FEDERAL PROTECTIVE SERVICE

Actions Needed to Address Critical Guard Oversight and Information System Problems

Report to the Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, House of Representatives

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO-25-108085. For more information, contact David Marroni, (202) 512-2834 or MarroniD@gao.gov, or Howard Arp, (202) 512-6722 or ArpJ@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-1080858, a report to the Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, House of Representatives

Actions Needed to Address Critical Guard Oversight and Information System Problems

Why GAO Did This Study

Federal real property has been on GAO’s High Risk List since 2003, in part due to threats to federal facilities. FPS, within the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), is responsible for protecting thousands of federal facilities. For fiscal year 2024, FPS had contract guards at about 2,500 facilities at a cost of $1.7 billion.

This report discusses the extent to which (1) FPS contract guards detect certain types of prohibited items at selected federal facilities, (2) FPS uses its covert testing data to improve detection rates, and (3) the Post Tracking System has improved oversight of contract guards.

GAO conducted 27 covert tests at a nongeneralizable sample of 14 federal facilities and analyzed data from FPS’s covert tests. GAO selected federal facilities based on public access; location; and size, among other factors. GAO also analyzed numerous Post Tracking System documents and interviewed stakeholders, including FPS officials, federal tenants, guard unions, and security guard companies.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making three recommendations to FPS to collect and use better covert testing data to improve guard performance. GAO also recommends that the DHS Chief Information Officer determine whether to terminate and replace the Post Tracking System, or make corrective actions to the existing system, including a schedule for providing tenants with timely communication of guard shortages. DHS agreed with all four recommendations.

What GAO Found

The Federal Protective Service (FPS) oversees about 13,000 contract guards who screen visitors entering federal facilities for prohibited items. FPS contract guards detected prohibited items in 14 of GAO’s 27 covert tests. During the tests, GAO investigators attempted to bring a bag into selected federal facilities containing one of the following three prohibited items—a baton, pepper spray, or a multi-purpose tool with a knife. Furthermore, GAO analysis of nearly 500 FPS covert tests found that contract guards did not detect prohibited items in about half of FPS tests from 2020 through 2023.

FPS collects data about its covert tests, but data reliability issues prevent FPS from using that information to improve detection rates. This is due in part to the information (1) being reported inconsistently, (2) not identifying specific and actionable causes of guards failing to detect prohibited items, and (3) not consistently resulting in appropriate guard training targeted at addressing cause. Collecting better data on its covert tests, analyzing those data, and using what it learns from that analysis could help FPS improve guard performance in detecting prohibited items.

FPS deployed the Post Tracking System in 2018 to improve oversight of the contract guard program. However, 6 years later, the system is beset with problems. In April 2022 FPS testing, PTS did not complete 782 of 1,487 selected tasks to meet system requirements. FPS officials said that most of the issues were resolved, but FPS did not provide supporting documentation. Accordingly, the paper-based system that the Post Tracking System was designed to replace remains the system of record for FPS.

This, in turn, means that the system is not meeting the mission requirement of remotely verifying in real time that posts are staffed by qualified guards. Continuing to rely on the antiquated, paper-based guard tracking process adversely affected communication with tenants on guard shortages. A lack of guards led to office closings and impaired service to the public—according to agency officials, since 2022, the Internal Revenue Service closed 30 Taxpayer Assistance Centers for a full day, and the Social Security Administration closed offices in 510 separate instances. While guard shortages would have still occurred, officials from those tenant agencies said that real-time notification of guard shortages, like that promised by the Post Tracking System, could have allowed them to better react to the guard shortages.

Abbreviations

|

CIO |

chief information officer |

|

DHS |

Department of Homeland Security |

|

FPS |

Federal Protective Service |

|

GSA |

General Services Administration |

|

IRS |

Internal Revenue Service |

|

IT |

information technology |

|

PTS |

Post Tracking System |

|

SSA |

Social Security Administration |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

March 11, 2025

The Honorable Sam Graves

Chairman

The Honorable Rick Larsen

Ranking Member

Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure

House of Representatives

The Federal Protective Service (FPS) within the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) is responsible for protecting about 9,000 federal facilities. FPS officers and more than 13,000 contract guards control access to facilities, conduct access point screenings to detect prohibited items, and respond to safety and security emergencies.[1] To carry out its mission, FPS spent almost $1.7 billion on contract guards, which represented about 76 percent of its budget, in fiscal year 2024.

FPS serves an important role in protecting federal facilities against threats. Past attacks include the April 1995 bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, in which 168 people died. More recent attacks—which FPS contract guards stopped— include a 2019 shooting at a Dallas federal facility, a 2021 shooting at a Social Security Administration (SSA) facility, and an armed attempt to breach security at the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Cincinnati Field Office in 2022.

Managing federal real property has been on GAO’s High Risk List since 2003, in part due to threats to federal facilities.[2] In our past work, we identified several challenges to the security of federal facilities. In covert tests conducted in 2009, we carried components of improvised explosive devices into federal facilities, undetected by FPS contract guards.[3] In 2010, we reported that in FPS’s internal covert testing, contract guards identified prohibited items in 18 of 53 tests.[4] We found these security vulnerabilities were potentially caused by insufficient training for guards and the agency’s failure to maintain a comprehensive system to ensure that guards were appropriately trained. Other challenges included staffing levels, human capital management, and inconsistent guidance about how and when guard inspections should be performed.[5] We made a number of recommendations to FPS to help address these issues, some of which it has implemented. FPS responded to one of our recommendations by creating a Post Tracking System (PTS) to, among other things, verify that contract guards have the qualifications to staff a specific post.[6]

You asked us to review security at FPS-protected facilities. This report examines the extent to which (1) FPS contract guards are detecting certain types of prohibited items at selected federal facilities, (2) FPS uses its covert testing data to improve detection rates, and (3) PTS has improved oversight of the contract guard program. This report presents the final results of our review; we previously reported preliminary results of this work in a July 23, 2024, testimony statement.[7] It is the public version of a "law-enforcement sensitive" report that we issued on January 28, 2025. For the public report, the team removed information deemed sensitive.

