CYBER DIPLOMACY

The Bureau of Cyberspace and Digital Policy’s Efforts to Advance U.S. Interests

Statement of Latesha

Love-Grayer, Director

International Affairs and Trade

Before the Subcommittee on Europe, Committee on Foreign Affairs, House of Representatives

For Release on Delivery Expected at 2:00 p.m. ET

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Latesha Love-Grayer at lovegrayerl@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-108445, a testimony before the Subcommittee on Europe, Committee on Foreign Affairs, House of Representatives

The Bureau of Cyberspace and Digital Policy’s Efforts to Advance U.S. Interests

Why GAO Did This Study

As international trade, communication, and critical infrastructure grow more dependent on cyberspace and digital technology, the U.S. and its allies face intensifying foreign cyber threats in critical areas. Foreign governments and non-state actors are increasingly using cyberspace as a platform from which to target critical infrastructure and U.S. citizens. This undermines democracies and international institutions and organizations. It also undercuts fair competition in the global economy by stealing ideas when they cannot create them. CDP’s mission is to promote U.S. national and economic security by leading, coordinating, and elevating foreign policy on cyberspace and digital technologies.

This statement discusses:

· the evolution of cyber diplomacy at State that led to the eventual creation of CDP, including the status of recommendations GAO made during its creation;

· how the bureau has organized itself to accomplish cyber diplomacy goals and the types of efforts it undertakes; and

· challenges the bureau faces in fulfilling its goals.

This statement is based on three GAO reports related to State’s cyber diplomacy programs—GAO-20-607R, GAO-21-266R, and GAO-24-105563. For that work, GAO analyzed State documents and data and interviewed agency officials. For a full list of the reports, see Related GAO Products at the conclusion of this statement.

What GAO Found

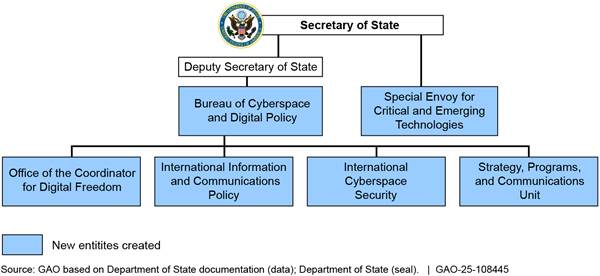

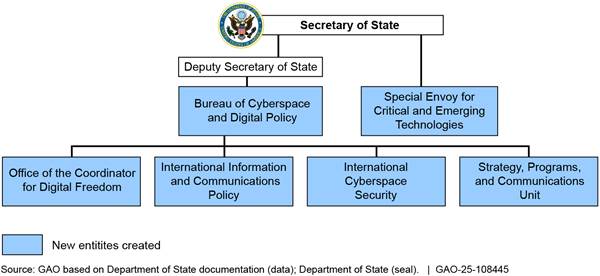

The Department of State leads U.S. government international cyber diplomacy efforts to advance U.S. interests in cyberspace. To help achieve those objectives, State established the Bureau of Cybersecurity and Digital Policy (CDP) in April 2022. In doing so, State addressed GAO’s recommendations to involve federal stakeholders and use data and evidence in planning for the bureau. State created the bureau to elevate cyberspace as an organizing concept for U.S. diplomacy by consolidating efforts and leadership of cyber-related activities into a single unit. CDP’s cyber diplomacy strategic objectives include building coalitions, strengthening capacity, and reinforcing norms.

New Entities State Created in 2022 to Elevate Cyber Priorities

In 2024, GAO reported that State conducts a range of diplomatic and foreign assistance activities aligned with U.S. cyber objectives. For example, State works to build coalitions of countries that share U.S. strategic objectives to (1) counter threats to the U.S. digital ecosystem and (2) reinforce global norms of responsible state behavior. CDP leads or coordinates many of these activities for State. For example, CDP rallies countries that share U.S. goals to coordinate policies that advance an open, free, global, interoperable, reliable and secure internet. CDP also facilitates bilateral diplomacy efforts through activities such as interagency whole-of-government cyber dialogues, which involve communication with partner nations.

