TEMPORARY ASSISTANCE FOR NEEDY FAMILIES

Actions Needed to Improve HHS Oversight

Statement of Jeff

Arkin, Director, Strategic Issues;

Seto J. Bagdoyan, Director, Forensic Audits and Investigative Service; James R.

Dalkin, Director,

Financial Management and Assurance; and Kathryn

A. Larin, Director, Education, Workforce, and Income Security

Before the

Subcommittee on Work

and Welfare, Committee on Ways

and Means, House of Representatives

For Release on Delivery Expected at 2:00 p.m. EDT

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Jeff Arkin at arkinj@gao.gov, James R. Dalkin at dalkinj@gao.gov, Seto J. Bagdoyan at bagdoyans@gao.gov, or Kathryn A. Larin at larink@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-108205, a testimony before the Subcommittee on Work and Welfare, Committee on Ways and Means, House of Representatives

TEMPORARY ASSISTANCE FOR NEEDY FAMILIES

Actions Needed to Improve HHS Oversight

Why GAO Did This Study

The federal TANF block grant provides support to millions of low-income individuals and families. States are also required to contribute toward TANF spending and collectively spend approximately $15 billion of their own funds each year. States have increasingly shifted spending from assistance to non-assistance services. HHS oversees TANF, including by collecting state expenditure data, monitoring resolution of states’ TANF single audit findings, and assessing the risk of TANF fraud.

This statement summarizes GAO’s key findings from recent work related to (1) states’ reporting on TANF expenditures; (2) states’ use of TANF to provide child welfare services; (3) states’ use of data on job training and other services funded by TANF; (4) the timeliness of state TANF single audit reports and the extent of unresolved TANF single audit findings; and (5) TANF fraud risk management.

This statement is primarily based on five GAO reports

issued between December 2024 and April 2025

(GAO-25-107235, GAO-25-107290, GAO-25-107226, GAO-25-107291, and GAO-107467). Detailed

information on the objectives, scope, and methodology can be found within each

report. HHS provided technical comments, which we incorporated, as appropriate.

What GAO Recommends

GAO made 13 recommendations to HHS and one to Congress to improve TANF oversight. As of April 2025, the recommendations are open. Fully addressing the recommendations would enhance HHS’s oversight efforts and future decision-making on TANF.

What GAO Found

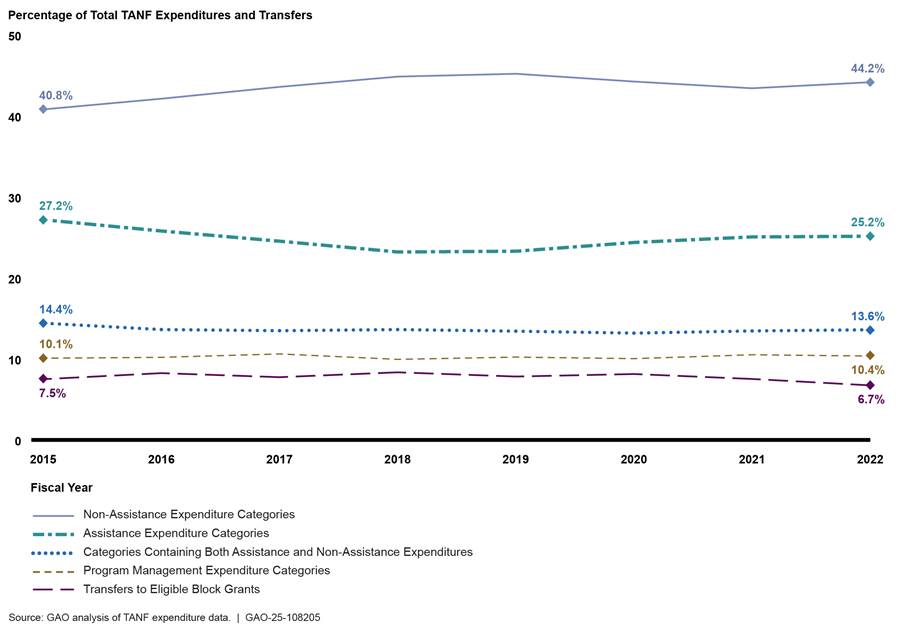

Administered by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) block grant annually provides $16.5 billion to states. Nationwide, state spending on TANF “non-assistance” services—such as job training and child welfare services—increased as a percentage of total TANF spending from fiscal year 2015 through fiscal year 2022 (from 40.8 to 44.2 percent). During that period, “assistance” spending, including cash payments to needy families, decreased as a percentage of total spending (from 27.2 to 25.2 percent).

GAO recently identified various ways that HHS could improve TANF oversight.

· Requiring states to report additional data on TANF expenditures could strengthen HHS's oversight of funds, potentially including oversight of improper payments. In December 2024, GAO found that states' reporting of TANF expenditures did not include detailed information on certain key aspects, such as information on planned non-assistance spending. In April 2022, GAO also recommended that Congress consider providing HHS authority to require states to report data to enable HHS to estimate and report on improper payments for TANF.

· Requiring states to report more data on TANF expenditures could also help to better reflect the amount of federal funds spent on child welfare. In April 2025, GAO found that, nationwide, states spent about $23.5 billion in TANF funds for child welfare purposes from fiscal year 2015 through fiscal year 2022. The amount of TANF funds states spent on child welfare is likely higher than HHS data show, according to selected states.

· Facilitating information sharing among states could help states improve outcome tracking and oversight. In February 2025, GAO reported that, while HHS does not have authority to collect data on those served with TANF non-assistance funds, officials from selected states generally said that they collected and used a variety of such data. Selected state officials said they would like to improve their use of these data.

