PUERTO RICO

Fiscal Conditions Have Improved but Risks Remain

Statement of Michelle

Sager, Managing Director,

Strategic Issues

Before the Subcommittee on Indian and Insular Affairs, Committee on Natural Resources, House of Representatives

For Release on Delivery Expected at 10:00 a.m. ET

GAO-25-108629

United States Government Accountability Office

A statement before the Subcommittee on Indian and Insular Affairs, Committee on Natural Resources, House of Representatives.

For more information, contact: Michelle Sager at sagerm@gao.gov

What GAO Found

The factors that contributed to the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico’s debt crisis in 2015 included the territory’s persistent deficits and its use of debt to manage these deficits. In 2018, GAO identified specific causes of its deficits based on interviews with Puerto Rico officials, federal officials, and other relevant experts, along with a literature review. These causes included inadequate financial management and oversight practices, policy decisions such as using debt proceeds to balance budgets, and a prolonged economic contraction.

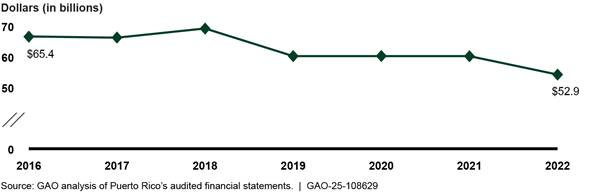

Puerto Rico’s fiscal conditions have improved since 2016. Its most recent audited government-wide financial statements—from fiscal year 2022—show a total net surplus of $1.9 billion, a reversal from prior years which predominantly had net deficits. More recently, in its 2024 fiscal plan for Puerto Rico, the Financial Oversight and Management Board cited the territory’s progress in aligning revenues and expenses and stabilizing its finances. Additionally, the territory has restructured most of its debt using the debt restructuring processes established by the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA), though negotiations and litigation over the debt of its public utility are ongoing. Between fiscal years 2016 and 2022, Puerto Rico’s public debt decreased by $12.5 billion, or 19 percent, as shown below.

Puerto Rico’s Total Public Debt Outstanding Fiscal Years 2016 to 2022

While Puerto Rico’s fiscal condition has improved in recent years, the territory continues to face fiscal and economic risks. These include access to reliable and affordable electricity, increasingly powerful storms and rising temperatures, declining population, and pension liabilities. Additionally, the territory’s financial management and reporting issues, such as delays in issuing audited financial statements, pose risks to its ability to make informed decisions.

Why GAO Did This Study

After accumulating debt for many years, Puerto Rico began defaulting on debt payments in 2015. In response, Congress passed, and the President signed, PROMESA.

This act established a process for Puerto Rico to restructure its debts and created the Financial Oversight and Management Board, with broad powers of budgetary and financial control. PROMESA also includes provisions for GAO to 1) examine factors contributing to Puerto Rico’s debt crisis and federal actions for preventing a future one and 2) study fiscal issues in Puerto Rico and the other U.S. territories and periodically report on their public debt.

This statement summarizes GAO’s key findings from this work related to (1) the factors that contributed to the debt crisis in Puerto Rico, (2) how fiscal and economic conditions have changed since 2016, and (3) the fiscal and economic risks that Puerto Rico faces.

This statement is based on GAO reports issued between October 2017 and June 2025. Detailed information on the objectives, scope, and methodology can be found within each report.

Chairman Hurd, Ranking Member Leger Fernández, and Members of the Subcommittee:

Thank you for the opportunity to discuss our work on the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico’s public debt and economic outlook. After accumulating debt over many years, Puerto Rico began defaulting on debt payments in 2015. In response, Congress passed and the President signed the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA) in June 2016.[1] PROMESA established a process for Puerto Rico to restructure its debts and created the Financial Oversight and Management Board (FOMB), with broad powers of budgetary and financial control over Puerto Rico.

PROMESA included a provision for us to examine factors contributing to the debt crisis and federal actions for preventing a future one, which we reported on in 2018.[2] PROMESA also includes a provision for us to study fiscal issues in U.S. territories and periodically report on the public debt of each territory.[3] We have issued five reports on the territories’ public debt, most recently in June 2025.[4] My remarks today are based on the findings of those reports and will cover (1) the factors that contributed to the debt crisis in Puerto Rico, (2) how fiscal and economic conditions have changed since 2016, and (3) the fiscal and economic risks that Puerto Rico faces.

