UKRAINE

DOD Can Take Additional Steps to Improve Its Security Assistance Training

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑107923. For more information, contact Diana Maurer at (202) 512-9627 or maurerd@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑107923, a report to congressional committees

DOD Can Take Additional Steps to Improve Its Security Assistance Training

Why GAO Did This Study

In response to Russia’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine, DOD has received about $111 billion for assistance to Ukraine and related activities. DOD used a portion of this assistance to train Ukrainian forces.

GAO initiated this review in response to a provision in Division M of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023. This report addresses (1) processes DOD has used to provide training on defense articles to Ukrainian forces and the associated challenges; and (2) approaches DOD has used to assess the training and share lessons learned, among other issues.

GAO reviewed DOD documents on security assistance processes, examined training assessments and lessons learned results, and reviewed training range and readiness data.

What GAO Recommends

GAO recommends that DOD (1) issue guidance to ensure that combatant commands identify training resource needs when proposing a security assistance package, (2) document the processes to assess training of Ukrainian forces, and (3) ensure that organizations capture and share relevant training observations through the Joint Lessons Learned Information System. DOD agreed with the second and third recommendations, but did not agree with the first recommendation, stating that an existing DOD directive has guidance to identify training needs. GAO believes the recommendation remains valid because DOD’s guidance has gaps that hindered DOD’s planning for training needs.

What GAO Found

Between February 2022 and April 2024, the Department of Defense (DOD) trained Ukrainian military personnel—mainly at U.S. training ranges in Germany—using various security assistance processes. Much of this training accompanied defense articles that DOD provided to Ukraine under Presidential Drawdown Authority (PDA). However, the expanded size, scope, and speed of equipment deliveries to Ukraine contributed to training challenges. GAO found that U.S. Army units initially experienced disruptions delivering training due to

· insufficient training equipment,

· limited training preparation time,

· inadequate support resources to repair training equipment, and

· mismatches between Ukraine’s training needs and U.S. trainer expertise.

U.S. Army officials told GAO they overcame these challenges by adapting training schedules and obtaining contractor support, among other strategies. By issuing additional guidance to ensure that combatant commands identify training needs when proposing a security assistance package, DOD would be better positioned to avoid challenges that might disrupt associated training. This is especially relevant for future situations that require the rapid execution of PDA.

DOD components that are responsible for overseeing and administering training to Ukrainian forces have used several approaches to assess trends and identify improvement opportunities. However, GAO found that data challenges hindered DOD’s assessment approaches (see figure). Providing clear guidance on documenting the approaches used to assess training provided Ukrainian forces would position DOD to make more effective decisions on training in the future.

DOD components also have not consistently recorded observations from training Ukrainian forces in the Joint Lessons Learned Information System, as required by DOD policy. GAO found that this requirement was not reflected in most of the implementing orders that govern the U.S. military’s efforts to train Ukrainian forces. As a result, DOD’s lessons learned may not be comprehensive or timely, leading to missed opportunities for improvement.

This is a public version of a sensitive report GAO issued in November 2024. It omits (1) sensitive information and data related to the number of Ukrainians that DOD trained, (2) challenges and readiness effects that U.S. Army units experienced when providing the training, and (3) factors that hindered DOD components’ ability to assess training provided to Ukrainian forces.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

7th ATC |

7th Army Training Command |

|

Abrams tank |

M1A1 Abrams Tank |

|

Armored Personnel Carrier |

M113 Armored Personnel Carrier |

|

ARNG |

Army National Guard |

|

Bradley Fighting Vehicle |

M2 Bradley Fighting Vehicle |

|

DOD |

Department of Defense |

|

DSCA |

Defense Security Cooperation Agency |

|

Grafenwoehr |

Grafenwoehr Training Area |

|

JMTG-U |

Joint Multinational Training Group – Ukraine |

|

Paladin |

M109 Paladin Self-Propelled Howitzer |

|

PDA |

Presidential Drawdown Authority |

|

SAG-U |

Security Assistance Group–Ukraine |

|

Stryker |

M1126 Stryker Infantry Carrier Vehicle |

|

TF |

Task Force |

|

USAI |

Ukraine Security Assistance Initiative |

|

V Corps |

U.S. Army Fifth Corps |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

January 28, 2025

Congressional Committees

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 has had devastating consequences, threatening a democratic country’s sovereignty and creating a humanitarian crisis in Europe. In response, as of May 2024 a series of five Ukraine supplemental appropriation acts provided $174.2 billion to help combat Russian aggression and to preserve Ukraine’s territorial integrity.[1] The Department of Defense (DOD) received more than 60 percent of the supplemental funding—$110.7 billion—for security assistance to Ukraine and for activities to assure allies and deter further Russian aggression.[2]

A portion of the assistance the U.S. has provided to Ukraine is designated to support various types of training for Ukrainian forces, including training to operate and maintain defense articles.[3] Prior to Russia’s 2022 invasion, DOD provided training, mentoring, and doctrinal development to Ukraine both inside and outside of Ukraine. Since April 2022, DOD has trained Ukrainian personnel in Germany and other locations in Europe and the U.S..[4] The U.S. has used this training to help Ukraine develop and reconstitute units to perform complex operations using different defense articles in concert, often referred to as combined arms operations.

We initiated several engagements in response to a provision included in the Consolidated Appropriations Act for Fiscal Year 2023, which provided resources for us to exercise oversight of the funding provided in the Ukraine supplemental appropriations acts.[5] This report (1) describes the processes DOD has used to provide Ukrainian forces with training on defense articles and examines the challenges DOD experienced when providing this training, (2) evaluates the approaches DOD has used to assess the training it has provided to Ukrainian forces and to document and disseminate lessons learned since the Russian invasion, and (3) describes the effect that the training of Ukrainian forces has had on DOD’s European training facilities and the readiness of U.S. units that supported that training.[6]

This report is a public version of the prior sensitive report that we issued in November 2024.[7] DOD deemed some of the information in the prior report as Controlled Unclassified Information (CUI), which must be protected from public disclosure. Therefore, this report omits (1) CUI information and data related to the number of Ukrainians that DOD trained, (2) challenges and readiness effects that U.S. Army units experienced when providing the training, and (3) factors that hindered DOD components’ ability to assess training provided to Ukrainian forces. Although the information provided in this report is more limited in scope, it addresses the same objectives as the sensitive report. Also, the methodology used for both reports is the same.

To address these objectives, we reviewed training that DOD provided to conventional Ukrainian forces as security assistance between April 2022 and January 2024 at U.S. training areas in Europe. Specifically, we reviewed DOD training for defense articles, collective training for combined arms operations, and leadership. To address our first objective, we examined DOD’s processes for training Ukrainian forces primarily through Presidential Drawdown Authority (PDA) and the Ukraine Security Assistance Initiative (USAI).[8] We used a set of criteria to select five defense articles—M1A1 Abrams Tank, M113 Armored Personnel Carrier, M2 Bradley Fighting Vehicle, M109 Paladin Self-Propelled Howitzer, and M1126 Stryker Infantry Carrier Vehicle—as illustrative examples to gather in-depth information.[9] We interviewed officials to identify challenges DOD encountered with its training efforts. We compared DOD’s planning and implementation of training with DOD security assistance guidance, such as the Defense Security Cooperation Agency’s Security Assistance Management Manual.[10]

To address our second objective, we reviewed programs of instruction, training directives, and assessment tools DOD used to train Ukrainian forces since February 2022. We also reviewed DOD efforts to capture lessons learned from training Ukrainian forces and interviewed DOD officials responsible for sharing those lessons learned. We compared DOD’s effort to assess training for Ukrainian forces with DOD’s security assistance guidance and we evaluated DOD’s lessons learned efforts considering requirements established in a joint staff instruction.[11]

To address our third objective, we reviewed data from January 2021 to January 2024 from DOD’s training range scheduling system for Grafenwoehr Training Area (hereafter Grafenwoehr). We selected this training area for our analysis because DOD officials explained that most of the U.S. training provided to conventional Ukrainian forces occurred at this location. We determined the data were sufficiently reliable for the purpose of reporting range usage trends at Grafenwoehr. Additionally, we analyzed readiness information from DOD’s Defense Readiness Reporting System and interviewed officials and collected information from selected units that U.S. Army Europe and Africa identified as having trained Ukrainian forces since February 2022 to determine any readiness effects. See appendix I for a detailed description of our scope and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from April 2023 to November 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards.[12] Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We subsequently worked with DOD from December 2024 to January 2025 to prepare this public version of the original sensitive report for public release. This public version was also prepared in accordance with these standards.

