COURTHOUSE CONSTRUCTION

Changes to Design Guide Standards Will Result in Larger and More Costly Future Courthouses

Statement of David Marroni, Director, Physical Infrastructure

Testimony Before the Subcommittee on Economic Development, Public Buildings, and Emergency Management, Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, House of Representatives

For Release on Delivery Expected at 10:00 am ET

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact David Marroni at marronid@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-108406, a testimony before the Subcommittee on Economic Development, Public Buildings, and Emergency Management, Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, House of Representatives

Changes to Design Standards Will Result in Larger and More Costly Future Courthouses

Why GAO Did This Study

Courthouses play an important role in ensuring the proper functioning of the federal judicial system. For fiscal years 2016 through 2024, Congress appropriated $2.1 billion for the construction of 15 federal courthouse projects. According to the judiciary, this funding addressed long-standing needs for new courthouses.

The Design Guide aims to help GSA and other stakeholders build courthouses that are both functional and cost-effective. In 2021, the judiciary made changes to the Design Guide, citing the need to provide greater security for court personnel and flexibility for local courts involved in new courthouse projects.

This testimony discusses (1) the changes made in the 2021 Design Guide, and the judiciary’s rationale for making these changes; (2) how these changes could affect the size and cost of future courthouse projects; and (3) how the judiciary collaborated with selected stakeholders in making these changes. It draws primarily from GAO’s October 2024 report on the judiciary’s Design Guide.

What GAO Recommends

GAO made three recommendations to the judiciary that remain open. These include that the judiciary document a process to ensure collaboration with stakeholders when updating the Design Guide and, in collaboration with GSA, use relevant information to reassess the need for increased circulation requirements. In May 2025, the judiciary told us it is continuing to review its collaboration efforts and work to identify an approach to reassess its circulation requirements.

What GAO Found

The judiciary issued a new U.S. Courts Design Guide (Design Guide) in 2021 that included many changes in the standards from the prior 2007 version. GAO determined that 16 of the changes could affect the size or cost of courthouse projects. (See table.) Judiciary officials cited four overarching reasons for making these changes: to incorporate existing policies, provide courts with flexibility to design spaces that meet their needs, contain costs, and meet security needs. To date, no courthouses funded through fiscal year 2024 have been designed under the 2021 Design Guide. According to judiciary officials, as of May 2025, the judiciary was planning five courthouse projects with the intention of using the 2021 Design Guide.

Selected Changes in the 2021 U.S. Courts Design Guide That Could Affect the Size or Cost of Courthouse Projects

|

Change |

Description |

|

Circulation requirements |

Increases the circulation pathways (i.e., the amount of space required for movement of the public, court staff, prisoners, and others) required for judiciary spaces—primarily those associated with courtrooms and associated spaces, grand jury suites, probation and pretrial services, and other court units. |

|

Courtroom sharing policy |

Incorporates judiciary policies adopted from 2009 through 2011 for judges to share courtrooms in new courthouses with two or more magistrate, bankruptcy, or senior district judges. |

|

Ballistic-resistant materials |

Adds a requirement for ballistic-resistant material for the deputy clerk station within the courtroom. |

|

Raised access flooring |

Removes the requirement for raised access flooring in the courtroom well—the area that includes the judge’s bench, court personnel workstations, witness box, jury box and counsel tables. |

Source: GAO analysis of judiciary data. | GAO-25-108406

GAO found that changes made in

the 2021 Design Guide will significantly increase the size and cost of future

courthouse projects. To reach this conclusion, GAO estimated the potential

impacts of these changes for seven recently completed or future courthouses

designed under the 2007 Design Guide. According to this analysis, changes in

the 2021 Design Guide would increase the size of the courthouses by 6 percent

and project costs by 12 percent on average. These hypothetical increases are

due, in part, to increases in the amount of circulation within the judiciary’s

space. Increases in the judiciary’s space result in larger courthouses overall,

which GAO estimates will lead to more costly courthouses in the future, due to

the need for additional construction materials and building components.

Further, GAO found that the judiciary did not fully collaborate with the General Services Administration (GSA) or involve the Federal Protective Service, which has courthouse security responsibilities. As a result, the judiciary missed an opportunity to address significant issues, such as those related to the size, cost, and security of courthouses. Specifically, the judiciary did not fully address GSA’s concerns that the revised circulation requirements were based on a 2012 assessment of older courthouses that GAO had previously found to be oversized. Engaging with stakeholders and reassessing the need for increased circulation requirements in the 2021 Design Guide using relevant information will help the judiciary develop functional and cost-effective courthouses and could avoid millions of dollars in future costs.

Chairman Perry, Ranking Member Stanton, and Members of the Subcommittee:

I am pleased to be here today to discuss our work on federal courthouse construction. Courthouses play an important role in ensuring the proper functioning of the federal judicial system and the administration of justice. The safety and security of federal courthouses are a key consideration in their design and construction.

The construction of new federal courthouses can cost hundreds of millions of dollars. From fiscal years 2016 through 2024, Congress appropriated $2.1 billion for the construction of 15 federal courthouse projects. According to the judiciary, this funding addressed long-standing needs for new courthouses, and for repairs and alterations to existing courthouses.

