FRAUD AND IMPROPER PAYMENTS

Data Quality and a Skilled Workforce Are Essential for Unlocking the Benefits of Artificial Intelligence

Statement of Dr. Sterling Thomas, Chief Scientist

Before the Joint Economic Committee, U.S. Congress

For Release on Delivery Expected at 2:30 p.m. ET

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Sterling Thomas at ThomasS2@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-108412, a testimony before the Joint Economic Committee,

U.S. Congress

Data Quality and a Skilled Workforce Are Essential for Unlocking the Benefits of Artificial Intelligence

Why GAO Did This Study

GAO has reported that fraud and improper payments are estimated to have cost taxpayers trillions of dollars. These issues also impact the integrity of federal programs and erode public trust. Improper payments are payments that should not have been made or that were made in the wrong amount. Fraud involves obtaining something of value through willful misrepresentation.

The advancement of AI presents both opportunities and challenges for combatting fraud and improper payments in the federal government. This testimony describes 1) actions Congress and agencies can take to combat fraud and improper payments without the use of AI, 2) opportunities and challenges for using AI to combat fraud and improper payments, and 3) workforce challenges in the use of AI in the federal government.

What GAO Found

The federal government has many existing tools and resources to help agencies combat fraud and improper payments. GAO has recommended improvements in these areas. For example, Congress could make permanent the Social Security Administration’s authority to share its full death data with the Department of the Treasury’s Do Not Pay system.

Programs Reporting the Largest Percentage of Estimated Improper Payments in Fiscal Year 2024

Note: See full report for details of payment estimates.

Artificial intelligence (AI) and other innovative technologies have the potential to enhance efforts to combat fraud and improper payments. However, these tools require high-quality data. Introducing insufficient, unrelated, or bad data will make an AI model less reliable. A system that produces errors will also erode trust in the use of AI to detect fraud. GAO’s AI Accountability Framework for Federal Agencies and Other Entities includes key practices for ensuring data are high-quality, reliable, and appropriate for the intended purpose. Another potential step, which GAO recommended in 2022, is to establish a permanent analytics center of excellence focused on fraud and improper payments. Should such a center be realized, it is likely that an AI-based tool would be a key component.

An AI-ready workforce is another essential requirement if the federal government is to use this tool in the fight against fraud and improper payments. For decades, however, GAO has identified mission-critical gaps in federal workforce skills and expertise in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. More specifically, there is a severe shortage of federal staff with AI expertise. GAO has reported that improvements may be hampered by uncompetitive compensation and the lengthy federal hiring process.

Chairman Schweikert, Ranking Member Hassan, and Members of the Committee:

Thank you for the opportunity to discuss using artificial intelligence (AI) to combat fraud and improper payments.