Background

Key DOD Organizations with a Responsibility for Providing Security Assistance to Ukraine

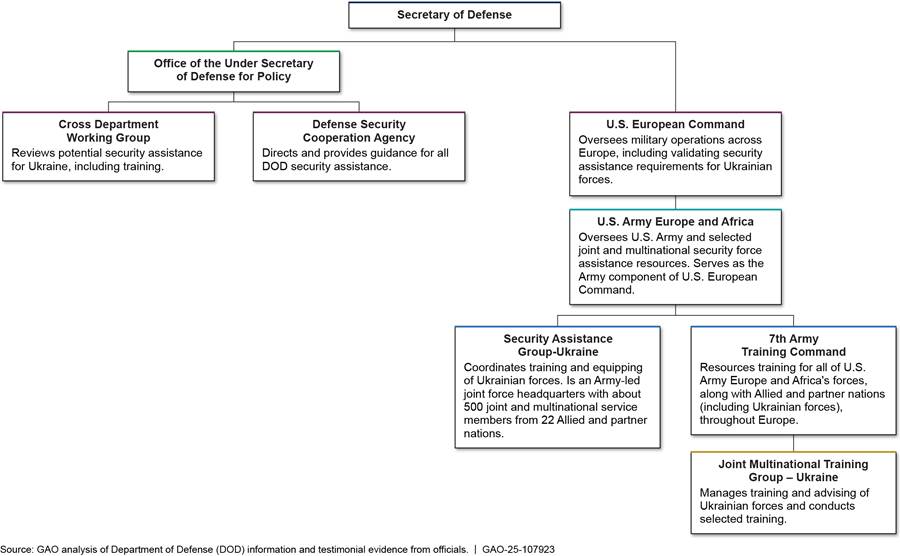

DOD relies on various subordinate organizations to execute security assistance support to Ukraine (see fig. 1).

Figure 1: Key DOD Organizations’ Roles and Responsibilities for Providing Security Assistance to Ukraine

Training Lines of Effort

Between February 2022 and April 2024, DOD trained Ukrainian military personnel—mainly at U.S. training ranges in Germany—as part of a broader international effort. The international coalition coordinated by the SAG-U has primarily focused on four training lines of effort:

· Platform and specialist training. Refers to training to develop individual and small team skills needed for specific defense article platforms (e.g., Abrams tanks) and tasks (e.g., de-mining).

· Collective training. Refers to training for larger groups of soldiers (e.g., companies, battalions, and brigades) to develop proficiency in group and combined arms activities that are key to their mission.

· Leadership training. Refers to training for individuals to develop fundamental skills needed to lead units (e.g., squads, platoons, companies, battalions, and brigades).

· Basic recruit training. Refers to basic individual military training for Ukrainian recruits. Other coalition partner nations are leading this line of effort, and the U.S. is not directly involved, according to SAG-U officials.

We omitted from this section data DOD determined to be sensitive related to the number of Ukrainians that DOD trained by the four training lines of effort.

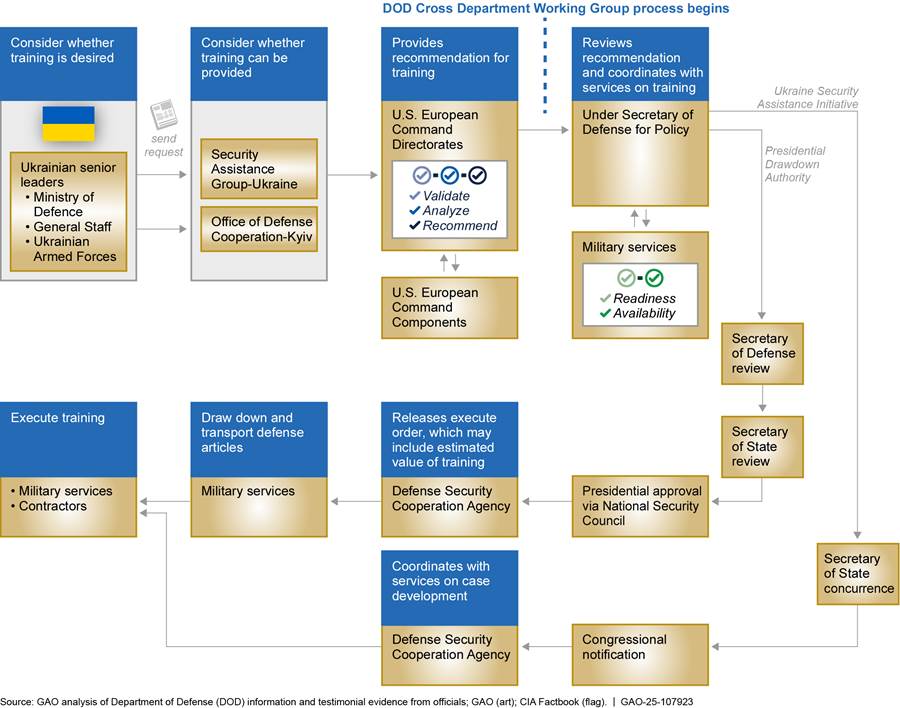

Overview of DOD’s Decision-Making Process to Train Ukrainian Forces on Defense Articles

DOD’s decision-making process to provide training for Ukrainian forces on defense articles provided by PDA and USAI involves multiple steps and stakeholders, as shown in figure 2. Generally, the process starts when Ukrainian officials request training on defense articles. Then, DOD considers if it can provide Ukrainian forces with training and the types of training DOD recommends. Next, DOD proposes how to carry out the training for the defense articles. Based on the process steps for PDA, the President of the United States approves the proposal before any defense article is transported or training begins. For USAI, DOD notifies Congress before training begins, according to DOD officials.

Figure 2: Overview of the DOD Decision-Making Process for Providing Training to Ukrainian Forces on Defense Articles

Ukraine’s requests for specific capabilities originate with senior Ukrainian leaders, including the Ministry of Defense and Ukraine General Staff. When determining a need for training on a U.S. defense article, Ukraine considers factors such as the familiarity of its forces with the U.S. defense articles and the availability of Ukrainian forces for training, according to DOD officials. Next, SAG-U processes the capability request and validates whether DOD can provide the relevant defense article and training, then sends the information to U.S. European Command for further consideration. U.S. European Command directorates and service components also validate each capability request. The command then sends a recommendation to the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy and the DOD Cross Department Working Group on whether the U.S. should provide Ukraine with defense articles and training necessary for the requested capability. The U.S. European Command recommendation means that the Commander, U.S. European Command has consented to what the Ukrainians requested and validated that the request is consistent with U.S. objectives, according to DOD officials. Stakeholders—including the military services and contractors—await presidential approval (for PDA) and congressional notification (for USAI) before committing resources to provide the defense articles and training.

Apart from training on specific defense articles, the U.S. has also provided collective and leadership training to Ukrainian forces. Officials from U.S. Army Europe and Africa explained that DOD uses a streamlined version of the process depicted in figure 2 to provide collective and leadership training. This streamlined process begins with Ukrainian senior leaders requesting the training. The SAG-U and Office of Defense Cooperation–Kyiv then provide requirements for the training and coordinate with the relevant DOD components that will deliver the training, according to officials.[13] Next, officials explained that U.S. European Command service components release orders to the appropriate subordinate commands to train the Ukrainian forces.

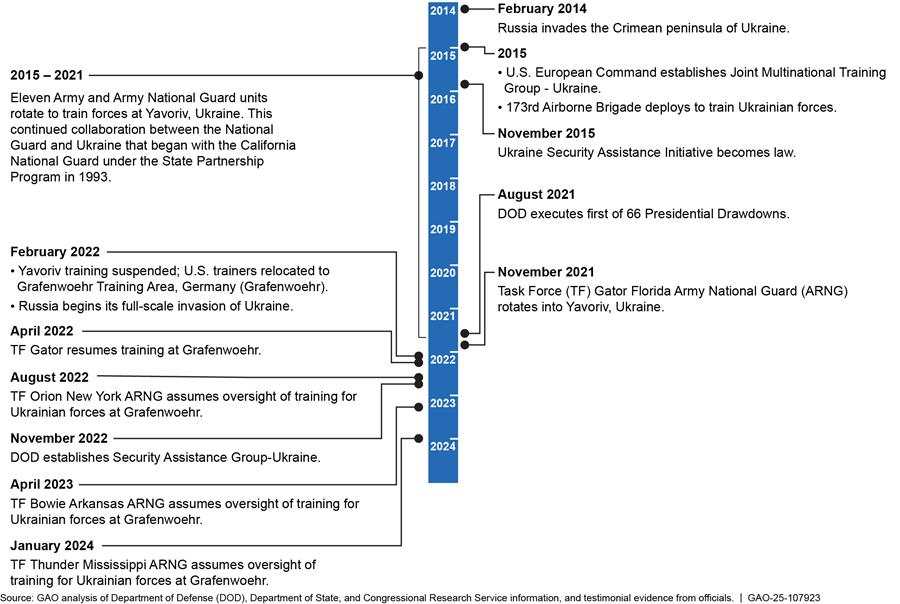

Timeline of U.S. Efforts to Train Ukrainian Forces Since 2014

U.S. training for Ukrainian forces has developed over time to align with Ukrainian needs (see fig. 3).

