BID PROTESTS

Key Features and Trends

Statement of Kenneth Patton, Managing Associate General Counsel

Before the Subcommittee on Government Operations, Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, U.S. House of Representatives

For Release on Delivery Expected at 10:00 a.m. ET

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Kenneth Patton at Pattonk@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-108652, a testimony Before the Subcommittee on Government Operations, Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, U.S. House of Representatives

Why GAO Did This Study

For nearly 100 years, GAO has provided an objective, independent, and impartial forum for the resolution of disputes concerning the awards of federal contracts. Consistent with Congress’ mandate in the Competition in Contracting Act of 1984, GAO provides for the inexpensive and expeditious resolution of more than 1,000 protests annually.

GAO’s testimony provides background information on bid protests and recent bid protest trends. This testimony is based on GAO’s prior legal work related to bid protests, including GAO’s Bid Protest Annual Reports to Congress.

This testimony describes key features of the bid protest process. It includes recent trends in bid protest filings, as well as addressing GAO’s recent response to Section 885 of the Servicemember Quality of Life Improvement and National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2025, Pub. L. No. 118-159 (Dec. 23, 2024).

The laws and regulations that govern contracting with the federal government are designed to ensure that federal procurements are conducted fairly. On occasion, vendors or offerors interested in government procurements may have reason to believe that a contract has been, or is about to be, awarded improperly or illegally, or that they have been improperly denied a contract or an opportunity to compete for a contract. A major avenue for relief for those concerned about the propriety of an award has been GAO’s bid protest forum.

The bid protest process established in the Competition in Contracting Act of 1984 seeks to provide a meaningful dispute resolution process while also ensuring the timely resolution of protests so that agencies can proceed with acquiring necessary goods or services. GAO resolves all protests to the maximum extent practicable within 100 calendar days of filing. Additionally, GAO is authorized to dismiss protests that on their face, do not state a valid basis for protest.

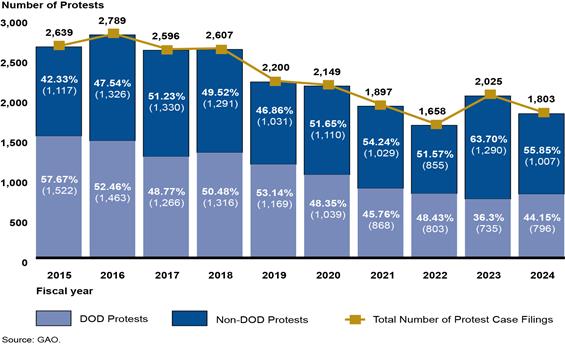

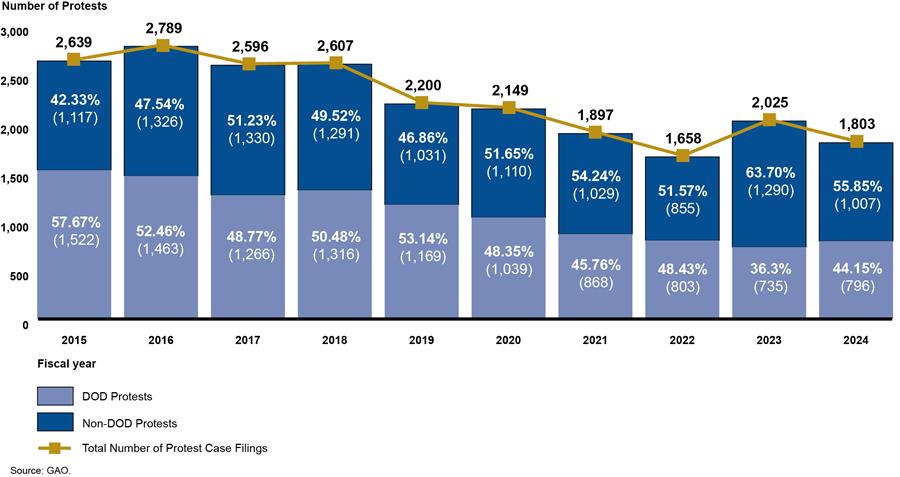

GAO routinely resolves over 1,000 bid protests annually within the 100 calendar day period. Protesters achieve some form of relief in approximately 50 percent of cases filed with our Office. GAO’s bid protest statistics reflect that over the past 10 years protest filings have overall declined by approximately 32 percent.