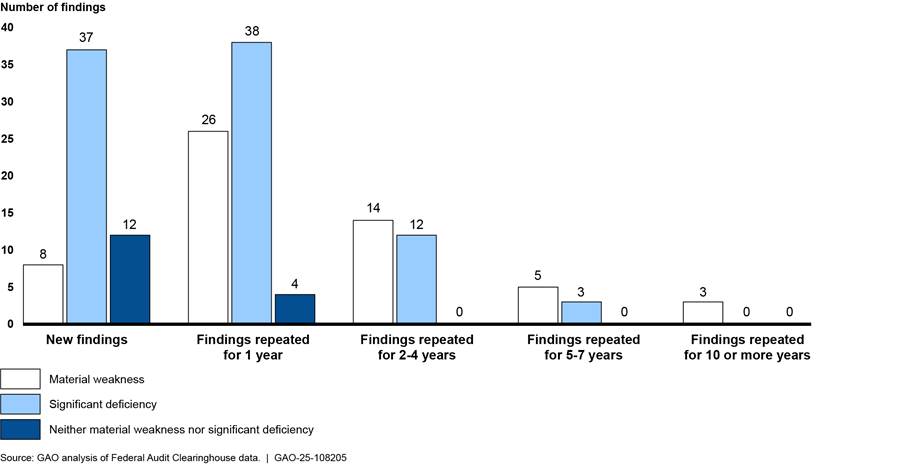

· Tracking and measuring the resolution of single audit actions could help identify and resolve repeat issues. States and other entities that spend above a certain amount in federal awards (e.g., TANF award funds) in each year are required to undergo an audit of their financial statements and federal awards, known as a “single audit.” In April 2025, GAO identified 37 states with a total of 162 TANF audit findings, including persistent and severe findings in their single audit reports. Additionally, some of these findings involved deficiencies that could lead to improper payments. Moreover, 37 of the findings repeated for 2 or more years, and some remained unresolved for over a decade.

· Fully assessing fraud risks consistent with leading practices would better position HHS to effectively and efficiently manage them. In January 2025, GAO found that HHS's processes for assessing fraud risks were not fully consistent with leading practices, including assessing or determining key aspects of fraud risks.

Chairman LaHood, Ranking Member Davis, and Members of the Subcommittee:

Thank you for the opportunity to discuss our work on the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) block grant. Since 1996, TANF has provided $16.5 billion annually in federal funding to states to assist millions of low-income individuals and families.[1] In addition, states are required to contribute their own funds to TANF-related activities, collectively spending approximately $15 billion annually.

At the federal level, the Office of Family Assistance, within the Department of Health and Human Services’s (HHS) Administration for Children and Families (ACF), oversees and administers TANF. HHS’s responsibilities include reviewing state TANF plans outlining how each state intends to run its TANF program, collecting and publishing state expenditure data, monitoring resolution of annually required audit findings related to TANF, and managing TANF fraud risks.

For their part, states have substantial flexibility and autonomy to determine how to allocate federal TANF funds. States are generally allowed to spend TANF funds in any manner that is reasonably calculated to meet one of TANF’s four purposes.[2] States may use TANF funds to provide direct cash assistance to meet a family’s ongoing basic needs. Additionally, states may use TANF funds to provide other services, called “non-assistance” services, such as work-related, education, and training activities; child care; and child welfare services.[3] As we have previously reported, in accordance with TANF’s flexibility, states have increasingly shifted spending from cash assistance to non-assistance services.[4]

We recently issued a series of reports related to TANF spending and oversight.[5] Our work identified several issues and, since December 2024, we have made 13 recommendations to HHS and one matter for congressional consideration to improve TANF oversight, all of which remain open as of April 2025 (see app. I).

Our remarks today summarize key findings and recommendations from our recent work related to:

1. trends in TANF expenditures, transfers, and unspent funds;

2. states’ reporting on TANF expenditures;

3. states’ use of TANF and other federal funds to provide child welfare services;

4. states’ use of data on job training and other services funded by TANF;

5. the timeliness of state TANF single audit report submissions to the Federal Audit Clearinghouse and the extent of unresolved TANF single audit findings;[6] and

6. TANF fraud risk management.

This statement is based on reports we issued between December 2024 and April 2025 reviewing HHS’s efforts to oversee TANF. To conduct the work on which this statement is based, we analyzed state TANF expenditure data from fiscal year 2015 through 2022 (the most current data available at the time of our data analysis), TANF state single audit findings, and adjudicated court cases involving TANF fraud. We also conducted site visits to several states and interviewed state and local officials in state TANF agencies and other agencies that received TANF funds. Detailed information on the objectives, scope, and methodology of this work can be found within each report. HHS provided technical comments on this statement, which we incorporated, as appropriate.

We conducted the work on which this statement is based in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

State Non-Assistance Spending and Unspent Funds Increased from 2015 to 2022

TANF expenditures generally fall into two categories: assistance and non-assistance. In December 2024, we reported that, nationwide, state spending on TANF non-assistance services—such as work, education, and training activities—increased as a percentage of total TANF spending from fiscal year 2015 through fiscal year 2022 from 40.8 to 44.2 percent.[7] During that period, assistance spending, including cash payments to needy families, decreased as a percentage of total spending from 27.2 to 25.2 percent (see fig. 1).

Figure 1: Change in Percentages of Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Expenditures and Transfers by Category from Fiscal Year 2015 through Fiscal Year 2022

Notes: Transfers to other block grants includes transfers to the Child Care and Development Fund or the Social Services Block Grant. States may transfer up to 30 percent of their federal TANF award to the Child Care and Development Fund and up to 10 percent of their federal TANF award to the Social Services Block Grant. Combined transfers to these two block grants cannot exceed 30 percent of the state’s annual federal TANF grant. Program management includes administrative expenses incurred in providing TANF benefits and services. Certain administrative costs may not exceed 15 percent of a state’s total expenditures.

Interactive graphic GAO-25-107235.

This decrease in assistance spending is a continuation of a trend prior to 2015. In 2012, we reported that 77 percent of TANF funds expended (not including transfers) were spent on assistance in fiscal year 1997. By fiscal year 2011, that amount had decreased to 36 percent of TANF funds expended.[8]

For more information on state-level TANF spending from fiscal year 2015 through fiscal year 2022, and to compare specific state spending to U.S. total spending, see our interactive graphic.

