SMALL BUSINESS RESEARCH PROGRAMS

Clearer Guidance Could Improve Award Data to More Effectively Measure Outcomes

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional committees.

For more information, contact: Hilary M. Benedict at benedicth@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

In fiscal year (FY) 2023, about 50 percent of all Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) program awards were from open topics—totaling about $2.2 billion—with the remaining awards from conventional topics. There are two types of topics: open or conventional. For solicitations that include open topics, agencies provide broad topics, and small businesses submit proposals that identify research needs and propose a solution. For solicitations that include conventional topics, agencies define research needs, and small businesses respond with proposed solutions. GAO found that open topic awards may promote competition, as these awards attracted more first-time applicants compared with conventional topics. Of the 11 agencies that participated in the SBIR and STTR programs in FY 2023, four exclusively issued open topic awards, four exclusively issued conventional topic awards, and the remaining three issued both types of awards.

The SBIR and STTR Extension Act of 2022 required the Small Business Administration (SBA), which oversees the programs, to collect and report data on open and conventional topics. However, GAO found that participating agencies categorized their open and conventional topics inconsistently in FY 2023. For example, more than one-third of solicitations released by three agencies with conventional topic labels were as broad as solicitations labeled open topics from other agencies.

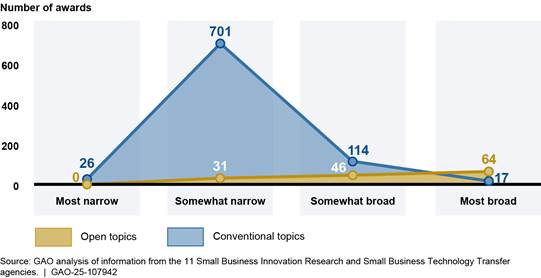

Analysis of Open and Conventional Topics Across the

11 Small Business Innovation Research and Small Business Technology Transfer

Agencies, Fiscal Year 2023

This inconsistency is due, in part, to current SBA guidance, which does not define open and conventional topics or clearly distinguish how they differ. Without clear and documented government-wide definitions, agencies may continue to interpret and label topic types differently, which limits the comparability of data across agencies and usefulness of SBA’s data. This, in turn, may hinder SBA’s ability to assess program performance and the outcomes associated with different topic types, as well as Congress’s ability to effectively oversee the SBIR and STTR programs.

Why GAO Did This Study

To help drive economic growth, agencies provide SBIR and STTR awards to small businesses, which otherwise may encounter difficulty funding research and development. For these awards, agencies release solicitations that include open and conventional topics.

The SBIR and STTR Extension Act of 2022 includes provisions for GAO to review agencies’ use of open topics. This report examines the extent to which agencies issued open topic awards in FY 2023 (the most recent data available at the time of GAO’s review) and how agencies’ FY 2023 topics compared in terms of specificity, among other objectives.

GAO analyzed data from 11 participating agencies and SBA for over 33,000 awards issued from FY 2019 through FY 2023—the most recent data available at the time of GAO’s review. To compare topic specificity across participating agencies, GAO analyzed nearly 1,000 topics that the participating agencies released in their FY 2023 solicitations and assessed how specific each topic was. GAO also reviewed statutory requirements and interviewed agency officials and 22 randomly selected small businesses.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making a recommendation to SBA to develop formal definitions for open and conventional topics and provide that guidance to participating agencies to encourage the consistent categorization of topic types in SBIR and STTR solicitations. SBA concurred with GAO’s recommendation.

Abbreviations

DOD Department of Defense

DOE Department of Energy

DHS Department of Homeland Security

DOT Department of Transportation

EPA Environmental Protection Agency

FY fiscal year

HHS Department of Health and Human Services

NASA National Aeronautics and Space Administration

NIH National Institutes of Health

NSF National Science Foundation

R&D research and development

SBA Small Business Administration

SBIR Small Business Innovation Research

STTR Small Business Technology Transfer

UEI unique entity identifier

USDA U.S. Department of Agriculture

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

September 23, 2025

Congressional Committees

Small businesses are important drivers of U.S. economic growth but can encounter difficulty accessing capital to fund research and development (R&D), which may ultimately impede their technological innovations. Congress established the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) programs to enable small businesses to undertake and obtain the benefits of R&D.[1] Since SBIR was established in 1982, followed by STTR in 1992, the programs have issued over $77 billion in awards to over 33,000 small businesses, as of July 2025.[2] The SBIR and STTR programs aim to:

· stimulate technological innovation,

· meet federal R&D needs,

· foster diverse participation in innovation and entrepreneurship, and

· increase private-sector commercialization of innovations derived from federal R&D funding.[3]

The Small Business Act, as amended, requires certain federal agencies to participate in these programs. More specifically, federal agencies with an extramural research or R&D budget greater than $100 million are required to participate in the SBIR program, and agencies with such obligations greater than $1 billion are required to also participate in the STTR program.[4] Each agency manages its own program, while the Small Business Administration (SBA) oversees the programs, including issuing policy directives and required reports. Eleven federal agencies and their components participate in the SBIR program or in both the SBIR and STTR programs.[5] In fiscal year (FY) 2023, participating agencies issued approximately $4.5 billion in new SBIR and STTR awards, according to our analysis of SBA data. Agencies generally make SBIR and STTR awards in the form of grants, contracts, cooperative agreements, or other transaction agreements.[6]

Participating agencies provide SBIR and STTR awards to small businesses to meet agency mission needs for R&D in an array of different technology areas. In some cases, these mission needs focus on supporting R&D that would ultimately benefit entities beyond the agency, such as the American public at large. Examples of R&D that could benefit the American public include technologies to remotely monitor air pollution or to detect pathogens in real time. In other instances, agencies focus on advancing technologies to be used by the agencies themselves, such as technology to autonomously track space objects above Earth.

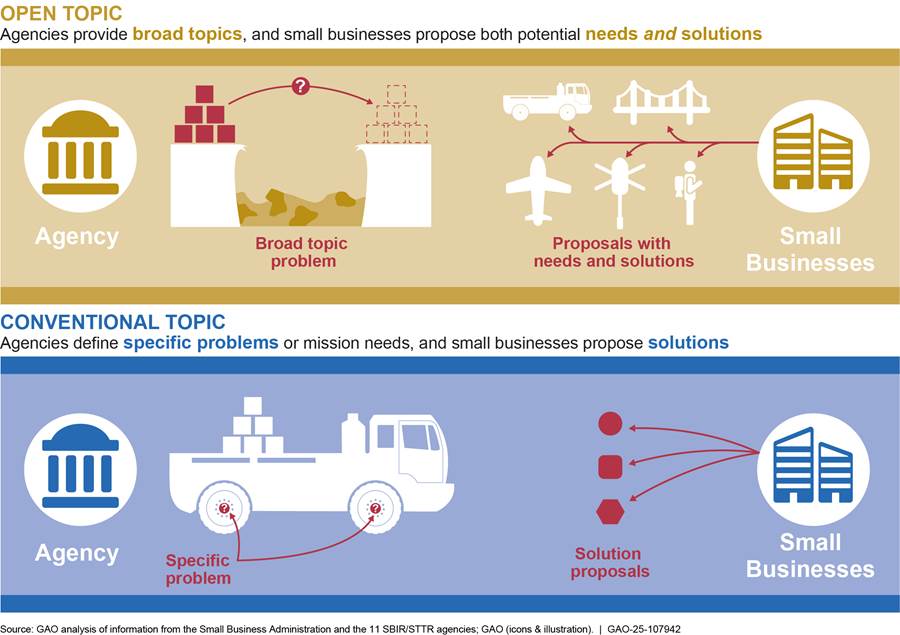

To meet these mission needs, participating agencies solicit proposals from small businesses in one or more annual cycles. Solicitations include topics, which generally take two forms: open or conventional. Neither the authorizing legislation for the SBIR and STTR programs nor SBA’s policy directive, which provides more specific direction for agencies in implementing these programs, currently defines open and conventional topics.[7] Therefore, in a 2023 report, we developed definitions of these topic types for the purposes of our analysis and reporting by coordinating with participating agencies.[8] See figure 1 for an illustration of how open and conventional topics differ, using definitions we developed in 2023.

Figure 1: Open and Conventional Topics in Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) Programs, Based on GAO Definitions

The SBIR and STTR Extension Act of 2022 includes a provision for us to issue a series of reports comparing several aspects of open and conventional topics.[9] This is our third report on this issue. In our first report, published in September 2023, we found that participating agencies used open topics to fund about 40 percent of their SBIR and STTR awards from FY 2019 through FY 2021.[10] In our second report, published in September 2024, we found that some Department of Defense (DOD) components’ open topics were similar to their conventional topics, and we recommended DOD revise its open topic guidance to clarify how open and conventional topics should differ.[11]

This report examines:

1. the number and dollar amount of SBIR and STTR awards from open topics participating agencies issued in FY 2023;

2. how participating agencies’ FY 2023 open and conventional topic awards compare—in terms of competition, participation of nontraditional small businesses (described in statute as including those owned by women, minorities, and veterans), first-time applicants, first-time awardees, the amount of time agencies took to notify applicants of outcomes and issue awards, and commercialization of technologies—and factors that account for any differences;[12] and

3. how agencies’ FY 2023 open and conventional topics compare in terms of specificity.

To address our objectives, we obtained documentary and testimonial evidence from SBA, participating agencies, and small businesses. We interviewed representatives from 22 randomly selected small businesses and one organization that represents small businesses (the Small Business Technology Council) about open and conventional topics, the amount of time agencies took to notify applicants of outcomes and issue awards, and other SBIR and STTR issues.[13] In addition, we interviewed officials or collected written responses from agency officials responsible for administering SBIR and STTR programs about each agency’s use of open topics. We identified and evaluated relevant criteria, including SBA’s policy directive and the SBIR and STTR Extension Act of 2022, and applied the criteria, as appropriate.

