DISASTER ASSISTANCE

Improving the Federal Approach

Statement of Chris Currie, Director, Homeland Security and Justice

Before the Subcommittee on Economic Development,

Public Buildings, and Emergency Management, Committee on Transportation

and Infrastructure, House of Representatives

For Release on Delivery Expected at 10:00 a.m. ET

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights

For more information, contact Chris Currie at (404) 679-1875 or CurrieC@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-108216, a testimony before the Subcommittee on Economic Development, Public Buildings, and Emergency Management, Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, House of Representatives

Improving the Federal Approach

Why GAO Did This Study

Natural disasters have become costlier and more frequent. In 2024, there were 27 disasters with at least $1 billion in damages, compared to 14 in 2018. Disasters in 2024 resulted in 568 deaths nationwide.

Further, federal disaster declarations and the expectation for federal support have increased. In addition, federal support for disaster recovery can last for years. For example, FEMA is managing over 600 open major disaster declarations—some of which occurred almost 20 years ago, according to the agency.

This statement discusses GAO’s new disaster high-risk area, and related work on reducing fragmentation of the federal approach to disaster assistance, among other things.

This statement is based on products GAO issued from May 2020 through February 2025. For this work, GAO analyzed federal law and documents related to disaster assistance and interviewed officials across relevant federal, state and local agencies. GAO also conducted site visits to recent disasters areas, among other actions.

What GAO Recommends

As of March 2025, GAO has approximately 60 open recommendations related to disaster assistance. There are also four matters for congressional consideration. These recommendations and matters are designed to address the various challenges discussed in this statement. Agencies have taken steps to address some of these recommendations. GAO will continue to monitor agency efforts to determine if they fully address the challenges GAO has identified.

What GAO Found

There is a growing emphasis on how the federal government can improve its approach to disaster recovery. In the last 10 years, appropriations for disaster assistance totaled at least $448 billion, plus an additional $110 billion in supplemental appropriations so far in fiscal year 2025. Recent disasters such as Hurricanes Helene and Milton, the wildfires in California, and this month’s destructive tornadoes across the Midwest and South demonstrated the need for government-wide action to deliver assistance efficiently and effectively and reduce its fiscal exposure (see figure). Given the rise in the number and cost of disasters and increasing challenges related to the delivery of federal disaster assistance identified in GAO’s work, Improving the Delivery of Federal Disaster Assistance was added to GAO’s High-Risk List in February 2025.

To improve the federal government’s delivery of disaster assistance, GAO has found that attention is needed to improve processes for assisting survivors, reduce fragmentation across federal disaster assistance programs, strengthen the disaster workforce and capacity, and invest in resilience. For example, GAO has recommended that Congress should consider establishing an independent commission to recommend reforms to the federal approach to disaster recovery, which is fragmented across more than 30 federal entities. GAO also reported on various options for reforming the federal approach to disaster recovery, such as better coordinating and consolidating programs across agencies and simplifying processes for survivors, among other things.

Examples of 2024 and 2025 Disaster Damage

Further, GAO recommended that the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) develop and implement a methodology that provides a more comprehensive assessment of a jurisdiction’s ability to respond to a disaster without federal assistance. Without an accurate assessment, FEMA runs the risk of recommending to the President that federal disaster assistance be awarded to jurisdictions that may not need it. FEMA has taken past steps to do this but has not fully implemented this recommendation. GAO also found that FEMA’s workforce is overwhelmed by the increasing number of disasters and other emergencies. Strengthening the disaster workforce will be a critical part of better delivering the assistance that communities and survivors need to recover.

Chairman Perry, Ranking Member Stanton, and Members of the Subcommittee:

Thank you for the opportunity to discuss our past work on the federal approach to disaster recovery.

Hurricanes, floods, wildfires, earthquakes, and other natural disasters affect hundreds of American communities each year. Due to the rising number of natural disasters, there has been a growing emphasis on how the federal government can improve its approach to disaster recovery. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration calculated that, in 2018 the U.S. experienced 14 disasters that each cost more than $1 billion in total economic damages. By 2024, the number of disasters costing at least $1 billion almost doubled to 27.[1] That same year, at least 568 people died, directly or indirectly, as a result of those disasters. Recent disasters demonstrate the need for the federal government to take action to deliver assistance efficiently and effectively and reduce its fiscal exposure.

