DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY

Key Areas for DHS Action and Congressional Oversight

Statement of Chris Currie, Director, Homeland Security and Justice

Before the Subcommittee on Oversight, Investigations, and Accountability, Committee on Homeland Security, U.S. House of Representatives

For Release on Delivery Expected at 2 p.m. ET

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights

For more information, contact Chris Currie at (404) 679-1875 or CurrieC@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-108165, a testimony before the Subcommittee on Oversight, Investigations, and Accountability, Committee on Homeland Security, House of Representatives

Department of Homeland Security

Key Areas for DHS Action and Congressional Oversight

Why GAO Did This Study

DHS has a pivotal role in securing the border, strengthening cybersecurity, and preventing violent acts of domestic extremism, among other roles. DHS has an annual discretionary budget of about $60 billion, plus additional funding for disaster assistance. Oversight remains critically important to ensure effectiveness and efficiency.

GAO has designated two DHS areas to its High-Risk List: Improving the Delivery of Federal Disaster Assistance (2025) and Strengthening DHS IT and Financial Management Functions (2003).

This statement discusses GAO’s highest priority recommendations for DHS and areas on GAO’s High-Risk List, among other things.

This statement is based on products GAO issued from May 2024 to February 2025. For this work, GAO analyzed DHS strategies and other documents related to the department’s efforts to address its high-risk areas and interviewed DHS officials, among other actions.

What GAO Recommends

As of March 2025, GAO has 459 recommendations to DHS that remain open. These recommendations are designed to address the various challenges discussed in this statement. DHS has taken steps to address some of these recommendations. GAO will continue to monitor DHS’s efforts to determine if they fully address the challenges GAO has identified.

What GAO Found

GAO has issued numerous reports with thousands of recommendations to the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) over the department’s history. DHS has yet to fully address many recommendations that would help ensure effectiveness and efficiency, including dozens of the highest priority recommendations. For example, implementing GAO’s priority recommendations could help DHS address the increasing risk of catastrophic cyber incidents for U.S. critical infrastructure, better allocate billions of dollars used to procure goods and services, and build effective policy to address violent extremism. DHS's continued attention could lead to significant improvements in government operations.

In addition, GAO is tracking two DHS high-risk areas:

· Improving the delivery of federal disaster assistance. Natural disasters have become costlier and more frequent (see figure). In the last 10 years, appropriations for disaster assistance, including to DHS, totaled at least $448 billion, plus an additional $110 billion in supplemental appropriations so far in fiscal year 2025. Recent disasters such as Hurricanes Helene and Milton and wildfires in California have demonstrated the need for government-wide action to deliver assistance efficiently and effectively and reduce its fiscal exposure. In particular, attention is needed to improve processes for assisting survivors, invest in resilience, and strengthen the disaster workforce and capacity.

Debris from Damaged Homes Following Hurricanes Helene and Milton, 2024, Florida

· Strengthening DHS IT and financial management functions. DHS manages an annual discretionary budget of about $60 billion, but it has faced difficulties with IT and financial management. More work remains for DHS to (1) strengthen its information security program, and (2) modernize its components’ financial management systems and business processes. These security and modernization efforts are critical given the significant amount of money DHS manages for disasters as well as its sizable annual budget.

Chairman Brecheen, Ranking Member Thanedar, and Members of the Subcommittee:

I am pleased to be here today to discuss key oversight areas for the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). Over 20 years ago, the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks led to profound changes in government agendas, policies, and structures to confront homeland security threats facing the nation. Most notably, DHS began operations in 2003 with key missions that included preventing terrorist attacks from occurring in the U.S., reducing the country’s vulnerability to terrorism, and responding to and minimizing the damages from any attacks and natural disasters that may occur.

Given the constantly evolving threat landscape, DHS’s expansive missions, and its annual discretionary budget of about $60 billion, oversight remains critically important to ensure effectiveness and efficiency. Over the department’s history, we have issued numerous reports with thousands of recommendations to DHS. In addition to our individual reports, we periodically highlight pressing issues through our High-Risk List,[1] duplication and cost savings series,[2] and priority recommendations letters.[3]

DHS has challenges in several high-risk areas. In particular, in our most recent High-Risk update in February 2025, we designated Improving the Delivery of Federal Disaster Assistance as a new high-risk area. We added this area in recognition of the need for DHS to deliver assistance as efficiently and effectively as possible, address the fragmented federal approach to disaster recovery, and to and reduce fiscal exposures from the increased cost and frequency of disasters and the fragmented federal approach to disaster recovery. Additionally, Strengthening DHS IT and Financial Management Functions is a long-standing high-risk area with challenges that have persisted since the beginnings of the department in 2003.