Figure 1: Percentage and Number of Protest Case Filings at GAO FY2015-FY2024

As part of the Servicemember Quality of Life Improvement and National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2025, Congress tasked GAO with proposing certain potential reforms to the bid protest process, including proposals to modify the pleading standard applied by GAO before a disappointed offeror may obtain access to agency procurement records, and for shifting the costs of other parties to the protester when a protester files an unsuccessful protest. As addressed in the response and in this testimony, GAO proposes to clarify GAO’s pleading standard. Also, while GAO remains neutral on creating a process to shift costs or fees, GAO discusses options that Congress could consider to implement such an approach.

B-423723

Chairman Sessions, Ranking Member Mfume, and Members of the Subcommittee:

Thank you for the opportunity to discuss the bid protest process and potential proposals for bid protest reform.

The Competition in Contracting Act of 1984 (CICA), specifically the provision codified at 31 U.S.C. § 3554(a)(1), establishes that the Government Accountability Office (GAO) is to provide for the inexpensive and expeditious resolution of protests of federal procurements. Consistent with our authorizing statute, GAO resolves more than a thousand protests every year within 100 calendar days. However, the number of bid protests filed at GAO has steadily declined (by 32 percent) over the last ten years, and protests of DOD procurements at GAO have fallen even more sharply over the same period (by 48 percent). Additionally, over the five-year period from fiscal years 2020 to 2024, at most 1.5 percent of DOD procurements were the subject of a protest at GAO. This is consistent with the findings of prior studies that protests challenging DOD contract awards remain rare, amounting to a low single digit percentage of DOD procurements.

Recently, Section 885 of the Servicemember Quality of Life Improvement and National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2025, Pub. L. No. 118-159 (Dec. 23, 2024) (FY2025 NDAA) included a provision for GAO to propose various possible reforms to the bid protest process as well as to create benchmarks of the costs of bid protests to various parties. In this regard, while the benefits of the protest system in promoting accountability, integrity, and legality in federal procurement are important, those benefits must also balance the public’s interest in allowing the government to efficiently and timely acquire the necessary goods and services to discharge its obligations. For example, protests may create costs and programmatic delays for agencies and potentially for firms awarded contracts that are subject to protest. However, during the preparation of our proposal we found that sufficient data was unavailable concerning DOD’s protest costs and contractor lost profit rates to calculate reliable benchmarks of these costs. For example, DOD does not track or record the costs of bid protests because it is not statutorily required to do so. Additionally, DOD expressed the view that, given the low number of protests of DOD procurements, the costs of tracking such data would outweigh the benefits.

Concerning proposed reforms to the bid protest process, section 885 included two relevant provisions. First, section 885 included a provision for GAO to consider enhanced pleading standards that protesters must meet before receiving access to administrative records for DOD procurements. Our regulations currently provide a robust pleading standard, and protests that do not meet our current pleading standard are dismissed, typically early in the process and prior to receiving access to agency records. While our current pleading standard allows us to dismiss legally insufficient protests early in the process, we proposed to enhance our existing pleading standard to make it clearer that protest allegations must be credible and supported by evidence.

Second, section 885 included a provision for GAO to propose a process for an unsuccessful protester to pay the government’s protest related costs and contract awardee’s lost profits. While GAO remains neutral on creating a fee shifting process for bid protests because existing statutory authorities and bid protest procedures are sufficient to efficiently resolve and limit the adverse impacts of protests filed without a substantial legal or factual basis, consistent with the requirements of section 885 we discussed two potential processes and practical and policy implications for Congressional consideration, that I will also discuss today.