Details on the prior reports’ objectives, scope, and methodologies is available in each of the reports cited throughout this statement. In addition, for this hearing statement, we reviewed FOMB’s 2024 fiscal plan and annual report for Puerto Rico.[5] We conducted the work on which this statement is based in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Multiple Factors Contributed to Puerto Rico’s 2015 Debt Crisis

In 2018 we reported that the Puerto Rico government’s persistent fiscal deficits contributed to the territory’s 2015 debt crisis.[6] At that time, the territory had operated in a fiscal deficit in all years since 2002. Based on interviews with Puerto Rico officials, federal officials, and other relevant experts, along with a literature review, we identified the following specific and sometimes inter-related factors that contributed to these deficits:

· Inadequate financial management and oversight practices. At the time of our 2018 report, Puerto Rico lacked controls for effective financial management and oversight. This resulted in the government overestimating the amount of revenue it would collect and spending more than appropriated amounts.

· Policy decisions. Among the decisions that led to deficits were (1) allowing the use of debt proceeds to balance budgets, (2) insufficiently addressing public pension funding shortfalls, and (3) inadequately managing the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority’s (PREPA) financial condition.

· Prolonged economic contraction. Beginning in 2005, Puerto Rico suffered a prolonged period of economic contraction, due to factors such as outmigration and the high cost of importing goods and energy.

Puerto Rico’s Fiscal and Economic Conditions Have Improved Since 2016

Puerto Rico Has Restructured Most of Its Debt

PROMESA created a legal framework for Puerto Rico to restructure its debt. Under that framework, FOMB has the authority to petition U.S. courts on Puerto Rico’s behalf.[7] The board has used this mechanism to complete a number of debt restructurings. Notably, in March 2022, the Government of Puerto Rico issued $7.4 billion in General Obligation Restructured Bonds to existing bondholders, replacing outstanding debt obligations totaling $34.3 billion (a 78 percent reduction).[8] According to FOMB’s 2024 Annual Report, the completed restructurings have reduced $63 billion in debt and other claims to $28.1 billion.

While Puerto Rico has restructured most of its debt, negotiations and litigation over the debt of its electric utility are ongoing. FOMB filed its proposed plan for the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority’s (PREPA) debt restructuring in December 2022. In June 2024 the U.S. First Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that PREPA’s bondholders had a lien and non-recourse claim on PREPA’s net revenues, a change that increased the bondholders’ allowable claim from $2.4 billion to $8.5 billion.[9]

Puerto Rico’s Fiscal Condition Has Improved Since 2016

Puerto Rico’s most recent audited government-wide financial statements—from fiscal year 2022—show a total net surplus of $1.9 billion, a reversal from prior fiscal years which predominantly had net deficits. Additionally, in its 2024 Fiscal Plan for Puerto Rico, FOMB cited the territory’s progress in aligning revenues and expenses and stabilizing its finances.[10] As stated previously, the territory’s persistent deficits were a contributing factor to its debt crisis.

Puerto Rico’s debt levels have also improved since 2016, thanks in large part to the restructurings described previously. According to the territory’s audited financial statements, in fiscal year 2022 total public debt was $12.5 billion lower than it was in fiscal year 2016.[11] This represents a total public debt reduction of 19 percent, as shown in figure 1. While more recent audited financial statements are not available, Puerto Rico officials told us that the government has not issued any tax-supported debt unrelated to restructuring since 2022.

Figure 1: Total Public Debt Outstanding Fiscal Years 2016 to 2022

Note: Fiscal year 2022 is the most recent year for which audited financial data are available.

