MISSILE DEFENSE

DOD Faces Support Challenges for Defense of Guam

Report to the Committee on Armed Services, House of Representatives

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Diana Maurer at maurerd@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑108187, a report to the Committee on Armed Services, House of Representatives

DOD Faces Support Challenges for Defense of Guam

Why GAO Did This Study

DOD has determined that protecting Guam is a critically important priority for the Indo-Pacific region. Currently, the department defends Guam with a battery of six missile launchers and one radar. In response to increased military activity by China in the Indo-Pacific region, DOD has begun developing an enhanced missile defense capability to defend Guam.

House Report 118-125 includes a provision for GAO to examine DOD’s plans to sustain and support GDS. GAO’s review assesses the extent to which DOD has developed (1) an organizational structure for GDS, and (2) plans for supporting GDS units.

GAO conducted site visits to installations in Guam, Hawaii, and Japan to obtain information on plans for Guam missile defense. GAO compared documentation and information obtained from interviews to DOD guidance on organization, personnel support, and coordination.

What GAO Recommends

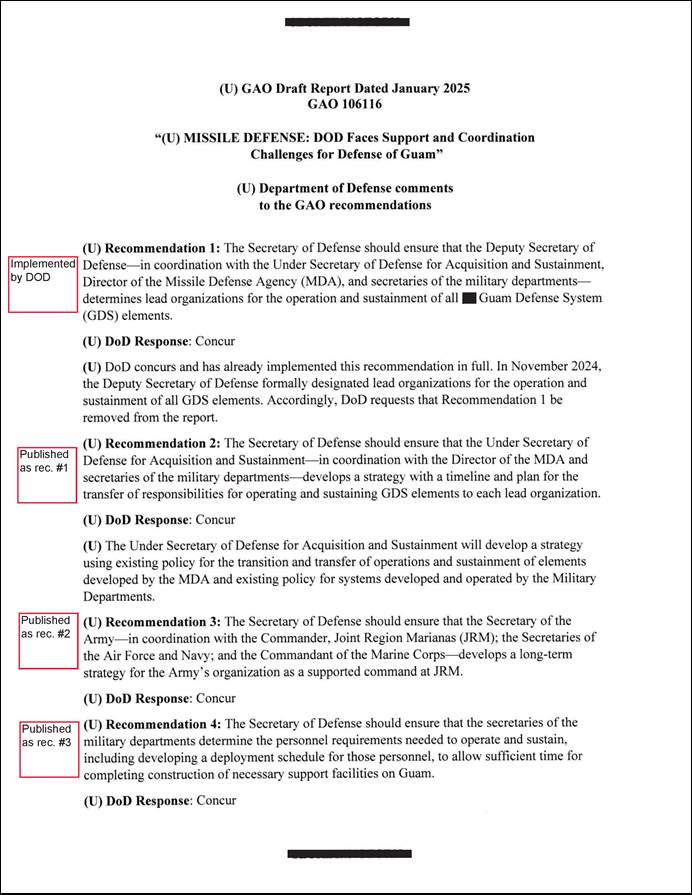

GAO is making three recommendations, including for the Secretary of Defense to direct relevant military components to develop strategies with a timeline and a plan for transferring responsibilities to lead organizations and for integrating the Army with bases in Guam; and determine personnel requirements and deployment schedules for GDS personnel. GAO made a fourth recommendation, which DOD classified SECRET//NOFORN. DOD concurred with all four of GAO’s recommendations.

What GAO Found

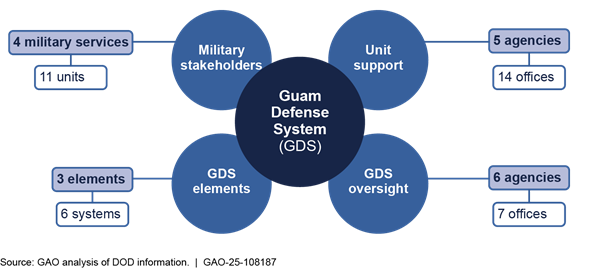

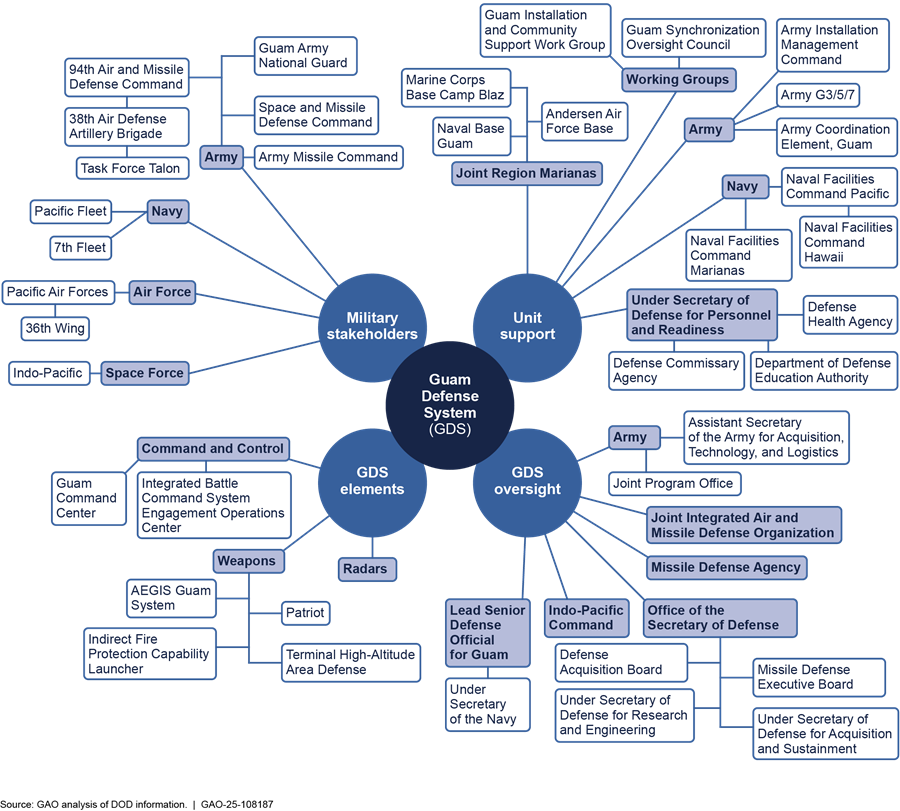

The Department of Defense (DOD) has taken steps to establish an organizational structure for overseeing and sustaining an enhanced missile defense system known as the Guam Defense System (GDS). In addition, DOD has designated lead services for operating and sustaining the elements that make up the GDS. However, there are unresolved challenges that could hamper the success of DOD’s efforts:

· DOD lacks a strategy that outlines how and when responsibilities for operating and sustaining GDS elements will transfer to their lead organizations.

· The Army does not have a long-term strategy for integrating with the other military services in Guam to coordinate Army construction and installation support needed to support GDS and personnel.

DOD Offices’ Roles and Responsibilities for Missile Defense in Guam

DOD has not fully identified the required number of personnel or completed a deployment schedule for GDS units. This information enables the military services to fund, plan, and build the housing, schools, medical facilities, and commissaries supporting GDS personnel. Absent personnel requirements and a deployment schedule, DOD faces challenges in ensuring adequate support infrastructure at installations in Guam for deployed personnel and their families.

This report is an unclassified release of a previously-issued report DOD classified SECRET//NOFORN. This unclassified release omits one objective and one recommendation due to the use of information classified SECRET//NOFORN, and throughout the remaining objectives omits information DOD has determined to be either SECRET//NOFORN or Controlled Unclassified Information.

