DEFENSE PRODUCTION ACT

Use and Challenges from Fiscal Years 2018 to 2024

Statement of William

Russell, Director,

Contracting and National Security Acquisitions

Before the

Subcommittee on

National Security, Illicit Finance, and International Financial Institutions,

House of Representatives

For Release on Delivery Expected at 10 a.m. ET

United States Government Accountability Office

A testimony before the Subcommittee on National Security, Illicit Finance, and International Financial Institutions, House of Representatives

For more information, contact: William Russell at russellw@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

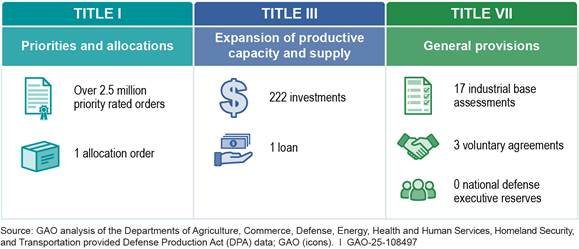

Congress enacted the Defense Production Act (DPA) in 1950 to grant the President expanded authority over critical production and economic policy to ensure the availability of industrial resources for national defense, paricularly during times of emergency. Three DPA title authorities are currently in effect:

Title I Priorities and Allocations. Allows delegated agencies and others to require companies in the U.S. to prioritize certain contracts or orders and allocate materials, services, and facilities to promote national defense.

Title III Expansion of Productive Capacity and Supply. Allows delegated agencies to provide investments such as purchases and purchase committments, as well as loans to suppliers, to sustain or expand production for national defense.

Title VII General Provisions. Allows delegated agencies to assess the industrial base, establish voluntary agreements with industry to foster collaboration, and create an executive reserve to aid federal agencies in times of national emergency, among other things.

Selected Agencies’ Use of DPA Authorities, Fiscal Years 2018 to 2024

GAO’s prior work found that agencies experienced a number of challenges when using the DPA authorities, such as difficulties tracking Title I priority rated contracts during the COVID-19 response. GAO made four recommendations in 2020 and 2021. The agencies have taken action to address all but one of the recommendations, which was for the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation to evaluate the effectiveness of its Title III loan program.

GAO’s report that publicly released today found additional challenges. For example, the Department of Defense (DOD) found that industry partners did not always understand how to apply priority ratings throughout the supply chain. DOD is conducting outreach to ensure an understanding of these Title I responsibilities. Additionally, the DPA government-wide coordinator, currently the Federal Emergency Management Agency, has not collected and shared lessons learned from DOD’s extensive use of Title III over multiple decades, but doing so could benefit other agencies.

Why GAO Did This Study

The DPA is a key tool to enable the domestic industrial base—including companies in the U.S. and certain allied nations—to maintain or increase production of defense resources.

Since the DPA was last authorized in 2018, Congress has appropriated at least $3.8 billion for DPA-related activities. Federal agencies have used DPA authorities for a variety of reasons, including to secure access to personal protective equipment like gloves and masks during the COVID-19 response.

This testimony is based on GAO’s DPA-related reports issued in November 2020 (GAO-21-108) and November 2021 (GAO-22-104511), and a report being issued today (GAO-25-107688). This testimony focuses on federal agencies’ use of the DPA authorities and the challenges these agencies faced.

GAO collected data from fiscal years 2018 through 2024 from the seven federal agencies that are delegated responsibility for implementing the DPA authorities, as identified in Executive Order 13603 issued in March 2012. These agencies are the Departments of Agriculture, Commerce, Defense, Energy, Health and Human Services, Homeland Security, and Transportation.

Additional details about the scope and methodology for GAO’s reports are included in those products.

