MARITIME SECURITY

Actions Needed to Address Coordination and Operational Challenges Hindering Federal Efforts

Statement of Heather MacLeod, Director, Homeland Security and Justice

Before the Subcommittee on Border Security and Enforcement and the Subcommittee on Transportation and Maritime Security, Committee on Homeland Security, House of Representatives

For Release on Delivery Expected at 10:00 a.m. ET

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Heather MacLeod, MacLeodH@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-108525, a testimony to the Subcommittee on Border Security and Enforcement and the Subcommittee on Transportation and Maritime Security, Committee on Homeland Security, House of Representatives

Actions Needed to Address Coordination and Operational Challenges Hindering Federal Efforts

Why GAO Did This Study

Securing the nation's borders against unlawful movement of people, illegal drugs and other contraband, and terrorist activities is a key part of DHS's mission. While there is increased attention to the southwest land border, criminal organizations continue to use maritime routes to smuggle people, drugs, and weapons into the United States.

The U.S. government has identified transnational and domestic criminal organizations trafficking and smuggling illicit drugs as a significant threat to the public, law enforcement, and national security. In March 2021, GAO added national efforts to prevent, respond to, and recover from drug misuse to its High Risk List.

This statement discusses (1) key DHS resources to counter illicit maritime activities and (2) DHS operational challenges related to its efforts to counter illicit maritime activities. This statement is based primarily on 15 GAO reports published from July 2012 to April 2025.

What GAO Recommends

In prior work GAO made dozens of recommendations in the reports covered by this statement, including 23 to DHS. DHS generally agreed with the recommendations. As of May 2025, four of the recommendations have been implemented. GAO continues to monitor the agency’s progress in implementing open recommendations.

What GAO Found

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) employs assets—including aircraft and vessels—and personnel across the U.S. and abroad to secure U.S. borders, support criminal investigations, and ensure maritime security and safety. Relevant DHS components include the Coast Guard, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s Homeland Security Investigations.

In prior work, GAO identified coordination challenges that hinder U.S. efforts to confront illicit maritime activities and recommended actions to improve oversight, measure effectiveness, and build organizational capacity. For example:

· In March 2025, GAO found that Homeland Security Investigations had not fully implemented certain training requirements due to disagreements over training content with the Drug Enforcement Administration, with whom they coordinate. Without doing so, the agencies cannot ensure that their agents are properly trained to collaborate effectively on counternarcotics investigations.

· In February 2024, GAO found that DHS had not developed targets for its coordinated efforts to combat complex threats like drug smuggling and terrorism—limiting its ability to assess the effectiveness of its efforts.

· In April 2024, GAO found that the Coast Guard had not assessed the type and number of helicopters it requires to meet its mission demands, as part of an analysis of its assets. Doing so could help ensure it has the necessary aircraft capability to execute its missions in the coming decades.

Coast Guard Cocaine Seizure in the Caribbean Sea, September 2023

DHS components and their law enforcement missions are vital to confronting and mitigating illicit maritime activities. Addressing GAO’s recommendations on setting targets and managing assets and personnel will help ensure that DHS efficiently uses its available resources to carry out its law enforcement missions to protect our maritime borders.

Chairmen Guest and Gimenez, Ranking Members Correa and McIver, and Members of the Subcommittees:

I am pleased to be here today to discuss federal efforts to confront illicit maritime activities and challenges. Securing the nation’s borders against unlawful movement of people, illegal drugs and other contraband, and terrorist activities is a key part of the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) mission. While there is increased attention on the southwest land border, criminal organizations continue to use maritime routes to smuggle people, drugs, and weapons into the United States.

The U.S. government has identified trafficking of illicit drugs as a significant threat to the public, law enforcement, and national security. Use of these illicit drugs continues to impact tens of thousands of Americans each year. For example, provisional data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show about 80,000 drug overdose deaths during the 12-month period ending in December 2024.[1]

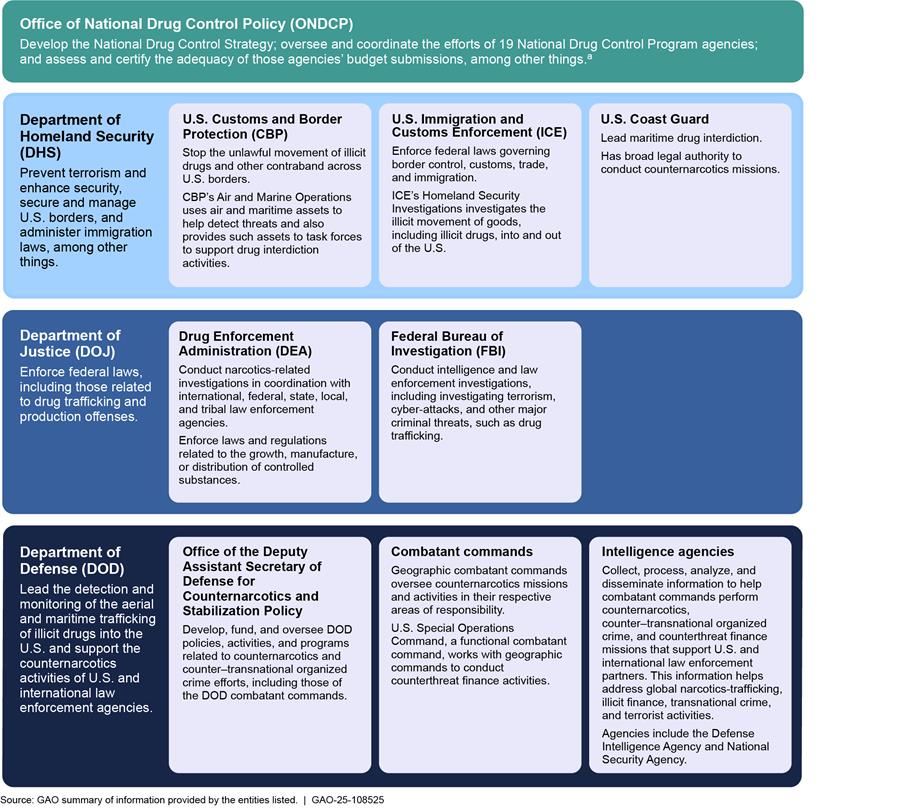

As shown in figure 1, multiple federal departments and agencies coordinate on efforts to counter illicit maritime activities. Among them is DHS, which is responsible for, among other things, securing U.S. borders to prevent illegal activity while facilitating legitimate trade and travel.[2]

Figure 1: Selected Federal Departments and Components with Counter Drug Missions and Activities

aThe Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP) is a component of the Executive Office of the President. In addition to the entities shown, ONDCP coordinates with the Departments of Health and Human Services, State, and the Treasury on counternarcotics activities.