Abbreviations

|

DOD |

Department of Defense |

|

GDS |

Guam Defense System |

|

INDOPACOM |

Indo-Pacific Command |

|

JPO |

Joint Program Office |

|

JRM |

Joint Region Marianas |

|

MDA |

Missile Defense Agency |

|

THAAD |

Terminal High-Altitude Area Defense |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

May 22, 2025

The Honorable Mike Rogers

Chairman

The Honorable Adam Smith

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

House of Representatives

Protecting Guam—a U.S. territory that is home to more than 170,000 Americans and several military installations—is a critically important priority for the Department of Defense (DOD) for the Indo-Pacific region. Specifically, Guam is a key strategic location for sustaining U.S. influence, deterring adversaries, responding to crises, and maintaining a free and open Indo-Pacific region.[1] DOD’s 2022 Missile Defense Review, which describes Guam as an unequivocal part of the United States, outlines the importance of a robust set of missile defense capabilities for the continued protection of Guam.[2] DOD has one missile defense system currently deployed to Guam, a Terminal High-Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) battery comprising six missile launchers and one radar.[3] In addition, the Navy’s 7th Fleet provides missile defense by sea.

In response to increased military activity from China in the Indo-Pacific region, DOD has begun developing a more robust missile defense system to defend Guam from this rising threat. In fiscal year 2022, DOD decided to develop and deploy an enhanced integrated air and missile defense system to Guam known as the Guam Defense System (GDS). The department plans for GDS to provide a persistent, 360-degree defense of Guam against rapidly evolving threats from regional adversaries.[4] In preparation for GDS, the Deputy Secretary of Defense designated the Army as the Service Acquisition Executive for the system and the Under Secretary of the Navy as the Lead Senior Defense Official for Guam.[5]

We have previously reported on a range of missile defense issues, including reports on the delivery, operation, and sustainment of systems across the DOD enterprise. For example, in December 2024, we reported that DOD lacked defined operational requirements for the missile defense of Guam.[6] Also, in June 2023, we reported that DOD lacked comprehensive guidance for sustaining missile defense systems, including interceptors, sensors, and communications across the globe.[7] For a detailed list of our recent missile defense-related reports, see “Related GAO Products” at the end of this report.

A report accompanying a bill for the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024 included a provision that we examine DOD’s plans to sustain and support GDS.[8] Our review assesses the extent to which DOD has developed (1) an organizational structure for overseeing and sustaining GDS, and (2) plans for supporting future missile defense units in Guam.

This report is an edited version of a classified report, published in February 2025.[9] This unclassified version omits an objective from our earlier report because DOD classified our finding, conclusions and recommendation for that objective as SECRET//NOFORN. We also omitted two figures and an appendix identifying the missile defense elements composing the Guam Defense System, which DOD either classified SECRET//NOFORN or designated as Controlled Unclassified Information. We omitted other classified information and Controlled Unclassified Information throughout the report, as necessary, to produce this version.

For all objectives, we focused on the GDS elements that DOD plans to field in Guam—that is, the launchers, radars and sensors, missiles, and command and control systems. We conducted site visits to installations in Guam, Hawaii, and Japan to obtain information on the current and planned missile defense architecture in Guam. In Guam, we visited each of the proposed sites for GDS to observe site conditions, access to utilities, and potential hazards at each location. We also interviewed officials from the Office of the Secretary of Defense, Joint Chiefs of Staff, Missile Defense Agency (MDA), military services, and Government of Guam about plans to sustain and support missile defense in Guam. See appendix I for a full list of the key organizations we interviewed and the installations we visited on our review.

For the first objective, we reviewed DOD’s policy documents establishing GDS, outlining the department’s plans for managing the system, and outlining the Army’s organization in Guam. We compared those documents to DOD guidance on system development, missile defense capabilities, and installation management to determine if DOD has an organizational structure in place to manage the GDS systems and personnel.[10]

For the second objective, we reviewed documents outlining plans, costs, and schedules for support facilities on Guam that identified the capacity of housing, schools, medical care facilities, and commissaries. We compared information on DOD’s plans for supporting missile defense units to relevant force structure policy and Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government to determine the extent to which DOD has identified how it will support additional personnel coming to Guam for GDS.[11] For purposes of this review, we reviewed only DOD facilities as the department is in the process of completing an environmental study that will examine the effects of GDS on local utilities, real estate, and environment. We describe some potential effects of GDS on Guam in appendix II.

We conducted this performance audit from October 2023 to February 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We subsequently worked with DOD from March 2025 to May 2025 to prepare this unclassified version of the original classified report for public release. This version was also prepared in accordance with these standards.

Background

Overview of Missile Defense in Guam

In April 2013, the Secretary of Defense approved deployment of a THAAD battery to Guam, which the department assigned to the Army’s Task Force Talon. Task Force Talon’s primary mission is to defend against missile threats from North Korea, with six missile launchers and one radar system. From 2013 through 2016, DOD operated Task Force Talon as an expeditionary—or temporary—force using personnel from Hawaii on rotational assignments. Since June 2016, DOD began permanently stationing Task Force Talon in Guam, where it has operated as the only missile defense system on the island. As currently structured, Task Force Talon reports to the Army’s 38th Air Defense Artillery Brigade in Japan, and that brigade falls underneath the Army’s 94th Air and Missile Defense Command in Hawaii. We omitted other information about the current Guam missile defense posture because DOD classified it as SECRET//NOFORN.

For its future presence with GDS, DOD plans to operate and sustain missile defense elements in Guam, including missile launchers, radars and sensors, missiles, and command and control systems. DOD intends for all elements to operate as one integrated missile defense system in Guam under one facility on the island, the Guam Command Center. We omitted a depiction of how the GDS elements would defend against missile launches because DOD determined that information to be Controlled Unclassified Information.

DOD plans to distribute GDS elements across 16 sites in Guam, as of August 2024. The department plans to deploy the new GDS elements in phases, with the first deployment beginning in fiscal year 2027 and the final GDS elements arriving by fiscal year 2032. DOD will deploy this way in an effort to incrementally increase missile defense capability in Guam. We omitted a map showing the proposed locations on Guam for these missile defense elements as of August 2024, because DOD classified this map as SECRET//NOFORN.

On January 7, 2025, the Deputy Secretary of Defense directed the MDA to cease development of one of the elements, the AN/TPY-6 radar, but to retain the currently-fielded panel in the field as an experimental asset with potential to develop for operational use within the GDS in the future. A DOD official told us these changes in the then-deputy secretary’s classified memorandum are not binding on the new administration. For a description of the publicly releasable changes stemming from this memorandum, see appendix III.

Roles and Responsibilities

An array of DOD offices have key roles and responsibilities for missile defense in Guam, including offices that provide unit support and oversight (see fig. 1).

Specifically, the following DOD offices have had significant roles and responsibilities in planning for support of the deployed units and GDS elements:

Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment. In June 2023, the Deputy Secretary of Defense designated this Under Secretary as the senior defense official responsible for GDS. The Under Secretary oversees the development and deployment of the various missile defense elements that compose GDS. Additionally, this office has responsibility for managing the issuance of life-cycle sustainment plans.

INDOPACOM. As a regional combatant command, INDOPACOM has responsibility for planning and executing all military operations and activities in the Indo-Pacific region. Additionally, INDOPACOM conducts capability assessments for missile defense elements operating in the region.

Joint Region Marianas (JRM). This organization has responsibility for (1) providing installation management support to all DOD components operating installations in Guam and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands; (2) acting as the interface between DOD and civilian community; and (3) ensuring DOD’s compliance with environmental laws and regulations, among other things. The region has a joint base structure with the Air Force, Marine Corps, and Navy operating their own bases within that structure.[12] DOD has plans to use space at each of the three bases for GDS.

Under Secretary of the Navy. The Deputy Secretary of Defense designated the Under Secretary of the Navy as the Lead Senior Defense Official for Guam in January 2024. Specifically, the Under Secretary of the Navy serves as the senior representative for DOD when meeting with stakeholders in Guam, including the Governor of Guam, and oversees senior-level coordination efforts across the department to meet logistics, environmental, and infrastructure requirements on the island.