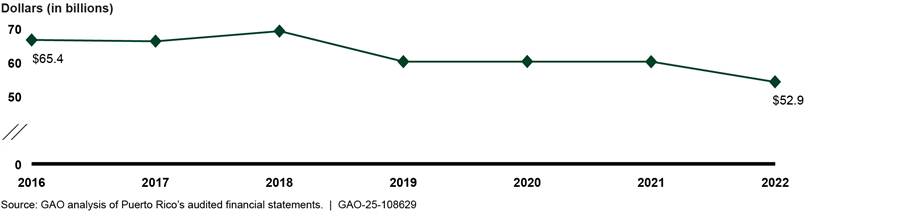

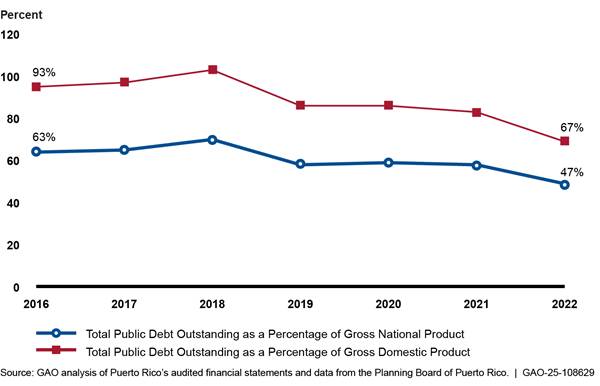

In fiscal year 2016, Puerto Rico’s public debt represented 93 percent of its gross national product (GNP) and 63 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP).[12] As of fiscal year 2022, the total public debt represented 67 percent of GNP and 47 percent of GDP, as shown in figure 2.

Figure 2: Total Public Debt Outstanding As a Share of GNP and GDP, Fiscal Years 2016 to 2022

Notes: Fiscal year 2022 is the most recent year for which audited financial data are available. While gross domestic product (GDP) measures the value of goods and services produced inside a country, or for the purpose of this statement, a territory, gross national product (GNP) measures the value of goods and services produced by its residents. GNP includes production from residents abroad and excludes production by foreign companies in a country. In Puerto Rico, GDP has consistently been greater than GNP. This means that production by foreign companies in Puerto Rico is larger than production by Puerto Rican residents in the territory and abroad. For this reason, according to the U.S. Department of the Treasury, GNP is generally a more representative measure of Puerto Rico’s economic activity than GDP.

Puerto Rico Has Strengthened Its Fiscal Policies and Institutions

The government of Puerto Rico and FOMB have worked to strengthen Puerto Rico’s fiscal management. As specified in PROMESA, FOMB certifies the fiscal plans and annual budget of the government of Puerto Rico, and several of its major component units. FOMB also reviews new legislation to ensure that new laws are consistent with the fiscal plan. If FOMB finds that legislation that incurs expenses or reduces revenue without offsetting measures is inconsistent with the fiscal plan, it sends a notification to Puerto Rico’s government and directs it to eliminate the inconsistency or provide an explanation FOMB finds reasonable and appropriate.[13] For example, in 2024, FOMB determined an enacted statute that would have set a new base salary for school cafeteria employees was inconsistent with the fiscal plan because, among other things, the act did not include corresponding savings or new revenue to offset the additional cost.

Additionally, the government adopted a debt management policy in 2022 to help guard against unsustainable borrowing. The policy’s requirements include:

· Generally, new long-term issuances of tax-supported debt must be for capital improvements or refinancing for savings. As stated previously, the territory’s use of debt proceeds to balance its budget prior to PROMESA is one of the factors that contributed to the territory’s accumulation of unsustainable debt.

· Maximum annual tax-supported debt service cost cannot exceed 7.94 percent of the average debt policy revenues from the preceding 2 fiscal years.[14]

The creation of the Legislative Assembly Budget Office, or Oficina de Presupuesto de la Asamblea Legislativa (OPAL) also marked an opportunity for increased fiscal transparency. Created in 2023 by the Puerto Rican legislature, OPAL provides estimates of the fiscal effect of legislative proposals. These estimates can help the legislature better understand how proposed measures would affect levels of revenue or expenses. However, the use of these estimates in the decision-making process is currently at the discretion of the legislature. OPAL officials told us they produced 185 estimates in fiscal year 2024, including estimates for 11 bills that became law, while 180 laws were enacted without estimates. Government officials told us that it is common for the legislature to pass bills that OPAL warned would have adverse fiscal consequences.