The judiciary’s U.S. Courts Design Guide (Design Guide) establishes standards for designing and constructing new federal courthouses. The Design Guide aims to help the General Services Administration (GSA) and other stakeholders—including architects, engineers, judges, and court administrators—build courthouses that are both functional and cost-effective. In 2021, the judiciary made changes to the Design Guide, citing the need to provide greater security for court personnel and flexibility for local courts involved in new courthouse projects.

Allowing for such flexibilities could affect the size and cost of courthouses at a time in which Congress and executive branch agencies are taking steps to reduce the real property footprint of the executive branch.[1] Specifically, the Utilizing Space Efficiently and Improving Technologies (USE IT) Act—enacted in January 2025—requires executive branch agencies to measure their use of buildings and submit an annual occupancy report.[2] It also establishes a building utilization rate target of at least 60 percent.[3] Further, a February 2025 Executive Order directed, among other things, that GSA submit to the Office of Management and Budget a plan for the disposition of government-owned executive branch real property that agencies deemed no longer needed.[4]

This testimony is based on our October 2024 report examining issues related to the 2021 version of the Design Guide (2021 Design Guide).[5] Specifically, my remarks will focus on (1) the changes made in the 2021 Design Guide, and the judiciary’s rationale for making these changes; (2) how these changes could affect the size and cost of future courthouse projects; and (3) how the judiciary collaborated with selected stakeholders in making changes in the 2021 Design Guide. My statement will also provide an update on actions the judiciary has taken to implement the recommendations we made in our report.

To examine these issues for our report, we reviewed documentation and interviewed GSA and judiciary officials. We also worked with these officials to estimate the difference in total courthouse size and cost that would likely result from building selected projects according to the 2021 Design Guide, compared with the prior version of the guide from 2007. In addition, we conducted site visits to five of these courthouses, selected for variation in size and cost. Detailed information on the objectives, scope, and methodology for this work can be found in the issued report.

We conducted the work on which this statement is based in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Courthouse Characteristics

Federal courthouses can have different types of courtrooms and chambers, depending on the type of judges in the facility (e.g., circuit, district, magistrate, and bankruptcy). Federal courthouses can also have other spaces, such as judiciary offices, libraries, public spaces, security screening areas, and office space for other tenants, such as the U.S. Marshals Service (USMS) and GSA’s facilities management personnel. The judiciary’s Design Guide includes requirements for the size of courtrooms, judiciary staff offices, and other spaces.

Courthouses also have various pathways (e.g., hallways, stairways, and elevators) that facilitate circulation for different groups in a manner that ensures safety and security. The length and width of some of these circulation pathways can vary based on their function and to meet building codes related to the number of occupants and visitors. As described in the Design Guide, the three primary types of circulation are: (1) public circulation for spectators, attorneys, and media representatives; (2) restricted circulation for judges, courtroom deputy clerks, court reporters, other judiciary staff, and jurors; and (3) secure circulation for law enforcement personnel, witnesses, litigants, prisoners, or other individuals who are in custody.

Role of Federal Agencies

The judiciary and GSA share responsibility for managing the design and construction of courthouse projects.

· The judiciary establishes funding priorities for the construction of new courthouses based on a long-range planning process and on the status of funding for previously approved, pending courthouse construction projects.[6] Using its AnyCourt space programming tool, the judiciary identifies for GSA the type and size of spaces like courtrooms and offices, to ensure that courthouse projects meet the needs of the courts. The AnyCourt tool also calculates the amount of circulation within judiciary spaces, such as restricted hallways for court personnel to get from their offices to the courtrooms.

· GSA is typically responsible for requesting the funding for courthouse construction, acquiring the building site, and contracting for the design and construction work for courthouse projects. GSA has used the judiciary’s Design Guide, GSA’s Facilities Standards for the Public Buildings Service (now rescinded), and design guidance from other tenants to ensure that the design and construction plans of the courthouse meet the space and other needs of federal agencies.[7] GSA uses the judiciary’s AnyCourt tool, as well as other tenant agencies’ space programs, to then determine the total courthouse size. Based on this determination, GSA develops projects’ cost estimates using its Cost Benchmark Tool. The tool is intended to enable GSA to accurately forecast courthouse project costs and develop realistic budgets based on the information specified in the judiciary’s AnyCourt tool, as well as other tenants’ space requirements.

In addition, USMS and the Federal Protective Service (FPS) have security responsibilities at federal courthouses. Generally, USMS provides security in judiciary spaces within the courthouse and for federal judges, attorneys, jurors, and other members of the federal court. FPS is responsible for providing security in nonjudiciary spaces within the courthouse and along the perimeter of the courthouse.[8]

U.S. Courts Design Guide

The judiciary’s U.S. Courts Design Guide establishes standards for GSA and project stakeholders to follow when designing and constructing new federal courthouses. The judiciary issued its first Design Guide in 1991 and made major revisions in 1993, 1995, 1997, and 2007. The judiciary also amended selected chapters of the 2007 Design Guide in 2016. In 2021, the judiciary issued its most recent revisions to the Design Guide.