Training Locations

Since Russia’s invasion in February 2022, the U.S. European Command and its Army component—U.S. Army Europe and Africa—have provided most of the U.S. training for Ukrainian forces at Grafenwoehr in Germany (see fig. 4).[14] According to the U.S. Army, Grafenwoehr is its largest and most sophisticated permanent training site in Europe and encompasses a variety of training ranges. Grafenwoehr’s training ranges include live-fire and maneuver areas that the U.S. and partner nations use for training. These training ranges are of various sizes and allow training of different types and scales—from small arms qualifications to maneuver areas for tanks. At Grafenwoehr, the Joint Multinational Training Group–Ukraine (JMTG-U) and other U.S. Army units oversee training activities for Ukrainian forces, according to Army officials.[15] Additionally, the Joint Multinational Readiness Center—the U.S. Army’s Europe-based Combat Training Center located at Hohenfels Training Area—supports collective and leadership training.

Figure 4: Selected Department of Defense Locations and the Area of Conflict between Russia and Ukraine, as of March 2024

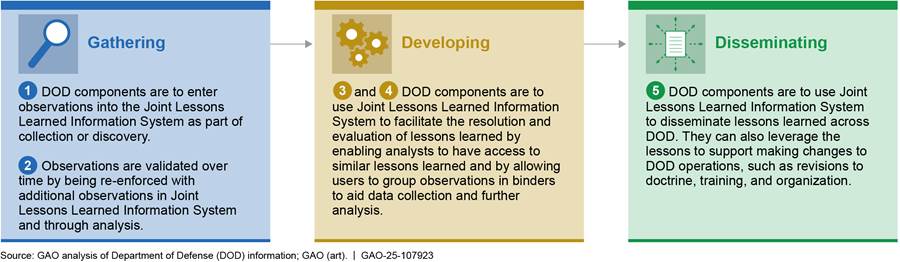

DOD’s Lessons Learned Process

DOD develops lessons learned through a five-phase process that is facilitated by its Joint Lessons Learned Information System, among other tools.[16] The process involves recording and validating observations, developing the lessons for further analysis, and disseminating the lessons across the department (see fig. 5). The primary objective of the process is to enhance force readiness and effectiveness by contributing to improvements in shorter-term operations and planning as well as longer-term doctrine, organization, training, materiel, leadership and education, personnel, facilities, and policy, according to DOD.

Figure 5: The DOD Process to Facilitate Lessons Learned through the Joint Lessons Learned Information System

DOD Uses Various Processes to Train Ukrainian Forces, but U.S. Army Units Faced Some Challenges Delivering Training

DOD has used processes to provide training to Ukrainian forces for requested capabilities. When providing new defense articles to a recipient nation, DOD policy suggests using a total package approach, which is intended to ensure that recipient nations receive training and other support for those articles.[17] However, based on information provided by officials, U.S. Army units initially faced and addressed challenges training Ukrainian forces because DOD did not always implement a total package approach for some defense articles delivered under PDA.

DOD Used Processes to Provide Security Assistance Training

Since the Russian invasion in February 2022, DOD officials prioritized the prompt delivery of defense articles to Ukraine. In particular, DOD has processes in place to use a combination of USAI, PDA, and Section 331 authority to facilitate the delivery of defense articles and training to

|

Armored Personnel Carrier Armored infantry carrier that can be outfitted with various mortars. · Number U.S. is committed to provide Ukraine: 742 · Date first trained at Grafenwoehr Training Area: April 2022 Source: Department of Defense (information); U.S. Air National Guard/Tech. Sgt. M. Olsen (photo). | GAO‑25‑107923 |

Ukraine.[18] Training increased in importance because Ukrainian soldiers were unfamiliar with certain defense articles used by the U.S. and its allies, such as the U.S. version of the Armored Personnel Carrier, according to DOD officials (see sidebar).

USAI. USAI authorizes the Secretary of Defense, with concurrence from the Secretary of State, to provide appropriate security assistance and intelligence support to Ukraine. Such assistance can include training, defense articles, logistics support, supplies, and services to military and other Ukrainian security forces. For example, DOD has used USAI to purchase artillery, ammunition, missiles, antiaircraft systems, tanks, and medical supplies for Ukraine. Since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, $32.7 billion has been appropriated to USAI, the majority of which ($31.8 billion) was provided by the five Ukraine supplemental appropriations.

PDA. Since 2021, the U.S. has provided defense articles and training to Ukraine using PDA.[19] Historically, U.S. law capped the maximum aggregate value of defense articles, services, and training provided under this type of PDA at $100 million in any fiscal year.[20] However, in support of Ukraine security assistance, among other efforts, Congress increased this annual PDA funding cap from $100 million to $11 billion for fiscal year 2022 and $14.5 billion for fiscal year 2023. For fiscal year 2024, Congress increased this PDA funding cap up to $7.8 billion. From August 2021 through September 2024 the President approved 66 PDA packages of various sizes.[21]

The U.S. has provided Ukrainian forces with training on defense articles delivered under PDA. However, because PDA is not a source of funding, DOD has also relied on USAI funds and annual operation and maintenance appropriations to provide Ukraine with training on defense articles delivered under PDA.

Section 331. Section 331 of title 10, U.S. Code, authorizes the Secretary of Defense to provide friendly foreign countries with support for the conduct of operations. This authority can include using unit operation and maintenance funding to provide operational support, such as training, to these countries. The U.S. has used this authority to provide training to Ukrainian forces on defense articles delivered under PDA, according to DOD officials.

U.S. Army Units Faced and Ultimately Addressed Challenges with Training Ukrainian Forces for Defense Articles Provided Under PDA

DOD officials told us that they used PDA to meet immediate Ukrainian operational needs and used funding authorized by Section 331 authority to bridge any resource gaps. However, the expanded size, scope, and speed of equipment delivered under PDA since 2022 posed challenges to DOD’s ability to implement a total package approach when delivering some defense articles, and these factors contributed to unanticipated challenges for U.S. Army units delivering training to Ukrainian forces.

|

Paladin 155MM self-propelled howitzer. · Number U.S. is committed to provide Ukraine: 36 · Date first trained at Grafenwoehr Training Area: February 2023 Source: Department of Defense (information); U.S. Army/Sgt. T.Stubblefield (photo). | GAO‑25‑107923 |

These challenges initially resulted in training disruptions due to insufficient amounts of training equipment, limited training preparation time, inadequate support resources, and mismatches between training needs and expertise. U.S. Army units that delivered the training addressed these challenges using mitigation strategies, to include adapting schedules to minimize down-time, changing programs of instruction to accommodate delays, and obtaining contractor support to provide trainer expertise. More specifically:

Insufficient training equipment. Officials told us that some equipment items that U.S. Army units used to train Ukrainian forces did not arrive in sufficient quantities or as quickly as planned. For example, the U.S. Army unit providing training for the Paladin told us that they received fewer Paladin self-propelled howitzers than were needed to support training in an already time-compressed program of instruction (see sidebar). Additionally, not all of the Paladins were in working condition. As a result, the training unit needed additional time and resources to repair the remaining Paladins to use them for training, according to officials. The U.S. Army trainers also told us they had to adapt the programs of instruction for the training by rearranging the order of training events until they had time to repair the equipment.