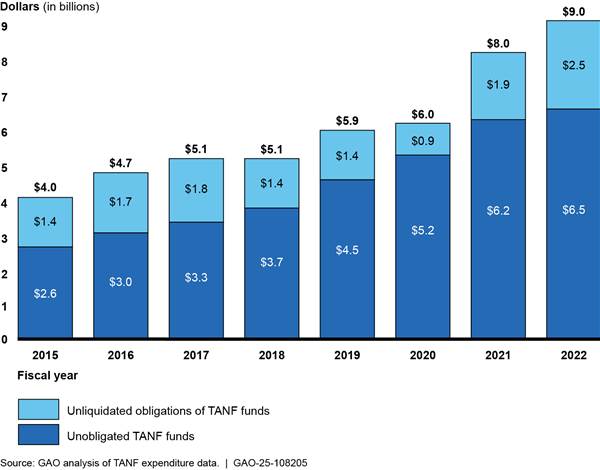

Federal annual TANF funds do not expire, and states can carry them over indefinitely for use in future fiscal years. From fiscal year 2015 through fiscal year 2022, total federal TANF funding carried over by states as unspent funds increased from $4 billion to $9 billion, as shown in figure 2.

Figure 2: Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Total Unspent Balances by All States, Fiscal Year 2015 through Fiscal Year 2022

Note: Under Department of Health and Human Services regulations, states use two categories to report on the status of their unspent TANF funds: (1) unobligated balances, which represent funds not yet committed for a specific expenditure by a state; and (2) unliquidated obligations, which represent funds states have committed but not yet spent. The sum of unobligated TANF funds and unliquidated obligations of TANF funds in the figure may not equal total unspent funds due to rounding.

This increase is the result of states, overall, spending fewer of their federal TANF funds during that period. As we reported in December 2024, of the six states with unspent funds in fiscal year 2022 that we selected for review, five of these states attributed their TANF unspent balances to subgrantees underspending their obligated funds.[9] Some selected states prioritized budgeting and spending other time-limited federal funding, such as COVID-19 relief funds, before using TANF funds.

HHS’s Existing Controls and Authorities for TANF Reporting Limit Oversight of State Spending

States are required to file various reports on their TANF expenditures with HHS. For example, for certain types of expenditures, states are required to submit annual narrative reports on the types and amounts of benefits provided for certain target populations. However, we found that based on reporting documentation in March 2024, seven states (out of 31 whose reported expenditures required narrative explanations) were missing or had incomplete narratives for fiscal year 2022. HHS officials told us that the agency is aware of missing narrative reports and has processes to monitor state reporting. However, these controls have not effectively ensured that states are providing the required narratives to support their expenditures. In December 2024, we recommended that HHS design control activities to help ensure states are submitting complete narrative data in their expenditure reporting. HHS agreed with this recommendation and noted that it will continue to improve on its monitoring and training efforts to ensure timely submission of required reporting.

In addition, states’ existing reporting does not include detailed information on aspects of TANF expenditures, such as information on planned non-assistance spending or on subgrantees that administer TANF-funded programs. HHS has indicated its oversight of states’ use of TANF funds is constrained by its limited statutory authority.[10] While current law limits what information HHS can collect from states, HHS could identify additional reporting requirements within its existing statutory authority to enhance the completeness of states’ reporting. Requiring that states report additional expenditure information could strengthen HHS oversight, potentially including that of improper payments, and guide future decision-making on TANF.

In December 2024, we recommended that HHS review TANF reporting requirements and forms and make appropriate changes to enhance reporting on use of TANF funds. HHS agreed with this recommendation and said that it would review reporting forms to improve the quality and comprehensiveness of TANF data within its statutory authority. Reviewing its current reporting requirements within its existing authorities and making any appropriate changes could help ensure the information HHS requires from states is adequate for its oversight purposes.

HHS officials told us that expanded statutory authority could potentially allow them to collect more detailed expenditure information, including on subrecipients of TANF funds. In its fiscal year 2024 and 2025 budget requests for the Administration for Children and Families, HHS included a legislative proposal requesting enhanced authority from Congress to collect more comprehensive data on TANF.

In December 2024, we recommended that Congress consider granting HHS the authority to collect from states specific additional information needed to enhance HHS’s oversight authority, such as information on planned and actual TANF non-assistance expenditures beyond what is provided for in the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996. By granting HHS authority to collect information related to states’ use of non-assistance funds and other data as appropriate, Congress could enhance HHS’s ability to monitor and ensure more oversight of billions of TANF dollars.

We previously reported on other ways to improve TANF oversight. In 2012, we recommended that Congress consider ways to improve reporting and program performance information so that it encompasses the full breadth of states’ uses of TANF funds.[11] Congress took some initial steps to reform TANF in 2016, however, no legislation was passed, and no changes to the reporting requirements were made.[12] In April 2022, we reported that HHS said that it does not have the authority to obtain information to estimate or report improper payment amounts for TANF. We recommended that Congress consider providing HHS the authority to require states to report the data the agency needs to estimate and report on improper payments for TANF.[13] As of April 2025, no relevant legislation has been introduced. See appendix I, table 3 for more information.

TANF Is a Key and Flexible Source of Child Welfare Funding for Some States

One key area for which states may use TANF funds is on child welfare—that is, activities to help ensure that children have safe and permanent homes.[14] TANF spending on child welfare may include payments to caregivers of children in foster care and services to prevent or address child abuse and neglect. These services may include parent education and training, family or individual counseling, and substance use assessment and treatment.

As we state in our April 2025 report, from fiscal years

2015 through 2022, the 50 states and the District of Columbia collectively

spent about $23.5 billion in federal and state TANF funds for child welfare

purposes.[15]

We also found that in fiscal year 2022, states varied in the percentage of

state and federal TANF funds they spent on child welfare (see table 1).