To determine the extent to which FPS contract guards are detecting certain types of prohibited items at selected federal facilities, we conducted 27 covert tests by attempting to bring prohibited items (specifically, a multipurpose tool with a knife, a police baton, or pepper spray) into a nongeneralizable sample of 14 federal facilities.[8] We selected facilities based on several factors, including public access, location, size, and the number of federal tenants in the facilities.

All of the facilities in our sample housed federal offices that the public visits—such as Social Security offices or Internal Revenue Service (IRS) Taxpayer Assistance Centers—and were protected by FPS contract guards who screened visitors for prohibited items. We included single-tenant and multitenant facilities in our sample and selected facilities protected by contract guards who were hired by multiple security guard contractors. To ensure regional variation in our sample, we selected facilities located in six of FPS’s 11 regions that housed large, medium, and small numbers of facilities protected by contract guards.

We also selected buildings that varied by facility security level. The Interagency Security Committee Standard for determining facility security levels outlines several factors that facility managers should use, including the facility’s population and size. Facility security levels range from level 1 (lowest risk) to level 5 (highest risk).[9] In this report, we refer to levels 4 and 5 as high-risk and levels 1 through 3 as low-risk. We categorized 11 of the 14 federal facilities we selected as high-risk and three as low-risk. Due in part to their security level, these facilities had varying levels of security and screening procedures.

To examine the extent to which FPS uses its covert testing data to improve detection rates, we analyzed FPS data from fiscal years 2020 through 2023 about the outcomes of its 529 internal covert tests.[10] To assess the reliability of FPS data, we (1) reviewed documentation on each of the 529 cases, (2) performed electronic testing for obvious errors in accuracy and completeness; and (3) discussed the issues we identified with agency officials.

Our review of the 529 cases identified 41 cases that we excluded from our analysis because the associated narratives (1) did not describe a covert test with a prohibited item, (2) did not support the stated outcome of the test, or (3) had insufficient information to determine if a covert test occurred. We determined that the data for the remaining 488 cases were sufficiently reliable for the purpose of describing the number and outcomes of FPS covert tests. However, the data were not sufficiently reliable for reporting on additional information about those tests, such as the types of tests FPS conducted, or the prohibited items used in those tests. For the 488 remaining cases, our analyses identified three types of issues that commonly occurred; these issues are discussed later in this report. We also interviewed FPS officials to understand any steps FPS had taken to use the information in the covert testing dataset to improve detection rates.

To assess whether PTS has improved oversight of the contract guard program, we observed PTS operations and reviewed PTS program documentation, including life cycle cost estimates, guidance, concept of operations, integrated master schedules, and operational requirements testing reports.[11] We analyzed the results of an operational assessment FPS performed on PTS in April 2022. We also analyzed PTS usage data by region and security guard contractor for April and May 2024. We determined the data used were sufficiently reliable for the purpose of evaluating system usage. We also interviewed FPS officials, federal tenant agencies, contract guard and FPS unions, and security guard companies about system capabilities that support contract guard oversight.

We conducted this performance audit from September 2023 to January 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We conducted our related investigative work in accordance with investigation standards prescribed by the Council of the Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

FPS Roles

FPS conducts physical security, law enforcement, and contract guard oversight activities at civilian federal facilities across the country. A majority of FPS-protected facilities are under the custody or control of the General Services Administration (GSA).[12] Among other responsibilities, FPS manages and oversees contract guards for various federal agencies at roughly 2,500 facilities.[13] In its oversight role, FPS is to monitor vendor-provided training; manage the contracts of vendors who provide contract guards; and conduct other oversight activities, such as post visits and post inspections.

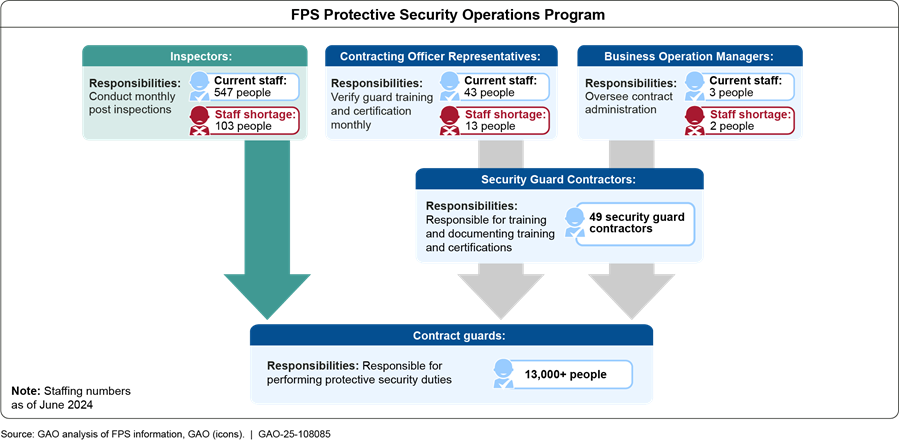

FPS inspectors, contracting officer representatives, and business operation managers are responsible for managing contract guards. Inspectors conduct monthly post inspections. Contracting officer representatives verify guard training and certification monthly. Business operation managers oversee contract administration.[14] Contract guard vendors train contract guards and document training and certifications in FPS systems.

The FPS Protective Security Operations Program responsible for contract guard oversight has experienced staff shortages for years. Figure 1 depicts staffing shortages for oversight personnel in specific positions.

Note: FPS officials said additional headquarters and regional officials also play a role in providing oversight of the contract guard workforce. These officials are not depicted in the above graphic.

Prohibited Items

The Interagency Security Committee, of which FPS is a member, issued the Items Prohibited in Federal Facilities, An Interagency Security Committee Standard, which establishes a baseline list of prohibited items.[15] That list includes firearms, dangerous weapons, and explosives because those items can cause injury, death, or property damage.[16] The standard notes that prohibited items also include any item banned by any applicable federal, state, local, or tribal ordinance. According to this standard, the list of prohibited items applies to all facility occupants, contractors, and visitors.

