DEFENSE ACQUISITION REFORM

Persistent Challenges Require New Iterative Approaches to Delivering Capability with Speed

Statement of Shelby S. Oakley, Director, Contracting and National Security Acquisitions

Before the Subcommittee on Military and Foreign Affairs, Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, House of Representatives

For Release on Delivery Expected at 10:00 a.m. ET

United States Government Accountability Office

A testimony before the Subcommittee on Military and Foreign Affairs, Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, House of Representatives

For more information, contact: Shelby S. Oakley at OakleyS@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

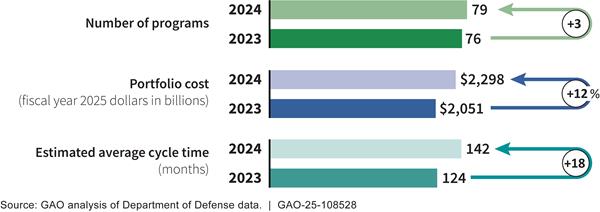

In June 2025, GAO reported that the Department of Defense (DOD) plans to invest nearly $2.4 trillion to develop and acquire 106 of its costliest weapon programs. Yet the expected time frame for major defense acquisition programs to provide warfighters with even an initial capability is now almost 12 years from program start. These time frames are incompatible with meeting emerging threats. While DOD and Congress have made efforts to identify efficiencies, more radical change is needed.

Major Defense Acquisition Programs Continue to Delay Capability Deliveries

DOD remains deeply entrenched in a traditional linear acquisition structure—characterized by rigid, sequential processes—that has proven inadequate in adapting to evolving threats and integrating emerging innovation. In a linear acquisition, the cost, schedule, and performance baselines are fixed early. Thus, programs develop weapon systems to meet fixed requirements that were set years in advance. This risks delivering a system—sometimes decades later—that is already obsolete. In contrast, leading companies use iterative cycles to design, validate, and deliver complex products with speed. Activities in these iterative cycles often overlap as the design undergoes continuous user engagement and testing, which allows the product to get to market quickly.

DOD has made efforts to address problematic aspects of the defense acquisition system, particularly for furthering innovation. For example, it established the Defense Innovation Unit to further commercial technology adoption and provides various financial flexibilities. However, these remain largely workarounds to address problems that result from the current acquisition system, rather than enduring solutions that fix the underlying system itself.

GAO’s recent and ongoing body of work on practices used by leading companies could provide a blueprint for reform.

Why GAO Did This Study

Despite recent reforms, DOD remains plagued by escalating costs, prolonged development cycles, and structural inefficiencies that impede its ability to acquire and deploy innovative technologies with speed. The 2022 National Security Strategy and the 2022 National Defense Strategy make clear that the acquisition processes that DOD has used in the past are too slow to address emerging threats of the future. An April 2025 executive order states that a comprehensive overhaul of DOD’s acquisition system is needed to deliver state-of-the-art capabilities at speed and scale.

This testimony addresses (1) DOD’s ongoing challenges to delivering weapon systems within cost, schedule, and performance parameters, and (2) how leading practices for product development can inform changes to the defense acquisition system. This statement draws largely from GAO’s 2025 annual assessment of DOD’s major weapon systems (GAO-25-107569) and GAO’s leading practices for product development (GAO-23-106222). It also leverages GAO’s extensive body of work on DOD weapon systems acquisitions and recent reports on individual weapon systems and innovation and flexibilities in DOD procurement efforts.

What GAO Recommends

GAO has made numerous recommendations to DOD in these areas, including that newer future major weapon acquisition programs include leading practices for product development during early program stages, and that DOD updates acquisition policies to incorporate certain of these practices. DOD has generally concurred with these recommendations but has not fully implemented them.

Chairman Timmons, Ranking Member Subramanyam, and Members of the Subcommittee:

Thank you for the opportunity to discuss the Department of Defense’s (DOD) procurement and innovation challenges. The acquisition system has reached a critical juncture. The sophistication of new technologies—like biotechnology and microelectronics—and the rise of artificial intelligence and machine learning models have enabled our adversaries to seize upon rapid innovation and development to be used for military gain. In recent years, multiple administrations and Congresses have recognized and tried to solve deficiencies in the defense acquisition system. The 2022 National Security Strategy and the unclassified 2022 National Defense Strategy make clear that the acquisition processes used to deliver capabilities in the past are too slow to address the emerging threats of the future. An April 2025 executive order goes further, stating that a comprehensive overhaul of the acquisition system is needed to deliver state-of-the-art capabilities at speed and scale.[1]

While DOD has made efforts to identify efficiencies, these address symptoms, rather than provide enduring solutions. DOD remains plagued by escalating costs, prolonged development cycles, and structural inefficiencies that impede its ability to procure and deploy innovative technologies with speed. Today we released our 23rd annual assessment of weapon programs.[2] In that report, we found that DOD plans to invest nearly $2.4 trillion to develop and acquire 106 of its costliest weapon programs. Yet, the expected time frame for major defense acquisition programs to provide even an initial capability is now almost 12 years from the program’s start—a time frame incompatible with emerging threats and the rate of technological change.