· Hurricanes Helene and Milton occurred within 2 weeks of one another in 2024 and affected some of the same areas in the Southeast (see fig. 1). These two disasters resulted in over 200 deaths and are expected to cost over $50 billion, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

· On January 8, 2025, the President approved a major disaster declaration for historic wildfires in Los Angeles County, California. The wildfires were unprecedented in their size, scope, and the damage they caused. The Palisades and Eaton fires resulted in 29 deaths and the expected financial cost is still unknown as of March 2025.

· In mid-March 2025, destructive tornadoes and severe storms occurred across the South and Midwest over a three-day period. The storms resulted in over 40 deaths, and the number of states that will need federal assistance is still unclear as of March 2025.

Figure 1: Road Repair Following Hurricane Helene, North Carolina

My statement today is based on our most recent High-Risk update in February 2025 as well as our prior work identifying key programmatic challenges the federal government faces related to the delivery of federal disaster assistance.[2] This statement includes information on our work related to 1) improving processes for assisting survivors, 2) reducing fragmentation of the federal approach to disaster assistance, 3) strengthening Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) workforce and capacity, and 4) investing in resilience.

To conduct our prior work, we analyzed relevant statutes such as the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act,[3] regulations, agency guidance and interagency coordination documents, such as the National Disaster Recovery Framework.[4] We also interviewed officials across relevant federal agencies and state and local officials involved in disaster assistance, and conducted site visits to communities impacted by recent disasters in California, Florida, and North Carolina, among other actions. More detailed information on the scope and methodology of our prior work can be found within each of the issued reports cited throughout this statement.

We conducted the work on which this statement is based in accordance with all sections of our Quality Assurance Framework that are relevant to our objectives. The framework requires that we plan and perform the engagement to obtain sufficient and appropriate evidence to meet our stated objectives and to discuss any limitations in our work. We believe that the information and data obtained, and the analysis conducted, provide a reasonable basis for any findings and conclusions in this product.

Background

Disaster assistance includes providing support to communities and survivors for response to, recovery from, and resilience to man-made and natural disasters. For fiscal years 2015 through 2024, appropriations for disaster assistance totaled at least $448 billion.[5] In total, FEMA approved over two million households for federal disaster assistance in 2024.

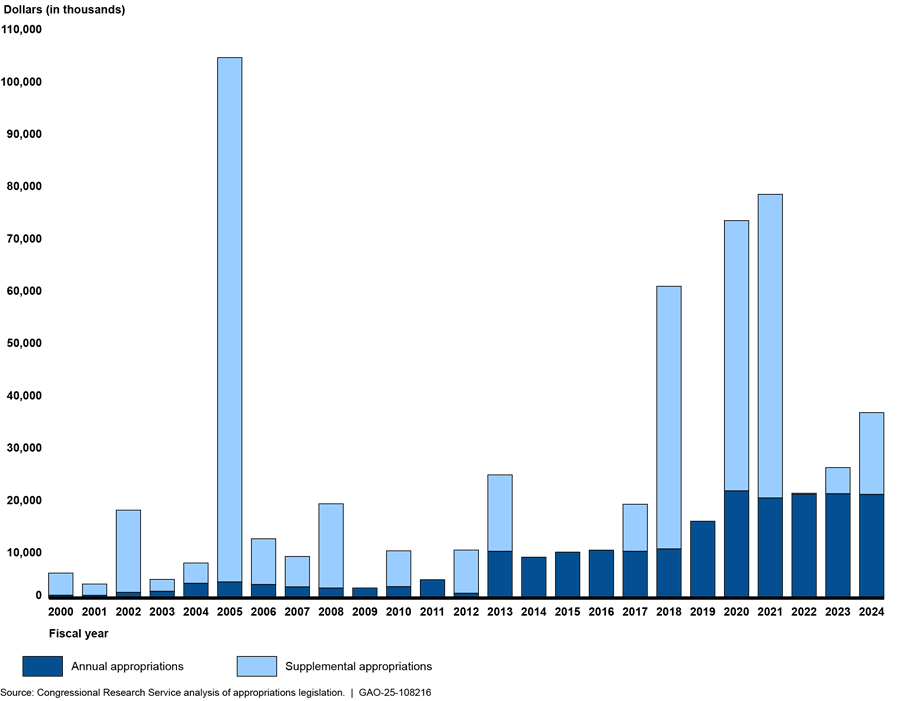

The Disaster Relief Fund, administered by FEMA, pays for several key disaster response, recovery, and mitigation programs that assist communities impacted by federally declared emergencies and major disasters. Annual appropriations to this fund have varied but generally increased from fiscal year 2000 to fiscal year 2024, as shown in figure 2. Other federal agencies have specific authorities and resources outside of the Disaster Relief Fund to support certain disaster response and recovery efforts.

