PROGRAM INTEGRITY

Agencies and Congress Can Take Actions to Better Manage Improper Payments and Fraud Risks

Statement of Kristen Kociolek, Managing Director, Financial Management and Assurance

Before the Subcommittee on Government Operations, Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, House of Representatives

For Release on Delivery Expected at 10 a.m. ET

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact M. Hannah Padilla at (202) 512-5683 or padillah@gao.gov

or Seto J. Bagdoyan at (202) 512-6722 or bagdoyans@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-108172, a testimony before the Subcommittee on Government Operations, Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, House of Representatives

Agencies and Congress Can Take Actions to Better Manage Improper Payments and Fraud Risks

Why GAO Did This Study

Reducing improper payments—payments that should not have been made or that were made in an incorrect amount—and fraud—obtaining something of value through willful misrepresentation—is critical to safeguarding federal funds. Such actions would help achieve cost savings and improve the government’s fiscal position. These payment integrity issues also erode public trust in government and hinder agencies’ efforts to execute their missions and program objectives effectively and efficiently.

This testimony covers (1) estimates of government-wide improper payments and fraud and (2) steps federal agencies and Congress can take to manage improper payment and fraud risks.

This testimony is primarily based on GAO’s large body of work on improper payments and fraud. GAO reviewed additional information to summarize improper payment root cause data reported by agencies for fiscal year 2024. More detailed information on the scope and methodology of GAO’s prior work can be found within each specific report cited in this statement.

What GAO Recommends

GAO has made numerous recommendations to Congress and agencies to help reduce improper payments and fraud. In March 2022, GAO identified 10 actions that Congress could take to strengthen internal controls and financial and fraud risk management practices across the government. As of February 2025, these matters remain open.

What GAO Found

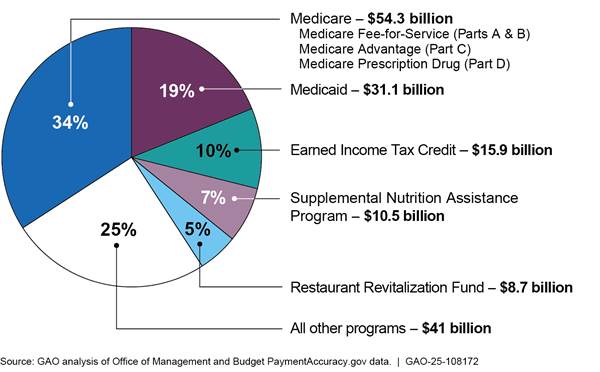

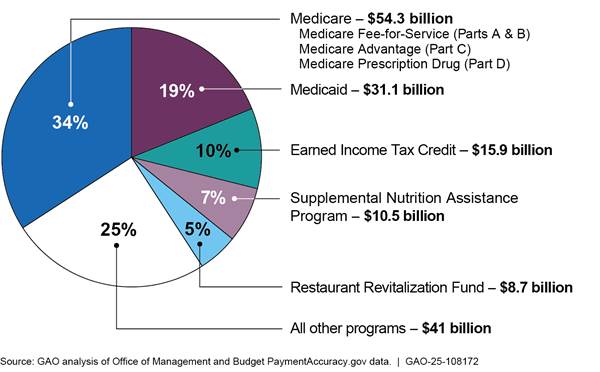

Improper payments and fraud are long-standing and significant problems in the federal government. Since fiscal year 2003, cumulative improper payment estimates by executive branch agencies have totaled about $2.8 trillion. In fiscal year 2024, federal agencies estimated $162 billion in improper payments, representing 68 programs, a small subset of all federal programs. The fiscal year 2024 estimate is a decrease of about $74 billion from the prior year. The reduction in estimated improper payments is largely attributable to the completion or winding down of certain COVID-19 programs. About 75 percent ($121 billion) of the government-wide total of estimated improper payments that agencies reported for fiscal year 2024 is concentrated in five program areas (see figure).

Programs Reporting the Largest Percentage of Government-Wide Improper Payment Estimates for Fiscal Year 2024

In April 2024, GAO estimated total direct annual financial losses to the government from fraud to be between $233 billion and $521 billion, based on fiscal year 2018 through 2022 data. GAO’s fraud estimate includes all federal programs and represents 3–7 percent of average annual obligations in this period. The range reflects the different risk environments during this period, which include normal operations, as well as emergency pandemic-relief programs and spending. The upper end of the range is associated with higher risk environments. The amount of estimated fraud loss underscores the importance of prevention and need for strategic fraud risks management.

GAO’s prior work has highlighted actions to help federal agencies better manage improper payment and fraud risks, including (1) focusing on prevention, (2) conducting regular risk assessment and root cause analysis, (3) establishing accountability, (4) sharing data and using technology, and (5) preparing for the next emergency. GAO also made recommendations to Congress to increase agencies’ accountability over improper payments and fraud.

Chairman Sessions, Ranking Member Mfume, and Members of the Subcommittee:

I am pleased to be here today to discuss opportunities for federal agency and congressional action to address improper payments and fraud risks. Improper payments—payments that should not have been made or that were made in an incorrect amount, whether due to fraud or error—have consistently been a government-wide issue.[1] Improper payments and fraud are two distinct concepts that are related but not interchangeable. While all fraudulent payments are considered improper, not all improper payments are due to fraud.[2] Fraud involves obtaining something of value through willful misrepresentation. Willful misrepresentation can be characterized by making materially false statements of fact based on actual knowledge, deliberate ignorance, or reckless disregard for falsity.

Reducing improper payments is critical to safeguarding federal funds and could help achieve cost savings and improve the government’s fiscal position. Since fiscal year 2003, cumulative improper payment estimates by executive branch agencies have totaled about $2.8 trillion, including $162 billion for fiscal year 2024. The actual amount of improper payments may be significantly higher. For example, we found that agencies failed to report estimates for nine programs susceptible to significant improper payments in fiscal year 2023.[3]

In April 2024, we estimated that the federal government lost between $233 billion and $521 billion annually from fraud, based on data from fiscal years 2018 through 2022.[4] Unlike improper payment estimates that are produced by a subset of agencies at the program level, our fraud estimate was based on data across the federal government. All federal programs and operations are at risk of fraud, which—in addition to financial payments—can involve federal activities that are nonfinancial in nature. For example, a fraudulently obtained passport can be used to conceal identity and potentially enable other crimes, such as money laundering.

As noted in the February 2025 update to GAO’s High-Risk List, reducing improper payments and fraud is critical to better managing the cost of government.[5] Areas on the High-Risk List include programs that represented over 66 percent of the total government-wide reported improper payment estimate for fiscal year 2024. These include two of the fastest-growing programs—Medicare and Medicaid—and the unemployment insurance system and the Earned Income Tax Credit. Several other programs are also on the High-Risk List due, in part, to challenges linked to improper payments or fraud risk management. These include the Small Business Administration’s (SBA) emergency loans for small businesses and Department of Defense financial management. Beyond financial impacts, these payment integrity issues erode public trust in government and hinder agencies’ efforts to execute their missions and achieve program objectives effectively and efficiently. This statement covers (1) estimates of government-wide improper payments and fraud, and (2) steps federal agencies and Congress can take to manage improper payment and fraud risks.

My remarks are primarily based on our large body of work examining improper payments and fraud in the federal government. We also reviewed information reported by agencies for fiscal year 2024 on the Office of Management and Budget’s PaymentAccuracy.gov website in order to summarize improper payment root cause data. More detailed information on the scope and methodology of our prior work can be found within each specific report.