My testimony today provides information on protests of DOD procurements, the protest process at GAO, and discussion of some proposals for bid protest reform. My remarks are primarily based on GAO’s annual bid protest reports to Congress, our recent proposal prepared in response to section 885 of the FY2025 NDAA, as well as a prior 2009 letter to Congress concerning frivolous protests at GAO.

Background

Pursuant to CICA, GAO provides an objective, independent, and impartial forum for the expeditious and inexpensive resolution of bid protests objecting to the award or proposed award of federal procurement contracts. The protest process plays a critical role in helping to ensure that federal agencies comply with Congress’ mandate to obtain full and open competition through the use of competitive procedures.[1] The public interest is served by ensuring the integrity of the federal government’s reasonable expenditure of federal funds, and that federal agencies are reasonably and fairly complying with the acquisition laws enacted by Congress and applicable acquisition regulations.[2] Finally, the protest process provides accountability, transparency, and confidence among current and potential government contractors that they will receive fair consideration in their business dealings with the government.[3] This belief in the fundamental fairness of the system increases competition by minimizing the barrier to entry that would otherwise be created by perceptions of a procurement system rife with corruption and a lack of integrity.

While the benefits of the protest system in promoting accountability, integrity, and legality in federal procurement are important, those benefits must also balance the public’s interest in allowing the government to efficiently and timely acquire the necessary goods and services to discharge its obligations. In this regard, both CICA and GAO’s bid protest regulations and procedures aim to fulfill the statutory directive that the GAO protest process provide, to the maximum extent practicable, for the efficient and inexpensive resolution of bid protests.[4] For example, CICA mandates that GAO issue a final decision concerning almost all protests within 100 days after the date the protest is submitted.[5] Additionally, to minimize the potential disruption of a protest on an agency’s procurement, our Office routinely resolves protests prior to CICA’s 100-day deadline. For example, in Fiscal Year 2024 only 23 percent of protests filed were addressed on the merits, the remainder were dismissed, typically much earlier in the process. To further illustrate this point, from fiscal years 2015 to 2024 there were 10,945 “non-developed” protests, and those protests were resolved on average within 23.39 days.[6] Moreover, for the 5,797 “developed” protests during fiscal years 2015 to 2024, those protests were resolved on average within 77.68 days, well in advance of the 100-day deadline.[7]

Congress also built into CICA another important flexibility for agencies to mitigate the potential impact of a protest on their ability to acquire needed goods and services in a timely manner--an agency’s ability to override the automatic stay of contract award or performance. Under CICA, if a protest is filed at GAO within prescribed deadlines, the procuring agency is generally precluded from making award or authorizing performance during the pendency of the protest.[8] The CICA stay is an important tool in ensuring the integrity of the competitive procurement process while GAO considers a pending protest.[9] CICA, however, expressly authorizes the head of a procuring activity to authorize award upon a written finding that urgent and compelling circumstances which significantly affects interests of the United States will not permit waiting for GAO’s decision.[10] Additionally, the head of a procuring activity may authorize performance upon a written finding that (a) performance of the contract is in the best interests of the United States; or (b) urgent and compelling circumstances that significantly affect interests of the United States will not permit waiting for GAO’s decision.[11] This important safety valve in the system provides agencies with the flexibility to timely obtain goods and services that are vital to support their mission notwithstanding any protest filed at GAO.

Bid Protest Trends

Consistent with our authorizing statute, GAO resolves more than a thousand protests every year within 100 calendar days. However, the number of bid protests filed at GAO has steadily declined (by 32 percent) over the last ten years, and protests of Department of Defense procurements at GAO have fallen even more sharply over the same period (by 48 percent).

Figure 1: Percentage and Number of Protest Case Filings at GAO FY2015-FY2024

Note: Consistent with our annual bid protest reports to Congress, total cases include protests, cost claims, and requests for reconsideration.