Figure 2: Disaster Relief Fund Appropriations in Fiscal Year (FY) 2023 Dollars, FY 2000–2024

Note: Fiscal year 2013 numbers do not reflect the impact of sequestration. Supplemental data include contingent appropriations and all appropriations under the heading of “Disaster Relief” or “Disaster Relief Fund” including the language “for an additional amount.” Appropriations do not account for transfers or rescissions. Deflator used was drawn from the FY2024 Budget of the United States Government, “Historical Tables: Table 1.3—Summary of Receipts, Outlays, and Surpluses or Deficits (—) in Current Dollars, Constant (FY 2012) Dollars, and as Percentages of GDP: 1940—2028.”

We have also previously reported that long-term recovery can be challenging, and project costs can increase the longer a recovery lasts. For example, in February 2024, over 6 years after Hurricanes Irma and Maria made landfall in Puerto Rico in 2017, we reported that FEMA and Puerto Rico had taken actions, such as providing advance disbursements of funds to grant recipients to help jump-start permanent work construction to rebuild.[6] However, grant subrecipients that received awards from FEMA through an expedited process identified increased project costs that pose risks to the completion of work. For example, officials from Puerto Rico’s Aqueduct and Sewer Authority said that the costs for one water treatment plant project exceeded its original estimate by 42 percent.

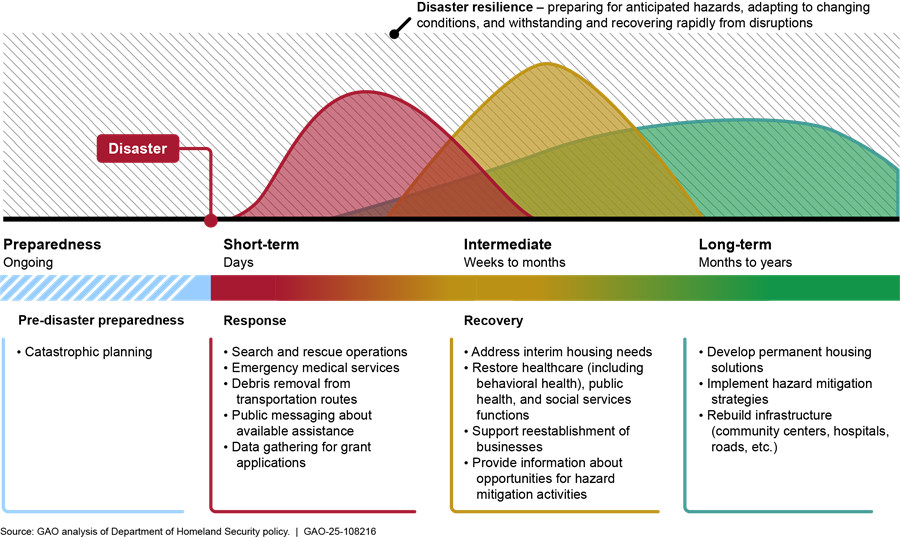

Further, the number of federal disaster declarations and the expectation for long-term federal support have increased. As shown in figure 3, federal support for disaster recovery can last for years. For example, according to FEMA, the agency is managing over 600 open major disaster declarations—some of which occurred almost 20 years ago—in various stages of response and recovery. For instance, as of February 2025, FEMA continues to make obligations for recovery projects as part of the Public Assistance program for Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005.[7]

Figure 3: Time Frames and Activities in Disaster Preparedness, Response, Recovery, and Resilience

The frequency and intensity of recent disasters have severely strained FEMA, affecting its ability to deliver assistance as effectively and efficiently as possible. We added Improving the Delivery of Federal Disaster Assistance to our High-Risk List in February 2025, given the rise in the number and cost of disasters and increasing programmatic challenges identified in our work.[8]

There are approximately 60 open recommendations related to this new high-risk area, as of March 2025. In addition, there are four open matters for congressional consideration to help address the nation’s delivery of disaster assistance, specifically related to fragmentation, property acquisitions, and housing issues.[9]