We conducted the work on which this statement is based in accordance with generally accepted auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient and appropriate audit evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Improper Payments and Fraud Are Substantial and Pervasive Government-Wide Issues

Estimated Improper Payments

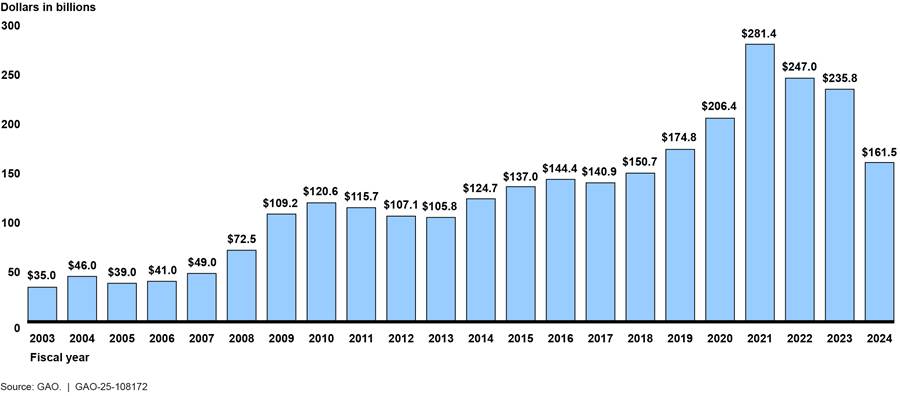

Since fiscal year 2003, cumulative improper payment estimates by executive agencies have totaled about $2.8 trillion. The actual amount of improper payments may be significantly higher. In fiscal year 2024, federal agencies’ estimates totaled about $162 billion in improper payments, a decrease of about $74 billion from the prior fiscal year (see fig. 1). The reduction in estimated improper payments is largely attributable to the completion or winding down of certain COVID-19 relief programs.

Figure 1: Total Reported Executive Agency Improper Payment Estimates, Fiscal Years 2003–2024

Note: Prior year improper payment estimates have not been adjusted for inflation. Improper payments are payments that should not have been made or that were made in an incorrect amount. Executive agency estimates of improper payments treat as improper any payments whose propriety cannot be determined due to lacking or insufficient documentation.

For fiscal year 2024, 16 agencies reported improper payment estimates across 68 programs, representing a small subset of all federal programs. As shown in figure 2, about 75 percent ($121 billion) of the fiscal year 2024 government-wide total of estimated improper payments was concentrated in five program areas:

· Department of Health and Humans Services’ (HHS) Medicare, ($54 billion);[6]

· HHS’s Medicaid ($31 billion);[7]

· Department of the Treasury’s Earned Income Tax Credit ($16 billion);

· Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program ($11 billion); and

· Small Business Administration’s (SBA) Restaurant Revitalization Fund ($9 billion).

Figure 2: Programs Reporting the Largest Percentage of Government-Wide Improper Payment Estimates for Fiscal Year 2024

Note: “All other programs” represents the remaining program for which executive agencies reported improper payment estimates, and not all federal programs. Executive agencies reported improper payment estimates for 68 programs for fiscal year 2024. Improper payment estimates displayed in the figure include both improper and unknown payments. Executive agency estimates of improper payments treat any payments whose propriety cannot be determined due to lacking or insufficient documentation as improper.

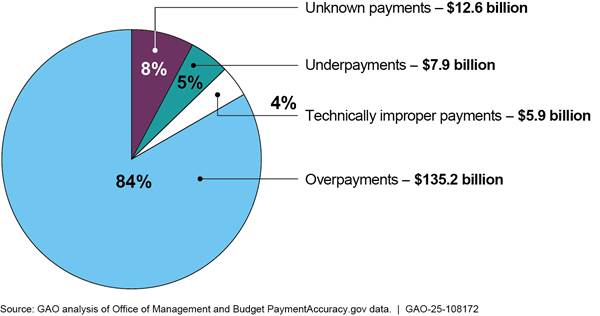

As shown in figure 3, most of the $162 billion in government-wide improper payment estimates for fiscal year 2024 consisted of overpayments. The remaining improper payments consisted of underpayments, unknown payments, and technically improper payments.[8]

Figure 3: Agencies’ Fiscal Year 2024 Reported Estimated Improper Payments by Type

Note: Percentages in the figure do not sum to 100 percent due to rounding.

The government-wide estimated total may not represent the full extent of improper payments. As has been true in prior fiscal years, the fiscal year 2024 improper payment estimates do not include certain programs that agencies have determined are susceptible to significant improper payments. For example, the $162 billion total does not include estimates for HHS’s Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program. HHS reported that it does not have the authority to obtain the information it needs to estimate or report improper payments for this program.[9] Various other programs did not report improper payment estimates for fiscal year 2024, such as the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) Office of Public and Indian Housing’s Tenant-Based Rental Assistance and the SBA’s Shuttered Venue Operators Grant program.[10]

For fiscal year 2023, agency inspectors general (IG) determined that 13 of the 24 Chief Financial Officers Act of 1990 (CFO Act) agencies fully complied with Payment Integrity Information Act of 2019 (PIIA) criteria and related Office of Management and Budget (OMB) guidance.[11] This includes publishing improper payment estimates, corrective action plans, and improper payment reduction targets for all risk-susceptible programs and activities, among other criteria and requirements. The primary drivers behind noncompliance in fiscal year 2023 were (1) high improper payment rate estimates (at least 10 percent), (2) unreliable estimates, and (3) inadequate risk assessments.

Estimated Government-Wide and Program Fraud Losses

Improper payment estimates represent a small subset of executive agencies’ programs, covering 68 programs in fiscal year 2024. In contrast, our estimate of financial losses due to fraud is based on data across the federal government. In April 2024, we estimated total direct annual financial losses to the government from fraud to be between $233 billion and $521 billion based on fiscal year 2018 through 2022 data.[12] Our fraud estimate includes all federal programs and represents 3–7 percent of average annual obligations in this time period. The range reflects the different risk environments during this period, which include normal operations, as well as emergency pandemic-relief programs and spending. The upper end of the range is associated with higher risk environments. For example, the public health crisis, economic instability, and increased flow of federal funds associated with the COVID-19 pandemic increased pressure on federal agency operations to spend federal funds quickly and presented opportunities for individuals and criminal organizations to commit fraud. The amount of estimated fraud loss underscores the importance of prevention and need for federal agencies to manage fraud risks strategically.

Fraud estimates can demonstrate the scope of the problem, improve oversight prioritization, and help determine the return on investment from fraud risk management activities. IGs and agency officials, however, noted challenges in producing fraud estimates. For example, limited fraud-related data and use of varying terms and definitions of fraud for recording data pose challenges. These data gaps and variability result in information that cannot be readily compared or consolidated to determine the extent of fraud across the federal government.

As a result, we recommended that OMB, in collaboration with the Council of the Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency, develop guidance on the collection of IG data to support fraud estimation. We also recommended that OMB, with input from agencies, develop guidance on the collection of agency data to support fraud estimation. OMB generally agreed with the recommendations. We have designated these recommendations as priority recommendations for OMB.[13]

We also recommended that Treasury, in consultation with OMB, establish an effort to evaluate and identify methods to expand government-wide fraud estimation to support fraud risk management. Treasury agreed with the recommendation.[14]

OMB told us that it has begun coordination to determine appropriate next steps regarding our recommendations. However, as February 2025, these recommendations remain open.

While our government-wide estimate cannot be used to estimate fraud losses at the program level, we and others have developed program-level estimates. For example, we developed an estimate of unemployment fraud in response to congressional interest in the extent of pandemic-related spending fraud. Specifically, we estimated that between $100 billion and $135 billion (between 11 and 15 percent of total spending) in fraudulent unemployment insurance payments were made between April 2020 and May 2023.[15]

SBA and its Office of Inspector General (OIG) estimated pandemic-related fraud. SBA estimated $36 billion of pandemic relief emergency program funds were likely obtained fraudulently from 2020 to 2022.[16] Using a different approach, the SBA OIG estimated that there were $200 billion in potentially fraudulent pandemic related business loans as of May 2023.[17]

Agencies and Congress Can Take Actions to Better Manage Improper Payments and Fraud Risks

Our prior work has highlighted actions that can help federal agencies to reduce improper payments and fraud. These actions relate to (1) focusing on prevention, (2) conducting regular risk assessment and root cause analysis, (3) establishing accountability, (4) sharing data and using technology, and (5) preparing for the next emergency. We have also made recommendations to Congress to increase agencies’ accountability over improper payments and fraud.