For objectives 1 and 2, we expanded on our prior analysis of the 11 participating agencies’ awards from FY 2019 through FY 2022 by collecting and analyzing award data for FY 2023 from SBA.[14] We ended our analysis with FY 2023 award data because it was the most recent year with sufficiently reliable data available at the time of our review. We also analyzed: (1) SBA company registry data as of February 2025, (2) General Services Administration System for Award Management registration data on veteran ownership for FY 2023, and (3) SBA data on businesses’ progression through different phases (technology development through commercialization) for which agencies provided awards from FY 2019 through FY 2023.[15] We assessed the reliability of the data and collected additional information from agencies, as necessary, to make changes to improve data reliability. For example, we collected written responses from agencies to clarify and adjust for inconsistencies or other issues we identified. We determined the data elements we used to be sufficiently reliable for purposes of this report.

For objective 3, we examined participating agencies’ open and conventional topic efforts during FY 2023. More specifically, we analyzed 492 topics for 10 participating agencies (all but DOD) by anonymizing then scoring each topic from most narrow (i.e., most specificity in defining needs and solutions) to most broad (i.e., least specificity in defining needs and solutions). We also incorporated our analysis of 507 DOD topics from our September 2024 report.[16] For more information on our scope and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from November 2024 to September 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

This section identifies the federal agencies that participate in the SBIR and STTR programs and describes the programs’ general eligibility requirements, the awards process, including SBA’s SBIR and STTR policy directive time frames for notifying applicants of awards and issuing awards, and award limits.

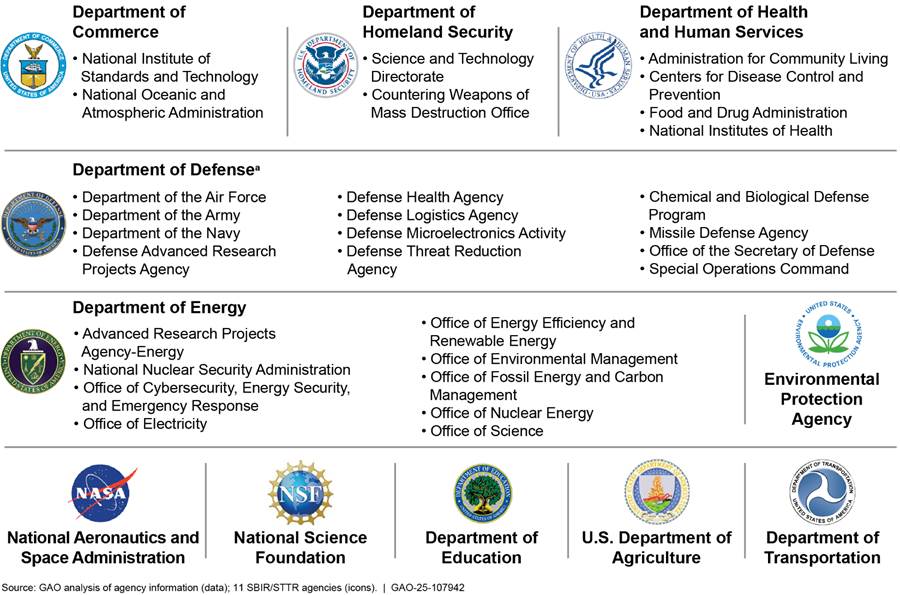

Participating Agencies

The 11 participating agencies differ in how they implement their SBIR and STTR programs. Some agencies develop solicitation topics and decide whether topics will be open or conventional at the agency level. Other agencies develop topics at the component level. At some agencies, certain components may develop solicitation topics while different components review proposals or issue awards. Figure 2 depicts the 11 participating agencies and their components that developed topics for SBIR and STTR program awards from FY 2019 through FY 2023.

Figure 2: Eleven Agencies Participating in the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) Programs

Agencies and components shown developed solicitation topics from fiscal year 2019 through fiscal year 2023

Note: From fiscal year 2019 through fiscal year 2023, all 11 agencies participated in SBIR. From fiscal year 2019 through fiscal year 2023, six of those agencies also participated in STTR (Departments of Agriculture, Defense, Energy, Health and Human Services; National Aeronautics and Space Administration; and National Science Foundation). The Department of Agriculture began participating in STTR in fiscal year 2023.

aIn addition to the Department of Defense components listed, the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, the Strategic Capabilities Office, and the Space Development Agency also participate in the SBIR or STTR programs. However, according to agency officials, the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency and Strategic Capabilities Office issue topics through the Office of the Secretary of Defense, while the Space Development Agency issues topics through the Department of the Air Force.

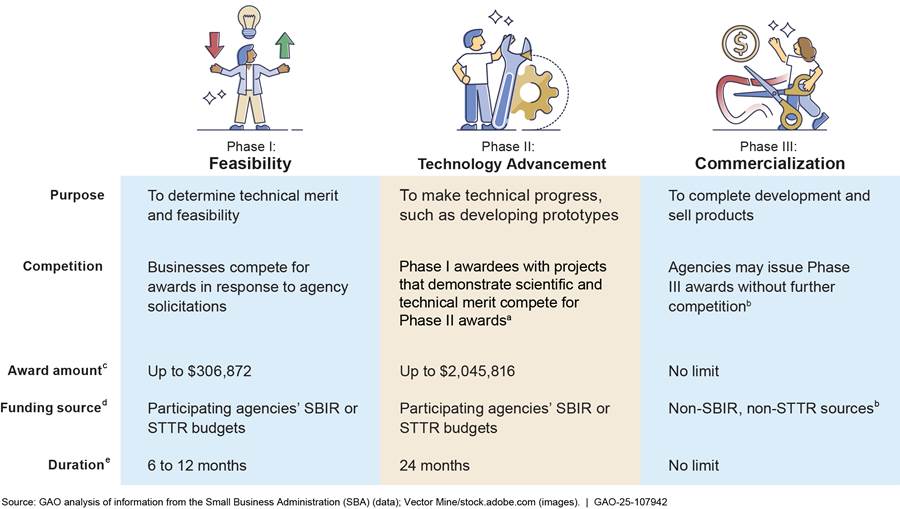

Program Time Frames, Award Limits, and Eligibility

SBA developed and periodically updates a policy directive to guide how agencies operate their SBIR and STTR programs; the most recent update was in 2023.[17] According to SBA’s policy directive, each participating agency is to issue a solicitation requesting proposals from small businesses that address certain topics, at least annually. Each participating agency is then to take the following steps:

1. review the proposals it receives,

2. determine which small businesses should receive awards,

3. notify pending awardees within the time frames required in SBA’s SBIR and STTR policy directive, and

4. issue awards within the time frames recommended in SBA’s SBIR and STTR policy directive.

Under SBA’s policy directive, most agencies must notify applicants of award decisions within 90 calendar days after a solicitation closes.[18] The directive provides that most agencies should issue awards within 180 days after the solicitation closes.[19]

Participating agencies then issue awards for three phases of technology development: feasibility (phase I), technology advancement (phase II), and commercialization (phase III) (see fig. 3). To be eligible for awards, businesses must be primarily U.S.-owned for-profit firms that have 500 or fewer employees. Small businesses can collaborate with other organizations through subcontracting to meet project needs, subject to program eligibility requirements. For example, small businesses can subcontract up to 33 percent of a SBIR Phase I project and 50 percent of a SBIR Phase II project to a consultant, a subcontractor, or both. Some agencies issue Direct-to-Phase-II SBIR awards to businesses that did not receive a Phase I award but completed equivalent work using non-SBIR, non-STTR funds.[20] However, in general, Phase I is the entry point to the program for small businesses.

Figure 3: Phases of the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) Programs

aThe Department of Defense, Department of Education, and Department of Health and Human Services’ National Institutes of Health are authorized to issue Direct-to-Phase-II SBIR awards through fiscal year 2025 to businesses that did not receive a Phase I award but completed equivalent work using non-SBIR, non-STTR funds, following a determination by the agency head that the small business has determined the scientific and technical merit and feasibility of the project. 15 U.S.C. § 638(cc).

bPhase III funding can also come from nonfederal sources of capital, and Phase III awards funded with federal non-SBIR or STTR funding can also be used for the continuation of research or R&D that has been competitively selected using peer review or merit-based selection procedures. 15 U.S.C. § 638(e)(4)(C), (e)(6)(C).

cAuthorized award amounts are accurate as of October 2023 to match the scope of our review. Maximum award amounts include any modifications to the original award amount. Agencies may seek a waiver from SBA to issue awards above the maximum values.

dSBIR or STTR budget refers to the portion of an agency’s extramural research or R&D budget designated for the SBIR or STTR programs.

eAgencies may provide longer performance periods where appropriate for particular projects.

Agencies Used Open Topics to Fund Slightly More Awards in FY 2023, and Use of Topic Types Stayed Consistent with Earlier Years

According to our analysis of SBA and participating agency award data, agencies used open topics to fund about 50 percent of all SBIR and STTR awards in FY 2023, slightly higher than their use of open topics in FY 2019 through FY 2022. In FY 2023, agencies used the same topic types and funding mechanisms (e.g., contracts, grants, cooperative agreements, or other transaction agreements) as they did in FY 2022, and the typical customers, such as the participating agency or customers outside the participating agency, for the topics remained consistent with earlier years for 10 of the 11 participating agencies.