GAO also reported that CDP faced ongoing organizational challenges, including clarifying roles, hiring staff, and ensuring it had the expertise needed to carry out its goals. Although cyber responsibilities are defined under the new structure, roles remain deliberately shared across government, making clarification an ongoing challenge. CDP was also working to clarify State’s role in the interagency process and maintain its lead in cyber diplomacy. CDP officials noted that defining roles across overlapping issues and sustaining internal communication and visibility remain key challenges, especially given the broad scope of cyber issues. Ensuring the bureau has trained staff to carry out its goals may also be a challenge. State must effectively navigate these challenges for CDP to achieve its stated goals.

Chairman Self, Ranking Member Keating, and Members of the Subcommittee,

Thank you for the opportunity to discuss our work on the Bureau of Cyberspace and Digital Policy (CDP), which leads, coordinates, and elevates foreign policy on cyberspace and digital technologies for the Department of State. As international trade, communication, and critical infrastructure grow more dependent on cyberspace and digital technology, the U.S. and its allies face intensifying foreign cyber threats in these and other critical areas. Foreign governments and non-state actors are increasingly using cyberspace as a platform for irresponsible behavior from which to:

· target critical infrastructure and U.S. citizens,

· undermine democracies and international institutions and organizations, and

· undercut fair competition in the global economy by stealing ideas when they cannot create them.

Aggressive cyberattacks on civilian infrastructure as well as government systems illustrate this risk. At the same time, the global arena presents positive opportunities for the U.S. to instill key values into the digital ecosystem, including the belief in the potential of digital technologies to promote connectivity, democracy, peace, the rule of law, sustainable development, and the enjoyment of human rights and fundamental freedoms. GAO has designated information security as a government-wide high-risk area since 1997.[1] This high-risk area was expanded in 2003 to include protecting the cybersecurity of critical infrastructure.[2]

State leads U.S. government international efforts to advance U.S. interests in cyberspace. According to State, these efforts are identified as “cyber diplomacy” activities, which cover a wide range of U.S. interests in cyberspace. These include cybercrime, cybersecurity, digital economy, international development and capacity building, internet freedom, and internet governance. Its cyber diplomacy strategic objectives include building coalitions, strengthening capacity, and reinforcing norms. To help achieve those objectives, State established CDP in April 2022.

As Congress considers State’s reauthorization, my statement today is intended to help inform the discussions about State’s efforts to advance cyber diplomacy, based on our prior assessments. Specifically, I will discuss the evolution of cyber diplomacy at State that led to the eventual creation of CDP, including the status of recommendations we made during its creation; how the bureau has organized itself to accomplish cyber diplomacy goals and the type of efforts it undertakes; and challenges the bureau faces in fulfilling its goals.

This statement is based primarily on reports published from September 2020 to January 2024 related to State and its cyber diplomacy programs. For those reports, we analyzed State documents and data related to the programs we reviewed, and we interviewed agency officials. We made two recommendations in the reports covered by this statement, both of which State has since implemented.

More detailed information on the objectives, scopes, and methodologies for that work can be found in the issued reports listed in Related GAO Products at the conclusion of this statement. We conducted the work on which this statement is based in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

State’s Cyber Diplomacy Activities Have Evolved

State leads U.S. government international efforts to advance the full range of U.S. interests in cyberspace, which include coordinating with other federal agencies, such as the Departments of Commerce, Defense, Energy, Homeland Security, Justice, and the Treasury, to advance the cyber priorities and interests of the nation. State’s efforts to advance U.S. interests in cyberspace have evolved over the years, including more recently in response to GAO’s recommendations:

· In 2011, State established the Office of the Coordinator for Cyber Issues in the Office of the Secretary to lead the department’s global diplomatic engagement on cyber issues and to serve as liaison to other federal agencies that work on cyber issues.

· In 2016, the Department of State International Cyberspace Policy Strategy affirmed the elevation of cyberspace policy as a foreign policy imperative and the prioritization of State’s efforts to mainstream cyberspace policy issues in its diplomatic activities.[3]

· In 2018, pursuant to Executive Order 13800, State led the development of an international engagement strategy in coordination with other federal agencies to strengthen the U.S. government cooperation with other countries and international organizations to address shared threats in cyberspace.[4]

· In January 2019, members of Congress introduced the Cyber Diplomacy Act of 2019, which would have established a new office to lead State’s international cyberspace efforts that would consolidate cross-cutting efforts on international cybersecurity, digital economy, and internet freedom, among other cyber diplomacy issues.[5]

· In June 2019, State notified Congress of its intent to establish a new bureau that would focus more narrowly on cyberspace security and the security aspects of emerging technologies.