Table 1: Percentage of Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Funds Spent on Child Welfare, by Number of States, Including the District of Columbia in Fiscal Year 2022

|

Range of reported percentages of TANF funds spent on child welfare |

Number of

states |

|

No spending |

5 |

|

1 to 20 percent |

32 |

|

21 to 40 percent |

7 |

|

41 to 60 percent |

4 |

|

More than 60 percent |

3 |

Source: GAO analysis of TANF expenditure data. | GAO‑25‑108205

The amount of TANF funds that states spent on child welfare is likely higher than the HHS data show. Officials we interviewed in two of the five selected states we reviewed for our April 2025 report said they reported some child welfare-related expenditures in TANF categories that are not exclusively devoted to child welfare.[16] Implementing our previously discussed recommendation for HHS—that it review and improve its TANF-related data collection efforts—could help give HHS a better understanding of how states are using TANF funding to support child welfare.[17]

Our April 2025 report compares states’ use of TANF for child welfare to their use of two funding streams authorized by the Social Security Act. Referred to as Title IV-E and Title IV-B, they are the two largest sources of federal funding dedicated to child welfare. Similar to TANF, Title IV-E and Title IV-B can be used for payments to caregivers for children in foster care and services to prevent and address child abuse and neglect.[18] The amount states spent on TANF for child welfare purposes from fiscal years 2015 through 2022—$23.5 billion—was less than Title IV-E spending, but more than Title IV-B spending.[19]

Officials in the selected states told us their use of TANF, Title IV-E, and Title IV-B funds was driven by the eligibility requirements for each funding source and how the funds are distributed. Specifically, officials said they first looked to Title IV-E to fund child welfare payments and services, because states are entitled to reimbursement for a portion of all costs that meet Title IV-E eligibility requirements.[20] Officials we interviewed in four of the five selected states said that their agencies used TANF and Title IV-B to cover child welfare costs that were not eligible for Title IV-E reimbursement. These officials also noted that TANF and Title IV-B offer more flexibility than Title IV-E in how the funds can be spent and what families can be served.

Selected States Reported Challenges Using Data on Certain TANF Non-Assistance Services and Said HHS Could Facilitate More Information Sharing Among States

As described in our February 2025 report, while HHS does not have authority to collect data on individuals and families served with TANF non-assistance funds, officials from seven selected states generally reported collecting such data.[21] Specifically, state officials generally told us they collected a variety of demographic, participation, and outcome data on those who receive services supported by TANF non-assistance funds. State officials said that they used these data for a variety of purposes, including to make eligibility determinations, monitor program performance, and adjust the delivery of TANF non-assistance services.

Although states collect and use data for a variety of purposes, officials in six of the seven selected states told us they had encountered a range of challenges using data on those served with TANF non-assistance funds. As a result, state officials were sometimes constrained in their ability to assess participant outcomes and whether services were provided effectively.

For example, officials from one state’s TANF agency said that because TANF data existed in multiple data systems within their agency, it was difficult for them to match data on individuals and service providers. Moreover, their agency received data from three other state agencies, each operating its own data system, further complicating the TANF agency’s ability to use data collected to track participant experiences across programs. Officials in this state said that it was challenging to measure participant outcomes and to hire qualified personnel who had the needed expertise to work with performance data.

Officials in other states described challenges using data to ensure non-assistance funds were being used effectively. For example, officials in one state said their service providers varied in the extent to which they provided data on their job placement and retention rates, limiting the state’s ability to determine the extent to which non-assistance funds achieved the purposes of TANF.

Officials in selected states expressed an interest in learning from one another to improve their efforts to use data on those served with TANF non-assistance funds. Specifically, officials from four states told us that they would benefit from the opportunity to share promising practices related to TANF non-assistance data with other states. This could include using data analysis to improve service delivery, access, or accountability.

HHS told us that because TANF is a block grant with relatively few requirements compared to other federal programs, the agency had not specifically focused on providing support to states on how to use non-assistance data. Based on TANF’s statutory framework, HHS officials told us they had prioritized state flexibility in administering TANF non-assistance funds. As a result, HHS officials said that they were unaware of the interest that state officials had in improving their capacity to use non-assistance data.

In our February 2025 report, we recommended that HHS facilitate information sharing among state TANF agencies on promising practices for using data on those served with TANF non-assistance funds.[22] HHS agreed with our recommendation and noted that it would integrate conversations about these data in its regular peer-to-peer learning opportunities among state TANF agencies. In addition, the agency noted it planned to include topics related to data quality and analysis in forums such as regional and national conferences and technical assistance learning opportunities. By taking these steps, HHS will be better positioned to help states improve outcomes of low-income individuals and families and provide greater assurance that services provided with non-assistance funds are aligned with TANF purposes.

HHS Has Not Implemented Procedures to Conduct Effective Oversight of TANF Single Audit Findings

As the federal awarding agency, HHS is responsible for overseeing states’ TANF assistance and non-assistance expenditures. The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) guidance requires HHS to ensure that states submit single audit reports in a timely manner.[23] A single audit can identify deficiencies, called audit findings, in the award recipient’s financial reporting and related controls, including their compliance with certain provisions of laws, regulations, contracts, or grant agreements that have a direct and material effect on each of its major federal award programs. Single audits also review the recipient’s internal controls over compliance for such programs. Findings from single audit reports can also help federal agencies, such as HHS, identify fraud risks. HHS is required to follow up on audit findings to ensure that states take appropriate and timely corrective actions.

In our April 2025 report, we identified 37 states with, collectively, 162 TANF audit findings in their single audit reports.[24] Fifty-six of these findings were categorized as a material weakness—the most severe category of audit findings—which can indicate critical risks and issues in a federal program. Thirty-seven of the 162 audit findings repeated for 2 or more years, and some findings remained unresolved for more than a decade (see fig. 3).

Figure 3: Temporary Assistance for Needy Families Single Audit Findings and Years Repeated, as of April 30, 2024

We reviewed HHS’s procedures and found that the agency did not have effective procedures or execution to help states resolve TANF findings, issue management decisions, and impose timely penalties. HHS recently revised its procedures to help determine its effectiveness in helping states resolve these findings. However, HHS officials from the Administration for Children and Families (ACF) operating division stated that implementing such procedures is at their discretion. Specifically, we found:

· HHS does not measure its effectiveness in helping states resolve TANF single audit findings. ACF has not updated its single audit resolution standard operating procedures to determine their effectiveness in resolving TANF single audit findings. Specifically, its procedures did not include steps to track and measure the effectiveness of its actions to help states resolve TANF single audit findings. We found that many states had single audit TANF findings that repeated for 2 or more years and that some findings remained unresolved for over a decade. Tracking and measuring the effectiveness of its single audit resolution actions could help ACF identify repeat single audit issues on the TANF program, such as a lack of internal controls that could lead to improper payments, and could help ACF determine its effectiveness in helping states resolve these findings.

