Opportunities Exist to Reduce Risk for the Offshore Patrol Cutter Program, GAO‑21‑9 (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 28, 2020); GAO‑19‑82; GAO, Coast Guard Acquisitions: Polar Icebreaker Program Needs to Address Risks before Committing Resources, GAO‑18‑600 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 4, 2018); GAO, Coast Guard Acquisitions: Actions Needed to Address Longstanding Portfolio Management Challenges, GAO‑18‑454 (Washington, D.C.: July 24, 2018); GAO, Coast Guard: Status of Polar Icebreaking Fleet Capability and Recapitalization Plan, GAO‑17‑698R (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 25, 2017); GAO, Coast Guard: Arctic Strategy Is Underway, but Agency Could Better Assess How Its Actions Mitigate Known Arctic Capability Gaps, GAO‑16‑453 (Washington, D.C.: June 15, 2016); and GAO, National Security Cutter: Enhanced Oversight Needed to Ensure Problems Discovered during Testing and Operations Are Addressed, GAO‑16‑148 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 12, 2016).

[6]We closed four recommendations related to the Coast Guard’s acquisition efforts for cutter assets. They were overcome by events and thus were no longer valid.

[7]U.S. Coast Guard, United States Coast Guard Arctic Strategic Outlook (Washington, D.C.: April 2019) and United States Coast Guard Arctic Strategic Outlook Implementation Plan (Washington, D.C.: October 2023).

[8]According to the Coast Guard, maritime domain awareness is the effective understanding of anything associated with the global maritime domain that could affect the United States’ security, safety, economy, or environment. Per the National Strategy for the Arctic Region and its accompanying implementation plan, the Department of Defense is to lead efforts to modernize systems that detect and track potential airborne and maritime threats, and the Coast Guard is to support the department’s efforts. The Coast Guard is to provide effective maritime security, law enforcement, search and rescue, and emergency response, and expand its icebreaker fleet to support increased presence in the Arctic. The Department of Defense is to support these efforts.

[9]These plans include, for example, Area Maritime Security Plans, which identify critical port infrastructure, operations, and security risks, and determine mitigation strategies and implementation methods, and Area Contingency Plans, which identify plans for oil and hazardous substance spill response, incident management, and all-hazards preparedness.

[12]When we evaluated the reports, “complete” meant that elements of the performance reports contained complete resource hour or mission performance data for all missions executed in Coast Guard field units. “Partially complete” meant that elements of the performance reports contained data for some missions but not others. “Incomplete” meant that elements of the performance reports lacked data for all missions. “Unavailable” meant that we could not evaluate performance reports because the Coast Guard could not provide those reports.

[13]For example, the Coast Guard has maintained a strategic commitment to have a 365-day major cutter presence in U.S. Arctic waters, specifically the Bering Sea. However, it has not always been able to meet this commitment recently due to asset availability challenges. Specifically, in fiscal year 2022, mechanical problems prevented the Coast Guard from deploying a major cutter to the Bering Sea as planned, resulting in a 27-day coverage gap. To help address these types of gaps, the Coast Guard plans to acquire 28 new cutters, including at least 3 new icebreakers.

[14]GAO‑24‑106491. Coast Guard officials also cited the COVID-19 pandemic and environmental factors, such as the presence of sea ice that can limit major cutter access to areas north of the Bering Strait, as other factors affecting the Coast Guard’s ability to meet its strategic commitments in the Arctic.

[15]In addition to these three new heavy polar icebreakers, the James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 includes a provision that authorized $150 million for the acquisition or procurement of a United States built available icebreaker. See Pub. L. No. 117-263, div. K, tit. CXI, § 11104(a)(5), tit. CXII, subtit. C, § 11223(a), 136 Stat. 2395, 4004, 4021. The Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2024 includes a provision appropriating over $1.41 billion for necessary expenses of the Coast Guard for procurement, construction, and improvements, including vessels and aircraft. See Pub. L. No. 118-47, div. C, tit II, 138 Stat. 460, 600. The joint explanatory statement for the act includes a provision specifying that $125 million is provided for procurement of a commercially available polar icebreaker. See Staff of H.R. Comm. on App., 118th Cong., Joint Explanatory Statement for Division C—Department of Homeland Security Appropriations Act 31 (Comm. Print 2024).

[16]The Coast Guard’s current polar icebreaking fleet comprises two operational polar icebreakers—the Polar Star and Healy. The Polar Star, a heavy icebreaker, has operated in the Arctic. For example, in 2021, it went to the Arctic to support science missions. However, only the Healy is currently active and operating in the Arctic. The Healy is a medium icebreaker that primarily supports Arctic research. While it is capable of carrying out a wide range of activities, it cannot ensure timely access to some Arctic areas in the winter given that it does not have the icebreaking capabilities of a heavy polar icebreaker. An additional Coast Guard heavy icebreaker, the Polar Sea, has been inactive since 2010 when it experienced a catastrophic engine failure.

[17]See GAO‑23‑105949; GAO‑23‑105805; GAO‑21‑9; GAO‑18‑600; GAO‑18‑454; GAO‑17‑698R; and GAO‑16‑148.

[19]The Coast Guard also plans to procure a Great Lakes heavy icebreaker to augment its only heavy domestic icebreaker in the region. We recently reported on the Coast Guard’s domestic icebreaking capability; see GAO‑24‑106619.

[20]GAO, Coast Guard Acquisition: Actions Needed to Address Affordability Challenges, GAO‑24‑107584 (Washington, D.C.: June 12, 2024).

[21]See GAO‑24‑107584; GAO, Coast Guard Acquisitions: Opportunities Exist To Improve Shipbuilding Outcomes, GAO‑24‑107488 (Washington, D.C.: May 7, 2024); and GAO, Coast Guard Recapitalization: Actions Needed To Better Manage Acquisition Programs And Address Affordability Concerns, GAO‑23‑106948 (Washington, D.C.: July 27, 2023).

[23]These include projects for the acquisition, procurement, construction, rebuilding, and improvement of Coast Guard buildings such as military housing or cutter support facilities, as well as maintenance on structures such as aircraft hangars or boat docks.

[24]We have an ongoing review that updates our 2019 work on the Coast Guard’s shore infrastructure portfolio. We expect to issue a report on the results of this review in 2025.