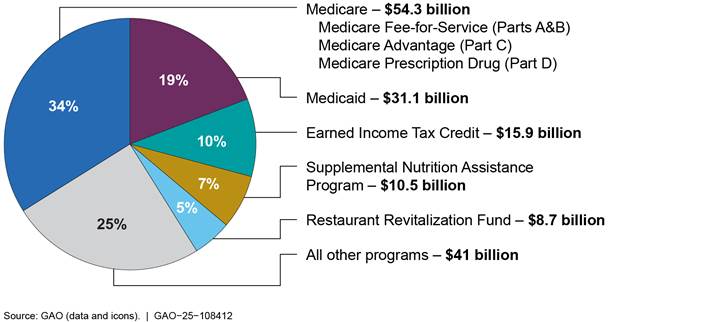

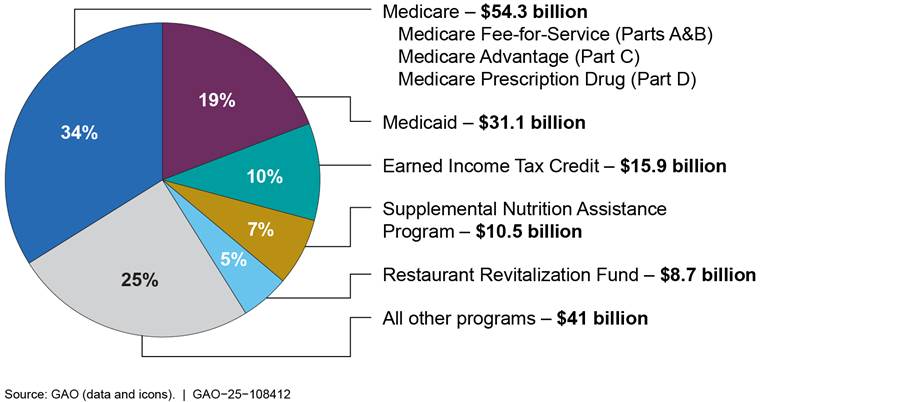

GAO has reported that improper payments and fraud are estimated to have collectively cost taxpayers trillions of dollars. In addition, these issues impact the integrity of federal programs, and erode public trust.[1] Improper payments are payments that should not have been made or that were made in the wrong amount, typically overpayments.[2] Fraud involves obtaining something of value through willful misrepresentation.[3] We estimated that the federal government loses between $233 billion and $521 billion annually from fraud, based on fiscal year 2018 to 2022 data.[4] Since fiscal year 2003, cumulative improper payment estimates by executive branch agencies have totaled about $2.8 trillion, but are almost certainly greater, in part because agencies have not reported estimates for some programs as required. For example, last year we reported that agencies failed to report fiscal year 2023 improper payment estimates for nine risk-susceptible programs.[5] Figure 1 shows that about 75 percent ($121 billion) of total government-wide estimated improper payments reported for fiscal year 2024 are concentrated in five program areas.

Figure 1: Programs Reporting the Largest Percentage of Improper Payments Estimates in Fiscal Year 2024

Note: Improper payment estimates displayed in the figure include both improper and unknown payments. Executive agency estimates of improper payments treat as improper any payments whose propriety cannot be determined due to lacking or insufficient documentation. 31 U.S.C . 3352(c)(2)(A).

The advancement of AI presents both opportunities and challenges for combatting improper payments and fraud in the federal government. Today I will discuss 1) actions Congress and agencies can take to combat fraud and improper payments without the use of AI, 2) opportunities and challenges for using AI to combat fraud and improper payments, and 3) workforce challenges in the use of AI in the federal government. To complete this work, we reviewed GAO’s body of work on improper payments, fraud, and artificial intelligence. Specifically, we assessed reports on federal financial management, fraud prevention, GAO’s High Risk List, and artificial intelligence. Appendix I shows selected GAO work on AI.

We performed the work on which this testimony is based in accordance with all applicable sections of GAO’s Quality Assurance Framework.

Congress and Agencies Could Improve Existing Systems to Combat Fraud and Improper Payments

While eliminating all fraud is not a realistic goal, the federal government has many tools and resources already in place to help agencies prevent fraud prior to funds distribution and to combat fraud and improper payments once they have occurred.[6] Agency and congressional action on our recommendations for improvements in these areas could enhance these efforts.

One key resource for preventing improper payments and fraud is the Department of the Treasury’s Do Not Pay system, which consolidates data on ineligible entities. The Social Security Administration (SSA) currently shares its full death data with Do Not Pay, but its authority to do so expires next year. We have recommended that Congress consider making it permanent.[7] In January 2025, Treasury reported recovering $31 million in payments to deceased individuals during a 5-month period on the pilot with the SSA Full Death Master file.[8]