Our recommendations to DHS can assist Congress in identifying key areas for oversight that could result in significant improvements and benefits. In particular, DHS has not yet fully addressed 36 recommendations that could better address fragmentation, duplication, and overlap. Further, we have also made additional priority recommendations that could significantly improve the efficiency of DHS operations.

My statement today is based on our prior work identifying these key areas for DHS oversight. For example, this statement includes information on our priority recommendations to DHS; our fragmentation, overlap, and duplication series; and our high-risk series, including our most recent High-Risk update in February 2025.

For this work, we analyzed DHS strategies and other documents related to the department’s efforts to address its high-risk areas and interviewed DHS officials, among other actions. In addition, to perform our prior work, we reviewed and analyzed federal law, agency guidance, and other agency documentation. More detailed information on the scope and methodology of our prior work can be found within each of the issued reports cited throughout this statement.

We conducted the work on which this statement is based in accordance with all sections of our Quality Assurance Framework that are relevant to our objectives. The framework requires that we plan and perform the engagement to obtain sufficient and appropriate evidence to meet our stated objectives and to discuss any limitations in our work. We believe that the information and data obtained, and the analysis conducted, provide a reasonable basis for any findings and conclusions in this product.

Priority Recommendations to DHS

As of March 2025, there are 459 open GAO recommendations across DHS’s mission set that have not yet been fully addressed.[4] Fully implementing these open recommendations could significantly improve DHS operations. In addition, each year, GAO sends a letter to all federal agencies identifying those recommendations that we deem as highest priority. In our 2024 DHS priority recommendations letter, we highlighted 37 priority recommendations.[5] DHS has since implemented five of these recommendations.

In general, our priority recommendations to DHS relate to emergency preparedness and response; border security and immigration; countering violent extremism and domestic terrorism; domestic intelligence and information sharing; information technology and cybersecurity; and infrastructure, acquisition, and management. DHS’s continued attention to these issues could lead to significant improvements in government operations. For example:

· Cybersecurity. In June 2022, we recommended that the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency work with the Federal Insurance Office to produce a joint assessment for Congress on the extent to which the risks to the nation’s critical infrastructure from catastrophic cyberattacks—and the potential financial exposures resulting from these risks—warrant a federal insurance response.[6] As of March 2024, DHS had collaborated with the Department of the Treasury on identifying data needs for the agencies’ joint assessment of the need for a federal insurance response to address catastrophic cyberattacks and plans to continue collaborating on a joint cyber insurance assessment. We will continue to monitor DHS’s progress. An assessment with DHS’s analysis of the cyber risks facing critical infrastructure could inform Congress in its deliberations related to addressing the increasing risk of catastrophic cyber incidents for U.S. critical infrastructure.

· Procurement management. In July 2021, we recommended that DHS ensure its Chief Procurement Officer uses a balanced set of performance metrics to manage the department’s 10 procurement organizations, including outcome-oriented metrics to measure (a) cost savings/avoidance, (b) timeliness of deliveries, (c) quality of deliverables, and (d) end-user satisfaction.[7] In February 2024, DHS showed that in fiscal year 2023, the department used category management activities for about 80 percent of its common goods and services expenditures ($18 billion of $22.5 billion) and had tracked savings of $502 million.[8] We will continue to monitor DHS’s progress. Using a balanced set of performance metrics would help DHS better identify improvement opportunities, set priorities, and allocate resources.

· Targeted violence. In July 2021, we recommended that DHS, in consultation with affected offices and components, establish common terminology for targeted violence.[9] As of February 2025, DHS officials stated that the draft terminology was still under review and anticipated that the definition would be finalized and published by September 2025. Without a common definition for targeted violence, it will be difficult for DHS to assess threats, track trends, and build effective policy within DHS and the stakeholder community. We will continue to monitor DHS’s progress.