Puerto Rico’s GNP Has Grown Modestly in Recent Years

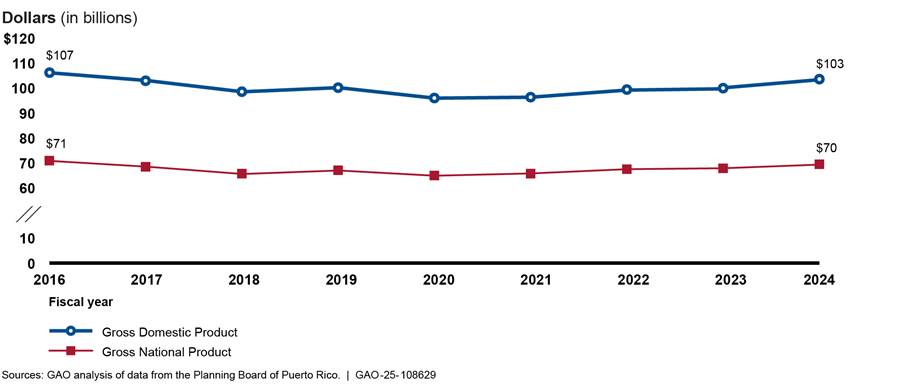

Puerto Rico’s economy grew in fiscal year 2024, continuing three years of modest growth. Between fiscal years 2023 and 2024, Puerto Rico’s real GNP increased 2 percent, to $85.6 billion, and its real GDP increased 3 percent, to $125.8 billion (see fig. 3). Puerto Rico’s annual real GNP growth between fiscal years 2020 and 2024 averaged 0.7 percent and its annual real GDP growth averaged 0.6 percent. This is a reversal from the prior period (fiscal years 2016 through 2019), during which both the territory’s real GDP and real GNP on average declined about 2 percent annually.

Figure 3: Puerto Rico’s Real GDP and GNP Fiscal Years 2016 through 2024 (in 2017 dollars)

Note: When comparing gross domestic product (GDP) or gross national product (GNP) over time, we adjust the data for inflation so that all figures are in a consistent year’s values. While GDP measures the value of goods and services produced inside a country, or for the purpose of this statement, a territory, GNP measures the value of goods and services produced by its residents. GNP includes production from residents abroad and excludes production by foreign companies in a country. In Puerto Rico, GDP has consistently been greater than GNP. This means that production by foreign companies in Puerto Rico is larger than production by Puerto Rican residents in the territory and abroad. For this reason, according to the U.S. Department of the Treasury, GNP is generally a more representative measure of Puerto Rico’s economic activity than GDP.

According to Puerto Rico officials, the influx of federal funds provided to mitigate the effects of Hurricanes Irma and Maria in 2017 and the COVID-19 pandemic contributed to Puerto Rico’s economic growth. The officials expressed concern that the depletion of these funds could diminish commercial and economic activity, which would lower government revenue.

Despite recent growth, Puerto Rico’s Economic Activity Index—reflecting a number of economic indicators—was lower for each month between September 2024 and February 2025 than the same month in the previous year, which could indicate Puerto Rico’s economy is slowing.[15]

Puerto Rico Faces Fiscal and Economic Risks

Puerto Rico Continues to Have Financial Management and Reporting Issues

Puerto Rico’s continued financial statement delays and issues obtaining clean audit opinions present risks. The territory’s fiscal year 2023 and 2024 financial statements were not available as of June 30, 2025. Additionally, several of the departments included in Puerto Rico’s primary government also have recurring audit findings related to financial reporting and federal awards, along with some questioned federal award costs.[16] Timely and reliable financial reporting is important to ensure Puerto Rico can make informed debt management decisions and access capital markets if needed.

Puerto Rico has begun to implement an enterprise resource planning system, which is intended to streamline the government’s financial, supply chain, human capital management, and payroll systems. Puerto Rico’s auditors reported they expect full implementation of the system will resolve a significant portion of Puerto Rico’s issues with financial reporting and internal controls. The government began implementing the system in 2022, but the implementation has faced delays. To address delays, the government revised its implementation timeline to prioritize the essential financial functions, focusing on the financial management and supply chain modules.

