SUPERFUND

Many Factors Can Affect Cleanup of Sites Across the U.S.

Statement of J.

Alfredo Gómez, Director,

Natural Resources and Environment

Before the Committee on Environment and Public Works, U.S. Senate

For Release on Delivery Expected at 10:00 a.m. ET

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact J. Alfredo Gómez at GomezJ@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-108408, a testimony before the Committee on Environment and Public Works, U.S. Senate

Many Factors Can Affect Cleanup of Sites Across the U.S.

Why GAO Did This Study

EPA is responsible for administering the Superfund program to clean up sites contaminated by hazardous substances. EPA lists some of the nation’s most seriously contaminated sites on the NPL.

Superfund sites include mining sites, landfills, and former manufacturing sites. Sites may include a variety of contaminants, such as polychlorinated biphenyls, lead, and arsenic. EPA may select different types of remedies to clean up these sites.

For nonfederal sites, EPA can, for example, carry out the cleanup itself or oversee cleanup conducted by parties responsible for the contamination, known as potentially responsible parties.

Cleanups are often expensive and lengthy. Historically, the program received money from sources such as taxes, appropriations, and recoveries from potentially responsible parties. Authority for the taxes expired at the end of 1995 and began to be reinstated in 2021 and take effect in 2022.

This statement discusses (1) trends in Superfund program appropriations, (2) numbers of NPL sites and EPA-identified reasons for changes, and (3) factors EPA officials identified as affecting the timeliness of NPL site cleanups.

GAO based this statement on its 2009, 2015, and 2016 reports about the Superfund program. Appropriations data presented in the 2015 report were updated for this statement.

What GAO Found

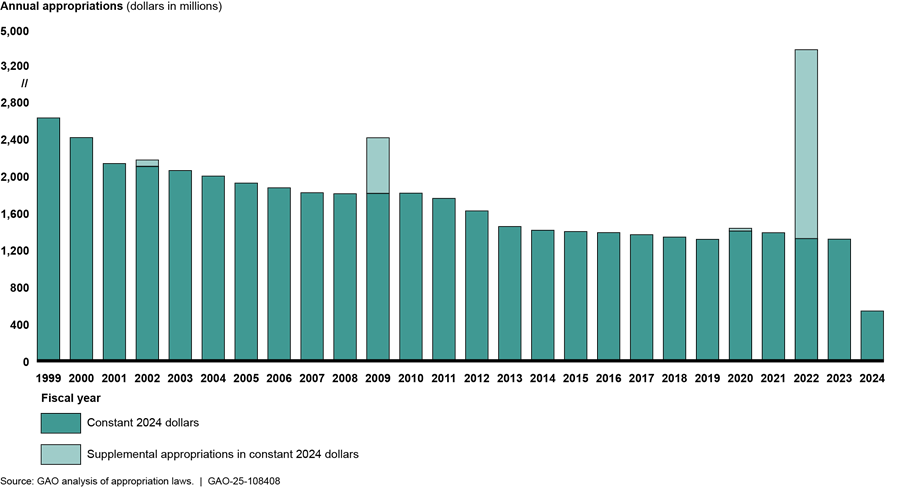

Appropriations for the Superfund program have generally declined since fiscal year 1999. Specifically, these appropriations declined from about $2.6 billion in fiscal year 1999 to about $537 million in fiscal year 2024. In fiscal year 2023, the Treasury collected $1.44 billion in Superfund taxes, which was available to the program in fiscal year 2024 as it transitioned to a combination of base and tax funding. The Superfund program also received supplemental appropriations in some years. For example, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 provided an additional $600 million in fiscal year 2009, and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act provided an additional $3.5 billion in fiscal year 2022.

Superfund Program Appropriations, Fiscal Years 1999–2024

Note: After authority for Superfund taxes expired at the end of 1995, they began to be reinstated in 2021 and take effect in 2022. In fiscal year 2023, the Treasury collected $1.44 billion in Superfund taxes, which was available to the program in fiscal year 2024 as it transitioned to a combination of base and tax funding.