· Southwest border security. In February 2020, we recommended that DHS, together with the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), collaborate to address information sharing gaps to ensure that HHS’s Office of Refugee Resettlement receives information needed to make decisions for unaccompanied alien children, including those apprehended with an adult.[10] In fall 2023, DHS and HHS reported that they were working on a new interagency agreement to govern information sharing. As of February 2025, DHS and HHS have not finalized the new agreement, but DHS officials stated they expect to finalize it in spring 2025. We will continue to monitor DHS’s progress. Finalizing an information sharing agreement that addresses information sharing gaps we identified would enable HHS to make more informed and timely decisions for unaccompanied children.

· Secret Service training. In May 2019, we recommended that the U.S. Secret Service develop and implement a plan to ensure that special agents assigned to Presidential Protective Division and Vice Presidential Protective Division reach annual training targets given current and planned staffing levels.[11] In February 2025, Secret Service officials told us—due to events involving the Secret Service during the 2024 Presidential Campaign and recently enacted legislation—they are revising training targets and staffing levels. We will continue to monitor the Secret Service’s progress. Developing and implementing a plan for meeting protection-related training targets would better prepare special agents to effectively respond to the security threats faced by the President and other protectees.

Opportunities to Address Fragmentation, Overlap, and Duplication and Achieve Financial Benefits

Since 2011, we have made dozens of recommendations to DHS that address duplication, overlap, and fragmentation, which could save taxpayers millions of dollars.[12] DHS has implemented some of these recommendations and has realized significant benefits. As of July 2024, we had identified 83 instances of financial benefits totaling $19.5 billion as a result of implementing our recommendations where DHS was a contributing agency.[13] For example, in response to our 2017 recommendations that the Coast Guard address 18 unnecessarily duplicative boat stations, which, if permanently closed, would reduce costs by $290 million over 20 years. DHS has directed the consolidation of five stations and saved about $10 million as of February 2025.[14] Additional boat stations may be considered for closure in the future, which could result in additional cost savings.

As of May 2024, DHS had not yet fully implemented 36 of our recommendations aimed at addressing fragmentation, overlap, and duplication or achieving financial benefits.[15] For example:

· Critical infrastructure protection. In March 2024, we recommended that DHS’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency implement guidance to better manage fragmentation and improve its interagency collaboration efforts aimed at addressing risks to operational technology used in operating critical infrastructure, such as oil and gas distribution.[16] DHS concurred with this recommendation. DHS has taken some steps to address this recommendation but has not completed its efforts to determine how its products and services are performing to make improvements to such products and services.

· Coast Guard housing. In February 2024, we recommended that the Coast Guard assess the potential benefits of certain housing authorities and develop a legislative proposal, if appropriate, to better manage its housing program costs.[17] As of fiscal year 2023, for example, the Coast Guard was managing about $4.6 billion in government-owned housing and 37 percent of these assets were beyond their service life. DHS concurred with this recommendation. The Coast Guard has taken some actions to address this recommendation and anticipates completing its assessment in June 2025.

· Countering domestic terrorism. In February 2023, we recommended that the DHS Under Secretary for Intelligence and Analysis, in collaboration with the Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, assess existing formal agreements to determine if they fully articulate a joint process for working together to counter domestic terrorism threats and sharing relevant domestic terrorism-related information and update and revise accordingly.[18] DHS concurred with this recommendation. As of February 2025, DHS has taken some steps to implement this recommendation by reviewing its formal agreements with the Federal Bureau of Investigation and reaching one new agreement to assign a Federal Bureau of Investigation staff member to a DHS counterterrorism office to better facilitate information sharing.

In addition to recommendations to DHS, we have also identified matters for congressional consideration that could help address fragmentation, overlap, or duplication or realize financial benefits.[19] For example:

· Disaster recovery. Congress should consider establishing an independent commission to recommend reforms to the federal government’s approach to disaster recovery.[20] In January 2025, a bill was introduced in the U.S. Senate that would establish a Commission on Federal Natural Disaster Resilience and Recovery to examine and recommend reforms to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the federal government’s approach to natural disaster resilience and recovery, and for other purposes. We will continue to monitor the progress of this bill.

· Interagency communication. Congress may wish to consider requiring the Departments of Justice, Homeland Security, and Treasury to collaborate on the development and implementation of a joint radio communications solution.[21] As of February 3, 2025, there has been no legislative action taken that would require these departments to (1) collaborate on the development and implementation of an interoperable radio communications solution or (2) commit to using the nationwide public safety broadband network to fully support their mission-critical voice operations.