Pension and Other Postemployment Benefit Liabilities Represent 73 percent of GNP

Pension and other postemployment benefit liabilities continue to represent a fiscal risk. Liability for both pensions and postemployment benefits for the primary government and component units totaled $57.0 billion in fiscal year 2022, representing 50 percent of Puerto Rico’s GDP in fiscal year 2022, and 73 percent of its GNP. Puerto Rico’s total net pension liability in fiscal year 2022 was $55.1 billion, a 9 percent increase from fiscal year 2020.[17] The territory’s fiscal year 2022 total liability for other postemployment benefits, such as health care, was $1.9 billion, a 2 percent decrease from fiscal year 2020. Puerto Rico government officials told us they expect these liabilities to decrease in the future due to reductions in benefits that were part of the debt restructuring.

Puerto Rico established a pension trust in 2022 as part of its Plan of Adjustment to support future pension payments. The trust will be funded through annual contributions until fiscal year 2031, according to Puerto Rico government officials. The payments are calculated using a formula based on Puerto Rico’s annual surpluses and are projected to be fully funded (i.e., the pension fund assets will be equal to or greater than the estimated liability) by fiscal year 2039. The government will be able to withdraw funds to help pay for pensions under certain conditions starting in fiscal year 2032, according to government officials. As of April 2025, Puerto Rico has contributed a total of $3.4 billion to the pension reserve trust, with the most recent payment of $906 million made in November 2024, according to Puerto Rico government officials.

Population Changes Affect Revenue and Economic Activity

Population decline and an aging population remain concerns. From 2008 to 2022, according to Census Bureau data, Puerto Rico’s population declined from 4.0 million to 3.2 million. Officials from OPAL estimated that if population had remained stable over that period the economy would have grown by 1.4 percent rather than contracting by 15.8 percent.

Puerto Rico government officials recognize that future population loss poses a risk to Puerto Rico’s continued economic growth and stability, as fewer working-age residents lead to lower employment tax revenue and diminished economic activity. These officials told us they remain optimistic that increased economic growth and infrastructure improvements may retain and attract residents.

Reliable Electricity is Critical to Puerto Rico’s Economic Growth

Puerto Rico’s power grid has still not recovered from the damage caused by the 2017 hurricanes, and electricity in Puerto Rico continues to be relatively expensive. In January 2025, the average price of electricity was about 29 cents per kilowatt hour, about 80 percent higher than the average price in the mainland United States in the same period, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.[18] Also, residents in Puerto Rico lose power more often than residents in any state.[19] Equipment failures caused several major outages in 2024.[20]

The Puerto Rican government and PREPA have been working on an energy sector transformation since 2018. As part of the transformation, LUMA Energy—a private company—assumed operation of PREPA’s electricity transmission system in 2021. Genera PR—a separate private company—began to operate, maintain, and decommission PREPA’s aging power-generation assets in 2023. Additionally, Puerto Rico’s then Governor-elect established a working group in December 2024 to review Puerto Rico’s energy policy. In January 2025, the Governor created a new position to oversee Puerto Rico’s grid recovery, which includes supervising Genera PR and LUMA Energy.

Improving the reliability and cost of Puerto Rico’s electricity is critical to attract and retain business and to support sustained economic growth. Rising energy prices are a risk to balancing spending and revenue in coming years, according to Puerto Rico officials. Officials also told us that energy prices may pose more of a risk to Puerto Rico than to the mainland because the territory is more dependent on fossil fuels to generate electricity.

Climate Risks Pose Challenges

Puerto Rico is vulnerable to increasingly powerful storms, such as Hurricanes Irma and Maria, which caused widespread damage in 2017 to critical infrastructure, livelihoods, and property. Additionally, a 2024 report from Puerto Rico’s Department of Natural and Environmental Resources estimated that Puerto Rico will lose $380 billion in GDP by 2050 if global temperatures increase by 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.[21]

Chairman Hurd, Ranking Member Leger Fernández and Members of the Subcommittee, this concludes my statement. I would be pleased to respond to any questions that you may have.

