BANK CAPITAL REFORMS

U.S. Agencies’ Participation in the Development of the International Basel Committee Standards

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Michael Clements at clementsm@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107995, a report to congressional requesters

U.S. Agencies’ Participation in the Development of the International Basel Committee Standards

Why GAO Did This Study

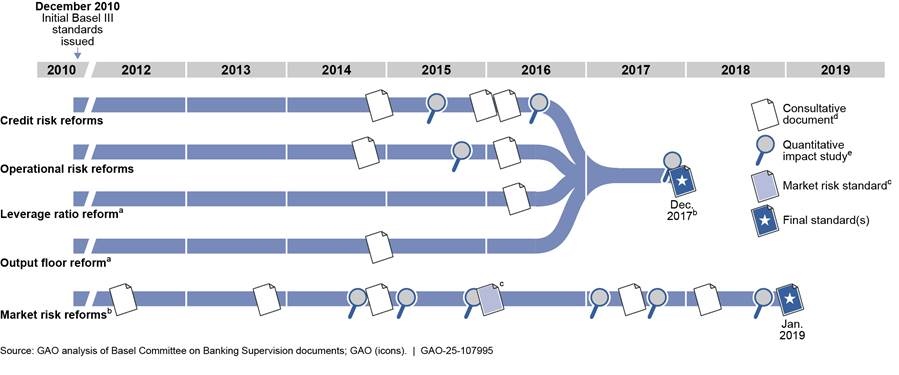

The Basel Committee released initial Basel III standards in 2010, followed by additional reforms that resulted in final Basel III standards in 2017 and 2019. These updated standards, which have not yet been implemented in the U.S., revised methods for estimating a bank’s risks, which affect its regulatory capital requirements.

GAO was asked to review U.S members’ actions during the final Basel III negotiations. This report examines (1) how the Basel Committee organized the work to develop the standards, (2) information and analyses U.S. members considered to inform their positions, and (3) U.S. members’ priorities for reform and actions taken to further those priorities. This is the public version of a sensitive report GAO issued in December 2024. Information on U.S. members’ actions during the development of the standards and their positions on reforms has been omitted.

GAO analyzed U.S. members’ internal sensitive documents related to the development of the standards. These included internal briefing notes, talking points, analyses, and other documents prepared for the negotiations during 2011–2019. GAO also analyzed Basel Committee consultative documents, quantitative impact studies, other publicly released documents, and the final Basel III standards. GAO interviewed officials from the four U.S. members responsible for the final Basel III negotiations and Basel Committee Secretariat staff (who support the work of the Committee and its component groups).

What GAO Found

Capital plays a critical role in ensuring bank safety and soundness. The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, an international body of bank supervisors, sets nonbinding minimum regulatory capital standards for large banks. The committee relies on its members to implement the standards in their jurisdictions. The U.S. members of the Basel Committee are the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and Office of the Comptroller of the Currency.

Standard-development process. The Basel Committee process for developing the standards involved multiple rounds of analyses, discussion, and review. Each final standard underwent at least one round of public comments and quantitative studies assessed potential impacts on banks’ regulatory capital. Decisions were made by consensus, with groups negotiating and agreeing on the scope of work, alternatives to analyze, actions to take or not take, and standards to propose and finalize. Staff from all U.S. members participated in these groups. GAO found collaboration among U.S. members throughout this process generally reflected best practices for interagency collaboration (such as leveraging information and including relevant participants).

External comments and impact analyses. U.S. members informed their positions by reviewing public comments on proposals, meeting with industry representatives, contributing to and using quantitative impact studies, and conducting their own analyses. These activities helped provide insight into the potential impacts of proposed reforms and identify alternative approaches. GAO found that the information U.S. members collected and analyses they conducted generally reflected key elements for regulatory analysis (such as consideration of alternatives and evaluation of benefits and costs).

U.S. members’ negotiating priorities. U.S. members had two overarching reform priorities for the final Basel III standards. One was to better align certain regulatory standards for non-U.S. banks with their parallel U.S. requirements to promote a more level playing field. U.S. members also shared the Committee’s priority to address weaknesses in the Basel framework—they sought to improve and balance the simplicity, comparability, and risk sensitivity of bank capital standards. For example, previous standards allowed banks more leeway in the way they modeled the risks of their assets (to help determine how much regulatory capital to hold to offset the risks). The Committee, including U.S. members, prioritized reforms that constrained banks’ use of internal models to help increase the comparability of risk-weighted assets across banks. GAO’s analysis of U.S. documents showed that U.S. members participated actively in the working groups that developed the standards to further their reform priorities.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

FDIC |

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation |

|

Federal Reserve |

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and Federal Reserve Bank of New York |

|

FRB |

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System |

|

FRBNY |

Federal Reserve Bank of New York |

|

GHOS |

Group of Central Bank Governors and Heads of Supervision |

|

G-SIB |

global systemically important bank |

|

OCC |

Office of the Comptroller of the Currency |

|

PDG |

Policy Development Group |

|

RWA |

risk-weighted asset |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

March 26, 2025

The Honorable French Hill

Chairman

Committee on Financial Services

House of Representatives

The Honorable Andy Barr

Chairman

Subcommittee on Financial Institutions

Committee on Financial Services

House of Representatives

Bank capital plays a critical role in ensuring the safety and soundness of U.S. banks. It serves as a buffer to absorb losses, protect depositors, and promote confidence in the banking system. Capital provides reassurances to depositors, creditors, and counterparties that unanticipated losses or decreased earnings will not impair banks’ ability to safeguard savings, repay creditors, or meet other obligations. As demonstrated during the 2007–2009 financial crisis, banks with insufficient capital may pose a threat to financial stability, particularly in times of economic turmoil. However, increasing capital requirements could raise banks’ funding costs, because capital is a more expensive source of funding than debt. These higher funding costs could then be passed onto households and businesses.

To promote global financial stability, U.S. and banking regulators worldwide negotiate and develop minimum capital standards for banks through the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. The Basel Committee was established in 1974 by the central bank governors of the Group of Ten and is headquartered at the Bank for International Settlements in Basel, Switzerland.[1] The U.S. members on the Basel Committee include three federal banking regulators—the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), and Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC).[2] The fourth U.S. member is the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, which is involved in the Board’s international engagement due to its role in the financial system and expertise in international financial matters.[3] Throughout this report (unless otherwise noted), we use Federal Reserve to collectively refer to the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Basel standards are nonbinding, but members are expected to apply generally consistent requirements to internationally active banks in their respective jurisdictions. Historically, U.S. members have issued regulations that generally align domestic capital requirements with Basel standards, according to the U.S. members.[4] In 2010, the Basel Committee agreed on a framework aimed at strengthening capital and liquidity requirements, known as Basel III.[5] In 2017 and 2019, the Committee issued additional changes, aimed at improving the comparability of banks’ regulatory capital requirements. We refer to this set of changes as the final Basel III standards.[6]

U.S. federal banking regulators proposed regulations to implement many of the final Basel III standards in September 2023.[7] As of March 3, 2025, the rulemaking had not been finalized. Banking regulators estimated that the proposed regulations would increase capital requirements for most U.S. banking organizations with at least $100 billion in assets.[8]

You asked us to review U.S. federal banking regulators’ participation in the development of the final Basel III standards. Specifically, this report examines (1) how the Basel Committee organized the work to develop the final Basel III standards, including the participation of U.S. members; (2) the information U.S. members gathered and the analysis they performed to inform their positions; and (3) U.S. members’ priorities for reform and actions taken to further those priorities. In addition, the report describes the development—including the role of U.S. members—of selected components of the final standards and selected components of a proposed standard that were not included in the final standards (see app. I).