A critical issue is that DOD remains deeply entrenched in a traditional linear acquisition structure—characterized by rigid, sequential processes—that has proven inadequate in adapting to evolving threats and integrating emerging innovations. In a linear acquisition, cost, schedule, and performance baselines are fixed early, prior to design and development and before critical technologies are tested for performance and usability. Further, this approach compels programs to develop systems to meet fixed requirements set years before delivery. This risks delivering a system—sometimes decades later—that is already obsolete.

Simply put, more radical change is needed. Over the last 5 years, we interviewed leading global companies to identify the practices that drive success in delivering complex products. We found that these companies employ a new approach that—if fully implemented by DOD—can enable DOD to deliver complex systems with speed using new, iterative approaches for development.

My statement today will address (1) DOD’s ongoing challenges to delivering weapon systems within cost, schedule, and performance parameters and recent reform efforts; and (2) how leading practices for product development can inform changes to the defense acquisition system.

This testimony draws from our extensive body of work on DOD’s acquisition of weapon systems and the numerous recommendations we have made regarding individual weapon programs and systemic improvements to the acquisition process. It also leverages our recent reports on leading practices in product development, and innovation and flexibilities in DOD procurement efforts. For the reports cited in this statement, among other methodologies, we analyzed DOD guidance, data, and documentation; performed site visits; analyzed cost and schedule data from a variety of sources; and interviewed officials from DOD and the military services. We also identified leading innovative product development companies based on rankings in well-recognized lists and awards, records of financial stability and success, and industry type. We then analyzed available company documentation and interviewed product development representatives with each of those companies. These activities supported our efforts to identify leading practices in product development. Our reports cited in this statement, which were published from June 2017 through June 2025, provide further detailed information on their objectives, scopes, and methodologies.

We conducted the work on which this statement is based in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Despite Reforms, DOD Struggles to Deliver Innovative Technologies

DOD Has Long Struggled to Deliver Weapon Systems at Cost and with Speed

DOD’s challenges with developing, acquiring, and fielding weapon systems are far from a recent phenomenon. In 1990, we put DOD weapon systems on our list of programs at high risk of fraud, waste, abuse, and mismanagement, where it remains today.[3]

For over 20 years, we have annually reported on challenges with DOD’s most expensive weapon system acquisition programs. These programs have demonstrated consistent outcomes: weapon systems that have historically had no rival in superiority, but that are routinely over budget, late to need, and underperform their intended mission. For example, we reported today that in the past year, combined total cost estimates increased by $49.3 billion—or 8.3 percent—for the 30 major defense acquisition programs (MDAP) that we had also assessed in our 2024 report.[4] This increase was driven primarily by the Air Force’s LGM-35A Sentinel missile program, which reported a cost increase of over $36 billion following a breach of a statutory critical unit cost growth threshold in January 2024. We have ongoing work assessing the Air Force’s efforts to restructure the program.

We also reported that the average time for MDAPs to provide the warfighter with an initial capability is now almost 12 years from the program’s start. This average time frame increased despite the inclusion of MDAPs that began on the middle tier of acquisition (MTA) pathway—an acquisition approach intended to facilitate speed.[5] Six programs experienced delays of approximately 12 months or more. Among the reasons for these delays were ongoing design issues, technical challenges, and testing delays. In one example, the Air Force’s B-52 Radar Modernization Program reported an additional 34-month schedule delay due to challenges related to testing, parts procurement, and software, among other things. This delay, along with the others, puts warfighters at risk of receiving weapon systems that no longer meet their needs because the needed capabilities have evolved.

Our annual assessments often build on the in-depth assessments that we perform on selected programs. Collectively, these assessments form the foundation for an extensive body of work documenting DOD’s struggle to deliver timely weapon systems to the warfighter. Some of our recent work includes the following:

· In May 2023, we reported that the Air Force’s Advanced Pilot Trainer (APT) was nearly 10 years behind schedule, increasing reliance on aging T-38 trainer aircraft. APT program delays will likely cost the Air Force nearly $1 billion due to the need to use more expensive fighter jets to train pilots and fund unplanned upgrades to existing trainer aircraft.[6] Today, we reported that the program further delayed its initial operational capability date by nearly 1 year, to January 2028, as a result of not having the required number of operational jets.[7]

· In September 2024, we reported that significant work and challenges remain in the Air Force’s effort to modernize the Global Positioning System (GPS) satellite constellation. Although the Air Force launched the first GPS satellite capable of broadcasting a jam-resistant signal in 2005, continued delays to the ground and user equipment segments prevent widespread use of the technology. The military departments must integrate the user equipment with ground, air, and maritime weapon systems before delivering this capability to the warfighter.[8] Today, we reported that launch and operation of upgraded and modernized GPS satellites depends on the delivery of the next generation ground control station, which is replanning its schedule due to testing-related delays.[9]