What GAO Recommends

In its report issued today, GAO is recommending that the Federal Emergency Management Agency, a component of the Department of Homeland Security, collects and shares Title III lessons learned. The Department of Homeland Security concurred with this recommendation.

e T

June 12, 2025

Chairman Davidson, Ranking Member Beatty, and Members of the Subcommittee:

Thank you for the opportunity to discuss federal agencies’ use of the Defense Production Act (DPA) to secure critical goods and services. The DPA is a key tool to enable the domestic industrial base to maintain or increase production of defense resources.

While the DPA was first enacted nearly 75 years ago, its authorities continue to be relied on to bolster the industrial base today. Since its last reauthorization in fiscal year 2018, Congress has appropriated at least $3.8 billion for DPA-related activities, and agencies have used the DPA authorities for a variety of reasons including to secure access to personal protective equipment like gloves and masks during the COVID-19 response and to replenish U.S. supplies sent to Ukraine. In 2025 alone, the President has authorized agencies to use the DPA to reconstitute the naval industrial base and bolster domestic production of critical minerals.[1] Unless reauthorized, most DPA authorities will expire in September 2025.

My statement focuses on (1) agencies’ use of the DPA since its last reauthorization and (2) challenges agencies faced when using the DPA authorities. This statement is primarily based on our report publicly released today examining federal agencies’ use of the DPA.[2] My statement also includes information from past reports in 2020 and 2021 on the subject.

To understand how agencies used the DPA, we collected and analyzed data covering fiscal years 2018 to 2024 from the seven federal agencies delegated responsibility for implementing DPA authorities. These agencies are the Departments of Agriculture (USDA), Commerce, Defense (DOD), Energy (DOE), Homeland Security (DHS), Health and Human Services (HHS), and Transportation. To assess challenges and actions taken to address them, we reviewed documentation from the selected agencies across this same time period and interviewed relevant officials from each selected agency. Additional information can be found in the report we publicly released today.[3] Our 2020 and 2021 reports cited in this statement provide additional details on their objectives, scope, and methodologies.[4]

We conducted the work on which this statement is based in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

During the Korean War, Congress enacted the Defense Production Act of 1950, granting the President expanded authority over defense production and economic policy to ensure the availability of industrial resources for national defense.[5] Since it was enacted, Congress amended the DPA to broaden its applicability beyond military use and expanded coverage to include crises resulting from natural disasters or human-caused events. The definition of “national defense” in the act has been amended to also include emergency preparedness activities conducted pursuant to Title VI of the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act, and critical infrastructure protection and restoration.[6]

The DPA currently includes three Titles:

· Title I Priorities and Allocations. Title I allows agencies that are delegated authority by the President to require companies in the U.S. to prioritize certain contracts or orders and allocate materials, services, and facilities as necessary or appropriate to promote the national defense. Priority-rated contracts and orders take preference over unrated contracts or orders if a contractor cannot meet all required delivery dates. Allocation orders, on the other hand, control the distribution of materials, services, or facilities in the U.S. commercial market deemed necessary to support national defense.

· Title III Expansion of Productive Capacity and Supply through Financial Incentives. Title III allows agencies with authority delegated by the President to provide a variety of financial incentives to suppliers in the U.S. to meet national defense goals, including maintaining, restoring, and expanding the domestic industrial base.[7] Financial incentives can be made through investments such as purchases or purchase commitments as well as direct loans and loan guarantees.[8]

· Title VII General Provisions. Title VII allows delegated agencies to survey the industrial base for vulnerabilities, establish voluntary agreements with industry to foster collaboration while providing limited protection against antitrust laws, and create an executive reserve to include private sector personnel to aid federal agencies in times of national emergency, among other things.[9]

Through Executive Order 13603, issued in March 2012, the President delegated the ability to implement and exercise certain DPA authorities to various agencies as described in table 1.[10]