This report is a public version of a sensitive report we issued on December 12, 2024.[9] The sensitive report’s second objective, third objective, appendix I, and appendix III included some statements on U.S. agencies’ actions or positions on reforms that the agencies determined were controlled unclassified information.[10] Consequently, we omitted the following types of statements from this report:

· The second objective omitted statements related to U.S. members’ specific actions or positions on reforms in response to external input or analyses during the development of the standards.

· The third objective omitted statements describing U.S. members’ positions on specific reforms and actions taken by U.S. members to further their reform priorities during the development of the standards.[11]

· Appendix I omitted certain statements on U.S. members’ role in the development of selected components of proposed or final standards.

· Appendix III omitted statements that described U.S. members’ actions or positions on reforms related to leading practices for development of high-quality and evidence-based analysis.

Although the information provided in this report is more limited, it generally addresses the same objectives and uses the same methodology as the sensitive report.

To address the objectives, we analyzed U.S. member and Basel Committee documentation of the negotiation of the final Basel III standards from January 2011 (directly after the issuance of the initial Basel III standards) to January 2019 (when the final standards were issued). Our analysis encompassed the standards for credit, market, and operational risk; the leverage ratio; and the output floor (discussed later in this report).[12]

To understand U.S. member participation in the Basel Committee, the information and analyses used to inform their positions, and how U.S. members’ actions helped further their reform priorities, we analyzed nearly 600 internal sensitive agency documents from U.S. members (Federal Reserve, FDIC, and OCC) dated from January 2011 to January 2019. These documents included briefing notes and talking points prepared for agency leadership and Basel Committee representatives, as well as emails and presentations about the negotiations. We examined information on U.S. members’ negotiating priorities, positions, and actions for each standard. We also examined how these positions evolved over time and the information and analyses used to inform them.

Furthermore, we collected and analyzed information on interagency communication during the negotiations and compared our findings against our leading practices for interagency collaboration.[13]

To address these objectives, we also analyzed documents publicly available on the Basel Committee website. These documents included consultative documents, quantitative impact studies (of potential effects on banks’ capital), discussion papers, and press releases. We identified these documents by searching the Basel Committee’s website for materials related to the final Basel III standards and dated from January 2011 to January 2019.[14] We focused on the types of information the Basel Committee considered in developing the standards and when information on the process was publicly released. We also analyzed the Basel framework and its full set of standards (including the final Basel III standards issued in 2017 and 2019).[15] Nonpublic Basel Committee documents were not available to us. Basel Committee discussions and related information are governed by confidentiality expectations, according to U.S. officials and the Basel Committee Secretariat.[16]

In addition, we compiled and analyzed information on public comments received by the Basel Committee in response to the final Basel III consultative documents published from 2011 to January 2019.[17] For each comment, we identified the author and jurisdiction of origin. We calculated the number of comments received on each consultative document and the share of comments received from U.S.-based organizations.[18]

To assess U.S. members’ actions to develop the final Basel III reforms, we compared the results of our analysis of internal U.S. member documents and the Basel Committee’s publicly available documents against the Office of Management and Budget’s key elements of regulatory analysis.[19] These elements (such as examining alternative approaches and conducting cost-benefit analyses) guide certain U.S. regulatory agencies to develop high-quality and evidence-based regulatory analysis.

For our objectives, we also interviewed officials of the Federal Reserve, FDIC, and OCC. Discussion topics included the organization and function of the Basel Committee, negotiating process, U.S. members’ internal procedures, goals for the reforms, analyses conducted, and interagency coordination. These officials included current and past U.S. member representatives to various Basel Committee groups.[20] In addition, we interviewed Basel Secretariat staff and the current Basel Committee Secretary General about the roles of key Basel Committee groups, the process and timing for developing the final Basel III standards, and the types of information that informed the process.

The performance audit upon which this report is based was conducted from January 2024 to December 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We subsequently worked with the agencies from December 2024 to March 2025 to prepare this public version of the original sensitive report. This public version also was prepared in accordance with those standards.

Background

U.S. Banking Regulators

The U.S. banking regulators that are Basel Committee members—Federal Reserve, FDIC, and OCC—supervise banking organizations for their safety and soundness. Their responsibilities include issuing regulations to establish capital, liquidity, and other requirements for the institutions they supervise, with the goal of promoting the health of the banking system. See table 1 for information on the types of banking organizations these regulators supervise.

Table 1: U.S. Members of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision and the Banking Organizations They Supervise

|

Member |

Supervised entities |

|

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System |

Bank holding companies, domestic financial holding companies, state-chartered banks that are members of the Federal Reserve System, savings and loan holding companies, the U.S. operations of foreign banking organizations, and other entities. |

|

Federal Reserve Bank of New York |

Banking organizations subject to supervision by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and located in the Second Federal Reserve District (New York State, northern New Jersey, southwestern Connecticut, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands). |

|

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation |

Federally insured state-chartered banks and savings associations that are not members of the Federal Reserve System. |

|

Office of the Comptroller |

National banks, federally chartered savings associations, and federal branches and agencies of foreign banks. |

Source: GAO. | GAO‑25‑107995

According to the banking regulators, they have authority to take actions that are reasonable and appropriate to effectuate their statutory responsibilities, including participating in the Basel Committee and other international organizations. The representational authorities derive from statutes.[21]

U.S. Regulatory Capital Requirements

The U.S. regulatory capital framework, as prescribed in regulation, includes several minimum ratios of regulatory capital to assets that banking organizations (referred to as banks, unless otherwise noted) must meet or exceed. A banks’ assets—such as cash, loans made to individuals or institutions, and securities—can pose various risks, including credit, market, and credit valuation adjustment risks.[22] Banks also face operational risk from events including processing errors, internal and external fraud, legal claims, and business disruptions. Certain ratios account for these risks (risk-weighted assets) and help regulators determine whether banks hold sufficient capital in relation to those risks.

U.S. regulations require that most U.S. banks calculate their risk-weighted assets using standardized approaches, which assign different risk weights to various asset types. The risk weights reflect regulatory judgment about the riskiness of an asset type or exposure.

U.S. regulations also require internationally active U.S. banking organizations (internationally active banks)—to use advanced or internal model approaches to calculate risk-weighted assets.[23] These more technical, complex procedures set in regulation aim to be more risk-sensitive than standardized approaches.[24] Internationally active banks must meet or exceed the minimum regulatory capital ratios calculated under both the standardized and advanced approaches.

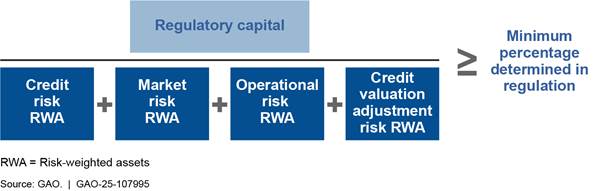

Internationally active banks compute risk-weighted assets for credit, market, operational, and credit valuation adjustment risks.[25] Generally, the on-balance sheet amount of each asset is multiplied by its assigned risk weight.[26] The adjusted amounts for all assets in a risk category are then summed. Risk-weighted assets for all categories then are added to compute the total risk-weighted assets.

The sum of the calculations for each of the four risk categories constitutes total risk-weighted assets for an internationally active bank. In turn, the total risk-weighted assets become the denominator of the banks’ risk-based capital ratios (see fig. 1).[27]

Note: U.S. banking organizations, including internationally active banks, are subject to multiple minimum risk-based capital ratios. The ratios differ in the type of regulatory capital required (numerator). All risk-based ratios share the same calculation of risk-weighted assets, but not all banks must calculate risk-weighted assets in all categories of risk. Credit risk is the potential for loss resulting from the failure of a borrower or counterparty to perform on an obligation. Market risk is the potential for loss resulting from movements in market prices, including interest rates, commodity prices, stock prices, and foreign exchange rates. Operational risk is the risk of loss resulting from inadequate or failed internal processes, people, and systems or from external events. Credit valuation adjustment risk is the potential for loss from the deterioration in the creditworthiness of a bank’s counterparty to a derivative transaction.