Army’s Joint Program Office (JPO). In June 2023, the Deputy Secretary of Defense designated the Army as the Service Acquisition Executive, meaning the Army has responsibility for the oversight of the GDS acquisition. Those responsibilities include managing the acquisition of GDS, as well as determining the overall doctrine, training, organization, personnel, and facilities associated with GDS. The Army also manages the JPO with the intention of leading coordination of missile defense in Guam across the military services and MDA.

MDA. MDA builds and delivers missile defense systems across DOD. Once they are delivered, MDA is responsible for transferring responsibilities for operating and sustaining missile defense systems to another lead organization or it retains those responsibilities itself. Also, MDA—in coordination with the military services and other federal agencies—issued a draft Environmental Impact Statement in October 2024, which identified potential environmental impacts and their associated mitigations for GDS.[13]

Ongoing Military Buildup in Guam

In addition to GDS, DOD has other ongoing construction priorities for each of the military services operating in Guam. The Marine Corps is in the process of relocating Marines from Okinawa to Guam. We have previously reported that Guam has limited housing, according to Marine Corps officials, which presents challenges with the high volume of Marine Corps personnel that will be arriving in Guam.[14] We omitted information from this paragraph about the Marine Corps’ relocation to Guam that DOD classified as SECRET.

The Air Force and Navy also maintain Andersen Air Force Base and Naval Base Guam, respectively. These military services have their own construction priorities for their bases. For example, a JRM briefing provided to us in February 2024 described Air Force construction priorities for munitions storage, warehouses, and hangars. According to another briefing, the Navy also identified construction priorities for additional ship berths in the military harbor, warehouses, and a rebuild of the harbor’s breakwater.

DOD Has Developed Organizations to Manage GDS and Designated Lead Service Responsibilities, but Has Not Transferred Service Responsibilities

DOD has taken steps to establish an organizational structure for overseeing GDS and has designated responsibility to lead services for operating and sustaining all of the GDS elements. However, DOD has not developed a full strategy for the elements to transfer to the lead services. In addition, the Army has limited installation support for its current presence in Guam and has not determined a long-term strategy for supporting additional personnel deployed to support GDS.

DOD Has Taken Steps to Develop How It Will Manage GDS

DOD has taken some steps to develop an organizational structure for overseeing and sustaining GDS, as follows:

· Missile defense coordination. In February 2024, the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment established the JPO, managed by the Army, to lead coordination of missile defense in Guam, according to Army documentation. The Army plans for the JPO to include personnel from the Air Force, Army, Navy, Space Force, and MDA, since they all may have roles in operating and sustaining GDS elements.[15] JPO officials told us that the JPO has initially focused on the development, delivery, and sustainment of GDS. Those officials stated they have a key responsibility to synchronize support of missile defense systems in Guam, including determining how to provide power, roads, and security measures at specific sites.[16]

The Army initially proposed a JPO with 129 personnel composed of program managers, engineers, business management specialists, and construction planners, among other positions.[17] JPO officials told us that they are now planning to have a total of 86 personnel, as they will be relying on some personnel already in Guam for construction functions. As of September 2024, the Army had filled 11 of its planned 86 personnel.[18] According to Army officials, they are leveraging personnel from other offices since the JPO does not yet have its own funding.

· Joint base structure. The Air Force, Marine Corps, and Navy each operate different bases in Guam that are all managed under a joint base structure known as JRM. As the leader for JRM, the Navy integrates, coordinates, and manages efforts across each of the bases in Guam and across the military services. JRM maintains a Joint Memorandum of Agreement between itself and the military services operating in Guam.[19] That memorandum outlines roles and responsibilities for each of the military services operating in the region. Specifically, it establishes the framework for providing installation support functions and how the military services will share costs for those services.

With a growing presence in Guam, the Army signed the Joint Memorandum of Agreement in February 2024. The Army has no plans to establish its own Army base, but it will deploy to different bases managed by the Air Force, Marine Corps, and Navy.[20] According to Army officials, the Army’s signature on the memorandum allows them to begin negotiating installation support services—for example, security, fire protection, and personnel support services—with the bases that make up JRM.

· Working groups for synchronization. DOD established working groups that synchronize defense activities in Guam across the military services. For example, JRM leads the Guam Installation and Community Support Work Group, which is a monthly meeting of senior leaders across DOD to discuss installation issues specific to Guam. There are 10 topics discussed each month that affect the military services, such as housing, utilities, and warehousing.[21] Notably, the working group discusses requests for space or construction at DOD bases, how the military services will synchronize construction priorities, and the status of ongoing studies of defense infrastructure in Guam.

Additionally, the Deputy Secretary of Defense designated the Under Secretary of the Navy as the Lead Senior Defense Official for Guam in a January 2024 memorandum.[22] That same month, the Deputy Secretary of Defense established a Guam Synchronization and Oversight Council, which reviews defense issues in Guam across the military services and includes GDS topics of interest. Specifically, the council’s primary function is to provide senior-level visibility and prioritization of key issues and defense requirements for Guam, including environmental concerns, construction, and community support. The newly established council meets on a quarterly basis, according to its signed charter.

DOD Has Designated Lead Services for All GDS Elements

In addition to developing an organizational structure, DOD has designated lead services for operating and sustaining the elements that make up the GDS. In October 2023, as one of its first responsibilities for managing GDS, the Army recommended to the Office of the Secretary of Defense which DOD organization should operate and sustain each of the GDS elements.[23] In reviewing the Army’s recommendations, the military services and MDA agreed on who would operate and sustain certain GDS elements. However, the lead service designation on several remaining elements remained in dispute.[24] These included elements that are a variation of the AEGIS weapon system deployed at sea on the Navy’s ships.[25] The Army recommended that the Navy and MDA split responsibilities for operating and sustaining those elements. The Navy disagreed with Army’s recommendation since the adapted AEGIS weapon system would be operating on land. We omitted from this paragraph specific information about the GDS elements, which DOD designated as Controlled Unclassified Information.

In a November 7, 2024, memo, the Deputy Secretary of Defense resolved the dispute by designating lead services for the Aegis Guam System, and other remaining GDS elements. Deputy Secretary of Defense’s designation of lead services are summarized in Table 1. We omitted an appendix that included a table of all of the GDS elements because DOD determined the table to be controlled unclassified information. We renumbered the subsequent appendixes accordingly.

|

Type |

Element |

Organization responsible for development |

Organization the Army recommends for operation and sustainment |

Deputy Secretary of Defense November 2024 Decision |

|

Radars and sensors |

AN/TPY-6 Radar |

Missile Defense Agency (MDA) |

Space Force |

Navy is responsible for manning, operations, and sustainment. MDA responsible for software sustainment. |

|

MK-99 |

Navy |

Navy |

Navy is responsible for MK-99 sustainment, manning, and operations. |

|

|

Command and control |

Guam Command Center (GCC) |

MDA |

Air Force |

Air Force is responsible for the GCC facility. Components responsible for manning. |

|

Aegis Guam System |

MDA |

MDA/Navy |

MDA is responsible for software sustainment. Navy responsible for hardware sustainment, manning, and operations. |

|

|

Weapons |

Vertical Launch System (VLS) |

Navy |

Navy |

Navy is responsible for VLS sustainment, manning, and operations to include Standard Missile (SM)-3 and SM-6. |

|

SM-3 Missiles |

MDA |

MDA/Navy |

MDA retains responsibility for sustainment of SM-3. |

|

|

SM-6 Missiles |

MDA/Navy |

Navy |

Navy is responsible for sustaining Standard Missile SM-3 and SM-6. |

Source: GAO analysis of DOD documentation. | GAO‑25‑108187

Note: In a January 7, 2025, memo, the Deputy Secretary of Defense directed the MDA to cease development of one of the elements, the AN/TPY-6 radar, but to retain the currently-fielded panel as an experimental asset with potential to develop for operational use within the GDS in the future. This table omits information about the nature of the dispute over lead service responsibilities, which DOD identified as Controlled Unclassified Information.