In some cases, the list of prohibited items is broader than what is illegal to carry in the jurisdictions where the federal facilities are located. For example, carrying pepper spray for self-defense purposes or pocketknives with a blade over certain lengths might be legal within a particular jurisdiction, but they are on the Interagency Security Committee’s recommended baseline list of items generally prohibited inside federal facilities.

According to FPS officials, if an individual attempts to enter a federal facility with a prohibited yet otherwise legal item, the individual must remove the item from the property. Further, officials said FPS contract guards are authorized to detain individuals who refuse to comply with the contract guard’s request to remove the item. FPS officials said that if an individual attempts to enter a federal facility with an illegal item, contract guards are authorized to seize the item; it is up to FPS personnel to issue a citation or arrest the individual, if necessary.

Data Systems

In several reports since 2009, we have repeatedly reported that FPS’s data systems for overseeing guards were not reliable.[17] As part of its efforts to address our recommendations from these reports, FPS began to develop several data systems in 2013 to improve contract guard oversight.

PTS is a web-based application that was expected to be the system of record for ensuring that every post was staffed by a qualified guard in every FPS-protected facility. FPS designed it to replace the paper documentation, periodic inspections, and other manual processes that FPS used to oversee contract guards. In a 2014 publication, FPS highlighted PTS’s planned capabilities and reported that relying on paper documentation was inefficient and did not allow for comprehensive

verification of whether posts were staffed by the correct personnel with required training and certifications for the proper time frames.[18]

As outlined in PTS’s Concept of Operations, the system’s planned capabilities included:

· authenticating the identity of a contract guard before they staff a post,

· confirming the contract guard is properly trained and currently certified to stand post,

· confirming the contract guard is currently suitable (cleared) to stand post, and

· capturing the number of hours contract guards worked at the post for billing purposes.[19]

According to FPS officials, DHS’s Office of the Chief Information Officer (CIO), Science and Technology Directorate, FPS, and contractors developed and managed PTS. The FPS CIO provided high-level input at various stages. IT contractors assisted in developing requirements, integrating FPS database information, and maintaining the system.

FPS is responsible for overseeing contractors, maintaining and upgrading PTS, and resolving system integration issues. The security guard contractors are responsible for providing and maintaining the tablet that hosts the PTS application software, installing software updates, and providing a wireless account for device connectivity.

Based on responses to a 2014 request for information, FPS concluded that commercial products on the market could meet 60 percent of its requirements. Consequently, FPS relied on commercial off-the-shelf software that it configured to meet mission needs. At that time, FPS anticipated that the software would require only minor changes to customize and integrate it into FPS’s existing system architecture.

Contract Guards Detected Prohibited Items About Half the Time in Covert Tests

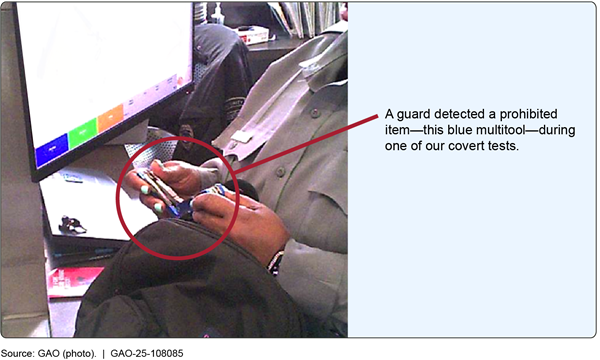

Our covert testing. In 14 of the 27 tests we conducted at selected locations, FPS contract guards detected the prohibited items we were attempting to smuggle into the facility. During our covert tests, our investigators had a prohibited item—specifically, a multi-purpose tool with a knife, a police baton, or pepper spray—inside of a bag that they brought into each facility.[20] See figure 2 for a photo of a contract guard who successfully detected one of those prohibited items.

FPS covert testing. FPS regularly conducts covert testing to evaluate contract guards’ ability to detect prohibited items.[21] We reviewed FPS covert testing data from fiscal years 2020 through 2023 and found that contract guards detected prohibited items at a rate consistent with our test results.

In fiscal years 2020 through 2023, FPS conducted about 500 covert tests to evaluate contract guards’ ability to detect prohibited items.[22] Starting in 2021, FPS officials began to take steps to increase the consistency of their covert testing across regions. For example, since 2022, all FPS regions use items from a standardized test kit to ensure that similar items are tested across regions, according to an FPS official.

FPS prohibited items tracking. Over the past 4 years, contract guards successfully detected many items that are prohibited in federal facilities.[23] According to our analysis of FPS data, contract guards detected more than 750,000 prohibited items from fiscal year 2020 through fiscal year 2023.

FPS Collects Information on Its Covert Tests but Does Not Have a Process to Improve Detection

FPS’s internal covert testing database houses information about the results of internal covert tests, the causes for not detecting prohibited items, and the types of remediation training implemented when guards fail covert tests. However, according to our analysis, information in the database: (1) is inconsistently reported, (2) is not sufficiently specific on causes, and (3) does not consistently result in appropriate training targeted at addressing cause. Further, FPS does not use the evidence it collects to drive systematic efforts to improve guards’ capacity to detect prohibited items.

· Inconsistent data. Our analysis of data in the covert testing database found that FPS data are often inconsistent, inaccurate, and not reliable. For example, similar outcomes of similar tests are recorded differently (some appear as “pass” and some as “fail”), narrative descriptions have inconsistent levels of detail, and labels for test scenarios do not always match the narrative descriptions.

According to Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, agencies should use quality information to achieve the agency’s objectives.[24] For FPS, that means data should be accurate, consistent, and usable.