We continue to monitor DHS and congressional actions and will provide updated information in our annual report in spring 2025.[22]

High-Risk Area: Improving the Delivery of Federal Disaster Assistance

In February 2025, we added Improving the Delivery of Federal Disaster Assistance to our High-Risk List. Given the rise in the number and cost of disasters and increasing programmatic challenges related to the delivery of federal disaster assistance identified in our work, disaster assistance merited a high-risk designation.[23] In 2018, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration calculated that the U.S. experienced 14 disasters that each cost more than $1 billion in total economic damages. By 2024, the number of disasters costing at least $1 billion almost doubled to 27. That same year at least 568 people died, directly or indirectly, as a result of those disasters. In addition to natural disasters, the COVID-19 pandemic—which was a federally declared disaster—tested federal agencies’ capacity to mount an effective and equitable nationwide response.

Recent disasters demonstrate the need for the federal government to take government-wide action to deliver assistance efficiently and effectively and reduce its fiscal exposure.

· Hurricanes Helene and Milton occurred within 2 weeks of one another in 2024 and affected some of the same areas in the Southeast (see fig. 1). These two disasters resulted in over 200 deaths and are expected to cost over $50 billion, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

· On January 8, 2025, the President approved a major disaster declaration for historic wildfires in Los Angeles County, California. The wildfires were unprecedented in their size, scope, and the damage they caused. The Palisades and Eaton fires resulted in 29 deaths and the expected financial cost is still unknown as of March 2025.

Figure 1: Debris from Damaged Homes Following Hurricanes Helene and Milton, 2024, Florida

Disaster assistance includes providing support to communities and survivors for response to, recovery from, and resilience to man-made and natural disasters. For fiscal years 2015 through 2024, appropriations for disaster assistance totaled at least $448 billion.[24] In total, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) provided assistance to over two million households for federal disaster assistance in 2024.

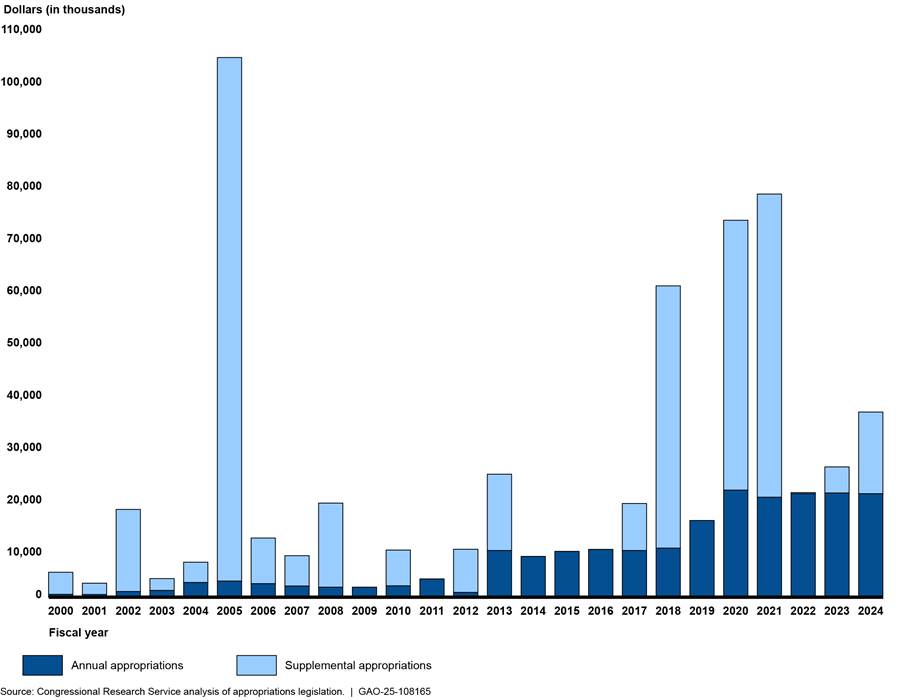

The Disaster Relief Fund, administered by FEMA, pays for several key disaster response, recovery, and mitigation programs that assist communities impacted by federally declared emergencies and major disasters.[25] Annual appropriations to this fund have varied but generally increased from fiscal year 2000 to fiscal year 2024, as shown in figure 2.