Limited training preparation time. U.S. Army units providing training were not always notified about the training requirements for arriving defense articles with sufficient time to plan that training. Officials told us that they ordinarily need 30 to 60 days to efficiently plan and schedule training. However, given the speed of the PDA process to deliver defense articles to meet Ukraine’s immediate battlefield needs, trainers generally received 18 days of advance notice to plan training for Ukrainian forces, according to DOD officials. Officials further stated that this abbreviated notice of requirements strained their ability to plan and resource some training. U.S. Army personnel from units that provided the training to Ukrainian forces told us they were able to overcome these challenges, but it disrupted training as they awaited the arrival of repair parts and had to change the program of instruction to accommodate the delay. These types of challenges exacerbated the shorter than normal timeframes to train Ukrainian forces than what the U.S. Army allots to train U.S. personnel, and it resulted in reduced hands-on training time for some Ukrainian personnel than they would have normally received in peacetime, according to these officials.

Insufficient support resources. For some defense articles, the training unit received equipment from Army prepositioned stocks. In some cases, this arriving equipment did not include maintenance items and tools needed to keep the equipment in good working order during the training period. Officials responsible for training Ukrainian forces told us that the initial planning process did not ensure that units like the 7th ATC had appropriate personnel and resources to maintain the training equipment drawn from Army prepositioned stocks.

|

Abrams tank Armored battle tank with a 120MM main gun. · Number U.S. is committed to provide Ukraine: 33 · Date first trained at Grafenwoehr Training Area: May 2023 Source: Department of Defense (information); U.S. Army/ Spc. N. Franco (photo). | GAO‑25‑107923 |

In the case of Abrams tanks, trainers needed other resources—for example, tank recovery vehicles, heavy equipment transport vehicles, training tools, calibration tools, and track repair tools—to carry out the training (see sidebar). Officials said that the planning process for the training would have benefited from longer lead times between notification of the training need and the beginning of training so that these issues could be addressed.

U.S. Army officials told us, in some instances, SAG-U personnel who recommended various types of training did not have the technical knowledge to know what maintenance items to include in requests. Other officials explained that when a defense article such as a Paladin is in Army prepositioned stocks, certain items that are needed to use it for training are not necessarily part of the equipment set that is issued from those stocks. Officials added that this applied to other defense articles beyond the Paladin as well.

Mismatches between training needs and expertise. Personnel were assigned to train Ukrainian forces on some defense articles that differed from the version that the Ukrainians would take into combat. As a result, trainers were unfamiliar with certain aspects of the equipment on which they provided training to Ukrainians. For example, U.S. Army units trained Ukrainian forces using the U.S. military version of the Bradley Fighting Vehicle. However, the U.S. transferred a different version of the Bradley Fighting Vehicle that Ukrainian forces ultimately took into combat. Training on different versions of the vehicle was necessary to align the availability of the training equipment with training schedules and availability of Ukrainian personnel, according to DOD officials. Officials from the Bradley Program Management Office told us that the variant Ukrainian forces trained on and the version they were provided for operational use had most of the same characteristics except for the target acquisition system.

|

Bradley Fighting Vehicle Armored vehicle with cross-country mobility and a 25MM cannon. · Number U.S. is committed to provide Ukraine: 292 · Date first trained at Grafenwoehr Training Area: January 2023 Source: Department of Defense (information); U.S. Army/Staff Sgt. W. Bonner (photo). | GAO‑25‑107923 |

To mitigate this mismatch, officials told us that trainers taught the differences between the versions, using the U.S. military version for field training while contrasting it with the target acquisition system on the version that Ukrainian forces would receive. The trainers from U.S. Army units only had experience operating the U.S. military version of the Bradley Fighting Vehicle but had to teach Ukrainian forces to operate the different version (see sidebar).

U.S. Army unit officials also described examples of training for certain defense articles for which they did not have the requisite expertise. DOD used USAI funding to resource contractors that provided the training, and this process took a longer amount of time than planned and led to a training delay. For example, trainers found that they were not fully familiar with the version of the Stryker combat vehicle that the Ukrainians were to employ in combat. In this instance, trainers relied on USAI-funded contractors to provide the training. Officials also stated that similar training issues arose for the Mine Resistant Ambush Protected vehicle.

DOD guidance specifies that security assistance administered by DOD shall be planned, programmed, budgeted, and executed with the same high degree of attention and efficiency as other integral DOD activities.[22] DOD guidance further states that a total package approach helps ensure that international recipients receive all support articles and services required to introduce, operate, and maintain U.S. defense articles. A complete package includes support equipment and other maintenance resources needed by U.S. military units to deliver training. DOD officials told us that the total package approach allows for considering the international recipient’s operational needs. In this case, the officials stated that acquiring the materiel and planning the associated platform training would have delayed the delivery of the defense articles by several months and could have negatively affected the course of the war.

|

Stryker infantry carrier vehicle 8-wheeled armored fighting vehicle. · Number U.S. is committed to provide Ukraine: 189 · Date first trained at Grafenwoehr Training Area: February 2023 Source: Department of Defense (information); U.S. Army/Spc. T. Vuong (photo). | GAO‑25‑107923 |

In the initial months following Russia’s February 2022 invasion, DOD’s ability to plan and identify training needs for defense articles delivered to Ukraine was hindered because the department had not developed detailed guidance to assist planners in applying a total package approach under PDA. Further, a DOD official told us that the department had not envisioned fielding new capabilities for recipient countries at such a scale via PDA alone. The lack of guidance resulted in training-related decisions that were not fully identified and resolved until after the security assistance package was approved and sent to the service components for execution. Officials told us that the lack of guidance initially created circumstances during which it was unclear which office was responsible for administering training. For example, U.S. Army program managers and training units did not resolve responsibilities for training Ukrainian forces on the Stryker combat vehicle until the program management officials were on site (see sidebar).

During the initial months of providing Ukrainian forces with training for defense articles delivered under PDA, officials realized they needed to adopt a total package approach to mitigate disruptions that U.S. Army units experienced providing training. In the absence of clear guidance and as DOD’s assistance to Ukraine progressed, DOD and the military services relied on synchronization meetings and other ad hoc mechanisms not yet incorporated into guidance to better plan for Ukrainian forces’ training needs and mitigate challenges, according to DOD officials. DOD officials further explained that they realized that adopting a total package approach for defense articles provided under PDA helped mitigate earlier challenges they experienced and told us the department has taken steps to ensure that PDA support packages now account for this approach. Specifically, USAREUR-AF officials told us that they coordinate with 7th ATC earlier in the security assistance process to ensure that the command has appropriate personnel and resources to support training.

The DSCA Handbook for Foreign Assistance Act (FAA) Drawdown of Defense Articles and Services provides some guidance on the planning and execution of drawdowns and specifies that, where possible, complete support packages are normally provided for any major end items provided under PDA, including training for both operation and maintenance of the item.[23] However, this document is not designed to be widely accessible or applied across the department, according to DSCA officials. Officials told us that the information in the handbook is the only guidance available but is of limited usefulness since DOD did not envision using PDA in a crisis security assistance scenario. Specifically, the handbook does not explain how to plan security assistance training in situations that require rapid execution. Nor does it specify which offices or organizations are responsible for providing complete support packages for defense articles. For example, the guidance does not detail which DOD component is responsible for training decisions and how to obtain funding for training and maintenance of training equipment under PDA.

To their credit, DOD components took measures to address challenges that arose when providing training to Ukrainian forces on certain defense articles delivered under PDA. However, by issuing guidance that requires DOD components such as the combatant commands to identify the resources necessary for training when proposing a security assistance package, including situations that require rapid execution of PDA, the department would be better positioned to avoid potential challenges that might disrupt training under a future use of PDA.

DOD Does Not Collect Quality Data to Assess Training for Ukrainian Forces or Consistently Document Lessons Learned

DOD Has Several Approaches to Assess the Training Provided to Ukrainian Forces, but Has Not Collected Consistent, Quality Data

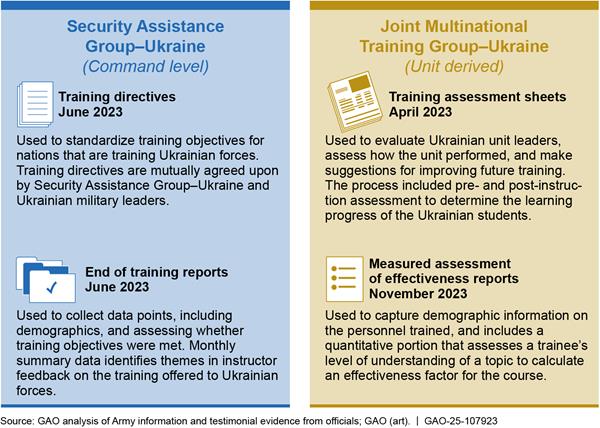

DOD components, including SAG-U and JMTG-U, have used several approaches to assess the training provided to Ukrainian forces (see fig. 6). For example, SAG-U uses training directives and end-of-training reports to establish consistent objectives and collect observations to improve training provided to Ukrainian forces. Training units, such as JMTG-U, have developed unit-derived training assessment tools, including training assessment sheets and measured assessment of effectiveness reports, to collect demographic information and assess the training provided to Ukrainian forces.