Agencies Can Do More to Address Improper Payments and Fraud Risks

Focusing on Prevention

Preventive controls offer the most cost-efficient use of resources and are generally effective at mitigating improper payment and fraud risks. The best way to reduce improper payments is to not make them. As their name implies, preventive controls are designed to stop payment errors and fraud before they occur. Preventive controls can also help agencies avoid reliance on the difficult and expensive “pay and chase” model, where efforts are made to identify and recover improper payments, including fraudulent payments, after they are made.

We have emphasized the importance of preventive controls in mitigating improper payments and fraud risk. In June 2024, we issued draft updates to our Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, which include an emphasis on prioritizing preventive control activities.[18]

Our Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs (Fraud Risk Framework) notes that a program’s antifraud strategy should focus on preventive control activities.[19] In addition, our Framework for Managing Improper Payments in Emergency Assistance Programs emphasizes the importance of prioritizing prepayment controls, an example of preventive controls, when designing and implementing control activities.[20]

When the quick disbursement of funds makes prepayment controls difficult to apply, it is important that agencies plan for expedited postpayment controls. Any reduction in prepayment controls to provide service and issue payments faster should be mitigated by strengthening postpayment controls, such as sampling payments to determine whether they were disbursed properly.[21]

In our prior reports, we have included descriptions of agencies’ use of prepayment controls in programs such as unemployment insurance and Medicare, as well as recommendations for improvement. For example:

· Unemployment insurance. We previously reported that the Department of Labor’s (DOL) Employment and Training Administration issued guidance to state workforce agencies on implementing prepayment controls for detecting fraudulent claims in August 2020.[22] This guidance included using the National Association of State Workforce Agencies’ Integrity Data Hub to identify claims using the Social Security numbers of deceased persons or federal prison inmates. Use of the Integrity Data Hub is optional. By December 2020, 32 of 54 state workforce agencies had used or partially used the Integrity Data Hub. As of 2024, all states and territories were participating in the Integrity Data Hub.[23]

The National Association of State Workforce Agencies estimated that use of the Integrity Data Hub during the COVID-19 pandemic helped to prevent more than $178 million in improper payments. However, in February 2021, the DOL OIG identified more than $5.4 billion in potentially fraudulent unemployment insurance payments made from March 2020 to October 2020, including benefits paid to individuals who used the Social Security numbers of deceased persons and federal inmates. The DOL IG recommended that the Employment and Training Administration work with Congress to establish legislation requiring state workforce agencies to cross-match data before issuing payments in four high-risk areas, including Social Security numbers of deceased individuals and federal prisoners. As of March 2025, no legislation has been introduced in the 119th Congress that would address the DOL IG’s recommendation.

· Medicare. In April 2016, we recommended that HHS’s Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) request legislative authority to allow recovery auditors to conduct prepayment claim reviews.[24] CMS conducted a demonstration from 2012 through 2014 that allowed recovery auditors to conduct prepayment claim reviews, and the agency considered the demonstration a success. HHS did not concur with our recommendation and has not taken any action to request such legislative authority. According to HHS, CMS has other program integrity activities to prevent improper payments. We maintain that prepayment claim reviews better protect agency funds compared with postpayment reviews and that allowing recovery auditors to conduct these reviews will help prevent improper payments.

· Treasury’s Do Not Pay system and other payment integrity tools. Federal agencies can leverage Treasury’s Do Not Pay system to conduct data matching in order to prevent payments to ineligible recipients. Treasury’s Office of Payment Integrity offers resources dedicated to preventing and detecting improper payments through a variety of data-matching and data-analytics services. Treasury’s fiscal year 2024 agency financial report notes that the department’s efforts combatting improper payments and fraud yielded over $4 billion in prevention and recovery, representing a seven-fold increase compared to fiscal year 2023 ($652 million). According to Treasury, this was accomplished through dedicated efforts to enhance fraud prevention capabilities and expand offerings to new and existing customers, such as Account Verification Service and access to the Social Security Administration’s full death master file through Do Not Pay.[25]

Conducting Regular Improper Payment and Fraud Risk Assessment and Root Cause Analysis

Conducting regular risk assessments can help program managers identify and respond to risks facing the entity, including fraud. While some programs may conduct statutorily required risk assessments, such as improper payment risk assessments, programs that do not meet the statutory threshold for improper payment risk assessments should still strategically manage their risks of improper payments.[26]

As discussed in our Fraud Risk Framework, conducting a fraud risk assessment is a leading practice in strategically managing fraud risks. Such assessments can, for example, help program officials determine whether certain controls are effectively designed and implemented to reduce the likelihood or impact of a fraud risk to a tolerable level. They also can help agencies prioritize risks and allocate resources.

Root causes are conditions, activities, and other factors that lead to improper payments—including those due to fraud—and that, if corrected, would prevent the improper payment from occurring. According to OMB guidance, identifying root causes of improper payments is critical to formulating effective corrective actions.[27] Understanding the root causes of improper payments will help agencies develop effective corresponding corrective actions. Identifying the root cause is an iterative process that can include assessing possible causes and prioritizing among them. Table 1 is an example of root cause analysis based on OMB guidance.

Table 1: Office of Management and Budget Example of Improper Payment Root Cause Analysis

|

Improper payment |

Why did this occur? |

Potential cause category |

Analysis |

Root cause |

Possible corrective actions |

|

A payment is improperly issued to a deceased individual. |

The agency has access to the data it needs to verify if an individual is deceased but did not check that information prior to payment. |

Failure to access data/information |

Why was the data/information not accessed? |

Lack of training or automation for checking whether the applicant is deceased |

Training on how to review information Automate the eligibility process to enable data access |

Source: GAO analysis of Office of Management and Budget Memorandum M-21-19 | GAO‑25‑108172

PIIA requires agencies to describe the causes of improper payments in programs for which they report estimates. OMB provides guidance for agencies to identify causes of improper payments using specified categories.[28] Table 2 summarizes agencies’ root cause reporting by OMB category for fiscal years 2021 through 2024.

Table 2: Improper Payment Root Cause Reporting Categories for Fiscal Years (FY) 2021 through 2024

|

Root cause reporting category |

Explanation |

Estimated amount (percentage of total) |

|||

|

FY 2021 |

FY 2022 |

FY 2023 |

FY 2024 |

||

|

Failure to access data/information needed |

Failure to access the appropriate information to determine whether a beneficiary or recipient should be receiving a payment, even though such information exists and is accessible to the agency or entity making the payment. For example, an agency with access to the Social Security Administration’s death master file fails to utilize it and improperly sends payment to a deceased individual. |

$187.9 billion (66.8 percent) |

$145.1 billion (58.8 percent) |

$147.9 billion (62.7 percent) |

$108.5 billion (67.1 percent) |

|

Inability to access the data/information |

A situation in which the data or information needed to validate payment accuracy exists but the agency or entity making the payment does not have access to it. For example, statutory constraints preventing an agency from being able to access recipients’ earning or work status through existing databases that would help prevent improper payments. |

$57.9 billion (20.6 percent) |

$35.9 billion (14.5 percent) |

$15.3 billion (6.5 percent) |

$14.2 billion (8.8 percent) |

|

Data/information needed does not exist |

A situation in which there is no known database, dataset, or location currently in existence that contains the data/information needed to validate the payment accuracy prior to making the payment. For example, an agency is unable to confirm that an individual receiving a benefit based on their health provided complete medical evidence because no database with that information exists. |

$25.2 billion (9.0 percent) |

$24.2 billion (9.8 percent) |

$23.3 billion (9.9 percent) |

$20.4 billion (12.6 percent) |

|

Unknown payment caused by insufficient or lack of documentation from applicants to determine eligibility |

An agency is unable to discern whether a payment was proper or improper because of insufficient or lack of documentation. For example, an agency conducting a periodic review to determine continued eligibility for a benefit does not have all the information in the beneficiary’s case file to confirm continued eligibility. |

$4.4 billion (1.6 percent) |

$32.7 billion (13.2 percent) |

$44.6 billion (18.9 percent) |

$12.6 billion (7.8 percent) |

|

Technically improper payments |

Recipients received the correct amount of funds they were due, but the payment failed to meet all regulatory or statutory requirements. |

$6.0 billion (2.1 percent) |

$9.0 billion (3.6 percent) |

$4.6 billion (1.9 percent) |

$5.9 billion (3.7 percent) |

|

Total |

|

$281.4 billion |

$247.0 billion |

$235.8 billion |

$161.5 billion |

Source: GAO analysis of relevant Office of Management and Budget guidance and Paymentaccuracy.gov data. | GAO‑25‑108712

Notes: Percentages may not sum to 100 percent and amounts may not sum to totals due to rounding. Root cause categories are defined by the Office of Management and Budget in guidance (M-21-19) provided to agencies on reporting improper payments.

Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs, and our prior reporting have identified opportunity, incentive, and rationalization as risk factors that can contribute to fraud in federal programs.[29] We have also reported that programs with weak internal controls can be more vulnerable to fraud and may lack the necessary safeguards to prevent, detect, and respond to fraud. In addition, we have previously reported on specific mechanisms that individuals can use to engage in fraudulent activities, such as misrepresentation, document falsification, social engineering, data breaches, cybercrime, and coercion.[30]

Our prior reports have identified issues tied to agency risk assessment and root causes of improper payments, including fraud, in SBA’s COVID-19 emergency loan programs and DOL’s unemployment insurance. For example:

· SBA emergency loan programs. Because SBA officials moved quickly to establish the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) and COVID-19 Economic Injury Disaster Loan (EIDL) program, they did not conduct formal fraud risk assessments for either pandemic-relief program before it was started. Consequently, we made two recommendations in March 2021 that SBA conduct a comprehensive fraud risk assessment for each program.[31] In response, SBA hired a contractor to conduct a fraud risk assessment for both PPP and COVID-19 EIDL in October 2021. The assessment found that SBA implemented additional fraud prevention controls over the course of the programs. These controls included cross-referencing applicant information with Treasury’s Do Not Pay system and introducing a set of automated screening rules. However, the assessment also noted that the programs continued to be susceptible to fraud risks that required enhancements to the current mitigation strategies.

· Unemployment insurance. In October 2021, we found fraudulent activities related to unemployment insurance programs that included individuals’ use of stolen or fake identity information or personally identifiable information to apply for and receive unemployment benefits.[32] DOL has noted that stolen personally identifiable information and program weaknesses have allowed criminals to defraud unemployment insurance programs. In December 2022, we recommended that DOL design and implement an antifraud strategy for unemployment insurance based on a fraud risk profile consistent with the Fraud Risk Framework’s leading practices. DOL has implemented the recommendation.

Establishing Accountability by Designating Responsible Officials

Agencies can establish accountability through mechanisms that hold an entity or person responsible, such as designating a senior agency official accountable for achieving objectives and establishing performance incentives or benchmarks.[33] Designating a senior official with overall responsibility for an area—such as payment integrity—helps establish accountability and endows that official with the authority to lead and make change.

Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government notes that management should establish an organizational structure, assign responsibility, and delegate authority to achieve the entity’s objectives. Federal program managers should ensure that sufficient resources are applied to oversee improper payment and fraud risk management activities, and that authority and responsibility for internal control are clearly assigned and periodically reviewed.

Clearly assigning roles and responsibilities for managing improper payments should also include establishing a dedicated antifraud entity to strategically manage fraud risks.[34] Having such an entity can help ensure that risks related to fraudulent activity are identified and assessed, and that appropriate controls are implemented when agencies distribute funding. This is particularly important when considering emergency or disaster relief programs. Such entities should have clearly defined and documented responsibilities and authority for managing fraud risks.

Our prior reports have highlighted instances where clearly assigned responsibility and use of program-level accountable officials were part of a successful strategy for reducing improper payments, including at HHS and the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). For example:

· HHS. CMS created the Center for Program Integrity, a centralized entity responsible for Medicare and Medicaid program integrity issues. After receiving additional funding, CMS allocated additional staff to the center, growing from 117 full-time equivalent positions in 2011 to about 492 in fiscal year 2021. CMS was able to establish working groups and interagency collaboration aimed at reducing improper payments. By assigning responsibility for payment integrity to this center, CMS was able to centralize the development and implementation of automated prepayment controls used to deny Medicare claims that should not be paid. As CMS has undertaken these efforts and others to address improper payments, it has seen a reduction in improper payments. Between fiscal years 2018 and 2020, Medicare’s fee-for-service and Medicare Advantage saw a reduction in their estimated improper payment rates of more than 1 percentage point, which is significant given that Medicare’s estimates accounted for over one-quarter of the total of agency-estimated improper payments government-wide in fiscal year 2019.[35]

· VA. In our June 2023 report on programs with reported reductions in improper payment estimates from fiscal year 2017 to fiscal year 2022, we described how VA established program-level senior accountable officials at the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) to increase accountability and involvement of program offices in reducing improper payments.[36] In addition, the VHA Associate Chief Financial Officer established compliance benchmarks for all VHA programs at high risk for improper payments and set goals for each senior accountable official to meet PIIA compliance by specified dates. VHA described holding quarterly meetings with senior accountable officials and monthly meetings with contacts from VHA’s regional health care networks to facilitate accountability and to share PIIA testing results. VHA credited these actions with helping to reduce estimated improper payments.

Sharing Data and Using Technology

There are a variety of ways agencies can use data and technology as part of a strategy to manage improper payment and fraud risks. As noted in the leading practices of the Fraud Risk Framework, implementing data analytics is part of an overall antifraud strategy. Data-analytics activities can include a variety of techniques. For example, data-mining and data-matching techniques can enable agencies to identify potential fraud or improper payments that have already been awarded, thus assisting agencies in recovering these dollars. Conversely, predictive analytics can identify potential fraud before making payments, and help enhance preventive controls. In particular, we have highlighted the importance of data matching and other techniques to verify self-reported information and other information necessary for determining eligibility for enrolling in programs or receiving benefits.

According to the Fraud Risk Framework, sharing data allows programs to compare information from different sources to help ensure that payments are appropriate before they are made. Using different data sources to confirm identity and eligibility information can be a key step in reducing improper payments.

Identifying data-sharing opportunities in advance can help agencies identify barriers to accessing data, such as statutory restrictions, and proactively work to resolve them before making payments, particularly for new or emergency programs. While the obligation to control and protect data can limit agencies’ ability and willingness to share information across the federal government, program managers may be able to identify authorities under which data sharing is permissible for the purpose of enhancing identity-verification controls. For example, the Privacy Act of 1974, as amended, defines a number of conditions under which federal agencies may share information with other government agencies without the affected individual’s consent.[37]

Our reports, as well as reports from other oversight entities, have highlighted instances where use of data or access to data could have improved agencies’ efforts to prevent and detect improper payments, including at the Department of Defense (DOD), HUD, and SBA. For example:

· DOD. In February 2024, we issued a report examining DOD’s fraud risk management strategy.[38] We found that, contrary to leading practices, DOD’s strategy did not establish data analytics as a method for fraud risk management. Data analytics can include a variety of techniques, such as data matching. Data matching can be used to verify key information to determine eligibility to receive federal contracts. For example, if an entity reports that it is a small business to receive federal contracts, DOD can use third-party data sources to verify that the entity actually meets requirements to qualify as a small business. We recommended that DOD revise its strategy to establish data analytics as a method for preventing, detecting, and responding to fraud. As of February 2025, this recommendation remained open.

· HUD. In August 2023, we issued a report focused on the potential for fraud in Community Development Block Grant Disaster Relief homeowner assistance programs.[39] We found that HUD did not require grantees and grant subrecipients to collect applicant data in a complete and consistent manner to support applicant eligibility determinations and fraud risk management. We reported that additional guidance from HUD on what data elements to collect could support grantees’ and subrecipients’ ability to identify contractors that are debarred, suspended, or excluded from receiving federal contracts. We recommended that HUD develop guidance for grantees and subrecipients on collecting complete and consistent data to better support applicant eligibility determinations and fraud risk management. We also recommended that HUD identify ways to collect and combine contractor and subcontractor data across grantees and subrecipients to facilitate risk analyses, such as by expanding the Disaster Recovery Data Portal, Disaster Recovery Grant Reporting System, or other appropriate systems. These recommendations remain open as of February 2025.