The Coast Guard is a multi-mission, maritime military service within DHS. The Coast Guard describes itself as the lead federal maritime law enforcement agency and the only agency with both the authority and capability to enforce national and international law on the high seas, outer continental shelf, and inward from the U.S. Exclusive Economic Zone to inland waters.[3] Coast Guard responsibilities include detecting and interdicting contraband and illegal drug traffic; at sea enforcement of U.S. immigration laws and policies; enforcing our nation’s fisheries and marine protected areas laws and regulations; and other missions.[4] It coordinates with DOD in joint task forces to carry out its drug interdiction mission.[5] In particular, the Coast Guard is a major contributor of vessels and aircraft deployed to disrupt the flow of illicit drugs.[6]

The Coast Guard shares maritime law enforcement responsibilities with other DHS components, including U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s (CBP) Air and Marine Operations and U.S. Border Patrol, while U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) investigates the illicit movement of goods, including counternarcotics investigations, among other responsibilities.

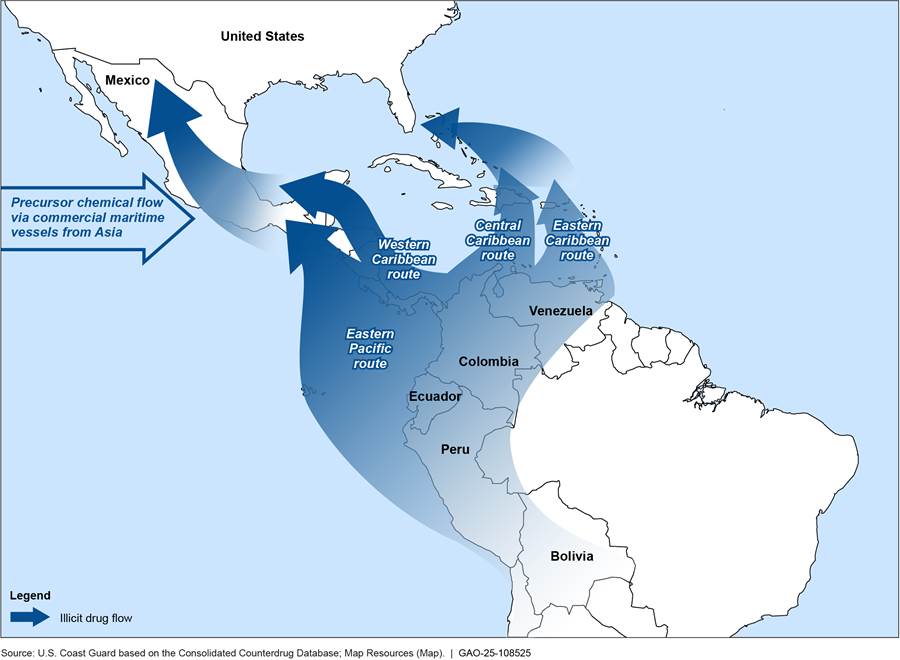

According to the Coast Guard, in fiscal year 2023, the agency intercepted more than 212,000 pounds of cocaine and 54,000 pounds of marijuana.[7] According to the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), the majority of the cocaine shipped to the U.S. travels on maritime routes from South America and through the eastern Pacific Ocean and Caribbean Sea.[8] Additionally, precursor chemicals may be shipped from Asia to Mexico, sometimes as legitimate commerce, where they may be combined into fentanyl or other controlled substances.[9] Figure 2 shows maritime and land routes for precursor chemical and illicit drug smuggling.

Figure 2: Maritime and Land Routes for Precursor Chemical and Illicit Drug Smuggling

Note: Precursor chemicals are chemicals or substances that may be intended for illicit drug production.

The U.S. government has identified illicit drugs, as well as the transnational and domestic criminal organizations that traffic and smuggle them, as significant threats to the public, law enforcement, and the national security of the U.S. Further, given challenges the federal government faces in responding to the drug misuse crisis, in March 2021, we added national efforts to prevent, respond to, and recover from drug misuse to our High Risk List.[10] Specifically, we identified several challenges with the federal government’s response to drug misuse, such as the need for more effective implementation and monitoring, and related ongoing efforts to address the issue, including law enforcement and drug interdiction.

My statement today discusses (1) key DHS resources to counter illicit maritime activities and (2) DHS operational challenges related to its efforts to counter illicit maritime activities. This statement is based primarily on 15 GAO reports published from July 2012 to April 2025. For the reports we cite in this statement, among other methodologies, we analyzed DOD, DHS, CBP, and Coast Guard policy, documentation, and data, and interviewed officials from agency headquarters and selected field units. More detailed information on our scope and methodology can be found in the reports we cite in this statement.

For this statement, we reviewed information on the status of agency implementation of selected recommendations through May 2025. In addition, we reviewed Coast Guard budget and performance documents since 2018 to determine the extent the service reported meeting its drug interdiction performance goals from fiscal years 2014 through 2024. We also analyzed Coast Guard operational hour data for each of its 11 statutory missions, from fiscal years 2015 through 2024. We found these data to be sufficiently reliable to report Coast Guard operational hours for aircraft and vessels by statutory mission. To determine the Coast Guard’s operating expenses, we reviewed the service’s Mission Cost Model operating expense estimates for its 11 statutory missions. We found these data to be sufficiently reliable to report Coast Guard operating expense estimates for its statutory missions.

We conducted the work on which this statement is based in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

DHS Deploys Aircraft, Vessels, and Personnel to Address Illicit Maritime Activities

DHS employs assets—including aircraft and vessels—and personnel across the U.S. and abroad to secure U.S. borders, support criminal investigations, and ensure maritime security and safety. Relevant DHS components include the Coast Guard, CBP, and HSI. Their air and marine missions vary depending on operating location.[11]

Coast Guard Resources

The Coast Guard is responsible for conducting 11 statutory missions, three of which are maritime law enforcement missions codified as homeland security missions—drug interdiction, migrant interdiction, and other law enforcement (which includes preventing illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing). In some cases, the Coast Guard coordinates its law enforcement missions with interagency partners.