Table 1: Key Delegated Defense Production Act (DPA) Responsibilities in Executive Order 13603

|

Federal agency |

Key delegated responsibilities for implementing DPA authorities |

|

Department of Agriculture |

Title I: Administer the Agriculture Priorities and Allocations System to promote the national defense with respect to food resources, food resource facilities, and the domestic distribution of farm equipment and commercial fertilizer. |

|

Department of Commerce |

Title I: Administer the Defense Priorities and Allocations System to promote the national defense with respect to industrial resources. Title VII: Assess vulnerabilities across sectors of the industrial base. |

|

Department of Defense |

Title I: Determine the programs eligible to use a priority rating and administer the Water Priorities and Allocations System to promote the national defense with respect to water resources. Title III: Serve as the DPA fund manager, which includes reporting to the Congress each year regarding activities of the fund during the previous fiscal year. |

|

Department of Energy |

Title I: Determine the programs eligible to use a priority rating and administer the Energy Priorities and Allocations System to promote the national defense with respect to all forms of energy. |

|

Department of Health and Human Services |

Title I: Administer the Health Resources Priorities and Allocations System to promote the national defense with respect to health resources. |

|

Department of Homeland Security |

Overall: Provide government-wide coordination for DPA programs, which includes providing guidance to agencies assigned DPA functions, in consultation with such agencies. The Department of Homeland Security further delegated the execution of this responsibility to the Federal Emergency Management Agency. Title I: Determine the programs eligible to use a priority rating. Title VII: Develop the rules for establishing voluntary agreements and issue guidance for establishing and monitoring a national defense executive reserve. |

|

Department of Transportation |

Title I: Administer the Transportation Priorities and Allocations System to promote the national defense with respect to all forms of civil transportation. |

Source: GAO analysis of Executive Order 13603. l GAO‑25‑108497

Note: In addition to the delegated responsibilities described in the table, Executive Order 13603 authorizes the agencies listed above and others, such as the Departments of Justice and State, and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, to use the various DPA authorities.

Selected Agencies’ Use of DPA Authorities Fiscal Years 2018 to 2024

We found that the selected agencies used the authorities provided under the various DPA titles to varying degrees from fiscal years 2018 through 2024.[11] Title I was the most heavily used authority with five of the seven selected agencies collectively placing over 2.5 million priority rated orders during our time frame. Title III was used by three of the seven selected agencies—DOD, HHS, and DOE—to award 222 total investments and one loan with a combined value of $3.6 billion. Title VII was used collectively by five of the seven agencies to initiate or conduct assessments of the industrial base and establish voluntary agreements with industry.

Title I

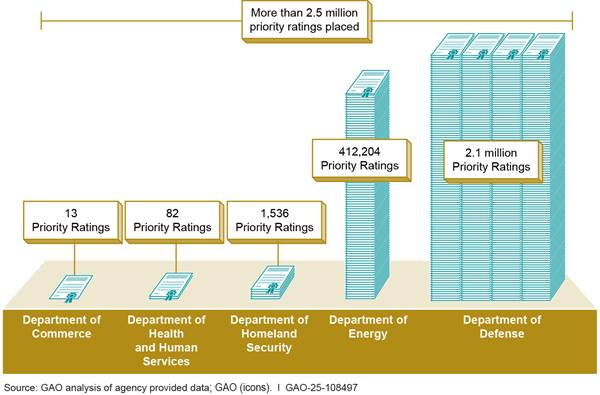

The selected agencies placed over 2.5 million priority ratings from fiscal years 2018 through 2024. Nearly all of the priority ratings placed were to support military goods and services. For example, DOD placed priority ratings to support the procurement of parts for aircraft and ships while DOE placed priority ratings supporting nuclear missile programs. Priority ratings were used to a lesser degree for non-military goods. For example, DHS placed about 1,500 priority ratings, nearly half of which were used to ensure the delivery of supplies needed to recover from natural disasters, according to Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) officials. Figure 1 provides an overview of the agencies’ estimated use.