Before addressing the overall decline in bid protests filed with our Office, it is important to note that the data from our annual bid protest reports to Congress reflects relatively stable sustain and effectiveness rates over the past 10 years. GAO tracks both the “sustain” rate, which is the percentage of cases where we have issued a final decision on the merits finding that a procuring agency committed a “prejudicial violation” of applicable procurement law or regulation, as well as the “effectiveness” rate, which is based on the protester obtaining some relief from the agency, as reported to GAO, either as a result of voluntary agency corrective action or our Office sustaining a protest.[12] In this context, for Fiscal Year 2024, the sustain rate was 16 percent and the effectiveness rate was 52 percent. Those figures are generally consistent with the 10-year average sustain and effectiveness rates, which are 17 percent and 48.5 percent, respectively.[13] This data reflects a robust protest process that is targeting agency procurement errors where almost one in two protesters obtain some form of relief from the procuring agency.

Turning to the decline in protest filings, it is not clear why protests at GAO have declined (or why DOD protests have declined more sharply than protests generally), but we identify several possible changes that may have driven these shifts: enhanced debriefings at DOD; increases in our bid protest task order jurisdictional threshold; and the implementation of our Electronic Protest Docketing System (EPDS) and its attendant filing fee.[14]

Additionally, we assessed how frequently DOD procurements are protested, concluding that, over the five-year period from fiscal years 2020 to 2024, at most 1.5 percent of DOD procurements were the subject of a protest at GAO. This is consistent with the findings of prior studies that protests challenging DOD contract awards remain rare, amounting to a low single digit percentage of DOD procurements.

DOD and Frivolous Protests

Related to the topic of potential bid protest reform, Congress has previously asked GAO to assess DOD protests to determine the extent to which bid protests may be increasing, the extent to which frivolous and improper protests may be increasing, and the causes of any identified increases. In 2008, the House Armed Services Committee, directed GAO to provide recommendations regarding actions that Congress, or the executive branch, could take to disincentivize frivolous and improper bid protests on the part of industry.[15] Congress also has independently expressed concern about frivolous protest filings at GAO.[16] We think our previous work on DOD protests and what constitutes a frivolous protest can provide valuable perspectives on how Congress can address bid protest reform.

Preliminarily, as noted above, the bid protest effectiveness rate has remained steady over the years at approximately 50 percent. Put another way, half of protests filed are, at least to some extent, successful protests. However, the remaining 50 percent of protests that are ultimately unsuccessful are not necessarily frivolous.

As discussed in our 2009 report to Congress, in considering what it means for litigation to be frivolous, courts have identified two ways in which legal actions may be frivolous. First, a legal action is considered “frivolous as filed” when a plaintiff or appellant grounds its case on arguments or issues “that are beyond the reasonable contemplation of fair-minded people, and no basis for [the party’s position] in law or fact can be or is even arguably shown.”[17] Second, a legal action is considered “frivolous as argued” when a plaintiff or appellant has not dealt fairly with the court, has significantly misrepresented the law or facts, or has abused the judicial process by repeatedly litigating the same issue in the same court.[18]

The courts have repeatedly recognized, however, that a legal action found to be without merit or is ultimately incorrect is not necessarily frivolous.[19] That is, a frivolous legal action must be more than simply one without merit. Rather, a frivolous filing is one that the pursuing party knew or should have known--either at the time of filing or subsequently--that the legal action was so utterly without merit that it was essentially pursued in bad faith. We think this definition is appropriate and would be applicable to determining whether a protest filed before our Office was frivolous.

Applying that standard, the fact that a protest is denied for lack of merit does not necessarily mean that it was frivolous. Likewise, the fact that a protest is dismissed because of a procedural deficiency does not necessarily mean that the protest was frivolous. In our view, even when a protest is dismissed for lack of a valid legal basis, it should not necessarily be considered frivolous; rather, the key question is whether the protest was filed in bad faith. A determination by GAO that a protest is frivolous would require determining not only that the protest is without merit or procedurally defective, but also that the protest is so utterly without merit as to have been filed in bad faith.