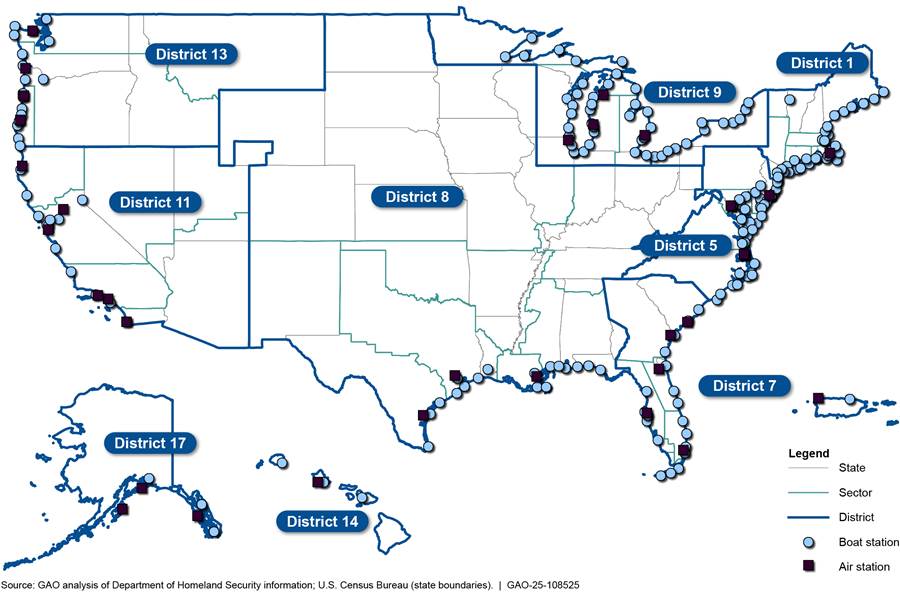

The Coast Guard operates a fleet of about 200 fixed- and rotary-wing aircraft, with more than 1,600 boats and 250 cutters.[12] As of fiscal year 2024, it employs approximately 55,500 personnel—including active duty, reserve, and civilian.[13] In addition, the Coast Guard’s shore infrastructure is comprised of nearly 40,000 assets, which consist of various types of buildings and structures.[14] For example, within its shore operations asset line, the Coast Guard maintains over 200 stations along U.S. coasts and inland waterways to carry out its search and rescue operations, as well as other missions, such as maritime security.[15] Figure 3 shows Coast Guard operating locations across the country, as of September 2020.

Figure 3: U.S. Coast Guard Air and Marine Operating Locations by District, as of September 2020

Note: Boat stations shown above also include small boat stations. Air stations shown above also include air facilities. The district numbers are not consecutive because some districts were consolidated to reflect the U.S. Coast Guard’s operational reorganizations since its creation in 1915.

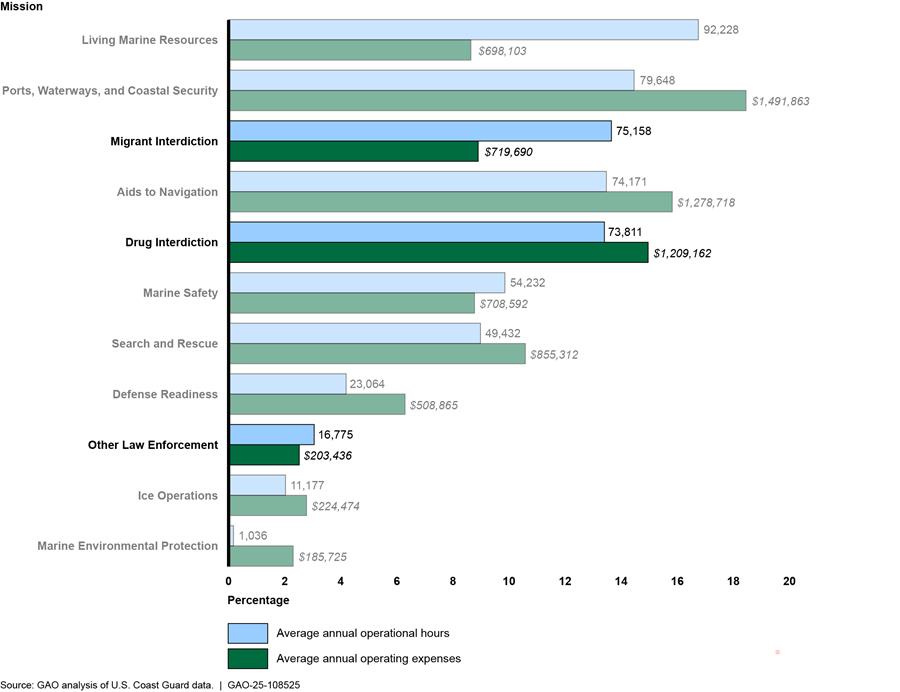

Our analysis of Coast Guard data showed more than a quarter of its total estimated operating expenses were for law enforcement missions related to homeland security. Specifically, from fiscal years 2015 through 2024, drug interdiction accounted for 15 percent of its average estimated operating expenses, migrant interdiction 9 percent, and other law enforcement (which includes preventing illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing) 3 percent. Figure 4 shows that the operating expenses of these three missions annually averaged more than $2.1 billion over this period.