Congressional resolutions and appropriations act language for courthouse projects typically stipulate that standards in the Design Guide should be followed.[9] No courthouse projects funded through fiscal year 2024 were designed under the 2021 Design Guide. According to judiciary officials, as of May 2025, the judiciary is planning five courthouse projects with the intention of using the 2021 Design Guide.[10]

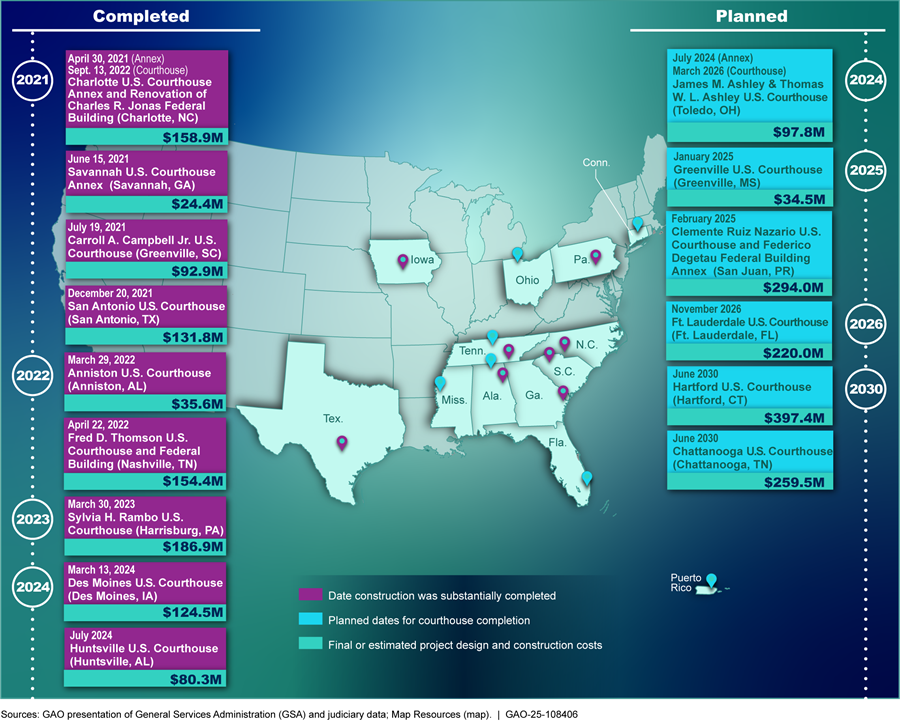

Courthouses Funded from Fiscal Years 2016–2024

Congress appropriated $2.1 billion for the construction of 15 federal courthouse projects for fiscal years 2016 through 2024. At the time of our review, GSA had completed construction of nine of these projects. The other six projects were in varying phases of design or construction. (See fig. 1.) GSA and stakeholders used the 1997 version of the Design Guide to design one of the courthouses and the 2007 version of the Design Guide, with the 2016 chapter amendments, to design 14 courthouses.

Figure 1: Status of Federal Courthouse Projects Funded from Fiscal Years 2016–2024, as of August 2024

Changes in the 2021 Design Guide Aim to Better Meet Court Needs

In our October 2024 report, we discussed that the judiciary made 16 substantive changes in the 2021 Design Guide that were likely to increase or decrease the size and cost of courthouses.[11] Judiciary officials cited four overarching reasons for making these changes: to incorporate existing policies, provide flexibility to meet the space needs at individual courthouses, contain costs, and meet security needs. For example, judiciary officials stated that changes such as increasing the amount of space for the separate circulation of the public, court staff, and prisoners were necessary to ensure safety. The 16 substantive changes in the 2021 Design Guide fall into four broad categories: (1) space sharing and future courtroom planning, (2) size standards and flexibilities, (3) design features, and (4) security. (See table 1 for examples of changes in each of these categories.)

Table 1: Selected Changes in the 2021 U.S. Courts Design Guide That Could Affect the Size or Cost of Courthouse Projects

|

Space sharing and future courtroom planning |

|

|

Change |

Description |

|

Courtroom sharing policy |

Incorporates judiciary policies adopted from 2009 through 2011 for judges to share courtrooms in new courthouses with two or more magistrate, bankruptcy, or senior district judges. For example, a courthouse with three or more magistrate judges is allocated one courtroom for every two magistrate judges, plus an additional courtroom for criminal court duty. |

|

Space planning for senior and future judges |

Incorporates the judiciary’s policy adopted in 2011 that requires new courthouse projects to include space for existing judges and to account for judges eligible for senior status within a 10-year planning period. (District judges are appointed for life but may take senior status and a reduced caseload, if desired, upon meeting certain age and tenure requirements.) Courts may not program space or include space in the proposed design for projected judgeships. |

|

Change |

Description |

|

Size standards and flexibilities |

|

|

Circulation requirements |

Changes the method for calculating circulation within judiciary units in the courthouse. Courthouses have three types of circulation: (1) public circulation for members of the public; (2) restricted circulation for judges and other judiciary staff; and (3) secure circulation to move witnesses, litigants, prisoners, or other individuals who are in custody. The 2007 Design Guide used “circulation factors” (i.e., percentage of usable space allotted for circulation), and the 2021 Design Guide uses “circulation multipliers.” Circulation multipliers are values that are applied (i.e., multiplied) to the net square footage of a judiciary unit to determine the square footage needed to move within and between spaces. |