GAO does not categorize protests as frivolous, and thus, has not identified any protests as frivolous. That does not mean, however, that meritless protests, or those that a reasonable third party might label frivolous, remain open at GAO, thus delaying procurements. GAO promptly dismisses protests that do not state a valid legal basis or are otherwise procedurally defective, consistent with our broad statutory authority. Thus, GAO dismisses protests, where appropriate, without the need to resolve whether the protest was frivolous.

Cost Benchmarks

Section 885 included a provision for GAO to prepare benchmarks of protest costs for DOD and GAO, as well as benchmarks for lost profit rates of contractors who were awarded a contract that was subsequently protested. In coordinating and obtaining data from DOD, department officials explained that DOD does not track any costs related to bid protests because it is not statutorily required to do so. DOD, therefore, indicated that it could not provide data concerning its protest-related costs. In compiling data on lost profits, we surveyed various trade groups and conducted a literature review. Our survey and literature review did not yield generalizable data concerning actual lost profit rates of contractors; however, we identified some published notional profit rate data, maximum profit rates for certain contract types, and various regulatory considerations regarding negotiations concerning profit rates. For example, in some circumstances, applicable procurement laws or regulations cap or limit a contractor’s ability to recover profit or fee from the government.

Enhanced Pleading Standards

Section 885 included a provision for GAO to consider enhanced pleading standards that protesters must meet before receiving access to administrative records for DOD procurements. Our regulations currently require that protests must set forth a detailed statement of the factual and legal grounds of protest and must clearly state legally sufficient grounds of protest. Our decisions explain that this standard requires at a minimum, either allegations or evidence sufficient, if uncontradicted, to establish the likelihood of the protester’s claim of improper agency action, although subsequent decisions have clarified that bare allegations are not sufficient to meet our pleading standard.

Protests that do not meet our pleading standard are dismissed, typically early in the process and prior to receiving access to agency records. While our current pleading standard allows us to dismiss legally insufficient protests early in the process, we proposed to clarify and enhance our pleading standard to require that protesters must provide, at a minimum, credible allegations supported by evidence that are sufficient, if uncontradicted, to establish the likelihood of the protester’s claim of improper agency action. This change, which we would apply to all protests not just those challenging procurements conducted by DOD, will both reduce ambiguity and further bolster GAO’s ability to expeditiously resolve protest allegations that are either not credible or unsupported by adequate evidence.

Fee Shifting

Finally, section 885 included a provision for GAO to propose a process for an unsuccessful protester to pay the government’s protest related costs and contract awardee’s lost profits. In considering the provision, we identified ways in which imposing such a fee-shifting process could have serious negative consequences for contractors, the government, and the procurement process as a whole. For example, the imposition of such a process may have a chilling effect on the participation of firms in the protest process and federal procurement as a whole. This would have a deleterious impact not only on the transparency and accountability of the procurement system, but also potentially reduce competition for the government’s requirements, which in turn could drive up the prices paid for goods and services. Moreover, an approach to fee-shifting based on benchmarks would be infeasible and would not result in an equitable distribution of costs.

To the extent that Congress wishes to impose fee shifting, any approach would require an individualized, case-by-case evaluation of both a party’s basis to recover its costs as well as the amount of such costs. Thus, any fee shifting process will necessarily add additional time, complexity, and cost to the protest resolution process because of the need for the parties to litigate and GAO to resolve such questions on a case-by-case basis. Additionally, fee-shifting could pose unique harms to small businesses which represent the majority of protesters in our forum. As a result, we remain neutral on creating a fee shifting process for bid protests because existing statutory authorities and bid protest procedures are sufficient to efficiently resolve and limit the adverse impacts of protests filed without a substantial legal or factual basis.

However, to the extent Congress seeks to implement a fee-shifting process for bid protests, we present two potential options along with discussion of potential legal and policy considerations.

First, Congress might consider a focused statutory requirement for DOD to include a contract provision that would permit DOD to recoup--or otherwise withhold--profit or fee from an incumbent contractor if the incumbent files a protest, the agency awards the incumbent an extension of its incumbent performance during the pendency of the protest, and its protest is subsequently dismissed as legally or factually insufficient or for otherwise being procedurally infirm. Second, Congress might consider authorizing GAO to require a protester whose protest is dismissed as legally or factually insufficient or for otherwise being procedurally infirm to reimburse DOD for the costs incurred in handling the protest, as well as any lost profits incurred by the awardee whose contract was stayed during the pendency of the protest. Such a process would require material statutory and administrative changes.