Agencies Used Open Topics to Fund About Half of FY 2023 Awards, a Slight Increase from Recent Years

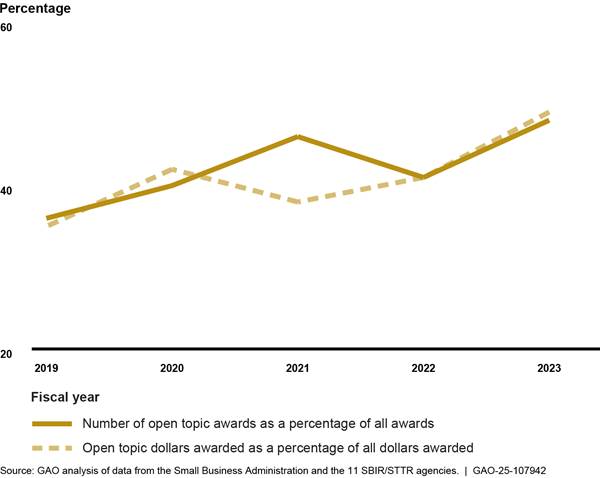

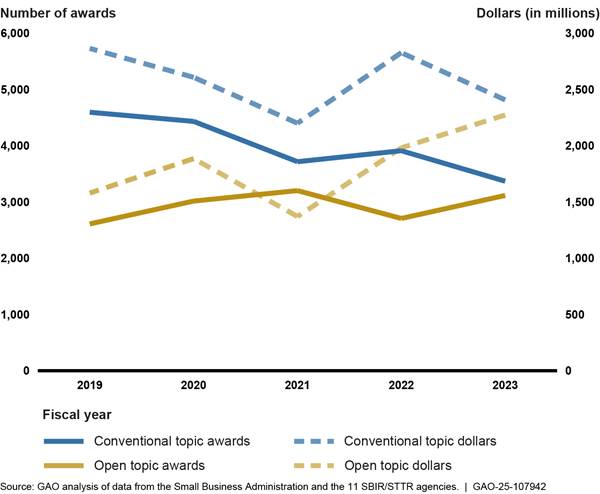

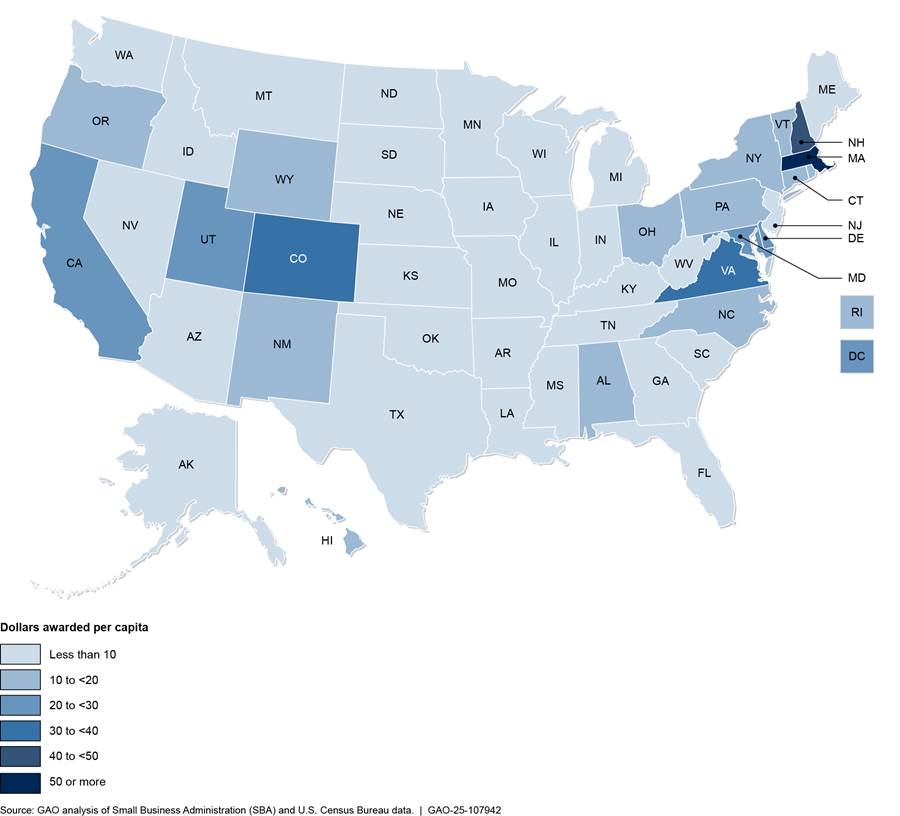

Agencies used open topics to fund about 50 percent of all SBIR and STTR awards in FY 2023—higher than their use of open topics from FY 2019 through FY 2022—according to our analysis of SBA and agency award data (see fig. 4). Specifically, of the approximately $4.5 billion total SBIR and STTR awards issued in FY 2023, agencies funded approximately $2.2 billion in open topic awards. In contrast, from FY 2019 through FY 2022, agencies used open topics to fund an average of about 40 percent of awards. For additional award information, including total awards from FY 2019 through FY 2023 and dollars awarded by state in FY 2023, see appendix II.

Notes: This includes Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) award data. In fiscal year 2021, the Department of Defense increased the number of open topic awards as a percentage of all awards, while the agency did not change its open topic dollars awarded as a percentage of all dollars awarded.

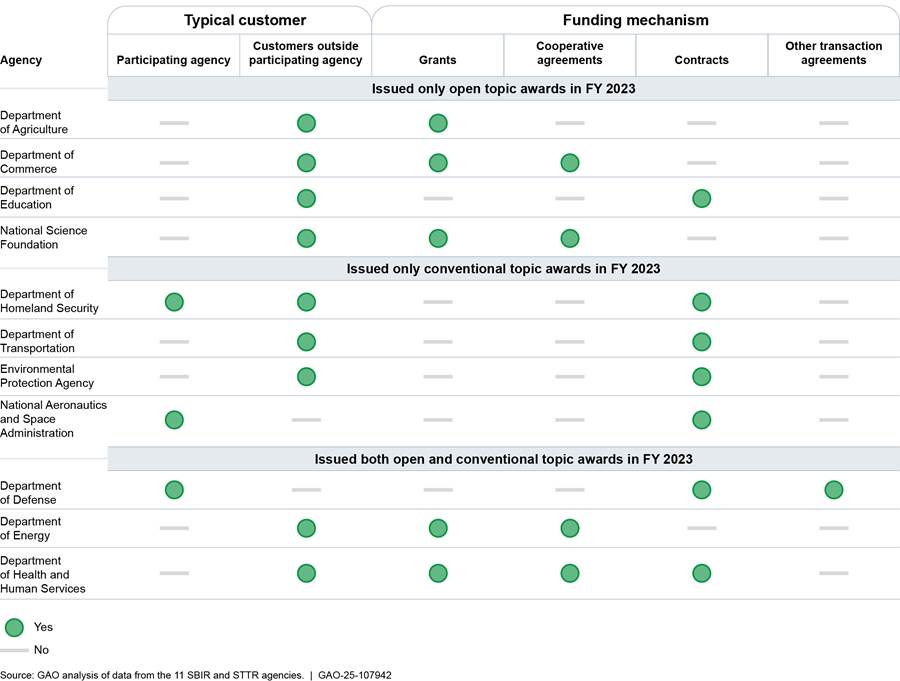

In FY 2023, four participating agencies exclusively issued open topic awards, four issued no open topic awards (i.e., they exclusively issued conventional topic awards), and the remaining three issued both open and conventional topic awards (see table 1).

Table 1: Participating Agencies’ Use of Open Topic Awards in the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) Programs, Fiscal Year 2023

|

|

Number of awards |

Dollars awarded |

||||

|

Agency |

Open topic awards |

Total awards |

Percentage |

Open topic dollars awarded (in millions) |

Total dollars awarded (in millions) |

Percentage |

|

Department of Agriculture |

119 |

119 |

100% |

$39.7 |

$39.7 |

100% |

|

Department of Commerce |

62 |

62 |

100% |

$19.2 |

$19.2 |

100% |

|

Department of Education |

24 |

24 |

100% |

$12.8 |

$12.8 |

100% |

|

National Science Foundation |

420 |

420 |

100% |

$214.4 |

$214.4 |

100% |

|

Department of Defense |

1,299 |

3,161 |

41% |

$917.4 |

$2,322.6 |

39% |

|

Department of Energya |

68 |

581 |

12% |

$22.0 |

$306.4 |

7% |

|

Department of Health and Human Services |

1,035 |

1,392 |

74% |

$950.0 |

$1,349.6 |

70% |

|

Department of Homeland Security |

0 |

37 |

0% |

$0 |

$19.1 |

0% |

|

Department of Transportation |

0 |

23 |

0% |

$0 |

$10.3 |

0% |

|

Environmental Protection Agency |

0 |

33 |

0% |

$0 |

$5.7 |

0% |

|

National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

0 |

455 |

0% |

$0 |

$182.5 |

0% |

|

Total |

3,027 |

6,307 |

48% |

$2,175.8 |

$4,482.2 |

49% |

Source: GAO analysis of data from the Small Business Administration and the 11 SBIR and STTR agencies. | GAO 25-107942

Note: Information includes SBIR and STTR awards. Data for the number of awards and dollars awarded were from the Small Business Administration; data on topic type were provided by the participating agencies. All 11 agencies participated in SBIR, and six of the agencies participated in STTR in fiscal year 2023. Award amounts are rounded to the nearest $100,000. Percentages are rounded to the nearest 1 percent.

aSome Department of Energy solicitation topics contain multiple distinct topics, called subtopics. Some Department of Energy open topic awards originated from solicitation topics that included both open and conventional subtopics.

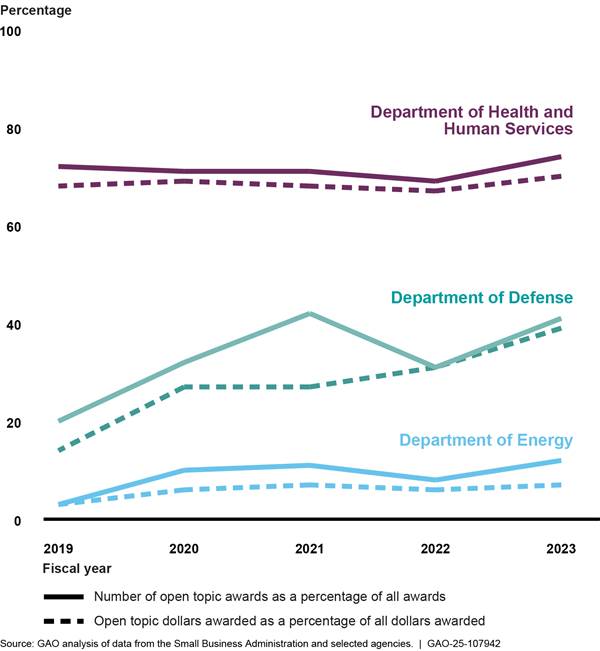

The three agencies that issued both open and conventional topic awards—DOD, the Department of Energy (DOE), and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)—differed over time in the proportion of total awards that they issued from open topics. However, the agencies issued more open topic awards in FY 2023 compared to FY 2022, as shown in figure 5.