Figure 2: Disaster Relief Fund Appropriations in Fiscal Year 2023 Dollars, Fiscal Year 2000 to Fiscal Year 2024

Note: Fiscal year 2013 numbers do not reflect the impact of sequestration. Supplemental data include contingent appropriations and all appropriations under the heading of “Disaster Relief” or “Disaster Relief Fund” including the language “for an additional amount.” Appropriations do not account for transfers and rescissions. Deflator used was drawn from the FY2024 Budget of the United States Government, “Historical Tables: Table 1.3—Summary of Receipts, Outlays, and Surpluses or Deficits (—) in Current Dollars, Constant (FY2012) Dollars, and as Percentages of GDP: 1940—2028.”

There are about 60 open recommendations related to this new high-risk area, as of March 2025. In addition, there are four matters for congressional consideration to help address the nation’s delivery of disaster assistance.

FEMA and other federal entities—including Congress—need to address the nation’s fragmented federal approach to disaster recovery. Attention is also needed to strengthen FEMA’s disaster workforce and capacity and invest in resilience.

· Reducing Fragmentation of the Federal Approach to Disaster Assistance. The federal approach to disaster recovery is fragmented across more than 30 federal entities, making it harder for survivors and communities to successfully navigate the disaster assistance process. The federal entities involved have multiple programs and authorities that have differing requirements and timeframes. Moreover, data sharing across entities is limited.

As administrator of several disaster recovery programs, FEMA should also take steps to better manage fragmentation across its own programs, as we recommended.[26] Such actions could make the programs simpler, more accessible and user-friendly, and improve the effectiveness of federal disaster recovery efforts.

Reforming the federal government’s approach to disaster recovery and reducing fragmentation could improve service delivery to disaster survivors and communities and improve the effectiveness of recovery efforts. In response to our recommendations, as of February 2024, FEMA had taken steps to streamline the applications for two of its recovery programs.[27] However, FEMA will need to demonstrate that it has thoroughly considered available options to (1) better manage fragmentation across its own programs, (2) identify which changes FEMA intends to implement to its recovery programs, and (3) take steps to fully implement this recommendation.

· Strengthening FEMA’s Disaster Workforce. FEMA’s staffing levels and workforce challenges have limited its capacity to provide effective disaster assistance. In recent years, the increasing frequency and costs of disasters, the COVID-19 pandemic, and other responsibilities have placed additional pressures on FEMA.

In January 2022, we reported that FEMA has faced challenges with deploying staff with the right qualifications and skills to meet disaster needs.[28] We recommended that FEMA develop a plan to address challenges in providing quality information to field leaders about staff qualifications. FEMA officials told us that the actions in the plan enhance reliability of FEMA workforce qualifications and increases field leadership accessibility of workforce information. Such actions could better enable the agency to use its disaster workforce flexibility as effectively as possible to meet mission needs in the field.

In May 2023, we reported that FEMA uses different processes under various statutory authorities to hire full-time employees and temporary reservists.[29] We found that FEMA had an overall staffing gap of approximately 35 percent across different positions at the beginning of fiscal year 2022. While the gaps varied across different positions, Public Assistance, Hazard Mitigation, and Logistics generally had lower percentages of staffing targets filled—between 44 and 60 percent at the beginning of fiscal year 2022. These positions serve important functions, including administering assistance to state and local governments, creating safer communities by managing risk reduction activities, and coordinating all aspects of resource planning and movement during a disaster.

FEMA only had 9 percent of its disaster-response workforce available for Hurricane Milton response as staff were deployed to other disasters such as Hurricane Helene in the southeast and flooding in Vermont.[30] In addition, FEMA only had 20 percent of its disaster-response workforce available for Los Angeles fire response.[31] We have made numerous recommendations to help FEMA better manage catastrophic or concurrent disasters.

· Investing in Resilience. Disaster resilience can reduce the need for more costly future recovery assistance. In our Disaster Resilience Framework, we reported that the reactive and fragmented federal approach to disaster risk reduction limits the federal government’s ability to facilitate significant reduction in the nation’s overall disaster risk.[32]

FEMA’s hazard mitigation assistance programs provide assistance for eligible long-term solutions that reduce the impact of future disasters, thereby increasing disaster resilience. However, we have reported that there are areas in which FEMA can improve its hazard mitigation assistance grant programs.