Related GAO Products

GAO, U.S. Territories: Public Debt Outlook, GAO‑18‑160 (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 2, 2017)

GAO, Puerto Rico: Factors Contributing to the Debt Crisis and Potential Federal Actions to Address Them, GAO‑18‑387 (Washington, D.C.: May 9, 2018)

GAO, U.S. Territories: Public Debt Outlook – 2019 Update, GAO‑19‑525 (Washington, D.C.: June 28, 2019)

GAO, U.S. Territories: Public Debt Outlook – 2021 Update, GAO‑21‑508 (Washington, D.C.: June 30, 2021)

GAO, U.S. Territories: Public Debt Outlook – 2023 Update, GAO‑23‑106045 (Washington, D.C.: June 29, 2023)

GAO, U.S. Territories: Public Debt and Economic Outlook – 2025 Update, GAO‑25‑107560 (Washington, D.C.: June 30, 2025)

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1] Pub. L. No. 114-187, § 410, 130 Stat. 549 (2016).

[2]Pub. L. No. 114-187, § 410, 130 Stat. at 594; GAO, Puerto Rico: Factors Contributing to the Debt Crisis and Potential Federal Action to Address Them, GAO‑18‑387 (Washington, D.C.: May 9, 2018).

[3]Pub. L. No. 114-187, § 411, 130 Stat. at 594–595.

[4]GAO, U.S. Territories: Public Debt Outlook, GAO‑18‑160 (Washington, D.C.: Oct 2, 2017); U.S. Territories: Public Debt Outlook – 2019 Update, GAO‑19‑525 (Washington, D.C.: Jun 28, 2019); U.S. Territories: Public Debt Outlook – 2021 Update, GAO‑21‑508 (Washington, D.C.: Jun 30, 2021); U.S. Territories: Public Debt Outlook – 2023 Update, GAO‑23‑106045 (Washington, D.C.: Jun 29, 2023); U.S. Territories: Public Debt and Economic Outlook – 2025 Update, GAO‑25‑107560 (Washington, D.C.: Jun 30, 2025).

[5]Financial Oversight and Management Board for Puerto Rico, 2024 Fiscal Plan for Puerto Rico (San Juan, PR: June 6, 2025); Annual Report 2024 (San Juan, PR: January 22, 2025)

[7]Federal bankruptcy laws otherwise prohibit Puerto Rico from authorizing its municipalities and instrumentalities to petition U.S. courts to restructure debt. PROMESA established two debt restructuring processes under Titles III and VI respectively. Title III is similar to municipal bankruptcy and Title VI provides a process by which the debtors and creditors can negotiate and vote on a debt restructuring agreement with a reduced role played by a court.

[8]In addition to the new general obligation bonds, bondholders received cash and Contingent Value Instrument bonds that pay investors if sales tax collections exceed a defined threshold. See Puerto Rico Fiscal Agency and Financial Advisory Authority, Municipal Secondary Market Disclosure Information Cover Sheet: Information regarding the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico General Obligation Restructured Bonds, Series 2022A (San Juan, Puerto Rico: Mar. 16, 2022).

[9]Fin. Oversight & Mgmt. Bd. for P.R. v. U.S. Bank N.A. (In re Fin. Oversight & Mgmt. Bd. for P.R.), 104 F.4th 367 (1st Cir. 2024) (June 12, 2024, opinion withdrawn and replaced with revised opinion dated Nov. 13, 2024).

[10]Financial Oversight and Management Board for Puerto Rico, 2024 Fiscal Plan for Puerto Rico (San Juan, PR: June 5, 2024).

[11]Fiscal year 2022 public debt amounts include several restructured debt obligations that were not settled by the end of the fiscal year. For example, according to unaudited government data, Commonwealth Appropriation Bonds totaling about $1.1 billion were later canceled and extinguished in fiscal year 2023.

For the purposes of this testimony, total public debt outstanding refers to the sum of bonds and other debt held by and payable to the public. Marketable debt securities—primarily bonds with long-term maturities—are the main vehicle by which the territories access capital markets. Our definition of public debt outstanding also includes other debt payable, which may be marketable notes issued by territorial governments, nonmarketable intragovernmental notes, notes and loans held by local banks, federal loans, and intragovernmental loans. Liabilities related to retirement benefits, such as pension payments to retirees, are not included in our definition of public debt, but are discussed as part of the fiscal risks Puerto Rico faces.