Figure 6: Examples of Department of Defense Approaches to Assess Training Provided to Ukrainian Forces

Training assessment processes are important and can help achieve two goals, according to U.S. Army training guidance.[24] First, assessments can determine the extent to which an individual learner achieved the expected outcome. Second, assessments can be a valuable data source for the evaluation of learning products and may indicate weaknesses in instruction or materials.

Information provided by DOD officials shows that these training assessment approaches have had some positive effects, such as standardizing training objectives for courses administered to Ukrainian forces and identifying areas for improvement. The SAG-U also has used the feedback contained on end of training reports to evolve its classes to better meet the needs of Ukrainian forces.

However, we found that these approaches were hindered by insufficient data, inconsistent data collection methods, and incomplete data.

Insufficient data. We found that end of training reports did not capture detailed data related to training objectives that would provide insights into potential training improvement areas or to evaluate trends over time.[25] The reports also did not provide insight into which training objectives the units delivering training emphasized or deemphasized to improve training. Further, we found that SAG-U and the U.S. Army training unit could not assess the extent to which the training audience met each training objective established in the training directives due to the format of the end of training reports.

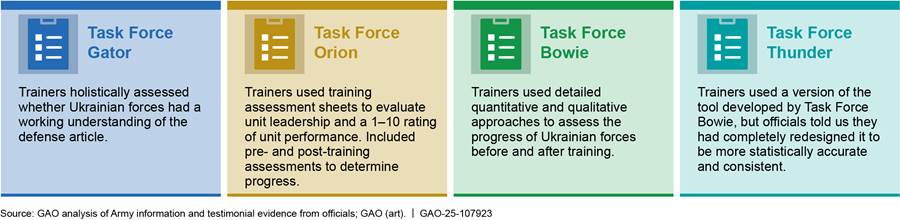

Inconsistent data collection methods. Similarly, we found that JMTG-U’s ability to assess training trends is limited because it has used inconsistent data collection approaches over time. More specifically, based on information provided by JMTG-U officials, we found that successive JMTG-U task forces changed the approach they used to assess U.S. training of Ukrainian forces every 9 months. Each JMTG-U task force developed a new training assessment, according to officials with these units (see fig. 7).

For example, Task Force Gator’s assessment process involved evaluating whether the trainees had a working understanding of the defense article, according to an official. An official from Task Force Orion, which followed Task Force Gator, told us that they developed a more detailed training assessment using broader U.S. Army training assessment guidance as a template. The training assessment sheet template includes a place to evaluate Ukrainian unit leaders and a one to 10 rating scale to evaluate the unit’s performance, among other measures. The training assessment sheets used by Task Force Orion also asked for information about the training unit’s knowledge before and after the training.

Task Force Bowie officials told us that they received some assessment documentation from the previous task force. However, these officials also told us that they decided to develop their assessment tool without using the previous task force’s assessment tool as a model. Task Force Bowie’s assessment tool, the measured assessment of effectiveness reports, differed from the prior training assessment sheets in that they included a multi-faceted, quantitative comparison of a unit’s knowledge before and after training. The overall approach was more detailed than any of the prior assessment tools used by JMTG-U task forces. An official from Task Force Thunder, the most recent unit to staff the JMTG-U, told us that Task Force Bowie provided them information and examples of the measured assessment of effectiveness report.

However, the official from Task Force Thunder also told us that they completely redesigned the tool to be more statistically accurate and consistent. Further, the official noted that they have not received clear guidance from their higher headquarters as to how training assessment should be executed and what they should focus on. The only guidance they have received came from the SAG-U in the form of training directives and end of training reports, which, as we noted above, have key limitations when used to assess training. While Task Force Thunder documented the use of the measured assessment of effectiveness reports in their unit standard operating procedures, these reports are not documented as the training assessment mechanism for the JMTG-U. Based on the information provided by JMTG-U officials, this means the reports are subject to change every 9 months when a new Task Force takes over as the JMTG-U.

Incomplete data. We also found that the end of training reports contained incomplete data, which hinders SAG-U’s and JMTG-U’s ability to assess the training delivered to Ukrainian forces. JMTG-U officials told us that they analyze demographic trends to make recommendations and adjust future training courses in accordance with trainees’ experience levels. However, we found that the U.S. units that completed end of training reports responded to some, but not all of the requested data fields. For example, the ages and ranks of the Ukrainian personnel attending training were frequently not provided. Of the 15 end of training report examples we analyzed, seven did not report ages at all, three reported ages in percents, four reported the numbers of attendees in various age ranges, and one reported the ages of most, but not all of the class members. Only three of the 15 reports included the ranks of the trainees. Officials with the current JMTG-U unit told us that Ukrainian forces have been hesitant to provide personally identifiable information. In response, JMTG-U has started to use an advance mission support team of senior leaders to try to increase the data provided by Ukrainian forces.

We found similar data quality issues related to the information that units recorded for the training line of effort (two out of 15 reported this information) and whether the personnel being trained were from the Ministry of Defense or Interior Ministry (three out of 15 reports included this information). This type of demographic information is important for DOD’s organizations that are training Ukrainian forces to understand because it can help them tailor the training to the audience, according to DOD officials. Further, this information can help provide context for any lessons learned if trainees in certain demographic categories have different strengths and weaknesses than others.

We also reviewed examples of other tools used by the JMTG-U to assess the training of Ukrainian forces, such as the measured assessment of effectiveness reports. The three measured assessment of effectiveness reports we reviewed contained more complete demographic information than the data provided in the end of training reports. However, an official from Task Force Thunder stated that U.S. Army Europe and Africa and 7th ATC have not directed the use of the measured assessment of effectiveness reports, and these reports were administered at the unit-level by the JMTG-U. JMTG-U officials were not sure how the information from the reports was used by their higher headquarters, if at all.

DOD Instruction 5132.14, Assessment, Monitoring, and Evaluation Policy for the Security Cooperation Enterprise, states that geographic combatant commands are responsible for monitoring all significant initiatives by collecting data that are organized in a systematic way to facilitate analysis and track trends to support program management decisions.[26] Federal internal control standards suggest that management should design a process that uses the entity’s objectives and related risks to identify the information requirements needed to achieve the objective and address the risks.[27]

DOD’s efforts to assess the training it has provided Ukrainian forces do not enable systematic analysis and tracking of trends. This is because DOD has not clearly documented the processes its components are to use and the data elements necessary to fully understand the training needs of Ukrainian forces and improve training over time. For example, officials from different JMTG-U task forces told us that prior training assessment processes and procedures were not well-documented, which led them to develop their own approaches. Each new JMTG-U task force rewrote the training assessment protocols, resulting in gaps in data while the new tools were developed and data that cannot easily be combined or analyzed over time due to the changing assessment practices.

U.S. European Command does not provide clear guidance to subordinate organizations on assessing the training for Ukrainian forces. By providing guidance to document the approaches these organizations are to use to assess the training delivered to Ukrainian forces and ensure data quality, DOD will be able to collect consistent, quality data to assess training. Providing this guidance will better position the department to make more effective decisions regarding whether, when, and how to provide such training, both for Ukrainian forces and for future conflicts.

DOD Has Lessons Learned from Training Ukrainian Forces, but Does Not Consistently Document and Disseminate Observations

DOD and its components have ongoing efforts to capture lessons learned from training Ukrainian forces. DOD requires components to document and disseminate relevant observations across the department using the department’s authoritative system, called the Joint Lessons Learned Information System. However, DOD components that are involved in the efforts to train Ukrainian forces have not consistently recorded lessons learned, as required.