Figure 1: Selected Agencies’ Total Estimated Number of Priority Ratings Placed, Fiscal Years 2018 to 2024

Note: Department of Defense officials provided a rough estimate of the number of priority ratings placed based upon the number of prime contracts it awarded each year during this time period. The Departments of Agriculture and Transportation did not report placing a priority rating during this time frame.

One allocation order was issued in April 2020 and carried out by HHS and FEMA to control the distribution of certain scarce or threatened health and medical resources—particularly personal protective equipment—within the commercial market during COVID-19.[12] The allocation order expired in June 2021.

Title III

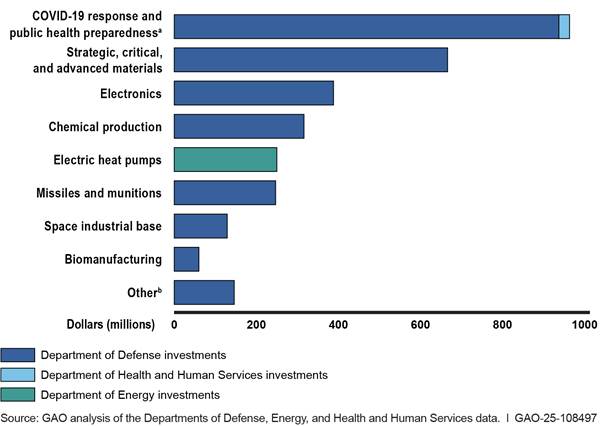

The selected agencies used Title III authorities to sustain the production capacity of defense suppliers during COVID-19, increase the domestic manufacturing capacity of existing suppliers, and bring new suppliers into the market. Collectively, DOD, HHS, and DOE made 222 investments valued at about $3.2 billion. DOD made 208 of these investments, while DOE and HHS made 12 and two, respectively. Figure 2 provides a breakdown of Title III investments by area and agency from fiscal years 2018 to 2024.

Figure 2: Selected Agencies’ Title III Investments by Area, Fiscal Years 2018 to 2024

aCOVID-19 response and public health preparedness included roughly $208 million in investments from the Department of Defense and $26 million from the Department of Health and Human Services for health resources, as well as $730 million in investments from the Department of Defense to support companies experiencing economic hardships resulting from the pandemic.

bOther includes investments for power storage and generation, shipbuilding, hypersonics, and directed energy, among others.

While the majority of these investments were still ongoing as of November 2024, 85 were completed. Nearly two-thirds of the completed investments with outcome information sustained existing capacity in the industrial base. For example, one of DOD’s Title III investments sustained capacity at a shipbuilding company when the local economy was negatively affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Other completed investments were used to either establish a new domestic source or expand existing domestic capacity. For example, DOD’s Title III investments expanded a U.S. company’s capacity to separate and process light rare earth materials that are used in a variety of items from electric vehicles to medical equipment.

DOD, with assistance from the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC), executed the one Title III loan from fiscal years 2018 through 2024.[13] The $410 million loan has a 20-year lifespan and was made in 2023 to a U.S. company to increase its manufacturing capacity for vaccines and critical medicines.

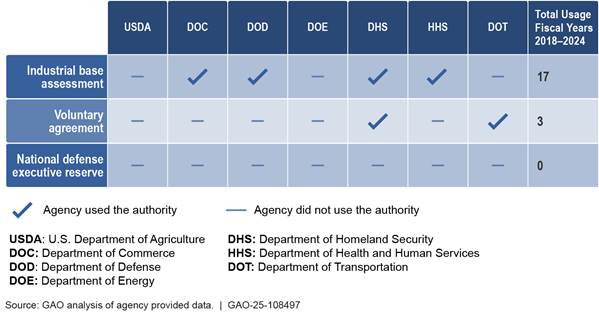

Title VII

The selected agencies used Title VII authorities to varying degrees from fiscal years 2018 through 2024, as shown in Figure 3.[14]