Improving Processes for Assisting Survivors

Rural Assistance

Survivors face numerous challenges receiving needed aid, including lengthy and complex application review processes. Federal agencies are taking steps to help improve disaster assistance to survivors. For example, in 2023, the Small Business Administration (SBA) implemented the Disaster Assistance for Rural Communities Act to simplify the process for a governor or tribal government chief executive to request an agency disaster declaration in counties with rural communities that have experienced significant damage.[10]

We found in February 2024 that rural areas face unique challenges in seeking SBA assistance following a disaster.[11] For example, we found that disaster survivors may not be aware of SBA’s disaster loans. We recommended that SBA should distinguish between rural and urban communities in its outreach and marketing plan and incorporate actions to mitigate the unique challenges rural communities face in accessing its Disaster Loan Program. SBA agreed with our recommendation, and we will continue to monitor its progress to address it.

Block Grants

Administered by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), the Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR) funds provide significant, flexible federal recovery funding for states and localities affected by disasters and generally support long-term recovery. However, in December 2022, we reported that HUD does not require CDBG-DR grantees to collect accurate data on critical milestones.[12]

A HUD-funded 2019 study on the timeliness of CDBG-DR housing activities found that all but one of the eight grantees in the study faced challenges in developing a grant management system. HUD could better ensure that its grantees identify problem milestones and address delays in assisting survivors by requiring grantees to collect and analyze timeliness data, as we recommended. As of February 2025, HUD said it had explored options for requiring grantees to collect milestone data and was evaluating how best to address this recommendation to ensure the needs of disaster survivors are met in a timely manner. We will continue to monitor its progress to address this issue.

Flood Insurance

Federal law created the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) to reduce the escalating costs of federal disaster assistance for flood damage, while also keeping flood insurance affordable. The NFIP transferred some of the financial burden of flood risk from property owners to the federal government. In our 2025 High-Risk List we reported that FEMA has developed a legislative proposal to improve the program’s solvency and address affordability, among other reforms.[13]

However, Congress has yet to enact comprehensive reforms to NFIP that would address the program’s challenges. We have other ongoing work about the state of the homeowner’s insurance market, including concerns about the availability and affordability of coverage, and the issue of a lack of flood insurance coverage and what can be done to address it.

Reducing Fragmentation of the Federal Approach to Disaster Assistance

The federal approach to disaster recovery is fragmented across more than 30 federal entities. These entities are involved with multiple programs and authorities and have differing requirements and timeframes. Moreover, data sharing across entities is limited. This fragmented approach can make it harder for survivors and communities to successfully navigate multiple federal programs.

Congress and federal agencies have taken steps to better manage fragmentation, such as through interagency agreements and reducing program complexity, but challenges remain. In our November 2022 report, we identified 11 options to improve the federal government’s approach to disaster recovery based on our review of relevant literature, interviews with federal, state, and local officials; and a panel of experts.[14] See table 1.

Table 1: Options to Improve the Federal

Government’s Approach to Disaster Recovery

|

1. Develop new coordinated efforts to clearly and consistently communicate about recovery programs. |

|

2. Provide coordinated technical assistance throughout disaster recovery. |

|

3. Develop models to more effectively coordinate across disaster recovery programs. |

|

4. Develop a single, online application portal for disaster recovery that feeds into one repository. |

|

5. Standardize requirements of federal disaster recovery programs. |

|

6. Simplify requirements of federal disaster recovery programs. |

|

7. Further incentivize investments in disaster resilience as part of federally-funded recovery programs. |

|

8. Identify desired recovery outcomes and develop a mechanism to track these across programs. |

|

9. Prioritize disaster recovery funding for vulnerable communities across all federal programs. |

|

10. Consolidate federal disaster recovery programs. |

|

11. Adjust the role of the federal government in disaster recovery. |

Source: GAO analysis of relevant literature; interviews with federal, state, and local officials; and a panel of experts. | GAO‑25‑108216

Certain options identified could be acted on within one or more agencies’ existing authorities, while others may require congressional action to implement.[15] In our report, we detailed the key strengths and limitations that the panel of experts identified about each of these options. For example, one option is to develop a single application for disaster recovery assistance that feeds into one repository. This portal could help applicants, including state and local governments and individual disaster survivors, identify which federal programs fit their specific recovery needs based on their eligibility.

· For strengths, experts said implementing this option could improve the applicant experience by streamlining the application process for disaster survivors and state and local applicants. This option could also help address state and local government capacity limitations by reducing the amount of work needed to complete multiple applications for different disaster recovery programs.

