VETERANS AFFAIRS

Leading Practices Can Help Achieve IT Reform Goals

Statement of Carol Harris, Director, Information Technology and Cybersecurity

Before the Subcommittee on Technology Modernization, Committee on Veterans’ Affairs, House of Representatives

For Release on Delivery Expected at 3:00 p.m. ET

United States Government Accountability Office

A testimony before the Subcommittee on Technology Modernization, Committee on Veterans’ Affairs, House of Representatives

For more information, contact: Carol Harris at HarrisCC@gao.gov

What GAO Found

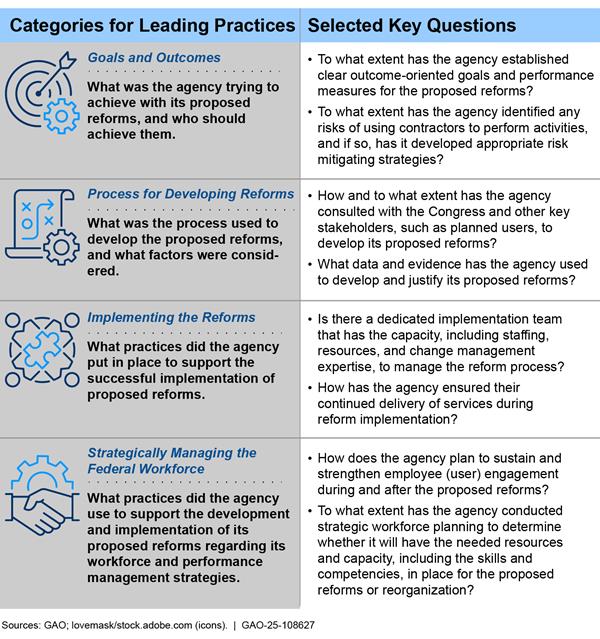

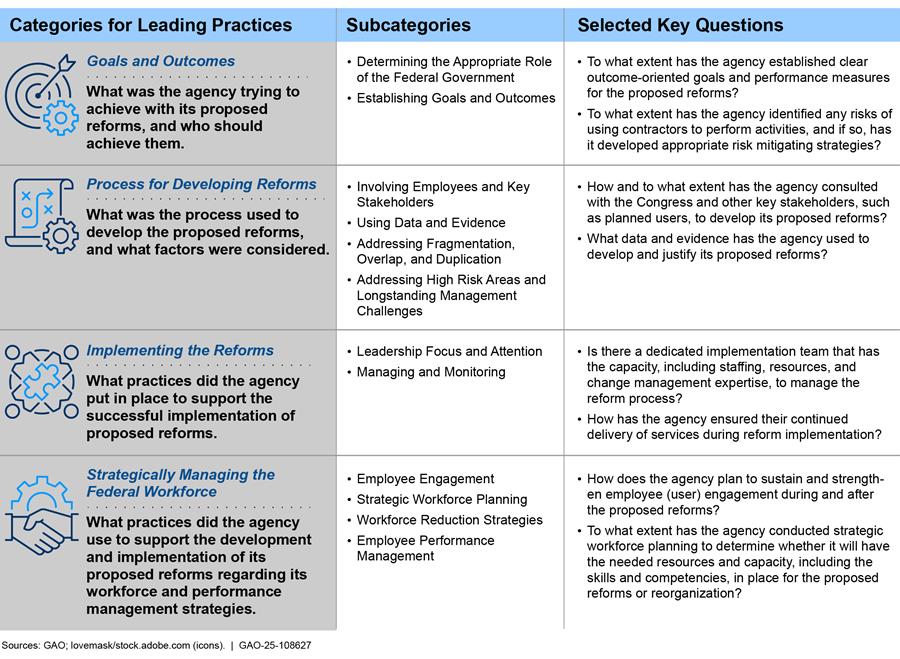

VA’s fiscal year 2026 budget reflects a range of planned reforms: investing over $3.5 billion to hasten implementation of electronic health record modernization, reducing IT expenditures by about $500 million to retire outdated legacy systems and reassess IT initiatives, and streamlining administrative practices leading to about $40 million in savings. GAO has identified leading practices and selected questions that can assist in achieving IT reform goals.