DOD Does Not Have a Strategy for Transferring Sustainment Responsibilities to Lead Services

DOD does not have a strategy that includes a timeline and a plan for determining when and how the lead organization—the military services or MDA—will assume responsibility for operating and sustaining those elements. MDA officials noted that they will fund sustainment of the systems they are developing for Guam until they fully transfer operations and sustainment to the military services. Specifically, MDA officials anticipate funding operations and sustainment for GDS elements they deliver for the first 2 years of their deployment.

Army officials told us they were waiting for DOD to decide the lead organizations for operating and sustaining GDS elements before developing the Army’s plan for providing organization, training, personnel levels, and facilities for the GDS elements they will be responsible for operating and sustaining. According to another Army office, the Army has not decided on the training needed for service personnel supporting GDS or on how to ensure adequate personnel. DOD has proposed multiple military services to manage GDS, which makes developing a plan for operating and sustaining GDS particularly challenging. Specifically, DOD officials told us that this missile defense program will be the department’s largest and most complicated, presenting communication and planning challenges among the various DOD stakeholders.

The other military services noted they may have a role in sustaining GDS facilities and providing services to GDS personnel even for systems that they will not operate and sustain directly. Specifically, Air Force and Navy planners told us they likely will assist with providing security for missile defense sites on their bases and for some sustainment activities. Those officials stated they still need to formalize those responsibilities and funding arrangements between services in the Joint Memorandum of Agreement.

According to DOD Instruction 5000.91, the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment oversees the issuance and frameworks of system life-cycle management.[26] The instruction also notes that DOD component heads have responsibility for establishing the requirements, budget, and sustainment processes to support development, deployment, and operational use of weapon systems. DOD Directive-type Memorandum 20-002 directs MDA—in conjunction with the Secretaries of the military departments—to provide transfer agreements to a lead military department for the equipment.[27] Additionally, DOD Directive 5134.09 requires the MDA to create element transfer plans in coordination with the Secretaries of the military departments.[28]

JPO officials told us they initiated operational planning

in October 2024 ahead of the first expected delivery of GDS elements. However,

the military services and MDA may not have fully established requirements for

what they need for organization, training, personnel levels, and

facilities because there is no strategy for the transfer of systems. As a

result, DOD—that is, the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and

Sustainment, MDA, and the military services—risks delays in establishing GDS.

We have previously reported that MDA has repeatedly delayed transferring missile defense systems to the military services for their operation and sustainment, resulting in preparedness and funding challenges.[29] Specifically, we found that MDA was not meeting its requirement to transfer systems after they complete system development. As we reported in July 2020 and June 2022, delaying the transfer of missile defense systems—like the elements that compose GDS—could lead to uncertainty in how prepared the military services are to operate and sustain them, as well as to funding risks. Likewise, without establishing a strategy that includes a timeline and plan for the transfer of operation and sustainment responsibilities, the military services and MDA face preparedness and funding challenges. We omitted information from this paragraph about the GDS elements because DOD designated this information to be Controlled Unclassified Information.

Army Has Not Resolved Its Limited Installation Support in Guam ahead of Its Planned Increased Presence

The Army does not have sufficient installation support for its current and future presence in Guam. The Army has deployed and operated a THAAD battery with Task Force Talon for over 10 years. However, Army officials from Task Force Talon and the 38th Air Defense Artillery Brigade told us they have difficulty securing approvals from the Navy for temporary or permanent military construction at the Army’s site in Guam. Task Force Talon officials told us they are an operational unit without construction planners, so they rely on the Navy to provide those services. Specifically, Task Force Talon officials stated that when they plan for any military construction, they rely on the Navy for planning work such as environmental analyses.

This reliance has resulted in delays for approved construction work. For example, Task Force Talon officials told us that they received approval for construction of a temporary maintenance facility for equipment on site after a typhoon arrived in May 2023. Officials noted that they did not receive approval to begin the environmental work until January 2024.

The current condition of Army missile defense-related facilities on Guam are austere. We observed conditions at Task Force Talon’s site in Guam that presented risks to equipment and materiel, and negatively affected Army personnel assigned to the site. We omitted information from this paragraph that DOD designated as Controlled Unclassified Information; however, we observed several limitations:

· Equipment and parts storage. Task Force Talon officials told us they have limited storage space that is climate-controlled. During a typhoon in May 2023, the Army had to coordinate with the Marine Corps to find hangar space to protect the THAAD launchers and radar from damage, according to Marine Corps documentation and officials. Army officials noted that in some cases, they are having to leave spare parts unprotected outside. Task Force Talon personnel use containers on site for the storage of equipment and spare parts (see fig. 2). As a result, Task Force Talon officials told us they continually face challenges with corrosion of spare parts.

· Maintenance facilities. The Army does not have a dedicated maintenance facility for the deployment of its THAAD battery at Task Force Talon. We observed that Task Force Talon personnel used a temporary tarp, rather than a constructed facility, to protect vehicles undergoing maintenance (see fig. 3). We also observed one location on site where an Army vehicle stored on a grass field had leaked fluid into the soil. In response, the Army had to coordinate with JRM to bring a team to mitigate the environmental damage, according to Task Force Talon officials. Those officials also told us the May 2023 typhoon destroyed most of the maintenance gear they had on site, including their only wash rack used to clean equipment.

· Quality-of-life services. We heard significant concerns from Army personnel about the austere conditions of support services at Task Force Talon. Task Force Talon and 38th Air Defense Artillery Brigade officials told us that in 2023 they installed a latrine with running water and an ice machine on part of the site, firsts since the Army’s deployment to Guam in 2013. Those officials stated they were hoping to add those improvements to the other end of the site. Task Force Talon officials also noted that they have no drinkable water at their location, rely on bottled water, and have no plans to supply clean drinking water to the location.

We found that Army personnel currently deployed to Guam face morale challenges due to the austere conditions on site. An Army planner told us Task Force Talon has operated on a limited agreement with JRM for installation support, given the Army’s limited presence in Guam before GDS. Army officials also noted that they will require construction of additional facilities as the Army’s presence on Guam grows with the addition of new GDS elements distributed across multiple sites and bases on the island. With the arrival of additional Army personnel in Guam for GDS, Army officials told us their goal is to make Guam a duty station of choice.

According to JRM officials, the Army will rely on installation support from the Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps bases on Guam rather than establishing its own base. However, the Army will likely face challenges in advocating for construction priorities and coordinating installation support across multiple locations. The Air Force and Marine Corps both operate their own bases in Guam under JRM, and officials from both services noted it can be challenging to determine how to coordinate installation support with the Navy-led JRM. The Army has the additional challenge of coordinating with the Air Force, Marine Corps, and Navy considering that Army personnel will be operating from three different bases in Guam. For example, for GDS sites on Andersen Air Force Base, the Army may have to rely on the Air Force as the base lead for some installation support functions and on the Navy as the lead of JRM for other functions. For other GDS sites, the Army may have to coordinate with different military services for those same installation support functions.

An Army planner told us they will rely on lessons learned from the Marine Corps relocation to Guam, but they acknowledged that they are operating on a faster time frame than the Marine Corps. The Marine Corps will have had over 15 years of planning before the arrival of over 1,700 Marines to Guam by 2029. In contrast, the Army plans to bring additional soldiers to Guam after approximately 5 years of planning—from 2022 to 2027.