Figure 3: Selected Agencies’ Title VII Usage, Fiscal Years 2018 to 2024

Commerce has completed or is in the process of completing industrial base assessments for itself, other federal agencies, Congress, the President, and industry in areas such as weapon systems and microelectronics.[15] Additionally, two agencies—Transportation and FEMA—have used the voluntary agreement authority since fiscal year 2018. Transportation’s two voluntary agreements are intended to assure access to state-of-the-art cargo transport equipment and refueling vessels in case of mass mobilization.[16] FEMA’s voluntary agreement was established in 2020 to work with industry on manufacturing and distributing selected medical supplies and equipment during COVID-19. According to FEMA officials, this agreement is no longer active.

Challenges Using DPA Authorities and Agency Actions Toward Addressing Them

Our prior work, including our report publicly released today, found that federal agencies experienced a number of challenges when using the DPA authorities. In these reports, we made five recommendations to help ensure effective use of the DPA authorities and increase transparency moving forward. The agencies generally concurred with the recommendations, but not all have been fully implemented. Examples of challenges we identified include:

· Title I. We found that program offices and the companies receiving Title I rated orders from DOD and HHS did not always understand their responsibilities for passing the rating along to suppliers.[17] To address this, both DOD and HHS are engaged in educational outreach efforts to their contracting officers and companies receiving rated orders to help ensure an understanding of their roles and responsibilities for executing the rating.

In addition, in November 2020, we reported that agencies had problems tracking priority rated contracts during the COVID-19 response.[18] We recommended that the Office of Management and Budget develop agency reporting guidance to increase transparency on the use of priority ratings. The Office of Management and Budget took action to address this in July 2021 by creating a way to collect past and future COVID-19-related DPA Title I awards. Also in this report we found that HHS had not yet identified how to use the DPA to address risks to the U.S. healthcare supply chain and recommended that it do so. HHS concurred and by March 2023 had taken several actions to address this, including leveraging priority ratings for health resources and planning to establish its own Title III program to invest in the public health industrial base.

· Title III. We found that DOD does not currently have the expertise within its Defense Production Act Purchases Office to fully leverage Title III loan authorities.[19] From 2020 to 2022, DOD had an agreement with DFC to establish a program to award Title III loans on DOD’s behalf. In November 2021, we reported several challenges with this program.[20] For example, we found that DFC had not accounted for all costs or assessed the overall effectiveness of the program and recommended actions to address the challenges we identified. DFC concurred with our recommendation related to the costs of the Title III program. It did not concur with the recommendation to develop a plan to evaluate the program’s overall effectiveness, asserting that DOD or HHS were better positioned to do so. As of March 2025, DFC has taken actions to account for all costs of the program, but not to assess its overall effectiveness.

Fully implementing this recommendation could help ensure that the goals of any future Title III loan programs are being met. For example, while DOD’s original agreement with DFC has ended, Executive Order 14241 issued in March 2025 allows DFC to use DOD’s investment authorities, including the DPA, to bolster domestic critical mineral production. An understanding of the effectiveness of DFC’s loan program in response to COVID-19 may identify areas of improvement for using Title III loans for critical mineral production.

DOD officials told us that loans provide a better return on investment than the other Title III financial incentives since the government can get the benefit of increased production capacity—and recoup the funds. To leverage these benefits, DOD’s Office of Strategic Capital began offering loans outside of the DPA authority in January 2025 to eligible businesses in the critical technology sector, to expand production capabilities and modernize processes.

· Title VII. We found that FEMA faced challenges establishing its Title VII voluntary agreement in time to have a meaningful effect on the COVID-19 response. According to FEMA officials, the delays were due at least in part to minimum waiting periods—such as for Attorney General approval—that are currently required when establishing a voluntary agreement. To streamline the process in the future, FEMA proposed legislative changes to the DPA in November 2024 to provide flexibility in the minimum waiting periods. Congress will determine which, if any, of the proposals to include in its upcoming reauthorization of the DPA, currently set for fall of 2025.