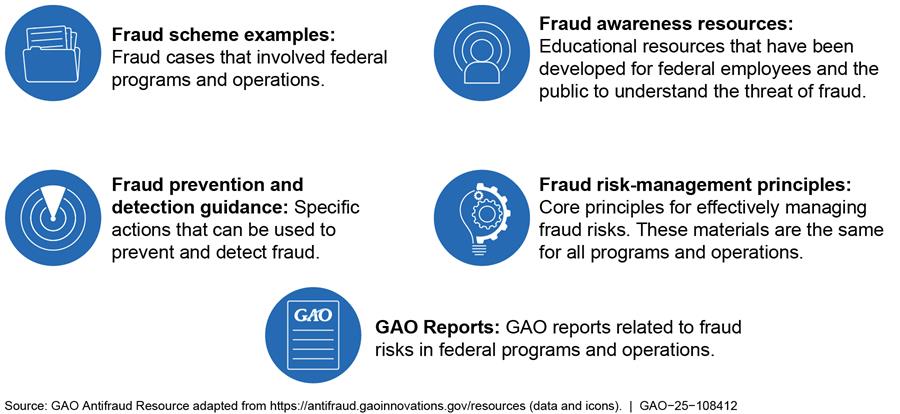

For fraud risk management, preventive activities generally offer the most cost-efficient use of resources, since they enable managers to avoid a costly and inefficient “pay-and-chase” model. Managers of federal programs maintain the primary responsibility for managing fraud risk. Since 2016, agencies have been required to adhere to leading practices in GAO’s Fraud Risk Framework to effectively design, implement, and operate an internal control system that addresses fraud risks.[9] A leading practice in the Fraud Risk Framework involves designing and implementing data analytic controls to prevent and detect fraud.[10] Our prior work has highlighted areas in which federal agencies need to take additional actions to help ensure they are effectively managing fraud risks consistent with leading practices, such as using data analytics to better manage fraud risk. Specifically, from July 2015 through August 2023, we made 47 recommendations to federal agencies in this area. These include recommendations to design and implement data-analytics activities to prevent and detect fraud, such as using data matching to verify self-reported information. Of the 47 recommendations, a little more than half have been implemented as of April 2024. To further help agencies build prevention-focused anti-fraud efforts, GAO developed its web-based Antifraud Resource, which provides interactive tools and resources for understanding and combatting fraud.[11]

For example, our Antifraud Resource provides curated resources that can help agencies identify case examples, guidance, and other tools for combatting various types of fraud in federal programs (see fig. 2). Implementing our recommendations and using our resources can enable agencies to carry out their missions and better protect taxpayer dollars from fraud.

Figure 2: Five Categories of Antifraud Resources

Opportunities and Challenges for Using AI to Combat Improper Payments and Fraud

New innovations like AI-enabled tools can perform some of the tasks required to combat fraud and improper payments in the federal government. However, these tools require sufficient high-quality data, an understanding of risks, and staff with knowledge of how to use AI. Introducing insufficient, unrelated, or bad data will make an AI model less reliable, and maintaining a “human in the loop” is vital to ensuring oversight of the data and processes. A system that produces errors will also erode trust in AI to detect fraud.

AI, in general, refers to computer systems that can solve problems and perform tasks that have traditionally required human intelligence. Machine learning is a subset of AI that underpins many of the recent improvements in the field and could be used to detect fraud and improper payments. Many federal agencies are using or planning to use machine learning, including to support detecting improper payments.