A key factor contributing to the unreliable data is that FPS has provided limited guidance to staff. Our review of the FPS covert testing manual found that it directs testing officials to draft a narrative description of the details of the test, the test device used, and whether the test outcome was detected or not detected. The manual does not address ways to ensure (1) consistency among narrative descriptions and test results or (2) accuracy and completeness of the descriptions. Without reliable information on the results of covert tests, those tests may not fulfill a key purpose of preventing prohibited items from entering federal buildings and endangering occupants. FPS agreed that additional guidance and data quality checks could improve the consistency and accuracy of the data.

· Reasons for not detecting prohibited items. Failure rates provide FPS with some insight about how effectively contract guards detect prohibited items, but more information is needed to understand why contract guards failed those covert tests. FPS’s covert testing dataset includes a column heading entitled “reason for failure.” However, according to our analysis of FPS data for the 488 cases we reviewed, FPS listed “human factor” as the cause for more than 80 percent of them. Three other causes were entered in the reason for failure column: “training/process/technique” for about 15 percent of cases, “equipment” (1 percent), and “policy/post orders” (0.4 percent). In those cases where “human factor” is listed as the cause, we found multiple instances when the narrative description indicated the cause could more accurately be described as equipment issues, guards’ failure to conduct secondary screenings properly, guards’ failure to notify officials after detecting prohibited items, or other specific factors.

Enhancing the specificity and accuracy of the cause for failure in the database could yield significant benefits for FPS and is consistent with Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government that call for management to use quality information to achieve the agency’s objectives.[25] FPS officials agreed that “human factor” is too broad to identify the underlying cause of the failure or to pinpoint proactive steps that could prevent similar failures in the future. If FPS improves its guidance and the data in the covert testing database, it could better understand what happened during the covert test and be able to determine what corrective action would most effectively address the cause of each failure.

· Remedial training. In our analysis of FPS data from fiscal year 2020 to fiscal year 2023, we found that security guard contractors assigned remedial training for similar failures inconsistently. For example, the types of assigned remedial training—and the duration of that training—varied when guards failed to detect improvised explosive devices during FPS covert tests. Some guards received explosive detection remedial training that was clearly aligned with the failure, some received unrelated training that focused on screening sensitive areas of the body, and some were required to retake the entire training on screening for prohibited items, only part of which is directly related to detection of improvised explosive devices.

In explaining the variation, FPS officials told us they had not previously dictated the type of remedial training that security guard contractors should provide. Instead, FPS had generally allowed contractors to determine what type of training they would provide for their guards. For example, according to FPS, security guard contractors could have contract guards retake the entire training on screening for prohibited items—regardless of the cause of the failure—if the vendor could simply add the contract guard to an upcoming training that was already scheduled.

In August 2023, FPS implemented a new process, which requires FPS officials to review and approve the corrective action plans that security guard contractors develop when a covert test failure occurs. Because this new process was implemented at the end of fiscal year 2023, potential impacts of that change, if any, are not reflected in the data we analyzed.

FPS’s efforts to develop this new process demonstrate that FPS is taking some steps to improve the consistency of remedial training. In addition, while an FPS approval or denial of a proposed corrective action would provide the contractor with some information, contractors could benefit from more detailed FPS guidance that explicitly outlines the types of corrective actions that would be most appropriate to implement for specific causes of failures.

According to Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government and leading practices for training, agencies should externally communicate quality information to ensure that the training that security guard contractors provide is connected to improving guards’ performance.[26] If FPS provides security guard contractors with guidance about the type and duration of training needed when guards fail covert tests, those contractors will have the information they need to assign appropriate corrective action(s) that address cause and lead to improved detection rates.

Improving the quality and consistency of the data it collects could drive a systematic continuous improvement process and better position FPS to take informed actions to improve guards’ detection capabilities.[27] Potential actions could include redesigning training for contract guards, implementing standard operating procedures, or updating agency polices.

Our past work found that using evidence to learn can help decision-makers (1) better understand what led to the results the agency achieved, and (2) identify actions to improve those results. In its strategic plan, FPS indicated that it is committed to developing structures that support evidence-based decision-making. Implementing such an evidence-based improvement process could help FPS achieve better results.

PTS Is Not Providing Expected Capabilities to Improve Contract Guard Oversight

Although FPS intended PTS to replace its obsolete paper-based system and enhance guard oversight, the system experienced unexpected costs and delays that have precluded full deployment. More importantly, 4 years after initial deployment, April 2022 testing of system requirements showed that 782 of 1,487 PTS requirements were not being met. As a result, PTS cannot remotely verify that guard posts are staffed based on real-time data and is not the system of record for any contract or building. These challenges created more work for security guard contractors and undermined timely communication with tenant agencies, such as the SSA.

PTS Experienced Unexpected Costs and Development Delays

In March 2016, FPS estimated a PTS life cycle cost estimate of over $91 million, of which the agency would pay almost $38 million, and the security guard contractors would pay over $53 million.[28] In 2019, FPS increased the estimate of its costs to $41.7 million. FPS attributed the increase to unexpected reconfiguration costs and the need to establish a Help Desk for users. According to FPS officials, while the 2019 life cycle cost estimate captured an increase in the FPS direct costs for the system, it also identified a decrease in the vendor costs of approximately $4.1M, resulting in a total program cost of $90 million.

From fiscal years 2013 through 2024, FPS reported spending about $27 million on developing and implementing the system. This amount does not include any money the security guard contractors spent on hardware and training for contract guards. For fiscal year 2025, it requested $3 million for further system development and implementation.

PTS has also faced schedule delays. In 2018, FPS and DHS reported that PTS had fallen behind schedule by over 2 years in meeting system milestones due to unexpected design complexities, software development delays, personnel shortages, and vendor communications issues.[29] In 2018, FPS awarded a multiyear contract to develop, integrate, deploy, and manage PTS. That same year, FPS began deploying PTS to the contract guard companies for use in the field, even though the issues driving the delays had not been resolved.