Figure 4: Coast Guard Average Annual Vessel and Aircraft Operational Hours and Average Estimated Operating Expenses (in thousands), by Statutory Mission, Fiscal Years 2015 through 2024

CBP Resources

Within CBP, Air and Marine Operations and Border Patrol are the uniformed law enforcement arms responsible for securing U.S. borders between ports of entry in the air, land, and maritime environments.[16]

CBP’s Air and Marine Operations operates a fleet of 250 fixed- and rotary-wing aircraft and about 300 vessels to secure U.S. borders, as of March 2023.[17] The majority of CBP’s Air and Marine Operations’ activities support its law enforcement mission, including providing surveillance capabilities to detect and support the interdiction of illicit cross-border activity.[18] For example, in May 2023, CBP Air and Marine Operations personnel and Puerto Rico police forces seized over 4,000 pounds of cocaine found inside a vessel that landed on the southeastern coast of Puerto Rico. In addition, as of March 2024, CBP’s Border Patrol operates over 100 vessels along the coastal waterways of the United States and Puerto Rico and interior waterways common to the United States and Canada.[19]

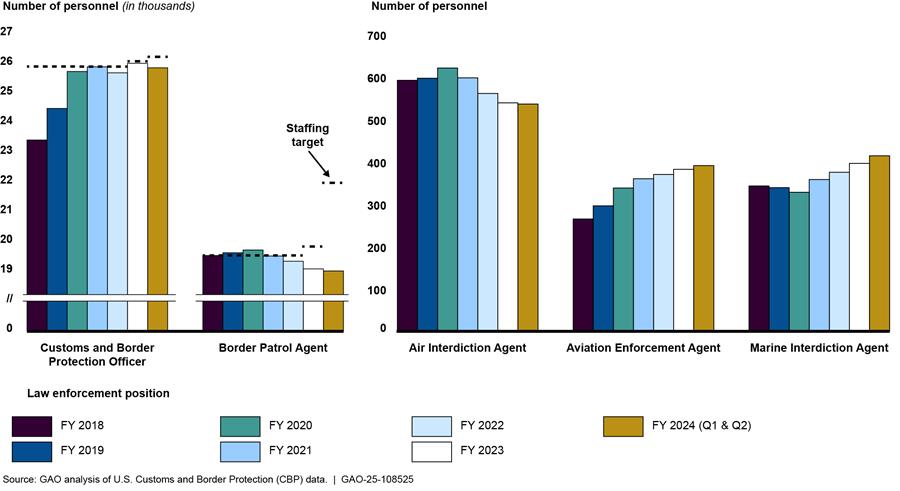

In September 2024 we reported on staffing levels for CBP law enforcement positions, including for Air and Marine Operations and Border Patrol.[20] We found that staffing levels for Air and Marine Operations positions varied from fiscal year 2018 through the first half of fiscal year 2024. In particular, staffing levels for the Air Interdiction Agent position generally decreased and staffing levels for Aviation Enforcement Agents and Marine Interdiction Agents generally increased during this period. Regarding Border Patrol, we found that it met its staffing targets from fiscal years 2018 through 2020 but fell short from fiscal year 2021 through the second quarter of fiscal year 2024. Figure 5 shows CBP’s Air and Marine Operations field structure, which is divided into three regions—northern, southeast, and southwest—and operating locations in these regions.

Figure 5: Air and Martine Operations Air and Marine Operating Locations by Region, as of September 2020

HSI Resources

HSI agents conduct federal criminal investigations into the illegal movement of people, goods, money, contraband, weapons, and sensitive technology into, out of, and through the U.S., including narcotics. Specifically, as it relates to counternarcotics investigations, HSI’s mission includes tracking, intercepting, investigating, and stopping illicit narcotics from flowing into the U.S. through targeting criminal networks; strengthening global partnerships; and enhancing domestic collaboration.

HSI is also involved in countering other illicit maritime activity. For example, in November 2024, HSI, in coordination with the Coast Guard and other federal agencies, investigated the Gulf Cartel’s involvement in criminal activities associated with illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing, human smuggling, and narcotics trafficking in the maritime environment. Illegal fishing is often a revenue stream for criminal organizations, according to HSI, and is also a threat to U.S. maritime security, as criminal organizations may use the same vessels for smuggling narcotics and humans across borders.

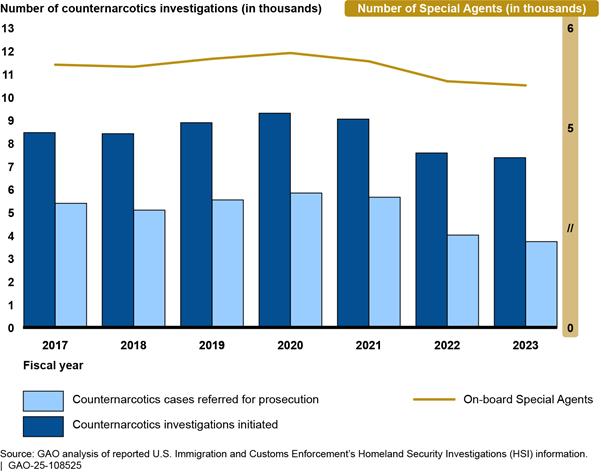

As shown in figure 6, over a 7-year period—fiscal years 2017 through 2023—HSI initiated over 58,000 counternarcotics investigations and referred over 35,000 counternarcotics cases for prosecution (an annual average of over 8,000 initiated investigations and over 5,000 cases referred for prosecution). During this period, HSI was annually staffed with about 5,600 special agents working on HSI’s law enforcement activities, including activities that work to combat illicit drugs in the U.S.

Figure 6: Number of HSI Counternarcotics Investigations, Cases Referred for Prosecution, and Special Agents in Its Workforce, Fiscal Years 2017 through 2023

Coordination and Operational Challenges Hinder Federal Efforts to Confront Illicit Maritime Activities in U.S. Waters

Coordination Challenges

Combating the trafficking of illicit drugs and other illicit maritime activities is a government-wide priority that requires a coordinated effort by federal departments and agencies. In prior work, we have identified coordination challenges that hinder U.S. efforts to confront illicit maritime activities and recommended actions to improve oversight, measure effectiveness, and build organizational capacity.

Improve oversight. DOD and DHS lead and operate certain task forces—Joint Interagency Task Force (JIATF)-South, JIATF-West, and DHS Joint Task Force-East.[21] For example, DHS components, including the Coast Guard and CBP, coordinate with DOD on counterdrug missions through the Joint Interagency Task Force South. For example, the task force is allocated assets, such as ships and surveillance aircraft, from DOD and DHS components, such as the Coast Guard, as well as from foreign partners. The task force coordinates these assets, in conjunction with available intelligence, to detect and monitor the trafficking of illicit drugs, such as cocaine, being smuggled north on noncommercial maritime vessels across its area of responsibility.

In 2019, we reported that the task forces generally coordinated effectively using means that aligned with leading practices.[22] These included working groups and liaison officers, which helped to minimize duplication of missions and activities.