· We reported in September 2024 that it would be difficult for the Columbia class submarine program to correct poor schedule and cost performance amid construction risks and inadequate analysis. We noted that the program was experiencing persistent design and construction challenges that contributed to schedule delays and cost growth. Further, our independent analysis calculated likely cost overruns that were more than six times higher than the contractor’s estimates and almost five times more than the Navy’s.[10] Today, we reported that the Navy declared a schedule breach for the lead submarine and is developing plans to meet a delivery date of October 2028—a 12-month delay from the program’s contract delivery date. However, the delivery date could be delayed by as much as 18 months if planned improvements do not materialize. Further, we reported that after a year of construction, the follow-on submarine is about 12 percent behind schedule and will need to significantly accelerate construction to meet planned delivery dates.[11]

DOD Is Not Structuring Programs to Deliver Innovative Technologies with Speed

The poor outcomes identified above are occurring despite DOD having made considerable efforts over the past 5 years to reform its policies governing how it acquires new capabilities. The overarching goal of such reforms has been to deliver innovative capabilities to the warfighter more quickly. Specifically, in January 2020, DOD established the Adaptive Acquisition Framework (AAF), which emphasized several principles that include simplifying acquisition policy, tailoring acquisition approaches, and conducting data-driven analysis.[12]

The AAF provides six acquisition pathways. Four of the pathways are directly related to weapon systems:[13]

· Urgent Capability Acquisition is a pathway intended to fulfill an urgent existing or emerging operational need in less than 2 years.[14]

· Major Capability Acquisition is designed to support certain complex acquisitions, such as major defense acquisition programs. Acquisition and product support processes, reviews, and documentation can be tailored based on the program size, complexity, risk, urgency, and other factors.[15]

· Middle Tier of Acquisition (MTA) was established to fill a gap in the defense acquisition system for capabilities that are either (1) mature enough to be rapidly prototyped within an acquisition program, or (2) fielded within 5 years of MTA program start. The pathway may be used to accelerate capability maturation before transitioning to another acquisition pathway or to minimally develop a capability before rapid fielding.[16] Additionally, the MTA pathway offers certain flexibilities to the acquisition process that help deliver suitable capabilities more quickly and enable DOD to be more responsive to the warfighter’s needs.

· Software Acquisition is a pathway that establishes a framework for software acquisition and development investment decisions that addresses trade-offs between capabilities, affordability, risk tolerance, and other considerations.[17]

Through the option to use the different acquisition pathways, either singularly or in combination, the AAF is intended to allow program managers to best match the characteristics and risk profile of the capability being acquired, as well as tailor and streamline certain processes. For example, programs on the MTA pathway are not subject to the traditional requirements process and have tiered thresholds for data reporting.

Although the AAF reforms offer additional flexibilities, DOD has yet to show it has achieved better acquisition outcomes. Many programs, including some on the MTA pathway, continue to use a slow and linear development approach, falling short of delivering capabilities quickly and at scale. For example, there are programs starting on the MTA pathway that plan to spend 5 years for rapid prototyping followed by 5 years or more for further development efforts. In addition, most MTA programs’ acquisition strategies did not outline how the programs plan to leverage leading practices to develop and deliver initial fieldable capability in the form of a minimum viable product—the goal of an iterative approach—within 5 years.[18]

We believe that continuing down this path will not result in DOD achieving its goal of delivering innovative capabilities to the warfighter in a more timely manner.

DOD Has Yet to Implement Leading Practices to Enable Speedy Delivery of Complex, Innovative Products