Additionally, as noted above, DOD does not track its protest costs and in order to reasonably and effectively support any cost-related claims, DOD (and private contractors) would need to implement sufficient accounting practices to reasonably support the costs claimed in connection with defending against unsuccessful protests. Moreover, to the extent Congress charges GAO with directing a private party to pay costs to DOD and other private parties, it is likely that GAO’s statutory authorities would need to be amended. In this regard, CICA only authorizes GAO to recommend that federal agencies take responsive actions where GAO determines that the solicitation, proposed award, or award does not comply with applicable procurement law or regulation.[20] To the extent Congress envisions a process where GAO directs a private party to reimburse the government or another private party, such a process would constitute a significant departure from GAO’s current statutory authorities and would require significant structural changes to CICA or GAO’s other statutory authorities.

Consistent with section 885’s requirement that we prepare our proposal in coordination with the Secretary of Defense, we provided a draft of the proposal to DOD for comment. In response, DOD noted that additional data collection concerning DOD’s protest costs would not provide sufficient benefit compared to the cost and administrative burden the data collection would require. DOD protests at GAO have declined 48 percent over the last 10 years and less than 2 percent of procurements are protested, and as a result DOD does not see a pressing need for this cost collection and the challenges associated with the requirement.

DOD emphasized that there were challenges and potential costs associated with cost data collection and that the risk associated with not collecting that data are minimal due to the decline in overall DOD protests with GAO and the very small percentage of total procurements that are protested. Finally, concerning a potential requirement for a contract clause that would permit the recoupment of profit or fee from incumbent contractors who file protests that are subsequently dismissed as legally or factually sufficient, DOD noted that, in its view, the costs outweigh the benefits of such a requirement, and that such a provision could also negatively impact competition if contractors decide not to bid due to the requirement.

Nonetheless, GAO currently has the tools necessary to perform our key role in the bid protest process, with due consideration of both agencies’ needs to proceed with their procurements and the need to provide an avenue of meaningful relief to protesters; we maintain the view expressed in our proposal that we do not seek further authority.

Thank you, Chairman Sessions, Ranking Member Mfume, and Members of the Subcommittee. This concludes my testimony. I would be pleased to answer any questions.

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1] 10 U.S.C. § 2304(a)(1)(A); 41 U.S.C. § 3301(a)(1).

[2] See, e.g., Intelligent Waves, LLC v. United States, 137 Fed. Cl. 623, 628 (2018) (“It is in the interest of the United States that the integrity of the competitive nature of the bid process as mandated by Congress is upheld.”); Dairy Maid Dairy v. United States, 837 F. Supp. 1370, 1382 (E.D. Va. 1993) (“Without doubt, the public interest is promoted by protecting the integrity of the procurement process. Moreover, there is a strong public interest in seeing that the government follows its substantive duties under the procurement statutes and regulations.”) (internal citations omitted).

[3] See, e.g., E-Management Consultants, Inc. v. United States, 84 Fed. Cl. 1, 10 (2008) (“The purpose of the procurement system as envisioned in CICA is a fair process in which disappointed offerors can seek review at GAO.”); B-401197, Report to Congress on Bid Protests Involving Defense Procurements, GAO (Apr. 9, 2009), at 3; Mark V. Arena, et al., Assessing Bid Protests of U.S. Department of Defense Procurements: Identifying Issues, Trends, and Drivers (RAND Corp. 2018) (hereinafter, the RAND Report), at 12-13; Daniel I. Gordon, Bid Protests: The Costs are Real, But The Benefits Outweigh Them, 42:3 Pub. Contract L.J. (2013), at 39-42.

[4] 31 U.S.C. § 3554(a)(1).