As of March 5, 2025, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) National Priorities List (NPL) had 1,340 active sites across the U.S. About 90 percent of these sites are nonfederal. According to prior GAO analyses of EPA data, from fiscal year 1999 through fiscal year 2013, the numbers of new sites added to and deleted from the NPL generally declined. According to EPA officials, the decline in the number of nonfederal sites deleted from the NPL was because of the decline in annual appropriations and the fact that the sites remaining on the NPL were more complex and took more time and money to clean up.

In its prior work, GAO identified factors that EPA officials characterized as affecting the timeliness of NPL site cleanups, including the following:

· Discovery of new contaminants or a change in the extent of contamination.

· Lack of potentially responsible parties to contribute to cleanup costs.

· Technical complexity of some sites (e.g., sediment sites).

· Limited agency resources, such as decreases in funds and regional staff to perform the cleanup.

Chairman Capito, Ranking Member Whitehouse, and Members of the Committee:

Thank you for the opportunity to discuss some of GAO’s past reviews of the Superfund program. In administering the program, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) lists some of the nation’s most seriously contaminated sites, both federal and nonfederal, on its National Priorities List (NPL). Contaminants at these sites have included polychlorinated biphenyls, lead, and arsenic.[1] According to EPA documents, the precise human health effect of many chemical mixtures at NPL sites is uncertain. However, hazardous substances found at Superfund sites have been linked to human health problems such as birth defects, cancer, changes in neurobehavioral functions, and infertility. Superfund sites include mining sites, landfills, and former manufacturing sites. Cleanups of these sites are often expensive and lengthy.

This statement discusses (1) trends in Superfund program appropriations, (2) numbers of NPL sites and reasons EPA identified for changes, and (3) factors EPA identified as affecting the timeliness of NPL site cleanups. We based our statement on our 2009, 2015, and 2016 reports, as well as on updated appropriations data.[2]

A detailed discussion of our objectives, scope, and methodologies, including our assessment of data reliability, is available in each of the prior reports we cite throughout this statement. We conducted the work on which this statement is based in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

The Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980, as amended, (CERCLA) established the Superfund program, the federal government’s principal program to address sites with hazardous substances. EPA is principally responsible for administering the program.

Superfund Process

The Superfund remedial process consists of several milestones and phases, as figure 1 shows.

Figure 1: EPA’s Remedial Cleanup Process at National Priorities List Sites

The process begins with the discovery of a potentially hazardous site or notification to EPA of the possible release of hazardous substances, pollutants, or contaminants that may threaten human health or the environment. EPA, states, Tribes, or other federal agencies then conduct a site assessment to evaluate site conditions. As part of the site assessment process, EPA regional offices use a Hazard Ranking System to guide decision-making and numerically assess the site’s potential to pose a threat to human health or the environment. Sites with sufficiently high scores are eligible to be proposed for listing on the NPL. Sites that EPA proposes to list on the NPL are first published in the Federal Register.[3] After a period of public comment, EPA reviews the comments and decides whether to list the sites on the NPL by publishing the decision in the Federal Register.

After a site is listed on the NPL, EPA or parties responsible for contamination at a site (known as potentially responsible parties) generally begin the remedial cleanup process.[4] This process begins with a two-part study of the site: (1) a remedial investigation to characterize site conditions and assess the risks to human health and the environment, among other actions, and (2) a feasibility study to develop and evaluate various options to address the problems identified through the remedial investigation. These studies culminate in a record of decision that identifies EPA’s selected remedy for addressing the contamination.