· In terms of limitations, experts discussed the costs associated with the development and management of the system, cross-agency privacy and data sharing concerns, and the fact that this option would not necessarily reduce the complexity of the federal disaster recovery programs.

Another identified option is to consolidate disaster recovery programs across federal agencies. This option could be implemented by, for example, providing a single federal disaster recovery block grant that identifies funding options by sector. It could also be implemented by reorganizing existing federal disaster recovery programs into a single agency focused on disaster resilience and recovery efforts.

· For strengths, experts said that consolidating federal disaster recovery programs could reduce the administrative burden on disaster survivors and state and local governments. They also said that implementing this option could reduce the number of federal funding streams for disaster recovery, which could reduce the complexity of carrying out disaster recovery projects.

· In terms of limitations, experts said that implementing this option by reorganizing government agencies would be difficult and may create additional risks. Specifically, experts noted that consolidating programs or creating a new agency would not necessarily reduce the complexity of implementing programs.

In our November 2022 report, we recommended that Congress should consider establishing an independent commission to recommend reforms to the federal approach to disaster recovery.[16] Such a commission should follow our leading practices for interagency collaboration.[17] In January 2025, a bill was introduced in the U.S. Senate that would establish a Commission on Federal Natural Disaster Resilience and Recovery to examine and recommend reforms to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the federal government’s approach to natural disaster resilience and recovery, and for other purposes.[18] We will continue to monitor the progress of this bill.

In addition, on January 24, 2025, the President established the Federal Emergency Management Agency Review Council (FEMA Review Council).[19] According to DHS, the goal of the FEMA Review Council is to advise the President on the existing ability of FEMA to capably and impartially address disasters occurring within the United States. The council shall also advise the President on all recommended changes related to FEMA to best serve the national interest.

As administrator of several disaster recovery programs, FEMA should also take steps to better manage fragmentation across its own programs, as we recommended in 2022. Such actions could make the programs simpler, more accessible and user-friendly, and improve the effectiveness of federal disaster recovery efforts.

Reforming the federal government’s approach to disaster recovery and reducing fragmentation could improve service delivery to disaster survivors and communities and improve the effectiveness of recovery efforts. In response to our November 2022 recommendations, as of February 2024, FEMA had taken steps to streamline the applications for two of its recovery programs. However, FEMA will need to demonstrate that it has thoroughly considered available options to (1) better manage fragmentation across its own programs, (2) identify which changes FEMA intends to implement to its recovery programs, and (3) take any necessary steps to fully implement the recommendation to better manage fragmentation across disaster recovery programs.[20]

Further, we have found that communities continue to face challenges obtaining support to address wildfires. FEMA and multiple other federal entities have responsibilities for federal wildfire mitigation, response, and recovery efforts, to include the award and management of contracts awarded before and during wildfire seasons. Additionally, state, local, and tribal governments can enter into mutual aid agreements with federal agencies to enable coordinated wildfire responses.

In response to the challenges that wildfires pose for the nation, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act required the establishment of the Wildland Fire Mitigation and Management Commission in 2021.[21] In September 2023, the commission issued a set of policy priorities and recommendations calling for greater coordination, interoperability, collaboration, and simplification within the wildfire system. In addition, we have found that as the incidence and severity of massive wildfires increases, FEMA and other agencies could find additional opportunities to ensure their programs are effective.[22] For example, we recommended in December 2024 that FEMA assess ways to provide immediate post-wildfire mitigation assistance and establish a process to collect, assess, and incorporate ongoing feedback from Fire Management Assistance Grants recipients.[23] Taking these steps would help foster more resilient communities and reduce the future demand on federal resources. We are monitoring efforts to address this recommendation. See figure 4 for example of wildfire damage.

Figure 4: Fire Damage Following the Palisades Fire Los Angeles, California

Strengthening FEMA’s Disaster Workforce and Capacity

FEMA has long-standing workforce management issues that make supporting response and recovery efforts difficult. In recent years, the increasing frequency and costs of disasters, the COVID-19 pandemic, and other responsibilities have placed additional pressures on FEMA. FEMA’s management of its workforce challenges and staffing levels has limited its capacity to provide effective disaster assistance.