· HHS does not issue timely management decisions to states. According to HHS’s Audit Tracking Analysis System, from 2018 through 2023 HHS issued 23 (approximately 8 percent) of its 279 management decisions in response to TANF findings within 6 months of the Federal Audit Clearinghouse’s acceptance of states’ single audit reports as required by OMB’s Uniform Guidance and HHS’s related regulations.[25] HHS issued 70 of the remaining management decisions after the required 6-month time frame and, as of April 2024, had not issued the remaining 186 management decisions. When the awarding agency delays issuing a management decision to the award recipient, it may, in turn, delay initiating corrective action, potentially resulting in repeat findings in subsequent single audits.

· HHS does not have sufficient procedures to impose enforcement mechanisms on states not meeting TANF program requirements. HHS has established enforcement mechanisms (such as imposing penalties on or alternatively obtaining a corrective compliance plan) for states when they do not meet program requirements. However, these procedures do not include time frames to issue or enforce penalties, and as such, are not effective for ensuring that the penalties are imposed in a timely manner or at all. We identified instances in which HHS could have imposed a penalty or obtained a corrective compliance plan from a state but did not. Further, HHS did not provide documentation during our review of its determination not to impose a penalty. By establishing and documenting specific procedures for imposing penalties on states, or alternatively obtaining corrective compliance plans from states that are not meeting TANF program requirements, HHS could enhance its oversight. This includes encouraging states to resolve audit findings in a timely manner; to comply with certain federal legal requirements (from laws, regulations, and the terms and conditions of federal awards); and to reduce the likelihood of improper payments.

In our April 2025 report, we made three recommendations to HHS to strengthen its oversight of TANF single audit findings. Specifically, we recommended that HHS (1) revise and implement procedures to track and measure the effectiveness of audit resolution actions, (2) issue management decisions timely, and (3) impose penalties or obtain corrective compliance plans for states that are not meeting TANF program requirements.

HHS concurred with one of our three recommendations, partially concurred with one, and disagreed with one. Specifically, HHS agreed with and stated it planned to implement the recommendation to issue management decisions within the required 6-month time frame in accordance with OMB’s Uniform Guidance and HHS’s related regulations. HHS did not fully agree with the remaining two recommendations but stated it planned to revise audit resolution procedures to include steps to track and measure the effectiveness of actions to help states resolve TANF single audit findings. HHS also plans to develop and implement additional procedures to timelier evaluate whether to impose penalties. Fully addressing all of these recommendations would enhance HHS’s oversight of TANF single audit findings.

HHS Identified and Assessed TANF Fraud Risks, but Its Processes Are Not Fully Consistent with Leading Practices

We reported in January 2025 that HHS officials used sources such as states’ single audit reports and court cases to identify and assess 21 TANF fraud risks.[26] Specifically, in July 2024, HHS completed its first TANF fraud risk assessment using its Fraud Risk Assessment Portal.[27] We categorized these 21 fraud risks into nine broad categories, as reflected in figure 4.

Figure 4: Categories GAO Identified That Describe the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Fraud Risks Identified and Assessed by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

However, HHS’s process for assessing TANF’s fraud risks is not fully consistent with leading practices for fraud risk management. GAO’s A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs (Fraud Risk Framework) includes a comprehensive set of leading practices that serve as a guide for federal programs, like TANF, to use when developing or enhancing efforts to combat fraud in a strategic, risk-based manner.[28] The objective of fraud risk management is to facilitate a program’s mission and strategic goals by ensuring that taxpayer dollars and government services serve their intended purposes.

Specifically, we found, contrary to leading practices, HHS does not:

· Have clear guidance or procedures on planning and conducting regular TANF fraud risk assessments. HHS has not established clear guidance or procedures related to planning and conducting regular TANF fraud risk assessments. Also, HHS does not have standard procedures for conducting TANF fraud risk assessments.

· Involve relevant state or local stakeholders in the TANF fraud risk assessment process. HHS did not engage directly with state and local TANF agencies, or their respective Offices of Inspectors General or auditors, to identify TANF fraud risks while conducting the program’s fraud risk assessment. According to HHS officials, their ability to require these stakeholders to provide information on TANF fraud risks is limited, citing the previously discussed prohibitions in the Social Security Act.[29] However, as we reported, HHS is not prohibited from requesting input from stakeholders as it conducts its fraud risk assessment.

· Assess or determine the likelihood, impact, and tolerance of identified fraud risks and does not assess additional risks. HHS’s Fraud Risk Assessment Portal—used to conduct the assessments—is not designed to assess the likelihood or impact or determine tolerance of fraud risks identified. By design, the portal’s functionality currently limits programs to fully assessing risks that are part of a standard list of 38 fraud risks identified by HHS. As a result of this design, HHS programs, such as TANF, are precluded from fully assessing any additional fraud risks inherently affecting the program’s objectives that it identified or that were communicated by others. For example, we identified three additional fraud risks that HHS did not assess for TANF. These fraud risks are (1) risk of fraudulent electronic benefit transfer (EBT) card misuse by beneficiaries, (2) risk of EBT card fraud by state employees, and (3) risk associated with opaque accounting practices by subrecipients.

Having a process for assessing fraud risks that is fully consistent with the Fraud Risk Framework’s leading practices can help HHS ensure that its managers are aware of evolving fraud risks and are efficiently and effectively managing them.

In our January 2025 report, we made seven recommendations to HHS to strengthen its fraud risk management efforts, including three related to developing clear guidance and standard procedures for regular fraud risk assessments, one on communicating with state and local stakeholders, and three on improving the Fraud Risk Assessment Portal design.