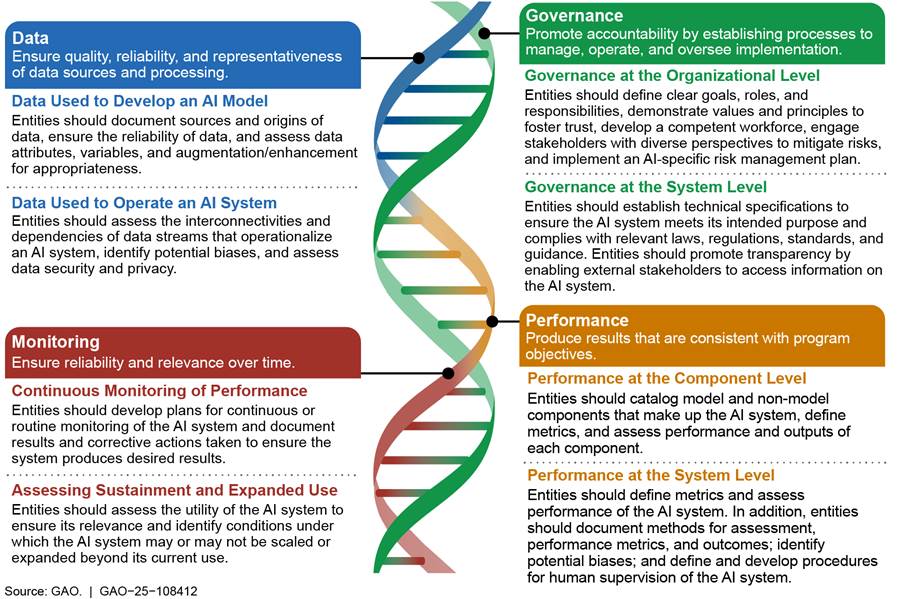

In recognition of the opportunities and risks of AI, in 2021, we published Artificial Intelligence: An Accountability Framework for Federal Agencies and Other Entities (see fig. 3).[12] We identified 31 key practices to help ensure accountability and responsible AI use by federal agencies and other entities, which could include use for combatting fraud and improper payments. These key practices include ensuring systems are documented, designed, and governed appropriately for their intended uses; ensuring data quality; and recruiting and retaining personnel with the necessary multidisciplinary skills and experiences.

Figure 3: GAO Artificial Intelligence (AI) Accountability Framework

Machine learning algorithms work by identifying statistical relationships between inputs and outputs from a training dataset. Training data can include numbers, images, or text. Training is the process of feeding training data through the algorithm until it identifies statistical relationships of interest.

Such a model might improve detection or prevention of fraud and improper payments by revealing anomalous patterns, behaviors, and relationships with a speed and scale that was not possible before.[13] But machine learning models can also pose risks. For example, they may fail to detect improper payments (false negatives) and they can erroneously identify legitimate payments as improper (false positives). False positives, in turn, can delay or deny payments to rightful recipients, such as small businesses and beneficiaries of Social Security and Medicare.

Critical to mitigating such risk is training the model on high-quality data. A common phrase among AI developers is “garbage in, garbage out,” meaning that poor data will give poor results. This axiom also applies to AI for detecting fraud and improper payments. In our AI Accountability Framework, we identified five key practices to help entities use appropriate data for developing AI models. For example, entities should document sources and origins of training data and ensure that the data are incorporated into the most appropriate AI model.

For detecting fraud and improper payments, machine learning systems could require training data in the form of payments labeled as one of three categories: accurate, improper without fraud, or fraud. Labeling historical data incorrectly could lead to false results. If these become too numerous, agencies will spend more time identifying AI’s mistakes than they will save compared with traditional detection methods. The training data could also be adulterated by “data poisoning,” a process by which someone changes the data, which changes the behavior of a system.

Technology can be used to identify targets of opportunity that allow the government agencies and Inspectors General to probe further into suspected fraud. AI tools can be a useful technology and will further evolve. But we need solid, reliable “ground truth” data and a human in the loop to ensure data reliability and appropriate application of the technology. AI does not replace the professional judgment of experienced staff in detecting potentially fraudulent activities. While AI can sift through large volumes of data, human intelligence is still an essential element for choosing appropriate actions and technology tools.

Whether government data will reliably provide this ground truth is unclear. Such data vary in quality and standards. We have recommended numerous improvements to federal agencies, such as data mining and other analytic practices to ensure data are sufficient for fraud risk analysis. In our 2023 survey on fraud risk management, federal agencies told us that access to data to look for fraud indicators was a challenge.[14]

To improve the use of data analytics in identifying fraud and improper payments, we recommended in 2022 that Congress establish a permanent analytics center of excellence, similar to the Pandemic Analytics Center of Excellence (PACE).[15] Should such a center be realized, it is likely that an AI-based tool would be a key component.