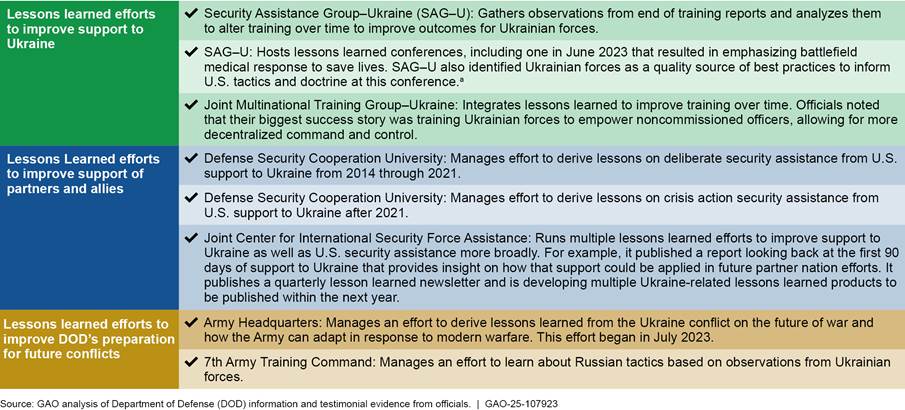

We identified three categories of DOD efforts to capture lessons learned from training Ukrainian forces. The categories involve processes to improve: 1) DOD’s support to Ukraine, 2) DOD’s support of partners and allies, and 3) DOD’s preparation for future conflicts (see fig. 8).

aDOD officials told us that this SAG-U lessons learned conference included discussion on the need for better multinational information sharing and this led to improvements. They also noted another conference took place in August 2023 where SAG-U officials made training assessments a key point of discussion.

DOD officials provided examples to illustrate how lessons learned efforts are improving training to Ukraine as well as DOD’s overall preparation for future conflict. For example, SAG-U and JMTG-U have adjusted the content of training courses based on feedback from Ukrainian forces. Additionally, SAG-U documentation shows that SAG-U hosted a lessons learned conference in June 2023. The conference included discussion on the need for better multinational information sharing, which led to improvements, according to a DOD official. They also noted another conference took place in August 2023 where SAG-U officials presented some of their findings and processes on training assessments. Further, the U.S. Army has begun to adjust its large-scale training exercises to include more trench warfare and drone use because of lessons learned from training Ukrainian forces, according to Army officials.

However, we found that components did not consistently record relevant observations or make them available in a timely manner in the Joint Lessons Learned Information system, as required by DOD policy. For example,

· Defense Security Cooperation University officials told us they do not make their observations widely discoverable in the Joint Lessons Learned Information System until they are validated. As of June 2024, Defense Security Cooperation University had approximately 20 Ukraine-related observations in the Joint Lessons Learned Information System, but officials noted there are a significant number waiting to be internally drafted and validated.

· Headquarters, Department of the Army and Center for Army Lessons Learned officials provided documentation and explained that about half of the more than 30 organizations involved in U.S. Army efforts to train Ukrainian forces have submitted observations in the Joint Lessons Learned Information System from October 2023 through April 2024. However, these officials told us they were looking to increase the participation from other relevant U.S. Army organizations to gather more lessons learned material for their effort.

· Joint Center for International Security Force Assistance officials told us that DOD’s efforts to capture lessons learned from training Ukrainian forces are more limited than prior efforts, such as those in Afghanistan. Specifically, these officials said that there is a lack of emphasis on aggregating lessons learned from multiple sources in the Joint Lessons Learned Information System and elsewhere. The officials told us that improving the synthesis of lessons learned is a key step toward enabling quality lessons learned to improve DOD operations and said that greater emphasis on using the Joint Lessons Learned Information System can help in this regard.

Our review of entries in DOD’s Joint Lessons Learned Information System found that there were few entries from DOD’s efforts to train Ukrainian forces recorded in 2024. For example, there were no entries from JMTG-U through the first 3 months of the year. Joint Staff officials agreed with our observations and told us that increased use of the system by organizations involved with training Ukrainian forces would allow DOD to have broader access to observations. In addition, entering observations into the Joint Lessons Learned Information System within the required 45-day period would aid in DOD’s development of lessons learned and preparation for future conflicts.

Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Instruction 3150.25H states that combatant commands are to support local lessons learned processes by capturing and sharing observations from suitable operations, exercises, or events through the Joint Lessons Learned Information System within 45 days, after the conclusion of the event.[28] However, U.S. European Command does not consistently document observations from training Ukrainian forces in this system because it has not ensured subordinate commands implement the department’s policy, such as by communicating the importance of using the system or documenting guidance at the subordinate command level.

While there is broad guidance from DOD requiring reporting observations into the Joint Lessons Learned Information System within 45 days, this guidance may not be known to all subordinate organizations because it is not always reflected in these organizations’ implementing guidance. For example, among the documents that govern the U.S. processes to train Ukrainian forces, 10 of the 26 we reviewed identified lessons learned procedures in general and three of them identified the importance of recording observations in the Joint Lessons Learned Information System. Many of the organizations collecting lessons learned from training Ukrainian forces are not capturing and sharing observations in the Joint Lessons Learned Information System because they have not documented the requirement to do so. As a result, DOD’s lessons learned may not be comprehensive or timely, leading to missed opportunities for improvement.

Training Ukrainian Forces Has Increased Range Use and Has Had Varied Effects on U.S. Force Readiness

Range Use at Grafenwoehr Has Increased, but U.S. Training Has Continued There and at Other Sites

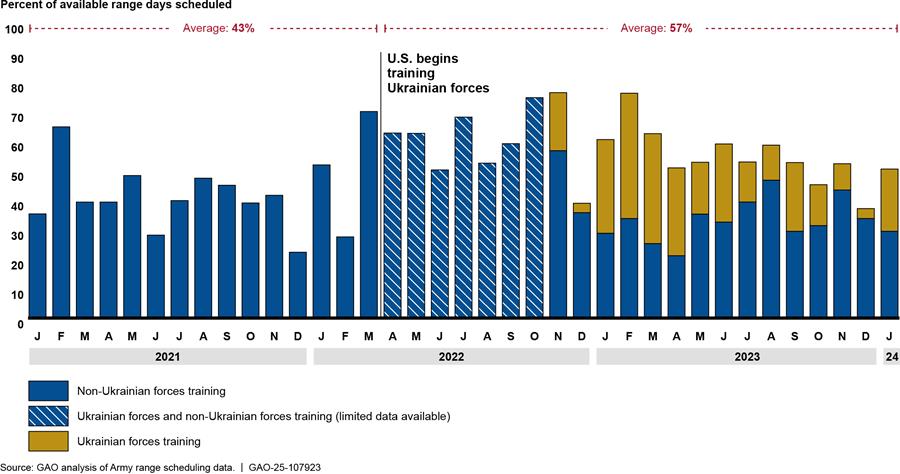

Our analysis found that U.S. training of Ukrainian forces contributed to increases in overall training range usage at Grafenwoehr since Russia’s invasion in February 2022. From January 2021 through March 2022, U.S. and partner nation units scheduled an average of 43 percent of the days available across all training ranges at Grafenwoehr each month (see fig. 9). From April 2022 through January 2024—after the U.S. began training Ukrainian forces—units scheduled an average of 57 percent of the days available across all training ranges at Grafenwoehr each month, a 14-percentage point increase.[29] However, a 7th ATC official responsible for managing Grafenwoehr’s training ranges told us that Grafenwoehr has had sufficient capacity to train Ukrainian forces since the training mission began.

Figure 9: Percentage of Training Range Days Scheduled at Grafenwoehr Training Area, by Month, January 2021–January 2024

Note: Non-Ukrainian forces training includes U.S. Army unit and partner nation training.

Since 2022, Grafenwoehr has continued to host regular U.S. and partner nation training activities like those pictured in figure 10, along with training for Ukrainian forces. 7th ATC officials told us that training for Ukrainian forces has been identifiable in the training range scheduling system since November 2022.[30]

Training events for Ukrainian forces have used certain training range resources more than others. For example, officials told us that collective training has required intensive use of maneuver ranges at Grafenwoehr and Hohenfels Training Area at certain times.[31] Between November 2022 and January 2024, the most frequently scheduled ranges for training Ukrainian forces at Grafenwoehr included maneuver ranges, an urban operations site, a tactical driver training course, and sites for operating heavy equipment. Officials also told us that the 7th ATC has been able to generally accommodate training needs for Ukrainian forces, foreign partners, and U.S. forces at Grafenwoehr and Hohenfels Training Areas. For example, these officials stated that when the Hohenfels Training Area was needed for U.S. collective training events, the 7th ATC shifted Ukrainian collective training events to available maneuver areas at Grafenwoehr.