Leading Companies Use Iterative Cycles to Deliver Complex, Innovative Products

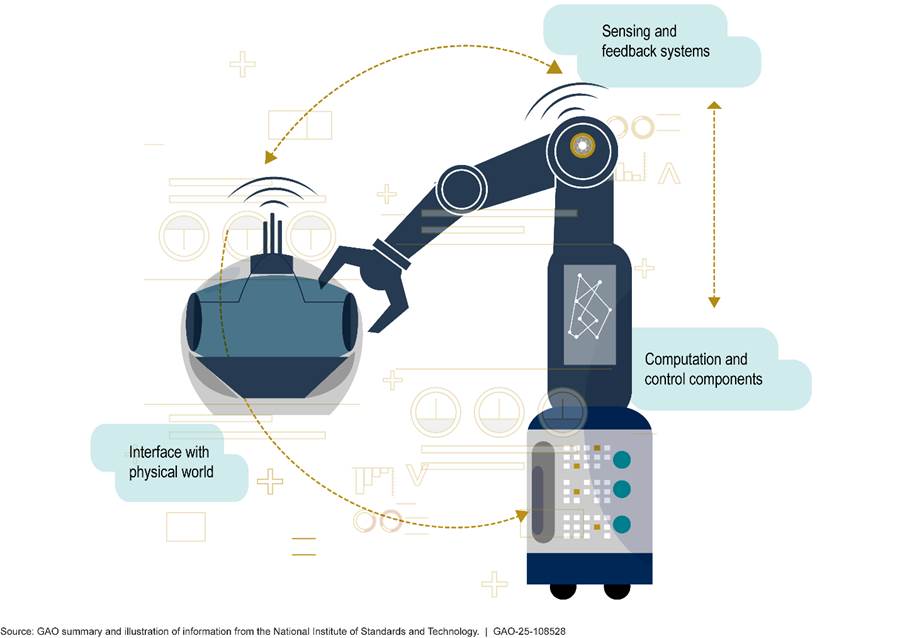

Over the past several years, we have been updating our body of work on leading practices to incorporate new approaches that leading companies have been using to quickly deliver complex, innovative products to the market. Our prior work has also shown how leading companies use technology development to enable an iterative approach to development. Leaps in technology have changed the nature of the capabilities that the private sector—and DOD—seek to acquire. Rather than seeking to fulfill its most dynamic mission needs by acquiring mechanical, hardware-based systems, DOD is increasingly investing in cyber-physical systems—co-engineered networks of hardware and software, such as aircraft and uncrewed vehicles—to solve those needs. Within a cyber-physical system, software does not simply process data; it also interacts with the physical world. The software receives information about the environment through sensors, such as temperature, tire pressure, camera, or radar sensor data. The software then uses these data to instruct physical hardware, such as motors, pumps, or valves. The system’s functionality is controlled by software algorithms. These cyber-physical systems are also designed to allow for downloading software updates that add or enhance existing capabilities and help keep systems relevant. Figure 1 illustrates a cyber-physical system process for integrating information.

Figure 1: Cyber-Physical Systems Integrate Continuous Physical and Digital Information

The growth of cyber-physical systems in product development has led to new iterative development approaches in industry. These approaches involve incorporating the same iterative, Agile practices for software development into hardware development. In doing so, companies can deliver innovative, complex systems with speed, especially when using modern design and manufacturing tools and processes to produce and deliver a product in time to meet customer needs. Table 1 describes some of the differences between traditional, linear development and modern, iterative development.

Table 1: Comparison of Linear Development and Iterative Development

|

|

Linear development |

Iterative development |

|

Requirements |

Requirements are fully defined and fixed up front. |

Requirements evolve and are defined in concert with demonstrated achievement. |

|

Development |

Development is focused on compliance with original requirements. |

Development is focused on user needs and mission effect. |

|

Performance |

Performance is measured against an acquisition cost, schedule, and performance baseline. |

Performance is measured through multiple value assessments—a determination of whether the outcomes are worth continued investment. |

Source: GAO analysis. I GAO‑25‑108528

Iterative development involves a series of interconnected activities that are continuously updated and inform the companies’ decisions as to what they can deliver to meet their customers’ needs within cost, schedule, quality, and performance targets. For example, in June 2017, we reported that leading companies rapidly develop and demonstrate a series of iterations of a new technology. Only once the new technology is proven to work is it considered for integration into a product for the company to sell.[19]

Our subsequent reports have elaborated on this basic concept. For example, in March 2022, we identified four key principles that help characterize how products move through iterative development cycles:

· Attain a sound business case that is informed by research along with collaboration with customers;

· Use an iterative design approach that results in minimum viable products;

· Prioritize schedule by off-ramping capabilities when necessary; and

· Collect user feedback to inform improvements to the minimum viable product.[20]

In July 2023, we reported on how leading companies structure development to use new technologies in future new products.[21] For example, the initial business case evolves over the course of product development. The business case connects to research and development and technology management, so that research and development efforts focus on providing key technologies to be used in future new products. Thus, research and development for a specific product does not end with the first iteration of the product. Rather, it continues so that future iterations will reliably have new, innovative, and mature technologies available and remain useful for much longer.

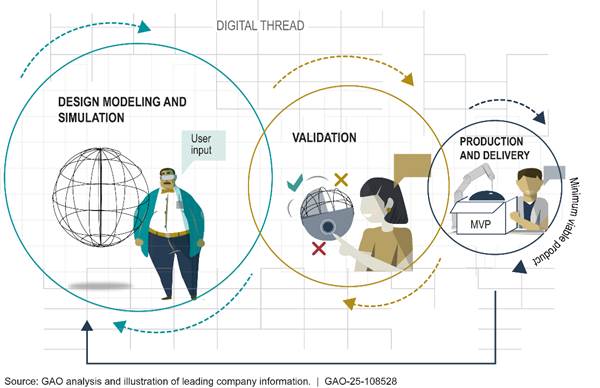

We also reported that the iterative process that companies employ involves continuous cycles to rapidly develop and deploy products.[22] Throughout are key practices common to these iterative cycles. For example:

· Leading companies seek and obtain continuous user feedback—feedback from the actual operators of the product—throughout the iterative cycles.