|

Unique program spaces |

As with the 2007 Design Guide, the 2021 Design Guide allows courts to use unoccupied rooms for Alternative Dispute Resolution purposes. However, the 2021 Design Guide also allows a court to construct a separate suite of Alternative Dispute Resolution rooms within its given space requirements, with circuit judicial council approval. Further, the 2021 Design Guide allows for new courthouse design elements, including (1) fitness centers, provided they do not increase the total square footage of the project; and (2) secure rooms to store sensitive or classified information, provided the room does not increase the total square footage of the court unit where the room is located. |

|

Change |

Description |

|

Design Features |

|

|

Raised access flooring |

The 2016 amendments to the Design Guide removed the requirement in the 2007 Design Guide that courthouses must use raised access flooring in most spaces but specified that such flooring was required in the courtroom well (i.e., the area that includes the judge’s bench, court personnel workstations, witness box, jury box, and counsel tables in the courtroom). The 2021 Design Guide removed the remaining requirement for raised access flooring in the courtroom well. |

|

Interior finishes |

Allows for courts to provide input and have flexibility in the selection of finishes within an approved project budget, as specified in the 2007 Design Guide, but also provides for additional finishes. For example, the 2021 Design Guide expands the type of finish for the ceiling of the judges’ chambers suites from acoustical paneling to also include tile. |

|

Change |

Description |

|

Security |

|

|

Ballistic-resistant windows, glass, or materials |

Provides for ballistic-resistant material for the judge’s bench in the courtroom, as specified in the 2007 Design Guide, and adds this requirement for the deputy clerk station within the courtroom. Also specifies that ballistic-resistant material may be considered for a judge’s private office. |

|

Mailroom screening requirements |

Incorporates the latest standards for mail screening safety, including requiring courts to use ductless mail screening units instead of units that need dedicated air-handling equipment, as required in the 2007 Design Guide. |

Source: GAO analysis of judiciary information. | GAO‑25‑108406

Note: To identify changes, we compared the 2007 and 2021

versions of the U.S. Courts Design Guide (Design Guide). We also reviewed other

judiciary documentation and interviewed judiciary and General Services

Administration officials.

In our October 2024 report, we noted that some of the 16 substantive changes in

the 2021 Design Guide could increase the size and cost of courthouse projects.

For example, the 2021 Design Guide provides courts the option to add unique

spaces that the 2007 Design Guide did not address, such as—under certain

conditions—fitness centers and secure rooms. Fitness centers and secure rooms

must not increase the total square footage of the judiciary’s space in the

courthouse project. However, according to GSA officials, the increase in

judiciary’s circulation requirements could make judiciary spaces larger overall

and, therefore, judiciary may use the additional space to build unique spaces

now allowed under the 2021 Design Guide, such as a fitness room. Both the

judiciary and GSA projected an increase in courthouse project costs to account

for additional circulation and unique spaces.

We also discussed changes that could decrease the cost of courthouse projects with judiciary and GSA officials. For example, the 2021 Design Guide removed the requirement that courts must use raised access flooring in the courtroom well, which is the area that includes the judge’s bench, court personnel workstations, witness box, jury box, and counsel tables. According to judiciary and GSA officials, this change will reduce the cost to construct courthouses because it will simplify construction of the floors. Both the judiciary and GSA projected no change in the courthouse size from eliminating the use of raised access flooring.

Changes in the 2021 Design Guide Will Increase the Size and Cost of Future Courthouses

In our October 2024 report, we estimated that changes in the 2021 Design Guide would increase the size of future courthouses by 6 percent and project costs by 12 percent on average. These size and cost increases are due, in part, to increases in the judiciary’s circulation requirements.

Changes to Circulation Requirements Will Increase the Size of Future Projects

We modeled seven selected courthouses, which included six completed, or nearly completed, projects and one future courthouse. As shown in table 2, we estimated that changes in the 2021 Design Guide would have increased the judiciary’s space needs for the seven projects by nearly 8 percent, on average, and the overall size of these projects by about 6 percent, on average.[12]

Table 2: Estimated Increases in Judiciary and Total Courthouse Space in Selected Courthouse Projects That Would Result from Changes in the 2021 U.S. Courts Design Guide

|

Courthouse location |

Judiciary

space |

Percentage increase |

Total

courthouse space |

Percentage increase |

||

|

2007 Design Guide |

2021 Design Guide |

2007 Design Guide |

2021 Design Guide |

|||

|

Anniston, AL |

30,105 |

32,666 |

8.5% |

68,451 |

72,273 |

5.6% |

|

Charlotte, NC |

142,481 |

153,313 |

7.6 |

288,913 |

305,080 |

5.6 |

|

Greenville, SC |

110,892 |

117,277 |

5.8 |

222,575 |

232,105 |

4.3 |

|

Harrisburg, PA |

99,371 |

107,155 |

7.8 |

192,414 |

204,032 |

6.0 |

|

Huntsville, AL |

61,143 |

66,549 |

8.8 |

125,751 |

133,819 |

6.4 |

|

San Antonio, TX |

140,041 |

152,324 |

8.8 |

273,325 |

291,657 |

6.7 |

|

Future courthouse |

33,731 |

36,852 |

9.3 |

83,946 |

88,604 |

5.5 |

|

Total |

617,764 |

666,136 |

7.8% |

1,255,375 |

1,327,570 |

5.8% |

Source: GAO analysis of judiciary and General Services Administration (GSA) information. | GAO‑25‑108406