HHS agreed with five recommendations but did not fully concur with two. Specifically, HHS agreed with and stated that it planned to implement the five recommendations pertaining to developing clear guidance and standard procedures for regular fraud risk assessments, communicating with state and local stakeholders, and updating the Fraud Risk Assessment Portal to allow for the assessment of any additional fraud risks facing TANF.

However, HHS did not fully concur with the remaining two recommendations for improving its Fraud Risk Assessment Portal design and guidance by enabling and requiring users to use the portal to assess the likelihood, impact, and tolerance of each fraud risk identified. In January 2025, HHS told us that these activities would be conducted outside of the portal. However, as we reported, this approach is inconsistent with the purpose of the portal. According to HHS’s guidance, the portal was built to allow users to create, maintain, and complete fraud risk assessments. HHS officials also told us that the purpose of the portal as a tool was to aggregate information from various sources to provide a holistic approach to addressing fraud risks. Given the portal’s existence and purpose, we continue to believe that the portal and its guidance should be updated so that fraud risk assessments are conducted and fully documented in the portal. Doing so can help HHS ensure that it maintains documentation in a centralized location for managers to use to prioritize fraud risks when faced with limited resources and time.

In closing, TANF statutory flexibilities allow states to fund a broad set of programs to address poverty, reduce child welfare involvement, and meet the specific needs of their diverse communities. Over time, TANF has evolved beyond a traditional cash assistance program. However, several issues limit the extent to which HHS can ensure effective oversight of TANF. These issues include insufficient reporting of states’ expenditures, states’ noncompliance with single audit requirements, the potential for improper payments, and not having a fraud risk assessment process fully consistent with leading practices. Fully addressing our recommendations would help strengthen HHS’s oversight of TANF, potentially including that of improper payments and fraud risks, and guide future decision-making on TANF. We will continue to monitor the agency’s efforts to address our recommendations.

Chairman LaHood, Ranking Member Davis, and Members of the Subcommittee, this concludes our statement. We would be pleased to respond to any questions that you may have at this time.

GAO Contacts and Staff Acknowledgments

If you or your staff have any questions about this statement, please contact Jeff Arkin at arkinj@gao.gov for questions about trends in TANF expenditures, transfers, and unspent funds and states’ reporting of TANF expenditures; Seto J. Bagdoyan at bagdoyans@gao.gov for questions about TANF fraud risk management; James R. Dalkin at dalkinj@gao.gov for questions about TANF single audit issues; or Kathryn A. Larin at larink@gao.gov for questions about TANF child welfare expenditures and states’ use of data on services funded by TANF. Contact points for our Office of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this statement.

In addition to the contacts named above, GAO staff who made key contributions to this testimony statement are Kristen Jones (Assistant Director), Jay Palmer (Analyst in Charge), Melanie Darnell, Andrea Dawson, Gabrielle Fagan, Lisa Fisher, Teressa Gardner, Lauren Gilbertson, Gina Hoover, Flavio Martinez, Jon Muchin, Keith O’Brien, Jessica Orr, Catherine Paxton, Michelle Philpott, Will Stupski, Curtia Taylor, and Mercedes Wilson-Barthes.

Appendix I: Recent GAO Recommendations for Executive Action and Matters Related to Temporary Assistance for Needy Families

We made 13 recommendations to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) in our reports related to Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) that were issued between December 2024 and April 2025. See table 2 for these recommendations, which relate to state expenditure reporting, fraud risk management, state information sharing, and single audits.

We also made one matter for congressional consideration in December 2024 related to HHS’s authority to collect certain information from states. In April 2022, we made one matter for congressional consideration on requiring states to report the data necessary to estimate and report on TANF improper payments. These matters for congressional consideration are shown in table 3. The recommendations and matters are open as of April 2025.

Table 2: Recent GAO Recommendations to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Related to Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), as of April 2025

|

Recommendations for Executive Action |

Topic |

Report |

Status |

|

The Secretary of HHS should ensure Administration for Children and Families (ACF) designs control activities to help ensure states are submitting complete narrative data in their expenditure reporting. |

State expenditure reporting |

HHS agreed with this recommendation. HHS said that it would continue to improve on its monitoring and training efforts to ensure timely submission of required reporting. |

|

|

The Secretary of HHS should ensure ACF conducts a review of all TANF reporting requirements and forms and make appropriate changes within its statutory authority to enhance reporting for oversight of TANF funds. |

State expenditure reporting |

HHS agreed with this recommendation. HHS said it would review reporting forms to improve the quality and comprehensiveness of TANF data within its statutory authority. |

|

|

The Secretary of HHS should finalize its key guidance documents on fraud risk management—the Fraud Risk Management Implementation Plan and the Fraud Risk Assessment Portal Methodology—and clearly establish a process for conducting fraud risk assessments for HHS programs, including TANF, at regular intervals and when there are changes to the program or its operating environment. |

Fraud risk management |

HHS agreed with this recommendation. HHS said it planned to finalize its fraud risk management guidance and described its process for disseminating and providing training on the updated guidance, among other steps. |

|

|

The Secretary of HHS should develop and document standard operating procedures for conducting regular fraud risk assessments tailored to TANF. This should include the roles and responsibilities of HHS entities involved in the process. |

Fraud risk management |

HHS agreed with this recommendation. HHS said it had developed standard operating procedures applicable to multiple programs. HHS also said it would develop program-specific procedures if needed. |

|

|

The Secretary of HHS should develop a process for direct and regular communication with state and local agencies, and their respective Office of Inspector General or auditors, about TANF fraud risks that includes an approach for soliciting information from these entities and document this process in its standard operating procedures for conducting fraud risk assessments tailored to TANF. |

Fraud risk management |

HHS agreed with this recommendation. HHS said it could continue to find ways to integrate discussions about TANF fraud risks into its regular communication with state and local agencies and their respective Office of Inspector General or auditors. |

|

|

The Secretary of HHS should update the design of HHS’s Fraud Risk Assessment Portal to have the functionality to allow users to assess the likelihood and impact of each fraud risk identified in a program, such as TANF; determine the related fraud risk tolerance; and include those results in the portal as part of their fraud risk assessments. |