· Leading companies capture this feedback to determine if the design is meeting user needs and reflects a minimum viable product—a product with the minimum capabilities needed for customers to recognize value.

· Leading companies continually feed this product design information into a real-time digital thread—a common source of information connecting stakeholders with real-time data across the product life cycle to inform product decisions.

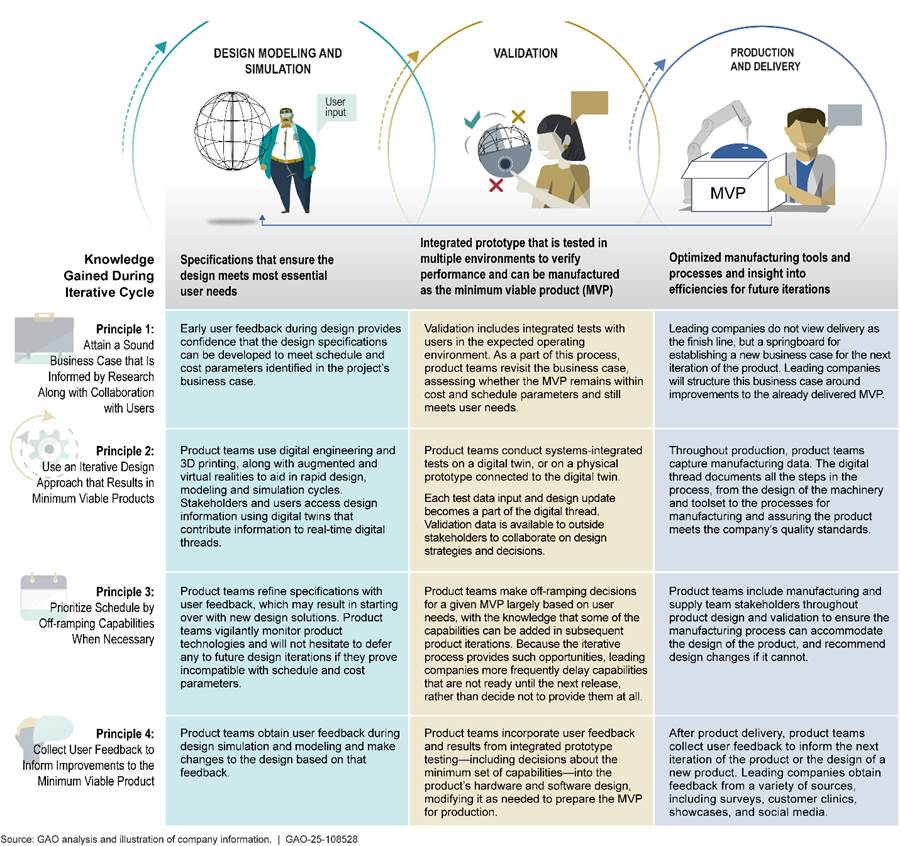

Figure 2 illustrates the structure for iterative development cycles.[23]

Figure 2: Leading Companies Progress Through Iterative Design, Validation, and Production Cycles to Develop a Minimum Viable Product

DOD Has Yet to Implement Leading Practices

We have made multiple recommendations to DOD to incorporate leading practices that would improve outcomes, but DOD has yet to implement many of these recommendations. For example:

· In June 2017, we recommended that to ensure DOD was positioned to counter both near- and far-term threats, the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering (USD(R&E)) should annually (1) define the mix of incremental and disruptive innovation investments for each military department, and (2) assess whether that mix is achieved. Further, we recommended that to ensure DOD is positioned in line with leading practices for managing science and technology programs, USD(R&E) should define, in policy or guidance, a science and technology management framework that included emphasizing existing flexibilities to more quickly initiate and discontinue projects to respond to the rapid pace of innovation.[24] We identified these recommendations as priority recommendations for DOD given their importance to ensuring that DOD has the technologies available to meet the needs of the warfighter both now and into the future.[25]

In July 2024, DOD reported that, although it did not agree with our recommendation to specify the percentage of the military departments’ incremental and disruptive technology development investments, it intends to rely on the results of a planned independent study to inform a reasonable range of investments in each of the three science and technology-related budget activities. Further, DOD intends to use the results of this study to provide recommendations on policy and guidance for using existing flexibilities. DOD expects this study to be completed by July 31, 2025.

· In March 2022, we recommended that the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment (USD(A&S)) update DOD acquisition policies to fully implement the four key product development principles throughout development.