In September 2020, we reported on State’s plans at that time to establish a cyber bureau.[6] We found that State had not involved other federal agencies that contribute to international cyber diplomacy in the development of those plans, contrary to leading practices of governmental reform. We recommended that State involve relevant federal agencies in their plans to establish a cyber bureau to obtain their views and identify potential risks.

Taking our recommendation and previous work into consideration, in May and June of 2021, State met with senior officials from relevant federal agencies, including the Departments of Defense, Commerce, and Homeland Security as well as officials from the National Security Council and the Office of the National Cyber Director. During these consultations, State obtained these agencies’ views and identified risks, implementing our recommendation.

In our January 2021 report, we found that State had not demonstrated that it had used data and evidence to develop its proposal.[7] Without data and evidence, State lacked assurance that its proposal would effectively set priorities and allocate appropriate resources for the bureau to achieve its intended goals. We recommended that State use data and evidence to justify its current proposal or any new proposal to establish a cyber bureau.

In response to our recommendation, State conducted:

· qualitative internal assessments to identify staffing and skills gaps, and

· evidence- and data-based reviews with internal and external stakeholders over a months-long process to develop proposals to establish the bureau.

Implementing data and evidence-based reviews helped to ensure that State’s final proposal would achieve its intended results.

State’s Reform Effort Has Helped to Elevate Cyber Diplomacy Goals

State Established a New Bureau to Prioritize Cyber Diplomacy

In April 2022, State established a new Bureau of Cyberspace and Digital Policy (CDP) with a mission to address national security challenges, economic opportunities, and implications to U.S. values associated with cyberspace, digital technologies, and digital policy. State created CDP, headed by a Senate-confirmed Ambassador-at-Large, to elevate cyberspace as an organizing concept for U.S. diplomacy by consolidating efforts and leadership of cyberspace-related activities into a single unit.

The U.S. Ambassador-at-Large for Cyberspace and Digital Policy serves as the principal cyberspace policy official at State and advisor to the Secretary on cyber and digital issues, fulfilling high-level strategic objectives. According to State officials, elevating the CDP office to a bureau with ambassador-level leadership has enhanced U.S. global engagement and raised the visibility of cyber diplomacy.

For example, in 2024, the Ambassador represented the United States in a trilateral cyber and digital dialogue with Japan and the Philippines, advancing U.S. positions on international cyberspace stability, data security and privacy, and cyber and digital capacity building in Asia. According to State officials, CDP’s bureau status also brought senior-level support, increased internal awareness and technical literacy, and allowed cyber policy to take a more prominent role within the department. Officials noted that these organizational changes helped cut through significant bureaucracy, elevated cyber priorities across bureaus, and drew heightened interest in cyber issues.

As shown in figure 1, CDP contains three policy units and a strategic planning unit:

Figure 1: New Entities State Created in 2022 to Elevate Cyber Priorities

· Office of the Coordinator for Digital Freedom: supports State’s work on privacy, government intervention, human rights, and civic engagement to promote global internet freedom.

· International Information and Communications Policy: works to promote competitive and secure networks, including 5G, and to protect telecommunication services and infrastructure through licensing, sanctions enforcement, and supply chain security.

· International Cyberspace Security: leads State’s efforts to promote cyberspace stability and security, including diplomatic engagement on international cyberspace security in multilateral, regional, and bilateral forums.

· Strategy, Programs, and Communications Unit: responsible for the Bureau’s strategic planning, public diplomacy, media, legislative affairs activities, and manages its foreign assistance programs via the Digital Connectivity and Cybersecurity Partnership.

CDP is funded from State’s primary operating account, Diplomatic Programs, and annually requests funds from the Diplomatic Policy and Support category, which supports the operational programs of the functional bureaus. In both fiscal years 2023 and 2024, State allocated about $24 million for CDP to support the bureau and 108 positions. In its fiscal year 2025 budget request, State requested about $25 million for CDP and to fund two new positions.