Figure 5: Selected Agencies’ Open Topic Awards in Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) Programs, by Year, Fiscal Years 2019–2023

Note: Selected agencies are those that issued both open and conventional topic awards through SBIR or STTR in fiscal year 2023.

DOD issued over half of all SBIR and STTR awards in FY 2023 and increased its use of open topics from about 30 percent in FY 2022 to 40 percent in FY 2023. According to DOD officials, this increase was because the SBIR and STTR Extension Act of 2022 required participating DOD components to release at least one open topic solicitation per fiscal year beginning with solicitations issued in FY 2023.[21] We previously found that all 12 relevant DOD components released at least one open topic solicitation in FY 2023, in compliance with the act.[22]

Topic Type, Funding Mechanism, and Customers in FY 2023 Were Largely Consistent with Earlier Years

All agencies used the same topic types and funding mechanisms from FY 2022 through FY 2023. Typical customers of an award’s future product were largely consistent from FY 2022 through FY 2023.

Topic type. From FY 2022 through FY 2023, all agencies were consistent in their approaches to using open and conventional topics. Agencies that issued only open or conventional topics continued their use of one topic type, while agencies that issued both open and conventional topics continued to issue both topic types.

Funding mechanism. Agencies used different funding mechanisms to fund a range of technologies. Examples include grants, cooperative agreements, contracts, and other transaction agreements. All agencies were consistent in their use of funding mechanisms from FY 2022 through FY 2023.

Customer. Ten of the 11 participating agencies had the same typical customers (i.e., we define a customer as an end user of the technology that the SBIR or STTR award resulted in) from FY 2022 through FY 2023. Specifically, in addition to the agency itself being a typical customer, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) added customers external to the department, such as first responders, as typical customers for its awards. According to small business representatives we interviewed, customers can include government agencies (e.g., local or federal agencies) or nongovernment customers (e.g., farmers, engineering firms, or chemical manufacturing companies). According to DOE and HHS officials, the typical customer did not differ between its awards from open and conventional topics in FY 2023. We previously found some differences between DOD’s open and conventional topics in the extent to which they identified specific potential DOD or non-DOD customers.[23]

See figure 6 for more information on topic types, customers, and funding mechanisms as of FY 2023.

Figure 6: Participating Agencies’ Award Types, Typical Customers, and Funding Mechanisms in the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) Programs, as of Fiscal Year (FY) 2023

Open Topics May Increase Competition, While Other Observed Differences Do Not Follow a Clear Trend

Compared to conventional topics, open topics may increase competition, according to our analyses of several indicators. However, we found that while the three agencies that issued both open and conventional topic awards—DOD, DOE, and HHS—differed on other factors such as the amount of time agencies took to notify applicants and issue awards, nontraditional small business participation, technology type, and commercialization, differences between topic types on these factors did not follow a clear trend. We also found that these agencies provided a variety of outreach and assistance to small businesses. Some of the outreach and assistance included information about open topics or were targeted to new or nontraditional businesses.

Open Topics Had a Higher Level of Competition than Conventional Topics in FY 2023

Our analysis of several indicators showed that open topics had a higher level of competition than conventional topics in FY 2023. This is consistent with our findings from prior years.[24] We previously found that competition is a key tool for achieving the best return on investment for taxpayers.[25] We analyzed several competition indicators, including applicant acceptance rate, number of proposals received, and number of first-time applicants and awardees.

Applicant acceptance rate. Of the three agencies that issued both open and conventional topic awards in FY 2023, all had a lower applicant acceptance rate for open topics than for conventional topics (see table 2). A lower applicant acceptance rate—the percentage of proposals that resulted in an award—is an indicator of higher competition. These data suggest that open topics increased competition more than conventional topics did for these agencies. For a previous report, officials from one participating agency told us that increased competition could, in part, result in more innovative proposals.[26]

Table 2: Selected Agencies’ Applicant Acceptance Rates for Open and Conventional Topics in the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) Programs, Fiscal Year 2023

|

|

Open topic awards |

Conventional topic awards |

||

|

Agency |

Number of proposals |

Acceptance rate |

Number of proposals |

Acceptance rate |

|

Department of Defense |

8,281 |

16% |

7,742 |

24% |

|

Department of Energy |

411 |

17% |

1,659 |

31% |

|

Department of Health and Human Services |

5,493 |

19% |

1,262 |

28% |

Source: GAO analysis of data from selected agencies and the Small Business Administration . | GAO‑25‑107942

Note: Selected agencies are those that issued both open and conventional topic awards through SBIR or STTR in fiscal year 2023. Percentages are rounded to the nearest 1 percent. Acceptance rate is the percentage of proposals that resulted in an award. Data for the number of proposals were provided by selected agencies; data for the number of awards were from the Small Business Administration.

However, as we previously found, several factors could influence the applicant acceptance rate, including the number of proposals received and agency R&D priorities.[27] For example, according to DOD and DOE officials, proposals submitted under open topics may not always align with agency priorities, which can reduce the applicant acceptance rate for open topics. Additionally, while the applicant acceptance rate captures the level of competition for funding, competition is multidimensional. For example, a DHS official said that when an agency releases a conventional topic solicitation, it can receive multiple solutions for the same challenge, which allows the agency to select the best fit for its needs. In contrast, when an agency releases an open topic solicitation, it will likely only receive one proposal to address a particular challenge.

Number of proposals received. Both DOD and HHS received more proposals in response to open topics versus conventional topics in FY 2023, while DOE received more proposals in response to conventional topics. However, in FY 2023, all three agencies released significantly more conventional topics—DOD released around 12 times more conventional topics than open topics, DOE released around 6 times more, and HHS released around 10 times more. Program officials from all three agencies told us that open topics generally receive more proposals than conventional topics. This aligns with the views of SBA officials. Similarly, several small business representatives we interviewed believed that open topics attracted more applicants and were more competitive. One reason for this may be that a wide range of technologies can be submitted in response to open topics, according to SBA officials.

Number of first-time applicants and awardees. Agencies received more applications from first-time applicants, and issued more awards to first-time awardees, for open topics than conventional topics.[28] Based on our prior work, a higher rate of new businesses receiving awards is another indicator of increased competition. In FY 2023, DOD and DOE received a higher percentage of applications to open topics than conventional topics from first-time applicants. Officials from the National Institutes of Health (NIH)—the HHS component that issued over 95 percent of HHS awards in FY 2023—stated that data on first-time applicants were not readily available for FY 2023. According to NIH officials, the agency prioritizes tracking first-time awardees over first-time applicants since reporting on first-time applicants is not required.

In FY 2023, the three agencies also issued a higher percentage of open topic awards to first-time awardees than conventional topic awards. SBA officials said that because open topics tend to receive more applications, these topics can also attract new applicants to the program.

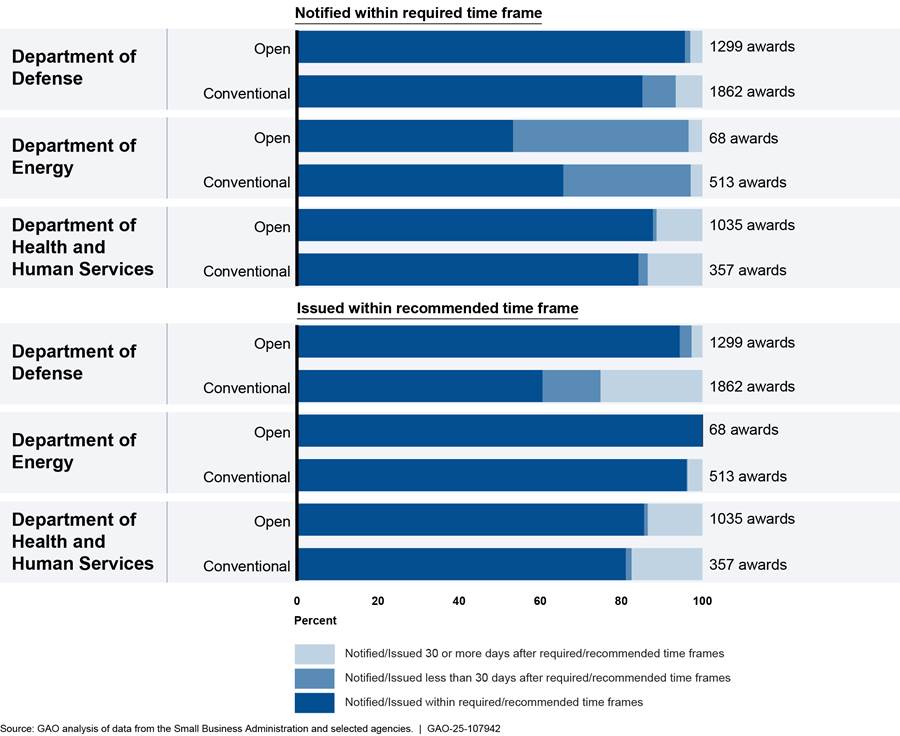

Amount of Time to Notify and Fund Small Businesses Varies Across Agencies and by Topic Type

In FY 2023, there was significant variation in the amount of time it took agencies to notify applicants whether they were receiving awards and to issue awards (i.e., finalize the funding agreement with the small business).[29] We found that across all 11 agencies, agencies notified applicants within required time frames more often for conventional topic awards than open topic awards, while agencies issued awards within recommended time frames more often for open topic awards. See appendix III for more information on the amount of time to notify applicants of outcomes and issue awards at the 11 participating agencies.