We also found that FEMA is currently the agency responsible for coordinating DPA activities across the government but has not yet collected lessons learned from DOD, which has the longest history of awarding and overseeing Title III investments.[21] DOD has identified several practices to help increase the likelihood of a successful investment over its 30 years of experience awarding Title III investments. For example, one practice requires companies to invest their own funding in addition to DOD’s where practical. By contrast, HHS is newer to using Title III authorities and awarded its first investments in fiscal year 2024. We recommended that FEMA, as the current DPA government-wide coordinator, collect and share lessons learned as it could benefit agencies considering making additional Title III investments. DHS concurred with our recommendation and we will monitor any actions taken to address it.

Chairman Davidson, Ranking Member Beatty, and Members of the Subcommittee, this completes my prepared statement. I would be pleased to respond to any questions that you may have at this time.

GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments

If you or your staff have any questions about this testimony, please contact William Russell at russellw@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this statement. GAO staff who made key contributions to this statement are Cheryl Andrew (Assistant Director), Erin Carr (Analyst-in-Charge), Stephanie Gustafson, Lorraine Ettaro, Jean McSween, Mark Oppel, and Adam Wolfe.

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]Exec. Order No. 14241. 90 Fed. Reg. 13,673 (Mar. 20, 2025); and Exec. Order No. 14269. 90 Fed. Reg 15,635 (Apr. 9, 2025).

[2]GAO, Defense Production Act: Information Sharing Needed Improve use of Authorities, GAO‑25‑107688 (Washington, D.C.: June 12, 2025).

[4]GAO, Defense Production Act: Opportunities Exist to Increase Transparency and Identify Future Actions to Mitigate Medical Supply Chain Issues, GAO‑21‑108 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 19, 2020); U.S. International Development Finance Corporation: Actions Needed to Improve Management of Defense Production Act Loan Program, GAO‑22‑104511 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 17, 2021).

[5]Defense Production Act of 1950, Pub. L. No. 81-774, (1950) (codified at, 50 U.S.C. §§ 4501–4568).

[6]50 U.S.C. § 4552; Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act, Pub. L. No.93-288 (1974) (codified at 42 U.S.C. §§ 5121-5207), as amended by Pub. L. No. 100-707 (1988) and Pub. L. No. 117-255 (2022).

[7]Title III of Defense Production Act of 1950, Pub. L. No. 81-774, (codified at 50 U.S.C. §§ 4531–4535). Under certain conditions, companies in the U.K., Australia, and Canada may also receive DPA Title III investments.

[8]In addition to purchases and purchase commitments for industrial resources or critical technology items, Title III investments include subsidy payments for domestically produced materials and installation of equipment for government and privately owned industrial facilities to expand production.

[9]Title VII of Defense Production Act of 1950, Pub. L. No. 81-774 (codified at 50 U.S.C. §§ 4551–4568).

[10]Exec. Order No. 13,603. 77 Fed. Reg. 16,651 (Mar. 16, 2012).

[12]Presidential Memorandum, Memorandum on Allocating of Certain Scarce or Threatened Health and Medical Resources to Domestic Use, 85 Fed. Reg. 20,195 (Apr. 10, 2020).

[13]Department of Defense, U.S. International Development Finance Corporation, Memorandum of Agreement, June 22, 2020; Exec. Order No. 13922, 85 Fed. Reg. 30,583 (May 14, 2020). This agreement ended in 2022. In March 2025, the President delegated Title III authorities to the head of the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation and directed DOD to work with the corporation to develop a plan for leveraging DPA authorities to increase American production of minerals.

[14]Title VII includes other authorities outside of the scope of our review such as those exercised by the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States.

[15]DOD and Commerce each jointly initiated an industrial base assessment with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration to examine the rocket propulsion industrial base and the civil space industrial base, respectively.

[16]Transportation originally established these voluntary agreements 25 years ago.