For example, the Safeguarding Tomorrow through Ongoing Risk Mitigation Act of 2021 authorized FEMA to award capitalization grants—seed funding—to help eligible states, territories, Tribes, and the District of Columbia establish revolving loan funds for mitigation assistance.[33] In response, FEMA established the Safeguarding Tomorrow Revolving Loan Fund grant program in 2022. In February 2025, we found that while FEMA has identified some tools to collect information on the Revolving Loan Fund program, FEMA does not have a process for systematically collecting and evaluating the information to assess program effectiveness across all phases of the program.[34] We recommended that FEMA document and implement a process to regularly assess program effectiveness using evidence-based decision-making practices to help instill confidence in program participants and better ensure the long-term sustainability and success of the program.

High-Risk Area: Strengthening DHS IT and Financial Management Functions

Shortly after DHS was formed, we designated Implementing and Transforming DHS as a high-risk area in January 2003 because it had to transform 22 agencies—several with major management challenges—into one department.[35] This high-risk area has evolved over time to reflect DHS’s progress and now focuses on Strengthening DHS IT and Financial Management Functions.

As we reported in our latest high-risk update, DHS has faced difficulties securing federal IT systems and information and continues to face significant challenges with its financial management systems, processes, controls, and reporting.[36] Among other things, DHS’s progress depends on addressing challenges identified by DHS’s Office of Inspector General (OIG) and its financial statement auditor.

· IT Management. DHS has made progress implementing recommendations from DHS’s OIG related to IT security weaknesses. However, more work remains for DHS to strengthen its information security program.

In fiscal year 2023, the DHS OIG reported six deficiencies in the information security program. For example, the OIG reported that not all vulnerabilities were promptly mitigated, nor did DHS create the plans of action and milestones for all information security weaknesses. These actions include enforcing requirements for components to obtain authority to operate, resolving critical and high-risk vulnerabilities, and applying sufficient resources to mitigate security weaknesses.

Further, in 2024, DHS’s financial statement auditor continued to designate deficiencies in IT controls and information systems as a material weakness for financial reporting purposes. These deficiencies included ineffective design and implementation of controls to address areas such as system changes and access controls at several DHS components. DHS has identified planned steps and projects to achieve an opinion on internal controls over financial reporting for 2 consecutive years with no material control weaknesses by November 2029.

Until DHS addresses these deficiencies, the data and systems will continue to remain at risk of disruption. Ineffective security controls to protect these systems and data could significantly affect a broad array of agency operations and assets.

· Financial Management. DHS has received an unmodified (clean) audit opinion on its consolidated financial statements for 12 consecutive years, from fiscal years 2013 through 2024. However, during those same 12 years, DHS did not receive a clean opinion on its internal controls over financial reporting because it did not design and fully implement control activities to provide reasonable assurance that its systems will reliably report financial information.

First, the financial statement auditor found that DHS did not design, implement, or effectively operate information technology general controls to help prevent unauthorized access to programs and data; document, authorize, or monitor system changes; and control access to systems that were commensurate with job responsibilities. Second, DHS did not effectively design, implement, or operate controls over the financial reporting process in the following areas: appropriate level of supervisory review of journal entries and preparation of disclosures; monitoring of automated and manual control environments, including service providers; and establishing an organizational structure and internal communication to plan and execute controls at the Coast Guard.

Much work also remains to modernize DHS components’ financial management systems and business processes. For example, FEMA currently uses six segregated systems for financial management and procurement. FEMA plans to include the functionality of these systems under one financial system modernization effort. This modernization effort is critical given the significant amount of money FEMA manages for disasters.

DHS’s financial statement auditor also continued to report that agency financial management systems did not comply with requirements of the Federal Financial Management Improvement Act of 1996.[37] Specifically, DHS does not comply with applicable federal accounting standards in certain instances, federal financial management system requirements, and the U.S. Standard General Ledger at the transaction level.[38] Without implementing modernized systems with fully effective controls that comply substantially with these requirements, DHS is at an increased risk of errors and inconsistent or incomplete financial information.

In conclusion, given the constantly evolving threat landscape, DHS’s expansive missions, and its annual discretionary budget of about $60 billion, oversight remains critically important to ensure effectiveness and efficiency. Our recommendations to DHS can assist Congress in identifying key areas for oversight that could result in significant improvements and benefits. We continue to monitor DHS and congressional actions.