In January 2023, after the establishment of the Bureau, State also established the Office of the Special Envoy for Critical and Emerging Technology within the Office of the Secretary (S/TECH) to integrate critical and emerging technologies into U.S. foreign policy and diplomacy. S/Tech leads the development of strategy on the range of priority technologies including AI, quantum, and biotechnology, and coordinates State’s internal work on these topics. CDP reports to the Deputy Secretary, and S/TECH reports directly to the Secretary.

CDP Leads Several State Cyber Diplomacy and Foreign Assistance Initiatives

In 2024, we reported that State conducts a range of diplomatic and foreign assistance activities aligned with U.S. cyber objectives.[8] CDP leads or coordinates several of these activities. For example, State works to build coalitions of countries that share U.S. strategic objectives to (1) counter threats to the U.S. digital ecosystem and (2) reinforce global norms of responsible state behavior. CDP rallies countries that share U.S. goals to coordinate policies that advance an open, free, global, interoperable, reliable and secure internet. These efforts include engaging with the European Union Trade and Technology Council on critical and emerging technologies and with the European Commission to develop shared principles for 6G, a wireless communication network that will succeed 5G.[9]

State officials told us that CDP also facilitates bilateral diplomacy efforts to achieve desired outcomes through activities such as interagency whole-of-government cyber dialogues, which involve communication with partner nations to discuss common interests. According to State officials, such engagement encourages global coordination on a collective strategy to achieve common policy outcomes.

For example, in 2022, State worked with Denmark to advance the Copenhagen Pledge on Tech for Democracy (the Pledge) that counters digital authoritarianism across the globe and advances digital freedom. Following the initial bilateral effort, the Pledge enlisted signatories consisting of civil society organizations, private sector entities, and governments from over 100 countries, advancing goals and values endorsed by the U.S. related to the responsible use of technology.

In addition, CDP works with other agencies through formal interagency agreements and informal processes to leverage expertise and develop a whole-of-government approach to executing key cyber diplomacy activities, including interagency agreements with the Departments of Commerce, Interior, Defense, Homeland Security, the Federal Communications Commission, and the U.S. Agency for International Development. Many of these activities have focused on promoting capacity building, technical assistance, and training for international partners.

Other State Bureaus Lead Cyber-related Initiatives

Other bureaus also lead cyber-related initiatives. For example, State’s Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor (DRL) established the Freedom Online Coalition (FOC) in 2011, a multilateral forum to build consensus and focus attention on internet freedom. Officials from CDP told us that they collaborate with DRL on relevant issue areas and may provide support by contributing subject matter expertise on specific work. For example, State led negotiations on the adoption of a FOC joint statement condemning Iran’s internet shutdowns during widespread protests in fall 2022.

In another example, State’s Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL) leads State’s efforts to combat cybercrime. INL led the U.S. interagency effort along with experts in cybercrime policy, technology, and law enforcement from other U.S. agencies to engage with and influence negotiations on a UN cybercrime treaty adopted in 2024.[10] INL also provided technical and other assistance, such as funding for the Council of Europe cybercrime office, which assists developing countries in joining the Budapest Convention on Cybercrime.[11]

INL contributes funding to the Octopus Project, a Council of Europe cybercrime program established in 2014 to strengthen developing countries’ laws to be consistent with the Budapest Cybercrime Convention. This initiative is ongoing and delivers training and technical assistance to developing countries, enabling them to request accession to the Convention. State officials said that providing such foreign assistance helps countries adopt necessary infrastructure protections.

CDP Faced Challenges

In January 2024, we reported that CDP faced organizational challenges that it was still working to address, such as clarifying roles. According to State officials, although responsibilities for cyber issues are defined under the new structure, roles remain deliberately shared and complementary department-wide, making clarification an ongoing challenge.

Officials also noted that because cyber issues may be relevant to almost any aspect of diplomacy, communication within State to ensure awareness and visibility of issues so that expertise is fully utilized is a key, related challenge. For example, DRL and CDP’s Digital Freedom Unit cover similar areas, such as free speech on and fair access to the internet. CDP’s role is to contribute expertise on tech policy, collaborate with other units to develop complementary positions, and engage with partner countries, whereas DRL advances internet freedom through diplomacy and funding civil society-led projects.

In addition, CDP officials told us that there are some areas of overlap between CDP and S/TECH, such as where AI policy intersects with broader internet governance concerns. They added that CDP’s work covers overarching cyber and digital topics and partnerships while S/TECH works to leverage international partnerships on emerging technology.