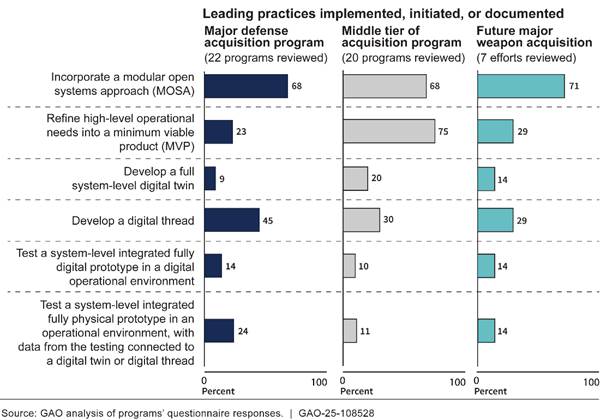

DOD concurred with our recommendations and, in August 2022, USD(A&S) noted it would consider the further application of key product development principles when it formally updates its overarching acquisition policy and the other individual acquisition pathways and functional acquisition policies.[26] However, in our Annual Weapon Systems Assessment that we issued today, we reported that most programs do not fully implement leading practices to achieve efficiencies—including newer programs that have more opportunities to do so. For example, most programs reported using a modular open systems approach—generally required by statute—that allows them to easily add or replace weapon parts over time. Few, however, reported plans to establish a minimum viable product (an initial set of capabilities that can be iterated upon), use digital twinning (a virtual representation of a physical product), or use digital threads (real-time data to inform decision-making).

We reported that there are opportunities for future major weapon acquisitions that have yet to start on an adaptive acquisition pathway to leverage leading practices during the earliest stages of the program—before they become locked into rigid requirements, budgets, and development approaches.[27] However, these future programs reported that they intended to incorporate leading practices generally at levels at or below the levels reported by current MDAPs or MTAs (see fig. 3).

Figure 3: Most Programs GAO Reviewed Do Not Fully Implement Leading Practices, Including Future Efforts That Are Newer and Have Opportunities to Do So

· In June 2024, we recommended that the Secretary of Defense direct USD(A&S) to issue a policy calling for MTA program acquisition strategies to include how the program plans to implement leading practices for product development to deliver fieldable capability with speed, within 5 years.[28]

DOD stated, in response to our recommendation, that it was prepared to issue guidance requiring MTA programs to comply with this recommendation. However, in February 2025, we reported that DOD had yet to update its acquisition policies to fully incorporate leading practices.[29]

The revised MTA policy that DOD issued in November 2024 did not fully implement leading practices to achieve positive outcomes and DOD has yet to revise its major capability of acquisition policy.

· In December 2024, we found that while military department policies for the software acquisition pathway included an iterative development structure intended to facilitate speed and innovation, neither the military departments’ policies nor guidance for the other pathways included this structure. Further, officials for several acquisition programs that we spoke with did not consistently demonstrate a clear understanding of how to implement iterative development in their efforts. We reported that this lack of understanding may result in officials missing opportunities to deliver capabilities with speed and innovation. We recommended that each of the services revise its acquisition policies and relevant guidance to reflect leading practices that facilitate speed and innovation, among other elements. DOD concurred with some of the recommendations and partially concurred with others.[30]

GAO Has Ongoing Work Examining How DOD Might Implement Additional Changes

While our past work has laid the foundation for better outcomes, we are continuing to assess other aspects of leading commercial practices that DOD can implement to achieve better outcomes with its weapon system acquisition programs. Specifically, our work addresses:

· How leading commercial companies employ portfolio management approaches and develop business cases to guide their product development investments. The iterative development approach discussed above has implications for how government agencies may need to shift their approaches to portfolio management and associated investment decisions. We expect to issue a report later this summer.

· How, and to what extent, USD(R&E) is implementing authorities granted to it in statute and in policy to promote innovation within DOD to enable weapon system acquisition programs to take an iterative approach to development. As stated earlier, an iterative approach to development requires that new, innovative, and mature technologies are available. We expect to issue a report this fall.

· How DOD can leverage leading practices to refocus its oversight efforts from a program-centric approach toward a more flexible and agile approach of managing portfolios of capability development efforts that meet high-level capability needs. Fully implementing iterative development leading practices within individual acquisition programs will require changes to related processes that govern capability development at DOD. In particular, this includes DOD’s processes for defining requirements and managing the portfolios of capability development efforts. These processes are currently structured to support DOD’s traditional, linear development process and, as such, do not effectively enable iterative development practices within acquisition programs. We expect to report on this work in early 2026.

DOD Has Made Isolated Efforts to Increase Innovation and Flexibility

Beyond the new acquisition pathways instituted in the AAF, DOD has made efforts to address problematic aspects of the defense acquisition system, particularly to further innovation. However, these remain largely isolated efforts to address specific problems resulting from the current acquisition system, rather than fixing the underlying system itself. For example:

· Defense Innovation Unit. As we reported in February 2025, the Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) is refocusing its efforts to transition commercial technology to military use at speed and scale.[31] DOD established DIU in 2015 to improve the adoption of commercial technologies, recognizing that companies producing the most cutting-edge technologies were often in the commercial sphere. DIU also recognized that companies used to commercial practices faced challenges dealing with the existing defense acquisition system. DIU addressed these challenges by using a faster-paced award process that allowed DOD and the services to prototype, test, and potentially transition commercial solutions within roughly 24 months. Through fiscal year 2023, DIU reported that it successfully transitioned 62 of the prototype agreements it awarded to production awards or contracts. This represents about half of the DIU projects that had completed at least one prototype agreement.