In May 2020, we reported that FEMA has faced challenges with deploying staff with the right qualifications and skills to meet disaster needs.[24] We recommended that FEMA develop a plan to address challenges in providing quality information to field leaders about staff qualifications. In June 2022, FEMA provided a plan that included both completed and ongoing actions to address our recommendation. FEMA officials told us that the actions in the plan enhance reliability of FEMA workforce qualifications and increases field leadership accessibility of workforce information. Such actions should better enable the agency to use its disaster workforce flexibility as effectively as possible to meet mission needs in the field.

In May 2023, we reported that FEMA uses different processes under various statutory authorities to hire full-time employees and temporary reservists.[25] We found that FEMA had an overall staffing gap of approximately 35 percent across different positions at the beginning of fiscal year 2022. While the gaps varied across different positions, Public Assistance, Hazard Mitigation, and Logistics generally had lower percentages of staffing targets met—between 44 and 60 percent at the beginning of fiscal year 2022. These positions serve important functions, including administering assistance to state and local governments, creating safer communities by managing risk reduction activities, and coordinating all aspects of resource planning and movement during a disaster.

In October 2024, FEMA had only 9 percent of its disaster-response workforce available for Hurricane Milton response as staff were deployed to other disasters such as Hurricane Helene in the southeast and flooding in Vermont.[26] In addition, FEMA had only 20 percent of its disaster-response workforce available for Los Angeles fire response in January 2025.[27] We have made numerous recommendations to help FEMA better manage catastrophic or concurrent disasters.

For example, we recommended that FEMA should develop and implement a methodology that provides a more comprehensive assessment of a jurisdiction’s response and recovery capabilities including its fiscal capacity.[28] Without an accurate assessment, FEMA runs the risk of recommending to the President that federal disaster assistance be awarded to jurisdictions that may not need it. FEMA has taken steps to update the factors considered when evaluating a request for a major disaster declaration for Public Assistance, specifically the estimated cost of assistance, through the federal rulemaking process three times—in 2016, 2017, and 2020. However, as of January 2025, the agency has not issued a final rule updating the estimated cost of assistance.

The COVID-19 pandemic marked the first time the Disaster Relief Fund has been used to respond to a nationwide public health emergency. FEMA used its typical process to estimate its obligations for COVID-19. However, in July 2024 we reported that FEMA did not meet its accuracy goal for actual obligations for COVID-19 in any fiscal year from 2021 through 2023.[29] By identifying and documenting lessons learned for estimating obligations based on its experience with COVID-19, as we recommended, FEMA can better position itself to adapt to similar estimation challenges in the future. FEMA did not concur with our recommendation; however, we maintain that it is warranted. In January 2025, FEMA told us it believes the analyses it has already conducted, including an analysis of COVID-19 expenditure drawdowns, are sufficient to meet the intent of the recommendation. We have requested documentation of this analysis and of any associated lessons learned related to cost estimation. We will continue to monitor FEMA’s efforts and provide further information when we confirm any actions taken to address the recommendation.

Investing in Resilience

Disaster resilience can reduce the need for more costly future recovery assistance. In our Disaster Resilience Framework, we reported that the reactive and fragmented federal approach to disaster risk reduction limits the federal government’s ability to facilitate significant reduction in the nation’s overall disaster risk.[30]

FEMA’s hazard mitigation assistance programs provide assistance for eligible long-term solutions that reduce the impact of future disasters, thereby increasing disaster resilience. However, we have reported that FEMA can improve its hazard mitigation assistance grant programs.

For example, the Safeguarding Tomorrow through Ongoing Risk Mitigation Act of 2021 authorized FEMA to award capitalization grants—seed funding—to help eligible states, territories, Tribes, and the District of Columbia establish revolving loan funds for mitigation assistance.[31] In response, FEMA established the Safeguarding Tomorrow Revolving Loan Fund grant program in 2022. In February 2025, we found that while FEMA has identified some tools to collect information on the Revolving Loan Fund program, FEMA does not have a process for systematically collecting and evaluating the information to assess program effectiveness across all phases of the program.[32] We recommended that FEMA document and implement a process to regularly assess program effectiveness using evidence-based decision-making practices to help instill confidence in program participants and better ensure the long-term sustainability and success of the program. FEMA concurred with our recommendation.

FEMA’s Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities program provides pre-disaster mitigation grants to help eligible state, territorial, federally recognized tribal and local governments invest in a variety of natural hazard mitigation activities. These activities focus on infrastructure projects and building capability and capacity among local communities. During the 5-year period from fiscal years 2020 through 2024, FEMA made about $5.5 billion available for these grants. As of January 2025, FEMA had announced awards of about $1 billion.[33] We are currently reviewing this program.