· SBA. In January 2023, the Pandemic Response Accountability Committee (PRAC) identified $5.4 billion in potential identity fraud associated with 69,323 questionable and unverified Social Security numbers across disbursed COVID-19 EIDL and PPP loan program applications. PRAC found that if SBA had been able to verify the accuracy of the Social Security numbers on borrower applications, it could have reduced the possibility of identity theft and ensured that benefits were paid only to eligible recipients. However, the process of implementing a new Social Security number verification agreement and addressing the legal questions regarding information sharing can be lengthy, and the time required to establish these types of agreements can create delays and challenges, particularly in an emergency. PRAC found that having such agreements in place before an emergency occurs would ensure timely access to verification information and protect taxpayer funds from improper payments.[40] According to SBA officials, it has been pursuing access to Treasury services such as Account Verification Services and other external data.

Agencies can also use technology to strengthen controls. Federal internal control standards note that automated control activities—which are either wholly or partially automated through an entity’s information technology—tend to be more reliable because they are less susceptible to human error and are typically more efficient.[41]

In June 2023, we noted that agencies reported providing technology and tools—such as software, automation, and information systems—to successfully address root causes of improper payments, including at HHS and VA. For example:

· HHS. In its fiscal year 2022 agency financial report, HHS reported that, due to the high volume of Medicare claims processed daily and significant cost associated with conducting medical reviews of an individual claim, it relies on automated edits to identify inappropriate claims in the Medicare Fee-for-Service program. HHS designed its system to detect anomalies and prevent payment for many erroneous claims.

· VA. According to VA officials, VHA developed a PIIA dashboard that allowed leadership to identify where errors were occurring and target those areas for follow-up. VHA also worked with program subject-matter experts to gain access to systems containing the documentation required for improper payments testing, leading to more accurate and efficient information gathering and review. VA officials also noted that the agency developed an internal system for sharing corrective action plans that helped enhance the process.

Preparing for the Next Emergency

Emergencies are inevitable and have become costlier and more frequent. For fiscal years 2015 through 2024, appropriations for disaster assistance totaled at least $448 billion.[42] Additionally, in December 2024 the Disaster Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2025, appropriated $110 billion in supplemental appropriations for disaster assistance.[43] As a result, it is critical that federal programs manage their improper payment and fraud risks before an emergency occurs so that they are better positioned to identify and respond to the heightened risks that exist during emergencies.

As noted in our Framework for Managing Improper Payments in Emergency Assistance Programs, federal program managers should commit to managing improper payments early by developing internal control plans that can be immediately or quickly tailored to fit the circumstances of a future emergency. Such plans could have potential eligibility criteria and controls designed for likely future emergencies, such as natural disasters. The plans could also contain components such as those for identifying emergency-related risks and controls to address these risks.

Effective and robust plans for internal control can help agencies adapt to changing risks and new priorities. We have identified examples where agencies may have benefitted from having prepared internal control plans for emergency situations, including SBA and DOL. For example:

· SBA. Given the immediate need for small business loans during the COVID-19 pandemic, SBA worked to set up PPP so that lenders could begin distributing funds as soon as possible. Specifically, SBA implemented PPP on April 3, 2020, 1 week after the enactment of its authorizing legislation. By April 16, 2020, just 14 days after SBA implemented the program, lenders had approved more than 1.6 million loans totaling nearly $342.3 billion.[44] Because the need to provide funds quickly increased the risk of fraud, SBA would have benefitted from having plans in place prior to the emergency. Such plans could have helped ensure that program managers considered improper payment risks associated with emergency funding (such as the volume of transactions and speed at which they were processed) and implemented basic preventive controls to help mitigate those risks prior to disbursing the emergency assistance. For example, antifraud controls within the internal control plan could have included using prepayment data analytics, such as the Do Not Pay system, as well as processes to screen payments for potential ineligibility or fraud.

· DOL. In 2020, DOL’s Pandemic Unemployment Assistance program expanded unemployment benefits to independent contractors, self-employed individuals, and others not traditionally eligible for these benefits. Applicants were required to self-certify that they were eligible for pandemic-related assistance before payments were sent. Also in 2020, the DOL OIG reported self-certification as a top fraud vulnerability for state workforce agencies administering pandemic-related unemployment benefits.[45] Congress addressed this issue in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021 by creating new documentation requirements for Pandemic Unemployment Assistance claimants. However, the program had already become an attractive target for increasingly sophisticated fraud schemes.[46] Preexisting internal control plans might have helped managers quickly implement appropriate controls before payments were disbursed—such as leveraging existing data-matching services to validate individuals’ employment status. In emergencies, such plans may also help agencies to expedite more timely postpayment reviews.

Congress Can Act to Increase Accountability over Improper Payments and Fraud

In our March 2022 testimony before the Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, we identified 10 actions that Congress could take to strengthen internal controls and financial and fraud risk management practices across the government.[47] These recommendations to Congress remain open as of February 2025. We maintain that the actions detailed below will increase accountability and transparency in federal spending in both emergency and nonemergency periods.

Make payment integrity enhancements. We made three recommendations to Congress to consider legislative action to further enhance payment integrity efforts across the government.

· Establish a permanent analytics center of excellence to aid the oversight community in identifying improper payments and fraud. This could be achieved by building upon and expanding the Pandemic Analytics Center of Excellence (PACE) and making it permanent.[48]

· Reinstate the requirement that agencies report on their antifraud controls and fraud risk management efforts in their annual financial reports to improve transparency and accountability.[49]

· Require OMB to (1) provide guidance for agencies to proactively develop internal control plans that would be ready for use in, or adaptation for, future emergencies or crises and (2) require agencies to report these plans to OMB and Congress. [50]

Amend PIIA. In November 2020, we recommended that Congress consider, in any future legislation appropriating COVID-19 relief funds, designating all executive agency programs and activities that made more than $100 million in payments from COVID-19 relief funds as “susceptible to significant improper payments.”[51] Such a designation would require, among other things, agencies to report improper payment estimates for such a program and develop corrective actions to reduce improper payments. In March 2022, we recommended that Congress amend PIIA to apply this criterion to all new federal programs for their initial years of operation.[52] The current approach resulted in 2-to-3-year delays in reporting improper payment estimates for short-term and emergency spending COVID-19 relief programs.

Strengthen management of improper payment risks and spending data. Since enactment of the CFO Act,[53] accounting and financial reporting standards have continued to evolve to provide greater transparency and accountability over the federal government’s operations and financial condition, including long-term fiscal sustainability.

In August 2020, we made eight recommendations to Congress to consider ways to improve federal financial management through refinements to the CFO Act and related statutes.[54] Such actions included that Congress consider legislation to require that

· chief financial officers (CFO) and deputy CFOs at the CFO Act agencies have the necessary responsibilities to carry out federal financial management activities effectively;[55]

· agency leadership identify and, if necessary, develop key financial management information needed for effective financial management and decision-making;[56]

· agency leadership annually assess and report on the effectiveness of internal controls over key financial management information;[57] and

· auditors, as part of each annual financial statement audit, test and report on agency internal control over key financial management information.[58]

In March 2022, based on experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic and the rapid growth and magnitude of improper payments, we made three additional recommendations to Congress to consider passing legislation to do the following.[59]

· Clarify that (1) CFOs at CFO Act agencies have oversight responsibility that includes improper payment information and (2) internal controls for financial management information include controls over spending data and improper payment information.[60]

· Require each agency CFO to (1) certify, in the financial statement report, the reliability of improper payment risk assessments and the validity of improper payment estimates, including describing the CFO’s actions to monitor the development and implementation of any corrective action plans, and (2) approve any methodology that is not designed to produce a statistically valid estimate.[61]

· Require that improper payment information required to be reported under PIIA to be included in agency financial reports.