Figure: Leading Practices and Selected Key Questions for Agency Reform Efforts

Why GAO Did This Study

VA depends on critical IT systems to manage benefits and provide care to millions of veterans and their families. The department’s investment in IT is substantial—VA plans to spend about $7.3 billion in fiscal year 2026.

VA operates a centralized organization, the Office of Information Technology, to plan and execute most IT management functions. This office is responsible for providing direction and guidance on IT acquisition and management.

However, VA has a long history of failed IT modernization efforts. For example, after three failed attempts between 2001 and 2018, VA began implementing its fourth effort in 2020 to modernize its legacy health information system. However, in 2023 it halted further system deployments due to widespread concerns. In December 2024, VA announced plans for additional deployments restarting in 2026. VA has experienced similar weaknesses in acquiring major IT systems, managing its IT workforce, tracking software licenses, and standardizing cloud computing procurement.

GAO’s statement (1) identifies key reform elements of VA’s fiscal year 2026 IT budget request, and (2) describes leading practices and selected questions for assessing agency reforms.

What GAO Recommends

The prior GAO IT reports described in this statement include 26 recommendations to VA that are not yet implemented.

Chairman Barrett, Ranking Member Budzinski, and Members of the Subcommittee:

Thank you for the opportunity to discuss the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) as you examine how the department is positioned to deliver IT services essential to supporting its mission to care for our nation’s veterans. As you know, VA depends on critical underlying IT systems to manage benefits and to provide care to millions of veterans and their families. The department operates and maintains an IT infrastructure that is intended to provide the backbone necessary to meet the day-to-day operational needs of its medical centers, veteran-facing systems, benefits delivery systems, memorial services, and all other systems supporting the department’s mission. It is also responsible for protecting veteran data against cybersecurity threats.

We and VA’s Office of Inspector General (OIG) have reported on VA’s challenges with managing its major IT acquisitions, including its financial management systems and electronic health record modernization initiatives, which have experienced schedule delays.[1] In 2015, we added Managing Risks and Improving VA Health Care to our High-Risk List because of system-wide challenges, including major modernization initiatives.[2] We also added VA Acquisition Management to our High-Risk List in 2019 due to, among other things, challenges with managing its acquisition workforce and inadequate strategies and policies. Both remain high-risk areas.[3]

For this testimony statement, I will describe (1) key reform elements of VA’s fiscal year 2026 IT budget request, and (2) leading practices and selected questions for assessing agency reforms.

In developing this testimony, we summarized examples of previously reported GAO work on VA’s management of IT resources. We also examined VA’s FY2026 budget request to describe proposed actions related to IT resources and initiatives. We identified a collective set of practices and key questions relevant to agencies’ reform.[4] We focused on questions for each category of leading practices that had the most relevance to the management of IT resources. The reports cited throughout this statement include detailed information on their scopes and methodologies.

We conducted the work on which this statement is based in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Effectively managing IT needs depends on federal departments and agencies, including VA, having key functions in place. Toward this end, we have previously identified key IT-related functions that serve as a sound foundation for IT management including, for example: leadership, strategic planning, systems development and acquisition, systems operations and maintenance, and cybersecurity.[5]

Over the last three decades, Congress has enacted several laws to help federal agencies improve the management of IT investments and to assign responsibilities to agency leadership.

· The Clinger-Cohen Act of 1996 requires agency heads to appoint chief information officers (CIO) and specifies many of their responsibilities with regard to IT management.[6] Among other things, CIOs are responsible for implementing and enforcing applicable government-wide and agency IT management principles, standards, and guidelines and assuming responsibility and accountability for IT investments. In addition, CIOs of covered agencies such as VA are also responsible for monitoring the performance of IT programs and advising the agency head whether to continue, modify, or terminate such programs.[7]

· In December 2014, Congress enacted IT acquisition reform legislation, commonly referred to as the Federal Information Technology Acquisition Reform Act or FITARA.[8] FITARA was intended to enable Congress to monitor covered agencies’ increased efficiency and effectiveness of IT investments, as well as holding agencies accountable for reducing duplication and achieving cost savings. FITARA, among other things, required VA and other covered executive branch agencies to improve their IT acquisitions by requiring CIO involvement in these acquisition processes.[9] One way that the law enhances the authority of covered agency CIOs is by requiring them to review and approve contracts for IT.