In 2023, DIU announced plans to increasingly focus on transitioning capabilities that will have the greatest effect on DOD’s most strategic challenges. To do this, DIU plans to work more closely with the military services and combatant commands—including embedding staff in these organizations—to better understand their requirements and needs and be better-positioned to scale the technologies they need. DIU also established the Defense Innovation Community of Entities—a group composed of innovation organizations from across DOD and the military services—to better coordinate innovation activities. This group aims, in part, to reduce siloes that limit insight into organizations’ priority capability needs.

· Financial flexibilities. In June 2023, we reported on DOD’s use of financial flexibilities available for research and development and other innovation and modernization activities.[32] These flexibilities result from at least 26 different authorities related to budgeting and financial management available during fiscal years 2017 to 2021. The need for financial flexibilities stems from concerns that DOD’s established Planning, Programming, Budgeting and Execution (PPBE) process is not fast or flexible enough to respond to current and emerging threats. We found that DOD used selected flexibilities, and noted their benefits, particularly to address needs or requirements that arose from outside of the PPBE process.

We also previously reported that the lengthy PPBE process can slow innovation.[33] Additionally, we reported that executive and legislative branch leaders have repeatedly identified lengthy delays—such as delayed budget appropriations and continuing resolutions—pose a threat to national security.

· Other transaction agreements (OTA). Congress gave DOD the authority to use OTAs—a mechanism that allows for more flexibility than traditional procurement contracts subject to the Federal Acquisition Regulation—under certain conditions, including prototyping new technologies.[34] Among other benefits, the flexibilities of OTAs can help DOD to more easily work with contractors that have not previously worked with DOD by streamlining requirements that apply to traditional procurement contracts. We previously found that such nontraditional defense contractors cited the complexity and cost of complying with government-unique terms and conditions as one of multiple barriers to working with the government.[35] In September 2022, we reported that DOD obligated over $24 billion on OTA awards for prototyping efforts from fiscal years 2019 through 2021.[36] Further, in March 2025, the Secretary of Defense directed DOD components to use OTAs as a default award approach to acquire qualifying capabilities under the AAF’s Software Acquisition Pathway.[37] We are currently conducting work regarding DOD’s use of OTAs.

While DOD has recognized the need to address problems that may stymie innovation, the individual actions it has taken in response do not correct the problems that exist in the overarching structure of the defense acquisition system—problems that prevent weapon acquisition programs from maximizing innovation through iterative capability deliveries. DOD’s disparate improvement efforts can relieve some of the symptoms associated with working through the current structure, but they remain workarounds rather than enduring solutions.

An April 2025 executive order calls for a comprehensive overhaul of the defense acquisition system.[38] In response, the Secretary of Defense and military components are directed to formulate plans to reform acquisition processes and assess major programs. Similarly, another April 2025 executive order directs agencies to streamline the federal acquisition regulations that govern federal procurement.[39] As DOD develops these plans, our leading practices for product development could provide a blueprint for making wholesale change.

In conclusion, DOD cannot afford to rely on changes at the margin. The threat environment requires a wholesale shift to the defense acquisition system—one that considers the need for iterative solutions to keep pace with evolving warfighter needs. DOD weapon systems are increasingly complex cyber-physical systems that require new, iterative development approaches to achieve speed in delivery. Achieving the positive outcomes associated with leading practices requires an overarching acquisition system that enables programs to plan for iterative approaches from their inception. This can include refining a minimum viable product based on continuous user feedback, adopting modern digital engineering tools that facilitate rapid iterations of design, development, and delivery, and inserting new disruptive technologies through an innovation pipeline. Moving forward, our many open recommendations and our ongoing work on leading commercial practices and DOD approaches should provide a strategic foundation for the substantive reforms necessary to address these needs.

Chairman Timmons, Ranking Member Subramanyam, and Members of the Subcommittee, this completes my prepared statement. I would be pleased to respond to any questions that you may have at this time.

GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments

If you or your staff have any questions about this testimony, please contact Shelby S. Oakley, Director, at OakleyS@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this statement. GAO staff who made key contributions to this testimony are Erin Carson (Assistant Director), Jennifer Dougherty (Analyst-in-Charge), Matthew T. Crosby, Laura Greifner, James Holley, and Brian Smith .

Appendix I: Iterative Cycles of Design, Validation, and Production Used for Product Development

Figure 4: Iterative Cycles of Design, Validation, and Production Used for Product Development

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]Exec. Order No. 14,265, 90 Fed. Reg. 15,621 (Apr. 9, 2025).

[2]GAO, Weapon Systems Annual Assessment: DOD Leaders Should Ensure that Newer Programs Are Structured for Speed and Innovation, GAO‑25‑107569 (Washington, D.C.: June 11, 2025).

[3]GAO, High-Risk Series: Heightened Attention Could Save Billions More and Improve Government Efficiency and Effectiveness, GAO‑25‑107743 (Washington, D.C.: Feb 25, 2025).