We also reported that CDP was working to clarify State’s role in the interagency process and to ensure State maintains the lead in cyber diplomacy and coordinates actions with other U.S. agencies. For example, State in 2023 led a delegation of officials from U.S. Cyber Command, the Office of the National Cyber Director, and the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency that met with Ukrainian Deputy Ministers and announced $37 million in non-military cyber assistance for Ukraine.

Another challenge CDP was working to address was hiring staff. According to State officials, CDP was staffed and operational as of 2023 but needed to train existing staff and hire more people to meet its growth plans. To address existing skills gaps, CDP implemented a knowledge sharing program covering areas such as international cybersecurity partnerships, digital freedom policy work, and interagency coordination. CDP also established a Cyber and Digital Policy Officer course at the Foreign Service Institute and is working to provide it virtually to staff worldwide. CDP’s goal was to ensure there is a trained Cyber and Digital Policy Officer at every embassy by the end of 2024.[12]

In addition, as of January 2024, State was establishing a mechanism to identify cyber skills department-wide, added fluency in cyber topics as a selection criterion for ambassadors, and launched an annual “Achievement in Tech Diplomacy” award. To address hiring needs, CDP was implementing and exploring additional hiring mechanisms and developing partnerships with industry, academia, and other agencies to create a talent pipeline. However, the Ambassador told us he recognized that competing with the private sector to hire staff with the right skill sets would be a challenge.

Shortly after we issued our report, State released the United States International Cyberspace and Digital Policy Strategy in May 2024. The strategy outlines four action areas to lead the interagency process for coordinating digital diplomacy, ensure consistency in policy and execution, and reinforce State’s leadership in international fora. It also emphasizes the importance of structured engagement with multistakeholder and multilateral bodies to avoid gaps that adversaries could exploit—aligning with CDP’s efforts to engage with other bureaus and external partners through both formal and informal mechanisms. The strategy also identifies specific actions to build cyber and digital capacity among our allies. For example, it outlines plans to strengthen cyber capacity through international partnerships and interagency collaboration.

Our prior work shows that implementing major transformations, such as those outlined in the strategy, can span several years and must be carefully and closely managed. State can look to our leading practices to help assess agency reform efforts to inform its ongoing implementation of the strategy, specifically those related to implementing the reforms and strategically managing the federal workforce.[13]

We have not assessed CDP’s progress toward achieving the goals outlined in the United States International Cyberspace and Digital Policy Strategy. Although CDP’s efforts to address its challenges described in our 2024 report appear to support the strategy’s implementation—such as participating in interagency coordination and initiating efforts to build a cyber talent pipeline—it is too early to determine whether these actions are contributing to measurable progress in the strategy’s four action areas. As the bureau continues to mature, additional time and evidence will be necessary to evaluate how effectively CDP is advancing priorities such as building digital capacity, promoting responsible state behavior in cyberspace, and aligning rights-respecting approaches to digital governance with international partners. Further, it will be important to determine how these goals align with the priorities of the new administration.

In conclusion, efforts to promote cyber diplomacy at State have evolved and the formation of CDP has led to higher visibility and prioritization of these efforts. However, challenges remain. According to State officials, clearly defining roles and responsibilities across overlapping issue areas continues to be an ongoing need, particularly given that cyber issues span nearly all aspects of diplomacy. Ensuring sustained internal communication and visibility across State, especially as CDP’s functions intersect with other bureaus, also remains an important challenge. Further, ensuring that the bureau has staff with the sufficient expertise to carry out its goals is also a challenge, particularly in light of efforts to consolidate State’s functions. These are challenges that the bureau will need to effectively navigate if it intends to effectively achieve its mission to lead, coordinate, and elevate U.S. foreign policy on cyberspace and digital technologies.

Chairman Self, Ranking Member Keating, and Members of the Subcommittee, this completes my prepared statement. I would be pleased to respond to any questions that you may have at this time.

GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments

If you or your staff have any questions about this testimony, please contact Latesha Love-Grayer, Director, International Affairs and Trade, at lovegrayerl@gao.gov. Contact points for our Office of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this statement. GAO staff who made key contributions to this testimony are Jim Reynolds (Acting Director), Rob Ball (Assistant Director), Benjamin L. Moser (Analyst-in-Charge), Mark Dowling, Thomas Friend, Meg McAloon, Donna Morgan, and Jina Yu. Staff who made key contributions to the reports cited in the testimony are identified in the source products.