However, our recent work has shown that these task forces and DOD should improve coordination and assess their efforts.[23] In 2024, we made four recommendations to improve agencies’ assessment efforts, including two recommendations to DHS to improve oversight of Joint Task Force-East. DHS agreed with the recommendations, which remain open as of May 2025.[24] Fully implementing them is essential for making decisions about priorities, resource allocations, and strategies for improvements.

Measure effectiveness. The Coast Guard and DOD also collaborate to combat illicit maritime activities and mitigate risks in the Arctic region. According to the Coast Guard’s Arctic Strategy these risks range from increased militarization of the Arctic region and potential conflict with Russia or China, to the increased risk posed by greater shipping traffic, and potential damage to the marine ecosystem from illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing. Officials from the Coast Guard and DOD also told us they collaborate in several ways, including sharing relevant information and expertise, providing operational assistance and conducting joint exercises in the region. Further, they reported collaborating on the development of their respective Arctic strategies. However, we found in August 2024 that the Coast Guard’s Arctic Strategic Outlook Implementation Plan generally does not include mechanisms to measure progress on its Arctic efforts. This may make it difficult for the Coast Guard to plan activities, determine resource needs, assess its progress toward strategic objectives, and ensure its efforts are aligned with national efforts. As a result, we recommended that the Coast Guard include performance measures with associated targets and time frames in its implementation plan. The Coast Guard concurred with our recommendation, and we continue to monitor its progress.[25]

Build collaborative capacity through training. While HSI agents may obtain Title 21 authority in order to collaborate with DEA on certain investigations of illicit activities, interagency disagreement on training has hindered effectiveness.[26] DEA cross-designated an average of over 4,000 HSI agents per year with the authority to participate in counternarcotics investigations under Title 21 of the U.S. Code during fiscal years 2019 through 2023. Additionally, while DEA and HSI have taken some steps towards implementing their training requirements, they have not completed this effort due to disagreements over the content of the trainings.

In March 2025, we made three recommendations, including that DEA and ICE develop and implement the training.[27] Without jointly developing and implementing the training modules, DEA and HSI cannot ensure that their agents are properly trained to collaborate effectively with each other on counternarcotics investigations.

Operational Challenges

DHS assets, such as aircraft and vessels, and federal personnel are vital to confronting and mitigating illicit maritime activities. However, our prior work has found that the Coast Guard faces significant operational challenges balancing tradeoffs among its assets and personnel across its 11 statutory missions where more work needs to be done. By comparison, CBP has strategically addressed certain operational challenges, such as recruitment and retention, through incentive pay.

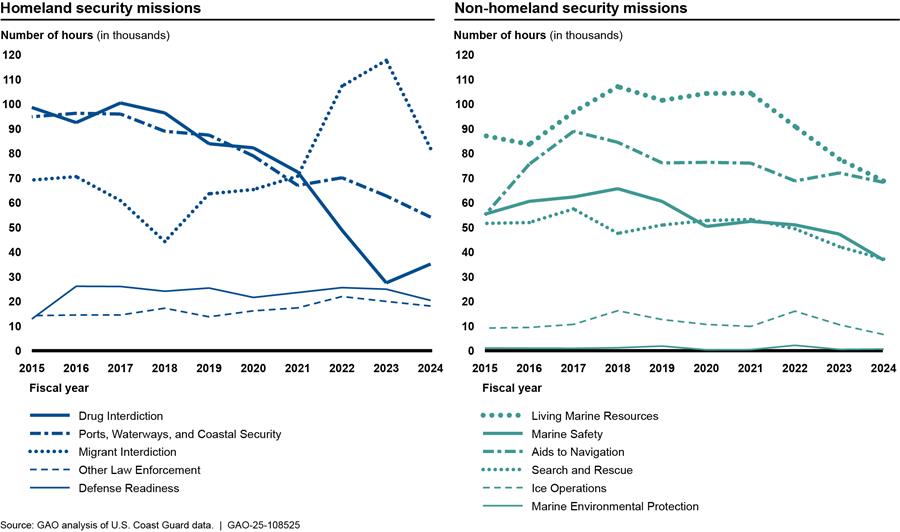

Coast Guard tradeoffs. The Coast Guard faces challenges balancing its varied mission priorities which have grown as it is called on to do more with its resources. In particular, in recent years, the Coast Guard has prioritized deploying its assets for its migrant interdiction mission. In doing so, it has reduced its operational activities to support other missions. The Coast Guard has not met its annual primary drug interdiction mission performance target in any year from fiscal years 2014 through 2024. Most notably, from fiscal years 2021 through 2023, the Coast Guard increased its migrant interdiction operations considerably in response to the highest maritime migration levels in the Caribbean in nearly 30 years. This tradeoff further challenges the Coast Guard’s ability to meet its drug interdiction mission demands.

As shown in figure 7, from fiscal years 2021 through 2023, the Coast Guard increased its operational hours for aircraft and vessels by 66 percent for its migrant interdiction mission, while decreasing its deployments for drug interdiction by 62 percent.[28]

Figure 7: Coast Guard Aircraft and Vessel Resources Deployed to Homeland Security Missions and Non-Homeland Security Missions, Fiscal Years 2015 through 2024

Coast Guard assets. Moreover, the condition of the assets the Coast Guard manages have been in a state of decline for decades. Our work has shown that the Coast Guard’s aircraft and vessels have faced readiness and availability challenges in carrying out their statutory missions.

For example, the Coast Guard relies on its Medium Endurance Cutters for its drug interdiction mission. However, we reported in July 2012 that Medium Endurance Cutters did not meet operational hours targets from fiscal years 2005 through 2011 and that declining operational capacity hindered mission performance.[29] In June 2023, we reported that Medium Endurance Cutters were not consistently meeting operational availability targets, and the Coast Guard noted that the declining physical condition of the cutters puts them at significant risk of decreased capability for meeting mission requirements.[30]