In addition to IT laws, federal guidance acknowledges that a resilient, skilled, and dedicated cybersecurity workforce is essential to protecting federal IT systems as well as enabling the government’s day-to-day functions. Building and maintaining the cybersecurity workforce is one of the federal government’s most important challenges as well as a national security priority.[10]

VA’s Office of Information Technology Performs Key IT Functions

Since 2007, VA has been operating a centralized organization, the Office of Information and Technology (OIT), in which most key IT management functions are performed. This office is led by the Assistant Secretary for Information and Technology, also known as VA’s CIO. OIT is responsible for providing strategy and technical direction, guidance, and policy related to how IT resources will be acquired and managed for the department.

OIT is also responsible for working with its business partners—such as the Veterans Health Administration—to identify and prioritize business needs and requirements for IT systems. Further, OIT has responsibility for managing the majority of VA’s IT-related functions.

VA Has Historically Faced Challenges in Managing its IT Resources

VA has experienced longstanding challenges in managing its IT projects and programs, raising questions about the efficiency and effectiveness of its operations and its ability to deliver intended outcomes needed to help advance the department’s mission.

We have issued a number of reports that discuss challenges VA has faced over many years in its efforts to modernize its IT systems and improve its management of IT resources. These include challenges, for example, with modernizing its health information system, tracking software licenses, and managing its cybersecurity workforce. For instance:

· After three unsuccessful attempts between 2001 and 2018, VA began implementing its fourth effort to replace its legacy electronic health record (EHR) system in 2020. In April 2023, after deploying the new system to five of its medical centers, VA paused deployments due to user concerns. In December 2024, VA announced plans for additional deployments restarting in 2026. In March 2025, we reported that VA is making incremental improvements to the new EHR system but much more remains to be done as VA moves to implement planned deployments.[11]

Among its improvements at five initial sites, the department has delivered patient safety and pharmacy enhancements, addressed system trouble ticket resolution, and increased system performance. However, the department continued to address about 1,800 unresolved configuration change requests and initiated additional complex projects to address challenges identified via user feedback. The many changes undertaken to make improvements impact cost estimates and the program schedule. Regarding costs, in 2022 the Institute for Defense Analyses estimated that EHR modernization life cycle costs would total $49.8 billion—$32.7 billion for 13 years of implementation and $17.1 billion for 15 years of sustainment. Updating that estimate to reflect events over the last 2 years, such as the pause, is imperative to understanding the full magnitude of VA’s investment. Similarly, it is critically important that VA update its schedule to informing decision-making. We made three related recommendations and VA concurred, but we noted that the department’s planned actions on updating the cost and schedule did not encompass the modernization’s life cycle.

In addition, we continue to monitor 10 recommendations we made to VA in May 2023 to address issues on change management, user satisfaction, resolution of system trouble tickets, and independent operational assessment deficiencies.[12] VA concurred with the 10 recommendations but has yet to implement them.

As of July 2025, all 13 recommendations remain open. We continue to monitor these open recommendations to ensure the department is well positioned for future deployments.

· VA’s core financial system is approximately 30 years old and is not integrated with other relevant IT systems, which results in inefficient operations and requires complex manual workarounds. Further, it does not provide real-time integration between financial and acquisition information across VA.