Chairman Brecheen, Ranking Member Thanedar, and Members of the Subcommittee, this completes my prepared statement. I would be pleased to respond to any questions that you may have at this time.

GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments.

If you or your staff have any questions about this testimony, please contact Chris Currie, Director, Homeland Security & Justice at (404) 679-1875 or curriec@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this statement. GAO staff who made key contributions to this testimony are Alana Finley (Assistant Director), Kelsey M. Carpenter (Analyst-in-Charge), Eric Hauswirth, Tracey King, Heidi Nielson, Hadley Nobles, Kevin Reeves, and Janet Temko-Blinder.

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on Facebook, Flickr, X, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our RSS Feeds or Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7700

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, ClowersA@gao.gov, (202) 512-4400, U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7125, Washington, DC 20548

Public Affairs

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, KaczmarekS@gao.gov, (202) 512-4800, U.S.

Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7149

Washington, DC 20548

Strategic Planning and External Liaison

Stephen J. Sanford, Managing

Director, spel@gao.gov, (202) 512-4707

U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7814, Washington,

DC 20548

[1]At the beginning of each new Congress, we issue an update to our High-Risk series, which identifies government operations with serious vulnerabilities to fraud, waste, abuse, and mismanagement, or in need of transformation. See GAO, High-Risk Series: Heightened Attention Could Save Billions More and Improve Government Efficiency and Effectiveness, GAO‑25‑107743 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 25, 2025).

[2]Each year, we report on federal programs with fragmented, overlapping, or duplicative goals or actions, and we have suggested hundreds of ways to address those problems, reduce costs, or boost revenue. See GAO, 2024 Annual Report: Additional Opportunities to Reduce Fragmentation, Overlap, and Duplication and Achieve Billions of Dollars in Financial Benefits, GAO‑24‑106915 (Washington, D.C.: May 15, 2024). We plan to issue the next report in spring 2025.

[3]Each year, we send letters to the heads of key departments and agencies, urging them to focus on priority recommendations. We highlight these recommendations because, upon implementation, they may significantly improve government operations, for example, by realizing large dollar savings; eliminating mismanagement, fraud, and abuse; or making progress toward addressing a high-risk or duplication issue. See, for example, GAO, Priority Open Recommendations: Department of Homeland Security, GAO‑24‑107251 (Washington, D.C.: Aug. 19, 2024).

[4]In November 2024, we reported that, on a government-wide basis, 70 percent of our recommendations made 4 years ago were implemented. See GAO, Performance and Accountability Report, Fiscal Year 2024, GAO‑25‑900570 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 15, 2024). DHS’s recommendation implementation rate was 84 percent.

[5]GAO‑24‑107251. We plan to issue our next priority recommendations update in spring 2025.

[6]GAO, Cyber Insurance: Action Needed to Assess Potential Federal Response to Catastrophic Attacks, GAO‑22‑104256 (Washington, D.C.: June 21, 2022).

[7]GAO, Federal Contracting: Senior Leaders Should Use Leading Companies' Key Practices to Improve Performance, GAO‑21‑491 (Washington, D.C.: July 27, 2021).

[8]Category management is an acquisition approach intended to help the federal government better manage categories of spending for commonly purchased products and services.

[9]According to DHS’s Strategic Framework for Countering Terrorism and Targeted Violence and implementation plans, DHS generally uses the term targeted violence to refer to any incident of violence that implicates homeland security and/or DHS activities in which a known or knowable attacker selects a particular target prior to the violent attack. However, the strategy states that this use of the term is unduly broad, and it indicates that it does not help the agency or stakeholders have a common understanding of the threat posed by targeted violence. This contributed to our recommendation for establishing common terminology. See GAO, Countering Violent Extremism: DHS Can Further Enhance Its Strategic Planning and Data Governance Efforts, GAO‑21‑507 (Washington, D.C.: July 20, 2021).

[10]GAO, Southwest Border: Actions Needed to Improve DHS Processing of Families and Coordination between DHS and HHS, GAO‑20‑245 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 19, 2020).

[11]GAO, U.S. Secret Service: Further Actions Needed to Fully Address Protective Mission Panel Recommendations, GAO‑19‑415 (Washington, D.C.: May 22, 2019).