Notes: We worked with the judiciary to use its AnyCourt space programming tool to model (i.e., estimate) and compare changes in judiciary space (in usable square feet) that would likely result from building selected projects according to the 2007 and 2021 versions of the U.S. Courts Design Guide. The courthouse projects modeled included the following six completed, or nearly completed, projects: (1) U.S. Courthouse in Anniston, AL; (2) U.S. Courthouse Annex/Renovation of Jonas Federal Building and U.S. Courthouse in Charlotte, NC; (3) Campbell U.S. Courthouse in Greenville, SC; (4) Rambo U.S. Courthouse in Harrisburg, PA; (5) U.S. Courthouse in San Antonio, TX; and (6) U.S. Courthouse in Huntsville, AL. Those six projects were built according to the 2007 Design Guide. The modeled projects also included a future courthouse planned in the eastern U.S. The future courthouse is being planned according to the 2021 Design Guide. Because Congress has not yet approved and funded the future courthouse, we are not identifying the city where the project is located.

Total courthouse gross square footages are based on estimates GSA provided that include the space requirements of the judiciary and other building tenants, as well as, for example, building public spaces and maintenance support spaces.

Based on GSA and judiciary officials and our review of GSA and judiciary documentation, we found that the updated circulation requirements in the 2021 Design Guide are a significant factor in increasing the projected size of courthouses. Specifically, the 2021 Design Guide increased the circulation requirements for judiciary spaces—primarily those associated with courtrooms and associated spaces, grand jury suites, probation and pretrial services, and other court units. For example, the circulation requirements for courtrooms and associated space increased from 17 percent to 25.9 percent of usable square footage for those spaces. Based on those percentages, each district courtroom—which is 2,400 square feet under the 2007 and 2021 Design Guides—will require approximately 348 square feet of additional circulation space under the 2021 Design Guide.[13]

According to GSA officials, as the judiciary’s space increases, the overall courthouse size also increases.[14] This results in an increase in the overall building gross square footage, which comprises the total space within the courthouse, including judiciary spaces; other tenant spaces; and shared lobbies, hallways, and support spaces such as rooms for telecommunications equipment.

Changes to Circulation Requirements Will Increase the Cost of Future Projects

As a result of the increases in courthouse size identified through our modeling, we also estimated that changes in the 2021 Design Guide would increase estimated construction costs by approximately 12 percent on average for the same seven modeled projects. We worked with GSA to use its Cost Benchmark Tool to estimate cost increases that would likely result from building selected projects according to the 2007 and 2021 versions of the Design Guide.[15] According to our modeling estimates, changes in the 2021 Design Guide—mostly those made to the judiciary’s circulation requirements—increased estimated construction costs by approximately $143 million for the seven selected courthouses (see table 3).

Table 3: Increases in Estimated Construction Costs of Selected Courthouse Projects That Would Result from Changes in the 2021 U.S. Courts Design Guide

|

Location |

Estimated construction cost (millions) |

Cost increase |

||

|

2007 Design Guide |

2021 Design Guide |

Overall (millions) |

Percentage |

|

|

Anniston, AL |

$67.5 |

$75.2 |

$7.7 |

11.4% |

|

Charlotte, NC |

274.2 |

310.3 |

36.1 |

13.2 |

|

Greenville, SC |

206.5 |

220.0 |

13.5 |

6.5 |

|

Harrisburg, PA |

198.4 |

215.3 |

16.9 |

8.5 |

|

Huntsville, AL |

127.0 |

148.3 |

21.3 |

16.8 |

|

San Antonio, TX |

238.2 |

270.9 |

32.7 |

13.7 |

|

Future courthouse |

87.9 |

102.9 |

15.0 |

17.1 |

|

Total |

$1,199.6 |

$1,342.9 |

$143.3 |

11.9% |

Source: GAO summary of General Services Administration (GSA) information. | GAO‑25‑108406

Notes: We worked with GSA to use its Cost Benchmark Tool to model (i.e., estimate) and compare cost increases that would likely result from building selected projects according to the 2007 and 2021 versions of the U.S. Courts Design Guide The courthouse projects modeled included the following six completed, or nearly completed, projects: (1) U.S. Courthouse in Anniston, AL; (2) U.S. Courthouse Annex/Renovation of Jonas Federal Building and U.S. Courthouse in Charlotte, NC; (3) Campbell U.S. Courthouse in Greenville, SC; (4) Rambo U.S. Courthouse in Harrisburg, PA; (5) U.S. Courthouse in San Antonio, TX; and (6) U.S. Courthouse in Huntsville, AL. The six projects were built according to the 2007 Design Guide. The modeled projects also included a future courthouse planned in the eastern U.S. The future courthouse is being planned according to the 2021 Design Guide. Because Congress has not yet approved and funded the future courthouse, we are not identifying the city where the project is located. Figures have been rounded and do not add precisely.

Estimated costs are for construction and exclude site acquisition, design, and project management and inspection costs. The modeled construction cost estimates are not comparable to GSA’s original prospectuses to Congress (e.g., fiscal year 2016) or to actual construction costs for completed projects, as the modeled cost values, durations, and schedules are not the same.