Fraud risk management |

HHS disagreed with this recommendation. HHS said that its nonconcurrence related to adding this specific functionality to the portal. HHS said that it planned to require program offices to assess the likelihood, impact, and tolerance for each fraud risk. However, such an assessment would occur outside of the portal. We maintain that this recommendation is warranted to ensure efficient and effective fraud risk management for TANF. |

|

|

As part of finalizing HHS’s key guidance documents on fraud risk management, the Secretary of HHS should require users to assess the likelihood and impact of each fraud risk identified in a program, such as TANF; determine the related fraud risk tolerance; and include those results in the Fraud Risk Assessment Portal as part of their fraud risk assessments. |

Fraud risk management |

HHS partially concurred with this recommendation. HHS agreed with the recommended approach to assess each fraud risk individually. However, HHS stated that it advises programs to assess the likelihood and impact of each fraud risk outside of the portal. HHS noted that it would finalize its guidance to reflect this approach. We maintain that this recommendation is warranted to ensure efficient and effective fraud risk management for TANF. |

|

|

The Secretary of HHS should update the design of HHS’s Fraud Risk Assessment Portal to have the functionality to allow for the regular assessment of any additional fraud risks facing TANF, including those identified by GAO. |

Fraud risk management |

HHS agreed with this recommendation. HHS said that it updated instructions related to documenting fraud risks that it had not yet identified. HHS said it planned to update instructions to document any new and emerging fraud risks. |

|

|

As part of finalizing HHS’s key guidance documents on fraud risk management, the Secretary of HHS should require users to regularly assess any additional fraud risks facing TANF. |

Fraud risk management |

HHS agreed with this recommendation. HHS said it planned to conduct fraud risk assessments at least once every 3 years, among other steps. |

|

|

The Secretary of HHS should ensure the Assistant Secretary for Children and Families facilitate information sharing among state TANF agencies on promising practices for using data on those served with TANF non-assistance funds. For example, HHS could encourage states to share their experiences, including promising practices and challenges, with each other through conferences or workshops. |

State information sharing |

HHS agreed with this recommendation. HHS said it would integrate conversations about these data in its regular peer-to-peer learning opportunities among state TANF agencies, among other steps. |

|

|

The Secretary of HHS should ensure that ACF revises and implements its audit resolution standard operating procedures (dated November 2021) to include steps to track and measure the effectiveness of actions to help states resolve TANF single audit findings. |

Single audits |

HHS disagreed with this recommendation. ACF officials stated that the recommendation pertained to HHS’s standard operating procedures, which was not written by ACF, and that implementing such procedures was at ACF’s discretion. After receiving our draft report, ACF provided its own single audit resolution standard operating procedures. We revised our recommendation to clarify that ACF, rather than HHS, should revise and implement its audit resolution standard operating procedures. We maintain that this recommendation is warranted to ensure satisfactory resolution of TANF single audit findings. |

|

|

The Secretary of HHS should ensure that ACF develops and implements a strategy to eliminate the accumulated TANF audit backlog, to ensure that management decisions are issued within the required time frame. |

Single audits |

HHS agreed with this recommendation. HHS cited actions that it had taken or would take to address it. HHS recommended a modification to our recommendation, specifying that the backlog relates specifically to TANF findings. We have incorporated this modification into the revised recommendation. |

|

|

The Secretary of HHS should develop, document, and implement additional procedures to timely impose penalties or alternatively obtain corrective compliance plans for states that are not meeting TANF program requirements. |

Single audits |

HHS partially concurred with this recommendation. HHS stated that the penalty determination process was documented in penalty notifications letters sent to the states. As a result, we modified our recommendation to include such documentation of procedures. We maintain that this recommendation is warranted to ensure satisfactory resolution of TANF single audit findings. |

Source: GAO. | GAO‑25‑108205

Note: For the implementation status of these recommendations go to www.gao.gov and search for the report number.

Table 3: GAO Matters for Congressional Consideration Related to Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), as of April 2025

|

Matter for Congressional Consideration |

Topic |

Report |

Status |

|

Congress should consider granting HHS the authority to collect from states specific additional information needed to enhance its oversight authority, such as planned and actual TANF non-assistance expenditures, beyond what is provided for in the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996. |

State expenditure reporting |

No legislation had been enacted as of April 1, 2025, that would provide HHS the authority to collect this information from states. |

|

|

Congress should consider providing the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) the authority to require states to report the data necessary for the Secretary to estimate and report on improper payments for the TANF program in accordance with 31 U.S.C. 3352. |

Improper payments |

No legislation had been enacted as of April 1, 2025, that would provide HHS the authority to require states to report the data necessary for the Secretary to estimate and report on improper payments for TANF. |

Source: GAO. | GAO‑25‑108205

Note: For the implementation status of these matters go to www.gao.gov and search for the report number.

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]TANF was established by the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996. Pub. L. No. 104-193, 110 Stat. 2105.

[2]TANF’s purposes are: (1) to provide assistance to needy families so that children may be cared for in their own homes or the homes of relatives; (2) to end dependence of needy parents on government benefits by promoting job preparation, work, and marriage; (3) to prevent and reduce out-of-wedlock pregnancies; and (4) to encourage the formation and maintenance of two-parent families. 42 U.S.C. § 601. Spending intended to meet the first two purposes must be for those in financial need.

[3]45 C.F.R. § 260.31. HHS regulations define assistance to include cash, payments, vouchers, and other forms of benefits designed to meet a family’s ongoing basic needs (i.e., for food, clothing, shelter, utilities, household goods, personal care items, and general incidental expenses).

[4]GAO, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families: More Accountability Needed to Reflect Breadth of Block Grant Services, GAO‑13‑33 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 6, 2012); and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families: Preliminary Observations on State Budget Decisions, Single Audit Findings, and Fraud Risks, GAO‑24‑107798 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 24, 2024).