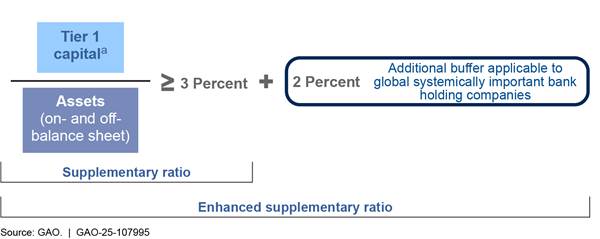

All banks must comply with an additional minimum ratio, known as the leverage ratio, which is based on total assets irrespective of their risk. The leverage ratio is often described as a “backstop” to risk-weighted regulatory capital and is intended to help prevent excessive leverage (borrowing of funding). Additionally, U.S. internationally active banks and certain other banks are subject to the supplementary leverage ratio, which takes into account additional exposures.[28] Global systemically important bank holding companies are also subject to an enhanced supplementary leverage ratio, which adds an additional buffer to the supplementary leverage ratio (see fig. 2).[29]

Figure 2: Supplementary Leverage Ratio Requirements for Internationally Active Bank Holding Companies

Note: The supplementary leverage ratio applies to all internationally active banks (advanced or internal model approaches banking organizations) and Category III banking organizations (those with $250 billion or more in assets or $75 billion or more in nonbank assets, weighted short-term wholesale funding, or off-balance sheet exposures). Global systemically important bank holding companies must meet an enhanced supplementary leverage ratio of 5 percent (set at 2 percentage points higher than the supplementary leverage ratio of 3 percent). Although not shown here, depository institution subsidiaries of global systemically important bank holding companies or bank holding companies with consolidated assets over $700 billion or more than $10 trillion in assets under custody must meet an enhanced supplementary leverage ratio of 6 percent (3 percent on top of the 3 percent supplementary leverage ratio) to be deemed well-capitalized.

aTier 1 capital is a type of regulatory capital defined as the sum of common equity tier 1 capital and additional tier 1 capital. 12 C.F.R. 3.2; 12 C.F.R. 217.2; 12 C.F.R. 324.2. Common equity tier 1 capital generally consists of retained earnings (profits a bank earned but has not distributed to shareholders in the form of dividends or other distributions), accumulated other comprehensive income, and qualifying common stock, with deductions for items such as goodwill and deferred tax assets. Additional tier 1 capital generally consists of qualifying noncumulative perpetual preferred stock. See 12 C.F.R. 3.20(b), (c); 12 C.F.R. 3.22; 12 C.F.R. 217.20(b), (c); 12 C.F.R. 217.22; 12 C.F.R. 324.20(b), (c); 12 C.F.R. 324.22.

Basel Committee and Final Basel III Standards

As of March 13, 2025, the Basel Committee comprised 45 members from 28 jurisdictions, consisting of central banks and authorities with formal responsibility for the supervision of banks. The Basel Committee sets minimum regulatory standards and supervisory guidelines to strengthen the regulation, supervision, and practices of banks worldwide with the purpose of enhancing financial stability. The standards have no legal force but are developed and issued by members with the expectation that individual jurisdictions will implement them.

The development of the final Basel III standards generally began after the initial Basel III standards were issued in December 2010 and concluded in January 2019 (see fig. 3). To inform the development of these standards, the Basel Committee solicited external comments on proposed standards through public consultative documents. It also conducted quantitative impact studies to help estimate the effect of proposed reforms on banks’ capital.

Notes: Credit risk is the potential for loss resulting from the failure of a borrower or counterparty to perform on an obligation. Operational risk is the risk of loss resulting from inadequate or failed internal processes, people, and systems or from external events. Market risk is the potential for loss resulting from movements in market prices, including interest rates, commodity prices, stock prices, and foreign exchange rates.

aA leverage ratio sets an overall minimum capital standard based on a bank’s assets (irrespective of their risk). Generally, an output floor sets an overall minimum capital standard based on a bank’s risk-weighted assets.

bThe market risk reforms also revised the capital requirement for credit valuation adjustment risk—a form of market risk that captures the potential for loss from the deterioration in the creditworthiness of a bank’s counterparty to a derivative transaction. The 2017 standards also included a revised standard for calculating credit valuation adjustment risk, but we do not discuss that standard separately in this report.

cIn January 2016, the Basel Committee finalized a standard for market risk. However, the Committee continued work and issued a revised standard in January 2019.

dThe Basel Committee generally issues consultative documents to communicate and request public comments on proposed standards.

eThe Basel Committee generally conducts quantitative impact studies to assess the impact of proposed standards on selected banks.

The Basel Committee communicated the need for further reforms to the initial Basel III standards in a 2013 report.[30] The report noted that use of bank internal models promoted risk sensitivity in the Basel framework but also led to complexity and reduced comparability among large banks’ calculations of risk-weighted assets.[31] The Committee corroborated these findings through its own empirical analyses.[32] Furthermore, the Committee stated the need to address such shortcomings to foster the credibility of the framework.

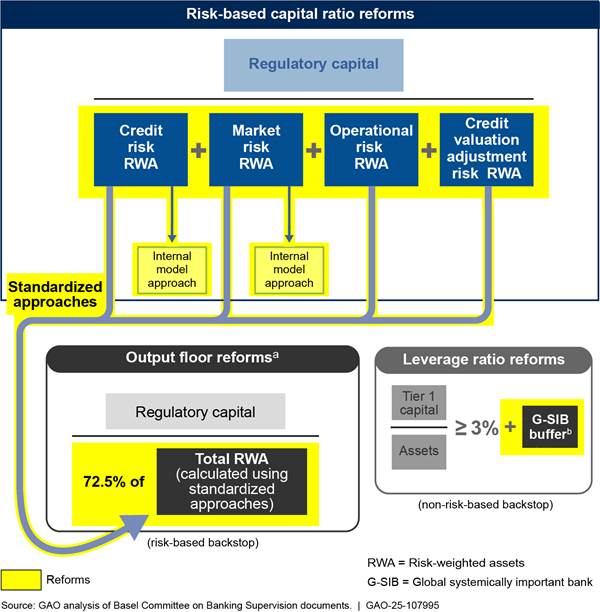

As a result, the 2017 final Basel standards sought to improve and balance the simplicity, comparability, and risk sensitivity of capital standards for internationally active banks. These reforms included changes to banks’ methods for measuring credit and operational risk-weighted assets. They also introduced a new leverage ratio buffer for the largest banks and replaced an existing capital floor (output floor).[33]

Specifically, the changes made to the standards aimed to achieve several broad priorities for the 2017 reforms:

· Enhance the robustness and risk sensitivity of standardized approaches for credit and operational risk.

· Constrain use of internal model approaches by limiting inputs used for calculating credit risk under this approach and removing the use of this approach in the calculation of operational risk.[34]

· Introduce a leverage ratio buffer for global systemically important banks (to add a capital cushion to their existing Basel leverage ratio standard and to serve as a backstop to the risk-based requirements).

· Replace the existing Basel output floor with a more robust risk-sensitive output floor that sets an aggregate minimum capital floor for banks based on their risk-weighted asset calculations under the revised standardized approaches.[35] Specifically, calculations of risk-weighted assets generated by a bank’s internal models cannot, in aggregate, fall below 72.5 percent of the risk-weighted assets computed using standardized approaches.