The increases in estimated construction costs result from both increases in the judiciary’s space and the additional courthouse space and building material needed overall (other building costs).[16] Of the total estimated increase in construction costs, the portion associated with increases in the judiciary’s space varies across projects but, in aggregate, contributes to just under half ($66 million of $143 million), while the remainder is associated with the overall increases in courthouse size. If the judiciary were to revert to the circulation requirements in the 2007 Design Guide when designing future courthouses, we estimate the federal government could achieve tens of millions of dollars in cost avoidance.[17]

The Judiciary Should Collaborate with Stakeholders to Reassess the Need for Larger and More Costly Courthouses

In our October 2024 report, we found the judiciary did not

fully collaborate with GSA or FPS when updating the 2021 Design Guide and

therefore missed an opportunity to obtain additional information on significant

issues, such as those related to the security, size, and cost of courthouses.

We also reported that the judiciary solicited input on changes in the 2021

Design Guide but did not fully address GSA’s concerns.

The Judiciary Did Not Engage in Consistent Communication with GSA or Involve FPS When Updating the Design Guide

The judiciary solicited input from GSA on changes to the Design Guide and met with GSA to discuss some of its concerns with the final draft. However, the judiciary did not consistently engage in two-way communication with GSA throughout the process of updating the Design Guide. For example, while the judiciary communicated with GSA regarding comments GSA made on suggested revisions to the Design Guide in February 2020, the judiciary did not convey to GSA whether or how it had incorporated those comments. According to judiciary officials, they did not follow up with GSA on how they had addressed GSA’s feedback because they did not have a process for communicating with stakeholders to address their comments. In addition, the judiciary did not keep a record of its final disposition of the comments, because officials did not sufficiently monitor the transfer of information across the three project managers who sequentially led efforts to update the Design Guide.

Further, although the judiciary identified FPS as a key external stakeholder in 2019 during the process of updating the Design Guide, it did not solicit input from FPS. According to judiciary documentation developed after the update to the 2021 Design Guide was complete, officials did not involve FPS in the process because FPS is responsible for the external security of courthouses, which does not include the internal judiciary space to which the standards in the Design Guide apply. This documentation stated that the judiciary had incorrectly identified FPS as a stakeholder in 2019. FPS officials told us that the Design Guide largely does not affect FPS and that they did not have concerns with the 2007 Design Guide and subsequent changes.

However, the 2021 Design Guide states that the judiciary and selected other agencies, including GSA and FPS, have federal courthouse security responsibilities, and that security is essential to the basic design of courthouses.[18] Specifically, the Design Guide notes that FPS is responsible for nonjudiciary spaces within the courthouse. It also includes requirements related to FPS; for example, FPS is to install closed-circuit video cameras that provide a clear view of each exit of the courthouse.

In our October 2024 report, we recommended that the judiciary develop and document a process to better ensure effective collaboration when updating the Design Guide, including by engaging in two-way communication with, and soliciting input from, all relevant stakeholders. In May 2025, judiciary officials told us the judiciary was conducting a review of collaboration and communication processes it had previously used to identify areas of improvement. This recommendation remains open.

The Judiciary Did Not Fully Address GSA’s Concerns with Increases in Circulation Requirements

GSA raised concerns about the judiciary’s revised circulation requirements in the 2021 Design Guide. Specifically:

· GSA questioned the judiciary’s basis for increasing courthouse circulation requirements. An architectural firm the judiciary contracted to assist with revisions to the 2007 Design Guide recommended an increase in circulation requirements, in part, based on a 2012 study that examined the judiciary’s circulation space needs.[19] GSA staff raised concerns that the 2012 study relied on a review of completed courthouse projects that we previously found exceeded the sizes authorized by Congress.[20] GSA officials were unclear how the contracted architectural firm reached its conclusions, as well as how the judiciary determined the final 2021 circulation requirements in relation to the 2012 study.

· GSA raised concerns that the proposed changes to the judiciary’s circulation requirements would result in significant increases in the overall size and cost of courthouse projects. Specifically, GSA noted that the draft Design Guide’s increased circulation requirements would apply to all areas of courthouses, including public circulation and shared common spaces whose functions do not require increased circulation space. GSA officials stated that, consequently, these circulation changes would increase the overall size and cost of courthouses.

In response to GSA’s concerns, the judiciary adjusted some of the circulation requirements to less than what the contractor initially recommended. The judiciary also clarified that the revised circulation requirements applied only to judiciary spaces accessible from restricted or secured corridors. However, the judiciary did not take steps to fully address GSA’s concerns that the increased circulation requirements would significantly increase the overall size and cost of future courthouses. Further, the judiciary’s preliminary cost estimates of increasing the judiciary’s circulation space under the 2021 Design Guide did not include all potential costs for future courthouse projects. Specifically, these estimates did not account for likely increases to the overall courthouse size, operations, and maintenance costs over the life of the courthouses, and the judiciary’s rent obligations.[21] While judiciary officials acknowledged that the increased circulation requirements would lead to higher costs, they believed the circulation space and cost increases were necessary to enhance the safety of judges and the public.