FPS’s Operational Requirements report estimated that it would successfully implement PTS’s system capabilities and requirements in all 11 regions no later than the second quarter of fiscal year 2021. It is now uncertain when PTS will be fully implemented because FPS is not using a schedule with tasks and milestones to address requirements and challenges. FPS stopped updating the PTS Integrated Master Schedule in 2021.[30]

Testing Revealed That PTS Was Not Meeting System Requirements

In April 2022, FPS assessed the extent to which PTS was meeting its requirements and determined that the system failed to complete 782 of 1,487 system requirement tasks.[31] Specific examples of tasks that PTS did not meet include:

· verifying post staffing against the requirements of post orders;

· providing notifications to authorized users indicating that a contract guard has checked in or out of a post within 5 minutes;

· capturing and recording a contract guard’s check-out date and time;

· providing notification to the contract guards and authorized users when the contract guard’s training and certifications will expire within 30 days;

· providing notifications to authorized users when a post is not staffed to post requirements during operational hours;

· enabling authorized users to see the time a post is no longer staffed;

· enabling authorized users to query the current staffing status of one or more posts;

· providing reports from system-generated alerts regarding reasons why posts were unstaffed; and

· providing automated electronic communications from FPS to stakeholders to disseminate time-sensitive information such as operational or system alerts.

According to FPS officials, as of January 2025, most of these issues have been resolved but FPS did not provide supporting documentation.

PTS Technology Issues Adversely Affect Security Guard Contractors

While 61 of the 92 security guard contracts require PTS deployment, none of the contractors can use it as the system of record for validating guard credentials or billing. According to its vendor guide, PTS should automate oversight of contract guards, including automatically and remotely monitoring guard posts in real time to ensure that each post is staffed as required by qualified and cleared guards.[32] However, FPS officials told us that PTS cannot remotely verify that guard posts are staffed based on real-time data. For example, FPS officials were unable to identify the guards on post for our covert tests or their qualifications using PTS. Ultimately, this problem affects security guard contractors and tenant agencies with contract guards at federal facilities.

Security guard contractors said they continue to spend time and resources troubleshooting PTS technology issues. Two guard contractors said they needed to assign additional IT specialists to exclusively troubleshoot PTS issues, further increasing costs for a system that they have no plans to use as the system of record. According to FPS officials, security guard contractors are required to implement PTS and may also be required to hire additional IT specialists to address deficiencies. FPS officials also said they have solicited and received feedback on PTS from some security guard contractors at quarterly contractor meetings.

Guard contractors and FPS officials said part of the problem is that PTS does not always allow qualified guards to sign into the system due to technology issues with guard identification cards, vendor-supplied equipment, or internet connection problems. Security guard contractors said their guards become frustrated by the myriad problems and give up on using the system since it is not the system of record. Further, when multiple posts exist in one facility, FPS may set up a single post where contract guards sign in using PTS. However, according to a security guard contractor, the system sometimes crashes or stops working when multiple contract guards sign in or out around the same time. For example, one security guard contractor official said it is common for multiple contract guards to stand in line waiting to sign in or out, creating a long delay during shift changes. Furthermore, the company official said that if the contract guard cannot sign out by the time their shift ends, the company pays overtime, an additional cost the company did not anticipate.

Recognizing the challenges it has faced in deploying PTS, FPS established a Help Desk in 2022. In 2022 and 2023, the FPS Help Desk received about 76,000 requests for technological assistance. During that same period, the Help Desk received over 31,000 requests for waivers to enable contract guards to log into PTS. According to FPS officials, nearly half of Help Desk service requests involved failed wireless internet connections and personal identity verification (PIV) card issues, such as a damaged card, or the contract guard forgetting his or her card or personal identification number (PIN).

Tenant Agencies Lack Real-Time Information to Offset Guard Shortages

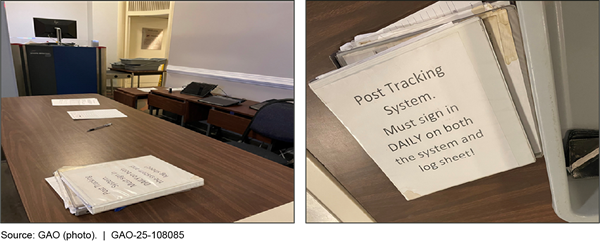

Tenant agency officials with FPS contract guards protecting their facilities said real-time information, as envisioned in PTS, could help FPS, security guard contractors, and tenant agencies learn about, and respond to, guard shortages. FPS noted in its PTS Concept of Operations that while tenant agencies were not direct users of the PTS system, they would benefit from the improved level of service enabled by PTS, such as real-time information on contract guards that serve at federal facilities. However, FPS continues to rely on an antiquated, paper-based guard tracking process that has adversely affected communication with tenants on guard shortages (see fig. 3).

Figure 3: Instructions for Guards at a Federal Building to Use the Paper Log Sheet and the Post Tracking System

Officials from the IRS and SSA—tenants at facilities guarded by FPS contract guards—described the problems that have occurred when there has been insufficient communication that qualified guards are not available.

· IRS managers said they do not receive timely communication about how guard shortages affect their facilities, often learning weeks later that posts were not staffed from the local IRS agency officials affected by the shortage. IRS officials said these guard shortages have caused security vulnerabilities, employee delays, and increased traffic at open entrances due to closed entrances. Since fiscal year 2022, IRS officials reported they closed 30 Taxpayer Assistance Centers for a full day because of the lack of contract guards. According to IRS officials, at some locations, unstaffed guard posts exceeded 50 percent of the necessary staffing levels, resulting in service disruptions, and exposing those IRS locations to increased risk.

· SSA officials also said FPS has been unable to provide a sufficient number of contract guards in the last 3 fiscal years, resulting in 510 instances of offices that were closed for several hours or a full day.[33] Consequently, contract guard shortages negatively affected the agency’s ability to serve the public, specifically vulnerable populations that needed assistance.