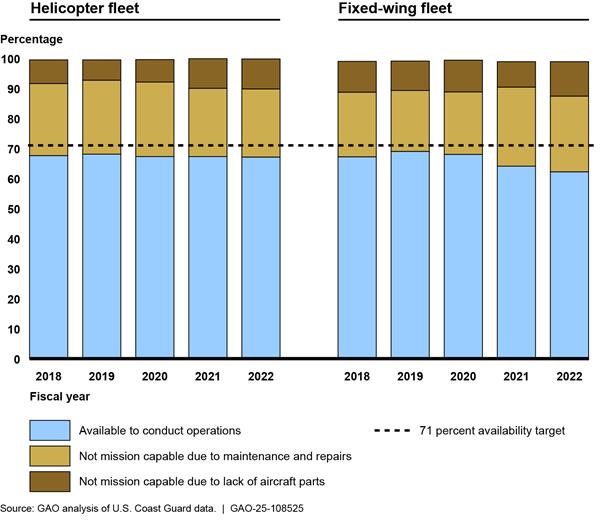

The Coast Guard’s asset readiness challenges are not limited to its cutters. In April 2024, we reported that the Coast Guard’s aircraft generally did not meet the Coast Guard’s 71 percent availability target during fiscal years 2018 through 2022, as shown in figure 8.[31]

Figure 8: Coast Guard Helicopter and Fixed-wing Fleet Availability, Fiscal Years 2018 through 2022

Coast Guard personnel. Compounding deteriorating assets is a shortage of personnel to operate them. The Coast Guard exceeded its recruiting goal in fiscal year 2024 for the first time in 5 years by taking actions such as increasing recruiting offices, marketing, and outreach efforts. It also revised enlistment eligibility standards and took steps to address a significant increase in medical waiver requests in recent years. However, despite these efforts, the Coast Guard remained about 2,600 enlisted members short of its workforce target.

The Coast Guard has taken steps to address its retention challenges through monetary and nonmonetary incentives and in 2022 began to require service members to complete a career survey to help identify key issues affecting retention. However, survey response rates have been consistently low. In April 2025, we recommended that the Coast Guard take actions to address response rates and develop a clear plan to gauge the performance of its initiatives.[32] The Coast Guard agreed with our recommendations, and we will monitor their implementation.

CBP personnel. We reported in September 2024 that in recent years, CBP has also generally fallen short of staffing targets for its law enforcement positions, as shown in figure 9.[33] We also reported that CBP has taken action to strengthen its recruitment, hiring, and retention efforts. For example, each of CBP’s operational components—the Office of Field Operations, U.S. Border Patrol, and Air and Marine Operations—have offered recruitment incentives for law enforcement positions.

In particular, in 2024 Border Patrol offered recruitment incentives of $20,000 per recipient, with an additional $10,000 for recipients stationed in remote locations. CBP has also offered retention incentives, relocation incentives, and special salary rates as part of its efforts to improve retention of law enforcement personnel. For example, Air and Marine Operations has offered retention incentives for positions and locations experiencing high rates of attrition. CBP anticipates a steep increase in attrition rates across all positions starting in 2027 because a significant number of its law enforcement personnel will become eligible to retire. CBP has a strategic plan to address this expected retirement surge, and retention- and morale-related efforts will be increasingly important to help mitigate the loss of these personnel.

Figure 9: Target versus Actual Staffing Levels for U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) Law Enforcement Positions, Fiscal Year 2018 through the Second Quarter of Fiscal Year 2024

Note: The Office of Field Operations determines staffing targets for U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) Officers by assessing available funding, statutory provisions, current staffing levels, and projected attrition. Border Patrol’s staffing targets are determined by authorized staffing levels that represent the number of agents supported by the component’s appropriations, informed by provisions of explanatory statements and other legislative documents accompanying annual appropriations. Executive Order 13767, which was in effect from January 2017 to January 2021, called for CBP to hire 5,000 additional Border Patrol Agents, subject to available appropriations. According to CBP officials, CBP was not appropriated funding to hire an additional 5,000 agents; therefore, they are not included in Border Patrol’s staffing targets. Air and Marine Operations does not have staffing targets for its three law enforcement positions. Fiscal year 2024 staffing levels are as of the end of the second quarter of the fiscal year.

In summary, DHS components and their law enforcement missions are vital to confronting and mitigating illicit maritime activities. Addressing our recommendations on setting performance measures and targets and managing assets and personnel will help ensure that DHS efficiently uses its available resources to carry out its law enforcement missions to protect our maritime borders.

Chairmen Guest and Gimenez, Ranking Members Correa and McIver, and Members of the Subcommittees, this completes my prepared statement. I would be pleased to respond to any questions that you may have at this time.

GAO Contacts and Staff Acknowledgments

If you or your staff have any questions about this testimony, please contact Heather MacLeod, Director, Homeland Security and Justice at MacLeodH@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this statement. GAO staff who made key contributions to this statement are Andrew Curry (Assistant Director), Ricki Gaber (Analyst-in-Charge), Dawn Hoff, Jay Berman, Michele Fejfar, Eric Hauswirth, Sierra Hicks, Paul Hobart, Sasan J. “Jon” Najmi, Ben Neverov, and Kevin Reeves.

Appendix I: Related Open Recommendations to the Department of Homeland Security as of May 2025

Coast Guard: Enhanced Data and Planning Could Help Address Service Member Retention Issues, GAO‑25‑107869 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 23, 2025).

· Recommendation: The Commandant of the Coast Guard should ensure that the Office of Workforce Requirements, Systems, and Analytics implements additional mechanisms to increase response rates for its Career Intention Survey.

· Recommendation: The Commandant of the Coast Guard should ensure that the Office of Workforce Requirements, Systems, and Analytics analyzes the potential for nonresponse bias in its Career Intention Survey results.

· Recommendation: The Commandant of the Coast Guard should ensure that the Talent Management Transformation Program Integration Office develops a clear plan, including how retention initiatives align with strategic objectives and time frames and milestones for implementation, to track progress and gauge program performance.

Combatting Illicit Drugs: Improvements Needed for Coordinating Federal Investigations, GAO‑25‑107839 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 5, 2025).

· Recommendation: The Director of ICE should work with the DEA Administrator to develop and implement the two training modules in accordance with their January 2021 agreement, using agreed-upon dispute resolution mechanisms as appropriate.

Coast Guard: Complete Performance and Operational Data Would Better Clarify Arctic Resource Needs, GAO‑24‑106491 (Washington, D.C.: Aug. 13, 2024).

· Recommendation: The Commandant of the Coast Guard should ensure that District 17 collects and reports complete information about resource use and mission performance in accordance with Coast Guard guidance.

· Recommendation: The Commandant of the Coast Guard should ensure that the Coast Guard’s Arctic implementation plan includes performance measures with associated targets and time frames for the action items described in the plan in accordance with Coast Guard guidance.