Further, according to judiciary officials, architectural firms that worked on past courthouse projects using the 2007 circulation requirements reported that the circulation requirements for judiciary space were too restrictive. However, judiciary officials were unable to provide documentation of any architectural firm’s challenges related to the circulation requirements, or the number of firms and projects affected. In addition, project stakeholders and courthouse occupants we spoke with told us that courthouses built according to the 2007 Design Guide generally met their circulation needs.

In our October 2024 report, we recommended that the judiciary, in collaboration with GSA, reassess the need for increased circulation requirements in the 2021 Design Guide, using relevant information. Such an assessment should consider the space and cost modeling of recently constructed courthouses discussed in that report, the perspectives of project stakeholders and building occupants in these courthouses, the cost implications for future rent obligations paid to GSA, and operations and maintenance costs of judiciary space and overall building space in future courthouses.

In May 2025, judiciary officials told us that the judiciary and GSA had discussed our recommendation and were continuing to work to identify an approach for reassessing the circulation requirements in the 2021 Design Guide. This recommendation remains open.

Our modeling shows that the overall increase to judiciary space caused by new circulation requirements will increase the overall future courthouse size and cost. We believe that reassessing the need for increased circulation requirements in the 2021 Design Guide using relevant information—such as the perspectives of project stakeholders and building occupants in recently constructed courthouses—will help ensure that the judiciary and GSA develop functional and cost-effective courthouses. This reassessment is especially important as GSA continues to take steps to reduce the federal government’s real property footprint.

Chairman Perry, Ranking Member Stanton, and Members of the Subcommittee, this completes my prepared statement. I would be pleased to respond to any questions that you may have at this time.

GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments

If you or your staff have any questions about this testimony, please contact David Marroni, Director, Physical Infrastructure, at marronid@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this statement. GAO staff who made key contributions to this testimony are Brian Bothwell, Matt Cook (Assistant Director), Adrienne Fernandes Alcantara (Analyst in Charge), Mike Armes, John Bauckman, Jenny Chanley, Keith Cunningham, Melanie Diemel, Geoffrey Hamilton, Terrence Lam, Maria Mercado, Susan Murphy, Kathleen Padulchick, Elaina Stephenson, Colleen Taylor, Sarah Veale, Laurel Voloder, and Alicia Wilson.

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]Federal agencies have long struggled to determine the amount of space they need to fulfill their missions, which has at times led them to retain excess and underutilized space. This is one reason that managing federal real property has remained on our High Risk List since 2003. GAO, High-Risk Series: Heightened Attention Could Yield Billions More and Improve Government Efficiency and Effectiveness, GAO‑25‑107743 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 25, 2025).

[2]The USE IT Act was enacted as a part of the Thomas R. Carper Water Resources Development Act of 2024, Pub. L. No. 118-272, div. B, tit. III, § 2302, 138 Stat. 2992, 3218 (2025).

[3]The Office of Management and Budget (OMB), in consultation with GSA, is required under the USE IT Act to ensure building utilization in each public building and federally leased space is not less than 60 percent on average over each 1-year period. GSA, in consultation with OMB, is required under the USE IT Act to take steps to reduce the space of tenant agencies that fail to meet the 60 percent target. These requirements apply to Chief Financial Officers Act of 1990 (CFO Act) agencies. The CFO Act established, among other things, chief financial officers to oversee financial management activities at 23 major executive departments and agencies. Pub. L. No. 101-576, 104 Stat. 2838 (Nov. 15, 1990). The list now includes 24 entities, which are often referred to collectively as CFO Act agencies, and is codified, as amended, in section 901 of Title 31, United States Code.

[4]Exec. Order No. 14222, 90 Fed. Reg. 11095, 11096-97 (Feb. 26, 2025). For further information on recent executive branch actions to dispose of government-owned property and terminate leases, see GAO, Federal Real Property: Reducing the Government’s Holdings Could Generate Substantial Savings, GAO‑25‑108159 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 8, 2025).

[5]GAO, Federal Courthouse Construction: New Design Standards Will Result in Significant Size and Cost Increases, GAO‑25‑106724 (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 16, 2024).

[6]In prior work, we reported on the judiciary’s process for ranking courthouse needs and made recommendations to ensure that the judiciary’s methodology for ranking courthouse projects results in greater transparency and consistency. The judiciary implemented one of our three recommendations. GAO, Federal Courthouse Construction: Judiciary Should Refine Its Methods for Determining Which Projects Are Most Urgent, GAO‑22‑104034 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 5, 2022).

[7]GSA’s Facilities Standards for the Public Buildings Service (P100) established mandatory design standards and performance criteria for certain federally owned buildings in GSA’s control. GSA, P100 Facilities Standards for the Public Buildings Service (October 2021). In February 2025, GSA rescinded the P100 and issued interim guidance, stating that the informational memorandum should assist in the preparation of contract documents for architects, engineers, and general contractors until GSA develops a process to update the P100 in accordance with the Thomas R. Carper Water Resources Development Act of 2024. GSA, Rescission of PBS P100 Facilities Standards, and Issuance of PBS Interim Core Building Standards (Feb. 24, 2025). The memorandum provides a list of laws, regulations, codes, and guidelines applicable to projects in GSA facilities under design and construction, including the Design Guide.

[8]We reported on courthouse security and made recommendations that the judiciary, USMS, and FPS collect better information and improve coordination on courthouse security. The judiciary and both agencies fully implemented our recommendations. GAO, Federal Courthouses: Actions Needed to Enhance Capital Security Program and Improve Collaboration, GAO‑17‑215 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 16, 2017).