Related GAO Products

Products Referenced in This Statement

Cyber Diplomacy: State Has Not Involved Relevant Federal Agencies in the Development of Its Plan to Establish the Cyberspace Security and Emerging Technologies Bureau, GAO‑20‑607R, (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 22, 2020).

Cyber Diplomacy: State Should Use Data and Evidence to Justify Its Proposal for a New Bureau of Cyberspace Security and Emerging Technologies, GAO‑21‑266R (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 28, 2021).

Cyber Diplomacy: State’s Efforts Aim to Support U.S. Interests and Elevate Priorities, GAO‑24‑105563 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 11, 2024).

Other Related Products

Cybercrime

Global Cybercrime: Federal Agency Efforts to Address International Partners’ Capacity to Combat Crime, GAO‑23‑104768 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 1, 2023).

Cybersecurity

High-Risk Series: Urgent Action Needed to Address Critical Cybersecurity Challenges Facing the Nation, GAO‑24‑107231 (Washington, D.C.: June 13, 2024).

Cybersecurity: National Cyber Director Needs to Take Additional Actions to Implement an Effective Strategy, GAO‑24‑106916 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 1, 2024).

Cybersecurity High-Risk Series: Challenges in Establishing a Comprehensive Cybersecurity Strategy and Performing Effective Oversight, GAO‑23‑106415 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 19, 2023).

Cybersecurity: State Needs to Expeditiously Implement Risk Management and Other Key Practices, GAO‑23‑107012 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 28, 2023).

IT Workforce

State Department: Additional Actions Needed to Address IT Workforce Challenges, GAO‑22‑105932 (Washington, D.C.; Jul. 12, 2022).

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[2]GAO, High-Risk Series: An Update, GAO‑03‑119 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 1, 2003).

[3]Department of State International Cyberspace Policy Strategy, March 2016. Accessed October 22, 2019. www.2009‑2017.state.gov/documents/organization/255732.pdf.

[4]Exec. Order 13800, 82 Fed. Reg. 22391 (May 16, 2017); and Department of State, Office of the Coordinator for Cyber Issues, Recommendations to the President on Protecting American Cyber Interests through International Engagement, May 31, 2018. www.state.gov/wp‑content/uploads/2019/04/Recommendations‑to‑the‑President‑on‑Protecting‑American‑Cyber‑Interests‑Through‑International‑Engagement.pdf.

[5]Cyber Diplomacy Act of 2019, H.R. 739, 116th Cong. (2019). The House of Representatives passed a similar version of the bill during the 115th Congress, see Cyber Diplomacy Act of 2017, H.R. 3776, 115th Cong. (2017).

[6]See GAO, Cyber Diplomacy: State Has Not Involved Relevant Federal Agencies in the Development of Its Plan to Establish the Cyberspace Security and Emerging Technologies Bureau, GAO‑20‑607R, (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 22, 2020).

[7]GAO, Cyber Diplomacy: State Should Use Data and Evidence to Justify Its Proposal for a New Bureau of Cyberspace Security and Emerging Technologies, GAO‑21‑266R (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 28, 2021).

[8]GAO, Cyber Diplomacy: State’s Efforts Aim to Support U.S. Interests and Elevate Priorities, GAO‑24‑105563 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 11, 2024).

[9]6G is expected to launch in 2030. 6G will have enhanced scalability, greater use of the radio spectrum and dynamic access to different connection types compared to 5G. This will enable greater reliability and reduce drops in connection, which is critical to support advanced technologies such as drones and robots.

[10]A/Res/79/243 (Dec. 31, 2024).

[11]The Budapest Convention is a multilateral treaty that addresses computer related crime. It is global in nature and opened to all countries for signature in 2001. Currently there are 78 parties to the convention. As the Convention is not near universal ratification, State officials told us that any country’s decision to accede is significant.

[12]As of March 2025, CDP had trained over 250 cyber/digital officers since 2023, according to a CDP official.

[13]GAO, Government Reorganization: Key Questions to Assess Agency Reform Efforts, GAO‑18‑427 (Washington, D.C.: June 13, 2018).