[4]GAO‑25‑107569. Major defense acquisition programs generally include those programs that are not a highly sensitive classified program and that are either (1) designated by the Secretary of Defense as a major defense acquisition program; or that are (2) estimated to require an eventual total expenditure for research, development, test, and evaluation, including all planned increments or spirals, of more than $525 million in fiscal year 2020 constant dollars or, for procurement, including all planned increments or spirals, of more than $3.065 billion in fiscal year 2020 constant dollars. See 10 U.S.C. § 4201(a); DOD Instruction 5000.85, Major Capability Acquisition (Aug. 6, 2020) (incorporating change 1 Nov. 4, 2021) (reflecting statutory major defense acquisition program cost thresholds in fiscal year 2020 constant dollars). Certain programs that meet these thresholds, including programs using the middle tier of acquisition (MTA) pathway, are not considered major defense acquisition programs. See 10 U.S.C. § 4201(b).

[5]Department of Defense Instruction 5000.80.

[6]GAO, Advanced Pilot Trainer: Program Success Hinges on Better Managing Its Schedule and Providing Oversight, GAO‑23‑106205 (Washington, D.C.: May 18, 2023).

[8]GAO, GPS Modernization: Delays Continue in Delivering More Secure Capability for the Warfighter, GAO‑24‑106841 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 9, 2024).

[10]GAO, Columbia Class Submarine: Overcoming Persistent Challenges Requires Yet Undemonstrated Performance and Better-Informed Supplier Investments, GAO‑24‑107732 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 30, 2024).

[12]Department of Defense, Instruction 5000.02, Operation of the Adaptive Acquisition Framework (Jan. 23, 2020) (incorporating change 1, June 8, 2022).

[13]The two additional AAF pathways not directly related to acquisition are Defense Business Systems and Defense Acquisition of Services.

[14]Department of Defense Instruction 5000.81, Urgent Capability Acquisition (Dec. 31, 2019).

[15]Department of Defense Instruction 5000.85, Major Capability Acquisition (Aug. 6, 2020) (incorporating change 1, Nov. 4, 2021).

[16]DOD Instruction 5000.80. The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2016 required DOD to establish guidance for an alternative acquisition process, now referred to as MTA, for programs intended to be completed in a period of 2 to 5 years. See Pub. L. No. 114-92, § 804 (2015). In December 2024, Congress passed legislation that codified the MTA pathway and added new provisions affecting the pathway, including requirements related to iterative prototyping and fielding. 10 U.S.C. § 3602.

[17]Department of Defense Instruction 5000.87, Operation of the Software Acquisition Pathway (Oct. 2, 2020).

[18]GAO, Weapon Systems Annual Assessment: DOD Is Not Yet Well-Positioned to Field Systems with Speed, GAO‑24‑106831 (Washington, D.C.: June 17, 2024).

[19]GAO, Defense Science and Technology: Adopting Best Practices Can Improve Innovation Investments and Management, GAO‑17‑499 (Washington, D.C.: June 29, 2017).

[20]GAO, Leading Practices: Agency Acquisition Policies Could Better Implement Key Product Development Principles, GAO‑22‑104513 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 10, 2022).

[21]GAO, Leading Practices: Iterative Cycles Enable Rapid Delivery of Complex, Innovative Products, GAO‑23‑106222 (Washington, D.C.: July 27, 2023).

[23]See appendix I for a more detailed illustration of the structure of iterative development cycles and how product developers implement the four principles within that structure.

[25]GAO, Priority Open Recommendations: Department of Defense, GAO‑24‑107327 (Washington, D.C.: June 28, 2024).

[30]GAO, DOD Acquisition Reform: Military Departments Should Take Steps to Facilitate Speed and Innovation, GAO‑25‑107003 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 12, 2024).

[31]GAO, Defense Innovation Unit: Actions Needed to Assess Progress and Further Enhance Collaboration, GAO‑25‑106856 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 27, 2025).

[32]GAO, Research and Development: DOD Benefited from Financial Flexibilities but Could Do More to Maximize Their Use, GAO‑23‑105822 (Washington D.C.: June 29, 2023).

[34]See 10 U.S.C. §§ 4021-4022.

[35]GAO, Military Acquisitions: DOD Is Taking Steps to Address Challenges Faced by Certain Companies, GAO‑17‑644 (Washington, D.C.: July 20, 2017).

[36]GAO, Other Transaction Agreements: DOD Can Improve Planning for Consortia Awards, GAO‑22‑105357 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 20, 2022).

[37]Secretary of Defense Memorandum, Directing Modern Software Acquisition to Maximize Lethality (Mar. 6, 2025).

[38]Exec. Order No. 14,265, 90 Fed. Reg. 16,445 (Apr. 15, 2025).

[39]Exec. Order No. 14,275, 90 Fed. Reg. 16,445 (Apr. 18, 2025).