In addition, individuals who lack sufficient insurance coverage often face greater challenges in recovery. If disaster survivors are uninsured or underinsured, they may have to rely more on federal disaster assistance. Until recent regulatory changes, FEMA did not award any housing assistance to individuals who received at least the maximum FEMA award for housing repairs from their insurance company, even if there was a gap between their insurance coverage and their losses. For disasters with Individual Assistance declared on or after March 22, 2024, FEMA will now award housing assistance to those who receive insurance payouts that exceed the FEMA maximum award for their losses, up to the statutory maximums, if they have eligible unmet needs or uncovered losses.[34] FEMA officials said they expect the amounts of Individual Assistance awards to increase due to this change.

In conclusion, by identifying and taking steps to better manage disaster assistance and the negative effects of the fragmented approach to disaster assistance, federal agencies could improve service delivery to disaster survivors and communities, improve the effectiveness of disaster recovery, and potentially reduce the federal government’s fiscal exposure. Our recommendations to the various agencies involved in disaster assistance can help Congress identify key areas to address the nation’s delivery of disaster assistance and reduce the government’s fiscal exposure. We will continue to monitor agency progress and congressional actions.

Chairman Perry, Ranking Member Stanton, and Members of the Subcommittee, this completes my prepared statement. I would be pleased to respond to any questions that you may have at this time.

GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments

If you or your staff have any questions about this testimony, please contact Chris Currie, Director, Homeland Security and Justice at 404-679-1875 or curriec@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this statement. GAO staff who made key contributions to this testimony are Joel Aldape (Assistant Director), Aditi Archer (Assistant Director), Hadley Nobles (Analyst-in-Charge), Ben Crossley, Michele Fejfar, Tracey King, and Kevin Reeves. Other staff who made key contributions to the reports cited in the testimony are identified in source products.

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on Facebook, Flickr, X, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our RSS Feeds or Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7700

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, ClowersA@gao.gov, (202) 512-4400, U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7125, Washington, DC 20548

Public Affairs

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, KaczmarekS@gao.gov, (202) 512-4800, U.S.

Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7149

Washington, DC 20548

Strategic Planning and External Liaison

Stephen J. Sanford, Managing

Director, spel@gao.gov, (202) 512-4707

U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7814, Washington,

DC 20548

[1]National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Centers for Environmental Information, “U.S. Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters” (2025). These data are not direct costs to the federal government and are produced using a detailed methodology reflecting overall U.S. economic damages, including insured and uninsured losses to residential, commercial, and government/municipal buildings.

[2]GAO, High-Risk Series: Heightened Attention Could Save Billions More and Improve Government Efficiency and Effectiveness, GAO‑25‑107743 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 25, 2025).

[3]42 U.S.C. § 5121 et seq.

[4]Department of Homeland Security, National Disaster Recovery Framework, 3rd ed. (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 2024).

[5]This total includes $312 billion in selected supplemental appropriations to federal agencies for disaster assistance and approximately $136 billion in annual appropriations to the Disaster Relief Fund for fiscal years 2015 through 2024. It does not include other annual appropriations to federal agencies for disaster assistance. Of the supplemental appropriations, $97 billion was included in supplemental appropriations acts that were enacted primarily in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, in December 2024, the Disaster Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2025, appropriated $110 billion in supplemental appropriations for disaster assistance, not included in the $448 billion. Pub. L. No. 118-158, div. B, 138 Stat. 1722 (2024).

[6]GAO, Puerto Rico Disasters: Progress Made, but the Recovery Continues to Face Challenges, GAO‑24‑105557 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 13, 2024).

[7]FEMA’s Public Assistance program provides assistance for debris removal efforts; life-saving emergency protective measures; and the repair or replacement of disaster-damaged publicly owned or certain private non-profit facilities, roads and bridges, and electrical utilities, among other activities.

[8]At the beginning of each new Congress, we issue an update to our High-Risk series, which identifies government operations with serious vulnerabilities to fraud, waste, abuse, and mismanagement, or in need of transformation. See GAO‑25‑107743.

[10]Pub. L. No. 117-249, § 2, 136 Stat. 2350 (2022) (codified at 15 U.S.C. § 636(b)(16)). See also at 13 C.F.R. § 123.3(a)(6).