A record of decision typically lays out the planned cleanup activities for each operable unit of the site.[5] EPA then plans the selected remedy during the remedial design phase, which is followed by the remedial action phase, during which one or more remedial action projects are carried out. When all physical construction at a site is complete, all immediate threats have been addressed, and all long-term threats are under control, EPA generally considers the site to be construction complete. After construction completion, most sites enter the post-construction phase, which includes actions such as operation and maintenance, during which the potentially responsible parties or the state maintains the remedy and EPA ensures that the remedy continues to protect human health and the environment. Eventually, when EPA and the state determine that no further site response is needed, EPA may delete the site from the NPL.[6]

Sources of Funding for the Superfund Program

CERCLA created the Superfund Trust Fund in the U.S. Treasury. The Trust Fund can be used to pay for the cleanup of sites on the NPL.[7]

Historically, the Superfund Trust Fund received money from four major sources: certain taxes; transfers from the General Fund of the Treasury via appropriations; fines, penalties, and recoveries from potentially responsible parties; and interest earned on the balance of the Fund. Specifically, revenue from the following taxes was historically deposited into the Trust Fund: (1) an excise tax on crude oil and imported petroleum products, (2) an excise tax on certain chemical feedstocks, (3) an excise tax on certain imported chemical derivatives, and (4) an environmental tax on corporate income. These taxes accounted for most of the deposits into the Superfund Trust Fund until the authority for the taxes expired at the end of 1995.

From 1996 until 2022, the Superfund Trust Fund was primarily financed with transfers from the General Fund of the U.S. Treasury via appropriations. In 2021, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act reinstated and modified the Superfund excise taxes on certain chemical feedstocks and certain imported chemical derivatives through December 31, 2031.[8] In 2022, the Inflation Reduction Act permanently reinstated the Superfund excise tax on crude oil and imported petroleum products beginning on January 1, 2023.[9]

EPA’s fiscal year 2024 budget request estimated that the Superfund taxes would generate $2.5 billion in revenue in fiscal year 2024. In March 2024, this estimate was updated to $2.17 billion.

Appropriations for the Superfund Program Have Generally Declined Since 1999

EPA’s Superfund program receives annual appropriations from the Superfund Trust Fund, as figure 2 shows.

Figure 2: EPA’s Superfund Program Annual Appropriations, Fiscal Years 1999–2024

Note: After authority for the Superfund taxes expired at the end of 1995, they began to be reinstated in 2021 and take effect in 2022. In fiscal year 2023, the Treasury collected $1.44 billion in Superfund taxes, which was available to the program in fiscal year 2024 as it transitioned to a combination of base and tax funding, according to the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) website. EPA’s fiscal year 2023 appropriation act permanently made all Superfund tax revenue in the Superfund Trust Fund at the end of each preceding fiscal year available without further appropriation. Pub. L. No. 117-328, div. G, 443(b), 136 Stat. 4760, 4833 (2022) (26 U.S.C. 9507 Note).

From fiscal year 1999 through fiscal year 2024, appropriations to EPA’s Superfund program generally declined, with some years of increases. In fiscal year 1999, appropriations to the program were approximately $2.6 billion; in fiscal year 2024, they were approximately $537 million. In addition, in fiscal year 2023, the Treasury collected $1.44 billion in Superfund taxes, which was available to EPA’s Superfund program in fiscal year 2024 as it transitioned to a combination of base and tax funding, according to EPA’s website.[10]

The Superfund program also received supplemental appropriations in some years. For example, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (Recovery Act) provided an additional $600 million in fiscal year 2009,[11] and IIJA provided an additional $3.5 billion in fiscal year 2022.[12] EPA reported that the Superfund program had 2,859 full-time equivalent positions in fiscal year 2013 and 2,585 in fiscal year 2023, a decrease of 274 full-time equivalent positions over the 10-year time frame.[13] GAO has ongoing work reviewing EPA’s obligations and expenditures of the Trust Fund.

EPA Identified Several Reasons for Changes in Numbers of NPL Sites

As of March 5, 2025, there were 1,340 active sites across the U.S. on the NPL, according to EPA data. There were also 41 proposed sites and 459 sites that EPA determined need no further cleanup action (deleted sites). About 90 percent of active sites are nonfederal, where EPA generally carries out the cleanup or oversees cleanup conducted by potentially responsible parties. The other NPL sites—approximately 10 percent—are located at federal facilities, and the federal agencies that administer those facilities are responsible for their cleanup.[14] GAO has planned work to examine NPL site cleanup status.