In anticipation of these challenges, the Army has taken some initial steps to improve installation support:

1. Establishing the Army Coordination Element–Guam in March 2022, which, according to officials, coordinates Army activities on Guam and in the immediate, surrounding region. Specifically, the Army delegated to this office the responsibility of managing the Army’s presence in Guam to assist with increasing operational requirements for the region, including the addition of GDS. This office also facilitates training, exercises, and engagements in Guam and the surrounding islands.

2. Signing JRM’s Joint Memorandum of Agreement in February 2024, which allows the Army to begin negotiating installation support services—security, fire protection, and personnel support services, among them. This agreement outlines how the Navy, as the lead of JRM, coordinates and funds installation support with each of the other military services operating in Guam.

3. Sending Army planners on temporary assignments to Guam in August 2024 to begin discussions of the Army’s needs for installation support in Guam. Among other topics, Army planners discussed facility sustainment, installation security, emergency management, and utilities. Army planners told us these discussions helped to identify some of the Army’s initial requirements for installation support but they would need to update the Joint Memorandum of Agreement to formalize agreements among the military services.

According to Army planners, while these steps are helpful, they are in the early stages of determining how the Army will operate within the joint base structure in Guam. First, Army planners told us the Army may have to provide personnel and funding to the Air Force, Marine Corps, and Navy to help support the Army’s presence at bases managed by those three services. Second, those officials said they will rely on temporary planners and engineers sent to Guam as the Army does not have a formal presence within JRM yet. Army officials told us they are not planning to permanently establish an organizational structure within JRM until Army personnel arrive with GDS. Army planners told us an organizational structure could include the Army contributing personnel to JRM to coordinate Army construction priorities and installation support or deploying a deputy base commander.

DOD’s Joint Basing Operating Guidance and Army Regulation 600-20 both clarify roles and responsibilities for DOD operations at joint bases.[30] Specifically, the Joint Base Operating Guidance identifies how each military service is to organize itself as a supported command to ensure appropriate representation and installation support in those environments.[31] The Army’s regulation also outlines the Army’s responsibility for ensuring it has appropriate representation for joint base discussions. Additionally, the regulation identifies that the Army should have a structure to prioritize and submit Army construction and facility sustainment at joint bases.

The Army’s Task Force Talon and future GDS personnel risk operating in austere conditions because the Army has not developed a long-term strategy for the Army’s organization as a supported command within JRM. In contrast to a strategy, according to Army planners, they have had some preliminary discussions on how to enhance Army representation in Guam and negotiate installation support across each base. However, they told us the Army has not determined how it will be organized within JRM once the Army’s presence grows in Guam. For example, Army planners noted that they are unsure if the Army will have a base commander, contribute personnel to JRM, or establish a formal support function within the region.

Without a strategy, the Army will lack full representation to coordinate construction priorities in the joint region and continue to have limited installation support for its future presence in Guam with the arrival of GDS personnel. As a result, the Army may continue to encounter delays in approvals of construction priorities as it relies on the Navy for planning work, like environmental analyses. The Army is also at risk of deploying personnel to Guam without adequate facilities or installation support services in place, including security of sites, fire protection, and emergency management at bases operated by three different military services in Guam.

DOD’s Plan for Supporting Future GDS Units in Guam is Incomplete

DOD Lacks Critical Information about GDS Personnel Requirements and Deployment Schedules

Since planning for GDS began in fiscal year 2022, DOD has not fully identified the required number of personnel or completed a deployment schedule for GDS units. In June 2023, the Deputy Secretary of Defense directed the Army, in coordination with the Joint Staff, to determine personnel requirements for GDS within 120 days, among other things.[32] In August 2024, Army officials told us they have not completed those personnel requirements. These officials attributed delays in providing those requirements to disputes over who will operate and sustain the GDS systems, as discussed above. Additionally, the services have not identified when they will relocate personnel to Guam in support of GDS by way of a deployment schedule.

According to a JRM briefing, DOD decision-makers need clear personnel stationing timelines and the linkage to facility/infrastructure requirements before they can plan for expansions of necessary support infrastructure.[33] Specifically, DOD officials stated that they need to know the number of GDS personnel to be deployed to Guam, the number of dependents accompanying personnel, and the locations of their housing.

In the absence of decisions on future personnel levels,

DOD organizations have developed their own distinct estimates for GDS

personnel. For example, JRM estimated the population growth of all DOD

personnel in Guam, including Army personnel supporting GDS, by

compiling data from various force projection plans.[34] Similarly, Defense Health Agency

personnel told us they generated growth estimates based on surgical staffing

needs.[35]

The two estimates vary significantly. Specifically, JRM estimated there will be

913 Army personnel in Guam by fiscal year 2028, but the Defense Health Agency

estimated growth to 4,464 Army personnel by that year.

Also, counting for the Marine Corps growth and GDS personnel, Naval Facilities Engineering Systems Command (NAVFAC) personnel anticipate a doubling of DOD personnel in Guam from approximately 10,000 in 2024 to 20,000 in 2033. Across the services, JRM expects a growth in active-duty personnel and dependents from 17,917 in fiscal year 2024 to 26,605 in fiscal year 2034, based on personnel estimates created in recent previous years.[36] The military services developed these estimates to determine the level of support services needed to meet population growth such as housing, education, medical care, and commissary services.

In October 2024, MDA issued a draft Environmental Impact Statement that identified preliminary numbers of the military personnel and their dependents, contractors, and civilian support workers for the operation and sustainment of GDS. MDA projects that DOD will need 805 personnel for GDS by calendar year 2027 with growth to 1,044 personnel by calendar year 2031. However, the Environmental Impact Statement notes uncertainty over the locations of life-support facilities, including unaccompanied personnel barracks, family housing, child and youth services, medical care facilities, and other base support facilities.

Further, senior military officials told us the draft

statement is just a benchmark for the military services, because the services

still need to validate and fund those requirements. According to a Joint Staff

official, construction on Guam is also delayed by environmental approval

requirements, such as Environmental Impact Studies at each site and National

Environmental Policy Act requirements. The official said these requirements

hinder military construction planning efforts and affect the funding schedule.

DOD Cannot Adequately Plan for Construction Needs without Identifying Personnel Requirements

In the absence of identified personnel requirements, DOD faces challenges to ensuring an adequate support infrastructure at installations in Guam to accommodate both Marine Corps personnel relocating from Okinawa and future GDS personnel.[37] Guam has limited space and capacity to support the expected growth in personnel and related installations and services. DOD faces significant challenges to ensuring GDS personnel and their families have sufficient housing, schools, medical care facilities, and commissaries. (For a summary of how GDS may affect the local community in Guam, see appendix II.) For example:

· Housing limited on base. Guam already faces a housing shortage for military personnel. DOD is in the process of developing a housing master plan, which will report on how the department will support housing needs of personnel deployed to Guam. We omitted information from this paragraph about challenges in providing military personnel with on-base housing, which DOD designated as Controlled Unclassified Information.

As of August 2024, GDS planners have expressed doubts about their ability to build housing on time. For example, a JRM briefing identified a need for two barracks projects that would support some Army personnel by fiscal year 2030. However, DOD has not programmed funding for the two projects.

· DOD schools nearing full capacity. Schools are approaching full capacity before the arrival of Marine Corps and GDS personnel. In February 2023, the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness issued a report examining the projected growth of the student population at DOD’s schools. As a key contributor to the report, the DOD Education Activity showed the student population rose from 1,735 to 2,650 across the military services, putting them near full capacity. However, the DOD Education Activity estimates that the four DOD schools currently on Guam will exceed capacity by fiscal year 2027 as more Marines arrive in Guam. To accommodate future population growth, the DOD Education Activity estimates that it would need to build four additional schools, construct temporary facilities, and convert existing facilities by fiscal year 2031, but those projects have not received funding. In October 2024, DOD Education Activity personnel told us they have an uncertain timeline for increasing school capacity, considering the lack of funding.