The Basel Committee published its revised standards for minimum capital requirements for market risk in 2016 and updated them in 2019.[36] The global financial crisis showed that the framework’s capital requirements for trading activities were insufficient to absorb losses. The Committee made revisions to the market risk framework in 2009, but it recognized that these changes did not fully address the framework’s shortcomings. As a result, the Committee initiated a fundamental review of the trading book to address weaknesses in risk measurement under both internal model and standardized approaches.[37]

The revised standards intended to achieve the following broad priorities for the 2019 market risk reforms:

· Revisions to the internal model approach to better address risks observed during the global financial crisis and reinforce supervisory approval processes for the use of internal models.

· A new, more risk-sensitive standardized approach designed and calibrated to serve as a credible fallback to the internal model approach.

· Stricter criteria for the assignment of financial instruments to the trading book.

· A simplified standardized approach for use by banks that have small or noncomplex trading portfolios.

Figure 4 provides a high-level summary of the final Basel III reforms, which can be categorized into three main areas: (1) reforms to the denominators of the risk-based capital ratios, including the approaches for calculating credit, market, and operational risk-weighted assets; (2) the introduction of a new leverage ratio buffer for global systemically important banks; and (3) a revised output floor based on calculations of risk-weighted assets using the Basel III standardized approaches.

Notes: The framework includes multiple capital ratios that may differ in the type of regulatory capital required (numerator). For example, tier 1 capital is a type of regulatory capital that includes retained earnings (profits a bank earned but has not paid out to shareholders in the form of dividends or other distributions), accumulated other comprehensive income, and qualifying common stock or shares.

Credit risk is the potential for loss resulting from the failure of a borrower or counterparty to perform on an obligation. Market risk is the potential for loss resulting from movements in market prices, including interest rates, commodity prices, stock prices, and foreign exchange rates. Operational risk is the risk of loss resulting from inadequate or failed internal processes, people, and systems or from external events. Credit valuation adjustment risk is a form of market risk that captures the potential for loss from the deterioration in the creditworthiness of a bank’s counterparty to a derivative transaction. We do not discuss the credit valuation adjustment risk standard separately in this report.

aPer the revised output floor standard, calculations of risk-weighted assets generated by a bank’s internal models cannot, in aggregate, fall below 72.5 percent of the risk-weighted assets computed using standardized approaches.

bAccording to the Basel Committee, global systemically important banks are banking organizations whose distress or disorderly failure would cause significant disruption to the wider financial system and economy due to their size, complexity, and interconnectedness.

Basel Members Worked in Groups to Develop Standards Using an Iterative, Consensus-Driven Process

Members’ Senior Officials Oversaw the Basel Committee Groups That Developed the Standards

To develop the final Basel III standards, the Basel Committee relied on key groups at various levels within the Committee structure. In addition, the Group of Central Bank Governors and Heads of Supervision (GHOS), which consists of the heads of supervision and central bank governors from the 28 member jurisdictions, oversaw the Committee’s efforts, including by providing guidance and endorsing the final standards.[38]

The Basel Secretariat, which consists of permanent and temporary staff from member jurisdictions, provided administrative support for the Committee’s efforts. The Basel Secretariat supports Basel Committee groups by ensuring timely information flow to all members, facilitating coordination across groups, and maintaining Basel Committee records. The Secretariat is led by a Secretary General who is appointed by the Chair of the Parent Basel Committee.[39]

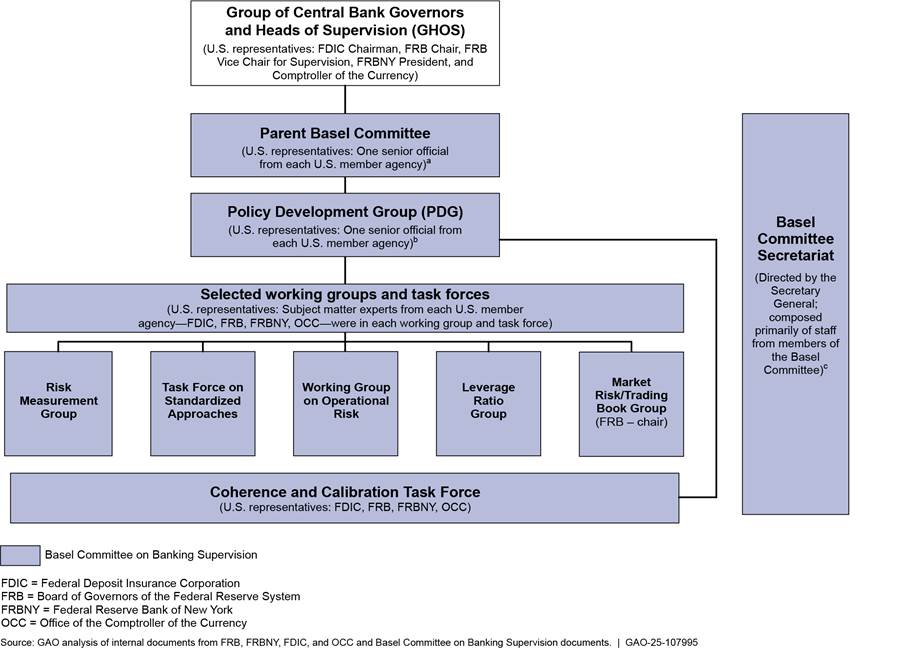

As shown in figure 5, the key Basel Committee groups responsible for developing the final Basel III standards are as follows:

· The Parent Basel Committee established the strategic priorities for the final Basel III reforms and reported to GHOS. Based on our analysis of U.S. member documents, this group, which is the highest decision-making body in the Basel Committee, developed reform priorities to guide the other groups responsible for developing the standards and monitored their progress. It was also responsible for finalizing the standards and transmitting them to GHOS for consideration and endorsement. Four senior officials from U.S. members (one from each U.S. Basel Committee member) served on the Parent Basel Committee.[40]

· The Policy Development Group (PDG) managed the development of the final Basel III standards in accordance with the Parent Basel Committee’s strategic priorities and reported to the Parent Basel Committee, according to U.S. officials. According to our review of internal agency documents and U.S. and Basel Secretariat officials, PDG delegated and managed the development work for each reform. The Basel Secretary General served as PDG chair during the development of the final Basel III standards. Four senior officials from U.S. members (one from each U.S. Basel Committee member) participated in the PDG.[41]

· Working groups and task forces developed the technical aspects of the standards under PDG guidance. Task forces generally were temporary and focused on narrow topics within a broader reform area or a specific issue affecting multiple reforms. These groups generally were staffed with subject matter experts—such as policy analysts, technical experts, and financial analysts specializing in capital risk—from the Basel members, including U.S. members. Our analysis of U.S. agency documents found that officials from each U.S. member participated in the major working groups and task forces primarily tasked with completing the work for each reform. In one case, an official from a U.S. member led the group.

Figure 5: Basel Committee on Banking Supervision and U.S. Member Participation During the Development of Final Basel III Standards

aSenior officials who participated in the Parent Basel Committee included directors, deputies, or heads of departments or equivalent positions from each member agency.

bSenior officials who participated in the PDG included deputy directors, associate directors, senior advisors, and heads of departments.

cPer the Basel Committee’s charter, staff from jurisdictions that are members of the Basel Committee, including from the United States, worked at the Basel Committee Secretariat on a temporary basis.

Groups met regularly to work on the final Basel III standards, according to our analysis of U.S. agency documents and interviews with U.S. officials. The PDG and Parent Basel Committee each met at least once a quarter, typically in successive months. Working groups and task force members also met at least quarterly and maintained regular contact between meetings to develop the proposals and prepare materials for consideration by the PDG and Parent Basel Committee.

U.S. Member Participation

U.S. members participated actively at all levels of the Basel Committee structure. According to U.S. officials, each U.S. member identified officials, including subject matter experts, to work on the final Basel III standards. This work was part of officials’ regular duties. Representatives to GHOS and senior officials representing U.S. members in the Parent Basel Committee helped determine negotiating priorities, according to our analysis of U.S. agency documents.