Coast Guard: Aircraft Fleet and Aviation Workforce Assessments Needed, GAO‑24‑106374 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 9, 2024).

· Recommendation: The Commandant of the Coast Guard should establish procedures requiring the Coast Guard to uniformly collect and maintain air station readiness data.

· Recommendation: The Commandant of the Coast Guard should establish a process to regularly evaluate Coast Guard-wide air station readiness data.

· Recommendation: The Commandant of the Coast Guard should assess the type of helicopters the Coast Guard requires to meet its mission demands, as part of an analysis of alternatives.

· Recommendation: The Commandant of the Coast Guard should assess the number of helicopters the Coast Guard requires to meet its mission demands, as part of a fleet mix analysis.

· Recommendation: The Commandant of the Coast Guard should assess and determine the aviation workforce levels it requires to meet its mission needs.

Department of Homeland Security: Additional Actions Needed to Improve Oversight of Joint Task Forces, GAO‑24‑106855 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 7, 2024).

· Recommendation: The Secretary of Homeland Security should ensure the Office of the Military Advisor develops and documents criteria for establishing a joint task force.

· Recommendation: The Secretary of Homeland Security should ensure the Office of the Military Advisor develops and documents criteria for terminating a joint task force.

· Recommendation: The Secretary of Homeland Security should ensure the Office of the Military Advisor, as it finalizes performance measures for Joint Task Force-East, establishes targets for those measures, as required.

· Recommendation: The Secretary of Homeland Security should ensure the Office of the Military Advisor develops and documents the methodology used in establishing the performance measures for Joint Task Force-East.

Coast Guard Acquisitions: Offshore Patrol Cutter Program Needs to Mature Technology and Design, GAO‑23‑105805 (Washington, D.C.: Jun. 20, 2023).

· Recommendation: The Commandant of the Coast Guard should ensure that Offshore Patrol Cutter (OPC) program officials develop a technology maturation plan for the davit prior to builder’s trials. This plan should identify potential courses of action to address davit technical immaturity, including assessing technology alternatives should the current davit continue to face development challenges, and a date by which the Coast Guard will make a go/no-go decision to pursue such a technology alternative.

· Recommendation: The Commandant of the Coast Guard should ensure that OPC program officials test an integrated prototype of the davit in a realistic environment prior to stage 1 builder’s trials.

· Recommendation: The Commandant of the Coast Guard should ensure that the OPC stage 2 program achieves a sufficiently stable design prior to the start of lead ship construction. In line with shipbuilding leading practices, sufficiently stable design includes 100 percent completion of basic and functional design, including routing of major distributive systems and transitive components that effect multiple zones of the ship.

Related GAO Products

Coast Guard: Enhanced Data and Planning Could Help Address Service Member Retention Issues, GAO‑25‑107869 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 23, 2025).

Combatting Illicit Drugs: Improvements Needed for Coordinating Federal Investigations, GAO‑25‑107839 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 5, 2025).

Coast Guard Shore Infrastructure: More Than $7 Billion Reportedly Needed to Address Deteriorating Assets, GAO-25-107851 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 25, 2025).

U.S. Customs and Border Protection: Efforts to Improve Recruitment, Hiring, and Retention of Law Enforcement Personnel, GAO‑24‑107029 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 25, 2024).

Coast Guard: Actions Needed to Address Persistent Challenges Hindering Efforts to Counter Illicit Maritime Drug Smuggling, GAO‑24‑107785 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 19, 2024).

Coast Guard: Complete Performance and Operational Data Would Better Clarify Arctic Resource Needs, GAO‑24‑106491 (Washington, D.C.: Aug. 13, 2024).

Counternarcotics: DOD Should Improve Coordination and Assessment of Its Activities, GAO‑24‑106281 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 16, 2024).

Coast Guard: Aircraft Fleet and Aviation Workforce Assessments Needed, GAO‑24‑106374 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 9, 2024).

Department of Homeland Security: Additional Actions Needed to Improve Oversight of Joint Task Forces, GAO‑24‑106855 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 7, 2024).

Coast Guard Acquisitions: Offshore Patrol Cutter Program Needs to Mature Technology and Design, GAO‑23‑105805 (Washington, D.C.: Jun. 20, 2023).

Coast Guard: Actions Needed to Better Manage Shore Infrastructure, GAO‑22‑105513 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 16, 2021).

Department of Homeland Security: Assessment of Air and Marine Operating Locations Should Include Comparable Costs across All DHS Marine Operations, GAO‑20‑663 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 24, 2020).

Drug Control: Certain DOD and DHS Joint Task Forces Should Enhance Their Performance Measures to Better Assess Counterdrug Activities, GAO‑19‑441 (Washington, D.C.: Jul. 9, 2019).

Coast Guard: Resources Provided for Drug Interdiction Operations in the Transit Zone, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands, GAO‑14‑527 (Washington, D.C.: Jun. 16, 2014).

Coast Guard: Legacy Vessels’ Declining Conditions Reinforce Need for More Realistic Operational Targets, GAO‑12‑741 (Washington, D.C.: Jul. 31, 2012).

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, reported provisional counts for 12-month ending periods are the number of deaths received and processed for the 12-month period ending in the month indicated. Drug overdose deaths are often initially reported with no cause of death (pending investigation) because they require lengthy investigation, including toxicology testing. As a result, reported provisional counts may not include all deaths that occurred during a given time and are subject to change.

[2]The Department of Defense (DOD) is the single lead agency responsible for detecting and monitoring the aerial and maritime transport of illegal drugs like cocaine and fentanyl into the U.S. 10 U.S.C. § 124.

[3]The term exclusive economic zone refers to an area up to 200 nautical miles from the territorial sea baseline where a country has sovereign rights to natural resources such as fishing and energy production.

[4]See 6 U.S.C. § 468.

[5]10 U.S.C. § 124 designates DOD as the single lead agency of the federal government for the detection and monitoring of aerial and maritime transit of illegal drugs into the U.S. The Coast Guard, within DHS, is the lead federal agency for interdiction of maritime drug smugglers in international waters. This is because the Coast Guard may make inquiries, examinations, inspections, searches, seizures, and arrests upon the high seas and waters over which the United States has jurisdiction to prevent, detect, and suppress violations of U.S. laws. See 14 U.S.C. § 522.