We and the VA OIG have reported on VA’s efforts to replace its legacy system.[13] Two previous attempts to replace this legacy system—the Core Financial and Logistics System (CoreFLS) and the Financial and Logistics Integrated Technology Enterprise (FLITE)—failed after years of development and hundreds of millions of dollars in cost. The current approach is implementing the Integrated Financial and Acquisition Management System (iFAMS), which will replace aging systems with one integrated system, as part of the Financial Management Business Transformation (FMBT). These three efforts reflect varying approaches that the department has taken to achieve modernized financial management and acquisition systems. They also reflect the department’s weaknesses that were identified in project management and cost and schedule estimating.

We previously made two recommendations in our March 2021 report to VA.[14] Specifically, we recommended that VA ensure that the FMBT program’s cost estimate and schedule were consistent with IT management best practices. VA concurred with the recommendations, but the department has yet to implement them.

· VA spends billions of dollars annually for IT and cyber-related investments, including commercial software licenses.[15] In a January 2024 government-wide report, GAO noted that while VA identified its five most widely used software vendors with the highest quantity of licenses installed, VA faced challenges in determining whether it was purchasing too many or too few of these software licenses. Specifically, VA was not tracking the appropriate number of licenses for each item of software currently in use. Additionally, the department did not compare inventories of software licenses that were currently in use to purchase records on a regular basis.

Until VA adequately assesses the appropriate number of licenses, it cannot determine whether it is purchasing too many licenses or too few. GAO recommended that VA track licenses in use within its inventories and compare them with purchase records. VA concurred with this and one other recommendation and is taking preliminary actions to track software license usage. Implementation of these recommendations would allow VA to identify opportunities to reduce costs on duplicate or unnecessary licenses. As of July 2025, both recommendations remain open.

· We have also issued reports about governmentwide actions related to the federal cybersecurity workforce. With regard to VA, in January 2025 we reported that VA fully implemented practices related to setting the strategic direction for the cybersecurity workforce.[16] However, additional work remained to complete practices related to conducting cybersecurity workforce analyses, developing a workforce action plan, implementing and monitoring the plan, and evaluating the results of actions taken. We made five recommendations to VA on this topic, all of which remain open as of July 2025.

· In our September 2024 government-wide review on cloud computing procurement, we found that VA fully addressed two of the five cloud computing procurement requirements established by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB).[17] VA addressed the requirements related to ensuring the agency’s chief information officer oversaw modernization, as well as iteratively improving agency policies and guidance. VA’s guidance also partially addressed OMB’s requirement for having cloud service level agreements in place. However, VA did not have guidance in place that addressed the requirements for standardizing cloud contract service level agreements and ensuring continuous visibility in high value asset contracts. Accordingly, we made four recommendations to VA to address the three requirements, and VA concurred with our recommendations. The four recommendations remain open.

We will continue to monitor the progress made by VA in implementing the recommendations.

VA Requested $7.3 Billion for IT in Fiscal Year 2026

VA has requested $7.3 billion to fund its IT systems in fiscal year (FY) 2026, a $298 million (about 4 percent) overall decrease from its enacted budget in FY 2025.[18] In addition, VA has requested funding to support 6,992 full-time equivalent employees in FY 2026, which is an overall decrease of about 11.7 percent from the 2025 enacted levels. Further, the request proposes legislative changes to VA’s budget authority by removing subaccounts for development, operations and maintenance, and pay. VA also requested an IT appropriation with a period of availability of three years, rather than the one-year funds it currently receives.

VA’s budget request also reflects a range of planned reforms. For example, VA is requesting a total of $3.5 billion for the EHR modernization program. This is an increase of nearly $2.2 billion over the FY 2025 request. VA plans to use these funds to accelerate the deployment of the EHR to additional locations.

In addition, VA’s budget request’s proposed amounts also reflect reduced spending on duplicative legacy systems and pauses in procurement of new systems until VA can conduct a full review of them, resulting in about a $500 million reduction. VA also seeks to streamline administrative practices for about $40 million in savings. Further, VA’s request states that a reduction of 931 full-time equivalents is consistent with maturing technology delivery models and a shift toward automation and digital services.