As of October 2024, DOD does not have an estimate for how GDS will affect the demand for schools on military bases. Specifically, DOD Education Activity’s analysis included only Marine Corps personnel relocating to Guam from Okinawa, given uncertain numbers of GDS personnel. Air Force and Navy officials in Guam stated that they expect the additional GDS personnel will put a burden on the capacity of DOD’s schools on base.

· Medical care facilities insufficient. A JRM briefing states that there are not enough medical personnel in Guam to staff medical treatment facilities without unduly degrading local capacity of civilian personnel on the island. To accommodate additional military personnel relocating to Guam, the Defense Health Agency estimates that DOD will need approximately 208 additional medical staff to support the increased population across four military medical treatment facilities.

However, a Defense Health Agency official told us the number of required medical personnel may change once DOD determines requirements for GDS personnel levels. Also, the October 2024 Environmental Impact Statement noted that the long-term increase of personnel in Guam for GDS could significantly affect the accessibility and availability of medical care throughout the island. DOD officials in Guam told us they have concerns about hospital capacity in Guam, particularly with a growing DOD presence on the island. Further, military service officials at every base in Guam told us they do not have enough medical staff on Guam to service military personnel. According to an Air Force official in Guam, DOD cannot depend on the local community to provide medical services, so the department will have to assess the capacity of DOD’s medical clinic and hospital in Guam to accommodate additional personnel.

· Commissary already in need of expansion. To accommodate the Marine Corps personnel relocating to Guam, the Defense Commissary Agency is developing two major expansions involving a commissary facility and a new central distribution center.[38] Specifically, the Defense Commissary Agency has plans to expand a commissary at one base, construct a new commissary at another base, and develop a new central distribution center. The Defense Commissary Agency developed its planned commissary expansions for population growth based on the planned personnel for the Marine Corps relocation.

These expansions do not account for GDS personnel. Defense Commissary Agency officials told us DOD has the expansions—and any other commissary projects—on hold until the military services provide accurate numbers for population growth. According to Defense Commissary Agency personnel, the addition of GDS personnel to Guam will further stress the capacity of existing commissaries. Further, according to Navy officials in Guam, there are issues with ensuring the commissaries are fully stocked due to high demand and supply chain challenges. The addition of GDS personnel to Guam will further stress the capacity of existing commissaries.

DOD policy states that national military objectives shall be accomplished with a minimum manpower that is organized and employed to provide maximum effectiveness and combat power.[39] In addition, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government notes that agencies should use quality information to achieve objectives.[40] That can include identifying data requirements, using relevant data from reliable sources, and processing the data into quality information.

DOD cannot fully plan for the infrastructure it needs to support future GDS personnel because the military services have not identified personnel requirements or completed deployment schedules for GDS. As a result, DOD cannot effectively plan for how the addition of GDS personnel deploying to Guam will affect the capacity of housing, DOD schools, medical care facilities, and commissaries. DOD has identified that those facilities are already facing capacity issues. As such, DOD will not know how much the addition of GDS personnel will exacerbate existing challenges with the support infrastructure.

Conclusions

As DOD continues its plans to expand missile defense in

Guam to counter evolving threats from China in the Indo-Pacific region, the

department has work remaining to ensure it sufficiently sustains and

supports GDS. DOD has established organizations to manage the deployment of GDS

and designated lead services for sustainment and operations. However, DOD lacks

a strategy to transfer responsibilities to their lead organizations. As a

result, DOD risks schedule delays for the deployment of GDS elements and incomplete

plans for organization, training, personnel levels, and facilities, among other

things. Moreover, although the Army officially joined JRM in February 2024, the

Army has not identified its long-term strategy to advocate for construction

priorities and installation support from the other military services. Without a

strategy, the Army may continue to face delays in approval of construction

projects and risks deploying additional personnel without installation support

services in place.

DOD also lacks information on personnel requirements, including fully how many GDS personnel it will deploy for GDS and when they will arrive in Guam. This information is critical for enabling DOD to plan for construction needs related to its support infrastructure. Without clear personnel requirements or deployment schedules, the services will not be able to adequately plan for necessary support systems, which will reduce service personnel readiness and may exacerbate existing infrastructure.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following three recommendations to the Secretary of Defense (we omitted a fourth recommendation, which we made in our classified report, because DOD classified the recommendation to be SECRET//NOFORN):

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment—in coordination with the Director of MDA and secretaries of the military departments—develops a strategy with a timeline and plan for the transfer of responsibilities for operating and sustaining GDS elements to each lead organization. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Secretary

of the Army—in coordination with the Commander of JRM, the Secretaries of the

Air Force and Navy, and the Commandant of the Marine Corps—

develops a long-term strategy for the Army’s organization as a supported

command at JRM. (Recommendation 2)

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the secretaries of the military departments determine the personnel requirements needed to operate and sustain GDS, including developing a deployment schedule for those personnel, to allow sufficient time for completing construction of necessary support facilities on Guam. (Recommendation 3)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to DOD for review and comment. DOD concurred with our recommendations, and provided technical comments for accuracy, which we incorporated as appropriate. With the exception of comments that DOD classified SECRET or designated as Controlled Unclassified Information, we have reprinted DOD’s comments in appendix IV.

In our draft report, we included a recommendation that the Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Deputy Secretary of Defense—in coordination with the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment, Director of the MDA, and secretaries of the military departments—determines lead organizations for the operation and sustainment of all of the GDS elements. After we provided our draft report for comment, DOD provided us documentation that the Deputy Secretary of Defense took this action in November 2024. We revised our draft report to reflect these designations and deleted the recommendation from the final report.

Additionally, DOD provided us a memorandum signed by the Deputy Secretary of Defense on January 7, 2025, that directed adjustments to the GDS architecture. We omitted information from our evaluation of this memo because DOD designated it as Controlled Unclassified Information. However, a DOD official told us that the decisions in the memo were not binding on the incoming administration. We clarified in both our earlier classified report, and in this publicly releasable version, that the GDS architecture we described was current as of August 2024. We summarize the adjusted architecture as reflected in the Deputy Secretary of Defense’s memorandum in appendix III.

We are providing copies of this product to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Defense, and to the Director, MDA. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at MaurerD@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix V.

Diana Maurer

Director, Defense Capabilities and Management

To obtain information for our review, we met with officials from the following organizations within the Department of Defense:

· Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment

· Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness

· Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy

· Office of the Director, Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation

· Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Energy, Installations, and Environment

· Missile Defense Agency

· Joint Integrated Air and Missile Defense Organization

· Defense Commissary Agency

· Department of Defense Education Activity

We also met with officials from the following offices within the military services:

· Assistant Secretary of the Army for Acquisition, Logistics, and Technology

· Headquarters, Department of the Army G-3/5/7

· Army’s Rapid Capabilities and Critical Technologies Office

· U.S. Army Aviation and Missile Command

· U.S. Army Space and Missile Defense Command

· U.S. Army Installation Management Command

· Office of the Commander, Navy Installations Command

We also conducted site visits to the following:

Hawaii

· U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, Camp H.M. Smith, Honolulu

· U.S. Army Pacific, Fort Shafter, Honolulu

· U.S. Pacific Fleet, Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam, Pearl Harbor

· 94th Army Air and Missile Defense Command, Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam, Pearl Harbor

· U.S. Naval Facilities Engineering Systems Command–Pacific, Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam, Pearl Harbor

Japan

· U.S. Forces Japan, Yokota Air Base

· 38th Army Air Defense Artillery Brigade, Sagami General Depot

· U.S. Naval Forces Japan, United States Fleet Activities Yokosuka, Yokosuka

· Naval Supply Fleet Logistics Center Yokosuka, United States Fleet Activities Yokosuka