[6]Coast Guard aviation and vessel assets include a fleet of about 200 fixed- and rotary-wing aircraft, about 250 cutters, and more than 1,600 boats. GAO, Coast Guard: Aircraft Fleet and Aviation Workforce Assessments Needed, GAO‑24‑106374 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 9, 2024).

[7]Admiral Linda L. Fagan, Commandant, U.S. Coast Guard, The Coast Guard’s Fiscal Year 2025 Budget Request, testimony before the House of Representatives Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, Subcommittee on Coast Guard and Maritime Transportation, 118th Cong., 2nd sess., May 23, 2024.

[8]Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), 2020 National Drug Threat Assessment, DEA-DCT-DIR-008-21 (March 2021). The majority of known maritime drug flow is conveyed via noncommercial vessels through the Western Hemisphere Transit Zone—a 6 million square mile area of routes drug smugglers use to transport illicit drugs that includes the eastern Pacific Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, among other areas. See GAO, Coast Guard: Resources Provided for Drug Interdiction Operations in the Transit Zone, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands, GAO‑14‑527 (Washington, D.C.: Jun. 16, 2014).

[9]Precursor chemicals are chemicals or substances that may be intended for illicit drug production.

[10]See GAO, High-Risk Series: Dedicated Leadership Needed to Address Limited Progress in Most High-Risk Areas GAO‑21‑119SP (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 2, 2021). We issue an update to the High-Risk List every two years at the start of each new session of Congress. The most recent update was issued in February 2025. See GAO, High-Risk Series: Heightened Attention Could Save Billions More and Improve Government Efficiency and Effectiveness, GAO‑25‑107743 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 25, 2025).

[11]Coast Guard and CBP also coordinate on the deployment and allocation of assets and specialized personnel with the DOD to reduce the availability of illicit drugs by countering the flow of such drugs into the U.S.

[12]GAO‑24‑106374 and GAO, Coast Guard: Actions Needed to Address Persistent Challenges Hindering Efforts to Counter Illicit Maritime Drug Smuggling, GAO‑24‑107785 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 19, 2024).

[13]GAO, Coast Guard: Enhanced Data and Planning Could Help Address Service Member Retention Issues, GAO‑25‑107869 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 23, 2025).

[14]GAO, Coast Guard Shore Infrastructure: More Than $7 Billion Reportedly Needed to Address Deteriorating Assets, GAO-25-107851 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 25, 2025).

[15]GAO, Coast Guard: Actions Needed to Better Manage Shore Infrastructure, GAO‑22‑105513 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 16, 2021).

[16]CBP’s Office of Field Operations also has border security responsibilities, such as inspecting pedestrians, passengers, and cargo—including international mail and express cargo—at the more than 320 air, land, and sea ports of entry.

[17]CBP Air and Marine Operations owns and maintains CBP’s 290 vessels, including riverine vessels that are operated by the U.S. Border Patrol, as of March 2023. Jonathan P. Miller, Executive Director of Operations, Air and Marine Operations, CBP, Securing America’s Maritime Border: Challenges and Solutions for U.S. National Security, testimony before the House of Representatives Committee on Homeland Security, Subcommittee on Transportation and Maritime Security, 118th Cong., 1st sess., March 23, 2023.

[18]GAO, Department of Homeland Security: Assessment of Air and Marine Operating Locations Should Include Comparable Costs across All DHS Marine Operations, GAO‑20‑663 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 24, 2020).

[19]“Border Patrol Overview,” CBP, last modified: Mar. 4, 2024, https://www.cbp.gov/border-security/along-us-borders/overview.

[20]GAO, U.S. Customs and Border Protection: Efforts to Improve Recruitment, Hiring, and Retention of Law Enforcement Personnel, GAO‑24‑107029 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 25, 2024).

[21]An additional task force—Joint Task Force-North—consists solely of DOD personnel and does not generally operate in the maritime domain.

[22]See GAO, Drug Control: Certain DOD and DHS Joint Task Forces Should Enhance Their Performance Measures to Better Assess Counterdrug Activities, GAO-19-441 (Washington, D.C.: Jul. 9, 2019). As established, the DHS task forces aimed to, among other things, combat terrorism threats, the smuggling of illicit drugs, unlawful migration, and other security concerns along the southern border and approaches to the U.S.

[23]GAO, Counternarcotics: DOD Should Improve Coordination and Assessment of Its Activities, GAO‑24‑106281 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 16, 2024) and Department of Homeland Security: Additional Actions Needed to Improve Oversight of Joint Task Forces, GAO‑24‑106855 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 7, 2024).

[24]GAO‑24‑106855. DHS agreed with the two recommendations and identified ongoing and planned steps to address them. Actions include plans to review its performance measures for the task force and document the methodology used calculate such measures, including performance targets. See also GAO‑24‑106281.

[25]GAO, Coast Guard: Complete Performance and Operational Data Would Better Clarify Arctic Resource Needs, GAO‑24‑106491 (Washington, D.C.: Aug. 13, 2024).

[26]Under section 873 of Title 21 of the U.S. Code, DEA can cross-designate HSI agents with the authority to investigate the smuggling of controlled substances across U.S. international borders or through ports of entry.

[27]See GAO, Combatting Illicit Drugs: Improvements Needed for Coordinating Federal Investigations, GAO‑25‑107839 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 5, 2025). The agencies agreed with our recommendations. DHS described planned actions to address the recommendation to HSI, stating that HSI plans to work with DEA to develop and implement training modules.

[28]From fiscal years 2023 through 2024, Coast Guard resources deployed to support its migrant interdiction mission decreased, while Coast Guard resources deployed to support its drug interdiction mission remained at relatively low levels.

[29]GAO, Coast Guard: Legacy Vessels’ Declining Conditions Reinforce Need for More Realistic Operational Targets, GAO‑12‑741 (Washington, D.C.: Jul. 31, 2012).

[30]GAO, Coast Guard Acquisitions: Offshore Patrol Cutter Program Needs to Mature Technology and Design, GAO‑23‑105805 (Washington, D.C.: Jun. 20, 2023).

[31]GAO‑24‑106374. GAO found that the Coast Guard had not assessed the type and number of helicopters it requires to meet its mission demands, as part of an analysis of its assets, among other things.