[13]This financial benefit amount reflects benefits from all contributing agencies to these accomplishments, and therefore exceeds benefits attributable to actions by DHS. See GAO, Open GAO Recommendations: Financial Benefits Could Be between $106 Billion and $208 Billion, GAO‑ 24‑107146 (Washington, D.C.: July 11, 2024).

[14]GAO, Coast Guard: Actions Needed to Close Stations Identified as Overlapping and Unnecessarily Duplicative, GAO‑18‑9 (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 26, 2017).

[16]GAO, Cybersecurity: Improvements Needed in Addressing Risks to Operational Technology, GAO‑24‑106576 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 7, 2024).

[17]GAO, Coast Guard: Better Feedback Collection and Information Could Enhance Housing Program, GAO‑24‑106388 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 5, 2024).

[18]GAO, Domestic Terrorism: Further Actions Needed to Strengthen FBI and DHS Collaboration to Counter Threats, GAO‑23‑104720 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 22, 2023).

[21]Specifically, Congress may wish to consider requiring the departments to (1) establish an effective governance structure that includes a formal process for making decisions and resolving disputes, (2) define and articulate a common outcome for this joint effort, and (3) develop a joint strategy for improving radio communications. See GAO, Radio Communications: Congressional Action Needed to Ensure Agencies Collaborate to Develop a Joint Solution, GAO‑09‑133 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 12, 2008). Legislation has been enacted to provide funding for, among other things, the development of a nationwide, interoperable broadband network that is aimed at improving interoperable radio communications among public safety officials. However, the use of the broadband network by public safety users is voluntary. In addition, as of January 2025, officials from the Departments of Justice, Homeland Security, and the Treasury stated that they currently do not expect to use the nationwide public safety broadband network to fully support their mission-critical voice operations. As a result, this legislation will not remedy these agencies' fragmented approaches to improving interoperable radio communications.

[22]In between annual updates, GAO’s Duplication and Cost Savings website is a publicly accessible resource that allows Congress, agencies, and the public to track the federal government’s progress in addressing the issues we have identified.

[24]This total includes $312 billion in selected supplemental appropriations to federal agencies for disaster assistance and approximately $136 billion in annual appropriations to the Disaster Relief Fund for fiscal years 2015 through 2024. It does not include other annual appropriations to federal agencies for disaster assistance. Of the supplemental appropriations, $97 billion was included in supplemental appropriations acts that were enacted primarily in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, in December 2024, the Disaster Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2025, appropriated $110 billion in supplemental appropriations for disaster assistance. Pub. L. No. 118-158, div. B, 138 Stat. 1722 (2024).

[25]Other federal agencies have specific authorities and resources outside of the Disaster Relief Fund to support certain disaster response and recovery efforts.

[26]GAO, Disaster Recovery: Actions Needed to Improve the Federal Approach, GAO‑23‑104956 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 15, 2022).

[28]GAO, FEMA Workforce: Long-Standing and New Challenges Could Affect Mission Success, GAO‑22‑105631 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 20, 2022).

[29]GAO, FEMA Disaster Workforce: Actions Needed to Improve Hiring Data and Address Staffing Gaps, GAO‑23‑105663 (Washington, D.C.: May 2, 2023).

[30]FEMA National Watch Center, National Situation Report (Oct. 8, 2024).

[31]FEMA, National Watch Center, Daily Operations Briefing (Jan. 8, 2025).

[32]GAO, Disaster Resilience Framework: Principles for Analyzing Federal Efforts to Facilitate and Promote Resilience to Natural Disasters, GAO‑20‑100SP (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 23, 2019).

[33]Pub. L. No. 116-284, 134 Stat. 4869 (2021) (codified at 42 U.S.C. § 5135).

[34]GAO, Disaster Resilience: FEMA Should Improve Guidance and Assessment of Its Revolving Loan Fund Program, GAO‑25‑107331 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 24, 2025).

[35]GAO, Major Management Challenges and Program Risks: Department of Homeland Security, GAO‑03‑102 (Washington, D.C.: January 2003).

[37]Pub. L. No. 104-208, tit, VII, 110 Stat. 3009, 3009-389 (1996).

[38]DHS Office of Inspector General, Independent Auditors’ Report on the Department of Homeland Security’s FYs 2024 and 2023 Consolidated Financial Statements and Internal Control over Financial Reporting, OIG-25-05 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 15, 2024).