Guam

· Joint Region Marianas, Naval Base Guam

· Joint Task Force-Micronesia, Naval Base Guam

· Army Coordinating Element-Guam, Santa Rita

· Naval Facilities Engineering Systems Command-Marianas, Naval Base Guam

· Army’s Task Force Talon, Andersen Air Force Base

· Air Force 36th Wing, Andersen Air Force Base

· Marine Corps Base Camp Blaz, Finegayan

· Naval Base Guam

Finally, we conducted a site visit with various Government of Guam offices at the Ricardo J. Bordallo Governor’s Complex, Hagatna, Guam, including the following:

· Community Defense Liaison Office

· Guam Department of Labor

· Guam Power Authority

· Guam Waterworks Authority

The Department of Defense (DOD) and the Government of Guam identified some potential effects an increased DOD presence may have on the local community in Guam. With the Guam Defense System (GDS) distributed across 16 sites throughout Guam, it may affect the following:

· Off-base housing. The Government of Guam has noted the effect of a growing DOD presence on local housing in Guam. In January 2020, Guam completed a study that reported how the military presence on the island significantly influences the island’s housing market and economy—both in the demand for housing units and the cost to rent a unit.[41] In addition to DOD personnel, Government of Guam personnel said they anticipate an influx of workers to the island to build the infrastructure needed to accommodate the Marine Corps and GDS personnel, putting additional strain on Guam’s available housing stock.

· Local power. To accommodate a growing demand for electricity on the island, the Government of Guam is overhauling the power grid, Guam officials told us. As one step, Navy officials stated that the Government of Guam is constructing a new power plant on the north end of the island. A December 2022 report on efforts to plan GDS site requirements stated that the GDS elements will rely on generators at each GDS element site as the primary source of power, given JRM personnel concerns about the reliability of local power. According to MDA officials, the Guam Command Center will rely on local power at Andersen Air Force Base with generators as a backup power source.

· Water and wastewater. DOD utilizes Guam’s civilian water and wastewater systems. According to Government of Guam officials, they have taken steps to improve the infrastructure after identifying deficiencies in a 2018 infrastructure improvement plan. Government of Guam officials noted that ageing water and wastewater infrastructure will need significant improvements to support growing demand on the island.

· Public schools. Government of Guam officials said the island schools are competing against DOD schools on base and consequently are losing resources and personnel. Specifically, they stated that the influx of DOD dependents can result in qualified educators choosing to work at DOD schools over Guam public schools.

· Other shared infrastructure. Typhoon Mawar, which hit Guam in May 2023, caused significant damage to Guam’s infrastructure, including both civilian and military structures. Additionally, Government of Guam officials noted that many roads are in poor condition and are likely unable to support additional capacity without improvements.

In a memo dated January 7, 2025, the Deputy Secretary of Defense directed the following changes to the GDS architecture. However, a DOD official told us that the decisions in the memo were not binding on the incoming administration. We omitted information from this appendix that DOD classified SECRET.

· Command and Control Integration: Accelerate key command and control (C2) integration activities, to include:

· Integrating Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) into the Army’s Integrated Battle Command System (IBCS), as defined in Joint Requirements Oversight Council Memo (JROCM) 23-008A. The Department of the Army and the Missile Defense Agency (MDA) shall integrate AN/TPY-2 measurement data into IBCS no later than 2030 and achieve full integration by 2033.

· Upgrading the Joint Track Management Capability (JTMC) bridge to address the full set of PRC missile threats to Guam and to achieve a Joint Tactical Integrated Fire Control (JTIFC) capability for coordinated battle management, combat identification, and electronic protection. The MDA shall complete these upgrades no later than 2029.

· AN/TPY-6: Other than system experimentation efforts, further development of the AN/TPY-6 radar shall be terminated. The MDA shall prioritize remaining Aegis Guam System development funds toward delivering minimum viable Aegis C2 and datalink capabilities to enable Standard Missile 6 (SM-6) engagements off remote tracks from AN/TPY-2 and LTAMDS over the JTMC bridge. The MDA shall retain the single AN/TPY-6 panel currently on-island, with all associated flight test equipment, and maintain it in its current form as an experimental asset, with potential to develop for operational use within the GDS architecture in the future.

GAO Contact

Diana Maurer at maurerd@gao.gov.

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact listed above, Kevin O’Neill (Assistant Director), Scott Bruckner (Analyst-in-Charge), Nicole Ashby, Ava Bagley, Dylan Colby, Michele Fejfar, Christopher Gezon, Amie Lesser, and Lillian Ofili made key contributions to this report.

Missile Defense: Actions Needed to Address Cyber Testing and Defense of Guam, GAO‑25‑106835SU (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 19, 2024).

Military Housing: DOD Should Address Critical Supply and Affordability Challenges for Service Members, GAO‑25‑106208 (Washington D.C.: Oct. 30, 2024).

Army Modernization: Actions Needed to Support Fielding New Equipment. GAO‑24‑107566. Washington, D.C.: July 15, 2024.

Missile Defense: Next Generation Interceptor Program Should Take Steps to Reduce Risk and Improve Efficiency. GAO‑24‑106315. Washington, D.C.: June 26, 2024.

U.S. Territories: Coordinated Federal Approach Needed to Better Address Data Gaps. GAO‑24‑106574. Washington, D.C.: May 9, 2024.

Military Readiness: Actions Needed for DOD to Address Challenges across the Air, Sea, Ground, and Space Domains. GAO‑24‑107463. Washington, D.C.: May 1, 2024.

Missile Defense: DOD Needs to Improve Oversight of System Sustainment and Readiness. GAO‑23‑105578. Washington, D.C.: June 7, 2023.

Missile Defense: Annual Goals Unmet for Deliveries and Testing. GAO‑23‑106011. Washington, D.C.: May 18, 2023.

Missile Defense: Better Oversight and Coordination Needed for Counter-Hypersonic Development. GAO‑22‑105075. Washington, D.C.: June 16, 2022.

Missile Defense: Acquisition Processes Are Improving, but Further Actions Are Needed to Address Standing Issues. GAO‑22‑105925. Washington, D.C.: May 11, 2022.

Missile Defense: Addressing Cost Estimating and Reporting Shortfalls Could Improve Insight into Full Costs of Programs and Flight Tests. GAO‑22‑104344. Washington, D.C.: February 2, 2022.

Missile Defense: Recent Acquisition Policy Changes Balance Risk and Flexibility, but Actions Needed to Refine Requirements Process. GAO‑22‑563. Washington, D.C.: November 10, 2021.

Missile Defense: Fiscal Year 2020 Delivery and Testing Progressed, but Annual Goals Unmet. GAO‑21‑314. Washington, D.C.: April 28, 2021.

Missile Defense: Observations on Ground-based Midcourse Defense Acquisition Challenges and Potential Contract Strategy Changes. GAO‑21‑135R. Washington, D.C.: October 21, 2020.

Missile Defense: Assessment of Testing Approach Needed as Delays and Changes Persist. GAO‑20‑432. Washington, D.C.: July 23, 2020.

2018 Pacific Disasters: Preliminary Observations on FEMA’s Disaster Response and Recovery Efforts. GAO‑20‑614T. Washington, D.C.: July 8, 2020.

Missile Defense: Lessons Learned from Acquisition Efforts. GAO‑20‑490T. Washington, D.C.: March 12, 2020.

Missile Defense: Further Collaboration with the Intelligence Community Would Help MDA Keep Pace with Emerging Threats. GAO‑20‑177. Washington, D.C.: December 11, 2019.

Missile Defense: Delivery Delays Provide Opportunity for Increased Testing to Better Understand Capability. GAO‑19‑387. Washington, D.C.: June 6, 2019.