Extend requirements for IGs to report on USAspending.gov data. In March 2022, we testified about the lack of quality federal spending data for financial management reviews.[62] Quality federal spending data are key to management assessing whether agencies are meeting program objectives. In addition, providing clear and transparent information about limitations and inconsistencies of data can help users understand the extent to which the data are comparable and reliable.

We recommended that Congress consider amending the Digital Accountability and Transparency Act of 2014 (DATA Act) to (1) extend the previous requirement for agency IGs to review the completeness, timeliness, quality, and accuracy of their respective agency data submissions on a periodic basis;[63] and (2) clarify the responsibilities and authorities of OMB and Treasury for ensuring the quality of data available on USAspending.gov.

Amend the Social Security Act regarding the sharing of full death data. Data sharing can allow agencies to enhance their efforts to prevent improper payments to deceased individuals. To enhance identity verification through data sharing, we have previously recommended that Congress consider amending the Social Security Act to explicitly allow the Social Security Administration (SSA) to share its full death data with Treasury’s Do Not Pay system, a data-matching service for agencies to use in preventing payments to ineligible individuals.[64] In December 2020, Congress passed, and the President signed into law, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021, which requires SSA to share its full death data with Treasury’s Do Not Pay system for a 3-year period.[65] Without congressional action, the requirement for SSA to share its full death data with Do Not Pay will expire in December 2026. In March 2022, we recommended that Congress consider making permanent the requirement for SSA to share its full death data with Treasury’s Do Not Pay system.[66]

Continued congressional oversight is critical to ensuring that agencies address improper payments and fraud in their programs. Congress can use a variety of tools— such as hearings and the appropriations, authorizations, and oversight processes—to incentivize executive branch agencies to improve program integrity and take efforts to prevent fraud.

If Congress creates emergency assistance programs in the future or any new programs during normal program operations, our Fraud Risk Framework and Framework for Managing Improper Payments in Emergency Assistance Programs and our overall body of work related to addressing the risks of improper payments and fraud can inform what Congress considers regarding the design and requirements for such programs.

Thank you, Chairman Sessions, Ranking Member Mfume, and Members of the Subcommittee. This concludes my testimony. I would be pleased to answer any questions.

GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments

If you or your staff have any questions about this testimony, please contact M. Hannah Padilla, Director, Financial Management and Assurance at (202) 512-5683 or PadillaH@gao.gov or Seto J. Bagdoyan, Director, Forensic Audits and Investigative Service at (202) 512-6722 or BagdoyanS@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this statement.

GAO staff who made key contributions to this testimony are Heather Dunahoo and Daniel Flavin (Assistant Directors), Sophie Geyer (Auditor in Charge), Caitlin Croake, Giovanna Cruz, Pat Frey, Jason Kirwan, Daniel Silva, Amanda Stogsdill, and Alexa Young. Other staff who made key contributions to the reports cited in the testimony are identified in the source products.

Related GAO Products

Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO‑14‑704G (Washington, D.C., September 10, 2014).

A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs, GAO‑15‑593SP, (Washington, D.C., July 28, 2015).

Medicare: Claim Review Programs Could Be Improved with Additional Prepayment Reviews and Better Data, GAO‑16‑394 (Washington, D.C.: April 13, 2016).

Improper Payments: Strategy and Additional Actions Needed to Help Ensure Agencies Use the Do Not Pay Working System as Intended, GAO‑17‑15 (Washington, D.C.: October 14, 2016).

Medicare and Medicaid: CMS Needs to Fully Align Its Antifraud Efforts with the Fraud Risk Framework, GAO‑18‑88 (Washington, D.C.: December 5, 2017).

Federal Student Loans: Education Needs to Verify Borrowers’ Information for Income-Driven Repayment Plans, GAO‑19‑347 (Washington, D.C.: June 25, 2019).

Fake Caller ID Schemes: Information on Federal Agencies’ Efforts to Enforce Laws, Educate the Public, and Support Technical Initiatives, GAO‑20‑153 (Washington, D.C.: December 18, 2019).

COVID-19: Opportunities to Improve Federal Response and Recovery Efforts, GAO‑20‑625 (Washington, D.C.: June 25, 2020).

DATA ACT: OIGs Reported That Quality of Agency-Submitted Data Varied, and Most Recommended Improvements, GAO‑20‑540 (Washington, D.C.: July 9, 2020).

Federal Financial Management: Substantial Progress Made since Enactment of the 1990 CFO Act; Refinements Would Yield Added Benefits, GAO‑20‑566 (Washington, D.C.: August 6, 2020).

COVID-19: Urgent Actions Needed to Better Ensure an Effective Federal Response, GAO‑21‑191 (Washington, D.C.: November 30, 2020).

High Risk Series: Dedicated Leadership Needed to Address Limited Progress in Most High-Risk Areas, GAO‑21‑119SP (Washington, D.C.: March 2, 2021).

High-Risk Series: Federal Government Needs to Urgently Pursue Critical Actions to Address Major Cybersecurity Challenges, GAO‑21‑288 (Washington, D.C.: March 24, 2021).

COVID-19: Sustained Federal Action Is Crucial as Pandemic Enters Its Second Year, GAO‑21‑387 (Washington, D.C.: March 31, 2021).

DOD Fraud Risk Management: Actions Needed to Enhance Department-Wide Approach, Focusing on Procurement Fraud Risks, GAO‑21‑309 (Washington, D.C.: August 19, 2021).

COVID-19: Additional Actions Needed to Improve Accountability and Program Effectiveness of Federal Response, GAO‑22‑105051 (Washington, D.C.: October 27, 2021).

Emergency Relief Funds: Significant Improvements Are Needed to Ensure Transparency and Accountability for COVID-19 and Beyond, GAO‑22‑105715, Washington, D.C.: March 17, 2022).

COVID-19: Current and Future Federal Preparedness Requires Fixes to improve Health Data and Address Improper Payments, GAO‑22‑105397 (Washington, D.C.: April 27, 2022).

Emergency Relief Funds: Significant Improvements Are Needed to Address Fraud and Improper Payments, GAO‑23‑106556 (Washington, D.C.: February 1, 2023).

Improper Payments: Programs Reporting Reductions Had Taken Corrective Actions That Shared Common Features, GAO‑23‑106585 (Washington, D.C.: June 30, 2023).

A Framework for Managing Improper Payments in Emergency Assistance Programs, GAO‑23‑105876 (Washington, D.C.: July 13, 2023).

Disaster Recovery: HUD Should Develop Data Collection Guidance to Support Analysis of Block Grant Fraud Risks, GAO‑23‑104382 (Washington, D.C.: August 17, 2023).

Improper Payments and Fraud: How They Are Related but Different, GAO‑24‑106608 (Washington, D.C.: December 7, 2023).

DOD Fraud Risk Management: Enhance Data Analytics Can Help Manage Fraud Risks, GAO‑24‑105358 (Washington, D.C.: February 27, 2024).

Fraud Risk Management: 2018-2022 Data Show Federal Government Loses an Estimated $233 Billion to $521 Billion Annually to Fraud, Based on Various Risk Environments, GAO‑24‑105833 (Washington, D.C.: April 16, 2024).

Improper Payments: Key Concepts and Information on Programs with High Rates or Lacking Estimates, GAO-24-107482 (Washington, D.C.: June 27, 2024).

Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, 2024 Exposure Draft, GAO‑24‑106889 (Washington, D.C., June 27, 2024).

Pandemic Unemployment Assistance: States’ Controls to Address Fraud, GAO‑24‑107471 (Washington, D.C.: July 23, 2024).

Payment Integrity: Significant Improvements Are Need to Address Improper Payments and Fraud, GAO‑24‑107660 (Washington, D.C.: September 10, 2024).

High-Risk Series: Heightened Attention Could Save Billions More and Improve Government Efficiency and Effectiveness, GAO‑25‑107743 (Washington, D.C.: February 25, 2025).