An AI-Ready Federal Workforce Is Essential for Innovation

An AI-ready workforce is another essential requirement if the federal government is to use this tool in the fight against fraud and improper payments. For decades, however, we have identified mission-critical gaps in federal workforce skills and expertise in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. More specifically, there is a severe shortage of federal staff with AI expertise.

One option Congress has considered is establishing a new digital services academy—like the military academies—to train future workers.[16] In 2021, we convened technology leaders from government, academia, and nonprofits to discuss such an academy and related issues. Among their comments:

· Current federal digital staff compensation is not competitive.

· Many digital staff may not be willing to endure the lengthy federal hiring process.

· An academy might best focus on master’s degrees because agencies need staff with advanced skills.

Chairman Schweikert, Ranking Member Hassan, and Members of the Committee, this completes my prepared statement. I would be pleased to respond to any questions that you may have at this time.

GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments

Sterling Thomas, Chief Scientist, ThomasS2@gao.gov.

GAO staff who made key contributions to this testimony are Lisa Gardner (Assistant Director), Claire McLellan (Analyst-in-Charge), Jenique Meekins, Joseph Rando, and Ben Shouse. With contributions from Seto Bagdoyan, Virginia Chanley, Alex Gromadzki, Michael Hoffman, Hannah Padilla, Rebecca Shea, Jared Smith, Andrew Stavisky, Kevin Walsh, and Candice Wright.

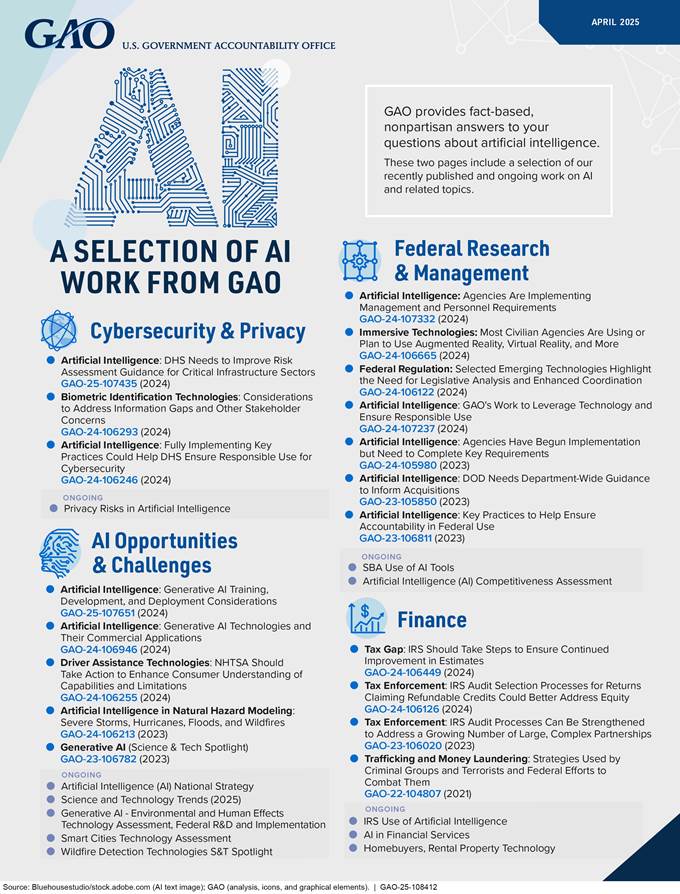

Appendix I: A Selection of Artificial Intelligence Work from GAO

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]GAO, Improper Payments: Agency Reporting of Payment Integrity Information, GAO‑25‑107552, (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 23, 2025). GAO, Improper Payments and Fraud: How They Are Related but Different, GAO‑24‑106608, (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 7, 2023).