Some agencies notified applicants within required time frames less often in FY 2023 compared to FY 2022. For example, DOE notified applicants within the required time frame for 53 and 66 percent of open and conventional topic awards, respectively, in FY 2023, compared to 86 percent and 99 percent in FY 2022. For our November 2024 report, SBA officials told us that the delays were due, in part, to implementing new due diligence programs, which require agencies to assess foreign risks associated with small businesses.[30] DOE requested and received waivers from SBA to extend the notification date because the agency was unable to meet the 90-day notification period.

Differences in the amount of time to notify applicants of outcomes and issue awards between topic types varied across the agencies that issued both open and conventional topic awards in FY 2023 (see fig. 7). Of the three agencies, DOD and HHS had statistically significant differences between open and conventional topic awards for the amount of time to notify applicants of outcomes and issue awards; see appendix III for more information on statistically significant differences between the amount of time to notify applicants of outcomes and issue awards for open and conventional topic awards.[31] The agencies notified applicants within required time frames and issued awards within recommended time frames more often for open topic awards. For example, DOD issued around 60 percent of conventional topic awards within the recommended time frame, compared to 94 percent of open topic awards.

Of the DOD components that issued both open and conventional topic awards in FY 2023, the Air Force—which issued over 50 percent of DOD awards in FY 2023—had the greatest difference in the amount of time to issue awards. The Air Force issued 98 percent of open topic awards within the recommended time frame, compared to just 36 percent of conventional topic awards. According to DOD officials, this is due to different contracting strategies. The Air Force issues open topic contract awards internally via AFWERX—an organization within the Air Force with a mission of accelerating the transition of cutting-edge capabilities into the hands of members of the Air Force. AFWERX sets aside time during which contracting personnel focus solely on issuing open topic awards, allowing for faster award timelines. In contrast, conventional topic awards are issued by the sponsoring organization, not AFWERX.

Figure 7: Amount of Time to Notify Applicants of Outcomes and Issue Awards for Selected Agencies in the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) Programs, Fiscal Year 2023

Note: Selected agencies are those that issued both open and conventional topic awards through SBIR or STTR in fiscal year 2023. SBA’s 2023 policy directive requires these agencies to notify businesses within 90 calendar days after a solicitation closes, except the National Institutes of Health (NIH) within the Department of Health and Human Services, which has 1 year to notify businesses. SBA’s policy directive also provides that these agencies should issue an award within 180 calendar days after a solicitation closes, except NIH, which has 15 months. We did not consider cases where agencies requested and were granted waivers from SBA as on-time notifications. Awards with missing data on notification or issuance are not included in the denominators for percentage calculations.

DOD and HHS notified applicants within required time frames and issued awards within recommended time frames significantly more often for open topic awards. However, there was not a statistically significant difference between open and conventional topic awards for the amount of time to notify applicants of outcomes and issue awards for DOE in FY 2023. The agency notified applicants within the required time frame more often for conventional topic awards but issued awards within the recommended time frame more often for open topic awards. Without a consistent trend across these agencies, it is difficult to determine whether agencies’ use of open or conventional topics is related to the amount of time it took to notify applicants or issue awards, even when limiting the analysis to those agencies that used both topic types. For our September 2024 report, agency officials told us that several factors could affect the amount of time it took to notify applicants or issue awards, such as the number of proposals received and the number of available reviewers with expertise in specific technology areas.[32]

Small business representatives we interviewed provided different views on the amount of time to notify applicants of outcomes and issue SBIR and STTR awards. While several thought that the amount of time was comparable to other funding sources (such as other federal non-SBIR, non-STTR sources or the private sector), others said the application process was longer. Agency delays, particularly from published time frames, can cause challenges for small businesses. For example, representatives from two small businesses said that they had experienced a situation where the agency was delayed in issuing an award but did not delay the start of the award. This compressed the businesses’ work and, according to one of the representatives, likely reduced the work’s quality. Officials from one participating agency said that they believe this situation is uncommon because the agency has historically adhered to a schedule. Officials from another participating agency said that they understand small businesses’ concerns when awards are delayed and use award extensions to support the businesses.

Once a small business is notified that it did not win an award, feedback provided by agencies can help the small business improve future proposals. However, several small business representatives we interviewed said that feedback provided by certain agencies was not helpful because it was limited or too general. For example, feedback from one agency component was limited to one or two generic sentences for each of the three evaluation criteria. Further, the feedback was general and did not include content specific to the business’s proposal. According to the component’s templates for providing feedback to small businesses, applicants are not given additional feedback on proposals submitted to open topics. They can request individualized feedback for proposals submitted to conventional topics, but this feedback is not guaranteed. This is consistent with the views of a few small business representatives, who said that some agencies may provide better feedback on proposals submitted to conventional topics than to open topics, potentially because agencies may be more likely to have reviewers with experience relevant to these narrower subject areas.

Other Award Aspects, Including Nontraditional Business Participation, Vary by Agency and Topic Type

While agencies differed on nontraditional small business participation, technology type, and commercialization, differences between topic types within the agencies that issue both open and conventional topic awards varied with no clear trend.

Nontraditional Small Business Participation

The SBIR and STTR Extension Act of 2022 referred to “non-traditional small business concerns” as including those owned by “women, minorities, and veterans.”[33] In our analysis, we found no consistent differences in nontraditional small business participation between topic types in FY 2023 (see table 3). We analyzed data on three types of nontraditional small businesses (owned by individuals from socially and economically disadvantaged groups, women-owned, and veteran-owned) at the three agencies that issued both open and conventional topic awards that year.[34] We found that:

· DOD issued a higher percentage of open topic awards to nontraditional small businesses, compared to conventional topic awards, which is consistent with prior years.[35] This difference was statistically significant.

· HHS issued a higher percentage of conventional topic awards to nontraditional small businesses, compared to open topic awards, which is consistent with prior years. This difference was statistically significant.

· For DOE, we did not find a statistically significant difference between topic type for awards to nontraditional small businesses. In FY 2023, DOE issued a higher percentage of open topic awards to nontraditional small businesses, compared to conventional topic awards. This is consistent with FY 2019 through FY 2021, though not with FY 2022.

Table 3: Open and Conventional Topic Awards Selected Agencies Made to Nontraditional Small Businesses in the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) Programs, Fiscal Year 2023

|

|

Open topic awards |

Conventional topic awards |

||

|

Agency |

Number of awards to nontraditional small businesses |

Percentage of awards to nontraditional small businesses |

Number of awards to nontraditional small businesses |

Percentage of awards to nontraditional small businesses |

|

Department of Defensea |

378 |

29% |

390 |

21% |

|

Department of Energy |

18 |

26% |

109 |

21% |

|

Department of Health and Human Servicesa |

172 |

17% |

89 |

25% |

Source: GAO analysis of data from the Small Business Administration (SBA) and selected agencies. | GAO‑25‑107942

Note: Selected agencies are those that issued both open and conventional topic awards through SBIR or STTR in fiscal year 2023. The SBIR and STTR Extension Act of 2022 referred to “non-traditional small business concerns” as including those owned by “women, minorities, and veterans.” Pub. L. No. 117-183, § 7(b)(3), 136 Stat. 2180, 2189. For the purposes of this report, we refer to businesses as being owned by individuals from socially and economically disadvantaged groups rather than minority-owned, consistent with SBA’s SBIR and STTR award data. Awards with missing data on nontraditional small businesses are not included in the denominators for percentage calculations. Percentages are rounded to the nearest 1 percent.

aThe difference between the percentage of open and conventional topic awards was statistically significant (p < .05).

Similar to our findings in prior years, DOD, DOE, and HHS varied in the percentage of awards they issued to specific types of nontraditional small businesses:

· Socially and economically disadvantaged. Only DOD had a statistically significant difference between open and conventional topic awards issued to small businesses owned by socially and economically disadvantaged individuals, issuing a higher percentage of open topic awards to these businesses. DOD and DOE issued a higher percentage of both open and conventional topic awards to small businesses owned by socially and economically disadvantaged individuals in FY 2023 compared to FY 2019 through FY 2022, while HHS issued a lower percentage of both open and conventional topic awards to these businesses.

· Women-owned. Only HHS had a statistically significant difference between open and conventional topic awards issued to women-owned small businesses, issuing a higher percentage of conventional topic awards to these businesses. DOE and HHS issued a higher percentage of both open and conventional topic awards to women-owned small businesses in FY 2023 compared to FY 2019 through FY 2022. DOD issued a lower percentage of conventional topic awards and about the same percentage of open topic awards to women-owned small businesses.

· Veteran-owned. DOD continued to issue the highest percentage of awards to veteran-owned small businesses and was the only agency with a statistically significant difference between open and conventional topic awards issued to veteran-owned small businesses. In FY 2023, DOD issued more open topic awards than conventional topic awards to veteran-owned small businesses, consistent with prior years. Compared to FY 2019 through FY 2022, DOD and HHS issued about the same percentage of awards to veteran-owned small businesses in FY 2023. DOE issued a higher percentage of open topic awards and about the same percentage of conventional topic awards to these small businesses.

See appendix IV for additional information on participation of businesses owned by socially and economically disadvantaged individuals, as well as women-owned and veteran-owned small businesses.

Technology Type

Agencies use SBIR and STTR awards to fund a range of technologies. For example, small business representatives we interviewed received awards to develop scientific and engineering solutions related to aircraft, batteries, drugs, artificial intelligence–based applications, and other technical areas. Of the agencies that issue both open and conventional topics, DOD and HHS reported no difference in the technology types funded by open or conventional topics, while our analysis of DOE data found some differences in the technology types funded. Specifically, in FY 2023, a higher percentage of DOE Phase I open topic awards were related to environmental technologies and manufacturing, while a higher percentage of Phase I conventional topic awards were related to advanced instrumentation and sensors.