GAO Has Identified Leading Practices to Assess Agency Reform Efforts

We have found that effective reform efforts require a combination of people, processes, technologies, and other critical success factors to achieve results. Our prior work describes 12 leading practices that federal agencies can use in agency reform efforts, including efforts to streamline and improve the efficiency and effectiveness of operations.[19]

The 12 leading practices fall under four broad categories, including: (1) goals and outcomes, (2) process for developing reforms, (3) implementing the reforms, and (4) strategically managing the federal workforce. Our prior work additionally identifies key questions that can be used to assess the development and implementation of agency reforms. See figure 1 for a list of the leading practices and examples of key questions.[20]

Figure 1: Leading Practices and Selected Key Questions for Assessing Agency Reform Efforts

Goals and Outcomes

Efforts to reform government are immensely complex activities that require agreement on both the goals to be achieved and the means for achieving them. Establishing a mission-driven strategy and identifying specific desired outcomes to guide that strategy are critical to achieving intended results. This includes:

Determining the appropriate role of the federal government. It is important for agencies to reexamine the role of the federal government in carrying out specific activities by reviewing their continued relevance and determining whether the federal government is best suited to provide that service.

· To what extent have the proposed reforms included consideration for other levels of government or sectors’ ability or likelihood to invest their own resources to address the underlying challenges?

· To what extent has the agency identified any risks of using contractors to perform activities, and if so, has it developed appropriate risk mitigating strategies?

Establishing goals and outcomes. Agreement on specific goals can help decision makers determine what problems genuinely need to be fixed, how to balance differing objectives, and what steps need to be taken to create long-term gains.

· To what extent has the agency established clear outcome-oriented goals and performance measures for the proposed reforms?

· To what extent has the agency shown that the proposed reforms align with the agency’s mission and strategic plan?

· To what extent has the agency included both short-term and long-term efficiency initiatives in the proposed reforms?

Process for Developing Reforms

Successful reforms require an integrated approach that involves employees and key stakeholders (such as system users) and is built on the use of data and evidence. Reforms should also address agency management challenges, such as those we have identified as fragmented, duplicative, or overlapping or high-risk. These include:

Involving employees and key stakeholders. It is important for agencies to directly and continuously involve their employees, the Congress, and other key stakeholders in the development of any major reforms. Involving employees, customers, system users, and other stakeholders helps facilitate the development of reform goals and objectives. Incorporating insights from a frontline perspective also facilitates buy-in (or success) and increases customer acceptance of any changes.

· How and to what extent has the agency consulted with the Congress, system users, and other key stakeholders, to develop its proposed reforms?

· How and to what extent has the agency engaged employees and employee unions in developing the reforms (e.g., through surveys, focus groups) to gain their ownership for the proposed changes?

· How and to what extent has the agency involved other stakeholders, as well as its customers and other agencies serving similar customers or supporting similar goals, in the development of the proposed reforms to ensure the reflection of their views?

Using data and evidence. Agencies are better equipped to address management and performance challenges when managers effectively use data and evidence, such as from program evaluations and performance data that provide information on how well a program or agency is achieving its goals.

· What data and evidence has the agency used to develop and justify its proposed reforms?

· How has the agency determined that the evidence contained sufficiently reliable data to support a business case or cost-benefit analysis of the reforms?

Addressing fragmentation, overlap, and duplication. Agencies may be able to

achieve greater efficiency or effectiveness by reducing or better managing

programmatic fragmentation, overlap, and duplication.[21]

· To what extent have the agency reform proposals helped to reduce or better managed the identified areas of fragmentation, overlap, or duplication?

· To what extent has the agency identified cost savings or efficiencies that could result from reducing or better managing areas of fragmentation, overlap, and duplication?

Addressing high-risk areas and longstanding management challenges. Reforms improving the effectiveness and responsiveness of the federal government often require addressing longstanding weaknesses in how some federal programs and agencies operate.

· What management challenges and weaknesses are the reform efforts designed to address?

· How has the agency identified and addressed critical management challenges in areas such as information technology, cybersecurity, acquisition management, and financial management that can assist in the reform process?