[12]While GDP measures the value of goods and services produced inside a country, or for the purpose of this statement, a territory, GNP measures the value of goods and services produced by its residents. GNP includes production from residents abroad and excludes production by foreign companies in a country. In Puerto Rico, GDP has consistently been greater than GNP. This means that production by foreign companies in Puerto Rico is larger than production by Puerto Rican residents in the territory and abroad. For this reason, according to the U.S. Department of the Treasury, GNP is generally a more representative measure of Puerto Rico’s economic activity than GDP.

[13]48 U.S.C. §§ 2141, 2144. The Governor of Puerto Rico is required to submit to FOMB newly enacted territorial laws along with certain estimates, findings, and certifications of consistency with the fiscal plan. 48 U.S.C. § 2144(a)(1), (2). FOMB, after sending required notification that a law is significantly inconsistent with the fiscal plan, is to direct Puerto Rico’s government to eliminate the inconsistency or provide an explanation FOMB finds reasonable and appropriate. 48 U.S.C. § 2144(a)(4). Failure to comply with this FOMB direction authorizes FOMB to take such action as it considers necessary, consistent with PROMESA, to ensure that the enactment or enforcement of the law will not adversely affect the territorial government’s compliance with the Fiscal Plan, including preventing the enforcement or application of the law. 48 U.S.C. § 2144(a)(5). Additionally, if the governor submits a request to the legislature for the reprogramming of any amounts provided in a certified budget, the governor shall submit such request to FOMB, which shall analyze whether the proposed reprogramming is significantly inconsistent with the budget and submit its analysis to the legislature as soon as practicable after receiving the request. 48 U.S.C. § 2144(c)(1). The legislature may not adopt a reprogramming, and no officer or employee of the territorial government may carry out any reprogramming, until FOMB has provided the legislature with an analysis that certifies such reprogramming will not be inconsistent with the fiscal plan and budget. 48 U.S.C. § 2144(c)(2).

[14]Debt policy revenues refer collectively to a broad set of revenues, including those derived from taxes, fees, permits, licenses, fines or other charges imposed, approved or authorized by the Legislative Assembly of the Commonwealth. Tax supported debt includes debt issued by the commonwealth where the payment source is the commonwealth’s collections, as well as debt issued by any government entity that is guaranteed, secured, or payable from these collections. The Debt Management Policy excludes certain types of debt from this definition, such as short-term tax revenue anticipation notes and debt issued in response to a natural disaster. For a more detailed definition see Puerto Rico Fiscal Agency and Financial Advisory Authority, Puerto Rico Debt Management Policy, (San Juan, PR: Mar. 9, 2022).

[15]The Puerto Rico Economic Activity Index is produced by the Economic Development Bank for Puerto Rico. The index measures economic activity in Puerto Rico using economic indicators and is highly correlated to Puerto Rico’s real GNP and annual growth rates, though is not a direct measurement of Puerto Rico’s GNP.

[16]While many of Puerto Rico’s agencies and component units individually receive single audits, the territory does not receive a single audit at the primary government level. To gain an understanding of Puerto Rico’s federal award audit opinions, audit findings, and questioned costs, we reviewed the latest single audit reporting packages that were available for Puerto Rico’s Departments of Education (fiscal year 2022), Health (fiscal year 2023), and Labor and Human Resources (fiscal year 2023).

[17]We refer to Puerto Rico’s pension-related liabilities as total net pension liabilities in this testimony. This amount is the sum of the primary government’s total pension liability and component units’ total pension liability, net pension obligation, and net pension liability.

[18]“Puerto Rico Territory Energy Profile,” US Energy Information Administration, last modified April 17, 2025, https://www.eia.gov/state/print.php?sid=RQ.

[19]Financial Oversight and Management Board for Puerto Rico, Annual Report 2024 (San Juan, PR: Jan. 22, 2025).

[20]We are conducting a separate review that examines issues with Puerto Rico’s electricity grid in more depth.

[21]Departamento de Recursos Naturales Y Ambientales. El Costo de la Inacción (September 2024).