In some cases, however, U.S. Army units have had to cancel, reschedule, or divert training to alternative locations because certain training ranges were being used for training Ukrainian forces at Grafenwoehr and because training Ukrainian forces has created a less predictable training schedule, according to officials. For canceled or rescheduled training, an official from Fifth Corps (V Corps) told us that units near Grafenwoehr typically work directly with range operations personnel to identify alternative ranges or times as scheduling conflicts arise.[32] In other cases, the official told us that units were able to realign training with partner training events and planned multinational exercises. However, officials from the 173rd Infantry Brigade Combat Team told us that their units located further from Grafenwoehr—for example, those in Italy—are not able to adjust their training plans as readily due to the logistics involved in moving personnel and equipment from one country to another.[33] Additionally, to address their long-term planning requirements, some U.S. Army units decided to conduct training events at sites in other partner nations.

Officials told us that 7th ATC has prioritized efforts to expand access to training ranges and areas located in partner nations, and this access helped to mitigate disruptions in training for U.S. Army units. The U.S. has access to more than 30 training sites in partner nations as of 2023, which increased from approximately five sites in 2016, according to these officials. These sites span 28 countries and can be used to accommodate training events for U.S. Army units outside of Grafenwoehr. For example, some 173rd Infantry Brigade Combat Team units have trained in Slovenia and Croatia, while some V Corps units have trained in Poland, Finland, and Greece, among other partner nations, according to officials from these units. Further, 7th ATC’s Expeditionary Training Support Division has worked to enhance the ranges and training resources available at these sites.

Officials we met with described the advantages and disadvantages of conducting training for U.S. Army units at locations outside of Grafenwoehr. We describe examples from two units below.

V Corps. An official from V Corps told us that U.S. training for Ukrainian forces at Grafenwoehr saved costs for some of its units that trained at alternate sites, while costs for other units increased. While these alternative training sites had varied cost implications, overall training costs remained within their spending plans, according to the official. The official told us that V Corps units at times used training sites in Poland and other partner nations as an alternative to training at Grafenwoehr. In addition, the partnership with Poland has allowed U.S. Army units located there to conduct training up to the level of battalion live fire events, an approach that has achieved cost savings compared with training at Hohenfels. For example, the official estimated that moving an armored battalion from Poland to Germany for training costs $5 million, and they saved this amount by training in Poland. Further, V Corps artillery and aviation units located in Germany required larger ranges and conducted some training events in Finland, the United Kingdom, and Greece as an alternative to Grafenwoehr. These events incurred some additional travel costs but facilitated a high quality of training, according to the official.

173rd Infantry Brigade Combat Team. Documentation provided by the 173rd Infantry Brigade Combat Team indicated that U.S. training for Ukrainian forces limited the availability of maneuver areas at Grafenwoehr. As a result, 173rd Infantry Brigade Combat Team units trained simultaneously at sites in Slovenia and Croatia in early 2024. Overall training costs remained similar to training at Grafenwoehr, according to DOD officials. While the 173rd Infantry Brigade Combat Team is familiar with conducting training events in partner nations, the large scale of these recent training events required extensive coordination with host nation officials to overcome complex logistics challenges and local political concerns, according to officials. Further, to meet the training requirements of each unit, the 173rd Infantry Brigade Combat Team received assistance from 7th ATC’s expeditionary training support team to construct ranges that met U.S. Army standards. Officials told us that most units completed training as planned, but some training equipment that is available at Grafenwoehr—for gathering data and measurements, for example—was not available. Additionally, host nation requirements led one battalion to scale down its training.

U.S. Army Units Experienced Varied Readiness Effects Due to Training Ukrainian Forces

U.S. Army Headquarters officials responsible for service readiness reporting told us that they have not identified any significant trends in aggregate readiness data for U.S. Army units associated with training Ukrainian forces.[34] However, officials we interviewed described some positive and negative readiness effects among selected units that frequently supported training of Ukrainian forces.[35]

Officials from some U.S. units that supported the training of Ukrainian forces told us that their unit readiness was negatively affected as a result of deprioritizing their own training needs or due to added wear and tear on their equipment. Units that frequently served as trainers told us that they faced constraints on the amount of time that was available to train themselves. For example, the intensive operational requirements of the Ukraine training mission led units to delay required training until later in their deployment or scale down the training, according to unit officials. Further, units that used their own equipment to train Ukrainian forces told us that they faced challenges keeping the equipment maintained and functional, which led to extended maintenance schedules in some instances. For example, unit-provided Bradley Fighting Vehicles saw intensive use for the Ukraine training mission that resulted in additional wear and tear, according to unit officials.

However, officials from three U.S. Army units that served as trainers told us that challenges ultimately did not significantly reduce readiness because they had sufficient personnel, maintenance resources, and technical expertise available for the training mission.

· Personnel. Officials said that U.S. Army Europe and Africa provided U.S. Army units with enough personnel to serve as trainers for Ukrainian forces, tasking both deployed units and units located in Europe as needed. Officials from units we spoke with told us that the establishment of SAG-U and U.S. Army Europe and Africa’s support allowed their units to both meet the mission as trainers and conduct their own required unit training. For example, when the training mission expanded to encompass training for additional Ukrainian battalions, U.S. Army Europe and Africa was able to task additional units as trainers. Unit officials told us that this eased the training burden and allowed most of their companies to accomplish their unit live fire training.

· Maintenance resources. Some unit officials noted negative readiness effects and related challenges due to wear and tear on their equipment, but these officials also noted that maintenance and technical initiatives helped to mitigate these effects. Officials said that U.S. Army units that trained Ukrainian forces were able to identify and use available maintenance resources, such as part fabrication capabilities and supply centers at Grafenwoehr. Further, an official told us that U.S. Army Europe and Africa also provided units with priority access to these resources, which allowed units to maintain their equipment while using it intensively during training. For example, maintainers were able to fabricate complex hydraulic components for the Bradley Fighting Vehicle on site at Grafenwoehr as opposed to procuring the component from the U.S., which saved time and money, according to officials.

· Technical expertise. Officials said that U.S. Army units were able to solve challenging maintenance issues outside of their expertise and available resources by closely coordinating with program managers and contractors responsible for the defense articles. For example, program managers for Bradley Fighting Vehicles were able to provide additional maintenance capability to the U.S. Army unit that used its own vehicles to train Ukrainian personnel, facilitating more thorough technical inspections.

Unit officials we spoke with also described some positive effects on general readiness that may not be captured in a unit’s readiness reporting, including morale and retention, repetition, and knowledge sharing.

· Morale and retention. Officials said that serving as trainers for Ukrainian forces generated higher morale among the units, which can lead to higher retention and other positive effects. For example, one unit noted a significant increase in retention while carrying out the Ukraine training mission.

· Repetition. Officials said that regularly repeating training exercises with the Ukrainian forces helped units develop mastery of their own equipment and training tasks. Further, this helped bolster units’ ability to complete their own required training tasks. For example, soldiers that led multiple iterations of rifle training improved their firing, breathing control, and use of Javelins. A unit official also told us that serving as trainers provided an opportunity for U.S. Army units to conduct more of their own training while Ukrainians were not using the range during part of a scheduled time slot.

· Knowledge sharing. Officials said that communicating with Ukrainian soldiers who had been in combat provided U.S. Army units with firsthand knowledge of how their training might be applied on the battlefield. In addition, this allowed units to gain insights that may inform updated U.S. Army doctrine and tactics. For example, a unit that led Stryker combat vehicle training spoke with Ukrainian soldiers about how the Ukrainians used the vehicles in combat in concert with autonomous aerial systems.

Army officials told us that the use of Army prepositioned stocks as training equipment had positive and negative effects on the equipment. For example, Army officials told us that regular use of such equipment for training may improve readiness in a qualitative sense as the equipment is worked and maintained more frequently. However, the equipment may not be available for other purposes when used for training.

Conclusions

The U.S. has provided significant support to Ukraine since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. DOD provided training for defense articles, collective training for Ukrainian units, and leadership training.

DOD used PDA to help provide an unprecedented volume of defense articles to Ukraine in condensed timeframes. However, U.S. Army units that trained Ukrainian forces on defense articles provided under PDA faced unanticipated challenges that caused some training disruptions. DOD did not plan and identify training needs for defense articles delivered to Ukraine with a high degree of attention and efficiency during the first few months of the effort. In part, this is because the department did not have guidance to assist planners in applying a total package approach under PDA in situations that require rapid execution. DOD components addressed challenges using several mitigation strategies including adapting training schedules and obtaining contractor support. DOD officials emphasized the importance of a total package approach for PDA, based on their experiences training Ukrainian forces. By issuing guidance that requires DOD components such as the combatant commands to identify the resources necessary for training when proposing a security assistance package, including situations that require rapid execution of PDA, DOD can more effectively avoid potential challenges that might disrupt training under a future use of PDA.