FPS officials noted that guard shortages would still have occurred and that various factors cause open posts including the security guard contractor’s ability to recruit, train, and retain qualified guards.[34] Furthermore, FPS officials noted that local tenant agency officials who do not have direct access to PTS, may learn about an open post before FPS officials because they are physically located at the federal facility. However, IRS and SSA officials said that real-time notification of guard shortages, like that promised by the Post Tracking System, could have allowed them to better react to the guard shortages.

It is critical that tenants such as IRS and SSA receive real-time information on guard shortages consistent with the PTS requirement. Without such information, IRS and SSA offices will likely remain unaware of guard shortages that could lead to facility closures. However, it is unknown when the PTS real-time information requirement will be met, given that the system schedule is no longer updated.

PTS Is Not Interoperable with Feeder Systems, Causing Extra Work and Data Challenges

PTS was expected to receive automated information from other FPS databases and not rely on manual uploads leading to challenges in data reliability. However, an FPS official said PTS is not interoperable with those other systems, requiring FPS staff to manually transfer the data. Several regional FPS officials and security guard contractors said this effort causes delays, extra administrative work, and data reliability issues. Furthermore, officials noted that because PTS relies on manually uploading data, PTS is not operating with the real-time data needed to fulfill PTS’s core mission of validating that contract guards are qualified to stand post in real time.

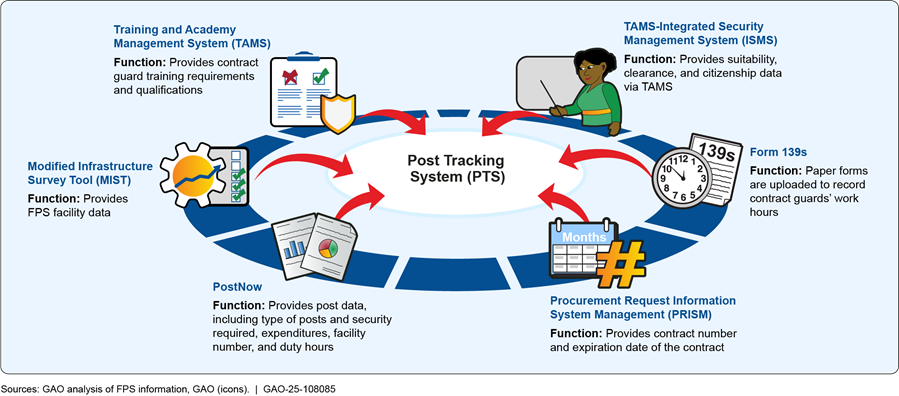

According to the PTS Manual, the system is intended to be populated from six data sources with information on guard training, security clearances, facilities, post responsibilities from contracts, and contractor information.[35] Figure 4 depicts the six data sources that should feed into PTS.

Figure 4: Federal Protective Service (FPS) Systems Provide Manually Uploaded Information to the Post Tracking System

Note: Data are updated and manually uploaded to PTS on a monthly or weekly basis. PTS is primarily used by FPS officials and contract guards. However, systems that feed into PTS are primarily used by FPS officials. The Modified Infrastructure Survey Tool provides facility data for each building to identify personnel available at each post in case of a staffing issue. PostNow provides information on FPS contract guard posts, responsibilities, expenditures, and duty hours for scheduling contract guards. The Training and Academy Management System provides training and certification records to determine if each contract guard can stand post. The Procurement Request Information System Management provides information on contracts and when they expire to ensure contract guards are available to stand post. The Integrated Security Management System includes names and clearance levels of contract guards to ensure that they are assigned to the appropriate posts. Form 139 is a paper form that tracks guard hours and can be uploaded into PTS.

According to FPS officials, the manual transfer of data from other DHS information sources has caused data errors. For example, FPS must manually upload information into PTS from its PostNow system to indicate which posts need guard coverage and to outline the required guard qualifications for each post.[36] However, several FPS regional officials told us that, due to a lack of PostNow guidance or standards, the aggregated information causes errors once uploaded to PTS. FPS officials said these errors can incorrectly flag contract guards as not qualified to stand post. FPS officials must then correct this information, which is a time-consuming process. As a result of these data reliability issues, officials from FPS and contract guard companies said they do not use PTS data.

DHS Has Not Shown If or When PTS Will Fulfill Its Original Mission

Although it continues to experience a myriad of problems with PTS, FPS has not followed its guidance in the Systems Engineering Life Cycle Guidebook to evaluate and develop a plan to address PTS deficiencies and update its project timelines.[37] PTS is one more example in the federal government of a troubled IT investment that has not received needed management attention. After many years of reporting on frequent failures, cost overruns, and schedule slippages of federal IT investments, in February 2015 we added improving the management of IT acquisitions to our high-risk areas for the federal government.[38] We noted that federal IT projects have failed due, in part, to a lack of oversight and governance. We reported that executive-level governance and oversight across the government has often been ineffective, specifically from CIOs.

Without greater attention and analysis from the DHS CIO regarding whether to continue, modify, or terminate PTS, PTS could continue to increase in schedule and costs without improving security or guard oversight. If the CIO determines that PTS is still the best method for meeting its original mission of overseeing guard postings and qualifications in real time, then FPS still lacks a plan and timeline for addressing PTS’s deficiencies. If FPS continues to deploy PTS without a realistic timeline for correcting its deficiencies or identifying an alternative solution, security guard contractors will continue to spend money and effort doing extra work with no tangible security benefit.

Conclusions

Consistent with the rate of detection in FPS covert tests, contract guards who conduct security screenings did not detect prohibited items about half the time in our covert tests. Failure to keep prohibited items out of federal facilities can compromise the safety of the people who work in and visit them. FPS collects data about its covert tests but does not use the information to improve detection rates. This is due in part to the information (1) being reported inconsistently, (2) not identifying specific and actionable causes of guards failing to detect prohibited items, and (3) not resulting in appropriate guard training targeted at addressing cause. Collecting and analyzing better data on its covert tests and using what it learns could help FPS improve guard performance.