[11]GAO, Small Business Administration: Targeted Outreach about Disaster Assistance Could Benefit Rural Communities, GAO‑24‑106755 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 22, 2024).

[12]GAO, Disaster Recovery: Better Information is Needed on the Progress of Block Grant Funds, GAO‑23‑105295 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 15, 2022).

[13]See GAO‑25‑107743.

[14]The panel included 20 experts with diverse backgrounds related to disaster recovery. They participated in discussions of each option and identified their strengths and limitations as they relate to improving the federal government’s approach to disaster recovery. We attribute statements from experts collected as part of the panel discussions to the “panel of experts” or “experts.” This includes statements made by individual experts. See, GAO, Disaster Recovery: Actions Needed to Improve the Federal Approach, GAO‑23‑104956 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 15, 2022).

[15]Other than where we have made prior recommendations related to certain options, we do not endorse any particular option. Rather, our November 2022 report identifies possible implementation methods and the strengths and limitations of each option. Experts who participated in our panel agreed that the federal government’s approach to disaster recovery needs to be improved. They discussed ways to make it operate more efficiently and effectively and to better incorporate incentives for improving disaster resilience and address equity concerns. See GAO‑23‑104956.

[17]GAO, Government Performance Management: Leading Practices to Enhance Interagency Collaboration and Address Crosscutting Challenges, GAO‑23‑105520 (Washington, D.C.: May 24, 2023).

[18]S. 270, 119th Cong. (2025).

[19]90 Fed. 10,082 (Feb. 21, 2025).

[21]Pub. L. No. 117-58, §§ 70201-07, 135 Stat. 429, 1250-58 (2021).

[22]See GAO, Wildfires: Additional Actions Needed to Address FEMA Assistance Challenges, GAO‑25‑106862 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 18, 2025) and GAO, Disaster Contracting: Action Needed to Improve Agencies’ Use of Contracts for Wildfire Response and Recovery, GAO‑23‑105292 (Washington, D.C.: April 13, 2023).

[24]GAO, FEMA Disaster Workforce: Actions Needed to Address Deployment and Staff Development Challenges, GAO‑20‑360 (Washington, D.C.: May 4, 2020).

[25]GAO, FEMA Disaster Workforce: Actions Needed to Improve Hiring Data and Address Staffing Gaps, GAO‑23‑105663 (Washington, D.C.: May 2, 2023).

[26]FEMA National Watch Center, National Situation Report (Oct. 8, 2024).

[27]FEMA, National Watch Center, Daily Operations Briefing (Jan. 8, 2025).

[28]GAO, Federal Disaster Assistance: Improved Criteria Needed to Assess a Jurisdiction’s Capability to Respond and Recover on Its Own, GAO‑12‑838 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 12, 2012).

[29]FEMA has a goal for its actual obligations to fall within 10 percent of the baseline estimate by the end of the fiscal year. This is for individual disasters and for the Disaster Relief Fund overall. See, GAO, Disaster Relief Fund: Lessons Learned from COVID-19 Could Improve FEMA’s Estimates, GAO‑24‑106676 (Washington, D.C.: July 9, 2024).

[30]GAO, Disaster Resilience Framework: Principles for Analyzing Federal Efforts to Facilitate and Promote Resilience to Natural Disasters, GAO‑20‑100SP (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 23, 2019).

[31]Pub. L. No. 116-284, 134 Stat. 4869 (2021) (codified at 42 U.S.C. § 5135).

[32]GAO, Disaster Resilience: FEMA Should Improve Guidance and Assessment of Its Revolving Loan Fund Program, GAO‑25‑107331 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 24, 2025).

[33]FEMA, The Disaster Relief Fund: Monthly Report as of January 31, 2025. (Washington D.C. Feb. 12, 2025) For example, of the $500 million made available in fiscal year 2020, FEMA had announced awards for $252 million, as of January 2025.

[34]FEMA’s Individual Assistance program provides financial assistance and direct services to eligible individuals and households who have uninsured or underinsured necessary expenses and serious needs as a result of a disaster. FEMA has also made other regulatory changes to the Individual Assistance program intended to improve access to assistance for survivors. 89 Fed. Reg. 3990 (Jan. 22, 2024). See also FEMA, Biden-Harris Administration Reforms Disaster Assistance Program to Help Survivors Recover Faster, (Washington, D.C.: 2024) for more information.