Subject matter experts from each U.S. member completed the technical work necessary to develop reform proposals in line with those priorities. They did so primarily by participating in PDG, working groups, and task forces that completed the technical work on the Basel standards. Generally, these experts briefed their agencies’ representatives to the Parent Basel Committee and PDG about the key issues and considerations for developing negotiating positions ahead of quarterly meetings. We found that U.S. officials in working groups frequently communicated about ongoing work with PDG and Parent Basel Committee representatives and sought review and clarity about how to address challenges as they arose.

U.S. officials told us that U.S. members’ GHOS representatives played a key role in directing negotiations for the final Basel III standards. Our analysis of U.S. member documents found that agency officials regularly shared information about the progress of the final Basel III standard negotiations with GHOS representatives. Officials working on the negotiations also consulted with their respective GHOS representatives on material issues, according to U.S. officials. These included proposals expected to have a sizeable impact on U.S. banks or the financial system or those expected to be controversial.

U.S. Member Collaboration

We found that U.S. members developed shared reform priorities and worked together to further those priorities during the final Basel III standard negotiations. PDG and Parent Basel Committee representatives from each agency met multiple times a year throughout the development period to share updates on ongoing work and align negotiating strategies. In addition, agencies coordinated efforts to analyze bank data and shared their findings. Furthermore, we identified cases in which U.S. members jointly advocated for specific positions, including by sending a joint letter to the Parent Basel Committee or PDG. According to U.S. officials, working group staff also maintained frequent contact throughout the development period.

We determined that the actions taken by U.S. members during the development of the final Basel III reforms generally reflected leading practices for interagency collaboration that GAO identified in prior work.[42] For example, U.S. agency documents indicated that U.S. members jointly identified and promoted U.S. priorities, shared and leveraged information among member agencies, and included relevant senior and expert participants in interagency communications.

Basel Groups Used an Iterative Process to Develop Standards and Reach Consensus

The process to develop the final Basel III standards was iterative, involving multiple rounds of analyses, discussion, and review. According to our analysis of U.S. agency documents and interviews with U.S. officials and the Basel Secretariat, the process for developing the final Basel III reforms followed a three-stage approach:

1. The Parent Basel Committee established priorities and the PDG established working groups.

2. Groups considered jurisdictions’ positions, conducted quantitative analyses, and received external input to develop reform proposals.

3. The Parent Basel Committee finalized the 2017 final Basel III standards and the 2019 final Basel III standards with GHOS endorsement. This endorsement was the final step needed for publication subject to revisions that GHOS might request.

Establishment of work plans and working groups. The Parent Basel Committee developed high-level work plans that specified priorities for reform. According to U.S. officials, these work plans set parameters for specific reforms, generally grounded in the broad priorities of the final Basel III reform effort.[43] For example, an initial work plan on credit risk reform directed members to create standards that constrained the use of internal models. According to U.S. agency documents, the Parent Basel Committee typically revised work plans annually. These work plans were sometimes developed with input from PDG and working groups, according to U.S. officials. As previously described, the PDG established working groups and task forces to help develop the reforms in accordance with the work plans. The iterative nature of the Basel standard-development process helped ensure work plans reflected priorities and progress for each reform.

Development of reform proposals and consideration of inputs. During the multiyear process of developing and finalizing a standard, the Basel Committee primarily used information from three main sources to create, review, and refine proposals:

· Member jurisdictions’ positions and technical input. To execute work plans, working groups and task forces worked together to develop initial reform proposals. According to U.S. and Basel Secretariat officials, these proposals were technical in nature and reflected the interests of member jurisdictions, including idiosyncrasies of specific market structures. As members of the groups that developed the reforms, U.S. officials provided proposals and input aligned with U.S. priorities.

· Assessments of quantitative impacts. Basel members used quantitative impact studies to analyze the potential effects of proposed standards on banks’ capital requirements.[44] To conduct the studies, Basel Committee members collected data from banks within their jurisdiction using a standardized template, and banks submitted the completed template on a voluntary basis. The data collected included information on eligible capital; the composition of exposures for credit, market, and operational risk components; and other data relevant to the analysis of potential impacts of a particular reform.

The Federal Reserve was responsible for gathering the data for the United States. Federal Reserve officials stated that they sent the anonymized data to Basel Committee teams, which consisted of staff from Basel Committee members. These data analysis teams then applied various actual and proposed risk weights to the exposures to determine risk-weighted assets under the considered scenarios. The impact assessments allowed Basel members to compare banks’ current capital positions to their projected capital positions under the proposed reforms.

· Public comments and other external inputs. External input was primarily gathered through comments on public consultative documents, which contained information about the proposed standards and results from relevant quantitative impact studies for public review.[45] Members of the public could submit comments on these documents.[46] Working groups and task forces reviewed and summarized the comment letters, informed the PDG of the nature of the comments, and provided the PDG with their views and proposals for further changes, if warranted. In addition, Basel Secretariat officials told us that the PDG and some subgroups held outreach meetings with representatives from large industry groups and other external stakeholders to seek their views on the reforms. Officials from U.S. agencies attended some of these meetings, according to U.S. officials.

Basel Committee members analyzed this information through an iterative process that typically started at the working group level and progressed up the organization. Our analysis of U.S. agency documents found that lower-level groups provided status updates and reported alternatives under consideration to higher-level groups for their discussion. According to U.S. officials, if working group members could not agree on a proposal, they either would propose options for PDG consideration or request additional guidance. The PDG would then further develop and refine the proposal before sending it to the Parent Basel Committee and, as warranted, GHOS for review. Officials stated that during the review process, the PDG, Parent Basel Committee, or GHOS could return the proposal to a lower level in the Basel structure for further work.

Finalization and endorsement of the final standard. Once the Parent Basel Committee determined the proposed changes sufficiently incorporated jurisdictions’ positions, external comments, and quantitative impact studies, it finalized the standards. The Parent Basel Committee often required multiple rounds of consultative documents, reviews of public comments, and quantitative impact studies before finalizing a standard. All final Basel III standards were endorsed by GHOS, in accordance with the Basel Committee charter.

Decision-making by consensus. The Basel Committee makes decisions through a consensus-based process operative at all levels of the organization. U.S. and Basel Secretariat officials explained that the final Basel III standards were achieved through broad agreement among members, rather than through majority agreement or a simple vote. This consensus-based approach was used consistently throughout the organization and for all types of decisions, from agreeing on reform options to finalizing and endorsing standards.[47]

U.S. officials told us that the Basel Committee’s organizational structure—with each group providing direction to and reviewing the work of the group below—helped build consensus in most reform areas.

However, in cases in which members could not reach consensus at the Parent Basel Committee or GHOS levels, the Basel Committee could allow for “national discretion.” Such discretion allows jurisdictions to choose from agreed-upon alternative approaches. For example, the final credit risk standard included an option for jurisdictions to use an alternative to external credit ratings to calculate risk weights, because U.S. law prohibits the use of external credit ratings for bank capital regulatory requirements. In at least one case (the treatment of sovereign debt), the Basel Committee and GHOS determined they could not reach consensus and made no changes to the existing standards.[48]

U.S. Members Considered External Input and Analyses of Potential Effects on U.S. Banks to Inform Their Positions

External Input Informed U.S. Members’ Development of Reforms

U.S. members considered external input, including public comments received on consultative documents, direct feedback from industry stakeholders, and Basel Committee-sponsored industry outreach. This external input helped them develop reform approaches and positions on reform proposals throughout the development process.

Our sensitive report provided some additional information on U.S. members’ specific actions or positions on reforms in response to external input during the development of the final Basel III standards. U.S. agencies determined that these statements were controlled unclassified information; thus, those statements are omitted in this report.