Commercialization

Small businesses that received DOD, DOE, and HHS awards demonstrated varying success in progressing towards commercialization, as measured by the transition of Phase I awards (which businesses use to determine technical merit and feasibility) to Phase II (which businesses use to make technical progress, such as by developing prototypes).[36] Small businesses have a wide range of objectives aimed at successfully bringing a product or service to market. More specifically, the goals of small business representatives we interviewed included selling their technology to government or private customers, being acquired by a larger business, and working with another business to integrate their technology into an existing product. Further, commercialization goals may vary based on the typical customer of an agency’s SBIR or STTR awards. For example, a small business developing technology for an agency customer may have a commercialization goal to deliver the product to the agency, while a small business developing technology for nonagency customers may have a commercialization goal to increase sales to the public.

Data on small business progression to Phase III—known as the commercialization phase, in which a business completes development and sells products—are limited and not reliable enough to understand whether open or conventional topics correlate with better commercialization outcomes, as we previously found.[37] One reason the data are limited is that Phase III awards are difficult to track, since the SBIR and STTR programs do not fund Phase III awards. Instead, Phase III is funded by non-SBIR, non-STTR federal program sources (e.g., contracts) or nonfederal sources of capital (e.g., private investors).

There are several more reasons why tracking commercialization success after Phase III awards is challenging. First, small businesses have limited requirements to report commercialization metrics beyond the award term.[38] Second, while the Federal Procurement Data System includes a field for agencies to identify Phase III contracts resulting from Phase I or Phase II SBIR and STTR awards, the field is optional.[39] Further, the database does not include Phase I or Phase II awards funded with grants or cooperative agreements, which five agencies use to fund their SBIR or STTR awards. According to one organization that represents small business interests, many government sales resulting from SBIR and STTR awards are not identified as Phase III. This makes it challenging to accurately assess the commercialization of SBIR- and STTR-funded technologies even when these technologies receive Phase III awards from federal sources, which, according to SBA officials, are a small subset of all Phase III awards.

Additionally, looking only at the commercialization success of a business that received a SBIR or STTR award may not fully capture the program’s effects. A 2023 report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine identified several other benefits of SBIR and STTR awards. Specifically, awardees may apply knowledge gained from an award to their other work, principal investigators may leave the businesses and continue research in other businesses or industries, and scientific knowledge in publications and patents may spread to other businesses.[40] Further, according to a DOD study, SBIR and STTR awards had a positive multiplier effect, in which every dollar in economic activity directly attributable to the DOD SBIR and STTR program generated nearly two dollars in additional economic activity nationwide.[41]

Despite the challenges described above, agencies take a variety of approaches to measuring commercialization success, according to SBA officials. Some take a census approach and attempt to follow up with all businesses that have received awards and may ask about commercial success and which product lines were funded by SBIR or STTR. Others use commercial data sources, which can help track revenue or determine if businesses have merged or been acquired. For example, National Science Foundation (NSF) officials said that the agency tracks past awardees using commercial tools that monitor private business health and outcomes. The officials told us that this information helps the agency track the return on investment of its SBIR and STTR award portfolio.

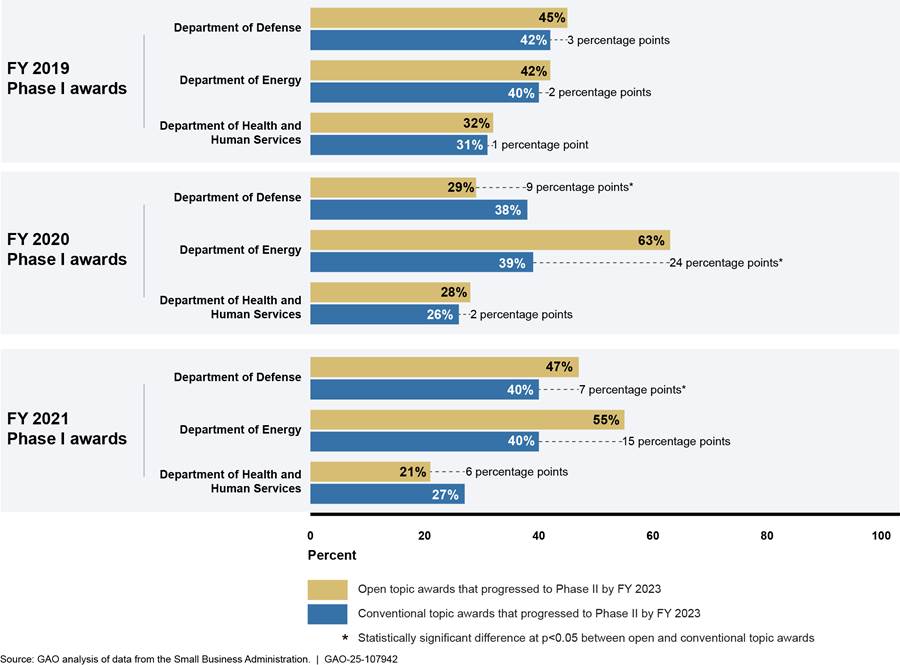

While we found differences in businesses’ progression from Phase I to Phase II awards across the three agencies that issued both open and conventional topic awards, we did not find that either open or conventional topic awards consistently progressed at a higher rate. To measure progress toward commercialization, we analyzed the extent to which Phase I awards issued by DOD, DOE, and HHS in FY 2019, 2020, and 2021 had progressed to Phase II by FY 2023.[42] In general, DOD and DOE Phase I awards had a higher rate of progression to Phase II than HHS awards (see fig. 8). After controlling for which year the Phase I award was issued, DOD and DOE had statistically significant differences in the progression of open and conventional topic awards, while HHS did not. DOD Phase I conventional topic awards were more likely to progress to Phase II, while DOE open topic awards were more likely to progress to Phase II. Given these differing results, it is difficult to conclusively determine whether agencies’ use of open or conventional topics affects commercialization.

Figure 8: Phase I to Phase II Progression of Selected Agencies’ Open and Conventional Topic Awards in the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) Programs, Fiscal Year (FY) 2019–2023

Note: Selected agencies are those that issued both open and conventional topic awards through SBIR or STTR in fiscal year 2023. Percentages are rounded to the nearest 1 percent. We used regression analysis to assess significance.

Agency officials also did not identify differences in commercialization between open and conventional topic awards. HHS officials said that they have not observed that technologies funded under open topics had differing commercialization potential compared to those funded under conventional topics. DOE officials said that they have not studied this, while DOD officials said that open topics have not been implemented long enough for the agency to accurately observe trends.

Selected Agencies Offer Varied Outreach and Assistance, Including on Open Topics

SBA and participating agencies provide a variety of outreach and assistance to raise awareness of, encourage participation in, and help small businesses apply to the SBIR and STTR programs (see table 4). Of the three agencies that release both open and conventional topics, DOD and HHS reported providing information about open topics in their outreach or assistance to small businesses.

Table 4: Examples of Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) Program Outreach and Assistance at Selected Agencies in Fiscal Year (FY) 2024

|

Agency |

Outreach |

Assistance |

|

Department of Defense (DOD) |

The Navy participated in 30 in-person and virtual outreach events. In-person events were held in 23 states and U.S. territories. |

The Army’s xTech Program offered four accelerator programs in FY 2024 that led to SBIR awards.a These programs included education, mentorship, and insights into working with DOD. They helped small businesses navigate the Army SBIR process and prepare successful proposals. |

|

Department of Energy (DOE) |

DOE conducted 27 webinars about SBIR and STTR topics and the application process, as well as an Ask Us Anything event with over 3,700 attendees. |

DOE’s Phase 0 Application Assistance Program targeted first-time applicants to DOE SBIR and STTR programs. It provided free services to small businesses accepted into the program to help them navigate the complexities of the SBIR and STTR proposal process. In FY 2024, the program served 225 small businesses. According to DOE officials in June 2025, the Phase 0 program was ended in 2025. |

|

Department of Health and Human Services |

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) hosted two webinars focused on providing information to new applicants. |

NIH’s Applicant Assistance Programs provided free coaching and proposal review services to small businesses accepted into the programs. In FY 2024, the programs served at least 255 small businesses, according to NIH officials. |

|

Small Business Administration (SBA) |

SBA hosted the America’s Seed Fund Road Tour, which stopped in 16 states and territories. Representatives from participating agencies attended each stop of the tour. |

SBA’s Federal and State Technology Partnership Program provided funding to organizations to carry out state or regional programs that increase the number of SBIR and STTR proposals. These programs may include services that improve proposal development and grants to applicants to bridge the gap between Phase I and Phase II awards. In FY 2024, the program awarded organizations in 49 states and U.S. territories, according to SBA. |

Source: GAO analysis of information from selected agencies. | GAO‑25‑107942

Note: Selected agencies are those that issued both open and conventional topic awards through SBIR or STTR in fiscal year 2023, as well as SBA, which oversees the SBIR and STTR programs.

aThe Army’s xTech Program hosts competitions that connect businesses with Army and DOD experts to build solutions for current problems.

Additionally, DOD, DOE, and HHS each reported targeting nontraditional small businesses, as well as small businesses new to the SBIR and STTR programs, in their outreach and assistance.[43] For example, in FY 2024, one DOD component’s outreach included events focused on women-owned and veteran-owned small businesses, which provided information about the SBIR and STTR program and upcoming opportunities. Another component helped new and nontraditional small businesses contact program managers and understand the complexities of government contracts. Officials said that their outreach efforts were the same regardless of topic type.[44]

A majority of the 22 small business representatives we interviewed participated in some form of outreach or assistance, including agency webinars, agency assistance programs, or SBA-funded state efforts. Many identified additional outreach or assistance that would be helpful, such as agencies providing examples of successful proposals, agencies offering more events where technical experts are present to answer questions, and more agencies implementing applicant assistance programs. Additionally, according to many small business representatives we interviewed, speaking with an agency point of contact before applying to a solicitation helps them understand whether their technology is a good fit. However, a few representatives said that they reached out to agency points of contact but did not get responses. Further, these points of contact may be available to small businesses only in a limited capacity, such as via email or a government website, according to a few representatives.