[2]An improper payment is defined by law as any payment that should not have been made or that was made in an incorrect amount (including overpayments and underpayments) under statutory, contractual, administrative, or other legally applicable requirements. It includes any payment to an ineligible recipient, any payment for an ineligible good or service, any duplicate payment, any payment for a good or service not received (except for such payments where authorized by law), and any payment that does not account for credit for applicable discounts. 31 U.S.C. § 3351(4). Executive agency heads are required periodically to review the programs and activities they administer and make an estimation of each program or activity’s improper payments. If in conducting such a review an agency head is unable to discern whether a payment was proper because of insufficient or lack of documentation, that payment must also be included in the improper payment estimate. 31 U.S.C. § 3352(a),(c).

[3]Fraud can sometimes involve benefits that do not result in direct financial loss to the government (such as passport fraud). Improper payments, fraud, and fraud risk are related but distinct concepts. While unintentional error may cause improper payments, fraud involves obtaining something of value through willful misrepresentation. Whether an act is fraudulent is determined through the judicial or other adjudicative system. Fraud risk exists when individuals have an opportunity to engage in fraudulent activity.

[4]GAO. Fraud Risk Management: 2018-2022 Data Show Federal Government Loses an Estimated $233 Billion to $521 Billion Annually to Fraud, Based on Various Risk Environments, GAO‑24‑105833, (Washington, D.C.: Apr 16, 2024).

[5]GAO, Improper Payments: Key Concepts and Information on Programs with High Rates or Lacking Estimates, GAO‑24‑107482 (Washington, D.C.: June 27, 2024).

[6]Agency Inspectors General play an important role in investigating instances of fraud in their respective agencies. Per the Inspector General Act of 1978, as amended, the mission of agency Inspectors General includes preventing and detecting fraud, waste, and abuse. 5 U.S.C. § 402(b). However, often by the time an Office of Inspector General detects fraud or an improper payment that has already occurred, it is challenging to get the money back.

[7]In March 2022, we recommended that Congress amend the Social Security Act to accelerate and make permanent the requirement for SSA to share its full death data with the Treasury’s Do Not Pay system. GAO, Emergency Relief Funds: Significant Improvements Are Needed to Ensure Transparency and Accountability for COVID-19 and Beyond, GAO‑22‑105715 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 17, 2022).

[8]“Treasury Data Pilot Prevents and Recovers $31 Million in Payments to Deceased Individuals During a Five-Month Period,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, January 15, 2025, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy2784.

[9]GAO, A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs, GAO‑15‑593SP (Washington, D.C.: July 28, 2015)

[10]OMB’s Circular No. A-123, Management’s Responsibility for Enterprise Risk Management and Internal Control, directs executive agencies to adhere to the Fraud Risk Framework’s leading practices as part of their efforts to effectively design, implement, and operate an internal control system that addresses fraud risks.

[11]GAO Fraud Ontology Version 1.1 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 15, 2024), https://gaoinnovations.gov/antifraud_resource/howfraudworks.

[12]GAO, Artificial Intelligence: An Accountability Framework for Federal Agencies and Other Entities, GAO‑21‑519SP, (Washington, D.C.: June 30, 2021).

[13] Taka Ariga, “Artificial Intelligence Creates New Opportunities to Combat Fraud.” International Journal of Government Auditing, Summer 2020 Edition.

[14] GAO, Fraud Risk Management: Agencies Should Continue Efforts to Implement Leading Practices, GAO-24-106565 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 01, 2023).

[15]GAO‑22‑105715. And, according to a March 31, 2025, press release from PACE, investigators used the PACE data analytics platform to untangle the electronic trail that fraudsters left behind in the amount of $109 million. “Statement from PRAC Chair Michael E. Horowitz Following Guilty Pleas in $109 Million Pandemic Fraud Investigation Supported by the Pandemic Analytics Center of Excellence” PandemicOversight.gov, March 31, 2025, https://pandemicoversight.gov/news/articles/statement-from-prac-chair-following-guilty-pleas-in-109-million-pandemic-fraud-investigation-supported-by-pace.

[16]GAO, Digital Services: Considerations for a Federal Academy to Develop a Pipeline of Digital Staff, GAO‑22‑105388, (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 19, 2021).