[9]Under a statutory requirement, the House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure and the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works must adopt resolutions approving the purpose before Congress can make an appropriation for the proposed project. 40 U.S.C. § 3307(a). Such committee resolutions have, for example, stipulated that, “except as provided in the prospectus,” courthouse design must not deviate from the Design Guide. If a court requests space that the Design Guide does not specify, or exceeds the limits established by the Design Guide for a given space, then this variation represents an “exception” to the Design Guide. The judiciary must review and approve exceptions before they are implemented and report them to Congress. In our October 2024 report, we found that the judiciary had not provided a clear and complete definition of, or guidance on, the types of variations that constitute an exception. We recommended the judiciary clearly define, or provide specific examples of, variations from the Design Guide that constitute exceptions subject to additional oversight. See GAO‑25‑106724. According to judiciary officials, the judiciary has taken steps to develop a report—and provide information from the report to GSA—that describes the type of variations from the Design Guide that constitute exceptions subject to additional oversight. In May 2025, we requested further information on the report. We will evaluate the extent to which its contents satisfy our recommendation when judiciary fulfills this request.

[10]Judiciary officials stated that two planned courthouses—in Anchorage, Alaska and Bowling Green, Kentucky—will include all elements from the 2021 Design Guide. An additional three planned courthouses—in Chattanooga, Tennessee; Hartford, Connecticut; and San Juan, Puerto Rico—will include cost-neutral elements (i.e., those that do not increase or decrease costs) from the 2021 Design Guide.

[11]We initially identified 28 potentially substantive changes in the 2021 Design Guide. We took additional steps to determine which changes were most substantive by requesting input from the judiciary and GSA on the changes they considered likely to increase or decrease the size and cost of courthouses. We used the judiciary and GSA’s responses and our professional judgment to identify the final 16 substantive changes that could potentially affect the size and cost of courthouses, including their views on whether the changes could increase or decrease courthouse size and cost. We did not analyze the extent to which these 16 changes would affect size or cost, except for the change in the circulation requirements, as discussed later.

[12]The judiciary’s space needs are those spaces requested by the judiciary for its use, as compared with other tenants’ space. We worked with the judiciary to use its AnyCourt space programming tool to model (i.e., estimate) and compare changes in judiciary space (in usable square feet) that would likely result from building selected projects, according to the 2007 and 2021 versions of the Design Guide. Total courthouse gross square footages are based on estimates GSA provided that include the space requirements of the judiciary and other building tenants, as well as, for example, building public spaces and maintenance support spaces. For further information, see Appendix II of GAO‑25‑106724.

[13]See table 4 of GAO‑25‑106724 for the judiciary’s circulation space requirements under the 2007 and 2021 Design Guides.

[14]GSA expresses the total size of a federal courthouse in gross square feet. GSA plans courthouse space to be 67 percent efficient (i.e., the ratio of all tenants’ usable square feet to the building’s gross square feet). Consequently, as any tenant’s usable square footage increases, so does the building gross square footage; as tenant spaces expand, public hallways and other building common spaces then expand to service the larger areas.

[15]We requested that GSA use its Cost Benchmark Tool to calculate the likely budget effects on the construction costs for the same seven selected projects of the changes in the 2021 Design Guide. GSA cost models assume that projects will take 3 years to construct, beginning in fiscal year 2026, and use fiscal year 2019 and 2022 cost values.

[16]Examples of other building costs associated with the building’s size increase include costs for telecommunication closet wiring; plumbing systems and bathroom fixtures; structural concrete and steel; and materials for “hardened” construction (e.g., heavy glazed block walls rather than lighter drywall) in the USMS’s secure circulation areas.

[17]GAO, 2025 Annual Report: Opportunities to Reduce Fragmentation, Overlap, and Duplication and Achieve an Additional One Hundred Billion Dollars or More in Future Financial Benefits, GAO‑25‑107604 (Washington, D.C.: May 13, 2025).

[18]In an April 2025 letter to congressional oversight and appropriations committees, the judiciary cited its concerns with funding in light of threats to the courts, including direct threats against individual judges. Judicial Conference of the United States, Letter to Congressional Committees (Apr. 10, 2025).

[19]Judiciary officials told us that, in making the decision to increase circulation requirements, they relied on the assessment of the 2012 study by a separate architectural firm that had extensive federal, state, and local courthouse design experience. The 2012 study was undertaken for the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts via a GSA contract. Federal courthouses assessed within the study were completed between 1995 and 2008.

[20]GAO, Federal Courthouse Construction: Better Planning, Oversight, and Courtroom Sharing Needed to Address Future Costs, GAO‑10‑417 (Washington, D.C.: June 21, 2010).

[21]We have previously reported that operations and maintenance costs typically comprise 60 to 80 percent of total life cycle costs. See GAO, Federal Buildings: More Consideration of Operations and Maintenance Costs Could Better Inform the Design Excellence Program, GAO‑18‑420 (Washington, D.C.: May 22, 2018.). GSA buildings are typically built with a 100-year assumed life cycle. Federal agencies, including the judiciary, that operate in facilities under the control and custody of GSA pay rent to GSA for the space they occupy.