DOD has a variety of approaches and processes to assess training for Ukrainian forces and develop lessons learned from these efforts. However, DOD’s efforts to assess the training are hindered by various data quality and collection issues, because DOD has not clearly documented the processes its components are to use or the data elements that are needed to meet its objectives. By ensuring that U.S. European Command provides clear guidance to subordinate organizations on documenting their approaches for assessing training provided to Ukrainian forces and data elements and standards to ensure data quality, DOD will be better positioned to make more effective decisions regarding whether, when, and how to provide such training in the future.

Also, while DOD has related efforts to capture lessons learned from training Ukrainian forces, its components are not consistently documenting observations in the Joint Lessons Learned Information System. DOD has broad guidance that requires component organizations to record observations within 45 days. However, this guidance may not be known to all subordinate organizations because they have not consistently documented the requirement to capture and disseminate relevant observations from ongoing efforts to train Ukraine’s forces through the Joint Lessons Learned Information System. As a result, DOD’s lessons learned may not be comprehensive or timely, leading to missed opportunities for improvement.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following three recommendations to DOD:

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy, in coordination with the Director of DSCA, issues guidance that requires the combatant commands to identify resources necessary for training when proposing a security assistance package, including situations that require rapid execution of PDA. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Commander, U.S. European Command provides clear guidance to subordinate organizations on documenting approaches for assessing training provided to Ukrainian forces. Such guidance should include data elements and standards to ensure data quality.

(Recommendation 2)

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Commander, U.S. European Command directs subordinate organizations to capture and share relevant observations from ongoing efforts to train Ukraine’s forces through the Joint Lessons Learned Information System in a timely manner. These steps could include emphasizing the importance of recording observations in the Joint Lessons Learned Information System and requiring subordinate commands to develop clear implementing guidance that directs personnel to record observations in the Joint Lessons Learned Information System.

(Recommendation 3)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of the sensitive report to DOD for comment. The department’s comments on the sensitive report are reprinted in appendix II. In its comments, DOD agreed with our second and third recommendations, and stated it was committed to addressing both recommendations in a timely manner.

The department disagreed with our first recommendation. In its response, DOD stated that it provides guidance regarding a “total package approach” and specifically the inclusion of training as a part of security cooperation in DOD Directive 5132.03.[36] DOD stated that given the guidance in this DOD directive, our recommendation was redundant.

Specifically, DOD stated the directive instructs the Combatant Commands to assess foreign partner capabilities and develop approaches to building capabilities across the full spectrum of required inputs. These commands are also instructed to ensure that proposed materiel solutions are integrated with non-materiel solutions and with other security cooperation activities (e.g., combined exercises, military education and training, defense institution building) in their theater campaign plans to maximize the allied or partner nation’s ability and willingness to employ and sustain the capability.

Further, DOD stated the commands are to use comprehensive approaches that consider the full spectrum of capability development through the doctrine, organization, training, materiel, leadership, personnel, facilities, and policy framework as referenced in a Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff instruction. DOD stated that the directive also instructs the Secretaries of the Military Departments and the Chief of the National Guard Bureau to conduct military education and training in accordance with policies and criteria established by the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy and the Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA).

We agree that DOD provides some guidance regarding the inclusion of training in security cooperation activities. However, our report describes gaps in DOD’s existing guidance that hindered the department’s ability to plan and identify training needs for defense articles delivered to Ukraine. Specifically, DOD did not have detailed guidance to assist planners in applying a total package approach when using PDA in a crisis security assistance scenario. In particular, the expanded size, scope, and speed of equipment delivered under PDA since 2022 contributed to unanticipated challenges for U.S. Army units delivering training to Ukrainian forces. The lack of guidance resulted in training-related challenges that were not fully identified and resolved until after the security assistance package was approved and sent to the service components for execution. Further, the lack of clear guidance created ambiguity about which office was responsible for providing training to Ukraine’s forces. In some cases, DOD did not resolve these issues until multiple entities were on site to provide training.

As we reported above, DSCA’s Handbook for Foreign Assistance Act (FAA) Drawdown of Defense Articles and Services was the only guidance available to assist with the planning and execution of drawdowns under a PDA.[37] However, DOD officials told us the document was not designed to be widely accessible or applied across the department, and we found that it does not include certain information to address the use of PDA in a crisis security assistance scenario. Specifically, the handbook does not explain how to plan security assistance training in situations that require rapid execution, nor does it specify which offices or organizations are responsible for providing complete support packages for defense articles. For example, the guidance does not detail which DOD component is responsible for training decisions and how to obtain funding for training and maintenance of training equipment under PDA.

Our report also describes actions DOD components took to overcome challenges that arose when providing training to Ukrainian forces. However, the components took these actions in the absence of guidance to assist them in rapidly executing PDA during a crisis scenario. Issuing new or clarifying existing guidance that requires DOD components to identify the resources necessary for training when proposing a security assistance package, including situations that require rapid execution of PDA, will better position the department to avoid potential challenges providing training under a future use of PDA. Therefore, we believe the recommendation remains valid.

DOD also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretaries of Defense, State, the Army, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the Chief of the National Guard Bureau, and the Commander, U.S. European Command. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have questions about this report, please contact me at (202) 512-9627 or MaurerD@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix III.

Diana Maurer

Director, Defense Capabilities and Management

List of Committees

The Honorable Roger Wicker

Chairman

The Honorable Jack Reed

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

United States Senate

The Honorable Lindsey Graham

Chairman

The Honorable Jeff Merkley

Ranking Member

Committee on the Budget

United States Senate

The Honorable James Risch

Chairman

The Honorable Jeanne Shaheen

Ranking Member

Committee on Foreign Relations

United States Senate

The Honorable Rand Paul, M.D.

Chairman

The Honorable Gary C. Peters

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

United States Senate

Chair

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Defense

Committee on Appropriations

United States Senate

Chair

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs

Committee on Appropriations

United States Senate

The Honorable Mike Rogers

Chairman

The Honorable Adam Smith

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

House of Representatives

The Honorable Jodey Arrington

Chairman

The Honorable Brendan Boyle

Ranking Member

Committee on the Budget

House of Representatives

The Honorable Brian Mast

Chairman

The Honorable Gregory Meeks

Ranking Member

Committee on Foreign Affairs

House of Representatives

The Honorable James Comer

Chairman

The Honorable Gerald E. Connolly

Ranking Member

Committee on Oversight and Government Reform

House of Representatives

The Honorable Ken Calvert

Chairman

The Honorable Betty McCollum

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Defense

Committee on Appropriations

House of Representatives

The Honorable Mario Diaz-Balart

Chairman

The Honorable Lois Frankel

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on National Security, Department of State, and Related Programs

Committee on Appropriations

House of Representatives

This report (1) describes the processes the Department of Defense (DOD) has used to provide Ukrainian forces with training on defense articles and examines the challenges DOD experienced when providing this training, (2) evaluates the approaches DOD has used to assess the training it has provided to Ukrainian forces and to document and disseminate lessons learned since the Russian invasion, and (3) describes the effect that the training of Ukrainian forces has had on DOD’s European training facilities and the readiness of U.S. units that supported that training.

This report is a public version of the prior sensitive report that we issued in November 2024.[38] DOD deemed some of the information in the prior report as Controlled Unclassified Information (CUI), which must be protected from public disclosure. Therefore, this report omits CUI information and data related to the number of Ukrainians that DOD trained, challenges and readiness effects that U.S. Army units experienced when providing the training, and factors that hindered DOD components’ ability to assess the training provided to Ukrainian forces. Although the information provided in this report is more limited in scope, it addresses the same objectives as the sensitive report. Also, the methodology used for both reports is the same.

To address these objectives, we reviewed the training DOD provided to conventional Ukrainian forces at U.S. training areas in Europe, including training for defense articles, collective training for Ukrainian units, and leadership training. DOD provided defense articles primarily through Presidential Drawdown Authority (PDA) and the Ukraine Security Assistance Initiative (USAI).[39]

For our first objective, we reviewed DOD and Department of State security assistance guidance to understand the processes that are used in security assistance activities. Specifically, we reviewed directives and guidance governing the processes to deliver defense articles to Ukraine, including DSCA’s Security Assistance Management Manual and the DSCA Handbook for Foreign Assistance Act (FAA) Drawdown of Defense Articles and Services.[40] We also reviewed U.S. Army Regulation 12-15, Joint Security Cooperation, Education, and Training.[41] We compared the crisis security assistance processes with aspects of pre-invasion or deliberate security assistance; we also compared the execution of security assistance in relation to other military operations.