When we last reviewed NPL site cleanup status in 2015, we found that the number of nonfederal sites added to and deleted from the NPL from fiscal year 1999 through fiscal year 2013 generally declined, according to our analysis of EPA data.[15]

According to EPA officials we interviewed for that report, there were several reasons for this decline in the number of new nonfederal sites added to the NPL from fiscal years 1999 through 2013. For example, some states may have been managing the cleanup of sites with their own state programs, especially if a potentially responsible party was identified to pay for the cleanup.

Additional reasons the officials identified for the decrease during this time period include: (1) funding constraints that led EPA to focus primarily on sites with actual human health threats and no other cleanup options, (2) use of the NPL as a mechanism of last resort, and (3) referral of sites assessed under the Superfund program to state cleanup programs.

While the number of new sites generally decreased, they increased from fiscal year 2008 through fiscal year 2012. According to the EPA officials, these numbers may have increased because the agency expanded its focus to consider NPL listing for sites with potential human health and environmental threats, and it shifted its policy to use the NPL when it was deemed the best approach for achieving site cleanup rather than using the NPL as a mechanism of last resort. Also, states’ funding for cleanup programs declined, and states agreed to add sites to the NPL where they encountered difficulty in getting a potentially responsible party to cooperate or where the potentially responsible party went bankrupt, according to the officials.

According to the EPA officials, the decline in the number of nonfederal sites deleted from the NPL was due to the decline in annual appropriations and the fact that the sites remaining on the NPL at this time were more complex and would take more time and money to clean up.

Many Factors Can Affect Timeliness of NPL Site Cleanup

In our prior work, we identified examples of factors that EPA officials said can affect the agency’s ability to clean up NPL sites in a timely manner.[16] These include the following:

· Adverse conditions. Weather conditions, such as excessive rain, can delay progress at some sites (GAO‑15‑812).

· Discovery of new contaminants or a change in the extent of contamination. The discovery of new contaminants or a change in the extent of contamination, such as contaminants migrating at a groundwater site, can cause delays. Adjustments may be necessary to remedy designs, which could take additional time and money (GAO‑15‑812).

· Lack of potentially responsible parties. Fewer sites may have responsible parties who can contribute to cleanup, which could affect EPA’s ability to fund and conduct site cleanups (GAO‑09‑656).

· Limited agency resources. Decreases in funds and regional staff available to perform the cleanup can cause delays. For example, EPA officials stated that shortages in EPA regional staffing levels and a decline in state environmental agency personnel can cause delays throughout the Superfund program, from site assessments to completion of remedial action projects (GAO‑15‑812).

· NPL listing process. Addressing complex comments during the NPL public comment process may require considerable EPA time and resources (GAO‑15‑812).

· Stakeholder involvement. Challenges with stakeholder involvement can take EPA time and resources to address. For example, stakeholders such as communities, local governments, and industry may have differing opinions and competing interests, and their levels of knowledge of the Superfund process may vary. (GAO‑16‑777).

· Technical complexity. Some sites are more technically complex to clean up because of site characteristics. For example, complicating factors at sediment sites include their size, location, tidal influences, multiple sources of contamination, and difficulties related to sampling and modeling (GAO‑16‑777).

In conclusion, EPA’s Superfund program has generally faced declining annual appropriations since fiscal year 1999, with influxes of supplemental appropriations in some years and increases in some years. Our previous work shows that the numbers of new sites added to and removed from the NPL have generally declined from fiscal year 1999 through fiscal year 2013. EPA officials identified several factors that can affect the timeliness of NPL site cleanup, including those I discussed in this statement. GAO has ongoing work reviewing funding and expenditures of the program and planned work to examine NPL site cleanup status.

Chairman Capito, Ranking Member Whitehouse, and Members of the Committee, this completes my prepared statement. I would be pleased to respond to any questions you may have at this time.