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on Facebook, Flickr, X, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our RSS Feeds or Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7700

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, ClowersA@gao.gov, (202) 512-4400, U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7125, Washington, DC 20548

Public Affairs

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, KaczmarekS@gao.gov, (202) 512-4800, U.S.

Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7149

Washington, DC 20548

Strategic Planning and External Liaison

Stephen J. Sanford, Managing

Director, spel@gao.gov, (202) 512-4707

U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7814, Washington,

DC 20548

[1]An improper payment is defined by law as any payment that should not have been made or that was made in an incorrect amount (including overpayments and underpayments) under statutory, contractual, administrative, or other legally applicable requirements. It includes any payment to an ineligible recipient, any payment for an ineligible good or service, any duplicate payment, any payment for a good or service not received (except for such payments where authorized by law), and any payment that does not account for credit for applicable discounts. 31 U.S.C. § 3351(4). When an executive agency’s review is unable to discern whether a payment was proper because of insufficient or lack of documentation, that payment must also be included in the improper payment estimate. 31 U.S.C. § 3352(c)(2)(A).

[2]GAO, Improper Payments and Fraud: How They Are Related but Different, GAO‑24‑106608 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 7, 2023).

[3]GAO, Improper Payments: Key Concepts and Information on Programs with High Rates or Lacking Estimates, GAO‑24‑107482 (Washington, D.C.: June 27, 2024).

[4]GAO, Fraud Risk Management: 2018-2022 Data Show Federal Government Loses an Estimated $233 Billion to $521 Billion Annually to Fraud, Based on Various Risk Environments, GAO‑24‑105833 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 16, 2024).

[5]GAO maintains its High Risk List to focus attention on government operations that it identifies as high risk due to their greater vulnerability to fraud, waste, abuse, and mismanagement or their need for transformation to address economy, efficiency, or effectiveness challenges. See GAO, High-Risk Series: Heightened Attention Could Save Billions More and Improve Government Efficiency and Effectiveness, GAO‑25‑107743 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 25, 2025).

[6]HHS annually computes separate improper payment estimates for each of the three components within the Medicare program. The overall Medicare improper payment estimate is the sum of the three components’ estimates. The components are (1) fee-for-service, also known as Original Medicare, which covers Parts A and B; (2) managed care, also known as Medicare Part C or Medicare Advantage; and (3) Medicare Part D, a federal prescription drug benefit for Medicare beneficiaries.

[7]HHS annually computes Medicaid improper payment estimates as a weighted average of states’ improper payment estimates for three component parts: (1) fee-for-service, (2) managed care, and (3) beneficiary eligibility determinations.

[8]Office of Management and Budget, Requirements for Payment Integrity Improvement, Circular No. A-123, Appendix C, OMB M-21-19 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 5, 2021). The Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) PaymentAccuracy.gov data call for fiscal year 2024 included guidance for agencies to use when reporting the types of their estimated improper payments. This guidance was in addition to that provided in OMB M-21-19 on reporting estimates for programs or activities that are identified as susceptible to improper payments. According to OMB M-21-19, “overpayments” are payments exceeding the amount due, and are payments that, in theory, should or could be recovered. “Underpayments” are those in which recipients did not receive the funds to which they were entitled. “Unknown payments” are those that a program cannot determine were either proper or improper. “Technically improper payments” are those in which recipients received funds they were entitled to, but the payment failed to follow all applicable statutes or regulations.

[9]In April 2022, we recommended Congress consider providing HHS the authority to require states to report data necessary to estimate and report on TANF improper payments. As of February 2025, no new legislation has been enacted to address this recommendation. GAO, COVID-19: Current and Future Federal Preparedness Requires Fixes to improve Health Data and Address Improper Payments, GAO‑22‑105397 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 27, 2022).

[10]In May 2024, HUD’s Office of Inspector General reported that lack of proper planning and coordination from leadership in the program and support offices prevented HUD from addressing the root causes behind the failure to report improper payment estimates for the Tenant-Based Rental Assistance program. According to HUD’s Office of the Chief Financial Officer, HUD may not be able be produce a compliant estimate until fiscal year 2027. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Inspector General, HUD Did Not Comply With the Payment Integrity Information Act of 2019, 2024-FO-0006 (Washington, D.C.: May 17, 2024). SBA’s fiscal year 2024 agency financial report notes that SBA has begun testing a sample population from the Shuttered Venue Operators Grant program in order to estimate improper payments. According to the report, SBA expects to have an improper payment estimate for the program available in fiscal year 2025, budget permitting. Small Business Administration, Fiscal Year 2024 Agency Financial Report, (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 15, 2024).

[11]The CFO Act, Pub. L. No. 101-576, 104 Stat. 2838 (codified as amended in scattered sections of 31 U.S.C.), among other things, established chief financial officers to oversee financial management activities at 23 major executive departments and agencies. The list now includes 24 entities, which are often referred to collectively as CFO Act agencies, and is codified as amended at 31 U.S.C. § 901(b). We focused on the 24 CFO Act agencies because the improper payment estimates for those agencies accounted for over 99 percent of the federal government’s reported estimated improper payments for fiscal year 2024. However, PIIA applies to both CFO Act and non-CFO Act executive agencies. According to PaymentAccuracy.gov, 44 out of the 59 executive branch agencies reporting in fiscal year 2023 were determined by their respective IGs to be compliant with PIIA criteria. Per OMB M-21-19, the compliance reports are due within 180 days following the publishing of agencies’ annual financial statements and accompanying materials, which typically occurs in mid-November. The most recent IG compliance reports available were issued in 2024 for agencies’ fiscal year 2023 compliance with PIIA criteria.

[12]GAO‑24‑105833. As described above, our estimate for fraud is not comparable to improper payment estimates. Agency improper payment estimates are based on a subset of federal programs, using a methodology not designed to identify fraud. We have consistently reported that the federal government does not know the full extent of improper payments and have long recommended that agencies improve their improper payment estimate reporting. In contrast, our fraud estimate includes all federal programs and operations and is based on fraud-related data. With these differences in scope and data, the upper end of our estimated fraud range ($521 billion) exceeded annual improper payment estimates ($236 billion for fiscal year 2023).

[13]GAO identifies priority open recommendations each year. These are GAO recommendations that have not been implemented and warrant priority attention from heads of key departments or agencies because their implementation could help the federal government save large amounts of money or significantly improve government operations. See GAO, Priority Open Recommendations: Office of Management and Budget, GAO‑24‑107364 (Washington, D.C.: Aug. 9, 2024).

[15]GAO, Unemployment Insurance: Estimated Amount of Fraud during Pandemic Likely Between $100 Billion and $135 Billion, GAO‑23‑106696 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 12, 2023).

[16]Small Business Administration, Protecting the Integrity of the Pandemic Relief Programs: SBA’s Actions to Prevent, Detect and Tackle Fraud (Washington, D.C.: June 2023).

[17]Small Business Administration, Office of Inspector General, COVID-19 Pandemic EIDL and PPP Loan Fraud Landscape, White Paper Report 23-09 (Washington, D.C.: June 27, 2023).

[18]GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, 2024 Exposure Draft, GAO‑24‑106889 (Washington, D.C., June 2024).

[19]GAO, A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs, GAO‑15‑593SP, (Washington, D.C., Jul. 28, 2015). This framework provides leading practices in a risk-based framework to aid program managers in taking a strategic, risk-based approach to managing fraud risks and developing effective antifraud controls.

[20]GAO, A Framework for Managing Improper Payments in Emergency Assistance Programs, GAO‑23‑105876 (Washington, D.C.: July 13, 2023). This framework provides Congress and federal agencies with an overall approach to preventing and reducing improper payments in emergency assistance programs.

[21]Postpayment reviews and improper payment recovery audits are financial management practices that agencies can use to determine whether payments were made appropriately to eligible recipients in correct amounts and used by recipients in accordance with law and applicable agreements.

[23]GAO, Pandemic Unemployment Assistance: States’ Controls to Address Fraud, GAO‑24‑107471 (Washington, D.C.: July 23, 2024).