Agencies’ Topic Type Labels Do Not Consistently Reflect Nature of Solicitation, and Small Businesses Identified Tradeoffs with Both Topic Types

For this report, we reviewed 999 topics issued by the 11 participating agencies in FY 2023. Although conventional topics were generally less broad than open topics, topic type labels did not consistently indicate how broad or narrow an agency’s technology needs were in each solicitation.[45] Further, SBA has not defined open and conventional topics in guidance, even though it is required to report on their use. In addition, small business representatives that we interviewed identified tradeoffs with both topic types and emphasized that a solicitation’s alignment with a small business’s technology or mission was more important in their decision to apply than the topic type alone.

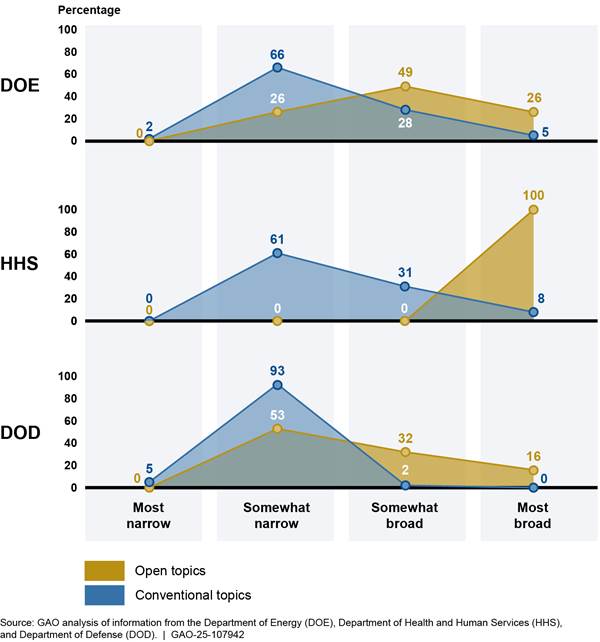

For Agencies That Used Both Topic Types, Labels Did Not Consistently Indicate the Specificity of Solicitations

Our analysis found that an agency’s topic type label was not always consistent with its intended purpose, namely that open topics would be broader and conventional topics narrower (see fig. 9). For example, we categorized more than one-half of DOE’s and HHS’s FY 2023 conventional topics as somewhat narrow or most narrow, while we categorized approximately one-third as somewhat broad or most broad. Specifically, we categorized 33 percent of DOE’s conventional topics and 39 percent of HHS’s conventional topics as somewhat broad or most broad. DOE’s open topics spanned a wider range, with nearly one-half categorized as somewhat broad and one-fourth as most broad. In contrast, we categorized all six of HHS’s open topics as most broad, reflecting an approach that allowed for wider interpretation of the solicitation and greater flexibility for applicants in defining the scope of their proposals. One DOE conventional topic we categorized as most broad sought any technologies that could help reduce carbon emission without identifying a specific problem or limiting the types of technologies that applicants could propose.

In our recent report, issued in 2024, we found that DOD’s FY 2023 open topics skewed narrow.[46] Specifically, we had categorized more than one-half of DOD’s open topics as somewhat narrow, while we also categorized almost all of its conventional topics as somewhat narrow.[47] In contrast, we found for this report that DOE’s and HHS’s open and conventional topics were both more frequently categorized as somewhat broad or most broad compared to DOD.

Figure 9: Distribution of DOE, HHS, and DOD Open and Conventional Topics in the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) Programs, Fiscal Year 2023

Note: Information includes topics released in solicitations for both SBIR and STTR. We categorized topics into the four groups based on the extent to which topics defined a (1) problem or need to be addressed, (2) technology area for the solution, and (3) technology stage. Technology stage refers to whether the topic called for integrating an existing technology, improving an existing technology, or developing a new technology. DOD specificity scores were derived from our prior work (GAO‑24‑107036) and were subsequently recalculated using an updated methodology.

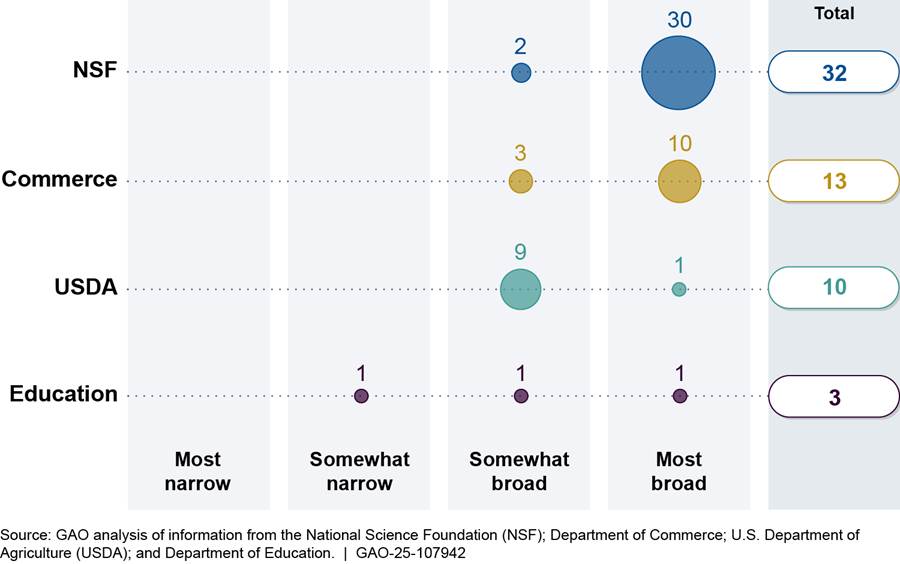

Of the Agencies That Release One Topic Type, Conventional Topics Had a Wider Range of Specificity than Open Topics

Our analysis shows that the four agencies that released only open topics almost always released topics that ranged from somewhat broad to most broad in FY 2023, consistent with the label’s intended purpose. Among these, NSF led in both volume, with the most open topics released, and broadness, with the most topics categorized as most broad. We categorized all open topics released by the following three agencies as somewhat broad or most broad:

· NSF released 32 open topics,

· the Department of Commerce released 13 open topics, and

· the Department of Agriculture (USDA) released 10 open topics.

In contrast, Education issued three open topics, one of which we categorized as somewhat narrow, highlighting an inconsistency in how open topics are labeled (see fig. 10). This topic focused on integrating existing education technology into instructional or learning settings, a targeted solution not typically seen in other open topics, which tend to allow for a wider range of approaches at different technology stages.

Figure 10: Analysis of Open Topics Across NSF, Commerce, USDA, and Education, by Number and Specificity, Fiscal Year 2023

Note: These agencies released only open topics in fiscal year 2023. Information includes topics released in solicitations for both Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR). We categorized topics into the four groups based on the extent to which topics defined a (1) problem or need to be addressed, (2) technology area for the solution, and (3) technology stage. Technology stage refers to whether the topic called for integrating an existing technology, improving an existing technology, or developing a new technology.

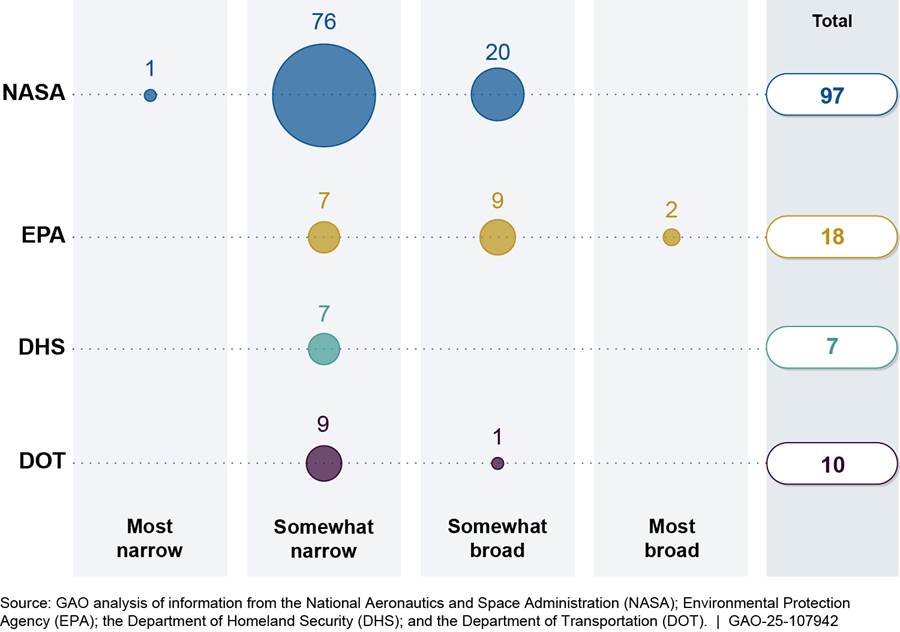

Agencies that released only conventional topics applied them with varying levels of specificity in FY 2023. For instance, we categorized 20 of NASA’s 97 conventional topics (21 percent) as somewhat broad (see fig. 11). One NASA topic we categorized as somewhat broad sought new machines that could operate on many terrains. While the topic allowed for a variety of solutions, it still had clear performance goals connected to NASA’s stated technology area for the topic. This type of language reflected a relatively wide scope, allowing for different technologies and approaches, which is more characteristic of open than conventional topics.

Although EPA released fewer topics than NASA, we categorized a larger share (11 of the 18 topics, or 61 percent) of its conventional topics as somewhat broad or most broad. For example, EPA issued a topic we categorized as most broad, which sought technologies to improve the U.S. recycling system. The topic covered multiple areas of the recycling system and allowed for any technology area without identifying any specific problems to address.

In contrast, we categorized almost all conventional topics from DHS and the Department of Transportation (DOT) as somewhat narrow. For instance, one DHS topic focused specifically on developing a digital software badge with defined requirements for first responders, limiting the scope to a specific problem to address and technology area. These variations show that even among agencies releasing only conventional topics, topic specificity varied. As a result, some conventional topics overlapped in broadness with open topics issued by other agencies, suggesting that topic type label did not consistently determine how broad or narrow a topic would be.