PTS is a troubled system that has not delivered on promised capabilities. It cannot yet fulfill its mission of remotely verifying in real time that all posts are staffed with qualified guards. As a result, the paper-based system that the Post Tracking System was designed to replace currently remains the system of record for FPS.

The lack of real-time information has adversely affected communication with tenants on guard shortages. Tenants have expressed frustration with the lack of timely communication on guard shortages, and that those shortages led to office closings and impaired service to the public. Without an assessment of PTS, FPS would continue to force guard contractors to deploy a flawed system. This would cause extra work for an already understaffed workforce without a tangible security benefit and leave tenants in the dark when guard shortages occur.

Recommendations for Executive Action:

We are making the following four recommendations:

The Director of FPS should develop standardized procedures and guidance to improve the quality and consistency of its covert testing data, which could include data quality checks, guidance for staff to improve the consistency and comparability of reporting, and a process for identifying and documenting a specific cause for each test failure. (Recommendation 1)

The Director of FPS should develop guidance to ensure that, when contract guards fail covert tests, security guard contractors consistently provide training or other corrective actions that address the identified cause for the failed covert test. (Recommendation 2)

The Director of FPS should develop and implement a process to regularly analyze covert testing information and use that analysis to inform actions that will improve contract guards’ detection capabilities. (Recommendation 3)

The DHS Chief Information Officer should determine whether to terminate and replace PTS, or make corrective actions to the existing system, including a schedule for providing tenants with timely communication of guard shortages. (Recommendation 4)

Agency Comments

We shared a draft of this report with FPS, the Department of the Treasury, GSA, and SSA. In its comments, reproduced in appendix I, DHS concurred with all four recommendations. DHS also provided technical comments, which we incorporated, as appropriate. The remaining agencies informed us that they had no comments.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees and the Secretary of Homeland Security. The report is also available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact David Marroni at (202) 512-2834 or MarroniD@gao.gov, or Howard Arp at (202) 512-6722 or ArpJ@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix II.

Howard Arp

Director, Forensic Audits and Investigative Service

David Marroni

Director, Physical Infrastructure

GAO Contact

David Marroni, (202) 512- 2834 or MarroniD@gao.gov, or Howard Arp, (202) 512-6722 or ArpJ@gao.gov.

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contacts named above, GAO staff who made key contributions to this report include Keith Cunningham (Assistant Director), Nelsie Alcoser (Analyst in Charge), Caroline Christopher, Brendan Culley, Peggie Garcia, Geoff Hamilton, Melissa Hart, Nicholas Lessard-Chaudoin, Shirley Hwang, Jodi Lewis, Mark MacPherson, Robyn McCullough, Sarai Ortiz, Patricia Powell, Kelly Rubin, Jeanne Sung, Kevin Walsh, Amelia Michelle Weathers, Malika Williams, and Angel Zollicoffer.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on Facebook, Flickr, X, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our RSS Feeds or Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7700

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, ClowersA@gao.gov, (202) 512-4400, U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7125, Washington, DC 20548

Public Affairs

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, KaczmarekS@gao.gov, (202) 512-4800, U.S.

Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7149

Washington, DC 20548

Strategic Planning and External Liaison

Stephen J. Sanford, Managing

Director, spel@gao.gov, (202) 512-4707

U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7814, Washington,

DC 20548

[1]FPS refers to contract guards as Protective Security Officers. For the purposes of this report, we call Protective Security Officers “contract guards.”

[2]The Managing Federal Real Property area was added to GAO’s High-Risk List in 2003 and remained on the most recent update to the High-Risk list in 2023. See GAO, High-Risk Series: An Update, GAO‑03‑119 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 1, 2003) and High-Risk Series: Efforts Made to Achieve Progress Need to Be Maintained and Expanded to Fully Address All Areas, GAO‑23‑106203 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 20, 2023).

[3]GAO, Homeland Security: Preliminary Results Show Federal Protective Service’s Ability to Protect Federal Facilities Is Hampered By Weaknesses in Its Contract Security Guard Program, GAO‑09‑859T (Washington, D.C.: July 8, 2009).

[4]GAO, Homeland Security: Federal Protective Service’s Contract Guard Program Requires More Oversight and Reassessment of Use of Contact Guards, GAO‑10‑341 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 13, 2010).

[5]GAO, Homeland Security: The Federal Protective Service Faces Several Challenges That Raise Concerns About Protection of Federal Facilities, GAO‑08‑914T (Washington, D.C.: Jun. 18, 2008); Federal Protective Service: Actions Needed to Assess Risk and Better Manage Contact Guards at Federal Facilities, GAO‑12‑739 (Washington, D.C.: Aug. 10, 2012); Federal Protective Service: More Collaboration on Hiring and Additional Performance Information Needed, GAO‑23‑105361 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 15, 2022); Federal Facilities: Continued Oversight of Security Recommendations Needed, GAO‑24‑107137 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 29, 2023).

[6]FPS defines a post as a defined security function (e.g., X-ray, magnetometer, Wand) for a guarded location.

[7]GAO, Federal Facility Security: Preliminary Results Show That Challenges Remain in Guard Performance and Oversight, GAO‑24‑107599 (Washington, D.C.: July 23, 2024).

[8]Prohibited items used in the covert tests met the specifications of prohibited items listed in the following federal standard, Interagency Security Committee, Items Prohibited in Federal Facilities, An Interagency Security Committee Standard (Washington, D.C.: 2022). In some cases, we conducted multiple tests at the same facility, which means that the number of tests is larger than the number of facilities tested. We conducted multiple tests in all high-risk facilities, and in one low-risk facility, to test the ability of contract guards to detect different types of prohibited items. We attempted to smuggle one type of prohibited item during each test.