Public comments on consultative documents. From 2011 to 2019, the Basel Committee published 13 consultative documents related to the final Basel III standards, seeking public comment on each reform area through at least one consultative document.[49] Across these 13 documents, the Committee received approximately 750 comment letters, averaging about 57 letters per document.

U.S. comment letters accounted for about 18 percent of total comment letters.[50] The number of U.S. comment letters varied by reform area, ranging from eight letters on the output floor to 47 letters on the standardized approach for credit risk. U.S. commenters made up from about 13 percent (on operational risk) to 38 percent (on the leverage ratio) of total letters submitted for each reform area.

U.S. officials told us public comments on consultative documents were a key source of information to develop the reforms.[51] Specifically, comments provided insights on alternative approaches or methodologies to consider, the adequacy of risk-assessment measures, and potential implementation challenges with proposed reforms.

According to U.S. agency officials, public comments often led them to reconsider initial proposals. One example is the development of reforms to the credit risk standardized approach. Documents we reviewed showed that U.S. members analyzed comments to consider and refine alternative methods for measuring credit risk that did not rely on external credit ratings. As previously stated, U.S. members are prohibited by U.S. law from relying on external credit ratings in their regulations, including regulations pertaining to capital requirements.

In addition, the Basel Committee revised its initial 2014 proposal in response to public comments. In 2014, the Committee’s proposed approach removed references to external credit ratings. However, based largely on public comments, the Committee reintroduced the use of external credit ratings in its subsequent proposal and, ultimately, the final standard.[52] U.S. agency officials stated that they considered the comments and understood the utility of external credit ratings for jurisdictions that could use them.

Federal Reserve officials stated that they also were actively involved in addressing industry concerns over implementation challenges associated with a 2013 proposed standard for market risk.[53] Specifically, in 2014 the Basel Committee proposed an alternative approach for calculating market risk under the standardized approach—the sensitivities-based approach—that ultimately was incorporated into the final standard. Federal Reserve officials stated that U.S. industry participants had identified it as a less burdensome method than the one proposed in 2013, because U.S. banks already were using similar methods in their stress tests of financial condition.[54]

Direct input from industry stakeholders. U.S. members also considered external input received through meetings with U.S. industry groups or banks. In particular, the Federal Reserve initiated meetings with U.S. global systemically important banks to obtain their views on proposed reforms, encourage them to submit comment letters, and request supporting data or analysis.[55] Officials told us their outreach to banks generally occurred during the development or following publication of a consultative document, allowing banks to provide fully informed comment letters. Officials also said they reached out to banks when issues of significant concern arose or if the Basel Committee had not conducted its own outreach.

Specifically, documents show that Federal Reserve officials initiated five meetings with the largest U.S. banks from February 2015 to June 2016. The meetings discussed reforms to the leverage ratio and the standardized approach for credit risk, among other issues.

Officials from OCC and FDIC told us they did not conduct separate, proactive outreach to industry during the development of the reforms. However, OCC officials mentioned that they met with banks or industry groups that contacted them.[56] FDIC officials told us they encouraged interested parties, including banks and industry groups, to comment on consultative documents.

Moreover, the Basel Committee organized meetings with industry stakeholders, including some from the United States, according to U.S. and Basel Secretariat officials. Our analysis of U.S. member documents identified five such meetings in 2014–2016, which discussed industry comments on proposals and other relevant topics. For example, according to an OCC briefing document, the Working Group on Operational Risk met with industry representatives in May 2016 to discuss initial comments on a consultative document.

Analyses Helped U.S. Members Assess and Calibrate Proposals

U.S. members contributed to and considered analyses conducted by the Basel Committee, including quantitative impact studies, and supplemented this information with their own internal analyses. These analyses helped them determine potential impacts on banks’ capital requirements and calibrate various components of the standards.

Our sensitive report provided some additional information on U.S. members’ positions on reforms in response to analyses conducted during the development of the final Basel III standards. U.S. agencies determined that these statements were controlled unclassified information; thus, those statements are omitted in this report.

Quantitative impact studies. The Basel Committee conducted various quantitative impact studies that generally assessed and described estimated impacts of proposed standards on banks’ capital requirements across member jurisdictions. The Committee conducted at least one quantitative impact study to inform the development of each reform area. This included a cumulative quantitative impact study analyzing the coherence and calibration of all the reforms in the 2017 reform package.[57] Agency documents showed, and U.S. officials told us, that the results of these studies were a key source of information for developing policy positions during the standards’ formulation.

These studies helped validate or assess alternatives and calibrate or refine proposals.[58] For example, the Basel Committee used a 2014 quantitative impact study to validate the proposed operational risk standardized approach, which aimed to simplify the framework for operational risk by creating a single, risk-sensitive standardized approach.

Documents also showed that U.S. members and the Basel Committee used quantitative impact studies to calibrate or refine proposals. For example, they used quantitative impact study results to make decisions on the calibration of the output floor. Multiple briefing documents show OCC citing quantitative impact study results related to various proposed output floor levels and their effect on capital requirements. Additionally, in developing the market risk standardized approach, the Basel Committee assessed a proposed approach in a 2015 quantitative impact study. The Committee found that its proposal resulted in market risk capital charges that were close to nine times higher for the standardized approach than the internally modelled approaches and chose to readjust their proposal.[59]

Internal analyses by U.S. members. U.S. members also conducted internal analyses on the potential impact of final Basel III reforms on U.S. banks. As the agency leading the collection of U.S. quantitative impact study data, the Federal Reserve conducted internal analyses using these and other data. These analyses helped U.S. members understand the potential effects of proposals on U.S. banks and informed U.S. negotiating positions.

For example, according to our analysis of U.S. agency documents, in 2014 the Federal Reserve conducted an impact analysis comparing the capital requirements of the standardized approach and advanced measurement approach for operational risk among several large U.S. banks.

From 2018 to 2019, the Federal Reserve also conducted a series of four internal analyses to analyze the collective effect of final Basel III reforms and help U.S. members make data-driven decisions to finalize the standards. These analyses highlighted the effect that proposed Basel III reforms could have on U.S. banks’ binding regulatory capital constraints and total risk-weighted assets for U.S. bank holding companies. According to Federal Reserve officials, they shared key findings and discussed their analyses with OCC and FDIC.

Our analysis of U.S. agency documents showed that FDIC and OCC also conducted some internal analyses to inform their positions and assess potential impacts on U.S. banks. For example, in December 2015 FDIC conducted an impact analysis of a proposed standardized approach for operational risk on U.S. bank capital requirements.

We determined that the actions taken by the U.S. members during the development of the final Basel III reforms generally reflected leading practices in the Office of Management and Budget’s Circular A-4. This circular guides certain U.S. regulatory agencies in the development of high-quality and evidence-based regulatory analysis.[60] For example:

· U.S. members helped identify the need for reform in internal briefing documents and consultative documents that outlined deficiencies and identified Basel Committee and U.S. priorities for the reforms.

· U.S. members considered multiple alternatives in Basel Committee working groups, including for calibrating indicators, applying standards, and estimating risk. To refine alternatives, they presented alternatives to higher-level groups in the Committee and in consultative documents.

· U.S. members evaluated costs and benefits of proposals through quantitative impact studies and public comment reviews. Quantitative impact studies helped U.S. members analyze the effect of proposed standards on banks’ capital, and public comments helped U.S. members identify and analyze potential implementation costs of the proposed standards.

Our analysis indicated that U.S. members’ actions were in alignment with the Office of Management and Budget’s leading practices. See appendix III for a more detailed evaluation of U.S. members’ actions against leading practices.