· How have findings and open recommendations from GAO and the agency Inspector General been addressed in the proposed reforms?

Implementing the Reforms

Our prior work on organizational transformations shows that incorporating change management practices improves the likelihood of successful reforms.[22] It is also important to recognize agency cultural factors that can either help or inhibit reform efforts and how change management strategies may address these potential issues. This includes:

Leadership focus and attention. Organizational transformations should be led by a dedicated team of high-performing leaders within the agency.

· Has the agency designated a leader or leaders to be responsible for the implementation of proposed reforms?

· How will the agency hold the leader or leaders accountable for successful implementation of the reforms?

· Has the agency established a dedicated implementation team that has the capacity, including staffing, resources, and change management expertise, to manage the reform process?

Managing and monitoring. Implementing major transformation can span several years and must be carefully and closely monitored.

· How has the agency ensured their continued delivery of services during reform implementation?

· What implementation goals and a timeline have been set to build momentum and show progress for the reforms?

· Has the agency put processes in place to collect the needed data and evidence that will effectively measure the reforms’ outcome-oriented goals?

Strategically Managing the Federal Workforce

At the heart of any serious change management initiative are the people—because people define the organization’s culture, drive its performance, and embody its knowledge base. Failure to adequately address a wide variety of people or cultural issues can lead to unsuccessful change. Areas to consider are:

Employee engagement. Increased levels of engagement can lead to better organizational performance, and agencies can sustain or increase their levels of employee engagement and morale even as employees weather difficult external circumstances. [23]

· How does the agency plan to sustain and strengthen employee (user) engagement during and after the reforms?

Strategic workforce planning. Strategic planning should precede any staff realignments or downsizing, so that changed staff levels do not inadvertently produce skills gaps or other adverse effects that could result in increased use of overtime and contracting.

· To what extent has the agency conducted strategic workforce planning to determine whether it will have the needed resources and capacity in place for the proposed reforms or reorganization?

· To what extent does the agency track the number and cost of contractors supporting its agency mission and the functions those contractors are performing?

· How has the agency ensured that actions planned to maintain productivity and service levels do not cost more than the savings generated by reducing the workforce?

· What succession planning has the agency developed and implemented for leadership and other key positions in areas critical to reforms and mission accomplishment?

· To what extent have the reforms included important practices for effective recruitment and hiring such as customized strategies to recruit highly specialized and hard-to-fill positions?

Workforce reduction strategies. It is critical for an agency to carefully consider how to strategically downsize the workforce and maintain staff resources to carry out its mission through considering staffing plans and personnel costs, organizational design, and the appropriateness of backfilling positions as they become vacant.

· To what extent has the agency considered skills gaps, mission shortfalls, increased contracting and spending, and challenges in aligning workforce with agency needs?

· To what extent has the agency linked proposed “early outs” and “buyouts” to specific organizational objectives?

Employee performance management. Effective performance management systems provide supervisors and employees with the tools they need to improve performance.

· To what extent has the agency aligned its employee performance management system with its planned reform goals?

· How has the agency included accountability for proposed change implementation in the performance expectations and assessments of leadership and staff at all levels?

· As part of the proposed reform development process, to what extent has the agency assessed its performance management to ensure it creates incentives for and rewards top performers, while ensuring it deals with poor performers?

In summary, consideration of leading practices and relevant questions can benefit VA’s development and implementation of its reform efforts. Further, if effectively implemented, such efforts can result in success in overcoming VA’s long history of ineffectively managing IT resources.

Chairman Barrett, Ranking Member Budzinski, and Members of the Subcommittee, this concludes my prepared statement. I would be happy to answer any questions that you may have at this time.

GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments

If you or your staff have any questions about this testimony, please contact Carol C. Harris at harriscc@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this statement.

GAO staff who made key contributions to this testimony include Jennifer Stavros-Turner (Assistant Director), Kevin Smith (Analyst-in-Charge), Chris Businsky, Jonnie Genova, Scott Pettis, Sarah Veale, and Whitney Starr.