[24]GAO, Medicare: Claim Review Programs Could Be Improved with Additional Prepayment Reviews and Better Data, GAO‑16‑394 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 13, 2016).

[25]Department of the Treasury, Fiscal Year 2024 Agency Financial Report (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 15, 2024). We have previously recommended that Congress consider amending the Social Security Act to explicitly allow the Social Security Administration to share its full death data with Treasury’s Do Not Pay system. GAO, Improper Payments: Strategy and Additional Actions Needed to Help Ensure Agencies Use the Do Not Pay Working System as Intended, GAO‑17‑15 (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 14, 2016), and COVID-19: Opportunities to Improve Federal Response and Recovery Efforts, GAO‑20‑625 (Washington, D.C.: June 25, 2020).

[26]OMB Memorandum M-21-19 provides additional guidance to agencies on conducting the improper payment risk assessment required by 31 U.S.C. § 3352(a). Additionally, federal program managers are responsible for identifying, assessing, and responding to risks (including the potential for fraud) while a program seeks to achieve its objectives. According to Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, a risk assessment is the identification and analysis of risks related to achieving the defined objectives, and the assessment forms the basis for designing risk responses. When conducting a risk assessment, managers should consider internal risk factors, such as the complex nature of the program, and external factors, such as potential natural disasters. To focus managers’ attention on the need to take a more strategic, risk-based approach to managing fraud risks, managers are required to consider the potential for fraud and fraud risks as part of their risk assessment activities. GAO’s Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs provides comprehensive guidance for conducting these assessments and using the results as part of developing a robust antifraud strategy.

[27]OMB M-21-19.

[28]OMB’s PaymentAccuracy.gov data call for fiscal year 2024 included guidance for agencies to use when reporting the types of their estimated improper payments. This guidance was in addition to that provided in OMB M-21-19 on reporting estimates for programs that are identified as susceptible to improper payments.

[29]GAO‑15‑593SP. Also, see GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO‑14‑704G (Washington, D.C., Sept. 2014), and Medicare and Medicaid: CMS Needs to Fully Align Its Antifraud Efforts with the Fraud Risk Framework, GAO‑18‑88 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 5, 2017).

[30]GAO, Federal Student Loans: Education Needs to Verify Borrowers’ Information for Income-Driven Repayment Plans, GAO‑19‑347 (Washington, D.C.: June 25, 2019); Fake Caller ID Schemes: Information on Federal Agencies’ Efforts to Enforce Laws, Educate the Public, and Support Technical Initiatives, GAO‑20‑153 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 18, 2019); High-Risk Series: Federal Government Needs to Urgently Pursue Critical Actions to Address Major Cybersecurity Challenges, GAO‑21‑288 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 24, 2021); and DOD Fraud Risk Management: Actions Needed to Enhance Department-Wide Approach, Focusing on Procurement Fraud Risks, GAO‑21‑309 (Washington, D.C.: Aug. 19, 2021).

[31]GAO, COVID-19: Sustained Federal Action Is Crucial as Pandemic Enters Its Second Year, GAO‑21‑387 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 31, 2021).

[32]GAO, COVID-19: Additional Actions Needed to Improve Accountability and Program Effectiveness of Federal Response, GAO‑22‑105051 (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 27, 2021).

[33]GAO, Improper Payments: Programs Reporting Reductions Had Taken Corrective Actions That Shared Common Features, GAO‑23‑106585 (Washington, D.C.: Jun. 30, 2023).

[35]GAO, High-Risk Series: Dedicated Leadership Needed to Address Limited Progress in Most High-Risk Areas, GAO‑21‑119SP (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 2, 2021).

[37]5 U.S.C. § 552a(b). For example, data sharing between federal agencies may be allowed if it is for a purpose that is compatible with the purpose for which the data were collected, referred to as routine use. 5 USC 552a(b)(3),(a)(7). While increased data sharing can help identify and reduce improper payments, identity verification involves individuals’ personal information, such as mailing address, date of birth, and Social Security number, which can create privacy risks. According to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), organizations could potentially mitigate these risks by assessing the risk associated with online transactions and selecting the appropriate assurance level for each. A low assurance level reduces the amount of personal information that organization must collect but increases the risk of improper payments. On the other hand, a high assurance level may increase the burden on applicants, including those who are not misrepresenting their identities. NIST develops information-security standards and guidelines, including the minimum requirements for federal information systems. Joint Financial Management Improvement Program, Key Practices to Reduce Improper Payments through Identity Verification (July 2022).

[38]GAO, DOD Fraud Risk Management: Enhanced Data Analytics Can Help Manage Fraud Risks, GAO‑24‑105358 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 27, 2024).

[39]GAO, Disaster Recovery: HUD Should Develop Data Collection Guidance to Support Analysis of Block Grant Fraud Risks, GAO‑23‑104382 (Washington, D.C.: Aug. 17, 2023).

[40]Pandemic Response Accountability Committee, Fraud Alert: PRAC Identifies $5.4 Billion in Potentially Fraudulent Pandemic Loans Obtained Using over 69,000 Questionable Social Security Numbers (Jan. 30, 2023).

[42]This total includes $312 billion in selected supplemental appropriations to federal agencies for disaster assistance and approximately $136 billion in annual appropriations to the Disaster Relief Fund for fiscal years 2015 through 2024. It does not include other annual appropriations to federal agencies for disaster assistance. Of the supplemental appropriations, $97 billion was included in supplemental appropriations acts that were enacted primarily in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Pub. L. No. 118-158, div. B, 138 Stat. 1722 (2024).

[43]Pub. L. No. 118-158, div. B, 138 Stat. 1722 (2024).

[44]Small Business Administration, Office of Inspector General, Inspection of SBA’s Implementation of the Paycheck Protection Program, 21-07 (Washington D.C.: Jan. 14, 2021).

[45]Department of Labor, Office of Inspector General, COVID-19: States Struggled to Implement Cares Act Unemployment Insurance Programs, 19-21-004-03-315 (Washington D.C.: May 28, 2021).

[46]Individuals who filed a new Pandemic Unemployment Assistance claim on or after January 31, 2021, were required to provide documentation of employment or self-employment within 21 days of application, or following the state deadline if later (with exceptions for good cause). Individuals who received Pandemic Unemployment Assistance on or after December 27, 2020, were required to provide this documentation within 90 days, or within the state deadline if later (with exceptions for good cause). For Pandemic Unemployment Assistance claims filed on or after January 26, 2021, states were required to use administrative procedures to verify the identity of Pandemic Unemployment Assistance applicants and provide timely payment, to the extent reasonable and practicable. The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021 also included a new statutory requirement for weekly self-certification by claimants of a COVID 19-related condition for weeks on or after January 26, 2021. For more information, see GAO‑22‑105051.

[47]GAO‑22‑105715. In February 2023, we reiterated these actions in testimony before the House Committee on Oversight and Accountability. GAO, Emergency Relief Funds: Significant Improvements Are Needed to Address Fraud and Improper Payments, GAO‑23‑106556 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 1, 2023). We also noted the actions in September 2024 testimony before the Subcommittee on Government Operations and the Federal Workforce, House Committee on Oversight and Accountability. GAO, Payment Integrity: Significant Improvements Are Need to Address Improper Payments and Fraud, GAO‑24‑107660 (Washington, D.C.: Sep. 10, 2024).

[48]PACE is focused on pandemic programs, absent congressional action, its funding is set to expire in 2025. The Pandemic Response Accountability Committee created PACE, which helps agencies identify potential fraud for investigation by combining oversight data in one place with a suite of analytic tools.

[49]The STEP Act (S. 80) contains provisions that would address this recommendation. As of March 6, 2025, Congress has not passed this bill.

[50]The TRUE Accountability Act (S. 78) contains provisions that would address this recommendation. As of March 6, 2025, Congress has not passed this bill.

[51]GAO, COVID-19: Urgent Actions Needed to Better Ensure an Effective Federal Response, GAO‑21‑191 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 30, 2020).