Figure 11: Assessment of Conventional Topics Across DHS, DOT, EPA, and NASA, by Number and Specificity, Fiscal Year 2023

Note: These agencies released only conventional topics in fiscal year 2023. Information includes topics released in solicitations for both Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR). We categorized topics into the four groups based on the extent to which topics defined a (1) problem or need to be addressed, (2) technology area for the solution, and (3) technology stage. Technology stage refers to whether the topic called for integrating an existing technology, improving an existing technology, or developing a new technology.

Small Businesses Identified Tradeoffs with Both Topic Types

Several small business representatives said they were unfamiliar with the difference between open and conventional topic types, but a majority provided perspectives on the tradeoffs between broadly and narrowly worded solicitations. For example, some representatives told us broadly worded solicitations allowed them to propose novel technologies or approaches they believed could support the agency’s mission, even if those technologies were not explicitly identified or anticipated by the agency. In contrast, many representatives told us narrowly worded solicitations provided more insight and clearer direction on agency needs. In addition, a few representatives said that they would be more likely to apply to a narrowly worded solicitation if the solicitation fit the business’s technology.

The small business representatives we interviewed also raised concerns related to flexibility, the quality of feedback, and alignment with agency needs (see table 5). For example, several representatives told us that open topics offered more flexibility in proposing innovative ideas. However, a few representatives said that some agencies provided better feedback on conventional topics. One representative said that reviewers of open-topic proposals were not familiar enough with a wide range of technologies to give helpful feedback, making it harder for the small business to improve future submissions.

Table 5. Selected Small Business Representatives’ Perspectives on Broadly and Narrowly Worded Solicitations

|

Theme |

Broadly worded solicitations |

Narrowly worded solicitations |

|

Flexibility and innovation |

Small businesses may benefit from greater flexibility to propose innovative or unexpected solutions |

Small businesses may face less flexibility when proposals must align with specific agency-defined needs |

|

Customer identification |

Small businesses without an identified customer or prior relationship with agencies may find it harder to succeed when agency expectations are less clear |

Small businesses may benefit when a solicitation indicates that there is already a potential customer as this can support efforts to sell the technology once developed |

|

Feedback from agencies |

Small businesses may receive limited or vague feedback from some agencies on proposals due to limited agency knowledge in proposal subject area |

Small businesses may receive more useful feedback from agencies on proposals due to more agency expertise in the subject area |

|

Timing and availability of solicitation |

Small businesses may submit proposals at the time of a broad solicitation, without waiting for a specific topic to be released, offering more opportunities to propose relevant technologies |

Small businesses typically depend on agencies to release narrowly defined topics that match their technology, which may limit when they can apply or compete for awards |

|

Alignment of small businesses’ proposals to agency needs |

Small businesses may struggle to align proposals with agency needs due to broad scope, increasing risk of proposal rejection |

Small businesses may benefit from clearer agency needs allowing for better alignment between their proposals and the solicitation |

|

Volume of proposals received |

Small businesses may face higher competition due to broad eligibility |

Small businesses may compete with fewer applicants due to narrower requirements |

Source: GAO analysis of interviews with small business representatives. | GAO‑25‑107942

Note: We interviewed 22 small business representatives from two randomly selected businesses that varied in size (from 1 to 150 employees) and experience from each of the 11 participating agencies.

SBA Has Not Defined Open and Conventional Topics Even Though It is Required to Report on Their Use

The SBIR and STTR Extension Act of 2022 requires SBA to collect and report data on open and conventional topics as part of its oversight of the SBIR and STTR programs. SBA is required to report annually to Congress on the programs, and the act added requirements to compare open and conventional topics. This includes reporting the total number, dollar amount, and average size of awards made by each participating agency, by phase, from open and conventional topics, as well as a comparison between open and conventional topics, by each participating agency that issues open topics, of the number of applications received and number of small businesses receiving awards.[48]

While the act did not explicitly distinguish how the specificity of open and conventional topics should differ, the language in Section 7 of the act requiring comparisons between the two topic types suggests that Congress intended open topics to differ from conventional topics. Further, the Small Business Act, as amended, requires SBA to issue policy directives that provide guidance to participating federal agencies for the general conduct of the SBIR and STTR programs, including providing for standardized SBIR and STTR solicitations.[49] SBA’s May 2023 policy directive requires participating agencies to follow SBA’s guidance provided therein.[50] Moreover, according to GAO’s guidance on assessing data reliability, data are considered reliable when they are sufficiently accurate and complete.[51]

However, when results were reviewed across participating agencies, we found differences in how they categorized open and conventional topics. For example, we characterized 21 percent of NASA’s conventional topics as somewhat broad, resembling the broadness of open topics released by agencies such as Commerce and Education. At the same time, other agencies, such as DOE, issued open topics that were narrowly focused on a single technology area. These variations indicate that agencies are applying their own interpretations when labeling topics.

This inconsistency is, in part, because SBA guidance has not distinguished how open and conventional topics should differ. Specifically, SBA guidance does not address the distinction, nor does it discuss considerations that should be made as agencies label topic types. Further, of the eight participating agencies that provided a response, officials did not reference SBA guidance in describing how they distinguish between open and conventional topics. In the absence of any SBA guidance, agencies relied primarily on the definitions we reported on in 2023 and as set forth at the start of this report, or their own interpretations. SBA officials said that they were not aware of agencies requesting that SBA provide definitions for open and conventional topics to report this information to SBA.

SBA collects and reports topic type data to inform Congress as part of its program oversight responsibilities. However, inconsistent categorization of topic types may impede Congress’s understanding and oversight of the SBIR and STTR programs. Without clear government-wide definitions, agencies may continue to interpret and label topic types differently, limiting the consistency and comparability of reported data across agencies. This, in turn, reduces the usefulness of SBA’s reported data across agencies and may limit SBA’s and Congress’s ability to assess program performance.

Conclusions

SBA’s reporting of agency information—including data on open and conventional topics—is key to its role in facilitating congressional oversight of the SBIR and STTR programs. While participating agencies used open topics to fund about 50 percent of all SBIR and STTR awards in FY 2023, they categorized their open and conventional topics inconsistently. Agencies’ inconsistent categorization of topic type limits the comparability of data across agencies and the usefulness of SBA’s data for assessing program performance and informing oversight. The absence of clear and documented government-wide definitions also hinders SBA’s ability to assess the outcomes associated with different topic types. Clarifying these definitions would improve the consistency of agency reporting and enhance Congress’s ability to effectively oversee the SBIR and STTR programs.

Recommendation for Executive Action

The Administrator of SBA should develop formal definitions for open and conventional topics and provide that guidance to participating agencies to encourage the consistent categorization of topic types in SBIR and STTR solicitations. (Recommendation 1)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to the Departments of Agriculture, Commerce, Defense, Education, Energy, Health and Human Services, Homeland Security, and Transportation; Environmental Protection Agency; National Aeronautics and Space Administration; National Science Foundation; and Small Business Administration for review and comment.

The director of SBA’s Office of Strategic Management and Enterprise Integrity provided an email stating that SBA concurs with our recommendation without comment. The remaining 11 agencies did not have any comments on the report or provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees; the Secretaries of Agriculture, Commerce, Defense, Education, Energy, Health and Human Services, Homeland Security, and Transportation; the Administrators of the SBA, Environmental Protection Agency; the Acting Administrator of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration; the Chief of Staff of the National Science Foundation; and other interested parties. In addition, this report will be available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at BenedictH@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix V.

Hilary M. Benedict

Acting Director, Science, Technology Assessment, and Analytics

List of Committees

The Honorable Roger F. Wicker

Chairman

The Honorable Jack Reed

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

United States Senate

The Honorable Joni Ernst

Chair

The Honorable Edward J. Markey

Ranking Member

Committee on Small Business and Entrepreneurship

United States Senate

The Honorable Mike Rogers

Chairman

The Honorable Adam Smith

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

House of Representatives

The Honorable Brian Babin

Chairman

The Honorable Zoe Lofgren

Ranking Member

Committee on Science, Space, and Technology

House of Representatives

The Honorable Roger Williams

Chairman

The Honorable Nydia M. Velázquez

Ranking Member

Committee on Small Business

House of Representatives

The SBIR and STTR Extension Act of 2022 includes a provision requiring us to issue a series of reports comparing several aspects of open and conventional topics of federal agencies participating in the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) programs.[52]

This report examines:

1. the number and dollar amount of SBIR and STTR awards from open topics that participating agencies issued in fiscal year (FY) 2023;

2. how participating agencies’ FY 2023 open and conventional topic awards compare—in terms of competition, participation of nontraditional small businesses, first-time applicants and first-time awardees, the amount of time to notify applicants of outcomes and issue awards, and commercialization of technologies—and factors that account for any differences; and

3. how agencies’ FY 2023 open and conventional topics compare in terms of specificity.

The scope of work includes the Small Business Administration (SBA) and the 11 participating agencies, including 29 components within the 11 agencies (see fig. 2 above). We identified possible components through our past work. We then asked agency officials to identify which of those components, along with any others, developed their own topics in FY 2023.

To address our objectives, we (1) collected and analyzed data to summarize and compare open and conventional topics awards from FY 2019 through FY 2023; (2) summarized and compared participating agency open and conventional topics from FY 2023; (3) interviewed representatives from 22 randomly selected small businesses that received awards in FY 2023; (4) interviewed agency officials and reviewed related documentation; and (5) interviewed representatives from one organization that represents small businesses (the Small Business Technology Council) to obtain additional information about small businesses’ experience with open and conventional topics, among other issues.

Summary and Comparison of Open and Conventional Topic Awards

To summarize and compare open topic and conventional topic awards from FY 2019 through FY 2023, we obtained data from multiple sources, assessed reliability, cleaned the data as needed, merged the data into a single data set, compared summary data on awardee characteristics, award outcomes, and the amount of time to notify applicants of outcomes and issue awards, and performed multivariate logistic regression analyses to assess whether differences were statistically significant.

SBA Award Data and Registry Data