U.S. Members Actively Participated in the Development of the Final Basel III Reforms to Further Their Reform Priorities

U.S. members had two overarching reform priorities for the final Basel III standards: to address weaknesses that they identified in the Basel framework (primarily by improving the comparability of banks’ risk-weighted ratios), and to bring certain Basel standards closer to U.S. requirements to promote a more level playing field.[61] As previously mentioned, the final Basel III standards included reforms to the internal model and standardized approaches for calculating risk-weighted assets, leverage ratio, and output floor.[62] Our analysis of U.S. documents showed that U.S. members participated actively in the various working groups that developed the standards to further their reform priorities.

Our sensitive report provided information on U.S. members’ positions on specific reforms and actions taken by U.S. members to further their reform priorities during the development of the final Basel III standards. U.S. agencies determined that these statements were controlled unclassified information; thus, those statements are omitted in this report.

Credit Risk Internal Model and Standardized Approaches

Credit Risk Internal Model Approach

To achieve their goal of improving comparability, U.S. members prioritized the adoption of material constraints on the use of bank internal models for credit risk.

The final standard for the credit risk internal model approach placed constraints on banks’ use of internal models and incorporated two key changes. First, it removed the option to use one of two available internal model approaches for credit exposures to financial institutions and large corporations. It also eliminated the use of internal models for equity exposures. Second, where internal models were retained, the standard applied minimum levels to certain parameters (such as probability of default and loss given default) to prevent banks from underestimating expected losses.[63]

Our analysis of U.S. agency documents showed that U.S. members played an active role in the development of this standard. We found that the Risk Measurement Group and the Coherence and Calibration Task Force were the groups that primarily developed the reforms to the credit risk internal model approach. Subject matter experts from all U.S. members participated in the working groups that developed the standard.[64]

Our sensitive report provided information on U.S. agencies’ positions on reforms to the credit risk internal model approach and actions taken by U.S. members to further their priorities for such reforms during the development of the final Basel III standards. U.S. agencies determined that these statements were controlled unclassified information; thus, those statements are omitted in this report.

Credit Risk Standardized Approach

For the credit risk standardized approach, U.S. members prioritized including an option for U.S. banks that did not rely on the use of external credit ratings.

To help promote a level playing field, U.S. members also sought to ensure that this option did not place U.S. banks at a material disadvantage compared to their international counterparts. As discussed previously, U.S. law prohibits U.S. regulators from referring to external credit ratings in their regulations, including bank capital rules.[65] U.S. agency officials stated that the United States was one of few Basel jurisdictions that did not rely on external credit ratings by law or by choice.[66] Thus, U.S. agency officials told us they bore primary responsibility for ensuring a workable standard that met this unique requirement without disadvantaging U.S. banks. Specifically, they sought an option that was equivalent in effect to the approach likely to be implemented by other jurisdictions that could rely on external credit ratings.

Where applicable, the final standard for a credit risk standardized approach offered two options for calculating credit risk. The first option used external credit ratings and directed banks to conduct sufficient due diligence when using such ratings.[67] The second option used alternatives to external credit ratings, known as risk drivers, to accommodate U.S. legal prohibitions.[68]

Our analysis of U.S. agency documents found that U.S. members played an active role in the development of the credit risk standardized approach. We found that the Task Force on Standardized Approaches was the group that primarily developed the reforms to the credit risk standardized approach. Subject matter experts from all U.S. members participated in the working group that developed the standard.[69]

Our sensitive report provided information on U.S. agencies’ positions on reforms to the credit risk standardized approach and actions taken by U.S. members to further their priorities for such reforms during the development of the final Basel III standards. U.S. agencies determined that these statements were controlled unclassified information; thus, those statements are omitted in this report.

Market Risk Internal Model and Standardized Approaches

To address certain weaknesses in the Basel framework, U.S. members and the Basel Committee sought to overhaul market risk standards by conducting a fundamental review of the trading book.[70]

The final market risk standard consisted of revisions to the internal model approach that aimed to address risks observed during the global financial crisis and reinforce supervisory approval processes for the use of internal models.[71] It also included a revised standardized approach designed to be more risk-sensitive and designed and calibrated to serve as a credible fallback to the internal model approach. Additionally, the standard established stricter criteria for assigning financial instruments to the trading book. It also included a simplified standardized approach for use by banks that have small or noncomplex trading portfolios.

Our analysis of U.S. agency documents found that U.S. members played an active role in developing the market risk reforms. We found that the Market Risk Group, also referred to as the Trading Book Group, was the group that primarily developed the market risk reforms. The Federal Reserve co-chaired this working group, and representatives from all U.S. members participating in the group’s task forces.[72] Federal Reserve officials told us that they provided core technical expertise for developing the standards.

Our sensitive report provided information on U.S. agencies’ positions on market risk reforms and actions taken by U.S. members to further their priorities for such reforms during the development of the final Basel III standards. U.S. agencies determined that these statements were controlled unclassified information; thus, those statements are omitted in this report.

Operational Risk Internal Model and Standardized Approaches

To achieve their goal of improving comparability, U.S. members sought to eliminate the internal model approach for operational risk. In turn, they also sought to develop a more risk-sensitive standardized approach.[73]

The final Basel III reforms for operational risk capital eliminated the internal model approach. The reforms also replaced three standardized approaches with a single risk-sensitive standardized approach. This new approach to determine operational risk capital requirements was based on a new measure of bank gross income and used the bank’s historical operational risk losses.[74]

Our analysis of U.S. agency documents found that U.S. members played an active role in the development of the standardized approach for operational risk. We found that the Working Group on Operational Risk was the group that primarily developed the operational risk reforms. Subject matter experts from all U.S. members participated in the working group that developed the reform.[75]

Our sensitive report provided information on U.S. agencies’ positions on operational risk reforms and actions taken by U.S. members to further their priorities for such reforms during the development of the final Basel III standards. U.S. agencies determined that these statements were controlled unclassified information; thus, those statements are omitted in this report.

Leverage Ratio

In part to level the playing field for U.S. banks, U.S. members prioritized establishing a new leverage ratio buffer for global systemically important banks that was similar to the existing requirement for certain U.S. banks.[76]

The final standard makes the combined leverage ratio standard for these large internationally active banks more stringent by adding a capital buffer on top of the existing minimum leverage ratio. Introduced in 2010, the leverage ratio requirement set a minimum requirement of capital over assets to act as a non-risk-based backstop to the risk-based capital standards and limit excessive leverage.[77] The final standard added a capital buffer on top of this ratio for global systemically important banks commensurate with their systemic footprint.[78]

Our analysis of U.S. agency documents found that U.S. members played an active role in the development of the leverage ratio standard. We found that the Leverage Ratio Group and the Coherence and Calibration Task Force were the groups that primarily developed the reforms to the leverage ratio standard. Subject matter experts from all U.S. members participated in the working groups that developed the standard.[79]

Our sensitive report provided information on U.S. agencies’ positions on leverage ratio reforms and actions taken by U.S. members to further their priorities for such reforms during the development of the final Basel III standards. U.S. agencies determined that these statements were controlled unclassified information; thus, those statements are omitted in this report.

Output Floor

To achieve their goals for improving comparability and promoting a level playing field, U.S. members actively participated in the development of reforms to the Basel framework’s output floor. A stronger output floor could help bring the expectations of non-U.S. banks more in line with U.S. requirements. This was particularly important because, in accordance with section 171(b) of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (known as the Collins Amendment), all U.S. banks are subject to the same capital floor. In turn, banks must calculate risk-based capital requirements using standardized approaches.[80] This means that U.S. internationally active banks, which use advanced approaches, must comply fully with risk-based capital requirements calculated using standardized approaches.