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]For examples of GAO’s past reports in this area, see: GAO, Electronic Health Records: VA Making Incremental Improvements in New System but Needs Updated Cost Estimate and Schedule, GAO‑25‑106874 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 12, 2025); Financial Management Systems: VA Should Improve Its Risk Response Plans, GAO‑24‑106858 (Washington, D.C.: July 23, 2024); Electronic Health Records: VA Needs to Address Management Challenges with New System, GAO‑23‑106731 (Washington, D.C.: May 18, 2023); VA Financial Management System: Additional Actions Needed to Help Ensure Success of Future Deployments, GAO‑22‑105059 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 24, 2022); and Electronic Health Records: VA Needs to Address Data Management Challenges for New System, GAO‑22‑103718 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 1, 2022). For examples of the VA Office of Inspector General’s past reports in this area, see: Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Inspector General, VA Needs to Strengthen Controls to Address Electronic Health Record System Major Performance Incidents, Report #22-03591-231 (Sept. 23, 2024); Lessons Learned for Improving the Integrated Financial and Acquisition Management System’s Acquisition Module Deployment, Report #23-00151-117 (July 10, 2024); and Improvements Needed in Integrated Financial and Acquisition Management System Deployment to Help Ensure Program Objectives Can Be Met, Report #21-01997-69 (Mar. 28, 2023).

[2]VA’s IT issues were highlighted in our 2015 high-risk report and subsequent high-risk reports. See GAO, High-Risk Series: An Update, GAO‑15‑290 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 11, 2015); High-Risk Series: Progress on Many High-Risk Areas, While Substantial Efforts Needed on Others, GAO‑17‑317 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 15, 2017); High-Risk Series: Substantial Efforts Needed to Achieve Greater Progress on High-Risk Areas, GAO‑19‑157SP (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 6, 2019); High-Risk Series: Dedicated Leadership Needed to Address Limited Progress in Most High-Risk Areas, GAO‑21‑119SP (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 2, 2021); and High-Risk Series: Efforts Made to Achieve Progress Need to Be Maintained and Expanded to Fully Address All Areas, GAO‑23‑106203 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 20, 2023).

[3]GAO, High-Risk Series: Heightened Attention Could Save Billions More and Improve Government Efficiency and Effectiveness, GAO‑25‑107743 (Feb. 25, 2025).

[4] For more information, see GAO, Government Reorganization: Key Questions to Assess Agency Reform Efforts, GAO-18-427 (Washington, D.C.: Jun. 13, 2018). We use the term “reform” to broadly include any organizational changes and efforts to streamline and improve the efficiency and effectiveness of government operations and workforce.

[5]GAO, High-Risk Series: Critical Actions Needed to Urgently Address IT Acquisition and Management Challenges, GAO‑25‑107852 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 23, 2025).

[6]The requirement for agencies to designate a CIO is codified at 44 U.S.C. § 3506(a)(2)(A). See also 40 U.S.C. § 11315, Agency Chief Information Officer.

[7]40 U.S.C. § 11315(c).

[8]Federal Information Technology Acquisition Reform provisions of the Carl Levin and Howard P. ‘Buck’ McKeon National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2015, Pub. L. No. 113-291, div. A, title VIII, subtitle D, 128 Stat. 3292, 3438-50 (Dec. 19, 2014).

[9]The provisions apply to VA and the other agencies covered by the Chief Financial Officers Act of 1990, 31 U.S.C. § 901(b). However, FITARA has generally limited application to the Department of Defense. The 24 Chief Financial Officers Act of 1990 agencies are the Departments of Agriculture, Commerce, Defense, Education, Energy, Health and Human Services, Homeland Security, Housing and Urban Development, Justice, Labor, State, the Interior, the Treasury, Transportation, and Veterans Affairs; the Environmental Protection Agency; the General Services Administration; the National Aeronautics and Space Administration; the National Science Foundation; the Nuclear Regulatory Commission; the Office of Personnel Management; the Small Business Administration; the Social Security Administration; and the U.S. Agency for International Development.