[5] Id. at (a)(1). CICA also contemplates that supplemental protest allegations, to the maximum extent practicable, also be resolved within the initial 100-day deadline. Id. at (a)(3). GAO routinely resolves supplemental protest allegations in the same decision with the initial protest allegations, within the initial 100-day deadline.

[6] GAO considers a protest “non-developed” where the protest is resolved without the agency’s submission of an agency report responding to the protester’s allegations and GAO dismisses the protest on the basis of an agency’s voluntary corrective action or for a procedural infirmity (e.g., where the protester has failed to allege legally or factually sufficient bases of protest, the protest is untimely, or GAO lacks jurisdiction over the protest).

[7] GAO considers a protest “developed” where the agency has submitted an agency report responding to the protester’s allegations and GAO has either issued a published decision resolving the protest or conducted alternative dispute resolution.

[8] 31 U.S.C. §§ 3553(c), (d).

[9] See, e.g., AT&T Corp. v. United States, 133 Fed. Cl. 550, 555 (2017) (“This automatic stay serves the important purpose of preserving competition in contracting and ensuring a fair and effective process at the GAO.”); B-401197, Report to Congress on Bid Protests Involving Defense Procurements, GAO (Apr. 9, 2009), at 3-4 (discussing legislative history of CICA and Congress’ intent to strengthen GAO’s bid protest forum by instituting the stay provisions).

[10] 31 U.S.C. § 3553(c)(2).

[11] Id. at (d)(3)(C).

[12] A violation of procurement law or regulation is only prejudicial in this context if a protester can demonstrate, that “but for” the agency’s violation, the protester would have had a substantial chance of receiving contract award. Violations that are not prejudicial do not result in the sustain of a protest and are denied.

[13] See, e.g., GAO Bid Protest Annual Report to Congress for Fiscal Year 2024, B‑158766, GAO‑25‑900611 (Nov. 14, 2024); GAO Bid Protest Annual Report to Congress for Fiscal Year 2019, B-158766, GAO‑20‑220SP (Nov. 5, 2019).

[14] While overall case filings have declined, we note that the filing fee does not appear to have had an adverse impact on small business filings. In this regard, as previously reported to Congress, the percentage of protests filed by small businesses remains robust and appears to have increased following implementation of EPDS and the attendant filing fee. See, e.g., B-336573, Letter from GAO to Congressional Committees re EPDS Filing Fee (Aug. 2, 2024), at 5 (noting that the annual percentages of protests filed by small businesses after implementation of EPDS has ranged from 62 to 73 percent).

[15] See B-401197, Report to Congress on Bid Protests Involving Defense Procurements, GAO (Apr. 9, 2009) at 1.

[16] See, e.g., Report of the Committee on Armed Services, House of Representatives, on H.R. 5658, H.R. Rep. No. 110-652, at 394 (May 16, 2008) (“The committee is concerned that the submission of a bid protest is becoming pro forma in the event that a prospective contractor is rejected from the competitive range or the award of a contract is made to another vendor, and that the number of frivolous bid protests submitted to the Government Accountability Office may be increasing.”).

[17] Abbs v. Principi, 237 F.3d 1342, 1345 (Fed. Cir. 2001), citing State Indus., Inc. v. Mor-Flo Indus., Inc., 948 F.2d 1573, 1578 (Fed. Cir. 1991).

[18] Abbs v. Principi, 237 F.3d at 1345; Lawrence N. Sparks v. Eastman-Kodak Co., 230 F.3d 1344, 1345 (Fed. Cir. 2000); Finch v. Hughes Aircraft Co., 926 F.2d 1574, 1582 (Fed. Cir. 1991).

[19] See Abbs v. Principi, 237 F.3d at 1345; The Ravens Group, Inc. v. United States, 79 Fed. Cl. 100, 114 (2007); Saladino v. United States, 63 Fed. Cl. 754, 757 (2005); see also Fed. R. Civ. P. 11 (Advisory Committee Notes on 1993 Amendments)

[20] 31 U.S.C. § 3554(b)(1).