Missile Defense: Air Force Report to Congress Included Information on the Capabilities, Operational Availability, and Funding Plan for Cobra Dane. GAO‑19‑68. Washington, D.C.: December 17, 2018.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]Missile Defense Agency, Enhanced Integrated Air and Missile Defense System on Guam: Environmental Impact Statement Project Information (May 2023).

[2]Department of Defense, 2022 Missile Defense Review (Oct. 27, 2022).

[3]Each THAAD launcher is equipped with capacity for eight interceptors, enabling Guam’s THAAD battery to hold up to 48 missiles at any one time.

[4]Threats include advanced cruise, ballistic, and hypersonic missile attacks.

[5]See Deputy Secretary of Defense Memorandum, Designation of Senior Official Responsible for Missile Defense of Guam (June 20, 2023); Deputy Secretary of Defense Memorandum, Designation of the Lead Senior Defense Official for Guam (Jan. 9, 2024).

[6]GAO, Missile Defense: Actions Needed to Address Cyber Testing and Defense of Guam, GAO‑25‑106835SU (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 19, 2024).

[7]GAO, Missile Defense: DOD Needs to Improve Oversight of System Sustainment and Readiness, GAO‑23‑105578 (Washington, D.C.: June 7, 2023). We made two recommendations in that report: for DOD to develop comprehensive guidance for oversight of missile defense sustainment and for MDA to report missile defense readiness data. As of November 2024, both recommendations remain open, although DOD stated that it intends to update readiness data on a semiannual basis.

[8]H.R. Rep. No. 118-125, at 107 (2023).

[9]GAO, Missile Defense: DOD Faces Support and Coordination Challenges for Defense of Guam, GAO‑25‑107116C (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 28, 2025).

[10]DOD Instruction 5000.91, Product Support Management for the Adaptive Acquisition Framework (Nov. 4, 2021); Directive-type Memorandum 20-002, Missile Defense System Policies and Governance (Mar. 13, 2011) (incorporating change 4, Feb. 20, 2024); and DOD Directive 5134.09, Missile Defense Agency (Sept. 17, 2009).

[11]DOD Directive 1100.4, Guidance for Manpower Management (Feb. 12, 2005); GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO‑14‑704G (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 2014).

[12]For purposes of this report, we refer to the joint base structure of JRM as an “installation” or “joint base” and the service-managed components as “bases” for simplicity. Specifically, the Andersen Air Force Base, Marine Corps Base Camp Blaz, and Naval Base Guam are bases all operating under one installation—JRM.

[13]Under the National Environmental Policy Act, an agency generally must complete an environmental impact statement in every recommendation or report on proposals for legislation and other major federal actions significantly affecting the quality of the human environment. See 42 U.S.C. § 4332.

[14]GAO, Military Housing: DOD Should Address Critical Supply and Affordability Challenges for Service Members, GAO‑25‑106208 (Washington D.C.: Oct. 30, 2024).

[15]Some GDS elements may be deployed at Marine Corps Base Camp Blaz, but DOD does not expect the Marine Corps to have a role in operating or sustaining any of the GDS elements.

[16]Additionally, the Army intends for the JPO to manage a wide range of responsibilities for GDS, including system engineering, business management, logistics, test and evaluation, and construction coordination, among other things.

[17]Of the proposed 129 personnel, the Army identified 12 military, 89 civilian, and 28 contractor personnel.

[18]Specifically, the JPO has six military, one civilian, and four contractors as of September 2024. These personnel include some of the proposed program manager and engineer positions.

[19]DOD, Joint Region Marianas Memorandum of Agreement (Feb. 2, 2024) (incorporates changes 1 through 7).

[20]Specifically, the Air Force manages Andersen Air Force Base, the Marine Corps manages Marine Corps Base Camp Blaz, and the Navy manages Naval Base Guam.

[21]The 10 topics discussed each month are (1) the synchronization tool, which is intended to help prioritize military construction in Guam; (2) medical care; (3) accompanied assignments; (4) roads; (5) real estate initiatives; (6) community support; (7) warehousing; (8) utilities; (9) environmental factors; and (10) housing. This working group also reports to another senior-level installation working group, known as the Senior Leader Installation Council.

[22]Deputy Secretary of Defense Memorandum, Designation of the Lead Senior Defense Official for Guam (Jan. 9, 2024).

[23]In a January 7, 2025, memo, the Deputy Secretary of Defense directed the MDA to cease development of one of the elements, the AN/TPY-6 radar, but to retain the currently-fielded panel as an experimental asset with potential to develop for operational use within the GDS in the future.

[24]Specifically, the seven elements were the (1) Army Navy/Transportable Radar Surveillance and Control Model 6, (2) AEGIS Guam System, (3) Guam Command Center, (4) Mark 99 Illuminator, (5) SM-3 interceptor, (6) SM-6 interceptor, and (7) Vertical Launch System.

[25]According to DOD officials, the land-based Aegis Guam System is fundamentally different from the AEGIS Ashore System deployed in Europe.

[26]DOD Instruction 5000.91, Product Support Management for the Adaptive Acquisition Framework (Nov. 4, 2021).

[27]Directive-type Memorandum 20-002, Missile Defense System Policies and Governance (Mar. 13, 2011) (incorporating change 4, Feb. 20, 2024). This memorandum expired on May 31, 2024.

[28]DOD Directive 5134.09, Missile Defense Agency (Sept. 17, 2009).

[29]GAO, Missile Defense: Assessment of Testing Approach Needed as Delays and Changes Persist, GAO‑20‑432 (Washington, D.C.: July 23, 2020); Missile Defense: Better Oversight and Coordination Needed for Counter-Hypersonic Development, GAO‑22‑105075 (Washington, D.C.: June 16, 2022).

[30]Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Energy, Installation, and Environment, Joint Basing Operating Guidance (Aug. 18, 2022); Army Regulation 600-20, Army Command Policy: Personnel-General (July 24, 2020).

[31]At a joint base, there is a military service that acts as the lead command to coordinate all installation support functions for that base. Every other military service is a supported command, therefore relying on the lead command for those functions.

[32]The Army’s due date of 120 days after June 20, 2023, would have been October 18, 2023. See Deputy Secretary of Defense Memorandum, Designation of Senior Official Responsible for Missile Defense of Guam (June 20, 2023). This policy also states that the Army must generate personnel requirements, as well as doctrine, organization, training, materiel, facilities, and sustainment requirements to inform the Missile Defense Executive Board, Defense Acquisition Board, the Defense of Guam Integrated Acquisition Portfolio Review, and DOD’s Program Budget Review processes.

[33]JRM, Guam Installation and Community Support Work Group (June 20, 2024).

[34]Specifically, JRM compiled data from the 2015 JRM Manpower Semi-Annual Data Call, the Fiscal Year 2024 Pre-Final Guam DOD Land Use Study and pending personnel data from the Army and U.S. Marine Corps. JRM also estimated dependent numbers based on a standard ratio. None of these force generation numbers were generated specifically for GDS.

[35]Defense Health Agency personnel told us they prepared these population estimates around June 2023 based on each of the service’s identified needs.

[36]JRM, Guam Installation and Community Support Work Group (June 20, 2024). According to NAVFAC, A DOD population of 20,000 personnel is roughly equal to peak personnel levels in the 1990s but with a significantly reduced military footprint.

[37]DOD personnel told us they expect at least 5,000 Marines and their dependents to deploy to the island from Okinawa. By comparison, according to NAVFAC personnel, the current population of Guam is about 174,000 people.

[38]Specifically, the new commissary on Andersen Air Force Base would replace a facility built in 1955. The Defense Commissary Agency has nearly completed the commissary’s design, but construction is delayed until after funding is allocated.

[39]DOD Directive 1100.4, Guidance for Manpower Management (Feb. 12, 2005).

[41]SMS Research and Marketing Services (prepared for Guam Housing and Urban Renewal Authority), Guam Housing and Needs Assessment (Jan.16, 2020).