[9]Interagency Security Committee, The Risk Management Process: An Interagency Security Committee Standard (Washington, D.C.: 2021). The Interagency Security Committee, housed within DHS’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, is responsible for developing federal security policies and standards to enhance the quality and effectiveness of security in and protection of civilian federal facilities. The Interagency Security Committee was established in 1995 under Executive Order 12977 to enhance the quality and effectiveness of security in and protection of federal facilities in the United States occupied by federal employees for nonmilitary activities. Executive Order 12977, Interagency Security Committee, 60 Fed. Reg. 54411 (Oct. 19, 1995), as amended by Executive Order 13286, Amendment of Executive Orders, and Other Actions, in Connection With the Transfer of Certain Functions to the Secretary of Homeland Security, 68 Fed. Reg. 10619 (Mar. 5, 2003). Executive Order 14111, Interagency Security Committee, issued in November 2023 supersedes Executive Order 12977. Executive Order 14111, 88 Fed. Reg. 83809 (Nov. 27, 2023).

[10]Since 2019, FPS has used a database within its Law Enforcement Information Management System to capture the outcomes of FPS’s covert security tests.

[11]Federal Protective Service, Post Tracking System Life Cycle Cost Estimate, (Washington, D.C.: Mar.16, 2016); FPS Concept of Operations, (Washington, D.C.: May.17, 2016); Operational Requirements Document for the Post Tracking System, (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 20, 2019). Post Tracking System Integrated Master Schedule, (Washington, D.C.); and Operational Requirements Assessment (Washington, D.C.: April 22, 2022).

[12]FPS is funded through fees it charges agencies for its services and does not receive a direct appropriation from the general fund of the Department of the Treasury.

[13]FPS charges federal agencies additional fees for agency and building specific services, such as countermeasures, contract guards, and security patrol services.

[14]Business operation managers provide oversight and monitoring of programs in FPS regions, including budget, financial planning, revenue management, and acquisition.

[15]Interagency Security Committee, The Risk Management Process: An Interagency Security Committee Standard.

[16]Contract guards’ responsibilities include screening at access points to prevent the entry of prohibited items, such as weapons and explosives.

[18]Department of Homeland Security, Post Tracking System (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 14, 2014).

[19]The PTS Concept of Operations document also listed PTS mission functions that are essential to managing contract guards including (1) remotely monitoring FPS guard posts in real-time versus relying on paper forms, (2) issuing proper alerts and notifications to FPS management regarding contract guard staffing; (3) automatically gathering and storing data needed to validate contract invoices; (4) streamlining FPS’ oversight efforts, such as improving staffing and invoicing and reducing the administrative burden on FPS inspectors; (5) responding to data calls; and (6) providing management reports and analyzing performance.

[20]Prohibited items used in the covert tests met the specifications of prohibited items listed in the following federal standard, Interagency Security Committee, Items Prohibited in Federal Facilities, An Interagency Security Committee Standard. We packed each prohibited item in a backpack, along with other items that are typically carried in backpacks, such as loose clothing, an umbrella, a towel, a notepad, and pens.

[21]In 2009, FPS launched an internal covert testing program in response to substantial security vulnerabilities that we identified when we conducted covert tests. See GAO‑10‑341 and GAO‑09‑859T.

[22]FPS conducts several types of covert tests, but we focused our analysis on those in which FPS attempts to smuggle prohibited items into federal facilities. In addition, as described earlier, we excluded 41 records from our analysis because of issues with the quality and accuracy of the information in those records.

[23]See FPS Prohibited Items Program Directive 15.9.3.1; and Interagency Security Committee, Items Prohibited in Federal Facilities.

[24]GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO‑14‑704G (Washington, D.C.: September 2014).

[26]GAO‑14‑704G; GAO, Human Capital: A Guide for Assessing Strategic Training and Development Efforts in the Federal Government, GAO‑04‑546G (Washington, D.C.: March 2004).

[27]GAO, Evidence-Based Policymaking: Practices to Help Manage and Assess the Results of Federal Efforts, GAO‑23‑105460 (Washington, D.C.: July 12, 2023).

[28]A life cycle cost estimate provides a structured accounting of all labor, material, and other efforts required to develop, produce, operate and maintain, and dispose of a program. The development of a life cycle cost estimate entails identifying and estimating all cost elements that pertain to the program, from initial concept all the way through each phase in the program’s duration. The program life cycle cost estimate encompasses all past (or sunk), present, and future costs for every aspect of the program, regardless of funding source.

[29]Department of Homeland Security, Component Acquisition Executive Action Memorandum for Remediating the Post Tracking System (Washington, D.C.: May 22, 2018).

[30]Federal Protective Service, Post Tracking System Integrated Master Schedule, (Washington, D.C.).

[31]The operational assessment was performed by testing 1,487 tasks, which included duplicative counts where a task was required for multiple test cases. The entire test case was logged as “failed” if one or more of the tasks failed.

[32]Federal Protective Service, Federal Protective Service Post Tracking System, Protective Security Officer Vendor Guide, Version 3.0 (Washington, D.C.: May 4, 2022).

[33]SSA officials estimated that in the last 3 years, there were approximately 15,000 hours that posts were unguarded by FPS contract guards.

[34]FPS officials said that open posts account for less than one percent of all contracted post hours.

[35]The six data sources include five systems: the Training and Academy Management System, Integrated Security Management System, Modified Infrastructure Survey, PostNow, and the Procurement Request Information System Management. In previous PTS manuals, PostNow was referred to as PostX. The sixth data source is the Form 139, which is a paper form to document contract guards’ work hours. Federal Protective Service. Federal Protective Service Post Tracking System, User Manual for Administrator Contracting Officer Representatives (COR), Version 3.5. (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 28, 2023).

[36]PostNow is a system that provides information on FPS contract guard posts, responsibilities, type of security required, expenditures, facility number, and duty hours. It was initially developed as a database built from a spreadsheet to track expenses by post and was not intended to be used for other FPS databases.

[37]Department of Homeland Security Office of Program Accountability and Risk Management, Systems Engineering Life Cycle Guidebook, (Washington, D.C., May 2021).