[5]GAO, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families: Enhanced Reporting Could Improve HHS Oversight of State Spending, GAO‑25‑107235 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 12, 2024); Temporary Assistance for Needy Families: Additional Actions Needed to Strengthen Fraud Risk Management, GAO‑25‑107290 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 28, 2025); Temporary Assistance for Needy Families: HHS Could Facilitate Information Sharing to Improve States’ Use of Data on Job Training and Other Services, GAO‑25‑107226 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 24, 2025); Temporary Assistance for Needy Families: HHS Needs to Strengthen Oversight of Single Audit Findings, GAO‑25‑107291 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 4, 2025); and Child Welfare: States’ Use of TANF and Other Major Federal Funding Sources, GAO‑25‑107467 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 8, 2025).

[6]The Single Audit Act is codified at 31 U.S.C. §§ 7501-7506, and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) has published implementing single audit guidance as part of its Uniform Administrative Requirements, Cost Principles, and Audit Requirements for Federal Awards (Uniform Guidance) (reprinted in 2 C.F.R. part 200, subpart F). HHS has adopted the text of the Uniform Guidance, with some HHS-specific amendments, in its related regulations incorporating the Uniform Guidance. See 45 C.F.R. part 75. Under these authorities, states that meet or exceed a certain expenditure threshold of federal awards each year must undergo a single audit (or, in limited circumstances, a program-specific audit) and then submit the single audit report and related information to the Federal Audit Clearinghouse within a designated time frame. In April 2024, OMB issued revisions to 2 C.F.R. § 200.501, raising the annual threshold of expenditures triggering a single audit or program-specific audit from $750,000 to $1 million, effective for federal awards issued beginning October 1, 2024. 89 Fed. Reg. 30,046 (Apr. 22, 2024); see also 89 Fed. Reg. 80,055 (Oct. 2, 2024).

[7]GAO‑24‑107235. Individual state spending across expenditure categories varied.

[10]The Social Security Act limits HHS’s authority to collect TANF data from states. Generally, the agency can only collect certain financial and other data in accordance with section 411 of the act; otherwise, section 417 of the act generally prohibits the agency from collecting any additional information from states.

[12]In 2016, the House Ways and Means Human Resources Subcommittee passed several bills to reform TANF that went to mark-up by the full committee in May 2016 and were reported out in June 2016. These bills included: H.R. 2990, Accelerating Individuals Into the Workforce Act; H.R. 5169, What Works to Move Welfare Recipients Into Jobs Act; H.R. 2959, TANF Accountability and Integrity Improvement Act; H.R. 2966, Reducing Poverty Through Employment Act; and H.R. 2952, Improving Employment Outcomes of TANF Recipients Act. These bills were not passed and enacted into law.

[13]GAO, COVID-19: Current and Future Federal Preparedness Requires Fixes to Improve Health Data and Address Improper Payments, GAO‑22‑105397 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 27, 2022). The Payment Integrity Information Act of 2019 defines improper payments as any payment that should not have been made or that was made in an incorrect amount (including overpayments and underpayments). 31 U.S.C. § 3351(4).

[14]Child welfare spending generally falls under TANF’s first purpose: to support needy families so that children may be cared for in their own homes or the homes of relatives. TANF spending on child welfare services is generally classified as non-assistance. TANF child welfare spending is classified as assistance when it takes the form of cash payments to caregivers.

[16]The five states we selected for this report were Arizona, Delaware, Kentucky, Texas, and Wyoming.

[18]The eligibility requirements, expected state contributions, and specific payments and services provided under TANF, Title IV-E, and Title IV-B vary by state. See GAO‑25‑107467 for more information.

[19]From fiscal years 2015 through 2022, states spent $68.6 billion in federal Title IV-E funds and state contributions, and HHS provided states with $4.4 billion in federal Title IV-B funds. Due to data limitations, the precise amount of total Title IV-B spending over this period is not known because data aggregating expenditures of both federal funds and state contributions under Title IV-B were not readily available in HHS data systems for years prior to fiscal year 2020. For fiscal years 2020 through 2022, states reported spending about $2.2 billion in federal and state Title IV-B funds.

[20]Title IV-E historically paid a portion of states’ costs for the care of children in foster care. The Family First Prevention Services Act, passed in 2018, gave states the ability to use Title IV-E funding for additional purposes. Specifically, states may now use Title IV-E funding for certain evidence-based services to help prevent the need to place children in foster care. States can receive federal reimbursement for a portion of all eligible expenses under Title IV-E. For Title IV-B, the amount of federal grant funding provided to states is determined by a formula.

[23]2 C.F.R. §§ 200.507(c)(1), 200.512(a)(1); 45 C.F.R. §§ 75.507(c)(1), 75.512(a)(1). According to OMB’s Uniform Guidance and HHS’s related regulations, the audit must be completed and submitted within the earlier of 30 calendar days after receipt of the auditor’s report(s), or 9 months after the end of the audit period (unless a different period is specified in an audit guide for a program-specific audit). If the due date falls on a weekend, or a federal holiday, then the reporting package is due the next business day.

[25]A management decision is a written evaluation by the federal awarding agency of the corrective action plan proposed by the recipient to address the findings related to programs administered by that federal agency. The management decision can indicate concurrence with the recipient’s proposed corrective actions or provide other guidance to address the finding.

[27]HHS developed the Fraud Risk Assessment Portal—a custom automated web tool that was built to allow HHS to work with its operating divisions, such as ACF for TANF—to create, maintain, and complete fraud risk assessments.

[28]GAO, A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs (Fraud Risk Framework), GAO‑15‑593SP (Washington, D.C.: July 28, 2015).As required under the Fraud Reduction and Data Analytics Act of 2015 and its successor provisions in the Payment Integrity Information Act of 2019, the leading practices in GAO’s Fraud Risk Framework are incorporated into the OMB guidelines for agency controls. 31 U.S.C. § 3357(b). Specifically, OMB’s Circular No. A-123, issued in 2016, Management’s Responsibility for Enterprise Risk Management and Internal Control (OMB M-16-17), directs executive agencies, including HHS, to adhere to the Fraud Risk Framework’s leading practices as part of their efforts to effectively design, implement, and operate an internal control system that addresses fraud risks. OMB, OMB Circular No. A-123, Management’s Responsibility for Enterprise Risk Management and Internal Control, OMB Memorandum M-16-17 (Washington, D.C.: July 2016).

[29]42 U.S.C. § 617.