GAO Contacts and Staff Acknowledgments

If you or your staff have questions about this statement, please contact J. Alfredo Gómez, Director, Natural Resources and Environment at GomezJ@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this statement.

GAO staff who made key contributions to this testimony are Barbara Patterson (Assistant Director), Bruna Oliveira (Analyst in Charge), Jenny Chanley, Erik Kjeldgaard, Mae Jones, and Jeanette Soares. Additional contributors are listed in the reports on which this statement is based.

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]Polychlorinated biphenyls belong to a broad family of manmade organic chemicals known as chlorinated hydrocarbons, which are chemical compounds of chlorine, hydrogen, and carbon atoms.

[2]GAO, Superfund: Litigation Has Decreased and EPA Needs Better Information on Site Cleanup and Cost Issues to Estimate Future Program Funding Requirements, GAO‑09‑656 (Washington D.C.: Jul. 15, 2009); Superfund: Trends in Federal Funding and Cleanup of EPA’s Nonfederal National Priorities List Sites, GAO‑15‑812 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 25, 2015); and Superfund Sediment Sites: EPA Considers Risk Management Principles but Could Clarify Certain Procedures, GAO‑16‑777 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 22, 2016).

[3]As a matter of policy, EPA seeks concurrence from the government of the state in which a site is located before proposing a site for listing on the NPL.

[4]In addition to these remedial cleanup actions, EPA may conduct removal actions, which are generally short-term or emergency cleanups to mitigate immediate threats. This statement discusses the remedial process.

[5]According to EPA guidance, EPA uses operable units and remedial action projects to subdivide a Superfund site into a series of smaller components that allow for effective management and implementation of cleanup activities. An operable unit is a discrete action that comprises an incremental step in cleaning up a site and commonly refers to a geographic area, a pathway of the contamination (e.g., groundwater), or type of remedy. A site may consist of one or more operable units, each of which may be addressed by one or more remedial action projects. A remedial action project is generally where the physical work undertaken to address contamination takes place at a site.

[6]According to EPA’s website, when all site cleanup has been completed and all cleanup goals have been achieved, EPA publishes a notice of its intention to delete the site from the NPL in the Federal Register and notifies the community of its availability for comment. EPA then accepts comments from the public on the information presented in the notice and issues a Responsiveness Summary to formally respond to public comments received. If the site still qualifies for deletion after the formal comment period, EPA publishes a formal deletion notice in the Federal Register and places a final deletion report in the Information Repository for the site.

[7]Specifically, the Trust Fund can be used to pay for remedial actions at NPL sites. In addition, the Trust Fund can be used to pay for certain removal actions.

[8]Pub. L. No. 117-58, § 80201, 135 Stat. 429, 1328-1330 (2021).

[9]Pub. L. No. 117-169, § 13601, 136 Stat. 1818, 1981-1982 (2022).

[10]EPA’s fiscal year 2023 appropriation act permanently made all Superfund tax revenue in the Superfund Trust Fund at the end of each preceding fiscal year available without further appropriation. Pub. L. No. 117-328, div. G, § 443(b), 136 Stat. 4760, 4833 (2022) (26 U.S.C. § 9507 Note).

[11]Of this $600 million, EPA allocated $582 million to remedial cleanup activities and $18 million to internal EPA activities related to the management, oversight, and reporting of Recovery Act funds.

[12]Most of this $3.5 billion is dedicated to EPA-financed remedial action construction projects at nonfederal NPL sites, according to EPA documentation.

[13]EPA’s budget justification shows 2,479 full-time equivalent positions in fiscal year 2023. However, in commenting on this statement, EPA provided the updated number.

[14]EPA is responsible for oversight of cleanup at federal facilities that are on the NPL.

[16]We identified these factors in our 2009, 2015, and 2016 reports on the Superfund program. The factors are listed alphabetically and do not constitute an exhaustive list but provide illustrative examples for the purpose of this statement.