[10]See, for example, Office of Management and Budget, Memorandum M-16-15: Federal Cybersecurity Workforce Strategy (July 12, 2016) and U.S. Office of Personnel Management, Workforce Planning Guide (Washington, D.C.: November 2022).

[11]GAO, Electronic Health Records: VA Making Incremental Improvements in New System but Needs Updated Cost Estimate and Schedule, GAO-25-106874 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 12, 2025).

[12]GAO, Electronic Health Records: VA Needs to Address Management Challenges with New System, GAO-23-106731 (Washington, D.C.: May 18, 2023).

[13]VA OIG, Issues at VA Medical Center Bay Pines, Florida and Procurement and Deployment of the Core Financial and Logistics System (CoreFLS), 04-01371-177 (Washington, D.C.: Aug. 11, 2004); GAO-10-40 and VA OIG, Audit of the FLITE Strategic Asset Management Pilot Project, 09-03861-238 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 14, 2010); and GAO, Financial Management Systems: VA Should Improve Its Risk Response Plans, GAO-24-106858 (Washington, D.C.: July 23, 2024) and VA Financial Management System: Additional Actions Needed to Help Ensure Success of Future Deployments, GAO-22-105059 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 24, 2022).

[14]GAO, Veterans Affairs: Ongoing Financial Management System Modernization Program Would Benefit from Improved Cost and Schedule Estimating, GAO-21-227 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 24, 2021).

[15]GAO, Veterans Affairs: Actions Needed to Address Software License Challenges, GAO-25-108475 (Washington, D.C.: May 19, 2025); Federal Software Licenses: Agencies Need to Take Action to Achieve Additional Savings, GAO-24-105717 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 29, 2024).

[16]See, for example, GAO, Cybersecurity Workforce: Departments Need to Fully Implement Key Practices, GAO-25-106795 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 16, 2025); Cybersecurity Workforce: Agencies Need to Accurately Categorize Positions to Effectively Identify Critical Staffing Needs, GAO-19-144 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 12, 2019); and Cybersecurity Workforce: National Initiative Needs to Better Assess Its Performance, GAO-23-105945 (Washington, D.C.: Jul. 27, 2023).

[17]GAO, Cloud Computing: Agencies Need to Address Key OMB Procurement Requirements, GAO-24-106137 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 10, 2024). Purchasing IT services through a cloud service provider enables agencies to avoid paying directly for all the computing resources that would typically be needed to provide such services. As such, cloud computing offers federal agencies a means to buy services more quickly and possibly at a lower cost than building, operating, and maintaining these computing resources themselves.

[18]The IT Systems total request for FY 2026 includes discretionary funding from the IT Systems appropriation and mandatory funding from the Toxic Exposures Fund.

[19]GAO, Government Reorganization: Key Questions to Assess Agency Reform Efforts, GAO-18-427 (Washington, D.C.: Jun. 13, 2018).

[20]For each of these categories, we identify subcategories for which we include specific questions that agencies, Congress, and OMB should ask about planned reform efforts. For the purpose of this testimony, we have selected for inclusion questions that may be relevant to VA’s IT reorganization for each subcategory. A full list of questions can be found in GAO-18-427.

[21]For more information, see our most recent annual report: GAO, 2025 Annual Report: Opportunities to Reduce Fragmentation, Overlap, and Duplication and Achieve an Additional One Hundred Billion Dollars or More in Future Financial Benefits, GAO-25-107604 (Washington, D.C.: May 13, 2025)

[22]GAO, Results-Oriented Cultures: Implementation Steps to Assist Mergers and Organizational Transformations, GAO-03-669 (Washington, D.C.: Jul. 2, 2003)

[23]In a previous review of trends in federal employee engagement, we identified six key drivers of engagement based on our analysis of selected questions in the Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey. Drivers include, for example, constructive performance conversations and work-life balance. See GAO, Federal Workforce: Additional Analysis and Sharing of Promising Practices Could Improve Employee Engagement and Performance, GAO-15-585 (Washington, D.C.: Jul. 14, 2015) for more details.