According to the final Basel III output floor standard, calculations of risk-weighted assets generated by banks’ internal models cannot, in aggregate, fall below 72.5 percent of the risk-weighted assets computed by standardized approaches. This additional aggregate risk-based calculation in the Basel framework is based on the newly reformed standardized approaches.

Our analysis of U.S. agency documents found that U.S. members played an active role in the development of the output floor standard. U.S. members described lengthy negotiations, and Basel Secretariat officials stated that output floor negotiations delayed the finalization of the 2017 reforms by a year. Our analysis of U.S. agency documents found that negotiations on the output floor started in earnest in 2015 with the creation of the Coherence and Calibration Task Force. The task force was charged with assessing the interaction, coherence, and calibration of all standards in the Basel framework, including the output floor. All U.S. PDG members participated in the task force and supported reforms aligned with U.S. priorities.[81]

Our sensitive report provided information on U.S. agencies’ positions on output floor reforms and actions taken by U.S. members to further their priorities for such reforms during the development of the final Basel III standards. U.S. agencies determined that these statements were controlled unclassified information; thus, those statements are omitted in this report.

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of the sensitive and public versions of this report to the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (Federal Reserve), FDIC, and OCC for review and comment. The Federal Reserve, FDIC, and OCC provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate. In addition, the Basel Committee Secretariat provided technical comments on the public version of this report, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, Chair of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Acting Chairman of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Acting Comptroller of the Currency, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at (202) 512-8678 or clementsm@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix IV.

Michael E. Clements

Director, Financial Markets and Community Investment

Appendix I: Overview of Selected Components of the Final Basel III Standards and a Proposed Standard

This appendix presents information on selected components of the final frameworks for credit, operational, and market risk in the Basel III standards. It also describes their development, including the role of U.S. members. Specifically, we address the

1. requirements for corporate exposures to qualify as “investment-grade” under the credit risk framework when external credit ratings are not used;[82]

2. calibration of the multipliers and dampener for calculating the minimum operational risk capital requirements under the operational risk framework; and

3. calibration of factors and minimum thresholds for the profit and loss attribution tests under the market risk framework.

We also describe U.S. members’ role in developing a proposed standard for operational risk capital requirements for high-fee income banks, which was not included in the final Basel III standards.

This report is a public version of a sensitive report we issued in December 2024.[83] Appendix I of the sensitive report included some statements that the U.S. agencies identified as controlled unclassified information. The statements generally described U.S. members’ actions or positions on reforms related to U.S. members’ role in the development of the selected final or proposed standards discussed in this appendix. We omitted those statements in this report.

Determination of Risk Weights for Corporate Exposures When External Credit Ratings Are Not Used

Final Basel III standard. Under the final Basel III credit risk framework, banks in jurisdictions that do not or cannot use external credit ratings for regulatory purposes, such as the United States, generally assign a default credit risk weight of 100 percent to corporate exposures (certain loans and other assets of the bank).[84]

However, a lower risk weight of 65 percent can be applied if the exposure qualifies as “investment-grade” by meeting two criteria: (1) the bank determines the corporation has adequate capacity to meet its financial obligations and (2) the corporation, or its parent company, has securities outstanding on a publicly traded exchange.[85]

Purpose of the standard. An effective credit risk framework allows banks to absorb losses when borrowers or other counterparties fail to meet their financial obligations, such as by defaulting on a loan. This is achieved by assigning risk weights to exposures that reflect their perceived level of risk. This risk-sensitive approach requires banks to hold more capital against higher-risk exposures, such as a loan with a greater probability of default.

Development of the standard. In a 2015 consultative document, the Basel Committee proposed a two-pronged test for corporate entities to qualify for the reduced risk weight.[86] The proposal included the same criteria as the final standards, but with a 75-percent risk weight (rather than the 65-percent weight adopted in the final standard) for investment-grade corporate exposures. According to the Basel Committee, these criteria effectively balanced simplicity and risk sensitivity, and promoted comparability across banks and jurisdictions—the goals for the final Basel III standards. To gather external input, the Committee solicited public comments, receiving 121 comment letters, 20 of which came from U.S. commenters.[87]

Following the proposal, the Committee found that the 65-percent weight was more comparable to the approach used in other jurisdictions that could rely on external credit ratings, according to Federal Reserve officials.[88]

In 2017, the Group of Central Bank Governors and Heads of Supervision endorsed the final standard for corporate exposures as part of the final Basel III standards.[89]

U.S. member agencies’ role. As noted previously, U.S. agency officials told us they played a key role in developing an alternative approach to use of external credit ratings, in part because the United States prohibits the use of external ratings for bank capital regulation.[90] Each U.S. member was represented on the task force responsible for developing the standard.

Our sensitive report provided information on U.S. agencies’ positions on the treatment of corporate exposures in the credit risk standardized approach and related actions taken by U.S. members during the development of the final Basel III standards. U.S. agencies determined that these statements were controlled unclassified information; thus, those statements are omitted in this report.

Calibration of the Minimum Operational Risk Capital Standard

Final Basel III standard. Under the operational risk framework, banks must use a standardized approach to calculate their minimum capital requirements for operational risk. This refers to the minimum regulatory capital a bank must hold to guard against losses arising from its internal operations or external events. The operational risk capital requirement takes into account the bank’s gross income, expenses, and internal operational losses.

The standard uses specific risk measures—multipliers or dampeners—to calculate a bank’s minimum operational risk capital requirements, as follows:

· Banks must multiply a monetary proxy of their income and expense data by a marginal coefficient of 12 percent, 15 percent, or 18 percent. The result of this calculation is known as the business indicator component. Greater measures of bank income and expenses result in banks using a higher marginal coefficient.

· Banks with a measure of bank income of the equivalent of 1 billion euros or more are required to calculate their average annual losses caused by operational risk events (over a 10-year period) and multiply the monetary value of those losses by 15.[91] This is known as the loss component. Banks are to include all operational loss events with a value equivalent to 20,000 euros or more in the loss component.[92]

· Banks must multiply the ratio of the loss component to the business indicator component by a 0.8 exponent as part of the calculation of the internal loss multiplier.[93]

· Operational risk capital requirements are calculated by multiplying the business indicator component and the internal loss multiplier. Risk-weighted assets for operational risk are equal to 12.5 times the operational risk capital requirements.

Purpose of the standard. An effective operational risk capital framework allows banks to absorb unexpected losses resulting from inadequate or failed internal processes, people, systems, or external events. For example, a bank may face losses from events such as processing errors, internal and external fraud, legal claims, and business disruptions.

The framework employs specific risk measures to calculate operational risk capital requirements. These measures are intended to adjust the calculation based on the risks associated with certain values. A multiplier is applied to the business indicator component, which increases as the bank’s income increases. This reflects Basel Committee analysis that showed that operational risk grows disproportionally with activity levels.

A multiplier is also applied to operational risk losses exceeding the equivalent of 20,000 euros, reflecting the assumption that banks with such losses are more likely to experience them again.

Development of the standard. The final standard, adopted in 2017, followed years of work. This included at least two quantitative impact studies and two consultative documents issued for public comment in 2014 and 2016, according to our review of publicly available Basel Committee documents.[94]

The Committee adopted simplified versions of some of the proposed measures. Specifically, the final business indicator component was simplified by reducing the number of marginal coefficients from five (ranging from 11 percent to 29 percent) to three (from 12 percent to 18 percent).[95] Similarly, the final loss component was simplified by adopting a single multiplier (15) instead of requiring use of one of three multipliers (7, 14, or 19), based on the size of the specific loss event.[96]

The final standard also reduced the overall operational risk capital requirements compared to the 2016 proposal by lowering the maximum marginal coefficient for calculating the business indicator component from 29 percent to 18 percent, according to Federal Reserve officials.

The exponent in the internal loss multiplier was included in the final standard, although it was not part of the 2016 consultative document.